Llewellyn King: America is desperate for skilled tradespeople

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a terrible shortage of people who fix things. I am thinking of electricians, plumbers, glaziers, auto mechanics, and many more skilled workers who keep life livable and society running.

It is frustrating if you can’t get a plumber when you need one. But the skilled- workers shortage has much larger consequences than the inconvenience of the homeowner. The very rate of national progress on many fronts is being affected.

More housing is desperately needed, but architects tell me that some new construction isn’t happening because of the skilled-workers shortage. Projects are being shelved.

The problem in electric utilities is critical — and interesting because they offer excellent pay, retirement and health care and still, they are falling short of recruits. They are very aware that many of their workers will be retiring in the next several years, adding to the problem. One utility, DTE, in Michigan, has been training former prisoners in vegetation control — the endless business of trimming trees around power lines.

Auto dealerships are scrounging for mechanics, now euphemistically called “technicians.”

Skilled workers are in short supply for the railroad and bridge industries. Many industries are prepared to offer training.

The need is great and it is having a quietly crippling effect on national prosperity.

President Joe Biden has been almost ceaselessly promoting solar and wind generation as job creators. Someone should tell him there is a severe shortage of those same electricians, pipe fitters, wind farm erectors and solar- panel installers.

The skilled-workers shortage has been worsening for some time, but it is now palpable.

There are contributory factors that have been building: The end of the draft meant an end to a lot of trade schooling in the military. Many a youth learned electronics, motor repair or simply how to paint something from Uncle Sam. That’s the generation that’s now retiring.

Then there is the education imbalance: We encourage too many below-average academic students to go to college. It is part of the credentialing craze.

Those less suited to academic life seek easier and easier courses in lesser and lesser colleges just to come out with a bachelor’s degree — a certificate that passes for a credential.

The result is a glut on the market of workers with useless degrees in such things as marketing, communications, sociology and even journalism. I can tell you that if you arrive in college in need of remedial English, your future as a journalist is likely to be wobbly.

Since childhood, I have been impressed with people who fix things: People like my father. He fixed everything from diesel engines to water well pumps, burst pipes and sagging roofs.

Men, and some women, of his generation worked with their hands but they were, in their way, Renaissance people. They knew how to fix things from a cattle feeder to a sewing machine, from a loose brick in a wall to a child’s bicycle to a boiler.

The work of fixing, of keeping things running, isn’t stupid work; it involves a lot of deduction, much knowledge and acquired skill.

Men and women who fixed things were at one with men and women who made things, often bound together in a common identity inside a union.

Think of the great names of the unions of the past, and the sense of pride members once took in their belonging: the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, the Teamsters or the United Autoworkers. You had work and social dignity. You weren’t looked down upon because you hadn’t been to college.

We aren’t going to quickly bring back honor to manual work or reverence for the great body of people who keep everything running. So we might look to the hundreds of thousands of skilled artisans who would do the work if they could enter the United States legally. Yes, the migrants milling at the southern border. Many skilled welders, plumbers and masons are yearning to cross the border and start fixing the dilapidated parts of this country.

The owner of a clothing factory told me that she was desperate to find women who could sew. She said that it is a skill that has just disappeared from the American workforce. A landscape contractor in Washington told me he would close without his Mexican workers.

A modest proposal: Let us write immigration law on the basis of who is really needed. Add to this a work permit dependent on fulfilling certain conditions. You would soon find company recruiters mingling with the border agents along the Rio Grande.

And we would lose our fear of a burst pipe. Help is just a frontier away.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: Brilliant, brazen Murdoch’s two-tiered approach

Rupert Murdoch accepting the conservative Hudson Institute's 2015 Global Leadership Award.

One of the Fox “News” -affiliated TV stations

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have watched Rupert Murdoch’s career with admiration, irritation and, sometimes, horror.

His besetting sin is that he goes too far. The fault that has landed Fox News settling with Dominion Voting Systems for $787.5 million isn’t new in the Murdoch experience.

He is a publishing and television genius. But like many a genius, his success keeps running away with him — and then he must pay up. He does so without apology and without discernible contrition. Those who know him well tell me he treats his losses with a philosophical shrug.

Murdoch’s talent reaches into many aspects of journalism. He has nerves of titanium in business and a fine ability to challenge the rules — and, if he can, to bend them.

As an employer he is ruthless and at times generous and indulgent. I know many who have worked for Murdoch and they speak about the contradictions of his ruthlessness and his generosity, particularly to those who have borne the battle of public humiliation for him. Check out the salaries at Fox News and the London Sun.

The Murdoch story begins, as most know, when he inherited a newspaper from his father. He quickly formed a mini-news empire in Australia.

But Murdoch had his sights set — as many in the former British possessions do — on London and the big time there. While at Oxford, he was hired as a sub-editor at The Daily Express, then owned by another colonial, the formidable Lord Beaverbrook.

In 1968, Murdoch bought The News of the World, a crime-centric Sunday paper. The next year, he bought the avowedly left-wing Sun.

Here Murdoch showed his genius at knowing the makeup of the audience and what it wanted: He flipped The Sun from left politics to extreme right and, for good measure, stripped the pinups of their bras.

That was a hit with men, and the politics were a revelation: Murdoch had defined a conservative, loyalist and anti-European vein in the British newspaper readership that hadn’t been mined. He went for it and soon had the largest circulation paper in Britain.

After he bought the redoubtable Times and Sunday Times, the Murdoch invasion was complete. He had also been instrumental in the launch of Sky News.

Money rolled in and political power and prestige with it — although there is no evidence that he sought formal preferment, like a peerage.

On to New York and U.S. newspapers.

Here the formula of sex and nationalism foundered. He didn’t succeed as an American newspaper proprietor except for deftly keeping The Wall Street Journal a prestige publication.

However, he brilliantly – with several bold moves — built a television network. Then, in the cable division, he applied the UK formula: Give the punters what they want.

In Britain it was sex and nationalism. In America, it was far-right jingoism. Murdoch gave it to Americans just as he had given it to the British: in large helpings of conspiracy, paranoia and nationalism.

In his tabloids, royal and celebrity gossip was the mainstay after right-wing Euro-bashing and breast-baring. He paid well for sensationalism and that attracted a seedy kind of private investigator-journalist, prepared to go further and deeper than his or her colleagues. Corruption of the police was the next step, along with telephone bugging and other egregious transgressions.

Eventually, it all came tumbling down. Murdoch had to appear before a parliamentary committee, fire people and, in a strange move, he closed The News of the World, as though the inanimate newspaper had been breaking the law without anyone knowing.

In fact, he had gone too far. The joyful music of the cash register had led to a wilder and wilder dance.

He damaged his legend, his papers and all of Britain’s journalism. He also lost the opportunity to buy control of Sky News.

But Fox was a joy. Oh, the sweet music and the wild dance! Give them what they want all day and all night. Give them their heroes untrammeled and their own facts. And finally, the election results they, the punters, wanted to believe, not the ones that the polls posted.

You can see the two-tiered approach that has worked so well for Murdoch working again here. Some respectable publications and some vulgar money makers, like his respected The Australian and his raucous big-city tabloids; in Britain, the respected Times and Sunday Times and the ultra-sensational Sun; in America, the respected Wall Street Journal and the disreputable Fox Cable News and his other remaining newspaper, the skallywag New York Post.

For a remarkably gifted man, Murdoch can do some appalling things and has genius without bounds.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Biden needs to recognize the perils of old age

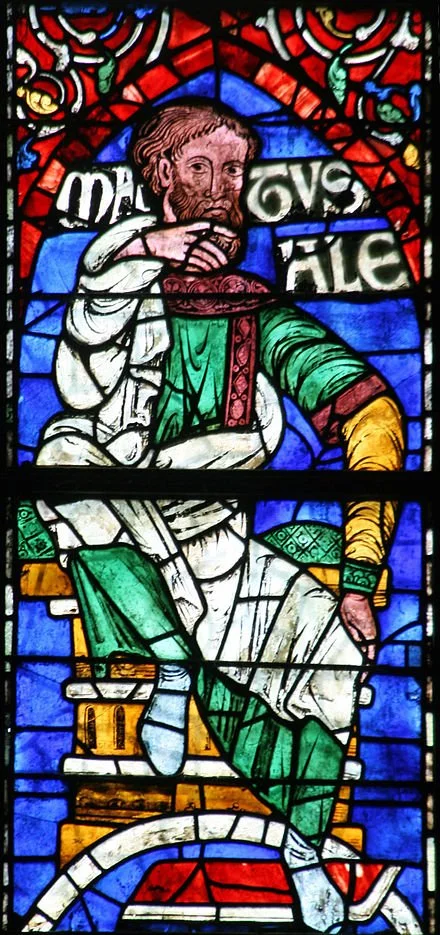

Stained glass window of Methuselah in the southwest transept of Canterbury Cathedral, in Kent, England. He was said in the Bible to have reached the age of 969, making him the oldest person in the Good Book.

Read about The New England Centenarian Study.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The case for Joe Biden to accept the inevitable dictates of his age and not run again is persuasive. Too much rests on the health and fitness of the president to turn it into a kind of roulette: When will his number come up?

Worse, what if Biden fails mentally and stays in office incognizant of his condition? Being the president of the United States is the most demanding and most responsible job in the world.

Winston Churchill got a second term as prime minister of Great Britain in 1951, and lots of stuff went wrong, from immigration policy to the growth of unchecked union power. History’s greatest prime minister had lost his acuity.

As I am older than Biden, I can say that he should quit. I love to work, but there’s the rub: Not all people and all work are created equally. What I do isn’t critical and doesn’t decide the nation’s future or war and peace.

No one would suggest that an artist toss the easel at a predetermined retirement age. Noel Coward, the great English entertainer, said, “Work is more fun than fun.” That depends on the work.

Age is a complex equation for society, and retirement is a nettlesome problem. France is in revolt over President Emmanuel Macron’s move to raise the retirement age to 64 from 62. Very reasonable, most Americans say.

The issue in France is simple: The French can’t afford huge state pensions any longer. There aren’t enough people at work to pay for those who have retired on their nearly full salaries. You can vote the population rich, but you can’t vote in new, young taxpayers to keep them rich. When the Social Security System falters in the next decade, America may be staring at the same sums as Macron.

Mandatory retirement is a crude way to manage the retirement dilemma. Some workers are genuinely unable to work into their 70s and 80s because their bodies, their minds or both are worn out. Others are at their most productive.

My father’s mind was fine, but he was a mechanic who had done everything from building steel structures to working in mines to repairing cars. His body failed around the age of 6o. He had been doing manual work since he was 13 but at 60 he couldn’t bend, twist, delve, lift, climb, stretch, grab or do many of the myriad things he had done all his life to earn a living. He had to work in a school and then a shop; he loved the school but not the shop. But he had to work. That is what he did: He got up every day and went to work.

He had worked so long and so hard, primarily self-employed, that he hadn’t had time to learn leisure — to play golf, to watch ballgames, to read for recreation, or even to learn how to socialize. That came with work or didn’t happen; friends were people at work.

A friend of mine, a nuclear engineer, reached mandatory retirement age and fell apart, much as my father nearly did. He, too, had no interests outside of his family and work and was lost in the post-job world.

Something of this same problem exists for people leaving the military. Their life is the military, and then, at an early age, there is no more of that life, their life.

When it comes to Biden, things are quite different.

I know the president slightly, and I like him. He loves the job. He has been at or near the peak of power for a long time. When his term ends, on Jan. 20, 2025, he should adjourn to his beach house in Delaware and write his memoirs.

Maybe someone will teach Biden how to play boules, a European form of bowls played by older people in parks. French boules aficionados would be happy to teach him the game. The French have a lot of time in retirement to perfect their play and travel to beach destinations. They would love to bring their skill to Rehoboth Beach, Del. Maybe I should join them.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

InsideSources

Llewellyn King: A shrug when it comes to mass murder with guns

AR-15-style assault rifle made by Southport, Conn.-based Sturm, Ruger & Co.

A Smith & Wesson AR-15-style assault rifle, designed to tear apart as many people as possible as fast as possible.

In Maryville, Tenn., where long -Springfield, Mass.-based gun maker Smith & Wesson’s is moving its headquarters. The company makes assault rifles beloved by mass murderers. That has bothered folks in Massachusetts but makes the company popular in gun-cult-dominated Tennessee and other violent Red States.

— Photo by Brian Stansberry

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Murder most foul,” cries the ghost of Hamlet’s father to explain his own killing in Shakespeare’s play.

We shudder in the United States when yet more children are slain by deranged shooters. Yet we are determined to keep a ready supply of AR-15-type assault rifles on hand to facilitate the crazy when the insanity seizes them.

The murder in Nashville of three nine-year-olds and three adults should have us at the barricades, yelling bloody murder. Enough! Never again!

But we have mustered a national shrug, concluding that nothing can be done.

Clearly, something can be done; something like reviving the assault rifle ban, which expired after 10 years of statistically proven success.

We are culpable. We think that our invented entitlement to own these weapons, designed for war, is a divine right, outdistancing reason, compassion, and any possible form of control.

The blame rests primarily on something in American exceptionalism that loves guns. I mostly understand that; I like them myself, as I write from time to time. I also like fast cars, small airplanes, strong drink, and other hair-raising things.

But society has said these need controls — from speed limits to flying instruction — and has severe penalties for mixing the first two with the last. Those controls make sense. We abide by them.

When it comes to that other great national indulgence, guns, society has said safety doesn’t count. So far this year, more than 10,000 people have been killed in gun violence. If that were the number of fatalities from disease, we would again be in lockdown.

We have concocted this scared right to keep and use guns. To ensure this, the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution has been manhandled by lawyers into being a justification for putting something deadly out of the reach of social control or even rudimentary discipline.

The latest school shooting has raised our hackles, but not our capacity to act. This national shrug at something which can be fixed is a stain on the body politic.

Most of the conservative wing of the establishment, represented by the Republican Party, has dismissed it as one might a natural disaster.

But the routine murder of innocents in school shootings is a man-made disaster. Worse, it is sanctified by a particular interpretation of the Second Amendment.

It is an interpretation which has demanded, and continues to demand, legal contortionism. This is used to justify the citizenry owning and using weapons of war.

This latest school shooting, which happened in this young year, was shocking, but what was more shocking was the political reaction.

President Biden wrung his hands and said nothing could be done without the support of Congress — thus endorsing a national fatalism.

Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina suggested more policemen in schools, and Rep. Thomas Massie (R.-Tenn.) said teachers needed to be armed. His children are homeschooled.

In personal life and in national life perceived impossibility is hugely debilitating.

Imagine if the Founding Fathers had said the British Empire was too strong to challenge, if FDR had said America couldn’t rise against the forces of the economic chaos of the 1930s, or if Margaret Thatcher had said British trade unions were too strong to be opposed?

These are incidents where perceived reality was, with struggle, trounced for the general good.

Guns along with drugs are the largest killer of young people. They aren’t unrelated. Unregulated guns find their way to the drug gangs of Central America, facilitating the flow of drugs.

On the Senate floor, the chamber’s longtime chaplain, retired Rear Adm. Barry C. Black, took on the pusillanimous members of his flock after the Nashville murders, quoting the 18th-century Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke’s admonition, “The only thing needed for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.” Indubitably.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: The Irish: ‘Little people,’ great writers and more; why they came to Boston

In Dublin

The Irish punch above their weight. That is why worldwide, on March 17, people who don’t have a platelet of Irish blood and who have never thought of visiting the island of Ireland joyously celebrate St. Patrick’s Day.

That day may or may not have been when St. Patrick, Ireland’s patron saint, died in the 5th Century.

The fact is, very little is known about St. Patrick. The broad outline is that he was born in Roman Britain, kidnapped by pirates as a child and taken to Ireland as a slave. He escaped, returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary and became a bishop.

To be sure, in the Emerald Isle truth can be augmented with folklore, mysticism, and the great love of a good story.

Hence devout Ireland can also believe in fairies and leprechauns, or little people, to this day. Both are quite real to some in Ireland, although, unlike the festival of St. Patrick, they don’t seem to have crossed the Atlantic, or even the Irish Sea, except in movies.

When horseback riding with my wife on an annual visit to the northwest of Ireland, we were curious about a stand of trees that seemed not to belong in the middle of a working farm field.

“A fairy ring is in there. You can ride through, if you keep on the path,” a stableman told us.

But he warned that if we got off the path, we would upset the fairies. “And you wouldn’t want to do that, would you?”

Indeed, we didn’t want to upset any fairies, so we stayed on the path, and all was well.

From what I have gathered, the little people co-exist with the fairies but also are separate.

A friend built a house for his mother near Galway. It was an A-frame house with a low, decorative wall around it. The wall had — surprise — a gap; not a gate, just a space of about 18 inches. That, she insisted, with the concurrence of locals, was for the little people to pass through. You don’t mess with the little people any more than you would trample a fairy circle.

The little people were originally an Irish tribe dating back to antiquity, who disappeared but were encased in legend. When Hollywood met Irish legends, the movies embraced the legends and expanded them.

Over the centuries, Ireland has been hard-used by England. It began with the English Reformation and Henry VIII and went on through the English Revolution, with Oliver Cromwell being especially brutal, then on to the potato famine in the 19th Century and the excesses of the Black and Tans, poorly trained and equipped, thuggish British troops with mismatched tunics and trousers.

Given that around 40 million Americans can claim some Irish ancestry, it might be argued that they were welcomed here. Hardly. Irish immigrants were often persecuted as they flooded in, escaping the privations at home.

I thank my friend Sheila Slocum Hollis, a very proud Irish-American, for pointing out that in the 1920s, the Irish were victims of the Ku Klux Klan violence in Denver. They fit the profile of KKK enemies, along with Blacks and Jews. Except they were Irish and Catholic.

In no field of endeavor have the Irish punched above their weight more than in literature. They took the language of the conqueror, the English, and have added to it immeasurably and profusely.

Irish writers have enhanced, expanded and luxuriated in the English language. Just a few towering names: Swift, Shaw, Wilde, Joyce, Yeats, Beckett, Goldsmith, Synge, Bowen, O’Brien, Hoult, Lavin, Murdoch, Binchy and, contemporarily, John Banville and Sally Rooney.

The Irish word for good fun is craic (pronounced “crack”). “Good craic” is a party where you indulge.

I wish you great craic this St. Patrick’s Day. May you consort with the little people, after some Guinness, and may the fairies guide you safely home. Sláinte!

Llewellyn

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Huge Irish flag hanging outside the Boston Harbor Hotel

— Photo by John Hoey

From The New England Historical Society:

“Boston has had an Irish population since the first four shiploads from Ulster arrived, in 1718. But not until the potato crop began to fail in 1845 did the huge influx of Irish immigrants sail into Boston Harbor.

The potato famine wasn’t the only thing that brought the Irish to Massachusetts rather than, say, Virginia or Maine. Hunger and poverty pushed the Irish out of Ireland, but the promise of work pulled them to Boston.

In the Atlas of Boston History, Robert J. Allison explains that Irish immigrants came for jobs. Jobs in the Merrimack River Valley, the most industrial region in the Western Hemisphere. Jobs in Lowell, the biggest industrial city in the United States. And jobs in Boston, a manufacturing powerhouse that led the nation in distilling and refining.’’

Irish immigrants arriving in Boston in 1857.

Llewellyn King: Folks want more power but not power lines

High-voltage overhead power lines.

— Photo by Magnolia677

WEST WARWICK,R.I.

If you punch in “outage map” in a search engine, you will get a series of maps, ranging from the whole country to state by state and even smaller jurisdictions. These maps show electrical outages across the United States and territories and are within 10 minutes of real time. The data come from the electrical utilities themselves.

The maps are enlightening. At this writing, there are some areas in the dark in Michigan and California. As severe weather sweeps across the country, more outages appear on the maps.

Today’s outages are all weather-caused. But in just a few years, they will reflect something else, something more ominous: shortages in the available amount of electricity. They will occur when demand begins to outstrip supply, as it frequently does in some developing countries.

The nation is in the grips of two great transitions: a transition from fossil-based generation (coal, natural gas and some oil) to renewables (primarily wind and solar) and a transition to electricity, especially in transportation with electric vehicles.

We are in a rush to electrify in order to reduce carbon emissions.

There are an astounding 3,000 utilities, ranging in size from very small public and rural electric cooperatives to very large, investor-owned firms such as Southern Company and Exelon.

These make up the electric supply system, which has been described as the world’s largest engine. They all work together with surprising unity and are variously connected to the three electric grids, the Eastern Grid, the Western Grid and ERCOT, the free-standing Texas grid.

Their challenge isn’t only where will the power come from, but also will there be enough transmission to move it to where it is needed? Duane Highley, CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association Inc., an electric cooperative based in Westminster, Colo., told me that the addition of two electric cars to a family home can raise electric consumption by as much as 40 percent.

Many utilities, including those in such rapid growth states as Texas, are counting on distributed generation, which is when the utility enters into agreements with its customers to share the burden. This can involve agreements with incentives to allow the utility remotely to turn off certain functions during peak hours, and to buy power from its customers if they have rooftop solar installations or if they have backup generators.

After Texas was felled by Winter Storm Uri, in February 2021, many electric customers are turning to generators and rooftop solar to protect themselves, David Naylor, president of Rayburn Country Electric Cooperative Inc., in Rockwall, Texas, told me. Faced with a growth rate that has been as high as 8 and 9 percent in recent years. Naylor is vigorously pursuing distributed generation.

In the electric-utility industry, distributed generation is spoken of as “the first step in the virtual power plant.” In Connecticut there are two pilot projects, promoted by SmartPower, a nonprofit green-energy concern, with a utility, Eversource, and Connecticut Green Bank. They’re helping customers to install solar power and a substantial battery. In return the utility acquires the right to draw down from that battery on certain days at times of high demand.

All of this will help, but it doesn’t overcome the fact that between now and 2050, a target year for carbon reduction, electricity demand will double in the nation, according to many experts, and there is no way that demand can be met on the present generation and transmission trajectory.

The biggest frustration in the industry isn’t siting new wind farms and solar plants, but building new transmission to move electricity from the resource-rich areas where, as Tri-State’s Highley says, “the wind blows and the sun shines,” such as the Western states, to where it is needed.

With money pouring out of the Department of Energy for projects, the problem isn’t money but selfishness — selfishness as in “not in my backyard.” No one wants power lines, just the power. And everyone wants more of it.

The fact is that if the nation continues to electrify at the present rate, shortages could begin at the end of the decade and worsen as the century rolls on.

Those outage maps might become must-watching — until the power for our computers fails, and your region gets color-coded on the outage map you can’t see.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: The lethal global infection of drones

Skydio’s X2 drone, made in the U.S. The company has a contract with the U.S. military.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Drones are the new weapons of war, causing military tactics and force structure to be reimagined. They bring a particularly deadly reality to guerrilla warfare, posing an existential threat in many theaters, especially the Middle East. Cities are almost defenseless.

Now Iranian drones are being deployed in North Africa and are posing a direct threat to Morocco.

Moroccan diplomats are actively raising the issue with Western governments. Iran, they say, in collusion with Algeria, is supplying the Polisario Front rebels, who are engaged in guerrilla attacks against Morocco over the kingdom’s position in the Western Sahara.

While the world was mesmerized by its nuclear program, Iran built itself into a powerful supplier of military drones to dictators and insurgents. Notably, of course, to Russia for use in Ukraine, but also to Iran’s proxies across the Middle East.

Iran’s experience with drones goes back to the war that Iran and Iraq fought between 1980 and 1988. In those days the drones were line-of-sight, simplistic and only good for surveillance.

Since then Iran has built generations of drones, large and small, but increasingly sophisticated. They were helped by captured U.S. drones that they reengineered, incorporating the latest technology.

Engines and parts have often been smuggled into Iran from the West. For example engines capable of powering drones were smuggled into Iran by declaring them for jet skis or snowmobiles. This was the case with the Austrian-built Rotax engine until the subterfuge was detected.

Now the Iranian military claims that its defense industrial complex can make the engines and all the parts of its drones domestically. One way or another, Iran now supplies an impressive array of drones with great loitering times and long delivery distances.

Ilan Berman, senior vice president of the American Foreign Policy Council, told me that Iran has come to the conclusion that its strength is not in force-on-force competition, but in aiding asymmetric conflicts “which is why they spent so much money and time on terrorism, and so much money and time on ballistic missiles. Then they hit upon drones as the evolution of precisely this strategy.”

Morocco is right to be worried about its new vulnerability. Drones, while they might not win a war, can inflict severe damage on a variety of targets, from tourist centers to military installations to vital power grids and power stations.

Drones are light, cheap and easily transported and hidden. Today’s generation of Iranian drones can carry substantial ballistic loads, as well as loitering for as long as 24 hours and sending back vital material on critical infrastructure.

There is a drone arms race in the Middle East region. After Iran, the largest manufacturer of drones in the region is Turkey — even small but wealthy countries such as the United Arab Emirates are building up drone- manufacturing capability. Turkish drones were critical in Azerbaijan’s recent conflict with Armenia, and they were used by both sides in the Libyan conflict.

What is lacking is adequate defenses against drone attacks, whether these are single mischief-making assaults or swarms designed for substantial damage. Berman said the only effective defensive system against drones is the Israeli “Iron Dome,” built with Israeli technology and assisted and financed by the United States.

Israel has so far been reluctant to sell Iron Dome, which catches low-flying projectiles fired from as close as 2.5 miles from the place of intercept. It is a complex, radar-based, portable defense arrangement, designed to destroy incoming rockets and drones from Gaza and its neighbors Syria and Lebanon, both of which host non-state Iranian proxies.

Berman believes that since Morocco is a signatory to the Abraham Accords, Israel might sell the Iron Dome system to Morocco, but that would take years of negotiation and sales are subject to a U.S. veto.

At present, Morocco’s strategy is to alert the world to the changing dynamics in the region and to the vulnerability of almost any country to drone attack — a new addition to guerrilla warfare and a deadly vulnerability of countries like Morocco, where state and non-players can cause mayhem without winning on the ground.

“What the Iranians bring to the table is that it is known that they are the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, now moving into Africa, enhancing the capability of their proxy groups,” Berman said.

Morocco is right to be worried, but so is the world. Drones are a lethal infection, spreading fast.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Remembering an engineering giant

Richard Morley

WEST WARWICK, R.I

People often ask me who are the most interesting or most influential people I have met. It is easy to say Margaret Thatcher or Bill Clinton, but sometimes the real history makers are never known outside of their specialty. One such was Richard Morley (1932-2017).

A mutual friend took me to meet Morley at his home, in Mason, N.H., about 23 years ago. We spent a delightful afternoon there. He let me move a pile of earth from one spot to another with a backhoe operated by a personal computer.

I didn’t realize that I was in the presence of a great inventor, a member of industrial royalty, who had moved technology a giant step forward and sped up the automation revolution.

Morley did that in 1968 when he and colleagues at General Motors perfected the programmable logic controller. With the PLC, automation had arrived for the car industry and much else.

If it is moved, stored, welded, shaped, collated and shoved out the door, a series of programmed controllers ordered all that. In fact, for everything manufactured, PLCs are at work translating the blueprints into products.

They are everywhere, from the factory floor to advanced farms, to city water plants, to oil and gas drilling. They occupy a part of the modern world known as operational technology, or OT.

Vital though OT is, it gets less attention than its big sibling, information technology, or IT.

Matt Morris, managing director of security and risk consulting at 1898 & Co., the consulting arm of Burns & McDonnell, the big architecture, engineering and construction firm, told me, “IT is the ‘carpeted space,’ and OT is the ‘uncarpeted space’ ”

In other words, much of industry’s heavy lifting is done by OT, while IT has taken over all of the other more obvious functions of society, from accounting to airline reservations, from doctors’ offices to designing aircraft.

IT is king, but that is only part of the story.

Regarding cybersecurity, OT and IT differ, but both have their vulnerabilities. When we say cybersecurity, we mostly mean IT. OT is different, and the threats emanating from attacks on it are usually more strategic and harder to identify.

Attacks on OT aren’t necessarily as immediately detectable as those on IT. They can be very subtle but also highly destructive and expensive.

The classic example of what can be done to OT was provided not in an attack on the United States but by the United States in 2007 (and revealed in 2010) when the nation’s cyber-warriors were able to slow down or speed up uranium-enrichment centrifuges in Iran. The Iranians didn’t know that their operating systems had been fooled surreptitiously. Their engineers were at a loss.

Now, 1898 & Co. is taking a bold step into the world of critical infrastructure resiliency with the creation of a new service aimed at offering full-time, proactive cybersecurity at critical infrastructure sites, like utilities, embracing IT and OT.

The company and its parent have enormous experience in utilities and other critical infrastructure, including oil rigs, refineries and water systems. Through a program they call “Managed Threat Protection and Response,” their aim is to take critical infrastructure defense and response to new levels. The capability is an addition to its existing Managed Security Services solution.

To implement this, the company has set up its program in Houston, far from its home base in Kansas City, Mo., to be near the customers — much critical infrastructure has links to Houston — but also, as Mark Mattei, 1898 & Co. director of cybersecurity, told me, to avail itself of the talent in the area.

The company is opening up a new horizon in cybersecurity, focusing on OT.

With IT, you would want to throw a switch, avert or stop the attack as fast as possible. But with OT, a more measured response might be called for. You wouldn’t want to shut down a whole plant because one pump had had its controller attacked or bring down part of the electricity grid because a single substation had evidence that it was malfunctioning because of an attack in one component.

The more one learns about cybersecurity, the more one appreciates the unsung heroes who take on unknown enemies 24 hours a day, every day of the year.

We are on the threshold of something big in defending critical infrastructure. I am sure that Richard Morley would have approved of this new approach.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

White House Chronicle

InsideSources

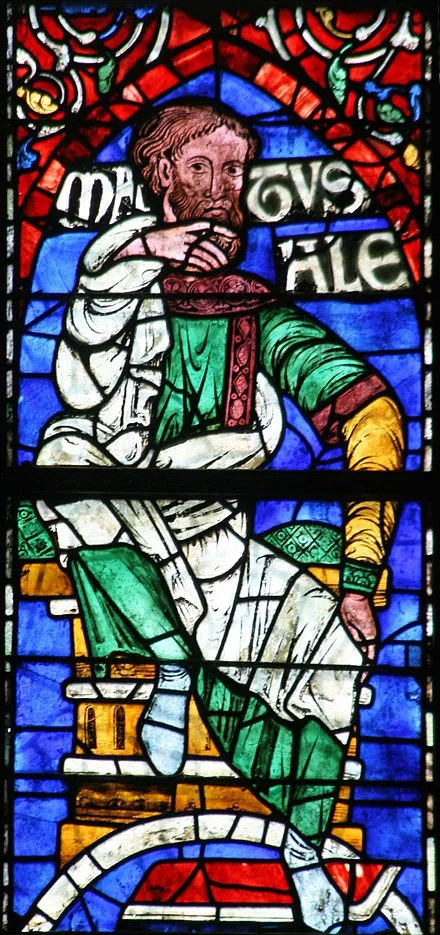

Sign for “Uncle Sam's House,’’ in Mason, N.H.

— Photo by Craig Michaud

Editor’s note:

Mr. Morley lived on his farm in Mason, N.H., for over 40 years, where he worked out of a renovated barn.

Llewellyn King: What made me an AI enthusiast.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have gone over. All the way. I have fallen in love with artificial intelligence. We need it, and I’m on board.

My conversion was sudden. It happened on one memorable day, Feb. 8, 2023. It was a sudden strike in a well-worn heart by Cupid’s arrow.

My love life with technology has been either unrequited or messy. I was always the one who blew the relationship, I admit that.

It started with computer typesetting. I was a committed hot-lead-type man. I didn’t want to see that painted lady, computer technology, destroying my divine relationship with hot type. But she did and when I tried to make amends, she was, er, cold, froze me out.

Likewise, as an old-time newspaperman, I was very proficient and happy with Telex. Computer technology separated us.

The worst of all was my first encounter with the internet.

I was pursuing the story of nuclear fusion at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California. A lab technician tried to interest me in the new device he was using to send messages: the Internet. I blew it off. “That is just Telex on steroids,” I said.

Ms. Internet doesn’t care to be scorned and she nearly cost me my manhood — well, my publishing company — when she took her terrible revenge. She killed print papers as well as hot type. She was a vengeful siren that way.

My conversion to AI began innocently enough. I was listening to a reporter on National Public Radio explaining how Microsoft’s new AI search engine would not only change the world of online searching but would also give Google a serious run for its money — billions of dollars, I might say parenthetically.

The writing's on the wall for Google unless it can get its AI to market fast. I was intrigued.

The illustration used by NPR reporter Bobby Allyn was that of buying a couch and carrying it home in your car. The new search engine, Allyn explained, will tell you if the couch you want to buy will fit in your car. It will know the dimensions of the car and, maybe, of the couch too. Wow!

Then I went on to watch a wild, unruly hearing before the U.S. House Oversight Committee. A long-suffering panel of former Twitter executives faced some pointed abuse from the Republican members. Some of those members never got to pose a question: Their time was entirely taken up castigating the witnesses over alleged collusion with the Biden administration and over Hunter Biden’s laptop — the holy grail for conspiracy theorists. It was a performance worthy of a Soviet show trial.

The worst aspects of the new House were on display. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D.-N.Y.) was visibly flustered because she wasn’t in her seat when her time to question the witnesses arrived. She rushed back to it and was so excitable that she was nearly incoherent.

Then there was Marjorie Taylor Greene (R.-Ga.), who was adamant that Twitter was advancing a political agenda by accepting the science that vaccines helped control the COVID-19 outbreak. She asserted that Twitter had a political objective when it denied her free-speech rights by suspending her account, after frequent warnings about her dangerous public health positions opposing vaccinations.

The lady's not for turning. Not by facts, anyway. That was clear. Any Southern charm she may possess was shelved in favor of invective. She told the former Twitter executives that she was glad they had been fired.

The clincher in my conversion to AI had nothing to do with the brutal thrashing of the experts, but with the explanation by Yoel Roth, former head of Trust and Safety at Twitter, who with forbearance explained that there were then and are now hundreds of Russian false accounts on Twitter aimed at influencing our elections and reaching deeply into our politics. Likewise, Iranian and Chinese accounts.

That is when it occurred to me: AI is the answer. Not the answer to the mannerless ways of the House hearing, but to the whole vulnerability of social media.

We have to fight cyber excess with cyber: Only AI can deal with the volumes of malicious domestic and foreign material on the net. Too bad it won’t resolve the free-speech issues, or the one that emerged at the House hearing: the right to lie without restraint.

This AI doubter is now an enthusiast. Bring it on.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington. D.C.

Llewellyn King: My brief for America’s embattled police

Los Angeles Police Department officers arresting suspects during a traffic stop. Such stops can be life-threatening for the police.

— Photo by Jim Winstead

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Police excess has gained huge attention after the death of George Floyd, in Minneapolis in 2020, and the alleged beating death of Tyre Nichols, in Memphis, last month. But police excess isn’t new.

A friend of mine, who had been drinking and could be quite truculent when drunk, was severely beaten in the police cells in Leesburg, VA., a couple of decades ago. I have never seen a man so badly hurt in a beating -- and I have done my share of police reporting.

That he provoked the police, I have no doubt. But no one should be beaten by the police anywhere, ever, for any amount of provocation. I might mention that my friend -- and the officers who might have killed him -- were white.

I used to cover the Thames Police Court, in the East End of London. That was before immigration had changed the makeup of the East End. It was then, as it had been for a long time, solidly white working class.

Every so often, a defendant would appear in the dock showing signs that he had been in a fight. One man had an arm in a sling, another had a black eye, a third had bruises on his face. One thing was common: If they looked beaten-up, they would be charged with “resisting arrest,” along with such other charges as drunkenness and petty larceny.

In the press benches, we shrugged and would just say something like, “They worked that bloke over.” We never thought to raise the issue of police brutality. It was just the way things were.

At least nowadays, when social norms don’t allow for police hitting suspects, there is a slight chance of redress. Although I would wager that nearly all police violence goes unreported, and the “blue wall” closes tightly around it.

People in uniform, men and women, hold dominion over a prisoner. If there is ethnic bias or verbal provocation, bad things can and do happen.

Yet I hold a brief for the police. Policing is dangerous and heartbreaking work, especially in the United States where guns are everywhere, Also it is shift work, itself a stressing factor.

Wearing the blue isn’t easy, and abuse and danger go with the job. Sean Bell, a former British policeman, now a professor at the Open University, described the police workload in the United Kingdom this way, “Those in the policing environment can become a human vacuum for the grief, sorrow, distress and misfortune for the victims of crime, road crashes and the plethora of other incidents dealt with time after time.”

Many of the incidents of American police being shot and police exceeding their authority have as their genesis at a traffic stop, as with Tyre Nichols. These are a cause of fear for both the police and criminals. It is where the rubber meets the road of law enforcement.

We motorists form our opinions of the police largely through traffic stops, which we rail against. But to the police, they are a life-threatening hazard as they approach a car that may have a crazed or dangerous criminal driver with a gun. They face danger and tragedy in plain sight.

The only thing that police officers are more wary of than traffic stops are domestic-violence calls. They are the worst, officers in Washington have told me.

Yet the traffic stop is an essential police tool, partly for controlling traffic but importantly for arresting criminals, fugitives and drug transporters. It is how the police work within the constitutional prohibition on illegal search and seizure.

People who have control of other people — drill sergeants, wardens and the police — are in a position to abuse, and some do. A uniform and authority can bring out the inner beast. Remember what went on in Abu Ghraib prison, in Iraq?

Following the two terrible incidents of police excess, Floyd and Nichols, all the solutions seem inadequate. But when out on the streets or in our homes, most of us are vitally aware that we feel secure because a call to 911 will bring the law — the men and women in blue who guarantee our safety and well being.

What to do about police violence? Vigilance is the first line of defense, but appreciating the police as well as holding them to account helps. Not many police officers feel appreciated, and that isn’t good for them or for society.

“The policeman’s lot is not a happy one!” So wrote British dramatist W.S. Gilbert in The Pirates of Penzance, an 1879 comic opera, one of his collaborations with composer Arthur Sullivan.

And Gilbert and Sullivan had never dreamt of a traffic stop.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Boston has the oldest municipal police department in America.

Llewellyn King: Big tech media monopolize ads, ravage journalism and act as global censors

At a Google advertising seminar in London in 2010

— Photo by Derzsi Elekes Andor

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The Department of Justice has filed suit against Google for its predatory advertising practices. Bully!

Not that I think Google is inherently evil, venal or greedier than any other corporation. Indeed, it is a source of much good through its awesome search engine.

But when it comes to advertising, Google, and the others with high-tech media platforms, most notably Facebook, have done inestimable damage. They have hoovered up most of the available advertising dollars, bankrupting much of the world’s traditional media and, thereby, limiting the coverage of the news — especially local news.

They have ripped the heart out of the economics of journalism.

Like other Internet companies, they treasure their own intellectual property while sucking up the journalistic property of the impoverished providers without a thought of paying.

While I doubt thatr the DOJ suit will do much to redress the advertising imbalance (Axios argues that the part of Google the DOJ wants divested only accounts for 12 percent of the company’s revenue), it will keep the issue of what to do about big tech media churning.

The issue of advertising is an old conundrum, written extra-large by the Internet.

Advertisers have always favored a kind of first-past-the-post strategy. In practice this has meant in the world of newspapers that a small edge in circulation means a massive gulf in advertising volume.

Broadcasting, through the ratings system, has been able to charge for the audience it gets, plus a premium for perceived audience quality — 60 Minutes compared to, say, Maury, which was canceled last year.

But mostly, it is always about raw numbers of readers, listeners and viewers. In a rough calculation, first past the post has meant 20 percent more of the audience turns into 50 percent more of the available advertising dollars.

I would cite The New York Times's leverage over the old New York Herald Tribune, The Baltimore Sun’s edge over the old News-American, and The Washington Post’s advantage over the old Evening Star. The weaker papers all in time folded even when they had healthy circulations, just not healthy enough.

Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.,with their massive reach are killing off the traditional print media and wreaking havoc in broadcasting. This calls out for redress but it won’t come from the narrow focus of the DOJ suit.

The even larger issue with Google and its compatriots is freedom of speech.

The Internet tech publishers, for that is what they are, Google, LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook and others, reserve the right to throw you off their sites if you indulge in speech that, by contemporary standards, incites hate, violence or at least social disturbance.

Conservatives believe that they are victimized, and I agree. Anyone whose speech is restricted by another individual or an institution is a victim of prejudice, albeit the prejudice of good intent.

Recently, I was warned by LinkedIn that I would be barred from posting on the site because I had transgressed — and two transgressions merit banning. The offending item was an historical piece about a World War II massacre in Greece. The offense may have been a dramatic photograph of skulls, taken by my wife, Linda Gasparello, displayed in the museum at Distomo, scene of a barbarous genocide.

I followed the appeal procedure against the two-strikes-you’re-out rule, but I have heard nothing. I expect the censoring algorithms have my number and are ready to protect the public from me next time I write about an ugly historical event.

The concept of “hate speech” is contrary to free expression. It calls for censorship even though it professes otherwise. Any time one group of people is telling another, or even an individual, what they can say, free speech is threatened, the First Amendment compromised

The problem isn’t what is called hate speech but lying — a malady that is endemic in the political class.

The defense against the liars who haunt social media is what some find hateful speech: ridicule, invective, irony, satire, and all the other weapons in the literary quiver.

The right to bear the arms of free and open discourse shouldn’t be infringed by the social media giants.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

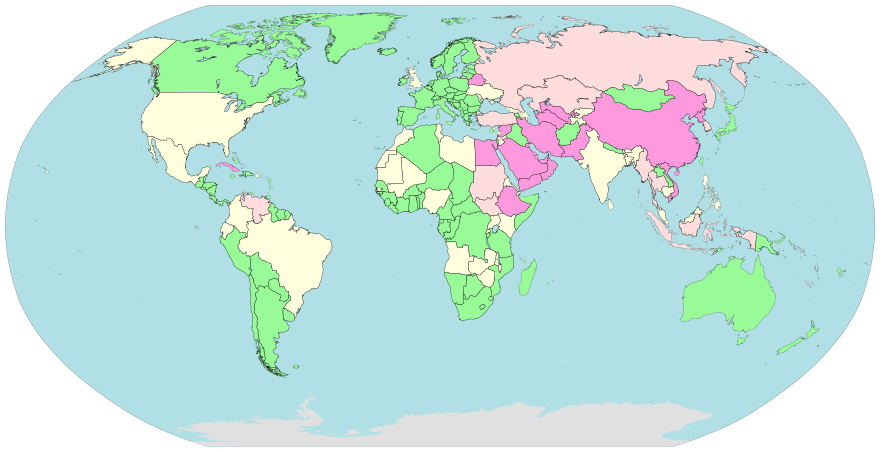

Llewellyn King: Rich nations must lead the way on the bumpy road to a green future

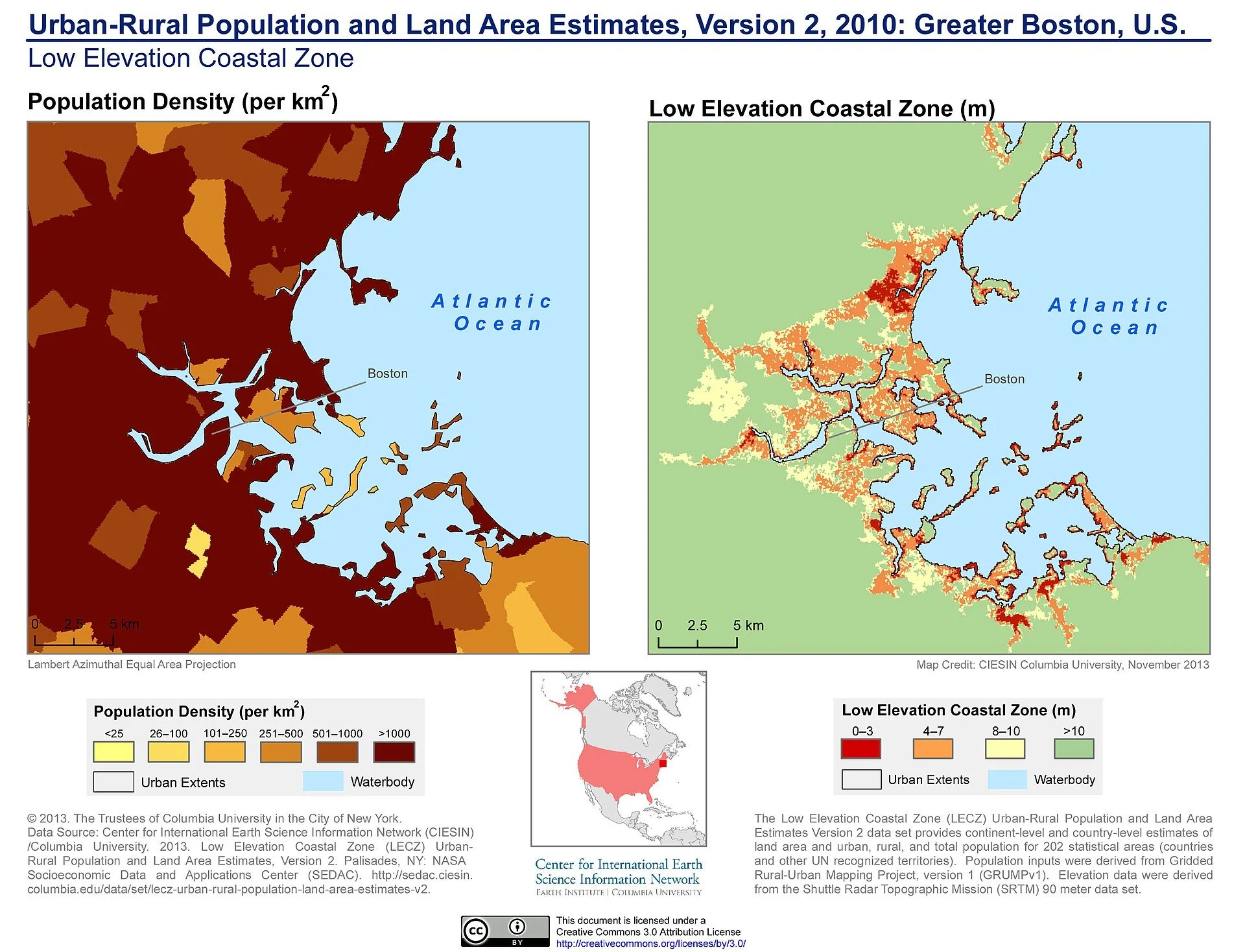

Rising seas caused by global warming threaten Greater Boston.

SEDACMaps - Urban-Rural Population and Land Area Estimates, v2, 2010: Greater Boston, U.S.

ABU DHABI, United Arab Emirates

I first heard about global warming being attributable to human activity about 50 years ago. Back then, it was just a curiosity, a matter of academic discussion. It didn’t engage the environmental movement, which marshaled opposition to nuclear and firmly advocated coal as an alternative.

Twenty years on, there was concern about global warming. I heard competing arguments about the threat at many locations, from Columbia University to the Aspen Institute. There was conflicting data from NASA and other federal entities. No action was proposed.

The issue might have crystallized earlier if it hadn’t been that between 1973 and 1989, the great concern was energy supply. The threat to humanity wasn’t the abundance of fossil fuels. It was the fear that there weren’t enough of them.

The solar and wind industries grew not as an alternative but rather as a substitution. Today, they are the alternative.

Now, the world faces a more fearsome future: global warming and all of its consequences. These are on view: sea-level rise, droughts, floods, extreme cold, excessive heat, severe out-of-season storms, fires, water shortages, and crop failures.

Sea-level rise affects the very existence of many small island nations, as the prime minister of Tonga, Siaosi Slavonia, made clear here at the annual assembly of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), an intergovernmental group with 167 member nations.

It also affects such densely populated countries as Bangladesh, where large, low-lying areas may be flooded, driving off people and destroying agricultural land. Salt works on food, not on food crops.

Sea-level rise threatens the U.S. coasts — the problem is most acute for such cities as Boston, New York, Miami, Charleston, Galveston and San Mateo. Flooding first, then submergence.

How does human catastrophe begin? Sometimes it is sudden and explosive, like an earthquake. Sometimes it advertises its arrival ahead of time. So it is with the Earth’s warming.

Delegates at the IRENA assembly felt that the bell of climate catastrophe tolls for their countries and their families. There was none of the disputations that normally attend climate discussions. Unity was a feature of this one.

The challenge was framed articulately and succinctly by John Kerry, U.S. special presidential envoy for climate. Kerry’s points:

—Global warming is real, and the evidence is everywhere.

—The world can’t reach its Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030 or the ultimate one of net-zero carbon by 2050 unless drastic action is taken.

—Warming won’t be reversed by economically weak countries but rather by rich ones, which are most responsible for it. Kerry said 120 less-developed countries produce only 1 percent of the greenhouse gases while the 20 richest produce 80 percent.

—Kerry, notably, declared that the technologies for climate remediation must come from the private sector. He wants business and private investment mobilized.

The emphasis at this assembly has been on wind, solar and green hydrogen. Wave power and geothermal have been mentioned mostly in passing. Nuclear got no hearing. This may be because it isn’t renewable technically. But it does offer the possibility for vast amounts of carbon-free electricity. It is classed as a “green” source by many government institutions and is now embraced by many environmentalists.

The fact that this conference has been held here is of more than passing interest. Prima facie, Abu Dhabi is striving to go green. It has made a huge solar commitment to the Al Dhafra project. When finished, it will be the world’s largest single solar facility. Abu Dhabi is also installing a few wind turbines.

Abu Dhabi has a four-unit nuclear power-plant at Barakah, with two 1,400-megawatt units online, one in testing and one under construction. Yet, the emirate is a major oil producer and is planning to expand its production from more than 3 million barrels daily to 5 million barrels.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has made oil more valuable, and even states preparing for a day when oil demand will drop are responding. Abu Dhabi isn’t alone in this seeming contradiction between purpose and practice. Green-conscious Britain is opening a new coal mine.

The energy transition has its challenges — even in the face of commitment and palpable need. The delegates who attended this all-round excellent conference will find that when they get home.

In the United States, utilities are grappling with the challenge of not destabilizing the grid while pressing ahead with renewables. Lights on, carbon out, is tricky.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. And he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

InsideSources

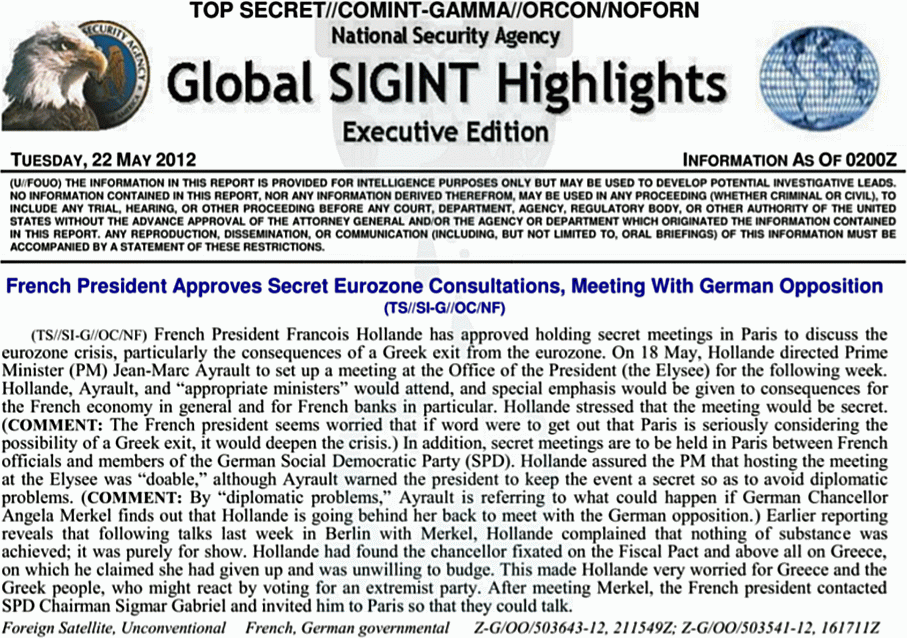

Llewellyn King: My adventures with classified documents

In 1983, Sen. Barry Goldwater (R.-Ariz.) reprimanding CIA Director William J. Casey for Secret information showing up in The New York Times, but then saying it was over-classified to begin with.

It is easy to start hyperventilating over classified documents. It isn’t the classification but what is in the documents that counts. Much marked classified is rubbish.

I have been around the classification follies for years. In 1970, I did what might be called a study, but it was just a freelance article on the use of hovercraft by the military. I was paid $250 to write it.

In those days, there was no easy way to copy a document. The standard was to put several sheets of paper in a typewriter with carbon sheets between them.

Like any other journalist, I started by going to the best library I had access to — in this case, The Washington Post library. I read what was available, largely newspaper clipping, and wrote the article.

Arctic, a consulting company, paid me to write it, and I forgot about it. A couple of years later, I wanted the article — probably to use to get other work — and I asked Arctic for it. They said it had been delivered to the Pentagon long since, and I had better ask the commissioning Department of Defense office.

I did that and was told that I couldn’t have the article, nor could I even look at it because it had been “classified” and I didn’t have clearance.

It had gone, like so much else, into the dark underworld of the classified from whence few pieces of paper ever return.

When James Schlesinger became chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, in 1971, one of the first things he did was to revamp the classification of documents. He told me that the AEC was classifying far more than was necessary and, as a result, the system wasn’t safer but more vulnerable.

His argument was that for classification to work, the people managing classified material had to have confidence that it was truly deserving of secrecy. He directed the declassification of the trivial and increased the security surrounding what was vital.

Schlesinger was succeeded as chairman by Dixy Lee Ray. At the time, I covered the nuclear industry and Ray became a social friend as well as a subject.

Once Ray and I went to dinner at the historic Red Fox Inn in Middleburg, Va. After a swell meal, we walked to her limousine in the parking lot behind the inn. She had something in her briefcase that she wished me to have.

But Ray always had her two dogs with her. One was a huge gray wolfhound and the other was a smaller gray dog, which looked like the wolfhound but was half the size.

The dogs were in the front seat of the car and a high wind was blowing. Ray opened one back door and I opened the other. Then she opened her briefcase and was rifling through the contents — some of which were marked as classified with a telltale, red X — when the big wolfhound jumped onto the back seat. He knocked over the briefcase and the wind blew documents all over the parking lot.

It was a security crisis. Not that Soviet agents were dining at The Red Fox Inn that night, but if any document marked as secret was found and handed to the police, a major scandal would have resulted.

For the best part of an hour, Ray, myself and her driver scoured the parking lot, the grassy areas and the bushes for documents.

In the early morning, I drove back to the inn to make sure we had made a clean sweep. State secrets in the parking lot of a pub make for hot headlines and end careers.

In the age of computers, classified documents — and who knows if they should be marked as such — are much less likely to be put into paper folders.

Once the Congressional Joint Committee, which oversaw the Atomic Energy Commission, held a hearing in its secure hearing room in the U.S. Capitol, where all the documents before the members and the witnesses were marked “eyes only.” The hearing had to be canceled because no one could say anything.

Also, once at one of the major nuclear-weapons laboratories, I deduced what a machine I was told was used for conducting “scientific experiments” really was. The director assured the technician showing it, “Don’t worry, King is too stupid to know what it is.” He was right and another state secret was saved.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Federal container for storing classified documents.

Llewellyn King: Get ready for blackouts and brownouts in the great energy transition

Electricity-transmission line in western Connecticut — a common scene in New England’s wooded areas.

Pole transformer. There’s a shortage of these things.

A perfect storm is gathering over the electric utility industry in the United States. It may break this year, next year or the year after, but break it will.

That is the consensus from utility executives I have been talking to over the past month. Several issues together amount to a clear danger of widespread blackouts and brownouts in the coming years. They come under the rubric of “transition.”

There are, in fact, two transitions stretching the electric utility industry. One is the climate imperative to turn from fossil fuels, primarily coal and natural gas with a smidgeon of oil, to renewables, almost totally wind and solar.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration reckons that electricity from solar and wind will rise this year to 26 percent from 24 percent of national electricity, and that natural gas, the workhorse of the generation mix, will fall to 36 percent from 38 percent.The balance is dwindling coal use at 19 percent, and nuclear, hydro and geothermal generation making up the rest.

That leaves a significant need for new renewable generation: That is the first transition. It isn’t going as fast as the environmental lobby, or the Biden administration, would like, nor even as fast as the utilities would like. It has been substantially crimped by the supply chain tangle.

The American Public Power Association and the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association have been vocal about the shortage of pole transformers. The supply has dried up. Without transformers, new hookups are impossible and old ones are threatened if the transformers fail. The waiting list for something as simple as a bucket truck is three years.

Recent legislation has poured money at an unprecedented rate into the development of renewables, but none of it will help in the short term. It is a case of trying to force more of something into a bladder that is expanding too slowly and that can’t expand faster because of multiple restraints. A utility executive told me that the money is, if anything, making matters worse.

One of the things most concerning to the utilities is the fate of natural gas, both for its availability and price. Gas remains the principal go-to fuel for utilities. Many regard gas as a storage system even if they aren’t burning it to generate power daily.

Gas is special because it is relatively clean, it can be stored, and it can be installed in a short time at many locations. It doesn’t require trains, as does coal, and it works in any weather if the plants have been properly weatherized. Also, gas is very efficient to burn, so more of it can be transformed into electricity through so-called combined-cycle plants. It beats coal and nuclear hands down on the simplicity of the infrastructure it needs. Its efficiency is rated at about 64 percent versus 32 percent, or thereabouts, for coal.

Many utility executives believe that gas should be the primary way we store energy. They advocate maintaining a robust gas infrastructure so that it can come online quickly when needed and can run for as long as needed, unlike batteries.

But national gas policy is confusing. We want gas to be sent to Europe but not piped to New England, which may have an electricity deficit this winter, if not the next.

The second transition, working in tandem with the first, is electrification.

The United States is already headed toward a totally electrified transportation system, but heavy industry, like steel and cement, is also switching to electricity. Demand is showing the first signs of explosive growth. By 2050, demand will have more than doubled, according to many surveys.

While that alone is destabilizing, there is a wild card: the new unpredictable weather behavior.

This winter so far, we have had floods in California, freezing in Texas, tornadoes in the Midwest, and record snowfall in Buffalo. Add this to the other variables in electricity delivery, and you have a very troubling picture with such things as attacks on substations, cyberattacks and that pesky supply chain.

My advice: Keep spare batteries handy and a good supply of canned food. If you are sitting in the dark, you don’t want to be hungry.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: U.S. airlines gouge and pack

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A Conservative British Prime Minister, Edward Heath, coined the phrase “the unacceptable face of capitalism” in 1973. He was describing the actions of Roland Walter “Tiny” Rowland and the company he headed, Lonrho (London Rhodesia), a mining and real-estate conglomerate with interests across Africa.

Having had a hectic travel schedule since the end of the COVID-19 lockdown, I can say that the airlines have become an unacceptable face of capitalism.

I refer to the airlines collectively because from the traveling public’s point of view, they are a massive whole with little to choose between them. Nominally in competition, their attitude to the public has become a common one of disrespect.

That one of the airlines, Southwest, would implode when stressed was no surprise. A metamorphosis had taken place in the last two years with the passengers -- the customers – becoming, in the collective airline psyche, just economic opportunities, ripe for endless upselling.

When the airlines realized that they could extract money over and above the ticket price, they began a service free fall and abandoned any pretense of respect for their customers -- or, apparently, themselves. They, the customers, had become economic targets for exploitation.

First came the baggage charges. Surely, the airlines knew people didn’t travel without bags and could have allowed for that in ticket pricing.

Then they found they could upsell the seating, making passengers pay extra for marginally better seats, and even for boarding about five minutes early.

On a recent flight in a Boeing 767, the airline was charging a stiff premium to sit in the double seats near the window rather than in the three abreast in the middle. My wife and I stayed in the middle.

A new class of service called “basic economy” has prohibited carry-ons in the overhead bins, forcing passengers to pay for checked baggage and wiping out some of their flight-cost savings.

I have flown round the globe for decades and have known every class of service, from that on the Concorde to the wonders of first class on Asian air carriers. But mostly, I have sat in the back and watched as the aircraft have gotten older and shabbier, as the seating area has shrunken, as the lavatories have shrunken in number and size, as the snacks and food offering are as incomprehensible as they are inedible, and as the flexibility of tickets has disappeared.

In tandem with these deteriorations in comfort, service and pricing, has come cancellation of normal business practices when it comes to cash and credit cards. You can no longer buy a ticket with cash at the airport. You can’t use a credit card on board for a snack if you haven’t pre-registered your credit card and, in many cases, you must have your own device to watch entertainment.

For a fee, of course, you can now get Wi-Fi on many airlines. But the seats are so positioned that you can’t, in my experience, open a laptop and work. For another fee, they may have a fix.

As I have strapped myself into a sometimes-broken seat (which reclines about 2 inches), looking at the ashtray (which indicates the age of the cabin furnishings), I have begun to wonder to what extent this predatory approach to passengers, this total indifference to those who pay the stiff fares and all the fees on top, has filtered down to the maintenance department.

Passengers, I guess, are inured to the horrors of airline travel and the victimhood that goes with it. Know this: If you are trying to travel by air, you have identified yourself as an economic target for a group of companies, the airlines, which supposedly compete but which, within hours, match every new fee dreamed up by one of their supposed competitors.

The latest serious inequity is defrauding passengers by reducing the value of their frequent-flyer miles.

U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg needs to take a root-and-branch look at the airlines: the greed, the collusion and the manifest disrespect for the passengers that is pervasive. Importantly, he needs to look at seat size and aisle width and their impact on safety.

I have a full flying schedule ahead in January, and I am preparing for my time in the gouging skies with trepidation and resignation.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

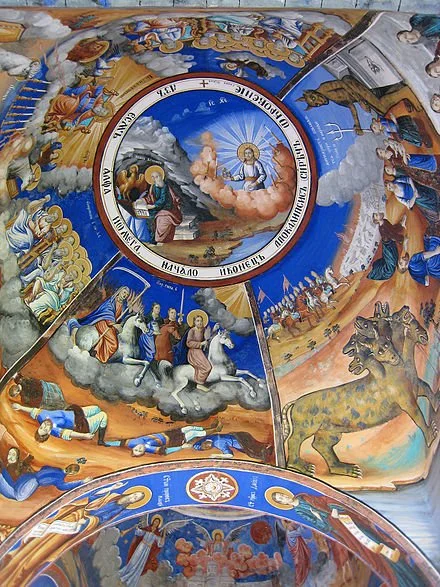

Llewellyn King: 2022’s biggest crises will be 2023’s, too

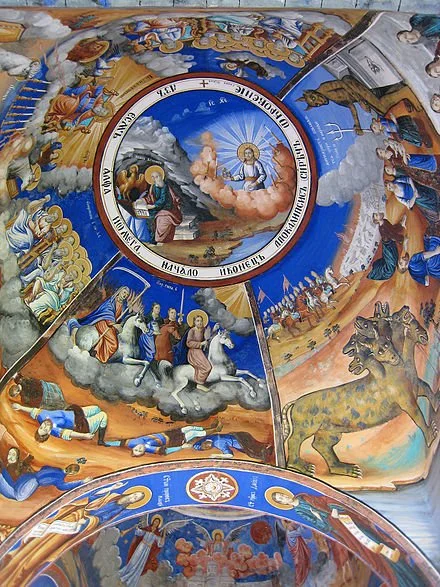

The Apocalypse, depicted in Orthodox Christian traditional fresco scenes in Osogovo Monastery, North Macedonia.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There are no new years, just new dates.

As the old year flees, I always have the feeling that it is doing so too fast; that I haven’t finished with it, even though the same troubles are in store on the first day of the new year.

Many things are hanging over the world this transition. None is subject to quick fixes.

Here are the three leading, intractable mega-issues:

First, the war in Ukraine. There is no resolution in sight as Ukrainians survive as best they can in the rubble of their country, subject to endless pounding by Russian President Vladimir Putin. It is as ugly and flagrant an aggression as Europe has seen since days of Hitler and Stalin.

Eventually, there will be a political solution or a Russian victory. Ukraine can’t go on for very long, despite its awesome gallantry, without the full engagement of NATO as a combatant. It isn’t possible that it can wear down Russia with the latter’s huge human advantage and Putin’s dodgy friends in Iran and China.

One scenario is that after winter has taken its toll on Ukraine, and the invading forces, a ceasefire-in-place is declared, costing Ukraine territory already held by Russia. This will be hard for Kyiv to accept -- huge losses and nothing won.

Kyiv’s position is that the only acceptable borders are those that were in place before the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. That almost certainly would be too high a price for Russia.

Henry Kissinger, writing in the British magazine “The Spectator,” has proposed a ceasefire along the borders that existed before the invasion of last February. Not ideal but perhaps acceptable in Moscow, especially if Putin falls. Otherwise, the war drags on, as does the suffering, and allies begin to distance themselves from Ukraine.

A second huge, continuing crisis is immigration. In the United States, we tend to think that this is unique to us. It isn’t. It is global.

Every country of relative peace and stability is facing surging, uncontrolled immigration. Britain pulled out of the European Union partly because of immigration. Nothing has helped.

This year 504,000 immigrants are reported to have made it to Britain. People crossing the English Channel in small boats, with periodic drownings, has worsened the problem.

All of Europe is awash with people on the move. This year tens of thousands have crossed the Mediterranean from North Africa and landed in Malta, Spain, Greece and Italy. It is changing the politics of Europe: Witness the new right-wing government in Italy.

Other migrant masses are fleeing eastern Europe for western Europe. Ukraine has a migrant population in the millions seeking peace and survival in Poland and other nearby countries.

The Middle East is inundated with refugees from Syria and Yemen. These millions follow a pattern of desperate people wanting shelter and services, but eventually destabilizing their host lands.

Much of Africa is on the move. South Africa has millions of migrants, many from Zimbabwe, where drought has worsened chaotic government, and economic activity has come to a halt because of electricity shortages.

Venezuelans are flooding into neighboring Latin American countries, and many are journeying on to the southern border of the United States.

The enormous movement of people worldwide in this decade will have long-lasting effects on politics and cultures. Conquest by immigration is a fear in many places.

My final mega-issue is energy. Just when we thought the energy crisis that shaped the 1970s and 1980s was firmly behind us, it is back -- and is as meddlesome as ever.

Much of what will happen in Ukraine depends on energy. Will NATO hold together or be seduced by Russian gas? Will Ukrainians survive the frigid winter without gas and often without electricity? Will the United States become a dependable global supplier of oil and gas, or will domestic climate concerns curb oil and gas exports? Will small modular reactors begin to meet their promise? Ditto new storage technologies for electricity and green hydrogen?

Energy will still be a driver of inflation, a driver of geopolitical realignments, and a driver of instability in 2023.

Add to worsening weather and the need to curb carbon emissions, and energy is as volatile, political, and controversial as it has ever been. And that may have started when English King Edward I banned the burning of coal in 1304 to curb air pollution in the cities.

Happy New Year, anyway.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: New hope arises for fusion energy after years of broken hearts, but….

The target chamber of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s National Ignition Facility in California where 192 laser beams delivered more than 2 million joules of ultraviolet energy to a tiny fuel pellet to create fusion ignition on Dec. 5, 2022.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

While the rafters are ringing with praise for the nuclear-fusion breakthrough at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), let me inject a sour note: This isn’t the beginning of cheap, safe, non-polluting electricity.

It is a scientific milestone, not an electricity one. Science tantalizes but it also deceives. Often the mission turns out not to be the one for which years of scientific research was aiming.

I would remind the world that science stirred great hope futilely with the idea of superconductivity at ambient temperatures, after some laboratory success.

The history of fusion itself is a clear illustration of expectations dashed, revived, resurrected, and dashed again. Now there is some hope with a stunning lab success: the first future experiment with “gain,” meaning more energy came out of the experiment than went into it.

Fusion has been the goal, the light at the end of the tunnel for nuclear researchers for over 60 years. In that time there have been false prophets, failed attempts, elaborate claims, and just hard slog.

That hard slog has shown what is possible: More power has been achieved in a fusion experiment for a fraction of a second. That is a huge success but it isn’t limitless electricity, as some have heralded.

Fission — which makes possible our power reactors and warships — is the splitting of the atom to release heat that is converted, via steam, into electricity.

Fusion, beguiling fusion, seeks to do what happens in stars and the sun — the fusing of two atoms together to produce heat, which, in a reactor, would be used to create steam and turn turbines, making electricity.

Governments and researchers have salivated over the possibility of fusion for decades and it has been well-funded worldwide, compared with other energy sources.