‘A charmed antiquity’

“View of Boston,’’ by J. J. Hawes, c. 1860s–1880s

My northern pines are good enough for me,

But there’s a town my memory uprears—

A town that always like a friend appears,

And always in the sunrise by the sea.

And over it, somehow, there seems to be

A downward flash of something new and fierce,

That ever strives to clear, but never clears

The dimness of a charmed antiquity.

— “Boston,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935)

‘Hazy images reveal stories’

“Labor” (colored pencil on paper), by Azita Moradkhani, at Samson Projects, Boston, through May 21.

The gallery says:

“Azita Moradkhani was born in Tehran where she was exposed to Persian art, as well as Iranian politics, and that double exposure increased her sensitivity to the dynamics of vulnerability and violence that she now explores in her art-making

“Moradkhani’s work in drawing and sculpture has focused on the female body and its vulnerability to different social norms. It examines the experience of finding oneself insecure in one’s own body. As Wangechi Mutu says, ‘females carry the marks, language, and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.’ In her drawings, the incorporation of unexpected images within intimate apparel intends to bring humor, surprise and a shock of recognition. Layers of hazy images reveal stories, with the hope of leaving a mark on the audience. Two worlds–birthplace and adopted home–live alongside each other in her work, joining intimately at a single point.’’

Llewellyn King: The Irish: ‘Little people,’ great writers and more; why they came to Boston

In Dublin

The Irish punch above their weight. That is why worldwide, on March 17, people who don’t have a platelet of Irish blood and who have never thought of visiting the island of Ireland joyously celebrate St. Patrick’s Day.

That day may or may not have been when St. Patrick, Ireland’s patron saint, died in the 5th Century.

The fact is, very little is known about St. Patrick. The broad outline is that he was born in Roman Britain, kidnapped by pirates as a child and taken to Ireland as a slave. He escaped, returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary and became a bishop.

To be sure, in the Emerald Isle truth can be augmented with folklore, mysticism, and the great love of a good story.

Hence devout Ireland can also believe in fairies and leprechauns, or little people, to this day. Both are quite real to some in Ireland, although, unlike the festival of St. Patrick, they don’t seem to have crossed the Atlantic, or even the Irish Sea, except in movies.

When horseback riding with my wife on an annual visit to the northwest of Ireland, we were curious about a stand of trees that seemed not to belong in the middle of a working farm field.

“A fairy ring is in there. You can ride through, if you keep on the path,” a stableman told us.

But he warned that if we got off the path, we would upset the fairies. “And you wouldn’t want to do that, would you?”

Indeed, we didn’t want to upset any fairies, so we stayed on the path, and all was well.

From what I have gathered, the little people co-exist with the fairies but also are separate.

A friend built a house for his mother near Galway. It was an A-frame house with a low, decorative wall around it. The wall had — surprise — a gap; not a gate, just a space of about 18 inches. That, she insisted, with the concurrence of locals, was for the little people to pass through. You don’t mess with the little people any more than you would trample a fairy circle.

The little people were originally an Irish tribe dating back to antiquity, who disappeared but were encased in legend. When Hollywood met Irish legends, the movies embraced the legends and expanded them.

Over the centuries, Ireland has been hard-used by England. It began with the English Reformation and Henry VIII and went on through the English Revolution, with Oliver Cromwell being especially brutal, then on to the potato famine in the 19th Century and the excesses of the Black and Tans, poorly trained and equipped, thuggish British troops with mismatched tunics and trousers.

Given that around 40 million Americans can claim some Irish ancestry, it might be argued that they were welcomed here. Hardly. Irish immigrants were often persecuted as they flooded in, escaping the privations at home.

I thank my friend Sheila Slocum Hollis, a very proud Irish-American, for pointing out that in the 1920s, the Irish were victims of the Ku Klux Klan violence in Denver. They fit the profile of KKK enemies, along with Blacks and Jews. Except they were Irish and Catholic.

In no field of endeavor have the Irish punched above their weight more than in literature. They took the language of the conqueror, the English, and have added to it immeasurably and profusely.

Irish writers have enhanced, expanded and luxuriated in the English language. Just a few towering names: Swift, Shaw, Wilde, Joyce, Yeats, Beckett, Goldsmith, Synge, Bowen, O’Brien, Hoult, Lavin, Murdoch, Binchy and, contemporarily, John Banville and Sally Rooney.

The Irish word for good fun is craic (pronounced “crack”). “Good craic” is a party where you indulge.

I wish you great craic this St. Patrick’s Day. May you consort with the little people, after some Guinness, and may the fairies guide you safely home. Sláinte!

Llewellyn

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Huge Irish flag hanging outside the Boston Harbor Hotel

— Photo by John Hoey

From The New England Historical Society:

“Boston has had an Irish population since the first four shiploads from Ulster arrived, in 1718. But not until the potato crop began to fail in 1845 did the huge influx of Irish immigrants sail into Boston Harbor.

The potato famine wasn’t the only thing that brought the Irish to Massachusetts rather than, say, Virginia or Maine. Hunger and poverty pushed the Irish out of Ireland, but the promise of work pulled them to Boston.

In the Atlas of Boston History, Robert J. Allison explains that Irish immigrants came for jobs. Jobs in the Merrimack River Valley, the most industrial region in the Western Hemisphere. Jobs in Lowell, the biggest industrial city in the United States. And jobs in Boston, a manufacturing powerhouse that led the nation in distilling and refining.’’

Irish immigrants arriving in Boston in 1857.

H.G. Wells: In Boston, 'an immense effect of finality'

Entrance to the Club of Odd Volumes, a social and literary club for bibliophiles. It’s on Mount Vernon Street, on Beacon Hill.

H.G. Wells visited it in 1906.

Commonwealth Avenue, in Boston’s Back Bay, in 1901

“The Boston Enchantment

“Yet even as I write of the universities as the central intellectual organ of a modern state, as I sit implying salvation by schools, there comes into my mind a mass of qualification. The devil in the American world drama may be mercantilism, ensnaring, tempting, battling against my hero, the creative mind of man, but mercantilism is not the only antagonist. In Fifth Avenue or Paterson one may find nothing but the zenith and nadir of the dollar hunt, at a Harvard table one may encounter nothing but living minds, but in Boston—I mean not only Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue, but that Boston of the mind and heart that pervades American refinement and goes about the world—one finds the human mind not base, nor brutal, nor stupid, nor ignorant, but mysteriously enchanting and ineffectual, so that having eyes it yet does not see, having powers it achieves nothing....

“I remember Boston as a quiet effect, as something a little withdrawn, as a place standing aside from the throbbing interchange of East and West. When I hear the word Boston now it is that quality returns. I do not think of the spreading parkways of Mr. Woodbury and Mr. Olmstead nor of the crowded harbor; the congested tenement-house regions, full of those aliens whose tongues struck so strangely on the ears of Mr. Henry James, come not to mind. But I think of rows of well-built, brown and ruddy homes, each with a certain sound architectural distinction, each with its two squares of neatly trimmed grass between itself and the broad, quiet street, and each with its family of cultured people within. I am reminded of deferential but unostentatious servants, and of being ushered into large, dignified entrance-halls. I think of spacious stairways, curtained archways, and rooms of agreeable, receptive persons. I recall the finished informality of the high tea. All the people of my impression have been taught to speak English with a quite admirable intonation; some of the men and most of the women are proficient in two or three languages; they have travelled in Italy, they have all the recognized classics of European literature in their minds, and apt quotations at command. And I think of the constant presence of treasured associations with the titanic and now mellowing literary reputations of Victorian times, with Emerson (who called Poe ‘that jingle man’), and with Longfellow, whose house is now sacred, its view towards the Charles River and the stadium—it is a real, correct stadium—secured by the purchase of the sward before it forever....

“At the mention of Boston I think, too, of autotypes and then of plaster casts. I do not think I shall ever see an autotype again without thinking of Boston. I think of autotypes of the supreme masterpieces of sculpture and painting, and particularly of the fluttering garments of the ‘Nike of Samothrace.’ (That I saw, also, in little casts and big, and photographed from every conceivable point of view.) It is incredible how many people in Boston have selected her for their aesthetic symbol and expression. Always that lady was in evidence about me, unobtrusively persistent, until at last her frozen stride pursued me into my dreams. That frozen stride became the visible spirit of Boston in my imagination, a sort of blind, headless, and unprogressive fine resolution that took no heed of any contemporary thing. Next to that I recall, as inseparably Bostonian, the dreaming grace of Botticelli's ‘Prima vera.’ All Bostonians admire Botticelli, and have a feeling for the roof of the Sistine chapel—to so casual and adventurous a person as myself, indeed, Boston presents a terrible, a terrifying unanimity of aesthetic discriminations. I was nearly brought back to my childhood's persuasion that, after all, there is a right and wrong in these things. And Boston clearly thought the less of Mr. Bernard Shaw when I told her he had induced me to buy a pianola, not that Boston ever did set much store by so contemporary a person as Mr. Bernard Shaw. The books she reads are toned and seasoned books—preferably in the old or else in limited editions, and by authors who may be lectured upon without decorum....

“Boston has in her symphony concerts the best music in America, and here her tastes are severely orthodox and classic. I heard Beethoven's Fifth Symphony extraordinarily well done, the familiar pinnacled Fifth Symphony, and now, whenever I grind that out upon the convenient mechanism beside my desk at home, mentally I shall be transferred to Boston again, shall hear its magnificent aggressive thumpings transfigured into exquisite orchestration, and sit again among that audience of pleased and pleasant ladies in chaste, high-necked, expensive dresses, and refined, attentive, appreciative, bald, or iron-gray men....

“II

“Boston's Antiquity

“Then Boston has historical associations that impressed me like iron-moulded, leather-bound, eighteenth-century books. The War of Independence, that to us in England seems half-way back to the days of Elizabeth, is a thing of yesterday in Boston. ‘Here,’ your host will say and pause, ‘came marching’ so-and-so, ‘with his troops to relieve’ so-and-so. And you will find he is the great-grandson of so-and-so, and still keeps that ancient colonial's sword. And these things happened before they dug the Hythe military canal, before Sandgate, except for a decrepit castle, existed; before the days when Bonaparte gathered his army at Boulogne—in the days of muskets and pigtails—and erected that column my telescope at home can reach for me on a clear day. All that is ancient history in England and in Boston the decade before those distant alarums and excursions is yesterday. A year or so ago they restored the British arms to the old State-House. ‘Feeling,’ my informant witnessed, ‘was dying down.’ But there were protests, nevertheless....

“If there is one note of incongruity in Boston, it is in the gilt dome of the Massachusetts State-House at night. They illuminate it with electric light. That shocked me as an anachronism. It shocked me—much as it would have shocked me to see one of the colonial portraits, or even one of the endless autotypes of the Belvidere Apollo replaced, let us say, by one of Mr. Alvin Coburn's wonderfully beautiful photographs of modern New York. That electric glitter breaks the spell; it is the admission of the present, of the twentieth century. It is just as if the Quirinal and Vatican took to an exchange of badinage with search-lights, or the King mounted an illuminated E.R. on the Round Tower at Windsor.

“Save for that one discord there broods over the real Boston an immense effect of finality. One feels in Boston, as one feels in no other part of the States, that the intellectual movement has ceased. Boston is now producing no literature except a little criticism. Contemporary Boston art is imitative art, its writers are correct and imitative writers the central figure of its literary world is that charming old lady of eighty-eight, Mrs. Julia Ward Howe. One meets her and Colonel Higginson in the midst of an authors' society that is not so much composed of minor stars as a chorus of indistinguishable culture. There are an admirable library and a museum in Boston, and the library is Italianate, and decorated within like an ancient missal. In the less ornamental spaces of this place there are books and readers. There is particularly a charming large room for children, full of pigmy chairs and tables, in which quite little tots sit reading. I regret now I did not ascertain precisely what they were reading, but I have no doubt it was classical matter.

“I do not know why the full sensing of what is ripe and good in the past should carry with it this quality of discriminating against the present and the future. The fact remains that it does so almost oppressively. I found myself by some accident of hospitality one evening in the company of a number of Boston gentlemen who constituted a book-collecting club. They had dined, and they were listening to a paper on Bibles printed in America. It was a scholarly, valuable, and exhaustive piece of research. The surviving copies of each edition were traced, and when some rare specimen was mentioned as the property of any member of the club there was decorously warm applause. I had been seeing Boston, drinking in the Boston atmosphere all day.... I know it will seem an ungracious and ungrateful thing to confess (yet the necessities of my picture of America compel me), but as I sat at the large and beautifully ordered table, with these fine, rich men about me, and listened to the steady progress of the reader's ever unrhetorical sentences, and the little bursts of approval, it came to me with a horrible quality of conviction that the mind of the world was dead, and that this was a distribution of souvenirs.

“Indeed, so strongly did this grip me that presently, upon some slight occasion, I excused myself and went out into the night. I wandered about Boston for some hours, trying to shake off this unfortunate idea. I felt that all the books had been written, all the pictures painted, all the thoughts said—or at least that nobody would ever believe this wasn't so. I felt it was dreadful nonsense to go on writing books. Nothing remained but to collect them in the richest, finest manner one could. Somewhere about midnight I came to a publisher's window, and stood in the dim moonlight peering enviously at piled copies of Izaak Walton and Omar Khayyam, and all the happy immortals who got in before the gates were shut. And then in the corner I discovered a thin, small book. For a time I could scarcely believe my eyes. I lit a match to be the surer. And it was A Modern Symposium, by Lowes Dickinson, beyond all disputing. It was strangely comforting to see it there—a leaf of olive from the world of thought I had imagined drowned forever.

“That was just one night's mood. I do not wish to accuse Boston of any wilful, deliberate repudiation of the present and the future. But I think that Boston—when I say Boston let the reader always understand I mean that intellectual and spiritual Boston that goes about the world, that traffics in book-shops in Rome and Piccadilly, that I have dined with and wrangled with in my friend W.'s house in Blackheath, dear W., who, I believe, has never seen America—I think, I say, that Boston commits the scholastic error and tries to remember too much, to treasure too much, and has refined and studied and collected herself into a state of hopeless intellectual and aesthetic repletion in consequence. In these matters there are limits. The finality of Boston is a quantitive consequence. The capacity of Boston, it would seem, was just sufficient but no more than sufficient, to comprehend the whole achievement of the human intellect up, let us say, to the year 1875 A.D. Then an equilibrium was established. At or about that year Boston filled up.

Late 19th Century print

“III

“About Wellesley

“It is the peculiarity of Boston's intellectual quality that she cannot unload again. She treasures Longfellow in quantity. She treasures his works, she treasures associations, she treasures his Cambridge home. Now, really, to be perfectly frank about him, Longfellow is not good enough for that amount of intellectual house room. He cumbers Boston. And when I went out to Wellesley {College} to see that delightful girls' college everybody told me I should be reminded of the ‘Princess.’ For the life of me I could not remember what ‘Princess.’ Much of my time in Boston was darkened by the constant strain of concealing the frightful gaps in my intellectual baggage, this absence of things I might reasonably be supposed, as a cultivated person, to have, but which, as a matter of fact, I'd either left behind, never possessed, or deliberately thrown away. I felt instinctively that Boston could never possibly understand the light travelling of a philosophical carpet-bagger. But I hid—in full view of the tree-set Wellesley lake, ay, with the skiffs of ‘sweet girl graduates’—own up. ‘I say,’ I said, ‘I wish you wouldn't all be so allusive. What Princess?’”

“It was, of course, that thing of Tennyson's. It is a long, frequently happy and elegant, and always meritorious narrative poem, in which a chaste Victorian amorousness struggles with the early formulae of the feminist movement. I had read it when I was a boy, I was delighted to be able to claim, and had honorably forgotten the incident. But in Boston they treat it as a living classic, and expect you to remember constantly and with appreciation this passage and that. I think that quite typical of the Bostonian weakness. It is the error of the clever high-school girl, it is the mistake of the scholastic mind all the world over, to learn too thoroughly and to carry too much. They want to know and remember Longfellow and Tennyson—just as in art they want to know and remember Raphael and all the elegant inanity of the sacrifice at Lystra, or the miraculous draught of Fishes; just as in history they keep all the picturesque legends of the War of Independence—looking up the dates and minor names, one imagines, ever and again. Some years ago I met two Boston ladies in Rome. Each day they sallied forth from our hotel to see and appreciate; each evening, after dinner, they revised and underlined in Baedeker what they had seen. They meant to miss nothing in Rome. It's fine in its way—this receptive eagerness, this learners' avidity. Only people who can go about in this spirit need, if their minds are to remain mobile, not so much heads as cephalic pantechnicon vans....

“IV

“The Wellesley Cabinets

“I find this appetite to have all the mellow and refined and beautiful things in life to the exclusion of all thought for the present and the future even in the sweet, free air of Wellesley's broad park, that most delightful, that almost incredible girls' university, with its class-rooms, its halls of residence, its club-houses and gathering-places among the glades and trees. I have very vivid in my mind a sunlit room in which girls were copying the detail in the photographs of masterpieces, and all around this room were cabinets of drawers, and in each drawer photographs. There must be in that room photographs of every picture of the slightest importance in Italy, and detailed studies of many. I suppose, too, there are photographs of all the sculpture and buildings in Italy that are by any standard considerable. There is, indeed, a great civilization, stretching over centuries and embodying the thought and devotion, the scepticism and levities, the ambition, the pretensions, the passions, and desires of innumerable sinful and world-used men—canned, as it were, in this one room, and freed from any deleterious ingredients. The young ladies, under the direction of competent instructors, go through it, no doubt, industriously, and emerge—capable of Browning.

“I was taken into two or three charming club-houses that dot this beautiful domain. There was a Shakespeare club-house, with a delightful theatre, Elizabethan in style, and all set about with Shakespearean things; there was the club-house of the girls who are fitting themselves for their share in the great American problem by the study of Greek. Groups of pleasant girls in each, grave with the fine gravity of youth, entertained the reluctantly critical visitor, and were unmistakably delighted and relaxed when one made it clear that one was not in the Great Teacher line of business, when one confided that one was there on false pretences, and insisting on seeing the pantry. They have jolly little pantries, and they make excellent tea.

“I returned to Boston at last in a state of mighty doubting, provided with a Wellesley College calendar to study at my leisure.

“I cannot, for the life of me, determine how far Wellesley is an aspect of what I have called Boston; how far it is a part of that wide forward movement of the universities upon which I lavish hope and blessings. Those drawings of photographed Madonnas and Holy Families and Annunciations, the sustained study of Greek, the class in the French drama of the seventeenth century, the study of the topography of Rome fill me with misgivings, seeing the world is in torment for the want of living thought about its present affairs. But, on the other hand, there are courses upon socialism—though the text-book is still Das Kapital of Marx—and upon the industrial history of England and America. I didn't discover a debating society, but there is a large accessible library.

“How far, I wonder still, are these girls thinking and feeding mentally for themselves? What do they discuss one with another? How far do they suffer under that plight of feminine education—notetaking from lectures?...

“But, after all, this about Wellesley is a digression into which I fell by way of Boston's autotypes. My main thesis was that culture, as it is conceived in Boston, is no contribution to the future of America, that cultivated people may be, in effect, as state-blind as—Mr. Morgan Richards. It matters little in the mind of the world whether any one is concentrated upon medieval poetry, Florentine pictures, or the propagation of pills. The common, significant fact in all these cases is this, a blindness to the crude splendor of the possibilities of America now, to the tragic greatness of the unheeded issues that blunder towards solution. Frankly, I grieve over Boston—Boston throughout the world—as a great waste of leisure and energy, as a frittering away of moral and intellectual possibilities. We give too much to the past. New York is not simply more interesting than Rome, but more significant, more stimulating, and far more beautiful, and the idea that to be concerned about the latter in preference to the former is a mark of a finer mental quality is one of the most mischievous and foolish ideas that ever invaded the mind of man. We are obsessed by the scholastic prestige of mere knowledge and genteel remoteness. Over against unthinking ignorance is scholarly refinement, the spirit of Boston; between that Scylla and this Charybdis the creative mind of man steers its precarious way.’’

— From The Future in America (1906) by H.G. Wells (1866-1946), prolific English author

Eccentricies of Beantown

Northeastern University’s Wayne Turner with the 1980 Beanpot after Northeastern won the annual Beanpot hockey tournament.

“Boston is both a world-class city, home to some of the best academic and medical institutions on the planet, and a quirkily parochial place, where one of the biggest annual sporting events involves college hockey players competing for a beanpot and where generations of baseball fans actively believed they were victims of a curse.’’

— Steve Kornacki (born 1979 and a native of Groton, Mass.) political journalist

Real beanpots.

Bringing them back at night

The Shubert Theatre at the Boch Center, in Boston’s threatre district.

The Paradise Rock Club (formerly known as the Paradise Theater) is a 933-person capacity music venue in Boston.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I love the title. Corean Reynolds has been named Boston’s “director of nightlife economy,’’ by Mayor Michelle Wu, in a post-COVID bid to re-energize consumers to patronize the capital of New England’s entertainment and eating-and-drinking sectors.

Her duties will include improving transportation and law enforcement.

Ms. Wu, like some other big city mayors, is animated by the desire to make the city less dependent on office workers as the move to remote work has slammed the city’s commercial real estate sector. This must include getting more people to live in the city, some via the conversion of office buildings into housing (much easier said than done) and, say, turning some streets into pedestrian-only ways.

I’m sure that Brett Smiley, Providence’s new mayor, will be watching how it goes

Aiming to decarbonize Boston’s Fenway neighborhood

Fenway–Kenmore neighborhood seen from Prudential Skywalk in 2012, with Fenway Park the dominant feature.

—Photo by Melikamp

Edited from a New England Council report (newenglandcouncil.com)

Boston-based Vicinity Energy has announced a partnership with IQHQ Inc., a life-sciences real estate development company, in which Vicinity’s carbon-free, renewable thermal energy will be used in IQHQ’s developments in Boston’s Fenway neighborhood.

Vicinity Energy has been active in efforts to decarbonize communities, from buildings to college campuses to entire neighborhoods. Now, with this partnership, the company is bringing this technology to Fenway. The first stop will be IQHQ’s development at 109 Brookline Ave., set to be Boston’s first entirely carbon-neutral building. To achieve these goals, Vicinity has been developing a technology referred to as ‘eSteam,’ an energy that uses decarbonized operators and does not require on-site boilers or chillers. Vicinity officials plan to start delivering eSteam in 2024.

“This eSteam partnership not only signifies our commitment to a clean energy future, but it also demonstrates the commitment from progressive, innovative industry leaders, like IQHQ, who are committed to lower carbon emissions and to combat climate change,” said Bill DiCroce, president and chief executive of Vicinity Energy.

Just a quick kiss

“Petite Confidence” (steel), by Franco-American artist Pascal Pierme, in his show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through March 18.

He says:

“{The late French President| Francois Mitterrand said, ‘I love the person who is searching, yet I am afraid of the one who thinks he has found the answer.’ In my life I have much more pleasure with the questions than with finding the answers, except when the answer is a new question. And that is where the obsession to create begins.

‘‘...For decades, balance, movement, inquiry, architecture and nature have been reoccurring themes in my work. I am interested in assimilating what is not supposed to fit – the combining of contrasting elements. My main ingredient is chemistry. I feel the movement and then freeze that moment in the interaction and take a ‘snapshot’ – capturing a split second in the evolution. Thereby creating something that is abstract and at the same time, quite figurative. As such, my work can be experienced as organic. It moves. It is alive, it comes from somewhere, it is going somewhere, and you feel that by what you see.

‘‘I try to sculpt in a way where I can change my mind until the last minute. My creativity is at its best when I push the medium of my work to its limit.’’

Those not entirely wasted hours at journo-favored bars

— Photo by Ragesoss

A 1936 anti-drinking poster by Aart van Dobbenburgh

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

For various reasons, going to New York City, as I did recently, reminds me of the bars that we newspaper and magazine reporters and editors used to patronize. This wasn’t a particularly healthy practice, but these places planted some evergreen memories.

Some of the joints I most remember:

Foley’s, in Boston, beloved of Boston Herald Traveler, Record American and Globe editors and reporters, especially scruffy police reporters, with their tales of gruesome or comic crimes and police and political corruption, and news and copy editors having their “lunch” at around 8:30 p.m. between edition deadlines.

Some actually consumed the bar’s pickled eggs as they knocked back their boilermakers --- a shot of whiskey followed by a beer, or pouring a shot of whiskey into their beers and then chugging that – or downing other, not very elegant beverages. I was often amazed that some of these journos could function at all under deadline pressure upon returning to the newsroom after “lunch” at Foley’s. Certainly many of them looked ill and aged fast. Some had noses that were tributes to the distillers’ art.

The older guys (and virtually all these colleagues were men) told vivid stories going back to the ’40s of life in what was then a gritty city. Others were taciturn, as if battered into silence by bad hours and what they had seen and heard on the job in a business in which grim news usually sells better than good.

Then there was the bar off Broad Street in Lower Manhattan where a couple of Wall Street Journal editing colleagues and I would occasionally retreat in mid-evening after work. (We’d stop working soon after listening to WQXR, then The New York Times’s radio station, to learn if we had missed a story that our biggest rival had so we could make necessary adjustments. The station helpfully broadcast a review of its next day’s Page One at 9 p.m.)

One night we came across what appeared to be a corpse on the sidewalk outside the bar that appeared to have been there for a while. A cop came along to deal with the body. (The neighborhood was virtually deserted at night in those days because few people lived there then and there were few food stores, etc., to serve them. Now there are many apartment buildings, put up during the off-and-on boom years from the mid-‘90s to COVID, and so it has much more of a 24/7 feel, though less than before the pandemic.)

In the bar we almost got into a fist fight with a drunk who insulted our colleague Ruth; in the event, he was evicted from the establishment.

I well recall the bar/restaurant in Wilmington, Del., called The Bar Door. That’s where some of us working for the News Journal, The First State’s statewide rag, then owned by the remarkably kindly DuPont family, would lunch at least once or twice a week. My colleagues there were the most abstemious of the newspaper types I hung out with in my career, usually just confining themselves to a Rolling Rock beer. And the food, especially softshell crab from nearby Chesapeake Bay, was good, so there was less drinking on empty stomachs.

The local pols, such as, I think, Joe Biden, then a recently elected U.S. senator, would show up to gossip. My favorite was Melvin Slawik, the charming New Castle County (which includes Wilmington) executive, who was a font of stories, including very funny, self-deprecating ones about himself. He later served time for perjury, obstruction of justice and bribery. He was one of the most likeable people I’ve ever met.

There was Le Village, a bar and restaurant dangerously close to the offices of the International Herald Tribune, in the affluent Paris inner suburb of Neuilly. Because French labor law mandates frequent work breaks, too many of the staff spent too much time there drinking, and, as at all journalist hangouts in those days, smoking. Several were what you might call merely recreational alcoholics. (Growing up, I learned enough about alcoholics, recreational and full time, to last me several lifetimes.)

As the finance editor, in charge of overseeing a third of the paper, I was sometimes put in the awkward position of trying to stop the working-hours drinking of people reporting to me. In one case, I had to remove an engaging and smart, but too often drunk, colleague from consideration for a promotion. In any case, labor law sharply restricted disciplining staffers. It was tough to hire people and even tougher to fire them.

There were other journo bars too, where I heard wild stories that could be the bases of a few novels and/or film-noirish movies, some of which stories were actually true. But my time in such places mostly ended about 30 years ago. One reason I’m still alive.

Oh, yes! There was a bar called Hope’s that was heavily patronized by Providence Journal people, and owned by two of them, but I only made a few clinical research visits.

Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990), the great English journalist, satirist, spy, womanizer and late-in-life religious fanatic, once said something to the effect that he regretted the smoking he did, but not the drinking, because of the stories and camaraderie he got out of the latter. But drinking and smoking are two devils embracing.

Notating the landscape

“Winter Rill” (acrylic on canvas), by Anni Lorenzini, in her show “In Sight: Notating the Landscape,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Feb. 3-26. She lives part of the year Waterford, Vt.

She writes:

"'All I could see from where I stood...' Here poet Edna St. Vincent Millay pinpoints the artists' charge; to paint what you see as you see it.

“I notate the landscape with random strokes, smears and smudges. These tangled dots develop into intricate patterns that form the earth and sky. I respond to the intimate structure of each landscape painting as I learn to paint with my chosen tools.

“I apply paint with everyday household tools like sponges, rags and squeegees. These tools come from my life, providing an authentic means for artistic expression as I live on this fragile and beautiful earth."

Waterford, Vt., seen across Moore Reservoir

— Photo by P199

Sam Pizzigati: The best case yet for raising taxes on billionaires

“Spirit of Ecstasy,” the bonnet ornament sculpture on Rolls-Royce cars, for which there were record sales last year.

— Photo by Jed

Via OtherWords. org

BOSTON

Sometimes the daily news about our billionaires just doesn’t make sense.

Last year, for instance, ended with a torrent of news stories about how poorly the world’s billionaires fared in 2022. Bloomberg tagged the 12 months that had just gone past “a year to forget,” with almost $1.5 trillion “wiped from the fortunes of the richest 500 alone.”

All global billionaires taken together, Forbes chimed in, lost $1.9 trillion in 2022. Some 148 of the world’s 2,671 billionaires even lost their billionaire status.

The year’s biggest billionaire losers? Some of America’s deepest pockets.

Larry Page saw his Google-driven fortune drop $40 billion. Mark Zuckerberg watched $78 billion evaporate off the wealth Facebook created for him. And Amazon’s Jeff Bezos had to swallow a minus $80 billion.

But honors for the biggest nosedive of all have to go to Elon Musk. The world’s richest man at the start of 2022, Musk ended the year losing both his top slot and some $115 billion from his personal fortune.

So did all these losses have our billionaires shaking in their boots? Did they start tightening their belts a bit in 2022? Spend less on the world’s most fabulously expensive luxuries?

Not exactly. In fact, not all.

The world’s most celebrated purveyors of pure extravagance actually registered record years in 2022. Rolls-Royce had its best-ever annual sales total, selling a record 6,021 “motor cars,” up 8 percent over 2021.

“Our clients,” Rolls-Royce’s CEO crowed on New Year’s Day, “are now happy to pay around half a million Euros for their unique motor car,” a sum equal to about $540,000 in the United States, the company’s single largest market.

“Our order book stretches far into 2023 for all models,” the Rolls-Royce chief added. “We haven’t seen any slowdown in orders.”

Lamborghini had an even better 2022, with 9,233 vehicles sold — a 10-percent jump over last year. The company’s biggest market? The United States. Americans drove off Lamborghini lots with 2,771 new cars in 2022. The automaker’s most popular model runs about a quarter-million.

Realtors who cater to the ultra-rich set had an equally boffo year in 2022.

In a down real-estate market, the highest of high-end residences still pulled in mega sums at closing time. The year’s top 10 home sales in the United States, notes the luxury-oriented Robb Report, “totaled roughly $1.165 billion, proving that, impending recession or not, luxury real estate will always be traded.”

How can all this luxury be? How can the richest of the rich be spending fantastic sums in a year when they’re seeing fantastic falls in their personal net worths?

Simple. In the realms of the super rich, losing a billion — or even many billions — makes no difference whatsoever in real daily life. Net worth down a few billion? You can still afford anything your heart could possibly desire.

No one alive today needs fortunes worth dozens of billions to live astoundingly large. A mere billion would suffice. So, truth be told, would a mere tenth of a billion. In the day-to-day lives of billionaires, a few billions or so have no practical significance — except when it comes to increasing their political power at the expense of the rest of us.

Taxing those billions to support the common good, on the other hand, could make an immeasurable difference in the lives of millions — and our democracy.

We need more than a dip in grand concentrations of private wealth. We need a world without billionaires.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

TD Garden will keep name at least to 2045

TD Garden, which was opened in 1995, when it was called the Fleet Center, after a disappeared New England bank.

TD Bank has renewed its agreement to keep its name on what many of us still call the Boston Garden, now officially the TD Garden, for an additional 20 years. Under TD Bank’s original 2005 agreement, its naming rights to the arena were set to expire in 2025, but that has now been extended to 2045. TD Bank is part of Toronto-based Toronto-Dominion Bank, a huge multinational financial-services company.

TD Bank will remain the official bank of the Boston Bruins until 2045. The Bruins’ home ice, of course, is at TD Garden. The Celtics are also based there. The bank is also committing $15 million to local programs, including free event tickets provided to people from underserved communities and funds to artists working on community projects.

In a 1994 photo, the old Boston Garden, built in 1928, and known for its smoky and gritty interior and occasional violations of the fire codes through overcrowding. A lot of people remember being taken there to see the Ringling Brothers circus. Ah, the smell of manure!

Boston’s best known aid to hallucination

Painting by J.S. Dykes, shown in exhibition of his paintings and prints in his Boston gallery through Feb. 17.

Prince William: Why Boston was the place for this

Remarks by Britain’s Prince William in Boston on Dec. 2 on awarding $5 million in grants in the Earthshot Prize program to five people with ideas on saving the planet from global warming:

"There are two reasons why Boston was the obvious choice to be the home of The Earthshot Prize in its second year. Sixty years ago, President John F. Kennedy’s Moonshot speech laid down a challenge to American innovation and ingenuity. 'We choose to go to the moon,' he said, 'not because it is easy but because it is hard.' It was that Moonshot speech that inspired me to launch the Earthshot Prize with the aim of doing the same for climate change as President Kennedy did for the space race. And where better to hold this year’s awards ceremony than in President Kennedy’s hometown, in partnership with his daughter and the foundation {John F. Kennedy Library Foundation} that continues his legacy.’’

"Boston was also the obvious choice because your universities, research centers and vibrant start-up scene make you a global leader in science, innovation and boundless ambition."

Adjust your attitude

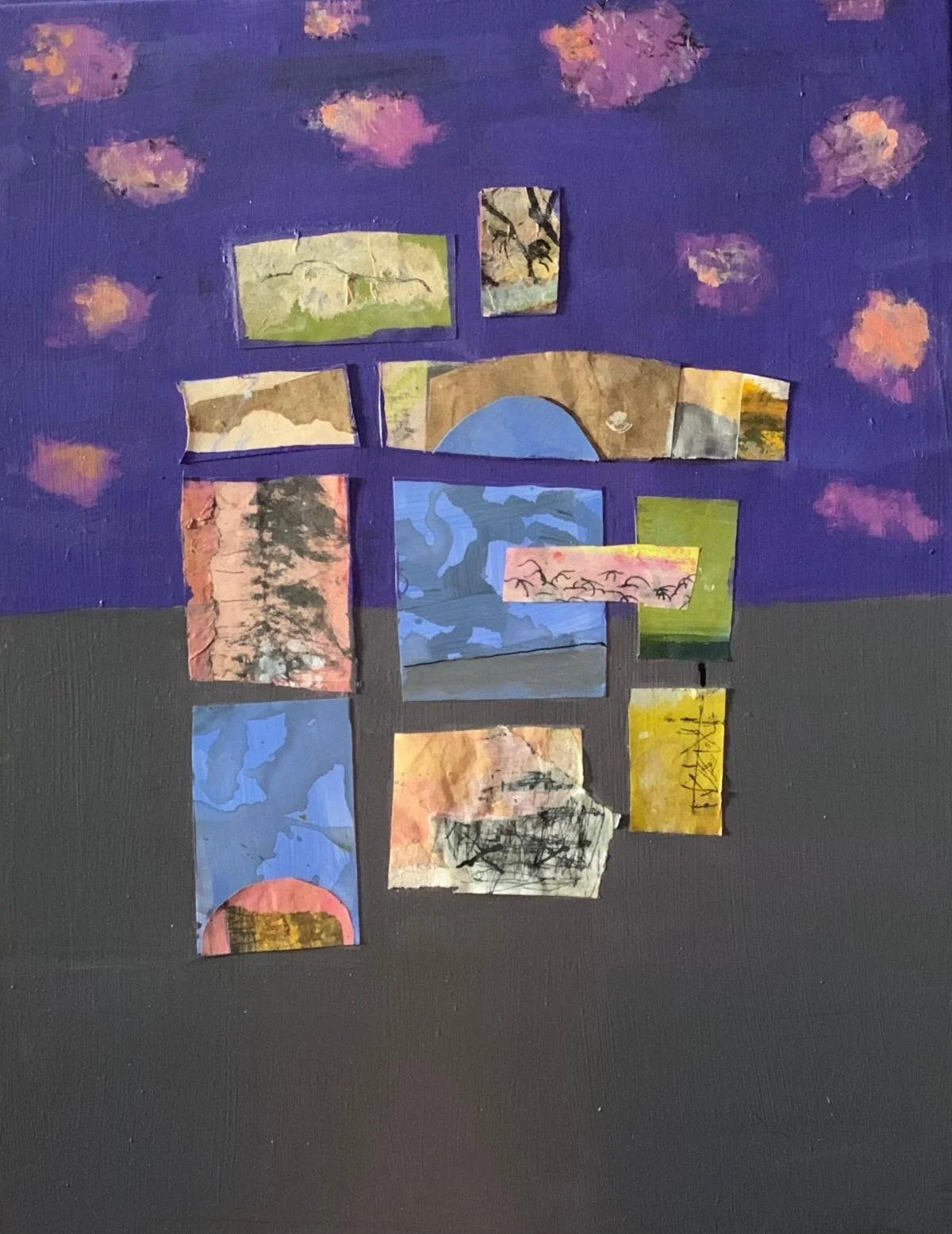

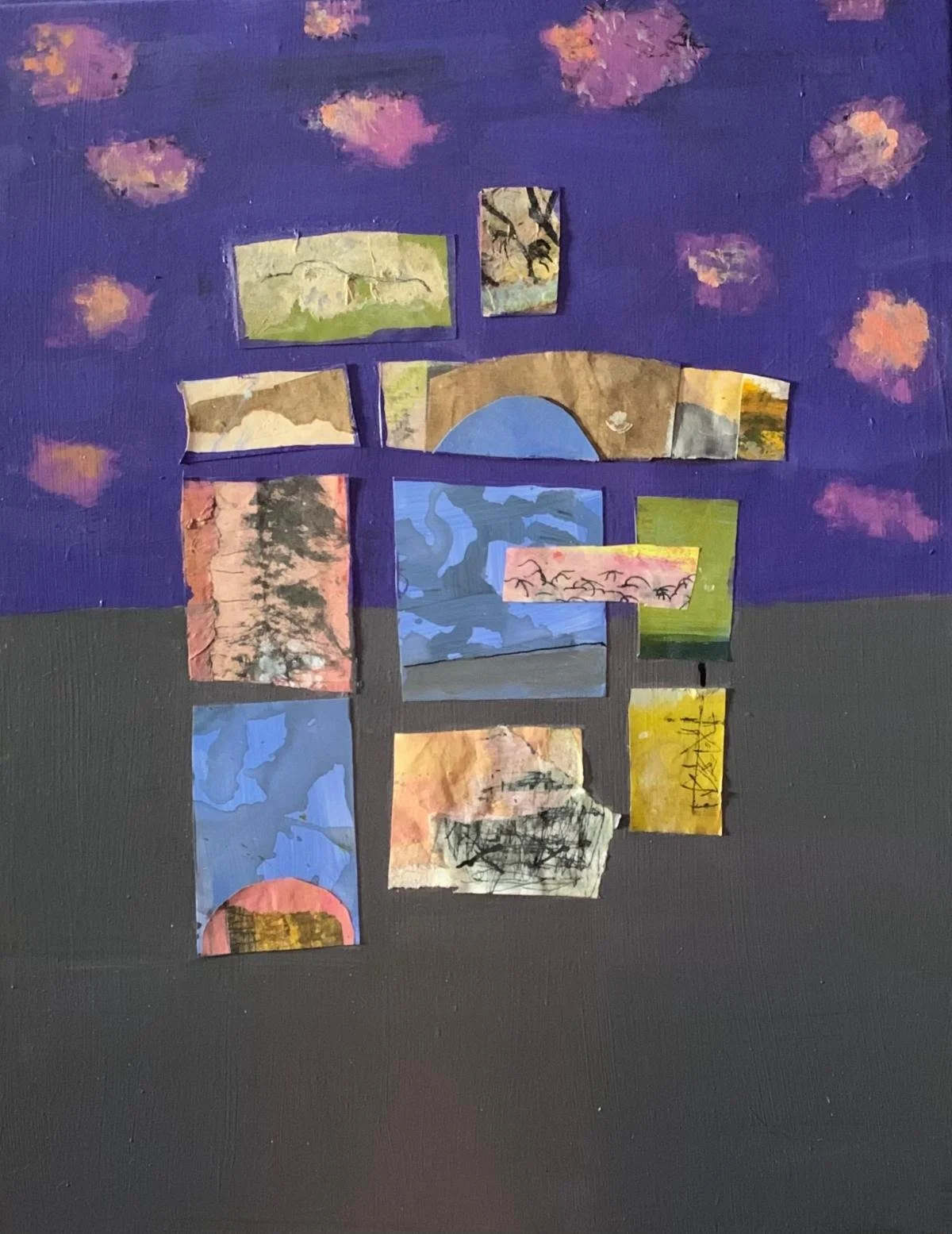

“Better Times” (mixed media), by Susan Leskin, in the group members show at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Jan. 13-29.

"It feels important right now to find and express visions of hope and lightness to counter the despair that many of us feel about the current state of the world. These collages reflect those visions for me."

Her artist statement says:

“My work frequently explores connectivity and disjunction. I enjoy creating images that are ambiguous and may be just on the edge of recognition. There is often a focus - explicit or implied - on the relationship between humans and nature.

”I use fluid acrylic paint and mediums, ink, pencil, and painted papers in my collages.’’

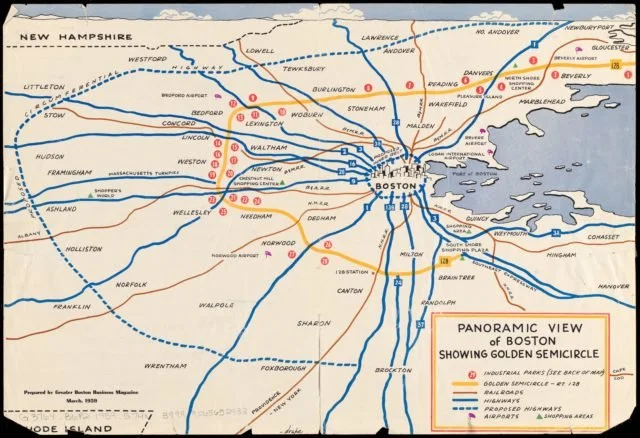

Boston area’s ‘Golden Semicircle’

A 1959 issue of Greater Boston Business Magazine contained a two-page map of the region’s “Golden Circle” showing industrial parks and shopping centers springing up along Route 128, which was being completed.

The building of Route 128 created was the nation’s first great high-technology region, fueled by the university complex in and around Boston. It was something of a model for North Carolina’s Research Triangle and what came to be called Silicon Valley in the San Francisco-San Jose area in California.

—Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library/Digital Commonwealth |

Ginette Saimprevil: The long road to education equality in Boston

At 46 Joy St., Boston, the Abiel Smith School, was founded in 1835 and is the oldest public school in the U.S. built for the sole purpose of educating African-American children. It houses the Museum of African American History.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Boston has had an extraordinarily long and tumultuous history as a fulcrum of the fight for the equal education of Black people.

Black Bostonians began petitioning the Massachusetts legislature for greater access to the public school system in 1787. In 1835, the Abiel Smith School opened—the first building erected for the sole purpose of housing a Black public school. However, conditions in this underfunded, segregated school were below standard, and the Black community continued to campaign for equal-education opportunities. While public school segregation was officially outlawed in 1855, de facto segregation continued to be the reality in Boston.

In 1965, the legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act, which outlawed segregation in public schools and, most significantly, defined segregated schools as those with a student body comprised of more than 50 percent of a particular racial group. Yet despite this ruling, Boston School Committee members refused to implement plans to integrate the city’s schools, and the relentless struggle for equal education continued.

In 1974, a federal court-ordered busing plan to end school segregation in Boston resulted in an eruption of protests and violence in the streets, as well as death threats against the judge in the case. Even innocent children being bussed were attacked. Despite the continuation of busing for more than a decade, white flight and a later decision to allow children in residentially segregated areas to attend neighborhood schools resulted in resegregation of many of Boston’s schools. By the 2017-18 school year, more than half of Boston Public Schools were profoundly segregated—even more than in 1965, according to a 2018 report by The Boston Globe. This situation persists to this day.

Boston’s segregated schools, with largely Black and Latinx students, tend to have a higher student-to-teacher ratio as well as older textbooks, lower quality facilities, fewer school counselors per student and other inequalities. This inevitably means that these students will face greater difficulties when it comes to gaining admission to college, completing their degrees and embarking on careers.

Secret sauce

At Bottom Line (BL), we seek to level the playing field by providing students with ongoing in-person advising from their senior year in high school through college graduation. Our trained, professional advisers deliver intensive, relationship-based, one-on-one advising, and they partner with students to select and gain admission to a college that is the best possible fit—academically, financially and culturally.

Our access advisers support high school seniors, based on their individual needs, in navigating the college application process using our LEAAD curriculum:

List: generating a list of colleges suited to students’ academic and financial situations.

Essay: brainstorm, writing and editing essays.

Applications: completing college applications.

Affordability: securing financial aid.

Decision: making a college choice.

Advisers and students review students’ options to select a college that best meets academic, financial and personal needs, with students receiving transition-to-college programming over the summer before their first college year.

The “secret sauce” in the Bottom Line approach is the holistic support—considering the whole student and building authentic relationships through our hybrid model. Our advisers conduct some in person meetings and provide remote support via video, phone and text communication.

In the college-access program, students meet with their advisers about 10 times a year. In the success program in college, students are paired with a success adviser who works with them one on one. Advisers offer regular support in the four areas most likely to cause a student to drop out of college: Degree, Employability, Affordability and Life, or DEAL.

This comprehensive support is provided for up to six years or until a student graduates. Our career-connections team and advisors provide coaching and support to help students/recent graduates build their social and career capital to launch mobilizing careers. Support includes mock interviewing, resume-writing workshops, help securing job shadows and internships, and networking events to prepare students for the workforce.

This work has a significant impact on our students and communities we serve. On average, our students earn nearly double their family income in their first job out of college. Our individualized college access, success and career connections support to students also results in a historic six-year graduation rate of 76 percent (more than double the national average).

Bottom Line’s model is recognized for its rigorous, externally validated proof-of-impact on college enrollment, persistence and graduation. An independent research report on “The Bottom Line on College Advising: Large Increases in Degree Attainment” confirms the impact of current BL programs and the notable potential for expansion. Researchers found that compared to the controlled group, Bottom Line students are 23 percent more likely to graduate from college. The researchers also added, “While the observed degree effects are quite consistent across different types of students, the fact that BL primarily serves students of color furthermore suggests that substantial expansion of the BL model could contribute to increased racial equity and mobility in the U.S.”

The estimated impact of advising on bachelor’s degree attainment is roughly as large as the (conditional on aptitude) gap in degree attainment between children from families in the first and fourth quartile of the income distribution.

I know from my personal as well as professional experience that the Bottom Line model works. My family emigrated from Haiti when I was 10. While my parents instilled in me a tradition of diligence and perseverance, they had no experience with higher education and were unable to help me navigate college-admissions and financial-aid processes. Fortunately, I was introduced to the BL program when I was a high school junior, and my adviser helped me find my way to a full tuition scholarship at Bowdoin College and a fulfilling career helping other students succeed.

Recently, our organization received a $15 million grant from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott. This grant will let us accelerate implementation of our strategic plan. This plan partly includes strategies to increase the number of students in Boston, New York City and Chicago, because we know there is a need for educational equity across the nation. The goal is to directly serve 20,000 students as well as reach 400,000 indirectly.

The Abiel Smith School, the oldest public school in the U.S. built for the sole purpose of educating African American children, now houses the exhibition galleries of the Museum of African American History. The very walls of this historic building are dedicated to telling the story of the Boston abolitionist movement and equal education. It is an inspiring place to reflect on the role of education at the core of equality and the continuum of persistence and progress in Boston’s Black community. It is a centuries old story that we hope to play a role in by ensuring that more students of color attain their college degrees.

Ginette Saimprevil is executive director of Bottom Line Massachusetts.

Karen Gross: Good things have happened in higher education during the pandemic

From Wikipedia

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

It would not be the least bit unusual to feel pessimistic about education in general and higher education in particular. Enrollments have been declining at many institutions across the education landscape. Budgets are tight at many. Shootings on campuses or unexpected deaths of students are far too frequent. So too are hazing and harassment. Discrimination is on the rise. The equity gap is widening. Faculty and staff are disenchanted and stressed; so are students. Mental wellness is a challenge for many. In short, the future doesn’t look bright. And the media are having a heyday sharing all the negative news.

Yet, I still have hope.

What alternative is there? If we don’t have hope, we stagnate and fail to make forward progress. Add to this that, philosophically speaking, hope is an attitude we hold that enables us to navigate difficult times with a forward-focused approach and a belief in the possibility of a better future.

Pandemic positives

There is a third reason that I see hope in education. It has to do with what we experienced and how we responded to the pandemic. It may seem counterintuitive to many, but we need to shift the lens through which we view the pandemic’s impact on education.

Most people have been focused on the pandemic’s negatives and how we eradicate or lessen all that has happened to students. There is an embedded assumption that we need to move “back to normal” to restore what the pandemic stole.

But this assumes that education was, pre-pandemic, in good shape, which is far from the truth. Even pre-pandemic, there were deficits in education that led to student failures in college and lack of access to quality postsecondary education for far too many low-income students. Pedagogy was suboptimal in many classrooms; lecturing was too common.

Demographics also impacted educational enrollment in a period before the pandemic started. And though there were approaches being researched and tried before the pandemic to improve higher education, many of these ideas were not implemented widely or fully. For example, social and emotional learning was gaining traction as were community schools and trauma-sensitive schools. Studies showing the value of enhancing the student-teacher relationship as it improves learning and self-control were available and used by some academic institutions.

But we have ignored the positives that occurred within the education landscape, As part of a book we are co-authoring, Harvard Medical School assistant professor of psychology Edward K. S. Wang and I have gathered a wide range of positives that actually occurred during the pandemic in terms of learning and psychosocial development. Yes, there were positives although they have often not been named or recognized. And these positives have not been replicated or scaled.

Here are just a few examples of these positives. With educators working online, they were able to see students engaging with their families and that often disclosed dysfunction that, but for online learning, would not have been observed. So, in a real way, educators had an opportunity to understand more fully who their students were/are. Consider too the fact that some students who did not engage in classroom discussion when learning was in-person, were able to participate more fully and more easily online; for these students, it is likely that the absence of teasing or peer pressure were eased online. With both in-person masked and socially distant learning and in the online environment, educators exercised increased strategies to engage and connect with students as well as connecting them to each other; the absence of the “normal” engagement approaches allowed for new avenues for connection. This prompted more project-based learning, pod learning and interactive activities, all educational positives.

What if we try to identify as many of these positives as possible and reflect on how did they come about? Then we can look at how to replicate and scale these positives for the betterment of higher education moving forward.

Begin with how the positives came to pass. Think about this phrase and its applicability: Necessity is the mother of invention. We know that in times of crisis, we develop strategies to cope and deal with what is before us. We may not know why what we develop during a crisis works, but there is no question but that crises create opportunities to change the status quo. Crises force us to act quickly too, because change is afoot and will not await the traditional timetables for change.

And, that happened in education at all levels. Educators figured out–not systemically to be sure–how to teach online (some for the first time). These educators wrestled with new ways to present materials. These educators struggled to engage students who were not all in the same room–engage them with the material, engage them with one another and engage them with the educator.

Take this example. Some college students were signing into classes, but were not engaging with learning. Their names, not faces, appeared. They muted themselves. In reality, some professors did not even know if the students were “there” in terms of paying attention. Some professors realized that “teaching as usual” was not an option. There needed to be different incentives, different approaches, different forms of engagement.

While new to online platforms and learning with their colleagues, professors tried new pedagogies. Some professors tried using polling to measure learning and class engagement. Some tried using breakout rooms, allowing students to process information and solve problems. Some turned to videos within the online environment and then encouraged discussion. Some used the chat room and other writing tools, recognizing that different students had different learning styles in the online world (something that was true pre-pandemic). Some had efforts to get students to “tune” in by having true/false questions, the answers to which involved showing or not showing faces on screen. Some professors came online early and left late to enable students to ask questions. Some professors used email and online platforms to message students between classes and make connections. Some had virtual office hours. Some had phone calls with students. The ways professors made online learning work, when they were previously unaccustomed to this learning modality, was remarkable.

These are all approaches which, absent the sudden crisis and need to move online or into hybrid mode, would not have happened. Yes, online learning did exist pre-pandemic, but it was not deployed in many traditional academic environments. And, in the process of changing how they taught their students, professors experienced changes too in how they viewed their roles and responsibilities as educators. In a sense, the shared Pandemic experience allowed students and educators to engage more fully and with greater understanding of each other.

Reflect on these examples.

Some students expressed frustration with their learning through online behavior like noticeably demonstrating disinterest; they multitasked or used their cell phones or were eating and drinking, suggesting the need for a professor to engage with them offline. And, seeing this behavior encouraged some professors to pause, take note and reach out, likely because they themselves were struggling to remain engaged.

Some students were unable to connect to the materials or the class and farmed off the work to outsiders. Recognizing this risk made professors create assignments that were unique and unavailable to purchase; they also designed engagement and its impact on class grading to operate differently so that students were unable disregard in-class participation.

Some students were dysregulated or disassociated, whether online or in-person; this means they were unable to concentrate and learn as a consequence of their traumatic pandemic (or other) experience. Some of these students were angry over the change in their educational experience and wanted no part of the new offerings. Some simply checked out even though they were present. Some acted out by stomping around, throwing paper, banging on their phone, being loud and argumentative and this could be witnessed online or in person. Professors and staff had to intervene and engage differently with these students, including through interventions with staff with experience in mental wellness.

The pandemic also brought policy flexibility with experimental efforts, pilot initiatives and changes in grading and discipline. Addressing NEBHE’s fall 2022 board meeting, Inside Higher Ed’s Doug Lederman noted that after trillions of dollars in federal aid helped higher education make faster adaptations during the pandemic, now, sadly, institutions and educators are returning to the old ways. In some ways, we can see parallels to the speed with which Covid vaccines were created; federal funding, collaboration and need were compelling forces.

Here’s the point: Educators teaching during the pandemic made changes to what they did and how they did it–even if they would not have made changes but for the Pandemic’s intervention. What they did not realize or understand is that the changes they made should not be limited to the Pandemic world. They employed approaches that are valuable still: engagement; connection and communication. And these changed learning strategies are trauma-responsive, even though they likely were not used with trauma amelioration at the forefront of professors’ minds. Indeed, the trauma literature abounds with references to the need for trusted individuals, ongoing connection and increased communication.

One strategy was to visualize this change in the midst of a crisis is to reflect on the following illustration. Pre-pandemic, things were like the lower left corner of this painting, largely ordered although certainly not homogeneous. During the pandemic, things changed, and the usual rules and formats and engagement changed and we became disordered in a sense. The order pre-pandemic was disrupted. We needed professors to change; we needed students to change; we needed institutions to change. And the changes were made as we went. We built the education plane as it was flying.

What does this all mean?

We need to identify the positives that occurred in education during the pandemic. Then we need to find ways to share these positives so they can be replicated and scaled. And we need to develop stickiness— how to make change last and endure so that we can see long-term improvement. Now, stickiness is tricky; how we can make social change is a topic worthy of future discussion.

As I reflect on the positive changes engendered by the pandemic, I am struck by the statement that accompanies an ancient Japanese form of pottery repair named Kintsugi. The broken shards are pieced together with gold and then it is said, “More Beautiful for Being Broken.”

In a very real way, inspired by Kintsugi, we need to make peace with the pieces the pandemic left behind and gather the positive shards and allow them to be part of education moving forward. This following illustration that I created is an effort to speak to the beauty that can be found if we piece together what is broken. And, by analogy, so it is with education.

With the Kintsugi philosophy in mind, here is what I see. I see that positive change happened in higher education during the pandemic, and for complex reasons, we have largely ignored it. Instead, we are enamored with the negatives the pandemic produced, which are plentiful to be sure.

We would be wise to look at the positives, some of which were detailed above, that occurred–within and outside individual classrooms and within the higher education community. And we can then name what happened during the pandemic us to move forward. If we do this, we can use what we did to better education for our students today and tomorrow.

A crisis created opportunity for change. Let’s not let that opportunity go to waste to play off a hackneyed phrase. That, at the end of the day, is my hope. And it is not chimerical hope. It is hope grounded in this reality: if we are willing to work to acknowledge and then use the positive change we created, we can improve higher education.

Karen Gross is a former president of Southern Vermont College and a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape and teaches at the Rutgers University School of Social Work. Her most recent book, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Solutions and Strategies for Educators, PreK-College, was released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press and was the winner of the Delta Kappa Gamma Educator’s Book of the Year award.

‘Realistic memories’ and dreams

“In Winter” (cast resin), by Memy Ish-Shalom, in his show “Dreams and Memories, ‘‘ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Dec. 2-Jan. 8. He’s an immigrant from Israel now living in Newton, Mass.

He says:

“My sculptures are an artistic response to realistic memories and to dreams or daydreams. But sometimes dreams turn into memories and memories become dreams.

“I reflect on childhood memories of being a son to my father and adult memories of being a father to my son. I also reflect on the deep sorrow that grew from losing my father.’’

John Harney: Many thanks, New England

John O. Harney

From, The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

In October, I wrote to NEBHE colleagues to let them know I would be retiring from the organization and the editorship of its New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE) in early January 2023.

While NEBHE has been my job, NEJHE has been my passion. I joined NEBHE in 1988 and, in 1990, became editor of NEJHE (then called Connection: New England’s Journal of Higher Education and Economic Development).

Thirty-four years for one outlet. Sometimes I forget I’m even that old.

I looked at the journal editions, printed on paper until 2010, as pieces of art (albeit imperfect ones) as much as a news service. The best issues I thought were like our own “Sgt. Pepper’’ album. Today, reminds me a bit of Bob Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm.’’

I’ll miss working with our distinguished authors, sometimes goading them into writing their bylined commentaries—usually for no fee. Those writers also happened to be our readers … a community of policymakers, practitioners and regionalists we described variously as “opinion leaders” in the old days, “thought leaders” more recently. All bound together by an interest in higher education and New England (which I recall was a tough audience to quantify for analytically retentive advertisers).

I’ll also miss the editorial “departments” we developed, such as Data Connection, a sort of spinoff of the Harper’s Magazine Index, but with a New England and higher education flavor. Reflective of a certain “NEJHE Beat,” these items—like a lot of NEJHE content—track along a unique constellation of issues anchored in higher education but also moored to social justice, economic and workforce development, regional cooperation, quality of life, academic research, workplaces and other topics that, together, say New Englandness.

In our print days, I was especially invested in my Editor’s Memo columns that opened every edition from 1990 to 2010.

A few of these Editor’s Memos noted the transition from Connection to NEJHE, an illness that forced me to take leave in 2007 and the journal’s shift from print to all-Web in 2010.

Many pieces looked at the future of New England. One touched on our mock Race for Governor of the State of New England. That exercise helped midwife New England Online, an attempt by NEBHE and partners to take advantage of then-new networking technologies to provide something of a clearinghouse of all things New England—a bit unfocused perhaps, but poignant in a region where, the “winner” of that fantastic New England governor’s race, then state Rep. Arnie Arnesen of New Hampshire, quipped that the capital of New England should not be, say, Boston or Hartford, but instead something along the lines of “www.ne.gov.” (See our house ad.)

The House that Jack Built focused on the first NEBHE president I worked with, Jack Hoy, who passed away in 2013. Jack was a mentor who pioneered understanding of the profound nexus between higher education and economic development that is now taken for granted and that served as the basis for the journal’s name, Connection.

Among other of these commentaries and columns, several focused on the magical relationship between higher-education institutions and their host communities. Even in the emerging age of a placeless university, there is no diminishing the correlation between campuses and good restaurants, bookstores, theaters and other amenities, driven by faculty, students and otherwise smart locals.

In this vein, I was personally sustained for more than three decades by NEBHE’s home in Boston. Despite its difficult racial past (which NEBHE and NEJHE have attempted to address), the Hub, and next-door Cambridge, comprise Exhibit A in such college-influenced communities. Indeed, our street in Downtown Crossing has offered a lesson in the region’s changing economy, being transformed from a strip of small nonprofits that wanted to be close to Beacon Hill, to dollar stores, to, most recently, chic restaurants and bars. The foot traffic, meanwhile, has become much more collegiate as Emerson College and Suffolk University have expanded downtown.

I noted in my letter to colleagues that I strongly believe that the regional journal is a key strength of NEBHE that should continue to be appreciated and bolstered.

For years, we characterized Connection and NEJHE as America’s only regional journal on higher education and its impact on the economy and quality of life. In addition, the topics we’ve covered are just too important to cast our gaze elsewhere. New England’s challenging demography—where some states now see more deaths than births—means there are fewer of us to nourish a workforce and exercise clout in Congress. This all makes our historic strength in attracting foreign students and immigrants to build our communities and industries all the more important. Growing chasms in income and wealth between chief executives and employees, meanwhile, agitate antidemocratic and racist forces. While too many critics diss snowflakes, dangerous trauma grows among students and staff. And a pandemic (that is not over) exposed our fault lines, but also showed the promise of joining together behind scientific breakthroughs … and behind one another.

NEBHE President Michael Thomas and I agreed that the weeks leading up to my retirement will provide opportunities to celebrate the journal’s four decades of contributions to the region—as well as to think about its future and the ways NEBHE can best inform and engage stakeholders going forward.

But these are tough times for independent-minded journalism—especially in the quasi-free press world of association journalism, where the goal is to be objective, but for a cause (and ours is generally a good one). NEBHE has launched a job search for a director of communications and marketing. To be sure, my functions at NEBHE also included PR and media relations and style maven (editorial style that is), and those too are key tasks that NEBHE must continue to fulfill. (Full disclosure, I always urged NEJHE authors to make their pieces “issue-oriented” and “avoid marketing.” The goal for the journal was to be thoughtful and candid.)

Just keep it real.

Here’s to the future of NEBHE and NEJHE.

John O. Harney is the executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Editor’s note: New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is a former member of the Advisory Board of The New England Journal of Higher Education.