Llewellyn King: Brilliant, brazen Murdoch’s two-tiered approach

Rupert Murdoch accepting the conservative Hudson Institute's 2015 Global Leadership Award.

One of the Fox “News” -affiliated TV stations

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have watched Rupert Murdoch’s career with admiration, irritation and, sometimes, horror.

His besetting sin is that he goes too far. The fault that has landed Fox News settling with Dominion Voting Systems for $787.5 million isn’t new in the Murdoch experience.

He is a publishing and television genius. But like many a genius, his success keeps running away with him — and then he must pay up. He does so without apology and without discernible contrition. Those who know him well tell me he treats his losses with a philosophical shrug.

Murdoch’s talent reaches into many aspects of journalism. He has nerves of titanium in business and a fine ability to challenge the rules — and, if he can, to bend them.

As an employer he is ruthless and at times generous and indulgent. I know many who have worked for Murdoch and they speak about the contradictions of his ruthlessness and his generosity, particularly to those who have borne the battle of public humiliation for him. Check out the salaries at Fox News and the London Sun.

The Murdoch story begins, as most know, when he inherited a newspaper from his father. He quickly formed a mini-news empire in Australia.

But Murdoch had his sights set — as many in the former British possessions do — on London and the big time there. While at Oxford, he was hired as a sub-editor at The Daily Express, then owned by another colonial, the formidable Lord Beaverbrook.

In 1968, Murdoch bought The News of the World, a crime-centric Sunday paper. The next year, he bought the avowedly left-wing Sun.

Here Murdoch showed his genius at knowing the makeup of the audience and what it wanted: He flipped The Sun from left politics to extreme right and, for good measure, stripped the pinups of their bras.

That was a hit with men, and the politics were a revelation: Murdoch had defined a conservative, loyalist and anti-European vein in the British newspaper readership that hadn’t been mined. He went for it and soon had the largest circulation paper in Britain.

After he bought the redoubtable Times and Sunday Times, the Murdoch invasion was complete. He had also been instrumental in the launch of Sky News.

Money rolled in and political power and prestige with it — although there is no evidence that he sought formal preferment, like a peerage.

On to New York and U.S. newspapers.

Here the formula of sex and nationalism foundered. He didn’t succeed as an American newspaper proprietor except for deftly keeping The Wall Street Journal a prestige publication.

However, he brilliantly – with several bold moves — built a television network. Then, in the cable division, he applied the UK formula: Give the punters what they want.

In Britain it was sex and nationalism. In America, it was far-right jingoism. Murdoch gave it to Americans just as he had given it to the British: in large helpings of conspiracy, paranoia and nationalism.

In his tabloids, royal and celebrity gossip was the mainstay after right-wing Euro-bashing and breast-baring. He paid well for sensationalism and that attracted a seedy kind of private investigator-journalist, prepared to go further and deeper than his or her colleagues. Corruption of the police was the next step, along with telephone bugging and other egregious transgressions.

Eventually, it all came tumbling down. Murdoch had to appear before a parliamentary committee, fire people and, in a strange move, he closed The News of the World, as though the inanimate newspaper had been breaking the law without anyone knowing.

In fact, he had gone too far. The joyful music of the cash register had led to a wilder and wilder dance.

He damaged his legend, his papers and all of Britain’s journalism. He also lost the opportunity to buy control of Sky News.

But Fox was a joy. Oh, the sweet music and the wild dance! Give them what they want all day and all night. Give them their heroes untrammeled and their own facts. And finally, the election results they, the punters, wanted to believe, not the ones that the polls posted.

You can see the two-tiered approach that has worked so well for Murdoch working again here. Some respectable publications and some vulgar money makers, like his respected The Australian and his raucous big-city tabloids; in Britain, the respected Times and Sunday Times and the ultra-sensational Sun; in America, the respected Wall Street Journal and the disreputable Fox Cable News and his other remaining newspaper, the skallywag New York Post.

For a remarkably gifted man, Murdoch can do some appalling things and has genius without bounds.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

‘A charmed antiquity’

“View of Boston,’’ by J. J. Hawes, c. 1860s–1880s

My northern pines are good enough for me,

But there’s a town my memory uprears—

A town that always like a friend appears,

And always in the sunrise by the sea.

And over it, somehow, there seems to be

A downward flash of something new and fierce,

That ever strives to clear, but never clears

The dimness of a charmed antiquity.

— “Boston,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935)

The leaves speak

“Shrine” (oil on linen), by New England painter Nancy Friese, in her show “Eloquent Landscapes,’’ at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, through April 29. See this video.

‘Newness on every object’

1850 lithograph

“These towns and cities of New England (many of which would be villages in Old England), are as favourable specimens of rural America, as their people are of rural Americans. The well-trimmed lawns and green meadows of home are not there; and the grass, compared with our ornamental plots and pastures, is rank, and rough, and wild: but delicate slopes of land, gently-swelling hills, wooded valleys, and slender streams, abound. Every little colony of houses has its church and school-house peeping from among the white roofs and shady trees; every house is the whitest of the white; every Venetian blind the greenest of the green; every fine day’s sky the bluest of the blue. A sharp dry wind and a slight frost had so hardened the roads when we alighted at Worcester, that their furrowed tracks were like ridges of granite. There was the usual aspect of newness on every object, of course. All the buildings looked as if they had been built and painted that morning, and could be taken down on Monday with very little trouble.’’

— From American Notes, by Charles Dickens (1812-1870), a travelogue detailing his trip to North America from January to June 1842.

Food fun and learning

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

What a fine project -- providing fresh food while helping kids learn about growing vegetables in containers year round at “Freight Farms’’ run by Boys & Girls Clubs south of Boston.

Here’s some background from, yes, Wikipedia:

“Freight Farms is a Boston-based agriculture technology company and was the first to manufacture and sell "container farms": hydroponic farming systems retrofitted inside intermodal freight containers. Freight Farms also developed “farmhand’’, a hydroponic farm management and automation software platform, and the largest connected network of hydroponic farmers in the world. The company has installed more than 200 farms around the world, on behalf of individuals, entrepreneurs, educational and corporate campuses, and soil farmers.

“In 2018 the company announced Grown by Freight Farms, an on-site farming service for institutions and organizations that would benefit from food grown on-site.’’ Good for places with the cool snap called “winter.’’

Different species

“Getting elected as a Republican in Massachusetts is very, very different from being elected as a Republican in New Hampshire.’’

— Corey Lewandowski (born 1973), a New Hampshire-based right-wing Republican political operative, lobbyist, political commentator and author closely associated with Donald Trump. His main home is in Windham, N.H.

The Searles Castle, in Windham, was built in 1905-1915 and was completed in 1915. It was intended to be a replica of the medieval Tudor manor of Stanton Harcourt, in Oxfordshire, England, but since most of the manor had been torn down in the 18th Century, the castle bears little resemblance to the historical structure. It’s now owned by a pharmaceutical company owner.

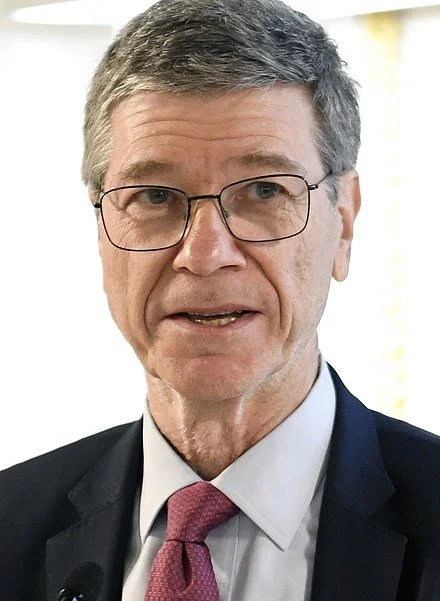

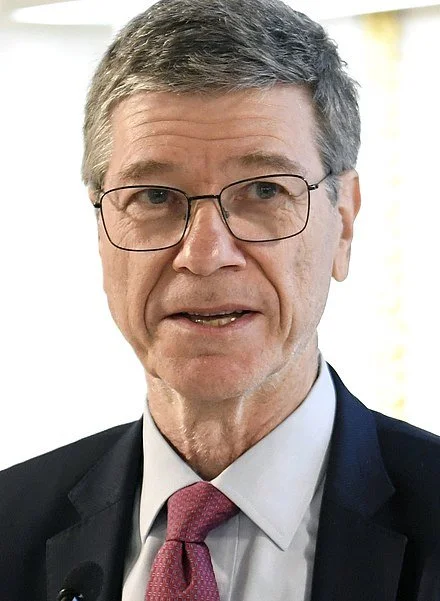

David Warsh: Sachs, Ukraine and the Harvard caper

Jeffrey Sachs

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is hard to feel much sympathy for Jack Teixeira, the Air National Guardsman from North Dighton, Mass., who is accused of sharing top-secret U.S. government documents with his obscure online gaming group. It was from there that, predictably, the secrets gradually slipped out into the larger world. Still, the news story that caught my attention was one in which a friend from the original game-group explained to a Washington Post reporter what he understood to have been the 21-year-old guardsman’s motivation.

The friend recalled that Teixeira started sharing classified documents on the Discord server around February 2022, at the beginning of the war in Ukraine, which he saw as a “depressing” battle between “two countries that should have more in common than keeping them apart.” Sharing the classified documents was meant “to educate people who he thought were his friends and could be trusted” free from the propaganda swirling outside, the friend said. The men and boys on the server agreed never to share the documents outside the server, since they might harm U.S. interests.

The opinion of a callow 21-year-old scarcely matters, at least on the surface of it. Discussions will quickly shift to the significance of the leaked information itself. Comparisons will be made of Teixeira’s standing as a witness to government policy, and judge of it, relative to others of similar ilk: Daniel Ellsberg, Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, and Reality Winner.

But Teixeira’s opinion interested me mainly because it mirrored views increasingly under discussion at all levels of American civil society. I thought immediately, for instance, of Jeffrey Sachs, director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University. Sachs is not widely understood to be involved in the story of the war in Ukraine. But since 2020, and the death of Stephen F. Cohen, of New York University, Sachs has become the leading university-based critic of America’s role in fomenting the war.

On Feb. 21, Sachs appeared before a United Nations session to present a review of the mysteries surrounding the destruction of Russia’s nearly complete Nord Stream 2 pipeline last September. The consequences were “enormous,” he said, before calling attention to an account by independent journalist Seymour Hersh that ascribed the sabotage to a secret American mission authorized by President Biden.

Despite a history of previous investigative-reporting successes (My Lai massacre, Watergate details, Abu Graib prison), Hersh’s somewhat hazily sourced story was not taken up by leading American dailies. In an apparent response to the attention given to Sachs’s endorsement of it, however, national-security sources in Washington and Berlin soon surfaced stories of their investigation of a mysterious yacht, charted from a Polish port, possibly by Ukrainian nationals, that might have carried out the difficult mission. Hersh responded forcefully to the “ghost ship” stories in due course.

Then on Feb. 28, at a time when English-language newspapers were writing about the year since Russia had boldly launched an all-out invasion of Ukraine, Sachs published on his Web site his own version of the story. “The Ninth Anniversary of the Ukraine War’’ is a concise account of Ukrainian politics since 2010. Especially interesting is Sachs’s analysis of U.S. involvement:

During his presidency {of Ukraine} (2010-2014), {Viktor} Yanukovych sought military neutrality, precisely to avoid a civil war or proxy war in Ukraine. This was a very wise and prudent choice for Ukraine, but it stood in the way of the U.S. neoconservative obsession with NATO enlargement. When protests broke out against Yanukovych at the end of 2013 upon the delay of the signing of an accession roadmap with the EU, the United States took the opportunity to escalate the protests into a coup, which culminated in Yanukovych’s overthrow in February 2014.

The US meddled relentlessly and covertly in the protests, urging them onward even as right-wing Ukrainian nationalist paramilitaries entered the scene. US NGOs spent vast sums to finance the protests and the eventual overthrow. This NGO financing has never come to light.

Three people intimately involved in the US effort to overthrow Yanukovych were Victoria Nuland, then the Assistant Secretary of State, now Under-Secretary of State; Jake Sullivan, then the security advisor to VP Joe Biden, and now the US National Security Advisor to President Biden; and VP Biden, now President. Nuland was famously caught on the phone with the US Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, planning the next government in Ukraine, and without allowing any second thoughts by the Europeans (“Fuck the EU,” in Nuland’s crude phrase caught on tape).

So, who is Jeffrey Sachs, anyway, and what does he know? It’s a long story. His Wikipedia entry tell you some of it. What follows is a part of the story Wiki leaves out.

Sachs was born in 1954. Having grown up in Michigan, the son of a labor lawyer and a full-time mother, he graduated from Harvard College in 1976. As a Harvard graduate student, he soon found a rival in Lawrence Summers, the nephew of two Nobel-laureate economists, who had graduated the year before from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sachs completed his PhD in three years, after being appointed a Junior Fellow, 1978-81. Harvard Prof. Martin Feldstein supervised his dissertation, and, three years later, supervised Summers as well. Both were appointed full professors in 1983, at 28, among the youngest ever to achieve that position at Harvard. Sachs collaborated with economic historian Barry Eichengreen on a famous study of the gold standard and exchange rates during the Great Depression. Summers was elected a Fellow of the Econometric Society in 1985, Sachs the following year.

Summers went to Washington in 1982, to serve for a year in the Council of Economic Advisers under CEA chairman Feldstein; in 1985, Sachs was invite to advise the government of Bolivia on its stabilization program. After success there, he was hired by the government of Poland to do the same thing: he was generally considered to have succeeded. In 1988, Summers advised Michael Dukakis’s presidential campaign; in 1992, he joined Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign. Sachs became director of the Harvard Institute for International Development.

In the early 1990s, Sachs was invited by Boris Yeltsin to advise the government of the soon-to-be-former Soviet Union on its transition to market economy. Here the details are hazy. Clinton was elected in November 1992. During the transfer of power, another young Harvard professor, Andrei Shleifer, was appointed to run a USAID contract awarded to Harvard to formally offer advice, thus elbowing aside Sachs, his titular boss. Shleifer had been born in the Soviet Union, in 1962; arriving with his scientist parents in the US in 1977. As a Harvard sophomore, he met Summers first in 1980, becoming Summers’ protégé, and, later, his best friend.

In 1997, USAID suspended Harvard’s contract, alleging that Shleifer, two of his deputies, and his bond-trader wife, Nancy Zimmerman, had abused their official positions to seek private gain. Specifically, they had become the first to receive a license from their Russian counterparts to enter the Russian mutual fund business, at a critical moment, as Yeltsin campaign for election to a second term. A week later Sachs fired Shleifer, and the project collapsed. Stories in The Wall Street Journal played a key role. And two years later, the U.S. Department of Justice file suit against Harvard and Shleifer, seeking treble damages for breach of contract. All this is describe in Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Enlargement) after Twenty-Five Years, a book I dashed off after 2016 as I was turning my hand from one project to another.

Soon after the government file its suit, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore in the “hanging chad” election of 2000, and a few months after that, Harvard hired former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers as its president. Harvard lost is case in 2004 in 2005, and Summers’s defense under oath of Schleifer’s conduct played a role – who knows how great? – in Summers’s overdetermined decision to resign his presidency in 2006. By then, Sachs had long since decided to leave Harvard. In 2002, after 25 years in Cambridge, he became director of Columbia University’s newly established Earth Institute, uprooting the pediatric practice of his physician wife as part of the move.

Sachs was always reluctant to talk about Harvard’s Russia caper. I haven’t spoken to him in 27 years. At Columbia, he enjoyed four-star rank, both in Manhattan, and in much of the rest of the world, serving for 16 years as a special adviser to the UN’s Secretary General, beginning with Kofi Annan. Time put his book, The End of Poverty,: Economic Possibilities for Our Time, on its cover; Vanity Fair’s Nina Munk published The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty, in 2013; glowing blurbs, from Harvard’s University’s Dani Rodrik and Amartya Sen, attested to his standing in the meliorist wing of the profession. In 2020, Sachs became involved, with a virologist colleague, in the COVID “lab-link” controversy, first on one side, then on the other. His stance on the Ukraine war had earned him plenty of criticism.

Sachs will turn 70 next year. He stepped down from the Earth Institute in 2016. As a university professor at Columbia, he teaches whatever he pleases. He writes mainly on his own web page, where he is always worth reading. But he is spread too thin there to influence more than occasionally the on-going newspaper story of the war. As a life-long dopplegänger to Larry Summers, however, Sachs casts a very long shadow indeed.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

‘Re-presented nature’

”Forestland” (pencil and gouache on Strathmore paper), by Boston area artist Hilary Tolan, in her show “In This Place,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston,. May 3-28.

Ms. Tolan’s artist statement:

“Hilary Tolan takes viewers into a world where nature is re-presented. She references both suburban gardens and the ‘wild’ nature of the forest and field. Tolan exploits images of fragmented nature and its possible meanings. She explores the fact that nature which was once alive and embedded in an environment, that existed as a part of a system, is now extracted and defunct of its original purpose. Tolan asks the viewer to consider the nature of time. In her work, she reflects the desire to keep and save things. Thoughts of memory, imagined landscapes and longing pervade much of its quiet beauty.’’

Walking to decide

Thee Marginal Way, in Ogunquit, Maine

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) walked 34 miles to Mount Wachusett, seen on the horizon, from his home in Concord, Mass

— Photo by Benabbey - Template:St. Benedict Abbey

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

For a few hours last Thursday, it seemed that you could see the buds on the trees open in front of you in five minutes in the warm wind.

The fine weather reminds me of the joys and usefulness of walks. They’re good for the body and the mind. A good walk can help clarify your thinking when you have a difficult and/or complicated decision to make.

My favorite walks:

Walking from our house down a pot-holed one-lane road to rocky headlands on Massachusetts Bay when I was a boy. It went through cedar and oak woods and by a marsh thick with reeds through which we cut trails and created little rooms. Then I’d look up to the left at a gray-shingled house on a granite crag in the woods where hawks always seemed to be flying. As the road descended slightly to almost sea level there was a cottage to the right – I assume mostly a summer place – on a beach that extended out to a mussel bed. In those days we didn’t eat these shellfish but used them solely for bait to catch mackerel.

Then, near the end of the road, came a little beach, more stones than sand, on the left and two granite headlands, both with quartz stripes, one of which was an island at high tide on which stood a brick mansion, with a swimming pool, which we thought exotic. It was connected to the road by a slightly arched bridge. It took me no more than about 15 minutes to get to this place from our house, but that was enough in the salty air to feel refreshed with new ideas.

When I worked in Lower Manhattan, in the ‘70s, I frequently strolled down Broadway to The Battery, at the tip of the island, to stare out on New York Harbor, usually rippled by a southwest breeze. There I might buy a hot dog, with sauerkraut, from a cart manned by an old man with a beard. He too admired the view, though he noted in some sort of Slavic accent that “It’s too bad the water’s so dirty and smelly.’’ This was before the newly created EPA had sprung into action.

The best days for these walks were Sundays, a work day for me. Hardly anyone lived in Lower Manhattan then – it was almost entirely offices, most in the financial sector -- and so the neighborhood had a kind of sweet sadness on weekends.

One day I was walking with my colleague Marty Hollander down Broadway, and he looked over at the new Twin Towers and said: “Someday someone’s gonna fly into them.’’ I’m trying to recall if he meant intentionally or by accident.

Many of my most vivid memories are from walking in New York, though I only lived there for four years, but visited many times before and after. I guess one’s memories are implanted more firmly when one is young.

Before my Lower Manhattan gig, I’d daily walk to and fro between the campus of Columbia University, where I was a grad student, and the apartment I shared about 25 blocks south. When I didn’t stroll up Riverside Park, I’d go up

Broadway, by the Thalia movie theater and strange eateries. One specialized in Mexican Chinese food. On my way back home, the usual hookers stood by at the entrance to a store that sold newspapers and magazines; they nodded with dignity as people walked by.

On the trip to Columbia, I’d plan out the day, sometimes stopping to jot down ideas and reminders.

In Providence, where I’d come to work at The Providence Journal, then in its last glory decades, I’d hike from our house in Fox Point and later the East Side among the architectural marvels of College Hill to the Journal Building and back again at night – often very late. The homeward-bound trip was fine exercise because of the steep hill. Later on, however, when I became an “executive’’ I found that I no longer had the time and drove. It was frustrating.A

I fixed a lot of problems on these walks, which I did in all weather, including the Blizzard of ’78.

Llewellyn King: To stressed out wait staff — please don’t ask me

The White Horse Tavern, in Newport, R.I., built before 1673, is believed to be the oldest tavern building in the United States.

Union Oyster House, in Boston, opened to diners in 1826, and is among the oldest operating restaurants in the United States. It’s the oldest known to have been continuously operating since it was opened.

Sometimes I dine in fancy restaurants with starched white tablecloths, napkins and professional waiters; waiters who don’t ask me throughout the meal, “How is your food so far, sir?” To pestering waiters, I want to say, “If I am capable of ordering a meal, I am also capable of calling you to the table and telling you if the soup is cold, the fish is old, or the bread is stale.”

That is an occasional indulgence and reminds me of the time when, between journalistic gigs, I worked at a high-end restaurant in New York. It even featured a big band, Les Brown and His Band of Renown.

My wife and I frequently dine somewhere local, usually a pub-type eatery. After a while, you learn what they are good at and order accordingly. You are resigned to vinyl tablecloths and flimsy paper napkins.

And I resign myself to being asked at least three times some variant of “How is it so far?” The answer, which like other diners I never have the moral courage to voice, should be, “Go away! You are spoiling my dinner with an insincere inquiry about the comestibles. I am eating, aren’t I?”

Maybe these waiters should ask the chef how the food is for starters — it is too late by the time it gets to the table.

The other dinner-spoiling intrusion, if you don’t have a professional, is the young waiter who wants you to be their life coach. It begins something like this, “I am not really a waiter. I am studying sociology. Do you think I should switch my major to journalism?”

I am tempted to reply, “I don’t know anything about sociology and it is damn hard to make a living in journalism these days. But there is a huge shortage of plumbers. You might try an apprenticeship somewhere and give up college.”

Give up waiting tables, too, I hope.

Please don’t misunderstand; I love restaurants. It cheers me up to eat out. I rank towns with a vibrant restaurant culture as high on the quality-of-life scale.

I am writing this from Greece, where a cornucopia of restaurant choices beckons everywhere, from avgolemono soup to taramasalata. I am all in.

When your mouth is full, the awful business of asking you how the chef’s skills are that day doesn’t seem to be part of the continental culture. That, I find, is an egregious weakness of the English-speaking nations.

But the business of interrogating you about your breakfast, lunch or dinner isn’t confined to when you are at the table. If you make a reservation online, using one of the booking services, you will be pursued afterward, sometimes for days, by annoying questions about the restaurant’s food and ambiance, and the service.

The multiple-choice questions follow a formula like this, “On a scale of one to 10, how would you rate your dining experience?” How do you explain that you loved the meal except for flies diving into your plate? Is that a one because of the flies, or a 10 because of the food? Splitting the difference with a five explains neither the failure nor the success.

A restaurant in Washington, D.C., once specialized in delicious roast beef sandwiches. They were the creation of the man who owned the restaurant, and he had cuts of beef, a sauce and rolls all made for the purpose.

But once I can remember, there was a distinct problem: A rat appeared next to a colleague when he was tucking into the sandwich.

How do you rate that dining experience when Yelp sends its questionnaire? Do you rate the food as a resounding 10 but the ambiance as one? How would the number-crunchers rate that in the overall dining experience?

Knowing how they like to seek averages, my suspicion is the roast beef eatery would have rated a five.

I read somewhere that during the Siege of Paris in 1870-71, an entrecote (a sirloin steak) was a slice of a rat. For years, I wondered about that place in Washington and its excellent roast beef sandwiches.

I would rather eat with an annoying server than a fraternizing rodent. Bon appetit!

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

An unhearing God

St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, where famed poet Wallace Stevens is said to have converted to Catholicism in his last days.

“If there must be a god in the house, let him be one

That will not hear us when we speak: a coolness,

“A vermilioned nothingness, any stick of the mass

Of which we are too distantly a part.’’

— From “Less and Less Human, O Savage Spirit,’’ by Wallace Stevens (1879-1955), Hartford-based poet, insurance company executive and lawyer.

‘Hazy images reveal stories’

“Labor” (colored pencil on paper), by Azita Moradkhani, at Samson Projects, Boston, through May 21.

The gallery says:

“Azita Moradkhani was born in Tehran where she was exposed to Persian art, as well as Iranian politics, and that double exposure increased her sensitivity to the dynamics of vulnerability and violence that she now explores in her art-making

“Moradkhani’s work in drawing and sculpture has focused on the female body and its vulnerability to different social norms. It examines the experience of finding oneself insecure in one’s own body. As Wangechi Mutu says, ‘females carry the marks, language, and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.’ In her drawings, the incorporation of unexpected images within intimate apparel intends to bring humor, surprise and a shock of recognition. Layers of hazy images reveal stories, with the hope of leaving a mark on the audience. Two worlds–birthplace and adopted home–live alongside each other in her work, joining intimately at a single point.’’

Chris Powell: Legislator’s drinking problem isn’t the biggest scandal; sneaky fuel tax; a No Labels presidential candidate?

1994 federal government poster

MANCHESTER, Conn.

By now nearly everyone who pays attention to Connecticut news knows of the state legislator who last year stood up to speak at the Capitol when she was drunk and lapsed into incoherence and who, a few weeks ago, was driving drunk when she crashed her car nearby.

The legislator has become so well known in large part because television stations have delighted in broadcasting video of her failing a sobriety test and getting arrested. There was nothing remarkable about the video. It was just like all failed sobriety-test videos except for the office of the person being arrested. She was hardly known statewide before her public intoxication; she was what in Parliament would be called a back-bencher. But now she is famous for being humiliated, and her legislative committee assignments are suspended.

Of course, she should have gotten treatment for her drinking problem before crashing her car and putting others at risk. But after the crash she quickly apologized publicly and began treatment. Beating an addiction is not easy; all may hope that she succeeds.

But the repeated broadcast of her arrest was only prurient and may not make it easier for her. It was as if the TV stations thought that she was Donald Trump.

Yes, after a long career as a grifter and four years of unprecedentedly disgraceful conduct in the nation's highest office, Trump may be irremediable. But the state legislator is just an ordinary person without bad intent who has a character weakness shared by many others, including others in elected office. There are many other things that Connecticut should be more ashamed of, but viewers of the state's TV news probably don't know.

xxx

HIDDEN TAXES AGAIN: Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and Democrats in the General Assembly are trying again to raise fuel taxes surreptitiously.

They are pushing legislation to authorize the commissioner of the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection to commit the state to interstate agreements requiring fuel businesses to buy and compete for a limited number of "carbon credits."

The cost to the businesses would be passed along in higher prices to retail fuel customers, who would blame energy producers and distributors, not the real culprit, state government.

The "carbon credits" scheme might be less objectionable if the legislature had to vote on such interstate compacts directly as ordinary legislation, if the governor had to sign it before it took effect, and if in doing so they were candid with the public about the inevitable result and explained why higher fuel costs were worth the supposed progress against "climate change."

But no. The Democrats want to pander to the climate extremists in their party without taking responsibility with everyone else.

If the governor and legislators want to raise fuel prices, they don't need any interstate compact. They can just raise fuel taxes in the open, as they have done before, though such taxes in Connecticut are already high.

xxx

FIND AN ALTERNATIVE: According to The Washington Post, the No Labels political organization, which includes former Connecticut U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman, aims to try to put its own candidate for president on the ballot in all 50 states in 2024.

No such candidate has been designated but the idea is to draw the likely major-party candidates in 2024 -- President Biden for the Democrats and former President Trump for the Republicans -- back toward the political center and away from their pandering to the left and right. Such movement might cause No Labels to endorse one or the other, refraining from offering its own candidate.

Biden supporters are said to be most afraid of the No Labels plan. One says: "The only way you can justify this is if you believe it doesn't really matter if it is Joe Biden or Donald Trump."

No, there is plenty of other justification. A third-party candidate can be justified if people believe, as many well may, that Biden and Trump are equally catastrophic, if in different ways.

To ensure its victory in 2024 one of the two major parties needs only to nominate a presidential candidate who is competent, moderate, relatively honest, sane and sentient.

But the parties don't yet seem to have noticed that Biden and Trump aren't.

Chris Powell (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com) is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Only way to start it

Kent Burying Ground, in Fayette, Maine. Established in 1880 by Elias Kent, it is unusual for its layout of concentric rings around a central monument.

Edwin Valentine Mitchell (1890-1960) in his book It’s an Old State of Maine Custom, recalls the story of the tourist being shown around town by a local who remarks to his guide how very old the townspeople seem:

“‘Seems as if everybody we meet is old,’ says the tourist.

“‘Yes,’ the guide admits, ‘the town does have a lot of old folks.’

“‘I see you have a beautiful cemetery over there,’ remarks the tourist a bit later.

“‘Yup,’ is the laconic answer. ‘We had to kill a man to start it.”’

Abenaki water

‘‘Water is Life,’’ by Francine Poitras Jones, in the group show “Nebizun: Water Is Life,’’ at the Bennington (Vt.) Museum through July 16.

The exhibition showcases the work of Abenaki artists of the Champlain Valley and Connecticut River Valley. Nebizun is the Abenaki word for water. The museum says the show "draws its inspiration from Native American grandmothers who have been doing water walks to pray for the water.’’

Satellite view of the Champlain Valley.

‘Great when you’re dejected’

Ogden Nash (1902-1971) and Dagmar (1921-2001), actress and television personality, on the TV game show Masquerade Party, in 1955. Nash graduated from and taught for a year at St. George’s School, in Middletown, R.I.

A Tribute to Ogden Nash

Time for fanfare, time for flash,

Time to honor Ogden Nash.

Lively, innovative, clever—

Humdrum absolutely never.

Nash is great when you’re dejected,

Since he’s apt to lift your spirits with a bouncy ending that is hardly what you expected.

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman is a Providence-based poet and a professor of philosophy at Brown University. (First appeared in Light, with a slightly different title)

John S. Long: These small geese prepare for an amazing journey

A Brant Goose

Brant Geese, our faithful winter visitors, will soon be flying to the northern coast of Greenland for breeding season. Many Brant use Narragansett Bay as their winter residence. Near the end of this month, these diminutive waterfowl (smaller than Canada Geese) will make an amazing journey of more than 2,500 miles across the frigid Bay of Fundy, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, the Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay.

Here along Narragansett Bay, rafts of Brant feed on eel grass, often staying close to shore, where they create a cacophony of gabble. As I recently watched them on Gaspee Point, in Warwick, R.I., the chilly wind was rattling through leafless trees behind me. Brant swim close and parallel to shore because they need sandy grit to aid their digestion of eel grass. Their white rumps bob like corks, and they never seem to tire from swimming directly into waves.

As I looked far to the east, the tugboat Morgan Reinauer was pushing a barge from Perth Amboy, N.J., north toward Providence, where it would soon dock at the Motiva terminal, near Corliss Cove, close to Allens Avenue.

John S. Long lives in Warwick, R.I.

Mounts to go missing in the emulsion

At the summit of Mt. Kearsarge, in Merrimack County, N.H.

“In fifteen years

Monadnock and Kearsarge

…will turn

invisible….’’

— From “Scenic View,’’ by New Hampshire-based poet and essayist Donald Hall (1928-2018)

Mount Monadnock, as painted by Richard Whitney in “Monadnock Orchard’’

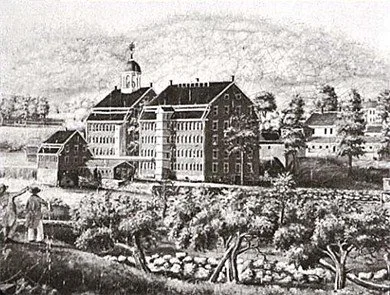

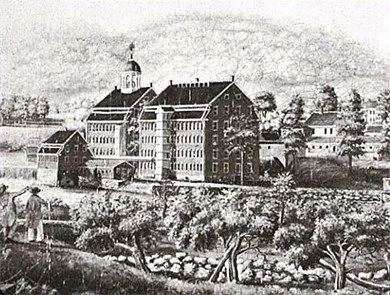

‘Wages will be low’

The Boston Manufacturing Company, shown in this engraving, made in 1813–1816, was based in Waltham, Mass. The company was an early developer of the New England textile industry by building water-powered textile mills along suitable rivers and developing mill towns around them. The building here was said to be the first integrated spinning and weaving factory in the world.

“But the time will come when New England will be as thickly peopled as old England. Wages will be as low, and will fluctuate as much with you as with us. You will have your Manchesters and Birminghams; and, in those Manchesters and Birminghams, hundreds of thousands of artisans will assuredly be sometimes out of work. Then your institutions will be fairly brought to the test.”

— Thomas B. Macaulay (1800-1859), English historian and politician.