What the market will bear

Video: History of Ivy League sports.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A suit by two basketball players, one a former Brown University player and one still playing there, alleges unfair, oligopolistic collaboration in sports programs by the Ivy League. The plaintiffs assert that the eight-college association’s policy of not offering athletic scholarships amounts to a price-fixing agreement that denies athletes proper financial aid and other payment for their services. The duo seems to have wanted to be treated as employees.

This case is absurd. These athletes have not been compelled to attend an Ivy League school. If they didn’t like these institutions’ long-established policies, they could have gone to many other places, some also called “elite,’’ in search of big bucks.

When the Ivy League as a formal organization was founded, in 1954, the ban on athletic scholarships was meant to be seen as fending off the corrupting commercialization of the sacred groves of academia and promoting the ideal, however naïve, of the “scholar-athlete

Complaints about price-fixing in the league go way back, spawned in part by the curious similarity of Ivy institutions’ tuitions. Consider this.

These schools charge what the market will bear, which is a lot when it comes to “The Ancient Eight.’’ Such is the American obsession with social status, they’ll continue to draw many more applicants than can be admitted, including top-notch athletes in search, above all of an education.

Landscape painter who broke barriers

“Landscape” (oil painting, 1870), by Robert S. Duncanson, at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art.

The museum says:

“Robert S. Duncanson is considered a member of the second generation of Hudson River School painters and is celebrated for his idyllic pastoral scenes of peaceful rivers and verdant mountains. Successful during his lifetime, he was known in the 1800s by American press as the ‘best landscape painter in the West,’ and London newspapers hailed him as an equal to his British contemporaries. Born a freedman in Seneca County, N.Y., in 1821 to mixed-race parents, Duncanson moved to the prosperous city of Cincinnati in 1840 to pursue a career in the arts, and he taught himself by painting from nature and by copying reproductions of works by Hudson River School masters. In the late 1840s, he befriended local landscape painters Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910) and William Louis Sonntag (1822-1900), with whom he took numerous sketching trips, including a European Grand Tour with Sonntag in 1853. In the ensuing years, Duncanson traveled throughout North America and Europe, exhibiting and selling work with great success, despite being excluded from many of the expositions in America that his white peers could participate in. His paintings commanded up to $500 per work—a very high sum at the time. Duncanson died at 51, and while his work fell into obscurity for many decades, he is now recognized as a premier 19th-Century landscape artist, who broke barriers and paved the way for landscape painters and Black artists for generations to follow.’’

We’ll settle for spring

“The Garden of Eden” (painting), by Massachusetts artist Eileen Ryan, at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, N.H., March 22-April 16.

She tells the gallery:

“I have many ideas pulsing through me at once and I have found that they are visually represented in two distinct ways in my art. The first is an organized approach to exploring concepts and questions. In a methodical manner using a naturalistic aesthetic I hypothesize and create around my findings. The second is through painting, where color and form begin without a plan and the questions and concepts are revealed at the end of the painting. This process takes trust and often leads to discovering things about myself and my subconscious.

“Painting for me feels like diving into the unknown, with ideas and facets of my self glinting throughout and the full spectrum only being revealed in the end of the painting. It’s like I am searching for the questions in my paintings, and answering them in my installations.

“This series of paintings documents recurring dreams I have had since I was a child. The settings range from magical dreamscapes to nuclear nightmares often including idols from my Catholic upbringing and mythical characters from stories I grew up listening to. These narratives are about the balance of power, warnings from the deep, and mystics representing creative energy and greed.’’

Portsmouth, N.H.

David Warsh: Say goodbye to the Monroe Doctrine

John Quincy Adams, who as President James Monroe’s secretary of state, was one of the fathers of the Monroe Doctrine, which was announced on Dec. 2, 1823.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Everybody agreed that the language was blunt. China’s president, Xi Jinping, last week told a national audience, “Western countries led by the United States have implemented all-round containment, encirclement and suppression of China, which has brought unprecedented grave challenges to our nation’s development,” Xi was quoted as saying by the official Xinhua News Agency.

The next day Gen. Laura J. Richardson, commander of the U.S. Southern Command, which is responsible for South America and the Caribbean, testified before the House Armed Services Committee that China and Russia were “malign actors” that are “aggressively exerting influence over our democratic neighbors…” She continued:

Among other activities, China has built a massive embassy in the Bahamas, just 80 kilometers (50 miles) off the coast of Florida. “Presence and proximity absolutely matter, and a stable and secure Western Hemisphere is critical to homeland defense.

The day after that, Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to re-establish diplomatic ties, The Middle East powers have a long history of conflicts. China hosted the talks that led to the breakthrough. Peter Baker, of The New York Times, wrote,

This is among the topsiest and turviest of developments anyone could have imagined, a shift that left heads spinning in capitals around the globe. Alliances and rivalries that have governed diplomacy for generations have, for the moment at least, been upended.

With good books piling up on my side table – Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives (Yale, 2022), by Stephen Roach; Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (Norton, 2022), by Hal Brands and Michael Beckley; Cold Peace: Avoiding the New Cold War (Liveright, 2023), by Michael Doyle – I decided instead to look back at a 12-year old book, Time to Start Thinking: America in the Age of Descent (Atlantic Monthly Press), by Edward Luce.

Roach, an economist, is a former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia. Brands, a historian, is a professor at Johns Hopkins University. Beckley, a political scientist, is an associate professor at Tufts University. Michael Doyle, a political scientist, is a professor at Columbia University.

But Luce is the U.S. national editor and columnist of the Financial Times, and his column last week appeared under the headline, “China is Right about U.S. Containment,”

[L]oose talk of U.S.-China conflict is no longer far-fetched. Countries do not easily change their spots. China is the middle kingdom wanting redress for the age of western humiliation; America is the dangerous nation seeking monsters to destroy. Both are playing to type.

The question is whether global stability can survive either of them insisting that they must succeed. The likeliest alternative to today’s U.S.-China stand-off is not is not a kumbaya meeting of minds but war.

When I picked up Luce’s The Time to Start Thinking, what struck me was how pessimistic his tone was. He had taken nine months off from his newspaper, traveling for six months and writing for three. He recorded encounters with all kinds of Americans, mostly powerful, some without power. His title came from the Sir Ernest Rutherford, winner of the 1908 Nobel Prize in Chemistry: “Gentleman, we have run out of money. It is time to start thinking.” I was reminded immediately of Aaron Friedberg’s The Weary Titan: Britain and the Experience of Relative Decline, 1895-1905.

Luce was writing in the aftermath of a lengthy recession, the Tea Party election, the 2008 financial crisis, and the debacle of the U.S. war in Iraq. The last chapter begins, “Why the coming struggle to reverse America’s decline faces long odds.” It concludes, “The truth is America’s stock has been falling around the world for quite a while…. Simply proclaiming the superiority of the American model is not helping anyone’s credibility.” Ahead lay the presidencies of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, and an ill-understood war in Ukraine.

Yet last week Luce was warning against the folly of trying to “contain” China’s expansion on the basis of the Cold War blueprint that worked well against the Soviet Union, encouraging the U.S. to compete on its merits instead. “Unlike the USSR, which was an empire in disguise, China inhabits historic boundaries and is never likely to dissolve. The U.S. needs a strategy to cope with a China that will always be there… Betting on China’s submission is not a strategy.

Instead, Luce counseled, the U.S. should muster its revolve and rely on its advantages. It has “plenty of allies, a global system that it designed, better technology, and younger demographics.” China is aging, its growth is slowing, though its leaders nurse ambitions not to change, but to set the rules of the game. The big difference that Luce stressed in 2012, while China is still flush, the US has overspent.

So what will it be? War over Taiwan? A symbolic moon-race to AI? Or a sometimes-smoldering era of systemic competition in all four corners of the earth? We are not out of money, but it is well past the time to start thinking.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

‘Balanced on a human scale’

Old Constitution House, in Windsor, Vt., where the Constitution of the Vermont Republic was signed, in 1777.

“When people who have never lived in New Hampshire or Vermont visit here,

they often say they feel like they've come home. Our urban center, commercial

districts, small villages and industrial enterprises are set amid farmlands and

forests. This is a landscape in which the natural and built environments are

balanced on a human scale. This delicate balance is the nature of our

’community character.’ It's important to strengthen our distinctive, traditional

settlement patterns to counteract the commercial and residential sprawl that

upsets this balance and destroys our economic and social stability."

~ Richard J. Ewald, in his book Proud to Live Here.

American Precision Museum at the old Robbins and Lawrence factory, in Windsor. The building is said to be the first U.S. factory at which precision interchangeable parts were made, giving birth to the precision machine-tool industry

‘The dead ripen’

— Photo by Gerthorst78

“….The creek swells in its ditch;

the field puts on a green glove.

Deep in the woods, the dead ripen,

and the lesser creatures turn to their commission….’’

— From “Jug Brook,’’ by the Cabot, Vt.-based poet Ellen Bryant Voigt. Cabot is where Cabot Creamery, a producer and national distributor of dairy products, is based.

‘Exaltation of the domestic’

“Anatolia’’ (watercolor), by Randolph, Mass.-based Annee Spileos Scott, in her show “Mapping My DNA,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, April 7-30.

She told the gallery:

"I have always been drawn to the ancient civilizations of Eurasia,

reveling in the brilliant colors and obsessive patterning. I was not

yet cognizant of the fact that many of them are in my DNA.

During the lockdown, I was encircled by family heirlooms and

souvenirs of my global travels from many of these cultural

destinations. Still lifes, inspired by these precious objects and the

results of my DNA testing, converged into metaphors for my

ancestral roots. The process of creating these paintings provided

beauty and salvation from the dark outer world of the pandemic.

The work celebrates women, keepers of cultures and tradition.

The exaltation of the domestic, displayed in arrangements of both

opulent objects and those of the everyday, reveal history, memory,

and a sense of belonging to a long line of women in my ancestry.

National fruits and flowers were added as organic elements,

symbolizing the source of all life which inhabits each region.’’

A cabin of the Ponkapoag Camp (established in 1921), of the Appalachian Mountain Club, on the eastern shore of Ponkapoag Pond in Randolph. The camp has 20 cabins, dispersed across a wooded area, that typically each sleep 4-6 people. No electricity or potable water is available at the camp; untreated water may be taken from the pond. In the summer the camp also makes available a few tent sites for camping. It’s near Great Blue Hill, at 635 feet, the highest point in Greater Boston.

Who makes this stuff?

The June 1, 2011 tornado that killed three people in and around Springfield, Mass.

— Photo by Runningonbrains

“I reverently believe that the Maker who made us all makes everything in New England but the weather. I don’t know who makes that, but I think it must be raw apprentices in the weather clerk’s factory who experiment and learn how, in New England, for board and clothes, and then are promoted to make weather for countries that require a good article, and will take their custom elsewhere if they don’t get it….’’

–Mark Twain (1835-1910)

Too much to take in

Untitled, (Crossed Arms) (archival inkjet print from original Kodachrome transparency), by Boston area photographer Karl Baden, at the Anderson Yezerski Gallery, Boston.

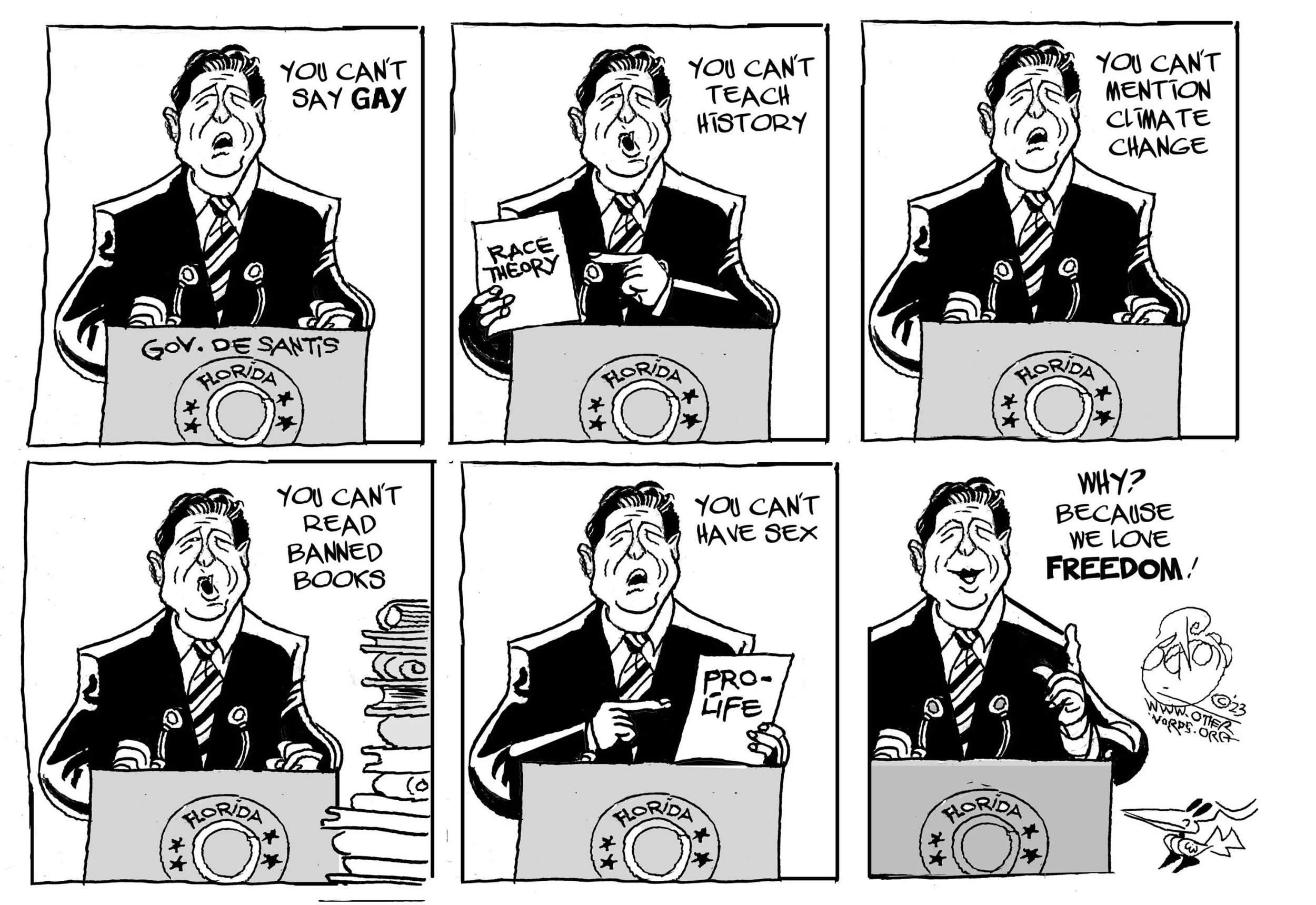

Chris Powell: Why would anyone want to build inexpensive rental housing?

A 1945 comic explaining World War-era rent control under the U.S. Office of Price Administration.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Exclusive zoning may not be the only reason that little inexpensive rental housing is being built or renovated in Connecticut. Anyone interested in the housing issue would do well to read the fascinating report about a day in housing court published March 5 in The Day of New London. It was written by journalism students from the University of Connecticut.

The court was full of people whose landlords were trying to evict them for chronic failure to pay rent. Some of the delinquent tenants were hard-luck cases. Others were victims of their own irresponsibility in life. An indulgent judge, court mediators and lawyers provided to the tenants by state government tried to arrange payment solutions and forestall evictions.

But most of these efforts were probably impractical from the start. In the end even patient and understanding landlords ended up seriously cheated. Evictions were dragged out for months but not prevented since the tenants simply couldn't or wouldn't pay.

“If you need something," one landlord said, "you can't just take it, like a coat if you're cold. Yet if you take my product -- time, space -- and don't pay, it's not illegal. ... If someone steals from you, you can be made whole. But my product is gone, used, consumed.”

The Day's report indicated just how mistaken the clamor at the state Capitol for rent control is, for the troubled people in housing court often can't pay any rent. They hold on by using the court to expropriate their landlord, sometimes for most of a year.

Rent control would be expropriation. But in housing court expropriation is already policy.

With rent control possibly coming on top of the expropriation any delinquent tenant can arrange in housing court, why should anyone want to get into the less-expensive rental business in Connecticut, even if exclusive zoning is overthrown as it should be?

And yet the only solution to the housing problem is to increase supply.

Submarine maker Electric Boat, in Groton, just across the river from New London, plans to hire thousands more workers over the next few years. But no one has announced plans to build thousands of housing units for the new workers to occupy nearby. EB's growth will push housing costs way up.

The problem bigger than the housing shortage is Connecticut's growing population of people not equipped to support themselves and their families -- people who are uneducated, unskilled, and often demoralized. Meanwhile industry in the state is unable to find qualified applicants for tens of thousands of jobs with good salaries and benefits. (Contrary to the premise of public education in Connecticut, giving high school diplomas to people who never mastered their schoolwork doesn't make them educated.)

Many people whose evictions are prolonged in housing court are in effect long-term welfare cases. To reduce evictions during the virus epidemic, state government has reimbursed landlords for some unpaid rents. The program continues but many tenants have exhausted the benefit. Maybe it should be enlarged to become like the Section 8 housing voucher program.

But housing the incapable is government's responsibility, not the responsibility of any landlord. That's why delinquent tenants aren't really the ones expropriating the people who provide rental housing. The expropriating is being done by government.

Is Accountability Illegal?

The dumbest non-sequitur of government in Connecticut is thriving at the top of the state's system of what styles itself higher education.

The Board of Regents for the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities, which runs the community colleges, still refuses to explain what happened with the firing and reinstatement of Manchester Community College CEO Nicole Esposito two years ago. Esposito sued, charging sex discrimination and retaliation for her questioning financial improprieties, and quickly got her job back and $775,000 in damages.

A spokesman for the board says that it won't comment on personnel matters that have been resolved or allegations that have been withdrawn.

But why not? Is accountability illegal in Connecticut now?

No, the law doesn't forbid explaining when so much money has been squandered. Governor Lamont and state legislators should press the point.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com).

Your eyes will get used to it

“August” (oil), in “Ocean Views II,’’ by Nick Paciorek, at the Feinstein Gallery at the University of Rhode Island’s Providence campus. He’s based at the Pitcher-Goff House art center, in Pawtucket, R.I.

Michelle Andrews: When to ask for an in-person medical visit instead of a virtual one

“As a consumer, you should do what you feel comfortable doing. And if you really want to be seen in the office, you should make that case.”

— Dr. Joe Kvedar, Harvard Medical School professor and former chairman of the American Telemedicine Association

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept the country in early 2020 and emptied doctors’ offices nationwide, telemedicine was suddenly thrust into the spotlight. Patients and their physicians turned to virtual visits by video or phone rather than risk meeting face-to-face.

During the early months of the pandemic, telehealth visits for care exploded.

“It was a dramatic shift in one or two weeks that we would expect to happen in a decade,” said Dr. Ateev Mehrotra, a professor at Harvard Medical School whose research focuses on telemedicine and other health-care delivery innovations. “It’s great that we served patients, but we did not accumulate the norms and [research] papers that we would normally accumulate so that we can know what works and what doesn’t work.”

Now, three years after the start of the pandemic, we’re still figuring that out. Although telehealth use has moderated, it has found a role in many physician practices, and it is popular with patients.

More than any other field, behavioral health has embraced telehealth. Mental-health conditions accounted for just under two-thirds of telehealth claims in November 2022, according to FairHealth, a nonprofit that manages a large database of private and Medicare insurance claims.

Telehealth appeals to a variety of patients because it allows them to simply log on to their computer and avoid the time and expense of driving, parking, and arranging child care that an in-person visit often requires.

But how do you gauge when to opt for a telehealth visit versus seeing your doctor in person? There are no hard-and-fast rules, but here’s some guidance about when it may make more sense to choose one or the other.

“As a patient, you’re trying to evaluate the physician, to see if you can talk to them and trust them,” said Dr. Russell Kohl, a family physician and board member of the American Academy of Family Physicians. “It’s hard to do that on a telemedicine visit.”

Maybe your insurance has changed and you need a new primary-care doctor or OB-GYN. Or perhaps you have a chronic condition and your doctor has suggested adding a specialist to the team. A face-to-face visit can help you feel comfortable and confident with their participation.

Sometimes an in-person first visit can help doctors evaluate their patients in nontangible ways, too. After a cancer diagnosis, for example, an oncologist might want to examine the site of a biopsy. But just as important, he might want to assess a patient’s emotional state.

“A diagnosis of cancer is an emotional event; it’s a life-changing moment, and a doctor wants to respond to that,” said Dr. Arif Kamal, an oncologist and the chief patient officer at the American Cancer Society. “There are things you can miss unless you’re sitting a foot or two away from the person.”

Once it’s clearer how the patient is coping and responding to treatment, that’s a good time to discuss incorporating telemedicine visits.

If a Physical Exam Seems Necessary

This may seem like a no-brainer, but there are nuances. Increasingly, monitoring equipment that people can keep at home — a blood-pressure cuff, a digital glucometer or stethoscope, a pulse oximeter to measure blood oxygen, or a Doppler monitor that checks a fetus’s heartbeat — may give doctors the information they need, reducing the number of in-person visits required.

Someone’s overall physical health may help tip the scales on whether an in-person exam is needed. A 25-year-old in generally good health is usually a better candidate for telehealth than a 75-year-old with multiple chronic conditions.

But some health complaints typically require an in-person examination, doctors said, such as abdominal pain, severe musculoskeletal pain, or problems related to the eyes and ears.

Abdominal pain could signal trouble with the gallbladder, liver, or appendix, among many other things.

“We wouldn’t know how to evaluate it without an exam,” said Dr. Ryan Mire, an internist who is president of the American College of Physicians.

Unless a doctor does a physical exam, too often children with ear infections receive prescriptions for antibiotics, said Mehrotra, pointing to a study he co-authored comparing prescribing differences between telemedicine visits, urgent care, and primary care visits.

In obstetrics, the pandemic accelerated a gradual shift to fewer in-person prenatal visits. Typically, pregnancy involves 14 in-person visits. Some models now recommend eight or fewer, said Dr. Nathaniel DeNicola, chair of telehealth for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. A study found no significant differences in rates of cesarean deliveries, preterm birth, birth weight, or admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit between women who received up to a dozen prenatal visits in person and those who received a mix of in-person and virtual visits.

Contraception is another area where less may be more, DeNicola said. Patients can discuss the pros and cons of different options virtually and may need to schedule a visit only if they want an IUD inserted.

If Something Is New, or Changes

When a new symptom crops up, patients should generally schedule an in-person visit. Even if the patient has a chronic condition such as diabetes or heart disease that is under control and care is managed by a familiar physician, sometimes things change. That usually calls for a face-to-face meeting too.

“I tell my patients, ‘If it’s new symptoms or a worsening of existing symptoms, that probably warrants an in-person visit,’” said Dr. David Cho, a cardiologist who chairs the American College of Cardiology’s Health Care Innovation Council. Changes could include chest pain, losing consciousness, shortness of breath, or swollen legs.

When patients are sitting in front of him in the exam room, Cho can listen to their hearts and lungs and do an EKG if someone has chest pain or palpitations. He’ll check their blood pressure, examine their feet to see if they’re retaining fluid, and look at their neck veins to see if they are bulging.

But all that may not be necessary for a patient with heart failure, for example, whose condition is stable, he said. They can check their own weight and blood pressure at home, and a periodic video visit to check in may suffice.

Video check-ins are effective for many people whose chronic conditions are under control, experts said.

When someone is undergoing treatment for cancer, certain pivotal moments will require a face-to-face meeting, said Kamal, of the American Cancer Society.

“The cancer has changed or the treatment has changed,” he said. “If they’re going to stop chemotherapy, they need to be there in person.”

And one clear recommendation holds for almost all situations: Even if a physician or office scheduler suggests a virtual visit, you don’t have to agree to it.

“As a consumer, you should do what you feel comfortable doing,” said Dr. Joe Kvedar, a professor at Harvard Medical School and immediate past board chairman of the American Telemedicine Association. “And if you really want to be seen in the office, you should make that case.”

Michelle Andrews is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Michelle Andrews: andrews.khn@gmail.com, @mandrews110

‘Inflexibly territorial’

1913 postcard of the way Downeast community.

Cutler, Maine, harbor.

“Many small towns I know in Maine are as tight-knit and interdependent as those I associate with rural communities in India or China; with deep roots and old loyalties, skeptical of authority, they are proud and inflexibly territorial.”

– Paul Theroux (born 1941), famed travel writer and novelist

Certain kinds of intensity

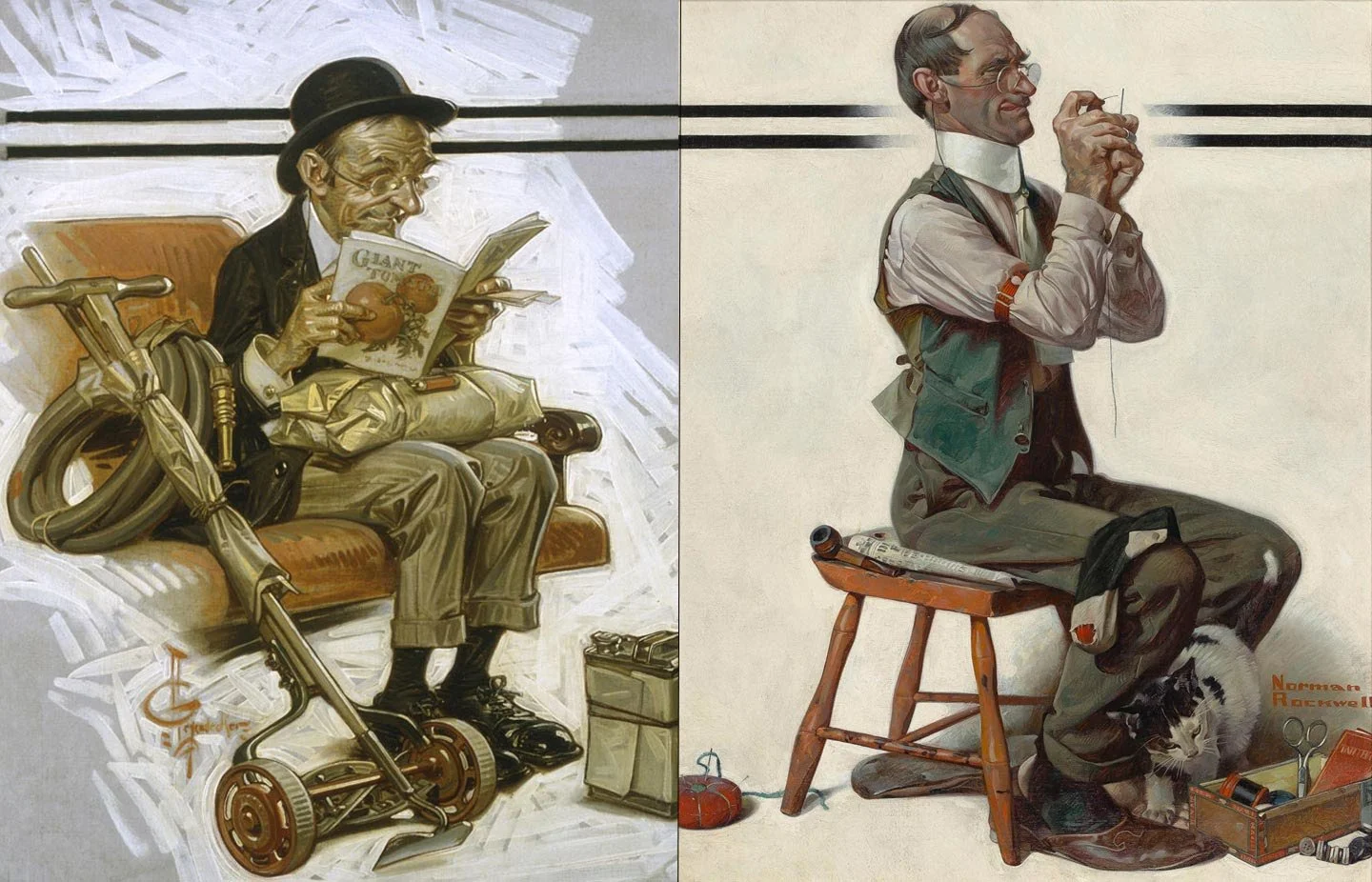

Left, “Spring Commuter’’ (oil on canvas), by J.C. Leyendecker (1870-1951), for the May 6, 1916 cover of The Saturday Evening Post. Right, “Threading the Needle” (oil on canvas), by Norman Rockwell, for the April 8, 1922 cover of the same magazine. Both at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, R.I.

The western facade of the mansion Vernon Court, at 492 Bellevue Ave., Newport R.I., home of the National Museum of American Illustration. It was built in 1900.

A pitch to create a microelectronics hub in New England

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

“A coalition of New England businesses and institutions have applied to the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) for funding under the recently passed CHIPS and Science Act to establish as Microelectronics Commons hub in the Northeast. The coalition is led by the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative and includes a number of other NEC member businesses and educational institutions.

“In November 2022, the Department of Defense launched its Microelectronics Commons program following the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act in August with the goal of linking U.S. R&D with manufacturing capacity. DOD plans to establish nine regional microelectronics-technology hubs across the nation and has $1.63 billion to invest.

“A main goal of this plan is to ‘bring ideas from the lab to the bench.’ If the coalition’s application for funding is accepted, the new hub in New England would link dozens of research, manufacturing and academic partners to grow a regional defense technology ecosystem, opening doors to major federal grants.

“Our region has an incredible depth of research, talent, and facilities across industry and academia needed to help the DoD deliver on the Microelectronics Commons vision,” said Doug Robbins, vice president, Engineering and Prototyping, at MITRE.

Those old cozy ski areas

— Photo by Stevage

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s sad to see the gradual disappearance of small, family-owned New England ski areas as they are taken over by such national chains as Vail Resorts or simply closed down for being money losers because of high energy and insurance costs and the aging of the population. The warmer winters don’t help either. I remember when it seemed that every member of an area’s owning family was working there – as ski instructors, lift operators, snack-bar officials and so on.

I have the fondest memories of March skiing, with the sun (relatively) warm and the corn snow easy to handle as you smelled the wood smoke from the base lodge wafting up the slopes in the moist air. And you could see spring in the bare earth around the base of trees by the slopes as they absorbed the sun’s rays.

— Photo by Grimmcar

We set up three bird feeders a few weeks ago, and no birds appeared for two weeks. Then a mob of the avians appeared all at once. Insider trading?]=

Of course the squirrels grow fat on bird food: They’re good Americans! But if your feeder is at the top of a pole, you can pour a little vegetable oil on it and watch these often obese and ingenious rodents struggle to climb up.

H.G. Wells: In Boston, 'an immense effect of finality'

Entrance to the Club of Odd Volumes, a social and literary club for bibliophiles. It’s on Mount Vernon Street, on Beacon Hill.

H.G. Wells visited it in 1906.

Commonwealth Avenue, in Boston’s Back Bay, in 1901

“The Boston Enchantment

“Yet even as I write of the universities as the central intellectual organ of a modern state, as I sit implying salvation by schools, there comes into my mind a mass of qualification. The devil in the American world drama may be mercantilism, ensnaring, tempting, battling against my hero, the creative mind of man, but mercantilism is not the only antagonist. In Fifth Avenue or Paterson one may find nothing but the zenith and nadir of the dollar hunt, at a Harvard table one may encounter nothing but living minds, but in Boston—I mean not only Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue, but that Boston of the mind and heart that pervades American refinement and goes about the world—one finds the human mind not base, nor brutal, nor stupid, nor ignorant, but mysteriously enchanting and ineffectual, so that having eyes it yet does not see, having powers it achieves nothing....

“I remember Boston as a quiet effect, as something a little withdrawn, as a place standing aside from the throbbing interchange of East and West. When I hear the word Boston now it is that quality returns. I do not think of the spreading parkways of Mr. Woodbury and Mr. Olmstead nor of the crowded harbor; the congested tenement-house regions, full of those aliens whose tongues struck so strangely on the ears of Mr. Henry James, come not to mind. But I think of rows of well-built, brown and ruddy homes, each with a certain sound architectural distinction, each with its two squares of neatly trimmed grass between itself and the broad, quiet street, and each with its family of cultured people within. I am reminded of deferential but unostentatious servants, and of being ushered into large, dignified entrance-halls. I think of spacious stairways, curtained archways, and rooms of agreeable, receptive persons. I recall the finished informality of the high tea. All the people of my impression have been taught to speak English with a quite admirable intonation; some of the men and most of the women are proficient in two or three languages; they have travelled in Italy, they have all the recognized classics of European literature in their minds, and apt quotations at command. And I think of the constant presence of treasured associations with the titanic and now mellowing literary reputations of Victorian times, with Emerson (who called Poe ‘that jingle man’), and with Longfellow, whose house is now sacred, its view towards the Charles River and the stadium—it is a real, correct stadium—secured by the purchase of the sward before it forever....

“At the mention of Boston I think, too, of autotypes and then of plaster casts. I do not think I shall ever see an autotype again without thinking of Boston. I think of autotypes of the supreme masterpieces of sculpture and painting, and particularly of the fluttering garments of the ‘Nike of Samothrace.’ (That I saw, also, in little casts and big, and photographed from every conceivable point of view.) It is incredible how many people in Boston have selected her for their aesthetic symbol and expression. Always that lady was in evidence about me, unobtrusively persistent, until at last her frozen stride pursued me into my dreams. That frozen stride became the visible spirit of Boston in my imagination, a sort of blind, headless, and unprogressive fine resolution that took no heed of any contemporary thing. Next to that I recall, as inseparably Bostonian, the dreaming grace of Botticelli's ‘Prima vera.’ All Bostonians admire Botticelli, and have a feeling for the roof of the Sistine chapel—to so casual and adventurous a person as myself, indeed, Boston presents a terrible, a terrifying unanimity of aesthetic discriminations. I was nearly brought back to my childhood's persuasion that, after all, there is a right and wrong in these things. And Boston clearly thought the less of Mr. Bernard Shaw when I told her he had induced me to buy a pianola, not that Boston ever did set much store by so contemporary a person as Mr. Bernard Shaw. The books she reads are toned and seasoned books—preferably in the old or else in limited editions, and by authors who may be lectured upon without decorum....

“Boston has in her symphony concerts the best music in America, and here her tastes are severely orthodox and classic. I heard Beethoven's Fifth Symphony extraordinarily well done, the familiar pinnacled Fifth Symphony, and now, whenever I grind that out upon the convenient mechanism beside my desk at home, mentally I shall be transferred to Boston again, shall hear its magnificent aggressive thumpings transfigured into exquisite orchestration, and sit again among that audience of pleased and pleasant ladies in chaste, high-necked, expensive dresses, and refined, attentive, appreciative, bald, or iron-gray men....

“II

“Boston's Antiquity

“Then Boston has historical associations that impressed me like iron-moulded, leather-bound, eighteenth-century books. The War of Independence, that to us in England seems half-way back to the days of Elizabeth, is a thing of yesterday in Boston. ‘Here,’ your host will say and pause, ‘came marching’ so-and-so, ‘with his troops to relieve’ so-and-so. And you will find he is the great-grandson of so-and-so, and still keeps that ancient colonial's sword. And these things happened before they dug the Hythe military canal, before Sandgate, except for a decrepit castle, existed; before the days when Bonaparte gathered his army at Boulogne—in the days of muskets and pigtails—and erected that column my telescope at home can reach for me on a clear day. All that is ancient history in England and in Boston the decade before those distant alarums and excursions is yesterday. A year or so ago they restored the British arms to the old State-House. ‘Feeling,’ my informant witnessed, ‘was dying down.’ But there were protests, nevertheless....

“If there is one note of incongruity in Boston, it is in the gilt dome of the Massachusetts State-House at night. They illuminate it with electric light. That shocked me as an anachronism. It shocked me—much as it would have shocked me to see one of the colonial portraits, or even one of the endless autotypes of the Belvidere Apollo replaced, let us say, by one of Mr. Alvin Coburn's wonderfully beautiful photographs of modern New York. That electric glitter breaks the spell; it is the admission of the present, of the twentieth century. It is just as if the Quirinal and Vatican took to an exchange of badinage with search-lights, or the King mounted an illuminated E.R. on the Round Tower at Windsor.

“Save for that one discord there broods over the real Boston an immense effect of finality. One feels in Boston, as one feels in no other part of the States, that the intellectual movement has ceased. Boston is now producing no literature except a little criticism. Contemporary Boston art is imitative art, its writers are correct and imitative writers the central figure of its literary world is that charming old lady of eighty-eight, Mrs. Julia Ward Howe. One meets her and Colonel Higginson in the midst of an authors' society that is not so much composed of minor stars as a chorus of indistinguishable culture. There are an admirable library and a museum in Boston, and the library is Italianate, and decorated within like an ancient missal. In the less ornamental spaces of this place there are books and readers. There is particularly a charming large room for children, full of pigmy chairs and tables, in which quite little tots sit reading. I regret now I did not ascertain precisely what they were reading, but I have no doubt it was classical matter.

“I do not know why the full sensing of what is ripe and good in the past should carry with it this quality of discriminating against the present and the future. The fact remains that it does so almost oppressively. I found myself by some accident of hospitality one evening in the company of a number of Boston gentlemen who constituted a book-collecting club. They had dined, and they were listening to a paper on Bibles printed in America. It was a scholarly, valuable, and exhaustive piece of research. The surviving copies of each edition were traced, and when some rare specimen was mentioned as the property of any member of the club there was decorously warm applause. I had been seeing Boston, drinking in the Boston atmosphere all day.... I know it will seem an ungracious and ungrateful thing to confess (yet the necessities of my picture of America compel me), but as I sat at the large and beautifully ordered table, with these fine, rich men about me, and listened to the steady progress of the reader's ever unrhetorical sentences, and the little bursts of approval, it came to me with a horrible quality of conviction that the mind of the world was dead, and that this was a distribution of souvenirs.

“Indeed, so strongly did this grip me that presently, upon some slight occasion, I excused myself and went out into the night. I wandered about Boston for some hours, trying to shake off this unfortunate idea. I felt that all the books had been written, all the pictures painted, all the thoughts said—or at least that nobody would ever believe this wasn't so. I felt it was dreadful nonsense to go on writing books. Nothing remained but to collect them in the richest, finest manner one could. Somewhere about midnight I came to a publisher's window, and stood in the dim moonlight peering enviously at piled copies of Izaak Walton and Omar Khayyam, and all the happy immortals who got in before the gates were shut. And then in the corner I discovered a thin, small book. For a time I could scarcely believe my eyes. I lit a match to be the surer. And it was A Modern Symposium, by Lowes Dickinson, beyond all disputing. It was strangely comforting to see it there—a leaf of olive from the world of thought I had imagined drowned forever.

“That was just one night's mood. I do not wish to accuse Boston of any wilful, deliberate repudiation of the present and the future. But I think that Boston—when I say Boston let the reader always understand I mean that intellectual and spiritual Boston that goes about the world, that traffics in book-shops in Rome and Piccadilly, that I have dined with and wrangled with in my friend W.'s house in Blackheath, dear W., who, I believe, has never seen America—I think, I say, that Boston commits the scholastic error and tries to remember too much, to treasure too much, and has refined and studied and collected herself into a state of hopeless intellectual and aesthetic repletion in consequence. In these matters there are limits. The finality of Boston is a quantitive consequence. The capacity of Boston, it would seem, was just sufficient but no more than sufficient, to comprehend the whole achievement of the human intellect up, let us say, to the year 1875 A.D. Then an equilibrium was established. At or about that year Boston filled up.

Late 19th Century print

“III

“About Wellesley

“It is the peculiarity of Boston's intellectual quality that she cannot unload again. She treasures Longfellow in quantity. She treasures his works, she treasures associations, she treasures his Cambridge home. Now, really, to be perfectly frank about him, Longfellow is not good enough for that amount of intellectual house room. He cumbers Boston. And when I went out to Wellesley {College} to see that delightful girls' college everybody told me I should be reminded of the ‘Princess.’ For the life of me I could not remember what ‘Princess.’ Much of my time in Boston was darkened by the constant strain of concealing the frightful gaps in my intellectual baggage, this absence of things I might reasonably be supposed, as a cultivated person, to have, but which, as a matter of fact, I'd either left behind, never possessed, or deliberately thrown away. I felt instinctively that Boston could never possibly understand the light travelling of a philosophical carpet-bagger. But I hid—in full view of the tree-set Wellesley lake, ay, with the skiffs of ‘sweet girl graduates’—own up. ‘I say,’ I said, ‘I wish you wouldn't all be so allusive. What Princess?’”

“It was, of course, that thing of Tennyson's. It is a long, frequently happy and elegant, and always meritorious narrative poem, in which a chaste Victorian amorousness struggles with the early formulae of the feminist movement. I had read it when I was a boy, I was delighted to be able to claim, and had honorably forgotten the incident. But in Boston they treat it as a living classic, and expect you to remember constantly and with appreciation this passage and that. I think that quite typical of the Bostonian weakness. It is the error of the clever high-school girl, it is the mistake of the scholastic mind all the world over, to learn too thoroughly and to carry too much. They want to know and remember Longfellow and Tennyson—just as in art they want to know and remember Raphael and all the elegant inanity of the sacrifice at Lystra, or the miraculous draught of Fishes; just as in history they keep all the picturesque legends of the War of Independence—looking up the dates and minor names, one imagines, ever and again. Some years ago I met two Boston ladies in Rome. Each day they sallied forth from our hotel to see and appreciate; each evening, after dinner, they revised and underlined in Baedeker what they had seen. They meant to miss nothing in Rome. It's fine in its way—this receptive eagerness, this learners' avidity. Only people who can go about in this spirit need, if their minds are to remain mobile, not so much heads as cephalic pantechnicon vans....

“IV

“The Wellesley Cabinets

“I find this appetite to have all the mellow and refined and beautiful things in life to the exclusion of all thought for the present and the future even in the sweet, free air of Wellesley's broad park, that most delightful, that almost incredible girls' university, with its class-rooms, its halls of residence, its club-houses and gathering-places among the glades and trees. I have very vivid in my mind a sunlit room in which girls were copying the detail in the photographs of masterpieces, and all around this room were cabinets of drawers, and in each drawer photographs. There must be in that room photographs of every picture of the slightest importance in Italy, and detailed studies of many. I suppose, too, there are photographs of all the sculpture and buildings in Italy that are by any standard considerable. There is, indeed, a great civilization, stretching over centuries and embodying the thought and devotion, the scepticism and levities, the ambition, the pretensions, the passions, and desires of innumerable sinful and world-used men—canned, as it were, in this one room, and freed from any deleterious ingredients. The young ladies, under the direction of competent instructors, go through it, no doubt, industriously, and emerge—capable of Browning.

“I was taken into two or three charming club-houses that dot this beautiful domain. There was a Shakespeare club-house, with a delightful theatre, Elizabethan in style, and all set about with Shakespearean things; there was the club-house of the girls who are fitting themselves for their share in the great American problem by the study of Greek. Groups of pleasant girls in each, grave with the fine gravity of youth, entertained the reluctantly critical visitor, and were unmistakably delighted and relaxed when one made it clear that one was not in the Great Teacher line of business, when one confided that one was there on false pretences, and insisting on seeing the pantry. They have jolly little pantries, and they make excellent tea.

“I returned to Boston at last in a state of mighty doubting, provided with a Wellesley College calendar to study at my leisure.

“I cannot, for the life of me, determine how far Wellesley is an aspect of what I have called Boston; how far it is a part of that wide forward movement of the universities upon which I lavish hope and blessings. Those drawings of photographed Madonnas and Holy Families and Annunciations, the sustained study of Greek, the class in the French drama of the seventeenth century, the study of the topography of Rome fill me with misgivings, seeing the world is in torment for the want of living thought about its present affairs. But, on the other hand, there are courses upon socialism—though the text-book is still Das Kapital of Marx—and upon the industrial history of England and America. I didn't discover a debating society, but there is a large accessible library.

“How far, I wonder still, are these girls thinking and feeding mentally for themselves? What do they discuss one with another? How far do they suffer under that plight of feminine education—notetaking from lectures?...

“But, after all, this about Wellesley is a digression into which I fell by way of Boston's autotypes. My main thesis was that culture, as it is conceived in Boston, is no contribution to the future of America, that cultivated people may be, in effect, as state-blind as—Mr. Morgan Richards. It matters little in the mind of the world whether any one is concentrated upon medieval poetry, Florentine pictures, or the propagation of pills. The common, significant fact in all these cases is this, a blindness to the crude splendor of the possibilities of America now, to the tragic greatness of the unheeded issues that blunder towards solution. Frankly, I grieve over Boston—Boston throughout the world—as a great waste of leisure and energy, as a frittering away of moral and intellectual possibilities. We give too much to the past. New York is not simply more interesting than Rome, but more significant, more stimulating, and far more beautiful, and the idea that to be concerned about the latter in preference to the former is a mark of a finer mental quality is one of the most mischievous and foolish ideas that ever invaded the mind of man. We are obsessed by the scholastic prestige of mere knowledge and genteel remoteness. Over against unthinking ignorance is scholarly refinement, the spirit of Boston; between that Scylla and this Charybdis the creative mind of man steers its precarious way.’’

— From The Future in America (1906) by H.G. Wells (1866-1946), prolific English author

David Warsh: Will geoengineering be needed to stem global warming?

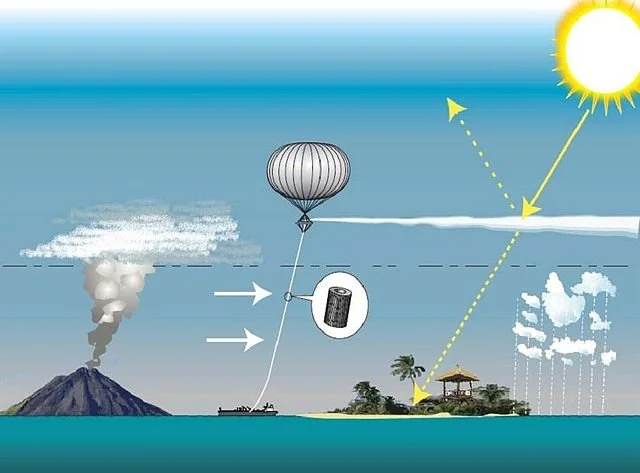

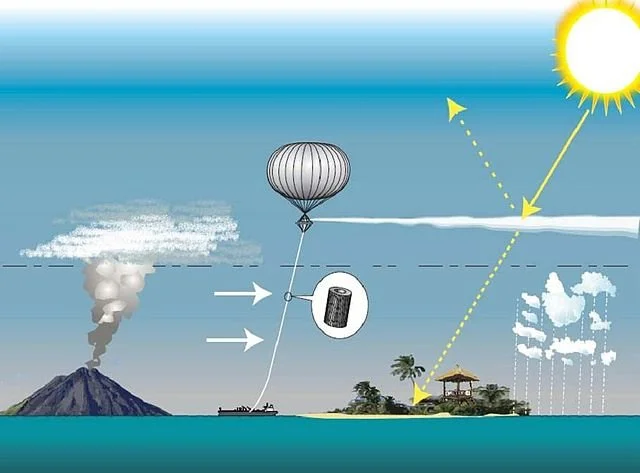

Proposed solar geoengineering using a tethered balloon to inject sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Of the three broad approaches to coping with the effects of global warming – reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions; various adaptations to a warmer world, and solar-radiation management – it is the idea of climate intervention, or “geoengineering,” as its enthusiasts often describe it, that engenders the most fear.

We know that the natural version works: Volcanic eruptions over the millennia have demonstrated that much. Volcanic dust spewed into high altitudes has reduced temperature over significant portions of the Earth’s surface in the past, by making the atmosphere more reflective of the sun’s rays.

But the idea of deliberately pumping sulfates into the stratosphere to reduce global temperatures appears to some so risky, if only by dint of the “not-to-worry” incentive it seems to imply, that some climate scientists – their opinions buttressed by Under a White Sky, the book and Snowpiercer, the film – have called for a ban any geoengineering research at all.

That would clearly be foolish. The good news is that Science magazine last month reported that the first cautious attempts to understand the Earth’s “radiation budget” have begun. Prodded by Congress, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has launched a program to understand “the types, amounts and behavior of particles naturally present in the stratosphere.” SilverLining, an interesting non-governmental lobbying organization, is also involved.

[T]the balloons and high-altitude aircraft in the program aren’t releasing any particles or gases. But the large-scalefield campaign is the first the U.S. government has ever conducted related to solar geoengineering. It’s very basic research, says Karen Rosenlof, an atmospheric scientist at NOAA’s Chemical Sciences Laboratory. “You have to know what’s there first before you can start messing with that.”

An appropriately cautious beginning. I don’t know how humankind will gradually solve the climate-change problem, but I am pretty confident that it will, through some combination of alternative fuels; massive adaptations, both physical and social; and, probably, some degree of geoengineering. I am reminded of the Christian hymn text that William Cowper wrote , in 1773, so apropos today that it is worth quoting at some length. A great deal has happened in those 250 years, of course, so feel free to substitute “Evolution” for “God,” if you prefer. It still scans.

God moves in a mysterious way,

His wonders to perform;

He plants his footsteps in the sea,

And rides upon the storm.

Deep in unfathomable mines

Of never failing skill;

He treasures up his bright designs,

And works His sovereign will.

Ye fearful saints fresh courage take,

The clouds ye so much dread

Are big with mercy, and shall break

In blessings on your head.

Judge not the Lord by feeble sense,

But trust him for his grace;

Behind a frowning providence,

He hides a smiling face….

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Rugged terrain

“Mountain Time,’’ by Wilson Hunt, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass. He lives in Boston’s Roslindale neighborhood.

At Roslindale Square directly across the street from the Roslindale Village Commuter Rail stop. It looks like London.

— Photo by RHKindred -