Vox clamantis in deserto

Birchbark building

“Back of State and Main” (in Montpelier Vt.) (inkjet on birchbark), by Burlington, Vt.-based photographer Richard Moore, at The Front gallery, Montpelier, Vt., though Jan. 29.

Main Street in downtown Montpelier.

— Photo by GearedBull

Montpelier in 1884. Note the state capitol. The Winooski River enjoys flooding the city from time to time.

David Warsh: Defense of and attack on government debt

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weary of reading play-by-play stories about the Treasury Department’s efforts to manage in light of the hold-up by right-wing Republicans over reaching the federal debt ceiling – impoundment decisions, discharge petitions and various accounting maneuvers – I took down my copy of Barry Eichengreen’s In Defense of Public Debt (Oxford, 2021) to remind me of what, at bottom, the fracas is all about.

Eichengreen, an economic historian at the University of California at Berkeley, is still not yet a household word in homes where economics is dinner-table conversation, though earlier this month he was named (with four others) a distinguished fellow of the American Economic Association, the profession’s highest honor.

He was recognized chiefly for having written Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression 1919-1939 (Oxford, 1992), which has become the standard account of how the Great Depression was so globally damaging – the role that the gold standard played in transmitting around the world its origins in the United States.

But it was sheer good citizenship that led Eichengreen and three other experts – Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves and Kris James Mitchener – to write what their publisher describes as “a dive into the origins, management, and uses and misuses of sovereign debt through the ages.” Their Defense turns out. too, to be useful in looking ahead to what is said to be a looming crisis of global debt. .

Their book begins with another dramatic moment of American civic life: Sen, Rand Paul (R.-Ky.) inveighing in December 2020, against government borrowing earlier that year on news of the outbreak of the global Covid pandemic:

How bad is our fiscal situation? Well, the federal government brought in $3.3 trillion in revenue last year and spent $6.6 trillion, for a record-setting $3.3 trillion deficit. If you are looking for more Covid bailout money, we don’t have any. The coffers are bare. We have no rainy day fund. We have no savings account. Congress has spent all of the money.

Paul’s alarm was based on a fundamental insight, Eichengreen and his co-authors write, namely that governments are responsible for their nations’ finances. If they borrow frivolously, or excessively, bad consequences usually follow, On the other hand, if national governments fail to borrow in a genuine emergency – to fight a war deemed necessary; to staunch a financial panic; to facilitate a domestic political pivot – even worse damages might ensue. The sword is two-sided: Public debt has its legitimate uses, after all. .

A market for sovereign debt has existed for millennia. Kings and war-lords borrowed, most often to wage war. They paid exorbitant interest rates because they often defaulted. It was only in the 17th Century, as modern nations began to emerge, that viable institutions of public debt were established, first in England and the Netherlands.

Constitutional governments, with legislatures and parliaments, made it possible for would-be lenders to participate in decisions to borrow, to engineer realistic hopes of getting their money back, as they turned in the coupons they clipped from their government bonds in exchange for semi-annual payments of interest. Advice and consent became part of the game.

From the beginning, there was ambivalence. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith himself warned that it would be all to easy for nations to borrow profligately against the promise of future tax revenues, Eichengreen noted. Smith made an exception mainly for war. As it turned out, the stabilization of British government debt markets organized by Robert Walpole after the disastrous South Sea Bubble, which popped in 1720, became the original military industrial complex. Many scholars credit superior borrowing capacity for Britain’s eventual victory in the Napoleonic Wars.

Government borrowing expanded to other purposes in the 19th Century, Eichengreen writes, especially for investments in canals and railroads intended to foster geographic integration and growth. Central banks learned how to halt financial panics by serving as lenders of last resort.

In the 20th Century, he says, the emphasis shifted again, this time to social services and transfer payments. Government borrowing financed the creation of the modern welfare state. And, of course, governments continue to shoulder the responsibility to maintain overall financial stability.

Today, the argument is between “conservative” radicals who hope to disassemble the welfare state, and radical “progressives,” who seek to expand it with little concern for the dangers of borrowing too much. In the center are a large corps of sensible citizens, such as Eichengreen, who seek to harness the existing system of taxing and borrowing and spending to let it work in a sensible and less expensive manner.

The market for government debt has survived, Eichengreen notes, “indeed thrived, for the better part of five hundred years.” It is an indispensable part of the world’s fiscal plumbing. Tinkering with it is fine; holding it hostage makes no sense at all. In Defense of Public Debt is an excellent primer on all these issues. I haven’t done it justice, but I started too late, and have run out of time.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Liability Lane

A noncollapsed part of Newport’s Cliff Walk.

— Photo by Giorgio Galeotti

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Will they soon have to patch and fill along and on Newport’s famous Cliff Walk every few months, what with rising seas and more intense storms? The latest drama came in a Dec. 23 tempest in which part of the walk’s embankment collapsed. A section of the walk itself collapsed last March in a storm.

Maybe they should change the name of this tourist attraction to Liability Lane.

But the big thing to watch in The City by the Sea is the redevelopment and, we hope, beautification, of the ugly North End.

Speaking of the tourist mecca of Newport, the country, including New England, will likely go into a recession this year, and unlike in the pandemic recession, the Feds can’t be expected to bail out the states. So the states better pump up their rainy-day funds. Rhode Island, for its part, should intensify its promotion of warm-weather tourism, especially in such nearby areas as Greater New York City, to get more sales tax revenue to help offset the decline in other tax revenue.

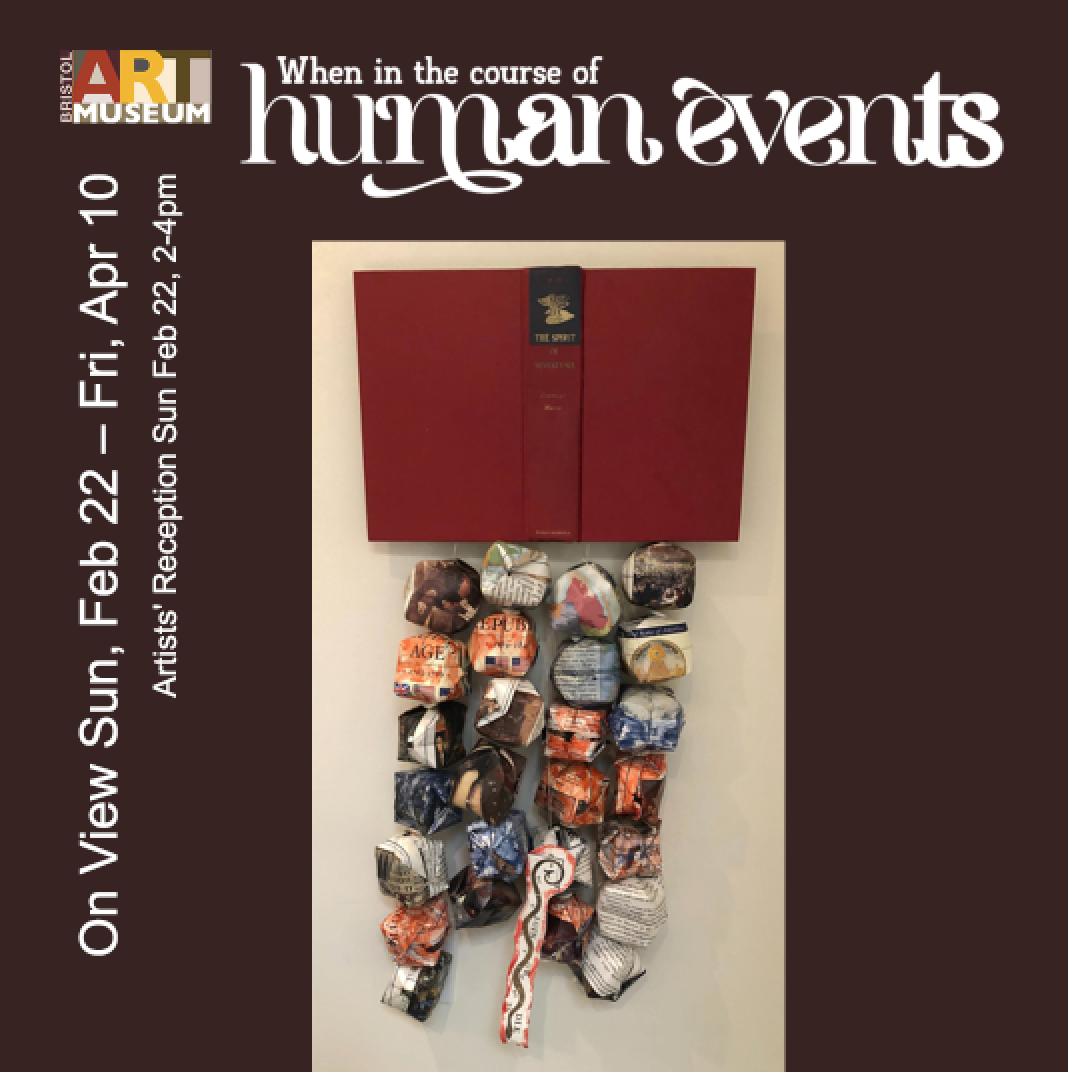

New England's icier past

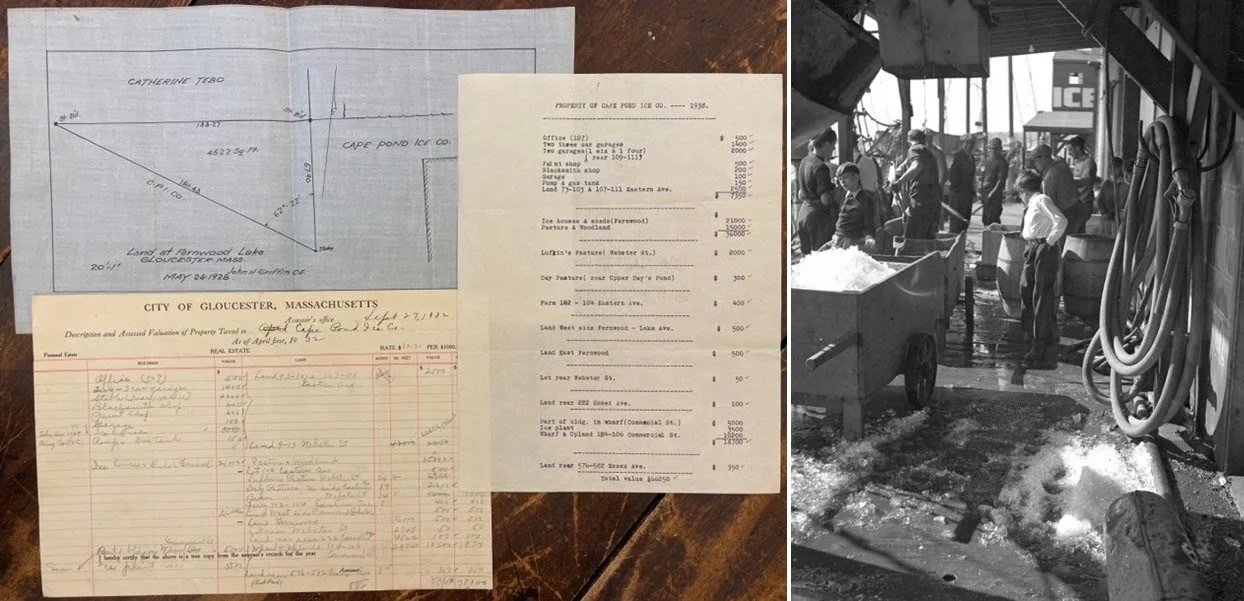

At the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.: Left, items from the Cape Pond Ice Company Collection, including blueprints and listings of assets. Right, Cape Pond Ice Wharf, circa 1930s.

—Photo by Henry Williams

Winters were colder and longer in southern New England not that long ago, historically speaking. Ice was a major “crop,’’ with much of it shipped in sawdust to warmer climes, and many harbors froze up most winters, sometimes for weeks.

Will hold us to spring

“Super Bloom (clay, glaze), by Kathy Butterly, in her show “Out of One, Many/Headscapes,’’ at the Portland (Maine) Museum of Art.

©Kathy Butterly. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photo: Alan Wiener.

The museum says that the show is an exhibition of small ceramic works. “These delicate, small-scale pieces …belie their size in meaning and complexity. This exhibit pulls together art from two bodies of work — ‘Out of One, Many,’ which ‘showcases the anthropomorphic, playful, intricate and provocative side of Butterly, and ‘Headscapes,’ which displays 10 pieces made specifically for this show.’’

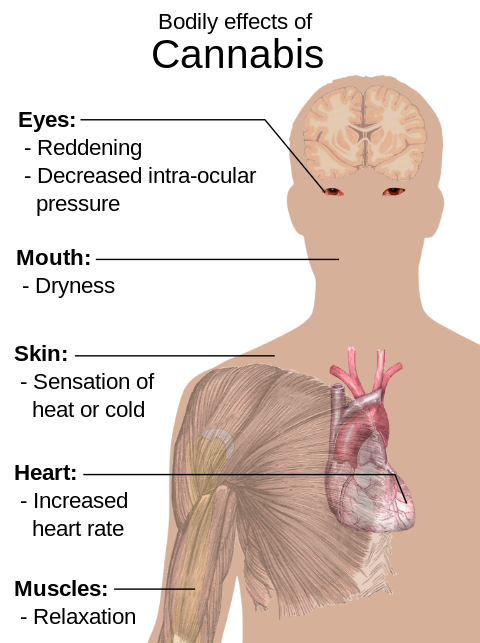

Chris Powell: Marijuana not really legal; highway fantasy

Anti-marijuana warning from 1935.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

News organizations and state government proclaimed last week that marijuana is now legal in Connecticut. But it's not really.

Pressed about the issue, the U.S. attorney's office for Connecticut quickly confirmed that while Connecticut and other states have repealed their criminal laws on marijuana, possession and sale of the drug remain violations of federal law. The marijuana business is going into the open in many states only because for some years now the federal government, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, has decided not to enforce the federal law.

As U.S. Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland has told Congress: "I do not think it the best use of the Justice Department's limited resources to pursue prosecutions of those who are complying with the laws in states that have legalized and are effectively regulating marijuana."

Of course there is always much discretion in law enforcement, like the patrol officer who issues an oral warning instead of a ticket to a speeding motorist.

But discretion in a particular case is nothing compared to a decision to suspend entirely the enforcement of a law. There is no authority for that, since the U.S. Constitution requires that the president, the head of the federal executive department, "shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed." The Constitution does not say that the president shall choose which laws to enforce.

That is totalitarianism -- the end of law.

Attorney General Garland's rationale for not enforcing federal marijuana law in states that are facilitating the marijuana business -- the Justice Department's "limited resources" -- is even weaker.

For to close the state-sanctioned marijuana business, the department would need only to make an arrest at a single marijuana retailer in each state that is sanctioning the business. The industry would fold up within hours. Indeed, it would not have sprung up at all without confidence in federal indifference.

This doesn't mean that marijuana should remain criminalized. While it can be addictive and cause harm, it is mild as illegal drugs go and can have medical uses. Decades of criminalization probably have caused more problems than they have prevented. The bigger problem now is respect for law.

States should be simply repealing their criminal laws on marijuana, leaving enforcement to the federal government. States should not be facilitating sale of the drug, which is essentially nullification of federal law -- just what Connecticut and some other states have been doing with illegal immigration, obstructing federal immigration agents and giving state identification documents to illegal immigrants to facilitate their lawbreaking.

Meanwhile Congress should take marijuana out of federal criminal law and strengthen pursuit of more dangerous drugs, especially fentanyl.

The present circumstances with marijuana -- legal and illegal at the same time in the same place -- invite contempt for law and government.

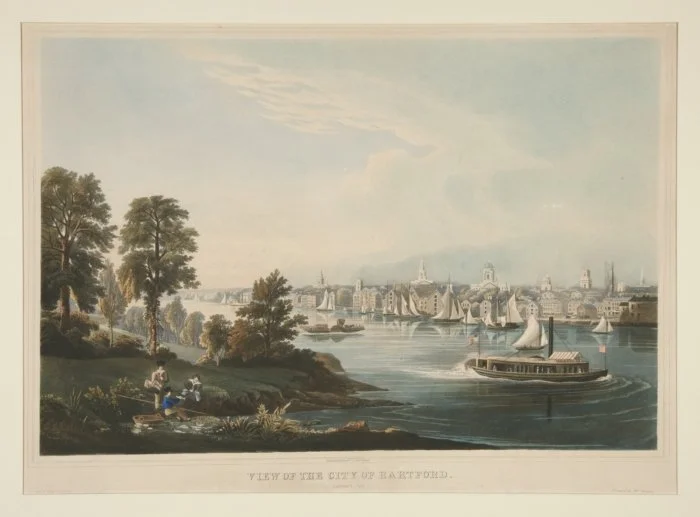

The Connecticut River and Hartford in the early 19th Century.

I-84 and the Bulkeley Bridge in Hartford.

— Photo by Pepper

According to the Connecticut Mirror, the idea of U.S. Rep. John B. Larson, (D-1st District) to relocate the Hartford area's highways and put miles of them in tunnels at the cost of maybe $17 billion and decades of construction work is starting to be taken seriously by state transportation officials.

It shouldn't be. For while it might be nice for the Hartford bank of the Connecticut River to be covered with parks and condominiums instead of highways, getting around the Hartford area is easy enough and is getting easier as rush-hour commuting for office work is replaced by telecommuting.

Meanwhile Connecticut's public health system has big gaps; its cities remain sunk in generational poverty; its electricity, railroad and sanitation systems are creaky; its schools are failing; and its government employee retirement system is underfunded -- all amid high inflation caused by too much government spending.

None of those things will be visible from an interstate highway tunnel but they will still be there. First things first.

Chris Powell (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com) is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

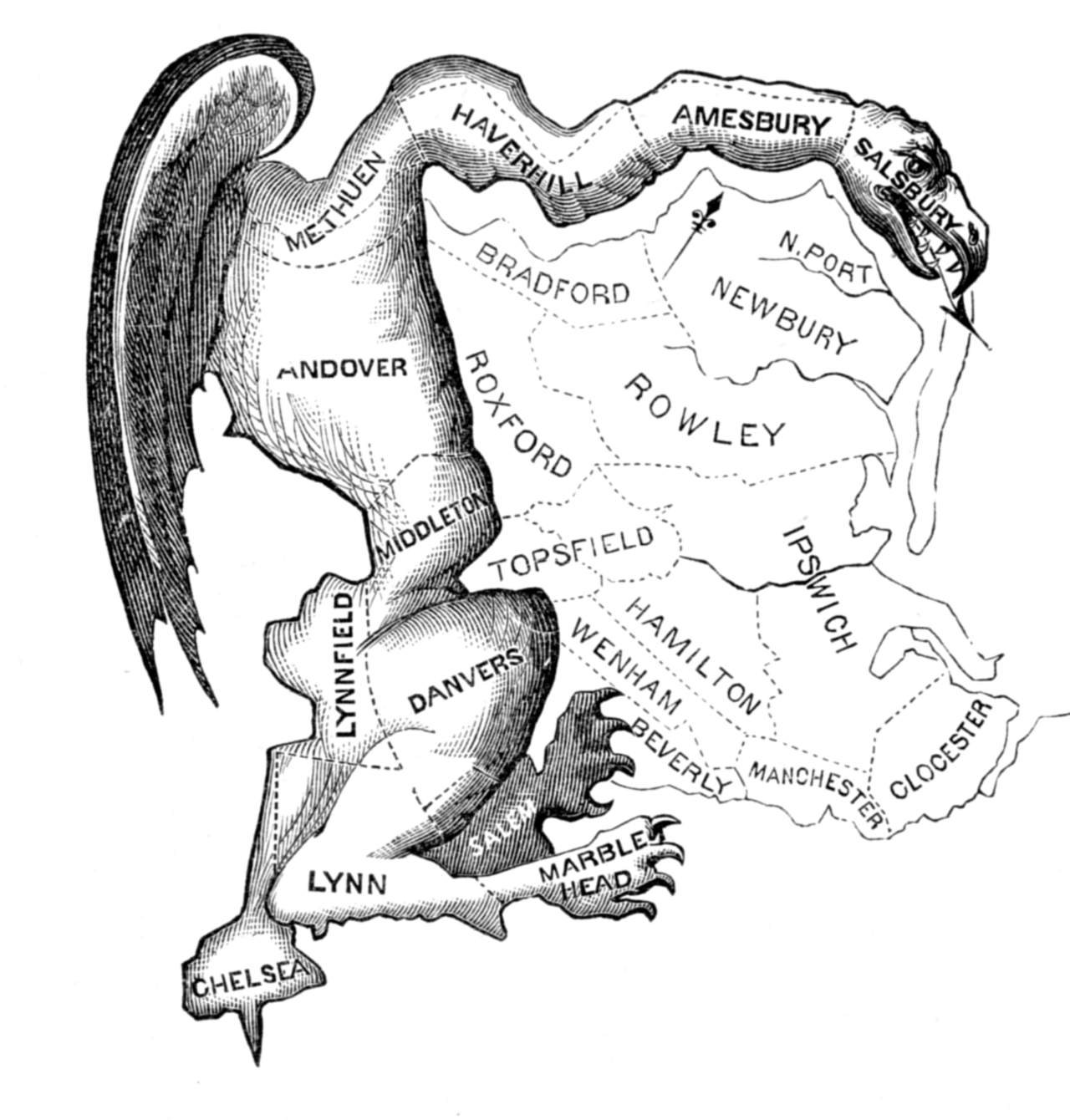

Boston’s best known aid to hallucination

Painting by J.S. Dykes, shown in exhibition of his paintings and prints in his Boston gallery through Feb. 17.

Judith Graham: What elderly people should know about taking Paxlovid for COVID

Paxlovid blister pack

— Photo by Kches16414

“There’s lots of evidence that Paxlovid can reduce the risk of catastrophic events that can follow infection with COVID in older individuals.’’

— Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a professor of medicine at Yale University

A new coronavirus variant is circulating, the most transmissible one yet. Hospitalizations of infected patients are rising. And older adults represent nearly 90% of U.S. deaths from COVID-19 in recent months, the largest portion since the start of the pandemic.

What does that mean for people 65 and older catching COVID for the first time or those experiencing a repeat infection?

The message from infectious-disease experts and geriatricians is clear: Seek treatment with antiviral therapy, which remains effective against new COVID variants.

The therapy of first choice, experts said, is Paxlovid, an antiviral treatment for people with mild to moderate COVID at high risk of becoming seriously ill from the virus. All adults 65 and up fall in that category. If people can’t tolerate the medication — potential complications with other drugs need to be carefully evaluated by a medical provider — two alternatives are available.

“There’s lots of evidence that Paxlovid can reduce the risk of catastrophic events that can follow infection with COVID in older individuals,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a professor of medicine at Yale University.

Meanwhile, develop a plan for what you’ll do if you get the disease. Where will you seek care? What if you can’t get in quickly to see your doctor, a common problem? You need to act fast since Paxlovid must be started no later than five days after the onset of symptoms. Will you need to adjust your medication regimen to guard against potentially dangerous drug interactions?

“The time to be figuring all this out is before you get COVID,” said Dr. Allison Weinmann, an infectious-disease expert at Henry Ford Hospital, in Detroit.

Being prepared proved essential when I caught COVID in mid-December and went to urgent care for a prescription. Because I’m 67, with blood cancer and autoimmune illness, I’m at elevated risk of getting severely ill from the virus. But I take a blood thinner that can have life-threatening interactions with Paxlovid.

Fortunately, the urgent-care center could see my electronic medical record, and a physician’s note there said it was safe for me to stop the blood thinner and get the treatment. (I’d consulted with my oncologist in advance.) So, I walked away with a Paxlovid prescription, and within a day my headaches and chills had disappeared.

Just before getting COVID, I’d read an important study of nearly 45,000 patients 50 and older treated for the disease between January and July 2022 at Mass General Brigham, the large Massachusetts health system. Twenty-eight percent of the patients were prescribed Paxlovid, which had received an emergency use authorization for mild to moderate covid from the FDA in December 2021; 72% were not. All were outpatients.

Unlike in other studies, most of the patients in this one had been vaccinated. Still, Paxlovid conferred a notable advantage: Those who took it were 44% less likely to be hospitalized with severe COVID-related illnesses or die. Among those who’d gotten fewer than three vaccine doses, those risks were reduced by 81%.

A few months earlier, a study out of Israel had confirmed the efficacy of Paxlovid — the brand name for a combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir — in seniors infected with COVID’s omicron strain, which arose in late 2021. (The original study establishing Paxlovid’s effectiveness had been conducted while the delta strain was prevalent and included only unvaccinated patients.) In patients 65 and older, most of whom had been vaccinated or previously had covid, hospitalizations were reduced by 73% and deaths by 79%.

Still, several factors have obstructed Paxlovid’s use among older adults, including doctors’ concerns about drug interactions and patients’ concerns about possible “rebound” infections and side effects.

Dr. Christina Mangurian, vice dean for faculty and academic affairs at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine, encountered several of these issues when both her parents caught covid in July, an episode she chronicled in a recent JAMA article.

First, her father, 84, was told in a virtual medical appointment by a doctor he didn’t know that he couldn’t take Paxlovid because he’s on a blood thinner — a decision later reversed by his primary care physician. Then, her mother, 78, was told, in a separate virtual appointment, to take an antibiotic, steroids, and over-the-counter medications instead of Paxlovid. Once again, her primary care doctor intervened and offered a prescription.

In both cases, Mangurian said, the doctors her parents first saw appeared to misunderstand who should get Paxlovid, and under what conditions. “This points to a major deficit in terms of how information about this therapy is being disseminated to front-line medical providers,” she told me in a phone conversation.

Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, agrees. “Every day, I hear from people who are misinformed by their physicians or call-in nurse lines. Generally, they’re being told you can’t get Paxlovid until you’re seriously ill — which is just the opposite of what’s recommended. Why are we not doing more to educate the medical community?”

The potential for drug interactions with Paxlovid is a significant concern, especially in older patients with multiple medical conditions. More than 120 medications have been flagged for interactions, and each case needs to be evaluated, taking into account an individual’s conditions, as well as kidney and liver function.

The good news, experts say, is that most potential interactions can be managed, either by temporarily stopping a medication while taking Paxlovid or reducing the dose.

“It takes a little extra work, but there are resources and systems in place that can help practitioners figure out what they should do,” said Brian Isetts, a professor at the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy.

In nursing homes, patients and families should ask to speak to consultant pharmacists if they’re told antiviral therapy isn’t recommended, Isetts suggested.

About 10% of patients can’t take Paxlovid because of potential drug interactions, according to Dr. Scott Dryden-Peterson, medical director of COVID outpatient therapy for Mass General Brigham. For them, Veklury (remdesivir), an antiviral infusion therapy delivered on three consecutive days, is a good option, although sometimes difficult to arrange. Also, Lagevrio (molnupiravir), another antiviral pill, can help shorten the duration of symptoms.

Many older adults fear that after taking Paxlovid they’ll get a rebound infection — a sudden resurgence of symptoms after the virus seems to have run its course. But in the vast majority of cases “rebound is very mild and symptoms — usually runny nose, nasal congestion, and sore throat — go away in a few days,” said Dr. Rajesh Gandhi, an infectious-disease physician and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Gandhi and other physicians I spoke with said the risk of not treating COVID in older adults is far greater than the risk of rebound illness.

Side effects from Paxlovid can include a metallic taste in the mouth, diarrhea, nausea and muscle aches, among others, but serious complications are uncommon. “Consistently, people are tolerating the drug really well,” said Dr. Caroline Harada, associate professor of geriatrics at the University of Alabama-Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine, “and feeling better very quickly.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

The enemy in your mirror

“We have met the enemy, and he is us.’’

— “Pogo”

A line from one of cartoonist Walt Kelly’s (1913-1973) “Pogo” comic strips, modified from Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s remark in the War of 1812, “We have met the enemy {the British} and they are ours,” after the American victory in Battle of Lake Erie, on Sept. 10, 1813. Perry was a Rhode Islander.

Walt Kelly, who grew up in Bridgeport, Conn., was marking the Earth Day, in 1971, with the message that man – because of his treatment of the Earth – is its enemy.

xxx

But in another Pogo chapter the character Porkypine says:

“Don’t take life so serious, son….it ain’t no how permanent.’’

The huge Deer Island sewage-treatment plant in Boston Harbor, created as a result of the environmental movement that started in the 60’s. It became fully operation in 2000. Boston Harbor had been notoriously polluted since the mid-19th Century.

— Photo by Doc Searls

‘From the furnace of a star’

Saint Joseph's Abbey, in Spencer Mass., a Trappist monastery.

— Photo by John Phelan

“The monastery is quiet. Seconal

drifts down upon it from the moon.

I can see the lights

of the city I came from,

can remember how a boy sets out

like something thrown from the furnace

of a star…. ‘‘

— From “The Monk’s Insomnia,’’ by Denis Johnson (1949-2017), an American poet. This came from the book Mountain Interval: Poems from the Frost Place, 1977-1986. The Frost Place, in Franconia, N.H., is a museum and poetry center dedicated to Robert Frost, who lived there with his family full time from 1915 to 1920, as he was becoming famous, and then summered there until 1940.

— Photo by Mfwills

‘Celebration and suspicion’

"Star Trail Dancer," by Scot J. Wittman, in his show, “Justice,’’ at Nesto Gallery at Milton Academy, Milton, Mass., through Feb. 11.

The gallery says that the multi-faceted exhibition seeks to achieve Wittman's goal, in his words, of "[shining] light on shifting human capability and its global impact," with "equal parts celebration and suspicion."

‘‘Justice’’ uses photography, digital artwork, NFTs, drawing, sculpture and painting to create a varied but deep exhibition.

The Suffolk Resolves House, in Milton, where American colonists tried to establish negotiations with the British Empire in 1774 to avert war. It was one of the meetings that laid the groundwork for the Declaration of Independence.

— Photo by Daderot

David Warsh: Deconstructing Hayek; does market get technology’s direction right?

John Singer Sargent's iconic World War I painting “Gassed”, showing blind casualties on a battlefield after a mustard gas attack. The same chemists’ work had resulted in creating highly useful fertilizers — and poison gas and very powerful explosives.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I was looking forward to the session on Hayek at the economic meetings in New Orleans last week. As a soldier of the revolution, I had learned a good deal from Hayek back in the day, when his occasional pieces sometimes appeared in Encounter magazine. (I knew Hayek had been the prime mover behind the founding of the classically liberal pro-markets Mont Pelerin Society in 1947; knew, too, that Encounter has been partly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency, in 1953, in an effort to counter Cold War ambivalence.

I understood that Hayek was one of a handful of economists who had been especially influential before John Maynard Keynes swept the table in the Thirties. Others included Irving Fisher, Joseph Schumpeter, A.C. Pigou, Edward Chamberlin, and Wesley Clair Mitchell. What revolution? We journalists were hoping to glimpse economics whole. The economists whom we read (and other social scientists, historians, and philosophers) seemed as blind men handling an elephant. Each described some part of the truth.

The session devoted to Bruce Caldwell’s new biography, Hayek: A Life: 1899-1950 (Chicago, 2022), didn’t disappoint. Presiding was Sandra Peart, of the University of Richmond, an expert on the still-born Virginia school of political economy of the Fifties (as opposed to the Chicago school of economics), with which Hayek was sometimes connected. Cass Sunstein, of the Harvard Law School; Hansjörg Klausinger, of Vienna University of Economics and Business; and Vernon Smith, of Chapman University, zoomed in. Steven N. Durlauf, of the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy (and editor if the Journal of Economic Literature); Emily Skarbek, of Brown University, were present discussants; as was, of course, Caldwell himself. The reader-friendly Hayek: A Life was itself the star of the show: a gracefully documented and thoroughly knowledgeable story of Vienna, New York, Berlin, London and Chicago, during those luminous years. I look forward to the second volume, 1950-1992.

Then I walked half a mile down New Orleans’ Canal Street to hear the American Economic Association Distinguished Lecture by Daron Acemoglu, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This was a very different world from that of Hayek.

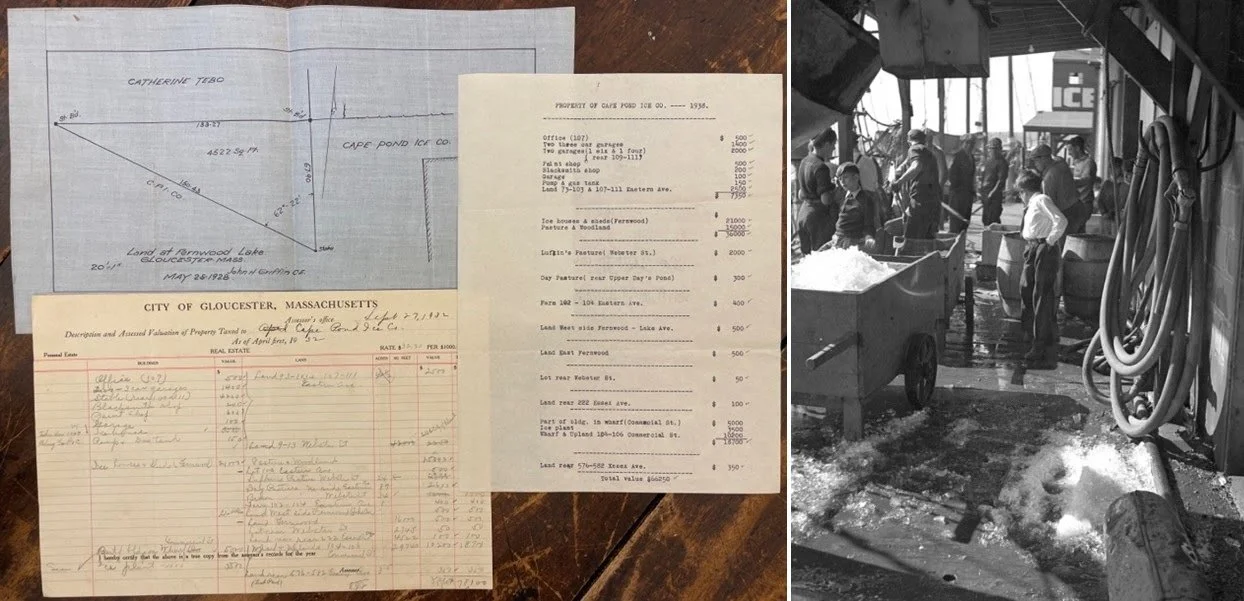

For one thing, “Distorted Innovation: Does the Market Get the Direction of Technology Right?” wasn’t really a lecture at all. It was a technical paper, presenting a simple mode of directed technology, with which Acemoglu has been working for twenty-five years, followed by discussions of several examples of what Acemoglu described as instances in which technologies have become distorted by shifting incentives: energy, health and medical markets; agriculture; and modern automation technologies. The paper begins in jaunty fashion,

There is broad agreement that technical change has been a major engine of economic growth and prosperity during the last 250 years, However not all innovations are created equal and the direction of technology matters greatly as well.

What constitutes the “direction of technical change?” Acemoglu offered a striking example. Early 20th-century chemists in Germany, led by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, developed an industrial process for converting atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Synthetic fertilizers thereby rendered commercial, greatly improved agricultural yields around the world. But the same processes were employed in industrial production of potent explosives and poisonous gases which killed millions of soldiers and civilians during World War I. Which direction might an effective social planner have preferred?

One view, the one for which Hayek is famous, is that the market is the best judge of which technologies to develop. There may be insufficient incentives to innovate initially, but once the government provides the requisite research infrastructure and support, it should stand aside. What the market thinks right, meaning profitable, is right, in this view.

Diametrically opposite, Acemoglu said, is the view that the politicians, planners and bureaucrats can decide on these matters as well as or even better than markets, and therefore they should set both the overall level of innovation and seek to influence its direction. This is welfare economics, a style of economic analysis pioneered after 1911 by A.C. Pigou, then the professor of economics at Cambridge University, and, for twenty-five years, perhaps the most influential economist in the world.

In his paper Acemoglu sought to describe an intermediate position, in which markets exist to experiment in order to determine which innovations are feasible, whereupon planners have a role in applying economic analysis to gauge otherwise unexamined side-effects of various sorts that may arise from a pursuing a particular path.

It was an unusual lecture, pitched to the level of a graduate seminar, and even before Acemoglu finished, individuals began drifting off to dinner engagements. The good news is that there is a book on its way. Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (Public Affairs),by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson will appear in May. Still better news is that it tackles head-on questions about automation, artificial intelligence, and income distribution that currently abound.

With three big books behind him — Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy; Why Nations Fail; and The Narrow Corridor, all with James Robinson, of the University of Chicago Harris School – behind him, Acemoglu is among the leading intellectuals of the present day. As heir to the leadership roles played by Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow, and Peter Diamond, he packs intuitional punch as well. Pay attention! Get ready for a battle royale.

The tectonic plates of scientific economics are shifting — large-scale processes are affecting the structure of the discipline. That revolution I mentioned at the beginning? The one in whose coverage we economic journalists are engaged? Its fundamental premise is that, while politics always plays a part in the background, economics makes progress over the years. In other words, Hayek takes a back seat to Acemoglu.

‘The Floating World’ in Worcester

“Old View of the Eight-plank Bridge in Mikawa Province (Mikawa no Yatsuhashi no kozu)”, about 1833-34, (woodblock print; ink and color on paper), by Katsushika Hokusai, in the John Chandler Bancroft Collection, at the Worcester Art Museum. Its part of the show, through March 5 ,called “The Floating World: Japanese Prints from the Bancroft Collection”.

The museum says:

“This winter, travel hundreds of years through one of the most culturally abundant periods in world history. ‘The Floating World’ illustrates the beauty of everyday life through 50 Japanese woodblock prints from the museum’s collection, 48 of which are displayed for the first time. The exhibition pulls directly from WAM’s Bancroft Collection of over 3,700 Japanese prints—the first collection of its kind in the United States.

“‘The Floating World’ focuses on ukiyo-e artworks, a diverse genre created throughout Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868). Translating as ‘pictures of the floating world,’ ukiyo-e prints often depict scenes of leisure and arts regularly enjoyed by the working class during an age of great economic growth. These prints tell stories in the form of intricate tableaus portraying courtesans, kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, dwellings, and landscapes. Intricate and colorful, ukiyo-e prints center themes like resilience and pride, ideas we celebrate today.’’

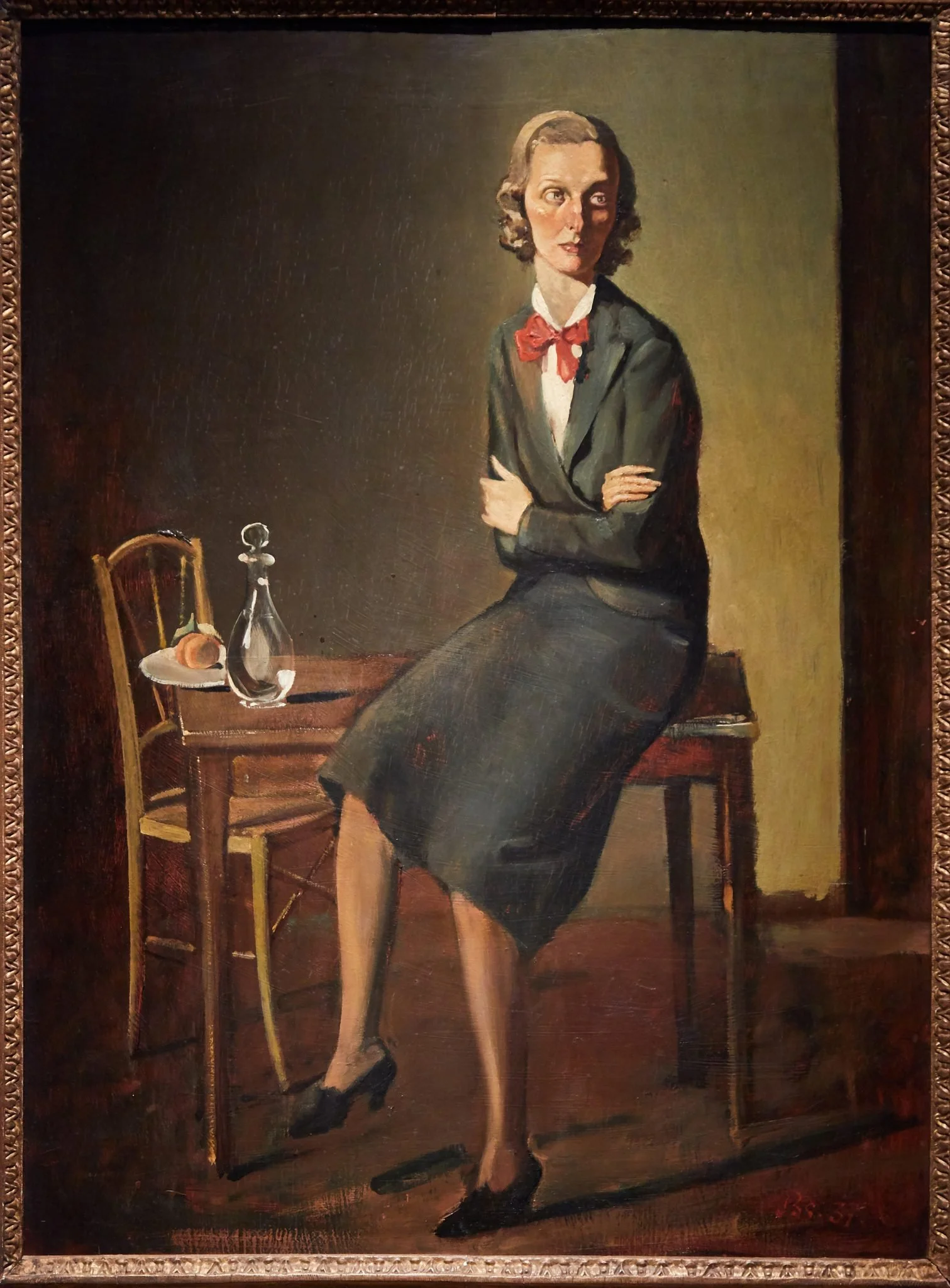

Unhappy honeymooner

“Portrait of Mrs. {Jane} Cooley” (1937, oil on canvas), by “Balthus,’’ in the show of the same name at the Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford. This was painted on Paris, where Mrs. Cooley was honeymooning with her husband, Paul Cooley. They were affluent Connecticut residents. The marriage ended in divorce.

The museum says:

“One of the most controversial artists of the 20th Century, Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski) is best known for his charged imagery of adolescent girls. While his portraits of adult sitters are lesser known today, they played a crucial role in the 1930s, when he painted many of his friends and patrons in his austere Parisian studio. “Portrait of Mrs. Cooley’’ is Balthus’ s first work depicting an American sitter. This painting marks a turning point in the artist’s career, reflective of growing interest in him on this side of the Atlantic. This portrait, on loan from a private collection, joins two paintings by Balthus from the Wadsworth collection and reveals the deeply passionate yet ambivalent relationship between Balthus and his audiences as modern art became fashionable in the United States.’’

Prince William: Why Boston was the place for this

Remarks by Britain’s Prince William in Boston on Dec. 2 on awarding $5 million in grants in the Earthshot Prize program to five people with ideas on saving the planet from global warming:

"There are two reasons why Boston was the obvious choice to be the home of The Earthshot Prize in its second year. Sixty years ago, President John F. Kennedy’s Moonshot speech laid down a challenge to American innovation and ingenuity. 'We choose to go to the moon,' he said, 'not because it is easy but because it is hard.' It was that Moonshot speech that inspired me to launch the Earthshot Prize with the aim of doing the same for climate change as President Kennedy did for the space race. And where better to hold this year’s awards ceremony than in President Kennedy’s hometown, in partnership with his daughter and the foundation {John F. Kennedy Library Foundation} that continues his legacy.’’

"Boston was also the obvious choice because your universities, research centers and vibrant start-up scene make you a global leader in science, innovation and boundless ambition."

‘Beauty and its opposites’

“Onward” (paper, thread, encaustic paint, oil stick on braced panel), by Portland, Maine-based artist Kimberly Curry.

From her artist statement:

“Using my home state of Maine as muse, as well as my travels around the world, I am inspired by the beauty in ordinary things.

“I have a style that ranges from structured seascapes of Maine that capture a point in time to following a concept in a loose abstract way. Among other things, I explore beauty and its opposites.’’

She has an expressive sense of humor and playfulness that sometimes will emerge in the work as well.

The Portland Museum of Art in the Arts District of Portland.

Bd2media -

The Porteous Building, a 1904 beaux arts-style building, houses the Maine College of Art & Design’s classrooms, libraries and galleries.

— Photo by Motionhero

Arctic antiseptic

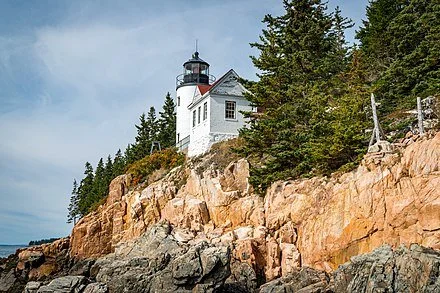

Bass Harbor Light

“Go out,

And the winter

Will clean you….”

— From “Bass Harbor {Maine}—January,’’ by J.B. Goodenough

Chris Powell: PC won’t keep the lights on; legislators fear liquor store lobby

No time soon!

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What is likely to be done about Connecticut's high energy costs and particularly its exploding electricity rates?

Judging from an informational meeting held by Connecticut and Massachusetts officials the other day, nothing that is politically possible would make any difference.

Should Connecticut's two major electricity distributors, Eversource and United Illuminating, which buy electricity for people who can't be bothered to buy their own, purchase that "standard offer" electricity more frequently than the current six-month intervals?

The meeting did not reach a conclusion on that, and whatever the frequency of bulk purchasing, electricity prices still will be set by market forces reacting to supply and demand. When electricity demand rises, as it does in winter's cold and summer's heat, demand and scarcity increase prices.

Should the "standard offer" be eliminated and people be required to buy their own electricity directly from generating companies? It's easy and it would be good for people to have to shop for electricity just as they shop for groceries, an option that Connecticut residents have had for 20 years. But no one in authority proposed this, perhaps because it would diminish the ability of elected officials to blame the electric utilities for the inflation caused by elected officials themselves.

It was acknowledged at the meeting that increasing energy supplies to Connecticut could solve the price problem, as by running high-capacity power lines into southern New England from Quebec, which has an abundance of clean hydropower to export, and by running more natural gas pipelines across New York into Connecticut. But Maine, New Hampshire and New York have been objecting and stalling those projects, and no one in authority has proposed inducing Gov. Ned Lamont and Connecticut's congressional delegation to seek the federal government's intervention to increase supply.

Of course more electricity could be generated from oil, and more oil-based generation facilities could be built in the state. But the Biden administration and liberal Democrats in both the General Assembly and Congress want to destroy the domestic oil industry, believing that fossil fuels are ruining the planet. So no one in authority in Connecticut is proposing any electricity solution involving oil either.

Connecticut apparently will wait a few years, if not longer, for electricity to arrive from windmills yet to be installed on platforms in the sea south of the state, which themselves may be delayed by someone else's objection.

In the face of rising electricity prices, Connecticut's elected officials seem able to offer no more than increasing subsidies for electricity use by the poor, thereby transferring and camouflaging costs and worsening inflation by increasing the money supply without increasing the power supply.

For the time being, there is no way to get electricity prices down except through greater production and delivery of fossil fuel. That is, the only solution is politically incorrect, and few elected officials have the courage to tell their constituents that political correctness will not keep their lights and heat on and electricity bills down this winter.

Detail from “Corrupt Legislation” (1896), by Elihu Vedder.

With Connecticut's supermarkets launching a campaign to change state law so they can sell wine in addition to the beer they already sell, a recent poll of viewers of Hartford's WFSB-TV3 found a huge majority in favor. This was hardly surprising, since one-stop shopping would be so much more convenient and the only objection comes from those who want less competition and higher prices -- most liquor stores.

But the more the supermarkets press the issue, perhaps the more Connecticut residents will see that the public interest seldom determines state law. Instead the special interest does.

Amid the campaign by the supermarkets, state legislators will hear repeatedly from the liquor stores in their districts -- on average, eight in each state representative's district and 30 in each senator's. Their business model is what economics calls rent seeking -- that is, a permanent government subsidy at the expense of everyone else. Legislators will hear from few consumers.

Journalism might change this by vigorously questioning legislators about their subservience to the liquor lobby. But as journalism declines, all special interests will thrive.

Chris Powell (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com) is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.