‘Ammo boxes into icons’

“Icon of the Archangel Michael,’’ by Sofia Atlantova, at the Museum of Russian Icons, Clinton, Mass., in the show “Artists for Ukraine: Transforming Ammo Boxes into Icons,’’ through Feb. 13 Painting on loan from Catherine Mannick.

The museum explains that the show presents three Ukrainian icons painted on the boards of ammunition boxes by Oleksandr Klymenko and Sofia Atlantova, a husband-wife artistic team from Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine.

“The project ‘Buy an Icon—Save a Life’ was developed in response to the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine, when Klymenko encountered empty wooden ammunition boxes from combat zones and noted their resemblance to icon boards (doski). By repurposing the panels, the project strives, in the artist’s words, ‘to transform death (symbolized by ammo boxes) into life (traditionally symbolized by icons in Ukrainian culture). The goal, this victory of life over death, happens not only on the figurative and symbolic level but also in reality through these icons on ammo boxes.’

“Exhibitions of the ammo box icons have been staged throughout Europe and North America to raise awareness of the ongoing war in Ukraine. In addition, sales have provided substantial funds to support the Pirogov First Volunteer Mobile Hospital, the largest nongovernmental undertaking to provide medical assistance to the Donbas region. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 strengthened the resolve of Atlantova and Klymenko to continue painting icons on boards taken back from the frontlines. To date, the project has raised more than $300,000.’’

The Clinton Town Hall was built in 1909. Designed by Peabody and Stearns, it replaced the previous Town Hall, built in 1871-1872, destroyed by fire in 1907. Even fairly small New England towns often built impressive town halls in the late 19th and early 20th centuries out of civic pride.

But not for exterior use

“Gloucester Linens” (acrylic on marine canvas), by Barbara Aparo, at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.

The noted Shingle Style Essex Town Hall and Public Library, in Essex, Mass. (1894), designed by Frank W. Weston.

‘Large and small visions of nature’

“Multi-cellular” (watercolor, colored pencil, ink and encaustic medium on Strathmore mixed media paper), by Cambridge, Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

She says:

“Nature, color and climate change inspire my art. By representing the beauty and diversity of the natural world, I hope to inspire viewers to take a closer look at the world around us, and ultimately be more thoughtful and careful stewards of our planet. I bring my background in marine biology and environmental studies and the experience of years spent both on the ocean and in the backcountry to my art. I paint, print and work in wax to represent large and small visions of nature from the earth from space to frogs, cells and diatoms.’’

Cambridge City Hall.

Another triumph for New England biotech?

The Philip A. Sharp Building, in Cambridge, which houses the headquarters of Biogen

— Photo by Astrophobe

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’ in GoLocal24.com

This is another “we’ll see’’ situation that gives hope.

Japan’s Eisai Co. and Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen Inc. have developed a drug, called lecanemab, that destroys the amyloid protein plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Patients in the drug trial have had a slowing of symptoms. Researchers have much to learn about the drug’s benefits, side-effects and cost, but the apparent breakthrough may the most hopeful sign yet that a highly effective treatment of this terrible dementia might be in the offing.

Hit this link for The New England Journal of Medicine article on this.

Further, since the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain is also seen in such (usually) old-age-related ailments as Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease, lecanemab may have wider applications than just for Alzheimer’s as the population continues to age.

This could be another triumph for New England’s bio-tech industry, but it may take many months to find out for sure.

David Warsh: Those missed Nobel Prizes

Front side of a Nobel Prize.

Photo by Jonathunder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.,

When Dale Jorgenson died last summer, of long Covid, at 89, sighs were heard throughout the worldwide community of measurement economists. Had the Swedish authorities at long last been preparing to recognize the founder of modern growth accounting? Did the Reaper rob the Harvard University econometrician of his Nobel Prize?

Probably not. It seemed that, barring exigency, the Nobel panel had decided long ago to pass him by. It was left to Martin Baily, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, to tell The Wall Street Journal’s James Hagerty that Jorgenson “should have been awarded a Nobel Prize….” The same has been said of many other often-nominated candidates, including, for example, American novelists Philip Roth, of Connecticut, and John Updike, of Massachusetts.

On a memorial service yesterday, in Harvard’s Memorial Church, it almost didn’t matter. The talk was of families, friendships, skits (including one in which Jorgenson was portrayed as Star Trek’s Mr. Spock): the old days, when the Harvard Economics Department’s youngers members and their students were housed in a converted hotel across the street from IBM’s mainframe computers. Colleagues Barbara Fraumeni, Mun Sing Ho and Benjamin Friedman spoke; so did Jorgenson’s former student Lawrence Summers. Another former student, Ben Bernanke, whose undergraduate thesis Jorgenson supervised, missed the service, on his way to Stockholm to share a Nobel Prize; the two had remained in life-long touch.

Still, the question remained, why not Jorgenson?

Certainly it was not for lack of dominating achievements in his chosen field, of growth and productivity measurement. Born in 1933, Jorgenson grew up in Montana, attended Reed College, in Portland, Ore., and, in 1959, received his PhD from Harvard, where future Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief had supervised his thesis. He took a job at the University of California at Berkeley, where he taught the graduate theory course.

In 1963 Jorgenson published “Capital Theory and Investment Behavior.” When a committee selected the 20 most important papers that the American Economic Review had published in its centenary celebration, Jorgenson’s article was among them – the only contribution to have appeared in print immediately, without the customary wait for referee reports. The 13-page paper was revolutionary in two ways, according to Robert Hall, of Stanford University:

It combined finance with the theory of the firm to generate a coherent theory of the firm’s purchase of capital inputs, an area of considerable confusion prior to Jorgenson’s work. And it also laid out a paradigm for empirical research that called for serious economic theory to provide the backbone of the measurement approach. Jorgenson showed how to integrate data and theory.

As Berkeley boiled over with student protests in the 1960s, its best economists began to leave for Harvard: first Richard Caves and Henry Rosovsky, then David Landes, and, in 1969, Jorgenson. They were part of Harvard’s response to having been eclipsed in economics beginning 25 years earlier, by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Kenneth Arrow, Zvi Griliches, Martin Feldstein, and John Meyer were recruited as well, from Stanford, Chicago, Oxford and Yale respectively.

In 1971, Jorgenson won the bi-annual John Bates Clark Medal, awarded for contributions to economics before the recipients turned 40, as had Griliches, in 1965, and Arrow, in 1957. Feldstein would be similarly recognized in 1977.

Jorgenson’s contributions continued at a steady pace for more than 50 years at Harvard. The most significant of these was a successful campaign to produce industry-by-industry input-output tables with which to elucidate national income accounts prepared in the 1930s. Aggregate growth accounting depended fundamentally on the concept of value-added, according to John Fernald, author of a comprehensive account of Jorgenson’s career.

But Evsey Domar had written as early as 1961 that value-added accounting was only “shoes lacking leather and made without power.” To identify the changes occurring in productivity a complete set of input-output tables would be required, disaggregated by industry, linking Leonief/Jorgenson accounting with the old national income accounts designed by Nobel laureate Simon Kuznets. .

Working with Ernst Berndt, Frank Gollop and Barbara Fraumeni, among others, Jorgenson gradually created a granular new account of the sources of growth, differentiating between inputs of capital (K), labor (L), energy (E), and materials (M). The purchase of services (S) were subsequently broken-out. Hence the KLEMS system of productivity and growth accounting, now used by governments around the world. Jorgenson served as president of the American Economic Association in 2000.

I knew Jorgenson as news people know their subjects, and I have known many of his students, too. I never followed growth accounting closely, though I read Diane Coyle’s beguiling little book GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History (Princeton, 2014), and I was sufficiently absorbed by Fernald’s Intellectual Biography of Jorgenson to suspect that a second golden age of nation income and productivity accounting, or perhaps one of platinum, already has begun. (For an especially artful introduction to the KLEMS system, see Emma Rothschild’s essay, “Where is Capital?” in Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics).

Nor do I know much about early 19th Century naval history. There was, however, something in Jorgenson’s leadership style (and a leader he unmistakably was) that reminded me of the lore surrounding Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson – his precise and formal manner, clipped speech, wry humor, zest in explaining to friends the innovations he prepared, and the admiration and loyalty he elicited from his students and colleagues.

Hearing their stories over the years, I was reminded one day of the signal that Nelson sent his squadrons as the battle of Trafalgar was about to begin – “England expects that every man will so his duty.” Never mind that “the little touch of Dale in the night” sometimes meant wakefulness on nights before examinations. More often his most successful students spoke of encouragement and surprising warmth. Further evidence of the inner man: a 50-year marriage to a professionally successful wife, two children (he worked at home three days a week) and three grandchildren.

If Jorgenson’s sense was that the Swedes, too, would do their duty, apparently they did not conceive their duty quite the same way. Perhaps the pride he took in his work was too obvious to them. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1989, sometimes seen as a consolation prize. Perhaps too much umbrage had been given MIT; there were those 13 volumes of Jorgenson’s collected papers, published with the author’s subvention, five more than those of Paul Samuelson; Griliches had been embarrassed to publish one. (The one-time collaborators (“The Explanation of Productivity Change,” in 1967) were often nominated together for their complementary work.)

Griliches died in 1999; Jorgenson soldiered on, adding to his portfolio the economics of energy, the environment, emerging nations’ development, and even pandemics, via the KLEMS system. He became embedded in the major tax debates of the day. But the attention that theoretical economists paid to increasing returns to scale beginning in the ‘80’s was of little interest to an apostle of neo-classically based empirical analysis.

Jorgenson was sometimes called a “Reedie,” after the selective college he attended, celebrated for a distinctive sort of intellectuality, rivaled by Cal Tech, Swarthmore College and St. Johns College. Some 1,500 undergraduates today, 175 faculty members, providing constant feedback but no grades in real time, a measure thought to encourage hard work and long horizons. Only after they had graduated and applied to graduate schools were their transcripts revealed. Legend had it that Jorgenson was among the handful who over the years had received straight A grades in all his courses, and perhaps a few beyond. Certainly he received encouragement from Carl M. Stevens, a 1951 Harvard PhD in economics then teaching at Reed.

Touring a plaza of his hometown library that had been named for him, the author Phillip Roth was asked if the cold-shoulder from the Swedish Academy bothered him. “Newark is my Stockholm,” Roth replied. Reed College was Jorgenson’s Newark; bi-annual KLEMS project meetings are his Stockholm.

David Warsh, veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Not for kindling

“Untitled”’ (wooden sticks), by Charles Arnoldi, in the show “On the Edge: Los Angeles Art 1970s-1990s,’’ at the Armenian Museum, Watertown, Mass., through Feb. 26.

Expansion of the surveillance society

“Nadar Elevating Photography to the Level of Art” (1862 lithograph), by Honore Daumier (French, 1808-1879), in the show “On the Horizon: Art and Atmosphere in the Nineteenth Century,’’ at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass., through Feb. 12.

— Photo by Clark Art Institute

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (1820-1910) known by the pseudonym Nadar, was a French photographer, caricaturist, journalist, novelist and balloonist. In 1858, he became the first person to take aerial photographs.

The show analyzes how some artists incorporated new scientific and technological discoveries about the atmosphere into their work. For more information, please visit here.

David Warsh: Tim Ryan says time to ‘Leave the age of stupidity behind us’

“An Allegory of Folly” (early 16th century), by Quentin Matsys

— EC Publications

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the one ostensible mistake I made in what I wrote about the run-up to what did in fact turn out to be a nobody-knows-anything election.

To my mind, the most interesting contest in the country is the Senate election involving 10-term Congressman Tim Ryan and Hillbilly Elegy author J. D. Vance, a lawyer and venture capitalist. That’s because, if Ryan soundly defeats Vance, he’s got a good shot at becoming the Democratic presidential nominee in 2024.

Even now I don’t think that I was altogether wrong.

Thanks to the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, we know why Ryan lost. Vance, who was on the ballot because Donald Trump endorsed him, trailed Ryan by significant margins until mid-summer. That was when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell invested more than $32 million in the Ohio Senate race, via a super-PAC he controlled, 77 percent of all Republican campaign media spending in the Ohio election after mid-August. Most of it was negative “voter education,” enough to tip the balance against “taxing-Tim” for having voted for various Biden measures. The power of money in American elections may be a scandal, but by now it has been well-established by the Supreme Court as a fact of life.

It seems nearly certain to me that the next president will be someone born in the ‘70’s, not the ‘40’s. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat was probably correct when he wrote last week that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is likely to be the Republican nominee. DeSantis, 44, was born in 1978.

Douthat may have been wrong, however, in thinking that DeSantis’s “sweeping success” in his re-election campaign validated the theory that “normal” doesn’t have to mean “squishy.” The tough-guy approach worked well in Florida. DeSantis was “an avatar of cultural conservatism, a warrior against the liberal media and Dr. Anthony Fauci, a politician ready to pick a fight with Disney if that’s what the circumstances require.”

But a better-mannered Donald Trump may not be what the majority of voters will be looking for in the next election. Tim Ryan, 49, was born in 1973. If you have time, and want a lift, watch Ryan’s 15-minute concession speech to get a feel for the man. Pay special attention to the six-minute mark, where Ryan speaks to the audience beyond the room he is in.

The words in that middle portion of that speech strike a powerful chord: “This country, we have too much hate, too much anger, there is way too much fear, way too much division. We need more love, more compassion, more concern for each other. These are important things. We need forgiveness, we need grace, we need reconciliation. We do have to leave the age of stupidity behind us.”

There are many question to be answered. First among them: are Ryan and his family willing to undertake a two-year front porch campaign? If so, a 10-term former congressman has a reasonable chance to win both the Democratic Party’s nomination, and the 2024 election itself.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Small-town presidential politics

Cohasset Town Common, with Congregational church in the center background and the Unitarian church partly obscured by trees at left.

—Photo by Wwoods

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I rather fuzzily remember a flag-filled, informal motorcade in Cohasset, Mass., in 1956 for “Eisenhower for President’’. It was a fresh late-October day, with a northwest wind pulling the remaining red and orange leaves off the maples and the muted yellow ones off the hour-glass-shaped elms, of which we still had many, although Dutch elm disease was rapidly killing them off. Kids and their young parents applauded alongside the road.

We proceeded in our station wagon over a little bridge near the harbor and headed toward the classic town common (you can see it in The Witches of Eastwick), with the little pond with a fountain on a rock island in the middle of it. At the common, I recall, a generally genteel GOP campaign rally took place.

On two sides of the common were the two very white (in two senses of the word) Unitarian and Congregational churches. Nearby, on top of a granite outcropping, presided the neo-Gothic St. Stephen’s Church, a monument of the WASP upper-middle and upper class in the rather WASPY town. The local clan who owned much of Dow Jones & Co. had financed much of its building. See picture below of St. Stephen’s aristocratically looming over Cohasset’s downtown, next to the common.

The old line about the Episcopalians was “the Republican Party at prayer.’’ No more.

The town’s Catholic church, St. Anthony, was a few blocks away, in that still majority Protestant town. Its parishioners were generally of Irish, Italian and Portuguese background. We Protestants felt sorry for the Catholic kids because they had to go to catechism and confession (gulp!) and couldn’t eat meat on Fridays. The last rule, however, provided very good business for the local fishing fleet.

The more liberal and, for that time, “Bohemian,’’ folks attended the Unitarian Church – for which the joke motto was “the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man and the neighborhood of Boston.’’ The Unitarians removed as much as they could assertions about the divinity of Jesus from their hymns and liturgies. As the years passed, even references to God diminished. General, diffuse celebrations of the glories of nature and plugs for the Civil Rights Movement replaced them. The minister had the lovely name of the Rev. Roscoe Trueblood.

The Congregational (aka “Congo”) church in Cohasset was only vaguely Trinitarian. The Congos were more or less the direct descendants of the Puritans, the Unitarians less directly so.

There also was, and still is, a Hindu temple in town!

Back to the campaign motorcade. Some kids sang “Whistle while you work, Stevenson is a jerk,’’ of course a play on the song “Whistle While You Work,’’ from the Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which all the children had seen.

It already seemed to me that politics was harsh.

Is it politically incorrect now to refer to “dwarfs’’?

The town and most of the rest of America went heavily for Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) over a former Democratic governor of Illinois, Adlai E. Stevenson (1900-1965). But the Republican Party was a very different creature from its current version, and Ike was a good, middle-of-the road president, supporting incremental improvements in federal domestic programs and warding off war. Both Eisenhower and Stevenson were notably dignified.

You can understand why a few years later, soon before his death, a very tired Stevenson, then U.S. ambassador to the U.N., would say that “All I really wanted was to sit in the shade with a glass of wine and watch the dancers.” I’m pretty sure that many of us, tired of the increasing toxicity and tumult of public life, would sometimes want to declare a separate peace and maybe flee, with no forwarding address, and certainly no social media, to some remote, Arcadian place. One thinks of the phrase “a separate peace’’ in Hemingway’s World War I novel A Farewell to Arms and John Knowles’s boarding-school novel, set in World War II, A Separate Peace.

In the Cohasset air was the aroma from piles of raked up (not blown!) leaves being burned – an activity now banned, mostly for public health reasons. Many of us of a certain age still miss that sweet smell, now replaced in too many neighborhoods by the aroma of gasoline from shrieking leaf blowers. Before their parents burned the leaves, small children loved to burrow into big piles of them.

Ah, youth! I remember with a pang the town’s scenic shores and the material comfort available to so many of its residents, along with dark scenes out of a Eugene O’Neill play.

The balm of blue

“I Have Loved Many Colors” (encaustic monoprint), by Brookline, Mass.-based Lola Baltzell, in her show ‘Dabbling in Blue Magic,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 4-27.

She tells the gallery:

"One of my favorite authors is {the late novelist}Vladimir Nabokov, and the title of this show is a nod to his imagery. One remarkable thing about his writing is that English is his second language. He refers to color frequently, my true love language.

Blue. Why Blue Magic?

All the work in this show is encaustic, also known as hot wax, and includes collage, painting and monoprints. I don't typically work in blue, yet all the pieces in this show are blue. I've spent a lot of the pandemic in the water - metaphorically and literally. Feeling adrift, lost at sea, looking for terra firma, yet I sought solace on the water, spending as much time paddleboarding as possible. Working in blue has felt like a balm, soothing, healing. My own blue period."

Views of Brookline

Photo collage by Ddogas

Take that!

“Hamada” (oil on canvas), by L.G. Talbot, in the show “LG Talbot: New Generation Abstraction,’’ at the University of Massachusetts Fine Arts Center, Amherst, Mass.

The exhibit features abstract work that takes on American abstract painting through large and bold paintings that "convey a distillation of lived experience,’’ says the artist whose home is in the western Massachusetts hill town of Conway and whose studio is in Easthampton, Mass.

Talbot’s artist statement says:

“In the new paintings, I work with palette knives to quickly establish images on the canvas. I keep 4-5 large canvases open – working them simultaneously – impatient for the oil to dry. Images organically surface on the picture plane. I layer more paint and create more texture. My colors have also changed. The primary colors of previous work have been usurped by a more nuanced palette replete with earthy tones. I mix the pigment, thin it out with turpentine, and build the painting in layers. This is my evolution: Borders gone, Colors blended. The pandemic is a reminder of the privilege of being alive – my every day in the studio is charged and intoxicating.’’

Historic Bardwell's Ferry Bridge, in Conway.

— Photo by Doug Kerr

View of Mt. Tom from the center of Easthampton

Existential confusion

Inside Greg’s Famous Seafood, in Fairhaven, Mass.

— Photo by William Morgan

David Warsh: The WSJ ‘contains multitudes’

On Chicago’s Lakefront.

— Photo by Alanscottwalker

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

A headline on a story Oct. 21 in the in The Wall Street Journal revealed “Chicago’s Best-Kept Secret: It’s a Salmon Fishing Paradise; Locals crowd into inlets off Lake Michigan to catch fish imported from West Coast to counter effects of invasive species.”

Between vignettes of jubilant fishermen braving the lake-front weather, reporter Joe Barrett offered a concise account of how Great Lakes wildlife managers have coped with successive waves of invasive species over eighty years of globalization. In the beginning were native lake trout, apex predators thriving on shoals of perch. Sea lampreys arrived in the Forties, through the Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario with Lake Erie. The blood-sucking eels devastated the trout population, while alewives, another invasive species, grew disproportionately large with no other to prey on them.

Authorities controlled the lampreys with a new pesticide in the mid-Sixties, and imported Coho and later Chinook salmon from the West Coast to rejuvenate sport fishing. Fingerling salmon hatched in downstate Illinois nurseries were released in Chicago harbors, to return to the same waters to spawn at maturity. Meanwhile, ubiquitous European mussels, released from ballast tanks of ships entering the lakes via the St. Lawrence Seaway, improved water clarity, but consumed nutrients needed by small fish. As a native of the region, I remember every wave.

A Coho salmon.

I was struck by the artful sourcing of Barrett’s story. He quoted fishermen Andre Brown, “a 51-year-old electrician from Oak Park;” Martin Arriaga, “a 59-year-old truck driver from the city’s Chinatown neighborhood,” and Blas Escobedo, 56, “a carpet installer from the Humboldt Park neighborhood.”

Providing the narrative were Vic Santucci, Lake Michigan program manager for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and Sergiusz Jakob Czesny, director of the Lake Michigan Biological Station of the Illinois Natural History Survey and the Prairie Research Institute. The Illinois Department of Health chimed in with its recommendation: PCB concentration in the bigger fish meant no more than one meal a month.

Barrett did not mention the dangerous jumping Asia carp that now threaten to enter Lake Michigan; nor the armadillos, creeping north from Texas into Illinois, with global warming: much less the escalating crime rates in Chicago, which have McDonald’s threatening to move out of the city. But then his was a story about fishery management. And that’s what I like about the WSJ: it contains multitudes.

Earlier last week I had sought to convey to visiting friends the different sensibilities among the newspapers I read. I prize The New York Times for any number of reasons, but its concern for the future of democracy in America often seems overwrought. I look to The Washington Post for editorial balance (never mind the “Democracy Dies in Darkness” motto), and to the Financial Times for sophistication. But it is hard to exaggerate how much I enjoy The Wall Street Journal. I worked there for a time years ago; that surely has something to do with it. But I think it is the receptivity of its news pages I so admire. Like Joe Barrett’s fish story, its sentiments are inclusive. Read it if you have time.

Despites its sale to conservative newspaper baron Rupert Murdoch, the WSJ has preserved the separation between sensible news pages, its worldly cultural and lifestyle coverage, and its fractious editorial pages. Those editorial pages are still recovering from their enthusiasm for Donald Trump, and I sometimes think as I read them that they pose a threat to democracy, if only by their preference for derision. But still I read them, so they must be doing something right.

Barely two weeks remain before the mid-term elections. The races that interest me most are those seeking common ground: Ohio, Alaska, Pennsylvania, and Oregon. There will be time afterwards to sift the results. Is American democracy in danger? I doubt it. E pluribus unum! with a certain amount of thoughtful guidance along the way.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

An economic-mobility hub

The spectacular fare lobby of the Alewife MBTA station. The station is also known for its art works, inside and out. See photo at bottom.

— Photo by Eric Kilby

Edited from a New England Council report (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Rockland Trust Bank, based in Rockland, Mass., has announced a grant of $50,000 to Just A Start. The grant will be used to help support Just A Start, a new economic-mobility hub near the Alewife MBTA station, in North Cambridge.

“The new Economic Mobility Hub will be a 70,000-square-foot, mixed-use project. The goal of the project is to create a thriving and equitable community to accelerate economic mobility. Once completed the building will include 24 affordable apartments, four pre-school classrooms and a 19,000-square-foot training center. This new home for Just A Start will offer workshops and other programming to serve 2,800 people in Cambridge and Metro-North communities. The project will be open in April 2024.

“Andrea Borowiecki, Vice President of Charitable Giving and Community Engagement at Rockland Trust, said, ‘Our Charitable Foundation is honored to contribute to the development of this important project for the Greater Boston communities. The project perfectly aligns with what Rockland Trust as a community-orientated bank believes in, by providing resources to our neighbors that enable them to flourish to their full potential.”’

“Alewife Cows,’’ by Joel Janowitz

Sculpture outside the Alewife station by Toshihiro Katayama

Photo by Pi.1415926535

David Warsh: Exploring ‘quantum weirdness’

Main building of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, in Stockholm.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I spent its time last week reading up quantum entanglement. Instantaneous connections between far-apart locations – the possibility of “spooky action at a distance” that was dismissed by Einstein – turns out to have become the basis of quantum computing and fail-safe cryptography.

First I read The New York Times story: Nobel Prize in Physics Is Awarded to 3 Scientists for Work Exploring Quantum Weirdness. by Isabella Kwai, Cora Engelbrecht and Dennis Overbye. I especially liked the part about John Clauser’s duct-tape and spare-parts experiment in a basement at the University of California at Berkeley that opened the laureates’ path to the prize. (Stories in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each had distinctive strong points as well.)

The Times story led me back to MIT physicist/historian David Kaiser and his 2011 book, How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival. I didn’t read it when it appeared, having a mild prejudice against hot tubs, psychedelic drugs and saffron robes. I was wrong. I ordered a copy last week.

Next was a Science magazine piece from 2018 by Gabriel Popkin that showed the discoveries well on their way to acceptance: Einstein’s ‘spooky action at a distance’ spotted in objects almost big enough to see.

Then came a Scientific American article, The Universe Is Not Locally Real, and the Physics Nobel Prize Winners Proved It, by David Garisto, that seemed to me to offer the most lucid explanations of the profound uncertainties involved. These are more daunting than ever in the face of irresistible technological evidence that they exist.

At that point I returned to the Nobel announcement, and skimmed the citations in the scientific background to see if the story was as I had been taught (by my mother, Annis Meade Warsh, who was herself entangled with science and religion!). Sure enough there among the citations was the history of the argument, from Erwin Schrödinger, in 1935; to Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, in 1935; to David Bohm, in 1951; to John Stewart Bell, in 1964; and to Stuart Freedman and Clauser (the former having been Clauser’s graduate student), in 1972. Imagine my surprise last year when I discovered the distinguished historian of physics John Heilbron was reading Bohm’s last book, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, the very title recommended to me by my mother not long after its publication, in 1980. I checked Wholeness out from the library. I could not fathom the implicated order.

In fact, the most beguiling explication of the prize I found was the 15-minute talk that Nobel Committee member Thors Hans Hansson gave to journalists after the prize announcement in Stockholm last week. The 72-year old theoretical physicist personified the combination of collective energy, sobriety and delight that enables the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to keep the world abreast of developments, year after year.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Argon art; this old house

“Portrait of Joan” (hand-blown and colored glass tubing, argon gas with mercury transformer), by Laddie John Dill, at the Armenian Museum, Watertown, Mass., in the show “On the Edge: Los Angeles Art 1970’s-1990’s’’

Abraham Browne House, in Watertown, built around 1694. It is now a nonprofit museum operated by Historic New England.

The house was originally a simple one-over-one dwelling and features steep roofing and casement windows, recalling many 17th Century English dwellings. During restoration work in 1919, details of 17th Century finish were found. The ground floor has one large room, which was used for as a sort of living room as well as for cooking and sleeping.

The building may be one of fewer than a half-dozen houses in New England to retain this profile.

— Photo by Wayne Marshall Chase

Surprise airborne invasion

“Soft Landing” (encaustic collage, ink), in the large group show “Flights of Fancy,’’ at Gallery Twist, Lexington, Mass., through Oct. 16.

William Barnes Wollen’s painting of the Battle of Lexington, which took place on April 19, 1775. With the Battle of Concord the same day, it was the start of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783)

It’s at the National Museum of the U.S. Army, in Fort Belvoir, Va.

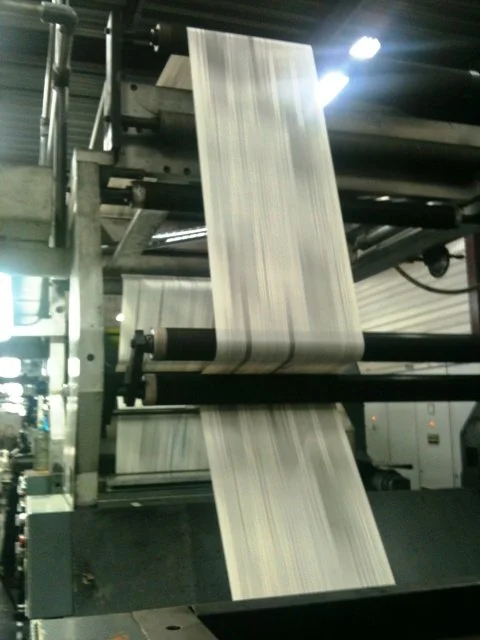

David Warsh: To come back, print editions of newspapers must solve intricate production problem

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The off-lead story in the Sept. 18 New York Times, illustrated by a fraying American flag, was one of a series: “Democracy Challenged: twin threats to government ideals put America in uncharted territory.” Senior writer David Leonhardt identified two distinct perils: a movement in one major party to refuse to accept election defeat, and a Supreme Court at odds with public opinion. Leonhardt’s argument was well reasoned and deftly written, enough to fill four pages after the jump.

To my mind, though, The Times is overlooking a problem even more fundamental to the conduct of American democracy: the concentration of power in the quartet of daily newspapers that remain at the top of the first-draft-of-history narrative chain. The loss of diversity of news and opinion among metropolitan newspapers in the 50 American states over the last thirty years has not been well understood.

Media proprietor Rupert Murdoch bought The Wall Street Journal from the Bancroft family, in 2007. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post from the Graham family, in 2012. Japanese media group Nikkei acquired the Financial Times from Pearson publishers, in 2015. The New York Times, a fifth-generation family-controlled firm, retains its independence. But Bloomberg LP, an all-digital software analytics and media company, also based in midtown Manhattan, remains looking over its shoulder.

Meanwhile, major metropolitan daily newspapers across the country have been sold and diminished, or collapsed altogether, in the 32 years since the World Wide Web was introduced. These include the Chicago Tribune and its many subsidiaries, among them the Los Angeles Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Hartford Courant and the New York Daily News; The Providence Journal; The Philadelphia Inquirer and 31 other Knight Ridder newspapers, including The Miami Herald and San Jose’s Mercury News; Cleveland’s Plain Dealer, Portland’s Oregonian and New Orleans’s Times-Picayune, among the Newhouse newspaper chain; the Louisville Courier-Journal; the Arizona Republic; Las Vegas Sun, and Dean Singleton’s Denver Post. The Daily Bee, founded in Sacramento in 1857, part of all but the last surviving family-owned newspaper chain, declared bankruptcy in 2020, though the Atlanta Journal-Constitution remains the flagship of Cox Enterprises. Only Texas and Florida maintain several competitive metropolitan newspapers. The Christian Science Monitor ceased publishing a paper edition in 2009, while maintaining a digital presence.

What happened? Google and Facebook entered the advertising business. Antitrust newsletter writer Matt Stoller recently described Google’s rollup of the search-intermediary industry over the course of a decade, notably its 2007 acquisition of DoubleClick, into the voracious advertising sales business that the former “free” search engine enterprise has become. Facebook did much the same. The result was that newspapers lost some 80 percent of their advertising revenues in a decade. More than 2,000 papers went out of business altogether.

In a similar vein, The New Goliaths: How Corporations Use Software to Dominate Industries, Kill Innovation, and Undermine Regulation (Yale, 2022), by James Bessen, makes a compelling case that “dominant firms have used proprietary technology to achieve persistent competitive advantages and persistent market dominance,” by more effectively managing market complexity in industries of all sorts.

Strengthening antitrust enforcement is a good idea, Bessen says, but breaking up firms is unlikely to solve the “superstar problem.” A more effective solution has to do with opening up access to knowledge, which means addressing ubiquitous intellectual-property bottlenecks. Market-driven unbundling – the process that, in the 1970s, led IBM to open its proprietary software to independent applications, and, in the Oughts, Amazon to make its information technology software available to other vendors on its proprietary servers – offer more promising possibilities, he asserts in a closing chapter. Bessen heads a research initiative at Boston University’s Law School. The New Goliaths is an important book. Let’s hope it get the attention it deserves.

American democracy is not doomed to a future dominated by four or five national newspapers. There is reason to believe that the market for home-delivered newsprint newspapers is much broader than it now seems, though it may take years to revive it. Radio returned to prosperity after television advertising all but destroyed its formerly lucrative advertising business. Newsprint thrived for nearly a hundred years despite the entry of both.

To come back from the online onslaught, however, print newspapers must solve an intricate coordination problem, involving every aspect of the business. These include the cost of newspaper production, from newsprint to software to printing facilities; the riddle of subscription pricing; the restoration of home delivery networks; and the reconstruction of advertising sales. Moreover, the new newsprint goliaths must cooperate with big city dailies seeking to regain market share if the problem is to be solved.

Take, for example, a narrow slice of the cost of production problem: the software that enables editors to simultaneously assemble and publish both print and online content. Dan Froomkin, a former Washington Post columnist, reports in The Washington Monthly, that Amazon’s Bezos, upon acquiring The Post, discovered that the process was wildly inefficient, whereupon he tasked chief information officer Shailesh Prakesh to fix it.

The result: a best-in-class publishing platform, Arc XP, that the Post now uses to publish its own product, and licenses to 2,000 other media and non-media sites. But the license, Froomkin says, is expensive. His suggestion: that Bezos do as Andrew Carnegie did with his libraries more than a century ago, and make Arc XP available free to other newspaper publishers, along with its companion Zeus Technology ad-rendering platform. It is an interesting proposal. So is the multi-state antitrust lawsuit against Google and Facebook, slowly making its way in a U.S. District Court. Meanwhile, the bipartisan Journalism Competition and Preservation bill inched forward last week, when the Judiciary Committee voted 15-7 to send it to the Senate floor

What size might be the market for subscriber-based print, supplemented by traditional advertising? At what annual price? There is simply of no way of telling besides customary trial and error. Let’s hope that the new newsprint goliaths will participate in the learning. True, the four national papers and Bloomberg do a pretty good job of gathering news on their own. But it seems clear that the American democracy functioned better when there were more strong voices scattered across its landscape. It makes sense to search for ways by which those circumstances can be restored – plenty of fodder for future columns.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com.

Editor’s note, a few newspapers, most notably in New England The Boston Globe, now under control of the Boston-based Henry family, still retain much, but far from all, of their former journalistic package.