David Warsh: The WSJ ‘contains multitudes’

On Chicago’s Lakefront.

— Photo by Alanscottwalker

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

A headline on a story Oct. 21 in the in The Wall Street Journal revealed “Chicago’s Best-Kept Secret: It’s a Salmon Fishing Paradise; Locals crowd into inlets off Lake Michigan to catch fish imported from West Coast to counter effects of invasive species.”

Between vignettes of jubilant fishermen braving the lake-front weather, reporter Joe Barrett offered a concise account of how Great Lakes wildlife managers have coped with successive waves of invasive species over eighty years of globalization. In the beginning were native lake trout, apex predators thriving on shoals of perch. Sea lampreys arrived in the Forties, through the Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario with Lake Erie. The blood-sucking eels devastated the trout population, while alewives, another invasive species, grew disproportionately large with no other to prey on them.

Authorities controlled the lampreys with a new pesticide in the mid-Sixties, and imported Coho and later Chinook salmon from the West Coast to rejuvenate sport fishing. Fingerling salmon hatched in downstate Illinois nurseries were released in Chicago harbors, to return to the same waters to spawn at maturity. Meanwhile, ubiquitous European mussels, released from ballast tanks of ships entering the lakes via the St. Lawrence Seaway, improved water clarity, but consumed nutrients needed by small fish. As a native of the region, I remember every wave.

A Coho salmon.

I was struck by the artful sourcing of Barrett’s story. He quoted fishermen Andre Brown, “a 51-year-old electrician from Oak Park;” Martin Arriaga, “a 59-year-old truck driver from the city’s Chinatown neighborhood,” and Blas Escobedo, 56, “a carpet installer from the Humboldt Park neighborhood.”

Providing the narrative were Vic Santucci, Lake Michigan program manager for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and Sergiusz Jakob Czesny, director of the Lake Michigan Biological Station of the Illinois Natural History Survey and the Prairie Research Institute. The Illinois Department of Health chimed in with its recommendation: PCB concentration in the bigger fish meant no more than one meal a month.

Barrett did not mention the dangerous jumping Asia carp that now threaten to enter Lake Michigan; nor the armadillos, creeping north from Texas into Illinois, with global warming: much less the escalating crime rates in Chicago, which have McDonald’s threatening to move out of the city. But then his was a story about fishery management. And that’s what I like about the WSJ: it contains multitudes.

Earlier last week I had sought to convey to visiting friends the different sensibilities among the newspapers I read. I prize The New York Times for any number of reasons, but its concern for the future of democracy in America often seems overwrought. I look to The Washington Post for editorial balance (never mind the “Democracy Dies in Darkness” motto), and to the Financial Times for sophistication. But it is hard to exaggerate how much I enjoy The Wall Street Journal. I worked there for a time years ago; that surely has something to do with it. But I think it is the receptivity of its news pages I so admire. Like Joe Barrett’s fish story, its sentiments are inclusive. Read it if you have time.

Despites its sale to conservative newspaper baron Rupert Murdoch, the WSJ has preserved the separation between sensible news pages, its worldly cultural and lifestyle coverage, and its fractious editorial pages. Those editorial pages are still recovering from their enthusiasm for Donald Trump, and I sometimes think as I read them that they pose a threat to democracy, if only by their preference for derision. But still I read them, so they must be doing something right.

Barely two weeks remain before the mid-term elections. The races that interest me most are those seeking common ground: Ohio, Alaska, Pennsylvania, and Oregon. There will be time afterwards to sift the results. Is American democracy in danger? I doubt it. E pluribus unum! with a certain amount of thoughtful guidance along the way.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

What this cairn really is

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“I came across this thing while walking in the park near the Roger Williams National Memorial, in Providence. What is it? A memorial to a dead tourist? A Druid astronomical measuring device? A New Age shrine?’’

A friend sent me the answer via the National Park Service. Sorry!

“This cairn, or stone pile, depicts pieces of Narragansett {Tribal Nation} history from pre-contact through today. Built by Narragansett artists associated with the Tomaquag Museum, it expresses the fact that WE ARE STILL HERE. The cairn is at the center with 4 raised stones around it representing the Four Directions. It is a meditative circle, representing Narragansett lives, history, and future which brings us full circle. Sit down and reflect on your own past, present and future and its intersection with the Narragansett people.

“The Narragansett Tribal Nation has lived on these lands since time immemorial. Their ancestors respected all living things and gave thanks to the Creator for the gifts bestowed on them, as do Narragansett people of today. Lynsea Montanari & Robin Spears III, both Narragansett, served as summer arts interns at the memorial for this project. They incorporated their own cultural knowledge with teachings by tribal elders regarding first contact with European settlers, genocide, displacement, assimilative practices, enslavement, continuation of language, ceremony, and other cultural practices. The artists chose to create a cairn as it is a part of the history of all indigenous peoples. There are many historic cairns in the Narragansett landscape.’’

Why we need schedules

Annie Dillard.

— Photo by Phyllis Rose

At Wesleyan University, in Middletown, Conn. The view from Foss Hill: From left to right: Judd Hall, Harriman Hall (which houses the Public Affairs Center), and Olin Memorial Library

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing. A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days. It is a scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labor with both hands at sections of time. A schedule is a mock-up of reason and order—willed, faked, and so brought into being; it is a peace and a haven set into the wreck of time; it is a lifeboat on which you find yourself, decades later, still living.”

―Annie Dillard (born 1945), in The Writing Life. The American author of fiction and nonfiction books taught for 21 years at Wesleyan and has long had a summer house on Outer Cape Cod, a place that she has frequently written about.

Driving another mammal species to extinction via painful deaths

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration staffers trying to free a North Atlantic Right Whale from fishing gear.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s very sad to watch the slow and painful death of “Snow Cone,’’ one of the 350 or so remaining North Atlantic Right Whales. Snow Cone has been entangled in fishing lines south of New England, a reminder of how much we devastate wild fauna, including such highly intelligent mammals as whales. Surely the fishing industry can do much more to protect them. She may well be dead by the time you read this.

One is getting fisheries to use different systems, even if we have to subsidize this to start. To wit, consider this from Oceana:

“Using Innovative, Pop-up Fishing Gear to Avoid Entanglements While Continuing to Fish

“Pop-up fishing gear stays connected to traps on the ocean floor until a release mechanism is triggered that allows a flotation device to surface so fishermen can retrieve the catch. Release mechanisms can be set to release at a certain time (‘timed release’) or upon receiving an acoustic signal from a fishing vessel (“on-demand release”). Because there is no surface buoy, virtual gear marking can notify fishery managers and other fishermen of the location of traps.’’

And:

“Other proposed solutions would sever fishing lines in the event of entanglements, potentially allowing a whale to free itself. These include weak links, Yale grip sleeves and line cutters that in theory would only break the line after an entanglement. Despite these changes being easy to incorporate, none of these solutions prevent entanglements and there is no clear evidence that they allow an animal to free itself.’’ (Italics for my emphasis.)

North Atlantic Right Whale mother and calf.

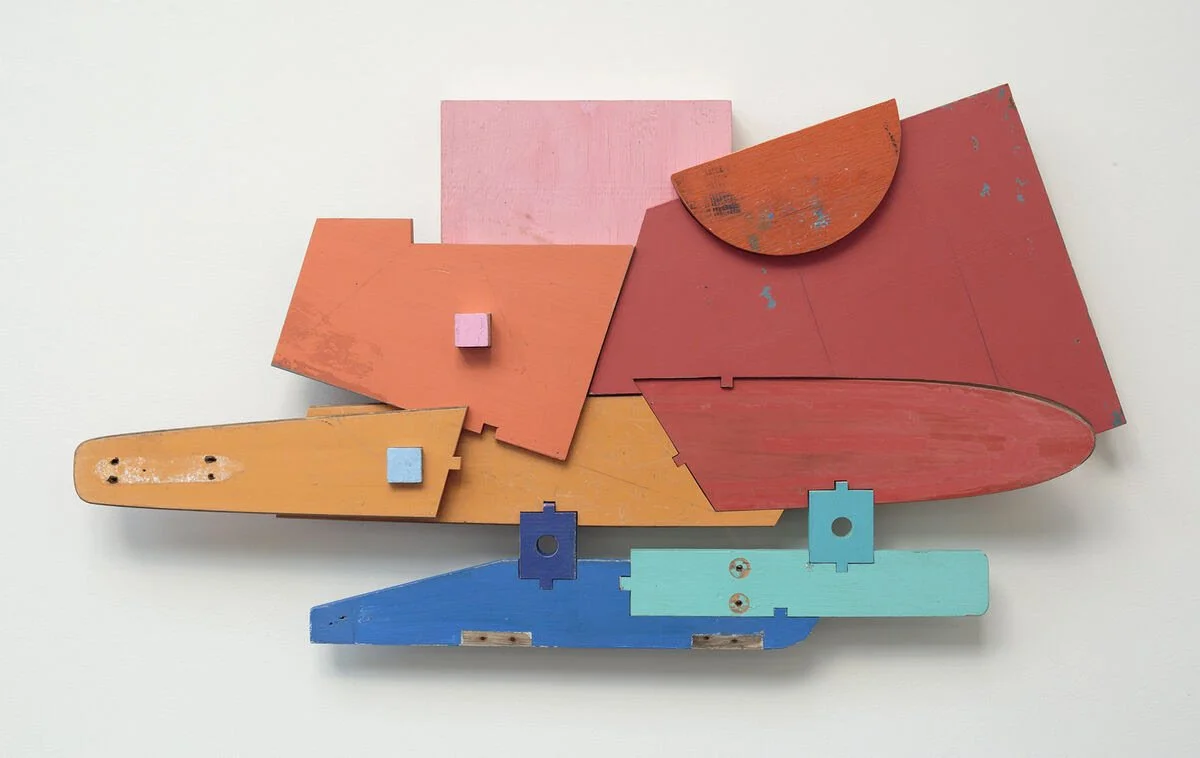

The art of the found

“Sailor's Delight” (found painted wood), by Mike Wright, in her show “WOOD Works,’’ at the Cotuit (on Cape Cod) Center for the Arts, through Oct. 29.

— Photo courtesy Cotuit Center for the Arts

The exhibit displays Mike Wright’s work as a salvager and artist.

The gallery says: “Her whimsical wooden sculptures are assembled from found materials and given new life through clever arrangements. Wright sees the potential that each piece of discarded wood has to become something new, while still retaining its original, unique qualities.’’

Her artist statement says:

“I think of myself as a salvager, in that fascinating Cape Cod ‘Mooncusser’ tradition. My process starts with searching Provincetown beaches and dumpsters for old previously painted wood. The point of using found material is that, as debris, it seems unpromising but that lack of promise is also its appeal. The peeling paint, the color scrubbed by salt waves, sand or human use allows us to recognize the influence of its past. I like the moment when I place the first pieces of old wood, seeing all that potential, seeing relationships of form begin to take shape. I have learned to listen to this found wood and allow for any chance opportunity to emerge, achieving the sculpture through modifying form with minimal carpentry—cutting, joining, sandwiching. The wood had an experience as boat, cabinet or floorboard and it remembers its past. I interfere with what it was made to be, to make it something else: a sculpture that suggests the endless process of transformation of the things of human industry.’’

‘Metaphor for devastation’

Frost at his 85th birthday party, in 1959.

“While he {Robert Frost) was talking he was looking out,

But stayed in, sagacity better indoors.

He became a metaphor for inner devastation,

Too scared to accept my invitation.’’

— From “Worldly Failure,’’ by Richard Eberhart (1904-2005), an American poet. He knew Frost (1874-1963), a giant of English language poetry.

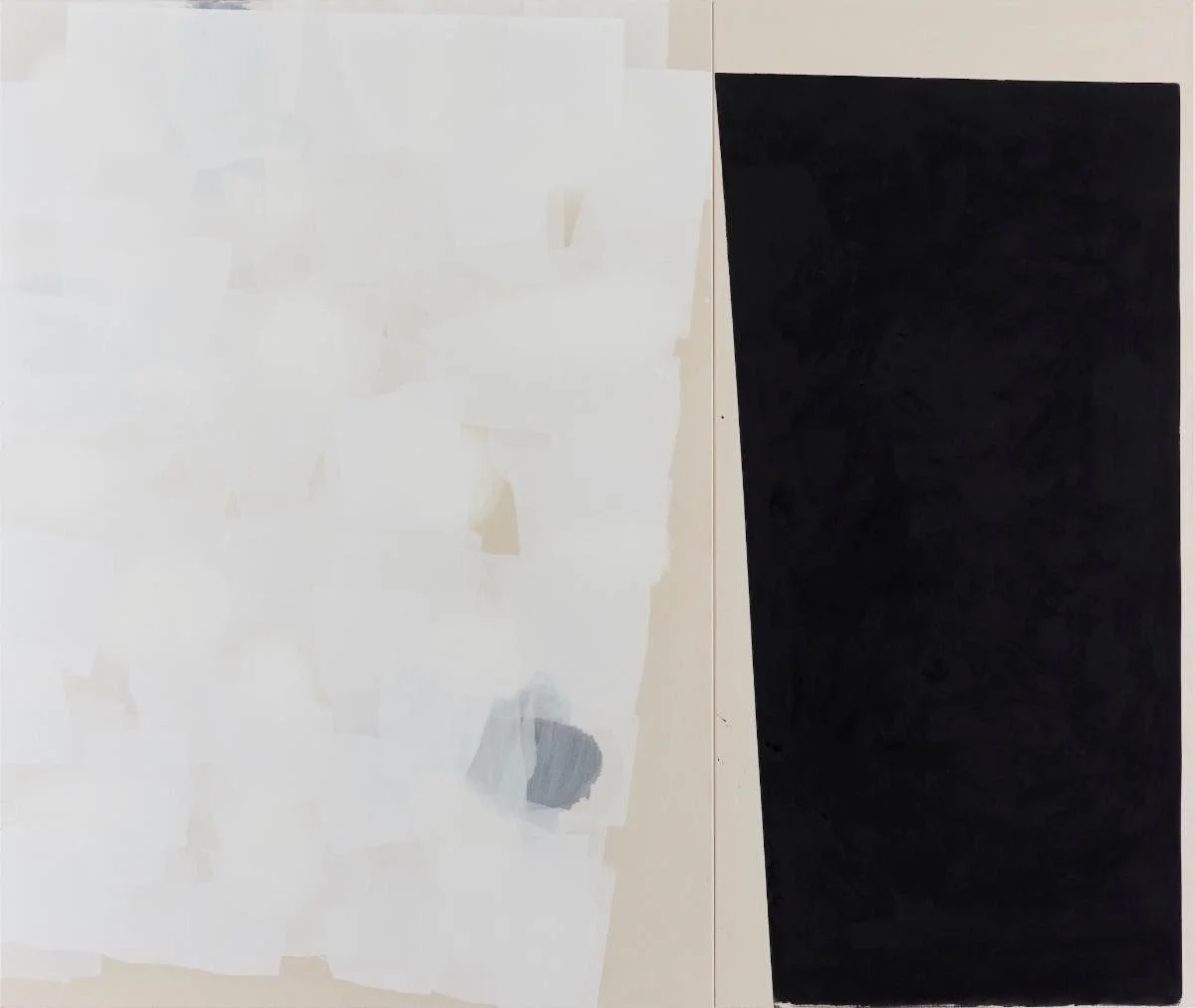

Henge fun and Grace Farms

“Henge XII” (acrylic and oil on canvas; diptych), in Ian McKeever’s show “Henge Paintings,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., through Dec. 3

The gallery says:

“McKeever’s five-decade artistic career has been an ongoing exploration of abstraction through the use of oils and acrylics on canvas or paper. He typically creates works in groups, undertaking several canvases at a time which can take him two or three years to complete.’’

A lonely scene at New Canaan’s train station. It recalls the melancholy that pervades the TV series Mad Men, which mostly takes place in Manhattan and New York’s affluent suburbs in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s.

At Grace Farms, in New Canaan, an 80-acre cultural center. Grace Farms is owned and operated by the Grace Farms Foundation, a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to promote peace through nature, arts, justice, community, faith, and Design for Freedom, a new movement to remove forced labor from the built environment.

— Photo by Karl Thomas Moore

The River building at Grace Farms sits amongst meadows and woodlands in New Canaan.

— Photo by Adam.thatcher

Chris Powell: Delinquent derelict’s family gets rich on the taxpayers

The Hollow neighborhood of Bridgeport, along North Avenue.

— Photo by Lima16

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What happens in Connecticut when a 15-year-old lives in a home with abusive and neglectful parents, drug abuse and violence, ends up on the street, joins his friends in car thefts, gets high on marijuana, steals another car, leads police on a chase, drives the wrong way on a one-way street, strikes other cars, is cornered in a parking lot, puts the car into reverse to escape, knocks over an officer, and is fatally shot by him?

In Connecticut what happens is that the boy's family, who messed him up, gets $500,000 from the City of Bridgeport to settle a lawsuit asserting that his death was actually a federal civil-rights violation.

This presumably will be the final chapter of the story of Jayson Negron, whose life ended in a fairly predictable way in 2017 and reflected the widespread neglect of Connecticut's children and the failure of government to do much about it.

Ironically, the settlement was approved by the Bridgeport City Council this week just as Connecticut, mourning two police officers murdered by a drunken madman in Bristol, sought to show support for police generally. Though the settlement falsely implied that the Bridgeport officer was in the wrong in the case of the young car thief, it did not provoke much comment around the state.

Neither side in the lawsuit wants to talk about the award. The City Council may have treated it as a nuisance settlement recommended by the city's insurer to avoid the risk that a judge or jury, sympathizing with the boy's survivors despite the facts, might produce an adverse verdict and a larger award.

But the officer who shot the boy had been fully vindicated by a state's attorney's investigation that, incidentally, showed that the boy's supporters, trying to provoke outrage, repeatedly lied when they claimed that the car the boy was driving was not stolen as police said it was.

Until recently Connecticut had been failing to exact the necessary accountability from its police officers. New law establishes the office of inspector general to investigate police use of force, curtails the immunity of officers from lawsuits, and prevents the state police from concealing complaints of misconduct. The new law is said to be demoralizing police, but then any greater accountability would. Accountability in government is a necessity and must take precedence over employee morale.

But the settlement of the lawsuit in Bridgeport was not a necessity but a convenience, an excuse for the city not to support its police when they are in the right and an excuse for government not to demand accountability from wrongdoers.

Jayson Negron became a danger to the public because his family catastrophically failed him. Now they're getting rich at public expense, some people will call it justice, and, in this age of political correctness, no one in authority will dare to contradict them.

The "justice for Jayson" for which the boy's defenders clamor would have been decent parents.

WHITHER COLUMBUS?

But there is also plenty of lawlessness on the official level in Bridgeport.

For two years Mayor Joe Ganim has been expropriating the statue of Christopher Columbus that stood at Seaside Park in the city, though, according to the city's legal department, the city's Parks Commission, which has been protesting the expropriation, is the statue's exclusive custodian.

It's not clear what the mayor wants to do with the statue. First he had it placed in a barn at the park and lately had it moved to an Italian social club.

Of course, the mayor may worry that the statue risks vandalism if it remains in a public place, just as Columbus statues in Waterbury and elsewhere have been vandalized by people who consider him an agent of brutal Spanish imperialism more than a daring and world-changing explorer. (Strange that the people who are so upset with Columbus that they vandalize his statues don't seem to have vandalized anything, or even protested, in regard to their own country's recent imperial adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan.)

In any case the Columbus statue in Bridgeport is for the Parks Commission to dispose. Expropriating and hiding it just avoids the decision that needs to be made in the open by the responsible agency.

The statue's expropriation also adds to Mayor Ganim's sorry record of lawbreaking.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

An economic-mobility hub

The spectacular fare lobby of the Alewife MBTA station. The station is also known for its art works, inside and out. See photo at bottom.

— Photo by Eric Kilby

Edited from a New England Council report (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Rockland Trust Bank, based in Rockland, Mass., has announced a grant of $50,000 to Just A Start. The grant will be used to help support Just A Start, a new economic-mobility hub near the Alewife MBTA station, in North Cambridge.

“The new Economic Mobility Hub will be a 70,000-square-foot, mixed-use project. The goal of the project is to create a thriving and equitable community to accelerate economic mobility. Once completed the building will include 24 affordable apartments, four pre-school classrooms and a 19,000-square-foot training center. This new home for Just A Start will offer workshops and other programming to serve 2,800 people in Cambridge and Metro-North communities. The project will be open in April 2024.

“Andrea Borowiecki, Vice President of Charitable Giving and Community Engagement at Rockland Trust, said, ‘Our Charitable Foundation is honored to contribute to the development of this important project for the Greater Boston communities. The project perfectly aligns with what Rockland Trust as a community-orientated bank believes in, by providing resources to our neighbors that enable them to flourish to their full potential.”’

“Alewife Cows,’’ by Joel Janowitz

Sculpture outside the Alewife station by Toshihiro Katayama

Photo by Pi.1415926535

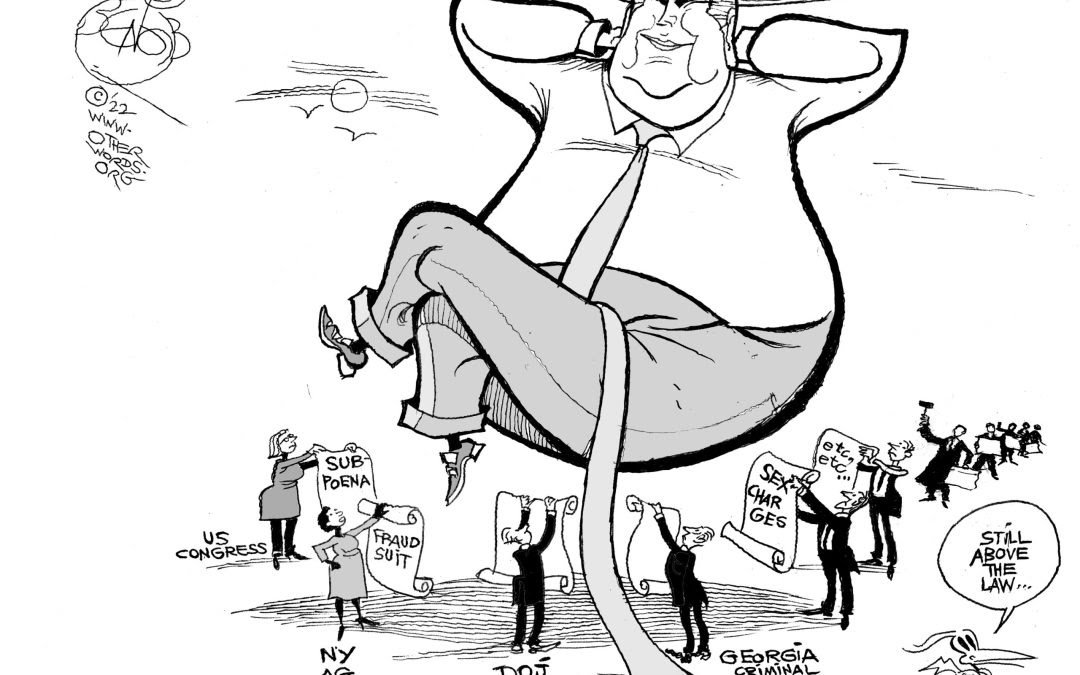

Jim Hightower: The asset strippers destroying local newspapers

Via OtherWords.org

Editor’s note: Gannett owns many New England newspapers, including The Providence Journal and The Worcester Telegram.

My newspaper died.

Well, technically it still appears. But it has no life, no news, and barely a pulse. It’s a mere semblance of a real paper, one of the hundreds of local journalism zombies staggering along in cities and towns that had long relied on them.

Each one has a bare number of subscribers keeping it going, mostly longtime readers like me clinging to a memory of what used to be and a flickering hope that, surely, the thing won’t get worse. Then it does.

Our papers are getting worse at a time we desperately need them to get better. Why? Because they are no longer mediums of journalism, civic purpose, or local identity.

Rather, they’ve been reduced to little more than profit siphons, steadily piping local money to a handful of distant, high-finance syndicates that have bought out our hometown journals. My daily, the Austin American-Statesman, was swallowed up in 2019 by the nationwide Gannett chain, becoming one of more than 1,000 local papers that Gannett mass produces under its corporate banner, “the USA Today Network.”

But even that reference is a deception. The publication doesn’t confide to readers that it’s actually a product of SoftBank Group, a multibillion-dollar Japanese financial consortium that owns and controls Gannett.

SoftBank has no interest in Austin as a place, a community, or even as a newspaper market, nor does it care one whit about advancing the principles of journalism. It’s in the profit business, extracting maximum short-term payouts from the properties it owns.

This has rapidly become the standard business model for American newspapering. Today, more than half of all daily papers in America are in the grip of just 10 of these money syndicates. That’s why our “local” papers are dying.

It’s not a failure of journalism. It’s a plunder of journalism by absentee corporate owners.

Linda Gasparello: Letter from Bonny and eerie Edinburgh

A woman waiting for a bus on Princes Street in Edinburgh on a moonless October night.

— Photos by Linda Gasparello

I play a silly game of characterizing cities as things. Here’s how it goes: If London were a holiday, which one would it be? My answer -- no doubt influenced by Charles Dickens -- is Christmas. Paris is New Year’s, because I’ve spent a few memorable ones there, feasting, drinking bubbly and giving cheek kisses.

Halloween? New Orleans, with its haunted French Quarter houses, voodoo and vampire lore, is my pick. But Edinburgh can give The Big Easy a run for its money as I noted when my husband and I visited the Scottish earlier this month.

In fact, Edinburgh has just been named one of the top three creepiest cities in the United Kingdom by Skiddle, an events-discovery platform, based on the combined number of reported hauntings and Halloween-themed events. According to Skiddle, bookings of ghost tours are way up in London and Brighton, which take the top two places in its survey, and Edinburgh.

Greyfriars Kirkyard

A terror-tour favorite in Edinburgh, Greyfriars Kirkyard, a church cemetery established in the mid-16th Century, is a one-stop shop of horrors, replete with ghosts, ghouls and bodysnatching.

I would’ve thought that the British tourists would’ve been spooked enough by the economic ghosts of 1979 -- a stagnant economy, surging inflation and waves of industrial unrest, trounced by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s free-market policies in the following years.

A couple with Halloween-colored hair celebrating at The Deacon Brodie's Tavern in the Lawnmarket.

Prime Minister Liz Truss, who resigned amid the Tory turmoil, was no ghostbuster.

Yes! We Have No Newspapers

There is a newsagent on Princes Street, near the Apex Waterloo Place Hotel. Above the door hangs a sign for The Scotsman, the Edinburgh daily, flanked by two smaller signs for other city newspapers: The Evening News, and the Daily Record and Sunday Mail.

My husband and I stopped in to buy some newspapers, keen to read the coverage of the Scottish National Party Conference. But we found none there.

Yes, they had Fyffes bananas, and the shelves were stacked nearly to the ceiling with boxes of “sweet biscuits” and shortbread, especially the shiny red tartan boxes of Walkers Shortbread, advertised on the shelf as the “Walkers Pure Butter Luxury Shortbread Top Quality All Size Box 3.99 p.”

I walked up to the cashier, a young man of South Asian origin, and asked if he sold newspapers. He said he gave up selling them because he didn’t want to deal with the “all the paperwork and returns for a few pence on a sale.”

Anyway, he adamantly said, “Nobody ever needs to read newspapers. They have nothing in them, only opinions.”

Surely, I said, there’s a newsagent in the vicinity that sells newspapers. Somewhat grudgingly, he told me to go to the WHSmith shop in the train station.

I left the no-news newsagent and walked to the station. I bought 15 pounds (about $17) worth of newspapers at the WHSmith because I’m a big-spending nobody

Sir Jim, ‘The Bonnie Baker’

I read in The Herald that Walkers Shortbread’s profits had more than doubled to 62 million pounds (about $69.2 million) this year, boosted by strong demand in key markets.

In the late 1980s, when I was the editor of a global food-industry paper, I interviewed Jim Walker, head of the family-owned baking company, which was founded by Joseph Walker in 1898. In my story about Walkers, I dubbed him “The Bonnie Baker.” He is now Sir Jim, having received his knighthood in the late Queen’s Birthday Honors earlier this year.

Walker told The Herald that it had been “a very, very difficult couple of years” due to COVID and supply problems. “Butter has virtually doubled (in price), and the price of flour has gone up as well,” he said.

Butter was a problem for Walker in the late 1980s, but for quite a different reason.

In the U.S. cookies market, where Walkers wanted more penetration, it was a bad time for butter. Spurred by food activists, such as the Center for Science in the Public Interest, consumers were demanding that cookie makers eliminate highly saturated fats, from butter to palm oil, in their products.

On a visit to the company’s headquarters, in Abelour, in The Highlands, during that saturated fat-cutting time, I offered Walker this advice: Find a healthy butter substitute.

“No, we can’t,” he said firmly. “Butter is one of four shortbread ingredients.”

I offered him another pat of advice: Extend the brand’s product line with chocolate-chip shortbread.

This was probably already in the works, but I’d like to think that I was responsible for Walkers adding another ingredient -- and going on to become the largest British exporter of shortbread and cookies to the U.S. market.

Buchanan Fish Fight

The Buchanan clan has its first new chief in more than 340 years.

“The last Buchanan chief, John Buchanan, died in 1681 without a male heir. Identifying the new chief required decades of genealogical research conducted by renowned genealogist, the late Hugh Peskett,” according to History Scotland, a Scottish heritage Web site.

John Michael Ballie-Hamilton Buchanan was inaugurated Oct. 8 in a ceremony in Cambusmore, Callander, the modern seat of Clan Buchanan and the chief’s ancestral home. International representatives of the clan’s diaspora – from North America (count conservative commentator Patrick J. Buchanan) to New Zealand -- celebrated alongside the chiefs and other representatives of 10 ancient Scottish clans, History Scotland reported.

“Speaking before the inauguration, Lady Buchanan said they expected many neighboring clans to attend – despite, in some cases, a long history of rancor,” The Daily Telegraph’s Olivia Rudgard wrote.

“ ‘Spats’’ involving the Buchanan clan include a 15th Century feud with Clan MacLaren, apparently started at a fair when a Buchanan man slapped a member of the MacLaren clan with a salmon and knocked his hat off his head.

“It ended in a bloody skirmish which killed, among others, one of the sons of the MacLaren chief,” Rudgard wrote.

With apologies to Robert Burns, a Scot’s a Scot, for a’ that -- and Scotland is a bonny place to visit.

Linda Gasparello, based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., is producer and co-host of White House Chronicle, on PBS

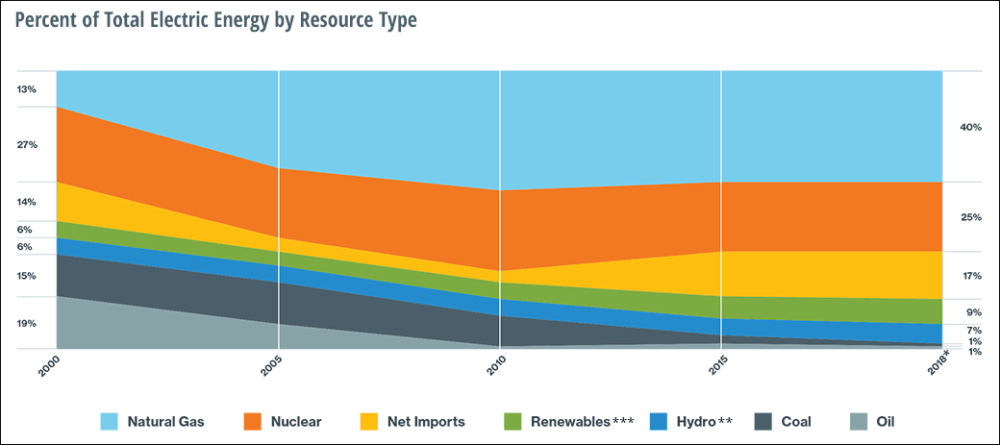

Llewellyn King: Utilities face more demand, less generation

How New England's energy mix has changed since 2000 -- before the closure of the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant, on the coastline in Plymouth, Mass., which was shut in 2019.

— — Courtesy of ISO New England

The Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant, with the Manomet Hills behind.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

America’s electric utilities are facing revolutionary changes as big as any they have faced since Thomas Edison got the whole thing going in 1882.

Between now and 2050 – just 28 years -- practically everything must change: The goal is to reach net zero, the stage at which the utilities stop putting greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere.

But in that same timeframe, the demand for electricity is expected to at least double and, according to some surveys, to exceed doubling as electric vehicles replace fossil-fueled vehicles and as other industries, such as cement and steel manufacturing, along with general manufacturing, go electric.

Just eliminating fossil fuel alone is a tall order -- 22 percent of the current generating mix is coal, and 38 percent is natural gas. Half of the generation will, in theory, go offline while demand for electricity soars.

The industry is resolutely struggling with this dilemma while a few, sotto voce, wonder how it can be achieved.

True, there are some exciting technological options coming along: hydrogen, ocean currents, small modular nuclear reactors, so-called long-drawdown batteries, and carbon capture, storage and utilization. The question is whether any of these will be ready to be deployed on a scale that will make a difference by the target date of 2050.

There are other schemes -- still just schemes -- to use the new electrified transportation fleets as a giant national battery. The idea is that your electric vehicle will be charged at night, or at other times when there is an abundance of power, and that you will sell the power back to the utility for the evening peak, when we all fire up our homes and electricity demand zooms.

This is just an idea and no structure for this partnership between consumer and utility exists, nor is there any idea of how the customer will be compensated for helping the utility in its hours of need. It is hard to see how there will be enough money in the transaction to cause people to want to help the utility because besides the cost of charging their vehicles, the batteries will deteriorate faster.

The ongoing digitization of utilities means that they will be able to better manage their flows and to practice more of what is called distributed energy resources (DER), which can include such things as interrupting certain nonessential users by agreement.

David Naylor, president of Rayburn Electric Cooperative, bordering Dallas, says that DER will save him as much as 10 percent of Rayburn’s output, but not enough to take care of the escalating demand.

Like many utilities, Rayburn is bracing for the future, expecting to burn more natural gas and add solar as fast as possible. They are also upgrading their lines, called connectors, to carry more electricity.

The latter highlights another major challenge for utilities: transmission.

The West generates plenty of renewable power electricity during the day, some of which goes to waste because it is available when it isn’t needed in the region, but when it would be a boon in the East.

The simple solution is to build more long-distance transmission. Forget about it. To get the many state and local authorizations and to overcome the not-in-my-backyard crowd, most judge, wouldn’t be possible.

Instead, utilities are looking to buttress the grid and move power over a stronger grid. In fact, there isn’t one grid but three: Eastern, Western and the anomalous Texas grid, ERCOT, which is confined to that state and, by design, poorly connected to the other two, although that may change.

Advocates of this strengthening of the grid abound. The federal government is on board with major funding. Shorter new lines between strong and weak spots would go a long way to making the movement of electricity across the nation easier. They would also move the nation nearer to a truly national grid. But even building short electric connections of a few hundred miles is a fraught business.

The task of the utilities -- there are just over 3,000 of them, mostly small -- is going to be to change totally while retooling without shutting off the power. The car companies are totally changing, too. But they can shut down to retool. Not so the utilities. Theirs must be revolution without disruption: the light that doesn’t fail.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Julia Child: ‘Never apologize’

Julia Child in her kitchen in Cambridge in 1978, in a publicity shot.

“The only time to eat diet food is while you’re waiting for the steak to cook.’’

“No matter what happens in the kitchen, never apologize.”

“People who love to eat are always the best people”

“Always remember: If you’re alone in the kitchen and you drop the lamb, you can always just pick it up. Who’s going to know?”

“You learn to cook so you don’t have to be a slave to recipes.”

— Famous lines by Julia Child (1912-2004), TV food-show star (via WGBH, in Boston, where she was the star of The French Chef), author, teacher, semi-comedian and in World War II a quasi-spy with the OSS. She lived in Cambridge, Mass., for 40 years and was a big character in many ways.

‘Every leaf, rock and tree’

“Protector” (detail), (alabaster, wonderstone, pine needles), by Robin MacDonald-Foley, in her show “The Forest Voice,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 4-27.

She tells the gallery:

"Inspired by ancestral history, ‘The Forest Voice’ reflects my journey, communicated through sculptural figures, bowl-like vessels, and woodland photographs. Every leaf, rock and tree, becomes part of the dialogue. Exploring my family’s shared places, those I know and some I’ve yet to experience, I’m recreating events through the mystery and folklore of the forest. To those who sheltered and foraged, with hope and fortitude, my stories are offerings of love, light and guidance. May you always find your way."

Even fairly small towns in Greater Boston had streetcars back in 1912, when this photo was taken.

Proud of their maze; more knowledge for the knowledgeable?

Already a maze in 1775.

Near Boston City Hall after the Blizzard of ‘78,

“Boston

”Rich with historical facts

Where the city is a maze

And the snow get stacked.

”Yeah, we got hit

And we felt the impact

But we respond first

And yes, we bounce back.’’

— From the 2013 song “Boston Strong,” by Mr. Lif (born 1977), written in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombing, which happened on April 15, 2013.

xxx

“The Boston people were willing to learn, but only if one recognized how much they knew already.”

— Van Wyck Brooks (1886-1963), American literary critic, historian and biographer

The permanent doesn’t exist

“Ephemerality” (mixed media), by Dawn Surratt, in the group show “The Morphing Medium,’’ at the Maine Museum of Photographic Arts, Portland, through Dec. 3

—Photo courtesy Maine Museum of Photographic Arts.

The museum says:

“This expansive show contains the work of 18 artists who work in the medium of photography. But this is anything but your standard photography show. Artists use the full breadth of what the medium has to offer, pushing the boundaries of technique, material and composition.’’

Gun recovered from the USS Maine on Munjoy Hill, in Portland. The explosion that sank the ship in Havana Harbor on Feb. 15, 1898 was a catalyst for the United States to launch its war against Spain. However, no one has proven what caused the explosion.

— Photo by Ryssby

Felice Duffy: Forward or backward with new Title IX regs?

— Photo by Sichow

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

NEW HAVEN, Conn.

On the 50th anniversary of the enactment of Title IX, the U.S. Department of Education released proposed new regulations for Title IX policies. For the most part, these new regulations reverse regulatory changes made during the Trump administration.

The Biden administration insists the new regs will “restore crucial protections” that had been “weakened.” Commenters have their own opinion on the efficacy of the proposed regulations, with over 235,000 formal comments filed during the 60-day comment period.

So, do the proposed regulations represent a step forward or backward?

Overview of changes

The deceptively simple words in Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 have been augmented by numerous regulations and judicial interpretations over the decades. While the aim is to protect students from sex-based discrimination, many worry that the regulatory efforts to right or prevent wrongs go too far and infringe on the due process rights of those accused of Title IX violations.

During the Trump administration, the Office for Civil Rights spent nearly 18 months reviewing less than 125,000 public comments before issuing new final regulations that resulted in significant changes. With almost 90% more comments to review this time around, it will be interesting to see how long it takes the department to issue final rules about key issues they are considering, such as:

How colleges are required to investigate reports of sexual assault.

Whether colleges are required to hold live hearings before issuing decisions.

Protections for LGBTQIA+ students.

The definition of sexual harassment.

While some commenters object that the proposed rule changes go too far in one direction, others insist they do not go far enough.

Live hearings and cross-examination

One of the most significant controversies regarding the proposed regulations centers on the types of proceedings colleges must hold to hear Title IX complaints. The new regulations allow schools to hold separate private meetings with complainants and respondents instead of live hearings with the opportunity for cross-examinations. Supporters of the change assert that the disciplinary hearings required under current rules are too much like adversarial courtroom proceedings. Many say that allowing colleges to establish less formal, non-confrontational processes will save money and encourage victims to proceed without fear of repercussions.

However, other commenters expressed concerns that eliminating live hearings and allowing colleges to use the same body to investigate and judge the validity of complaints violates the due process rights of students accused of violations.

Burden of proof in sex discrimination and misconduct

Controversy continues about how much a complainant must prove to win a case alleging that they have been subjected to sexual discrimination, harassment or assault. The proposed rules would generally establish a “preponderance of evidence” standard in most but not all cases, so a student need only to prove that it was “more likely than not” that the discrimination occurred. The current rules provide a choice between the preponderance of evidence and clear and convincing evidence standards.

Critics of the change say the clear and convincing standard is necessary to protect the respondent’s rights, and they point out that it is still less than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard used in criminal cases.

Gender identity and sexual orientation

The proposed regulations expand the anti-discrimination protections of Title IX to include gender identity and sexual orientation when it comes to college programs or activities, except athletics. The department has delayed ruling on the highly controversial issues related to participation in sports programs.

Even without addressing athletics, the expansion of protections generated numerous forceful comments. Those in favor assert that the new rules will improve the safety and wellbeing of LGBTQIA+ students and resolve equality issues that are currently being addressed on a costly case-by-case basis in the courts. Opponents of the expansion allege that by requiring schools to allow participation in programs based on gender identity, the new regulations actually violate the Title IX mission of providing equal access to education benefits on the basis of sex. They also argue that the proposed changes exceed the department’s statutory authority and would chill free speech rights on campus. For example, the definition of sexual harassment will be expanded such that students could be investigated for not using certain pronouns or using incorrect pronouns that do not correctly reflect the gender with which a person identifies.

Are we moving forward or backward?

While the new regulations are not yet final, the final regs are expected to track closely with the proposed version. Whether you are a complainant or a respondent regarding any number of explicit proposed provisions in the regulations, each side would argue the provision is either moving toward a brighter future or repressive past—any provision that makes it more difficult to file a complaint (such as requiring a formal complaint under the current regs) makes it harder for complainants (repressive past) and easier for respondents (brighter future); and keeping the standard at the preponderance of evidence versus raising it to clear and convincing, is easier for complainants (repressive past) and more difficult for respondents (brighter future).

The one certainty is that when schools implement the new regulations, those who are unhappy with the results will turn to the courts for clarification and possible nullification. It will be interesting to see how the courts respond.

Felice Duffy is a Title IX lawyer with Duffy Law, based in New Haven, Conn., and a former federal prosecutor.

David Warsh: The arduous advance of economics as seen through Nobel prizes

The Nobel Prize in Economics committee took note about this famed film, which revolves around a local banking crisis in The Great Depression.

STOCKHOLM

Eight economists have received invitations to Stockholm in December, three of them living, five of them dead. Three will show up, to accept their Nobel Memorial Prizes in the Economic Sciences. The five Spirits summoned, all but one laureates themselves, are still teaching, though only as textbook legends. A sixth Specter, significant to the story, did not make the list. He died in 2018.

Ben Bernanke, an applied economist who gradually became a central banker, and theorists Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig, who remained university professors for forty years, were recognized last week for two particular papers about banking and financial crises they wrote in 1983

“Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance and Liquidity,” by Diamond and Dybvig, in the Journal of Political Economy; and “Nonmonetary effects of the financial crisis in the propagation of the Great Depression,” by Bernanke, in the American Economic Review, were the only the first statements of the problems on which they intended to work. Many other technical papers followed, at first by the authors themselves, then by members of growing community of fellow-researchers determined to extend the boundaries of the field.

Neither of those first two papers settled anything. Together, however, they announced research projects that constituted “discoveries,” in the language of the citation, which, in the course of time, and in combination with the insights of many others, “improved how society deals with financial crises” – a key condition of many Nobel Foundation economics prize.

How? By demonstrating to a new generation of researchers how to approach exploring the previously uncharted territory of “financial intermediation,’’ meaning the operations of the institutions that occupied the larges space between two well-established regions: Keynesian macroeconomics, and its preoccupation with business cycles; and “monetarism,” a somewhat old-time fascination with the history and theory of money and banking.

In other words, this year’s prize recognizing the financial macroeconomics that has begun to emerge like a new textbook chapter from the void is more rhetorically powerful than it seemed, at least in the course of the usual show-business ceremony with which the prize was announced Oct. 10.

A 72-page essay on the scientific background of the award spelled out the story for those with the curiosity and patience to read. It tells a story of how economics makes progress: one generation of economists feasts on the glory of another. That is, newcomers to the discipline supplant one source of excitement with another. In this case, the new excitement arrived just in time.

. xxx

From the very beginning of their modern science, in the 18th Century, the background citation asserts, economists were well aware of the existence and nature of banks, of course. David Hume and Adam Smith were well aware of how bankers took deposits and then extended much more credit than the cash reserve they kept in the till. Hume and Smith knew all about the panics that regularly occurred when all the depositors wanted their money back at the same time. (The long Nobel citation mentions the Frank Capra movie, It’s a Wonderful Life.) Smith reasoned that free competition among banks would solve the problem, as long as lenders were prudent and followed the “real bills” rule.

During the 19th Century, economists mostly left the discussion of banks to bankers (Henry Thornton) and journalists (Walter Bagehot) while they worked on the problems of supply and demand that they cared about most. What they called “general equilibrium theory” emerged. Only in 1888 did the pioneering mathematical economist and statistician Francis Ysidro Edgework construct the first model of fractional banking.

Fast forward to the years after World War II, when economists began to write much more in mathematics instead of natural language, the better to be clearer among themselves. The ramifications of competition gradually became clear by formally modeling it as though it were perfect. And the first major payoff of mathematical language was the discovery that, at least in some important ways, everyday competition definitely wasn’t perfect. A model of monopolistic competition had emerged in the 1930s, a little too early for the Nobel Committee to take note of it; the first economics prize wasn’t given until 1969. Meanwhile, banking, whatever it was, remained the business of bankers.

In the 1970s, a significant part of the excitement in mainstream economics had to do with something called the Modigliani-Miller theorem. The authors, Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, had met in the 1950s as colleagues at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh. In 1958 they agreed to teach a course in corporate finance in the business school there. What emerged was what Peter Bernstein, in Capital Ideas, The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street (1992), called “the bombshell assertion.” This was the proposition that, thanks to the principle of arbitrage, the ratio of debt to equity in a firm’s capital structure didn’t matter; Under perfect competition, in the absence of frictions and asymmetries of all sorts, no matter how the firm was financed, the enterprise value of the firm would be the same.

Enter financier Michael Milken, who in the 1970s pioneered modern high-yield (“junk”) bonds. Soon the debt-based restructuring takeover boom of the 1980s was underway. Modigliani was recognized in 1985 by the Nobel Committee “for his pioneering studies of savings and financial markets.” Five years later, Miller shared the prize with two other pioneers in finance for, in his case, his collaboration with Modigliani on the article “The Cost of Capital, Corporate Finance and the Theory of Investment.”

It was amid this commotion that the situation arose in which Diamond and Dybvig took up their challenge. Many banks in the 1980s were large and ubiquitous around the world, and enormously profitable. But why did they exist at all? In 1980, the author of one survey of the literature on banking stated: “There exist a number of rival models and approaches which have not yet been forged together to form a coherent, unified and generally accepted theory of bank behavior.”

Diamond and Dybvig did just that, according to the citation, offering two critical insights in the process. There were “fundamental reasons why bank loans are a dominant source of financing in the economy” for one thing, and “for why banks are funded by short-term, demandable debt.” For another, that meant that “banks are inherently fragile and thus subject to runs.”

. xxx

Bernanke approached the problem of financial intermediation from a different direction – from curiosity about the mechanisms of business cycles characteristic of the Keynesian macroeconomics that he studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dale Jorgenson had been Bernanke’s adviser at Harvard College. Stanley Fischer supervised his dissertation, along with Rudiger Dornbusch and Robert Solow. He finished “Long-term commitments, dynamic optimization, and the business cycle” in 1979 and took a job at Stanford University.

As the Nobel citation puts it:

“The dominant explanation at the time for why the Great Depression was so deep and prolonged was due to Milton Friedman and his wife, Anna Schwartz (1963). They argued that the waves of banking crises in 1930–1933 substantially reduced the money supply and the money multiplier. The failure of the Fed to offset this decline in money supply in turn led to deflation and a contraction in economic activity.’’

Friedman had moved from Chicago to San Francisco, where he taught part-time at nearby Stanford. There was not much other than traditional money and banking in A Monetary History of the United States, by Friedman and Schwartz, The citation continues,

Bernanke (1983) proposed a new (and in his view complementary) explanation of why the financial crisis affected output. According to this view, the services that the financial intermediation sector provides, including “nontrivial market-making and information gathering,” are crucial for connecting lenders to borrowers. The bank failures of 1930–1933 hampered the financial sector’s ability to perform these services, resulting in an increase in the real costs of intermediation. Consequently, borrowers – particularly households, farmers and small businesses – found credit to be expensive or unavailable, which had a prolonged negative effect on aggregate demand. Bernanke combines examination of historical sources, statistical analysis, and (at the time) recent theoretical insights to build this argument.

The lingering controversy between Keynesians and monetarists persists even today – about the cause, length, and depths of the Great Depression – was it the result of bad monetary policy carried out by the Federal Reserve Board in the United States, according to Friedman, or the outcome a worldwide series of accidents dating from World War I, in MIT’s Paul Samuelson’s view?

The citation states:

“To be clear, Bernanke’s analysis does not engage in the discussion of what caused the initial economic downturn in the late 1920s that subsequently escalated into the Great Depression, and this was not the focus of Friedman and Schwartz either. Similarly, when we discuss the Great Recession below, the core issue is not about its origins but on the mechanisms by which the recession played out.’’

Whatever the case, though, Bernanke stated his own view when, in 2002, in an important speech as a governor of the Fed at a celebration for Friedman’s 90th birthday, he concluded:

“Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

The citation, however, sticks to what happened in 1983:

“From the perspective of the contributions by Diamond and Dybvig, Bernanke’s work can be seen as providing evidence supporting their models. Specifically, he provides evidence that bank runs can lead to financial crises (as in Diamond and Dybvig, 1983), which in turn leads to prolonged periods of disruption of credit intermediation, consistent with bank failures destroying the valuable screening and monitoring services banks perform (as in Diamond, 1984).’’

Thus the guest list for this year’s prize celebration includes Bernanke, Diamond and Dybvig. Perhaps the authorities will find a seat as well for Stanley Fischer, former president of the Bank of Israel. But the honored ghosts whose earlier work the three displaced will be present as well: Modigliani and Miller; Samuelson, Friedman and Anna Schwartz, Only Dr. Schwartz failed to receive the ultimate diploma, but then the centrality of A Monetary History was not yet apparent in 1976, neither was the extent of her contribution to it, when Friedman received his prize.

As for what happened in 2008, the prize citation has nothing to say. Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip noted that “Outside of a footnote, the committee managed to ignore Mr. Bernanke’s central role in responding to that crisis.’’ The Swedes chose to tell the story from its beginning, instead of its end. What, then, did we learn from the 2008 crisis? We’ll have to wait a little longer for that prize.

Meanwhile, what about that sixth Specter, the uninvited guest at the banquet?

That would be Martin Shubik, of Yale University, a long-time player in the Nobel nomination-league, who supervised both Diamond and Dybvig in their graduate studies. Shubik himself had worked, for a dozen years without conspicuous success, on the more forbidding problem of integrating the production of money and banking into the market system Not long before he died, he believed he had solved it. A paperback edition of (2016), with Eric Smith, appears next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com.

Fast trash spreaders

Delicious way to boost your blood sugar but where will you put the bag?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s usually a debate in this or that community around here about whether to let such chain fast-food establishments as Canton, Mass.-based Dunkin’ Donuts open stores there. I’m sympathetic to those residents who want to keep them out.

Of course, one reason to oppose them is that they tend to drive some locally based businesses out of business.

Another is that they are serious outdoor-trash spawners. I’m not sure if Dunkin’ Donuts customers are bigger slobs than the rest of us, but their coffee cups, lids, bags and so on are all over the place and have been at a generally increasing rate since the company’s founding, in 1948.