Beatific about Boston

“Here’s the thing about Red Sox fans, or actually just fans from that region, in general: they appreciate the effort. And if you mail it in or if you give 80 percent, even with a win, they’ll let you know that’s not how you do it. They want – if it’s comedian, if it’s a musician, bring us your best show.”

— Dane Cook (born 1972), American comedian

“For no matter how they might want to ignore it, there was an excellence about this city (Boston), an air of reason, a feeling for beauty, a memory of something very good, and perhaps a reminiscence of the vast aspiration of man which could never entirely vanish.”

-- Arona McHugh (1925-1996), American writer

Steeple of the Old South Meeting House (built in 1729).

“Here {Boston} were held the town-meetings that ushered in the Revolution; Here Samuel Adams, James Otis and Joseph Warren exhorted; Here the men of Boston proved themselves independent, courageous freemen, worthy to raise issues which were to concern the liberty and happiness of millions yet unborn.” —sign at the entrance of the Old South Meeting House, author unknown

“Its driving energy sparked always by independence and freedom of the spirit — can this be anywhere so strong, so fascinating, so enduring as in Massachusetts?”

— Pearl S. Buck (1892-1973), Nobel Prize-winning novelist

‘Flames’

— Photo by DigbyDalton

“Cardinals at the windows see enemy

black and white newspapers turn to color

reflections or crimson hills or horses

for added effect. There’s lots of red now, flames….”

— From “Coups de Coeur (Wounds to the Heart),’’ by Pat Frisella, a Farmington, N.H.-based poet

The Thayer and Osborn shoe factory in Farmington in 1915. The town was once a major shoemaking center.

Ready for a fight

“Costume Design” (1924) (graphite and gouache on paper), by Alexandra Exter, in the show “Time and Tide Flow Wide: The Collection in Context, 1959-1973,’’ at the Colby Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine. The exhibition celebrates the early years of the museum.

Llewellyn King: Adieu the Queen — We mourn together all those years as memories of empire are laid to rest

Notice at Holyrood Palace, in Edinburgh on Sept. 8. The building is the official residence of British monarchs in Scotland.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have a feeling that with the burial of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II at Windsor Castle a gallant and dutiful monarch has been laid to rest, but so has an empire. And millions have been given license to weep for her and for ourselves.

The British summoned up centuries of history in a show of pageantry that none of us will see again -- and which, in truth, may never be seen again.

It was, if you will, the spectacular to end all spectaculars.

The British buried their longest-serving monarch and, I think, they also buried memories of empire, and of a time when ceremony was part of the art of governance.

I was born into that empire in a British colony, Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, and was brought up in its traditions, and with the expectation that it would last forever. When the Queen acceded to the throne, in 1952, it was seen in the colonies as a new beginning — that somehow Britain would rise again — that there would be another grand Elizabethan period recalling the one that began in 1533.

When the Queen was crowned, India had already gained independence, in 1947, but we still clung to what Winston Churchill said in 1942, “I have not become the King’s first minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.”

But that was coming. The forces of democracy and, more so, the forces of self-determination were at work in what Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was to describe, in his epic 1960 speech to the South African Parliament, as a “wind of change.”

That wind blew steadily until the British Empire was indeed liquidated and had been replaced by the loose, fraternal Commonwealth. The empire had dribbled away. The Union flag came down, and new flags went up from Burma to Malawi.

In Britain itself the shrinking of its global reach was hardly marked, as life changed, and other struggles occupied the nation.

The Queen’s funeral was, with its extraordinary pageantry, a reminder of the past, and a reminder that it, indeed, is past.

Most of those among the extraordinary throng that sought to enter Westminster Abbey were, at best, only subliminally aware of the farewell to much of British history.

Throughout the Queen’s lying-in-state, there has been another force at work.

I believe that when we have these occasions to weep, we weep for ourselves, for all our hurts and failures, and for all the pain of the world. When FDR died, when Churchill died, when John Lennon was shot, when Diana, Princess of Wales was killed in a car crash, when Nelson Mandela died, the world wept then as now.

Public ritual is public healing, and Queen’s state funeral -- the first one since the death of Churchill, in 1965 -- was a way for us to cry for the myriad hurts in our own lives and across the human condition.

When you can hug a stranger and shed a tear, one is connected to all of humanity in a way that transcends class and race, religion, and wealth and poverty. Briefly, we are one, seemingly in grief for a remarkable monarch, but also in grief for ourselves.

There is an expression that one used to hear in Britain, and may still do, “It does one good to have a good cry.”

The world has had a good cry, thanks to an august queen, who died at 96, after presiding over a dwindling empire and a surging affection, over a very human and often dysfunctional family, and who smiled through, carrying her nation and the world with her.

Her final act was to let the world cry for itself, as much as for her. Well played, ma’am. Now rest in peace.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com ,and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

One can believe a five-mile backup on the Mid-Cape Highway

Sandwich, Mass., Town Hall (1834) and Congregational Church (1848).

“One can believe anything on the Cape, a blessed relief from the doubts and uncertainties of the present-day turmoil of the outer world.’’

— Thornton Burgess (1874-1965), American conservationist and children’s book author in Now I Remember (1960). He was a native of Sandwich, on the north side of The Cape.

Sandwich was long famed for its glass-making industry, including the beauty of many of its products.

David Warsh: 3 cheers for Ukraine and 2 cheers for The West

SOMERVIILLE, Mass.

World opinion seems to have turned, pretty conclusively, against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A combination of Ukraine’s army’s success in defending its sovereignty, the Russian army’s flight from regions previously occupied, and Vladimir Putin’s reluctance to attempt to mobilize his populace for full war, have led China’s Xi Jinping and India’s Narendra Modi to publicly express reservations about his attempt to annex his neighbor.

Thus Moscow bureau chief Robyn Dixon said a couple of days ago in The Washington Post:

Putin and Xi each harbor resentments over past humiliations by the West. They dream of cutting the United States down to size, then taking what they see as their rightful places among several dominant world leaders. They are dictators, ruling “democracies” that lack any meaningful democratic features. And they both want to reshape global rules to suit themselves.

But Putin’s chaotic, tear-it-all-down approach, kicking down the territorial sovereignty of neighboring Ukraine and perpetrating the biggest land war in Europe since World War II, could not be more different from Xi’s careful, steady moves to bend global institutions to Chinese values.

The war has roiled global supply chains and set off global economic instability, impacting China, along with most of the world. It has irreparably harmed Putin’s reputation, exposed his country’s military weakness and triggered punishing sanctions, without producing a single notable benefit.

Columnist Janan Ganesh, in the Financial Times:

I don’t pretend that the average Westerner has read their Hume and Spinoza. I don’t even pretend they deal in such abstractions as “The West”. But there is a way of life – to do with personal autonomy – for which people have consistently endured hardship, up to and including a blood price. Believing otherwise is not just bad analysis. It leads to more conflict than might otherwise exist.

Kremlinologists report that Vladimir Putin saw the U.S. exit from Afghanistan last year as proof of Western dilettantism. From there, it was a short step to testing the will of the West in Ukraine. You would think that U.S. forces had rolled up to Kabul in 2001, poked around for an afternoon, deplored the lack of a Bed Bath & Beyond, and flounced off. They were there for 20 years. Whatever the mission was – technically inept, culturally uncomprehending – it wasn’t decadent.

How much carnage has this misperception of the west triggered? The [1930’s] Empire of Japan couldn’t believe the hermit republic that America then was, would send armed multitudes 5,000 miles away in response to one day of infamy. (And, remember, never leave.) The Kaiser in 1914 and Saddam Hussein in 1990 made similar assessments of the liberal temper. It is not out of vanity or machismo that The West should insist on recognition of its fighting spunk, then. It is to avert the fighting

Two cheers, then, for “The West.” The American republic is deeply divided, England a mess, Scotland on the verge of more devolution, the old British Commonwealth of Nations coming apart, NATO reduced as a moral force. Yet Ganesh is right; the global community of Western liberalism is here to stay. In its ongoing competition with Russia, China, and Iran, the Free World abides.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this columnist originated.

Colleen Cronin: The big potential of shellfish aquaculture

Live blue mussels on a rocky substrate

— Photo by Andreas Trepte

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The sound of thousands of mussels moving on conveyor belts and clanking through sorting machines almost drowned out Greg Silkes as he tried to explain how the shellfish get from the ocean, through the processing plant, to plates around North America.

Silkes is the general manager American Mussel Harvesters, one of the largest mussel producers in North America, and he helps run the business along with his father and other family members. On Wednesday, the Silkes and America’s Seafood Campaign hosted U.S. Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.), and other officials and seafood stakeholders at their location in North Kingstown, R.I., to discuss the shellfish-farming industry and its importance to public health, the economy, and reducing carbon emissions.

American Mussel Harvesters has been around since 1986 and has grown from a small operation with one boat and one phone to a large enterprise that ships mussels, clams, and oysters around the country.

Rather than fishing from pockets of naturally occurring shellfish on the seafloor, American Mussel Harvesters grow their product from tiny seeds in lots in the ocean. Greg Silkes said that a bag about the size of a shoe box can store millions of itty-bitty shellfish.

Overall, it takes about two to four years to get the shellfish from seed to table, but, depending on the maturity of the seeds American Mussel Harvesters buys, it usually takes six to eight months to grow and process their product and get it on the market.

As workers sorted the mussels into different grades, packed them into netted bags, and placed them in boxes filled with ice, Silkes said the shipment would be headed to a nearby Market Basket.

In the last two years the business model has shifted away from restaurants and toward retail because of the pandemic, Silkes said, and they’ve automated more of their processing plant to accommodate that change.

Still, American Mussel Harvesters does sell to local restaurants. “I love going to eat and saying this is my product,” Silkes said.

Later, on a boat specifically outfitted for shellfish harvesting, the group, which included several members of the Silkes family, Reed, and representatives from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), the Rhode Island Food Policy Council, and East Coast Shellfish Growers Association, sat down for a round table discussion about the industry.

Bill Silkes, the owner and founder of American Mussel Harvesters, started off the discussion thanking Reed for his work to promote shellfish farming in Rhode Island. “Under your watch,” Rhode Island’s gone from zero to more than 40 farms, Silkes told the senator.

Reed noted that it’s an important industry “not just to Rhode Island, but to the entire nation.”

According to the Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation, in R.I., the fisheries and seafood sector — which includes commercial fishing and shellfishing, fishing charters, processing, professional service firms, retail and wholesale seafood dealers — consists of 428 firms that generated 3,147 jobs and $538.33 million of gross sales in 2016. Including spillover effects across all sectors of the R.I. economy, the total economic impact was 4,381 jobs and an output of $419.83 million. The Port of Galilee alone hosts 240 fishermen that bring in 48 million pounds of seafood annually.

As the industry continues to grow, Bill Silkes said, a lack of dock space and growing space will impact local businesses. Indicating the vessel hosting the round-table talk, Silkes said it had already been kicked out of a slip once to accommodate a yacht.

He also noted efforts to start moving farming into federal waters, something that has made more progress in the last few months than in previous years.

“The opportunity is enormous,” he said.

Assistant administrator for NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Janet Coit said she’s been working to get aquaculture out of state waters and that part of the challenge is that permitting will involve several different groups.

Coit, the former DEM director, said she sees the “same issues” federally in getting farms up and running as there were in Rhode Island, “just at a different scale.”

Bob Ballou, assistant to the director of DEM, talked about RI Seafood, the state-run marketing campaign designed to get more Rhode Islanders eating local catch.

Ballou said the campaign not only supports the seafood industry, it also provides economic, public health, food security, and environmental benefits in a “win-win-win-win-win” situation.

Seafood produces six times less than the carbon emissions of beef, said Diane Lynch, president of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council, so shifting protein consumption toward foods like shellfish and away from cattle could help to mitigate the effects of climate change.

“We’re just slowing [climate change] down, it’s too late to stop… but we have to do much, much more,” Reed said, adding that the seafood industry is “much kinder to the environment than some other folks.”

Linda Cornish, president of the Seafood Nutrition Partnership, added that on top of the other benefits, seafood is a valuable nutritional resource and may contribute positively to mental health.

At the end of the discussion, Mason Silkes brought out fresh oysters and showed Reed how to shuck them while the group slurped them down.

Colleen Cronin is a Report for America corps member who writes about environmental issues in rural Rhode Island for ecoRI News.

Chris Powell: Why not just take him to Rikers now?

Rikers Island from above.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

If distributing more money was the solution to the state's serious social problems, Connecticut would have solved them long ago. Instead state government now has another commission, the Commission on Community Gun Violence Intervention and Prevention, which met for the first time last month and is to advise the state Public Health Department about awarding another $2.9 million in grants to "community-based violence-intervention organizations."

Despite last month's announcement from Gov. Ned Lamont's re-election campaign that Connecticut is headed toward "four more years of gun safety," the daily shootings continue, especially in the cities. Except for the political patronage to be conferred by those grants, no one really needs "community-based violence-intervention organizations" to figure out why.

For starters, most children in the cities have little if any parenting. More than 80 percent are living without a father in their home, many having no contact with their fathers at all. Many of their mothers are badly stressed by single parenting and trying to make a living, even with welfare benefits. Some have drug problems. Some are so addled that their children are being raised by a grandparent.

Their parents having failed them, many children then fail in school, if they even reach school. The chronic absenteeism rate in Hartford's school system is 44 percent, in New Haven's 58 percent. It is high in some suburbs too. While most children in Connecticut graduate from high school without ever mastering basic math and English, the failure to meet grade-level proficiency in city schools is catastrophic at all levels.

As a result many young people -- most young people in the cities -- enter adult life without the education and job skills necessary to get out of poverty, demoralized, resentful, angry, often unhealthy mentally as well as physically, lacking respect for society and indifferent to decent behavior. These circumstances prove disastrous when they collide with the natural male aggressiveness that has never been tamed by parenting.

Many quickly get in trouble with the law, and repeatedly, and so become still more alienated, not ever understanding what hit them and why, since, after all, the underclass lifestyle has been normalized. Guns are everywhere -- and always will be, no matter what laws are enacted -- and so will always present what seem like opportunities for advancement or settling scores.

"Community-based violence-intervention organizations" and their advocates think that, most of all, these troubled young men need a good talking to, and indeed such counseling can help temporarily in critical situations. But other critical situations soon develop unless someone can escape the underclass culture.

As with so much else wrong with society, government chooses to address only the symptoms, not the causes. Especially with social problems, when government encounters the equivalent of broken pipes flooding a road or basement, it doesn't try to repair the pipes but instead calls for more buckets for bailing. The bucket manufacturers make a fortune but the problem is never solved, since mere remediation quickly becomes too profitable financially and politically.

Government refuses to learn from this though it's an old story. Many years ago an episode of the television drama Law and Order showed police detectives entering a dark and dingy city apartment where an abandoned baby was crying. A veteran detective who had seen it all remarked: "How about if I just take him to Rikers now?" {Rikers Island is New York City’s main prison complex.}

* * *

PARENTAL BILL OF RIGHTS: While the formal text of the "parental bill of rights" proposed by the Republican candidates for Connecticut governor and lieutenant governor, Bob Stefanowski and Laura Devlin, which was cited in this column last week, does not say so explicitly, Stefanowski elaborates that its provision on school choice means to make church schools eligible for state-financed student vouchers.

xxx

SOCIAL SECURITY TAX: Supporting U.S. Rep. John B. Larson's legislation to strengthen the Social Security system, this column last week misstated the annual personal income level at which the Social Security tax is lifted. It is $147,000, not $400,000. To improve the system's financing, Larson's legislation would impose a special 2 percent tax on incomes above $400,000.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Connecticut. He can be reached at CPowell@JournalInquirer.com.

Will it into order

“I'm a Mess” (mixed media on canvas), by Sonja Czekalski, in her joint show, “Body/Image,” with Tracy Wesisman, at Hera Gallery, Wakefield, R.I., through Oct 8.

For more information, hit this link.

The Gallery says:

“These two, concurrent solo exhibits explore ‘changing body and societal expectations’ and ‘womanhood and women’s bodies through the female gaze.’ Both women's work, from Weisman's fiber and mixed-media pieces to Czekalski's mixed-media and sculptural assemblages interrogate society and culture from a woman's point of view.’’

The Bell Block in Wakefield, in “South County, R.I.

— Photo JacobKlinger

Don Pesci: An apolitical and literary jaunt in The Berkshires

A view of the Mt. Greylock Range from South Williamstown (from the west). The Hopper, a cirque, is centered below the summit.

—Photo by Ericshawwhite

Arrowhead, where Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick.

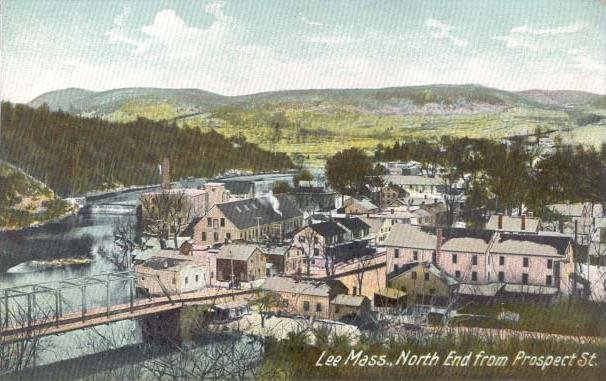

Lee, Mass., in The Berkshires, is everyone’s vision of a typical New England town. The Main Street is short and to the point. Buildings, unmolested by town planners, have maintained their character throughout the years. The house where we bunked for several days dates from the 19th Century and has been well kept by its owner, an engineer who had, like Odysseus, moved about in the world. He was born, very likely in or near the house we occupied, moved with his family to Washington, D.C., where his father had found a job that he could not refuse as an electrical engineer, and later back to Lee.

The firehouse across the street from Garfield House, where we stayed, is a solid stone structure that boasts a square steeple that one easily might mistake for a bell tower or a medieval watch tower.

Traveling around New England, one must – delicately, delicately – approach the topic of politics. Open wounds are everywhere. Much of New England is solid ultramarine blue (there are dramatic exceptions, such as Aroostook County, Maine). That is to say that many people in New England wish to see former Donald Trump in leg irons waltzing through a prison yard. My wife, Andrée, believes that such emotions are far too enthusiastic. She taught American Studies for many years and is intimately familiar with the religious enthusiasms of the 17th Century that saw a witch behind every bush.

Trump, she likes to say when not in the presence of people still suffering political whiplash from the 2016 Hillary Clinton/Donald Trump campaign, is, in some respects, a man more sinned against than sinning, though, of course, she would never say such things in the presence of those who wish to burn Trump at the stake – which is to say, in a good deal of New England. Consider that Democrats in Connecticut, a part of New England and our home state, outnumber Republicans by a two-to-one margin, with unaffiliateds topping Democrats by a small number.

Andrée laid down the law long ago: There will be no politics spoiling our vacations. This law of the household precedes Trump’s ascendency to the presidency by, say, a half century or more. No politics means no computers, no cell phones, no newspapers, no furtive notes written in the shadows, and only mercifully brief encounters with witch-burners.

“Just change the subject, will you?”

In very few places throughout the world -- Washington, D.C., of course, other uncivilized places that used to be part of the British Empire, including most of New England, and Italy— everywhere and always – political talk with strangers destroys the moment, and living in the moment is essential to travel. In Florence, Italy, we almost missed, through dreamy inattention, the spot where Savonarola had been burned at the stake. It is a grave sin to have eyes and not see, ears and not hear, when traveling about the world.

Just ask Odysseus, a victim of enchantment and forgetfulness during the year he spent, not unpleasantly, with Circe. First, the traveler forgets where he is, then who he is, and then the once-solid world dissolves like a dream.

“Pay attention!”

It was no chore for us to pay attention to Herman Melville, most famous, of course, as the author of Moby Dick. In college, he was our literary touchstone. One day, early in our marriage, I brought home a little-read book by Melville, Pierre or the Ambiguities. It’s a romance novel, and Andrée, an incurable romantic, fell for it head over heels. A little later, though we already had been married a couple of years, she fell for me, not quite head over heels.

We had visited Arrowhead, Melville’s home in Pittsfield, years earlier when the house was in transition. No one was home, the house, garnet-red at the time, was dark and forbidding and vacant. Even the spirit of the place had taken flight. We peeked in the windows. Off in the background, Mt. Greylock, the highest elevation in Massachusetts, showed his hump.

Melville wrote Moby Dick in this house. He dedicated the book to his good friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, then living part time in nearby Lenox. The book following Moby Dick, Pierre or the Ambiguities, was dedicated as follows: “'To Greylock's Most Excellent Majesty ... the majestic mountain, Greylock — my own more immediate sovereign lord and king — hath now, for innumerable ages, been the one grand dedicatee of the earliest rays of all the Berkshire mornings, I know not how his Imperial Purple Majesty ... will receive the dedication of my own poor solitary ray ...''

Greylock, we found, was full of winding ways, but so was Melville’s route through a tortuous world. Moby Dick, now considered a classic American novel, was a conspicuous failure in its day. And it was only after Melville had died that the book rose from its deadening reviews.

Today, as always, the book must be read aloud, not so much with the eye as with the ear of the heart. It is music to the ear and, like all music, it winds its way over long Shakespearian passages, moving gracefully at its own pace. It was this music that had enchanted Andrée so many years ago.

The trip to Arrowhead reminded me that traveling is an inward experience, not merely a collection of interesting photos taken of interesting places along the way.

Mark Twain, a Connecticut resident for many years, traveled widely in Europe. And partly on the basis of that, he wrote a little-read book he considered his best: “I like Joan of Arc best of all my books… It furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.” (The full name of the novel is Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc.)

Twain was anti-clerical, not necessarily anti-religious. But the character of Joan, buried for many years under heaps of anti-Catholic perfidy, was paramount for Twain: “Taking into account…all the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts that tried her for her life—she is easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.”

The Mount, novelist Edith Wharton’s plush estate in Lenox, is only a 10-minute ride from Garfield House.

There’s a picture on one wall in the estate’s mansion of a salon gathering in which Henry James makes an appearance. Anything Jamesian is redemptive for Andrée. As an American Studies and American Literature teacher for many years, both in Catholic and public schools, she taught James and other famed authors to students who eventually came to appreciate James’s long winding prose paths – very Shakespearian and even Melvillean.

Twain was not a James fancier: “Once you put him down, you can’t pick him up again.”

But Andrée likes the winding ways of a strong – dare I say it? -- Faulknerian sentence, very much like the path the imagination takes when it is called into service in our travels.

Our next-door neighbor at Garfield House, a permanent resident and an expat from New York, told us that she had lived for a time in Wharton’s reading room while she was an administrator of the Shakespearian Company that put on plays at The Mount.

“You were an actress?”

“Oh, God no, please no – not an actress. I worked behind the scenes as an administrator to put on the plays.”

“In New York?”

“Yes. New York had become too cloying, so I came here, fell in love with the place and stayed. By the way, you told me that you like golf, but you do not like golfers. Just a word to the wise: You had better not say that to the proprietor of Garfield House, who is an avid golfer.”

I agreed, as Andrée said, to “change to subject” if it came round to golf.

Golf, like politics in New England, has become in recent days a secular religion full of saints and heretics – none of them, unfortunately, quite like St. Joan of Arc.

Twain on politics: “In religion and politics people’s beliefs and convictions are in almost every case gotten at second-hand, and without examination, from authorities who have not themselves examined the questions at issue but have taken them at second-hand from other non-examiners, whose opinions about them were not worth a brass farthing.”

Now there, Andrée might say, is a near perfect Jamseian sentence, very much like the hiker’s paths that cross and re-cross Mount Greylock. Our very last adventure before leaving Lee for home was to ride – not walk – to the top of Melville’s “sovereign lord and king.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn., based columnist.

Front Entrance of The Mount.

— Photo by Margaret Helminska

1907 postcard.

Sonali Kolhatkar: Ehrenreich took apart the American cult of ‘positive thinking’

Boston swindler and con man Charles Swindler (1882-1949), who promoted positive thinking in his investors and whose career is the origin of the phrase “Ponzi Scheme.’’

Via Other Words.org

The late Barbara Ehrenreich was best known for her 2001 bestseller Nickel and Dimed, which showed that hard-working people simply weren’t making it in America.

But Ehrenreich, who died Sept. 1 at 81, made an equally great contribution to economic justice with her subsequent book, Bright-Sided. It argued that the cult of “positive thinking” was putting a smiley face on inequality and “undermining America.”

Bright-Sided was published in 2009, between the Great Recession and the Occupy Wall Street movement, which called attention to the stark economic split between the wealthiest “1 percent” of Americans and the “99 percent” of everyone else.

I had the honor of interviewing Ehrenreich during this period. She explained that “there is a whole industry in the United States invested in this idea that if you just think positively, if you expect everything to turn out alright, if you’re optimistic and cheerful and upbeat, everything will be all right.”

Ehrenreich, who had cancer, said she began her investigation into the ideology of positive thinking when she had breast cancer, roughly six years before Bright-Sided was published. That’s when she realized what a uniquely American phenomenon it was to put a positive spin on everything.

She applied that idea to economic inequality, discovering an entire industry telling struggling Americans that their poverty stemmed from their own negative thinking. It promised they could turn things around if they simply “visualized” wealth, embraced a “can-do” attitude, and willed money to flow into their lives.

Central to this industry are “the coaches, the motivational speakers, the inspirational posters to put up on the office walls,” said Ehrenreich — and many megachurches and multi-millionaire “prosperity gospel” preachers, too. “The megachurches are not about Christianity. The megachurches are about how you can prosper because God wants you to be rich,” she said — adding that in many of them, “you won’t even find a cross on the wall.”

But the cult of positive thinking ultimately has more secular roots. “It grew because corporations needed a way to manage downsizing, which really began in the 1980s,” she said. Businesses that laid off masses of employees had a message that “you’re getting eliminated… but it’s really an opportunity for you. It’s a great thing; you’ve got to look at this positively. Don’t complain.”

Eventually, Americans internalized the idea that losing one’s job has got to be a sign that something better is coming along and that “everything happens for a reason.” The alternative is to blame one’s employer, or even the design of the U.S. economy. And that would be dangerous to Wall Street and corporate America.

Another purpose of fostering positive thinking among those who are laid off, according to Ehrenreich, is “to extract more work from those who survive layoffs.” After all, those who remain employed ought to feel lucky to have a job — even if it means working late hours, working on the weekends, and taking on exhaustive responsibilities. More positive thinking.

Thankfully, Ehrenreich may have lived to see a breaking point.

Since the pandemic, we’ve seen a “great resignation,” a term for masses of Americans quitting thankless jobs. And, more recently, “quiet quitting,” where workers only put in the hours they’re paid to work and no more. How novel!

We owe Ehrenreich a debt of gratitude for shining a light not only on the perversity of the U.S. economic system, but also on the gauzy veil of positive thinking that obscures it.

Sometimes, positive change needs to begin with some not-so-positive thinking..

Ehrenreich may not have lived to see her ideas of economic justice fully realized. But, as she once told The New Yorker, “The idea is not that we will win in our own lifetimes… but that we will die trying.”

Sonali Kolhatkar is the host of Rising Up With Sonali, television and radio show on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. This commentary was produced by the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and adapted by OtherWords.org.

In Boston, the original Christian Science Mother Church (1894) and behind it the domed Mother Church Extension (1906); on the right, the Colonnade building (1972). The reflecting pool is in the foreground. Christian Science, founded in New England in the late 19th Century, is big on “positive thinking.’’

‘Had their look down’

Wesleyan University’s Samuel Wadsworth Russell House, built in 1828, home to the school’s Philosophy Department. The building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2001 and is considered one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the country.

“I remember I grew up in Pasadena in a very, kind of, homogeneous, kind of, suburban existence and then I went to college at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. And there were all these, kind of, hipster New York kids who were so-called 'cultured' and had so much, you know, like knew all the references and, like, already had their look down.’’

Mike White (born 1970), screenwriter and actor

What they’ll remember

— Photo by kallerna

“In early autumn, there’s a concerto

possible when there’s a guest in the house

and the guest is taking a shower and the host

is washing up from the night before….

‘‘Much later they will remember only a color,

a golden yellow, and the sound of their feet

scuffling the leaves. A day without rancor….’’

— From “The Music One Looks Back On,’’ by Boston-based poet Stephen Dobyns (born 1941)

Surreal view

“North Head Afternoon’’ (oil painting), by Evan McGlinn, at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester, in its “Fall 2022 Solo Exhibitions,’’ through Nov. 6.

The gallery says the show features 10 artists representing “a wide range of mediums and styles from photography to painting to etching.’’

Mr. McGlinn's "North Head Afternoon" is “a surreal snapshot of a classic New England scene. The oil painting behind the three bottle-lined windows seems to glow from within, illuminating the space.’’

A romantic route coming?

Long but scenic: Proposed route of Boston-Montreal sleeper train.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

What a neat idea! For years, government officials and businesspeople in New England and Quebec have talked of running an overnight sleeper train, with dining and club cars and even entertainment, from Boston to Montreal, via southern Maine and then up through New Hampshire’s White Mountains and Quebec’s Eastern Townships. Now, spearheaded by a Quebec organization called Fondation Trains de Nuit, the initiative is gaining speed, although the service probably couldn’t start until 2025-2026.

A couple of hundred million dollars would probably be needed to bring the the proposed route, all owned by private railroads, up to passenger-rail standard, but studies suggest it could be successfully marketed. For one thing, it would connect two large and dynamic metro areas (good for the economies of both); for another, projections are that the service’s tickets would cost considerably less than ones to fly, and perhaps most alluring, it would offer a fun, romantic and low-stress route through scenic terrain. And fewer young people these days want to drive.

A friendly reminder

From North Adams, Mass.-based painter Julia Dixon’s current show. “Memento Mori,’’ at the Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Mass.

She says of her show:

“My current painting series … depicts individuals in arresting scenes in order to confront viewers about time and impermanence. These paintings, as well as smaller oil and watercolor studies of skulls, insects, flowers, and other symbolic objects, are meditations on the inevitability of death while, at the same time, affirmations of the beauty and tenderness of life….

“My interest is in juxtaposing symbols hidden in Christian artworks and classical still lives, particularly those of the Dutch Golden Age, with modern secular environments and nature to explore the emotional implications of presence and absence, fear, futility, and legacy.’’

Park Square in downtown Pittsfield in 2014

— Photo by Protophobic

Llewellyn King: The talent shortage that imperils journalism

In the newsroom of the still successful New York Times.

Boston’s Newspaper Row, circa 1906, showing the locations of The Boston Post (left), The Boston Globe (center-left) and The Boston Journal (center-right).

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Journalists can be so good at reporting others, but are seldom good at reporting {on} themselves.”

That is what my friend Kevin d’Arcy, a distinguished British journalist, wrote in an article titled “Living in Interesting Times,” published recently on the Web site of the United Kingdom Chapter of the Association of European Journalists.

D’Arcy, who has worked for major publications in the U.K. and Canada, including The Economist and the Financial Times, argues, “The biggest change is that the job of journalism no longer belongs to journalists alone. To some extent this has always been true but, largely because of social media, the scale is touching the sky.

“This matters for the simple reason that the public lacks the traditional protection of legal and social rules. There is nobody in control. … The common realm is sinking fast.”

So true. But his argument raises the question: Is journalism itself doing its job these days?

I usually eschew discussion about journalism — its present state, imagined biases and its future. Dan Raviv, a former correspondent for CBS News on radio and television, told me in a television interview, “My job is simple: I try to find out what is going on, then I tell people.”

I have never heard the job of a journalist better explained.

Of course, the journalist knows other things: the tricks of the trade, such as news judgment; how to get the reader reading, the viewer watching, and the listener listening and, hopefully, to keep their attention.

Professionals know how to guesstimate how much readers, viewers and listeners might want to know about a particular issue. They know how to avoid libel and keep clear of dubious, manipulative sources.

But journalism’s skills are fading, along with the newspapers and the broadcast outlets that fostered and treasured them.

Publications are dying or surviving on an uncertain drip from a life-support system. Newspapers that once boasted global coverage are now little more than pamphlets. The Baltimore Sun, for example, in its day a great newspaper, once had 12 overseas bureaus. No more.

Three newspapers dominate America: The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and The New York Times. They got out in front and owe their position there to successfully pushing their brands on the Internet early. Now they have still have lots of advertising revenue from their print versions, and increasing revenue from their Web sites, with their pay walls.

Local news coverage may come back as it once was, but this time through local digital sites. I prefer traditional newspapers, but the future of local news appears to be online.

A major and critical threat to journalism comes from within: It is a dearth of talent. You get what you pay for; publishers aren’t paying for talent, and that is corrosive. Newspaper and regional TV and radio salaries have always been abysmally low, and now they are the worst they have been in 50 years. This is discouraging needed talent.

For more than 30 years, I owned a newsletter-publishing company in Washington, D.C., and I hired summer interns — and paid them. Some of the early recruits went on to success in journalism, and some to remarkable success.

Latterly, I got the same bright journalism students — young men and women so able that you could send them to a hearing on Capitol Hill or assign them a complex story with confidence.

The most gifted, alas, weren’t headed for newsrooms, but for law school. They told me that as much as they were interested in reporting, they weren’t interested in low-wage lives.

Most reporters across America earn less than $40,000. Even at the mighty Washington Post, a unionized newspaper, beat reporters make just $62,000 a year.

To tell the story of a turbulent world, you need gifted, creative, well-read people, committed to the job. The bold and the bright are not going to commit to a life of penury.

To my friend Kevin, I must say, If we can’t offer a viable alternative to the social-media cacophony, if we have a workforce of the second-rate, if the news product is inadequate, and untouched by knowledgeable human editors, then the slide will continue. Editing by computer is not editing. I appreciate editing, and I know how much better my work is for it.

The journalism that Kevin and I have reveled in over these many decades will perish without new talent. Talent will out, and hopefully provide the answers that our trade needs.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C. He was an editor at The Washington Post and some other large papers in America and England.

For last time until spring?

“Path through the Dunes” (oil on canvas), by Vermont-based artist, writer and farmer Greg Bernhardt, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

His artist says:

“I am a painter living in central Vermont on a farm that my wife, Hannah Sessions, and I began 20 years ago. With animal husbandry and producing award winning cheeses as the reason why we live where we do, painting and writing has been the method by which we understand what we do here.

Blue Ledge Farm affords us an intimate look at the relationship between people and animals, and an appreciation of the land as we spend the vast amount of our time on this plot of earth and have come to know it as deeply as we could anything.

Since having majored in Studio Art and Creative Writing at Bates College (in Maine) in the late ’90s, and having lived abroad studying the Italian language, Renaissance Art, and Italian Literature in Florence, Italy 1997-1998, I have aimed to merge the central themes of my life and found in the end that all these focal points rely on one another, the farm and its inhabitants, the artisanal cheese craft, and the creative acts of writing and painting about these subject matters.’’

Companies’ creepy surveillance of their own workers

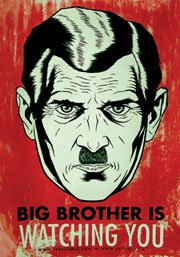

The evil dictator in George Orwell’s 1984

Via OtherWords.org

For generations, workers have been punished by corporate bosses for watching the clock. But now, the corporate clock is watching workers.

Called “digital productivity monitoring,” this surveillance is done by an integrated computer system including a real-time clock, camera, keyboard tracker, and algorithms to provide a second-by-second record of what each employee is doing.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos pioneered use of this ticking electronic eye in his monstrous warehouses, forcing hapless, low-paid “pickers” to sprint down cavernous stacks of consumer stuff to fill online orders, pronto — beat the clock, or be fired.

Terrific idea, exclaimed taskmasters at hospital chains, banks, tech giants, newspapers, colleges, and other outfits employing millions of mid-level professionals.

They’ve been installing these unblinking digital snoops to watch their employees, even timing their bathroom breaks and constantly eying each one’s pace of work. They’ve plugged in new software with such Orwellian names as WorkSmart and Time Doctor to count worker’s keystrokes and to snap pictures every 10 minutes of workers’ faces and screens, recording all on digital scoreboards.

You are paid only for the minutes the computers “see” you in action. Bosses hail the electronic minders as “Fitbits” of productivity, spurring workers to keep noses to the grindstone, and also to instill workplace honesty.

Only… the whole scheme is dishonest.

No employee’s worthiness can be measured in keystrokes and 10-minute snapshots! What about thinking, conferring with colleagues, or listening to customers? No “productivity points” are awarded for that work.

For example, The New York Times reports that the multibillion-dollar United Health Group marks its drug-addiction therapists “idle” if they are conversing off-line with patients, leaving their keyboards inactive.

Employees call this digital management “demoralizing,” “toxic,” and “just wrong.” But corporate investors are pouring billions into it. Which group do you trust to shape America’s workplace?

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.