Faith and sex in New England

The Congregational Church of Middlebury, Vt.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

— Photo by Ms Sarah Welch

“In New England, especially, [faith] is like sex. It's very personal. You don't bring it out and talk about it. “

— Carl Frederick Buechner (born 1926), American writer and Presbyterian minister. He lives in Vermont. He describes his area:

“Our house is on the eastern slope of Rupert Mountain, just off a country road, still unpaved then, and five miles from the nearest town ... Even at the most unpromising times of year – in mudtime, on bleak, snowless winter days – it is in so many unexpected ways beautiful that even after all this time I have never quite gotten used to it. I have seen other places equally beautiful in my time, but never, anywhere, have I seen one more so.’’

In Rupert, Vt.

Ocean warming to continue to move lobster, scallop habitats

Lobsters awaiting purchase in Trenton, Maine.

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

An Atlantic Bay Scallop.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Researchers have projected significant changes in the habitat of commercially important American lobster and sea scallops along the Northeast continental shelf. They used a suite of models to estimate how species will react as waters warm. The researchers suggest that American lobster will move further offshore and sea scallops will shift to the north in the coming decades. {Editor’s note: New Bedford is by far the largest port for the sea-scallop fishery.}

The study’s findings were published recently in Diversity and Distributions. They pose fishery-management challenges as the changes can move stocks into and out of fixed management areas. Habitats within current management areas will also experience changes — some will show species increases, others decreases and others will experience no change.

“Changes in stock distribution affect where fish and shellfish can be caught and who has access to them over time,” said Vincent Saba, a fishery biologist in the Ecosystems Dynamics and Assessment Branch at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a co-author of the study. “American lobster and sea scallops are two of the most economically valuable single-species fisheries in the entire United States. They are also important to the economic and cultural well-being of coastal communities in the Northeast. Any changes to their distribution and abundance will have major impacts.”

Saba and colleagues used a group of species distribution models and a high-resolution global climate model. They projected the possible impact of climate change on suitable habitat for the two species in the large Northeast continental shelf marine ecosystem. This ecosystem includes waters of the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank, the Mid-Atlantic Bight and off southern New England.

The high-resolution global-climate model generated projections of future ocean-bottom temperatures and salinity conditions across the ecosystem, and identified where suitable habitat would occur for the two species.

To reduce bias and uncertainty in the model projections, the team used nearshore and offshore fisheries independent trawl survey data to train the habitat models. Those data were collected on multiple surveys over a wide geographic area from 1984 to 2016. The model combined this information with historical temperature and salinity data. It also incorporated 80 years of projected bottom temperature and salinity changes in response to a high greenhouse-gas emissions scenario. That scenario has an annual 1 percent increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

American lobsters are large, mobile animals that migrate to find optimal biological and physical conditions. Sea scallops are bivalve mollusks that are largely sedentary, especially during their adult phase. Both species are affected by changes in water temperature, salinity, ocean currents and other oceanographic conditions.

Projected warming for the next 80 years showed deep areas in the Gulf of Maine becoming increasingly suitable lobster habitat. During the spring, western Long Island Sound and the area south of Rhode Island in the southern New England region showed habitat suitability. That suitability decreased in the fall. Warmer water in these southern areas has led to a significant decline in the lobster fishery in recent decades, according to NOAA Fisheries.

Sea-scallop distribution showed a clear northerly trend, with declining habitat suitability in the Mid-Atlantic Bight, southern New England and Georges Bank areas.

“This study suggests that ocean warming due to climate change will act as a likely stressor to the ecosystem’s southern lobster and sea-scallop fisheries and continues to drive further contraction of sea scallop and lobster habitats into the northern areas,” Saba said. “Our study only looked at ocean temperature and salinity, but other factors such as ocean acidification and changes in predation can also impact these species.”

Llewellyn King: Prepare for blackouts this summer in the heartland

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Just when it didn’t seem things couldn’t get worse -- gasoline at $5 to $8 a gallon, supply shortages in everything from baby formula to new cars -- comes the devastating news that many of us will endure electricity blackouts this summer.

The alarm was sounded by the nonprofit North American Electric Reliability Corporation and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission last month.

The North American electric grid is the largest machine on earth and the most complex, incorporating everything from the wonky pole you see at the roadside with a bird’s nest of wires, to some of the most sophisticated engineering ever devised. It runs in real time, even more so than the air traffic control system: All the airplanes in the sky don’t have to land at the same time, but electricity must be there at the flick of every switch.

Except it may not always be there this summer. Rod Kuckro, a respected energy journalist, says it depends on Mother Nature, but the prognosis isn’t good.

Speaking on White House Chronicle, the weekly news and public affairs program on PBS which I host and produce, Kuckro said, “There is a confluence of factors that could affect energy supply across the majority of the [lower] 48 states. These are continued, reduced hydroelectric production in the West and the continued drought in the Southwest.”

The biggest threat to power supply, according to the NERC and the FERC, is in the huge central region, reaching from Manitoba in Canada all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico. It is served by the regional transmission organization, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO).

These operational entities are nonprofit companies that organize and distribute the bulk power for utilities in their regions. In California, it is the California Independent System Operator, in the Mid-Atlantic it is PJM, and in the Northeast, it is the New England System Independent Operator. They generate no power, but they control power flows, and could initiate brownouts and blackouts.

With record storm activity and high temperatures predicted this summer, blackouts are likely to be deadly. The old, the young and the sick are all vulnerable. If the electric supply fails with it goes everything, from air conditioning to refrigeration to lights, and even the ability to pump gas or access money from ATMs.

The United States, along with other modern nations, runs on electricity and when that falls short, it is catastrophic. It is chaos writ large, especially if the failure lasts more than a few hours.

On the same episode of White House Chronicle, Daniel Brooks, vice president of integrated grid and energy systems at the Electric Power Research Institute, also referred to a “confluence of factors” contributing to the impending electricity crisis. Brooks said, “We’re going through a significant change in terms of the energy mix and resources, and the way those resources behave under certain weather conditions.”

If power supply is stressed this summer, change in the generating mix will get a lot of political attention: at heart is the switch from fossil-fuel generation to renewables. If there are power outages, a political storm will ensue. The Biden administration will be accused of speeding the switch to renewables, although the utilities don’t say that.

The fact is the weather is deteriorating, and the grid is stretched in dealing with new realities as well as coping with old bugaboos, like the extreme difficulty in building new transmission lines. Better transmission would relieve a lot of grid stress.

Peter Londa, president of Tantalus Systems, which helps its 260 utility customers digitize and cope with the new realities, explained some of the difficulties facing the utilities not only in the shifting sources of generation, but also in the new shape of the electric demand. For example, he said, electric vehicles, particularly the much-awaited Ford F-150 Lightning pickup, could be an asset both to homeowners and utilities. During a blackout, their EVs could be used to power their homes for days. They could be a source of storage if thousands of owners signed up with their utilities in a storage program.

So utilities are facing three major shifts: in generation to wind and solar, in customer demand, and especially in weather. Mother Nature is on a rampage and we all must adjust to that.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Fred Schulte: AARP’s dubious ties with Oak Street Health

In September, AARP, the giant organization for older Americans, agreed to promote a burgeoning Chicago-based chain of medical clinics called Oak Street Health, which has opened more than 100 primary-care outlets in nearly two dozen states, including in New England.

The deal gave Oak Street exclusive rights to use the trusted AARP brand in its marketing — for which the company pays AARP an undisclosed fee.

AARP doesn’t detail how this business relationship works or how companies are vetted to determine they are worthy of the group’s coveted seal of approval. But its financial reports to the IRS show that AARP collects a total of about $1 billion annually in these fees — mostly from health care-related businesses, which are eager to sell their wares to the group’s nearly 38 million dues-paying members. And a paid AARP partnership comes with a lot: AARP promotes its partners in mailings and on its Web site, and the partners can use the familiar AARP logo for advertisements in magazines, online, or on television. AARP calls the payments “royalties.”

AARP’s 2020 financial statement, the latest available, reports just over $1 billion in royalties. That’s more than three times what it collected in member dues, just over $300 million, according to the report. Of the royalties, $752 million were from unnamed “health products and services.”

But controversy has long dogged these sorts of alliances, which have multiplied over the years, and the latest is no exception. Are the chosen partners actually a good choice for AARP’s members, or are they buying the endorsement of one of the country’s most respected organizations with lavish payments?

“I don’t have a problem with AARP endorsing travel packages,” said Marilyn Moon, a health-policy analyst who worked for the group in the 1980s. But when AARP lobbies on Medicare issues while profiting off partnerships with those who are marketing to Medicare patients, “that certainly is a problem,” Moon said.

There are reasons for concern about the latest partnership. Less than two months after announcing the AARP deal, Oak Street revealed it was the subject of a Justice Department civil investigation into its marketing tactics, including whether it violated a federal law that imposes penalties for filing false claims for payment to the government. Oak Street has denied wrongdoing and says it is cooperating with the investigation.

Companies like Oak Street, whose funders have included private equity investors, have alarmed progressive Democrats and some health-policy analysts, who worry the companies may try to squeeze excessive profits from Medicare with the services they market mainly to people 65 or older. Oak Street hopes it can cut costs by keeping patients healthy and in the process turn a profit, though it has yet to show it can do so.

AARP has stood for decades as the dominant voice for older Americans, though people of any age can join. Members pay $16 a year or less and enjoy discounts on hundreds of items, from cellphones to groceries to hotels. AARP also staffs a busy lobbying shop that influences government policy on a plethora of issues that affect older people, including the future and solvency of Medicare.

Perhaps not as well known: that AARP depends on royalty income to help “serve the needs of those 50-plus through education, programs and advocacy,” said Jason Young, a former AARP senior vice president.

“Since our founding, AARP has engaged with the private sector to help advance our nonprofit social mission, including by licensing our brand to vetted companies that are meeting the needs of people as they age,” Young told KHN in an email before leaving his AARP position last month.

For years, AARP has drawn intermittent scrutiny for its longtime partnership with UnitedHealthcare, which uses the AARP seal of approval to market products that fill gaps in the traditional Medicare program — gaps filled by private insurers.

The arrangement has brought in hundreds of millions of dollars in annual royalties, according to court records.

Young said AARP “advocates for policies that are in the best interests of seniors without regard to how it may impact revenue or any licensing agreements.” He said AARP “has taken many strong stands against the insurance industry,” citing opposition in 2017 to proposed legislation that AARP said could have hiked seniors’ premiums by as much as $3,000 a year.

John Rother, who left AARP in 2011 after more than two decades as its policy chief, said business interests were “never a consideration” in these decisions. “I can absolutely say that was never the case,” Rother said. “We separated those operations.”

But that alliance raises alarms among critics who see a conflict of interest that undermines the group’s credibility to speak for all seniors on critical Medicare policy issues.

AARP “is in the insurance business,” said Bruce Vladeck, who ran the Medicare program for several years during the Clinton administration. “There ought to be accountability and visibility about it,” he said.

In 2020, a conservative group called American Commitment went further, concluding that AARP “has grown into a marketing and sales firm with a public policy advocacy group on the side.”

Keeping People Healthy

In a November 2021 conference call with analysts, Oak Street Health CEO Mike Pykosz said he was “thrilled” to be the first primary-care medical provider endorsed by AARP, a decision he said would “enhance our ability to attract and engage patients.”

The company offers “value-based” care to more than 150,000 Medicare patients. AARP officials would not discuss why the group had picked Oak Street Health, except to say that it favors experiments that could improve the quality of medical care and hold down costs.

Oak Street receives a flat monthly rate from insurers for each patient. That “allows us to focus on those services that have the greatest impact on keeping people healthy, such as behavioral health and screening 100% of our patients for the social determinants of health — including food and housing insecurity,” Erica Frank, the company’s vice president of public relations, said in an email.

Frank said Oak Street sees patients in many places where primary care is “either hard to come by or not available.” The company’s patients are seen almost eight times a year on average, versus just three visits for the average person on Medicare, Frank said.

Many of Oak Street’s treatment centers are in communities where poverty levels exceed national norms. The centers typically feature distinctive green and white colors throughout and contain a “community room” with a big-screen television that is also used for activities such as exercise, cooking, and computer classes.

Oak Street participates in a pilot project called “direct contracting,” which Medicare advanced in the final days of the Trump administration. In direct contracting, medical providers accept a set fee to cover all of a person’s medical needs.

In a Senate Finance Committee hearing on Feb. 2, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass.) argued that direct contracting rewards “corporate vultures.” Warren said companies could pocket as much as 40% of their payments as profit.

Supporters argued these concerns were overblown, but the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or CMS, announced a redesign of the pilot program in late February.

The scope of the Justice Department review of Oak Street is unclear. According to the company, DOJ is investigating whether it violated the False Claims Act and is seeking documents related to “third-party marketing agents” and “provision of free transportation” to patients.

Amanda Davis, an AARP senior adviser for advocacy and external relations, said the group learned of the DOJ matter when Oak Street disclosed it publicly on Nov. 8, 2021 — less than seven weeks after their joint venture was announced. “We are closely monitoring this issue’s development and expect all providers to fully comply with all laws and regulations,” she wrote in an email.

Likewise, AARP will not say how much Oak Street paid to become a partner, only that the fee is “for the use of its intellectual property” and that “these fees are used for the general purposes of AARP.” Some feel that’s not enough.

“I think the vast majority of people signing up for these products are not aware that AARP is paid a very large amount for use of their name,” said Dr. David Himmelstein, a physician and professor in the City University of New York’s School of Urban Public Health at Hunter College. He added: “If you are making hundreds of millions selling [health] insurance, it gives you a strong interest in assuring that product remains attractive for people to buy.”

Promoting Independence

Since its founding, in 1958 by a retired high school principal, Ethel Percy Andrus, AARP says it has acted “to promote independence, dignity and purpose for older persons.”

The AARP Foundation provides services such as passing out more than 3 million meals in low-income neighborhoods during the pandemic and assisting older people with tax preparation and legal matters. AARP also awards millions of dollars in annual grants to a wide range of organizations. (KFF, which operates KHN, received a $100,000 grant from the AARP Public Policy Institute for “general support” of KFF’s work on Medicare in 2020 and a similar amount the two previous years related to Medicare policy issues.)

Last year, AARP spent more than $13.6 million on lobbying, according to Open Secrets. More than 60 AARP lobbyists opined on dozens of legislative proposals, from bills intended to protect seniors from scammers to holding nursing homes accountable, according to the campaign finance watchdog group.

Although many supporters argue that AARP pursues worthy goals, criticism of its business dealings goes back years. A 2008 media exposé reported that some AARP members had overpaid for insurance policies because they assumed AARP had the cheapest deal. In 2011, a congressional investigation led by House Republicans found it “unlikely that AARP could survive financially, with its current expenses, if the hundreds of millions of dollars in annual insurance industry revenue disappeared.” The report also questioned whether AARP deserved its tax-exempt status as a nonprofit.

AARP’s health insurance pacts, which UnitedHealthcare refers to as a “strategic alliance,” have been challenged in nearly a dozen federal lawsuits as well — though AARP has prevailed so far.

One group of lawsuits has targeted a type of co-branded AARP-UnitedHealthcare policies called Medigap, which Medicare enrollees buy to pay for items such as copayments for hospital stays and doctor visits. These policies cover about 4.4 million people, according to the company.

AARP receives 4.95% of the premium, which it takes as its royalty, according to court filings. Several lawsuits have argued that amounts to an illegal commission because AARP is not licensed to sell insurance, court records show. The lawsuits cite AARP records showing annual income of hundreds of millions of dollars from the sales.

Federal judges have consistently dismissed such cases, however, ruling that state regulators had approved the rates or that buyers didn’t suffer any real damage.

Helen Krukas, a retiree who lives in Boca Raton, Fla., is appealing in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. She claims AARP failed to disclose that it was “syphoning” 4.95% of what she paid for her policy.

In a deposition, Krukas testified that she “always thought of AARP as a club that negotiates on the behalf of retired people” and “it didn’t even occur to me to look anyplace else” for a policy. “Had I known that they were receiving money for it, I would have gone and shopped around with other brokers,” she said.

Calling for Transparency

AARP has also faced challenges for another type of UnitedHealthcare Medicare policy it has promoted in recent years, called Medicare Advantage.

Critics cite a range of fault-finding government reports, audits, and whistleblower lawsuits targeting such products.

Dr. Donald Berwick, a former administrator of CMS, said Medicare Advantage plans have devised “legal ways” to game the billing system so they get paid “a lot more for writing down things that don’t have much to do with the actual needs of the patients.”

AARP, which strongly supported the 2003 law that created Medicare Advantage, has received a fixed monthly fee from UnitedHealthcare for use of its name in marketing the health plans, according to the 2011 congressional investigation. How much AARP wouldn’t say, then or now.

Medicare pays the insurer a fixed monthly payment for each patient, which rises proportionally to each patient’s burden of illness. More than two dozen whistleblower lawsuits have accused health plans, including UnitedHealthcare, of ripping off Medicare by exaggerating how sick patients are.

Medicare Advantage plans offer tempting extra benefits, such as eyeglasses and hearing aids, and proponents say they cost seniors less than traditional Medicare. But many policy experts argue the plans soak taxpayers for billions of dollars in overpayments every year.

UnitedHealthcare spokesperson Heather Soule told KHN via email that the company “sees incredible value in Medicare Advantage.” When compared with original Medicare, Medicare Advantage “costs less, has better quality, access, and outcomes with greater coverage and benefits and nearly 100% consumer satisfaction,” according to the company.

But the Justice Department’s civil fraud case alleges that UnitedHealthcare reaped $1 billion or more in illegal overcharges. The company has denied the allegations, and the case is set for trial late next year.

As the debate over how to contain Medicare costs intensifies, reformers say AARP should be an ally, not a beneficiary of industry largess.

“It’s hard to know whether they’re advocating for their business interests or for the seniors that they are supposed to represent,” said Joshua Gordon, director of health policy for the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonpartisan group.

Fred Schulte is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

And now on to renewable natural gas in New England

Pipes carrying biogas (foreground) and condensate

— Photo by Volker Thies

Edited from a report by The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“National Grid announced it intends to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, by eliminating fossil fuels entirely from its gas networks. National Grid provides electricity and natural gas to communities in, among other places, central Massachusetts.

“National Grid believes that around 40 percent of fossil-fuel emissions in both Massachusetts and New York come from heating in buildings. They are seeking to remedy this situation by switching to renewable natural gas and green hydrogen, and away from gas obtained from fossil-fuel sources. This renewable natural gas can be obtained from decomposing materials at landfills and wastewater, and green hydrogen can be produced from wind farms. This move comes as many companies say that they are aiming to achieve net-zero emissions to combat climate change.

“‘This fossil-free vision is a historic announcement for National Grid and the United States,’ said John Pettigrew, the CEO of the United Kingdom-based National Grid. ‘We have a critical responsibility to lead the clean-energy transition for our customers and communities.”’

First vegetable crop of spring

“Fiddle ferns {aka fiddleheads}, if you know where to find them {in wet places}, are the first delicacy of spring, appearing even before asparagus. Plunge them briefly into rapidly boiling water, and serve with butter, salt, and if you like, lemon juice. Chapped almonds may be added, or the ferns may be served on hot buttered toast.’’

From Favorite New England recipes (1972), by Sara B.B. Stamm.

Rachael Conway: Meeting looks for ‘equitable pandemic recovery’ at N.E. community colleges

Main entrance to Bunker Hill Community College, in Boston’s Charlestown section.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Rather than return to the pre-COVID-19 state of affairs, policy change is needed to strengthen each leg of the “three-legged stool” of community college success: students’ financial stability, learning inside the classroom, and wraparound support services on campuses, Bunker Hill Community College President Pam Eddinger told the New England Board of Higher Education’s Legislative Advisory Committee (LAC) last week.

The LAC, comprising state lawmakers who are delegates to NEBHE and a few additional sitting legislators from each state, has been convening twice a year since 2013, with each LAC meeting featuring national and regional experts on a pressing higher-education topic.

On March 14, NEBHE hosted its first in-person pandemic-era LAC meeting since 2019 at Lasell University in a hybrid format, with some attendees and panelists joining via Zoom. The first half of the LAC meeting featured a panel discussion on “Doing the Most with the Least: How State Policymakers can Support Wellbeing, Belonging and Success at Community Colleges for an Equitable Pandemic Recovery.”

Panelists included Eddinger, along with: Sara Goldrick-Rab, award-winning author, professor and founder of the Wisconsin HOPE Center for College, Community, and Justice; Linda García, executive director of the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin; Alfred Williams, president of River Valley Community College, in New Hampshire; Audrey Ellis, director of institutional effectiveness at Northern Essex Community College, in Massachusetts; and Eudania Aquino, a Northern Essex Community College Student Ambassador. Joining the meeting in-person, Ellis and Aquino spoke powerfully about Northern Essex’s new Student Ambassador program, a peer-to-peer mentoring program created during the pandemic to foster belonging on the campus as most students had to shift to online learning.

The second part of the LAC meetings offer a colorful snapshot of legislative session updates in the six states, giving lawmakers an opportunity to learn and share models with one another.

The panel discussion and legislative updates yielded rich discussions about challenges and opportunities in postsecondary education facing the region after two years of COVID. Here are five takeaways from the spring 2022 LAC meeting:

1. New England states should look beyond traditional avenues of financial aid to support community college students. Community colleges serve the majority of the nation’s low-income, working and parenting students. These students have much to gain from earning a high-quality college credential. While many New England states administer some form of need-based financial aid, even the lowest-income students still face significant gaps in college affordability, particularly if they are enrolled part-time (as are roughly two-thirds of community college students). Goldrick-Rab advocated for federal emergency aid to become permanent, and urged New England states to follow the lead of states like Wisconsin, Minnesota and Washington, which have instituted state-based emergency funding to ensure that students do not stop-out of college due to being short, say, $300 (a seemingly manageable obstacle but enough to derail an education). She also discussed installing specialists on college campuses dedicated to connecting students to existing public benefits, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

2. Community colleges were struggling to serve students before COVID, and the pandemic added stress to an already-strained system. Eddinger of Bunker Hill in Massachusetts did not mince words: “pre-COVID is no better than post-COVID.” The change, in her words, came from seeing what happened when “we put community college systems through the stress-test” of COVID. Everything—resources, staff, materials and time—“was short, and families were backed up against the wall.” Williams noted that his River Valley Community College serves primarily rural and female students. He underscored his students’ ongoing need for support in the areas of internet connectivity, food and child-care services.

3. Federal CARES funding supported programming at community colleges temporarily, but states must invest in permanently supporting these institutions and their students. Eddinger described federal dollars as “patching a hole.” Ellis outlined how temporary funding from the federal CARES Act allowed Northern Essex Community College to create its Student Ambassadors program, which pays students to serve as peer mentors for students identified as at risk of not persisting. Aquino elaborated on her experience as a Student Ambassador, stating that part of the program’s success comes from its recognition that students benefit from persistent communication and various modes of outreach. García of Texas added that her Center for Community College Student Engagement found that students in danger of not persisting—such as men of color, one of the sector’s most vulnerable groups—felt most connected to their institutions when professors and staff knew their names, helped them establish a long-term plan for their time at the community college, and identified potential barriers to their success. Eddinger remarked on a temporary program at Bunker Hill that provided a small stipend to students in addition to covering tuition and fees, noting, “We realized that it’s not about being able to pay for school. It’s about being able to pay for life.” All of these proven interventions require investing more dollars into community colleges.

4. Faced with declining enrollment, several New England states are looking at college mergers. Connecticut state Sen. Derek Slap (D.-West Hartford), who chairs the state’s Higher Education & Employment Advancement Committee, noted that the state’s General Assembly is moving forward with its plan to consolidate the state’s 12 community colleges into one college with multiple campuses, making it the fifth largest community college in the country. He remarked that the bill has been controversial; some stakeholders are worried that the move will erase the individuality of campuses. Additionally, New Hampshire state Sen. Jay Kahn (D.-Keene) provided an update that lawmakers in New Hampshire are moving ahead with the merger of Granite State College with the University of New Hampshire. Massachusetts state Rep. Jeffrey Roy (D.-Franklin) remarked that the state passed a law in 2019 offering an off-ramp to closing institutions. In the wake of sharp enrollment declines during Covid, mergers represent one method that New England states are embracing to keep public colleges afloat.

5. Every state in the region is working on various efforts to improve college access and affordability. Lawmakers at the March 14 LAC meeting told the group that the Connecticut and Massachusetts legislatures recently pursued bills that address food insecurity on college campuses. Connecticut aims to expand funding for first-time students of its free community college program with additional resources this legislative session. New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Connecticut have introduced legislation supporting student mental health on college campuses. Massachusetts Rep. Patricia Haddad (D.-Somerset), the NEBHE chair, discussed the legislature’s push to expand college access to students with developmental disabilities and autism. The Massachusetts and Connecticut legislative representatives also remarked on their states’ student-debt reimbursement initiatives, which would primarily focus on loan forgiveness for human services and health-care workers.

Look for similar themes around the region in NEBHE’s Legislative Session Summary report outlining current post-secondary and workforce development bills in the six New England states.

Rachael Conway is a NEBHE policy and research consultant who manages the LAC.

It all depends on what you mean by ‘new’

The New England Flag.

“New England is the illegitimate child of Old England….It is England and Scotland again in miniature and in childhood.’’

Calvin Colton, in Manual for Emigrants to America (1832)

xxx

“Of course what the man from Mars will find out first about New England is that it is neither new nor very much like England.’’

— John Gunther, in Inside U.S.A. (1947)

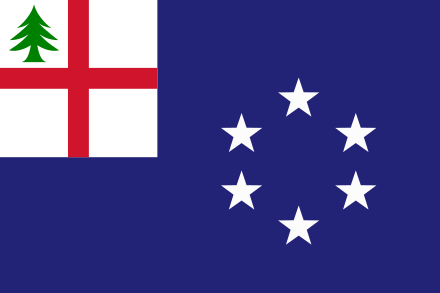

New England by background ethnicity

Chelsie Vokes: What will colleges do if Supreme Court bans affirmative action involving race?

At elite Williams College, in Williamstown, Mass.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

When President Biden nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson for the U.S. Supreme Court, it seemed like a major civil rights victory.

But that victory could feel like a bitter irony this fall, when the high court hears two cases that will likely obliterate affirmative action. If Jackson gets approved by the Senate, she will probably be making two divergent types of history in her first months on the court: being its first black female and hearing cases that could likely overturn 40 years of legal precedents involving race-conscious admissions.

The cases, one against Harvard and the other against the University of North Carolina, were both brought by Students for Fair Admissions (“SFFA”), an organization founded by conservative entrepreneur and long-time affirmative-action foe Ed Blum. If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the plaintiffs, as expected, colleges and universities would not only be barred from using race as a factor in admissions but also prohibited from knowing the race of applicants.

The decisions will likely force schools to completely revamp their admissions policies and rethink how to apply for education grants. Depending on the scope and content of the Supreme Court’s ruling, the decision could affect preferences for first-generation students and reverberate well beyond the realm of education, even jeopardizing grant programs for minority-owned businesses. These cases could also lead to further scrutiny of common practices such as legacy admissions.

In the University of North Carolina case, SFFA argues that whites and Asian American applicants were discriminated against because the university used race as a criterion for admissions. Previous Supreme Court cases had ruled that colleges could use race as one of several criteria for admissions, while prohibiting the use of racial quotas. But now, SFFA says those precedents are wrong and that using race as a criterion is illegal.

Harvard has a holistic process to determine admissions, that is, considering each candidate’s entire high school career and not looking at race as an explicit factor. However, SFFA argued that the subjective and vague nature of these holistic policies leaves room for implicit bias and consequently holds Asian American applicants to a far higher standard than white applicants. In support of its argument, the SFFA questioned why Harvard admits the same percentage of Black, Hispanic, white and Asian American students each year, even though application rates for each racial group differ significantly over time. SFFA says that Harvard must design a new race-blind admissions system.

The court hasn’t issued any opinions on affirmative action since June 2016, which was before Donald Trump was elected president and eventually secured three staunchly conservative appointments to the bench. Unless something unexpected occurs in the next year, it seems likely that the court will ban affirmative action.

The legal change could have huge implications for colleges and universities. If affirmative action is struck down, many colleges will need to overhaul their admissions practices. More than 100 public colleges currently use race as an admissions factor and 59 of the top 100 private colleges consider race as well, according to data from the College Board reported by Ballotpedia. Numerous other colleges that don’t consider race may need to determine whether their admissions policies disproportionally affect one race over others—a big undertaking that could require protracted and complicated analyses.

Colleges believe that diversity is critical to the spread of ideas. But without any race-conscious admissions policies, it’s likely that there will be substantially fewer minorities on many campuses. Past affirmative action bans decreased Black student enrollment by as much as 25% and Hispanic student enrollment by nearly 20%, according to a 2012 study cited by the Civil Rights Project. These bans discourage minority applicants and don’t even result in better academically credentialed student bodies. The Civil Rights Project also reported that SAT math scores dropped by 25 points after such bans.

If the court bans affirmative action, though, colleges and universities can find other methods to create the diverse campuses they desire. Like private employers, who generally can’t consider race in hiring, they could work to expand their applicant pool and encourage minorities to apply. They might also develop increased financial aid and other support programs to boost access to education.

States looking for a race-neutral alternative may follow the lead of Texas, which guarantees public university admission to all students who graduated in the top 10% of their high school classes. However, it is still unclear whether this approach really increases diversity.

Colleges and universities will be able to find ways to preserve—and boost—diversity on their campuses. But they should not wait until the court issues what will likely be a landmark affirmative action decision in the spring of 2023. Colleges and universities will need to make sweeping changes to admissions policies. They need to start preparing now.

Chelsie Vokes is a labor, employment and higher education lawyer with Bowditch & Dewey LLP, in Boston.

And ‘at the mercy of’

“Four Seasons,’’ by Alphonse Mucha (1897)

“Nowhere in the United States of America does the wheel of the seasons turn more brilliantly than in New England. Winter’s blankets of white, the long-awaited buds of spring accompanied by the run of sap, summer’s bouquets, and the magnificent palette of autumn: all are feasts for the senses, and lead to the characteristic New England feeling of existing in tandem with, and often at the mercy of, the great forces of nature.’’

Tom Shachtman (born 1942, Connecticut-based writer and filmmaker), in The Most Beautiful Villages of New England (1997)

In Lexington, Mass., after April 16, 2021 snowstorm.

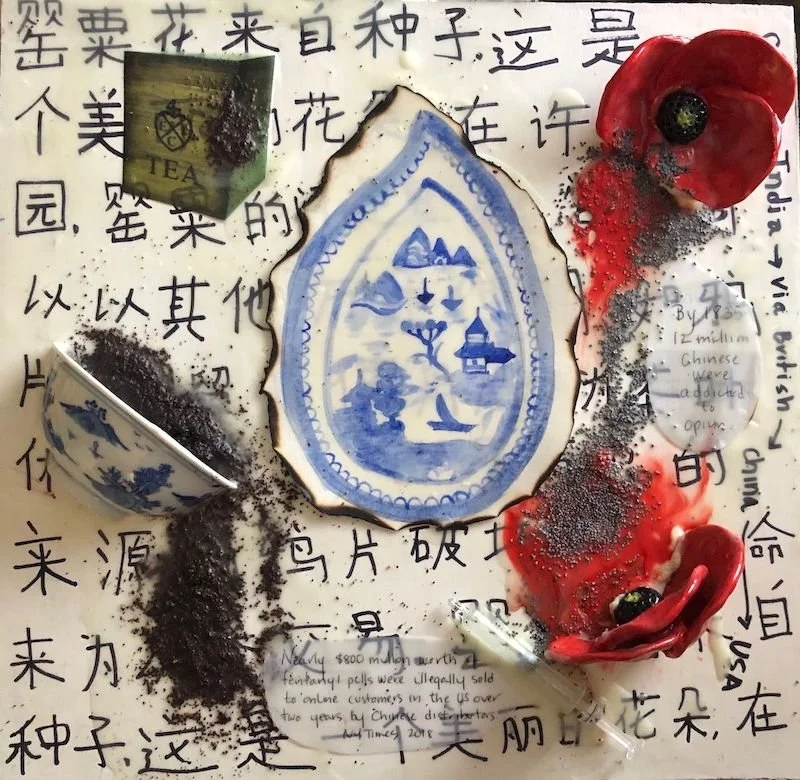

Beauty from New England’s drugged-up China Trade

“China Trade: Opium through the Ages” (encaustic, ceramic made and found objects, tea leaves, poppy seeds on panel), by Cambridge,Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

New England’s “China Trade,’’ in the late 18th Century and the first half of the 19th, created great wealth for some in the region, mostly in and around its ports. Some of the trade involved selling opium to the Chinese. Much of that wealth was invested in what became very lucrative industries, such as textile, shoe and machinery manufacturing and railroads.

In her Web site, Ms. Abbott describes herself thusly:

“Katrina Abbott came to art later in life after her twins were born. Previous to this, she spent 25 years in education, including outdoor education, ocean education at sea and urban public school reform. With a BA in Environmental Biology and a Masters in Botany (studying seaweed!), she reflects her interest in and concern for the natural world in her art. She represents the nature in print, paint, wax ( encaustic) and mosaic. She is a member of the Cambridge Art Association and New England Wax and lives in Cambridge with her husband, their 20 year old boy/girl twins and small brown rabbit named Jarvis.’’

Derby House, in Salem, Mass. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary War merchants in Salem. He was owner of the Grand Turk, said to be the first New England vessel to be used to trade directly with China. There were many mansions built by merchants in the China Trade, some of which was a drug trade.

—Photo by Daderot

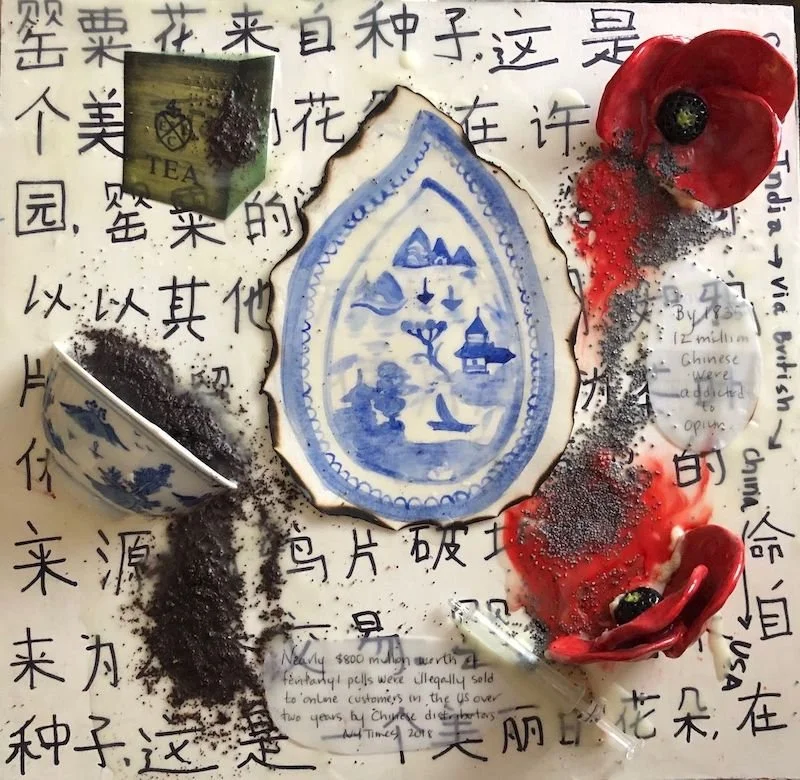

Roger Warburton: Nearby ocean warming a climate-change warning for New England

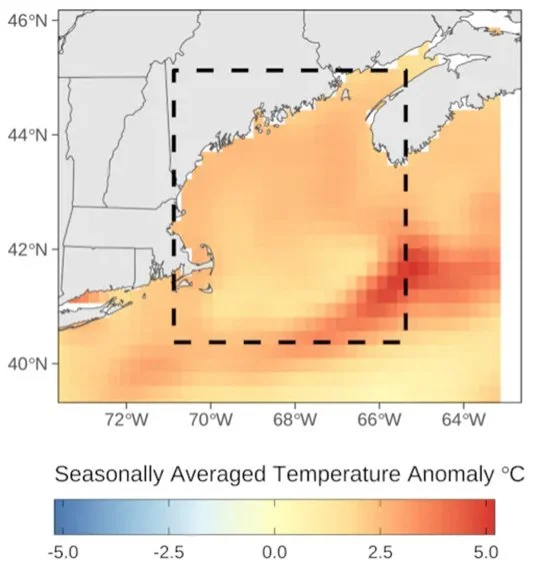

The changes in heat content of the top 700 meters of the world’s oceans between 1955 and 2020.

— Chart by Roger Warburton/NCEI and NOAA

New England’s historical and cultural identity is inextricably linked to the ocean that laps at nearly 6,200 miles of coastline. And the region’s ocean waters are warming, and not just a little.

The above chart shows just how much the ocean has warmed over the past 65 years and, due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases, the heat dumped into the ocean has doubled since 1993. It is even more concerning that ocean warming has accelerated since 2010.

The world’s oceans, in 2021, were the hottest ever recorded by humans.

The findings of the data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), have been confirmed by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics, and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute.

The news for New England is worse, as the ocean here is heating up faster than that of the rest of the world.

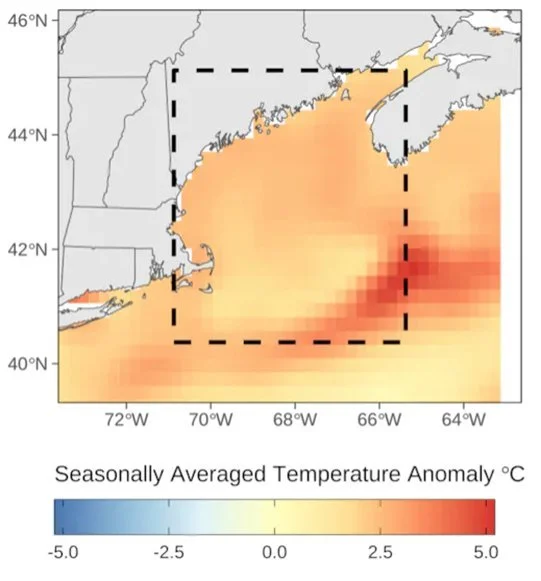

This map illustrates the seasonally averaged sea-surface temperature anomaly in the Gulf of Maine.

—Gulf of Maine Research Institute

The Gulf of Maine Research Institute announced that between September and November of last year, the warmth of inlet waters adjacent to Maine and northern Massachusetts was the highest on record.

“This year [the Gulf of Maine] was exceptionally warm,” said Kathy Mills, who runs the Integrated Systems Ecology laboratory at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute. “I was very surprised.”

The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 96 percent of the world’s oceans, increasing at a rate of 0.1 degrees Celsius (0.18 degrees Fahrenheit) annually over the past four decades.

The increased concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere traps heat in the air. The air in contact with the ocean transfers heat to the ocean, increasing what is called the ocean heat content (OHC).

The first measurements of ocean data were taken on Capt. James Cook’s second voyage (1772-1775). Although not very accurate, those measurements were among the first instances of oceanographic data recorded and preserved.

Today, ocean measurements are taken by a variety of modern instruments deployed from ships, airplanes, satellites and, more recently, underwater robots. A 2013 study by John Abraham, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, contains an interesting historical overview of ocean measurements.

Abraham’s study used data from new instruments, such as expendable bathythermographs and Argo floats. The Argo program is an array of more than 3,000 autonomous floats that return oceanic climate data and has advanced the breadth, quality and distribution of oceanographic data.

As heat accumulates in the Earth’s oceans, they expand in volume, making this expansion one of the largest contributors to sea-level rise.

Although concentrations of greenhouse gases have risen steadily, the change in ocean-heat content varies from year to year, as the chart above shows. Year-to-year changes are influenced by events, such as volcanic eruptions and recurring patterns such as El Niño. In fact, in the chart one can detect short-term cooling from major volcanic eruptions of Mounts Agung (1963), El Chichón (1982) and Pinatubo (1991).

The ocean’s temperature plays an important role in the Earth’s climate crisis because heat from ocean surface waters provides energy for storms and influences weather patterns.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Cheng, L. J, and Coauthors, 2022, “Another record: Ocean warming continues through 2021 despite La Niña conditions. Adv. Atmos. Sci., https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1461-3.

Abraham, J. P., et al. (2013), “A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change,” Rev. Geophys.,51, 450–483, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/rog.20022.

‘The New England idea’ could no longer serve

Dartmouth Hall at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.

“Modern American literature was born in protest, born in rebellion, born out of the sense of loss and indirection which was imposed upon the new generations out of the realization that the old formal culture —the ‘New England idea’ -- could no longer serve.”

— Alfred Kazin (1915-1998), American writer, best known as a literary critic. He wrote a lot about the immigrant experience.

Why Boston is relatively peaceful

A Boston Police Dept. special operations officer

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Boston is one of those few big American cities that hasn’t had a surging homicide rate in the last few years. (The national crime rate, including for murder, remains lower than it was in the 1970’s to 1990’s.)

In 2020, for example, Boston had 56 murders, close to its five-year average of 51, and last year that number fell to 40. The city has in recent years been ranked at about 45th among American cities in murder rates. Consider that Baltimore, which has almost 100,000 fewer people than Boston, had 337 murders last year!

Boston’s relatively good record can be attributed to such things as a neighborhood-focused approach to policing that makes heavy use of local nonprofit and other organizations, including religious organizations. But it’s also that Boston lacks the entrenched culture of violence of many cities and that its residents tend to have fewer guns than residents of most big American cities. Indeed, the gun culture has always been weaker in New England than in most of America, with the notable exception of some thinly populated rural parts, mostly in northern New England. And perhaps the much-noticed proliferation of surveillance cameras in parts of Boston may play some small role in discouraging crime.

And, for that matter, New England, of which Boston is the regional capital, has less crime in general than other regions, in part because it has a more stable population and stronger civic culture, with less of the anomie found in the Sun Belt.

Those who misinterpret (ignoring the line about a “well-regulated militia’’) the Second Amendment like to say “guns don’t kill people, people kill people,’’ so the more guns out there the better!

How disingenuous! It’s “people with guns who kill people,’’ and much faster and more efficiently than with other weapons. Details, details!

In any event, Boston has some lessons for other American cities.

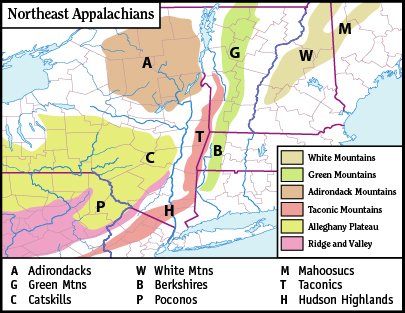

Why New England has a certain coherence and consistency

The flag of the New England Governors Conference. The pine symbol has been associated with the region from early Colonial days. The wood was used for housing, boats and furniture. The nickname of the region’s most wooded state, Maine, is The Pine Tree State.

But the origin of the several similar New England flags also goes back to the Red Ensign of the Royal Navy, first used in 1625, with merchant vessels being granted its use by 1663. Shipping became a major part of the region’s economy early on.

“New England, unlike the rest of the United States and other parts of the world that were colonized by European powers, is a realized idea. The people who, from a European perspective, were its founders had envisioned that New England would continue a tradition in Christian history, and also political history, by becoming a plantation for Christianity in the “new world,” which would function as an autonomous republic.

New England was created by colonists who fanned out from that initial Massachusetts Bay colony. The colonists who were granted the charter for Massachusetts Bay were given small tracts of land. They created new colonies that were pulled together through the forces of economics and culture. So, the vision that shaped the beginnings of Massachusetts was stamped on the region as a whole. New England developed a consistency and coherence that much of the rest of the United States lacks.’’

—- Mark Peterson, a professor of history at Yale University, in an interview with Five Books

English explorer and soldier John Smith coined the name “New England’’ in 1616.

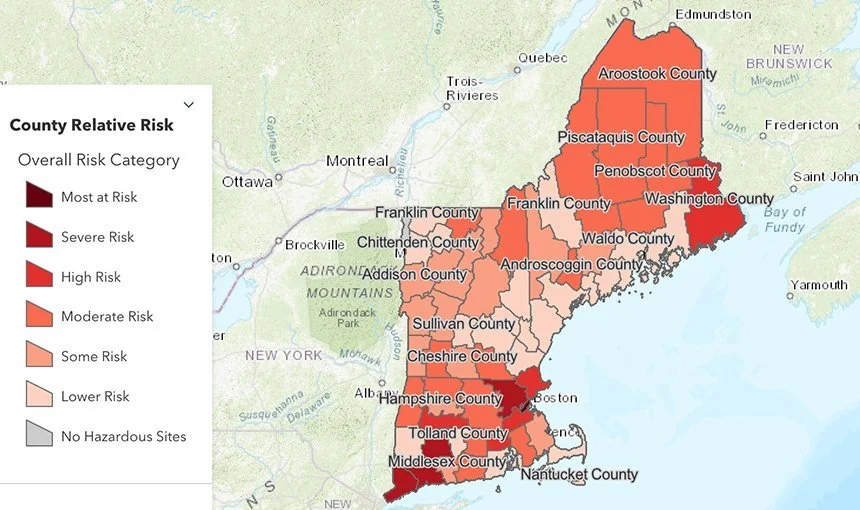

Caitlin Faulds: Trying to keep climate change from turning more toxic at N.E. waste sites

Providence County, in Rhode Island, and Suffolk County, in Massachusetts, are two of the most at-risk counties in New England from pollution buried at toxic sites.

— Conservation Law Foundation map

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Hazardous-waste sites and chemical facilities pockmark New England, leftovers of the region’s industrial past. And little action is being taken to prevent climate change from affecting these sites and cooking up a toxic future, according to analysts at the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF).

A regional report by CLF Massachusetts released this fall combined projections of climate risk with data on social vulnerability and hazardous- waste sites to build a comprehensive map of anticipated toxic-pollution risk from Connecticut to Maine. The results, which show that much of New England could face compounding threats, are startling — even to the mapmakers.

“I bought a house like six months ago … and was actually surprised by the number ... of [Superfund] sites that are in such close proximity to residential neighborhoods,” said Deanna Moran, CLF Massachusetts director of environmental planning. “It’s a little bit scary, but it’s a healthy amount of fear.”

In Rhode Island, Providence County was determined to be the county at highest risk, due to a combination of moderate wildfire risk, severe heat risk, high social vulnerability and 143 hazardous sites. Massachusetts’ s Suffolk County, which includes Boston, was deemed most at-risk in New England.

“A lot of people don’t realize how ubiquitous hazardous sites are, even Superfund sites are, throughout our region,” Moran said. “Even if a site is under remediation or fully remediated, those are the sites that we are still worried about because they were remediated without climate change at the forefront.”

The county-level analysis factors in risk associated with nearly 3,000 hazardous sites. These New England locations include landfills, Superfund sites, brownfields and 1,947 facilities across the region that generate large quantities of hazardous waste or are permitted for the treatment, storage or disposal of toxic chemicals. Many of these hazardous sites are aging, use failing technology, and/or do not have sufficient safeties in place to protect nearby communities in a warmer world, according to the CLF report.

“The techniques that we used to remediate those sites 20 years ago might not anticipate more extreme precipitation or flooding or heat,” Moran said, “and those are the ones that I think are really concerning ’cause they’re really not on the radar.”

Floods could damage infrastructure containing hazardous waste, trigger chemical fires, hinder technology monitoring toxic pollution, and create a toxic stew of floodwater and contaminants, according to the report. Rising temperatures could damage protective caps over contaminated properties and raise the toxicity level of some materials. Wildfires could ravage hazardous-waste sites, damaging protective infrastructure and releasing airborne contaminants.

The lineup of climate risks — which, according to CLF Massachusetts policy analyst Ali Hiple, were “weighted equally” in the report — paints a bleak scene of the region’s future, a future that has been glimpsed in isolated events across the country in recent years.

“Luckily, we have not seen that type of impact in the New England region yet, but we want to make sure that we’re being proactive now and not reactive later,” Moran said.

But despite knowing the dangers that climate poses, federal agencies “are not doing enough to address them, and that puts our communities in danger,” according to the CLF report. In 2019, a U.S. Government Accountability Office report suggested the Environmental Protection Agency should consider climate to ensure long-term Superfund site remediation and protection plans.

“We really just want to see the EPA really leading on this,” said Saranna Soroka, a legal fellow at CLF Massachusetts. “They’ve indicated they know the risk that climate change poses to these sites … but we want to see really consistent, really clear standards applied.”

Soroka noted that the federal agency could analyze climate impact as part of its existing Superfund-site review framework, which mandates site checks every five years. So far, climate analyses have not been incorporated, she said, despite EPA authority to do so.

“I think we’re well beyond the time of thinking through how we should be doing this,” Moran said. “We know the risks are real. In some cases, we’re already seeing them, and the time to be acting on them is now.”

Editor’s note: Here are links to EPA-designated Superfund sites in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Todd McLeish: Weasels seem to be declining in New England and elsewhere in U.S.

The Long-Tailed Weasel seems to be the most common weasel in New England.

A Long-Tailed Weasel in winter coat

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A national study of weasels from across much of the United States has revealed significant declines in all three species evaluated, which has a local biologist wondering about the status of the animals in Rhode Island.

The study by scientists in Georgia, North Carolina and New Mexico found an 87-94 percent decline in the number of least weasels, long-tailed weasels, and short-tailed weasels harvested annually by trappers over the past 60 years.

While a drop in the popularity of trapping and the low value of weasel pelts is partially to blame for the declining harvest, the researchers still detected a significant drop in the populations of all three species.

“Unless you maybe have chickens and you’re worried about a weasel eating your chickens, you probably don’t think about these species very often,” said Clemson University wildlife ecologist David Jachowski, who led the study. “Even the state agency biologists who are charged with tracking these animals really don’t have a good grasp on what is going on.”

The three weasel species are small nocturnal carnivores that feed primarily on mice, voles, shrews, and small birds, often by piercing their preys’ skull with their canine teeth. The weasels prefer dense brush and open woodland habitats, where they search for prey among stone walls, wood piles, and thickets. Because of their secretive nature and cryptic coloring, they are difficult to find and observe.

By assessing trapper data, museum collections, state statistics, a nationwide camera trapping effort, and observations reported on the internet portal iNaturalist, the scientists found the animals to be increasingly rare across most of their range.

“We have this alarming pattern across all these data sets of weasels being seen less and less,” Jachowski said. “They are most in decline at the southern edges of their ranges, especially the Southeast. Some areas like New York and the Canadian provinces can still have some dense pop ulations in localized areas.”

Jachowski noted weasel populations in southern New England are likely facing similar declines as the rest of the country. He believes, however, there is the potential for some areas of the Northeast to still have robust numbers of weasels, especially long-tailed weasels, which are considered the most common of the three species.

Charles Brown, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, who contributed data to the national study, said in his 20 years of monitoring mammal populations in the Ocean State, the only one of the three weasel species he has found is the long-tailed weasel.

“I’ve had a few infrequent encounters with them over the years and seen a few dead ones on the road,” he said. “A mammal survey done in the 1950s and early ’60s documented two short-tailed weasels, and those are the only records I’ve found for the species.”

Least weasels are not found within 300 miles of Rhode Island.

Brown has contributed 19 or 20 long-tailed weasel specimens to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University over the years from many mainland communities, including Little Compton, East Providence, Warwick, and South Kingstown. Weasels are not known to inhabit any of the Narragansett Bay islands.

“It’s hard to say what their status is here,” he said. “Trappers might bring in one or two a year, and some years none, and we don’t have any other indexes to monitor them because they’re cryptic and we rarely see them.”

Brown said a monitoring program could be developed for weasels in the state using track surveys and camera traps, but because the animals have little economic value and do not cause significant damage, they have not been a priority to study.

“In a perfect world, I’d certainly like to try to find a specimen of a short-tailed weasel to see if they’re still around here, but I have nothing to go on about them from a historic perspective,” he said.

Data from the University of Rhode Island is helping to provide a current perspective of the species’ distribution. URI scientists recently concluded a five-year study of bobcats and the first year of a study of fishers, each using 100 trail cameras scattered throughout the state. Among the 850,000 images collected so far are about 150 photos of long-tailed weasels.

According to Amy Mayer, who is coordinating the studies, the weasel images were collected at numerous locations around the state, suggesting the population does not appear to be concentrated in any particular area of Rhode Island.

It is uncertain what could be causing the national decline in weasel numbers, though Jachowski and Brown believe the increasing use of rodenticides, which kill many weasel prey species, could be one factor. A recent study of fishers collected from remote areas of New Hampshire found the presence of rodenticides in the tissues of many of the animals.

“How it’s getting into the food chain in these remote areas, we don’t know,” Brown said. “There was some discussion that a lot of people go up there to summer camps, and when they close the camp up for the season, they bomb it with rodenticides to keep the mice out. That’s just speculation, but it makes sense.”

The decline of weasels may also have to do with changes to available habitat, the scientists said. The maturing of forests and decline of agricultural land has caused a reduction in the early successional habitats the animals prefer. Brown also believes the recovery of hawk and owl populations, which compete with weasels for mice and voles and which may occasionally kill a weasel, could also be a factor.

Jachowski said the findings from his national study have led to the formation of what he is calling a “weasel working group” to share data and discuss how to monitor the animals around the country. Brown is among the state biologists and academic researchers who are members of the group.

“We’re hoping the public will become involved, too, by reporting their sightings to iNaturalist,” Jachowski said. “We need to see where they persist, and then we can tease out what habitats they’re still in, what regions, and then do our studies to figure out what kind of management may be needed.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.e

Gathering around light

“Right Whale Lantern”, by Vermont-based artist and scientist Kristian Brevik in the group exhibition “Light Show.’’ at Dedee Shattuck Gallery, Westport, Mass. through Dec. 21. (North Atlantic Right Whales are in danger of extinction.)

The gallery (which is also a diversified arts center), explains:

“Light Show” is a multimedia group show with work by Adam Frelin, Kristian Brevik, Linda Schmidt, Megan Mosholder and Steven Pestana. Each of these artists utilizes light—either artificial or natural light—as a key component of their work. This exhibition, beginning after Daylight Savings Time and leading up to the winter solstice, celebrates how we create light in darkness, how we gather together and around light sources as the ever-fascinating visual medium of people across time.’’

In a rural, or at least exurban, part of Westport, which has become increasingly attractive to affluent people from Greater New York City and Greater Boston for weekend and summer places. They’re drawn by its countryside, which includes farms and vineyards, its relatively mild climate and Buzzards Bay, which is among the warmest bodies of water in New England in the summer.

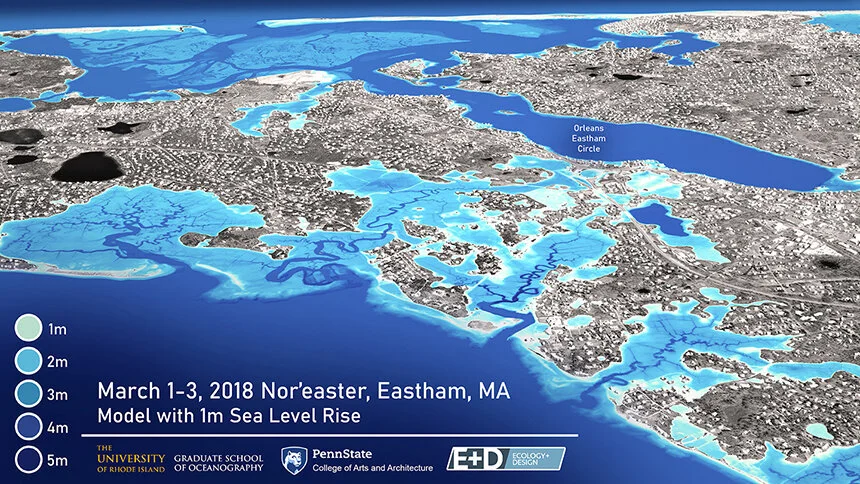

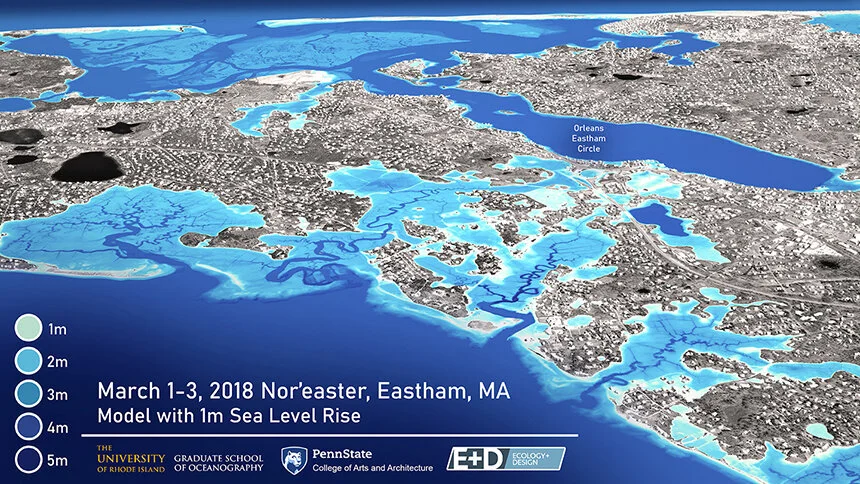

Study to look at relationship of sea-level rise and flooding in hurricanes and nor’easters

Realistic 3D visualization for Eastham, Mass., along the Cape Cod National Seashore using advanced modeling results of a March 2018 nor'easter with 3 feet of sea-level rise

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

KINGSTON, R.I. — Researchers at the University of Rhode Island and Pennsylvania State University were recently awarded a four-year, $1.5 million grant through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to study the effects of sea-level rise and how it may exacerbate the impact of extreme weather.

The project will draw on expertise from researchers at URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography, its College of the Environment and Life Sciences, the Department of Ocean Engineering, and the URI Coastal Resources Center.

Other collaborative participants include the Schoodic Institute, in Maine, and the National Park Service. The goal of the project is to help communities, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service adapt to a changing climate and more frequent and extreme weather.

The rate of sea-level rise is accelerating, according to NOAA. Since 1993, the average global sea level has increased by 3.4 inches. Sea level plays a role in flooding, shoreline erosion and other hazards, impacting nearly 40 percent of the U.S. population living in high-density coastal areas.

However, despite what is known about sea-level rise, there is a lack of research available when it comes to how the impacts of nor’easters and hurricanes may be amplified as a result.

“There are a number of studies that have been done looking at just sea-level rise or just extreme weather, but what we're really lacking in terms of clear understanding is the combined impact of these two phenomena,” said Isaac Ginis, a URI professor of oceanography who is leading the study. “This is especially important to us on the East Coast and in New England, where we’ve seen significant coastal flooding produced by waves and storm surge during nor’easters and hurricanes. How these effects are amplified by sea-level rise has been largely unexplored. This information gap inhibits our ability to properly plan for the future and is likely to lead to under-informed and ineffective adaptation measures.”

The project will expand the body of research related to the effects of extreme weather and sea-level rise on five New England national parks and two wildlife refuges — Cape Cod National Seashore, Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area and New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, in Massachusetts; Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge, Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge and Roger Williams National Memorial, in Rhode Island; and Acadia National Park, in Maine, as well as their surrounding communities.

Using atmosphere, storm surge and wave/erosion modeling the team will provide high-resolution recreations of the impact of future storm and sea-level rise scenarios, identifying vulnerabilities in the ecosystems and infrastructure of the identified sites and their adjacent communities. The modeling will also include hazard, risk, and adaptability assessments, and mitigation scenarios.

Researchers will work closely with the National Park Service, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and stakeholders at the community level to tailor the research and translate the science in a way that can be incorporated into local resource management and adaptation measures to improve coastal resilience and to protect communities, people, infrastructure, and ecosystems.

“Each community has their own needs,” said Ginis, “but our modeling results will produce tailored and tangible information for local decision-makers — state and local governments, emergency management officials, town and city planners, and other stakeholders — to address their specific needs and enable them to plan and adapt as the sea-level rises and climate continues to change.”

Taking historical data into account, as well as topography, geology, water depth, land elevation, natural processes such as shoreline changes, and human influence, the team will be able to project more than 50 years into the future, using 3D visualization to provide computer simulations illustrating storm hazards and identifying potentially effective mitigation measures.

Ultimately, the project will open an important dialogue among researchers, local stakeholders, and federal resource managers, and facilitate the development of science-based best practices that will guide future policies and resource management strategies.

John O. Harney: N.E.’s changing ethnic demographics; shrinking police forces; honorary degrees and culture wars

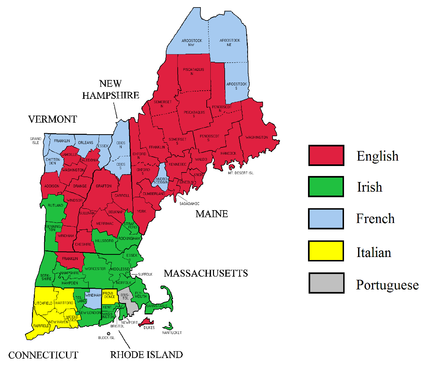

1. Northwest Vermont 2. Northeast Kingdom 3. Central Vermont 4. Southern Vermont 5. Great North Woods Region 6. White Mountains 7. Lakes Region 8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region 9. Seacoast Region 10. Merrimack River Valley 11. Monadnock Region 12. North Woods 13. Maine Highlands 14. Acadia/Down East 15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay 16. South Coast 17. Mountain and Lakes Region 18. Kennebec Valley 19. North Shore 20. Metro Boston 21. South Shore 22. Cape Cod and Islands 23. South Coast 24. Southeastern Massachusetts 25. Blackstone River Valley 26. Metrowest/Greater Boston 27. Central Massachusetts 28. Pioneer Valley 29. The Berkshires 30. South Country 31. East Bay and Newport 32. Quiet Corner 33. Greater Hartford 34. Central Naugatuck Valley 35. Northwest Hills 36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London 37. Western Connecticut 38. Connecticut Shoreline

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Population studies. The U.S. Census Bureau released new population counts to use in “redistricting” congressional and state legislative districts. Delayed by the pandemic, the counts came close to the legal deadlines for redistricting in some states, raising concerns about whether there would be enough time for public input.

The U.S. population grew 7.4% in 2010-2020, the slowest growth since the 1930s, according to the bureau. The national growth of about 23 million people occurred entirely of people who identified as Hispanic, Asian, Black or more than one race.

The Associated Press reported:

The population under age 18 dropped from 74.2 million in 2010 to 73.1 million in 2020.

The Asian population increased by one-third over the decade, to stand at 24 million, while the Hispanic population grew by almost a quarter, to top 62 million.

White people made up their smallest-ever share of the U.S. population, dropping from 63.7% in 2010 to 57.8% in 2020. The number of non-Hispanic white people dropped to 191 million in 2020.

The number of people identifying as “two or more races” soared from 9 million in 2010 to 33.8 million in 2020, accounting for about 10% of the U.S. population.

A few New England snippets

Maine remains the nation’s oldest and whitest state, even though it saw a 64% increase in the number of Blacks from 2010 to 2020, as well as large increases in the number of Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Connecticut’s population crawled up 0.9% over the decade from 2010 to 2020 to 3,605,944 residents. The number of residents who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) increased from 29% of the population in 2010 to 37% in 2020. Connecticut’s number of congressional seats won’t change, but district borders will.

The total population of the only city on Boston’s South Shore, Quincy, Mass., topped 100,000 (at 101,636), as its Asian population grew to represent nearly 31% of all residents. Further south, the city of Brockton’s population increased by nearly 13% as the white population dropped by 29%, and the Black population increased by 26%.

Amazon jungle. Amazon last week announced it will pay full college tuition for its 750,000 U.S. hourly employees, as well as the cost of earning high school diplomas, GEDs, English as a Second Language (ESL) and other certifications. While collecting praise for its educational goodwill, stories of dire conditions in the e-commerce giant’s workplace also triggered a new California law that would ban all warehouses from imposing penalties for “time off-task” (which reportedly discouraged workers from using the bathroom) and prohibit retaliation against workers who complain.

Police shrink. Police forces in New England have recently felt new recruitment and retention pressures. In August 2021, The Providence Journal ran a piece headlined “Promises made, promises delivered? A look at reforms to New England police departments.” GoLocal reported that month that Providence policing staff levels stood at 403, down from 500 or so in the 1980s under then-Mayor David Cicilline. The number of officers employed by Maine’s city and town police departments and county sheriffs’ offices shrank by nearly 6% between 2015 and 2020, according to the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. Reporter Lia Russell of the Bangor Daily News noted, “It’s also a challenge that police in Maine are far from alone in facing, especially following a year during which police practices across the nation were called into question following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin.” The Burlington, Vt., City Council in August defeated efforts to reverse a steep cut in city police ranks. The police department currently has 75 sworn officers, down from 90 in June 2020. A survey by the police officers’ union found that roughly half of Burlington cops were actively seeking employment elsewhere.

Honor roll. Honorary degrees are becoming something of a frontline in the culture wars. Springfield College alumnus Donald Brown, who recently coauthored a piece for NEJHE, tells of his alma mater revoking the honorary master of physical education degree it had bestowed on U.S. Olympic Committee Chair Avery Brundage in 1940. In 1968, Brundage pressured the U.S. to take action against two Olympic athletes who gave the Black Power salute after finishing first and second in the 200 meters. That event was only the tip of the iceberg. Brundage had a history of anti-semitism, sexism and racism. Springfield President Mary-Beth Cooper met with the trustees and others and decided to take back the honor. Meanwhile, the University of Rhode Island has been tying itself in knots over the honorary degree it bestowed on Michael Flynn in 2014, before he was appointed Trump’s national security adviser and accused of sedition.

Refugees. After the U.S. ended its longest war (so far) in Afghanistan and the capital of Kabul fell, the question arose of where Afghan refugees would resettle. New England cities, including Worcester, Providence and New Haven, are among those that have readied plans to welcome Afghan refugees. In higher education, Goddard College President Dan Hocoy said it was a “no-brainer” to offer to house Afghan refugees at its Plainfield, Vt., campus for at least two months this upcoming fall. Back in 2004, NEJHE (then Connection) featured an interview with Roger Williams University President Roy J. Nirschel, who died in 2018, and his former wife Paula Nirschel on the university’s role in its community as well as their pioneering initiative to educate Afghan women.

Sunshine state. Before Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis took his most recent stand against fighting COVID, he displayed a narrow-mindedness that seems to always be in fashion. As Inside Higher Ed reported, after expressing concerns about faculty members “indoctrinating” students, DeSantis signed a law requiring that public institutions survey students, faculty and staff members about their viewpoint diversity and sense of intellectual freedom. The Miami Herald reported that DeSantis and state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, the original bill’s Republican sponsor, suggested that the results could inform budget cuts at some institutions. Faculty members have opposed the bill, which also allows students to record their professors teaching in order to file free speech complaints against them.

New colleges in a time of contraction. The nonprofit Norwalk (Conn.) Conservatory of the Arts announced plans to open a new performing-arts college and welcome its first class in August 2022. It’s unusual news amid the stream of college mergers and closures only widened by the pandemic. Among the challenges, many of the faculty members don’t have master of fine arts degrees that accrediting agencies require and, without accreditation, the college’s students won’t be eligible for federal financial aid or Pell Grants.

The Conservatory says the college will consolidate a traditional four-year undergraduate program into two years of intense training and a two-year graduate program into one year. Meanwhile, up the coast, the (Fall River, Mass.) Herald News reports that Denmark-based Maersk Training and Bristol Community College will work together to turn an old seafood packaging plant in New Bedford, Mass., into a National Offshore Wind Institute training facility to train offshore wind workers, complete with classrooms and a deepwater pool to train and recertify workers. (NEJHE has reported on the need to train talent for the burgeoning industry and the coastal economy’s special role in New England.)

Other higher-ed institutions are shapeshifting. After months of discussions and lawsuits, Northeastern University and Mills College reached agreement to establish Mills College at Northeastern University. Founded in 1852, Mills is renowned for its pre-eminence in women’s leadership, access, equity and social justice. Also, billionaire investor Gerald Chan and his family’s Morningside Foundation gave $175 million to the University of Massachusetts Medical School, which will be renamed the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. That’s the largest-ever gift to the UMass system.

Land deals. I was recently struck by a report titled We Need to Focus on the Damn Land: Land Grant Universities and Indigenous Nations in the Northeast. The report was born of a partnership between Smith College students and the nonprofit Farm to Institution New England (FINE) to look at how land grant universities view their historic relationships with local Indigenous tribes and how food can play a role in repairing those relationships. It grabbed my attention, partly because NEJHE has published some interesting stories about Native Americans and New England higher education. (See Native Tribal Scholars: Building an Academic Community and A Different Path Forward, both by J. Cedric Woods and The Dark Ages of Education and a New Hope, by Donna Loring.) And partly because two NEBHE Faculty Diversity Fellows, professors Tatiana M.F. Cruz of Simmons University and Kamille Gentles-Peart of Roger Williams University, are spearheading a fascinating Reparative Justice initiative. Among other things, Cruz and Gentles-Peart have had the courage to remind us that land grant universities in New England occupy the land of Indigenous communities. The Smith-FINE work offered sensible recommendations: Financially support Native and Indigenous faculty, activists, programs on campuses and beyond; offer free tuition for Native American students; hire Indigenous people, and fund their research.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.