Vox clamantis in deserto

Engagement with Vt. landscape

"The Sky is Falling" (mixed media and acrylic), by Boston area-based Anne Sargent Walker, in the group show “Drawn Togther,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Aug. 28.

Her Web site says:

“Anne’s semi-abstract paintings in oil and acrylic often combine fragments of vintage wall paper, painted birds, jumping men, and other images which explore our relationship to the natural world. Most recently Anne has been compelled to express her concerns over environmental issues. She attributes her interests in nature to childhood summers in Vermont with a naturalist father, and her continuing engagement with the rural Vermont landscape.’’

August wealth

Joe-Pye Weed

“August is ripening grain in the fields, vivid dahlias fling, huge tousled blossoms through gardens, and Joe- Pye weed dusts the meadow purple.”

– Jean Hersey (1919-2007) author of The Shape of a Year, focused on gardening at the home in exurban Weston, Conn., she shared with her husband, the famed novelist and journalist John Hersey (1914-1993)

The Onion Barn, in Weston, where community bulletins are posted.

Warming up nostalgia

Summer afternoon shadow and sun in Acushnet, on the Massachusetts South Coast.

— Photo by William Morgan

Inspiration from travel

“Waterlilies” (encaustic, color pigments), by Jeanne M. Griffin, who is based in Wells, Maine.

Part of her artist statement:

“Travel plays a large role in my life and, over the years, I have visited close to 100 countries. I am particularly drawn to countries of the Third World and love seeking out and visiting with local artists. I have always been fascinated with their weavings and paintings and the textures and patterns they create using various tools and materials….”

“My travels expose me to many ideas and thoughts which percolate in my head and eventually find their way into my work. {For example} I have incorporated printing with Indonesian tjaps (more commonly used in batik printing) combined with encaustic medium and color pigments to produce each one-of-a-kind painting. This is one way of keeping my wonderful memories of these beautiful countries and interesting people alive.’’

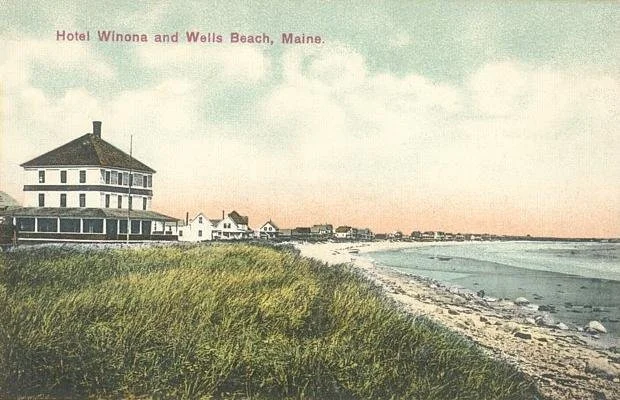

Wells has long been a popular summer resort, as you can see in this 1908 postcard. Founded in 1643, it is the third-oldest town in Maine.

Tidal salt marsh at the Rachel Carson (1907-1964) National Wildlife Refuge, in Wells, named after the prolific writer, marine biologist and conservationist best know for the books Silent Spring and The Sea Around Us. She spent summers on the Maine Coast.

Quiet lope

— Photo by Airwolfhound

“As I followed my road,

the atmosphere altered

into a susurrus under the pines

and took shape in the lightfoot

lope of a rapt fox….’’

— From “Like No Other’’, by Peter Davison (1928-2004) Boston-based American poet, essayist, teacher, lecturer, editor and publisher

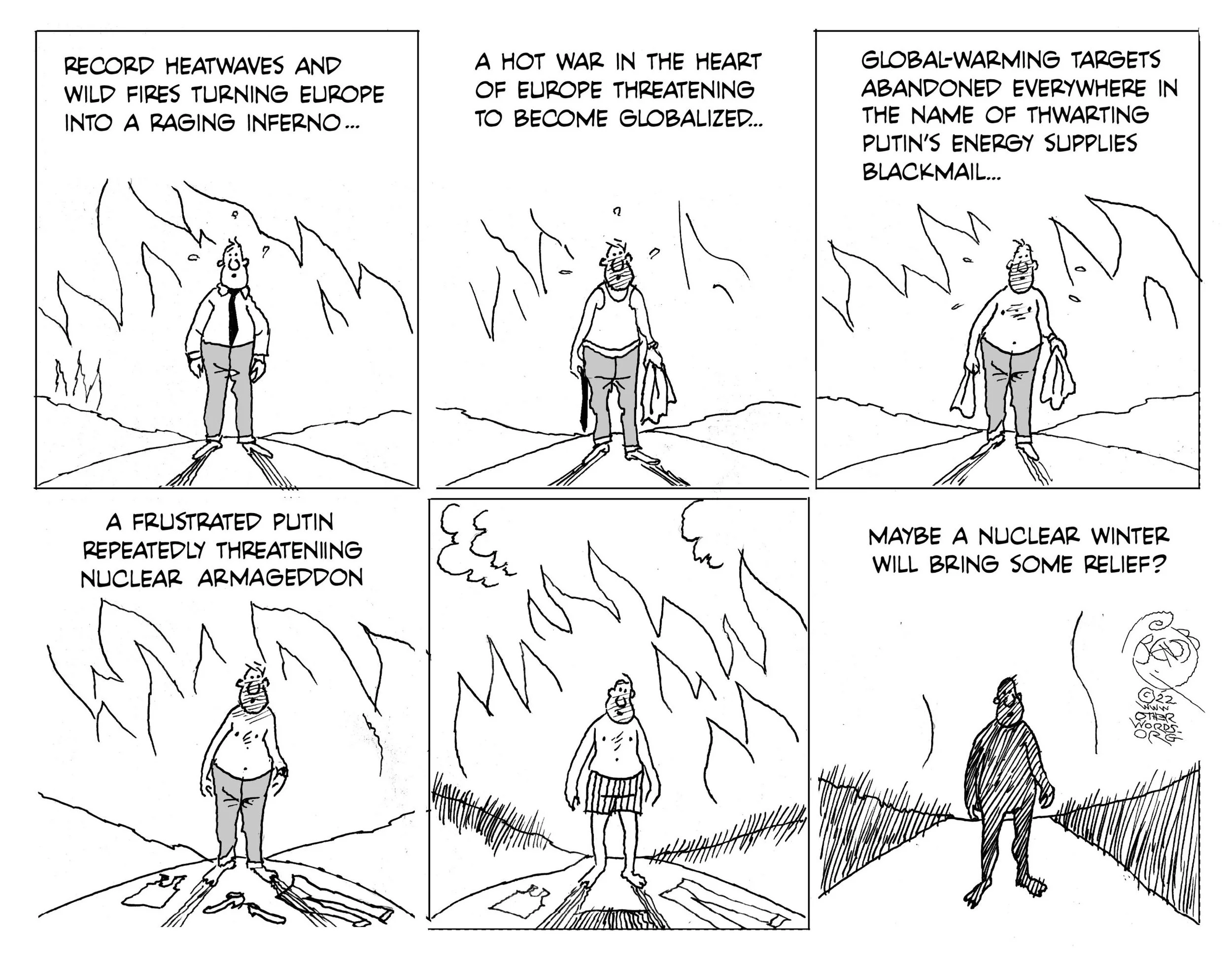

David Warsh: U.S. foreign policy, wars and global warming

American tanks in 1991 during the Gulf War.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I have been dipping into Blood and Ruins: The Last Imperial War 1931-1945 (Viking 2021), by Richard Overy, of the University of Exeter, one of Britain’s foremost historians. The book is brilliant, difficult enough to pick up – 994 pages! – harder still to put down. I have been trying to understand why World War II ended the way it did.

World War II was the America’s first successful war of partition on the Eurasian continent: East and West Germany, the Iron Curtain, all that. A second successful war of seemingly permanent partition followed soon thereafter, in Korea.

The record since then hasn’t been good. America’s wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq all failed to achieve their aims. Now the U.S. is engaged in a proxy war with the Russian Federation, in defense of Ukraine. Meanwhile, China’s determination to take possession of Taiwan looms.

Partition failed in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq because American tactics were inept, borders were porous, enemy supply lines were short; and because the use of nuclear weapons, by now widely held, had become taboo.

What are the chances that the invasion of Ukraine will end in negotiated partition?

I don’t know anything more about the prospects for peace in the war in Ukraine than what I read in four major newspapers I follow. As a former newspaperman, for whom the war in Vietnam dominated most of a decade in my youth, I observe that coverage of the Russian invasion often is accompanied by the same overtones of moral outrage that were characteristic of the early stages of the wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. The Financial Times seems the most consistently balanced of the leading English-language papers, admitting all viewpoints to its opinion pages, favoring none.

But even the FT seems uninterested for the most part in Russia’s side of the story. Vladimir Putin has been clear all along about his objections to NATO enlargement. But the 6,000-word essay he published a year ago, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” spelled out in some detail his version of NATO’s plans for Ukraine’s membership – and for the privatization of Ukraine’s economy.

I am as disgusted by the tradition of Russian disdain for legality, today in Ukraine, as I was in 1956, in Hungary; in 1968, in Czechoslovakia; in 1979, in Afghanistan. This Washington Post story – Russia wants Viktor Bout back, badly. The question is: Why? (subscription may be required) – is evidence that the tradition of lawless brutality has continued under Putin. But in a second-best world, when you routinely can’t get what you want, you must learn to get what you need.

For all this is unfolding against the backdrop of climate change. That story, too, I have been living with for most of my career as a journalist. In the last decade or two, the experience has come to be widely shared. The best metaphor for explicating global warming I know is the one associated with Michael Mann, of Penn State University, author, most recently, of The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet (Public Affairs, 2021).

Last week Mann told an interviewer for National Public Radio, “We frame this as if it’s some sort of cliff that we go off at three degrees Fahrenheit warming or four degrees Fahrenheit warming. That’s not what it is. It’s a minefield. And we’re walking farther and farther out onto that minefield. And the farther we walk out onto that minefield, the more danger that we are going to encounter.”

So back to Blood and Ruins. I cannot recommend Overy’s book highly enough. At the very beginning, he explains that he has taken his title from Imperialism and Civilization, a well-received 1929 book by Leonard Woolf, a political economist (and husband of the novelist Virginia Woolf). “Imperialism, as it was known in the nineteenth century, is no longer possible,” wrote Woolf, “and the only question is whether it will be buried peacefully or in blood and ruins.”

On the last page of his text, Overy concludes, “The Long Second World War… ended not only a particular form of empire, but discredited the longer history of the term.” He quoted the Oxford Africanist Margery Perham from a lecture in 1961 on what she believed had been a profound historical shift: “All though the sixty centuries of more or less recorded history, imperialism, the extension of political power by one state over another, was… taken for granted as part of the established order.”

Since 1945, however, she continued, the only authority that people would now accept “is that which arises from their own wills, or can be made to appear to do so.” Hence the scramble for the status of nationhood since the ‘50s, Overy wrote: There were193 sovereign countries, according to the United Nations, as of 2019.

Has the emergence of China as a hegemonic superpower and Putin’s determination to bundle together Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians in what he calls “a single triune nation,” changed all that? Probably it has. The pressing question now is whether the short-lived period of “the end of history” will conclude relatively peacefully, or enter a lengthy era of heat and ruins.

. xxx

A year ago, on the advice of a knowledgeable friend, I argued that Tunisians deserved a second chance to build a working system of government.

Tunisia had been celebrated as the only Arab nation to turn towards democratic rule since the “Arab Spring” of 201l sent autocrat Zine El Abidine Ben Ali into exile, after 20 years in power. A democratic constitution was adopted in 2014, but a series of coalition governments failed to solve the once-prosperous nation’s growing economic problems and religious strife. Law professor Kais Saied was elected in a landslide in 2019 and sent parliament home in July 2021 to rule by decree since then.

The draft of a new constitution, which, if adopted, would weaken term limits and extend presidential powers considerably, was endorsed by something like 92 percent of those who voted.

The trouble is, only 27.5 percent of eligible voters went to the polls, reflecting a boycott of the referendum by several leading parties. With food and energy prices rising, unemployment high, and tourism stagnant, the situation facing Saied does not seem promising.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

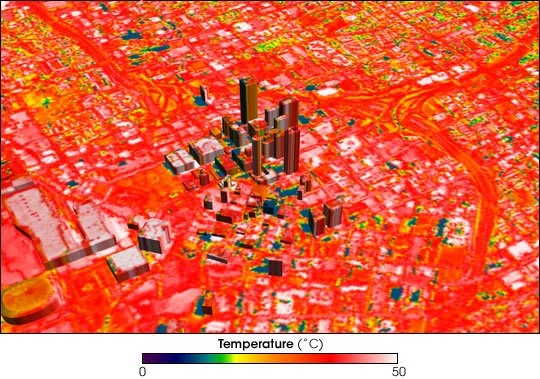

Global average temperature, shown by measurements from various sources, has increased since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

‘I fantasize a riot’

Food fight in Ivrea, Italy

— Photo by Giò - Borghetto Battle of Oranges - Battaglia delle Arance 2007 - Ivrea

“Dessert Is Counted Sweetest’’ (after Emily Dickinson poem. See below.)

(Appeared in the May/June 2022 Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin)

Dessert is counted sweetest

By those who need to diet.

When doctors won't stop nagging,

I fantasize a riot.

Not one of all the cakes and pies

I might forgo today

Could fail to bring me pleasure --

Though later, much dismay.

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman is a Providence-based poet and Brown University philosophy professor.

The Dickinson poem:

Success is counted sweetest

By those who ne'er succeed.

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need.

Not one of all the purple Host

Who took the Flag today

Can tell the definition

So clear of victory

As he defeated – dying –

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Burst agonized and clear!

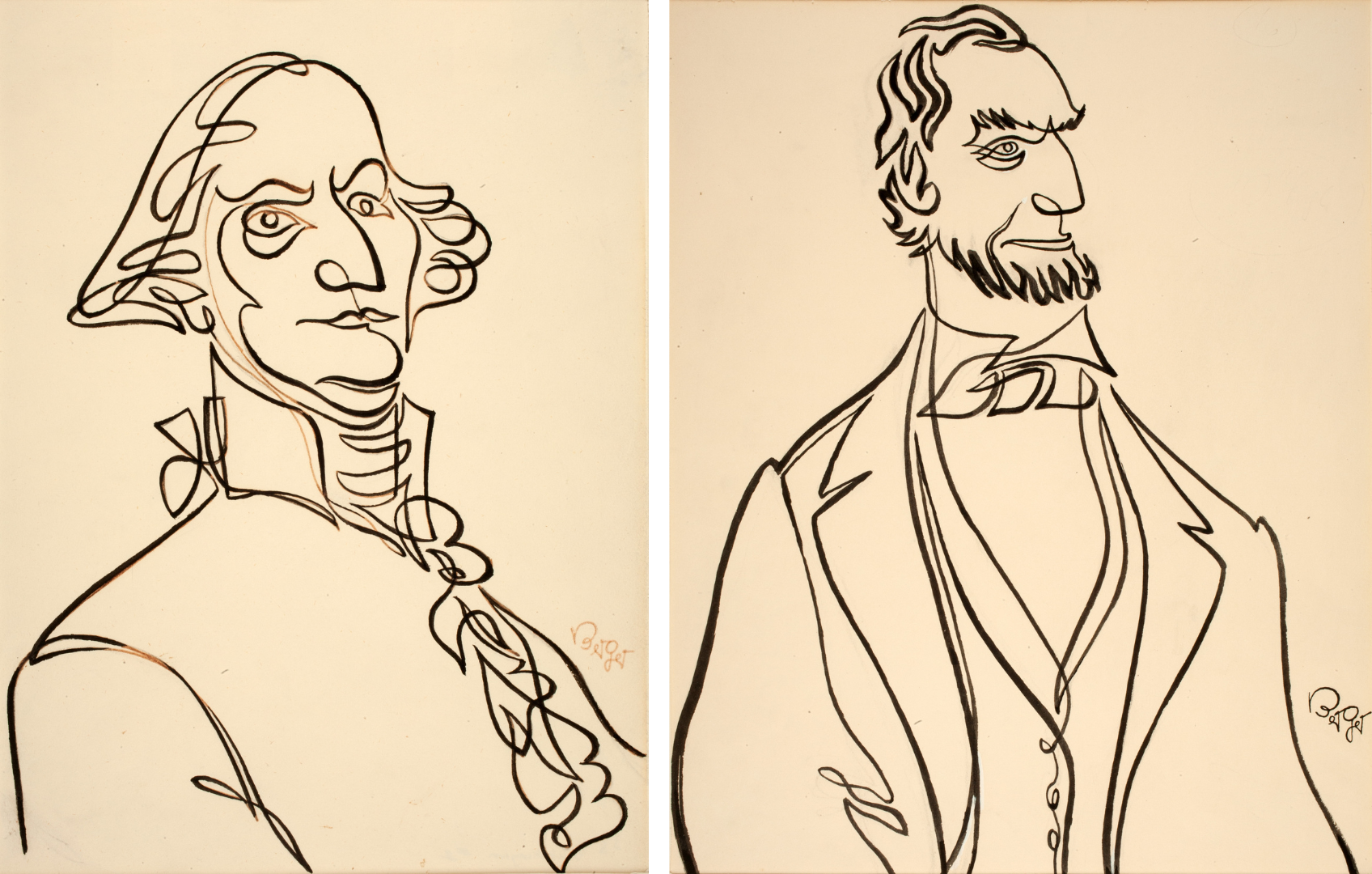

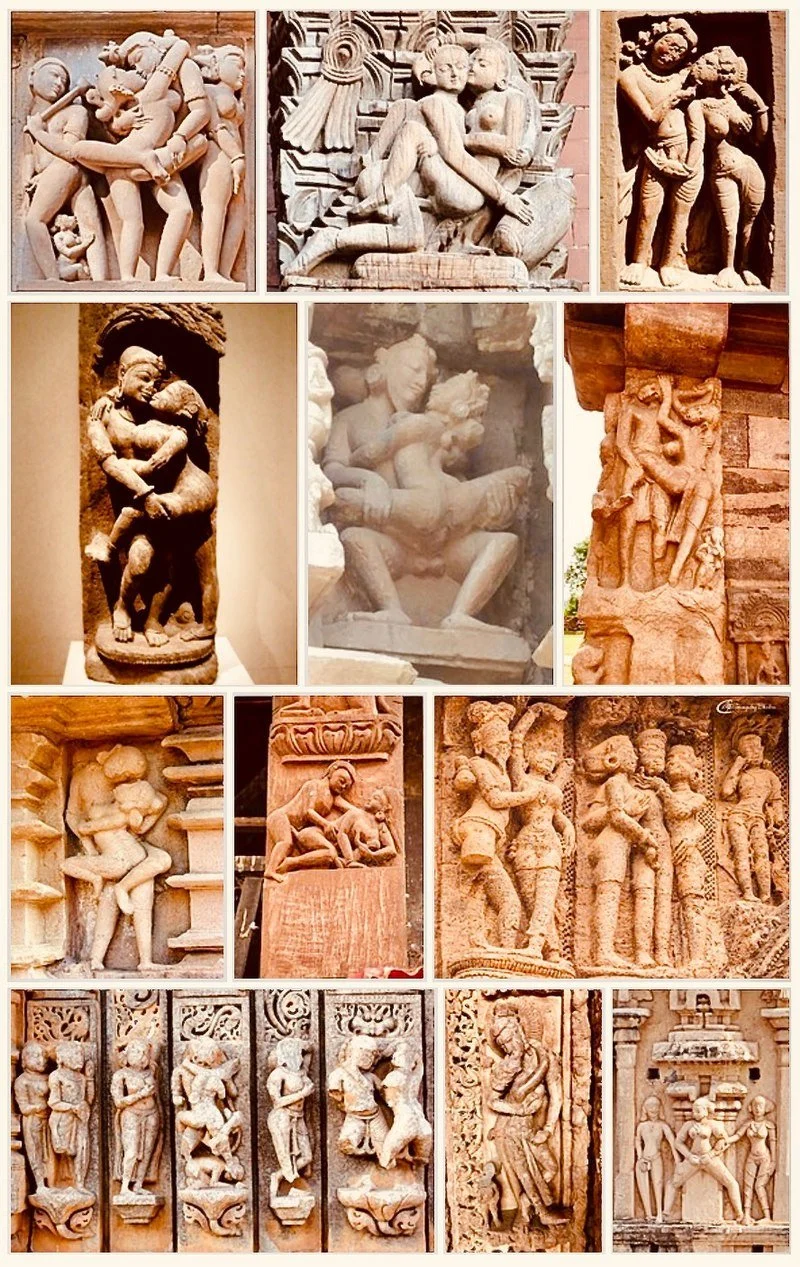

Faith and sex in New England

The Congregational Church of Middlebury, Vt.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

— Photo by Ms Sarah Welch

“In New England, especially, [faith] is like sex. It's very personal. You don't bring it out and talk about it. “

— Carl Frederick Buechner (born 1926), American writer and Presbyterian minister. He lives in Vermont. He describes his area:

“Our house is on the eastern slope of Rupert Mountain, just off a country road, still unpaved then, and five miles from the nearest town ... Even at the most unpromising times of year – in mudtime, on bleak, snowless winter days – it is in so many unexpected ways beautiful that even after all this time I have never quite gotten used to it. I have seen other places equally beautiful in my time, but never, anywhere, have I seen one more so.’’

In Rupert, Vt.

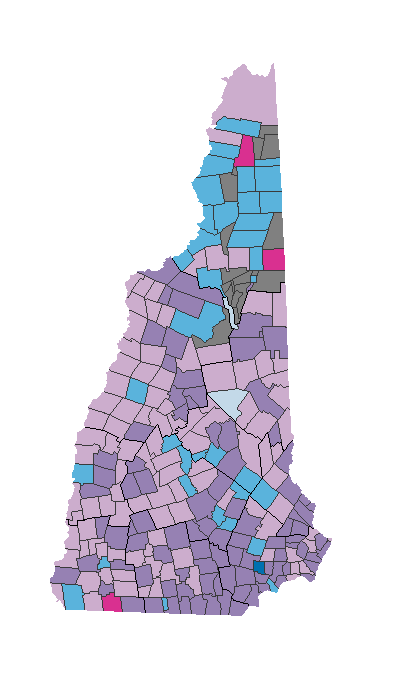

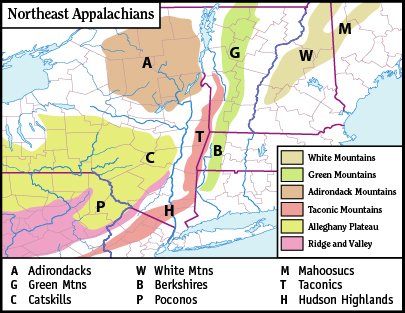

Ocean warming to continue to move lobster, scallop habitats

Lobsters awaiting purchase in Trenton, Maine.

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

An Atlantic Bay Scallop.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Researchers have projected significant changes in the habitat of commercially important American lobster and sea scallops along the Northeast continental shelf. They used a suite of models to estimate how species will react as waters warm. The researchers suggest that American lobster will move further offshore and sea scallops will shift to the north in the coming decades. {Editor’s note: New Bedford is by far the largest port for the sea-scallop fishery.}

The study’s findings were published recently in Diversity and Distributions. They pose fishery-management challenges as the changes can move stocks into and out of fixed management areas. Habitats within current management areas will also experience changes — some will show species increases, others decreases and others will experience no change.

“Changes in stock distribution affect where fish and shellfish can be caught and who has access to them over time,” said Vincent Saba, a fishery biologist in the Ecosystems Dynamics and Assessment Branch at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a co-author of the study. “American lobster and sea scallops are two of the most economically valuable single-species fisheries in the entire United States. They are also important to the economic and cultural well-being of coastal communities in the Northeast. Any changes to their distribution and abundance will have major impacts.”

Saba and colleagues used a group of species distribution models and a high-resolution global climate model. They projected the possible impact of climate change on suitable habitat for the two species in the large Northeast continental shelf marine ecosystem. This ecosystem includes waters of the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank, the Mid-Atlantic Bight and off southern New England.

The high-resolution global-climate model generated projections of future ocean-bottom temperatures and salinity conditions across the ecosystem, and identified where suitable habitat would occur for the two species.

To reduce bias and uncertainty in the model projections, the team used nearshore and offshore fisheries independent trawl survey data to train the habitat models. Those data were collected on multiple surveys over a wide geographic area from 1984 to 2016. The model combined this information with historical temperature and salinity data. It also incorporated 80 years of projected bottom temperature and salinity changes in response to a high greenhouse-gas emissions scenario. That scenario has an annual 1 percent increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

American lobsters are large, mobile animals that migrate to find optimal biological and physical conditions. Sea scallops are bivalve mollusks that are largely sedentary, especially during their adult phase. Both species are affected by changes in water temperature, salinity, ocean currents and other oceanographic conditions.

Projected warming for the next 80 years showed deep areas in the Gulf of Maine becoming increasingly suitable lobster habitat. During the spring, western Long Island Sound and the area south of Rhode Island in the southern New England region showed habitat suitability. That suitability decreased in the fall. Warmer water in these southern areas has led to a significant decline in the lobster fishery in recent decades, according to NOAA Fisheries.

Sea-scallop distribution showed a clear northerly trend, with declining habitat suitability in the Mid-Atlantic Bight, southern New England and Georges Bank areas.

“This study suggests that ocean warming due to climate change will act as a likely stressor to the ecosystem’s southern lobster and sea-scallop fisheries and continues to drive further contraction of sea scallop and lobster habitats into the northern areas,” Saba said. “Our study only looked at ocean temperature and salinity, but other factors such as ocean acidification and changes in predation can also impact these species.”

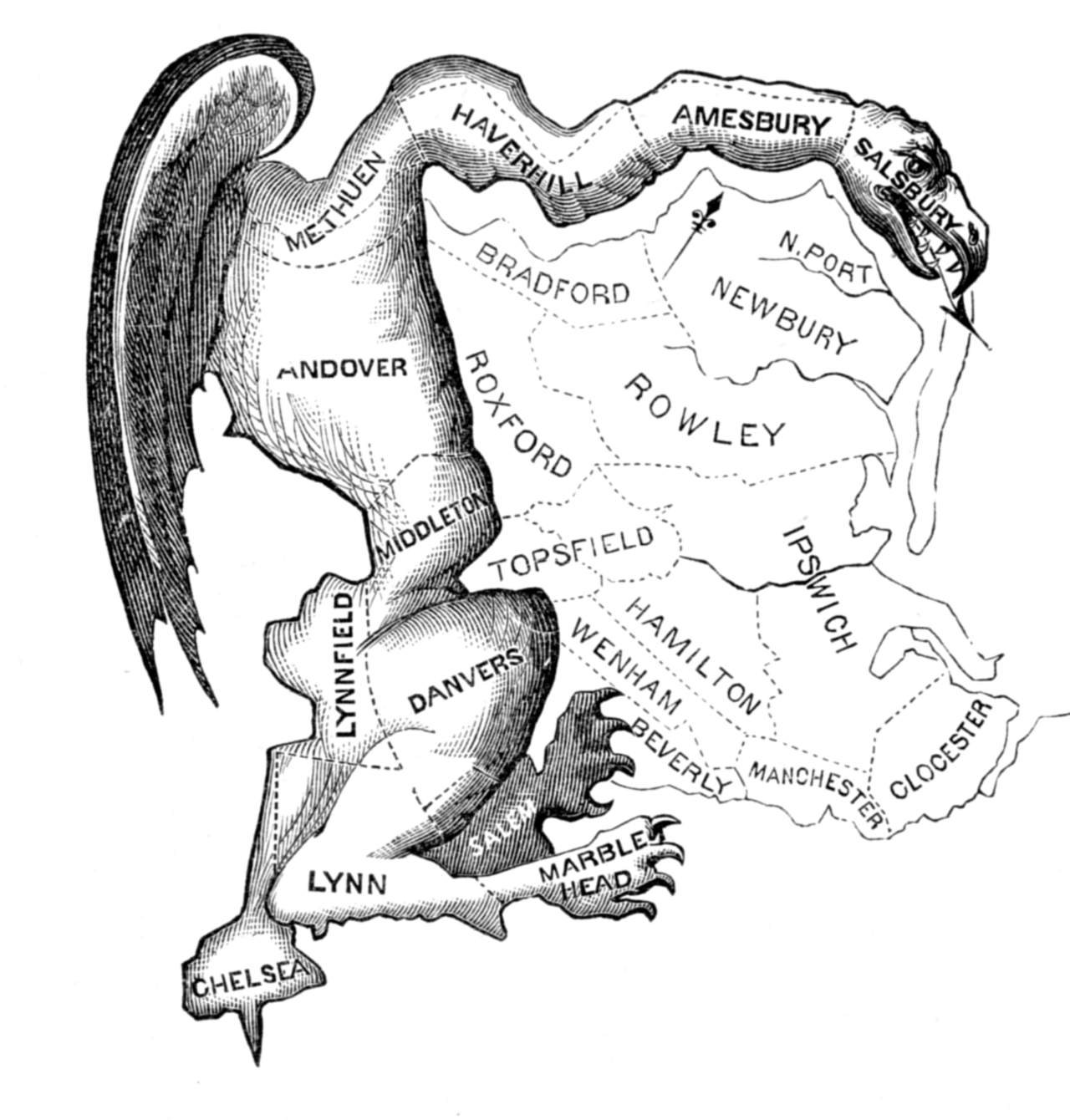

Chris Powell: Conn. budget surplus the flip side of inflation

Price adjustment

— Photo by Jim.henderson

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut state government has had worse managers than Gov. Ned Lamont, but nobody should be much impressed by the huge financial surplus over which he is presiding -- more than $4 billion, equivalent to a fifth of state government's annual budget.

For the surplus is not a product of any astounding new efficiencies in state government achieved by the Lamont administration.

No, state government still spends more every year without any marked improvement in service to the public or the state's living standards.

Instead the surplus arises from billions of dollars in emergency cash from the federal government, distributed in the name of relief from the recent virus epidemic, and from big increases in state capital gains tax revenue.

Most state governments are enjoying big surpluses for the same reasons. But happy days are not really here again, for an old saying from Wall Street counsels caution: Don't mistake a bull market for genius.

Caution is especially advisable now because, on top of the termination of that emergency federal aid, the stock market has more often than not been falling for a few months and is no longer producing capital gains for people who, to get richer, had to do little more than hang around.

The capital gains on which they lately have been paying much more in state taxes are, along with all that federal money propping up the state's financial reserves, mainly the other side of the inflation that is devastating living standards throughout the country and the world.

The U.S. money supply, determined entirely by the federal government, is estimated to have increased by about 35 percent in the last three years even as the number of full-time workers fell, government paid people for not working, and production declined.

More money amid less production is the recipe for inflation, and perhaps not so coincidentally Connecticut state government's financial surplus of about 20 percent of the annual budget is closer to the real annual rate of inflation than the official rate misleadingly calculated by the government, which lately has been about 9 percent.

State government's financial position may look great but it has come at a great cost. Government has saved itself but not the people.

xxx

Connecticut's buzz word of the moment seems to be "equity." It sanitizes almost anything, including the state-licensed growing and retailing of marijuana. Under Connecticut's new marijuana-legalization program, licenses are to be required for large-scale growing of marijuana and to be limited to companies involving people from areas that saw a high level of prosecutions in the "war on drugs."

People who obeyed the drug laws will get no such privileges for their good citizenship.

In essence marijuana licenses are becoming political patronage. Meeting clear criteria won't be enough. The state Consumer Protection Department will award licenses not just according to the criteria but also as favoritism.

So it's not surprising that, as the Connecticut Examiner reported last week, a grower's license is likely to be awarded to a company owned in part by former state Sen. Art Linares, a Republican married to Stamford Mayor Caroline Simmons, a Democrat and former state representative.

That's called working both sides of the street.

According to the Examiner, the "equity" part of Linares's application is a partner who "has lived for five of the last 10 years in a disproportionately impacted area of Connecticut."

That is, a front man. How just and remedial!

All this evokes how Connecticut handled the start of cable television 50 years ago. State law divided the state into franchise areas with a single license to be issued for each. To qualify, a company had to be owned by local residents. But they weren't required to have the capital and expertise needed to operate the business.

So local politically connected people started such companies, got the franchise license, and sold the franchise to a real cable TV company, making a bundle. This racket came to be called "rent a citizen."

Today's marijuana-licensing racket will enrich people who need only to be friends with someone who can pretend to have been oppressed.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

And have an exciting night

“Push Your Beds Together’’ (acrylic, oil stick, pastel, spray paint and latex on canvas), by Brazilian artist Thai Mainhard, in her show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through Aug. 28.

The gallery says:

“Thai Mainhard’s abstract paintings combine expressive mark making with dense blocks of color to create complex and emotive compositions that navigate the space between chaos and calm. Her works draw inspiration from Abstract Expressionism, recalling the work of Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly and Joan Mitchell. Mainhard works with a variety of media—including oil paint, oil sticks, spray paint, and charcoal—to create intuitive imagery that externalizes her feelings and personal experiences.’’

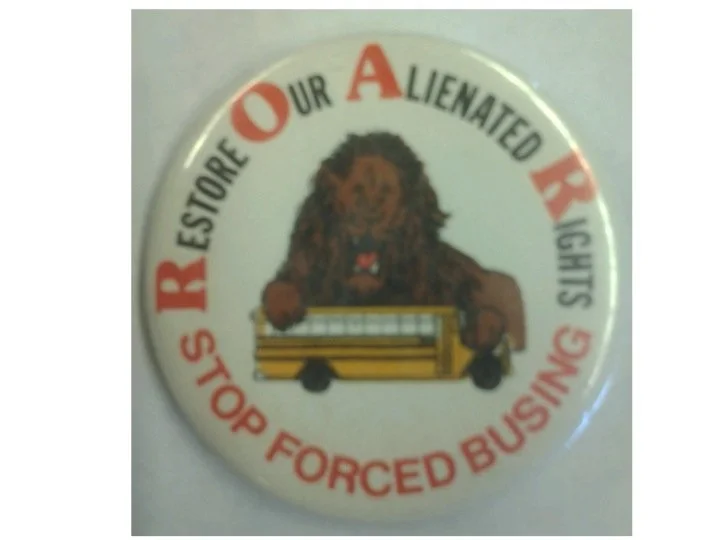

‘Small frightened faces’

Button of organization of white Boston residents (particularly from South Boston and Dorchester) opposed to court orders that mandated the busing of students to help desegregate the city’s public schools. Its initials, of course, were R.O.A.R.

“In 1974, when the City of Boston was desegregating its schools, I watched the news with my dad and saw the police escorts in riot gear, the protesters screaming at the buses, small frightened faces in their windows.’’

Wendell Pierce (born 1963), American actor and businessman. He’s a Black man.

Goes with the territory

“The roaring alongside he takes for granted,

and that every so often the world is bound to shake.

“He runs, he runs to the south, finical, awkward,

in a state of controlled panic, a student of Blake.’’

—From “Sandpiper,’’ by famed American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), who was born in Worcester and died in Boston. She lived in Brazil, among other places.

She spent parts of six summers (1974-1979) on the island town of North Haven Island, Maine, best known for its summer colony of prominent Northeasterners, particularly Boston Brahmins. Among the more notable summer residents was the painter Frank Weston Benson, who rented the Wooster Farm as a summer home and painted several canvases set on the island.

Harborfront and ferry terminal on the island of North Haven.

— Photo by Jp498

“Summer,’’ by Frank Weston Benson

Enjoying the heat, for a while

— Photo by Judson McCranie

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I love air conditioning, as I suspect most people do. We may be bankrupted by having so many cooling devices in our old house, but, hey, one is an environmentally friendly -- relatively! -- a heat pump. Of course, with most of our electricity still generated by fossil fuel, we help heat up the world with our air conditioners.

Still, from time to time, I look back fondly to those dog days of 60 years ago when we sat in a screened-in back porch with a cool slate floor reading and talking in a desultory way in the humid heat with the soft drone of the insects and the whisper of the southwest wind in the oak trees in the background. And how pleasant it was to bring our first (and surprisingly heavy) portable TV out to the porch so we could watch the likes of baseball, Perry Mason and political party conventions in the semi-outdoors, often with Popsicles slicking our hands, though my parents’ steady smoking reduced these pleasures a tad.

It was lovely, to a point, being languid. We lose something in being more and more cut off from the feel of the seasons. Now I’ll go back inside again from the front porch. Hot out here

Illustration of urban heat exposure via a temperature-distribution map: Blue shows (relativel) cool temperatures, red warm, and white hot areas.

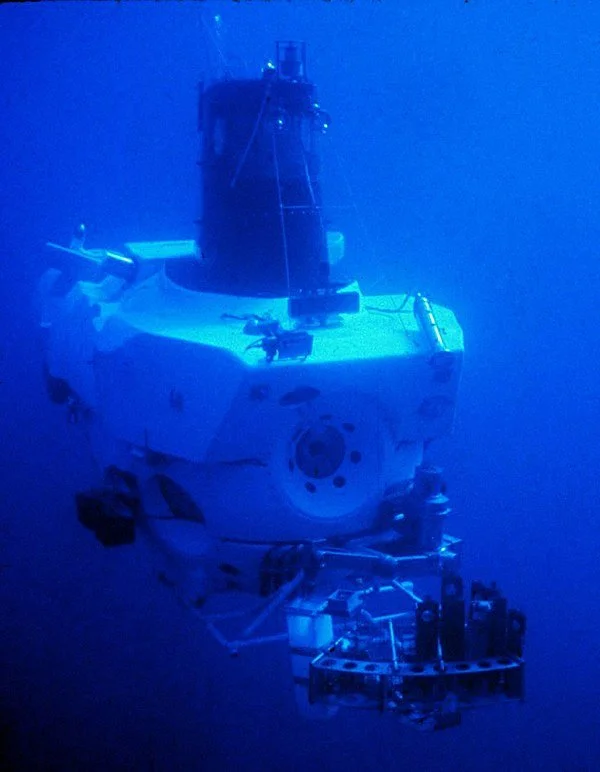

‘Alvin’ goes the deepest yet

Alvin at work

An edited version of a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report:

“The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (a New England Council member) human-guided submersible ‘Alvin’ research vessel has made history by reaching a depth of 6,453 meters (about 21,117 feet). The three-person crew guided the submersible in the Puerto Rico Trench, off that island .… Alvin’s success has led to 99 percent of the seafloor being available for the submersible to explore.

“The submersible is well-known around the world for being an icon of excellent scientific data collecting and engineering. ‘Alvin’ is one of the only U.S. submersibles that have the equipment to carry humans and gather scientific data from extreme depths. Since its initial launch, ‘Alvin’ has carried out 5,086 successful dives. Its long history goes back to when Woods Hole scientist Robert Ballard used ‘Alvin’ to explore the wreckage of the HM Titanic. This summer ‘Alvin’ went through an intense series of sea trials overseen by the NAVSEA, an organization responsible for building U.S. Navy ships. The trials permitted ‘Alvin’ to dive to its maximum depth. The next step for ‘Alvin’ will be a two-week National Science Foundation-funded verification expedition to determine if ‘Alvin’ can maintain its ability to support deep-sea scientific research.

“Woods Hole President Peter de Menocal said, “[i]nvestments in unique tools like ‘Alvin’ accelerate scientific discovery at the frontier of knowledge. Alvin’s new ability to dive deeper than ever before will help us learn even more about the planet and bring us a greater appreciation for what the ocean does for all of us every day.”’

Read more from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Woods Hole (part of Falmouth), with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Marine Biological Laboratory buildings

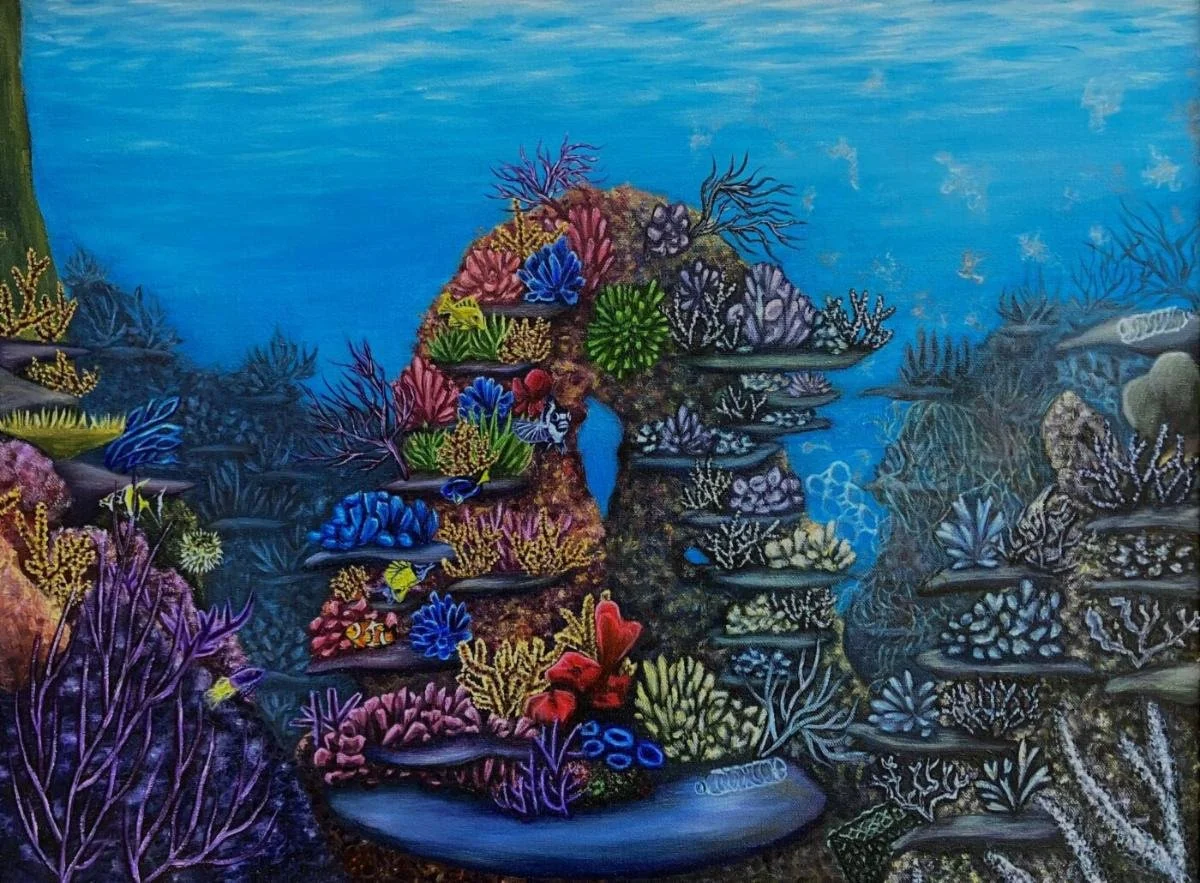

Coral crisis; failed colony

“Bleached” {by ocean acidification?} (oil on canvas), by Weymouth, Mass.-based Elysia Johnson, in the New England Collective XII show at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Aug. 5-28.

Weymouth City Hall, built in 1928 and modeled after the Old State House in Boston, built in 1713.

Weymouth was settled by the English in 1622 as the Wessagusset Colony. That was before Boston (founded in1630) was established by the Puritans and after Plymouth (founded in 1620) was founded by the Pilgrims. The Wessagusset Colony was led by Thomas Weston, who had been a major financial backer of the Plymouth Colony. But the settlement was a failure because the 60 men from London who settled it were ill-prepared for the climate and other hardships there. Further, they lacked the religious drive of the Pilgrims. Wessagusset was founded on purely economic grounds and the 50-60 men there didn’t bring their families.

Bichman House, c. 1650, is likely the oldest surviving house in Weymouth though it looks rather like a modest suburban ranch house.

— Photo by Swampyank

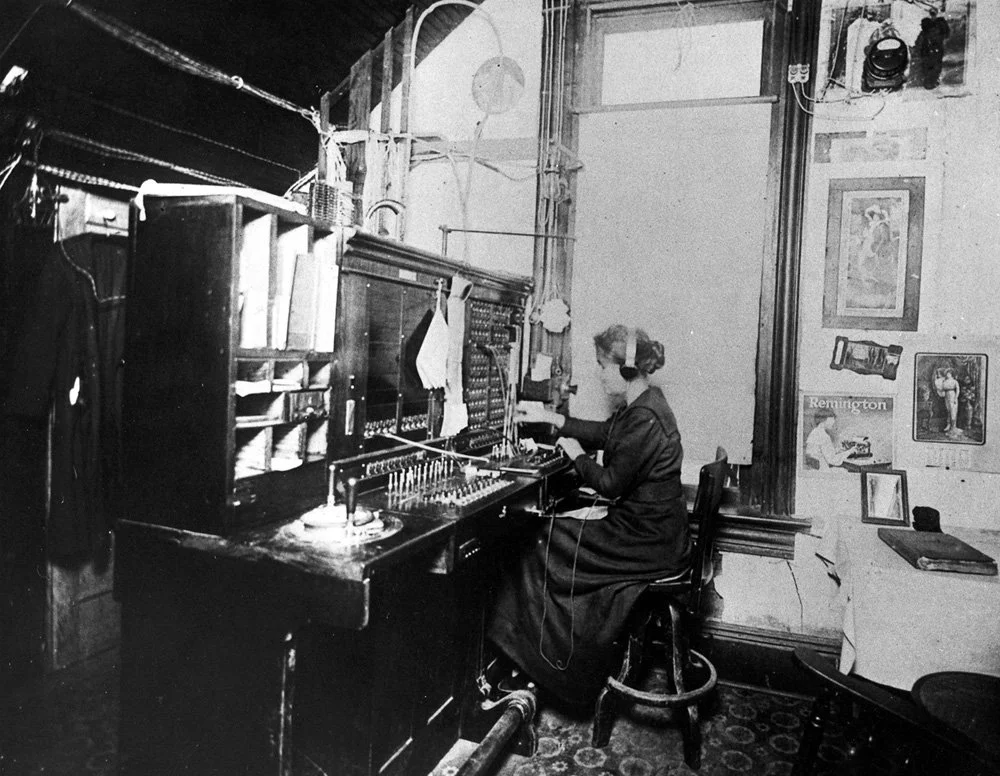

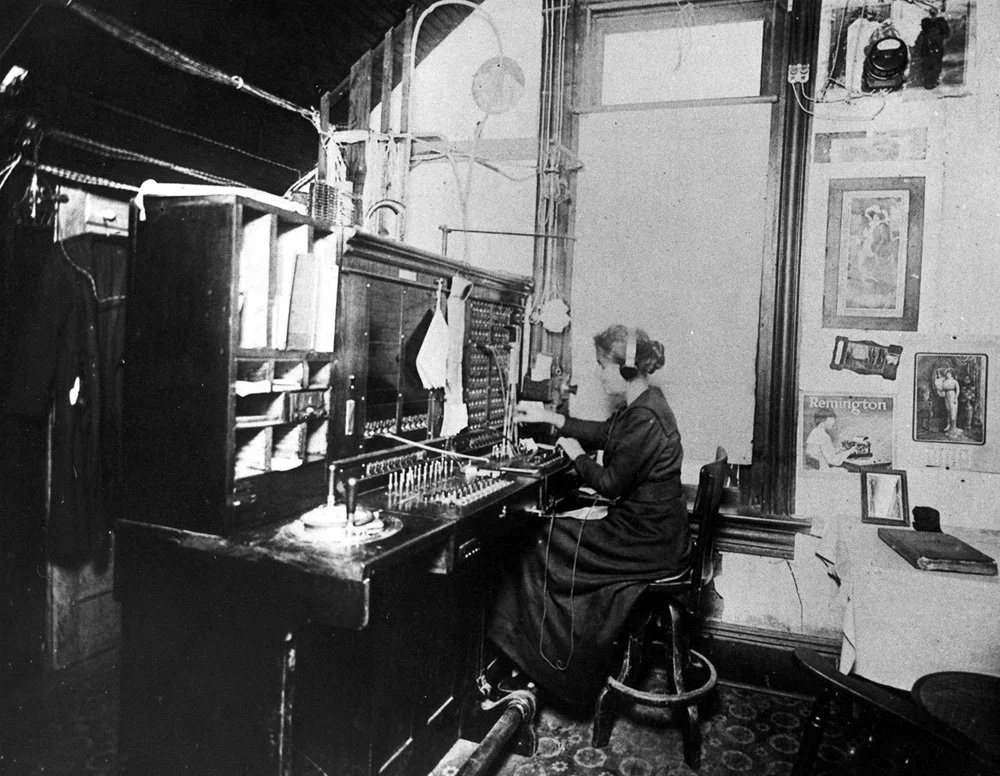

Llewellyn King: The thrill of getting a human on the line; the ‘service economy’ is a giant con

Telephone operator circa 1900.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Something wonderful happened to me this week. I spoke on the telephone to a human being at a credit-card company. Well, not immediately. That would be too much to expect.

I had to go through some of the hoops of the company’s automated phone system, beginning with (as it always seems to) “Listen carefully because our menu has changed.”

And, of course, I had to enter the card number, the PIN, the last four digits of my Social Security number and my maternal grandmother’s name, and learn that for quality purposes my rising frustration was being recorded.

I explained repeatedly to the recording what I needed. It wasn’t having any of it. If it was a sample of artificial intelligence, it was acting more like artificial stupidity.

Finally, the AI device decided that stupid people – me -- weren’t worthy of its recorded messages and transferred me to a “representative.” Banks, credit- card companies, and insurance offices don’t have people; they have “representatives.”

This representative was smiley-voiced and delightful. She also was human. After 20 awful minutes of hearing a recorded voice (“How can I help you? I did not get that. Push 7.”), here was someone who really wanted to help. Hallelujah!

Try talking to a live person, you will like it. It is wonderful. She told me about the weather where she was, San Antonio, and we had a whale of a time doing something that I forgot people can do with a telephone: small talk. In a trice, she took care of my need.

I am a regular panelist on a weekly Texas State University webinar. A super-smart man, a polymath, suggested there that my problem for not reveling in the new isolation -- working from home, talking to machines, sending texts, rather than speaking on the telephone and emailing -- may be generational. This I take to be a nice way of saying that if people had sell-by dates, I am past mine.

The implication is that there is a superior place where the digital people do digital things, and pity those of us who do not do digital things, like eat, drink, fall in love. No less a person than the actor Meryl Streep said, “Everything that truly makes us happy is quite simple: love, sex and food.” If she likes talking, too, I will award her my personal Oscar. Another endearing Meryl quote is, “Instant gratification is not fast enough,”

There is one place where computers have not infringed on the old way of doing things: The U.S. Department of State. I believe that they are still looking up things in giant ledgers and writing by hand on parchment.

I say this because if you, dear citizen, wish to get a passport renewed, the expedited route at your local passport office takes five to seven weeks. I am waiting in apprehension for my renewal, having paid $200 for the super-slow “expedited service.”

You can get a replacement Social Security card in moments, a driver’s license immediately, but the State Department will have none of that.

Oddly, passports are issued to all except those with unpaid child support or outstanding criminal warrants. There are more reasons to deny a driver’s license than a passport. But the wheels at the State Department grind extremely slowly, and time isn't an issue.

The service economy has been a giant con, dreamed up by MBAs to keep customers at a distance or to dehumanize them so that they forget that they pay for the abuse they receive, whether it is from the passport office or some financial institution.

I frequent one gas station, in Scituate, R.I., where they still pump your gas. Night and day, there are lines of motorists waiting for fill-ups, and to have a few cheery words with the pump jockeys. Human contact, real service, seems to be worth a few cents more a gallon.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Hope Dam on the Pawtuxet River in Scituate

Blue gold

Horseshoe crabs mating. Horseshoe crabs live primarily in and around shallow coastal waters on sandy or muddy bottoms. They tend to spawn in the intertidal zone at spring high tides.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When I was a small boy living along Massachusetts Bay, we used to pick up and fling those brown, helmet-shaped and scary-looking, but harmless, arthropods on the lower beach called horseshoe crabs into the water and sometimes even at each other. Little did we know that this species, which goes back almost half a billion years, would become an important bio-medical resource, so much so that, along with habitat destruction, including ocean acidification caused by man-made global warming from burning fossil fuel, the species is endangered in many places.

Horseshoe crabs, by the way, are not crabs. Rather, they’re related to spiders and other arachnids.

For some years, drug companies have been harvesting the bluish blood of the creatures in New England and other places on the East Coast for a protein that’s used to identify dangerous bacteria during new-drug testing, including vaccines.

So important is horseshoe-crab blood that its value is estimated to be $15,000 a quart.

While pharm companies assert that most horseshoe crabs survive after they’re milked and then returned to the water, many die as a result, and over-harvesting is a distinct threat to the future of the species. Of course, everything in nature is connected and wiping out horseshoe crabs will imperil other species.

Consider that they play an important role in the food web for migrating shorebirds, finfish and Atlantic loggerhead turtles.

So let’s hope that environmental regulators pay close attention to the horseshoe-crab population.

They remind us that, with ever-developing scientific knowledge, some previously mostly ignored species turn out to be very important to people and to the wider web of life that humans depend on – a web that people are destroying at an accelerating rate. The more species we can save, the better for us.

Even horseshoe crabs’ eggs are bluish.

Should have stopped at town?

State Street, Boston, in 1801.

“It was a very charming, comfortable old town — this Boston of uncrowded shops and untroubled self-respect, which, in 1822, reluctantly allowed itself to be made into a city.’’

—Mary Caroline Crawford (1874-1932), in Romantic Days in Old Boston