Before the deluge

“The time must come when this coast (Cape Cod) will be a place of resort for those New-Englanders who really wish to visit the sea-side. At present it is wholly unknown to the fashionable world, and probably it will never be agreeable to them. If it is merely a ten-pin alley, or a circular railway, or an ocean of mint-julep, that the visitor is in search of, — if he thinks more of the wine than the brine, as I suspect some do at Newport — I trust that for a long time he will be disappointed here. But this shore will never be more attractive than it is now.”

— Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in Cape Cod (published in 1865)

The dunes on Sandy Neck, in the town of Barnstable.

— Photo by Mr Senseless

‘The complexity of light’

“Shadow Inside 1’’ (gouache on panel), by Cambridge, Mass.-based Vicki Kocher Paret, in show “Shadow,” at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, though June 26.

She says:

"I love the drama of a good shadow: the severe contrast of light and dark, the layers of darkness that fall on various surfaces, the fanciful patterns created from flattened three-dimensional form. Painting shadows is a study in the complexity of light, and often through the process, exposes things unnoticed or unseen. The mesmerizing power and beauty of shadow serves to reveal the extraordinary in the ordinary - a useful thing for the spirit."

My priorities are in order!

“To Lucasta, not Going to the Wars” (with apologies to Richard Lovelace)

(First appeared in English Studies Forum)

Outside are danger, war, and death,

And I could go to fight.

I could go out upon the hill

Or stay with you tonight.

I could go out to save the world

As evil does its worst.

I could go out to save my soul,

Or I could put you first.

The world well lost, my honor, too.

Indeed, I must confess

I could not love thee, dear, so much,

Loved I not honor less.

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman, Providence-based poet and Brown University philosophy professor

Richard Lovelace (1618 -1657) was an English Cavalier poet who fought for King Charles I during the English Civil War. His best known works are "To Althea, from Prison" and "To Lucasta, Going to the Warres".

A great artist paints craftsmen on the Maine Coast

“Shipyard,’’ painted in 1916 by George Bellows (American, 1882-1925). It can be seen at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass.

The museum says:

'‘The museum's permanent collection contains multiple works by American artist George Bellows. Bellows spent a few summers on the coast of Maine and its offshore islands in the early 1910s. The shipyard in Camden particularly drew his attention, and he created a series of paintings based on his time there, including ‘Shipyard’’’.

Camden Harbor. Camden and the Maine Coast in general have a long and famous tradition of boat/shipbuilding, though Camden has long been best known as a summer place for rich Northeast Corridor people (especially old-money WASPS) and others, many of them with fancy boats that they cruise and race in.

‘Two seasons’

“Flaming June” (1895), by Lord Leighton

There is a June when Corn is cut

And Roses in the Seed—

A Summer briefer than the first

But tenderer indeed

As should a Face supposed the Grave's

Emerge a single Noon

In the Vermilion that it wore

Affect us, and return—

Two Seasons, it is said, exist—

The Summer of the Just,

And this of Ours, diversified

With Prospect, and with Frost—

May not our Second with its First

So infinite compare

That We but recollect the one

The other to prefer?

By Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), who watched the seasons with great acuity from her home, in Amherst, Mass.

‘Between permanent and ephemeral’

“Cautionary Configuration” (paint, painted paper, print material and linen, collaged/adhered to panel), by Aaron Wexler, in his show “Everywhere You Go Is a Shape,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art Projects, New Canaan, Conn., June 4-July 23.

The gallery says:

“Wexler uses sourced materials ranging from photographs, printed imagery, illustrations, and his own drawings to create intricately collaged panels and works on paper. Each element is carefully layered and woven into a graphic framework of color, form, and varying textures. Shapes and lines reveal and conceal themselves as they navigate and compete for space on the surface.

In addition to the optical network of color and forms, Wexler plays with texture and weight through the use of different materials. Pieces of coarse and raw canvas are juxtaposed with thinly painted, more transparent Japanese paper, suggesting a push and pull between the permanent and the ephemeral.’’

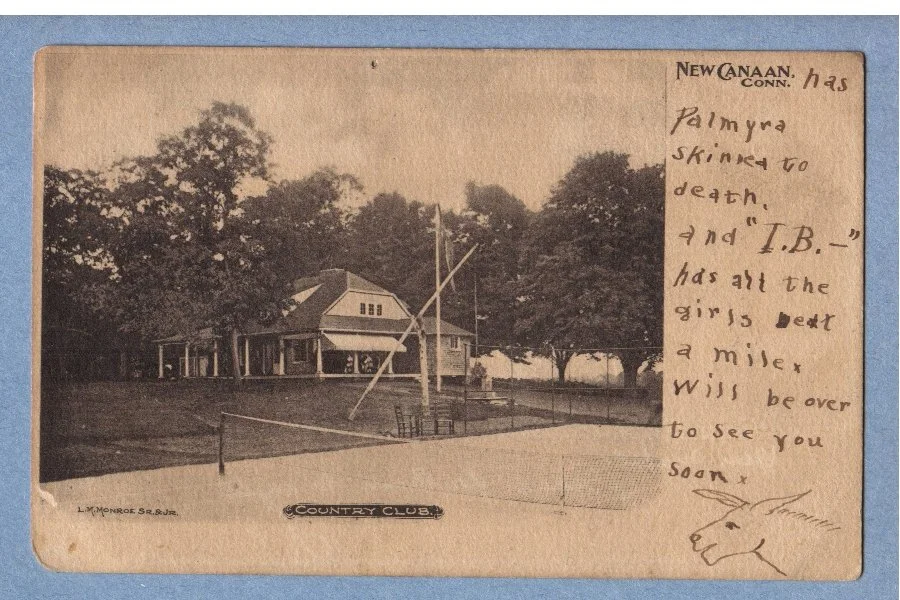

New Canaan Country Club circa 1906. Since the early 20th Century New Canaan has been an affluent New York City suburb.

The famed editor Maxwell Perkins (1884-1947) praised New Canaan, where he lived from 1924 to his death:

“{T}he charm of New Canaan, a New England village at the end of a single track railroad with almost wild country in three directions, i.e. wild to the Easterner. An ideal way for bringing up children in the way they should go, girls anyhow.”

Moffly Media noted in 2009:

“Max Perkins, who died sixty-two years ago this June, was the most important American literary figure that you may never have heard of. He wrote no books of his own; his daughters insisted he couldn’t spell or punctuate; and his rivals thought him unsophisticated. Yet as a book editor for Charles Scribner’s Sons, where he worked from 1914 until his death in 1947, he possessed a matchless internal compass about writers and writing, shepherding into print the great works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, Edmund Wilson, Ring Lardner and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.’’

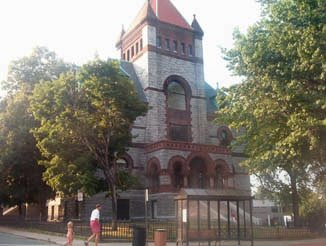

The Maxwell E. Perkins House, in New Canaan.

— Photo by Staib

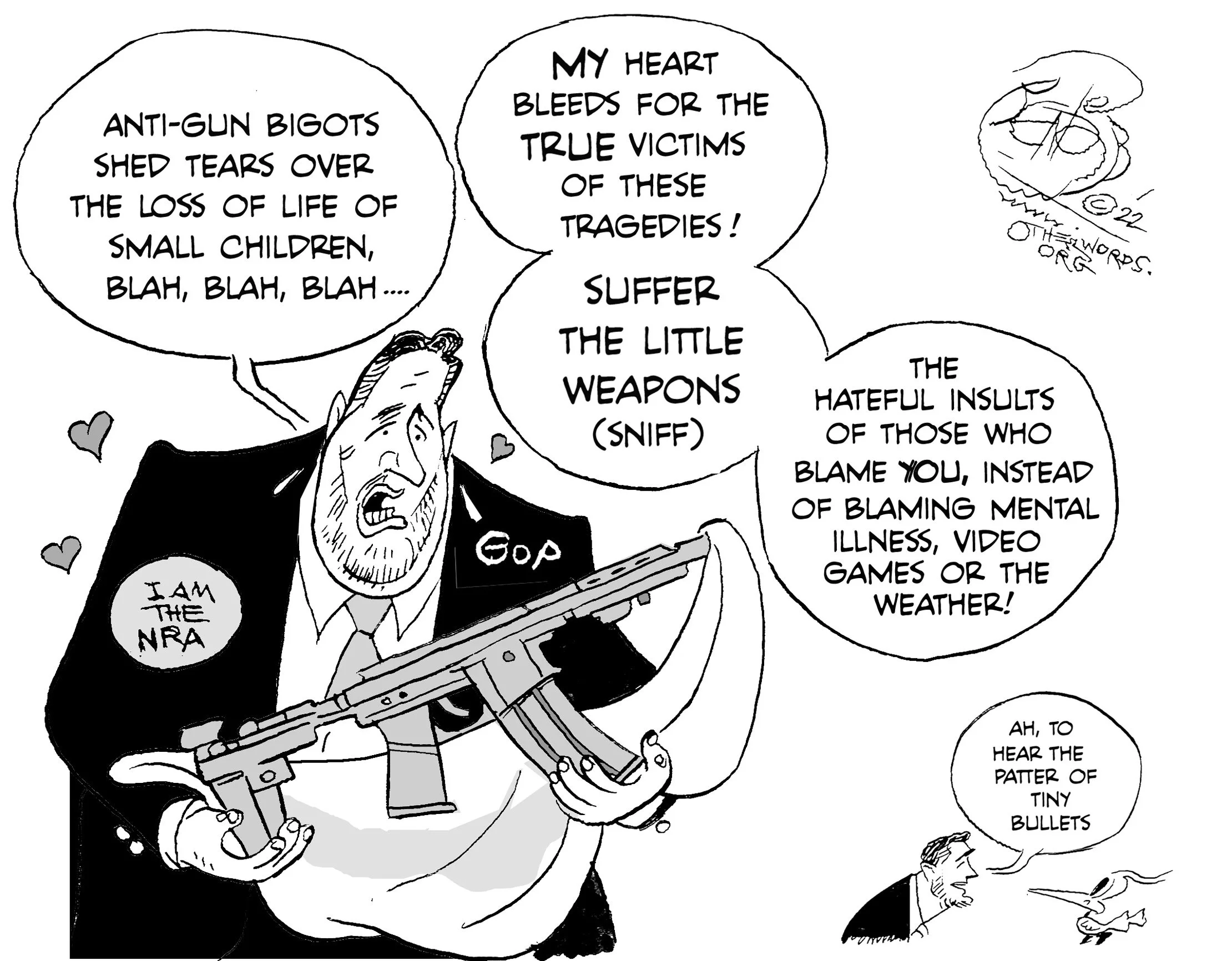

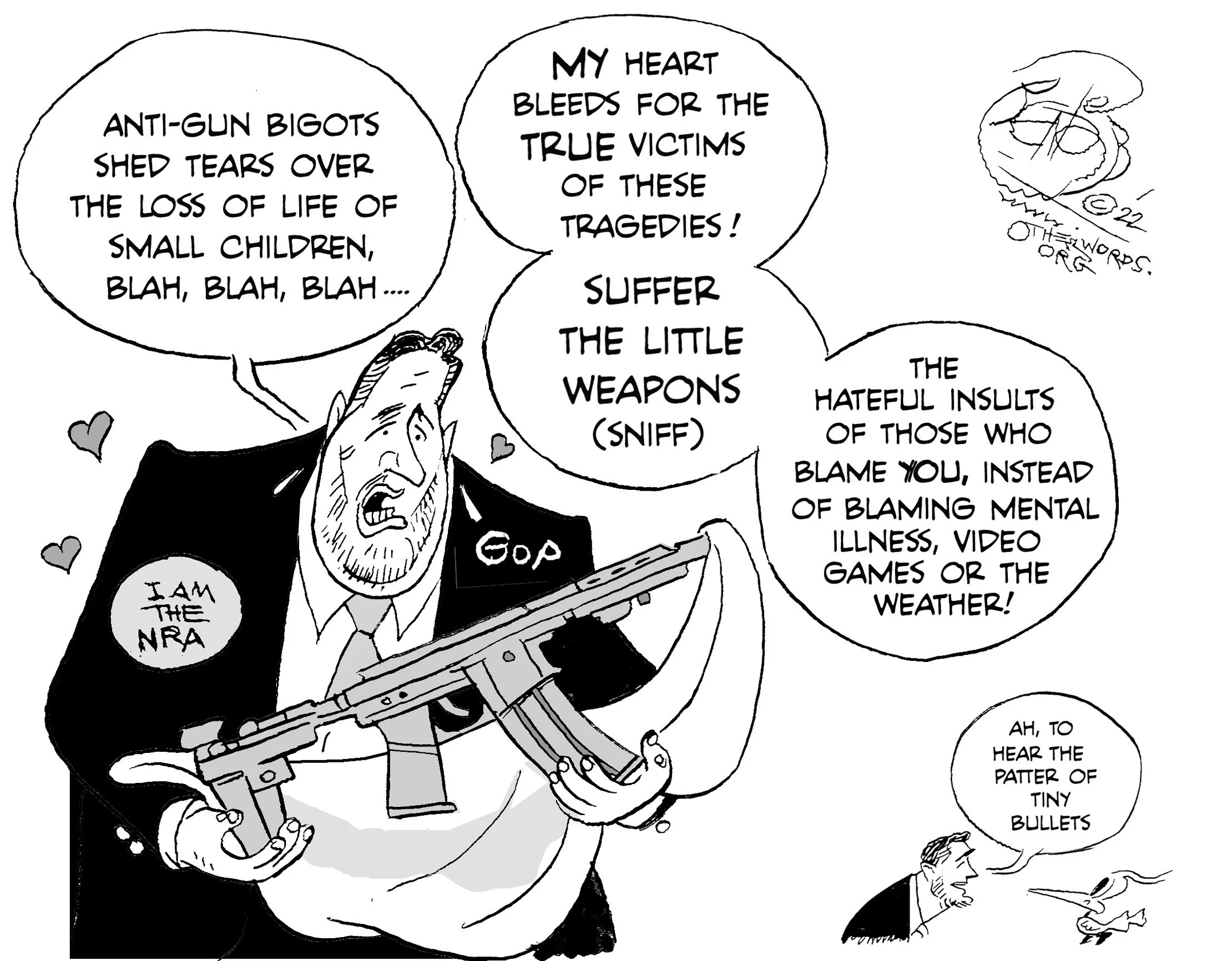

‘The true victims’

An AR-15-style rifle

— Photo by Picanox

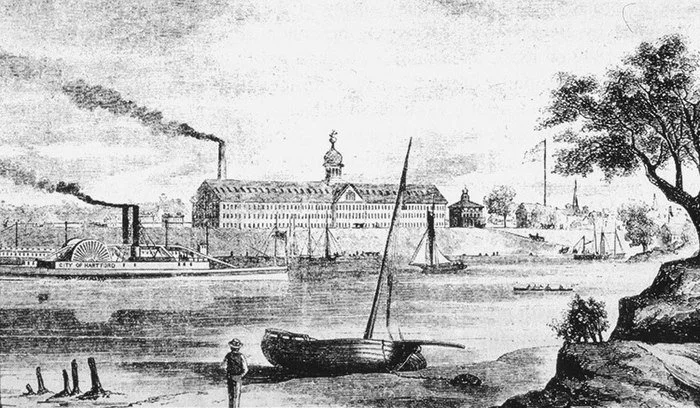

An AR-15-style rifle is any lightweight semi-automatic rifle based on the AR-15 design of Hartford, Conn.-based Colt’s Manufacturing Co., founded in 1855. It’s a favorite weapon of mass murderers.

Colt's Armory from an 1857 engraving, as viewed from the east side of the Connecticut River.

‘Oh what a town to get lost in’

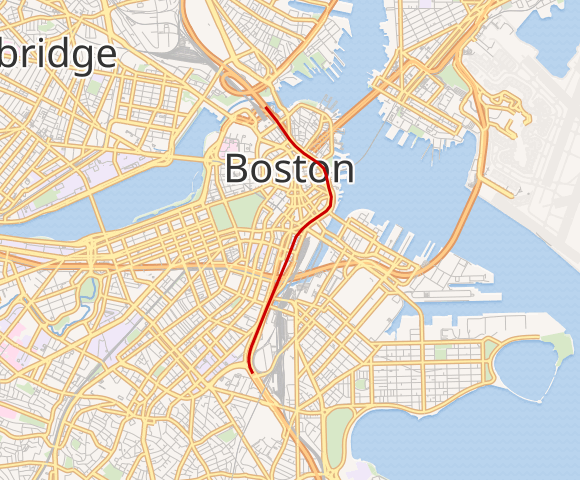

Central Artery is in red.

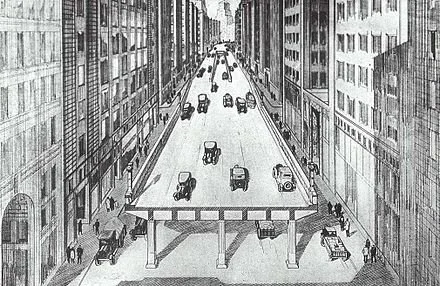

1920 plan for the Central Artery.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s May 22 “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I drove up through Boston to Medford, Mass., on May 22 to have dinner with a niece, her husband and their son (8) and daughter (11). I did so with some trepidation because Boston and its inner suburbs have such tangles of streets and bad/confusing/nonexistent signage that GPS often can’t handle it in any coherent way and maps on paper tend to be outdated. And indeed, it was tough to find the restaurant on the Fellsway.

“Boston, Boston, Boston/Oh what a town to get lost in” as an old song goes. I lived in the city in 1970-71, and had jobs there in the ‘60s, and it doesn’t seem to be less confusing than it was back then, whatever the grandeur and promises of the Big Dig projects.

Greater Bostonians, like Rhode Islanders, are infamous for bad driving – not signaling, accelerating without warning on the right, swerving and so on. But the former are worse because they commit these sins at higher speeds.

Having dinner with children, especially bright, engaging ones like the ones mentioned above is fun, but it’s always good to bring games and reading materials for them. Few things are as boring to children as being trapped at a table for a long meal with adults while impatiently awaiting dessert.

At Fenway: Robert Whitcomb (left), the Sox’ Wally mascot and Boston publisher David Jacobs before the May 20 Mariners game.

However confusing Boston is, I tip my hat to the efficiency of the Boston Red Sox. Boston’s biggest weekly paper, The Boston Guardian, on whose little board I sit, was being honored, with other community organizations, in a pre-game event on the field at Fenway Park, on May 20, just before a game with the Seattle Mariners. (Boston won.) I’ve rarely seen such smooth coordination in moving people (including me) onto and off the field for the photo ops, etc.

It was comforting – sort of -- to see the police snipers on the roof of the stadium, ready for a terrorist attack or just another deranged young man with an assault rifle he just bought at Walmart. “Aren’t you happy they’re up there?’’ one of the photographers said.

I had to head back to Providence before the game ended and so had to leave the fancy lounge in the nose-bleed section above Fenway’s stands before Sox and Boston Globe principal owner John Henry showed up and played the guitar for our little group. He’s become my hero for supporting bookstores.

Boston can be beautiful, if exasperating! I fondly remember from the ‘60s running around the still somewhat Dickensian “Hub’’ on job errands, many of which I’d volunteer for to get out of stuffy offices, first in a shipping company on the waterfront and then at the gritty tabloid newspaper the Record American. I’d go to the tiny local stock exchange to pick up the day’s trading records or to the glorious State House to get something from a politician or a bureaucrat and nip into an ice-cream shop (or, as they were often spelled then, shoppe) for myself and into tobacco stores to buy cigarettes and cigars for my older co-workers. Occasionally I’d pick up a bag of peanuts to feed the rapacious pigeons on the Boston Common.

I did most of this walking, which is far and away the best way to get around the city.

Dry clean only?

“Daily Embroidery (24 Days)” (pearl cotton on linen dyed with oak galls), by Amherst-based Bonnie Sennott, in the show “Bonnie Sennott: Abstract Embroidery and Watercolors,’’ at the Hosmer Gallery in the Forbes Library, Northampton, Mass.

The gallery says her work includes the "Daily Thread,’’ a yearlong project in which she embroidered daily using colors observed in nature as well as several of her “negative-space embroideries exploring absence, loss and the passing of time’’.

She’ll also show abstract watercolors on the theme of "stones and water," which she’s creating in the "100 days of creative acts" project organized by author Suleika Jaouad and the Isolation Journals."

The beautiful Romanesque Hampshire County Courthouse, in Northampton, built in 1884-1886.

Llewellyn King: Prepare for a summer of discontent but enjoy the sun anyway

Heading down to Crane Beach, in Ipswich, Mass.

— Photo by Thomas Steiner

Roller coaster at the Six Flags amusement park in Agawam, Mass. More political/geopolitical roller coaster rides coming.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

All the portents are that 2022 will be a summer to remember --and not in a good way.

It will be a summer of shortages, high prices, possible electric blackouts and severe and unpredictable storms. It also promises to be a summer of political ugliness, where civility and facts are missing.

National unity and cohesion, which usually can be expected in times of crisis, isn’t in sight. We are gracelessly at each other’s throats.

Also missing will be any sense that there is strong leadership anywhere; not in the White House, Congress, or among our allies.

Set these tribulations, caused by a dangerous war in Ukraine following on the COVID 19 pandemic, and you are entitled to be despondent. All this wasn’t in the playbook -- the events that shape the world never are.

But don’t reach for the arsenic. For most of us, glorious summer, so important to the North American lifestyle, will be as it always is with crowded beaches, jammed highways, chaotic airports and painful sunburn. We will have summer; and summer will have its joys, its rituals, and its happiness.

For Americans, these aren’t the worst of times. They are just very trying times. We will feel them directly in the wallet, painfully so. Gasoline and other fuels will be very expensive, and heating oil will be a big-ticket item next winter. House prices are still stratospheric, and rents are going up. The markets are shaky.

Americans are feeling that all isn’t well and that things are coming unstuck -- reliable, everyday things.

In democracies, we seek relief by changing the government. All the indications are that we will do that in the midterm elections just months away.

The Democrats are likely to take a drubbing. The Republicans will joyfully seize victory – and they won’t know any better what to do about the great stresses that are shaking the nation and the world.

Instead, they will be tempted to double down on social issues and a raft of things that will exacerbate the divisions in the country, further curb the rights of women, mess with education curricula, seek to influence social media platforms, and keep the government firmly in gridlock.

President Biden and his unlucky administration will get the blame if the Democrats are routed in the midterms. Indeed, it should, fairly or not, even though the alternative may not be better.

Certainly, a Democratic White House and Republican Congress suggests just one thing: crippling inaction.

Biden hasn’t been a proactive president but a reactive one. He has waited for the water to rise before he has acknowledged that it is happening, and it is time to start bailing.

Take, for example, the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. When Biden tried to get ahead of the news, to identify an issue and resolve it before it mugged him, he got it terribly wrong. It was a foreign-policy calamity of Biden’s making, and it seems to have curbed his enthusiasm for preempting issues.

Mostly, Biden has sought to balance things. His reaction to outrageousness is a sedate, genteel sense of horror. You expect him to say to the Supreme Court, or the gun lobby, or Russian Vladimir Putin, “Look what you have done!”

One gets the feeling that Biden doesn’t have a grip on much except his decency. Everyone who knows him will tell you what a decent man he is. Decency supports, but it doesn’t lead. Decency isn’t a policy. It isn’t a way forward. It isn’t a solution.

After the midterms, Congress likely will be in the hands of two ruinous vacillators, Sen. Mitch McConnell, of Kentucky, and the even more wobbly Rep. Kevin McCarthy, of California. They aren’t exemplars of the Republican ideal. They aren’t in the previously worshipped Ronald Reagan tradition.

Both have shown themselves captive to former President Trump’s vengeful malevolence and have twisted the truth in their servitude to him.

Politics are sour, prices high, the future bumpy, but summer is glorious. Revel in it, celebrate it, and bask in its untroubled rays. I plan to do just that. Thoughts of politics are worse than sunburn.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Brian Wakamo: A legal victory for America’s most dominant pro-sports team

A ticker tape parade in Manhattan celebrating the U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team’s 2015 World Cup victory.

Via OtherWords.org

Three years ago, the U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team filed a $24 million gender-discrimination lawsuit against the U.S. Soccer Federation. This May, after a prolonged and public battle, the players association for the U.S. women’s and men’s national teams negotiated a groundbreaking collective bargaining agreement.

The agreement enshrines a number of new protections for both teams. But most importantly, the agreement creates equal pay structures and requires the U.S. Soccer Federation to share World Cup prize money equally between both the men and women’s national teams.

It’s a first for any soccer federation in the world — and an inspiring victory for fairness in any industry.

Consider the women’s team’s impressive record — which includes four World Cup wins, four Olympic gold medals, and FIFA’s world No. 1 ranking for five straight years. The men’s team, by comparison, failed to qualify for the World Cup in 2018 and hasn’t made the quarterfinals or better in the World Cup since 2002.

Under the previous rules, had the men’s team qualified in 2018, they would have likely received first-round exit prize money worth $8 million — double what the women’s team took home for winning the 2019 Women’s World Cup.

Now the two teams will get equal pay for equal success.

This agreement would not have been possible without decades of tireless activism from players who have decried the double standards present in U.S. and global soccer.

Whether it was turning their warm-up jerseys inside out to obscure the U.S. Soccer Federation crests or kneeling in support of racial justice, the U.S. women’s team embodies a culture of protest that reflects the ongoing struggles of women and marginalized groups across the world.

It’s not hard to see the parallels in the broader economy.

Men, for example, make up an overwhelming majority of top earners across the U.S. economy, even though women now represent almost about the country’s workforce. At the top 0.1 percent level, women make up only 11 percent.

But there’s another important parallel in how the teams corrected this imbalance: unions.

This equal pay for equal success victory could not have been achieved without the collective strength and solidarity that a union provides. By coming together in their contract negotiations, the men’s and women’s teams both inspire and benefit each other.

In the latest collective-bargaining agreement, for example, athletes on the men’s national team will now have access to paid child care, a benefit the women’s team has enjoyed for over 25 years. This agreement is a testament to how everyone can win when you fight for those at the bottom.

Even beyond soccer and beyond the United States, the contract is groundbreaking.

It provides a roadmap to equity for other national sports teams, like basketball and hockey, which face similar challenges. It could also be replicated in places like France or Germany, where teams have an even higher level of success and larger budgets than the U.S. Soccer Federation.

But it’s also a roadmap for those of us who aren’t professional athletes.

As unionization efforts take flight at Starbucks, Amazon, and other big, profitable employers, America’s most dominant national sports team is showing how the workers who make companies successful can claim their fair share of the rewards.

Goal!

Brian Wakamo is an Inequality Research Analyst at the Institute for Policy Studies and a co-editor of Inequality.org.

Michelle Andrews: In N.H., a painful and confusing colonoscopy medical bill

Lake Sunapee, part of which is in the town of Sunapee, where Elizabeth Melville lives.

‘Elizabeth Melville and her husband are gradually hiking all 48 mountain peaks that top 4,000 feet in New Hampshire.

“I want to do everything I can to stay healthy so that I can be skiing and hiking into my 80s — hopefully even 90s!” said the 59-year-old part-time ski instructor who lives in the vacation town of Sunapee.

So when her primary-care doctor suggested she be screened for colorectal cancer in September, Melville dutifully prepped for her colonoscopy and went to New London Hospital’s outpatient department for the zero-cost procedure.

Typically, screening colonoscopies are scheduled every 10 years starting at age 45. But more frequent screenings are often recommended for people with a history of polyps, since polyps can be a precursor to malignancy. Melville had had a benign polyp removed during a colonoscopy nearly six years earlier.

Melville’s second test was similar to her first one: normal, except for one small polyp that the gastroenterologist snipped out while she was sedated. It too was benign. So she thought she was done with many patients’ least favorite medical obligation for several years.

Then the bill came.

The Patient: Elizabeth Melville, 59, who is covered under a Cigna health plan that her husband gets through his employer. It has a $2,500 individual deductible and 30% coinsurance.

Medical Service: A screening colonoscopy, including removal of a benign polyp.

Service Provider: New London Hospital, a 25-bed facility in New London, N.H. It is part of the Dartmouth Health system, a nonprofit academic medical center and regional network of five hospitals and more than 24 clinics with nearly $3 billion in annual revenue.

Total Bill: $10,329 for the procedure, anesthesiologist and gastroenterologist. Cigna’s negotiated rate was $4,144, and Melville’s share under her insurance was $2,185.

What Gives: The Affordable Care Act made preventive health care such as mammograms and colonoscopies free of charge to patients without cost sharing. But there is wiggle room about when a procedure was done for screening purposes, versus for a diagnosis. And often the doctors and hospitals are the ones who decide when those categories shift and a patient can be charged — but those decisions often are debatable.

Getting screened regularly for colorectal cancer is one of the most effective tools that people have for preventing it. Screening colonoscopies reduce the relative risk of getting colorectal cancer by 52% and the risk of dying from it by 62%, according to a recent analysis of published studies.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, a nonpartisan group of medical experts, recommends regular colorectal cancer screening for average-risk people from ages 45 to 75.

Colonoscopies can be classified as for screening or for diagnosis. How they are classified makes all the difference for patients’ out-of-pocket costs. The former generally incurs no cost to patients under the ACA; the latter can generate bills.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has clarified repeatedly over the years that under the preventive services provisions of the ACA, removal of a polyp during a screening colonoscopy is considered an integral part of the procedure and should not change patients’ cost-sharing obligations.

After all, that’s the whole point of screening — to figure out whether polyps contain cancer, they must be removed and examined by a pathologist.

Many people may face this situation. More than 40% of people over 50 have precancerous polyps in the colon, according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Someone whose cancer risk is above average may face higher bills and not be protected by the law, said Anna Howard, a policy principal at the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network.

Having a family history of colon cancer or a personal history of polyps raises someone’s risk profile, and insurers and providers could impose charges based on that. “Right from the start, [the colonoscopy] could be considered diagnostic,” Howard said.

In addition, getting a screening colonoscopy sooner than the recommended 10-year interval, as Melville did, could open someone up to cost-sharing charges, Howard said.

Coincidentally, Melville’s 61-year-old husband had a screening colonoscopy at the same facility with the same doctor a week after she had her procedure. Despite his family history of colon cancer and a previous colonoscopy just five years earlier because of his elevated risk, her husband wasn’t charged anything for the test. The key difference between the two experiences: Melville’s husband didn’t have a polyp removed.

Resolution: When Melville received notices about owing $2,185, she initially thought that it must be a mistake. She hadn’t owed anything after her first colonoscopy. But when she called, a Cigna representative told her the hospital had changed the billing code for her procedure from screening to diagnostic. A call to the Dartmouth Health billing department confirmed that explanation: She was told she was billed because she’d had a polyp removed — making the procedure no longer preventive.

During a subsequent three-way call that Melville had with representatives from both the health system and Cigna, the Dartmouth Health staffer reiterated that position, Melville said. “[She] was very firm with the decision that once a polyp is found, the whole procedure changes from screening to diagnostic,” she said.

Dartmouth Health declined to discuss Melville’s case with KHN even though she gave her permission for it to do so.

After KHN’s inquiry, Melville was contacted by Joshua Compton, of Conifer Health Solutions, on behalf of Dartmouth Health. Compton said the diagnosis codes had inadvertently been dropped from the system and that Melville’s claim was being reprocessed, Melville said.

Cigna also researched the claim after being contacted by KHN. Justine Sessions, a Cigna spokesperson, provided this statement: “This issue was swiftly resolved as soon as we learned that the provider submitted the claim incorrectly. We have reprocessed the claim and Ms. Melville will not be responsible for any out of pocket costs.”

The Takeaway: Melville didn’t expect to be billed for this procedure. It seemed exactly like her first colonoscopy, nearly six years earlier, when she had not been charged for a polyp removal.

But before getting an elective procedure like a cancer screening, it’s always a good idea to try to suss out any coverage minefields, Howard said. Remind your provider that the government’s interpretation of the ACA requires that colonoscopies be regarded as a screening even if a polyp is removed.

“Contact the insurer prior to the colonoscopy and say, ‘Hey, I just want to understand what the coverage limitations are and what my out-of-pocket costs might be,’” Howard said. Billing from an anesthesiologist — who merely delivers a dose of sedative — can also become an issue in screening colonoscopies. Ask whether the anesthesiologist is in-network.

Be aware that doctors and hospitals are required to give good faith estimates of patients’ expected costs before planned procedures under the No Surprises Act, which took effect this year.

Take the time to read through any paperwork you must sign, and have your antennae up for problems. And, importantly, ask to see documents ahead of time.

Melville said that a health system billing representative told her that among the papers she signed at the hospital on the day of her procedure was one saying that if a polyp was discovered, the procedure would become diagnostic.

Melville no longer has the paperwork, but if Dartmouth Health did have her sign such a document, it would likely be in violation of the Affordable Care Act. However, “there’s very little, if any, direct federal oversight or enforcement” of the law’s preventive services requirements, said Karen Pollitz, a senior fellow at KFF.

In a statement describing New London Hospital’s general practices, spokesperson Timothy Lund said: “Our physicians discuss the possibility of the procedure progressing from a screening colonoscopy to a diagnostic colonoscopy as part of the informed consent process. Patients sign the consent document after listening to these details, understanding the risks, and having all of their questions answered by the physician providing the care.”

To patients like Melville, that doesn’t seem quite fair, though. She said, “I still feel asking anyone who has just prepped for a colonoscopy to process those choices, ask questions, and potentially say ‘no thank you’ to the whole thing is not reasonable.”

Michelle Andrews is a Kaiser Health News reporter. @mandrews110

David Warsh: Of financial revolutions

The Prince of Orange landing at Torbay, England, in the Glorious Revolution that overthrew James II and installed the Prince of Orange, a Dutchman, as William III.

— Painting by Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Many people at least a little about the history of the scientific revolutions of the 16th and 17th centuries; the industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries; and the democratic revolutions of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Very few are familiar with the major details of the financial revolution of the early 18th Century, which began with the reforms of England’s “Glorious revolution” of 1688. In the course of the next sixty years, these developments brought into existence the modern military-industrial complex.

This relative obscurity of these long-ago events is not surprising, for, as best I can tell, the term had no currency before Peter G.M Dickson, in 1967, published The Financial Revolution in England: A Study of the Development of Public Credit, 1688-1756. Until then, the power to spend public money was colloquially described as “the control of the purse.”

It is, however, something of a shame, since what we now call “the national debt” these days is the engine that powers military interventions around the world, from the misadventures of the George W, Bush administrations forays in Afghanistan and Iraq to Vladimir Putin’s quagmire plunge in Ukraine. You can’t fathom those periodic $60 billion appropriations bills without knowing something about the enormous multinational purse that supports NATO.

Instead, our understanding of these matters depends on combinations of vignettes and modern analysis, a sauce that often doesn’t come together.

Among vignettes, an especially appealing recent example is Ways and Means: Lincoln and his Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, by social historian Roger Lowenstein. It relates how Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, Lincoln’s defeated presidential rival, turned the tide of war against the South on the financial front, “levying taxes and marketing bonds, while desperately batting inflation.” A more encompassing account of government bond markets was related twenty-five years ago and updated in 2010 in Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt, by John Steele Gordon.

A welcome addition among analytics In Defense of Public Debt, by Barry Eichengreen, Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves, and Kris James Michener (2021), a hard-headed survey of debt in the service of the state and what’s known about the limits of borrowing. The wind has largely gone out of the sails of the fad called “modern monetary theory,” thanks to books like this, and the papers cited herein. And the book synthesizes a good deal of valuable history. But the topical treatment of the issues is unlikely to make an impression on the broad public mind. That take a lifetime of research in the manner of Dickson, or, in the case of the cadre of researchers working over insights derived from a famous 1989 article about the origins of modern democracy, by Douglass North and Barry Weingast.

Thus the lack of understanding is of the financial revolution is to some degree the story of a lost book. Dickson died last year, having spent sixty years as a Founding Fellow of St. Catherine’s College, Oxford University. He revised his English Financial Revolution book in 1993, but that second edition is out of print. Even the library copy of the original was missing when I arrived yesterday. You can get some idea of the scope of the problem from its table of contents — and why the story of government bond markets is a hard tale to tell.

The Financial Revolution — 2. The Contemporary Debate — II. Government Long-Term Borrowing — 3. The Earliest Phase of the National Debt 1688-1714 — 4. Problems of Administration and Reform 1693-1719 — 5. The South Sea Bubble (I) — 6. The South Sea Bubble (II) — 7. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 8. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 9. The National Debt under Walpole – 10. War and Peace 1739-1755 — 11. Public Creditors in England and Abroad– 12. Public Creditors Abroad – 12. Government Short-term Borrowing — 13. Borrowing by Exchequer Tallies — 14. Borrowing by Exchequer Bills — 15. Departmental Credit — 16. The Bonds of the Monied Companies — 17. The Ownership of Short-dated Securities and the Market in Securities — 18. The Turnover of Securities — 19. The Rate of Interest in Theory and Practice — 20. The Origins of the Stock Exchange

A parallel history of events in France adds dimensionality to the story. French Finances, 1770-1795; From Business to Bureaucracy (1970), by John F. Bosher, describes role of the French Revolution in transforming a thoroughly corrupt system of government finance into a less venal and more efficient system. In A Financial History of Western Europe (1993), Charles P. Kindleberger, who assigned the two books in courses he taught in 1979 and 1980, wrote, “Note that the financial revolution of England preceded that of France by a century, and that the view that British military success owed to her financial capacity is matched by the statement that financial incompetence of the French monarchy was the main reason for its ultimate collapse.”

The good news is that not one but two top-flight economic historians are once again working on telling the story of the revolution charted by Dickson fifty years ago. Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution 1688-1720, by Carl Wennerlind, of Barnard College, at Columbia, was under-appreciated when it appeared ten years ago. The author bent over backwards to avoid triumphalism by incorporating, as the financial revolution’s first great success, the story of Britain’s entry into the Atlantic slave trade – the usually glossed-over precipitant and still-less-remembered outcome of the South Sea Bubble.

Anne L. Murphy, of the University of Portsmouth, who spent twelve years working trading interest-rate and foreign-exchange derivatives in the City of London, re-tooled as a historian and published The Origins of English Financial Markets: Investment and Speculation before the South Sea Bubble in 2009. The book won the Economic History Society’s best monograph prize the next year. She is preparing to publish Virtuous Banking: a day in the life of the late eighteenth-century Bank of England.

Meanwhile, Wennerlind’s new book, A Philosopher’s Economist: Hume and the Rise of Capitalism, co-authored with Margaret Schabas, of the University of British Columbia, appears next month. The financial revolution of the eighteenth century is with us every day. The extent and significance of its evolution has yet to be fully spelled out to a 21st Century audience.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Chris Powell: Conn. Democrats' silly obsessions are bringing back ticket balancing

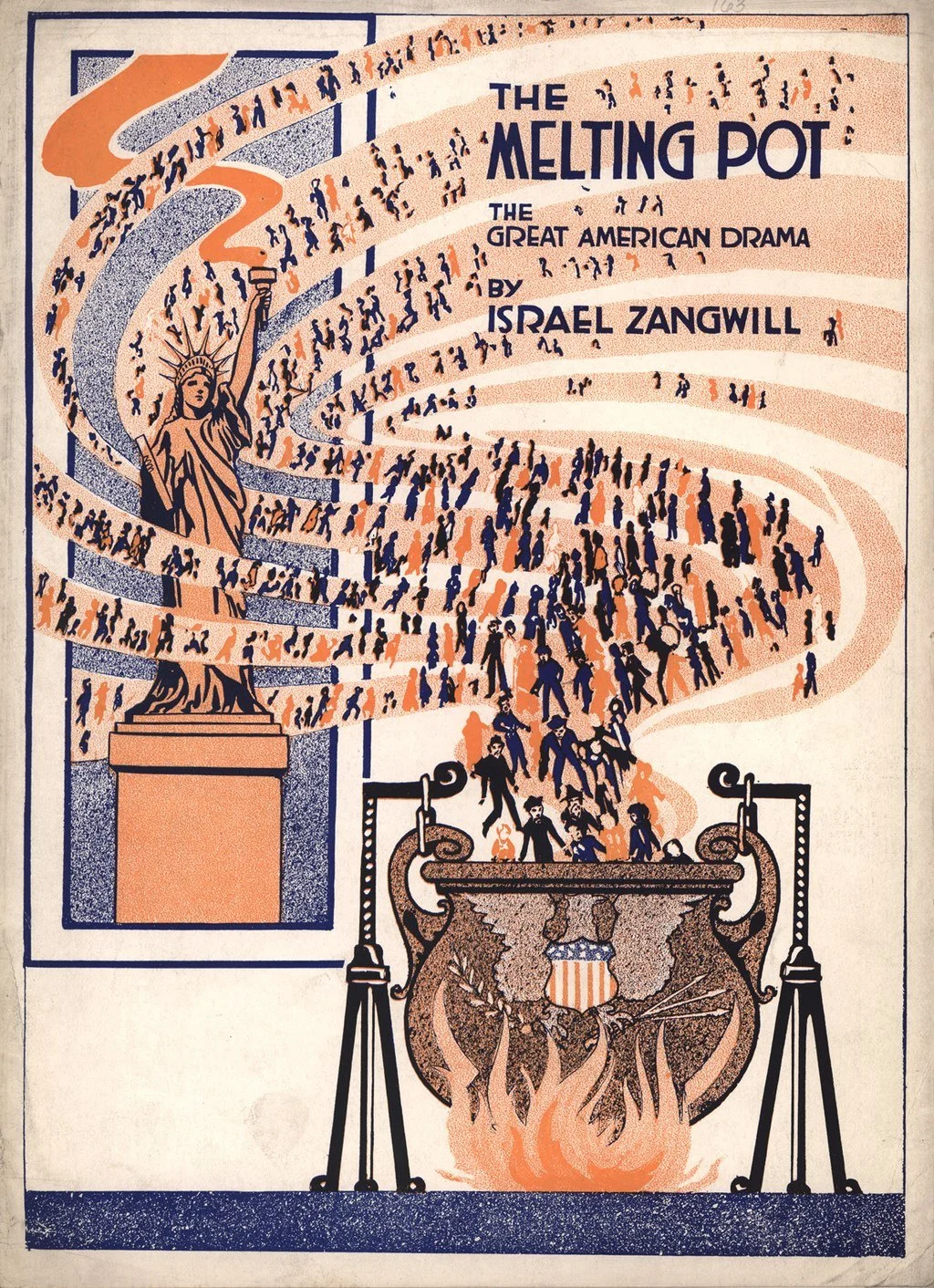

The image of the United States as a melting pot was popularized by the 1908 play The Melting Pot. Has the melting cooled?

MANCHESTER, Conn.

As recently as 50 years ago Connecticut politics still had traces of the old ethnic, racial and religious resentments and rivalries that had arisen through the state's long history, resentments and rivalries that political party state tickets tried to assuage.

Yankee Protestant Republicans scorned immigrant Catholics. While the Irish and Italians both were mostly Catholic, they were also tribal and often found something to dislike about each other, so much so that many Italians became Republicans just because the Irish, having arrived first and been scorned by the Yankee Protestant Republicans, had come to dominate the Democratic Party.

The state's Blacks started leaning Democratic during the New Deal years but race remained the state's biggest prejudice so they didn't get much patronage for their political involvement, and for a long time they were glad just not to be actively oppressed.

Jews were an afterthought in Connecticut politics until Abraham Ribicoff got elected to Congress as a Democrat from the Hartford district in 1948 and came back from defeat for re-election in the Republican landslide of 1952 to run for governor in 1954. Ribicoff ran into what was said to be a whispering campaign targeting him for his religion, so he went on television near Election Day to extol the American dream and his right to aspire to it despite his modest Jewish origins in New Britain. The tactic worked, gaining Ribicoff a small plurality, and it may have been the moment when Connecticut began to grow up a little politically, to start looking past the ethnic, racial and religious prejudices and irrelevancies.

Still, ticket balancing along ethnic, racial and religious lines continued in both parties for a few decades.

For some reason back then both parties tended to reserve their congressman-at-large nominations for a Pole, and when, at the Democratic State Convention in 1962, the Democratic incumbent, Frank Kowalski, stomped out in resentment over being denied a primary for the U.S. Senate nomination, party power broker John M. Bailey, who was both state and national Democratic chairman, urgently sought another candidate with a Polish name.

Bailey found a prospect in the Bristol delegation, a little-known municipal official and war veteran, Bernard F. Grabowski. The legend is that Bailey asked Grabowski three questions:

Are you Polish? Are you Catholic? Can you speak Polish?

When Grabowski answered affirmatively, the Democrats had their nominee and Connecticut its next congressman-at-large.

But amid the national political turmoil of the late 1960s, ticket-balancing was getting in the way of the ambitions of too many state politicians, and after Bailey, the master of machine politics, died, in 1975, there was no one skilled and inclined enough to keep ticket balancing going as ethnicity and race were fading as focal points of life.

Indeed, in the following several decades Connecticut began to think itself somewhat more enlightened for its growing indifference to the ancestry and religion of political candidates and its increasing concern for positions, skills, and character.

But now the state may be regressing, at least to judge by the recent Democratic State Convention, where the party's silly renewed obsession with race and other characteristics irrelevant to the performance of public office targeted nominations for two spots on the state ticket where no incumbents were seeking re-election.

Connecticut Democrats still seem to think that the Connecticut Constitution requires the treasurer's office to be filled by a Black person and the secretary of the state's office by a woman. The party's nominee for secretary this time is not just female but Black as well. Both nominees may do a good job if elected, but they are little known and almost certainly would not have been chosen if they did not provide the racial composition the convention sought.

Of course, few voters may care much about who fills the treasurer and secretary positions, and even with Connecticut Democrats diversity goes only so far. For their ticket's top positions, the ones with the greatest power over policy and patronage -- governor and lieutenant governor -- have gone again to whites, and somehow the ticket apparently lacks a transgender candidate, an oversight that may embarrass the party's most hysterical members.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Don’t stare at it

“Openwork Wedjat Eye” (polychrome faience) (ancient Egyptian, about 1076–655 BCE) at the Worcester Art Museum, opening June 18.

The museum (very impressive for a mid-size city) says:

“The magnificence of ancient Egypt comes to life through jewelry, the most precious and personal of human possessions.’’

Tongue-in-cheek arrogance or the real thing?

Sterling Memorial Library at Yale, in New Haven.

“The Yale president must be a Yale man. Not too far to the right, or too far to the left or a middle-of-the-roader. Ready to give the ultimate word on every subject under the sun from how to handle the Russians to why undergraduates riot in the spring. Profound with a wit that bubbles up and brims over in a cascade of brilliance. You may have guessed who the leading candidate is, but there is a question about him: Is God a Yale man?”

-- Wilmarth S. Lewis (1895-1979), Yale trustee, writer and near-monomaniac collector of the works of Horace Walpole (1717-1787), the British writer. He graduated from Yale in 1918. (He made the remarks above in 1950.)

In 1928 he married Anne Burr Auchincloss, a granddaughter of Oliver B. Jennings, one of the founders of the Standard Oil Company. Mrs. Lewis was also caught up in the Walpole pursuit and devoted her fortune and much time to it until her death, in 1959. Most of their collection was left to Yale.

Irritating and beautiful

New growth and pollen cones of a pitch pine, a common tree on Cape Cod. It’s very flammable.

— Photo by Famartin

“Now I know summer is here, no matter how cold it is at night, for when I went out to the car this morning, the windshield was dusted with orange and the whole shiny dark blue of the body was powdered. The pine pollen has come! This is a thick, almost oily deposit that penetrates everything. If you close a room and lock the windows, the sills will be drifted with the pollen the next morning. The floors turn orange.’’

— Gladys Taber, in My Own Cape Cod (1971)

Moisture maniacs

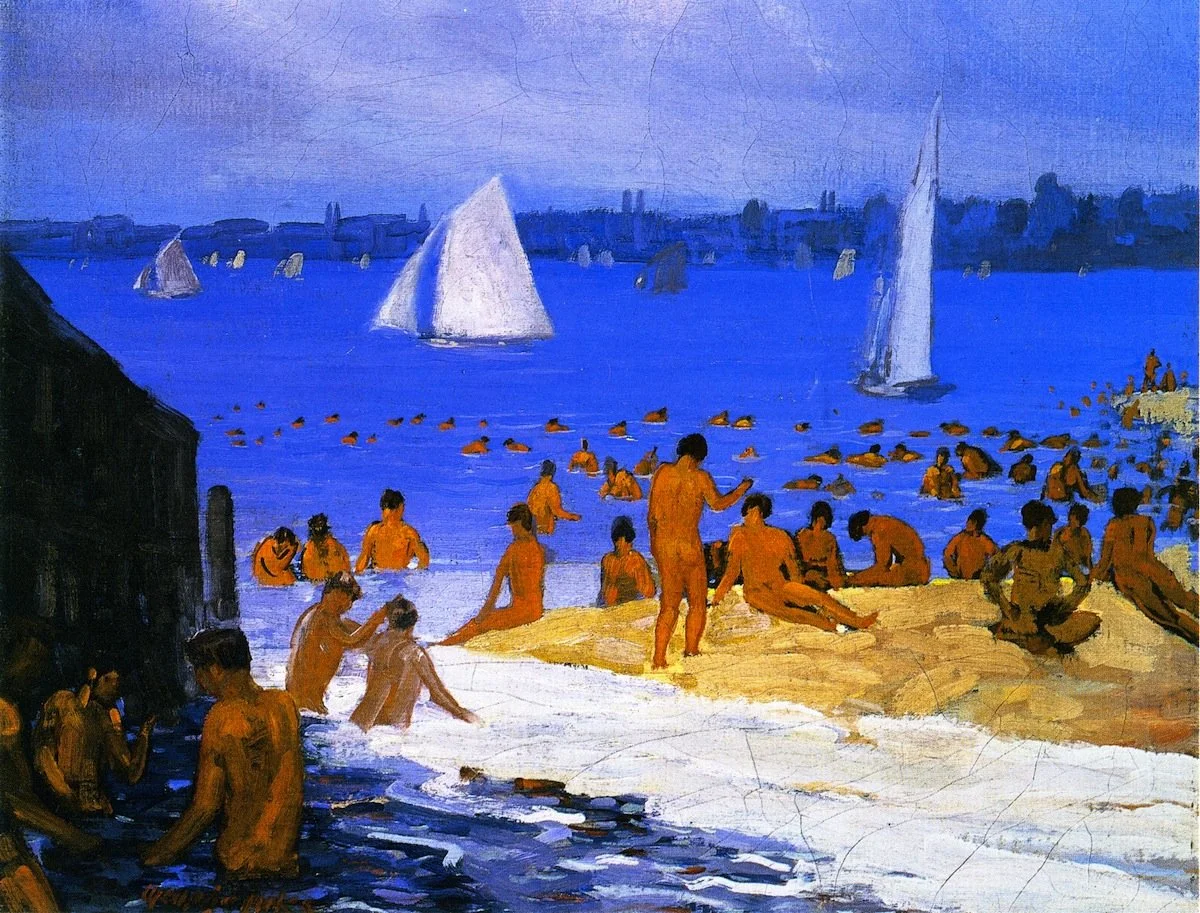

‘‘Adult Swim” (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb

“L Street Brownies’’ (swimming club in South Boston) (1922), by George Luks (1867-1933). Open-air nudity in 1922?!

Ready for it now

“Give me back the long heat wave, the sweat dripping

from eyelashes, the stained blouses, the black windows,

the spiders dangling from their silver bridges,

the wasps lighting on the branches of the cedar bushes

as they waited for me to make a dash for the screen door.’’

— From “The Long Heat Wave,’’ by Jeff Friedman, a poet and professor based in West Lebanon, N.H.

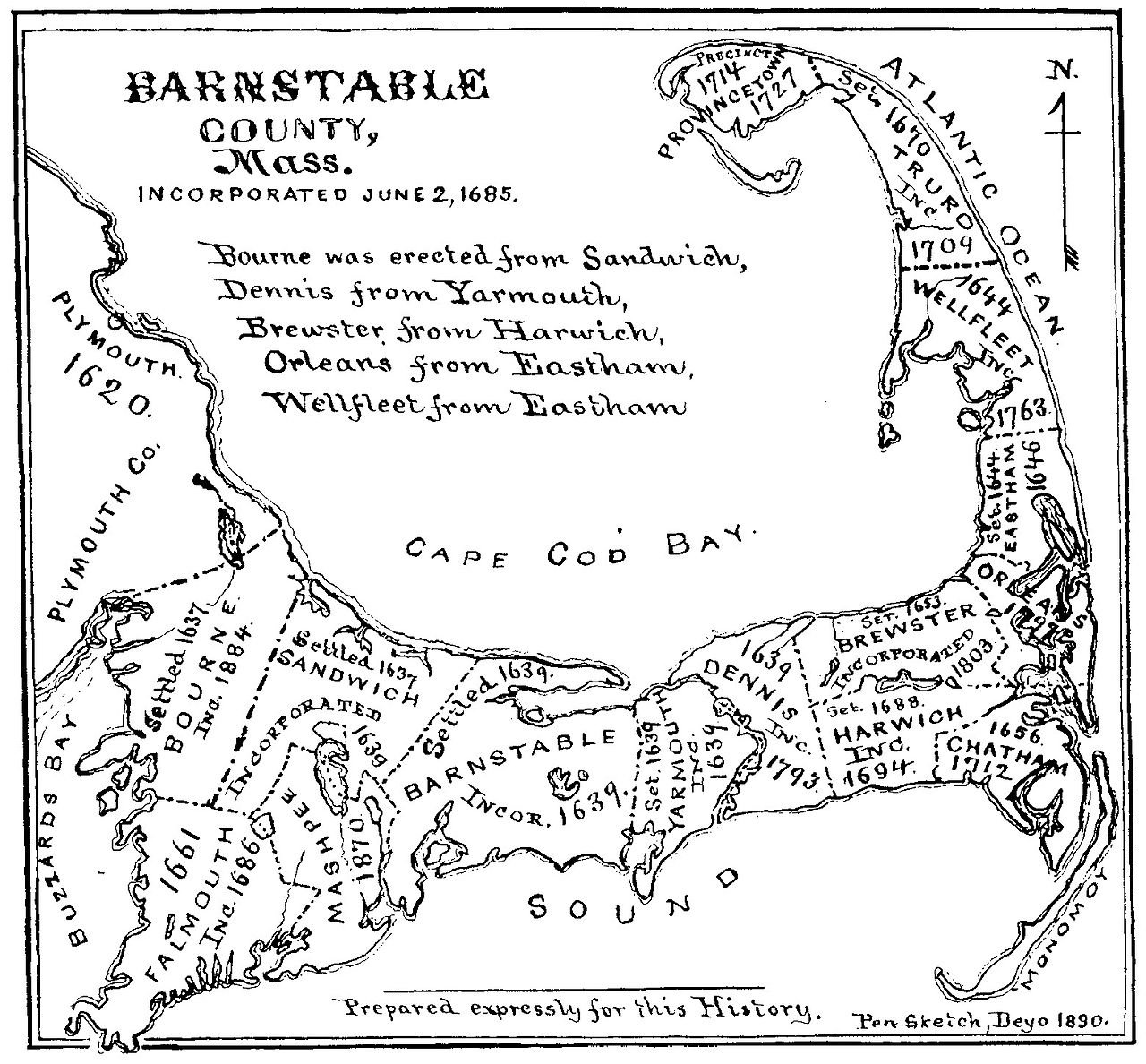

1889 map