Confident and vulnerable in Trumpian orange

“Self” (mixed media), by Laura Harper Lake, in her show “Vivid and Vulnerable Vessels,’’ at Foundation Art Space, , N.H., June 3 through June 25.

She says: “The human form can receive varying reactions when a person views themselves with a self-assessing mind. At times we may be confident, much like the bold, vivid colors on my canvases, which are all wood. In other moments, we may feel like the thin layer of iridescent paint I use; vulnerable, exposing the natural grain beneath, and hesitant. I am a pendulum, swinging between these two radically different states of being.”

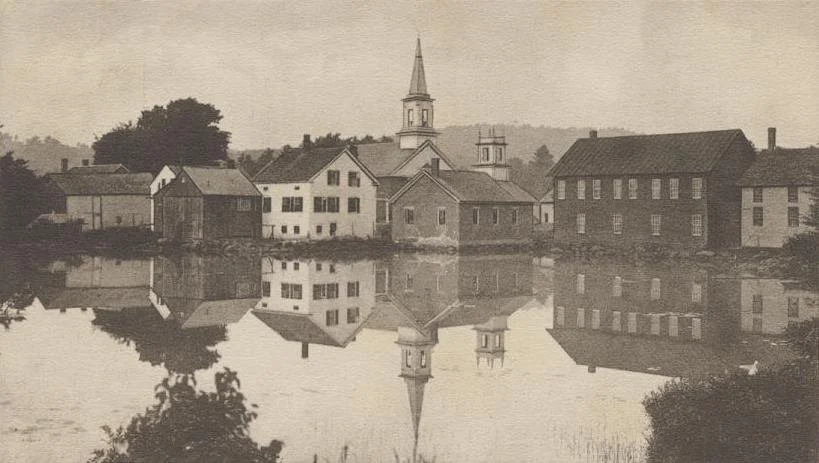

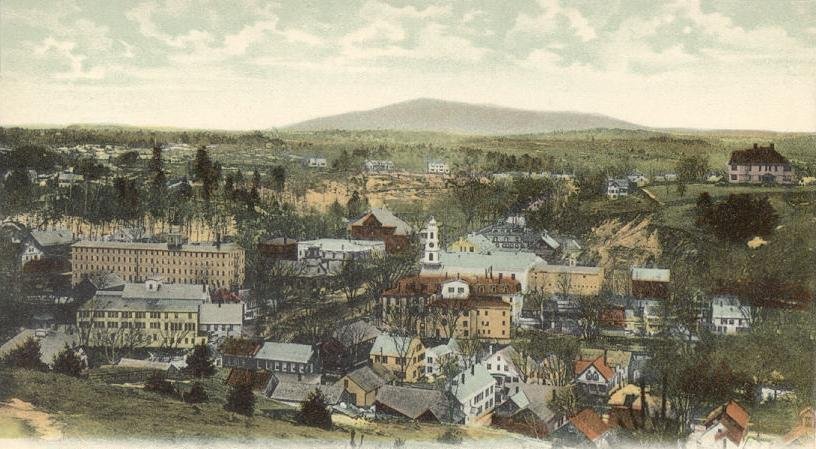

Exeter’s Squamscott Falls in 1907. The town has long hosted manufacturing enterprises, much of them originally powered by water power, but it’s best known as the home of Phillips Exeter Academy, the prep school.

'Into the moonlit woods'

“We climb into the cellar hole

of the old Bailey place

that caught fire in the middle

of the night, the seven children

who raced into the moonlit woods

in weightless clothes gowns and bedclothes’’

— From “Into the Forest,’’ by Anna Birch (1970), reflecting her experiences as a child in Hollis, N.H.

‘Strange ancient memories’

Harrisville, N.H. in 1905

— From H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), writer and a Providence native who’s known for his horror and science-fiction stories.

Free lunch

“In the Clover” (watercolor), by Jeanette Fournier, a North Woodstock, N.H., painter.

Woodstock Inn Brewery, in North Woodstock

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Oh come on! There were others

Bedford(N.H.) Presbyterian Church

“We had no religion at all, but we were Jews in New Hampshire, and my sister – who is now a rabbi – said it best: We were, like, the only Jews in Bedford, New Hampshire, as well as the only Democrats, so we just kind of associated those two things together. My dad raised us to believe that paying taxes is an honor.”

— Roseanne Barr (born 1952), American comedian and actress

Mountainous conception

Part of Avon Mountain, in Connecticut. It’s known for its microclimate.

“The night you were conceived

your father drove up Avon Mountain {near Hartford}

and into the roadside rest

that looked over the little city,

its handful of scattered sparks.’’

— From “Breaking Silence — For My Son,’’ by Patricia Fargnoli (1937-2021), an American poet and psychotherapist. She grew up in Connecticut and later moved to Walpole, N.H. (best known as the home of TV history-documentary maker Ken Burn’s Florentine Films) and on the Connecticut River. She was the New Hampshire Poet Laureate from December 2006 to March 2009.

Walpole’s public library in 1906. The famous and highly literary and reformist Alcott family, connected to the Concord, Mass.-based Transcendentalists, lived there for a time in the 1850s, as have other writers and painters, drawn by the region’s great natural beauty. The abundant lilacs in the town inspired Louisa May Alcott (who wrote Little Women) to write the 1878 book Under the Lilacs.

Malaise of elderly grows as pandemic grinds on

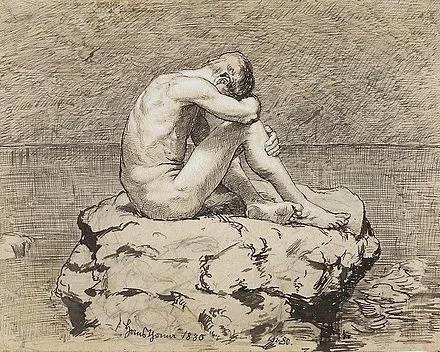

“Loneliness,’’ by Hans Thoma, in the National Museum in Warsaw.

“Folks are becoming more anxious and angry and stressed and agitated because this has gone on for so long.’’

— Katherine Cook, chief operating officer of Monadnock Family Services in Keene, N.H., which operates a community mental-health center that serves older adults.

Late one night in January, Jonathan Coffino, 78, turned to his wife as they sat in bed. “I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” he said, glumly.

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system

Coffino was referring to the caution that’s come to define his life during the COVID-19 pandemic. After two years of mostly staying at home and avoiding people, his patience is frayed and his distress is growing.

“There’s a terrible fear that I’ll never get back my normal life,” Coffino told me, describing feelings he tries to keep at bay. “And there’s an awful sense of purposelessness.”

Despite recent signals that COVID’s grip on the country may be easing, many older adults are struggling with persistent malaise, heightened by the spread of the highly contagious omicron variant. Even those who adapted well initially are saying their fortitude is waning or wearing thin.

Like younger people, they’re beset by uncertainty about what the future may bring. But added to that is an especially painful feeling that opportunities that will never come again are being squandered, time is running out, and death is drawing ever nearer.

“I’ve never seen so many people who say they’re hopeless and have nothing to look forward to,” said Henry Kimmel, a clinical psychologist in Sherman Oaks, California, who focuses on older adults.

To be sure, older adults have cause for concern. Throughout the pandemic, they’ve been at much higher risk of becoming seriously ill and dying than other age groups. Even seniors who are fully vaccinated and boosted remain vulnerable: More than two-thirds of vaccinated people hospitalized from June through September with breakthrough infections were 65 or older.

The constant stress of wondering “Am I going to be OK?” and “What’s the future going to look like?” has been hard for Kathleen Tate, 74, a retired nurse in Mount Vernon, Wash. She has late-onset post-polio syndrome and severe osteoarthritis.

“I guess I had the expectation that once we were vaccinated the world would open up again,” said Tate, who lives alone. Although that happened for a while last summer, she largely stopped going out as first the delta and then the omicron variants swept through her area. Now, she said she feels “a quiet desperation.”

This isn’t something that Tate talks about with friends, though she’s hungry for human connection. “I see everybody dealing with extraordinary stresses in their lives, and I don’t want to add to that by complaining or asking to be comforted,” she said.

Tate described a feeling of “flatness” and “being worn out” that saps her motivation. “It’s almost too much effort to reach out to people and try to pull myself out of that place,” she said, admitting she’s watching too much TV and drinking too much alcohol. “It’s just like I want to mellow out and go numb, instead of bucking up and trying to pull myself together.”

Beth Spencer, 73, a recently retired social worker who lives in Ann Arbor, Mich., with her 90-year-old husband, is grappling with similar feelings during this typically challenging Midwestern winter. “The weather here is gray, the sky is gray, and my psyche is gray,” she told me. “I typically am an upbeat person, but I’m struggling to stay motivated.”

“I can’t sort out whether what I’m going through is due to retirement or caregiver stress or covid,” Spencer said, explaining that her husband was recently diagnosed with congestive heart failure. “I find myself asking ‘What’s the meaning of my life right now?’ and I don’t have an answer.”

Bonnie Olsen, a clinical psychologist at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, works extensively with older adults. “At the beginning of the pandemic, many older adults hunkered down and used a lifetime of coping skills to get through this,” she said. “Now, as people face this current surge, it’s as if their well of emotional reserves is being depleted.”

Most at risk are older adults who are isolated and frail, who were vulnerable to depression and anxiety even before the pandemic, or who have suffered serious losses and acute grief. Watch for signs that they are withdrawing from social contact or shutting down emotionally, Olsen said. “When people start to avoid being in touch, then I become more worried,” she said.

Fred Axelrod, 66, of Los Angeles, who’s disabled by ankylosing spondylitis, a serious form of arthritis, lost three close friends during the pandemic: Two died of cancer and one of complications related to diabetes. “You can’t go out and replace friends like that at my age,” he told me.

Now, the only person Axelrod talks to on a regular basis is Kimmel, his therapist. “I don’t do anything. There’s nothing to do, nowhere to go,” he complained. “There’s a lot of times I feel I’m just letting the clock run out. You start thinking, ‘How much more time do I have left?’”

“Older adults are thinking about mortality more than ever and asking, ‘How will we ever get out of this nightmare,’” Kimmel said. “I tell them we all have to stay in the present moment and do our best to keep ourselves occupied and connect with other people.”

Loss has also been a defining feature of the pandemic for Bud Carraway, 79, of Midvale, Utah, whose wife, Virginia, died a year ago. She was a stroke survivor who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heartbeat. The couple, who met in the Marines, had been married 55 years.

“I became depressed. Anxiety kept me awake at night. I couldn’t turn my mind off,” Carraway told me. Those feelings and a sense of being trapped throughout the pandemic “brought me pretty far down,” he said.

Help came from an eight-week grief support program offered online through the University of Utah. One of the assignments was to come up with a list of strategies for cultivating well-being, which Carraway keeps on his front door. Among the items listed: “Walk the mall. Eat with friends. Do some volunteer work. Join a bowling league. Go to a movie. Check out senior centers.”

“I’d circle them as I accomplished each one of them. I knew I had to get up and get out and live again,” Carraway said. “This program, it just made a world of difference.”

Kathie Supiano, an associate professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing who oversees the COVID grief groups, said older adults’ ability to bounce back from setbacks shouldn’t be discounted. “This isn’t their first rodeo. Many people remember polio and the AIDS epidemic. They’ve been through a lot and know how to put things in perspective.”

Alissa Ballot, 66, realized recently she can trust herself to find a way forward. After becoming extremely isolated early in the pandemic, Ballot moved last November from Chicago to New York City. There, she found a community of new friends online at Central Synagogue in Manhattan and her loneliness evaporated as she began attending events in person.

With Omicron’s rise in December, Ballot briefly became fearful that she’d end up alone again. But, this time, something clicked as she pondered some of her rabbi’s spiritual teachings.

“I felt paused on a precipice looking into the unknown and suddenly I thought, ‘So, we don’t know what’s going to happen next, stop worrying.’ And I relaxed. Now I’m like, this is a blip, and I’ll get through it.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Straining through the winter

“All winter your brute shoulders strained against collars, padding

and steerhide over the ash hames, to haul

sledges of cordwood for drying through spring and summer,

for the Glenwood stove next winter, and for the simmering range.’’

— From “Names of Horses,’’ by Donald Hall (1928-2018), a U.S. poet laureate who spent his last decades at Eagle Pond Farm, in Wilmot, N.H. This poem is a reference to the horses used by his maternal grandparents at the farm.

Hollywood in Hanover

“Dolores del Rio for the Trail of '98” (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1928, gelatin silver print), by Russell Ball, in “Photographs from Hollywood’s Golden Era: The John Kobal Foundation,’’ at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.

The Hood’s acquisition of these photographs gives it one of the world’s largest collections of photos from Hollywood’s golden age.

The museum says that "these images cover the gamut of studio photography from portraiture and publicity shots to film stills from Hollywood’s golden era of the 1920s through the 1950s." In addition to the photographs, a virtual lecture by renown film historian and film-maker Kevin Brownlow will be held on March 3 from 12:30–1:30 EST. For more information, please visit here.

‘I celebrate plants’

“Weeds in Black” (encaustic), by Debra Claffey, who’s based in New Boston, a small town in southern New Hampshire. She’s a member of New England Wax (newenglandwax.com).

She says:

“My experience in horticulture and organic land care has led me to focus in on the plant world and the assaults on the soil, biodiversity of plant species, and the protection of native flora. I celebrate plants: their great age and history on the planet, their intelligence and successful adaptions, their beauty of form, shape, and infinite color. I marvel in our new knowledge of their ways of communication, of making themselves attractive to us and other species, and the trading of ‘goods and services’ that goes on between plants, fungi, bacteria, insects, birds, and even us mammals.’’

New Boston in 1875. Below is an edited version of the Wikipedia entry on the town, which was chartered in 1736.

“In 1820, the town had 25 sawmills, six grain mills, two clothing mills, two carding mills, two tanneries and a bark mill. It also had 14 schoolhouses and a tavern. The Great Village Fire of 1887, which started when a spark from a cooper's shop set a barn on fire, destroyed nearly 40 buildings in the lower village. In 1893, the railroad came to New Boston, and farm produce was sent by rail to city markets. Passenger service was discontinued in 1931, and the tracks were removed in 1935. Today the former grade is the multi-use New Boston Rail Trail.

“The town {along with the adjacent towns of Amherst and Mont Vernon} is home to the 2,800-acre New Boston Space Force Station, which started as an Army Air Corps bombing range in 1942. By 1960, it had become a U.S. Air Force base for tracking military satellites. In July 2021, the facility was given its current name and began operating as part of the United States Space Force. New Boston was also home to the Gravity Research Foundation from the late 1940s through the mid-1960s. Founder Roger Babson placed it in New Boston because he believed it safe from nuclear fallout should New York or Boston be attacked.’’

New Boston Space Force Station

Lost and found in the mountains

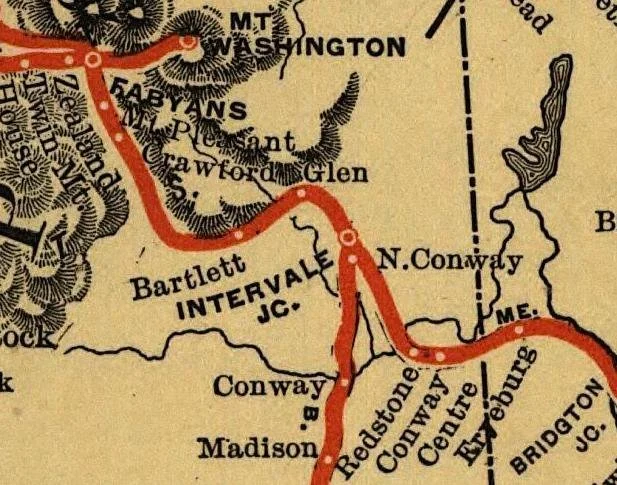

Mt. Washington from Intervale, N.H.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

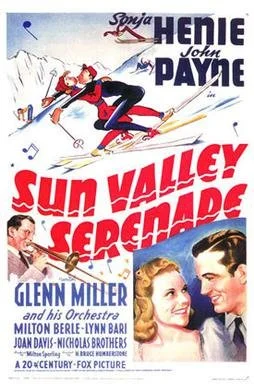

I was wandering around in the Internet the other night and came across a 1941 movie called Sun Valley Serenade, a musical film set in the Idaho ski resort of the same name. Seeing it took me back to February 1971, when I watched the film in a hotel room in Jackson, N.H. I was up there covering, (for The Boston Herald Traveler) the search for a couple of guys lost or dead just up the road, on Mt. Washington. The search was being run out of the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Pinkham Notch facility.

For three days, about a dozen of us journalists (including from such national media such as Time magazine) hung around as rescuers from the National Forest Service looked for these guys. They eventually found them safe in a shelter somewhere near the tree line. But the authorities were very angry that such inexperienced climbers had jeopardized the rescuers on that infamously stormy mountain. (I’ve climbed it myself twice in the winter with an experienced team. It’s a beautiful spectacle.)

“Do those little bastards know how much this is costing?’’ griped one of rescuers.

Of course, we journos were bored much of the time, but some of us snuck away for cheery drinks and dinner in Jackson, hoping that nothing exciting would happen while we were enjoying ourselves.

But what I most remember from that trip, one of many crazy expeditions during my time at The Herald Traveler, was sitting in my hotel room as wet snow fell outside watching Sun Valley Serenade on the TV and, particularly, listening to the song “I Know Why’’ being sung while backed by the Glenn Miller Orchestra. One of the lines is “Even though it’s snowing, violets are growing.’’

Corny but it brings a pang about the passage of time

I probably have yellowed clips of my stories of the lost climbers in the cellar, but I’d bring on an asthma attack looking for them. In those deep, dark, pre-Internet days you’d need clips to get your next newspaper job, if you were foolish enough to want one.

Stephen J. Nelson: Of visionary John Kemeny and decades of court battles over affirmative action at colleges

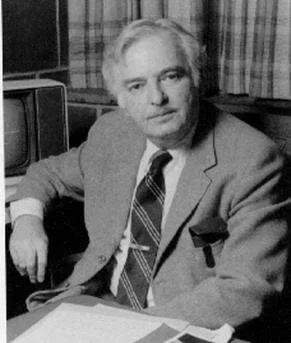

John G. Kemeny (1926-1992), Hungarian-born mathematician, computer scientist and president of Dartmouth College in 1970-1981

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Supreme Court is taking up affirmative action at colleges and universities for the sixth time in 50 years. In that litany, an early case was the University of California vs. Bakke. Bakke complained about being denied admission to the university’s medical school because seats were guaranteed for minority applicants, thus barring the door to him and other white applicants.

When the Bakke case was on the court’s docket, John Kemeny was president of Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. The Dartmouth board of trustees wanted a public statement by the college on Bakke. Given their strong confidence in Kemeny, they gave him sole authority to craft Dartmouth’s stand on affirmative action. Kemeny’s voice from his bully pulpit into the public square about the Bakke case echoes today.

Kemeny’s argument displays ahead-of-the-curve insights. His major concern, one still very much at stake in the outcome of the court’s deliberations today, was that colleges had to be able to maintain their fundamental purposes in the face of any court judgment. Should the court mandate a cookie-cutter approach for college admissions, the unintended consequence would be to reduce diversity among institutions of higher education something that Kemeny said simply would be “highly undesirable.”

Using Dartmouth’s example, Kemeny underscored that the board had affirmed the college’s purpose as “the education of men and women with a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society.”

The board did not define that purpose as “the education of students who have the ability to accumulate high grade-point averages at the College,” a statement that would be “ludicrous!”

Kemeny pushed back against the court going over the edge if it were to compel colleges and universities exclusively to use test scores and presumed objective measures to decide which students to admit. That legal edict would restrict colleges from recruiting and admitting musicians, athletes and any student uniquely qualified to contribute to a student body and a college. Quotas of any sort were in his judgment “abhorrent.” Beware what you wish for.

Years after Bakke, in the 2003 University of Michigan cases, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor asserted that colleges had roughly 25 more years to solve their equity and equal-opportunity problems. After that time, reliance on affirmative-action policies would run out. O’Conner’s clock continues to tick.

Getting to where she urged has proved difficult. Progress on the diversity front in the Ivory Tower is glacial and complicated because competing interests must be addressed and give their blessing or at least not actively resist new programs and initiatives. More time than O’Conner predicted is clearly needed. Ideological players on all sides agree that substantive changes in fairness and equity is the arrival point, though there will always be huge differences about the roadmap.

Greater diversity at colleges and universities makes their campus communities more engaging, more demanding, more rewarding and their members more fully educated. Absent diversity, the highest values of what we want a college education to be will remain outside our grasp. That is true for our body politic inside and outside the gates as graduates take their places in the social of communities and the nation. This picture is the goal, but how to get there and how long it will take are the great unknowns.

The new challenge brought by Students for Fair Admissions alleges that Harvard University discriminates against Asian-American students and the University of North Carolina discriminates against white and Asian- American applicants by continuing the use of race as an upfront criteria in admissions rather than observing a race-blind approach that would place more credence and consideration on an applicant’s struggles with discrimination in their life experiences.

The Supreme Court, of course, relies on arguments. The presidents of our colleges and universities must as a group get in the arena, present their case and gather defenders in amicus briefs. The cards will fall as the court dictates. However, jousting over what the Justices will say has to be embraced. It must be made clear to the court’s justices that they must not do harm to hard-fought policies designed to make our colleges and universities equitable, fair and open to diverse populations. Confining latitude and judgments about the scope of admissions procedures and aspirations to add greater diversity to their student bodies would rob colleges and universities of the very autonomy and freedom in their affairs that makes us the envy of the world. The shape of the future of diversity at our colleges is at stake and college presidents must weigh in with all the authority they can muster.

The voices of college presidents have to be front and center in this debate and in the court’s verdict. John Kemeny’s wisdom is a mantle that today’s presidents and those of us concerned diversity and equal opportunity on our campus must take up.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and senior scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. He is the author of the recently released book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency. He has written several NEJHE pieces on the college presidency.

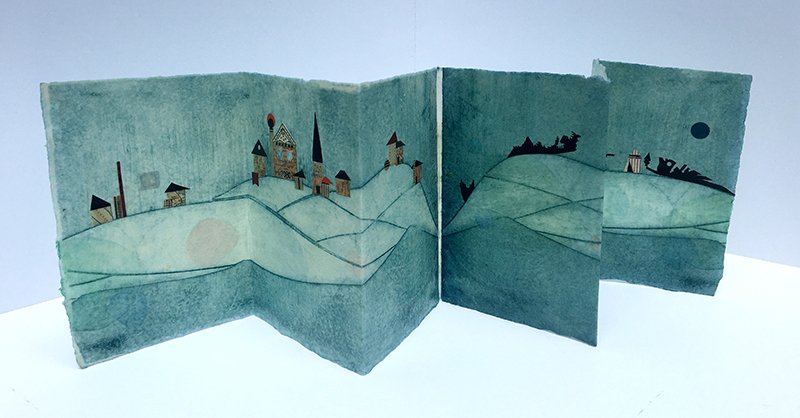

Folding up winter

“Dragon Journey Book” (monoprint, antique paper, encaustic, on BFK paper), by Soosen Dunholter, who lives in Peterboro, N.H., which has long hosted many artists. The MacDowell residence there for artists founded in 1907, has attracted famed creative types (painters, writers, composers, etc.) from around America since its inception. Ms. Dunholter is a member of New England Wax (newenglandwax.com). Hit this link for her Web site.

View of Peterboro circa 1907, looking toward Mt. Monadnock.

‘It’s not intellectual’

Rock of Ages granite quarry in Graniteville, Vt.

]

“Never confuse faith, or belief — of any kind — with something even remotely intellectual.’’

— From A Prayer for Owen Meany, a novel by John Irving (born 1942)

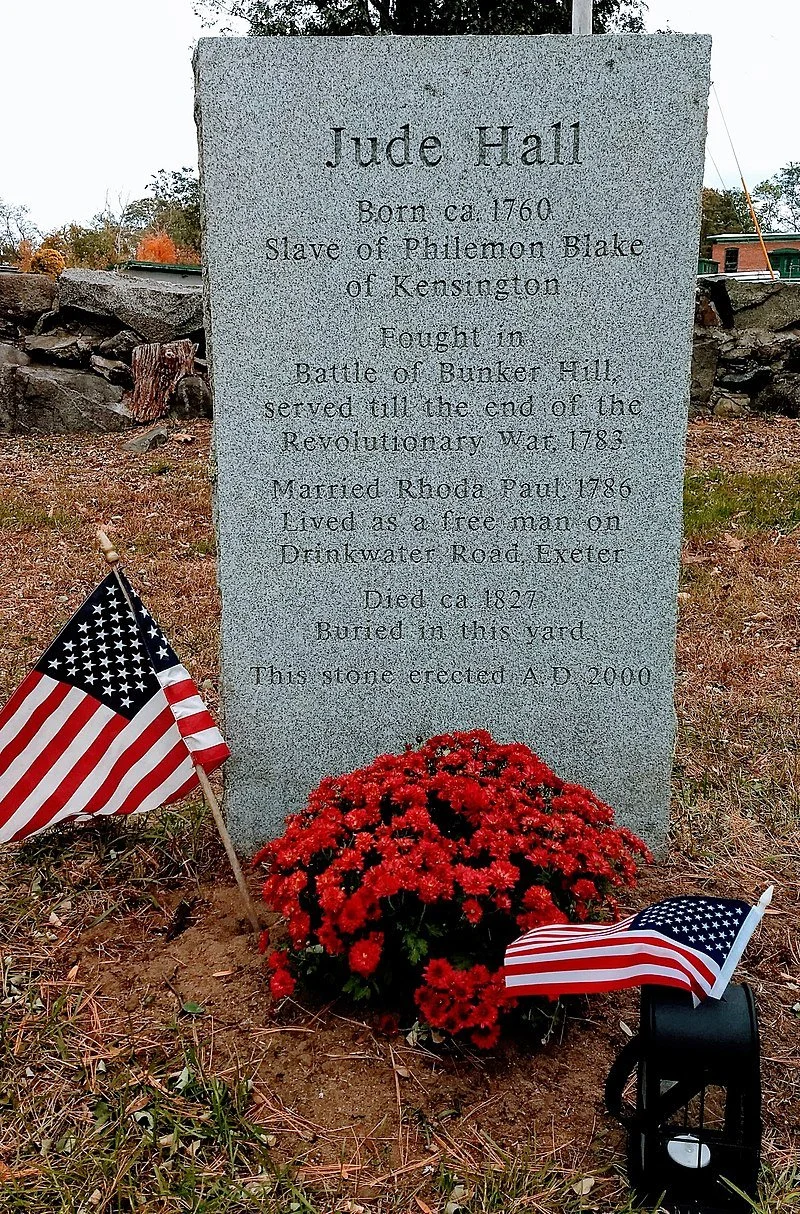

The plot centers around John Wheelwright and Owen Meany, who live in the fictional town of Gravesend, N.H. (based on Irving’s hometown of Exeter, N.H.). As boys they are close friends, although John comes from an old rich family — as the illegitimate son of Tabitha Wheelwright — and Owen is the only child of a working-class granite quarryman. John's earliest memories of Owen involve lifting him up in the air, easy because of his permanently small stature, to make him speak. And an underdeveloped larynx causes Owen to speak in a high-pitched voice. During his life, Owen comes to believe that he is "God's instrument".

Jude Hall granite memorial stone in Exeter, N.H.

A still, very New England place for reflection, not feasting

On Thanksgiving: In Jaffrey Center, N.H., with Mt. Monadnock in the background. The celebrated novelist Willa Cather is buried in Jaffrey’s Old Burying Ground.

— Photo by William Morgan

‘A Wintry Mix’

“Would you like to swing on a star?” (collage), by Rich Fedorchak, of Thetford, Vt., in the show “Wintry Mix’,’ at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H., Nov. 19-Dec. 30.

The gallery says: "The holiday exhibition will feature the work of member artists from Vermont and New Hampshire. Works in a variety of media—oil, watercolor, drawing, printmaking, mixed media, photography, ceramics, textiles, sculpture, jewelry, and glasswork—will be on display and available for sale in a wide range of prices."

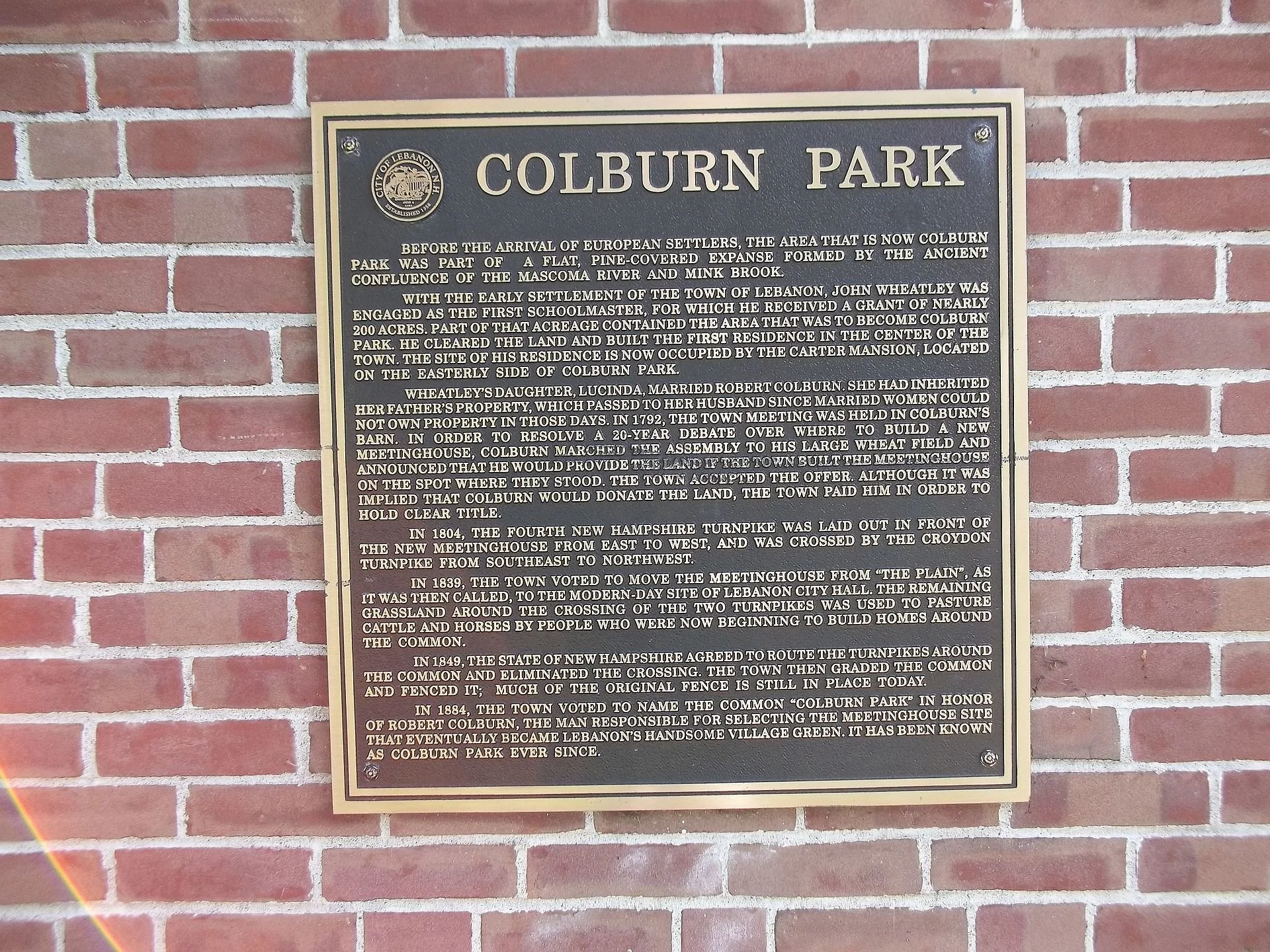

A little local history

— Photo by Artaxerxes

External and internal landscapes

“Connecticut River Valley at Claremont, N.H.,’’ by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902)

Along the Connecticut: Riverbank reconstruction project in Fairlee, Vt.

“There are few things as involuntary as a person’s identification with a landscape.’’

— Terry Osborne, writer and teacher, in his book Sightlines: The View of a Valley Through the Voice of Depression. He died of cancer in 2020 at the age of 60.

From the official summary of the book:

“For twelve years, writer Terry Osborne devoted himself to an intense exploration of the physical environment near his home in the {Upper} Connecticut River Valley {where he lived first in Thetford, Vt., and then in Etna, N.H.} The more he walked the land, the more deeply he came to know its hills and wetlands. But his growing intimacy with the area inspired something unexpected. The valley, formed by colliding and dividing continents, scoured by massive glaciers, and cut by rivers and streams, began to reveal and resonate with Osborne's internal landscape, long shaped from within by an unyielding depressive voice.’’

Mystical physics

“The Mystic Alone Sees the Sun Aglow at Midnight,’’ (tar and gold leaf on canvas), by Christopher Volpe, in his show “Alchemy and After,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Nov. 3-28. Art New England says:

“Christopher Volpe’s paintings are stark conduits of the inherent oppositions between human beings and the natural world.”

He lives in Hollis, N.H.

Monument Square and Hollis Town Hall

'Neat and tractored'

The Green in Hanover, N.H.

“Although the smell of fresh-cut grass

is the same everywhere to me

it will always be Hanover {N.H.}:

rec soccer, someone’s tamed

plot of land neat and tractored…’’

— From “A Child’s Guide to Grasses,’’ by Jay Deshpande

Better than manifestos

Nubanusit Lake, in the towns of Hancock and Nelson, N.H.

Hancock, N.H., Man Street in 1907

“If a community has good walking paths through fields and forests, people will use them. The right environment is a far better teacher than a heap of manifestos.’’

— Howard Mansfield (born 1957) in The Same Ax, Twice: Restoration and Renewal in a Throwaway Age. He lives in Hancock, N.H., with his wife, Sy Montgomery, who is well known for writing about animals.