The wet look

Sunny day flooding in Miami during a “king tide’’.

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 2012.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The stuff below is a heavily edited version of some of the remarks I made in a talk a couple of weeks ago and seem to me particularly resonant as we head into summer coastal vacation season:

Most of us are in denial or oblivious when it comes to sea-level rise caused by global warming. For example, Freddie Mac researchers have found that properties directly exposed to projected sea-level rise have generally gotten no price discount compared to those that aren’t, though that may be changing. And some states don’t require sellers to disclose past coastal floods affecting properties for sale. Politicians often try to block flood-plain designations because they naturally fear that they would depress real-estate values.

So the coast keeps getting more built up, including places that may be underwater in a few decades. It often seems that everyone wants to live along the water.

As the near-certainty of major sea-level rise becomes more integrated into the pricing calculations of the real-estate sector, some people of a certain age can get bargains on property as long as they realize that the property they want to buy might be uninhabitable in 20 years. Younger people, however, should seek higher ground if they want to live near the ocean for a long time.

A tricky thing is that real estate can’t just be abandoned—it must pass from one owner to another. Some local governments’ coastal permits require owners to pay to remove their structures when the average sea level rises to a certain point. Absent such requirements, many local governments’ budgets may not be enough to pay for demolition or the moving costs associated with inundation. There are some interesting liability issues here.

What to do?

Administrative mitigation would include raising federal flood-insurance rates and more frequently updating flood-projection maps. More localities can take stronger steps to ban or sharply limit new structures in flood-prone areas and/or order them removed from those areas. And, as implied above, they should implement flood-experience-and-projection disclosure requirements in sales documents.

As for physical answers to thwarting the worst effects of sea-level rise, especially in urban areas, many experts believe that some form of the Dutch polder approach, which integrates hard stone, concrete or even metal infrastructure, and soft nature-based infrastructure, along with dikes, drainage canals and pumps, may have to be applied in some low places, such as Miami and Boston’s Seaport District. Barrington and Warren, R.I., look like polder country.

Polders are large land-and-water areas, with thick water-absorbent vegetation, surrounded by dikes, where the ground elevation is below mean sea level and engineers control the water table within the polder.

Just hardening the immediate shoreline, and especially beaches, with such structures as stone embankments to try to keep out the water won’t work well. That just makes the water push the sand elsewhere and can dramatically increase shoreline erosion.

On the other hand, creating so-called horizontal levees – with a marshy or other soft buffering area backed with a hard surface -- can be a reasonable approach to reduce the impact of storms’ flooding on top of sea-level rise.

Certainly establishing marshes (and mangrove swamps in tropical and semi-tropical coastal communities) can reduce tidal flooding and the damage from storm waves, but that may be a political nonstarter in some fancy coastal summer- or winter-resort places. Then there’s putting more houses and even stores and other nonresidential buildings on stilts, though that often means keeping buildings where safety considerations would suggest that there shouldn’t be any structures, such as on many barrier beaches. Still, it would be amusing to see entire large towns on stilts. Good water views.

Oyster and other shellfish beds can be developed as (partly edible!) breakwaters. And laying down permeable road and parking lot pavements can help sop up the water that pours onto the land. I got interested in how shellfish beds can act as a brake on flood damage while editing a book about Maine aquaculture last year. Of course, the hilly coast of Maine provides many more opportunities to enjoy a water view even with sea-level rise while staying dry than does, say, South County’s barrier beaches.

In more and more places where sea-level rise has caused increasing ‘’sunny day flooding’’ -- i.e., without storms -- streets are being raised.

I’m afraid that, barring, say, a volcanic eruption that rapidly cools the earth, slowing the sea-level rise, the fact is that we’ll have to simply abandon much of our thickly developed immediate coastline and move our structures to higher ground.

Working-waterfront enterprises -- e.g., fishing and shipping -- must stay as close to the water as possible. But many houses, condos, hotels, resorts and so on can and should be moved in the next few years. If they don’t have to be on a low-lying shoreline, they shouldn’t be there as sea level rises. For that matter, entire large communities may have to be entirely abandoned to the sea even in the lifetime of some people here.

Coastal communities and property owners face hard choices: whether to try to hold back the rising ocean or to move to higher ground. Nothing can prevent this situation from being expensive and disruptive.

Common sense would suggest that we not build where it floods and that we should stop recycling flooded properties. Again, flood risks should be fully disclosed and we need to protect or restore ecologies, such as marshes, shellfish and coral reefs and dune grass, that reduce flooding and coastal erosion.

Nature wins in the end.

New England on the rocks

“Rock Doxology’’ (oil on canvas), by Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass. While Hartley lived in many places, including Europe, he was born in the Maine mill town of Lewiston (where he had an unhappy youth) and died in Ellsworth (near the resort town of Bar Harbor) and in his last decades called himself “The Painter of Maine.’’

Rocks sure are icons of New England!

Ellsworth’s Col. John Black House, built 1824–1827 after a pattern book design by Asher Benjamin; now part of Woodlawn Museum. Shipping, shipbuilding, fishing and manufacturing made many people rich on the Maine Coast in the early and mid 19th Century, and many of their gorgeous houses are still standing.

LiAnna Davis: How New England students are improving Wikipedia

Dante holding a copy of the Divine Comedy, next to the entrance to Hell, the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory and the city of Florence, with the spheres of Heaven above, in Domenico di Michelino's 1465 fresco. Wellesley (Mass.) College students have been editing the Wikipedia articles on the masterpiece to highlight the women Dante referenced.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org), based in Boston.

You probably use Wikipedia regularly, maybe even every day. It’s where the world goes to learn more about almost anything, do a quick fact-check or get lost in an endless stream of link clicking. But have you ever stopped to think about the people behind the information you’re reading on Wikipedia? Or how their perspectives may inform what’s covered—and what’s not?

All content to Wikipedia is added and edited in a crowdsourced model, wherein nearly anyone can click the “edit” button and change content on Wikipedia. An active community of dedicated volunteers adds content and monitors the edits made by others, following a complex series of policies and guidelines that have been developed in the 21 years since Wikipedia started. This active community is what keeps Wikipedia as reliable as it is today—good, but not complete. More diverse contributors are needed to add more content to Wikipedia.

Some of that information has been added by college students from New England, written as a class assignment. The Wiki Education Foundation, small nonprofit, runs a program called the Wikipedia Student Program, in which we support college and university faculty who want to assign their students to write Wikipedia articles as part of their coursework.

Why do instructors assign their students to edit Wikipedia as a course assignment? Research shows a Wikipedia assignment increases motivation for students, while providing them learning objectives like critical thinking, research, writing for a public audience, evaluating and synthesizing sources and peer review. Especially important in today’s climate of misinformation and disinformation is the critical digital media literacy skills students gain from writing for Wikipedia, where they’re asked to consider and evaluate the reliability of the sources they’re citing. In addition to the benefits to student learning outcomes, instructors are also glad to see Wikipedia’s coverage of their discipline get better. And it does get better; studies such as this and this and this have shown the quality of content students add to Wikipedia is high.

Since 2010, more than 5,100 courses have participated in the program and more than 102,000 student editors have added more than 85 million words to Wikipedia. That’s 292,000 printed pages or the equivalent of 62 volumes of a printed encyclopedia. To put that in context, the last print edition of Encyclopedia Britannica had only 32 volumes. That means Wikipedia Student Program participants have added nearly twice as much content as was in Britannica.

Students add to body of knowledge

It’s easy to think of Wikipedia as fairly complete if it gives you the answer you seek most of the time. But the ability for student editors to add those 85 million words exposes this assumption as false. Let’s examine some examples.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the public’s interest in vaccines and therapeutics has skyrocketed. Thanks to a Boston University School of Medicine student in Benjamin Wolozin’s Systems Pharmacology class in fall 2021, the article on reverse pharmacology has been overhauled. Before the student started working on it, the article was what’s known on Wikipedia as a stub—a short, incomplete article. Today, thanks to Dr. Wolozin’s student adding a dramatic 17,000 words to the article, it’s a comprehensive description of hypothesis-driven drug discovery.

Medical content is popular on Wikipedia. In fact, Wikipedia’s medical articles get more pageviews than the websites for the National Institutes of Health, WebMD, Mayo Clinic, the British National Health Service, the World Health Organization and UpToDate.

Student editors in Mary Mahoney’s History of Medicine class at Connecticut’s Trinity College improved a number of medical articles, including those on pediatrics, telehealth, pregnancy and Mary Mallon (better known as Typhoid Mary), to name just a few. In the handful of months since students improved these articles, they’ve been viewed more than 932,000 times. As many tenured professors who’ve taught with Wikipedia note, more people will read the outcomes of student work from their Wikipedia assignments than will read an entire corpus of academic publications.

Sometimes their work adds cultural relevance to existing articles. Take Gwen Kordonowy’s “Public Writing” course at Boston University. Before one of her students expanded the article on Xiangsheng, the traditional Chinese performance art, it covered Xiangsheng in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Malaysia—but not in North America. The student added a section on Xiangsheng in North America, noting famous Canadian and American performers.

Many students study Dante’s Divine Comedy as part of their schoolwork, but have you considered the women Dante references? Until Wellesley College’s “Dante’s Divine Comedy” class started working on their Wikipedia articles, you may not have been able to learn much more. The course, taught by Laura Ingallinella, focused on highlighting the women Dante referenced and improving their articles.

Diversifying perspectives

The Wellesley College example is a good one because it’s indicative of a larger challenge of gaps within Wikipedia. Wikipedia’s existing editor base is relatively homogenous: In Northern America, the diversity demographics are grim. Only 22 percent of Wikipedia contributors are women, which directly correlates to content gaps like the ones the Dante class tackled. The race and ethnicity gaps are even worse. Recent survey data revealed 89 percent of U.S. Wikipedia content contributors identify as white.

With an overwhelmingly white, male editor base, content coverage and perspectives can get skewed. That’s where Wiki Education’s work comes in. By empowering a diverse group of college students, the program is able to help shift Wikipedia’s contributor demographics. In Wiki Education’s programs, 67 percent of participants identify as women, and an additional 3 percent identify as non-binary or another gender identity. And only 55 percent of Wiki Education’s program participants identify as white.

By empowering higher education students to address Wikipedia’s content gaps as class assignments, Wiki Education is helping to diversify the contributors to Wikipedia too. Wikipedia’s mission—to collect the sum of all human knowledge—requires participation from a diverse population of participants. Initiatives like the ones run by Wiki Education are key to helping achieve that vision.

When we support higher education students to contribute their knowledge, the story told by Wikipedia becomes more accurate, representative and complete.

LiAnna Davis is chief programs officer at Wiki Education.

Harris Meyer: Mass. pushing back against at pricey hospital group’s empire building

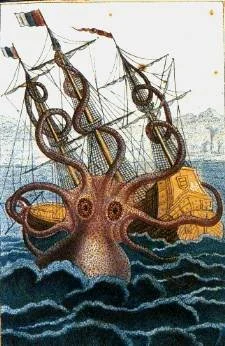

Pen and wash drawing by the malacologist Pierre de Montfort, 1801.

Front entrance of Massachusetts General Hospital.

A Massachusetts health-cost watchdog agency and a broad coalition including consumers, health systems, and insurers helped block the state’s largest — and most expensive — hospital system in April from expanding into the Boston suburbs.

Advocates for more affordable care hope that the decision by regulators to hold Mass General Brigham accountable for its high costs will usher in a new era of aggressive action to rein in hospital expansions that drive up spending. Their next target is a proposed $435 million expansion by Boston Children’s Hospital.

Other states, including California and Oregon, are paying close attention, eyeing ways to emulate Massachusetts’s decade-old system of monitoring health-care costs, setting a benchmark spending rate, and holding hospitals and other providers responsible for exceeding their target.

The Massachusetts Health Policy Commission examines hospital-specific data and recommends to the state Department of Public Health whether to approve mergers and expansions. The commission also can require providers and insurers to develop a plan to reduce costs, as it’s doing with MGB.

“The system is working in Massachusetts,” said Maureen Hensley-Quinn, a senior program director at the National Academy for State Health Policy, who stressed the importance of the state’s robust data-gathering and analysis program. “The focus on providing transparency around health costs has been really helpful. That’s what all states want to do. I don’t know if other states will adopt the Massachusetts model. But we’re hearing increased interest.”

With its many teaching hospitals, Massachusetts historically has been among the states with the highest per capita health-care costs, though its spending has moderated in recent years as state officials have taken aim at the issue.

On April 1, MGB, an 11-hospital system that includes the famed Massachusetts General Hospital, unexpectedly withdrew its proposal for a $223.7 million outpatient-care expansion in the suburbs after being told by state officials it wouldn’t be approved.

That expansion would have increased annual spending for commercially insured residents by as much as $28 million, driving up insurance premiums and shifting patients away from lower-priced competitors, according to the commission.

This marked the first time in decades that the state health department used its authority to block a hospital expansion because it undercut the state’s goals to control health costs.

Other parts of MGB’s $2.3 billion expansion plan also met resistance.

The health department staff recommended approving MGB’s proposal to build a 482-bed tower at its flagship Massachusetts General Hospital and a 78-bed addition at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. But they urged rejecting a request for 94 additional beds at MGH.

The department’s Public Health Council, whose members are mostly appointed by the governor, is scheduled to vote on those recommendations May 4.

The health policy commission, which works independently of the public health department but provides advice, has also required MGB to submit an 18-month cost-control plan by May 16, because its prices and spending growth have far exceeded those of other hospital systems. That was a major reason the growth in state health spending hit 4.3 percent in 2019, exceeding the commission’s target of 3.1%.

This is the first time a state agency in Massachusetts or anywhere else in the country has ordered a hospital to develop a plan to control its costs, Hensley-Quinn said.

MGB’s $2.3 billion expansion plan and its refusal to acknowledge its high prices and their impact on the state’s health costs have united a usually fractious set of stakeholders, including competing hospitals, insurers, employers, labor unions and regulators. They also were angered by MGB’s lavish advertising campaign touting the consumer benefits of the expansion.

Their fight was bolstered by a report last year from state Atty. Gen. Maura Healey that found that the suburban outpatient expansion would increase MGB annual profits by $385 million. The nonprofit MGB reported $442 million in operating income in 2021.

The Massachusetts Association of Health Plans opposed the MGB outpatient expansion.

The well-funded coalition warned that the expansion would severely hurt local hospitals and other providers, including causing job losses. The consumer group Health Care for All predicted the shift of patients to the more expensive MGB sites would lead to higher insurance premiums for individuals and businesses.

“Having all that opposition made it pretty easy for [the Department of Public Health] to do the right thing for consumers and cost containment,” said Lora Pellegrini, CEO of the health plan association.

Republican Gov. Charlie Baker, who has made health-care cost reduction a priority and who leaves office next January after eight years, didn’t want to see the erosion of the state’s pioneering system of global spending targets, she said.

“What would it say for the governor’s legacy if he allowed this massive expansion?” she added. “That would render our whole cost-containment structure meaningless.”

MGB declined to comment.

Massachusetts’s aggressive action examining and blocking a hospital expansion comes after many states have moved in the opposite direction. In the 1980s, most states required hospitals to get state permission for major projects under “certificate of need” laws. But many states have loosened or abandoned those laws, which critics say stymied competition and failed to control costs.

The Trump administration recommended that states repeal those laws and leave hospital-expansion projects up to the free market.

But there are signs the tide is turning back to more regulation of hospital building.

Several states have created or are considering creating commissions similar to the one in Massachusetts with the authority and tools to analyze the market impact of expansions and mergers. Oregon, for example, recently passed a law empowering a state agency to review health care mergers and acquisitions to ensure they maintain access to affordable care.

Despite the defeat of MGB’s outpatient expansion, Massachusetts House Speaker Ron Mariano, a Democrat, said the state’s cost-control model needs strengthening to prevent hospitals from making an end run around it. A bill he backed that passed the House would give the commission and the attorney general’s office a bigger role in evaluating the cost impact of expansions. The Senate hasn’t taken up the bill.

“Hospital expansion is the biggest driver in the whole medical expense kettle,” he said.

Meanwhile, cost-control advocates are eager to see how MGB proposes to control its spending, and how the Health Policy Commission responds.

“Unless MGB somehow agrees to limit increases in its supranormal pricing, like a five-year price freeze across the system, I don’t know that the [plan] will accomplish anything,” said Dr. Paul Hattis, a former commission member.

Hattis and others are also waiting to see how the state rules on a bid by Boston Children’s Hospital, another high-priced provider, to build new outpatient facilities in the suburbs.

“For those of us on the affordability side, it’s like the sheriffs rediscovered their badge and realized they really could say no,” he said. “That’s a message to other states that they also should constrain their larger provider systems, and to the systems that they can no longer do whatever they please.”

Harris Meyer is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

The ripple effect

“Wood Neck Sunset” (in Falmouth, on Cape Cod) (archival pigment print), by Bobby Baker.

© Bobby Baker Fine Art

William Morgan: Save downtown Providence's centerpiece

The Industrial Trust Co. building is the fulcrum of the Providence skyline.

— Photo by David I. Jacobson

Saving and rehabbing the Industrial Trust Co. Building is crucial to revitalizing downtown Providence. To imagine the city without the nicknamed “Superman Building,’’ is like contemplating Paris without the Eiffel Tower or London without Big Ben, New York without the Empire State Building or Washington without the Capitol.

Most of the recent discussion of saving the skyscraper, designed by the New York firm of Walker & Gillette and built in 1928, has been about the cost of restoration and who should bear that hefty multimillion-dollar expense. While no small matter, the real issue about preserving and rehabbing Providence’s most prominent urban symbol cannot hinge just on the money. Losing this landmark would be a disaster, one that would cost the city and state immeasurably more than bonded indebtedness or taxpayer pain. It would mean a loss of prestige, optimism, self-confidence and our well-earned reputation as a Renaissance City.

Aerial view of downtown Providence shows keystone position of Industrial Trust Building.

— Photo by Luis Carranza

The limestone-sheathed Art Deco masterpiece at 55 Kennedy Plaza is simply a landmark that we must not lose. More than any other element of the skyline, with the exception of the State House, the Industrial Trust Building is the identifiable icon of the city.

Not just the tallest, but the most attractive element of the downtown skyline.

— Photo by William Morgan

There are significant architectural and historical considerations that favor preservation, not to mention the benefits of an infusion of new downtown inhabitants. Yet, the key role that the Superman Building plays is as a majestic visual fulcrum – a clearly recognized feature, a compass marker, an urban punctuation point much like the Eiffel Tower.

Eye appeal: lantern detail of the top of the building, designed, among other things, to be a port for dirigibles.

— Photo by William Morgan

Unlike a lot of its newer neighbors, the Industrial Trust Building is an artfully decorated architectural masterpiece, and not a boringly repetitious wall of undifferentiated glass. Not just vertical real estate, its mass diminishes as it reaches for the sky–the work of architects who understood beauty, good proportions, scale and civic aspiration.

Compare the Superman Building with the 1973 addition to the Hospital Trust Tower, an uninspiring lump of travertine; in half a century the quality of downtown commercial architecture declined visibly.

— Photo by William Morgan

It is irresponsible to declare that the Industrial Trust Building will be razed if the current financing package cannot be agreed upon: this is a structure for which a use and renovation plan must be found. There is no alternative. As Robert Whitcomb argued recently in GoLocal, tearing down this noble identifier and symbol of the city’s once great commercial prowess would send a terrible message to the world. If we cannot afford to restore this treasure, how likely would we be able to fill in the void left by its destruction? Or as one of my urban-planning mentors, Congressman Charles Farnsley, a sponsor of the 1966 Historic Preservation Act, used to say of such urban mauling: This is like a beautiful woman losing a front tooth in a country with no dentists.

Charles Farnsley, mayor of Louisville, Ky., before working with Lyndon Johnson on preservation, had another phrase that is even more haunting: Americans are the only people who bomb their own cities. In a town known as a preservation success story, that’s not a mantle we should want to wear. Rather, we need to be the city that opened the rivers, removed an interstate highway slicing through its heart, and created a vibrant arts scene. If we can do that, we can figure a way to breathe new life into the Industrial Trust Building.

Providence skyline without the Industrial Trust Building.

— Photo by William Morgan

William Morgan is the architecture critic of GoLocalProv.com, as well as a long-time contributor to New England Diary. He’s the author of many books on architecture.

David Warsh: Money follows development and vice versa

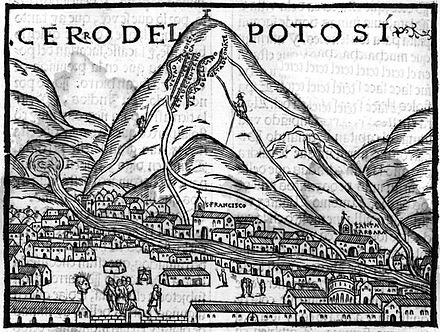

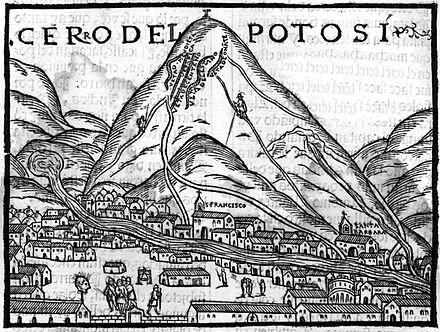

Cerro Rico del Potosi, the first European image, in 1553, of a silver-ore-rich mountain in what became Bolivia. It was heavily exploited by Spain.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A candy bar that cost a nickel in 1950 today costs $1.25 or so, depending on where you buy it. That, in a paper wrapper, is the price revolution of the 20th Century. Why did it happen? The answer usually given is that the quantity of money increased – too much paper money chasing too few candy bars.

A more satisfying explanation, casual though it may be, is to recognize that the global economy has grown considerably more complex since 1950, and the system of money, banking, and credit more complex along with it. The price of the candy bar wasn’t going to return to its previous level, no matter what the Fed or the candy-manufacturers did.

I’ve believed this for forty years, since writing The Idea of Economic Complexity, which appeared in 1984. While nothing has happened to change my mind, it has been interesting, at least to me, to have spent a few Saturdays thinking about what I have learned since then. Let me sum it up with a last few words of explanation, before putting it away.

At the moment, the jolt to increased economic complexity has to do with Russia’s war on Ukraine, the post-Cold War expansion of the NATO alliance and long-lasting disruptions of world trade stemming from the COVID pandemic. These “cost-push” factors are more fundamental to today’s rising prices, I believe, than whatever misjudgments that monetary authorities have made in responding to them. But arguing about recent events is the wrong way to develop views about phenomena as mysterious as the formation of money prices. For that, long-term developments serve best.

The price revolution of the 16th Century is the best example in the last thousand years of a lengthy, unreversed increase in money prices of everyday things. Its magnitude was modest by current standards; but then, so were monetary systems in those days. Between 1501 and 1650, prices of everyday goods across Europe rose six-fold before leveling off and remaining more or less stable on a new level for the next hundred years.

Practically from the beginning, scholars have argued about whether the discovery of the riches of Spanish America initiated the price revolution, or whether the voyages of discovery were undertaken in response to European events already underway. Jehan Cherruyt de Malenstroit blamed rising prices on shortages of precious metals and the extravagance of kings. In a widely read rejoinder, philosophe Jean Bodin, in 1568, ascribed rising prices to the influence of the treasure of The Americas – such was the beginning of what we have called ever since the quantity theory of money.

Economic historians were still arguing about these matters four centuries later. In American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, Earl Hamilton wrote, in 1934, that an “extremely close correlation” between growth in the volume of gold and silver imports from the New World and commodity prices in Spain “demonstrated beyond question” that the abundance of mines in New Spain was “the principal cause” of the price revolution. In Economic Development and the Price Level, in 1962, Geoffrey Maynard argued the opposite: that money generally adjusts to trade, rather than trade to money. In very different formats, the argument continues today.

“Development” is a bland word with which to describe the difference between the world economy in the time of Columbus and the world today. Economic philosopher David Ellerman has suggested that diversity describes the key difference, grounding his description in information theory; I proposed complexity in that 1984 book. But what is it that has become more diverse or complex? Not until I read “Increasing Returns an Economic Progress” (1928), by Allyn Young, did it occur to me that the growing complexity I had been thinking about were increases, of one sort or another, in the division of labor.

And there I left the subject behind. I was working for a magazine when I began writing about price history, complexity and plenitude, an exotic argument about the tacit assumptions of quantity theory of money, gleaned from reading Arthur O. Lovejoy’s The Great Chain of Being (1936). Magazines are lightweight vessels, quick to maneuver in pursuit of advantage, quick to move on. There was no way I could continue to write about economics.

Fortunately, I made my way to a serious newspaper. I finished the book I had begun, and soon put complexity behind me – until this spring, when I briefly took it out to re-examine it. Meanwhile, I had become an economic journalist, following the profession. I stumble on developments in growth theory, and these, too, eventually became a book, Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (2006).

So what have I learned? That journalism is about knowing, whereas economics is about proving. A great deal more truth can become known than can be proved, as physicist Richard Feynman once said. Complexity of the division of labor is still out there. Economists will get to it someday. See, for example, Hendrick Houthakker, “Economics and Biology: Specialization and Speciation” (1955). In the meantime, there are other important stories, happening now.

In case you are feeling unsatisfied, though, remember that five-cent candy bar. Are you comfortable with the too-much-money-chasing-too-few-goods story? Do you believe that the Fed could have prevented the rise in its price? And if wasn’t “inflation,” then what was it? The depreciation of money, relative to goods?

As with the 16th Century voyages of discovery, money follows development and development follows money. If you have only the quantity theory of money to rely on, you don’t know what is going on.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

‘Sluice the gutters bright’

Red maple blossoms

“On a tricyle left in marbletime (in Town,

In Spring), the curbside maples drop slow smiles

Of blossom, sluice the gutters bright. The drift

Of this greengold treemoulting veins the asphalt,

Warming all black decency, adopting all abandoned toys.’’

— From “New England Suite,’’ by Charles Philbrick (1922-1971), a Providence-based poet and professor at Brown University

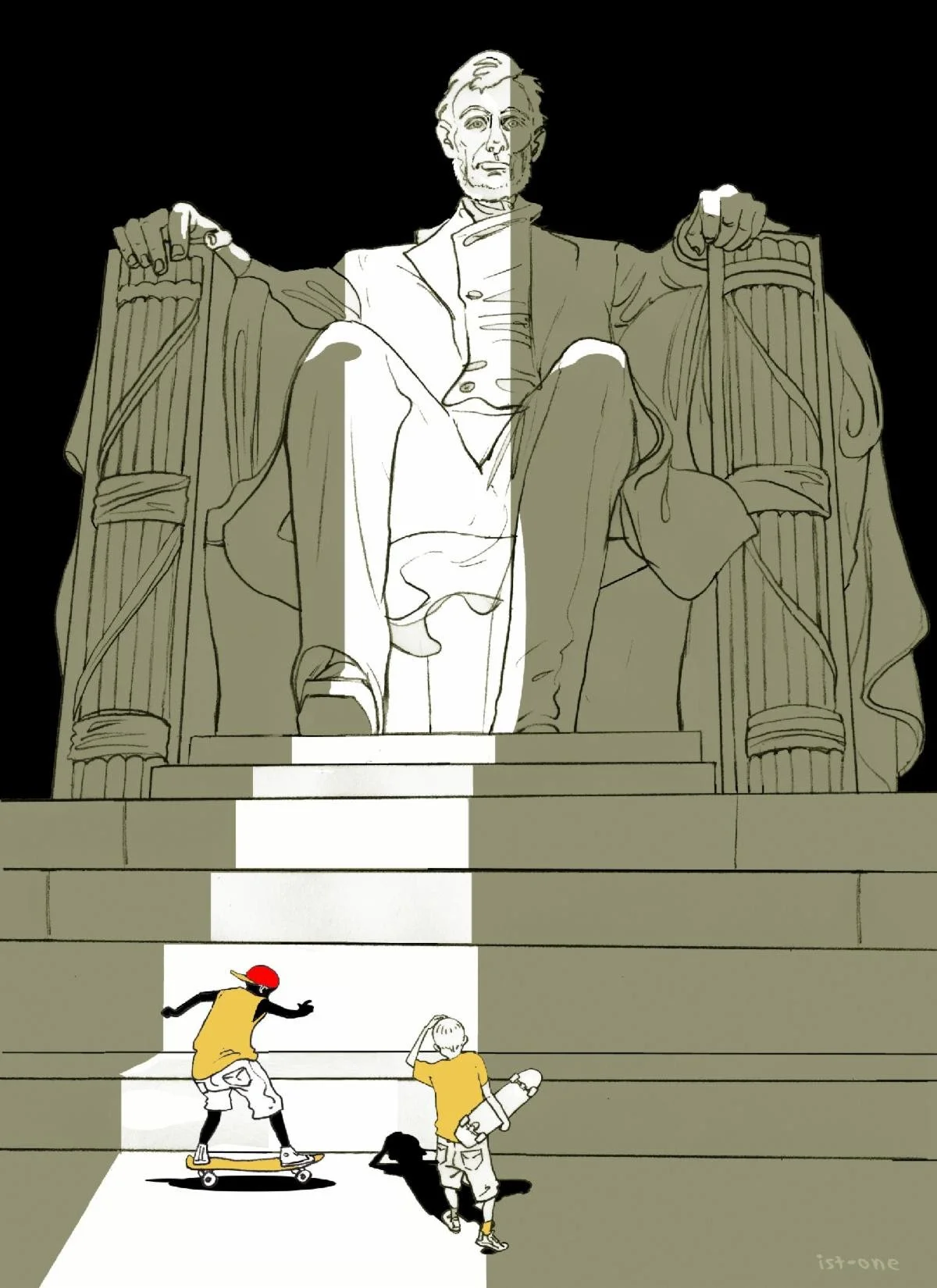

The art around our greatest president

Istvan Banyai, “Set in Stone” (cover illustration of The New Yorker, digital), by Istvan Banyai, in the exhibition “The Lincoln Memorial Illustrated,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., May 7-Sept. 4, in collaboration with Chesterwood.

The museum says: “Approximately fifty historical and contemporary artworks by noted illustrators and cartoonists will be featured, as will archival photographs, sculptural elements, artifacts and ephemera.” For more information, please visit nrm.org.

Studio and garden at Chesterwood

Photos by I, Daderot

Chesterwood was the summer estate and studio of American sculptor Daniel Chester French (1850–1931), in Stockbridge. French created the brooding-looking sculpture of Abraham Lincoln for the Lincoln Memorial. Most of French's originally 150-acre estate is now owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which operates the property as a museum and sculpture garden. The property was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 in recognition of French's importance in American sculpture.

Inside French’s studio

And now on to renewable natural gas in New England

Pipes carrying biogas (foreground) and condensate

— Photo by Volker Thies

Edited from a report by The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“National Grid announced it intends to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, by eliminating fossil fuels entirely from its gas networks. National Grid provides electricity and natural gas to communities in, among other places, central Massachusetts.

“National Grid believes that around 40 percent of fossil-fuel emissions in both Massachusetts and New York come from heating in buildings. They are seeking to remedy this situation by switching to renewable natural gas and green hydrogen, and away from gas obtained from fossil-fuel sources. This renewable natural gas can be obtained from decomposing materials at landfills and wastewater, and green hydrogen can be produced from wind farms. This move comes as many companies say that they are aiming to achieve net-zero emissions to combat climate change.

“‘This fossil-free vision is a historic announcement for National Grid and the United States,’ said John Pettigrew, the CEO of the United Kingdom-based National Grid. ‘We have a critical responsibility to lead the clean-energy transition for our customers and communities.”’

Jim Hightower: How America's truck drivers got hijacked into poverty

— Photo by Veronica538

Via OtherWords.org

“Keep On Truckin’” was an iconic underground cartoon created in 1968 by comic master Robert Crumb.

Featuring various big-footed men strutting jauntily through life, the expression became widely popular as an expression of young people’s collective optimism. “You’re movin’ on down the line,” Crumb later explained. “It’s proletarian. It’s populist.”

But today the phrase has become ironic. Like too many other workers, America’s truck drivers themselves are no longer moving on down the line of fairness, justice, and opportunity.

What had been a skilled, middle-class, union job in the 1960s is now largely a skilled poverty-wage job. That’s all thanks to the industry’s relentless push for deregulation and de-unionization, which has decoupled drivers from upward mobility.

Trucking has been turned into a corporate racket, with CEOs arbitrarily abusing the workers who move their products across town and country. To enable the abuse, corporate lawyers have fabricated a legal dodge, letting shippers claim that their truck drivers are not their “employees,” but “independent contractors.”

And just like that, drivers don’t get decent wages, overtime pay, workers comp, Social Security, health care, rest breaks, or reimbursement for truck expenses like gasoline, tires, repairs, and insurance. And as “contractors,” of course, drivers are not allowed to unionize.

This rank rip-off has become the industry standard, practiced by multibillion-dollar shipping giants like XPO, FedEx, Penske and Amazon. The National Employment Law Project recently reported that two-thirds of truckers hauling goods from U.S. ports are intentionally misclassified as contractors, rather than as employees of the profiteers that hire them, direct them, set their pay, and fire them.

Of course, corporate bosses try to hide their greed with a thin legalistic fig leaf. “We believe our [drivers] classifications are legal,” sniffed an XPO executive. Sure they are, sport, since your lobbyists write the laws!

But might doesn’t make right and “legal” doesn’t mean moral. It’s time to put truckers first and rebuild this great American occupation.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

Chris Powell: Forget student loan relief; finance nonprofits better

Student loan debt rose from $480.1 billion (3.5% GDP) in Q1 2006 to $1,683 billion (7.8% GDP) in Q1 2020.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Count on Connecticut state government to misdiagnose a problem if doing so can facilitate rewarding an influential interest group.

That is what is happening again with the student loan debt problem, as illustrated the other day bya report from the Connecticut Mirror.

The report focused on a single woman with two young children who is employed by a nonprofit organization and pursuing a master's degree in social work at the University of Connecticut. She anticipates she will have student loan debt of $100,000 upon her graduation in May and doesn't know how she'll ever repay it if she sticks with social work at a nonprofit organization as she wants to do.

Rather than question the woman's life choices and those of others in her situation, state legislators have submitted several bills addressing student loan debt. One would have state government reimburse $5,000 in debt payments every year for employees of nonprofit organizations dealing with health care or human services. The debt would have to have been incurred by attending a college in the state.

A more direct solution might result from recognizing why employees of nonprofit social-service groups in Connecticut are so stressed even without student loan debt. It is because state government finances the nonprofits so poorly even as they do most of state government's social work for half the cost of state government's own employees.

But why pay the nonprofit employees more if the money can be diverted to educators, a special interest comprising a big part of the army of Connecticut's majority political party? For that's what student loans are: a subsidy not to students but to educators.

Student loan debt is a burden only if the education for which the debt was undertaken does not enable the borrower to repay. Student loan debt may be a great investment for people pursuing highly paid careers, like medicine, engineering, science, and technology. But otherwise student loan debt is often a disaster, as millions of young people have discovered.

Many retail clerks, taxi drivers, telemarketers, waiters, and child care workers have student loan debt that, while unnecessary to their employment, is keeping them from forming families and acquiring housing.

That doesn't mean that higher education is useless and did not give those people a greater appreciation of life. It means the cost is too high, even as educators in Connecticut tend to be highly paid themselves, far better paid than the working-class people struggling with student loan debt. That's not fair.

Neither is student loan debt relief fair to the many people who worked and saved to pay their way through college without incurring debt. Debt relief makes them suckers, and still President Biden is considering debt relief on a national scale.

The clamor for student loan debt relief is doubly mistaken because the country's overwhelming problem in education is not higher education but lower education, where social promotion graduates most high school students without requiring them to master high school work. That policy is also a great subsidy to educators, since their jobs are much easier when student performance doesn't matter

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Dignity on the flats

“Hair Do” (pastel), by Susan Ellis in the Newburyport Art Association’s ‘‘Master Art Exhibit, Part 1,’’ through May 1.

Her Web site says:

“In 2015, Ellis moved ‘home’ to Massachusetts and settled on the picturesque North Shore. To her delight, a new artistic passion quickly revealed itself as she observed clam diggers working on the local mud flats. ‘I was instantly captivated by the contrast between the gritty reality of the clammers’ physical labor and the extraordinary beauty of the tidal landscape. Sand, rocks, salt hay, broken shells and muddy boots set in the context of wind whipped waters, expansive ocean horizons and the constantly changing coastal light is magical and inspirational.”

—Photo by Invertzoo

Mud flats in Brewster, Mass., extending hundreds of yards offshore at the low tide. The line of wrack and seashells in the foreground indicates the high-water mark.

— Photo by Caliga10

Llewellyn King: Supply-chain threats threaten U.S. renewable-energy sector

The Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia is one of the largest known lithium reserves in the world. Lithium is an essential material in batteries.

— Photo by Luca Galuzzi

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The move to renewable-energy sources and electrified transportation, constitutes a megatrend, a global seismic shift in energy production, storage and consumption. But there are dark clouds forming, clouds reminiscent of another time.

The United States has handed over the supply chain for this future to offshore suppliers of the critical materials used in the workhorse of the megatrend, the lithium-ion battery. These include lithium from South America and Australia; cobalt, primarily from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; nickel, copper, phosphate and manganese from countries where relations could sour overnight. Nickel from Russia, for example, is off the market because of the country’s invasion of Ukraine.

An additional concern is the role of China in processing these materials, many of which end up in Chinese-made batteries. Australian mines produce just under half of the global lithium supply, but most of that is exported directly to China for processing.

Another concern is that many mines producing critical materials have been bought by the Chinese. The Chinese role in the global supply of essential commodities is ubiquitous. Whether these come from Africa, South America, or elsewhere in Asia, China has a presence.

As attendees of a virtual press briefing, which I organized and hosted last month for the United States Energy Association, heard, the relentless growth in demand for the lithium-ion battery has put the supply chain under severe pressure.

Lithium-ion batteries owe their huge demand to their light weight. At present, there is no alternative in transportation that offers the portability of these batteries.

But when it comes to utility storage of electricity, where weight is not an impediment, quite a few technologies are in the wings. One, iron flow, is held up only by domestic supply-chain issues, according to Eric Dresselhuys, president of ESS Inc., a leading supplier of long-duration energy storage. This technology has additional advantages, because the drawdown time is longer than the two to four hours for a lithium-ion battery. The drawdown is eight to 10 hours, and all the components are sourced domestically, according to Dresselhuys.

Another storage technology is the old standby for starting cars: the lead-acid battery. John Howes, president of Redland Energy Group, points out that for stationary uses, lead-acid has many advantages, high among them is that there is a complete recycling regime in place -- something in its infancy with lithium-ion.

Obviously, there are weight issues with lead-acid batteries and iron batteries, but these aren’t at issue in storage for utility operations -- vital for wind and solar generation.

During the height of the energy crisis in the 1970s, I asked the chairman of Gulf Oil over dinner if the oil industry had ever consulted with the automobile industry on expected future demand for gasoline. His answer: “No.”

Out of curiosity, I pursued the subject and asked automobile manufacturers if they had ever questioned oil companies about whether there would be enough fuel for their cars. Detroit’s answer: “No.”

Both parties went along expecting the other would be there, playing their complementary roles: Oil companies producing enough product to meet the demand of an ever-growing population of internal combustion engines.

These parties, with everything at stake, relied on the unseen hand of the market to provide for the other in a synchronized symbiosis. With a few tough spots, that had worked since the early days of the automobile.

It all came crashing down when a third and unexpected force upset the market: the Arab oil embargo. That not only produced immediate dislocation in supply and demand, but it also pointed up underlying resource concerns.

The demand for lithium-ion batteries is likely to keep up. In a recent study, McKinsey & Company predicts stress, but it is hopeful that new lithium mining techniques may help alleviate the possible shortage.

McKinsey sees a huge increase in demand during this decade, without allowing for disagreements between nations, and disruptions stemming from geopolitics.

The assumption has been that there would be enough production of lithium-ion batteries to shoulder the responsibility. Now comes a reckoning, also triggered by a political action like the Arab oil embargo.

There was no real substitute for oil, but there are many better technologies and cutting-edge companies, including Tesla, are hard at finding alternative batteries. That will take time.

In the short term, your EV may cost more than it should, and it may be hard to get hold of one.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Some ‘courageous immigrants’ who ate well

The entrance to the Federal Hill neighborhood of Providence, traditionally the heartland of southeastern New England’s Italian-American community.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I was leafing through a copy of Dr. Edward Iannuccilli’s book What Ever Happened to Sunday Dinner? … and Other Stories the other day and enjoyed yet again these memoirs, which I first read some years ago. The tales of growing up in a tight-knit Italo-American family in Rhode Island are sometimes very funny, occasionally sad and filled with finely constructed dialogue, strong narrative drive and an understanding of the social history that everyone in the book (and most everyone else in those decades) was living through. They show how immigrant traditions were diluted and sometimes even evaporated in an always churning America. But this charming book is for everybody who has followed life in the mid-20th Century. It certainly brought back a lot of memories to me and many friends and relatives.

I liked his dedication, to his wife, Diane, and “To the courageous immigrants who made it possible.’’ Of course the old cliché is that we’re “a nation of immigrants’’ – true, including the Siberian-Americans we call Native Americans or Indians.

Where is it?

“Hadley Range,’’ by Oscar Andrew Hammerstein (grandson of the Broadway lyricist), at Miller Fine Arts, South Dennis, Mass.

The Scargo Tower, on top of Scargo Hill, in Dennis. The tower offers wide views of Cape Cod.

Cynthia Drummond:New England lawns are changing with the times

Tanglewood Music Shed and lawn, in Lenox, Mass. Music lovers sit and recline on this famous lawn while listening to summer concerts of the Boston Symphony Orchestra

— Photo by Daderot

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

RICHMOND, R.I. — Love them or hate them, lawns aren’t going to disappear from the New England landscape anytime soon. Caring for those islands of green can be as casual as an occasional mowing, or as involved as season-long programs that include watering, adding nutrients and eliminating weeds and insect pests.

University of Rhode Island Professor Bridget Ruemmele teaches several turf grass courses, including management and irrigation technology. Her research focus is turf grass improvement.

In drought-prone states such as Texas, where Ruemmele worked before coming to Rhode Island, many municipalities require homeowners to use xeriscaping, landscapes composed of plants that need much less water than traditional lawns.

Ruemmele said lawns remain popular in Rhode Island because they provide areas for recreation, and they are less likely to harbor ticks.

“One of the advantages, of course, of having at least some lawn near your buildings is, you don’t have to worry as much about deer ticks [which spread Lyme disease]. That’s the big issue,” she said.

Recent hot, dry summers have resulted in watering restrictions in many towns, leaving lawns brown and stressed and prompting calls to URI from homeowners asking what they can do to counteract the effects of drought.

“We tend to have fairly regular rainfalls, but when there are droughts, the years we have droughts are when people all of a sudden go ‘Oh, maybe I should be concerned about it,’ and that’s when we get more calls and requests for information,” Ruemmele said.

Some homeowners are taking a more radical approach and reducing the sizes of their lawns. Young people may not be as interested in lawn maintenance and older couples who no longer have children at home don’t need the recreation space.

“As people seem to be aging, they’re more interested in not having as big of a lawn area,” Ruemmele said. “Some of these people who are reducing their lawn are spending hours and hours every week maintaining the alternative plants they put in, so it very much depends upon what kind of plants you decide to put in whether or not you’re going to be saving time, because if you’ve got a lawn, essentially, mow it once a week.”

The most widely used turf grass species, Kentucky blue grass, is not considered to be drought-tolerant, although Ruemmele said the original blue grasses were much tougher than the varieties sold today.

“For years, people associated it with high maintenance and that’s because, back when we were less concerned about the environment, breeders developed grasses that responded to increased irrigation and increased fertility, whereas the more common types of Kentucky blue grasses…they are the ones that were adapted to whatever the environment threw at them, so they were able to tolerate periods of stress and that’s a major emphasis that turf breeders have gone back to.”

With nutrient runoff, much of it from fertilizers, polluting coastal waters, Ruemmele said municipalities are beginning to restrict outdoor water use as well as the types of fertilizers that homeowners can apply to their lawns.

“The emphasis is on, especially, not automatically applying a fertilizer, emphasizing that you’re going to be getting a test of your [turf] fertility every couple of years and then only applying the fertilizer that’s recommended,” she said.

As an example, Ruemmele cited the intensively marketed “four step” program, in which most of the steps are usually unnecessary.

“What I think about the four-step program, is that if you don’t have grubs, you don’t need that stuff, and if you keep a nice, healthy, dense turf, that’s going to be eliminating most of any perceived weed problems that you might have, and you can eliminate that step. And so basically, the step that has fertilizer only is about the only one you really need,” she said.

Dana Millar, of West Kingston, is known for his organic lawn care service, although his company, Dana Designs, also provides conventional services to homeowners who request them. Most of Millar’s clients still ask for conventional services, but an increasing number of customers, about 65 at last count, prefer organic methods.

Organic lawn care is based on the premise that healthy turf grass requires healthy soil, so rather than applying chemicals to the grass, Millar uses a bottom-up approach, building nutrients in the soil that support the grass.

“Top down, you’re applying materials and products over the top,” he said. “Organically, you are encouraging the health of the soil, so the soil feeds the plant.”

Millar believes that organically grown grass is not only stronger, but also more resistant to environmental stressors.

“Over the period of the last two years, we’ve had greater drought than anybody had in memory and in this past year, there was more rain than anybody had in memory,” he said. “Each one of those climate-driven events stressed lawns in different ways. My organic lawns were more resilient, so in the drought, they went into drought stress later and came out of drought stress more quickly, and lots of times, didn’t need much repair, whereas lawns that may have been conventional had a harder time and they weren’t able to fend off insects. They weren’t able to fend off diseases and their recovery, in some cases, wasn’t complete. The turf was damaged and had to be completely restored.”

One of Millar’s early mentors was Earth Care Farm founder Mike Merner, a believer in the benefits of compost and the importance of nurturing the microorganisms that live in soil and make it productive.

Millar always begins an organic program with testing and amending the soil, which can be a complicated process.

“We need to know what the state of the soil is, so every organic program begins with a soil test, and we ask more from a soil test than the conventional test, because we want to know organic matter, we want to know cation exchange capacity, we want to know not only the soil pH, but its resistance to change. …This determines the type and amount of amendments that we might need to improve soil and gives us a baseline for expectations and a budget over a period of time,” he said.

While lawn care products have traditionally been marketed to men, Millar said many of the clients of his organic service are women who have taken over the responsibility of lawn maintenance from their male partners.

“I have lots of women clients who are at a point in their lives where they have the discretionary income and the authority in their households to make decisions which are usually the males,’ ” he said. “‘How are we going to treat our lawn? Why are we going to do this? I want a garden, I want to feel safe and I want my grandchildren to have the freedom to enjoy our lawn.’”

Cynthia Drummond is an ecoRI News contributor.

Timothy grass, probably named after Timothy Hanson, an American farmer and agriculturalist said to have introduced it from New England to the South in the early 18th Century. European settlers introduced it into New England in the late 1600s and by 1711 it had become known as Herd’s grass, after John Herd, a Maine farmer who began to cultivate it.

CSX buying N.E. rail network

Pan Am Railways, under a different name, bought the logo of the late lamented Pan American World Airways in 1998.

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report:

BOSTON

“The federal Surface Transportation Board has approved CSX Corp.’s application to acquire Pan Am Railways, Inc. (Pan Am). This will let CSX to move forward with their acquisition with a current closing date of June 1.

‘‘This acquisition will allow for an extended reach of CSX’s services to a wider customer base over an expanded territory. CSX says it will operate Pan Am with an increased environmental performance, including a more reliable and more fuel-efficient fleet, significantly reducing fuel consumption and improving rail’s environmental footprint in the region. Pan Am is based in North Billerica, Mass., and owns and operates a nearly 1,200-mile rail network. Its network across New England includes access to multiple ports and large-scale commodity producers. The acquisition will let CSX to expand into Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine.

“‘CSX is pleased that the STB approved the proposed acquisition of Pan Am and has recognized the significant benefits this transaction will bring to shippers and other New England stakeholders,’ said CSX president and chief executive officer James M. Foote. ‘We look forward to integrating Pan Am, their employees and the rail-served industries of the Northeast into CSX and to working in partnership with connecting railroads to provide exceptional supply-chain solutions to New England and beyond.”’

Read more in the Massachusetts Transit Magazine.

Pan Am Railways headquarters in the delightfully named Iron Horse Park, in North Billerica, Mass.

— Photo by David Maze

As shadows lengthen

“Venus’’ (oil and acrylic paint, acrylic ink, markers, fabric, photo transfer and rhinestones on canvas), by Bob Dilworth, in his show ‘‘Another Place,’’ at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, May 7-Sept. 7.

He says:

“My paintings employ an aesthetic gesture towards moments in history that run parallel to current times, often intersecting and exploring hidden and deeper meanings of my experience as an African-American male.’’