CVS seems to be reimagining its telehealth offerings

Telemedicine as imagined in 1925.

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report:

“Woonsocket, R.I.-based CVS Health has filed applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office seeking protections to sell a wide range of downloadable virtual goods. The application would also secure trademark protection for all the company’s logos, images, branding, clinics, services, programs, and media online and in online virtual worlds.

“This patent would protect their downloadable virtual goods including merchandise created through ‘blockchain-based software technology,’ ‘crypto-collectibles,’ ‘online digital artwork’ and ‘non-fungible tokens,’ also known more widely as NFTs. While CVS has not publicly laid out a strategy for its engagement with these online goods, the applications do offer some clues about how this new technology would be used by them, including setting up ‘an online non-downloadable platform for users to browse, create, modify and manipulate virtual retail consumer goods.’

“The company would also seek to provide information and news on topics such as health and wellness and offer health care services ‘in virtual reality and augmented reality environments,’ including non-emergency medical treatment, wellness and nutrition programs, personal assessments, personalized routines, maintenance schedules and counseling services. These offerings would likely serve as an extension, or reimagining, of CVS’s telehealth efforts, which have been forced to ramp up due to the COVID pandemic.’’

Telemedicine in rehabilitation

— Photo by Ceibos

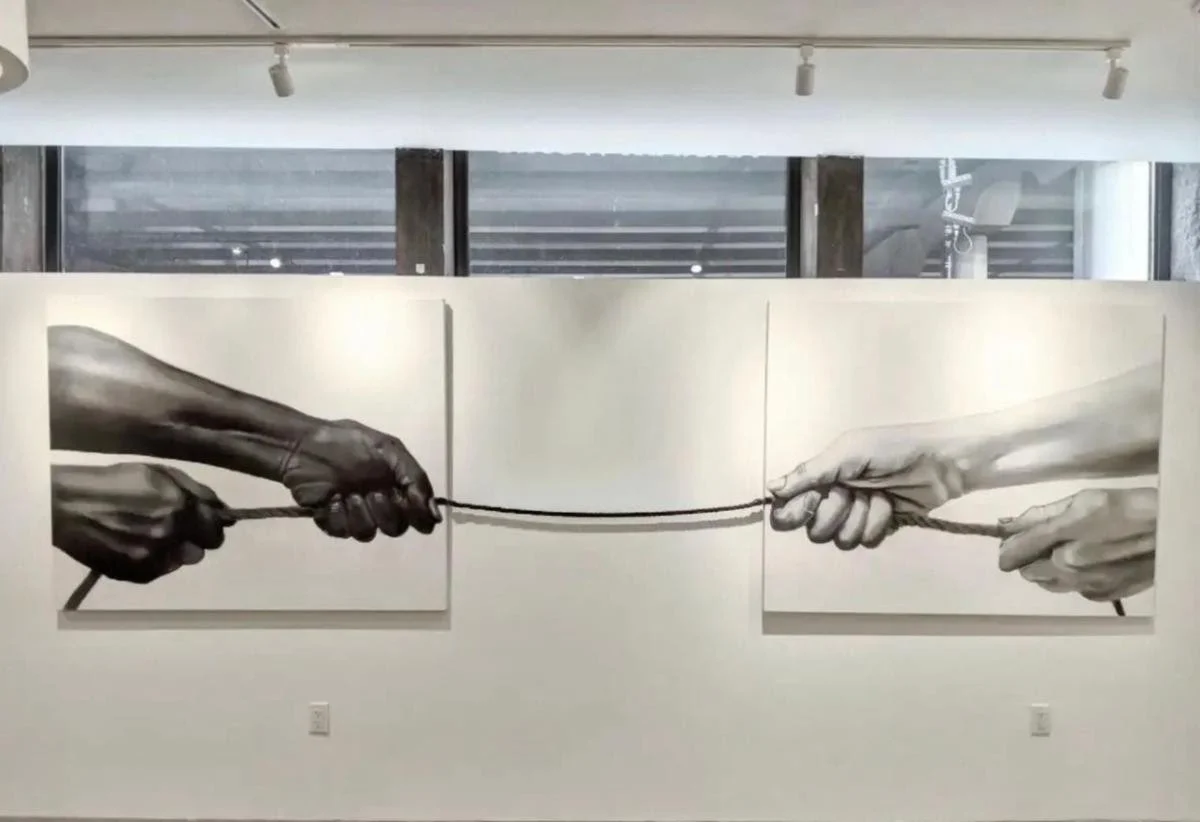

Who can pull hardest?

Part of Cedric "Vise1" Douglas's “Streets Memorial Project,’’ at The Rivers School, Weston, Mass., through May 16.

The school says:

"Much of his work aims to engage the audience in meaningful conversations and document powerful moments in history. ‘The Street Memorial Project’ is a collection of work exploring police brutality and racial injustice. His other projects include ‘The People’s Memorial Project,’ a pop-up public video projection installation addressing controversial public monuments, and the ‘Tools of Protest’ project, where printed rolls of caution tape reading ‘I can’t breathe’ and ‘Don’t shoot’ are passed out to protesters."

The Weston Observatory, in Weston. Part of Boston College, it’s an important facility for measuring earthquakes.

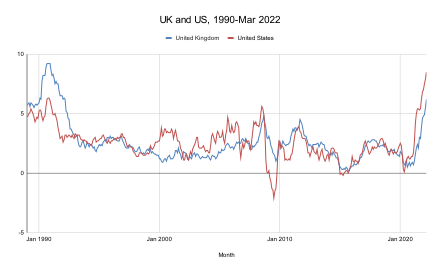

David Warsh: Trying to figure out how to measure ‘inflation’

British and U.S. monthly inflation rates from January 1990 to February 2022.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

President Biden calls it Putin’s inflation. Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell says the problem began with the pandemic. Harvard University economist Lawrence Summers blames the Fed. Who’s right? Some 250 years of interplay between the science of pneumatics and its technological applications were the background against which economist Irving Fisher, in 1928, expanded the modern usage of the term “inflation” to mean something more than rising prices. Fisher is not a bad place to begin to look for an answer.

Arguments about whether or not such a thing as a vacuum can exist; quicksilver (meaning mercury); barometers; j-tubes; air pumps; valves, cylinders, and plungers; hot air balloons; footballs; the discovery of inert gases (starting with helium); the manufacture of incandescent light bulbs; pressure cookers; inflatable tires – these topics or objects became familiar before Fisher took advantage of relationships among pressure, volume, and temperature of gases, itself by then vaguely understood, in order to attach a new meaning to an old word.

“Anyone… reading [The Money Illusion] (Adelphi, 1928) by Fisher, or other books on monetary affairs published in this period, may have some difficulty with terminology” wrote Fisher’s biographer, Robert Loring Allen, many years after the fact. “For more than a generation, the words ‘inflation’ or ‘deflation’ [had] usually meant increasing or decreasing prices.” But in The Money Illusion. Allen wrote, Fisher coined new meanings: “the words inflation and deflation refer to the money supply, not to prices. Money inflates and in consequence prices rise and a deflation in the money supply causes falling prices.”

It was the first and only book about the subject that Fisher, a prominent Yale University professor and tireless reformer, would write for the general public. He was at pains to explain what he meant.

As I write, your dollar is worth about 70 cents. This means 70 cents of pre-war buying power. In other words, 70 cents would buy as much of all commodities in 1913 as 100 cents will buy at present. Your dollar now is not the dollar you knew before the War. The dollar always seems to be the same but it is changing. It is unstable. So are the British pound, the French franc, the Italian lira, the German mark, and every other unit of money. Important problems grow out of this great fact – that units of money are not stable in buying power.

A new interest in these problems has been aroused by the recent upheaval in prices caused by the World War. This interest nevertheless is still confined largely to a few special students of economic conditions, while the general public scarcely yet know that such questions exist.

Why this oversight?.. It is because of “the Money Illusion”; that is, the failure to perceive that the dollar, or any other unit of money, expands or shrinks in value. We simply take it for granted that “a dollar is a dollar” –that “a franc is a franc” that all money is stable, just as centuries ago, before Copernicus, people took it for granted that that the earth was stationary, that there was really such a fact as a sunrise or a sunset. We know now that sunrise and sunset are illusions produced by the rotation of the earth around its axis, and yet we still speak of, and even think of, the sun rising and setting!

Fisher is at pains to illustrate the illusion. He visits Germany with an economist friend, where the two interview 24 men and women. Only one considered that rising prices have anything to do with the government’s management of its currency.

They tried to explain it by ‘supply and demand’ of other goods, by the blockade; by the the destruction wrought by the War; by the American hoard of gold; by all manner of other things – exactly as in America when, a few years ago, we talked about “the high cost of living,” we seldom heard anybody say that a change in the dollar had anything to do with it.

Fisher went on to explain the system of gold, paper money, and bank “deposit currency,” as bank credit was known at the time. He noted that the Federal Reserve System had recently taken responsibility for the oversight of the money supply that occurred via the purchase and sale of government bonds by its Open Market Committee. He noted the suspension of the international gold standard during the World War and recommended its early resumption. Above all, he urged the adoption of price indices, carefully collected by government agencies, with which to measure changes in “the cost of living,” or, as he puts it, “fluctuations in the value of money.”

But the year was 1928. A world-wide boom was on. Fisher was already somewhat isolated from his university colleagues by his enthusiasm for business (he had sold his Rolodex card-filing system to Remington Rand Corp. and was trading millions in stocks). When the Depression began, instead of hedging his bets, he pursued business as usual a little while longer, and gradually lost his entire fortune. Meanwhile, economists turned their attention to John Maynard Keynes.

“It was particularly unfortunate,” Robert Dimand, of Brock University, has written, “that Fisher lost the attention of the economics profession, the public, and even his Yale colleagues just when he has something interesting to say about with what had gone wrong with his predictions and the economy,” to wit his article “The Debt-deflation Theory of the Great Depression” in the first volume of Econometrica, in lieu of an Econometric Society presidential address. He died in 1947.

But Fisher’s espousal of the value of index numbers to monitor variations in purchasing power stuck, as did his enthusiasm for the monetary, as opposed to real, explanation of rising prices. In Monetary Illusion, Fisher never mention Boyle; he offers a more homely analogy instead: “If more money pays for the same good, their price must rise, just as if more butter is spread over the same slice of bread, it must be spread thicker, the thickness representing the price level, the bread the quantDity of goods.” Twenty five years later, though, a master expositor of Keynesian economics, George Shackle, of Liverpool University, wrote,

How did we come to adopt the portentous word “inflation” to mean no more than a general rise in prices? I think this usage must have had its origin in a particular theory of the mechanism or cause of such a rise. When a given weight of gas is released from a steel cylinder into a large silk envelope, there may appear to be more gas, but in important senses, the amount of gas is unchanged. In a somewhat analogous way, we can make our total stock of currency spread over a larger number of paper notes, but this action in itself will not increase the size of the basket of goods (where various good are present in fixed proportion) that this total stock of currency would exchange for in the market…. Some such image as this may perhaps have been n the mind of the man, who first spoke of inflating the currency. This idea, that the general price level is closely related to the ostensible, apparent size of the money stock… has become formally enshrined in what is called the Quantity Theory of Money.

It’s been nearly 40 years since I published The Idea of Economic Complexity. What have I learned, in all the years since, about explaining generally rising prices? At least this: By all means let us continue to measure money and talk pneumatics. In hopes of narrowing differences of opinion, though, let us keep looking for something real and general in the economy to measure as well. I expect that the Fed has made a pretty good beginning on that.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

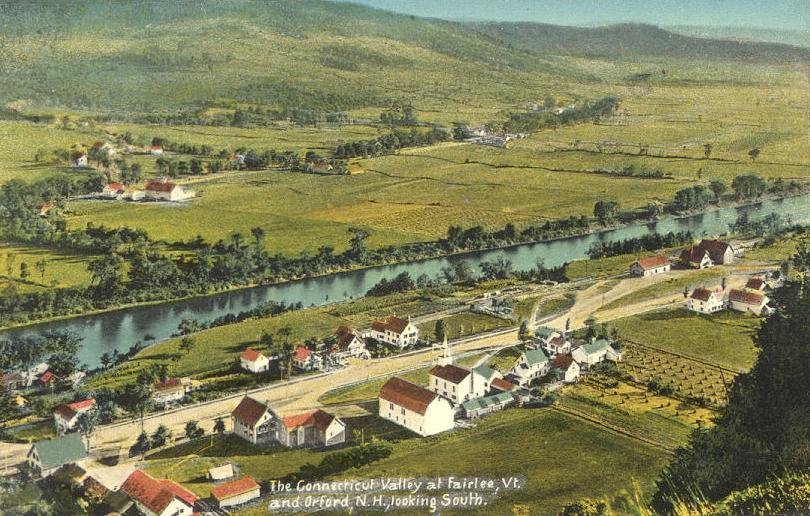

Balanced environments

1907 postcard

Statue and memorial to Civil War dead in Claremont, N.H.

— Photo by Djmaschek

"When people who have never lived in New Hampshire or Vermont visit here, they often say they feel like they've come home. Our urban center, commercial districts, small villages and industrial enterprises are set amid farmlands and forests. This is a landscape in which the natural and built environments are balanced on a human scale. This delicate balance is the nature of our ‘community character. It’s important to strengthen our distinctive, traditional patterns to counteract the commercial and residential sprawl that upsets this balance and destroys our social and economic stability.’’

— Richard J. Ewald, author of Proud To Live Here in The Connecticut River Valley Of Vermont and New Hampshire. He lives in Putney, Vt.

Sacketts Brook in downtown Putney

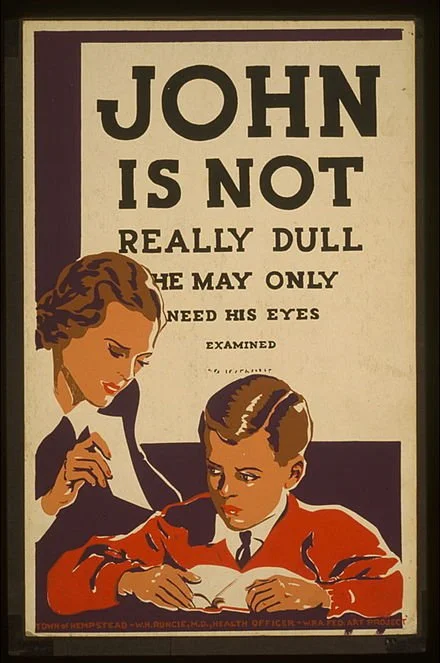

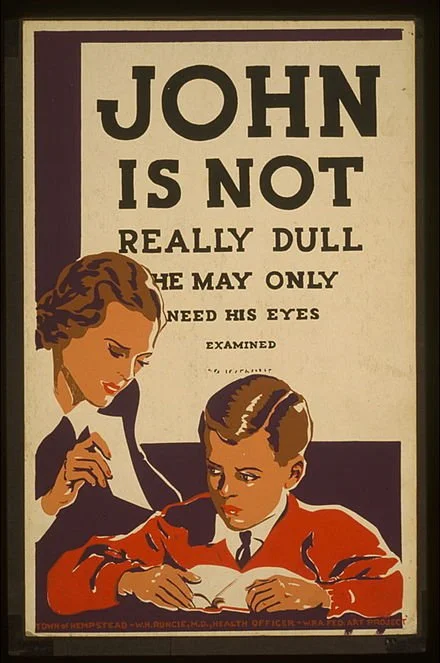

Chris Powell: Many poor kids can’t see well and neither can government

Public education poster urging eye exams for children — Works Progress Administration, circa 1937

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Someday, if the governor and state legislators ever tire of coddling the state employee unions and if the president and Congress ever tire of coddling investment banks and military contractors, maybe they should note what happened recently at Silver Lane Elementary School in East Hartford.

Most of East Hartford's students are from poor households and most have limited if any medical insurance. So a wonderful charity from Los Angeles called Vision to Learn has been visiting the town's schools, offering students free vision screenings and eye examinations, free optometric prescriptions for those who need them — and then free prescription eyeglasses too.

Participation is up to parents, but about two-thirds of Silver Lane Elementary's 300 students have participated in the program and three weeks ago 53 of them received their free prescription glasses.

That is, about 18 percent of the school's student population needed glasses but didn't have them, and the percentage of students in need at the school is almost certainly higher because another hundred or so students weren't examined.

Vision to Learn's premise is compelling: that children who can't see well aren't likely to learn as well as they should, that as many as a quarter of the nation's children will need glasses while they are in school, and that without the glasses they need, poor children may be misdiagnosed with behavioral problems and leave school prematurely.

If the Silver Lane Elementary experience of unmet vision need is projected nationally and considered along with the other unmet medical needs of students from poor households, the situation should horrify.

State government is aware of the problem. The state Public Health Department finances 90 student health clinics at schools in 28 towns, and a study group including state officials and state legislators has just reported that 157 more schools in poorer municipalities very much could use clinics as well. Legislation pending in the General Assembly would appropriate $21 million for increasing or expanding school clinics. That's nowhere near enough to address the need fully, especially since most of the clinics don't offer vision and dental services.

Meanwhile, the legislature seems ready to appropriate what is estimated at more than $300 million for raises and benefit increases for unionized state employees, though they never lost a paycheck during the virus epidemic. Meanwhile, the employees of community social-service agencies remain poorly paid and underinsured as they care for the needy at half the cost of state government employees.

A bigger disgrace here may be that amid its creation and distribution of infinite money for less compelling purposes, the federal government has not resolved to finance health clinics for all school systems in the country.

The biggest disgrace may be that more than 50 years after the federal government declared a war on poverty, there is still so much of it with so many people unable or unwilling to take care of their children. What passes for liberalism now pursues more vigorously what it sees as grander causes: unrestricted abortion and transgenderism.

xxx

A less expensive but more difficult issue of children's health also faces the General Assembly: whether state Medicaid insurance, known as HUSKY coverage, should be extended to more children living illegally in Connecticut.

Last year the legislature extended coverage to illegal residents 8 and younger, a strange compromise of budgeting. For except for the expense, why should 8-year-olds be covered but not children from 9 to 17?

The best arguments against extending coverage are that its cost is uncertain, that it will facilitate more violation of immigration laws, and that it may draw to Connecticut more immigration lawbreakers from other states.

The best arguments for extending coverage are that sick children will be treated anyway by walking into a hospital emergency room, with the cost passed along to other patients; that Medicaid insurance will treat illness before it becomes more expensive; and basic decency.

The cost of the new state employee union contract hasn't been fully calculated either, but the legislature will approve that one easily.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Vermont ‘bows to nothing’

The Old Constitution House at Windsor, where the Constitution of Vermont was adopted on July 8, 1777

“Vermonters are really something quite special and unique….This state bows to nothing: the first legislative measure it ever passed was ‘to adopt the laws of God … until there is time to frame better.’’

— John Gunther in Inside USA (1947)

‘Seasons and Chaos’

“{Gas} Compressor Station” (oil on panel), by Yvonne Troxell Lamothe, in her show “Seasons and Chaos,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 1-June 1. {The painting refers to controversial compressor along Boston Harbor in Weymouth, Mass.}

She says: "Aware of the vulnerability of our environment by abusive corporate mandates and irresponsible policy, I make statements through my work that hopefully cause concern and evoke the sense of urgency I feel."

First vegetable crop of spring

“Fiddle ferns {aka fiddleheads}, if you know where to find them {in wet places}, are the first delicacy of spring, appearing even before asparagus. Plunge them briefly into rapidly boiling water, and serve with butter, salt, and if you like, lemon juice. Chapped almonds may be added, or the ferns may be served on hot buttered toast.’’

From Favorite New England recipes (1972), by Sara B.B. Stamm.

Llewellyn King: The new normal will take time, not politics

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Loud detonations are going off in the economy. When the debris settles, new realities will emerge. We won’t return to the status quo ante, although that is what politicians like to promise.

After great cataclysmic events — wars, natural disasters or the impact of new technologies — we need to acknowledge the realities and find the opportunities.

The inflation that is shaking the world is the inflammation that arises as markets seek equilibrium — as markets always do.

The greatest disrupter has been the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ramifications of how it has reshaped economies and societies are still evolving. For example, will we need as much office space as we did pre-pandemic? Is the delivery revolution the new normal?

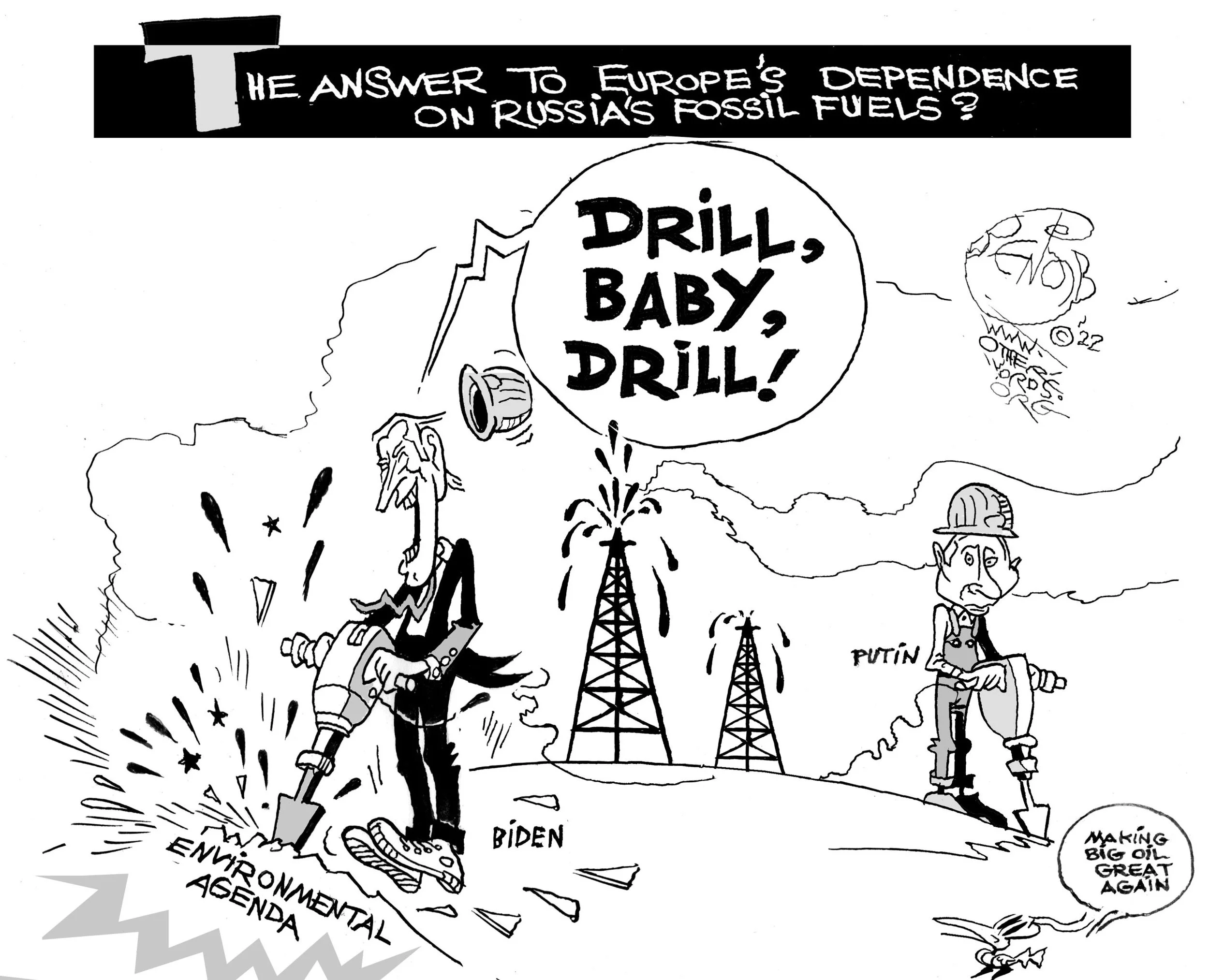

Russia’s war in Ukraine has added to the pandemic-caused changes before they have fully played out. They, in turn, were playing out against the larger imperatives of climate change, and the sweeping adjustments that are underway to head off climate disaster.

Some political actions have exacerbated the turbulence of the economic situation, but they aren’t the root causes, just additional economic inflammation. These include former president Donald Trump’s tariffs and President Biden’s mindless moves against pipelines, followed by attempts to lower gasoline prices, or wean us from natural gas while supplying more natural gas to Europe.

In the energy crisis (read shortage) of the 1970s, I invited Norman Macrae, the late, great deputy editor of The Economist, to give a speech at the annual meeting of The Energy Daily, which I had created in 1973 — and which was then a kind of bible to those interested in energy and the crisis. Macrae, who had a profound influence in making The Economist a power in world thinking, shared a simple economic verity with the audience: “Llewellyn has invited me here to discuss the energy crisis. That is simple: the consumption will fall, and the supply will increase. Poof! End of crisis. Now, can we talk about something interesting?”

Of the many, many experts I have brought to podiums around the world, never has one been as warmly received as Macrae. Not only did the audience stand and applaud, but many also climbed on their chairs and applauded. I’m not sure Washington’s venerable Shoreham Hotel had ever seen anything like that, at least not at a business conference.

In today’s chaotic situation with political accusations clashing with supply realities, the temptation is to find a political fix while the markets seek out the new balance. Politicians want to be seen to do something, no matter what, and before it has been established what needs to be done.

An example of this was Biden increasing the allowed amount of ethanol derived from corn and added to gasoline. It is so small an addition that it won’t affect the price at the pump, but it might affect the price of meat at the supermarket. Corn is important in raising cattle and feeding large parts of the world.

There is a global grain crisis as a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which is a huge grain producer. Parts of the world, especially Africa, face starvation. The last thing that is needed is to sop up American grain production by burning it as gasoline.

We are, in the United States, gradually moving from fossil fuels to renewables, but this is going to move our dependence offshore, and has the chance of creating new cartels in precious metals and minerals.

Essential to this move is the lithium-ion battery, the heart of electric vehicles and battery storage for renewables, and its tenuous supply chain. Lithium has increased in price nearly 500 percent in one year. It is so in demand that Elon Musk has suggested he might get into the lithium mining business.

But lithium isn’t the only key material coming from often unstable countries: There is cobalt, mostly supplied from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; nickel, mostly sourced in Indonesia; and copper, where supply comes primarily from Chile.

Across the board, supplies will increase, and demand will decline. Equilibrium will arrive, but vulnerability won’t be eliminated. That is an emerging supply chain constant as the economy shifts to the new normal.

The aftershocks of the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine will be felt for a long time — and endured as inflation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Too wet to plant yet

“Spring Field’’ (acrylic on canvas), by Hannah Bureau, in her show “Open Air,’’ at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt. through May 22. A native of Paris, she’s now based In Waltham, Mass.

Sam Pizzigati: Time for a Tom Paine tax program

BOSTON

From OtherWords.org

The great pamphleteer of the American Revolution, Thomas Paine, had much more on his mind than independence from the British.

Paine spent his life, Jeremy Bearer-Friend and Vanessa Williamson write in a new paper, advocating for a democratic “commonwealth” that shared the wealth. He wanted to free people “from domination both political and economic.”

In particular, Paine believed that a wealth tax on grand private fortunes could prevent the emergence of an anti-democratic elite. This tax season, over two centuries later, we may finally have a president who’s taking Paine to heart.

In its new budget proposal, the Biden administration is calling for a new “Billionaire Minimum Income Tax.” The White House isn’t calling this proposal a “wealth tax,” but we should.

Under Biden’s plan, Americans worth over $100 million would be expected to pay an annual tax of at least 20 percent on their total income — including any increases in the value of their stocks, bonds, and other liquid assets.

These liquid assets make up the bulk of every billionaire fortune, but increases in their value go totally untaxed until their wealthy owners decide to sell them off. That gives “ultra-high-net-worth households,” the White House points out, the ability to have their gains “go untaxed for decades or generations.”

Let’s take the example of a CEO who pockets $20 million a year in salary. He might pay a 20 percent tax on that $20 million.

But if this executive also holds stocks worth $10 billion and those stocks gain 10 percent in value — an extra $1 billion — then the vast majority of our CEO’s real income would go completely untaxed.

Under Biden’s plan, that CEO would have to pay taxes on his CEO pay and all his stock gains. That would hike his federal tax tab from $4 million to $204 million.

America’s 700 or so billionaires, the Biden administration notes, saw “their wealth increase by $1 trillion” last year. Yet current law has billionaires paying “just 8 percent of their total realized and unrealized income in taxes.”

That’s right: Billionaires pay at a lower overall rate than average Americans.

“Under current law, when an American worker earns a dollar of wages, that dollar is taxed as they earn it,” the White House explains. “But when a billionaire earns income because their investments increase in value, that gain is too often never taxed at all.”

Firefighters and teachers, adds the White House, “can pay double” the rate billionaires pay.

The Biden tax plan is actually taking much the same approach that Tom Paine took with a wealth tax proposal he first put forward in 1792, tax historians Bearer-Friend and Williamson argue.

Under Paine’s plan, the pair calculate, today’s billionaires would pay a tax of about 3.5 percent of their personal fortunes during normal market years. That figure is remarkably close to the tax rates that appear in wealth tax proposals that Senators Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass) and Bernie Sanders (I.-Vt.) have advanced.

Biden’s plan doesn’t take that big a bite. But it does represent a significant step toward taxing the wealth of America’s wealthiest, says Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman.

Mega-billionaires Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, and Elon Musk, Zucman reminds us, together paid just $1.5 billion in federal income taxes over the five-year period that ended in 2018. Under the Biden proposal, this trio would pay at least 100 times more over the next decade or so.

Paine believed that extreme wealth undermines “the ability of citizens to choose their leaders,” Bearer-Friend and Vanessa Williamson argue, a condition that many will easily recognize today. Freedom, in Paine’s view, “meant both lifting the poor from penury and dependence” and eliminating the “vicious influence” of fiercely concentrated wealth.

Tom Paine had it right. And if Congress takes up Biden’s new tax plan, we can too.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

‘Climbed into my head’

Spring rusts on its skinny branch

and last summer's lawn

is soggy and brown.

Yesterday is just a number.

All of its winters avalanche

out of sight.

What was, is gone.

Mother, last night I slept

in your Bonwit Teller nightgown.

Divided, you climbed into my head.

— From “The Division of Parts,’’ by Anne Sexton (1928-1974), Boston area Pulitzer Prize-winning poet

Sunset for the demented

Sunset at Menemsha Harbor

“Menemsha. An old Native American name freely translated as “place where demented aliens gather to applaud the setting of the sun while eating supper in the sand.’’

— Arnie Reisman, in On the Vineyard II (1990)

Picturing Pownal

“Sunday, 1937 ” (oil on canvas), by Marion Huse, in the show “Marion Huse: Picturing Pownal’’, at the Bennington (Vt.) Museum through June 22.

The museum says:

“Huse’s work spanned forty years and a variety of styles and subject matter, from Regionalism in the 1930s to a more Expressionistic style that she developed in the post-war years. A selection of her prints, depicting historic local landmarks and covered bridges, will be shown alongside her paintings.’’

Former Country Store in Pownal, Vt.

— Photo Doug Kerr

Buzzards Bay riviera

Sippican Harbor, in Marion, Mass. on the South Coast

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I read in GoLocalProv the other week that Residential Properties, the Providence-based company that has a particular affection for high-end customers, has set up an office in Westport, Mass. No wonder! The South Coast region has drawn many more summer and year-round home buyers in the past few years, drawn by the beautiful rolling countryside (with vineyards and farms), Buzzards Bay, which is remarkably warm in the summer, and the ease of getting to the area.

It’s lured a lot of people who in prior years might have gone to Cape Cod or the Hamptons.

This migration has shot real-estate prices through the roof on the South Coast (in which I’d include the coastal towns from Little Compton all the way to Marion (but excluding New Bedford). The big surprise to me is how long it took so many people to discover it.

Dartmouth High School logo

One man’s honor, another’s insult

The voters of Dartmouth, Mass., on the South Coast, have backed – 4,048 to 969 -- the retention of the almost-abstract face of a Native American brave as the logo for the town’s high school.

Some members of the locally dominant Wampanoag Tribe wanted it gone. But other members find it a dignified and respectful reminder of the original inhabitants of what became Dartmouth. The logo was designed by Wampanoag Tribe member Clyde Andrews.

Taking offense can be an unpredictable and highly individual thing.

‘Shapeshifting beauty’

“Harmony” (oil and wax on copper panel), by Brookline, Mass.-based Nora Charney Rosenbaum, in her show “The Language of Birds,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 1-June 1.

“When I see a colony of cormorants silhouetted on seashore rocks, their shapes can seem like cryptic hieroglyphs from some arcane mythology. Looking closer, they become recognizable as individual characters in a dialog of social interactions.

“In my painting I try to capture their rangy, shapeshifting beauty. Using oil paint and sometimes wax and sand on copper-covered panels helps me express their liveliness."

She says in her artist statement:

“For me the process of painting is the solving of problems - color, form, texture and composition. My technique is to layer oil paint in thin glazes or sometimes mixed with wax over chemically treated copper to produce an optically complex surface. Light passes through some layers and reflects off others to give an impression of atmosphere and luminescence.

“Painting is always a leap into the unknown. Trying to capture the depth, motion and sense of transparency in this ephemeral world is a challenge.’’

Boston Harborwalk

“East Boston Boat Yard” (photo), by Alan Strassman, in his show “Boston Harbor: Views From the Shoreline’,’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 1-June 1.

Mr. Strassman explains:

"For more than 30 years, the City of Boston, Massachusetts state agencies, private developers and waterfront residents have been working together to create the Boston Harborwalk – a pedestrian-friendly walkway running more than 40 miles from Dorchester in the south to Winthrop in the north.

“These are some scenes from the edge of the harbor."

New England's indigenous horse

A young Morgan horse

At the Morgan Horse Farm, an historic breeding facility in Weybridge, Vt. Since 1907, it has been an official breeding site for the Morgan horse, one of the first American-bred horse breeds, and Vermont's official state animal. The breeding program was established in Burlington in 1905, and moved to this site in 1907 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and is now run by the University of Vermont. The farm is in the National Register of Historic Places.

“Close-coupled, sturdy, winsome, with a well-defined head and delicate ears, the Morgan horse is New England’s indigenous breed. The line goes back to a small bay stallion owned by Justin Morgan, a Vermont schoolteacher-farmer, who acquired the remarkable colt in 1795. For 32 years this stalwart animal served honorably under saddle and in harness. All Morgans descend from him.’’

Maxine Kumin (1925-2014) , Warner, N.H.-based poet and horse farmer, in Arthur Griffin’s New England: The Four Seasons

Free lunch

“In the Clover” (watercolor), by Jeanette Fournier, a North Woodstock, N.H., painter.

Woodstock Inn Brewery, in North Woodstock

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel