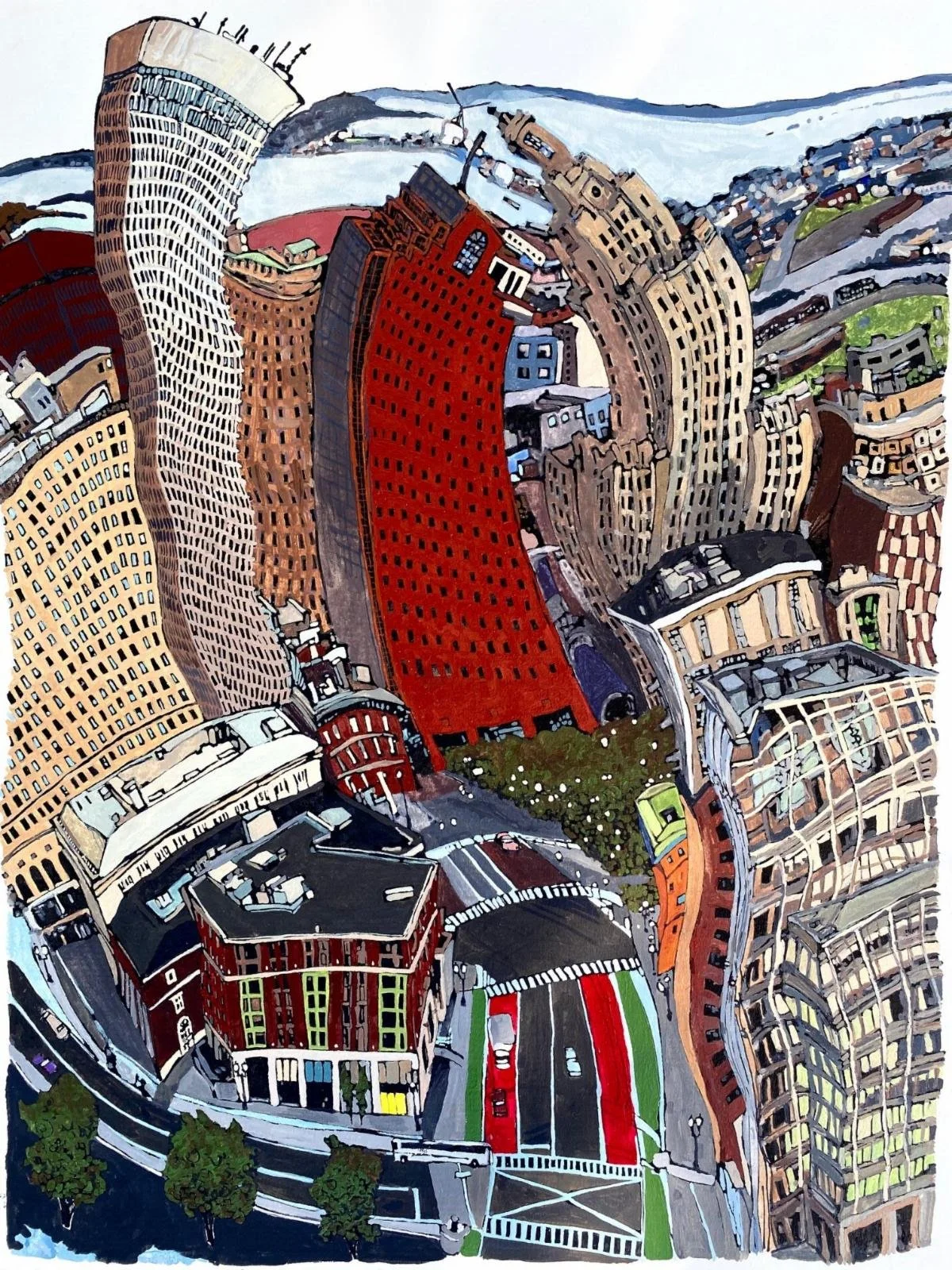

Plastic Providence

This work by Rhode Island artist Jim Bush can be seen at the Providence Art Club March 6-25.

Here’s his description of his background:

“Jim Bush grew up in Cambridge, Mass., and graduated from Kenyon College with a double major in Studio Art and Political Science. He is an award-winning artist, member of the Providence Art Club and a former member of the Sakonnet Artists Cooperative, in Tiverton, R.I. His editorial cartoons appeared in The Providence Journal from 1994-2012. Nationally his cartoons have appeared in the Washington Post National Weekly Edition, The Dallas Morning News and he has drawn for the Tribune Media Services College Press Syndicate.

“In 2007, Jim purchased a building in the historic district of downtown Warren, R.I. and spent a year converting it into an art studio and gallery. Jim focuses now on his fine art painting, primarily acrylic and watercolor. He enjoys painting animals, seascapes, landscapes, farm scenes, architecture -- life around him. His style continues to reflect his cartooning foundation, often displaying his subjects in a light-hearted and off-beat way.’’

The end of his quarrel and road

Robert Frost’s grave, in Bennington, Vt.

— Photo by Nheyob

One of the most famous — and misunderstood — poems in the English Language, first published in 1915

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

— “The Road Not Taken,’’ by Robert Frost

In The Paris Review critic, poet and essayist David Orr described some of the misunderstanding this way:

“The poem’s speaker tells us he ‘shall be telling,’ at some point in the future, of how he took the road less traveled…yet he has already admitted that the two paths ‘equally lay / In leaves’ and ‘the passing there / Had worn them really about the same.’ So the road he will later call less traveled is actually the road equally traveled. The two roads are interchangeable.’’

Like ‘moving through a landscape’

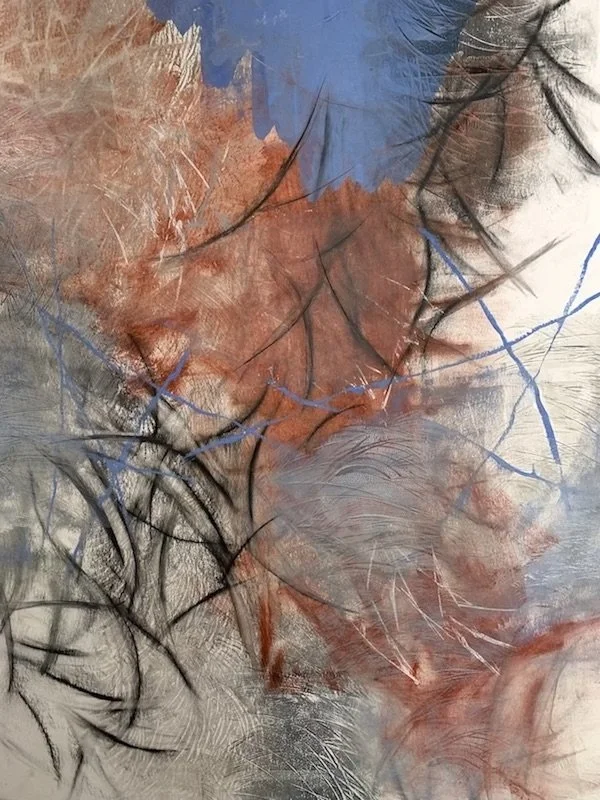

“Aerial View” (cold wax, oil stick, graphite on bristol board), by Deborah Pressman, a Chestnut Hill, Mass.-based artist.

“Landscapes and multiple images produced by double- and triple-image photography are recurrent themes in my work. I am interested in expanding and compressing the depth of field: seeing the micro and the macro world simultaneously. Weather, changing seasons, the profusion of textures and shapes within the natural world are constant sources of wonders and inspiration. My goal is the create a visual experience as though moving through a landscape.’’

“In June 2017 I retired after 33 years of practicing medicine. Throughout my medical practice I continued to make art – I took master classes in silversmithing for 8 years with renowned silversmith Michael Banner. More recently, I have taken prolonged workshops with Lisa Pressman (no relation) in encaustic painting, and printmaking workshops with Joyce Silverstone at Zia Mays and Dan Weldon at North Country Studio Workshops, in Bennington, Vt. I currently participate in a monthly critique group led by Patricia Miranda. I am fully committed to art making, working daily in my studio.’’

Chestnut Hill (Mass.) Reservoir in January. View of Boston College's Alumni Stadium across the water.

— Photo by Marball135

Start those nippy Maine mornings well-carbed

The Kennebec River flowing along downtown Augusta, Maine’s capital.

“I’m from Maine. I eat apple pie for breakfast.’’

— Rachel Nichols, actress and model, was born in Augusta in 1980.

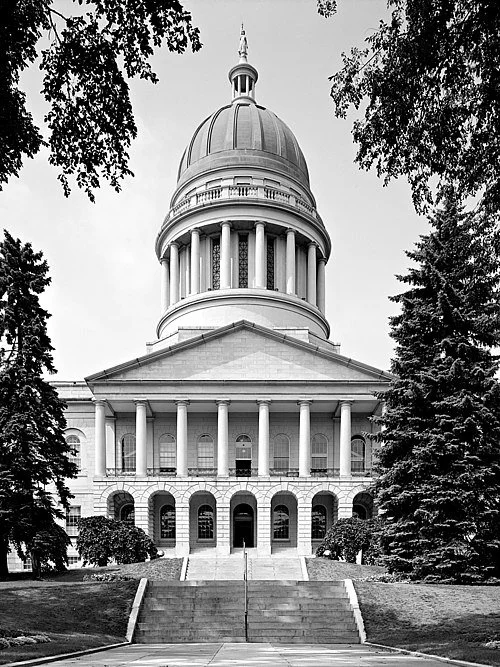

Maine State House, designed by Charles Bulfinch, built 1829–1832. Bulfinch more famously designed the Massachusetts State House. Maine was part of the Bay State until 1820.

William Morgan: Paying homage to a young Maine hero

— Photo by William Morgan

Pine Grove Cemetery, in Appleton, Maine, is not easy to find. This rural community beyond the Camden Hills has a post office, a library and a fast-running stream where a mill once stood; the town office is open only three days a week. An elementary school serves the town, but middle and high- school students must travel by bus to Camden.

My wife and I drove down a road with an Abenaki name and across the Saint George River, up a steep hill to a ridge, in search of a barely marked turnoff. We bumped along a rutted dirt track to one of those ancient New England burying grounds with slate steles carved with primitive angels.

The grave we searched for was not under the elegiac oaks and dark conifers, but in the new part. This half of the cemetery has few trees, and the gravestones tend to be more elaborate, colored and polished. Many are adorned with plastic flowers, teddy bears and other tributes of contemporary mourning. The vertical marble slab we were visiting had not been tended in a while. Veterans of Vietnam and the Persian Gulf rest nearby.

On Feb. 26, 2006, Joshua Humble, a specialist in the famed winter warriors of the 10th Mountain Division, was killed near Baghdad by a roadside bomb – the 2,385th U.S. soldier to die in Iraq. Humble had just turned 21. A regimental honor guard stood by his coffin at a funeral home in Belfast, then followed the hearse to Appleton for burial.

Thousands of kids died in the Iraq War. What was so special about one from an agricultural community in Maine? Was he like so many soldiers: high school, limited local prospects and maybe a desire to get away from small-town life?

A newspaper obituary shows a face of aching innocence. His middle initial was intriguing: Did the “U.” stand for Ulysses, Uriah or maybe Uncas? His stone revealed that the U. was for Ut, an Asian anomaly in an all-white Appleton.

Josh Humble is remembered primarily through an ongoing memorial on Legacy.com. There have been 47 comments since Humble’s death, most from buddies in arms who speak of his heroism. Five years ago, Julie Lee, from the Maine town of Washington, recalled Josh as “a respectful kid with a fun sense of humor.” She added, “Your sacrifice for our country will not be forgotten.”

Yet recent war deaths such as Humble’s have been forgotten – only an average of three notes a year on an obituary, and memorial Web site is not much of a remembrance. These are the young men and women of a volunteer military who carried the load while the rest of us did not face roadside bombs in the desert.

I was drafted in 1966 but was determined not to be sent to Vietnam. After passing my Army physical, I implored an orthopedic surgeon – my college roommate’s father – to write a letter outlining how a skiing injury would make me unfit for basic training. Contemporaries who did not have such connections went to Southeast Asia, and of course some died there. Maybe unforgetting one Maine soldier would offset the shadow of my not having donned a uniform.

Since reading of Josh Humble’s death 15 years ago, we had talked of paying our respects at his final resting place. It was a bucolic, almost secret, graveyard on a perfect autumn day. I was glad we went. But as I placed a stone on Josh’s marker, I did not feel peace or closure. Instead, I was overcome by a rage that took me back to the protests of my youth. For me, Joshua Humble symbolizes the tragedy of nonsensical wars that robbed hundreds of places like Appleton of their young people and their future.

William Morgan is an architectural writer and a resident of Providence who has taught at Princeton University, the University of Louisville and Brown University, among other institutions. He went to camp in Litchfield, Maine, in the 1950s.

Camden, Maine, near Appleton, viewed from the summit of Mt. Battie, one of the Camden Hills.

— Photo by Dudesleeper

Valley grandeur

“Autumn Woods, Oneida County, State of New York” (oil on linen), by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), in the show “The Poetry of Nature: Hudson River School Landscapes from the New York Historical Society,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art through May 22.

Look at the elm trees!

Eversource touts New London as offshore-wind staging site

Rendering of State Pier project in New London

From reporting by The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Eversource Energy has made progress in its siting process for wind-power turbines in the Atlantic. According to Eversource CEO Joseph R. Nolan Jr., State Pier in New London, Conn., is a ‘superior location’ to assemble these turbines, with the company preparing to spend billions of dollars in the coming years developing wind power in the region. Expansion of State Pier to make the location suitable to wind-turbine assembly is in the works.

Eversource spokeswoman Caroline Pretyman says that State Pier’s proximity to offshore leases presents a ‘strategic opportunity’ for the industry to site facilities for wind-turbine parts assembly. This project is associated with Eversource’s development of Revolution Wind, a 704-megawatt offshore wind farm that will supply 400 megawatts of power to Rhode Island and 304 megawatts to Connecticut. Nolan said supply-chain problems over the past few months have driven up costs higher than expected but he remains confident in Eversource’s upcoming projects and optimistic about their environmental impacts.

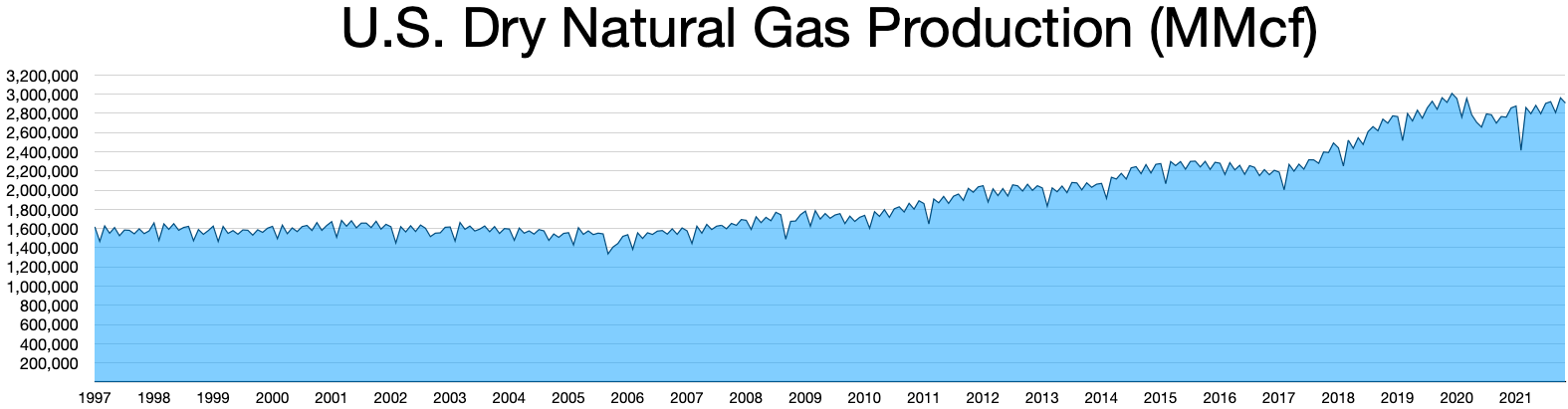

Llewellyn King: Russian assault on Ukraine emphasizes need for more U.S. natural-gas production

Liquified natural gas tanker.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Natural gas has been getting short shrift in the U.S. energy debate. It deserves better. Much better.

It has been battered by environmentalists who oppose exploration and the pipelines to get it to market. They are attempting to evict natural gas and force utilities into reliance on intermittent renewables.

But events in Europe may cause a rethink about natural gas, both as a transition fuel in the United States and a foreign-policy tool.

Even before Russia's invasion of Ukraine, natural gas was in short supply in Europe after a summer of wind drought caused European utilities to scramble for natural gas – prices went up 400 percent. Russia added to the crisis by reducing volumes flowing through the Ukrainian system that serves much of Europe.

Fear of Russian weaponization of natural gas has been an ever-present reality. Now Europe trembles, especially Germany which has just closed its last three nuclear plants and has relied on renewables and natural gas from Russia.

In the United States, the danger is that natural gas may be pushed aside prematurely in favor of renewables, leaving the electric grid destabilized and vulnerable to severe weather. The grid is less stable today than it was 20 years ago, according to experts I speak to regularly. Environmental mandates are taking a toll, and natural gas is being pushed out before there are stable renewables and utility-scale storage.

A new assessment of natural gas is needed. Its value to the United States to counter Russia now and in the future isn’t in doubt. The United States is the world’s largest natural-gas producer, and liquefied natural gas is needed as a diplomatic tool.

Domestically, though, it needs a defined place in the electricity evolution. It is an option too valuable to be elbowed out by well-meaning but not well-informed arguments.

In electricity production, natural gas is the least polluting of the three fossil fuels. It emits half the carbon dioxide of coal and heavy oil used to make electricity. Also, it doesn’t have the other pollutants which make coal so devastating to the environment. Progress is being made countering methane leaks, a serious problem.

When burned in a combined-cycle plant, favored by utilities for more than just peaking, natural gas reaches an efficiency of around 64 percent. That is a remarkably high rate of fuel to electricity. Coal-fired plants have an efficiency of about 40 percent.

Back in the 1970s, a combination of price controls and regulation served to dry up the amount of natural gas coming to market. The newly formed Department of Energy added to the sense of an end by declaring that gas was “a depleted resource.” The conventional wisdom was that it was too precious for most uses and especially for making electricity.

In 1978, Congress passed the Power Plant and Industrial Fuel Use Act. It was a prohibiting measure and went after what Congress thought were wasteful uses of natural gas such as ornamental flames and pilot lights in gas stoves. And it prohibited the burning of natural gas to make electricity.

Known simply as the “Fuel Use Act,” it was draconian. There was even a debate about whether the Eternal Flame at Arlington National Cemetery would have to be extinguished.

In 1985, deregulation began to increase the natural gas supply and two years later, the Fuel Use Act was repealed.

But the big break, the great game-changer, was fracking -- first used in the late 1980s. It was developed by George Mitchell and his Mitchell Energy company with help from the DOE. Together with horizontal drilling, it would change everything quickly.

Natural gas became cheap and plentiful and the utilities, using turbines developed from aircraft jet engines, began to switch off coal and to question the cost of building nuclear plants. A new dawn had broken.

Now that happy day is in the past and utilities must make the case for gas turbine capacity to back up their alternative energy operations and as an efficient form of energy storage. Also, if hydrogen is to be the fuel of the future, it will need to use the natural-gas infrastructure.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He is also a well-known international energy-sector expert and consultant. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Chris Powell: Lessons of Enfield’s pizza/sex crisis

Is this your preferred topping?

Innocent-looking Thompsonville Village in Enfield, a large town in Hartford County where the biggest employer is the U.S. headquarters of Lego, the Danish toy company.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Republican state legislators around the country are proposing to require public schools to post all curriculum materials on the Internet as an accountability measure, and the other day they got powerful if inadvertent support from Enfield, Conn.’s school system.

Enfield's school administration acknowledged that an eighth-grade class had been given an assignment in which students were instructed to choose pizza toppings as a sort of code to signify the sex acts they preferred. The objective seems to have been to teach the 14-year-olds that sex, like pizza, should be consensual and negotiated.

The Enfield incident, first publicized by a national parents group, was picked up by news outlets far and wide and put the town on the world map for stupidity.

The school administration apologized and attributed the assignment to a mistake of absentmindedness. That is, a different assignment involving pizza choices but without the sexual allusions, also aiming to teach consent and negotiation, was meant to be used. But this account evaded the big questions.

How did the pizza/sex assignment get into the school system in the first place? Exactly where did it come from? Why is the school system receiving such material? Who authorized it?

And why, in a state where most students graduate from high school without mastering basic math and English, is a school system using a Family Health and Human Sexuality class to teach students, even without sexual allusions, what they already know from their own experience with pizza and life generally -- that when ordering for more than oneself, the preferences of others must be considered?

It's all beyond moronic, even if it is the work of people holding degrees in education and drawing at tax expense annual salaries of $100,000 or more.

Responding to the proposals to require all curriculum materials to be posted on the internet, teachers and school administrators around the country insist that they are not hiding anything and that they make curriculum materials available to anyone who asks. But this is evasive.

For having a misplaced faith in schools, few people do ask, and few people might think they need to ask to see any curriculum materials likening pizza toppings to sex acts or imputing to white students guilt for the mistreatment of racial minorities throughout history.

Yet such materials are indeed in use in American schools, precisely because they are not routinely publicized and easily accessible.

Enfield's Board of Education may appoint a committee to look into the pizza-sex assignment and how a recurrence might be prevented. This too is moronic, for the school superintendent already should be able to answer the big questions. It is distressing and revealing that they were not answered at the board meeting when the incident was discussed at length.

The problem here isn't the sexual prudery of parents or other observers. The Internet distributes pornography so widely that Enfield's eighth-graders already may know more about sex than their parents do. No, the problem is the unaccountability of public schools.

Yes, posting on the Internet all curriculum material will facilitate many questions and complaints, and some will be mistaken, arise from prudery, or have bad intent. But that's democracy, which inevitably is less convenient for government than totalitarianism, a lesson schools should teach -- perhaps most of all to their own staff.

But will any legislators in Connecticut propose a curriculum-posting law and thus risk the ire of the teacher and school administrator unions? (Yes, in Connecticut most school administrators, supposedly managers, are unionized too and so not really managers.)

Any such legislation shouldn't stop with curriculums. It also should require the posting of school salaries and teacher evaluations, thereby repealing Connecticut's law exempting teacher performance evaluations from disclosure, the law's only exemption for evaluations of government employees.

Of course the teacher and administrator unions surely would dissuade the governor and General Assembly from enacting that much accountability in public education. But a discussion of accountability legislation at least might establish that the big problem with public education in Connecticut is that it's not really public at all

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

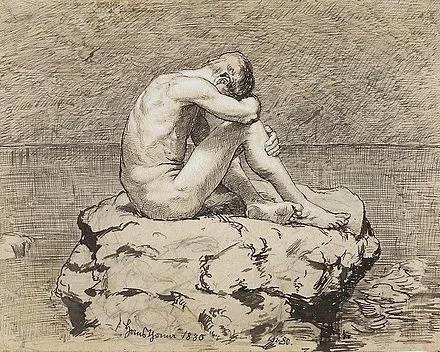

Malaise of elderly grows as pandemic grinds on

“Loneliness,’’ by Hans Thoma, in the National Museum in Warsaw.

“Folks are becoming more anxious and angry and stressed and agitated because this has gone on for so long.’’

— Katherine Cook, chief operating officer of Monadnock Family Services in Keene, N.H., which operates a community mental-health center that serves older adults.

Late one night in January, Jonathan Coffino, 78, turned to his wife as they sat in bed. “I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” he said, glumly.

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system

Coffino was referring to the caution that’s come to define his life during the COVID-19 pandemic. After two years of mostly staying at home and avoiding people, his patience is frayed and his distress is growing.

“There’s a terrible fear that I’ll never get back my normal life,” Coffino told me, describing feelings he tries to keep at bay. “And there’s an awful sense of purposelessness.”

Despite recent signals that COVID’s grip on the country may be easing, many older adults are struggling with persistent malaise, heightened by the spread of the highly contagious omicron variant. Even those who adapted well initially are saying their fortitude is waning or wearing thin.

Like younger people, they’re beset by uncertainty about what the future may bring. But added to that is an especially painful feeling that opportunities that will never come again are being squandered, time is running out, and death is drawing ever nearer.

“I’ve never seen so many people who say they’re hopeless and have nothing to look forward to,” said Henry Kimmel, a clinical psychologist in Sherman Oaks, California, who focuses on older adults.

To be sure, older adults have cause for concern. Throughout the pandemic, they’ve been at much higher risk of becoming seriously ill and dying than other age groups. Even seniors who are fully vaccinated and boosted remain vulnerable: More than two-thirds of vaccinated people hospitalized from June through September with breakthrough infections were 65 or older.

The constant stress of wondering “Am I going to be OK?” and “What’s the future going to look like?” has been hard for Kathleen Tate, 74, a retired nurse in Mount Vernon, Wash. She has late-onset post-polio syndrome and severe osteoarthritis.

“I guess I had the expectation that once we were vaccinated the world would open up again,” said Tate, who lives alone. Although that happened for a while last summer, she largely stopped going out as first the delta and then the omicron variants swept through her area. Now, she said she feels “a quiet desperation.”

This isn’t something that Tate talks about with friends, though she’s hungry for human connection. “I see everybody dealing with extraordinary stresses in their lives, and I don’t want to add to that by complaining or asking to be comforted,” she said.

Tate described a feeling of “flatness” and “being worn out” that saps her motivation. “It’s almost too much effort to reach out to people and try to pull myself out of that place,” she said, admitting she’s watching too much TV and drinking too much alcohol. “It’s just like I want to mellow out and go numb, instead of bucking up and trying to pull myself together.”

Beth Spencer, 73, a recently retired social worker who lives in Ann Arbor, Mich., with her 90-year-old husband, is grappling with similar feelings during this typically challenging Midwestern winter. “The weather here is gray, the sky is gray, and my psyche is gray,” she told me. “I typically am an upbeat person, but I’m struggling to stay motivated.”

“I can’t sort out whether what I’m going through is due to retirement or caregiver stress or covid,” Spencer said, explaining that her husband was recently diagnosed with congestive heart failure. “I find myself asking ‘What’s the meaning of my life right now?’ and I don’t have an answer.”

Bonnie Olsen, a clinical psychologist at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, works extensively with older adults. “At the beginning of the pandemic, many older adults hunkered down and used a lifetime of coping skills to get through this,” she said. “Now, as people face this current surge, it’s as if their well of emotional reserves is being depleted.”

Most at risk are older adults who are isolated and frail, who were vulnerable to depression and anxiety even before the pandemic, or who have suffered serious losses and acute grief. Watch for signs that they are withdrawing from social contact or shutting down emotionally, Olsen said. “When people start to avoid being in touch, then I become more worried,” she said.

Fred Axelrod, 66, of Los Angeles, who’s disabled by ankylosing spondylitis, a serious form of arthritis, lost three close friends during the pandemic: Two died of cancer and one of complications related to diabetes. “You can’t go out and replace friends like that at my age,” he told me.

Now, the only person Axelrod talks to on a regular basis is Kimmel, his therapist. “I don’t do anything. There’s nothing to do, nowhere to go,” he complained. “There’s a lot of times I feel I’m just letting the clock run out. You start thinking, ‘How much more time do I have left?’”

“Older adults are thinking about mortality more than ever and asking, ‘How will we ever get out of this nightmare,’” Kimmel said. “I tell them we all have to stay in the present moment and do our best to keep ourselves occupied and connect with other people.”

Loss has also been a defining feature of the pandemic for Bud Carraway, 79, of Midvale, Utah, whose wife, Virginia, died a year ago. She was a stroke survivor who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heartbeat. The couple, who met in the Marines, had been married 55 years.

“I became depressed. Anxiety kept me awake at night. I couldn’t turn my mind off,” Carraway told me. Those feelings and a sense of being trapped throughout the pandemic “brought me pretty far down,” he said.

Help came from an eight-week grief support program offered online through the University of Utah. One of the assignments was to come up with a list of strategies for cultivating well-being, which Carraway keeps on his front door. Among the items listed: “Walk the mall. Eat with friends. Do some volunteer work. Join a bowling league. Go to a movie. Check out senior centers.”

“I’d circle them as I accomplished each one of them. I knew I had to get up and get out and live again,” Carraway said. “This program, it just made a world of difference.”

Kathie Supiano, an associate professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing who oversees the COVID grief groups, said older adults’ ability to bounce back from setbacks shouldn’t be discounted. “This isn’t their first rodeo. Many people remember polio and the AIDS epidemic. They’ve been through a lot and know how to put things in perspective.”

Alissa Ballot, 66, realized recently she can trust herself to find a way forward. After becoming extremely isolated early in the pandemic, Ballot moved last November from Chicago to New York City. There, she found a community of new friends online at Central Synagogue in Manhattan and her loneliness evaporated as she began attending events in person.

With Omicron’s rise in December, Ballot briefly became fearful that she’d end up alone again. But, this time, something clicked as she pondered some of her rabbi’s spiritual teachings.

“I felt paused on a precipice looking into the unknown and suddenly I thought, ‘So, we don’t know what’s going to happen next, stop worrying.’ And I relaxed. Now I’m like, this is a blip, and I’ll get through it.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

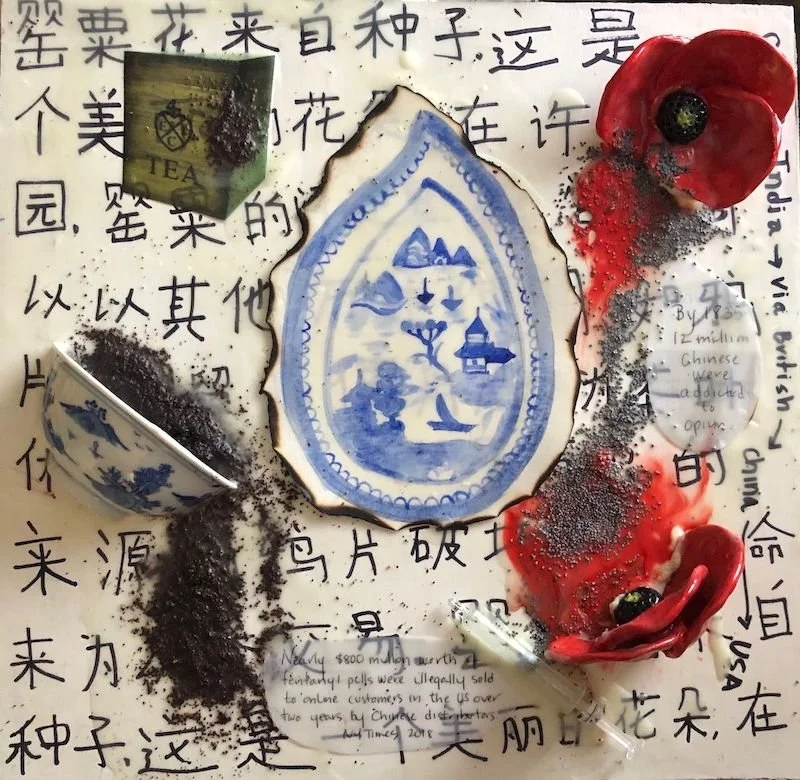

Beauty from New England’s drugged-up China Trade

“China Trade: Opium through the Ages” (encaustic, ceramic made and found objects, tea leaves, poppy seeds on panel), by Cambridge,Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

New England’s “China Trade,’’ in the late 18th Century and the first half of the 19th, created great wealth for some in the region, mostly in and around its ports. Some of the trade involved selling opium to the Chinese. Much of that wealth was invested in what became very lucrative industries, such as textile, shoe and machinery manufacturing and railroads.

In her Web site, Ms. Abbott describes herself thusly:

“Katrina Abbott came to art later in life after her twins were born. Previous to this, she spent 25 years in education, including outdoor education, ocean education at sea and urban public school reform. With a BA in Environmental Biology and a Masters in Botany (studying seaweed!), she reflects her interest in and concern for the natural world in her art. She represents the nature in print, paint, wax ( encaustic) and mosaic. She is a member of the Cambridge Art Association and New England Wax and lives in Cambridge with her husband, their 20 year old boy/girl twins and small brown rabbit named Jarvis.’’

Derby House, in Salem, Mass. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary War merchants in Salem. He was owner of the Grand Turk, said to be the first New England vessel to be used to trade directly with China. There were many mansions built by merchants in the China Trade, some of which was a drug trade.

—Photo by Daderot

And go away February

In March: A "sugar shack" where maple sap is boiling.

Maple-sap collecting.

Dear March—Come in—

How glad I am—

I hoped for you before—

Put down your Hat—

You must have walked—

How out of Breath you are—

Dear March, how are you, and the Rest—

Did you leave Nature well—

Oh March, Come right upstairs with me—

I have so much to tell—

I got your Letter, and the Birds—

The Maples never knew that you were coming—

I declare - how Red their Faces grew—

But March, forgive me—

And all those Hills you left for me to Hue—

There was no Purple suitable—

You took it all with you—

Who knocks? That April—

Lock the Door—

I will not be pursued—

He stayed away a Year to call

When I am occupied—

But trifles look so trivial

As soon as you have come

That blame is just as dear as Praise

And Praise as mere as Blame—

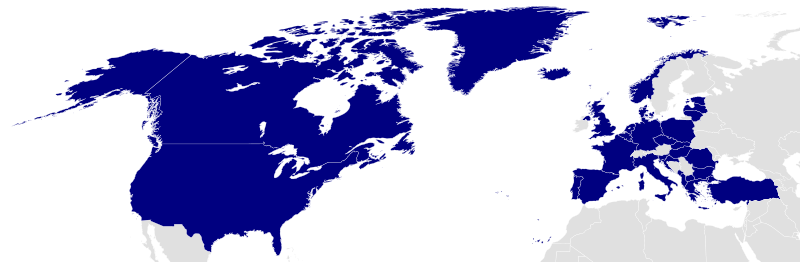

—Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), a lifelong resident of Amherst, Mass.

Don Pesci: May we be worthy of the brave Ukrainians

Albert Camus

VERNON, Conn.

In March, 1957, the French novelist and philosopher Albert Camus (1913-1960) published an essay, at great cost to himself, titled “{Janos} Kadar Had His Day Of Fear.” His epitaph on the Soviet-suppressed Hungarian Revolution, in the fall of 1956, may serve as well as an epitaph on the Ukraine’s democratic revolution, which Russian dictator Vladimir Putin is now trying to destroy. Kadar (1912-1989) was the Communist boss of Hungary, reporting to his Soviet bosses.

The Hungarian Revolution was suppressed at the order of the Kremlin, run by its then boss, Nikita Khrushchev, after Stalin had installed in Hungary a Communist dictatorship after World War II. Camus regarded the takeover of Hungary by totalitarian Stalinists as a counter-revolution.

His essay was costly to Camus for a number of reasons. It was an epistle of liberty and a resolute, unambiguous disparagement of totalitarianism.

The essay began on a defiant note: “The Hungarian Minister of State Marosan, whose name sounds like a program, declared a few days ago that there would be no further counter-revolution in Hungary. For once, one of Kadar's Ministers has told the truth. How could there be a counter-revolution since it has already seized power? There can be no other revolution in Hungary.”

And the second paragraph likely was considered in France by what we might call its philosophical establishment as an awakening slap in the face: “I am not one of those who long for the Hungarian people to take up arms again in an uprising doomed to be crushed under the eyes of an international society that will spare neither applause nor virtuous tears before returning to their slippers like football enthusiasts on Saturday evening after a big game. There are already too many dead in the stadium, and we can be generous only with our own blood. Hungarian blood has proved to be so valuable to Europe and to freedom that we must try to spare every drop of it.”

And then France’s apostle of liberty let loose the following thunderbolt: “But I am not one to think there can be even a resigned or provisional compromise with a reign of terror that has as much right to be called socialist as the executioners of the Inquisition had to be called Christians. And, on this anniversary of liberty, I hope with all my strength that the mute resistance of the Hungarian people will continue, grow stronger, and, echoed by all the voices we can give it, get unanimous international opinion to boycott its oppressors. And if that opinion is too flabby or selfish to do justice to a martyred people, if our voices also are too weak, I hope that the Hungarian resistance will continue until the counter-revolutionary state collapses everywhere in the East under the weight of its lies and its contradictions.”

Camus himself was both an atheist and a socialist fully prepared to take to the ramparts, in fine French fashion: “For it [the Stalinist false front] is indeed a counter-revolutionary state. What else can we call a regime that forces the father to inform on his son, the son to demand the supreme punishment for his father, the wife to bear witness against her husband —that has raised denunciation to the level of a virtue? Foreign tanks, police, twenty-year-old girls hanged, committees of workers decapitated and gagged, scaffolds, writers deported and imprisoned, the lying press, camps, censorship, judges arrested, criminals legislating, and the scaffold again—is this socialism, the great celebration of liberty and justice?”

Here at last was a man who knew how to draw proper distinctions. The essay was bound to tread on tender toes.

In Hungary, a Joshua horn had been sounded, and walls had begun to tumble: “Thus, with the first shout of insurrection in free Budapest, learned and shortsighted philosophies, miles of false reasonings and deceptively beautiful doctrines were scattered like dust. And the truth, the naked truth, so long outraged, burst upon the eyes of the world.

“Contemptuous teachers, unaware that they were thereby insulting the working classes, had assured us that the masses could readily get along without liberty if only they were given bread. And the masses themselves suddenly replied that they didn't have bread but that, even if they did, they would still like something else. For it was not a learned professor but a Budapest blacksmith who wrote: ‘I want to be considered an adult eager to think and capable of thought. I want to be able to express my thoughts without having anything to fear and I want, also, to be listened to.’"

It was an essay too far for many stern socialists in France, some of whom were prepared to avert their eyes so long as the Soviet experiment in Russia moved forward unimpeded.

Camus stood in the way of totalitarian progress. He was of the party of liberty and just revolt. As such, he ended his essay: “Our faith is that throughout the world, beside the impulse toward coercion and death that is darkening history, there is a growing impulse toward persuasion and life, a vast emancipatory movement called culture that is made up both of free creation and of free work.

“Our daily task, our long vocation is to add to that culture by our labors and not to subtract, even temporarily, anything from it. But our proudest duty is to defend personally to the very end, against the impulse toward coercion and death, the freedom of that culture—in other words, the freedom of work and of creation.

“The Hungarian workers and intellectuals, beside whom we stand today with so much impotent grief, realized that and made us realize it. This is why, if their suffering is ours, their hope belongs to us too. Despite their destitution, their exile, their chains, it took them but a single day to transmit to us the royal legacy of liberty. May we be worthy of it!”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

‘A spoon and a rolling pin’

“Aunt Fanny’s headstone in the roadside graveyard is moss-stained … but her reputation as queen of the kitchen still lingers in the village of Franconia, {N.H.} for she was one of those natural cooks who are ‘born with a mixing spoon in one hand and a rolling pin in the other.’ New England has produced many. They invented baked Indian pudding and apple pandowdy. They established the boiled dinner as a Thursday institution, and Boston baked beans and brown bread as the typical Saturday night supper.’’

-- Ellen Shannon Bowles and Dorothy S. Towle, in Secrets of New England Cooking (1947)

State-owned Cannon Mountain, a large and old (founded in the ‘30s) ski area, rising over Franconia village in 2007. The building was the home of Dow Academy, founded in 1884. It was the town's high school until 1958, after which its building, a Georgian Revival wood-frame building built in 1903, became a centerpiece of the the small and experimental Franconia College (RIP) campus. The building was converted into condominium residences in 1983; it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

Treasure trove of life.

“Messages From the Marsh” (video still), by Amy Kaczur, in her show at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 26.

Her Web site says:

“Kaczur’s work is grounded in environmental concerns, community and language. Her latest projects are fueled by a sense of urgency related to water issues, specifically coastal flood zones and rising sea levels. She grew up outside Cleveland, with family ties working in farming, food industry, mills, and coal mines in rural southern Ohio to the edges of Appalachia. Those roots impacted her experience of landscape and environmental issues such as pollution and climate change, and the multilayered struggles between land use and conservation. Along with examining these issues in her art practice, she works at Massachusetts Institute of Technology as the group administrator for two research labs focused on air and water pollution, climate change, and clean energy development and storage. She continuously develops her art practice, supported by relentless research, discovery by experiment, and the pleasure of inquisitive searching.’’

‘Chill & Dream’ in a sonic sanctuary on the Cape

The Pilgrim Monument in the gloaming of Provincetown.

The radio show Chill & Dream returns to the airwaves on WOMR, in Provincetown, Mass. (92.1) and on its sister signal, WFMR, in Orleans, Mass., (91.3) and streaming worldwide on womr.org on Saturday, Feb. 26 at 9 a.m. WOMR is celebrating 40 years on the air. Where were you in 1982? Need an escape in 2022? Chill & Dream is, says creator and DJ "Braintree Jim," your sonic sanctuary, exploring old and new dimensions of sight and sound. Exclusively on WOMR.

In 1940, a beachfront art class in Provincetown, long an internationally known art center.

The Jonathan Young Windmill, a restored, working 18th-Century windmill next to Town Cove in Orleans.

— Photo by ToddC4176

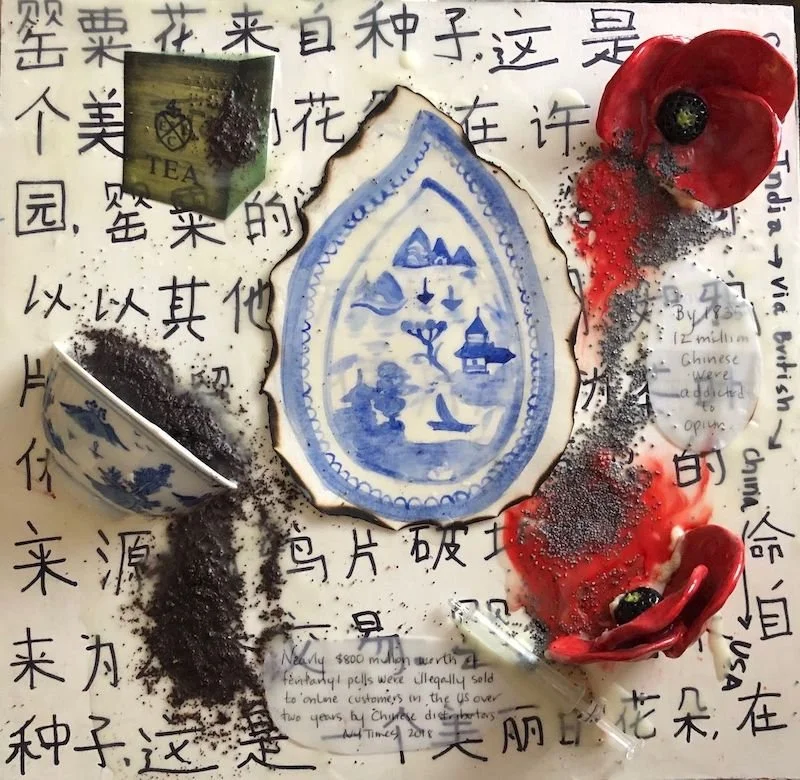

David Warsh: Is Putin responding to U.S. ‘hyper use’ of force and overreach?

Blue indicates member states of NATO.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

With President Biden confidently forecasting a Russian “war of choice” against Ukraine –“I’m convinced he’s made the decision,” he said Feb. 18, – there is not much point in writing about it until war happens, or fails to materialize. Except to say this:

I spent some time last week leafing through books I read long ago, about an earlier “war of choice,” this one thoroughly catastrophic, as it turned – two by Robert Draper, of The New York Times, Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush, and To Start a War: How the Bush Administration took America into Iraq; one by Peter Baker, also of The Times, Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House; another by Rajiv Chandrasekaran, of The Washington Post, Imperial Lives in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone; and a fifth, by Michael MacDonald, of Williams College, Overreach: Delusions of Regime Change in Iraq.

My interest was piqued by a dispatch from New York Times Moscow bureau chief Anton Troianovski. Is NATO dealing with a crafty strategist, he asked, or a reckless paranoid? “At this moment of crescendo for the Ukraine crisis, it all comes down to what kind of leader President Vladimir V. Putin is.” He continued,

In Moscow, many analysts remain convinced that the Russian president is essentially rational, and that the risks of invading Ukraine would be so great that his huge troop buildup makes sense only as a very convincing bluff. But some also leave the door open to the idea that he has fundamentally changed amid the pandemic, a shift that may have left him more paranoid, more aggrieved and more reckless.

It seemed to me that Troianovski, and, by extension, President Biden, had neglected a third interpretation. When Putin gave a famous speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007, criticizing the U.S. for “almost un-contained hyper use of force in international relations,” he reminded listeners in his audience mainly of the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which were then underway, but his subtext was NATO expansion into Eastern Europe and Eurasia after 1993.

Perhaps, I thought, the way to think of Putin is as an accomplished rhetorician, creating a grand show-of-force, illustrated by satellite photographs and maps, with which to quietly bargain with various Ukrainian factions, while seeking to persuade other audiences that for three decades the behavior of the Unites States has been the neglected element, or, as the saying goes, “ the elephant in the room.” Perhaps the long table at whose far end Putin was photographed speaking with French President Emmanuel Macron was more symbolic of the distance that the Russian president feels from NATO negotiators than emblematic of his fear of COVID contagion.

Meanwhile, The Times last week published a story about a secretive U.S. missile base in Poland a hundred miles from the Russian border – a presence that seemed to give the lie to verbal assurances given long ago in negotiations over the reunification of Germany that NATO would expand not one inch to the East.

What if Joe Biden’s convictions about Putin’s intentions turn out to be no better than were those of George W. Bush about Saddam Hussein? When Russian forces finally attack Kyiv – or gradually return to their bases – we’ll know who was right and who was wrong. I’ll stop writing about it when they decide.

While we are hanging on the breathless daily news reports, though, Putin has managed to remind more than a few persons around the world of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, this time played out in in reverse. Was it really Pax Americana? Or more of a three-decade toot?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Now it’s cattle cars at 35,000 feet

Northeast Airlines DC-6B at Logan International Airport, Boston, in 1966. The Boston-based airline started up in 1931 as Boston-Maine Airways and lasted until it was merged into Delta Air Lines, in 1972.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I have to fly soon to Florida to give a talk on “working waterfronts” and am dreading it. It’s not because I fear getting COVID inside a plane, or, more likely, while waiting in a long line at airports.

No, the problem is too many angry, frustrated and non-civic-minded passengers, refusing, for example to wear masks in such crowded places. And a few get violent about it.

But then, except for travelers rich enough to fly first class, air travel is very unpleasant. 9/11 added layers of time-consuming security, including some useless “security theater,” and C0VID-19 was the coup de grace.

But the foundation of the mess was, I suppose, benign. Airline deregulation back in the ’70s led to lower fares for most airlines’ coach seats and thus far more customers. (The most famous low fares before then were offered by the East Coast “shuttle” service offered by Eastern Airlines. No reservations needed! If one plane was filled, you’d just wait for the next one to be quickly provided. I took the shuttle many times. Passengers could pay on board for their tickets with cash, order a drink and soon after takeoff light a cigarette.)

While cheap fares let millions of people who had never flown before enjoy trips to faraway places that before were out of their reach, they also turned airliners into cattle cars.

How much more pleasant, calmer and more civil it was before deregulation.

I also remember all those long-dead little airlines such as Mohawk and North Central that would take you to little cities in Upstate New York and the Upper Midwest. (North Central seemed to have an affinity for flying its sturdy DC-3’s into thunderstorms over Wisconsin. Very exciting.)

Most little airlines have since mostly been absorbed into a few behemoths.

They, like the big airlines, offered very pleasant service.

I remember as a kid being particularly impressed by Northwest Orient Airlines (what romance in the name!), once huge and now gone, having Pullman railroad car style sleeping quarters for those flying the long, long pre-jet trips to Asia. Alas, our trips to Minnesota were far too short to use them.

Before 9/11 things could be pretty relaxed on big planes. Back in 1982 I was flying back on a KLM 747 (the Dutch national airline) to Boston from Paris, where I had a job interview. I was sitting in business class, which, like the rest of the plane, was remarkably uncrowded (this during the “Reagan Recession of 1981-1982), when the pilot went for a stroll in the plane and on his way back, said to me: “Why don’t you join us (him and co-pilot) up front for a chat?’’ So I spent most of the rest of the trip (about three hours) talking with them and, from time to time, a stewardess, who also brought me a delicious meal and Heineken beer as I learned a little bit about how the huge plane worked.

Another memory: Some decades ago most passengers dressed up a bit to fly. Many men, for example, wore a jacket and tie. There was a certain dignity about it. After all, you were in a public place. Now it’s Slobovia.

Planes, like cars, are safer now, and airlines don’t allow smoking. But airline passengers, like drivers, are worse, and the prospect of flying has become a real downer

Take a deep one

“Breath” (mixed media on paper, wood panel), by Amherst, Mass.-based artist Sue Katz.

Mt. Norwottuck in the Mt. Holyoke Range, on the border between the towns of Amherst and Granby.

— Photo by Andy Anderson