David Warsh: How America can get out of its political mess

Not much “unum’’ lately

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The end of Joe Biden’s difficult first year in office evoked all kinds of comparisons. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens recalled successful presidential partnerships with strong chiefs of staff – Ronald Reagan and Howard Baker, George H.W. Bush and James Baker. Stephens asked, “What’s Tom Daschle up to these days?” Nate Cohn, also in The Times, compared Biden’s legislative strategy to that of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, to Biden’s disadvantage. I asked a friend who has known Biden for forty years.

I don’t think you can pin the things that Bret Stephens doesn’t like about the Biden presidency on the staff…. Is Biden missing someone who could talk him out of bad calls? Could a Tom Daschle serve as a keel for Biden the way Leon Panetta did for Bill Clinton? … Doubtful. Think back on how Biden ran his campaign in 1987 and in 2020: lots of cooks in the kitchen. The only one he really trusted was his sister. He delegated authority to nobody. His campaigns were organizational [smash-ups]. Some people never change. At least his heart is in the right place.

Myself, I thought of the two-year presidency of Gerald Ford. The common denominator is that both Ford and Biden had to deal with long national nightmares.

As president, Ford had it easy. After 25 years as a Michigan congressman from Grand Rapids, Republican minority leader for the last nine of them, he was the first political figure to be appointed vice president, under the terms of the 25th Amendment. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in October 1973, having plead guilty to a felony charge of tax evasion. Ford succeeded him in December. When Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in August, 1974, after an especially damaging White House tape recording was released, Ford was sworn in.

In his inaugural address, Ford stated “[O]ur long national nightmare is over. Our Constitution works; our great republic is a government of laws and not of men.” A month later he pardoned Nixon for any crimes he might have committed as president. Nixon’s acceptance was widely viewed as tantamount to an admission of guilt, and the former president withdrew from public life pretty much altogether. Ford’s two years in office were a stream of politics as usual. Disapproval of the pardon weighed against him; so did the fall of Saigon, in April 1975. He ran for the presidency in 1976, but was defeated by Jimmy Carter, governor of Georgia.

As president, Biden faces almost the opposite situation. First, Trump lost the 2020 election, which he then falsely claimed he had won, Next, he apparently sought to interfere with the vote of the Electoral College, for which he is now under investigation. He continues to interfere in Republican primaries, and has threatened to mount a second presidential campaign. Meanwhile, much of Biden’s ambitious legislative agenda has bogged down and his popularity has dwindled in public opinion polls.

What chain of events will allow some future president to pronounce a benediction on the Trump nightmare? My hunch is that a relatively moderate Republican with no previous ties to Trump can be elected, possibly in 2024; if not, in 2028. That is easier said than done. The problem is getting by the Republican convention. It all depends in large measure on the results of the mid-term elections; on the Republican primaries in 2024; and on Biden’s standing at the end of his term, when he will be 82 years old. .

Republican contenders are already edging away from Trump, Gov. Glenn Youngkin, in Virginia; Gov. Ron DeSantis, in Florida. It is not necessary to disavow Trump’s political platform, if anyone besides Joe Biden remembers what it was – less supply-chain globalization; more domestic infrastructure investment; immigration reform (whatever that is!); recalibration of foreign relations, China and Russia in particular. All these positions are capable of commanding support among independent voters

It is Trump himself whose character must be thoroughly rejected. That will happen by degrees. There will be no pardon this time. The next president, whoever it is, will continue to leave matters up to the courts. And, sooner or later, the lingering nightmare will end.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Meet the Putin-run CSTO; The Monitor's Fred Weir explains Russia well

Emblem of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I started writing about Russia in July, 2002, with “The Thing’s a Mess,” a glimpse of a story from the kleptomaniacal decade that followed the collapse of the USSR: how a prominent Harvard economist, his wife and two sidekicks, working in Russia on behalf of the U.S. State Department, covered by high-level friends in the Clinton administration, had been caught seeking to cut to the head of the queue to enter the country’s new mutual- fund business with a firm of their own.

This column followed the saga through the U.S. invasion of Iraq; Vladimir Putin’s objections; his brief 2008 war in former-Soviet Georgia to caution against further NATO expansion; Ukraine’s Maidan protest of 2014 and its aftermath; and the 2016 election of Donald Trump. Its little book, Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years, appeared in 2018.

I still scan four daily newspapers to see what government sources are saying about Russia. I look regularly at Johnson’s Russia List, a Web-based compendium with a good eye for non-standard views. But mostly I form my views from dispatches of Fred Weir, Moscow correspondent for the Boston-based Christian Science Monitor. They are thoughtful, well-informed, and empathetic.

Last week I read three Weir articles to which I am entitled for the month (you can do the same). Why Russia’s troop surge near Ukraine may really be a message for the West made clear that the aim of large troop deployments – for the second time in a year – was to concentrate minds on Russian demands in Kyiv and the West. Russia want guarantees that Ukraine and other former Soviet states won’t join NATO as a basis for regional stability.

How the Kazakhstan crisis reveals a bigger post-Soviet problem explains the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the six-member post-Soviet, Russian-led military alliance that intervened briefly in Kazakhstan to restore order and preserve the current poo-Moscow government. Weir wrote, “The swift and efficient injection of 2,600 troops [mostly Russian paratroopers, but contingents from Armenia, Belarus, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan as well] demonstrated an unprecedented level of elite solidarity among emerging post-Soviet states, which are often depicted as allergic to Russian leadership.”

What’s in a name? For Russia’s “Putin Generation,” not as much as you’d think contrasted the experiences of Russians born in the 21st Century with those of those of their grandparents and parents. Russians born after World War II lived lives of enforced conformity and struggled to satisfy basic consumer needs, Weir writes, before the disintegration of Soviet economic life in the ‘80’s gave way to the desperate 90’s, when people reinvented themselves while struggling to survive.

Instead, this [Putin] generation, at least among those young people that the Monitor interviewed, seems to have a sense of optimism about life and a desire to reach beyond simple material security and do something to improve the world around them. That’s something relatively new in Russia.

Despite his ubiquity in their lives, Mr. Putin is not a symbol or icon to his namesake generation, many experts say, but merely a flashy pop-sociology way to demarcate them without taking into account social class, education, gender, and other critical markers.

When I was finished reading my three stories, I subscribed to The Monitor and read a fourth: Russian human rights group under threat: What soured the Kremlin? It was written before Russia’s Supreme Court shut down Memorial, a human-rights organization formed in the buoyant days of perestroika to document Soviet-era abuse, for having violated the country’s intricate “foreign agent” laws.

Weir wrote, “[M]ost experts see [the decision] as part of an accelerating campaign to close down any space for independent political action or criticism amid deepening antagonism with the West, a stagnating economy, and uncertainties about the continuing stability of Mr. Putin’s regime.”

In other words, there is still plenty of room for improvement in Russian civil society. I doubt, however, there will be war in Ukraine. Putin has made his point more forcefully than ever about the cavalier disrespect that America has shown since 1992. My sense is that he has been doing a pretty good job of putting his country back on its feet, after a surpassingly difficult century. I don’t have that feeling about Xi Jinping and China. But the situation that concerns me most is that of my own country. Bring on those mid-term elections! There is a great deal of rebuilding to begin.

xxx

Here are complementary links to a handful of especially interesting sessions at the American Economic Association meetings on Zoom earlier this month. Eight of the discussions deal with important meat-and-potatoes issues, while the ninth link connects to the hour-long lecture on preference formation, by Nathan Nunn, of Harvard University, that I found so interesting and mentioned last week.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

The First Church of Christ, Scientist in Boston, with the mother church and administrative headquarters of the denomination

David Warsh: On why 'not every couple should have a pre-nup'

“The Marriage Contract,’’ by Flemish artist Jan Josef Horemans the Younger, circa 1768

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The annual meetings of the American Economic Association convention unfolded over the weekend, on Zoom. In Boston, where AEA members had hoped to meet in person, it snowed. After I shoveled (and read the news from Kazakhstan), I went through the motions, watching half a dozen sessions over two days, all of them interesting, none of them possessing the elusive quality of newsworthiness, at least where my column Economic Principals is concerned, given the rest of the work at hand.

So I turned instead to two more deliverable items of interest: the Kenneth J. Arrow Lecture at Columbia University, which David Kreps, of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, delivered in Manhattan last month; and an intriguing new paper by William A. Barnett, of the University of Kansas, editor of Macroeconomic Dynamics and first president of the Society for Economic Measurement.

. xxx

Kreps, described by Columbia’s José Scheinkman as “one of the most accomplished theorists of our generation” (“and our generation wasn’t bad”), spoke under the title “Not Every Couple Should Have a Pre-Nup: How the Context of Exchange and Experience Affect Personal Preferences, and Why This Matters Both to Economic Theory and to Practical Human Resource Management.” The reference is to a long ago BusinessWeek column by the late Gary Becker, of the University of Chicago.

If a contract were required before a couple could legally marry, Becker argued, no bad vibes or stigma would attach to divorce. Not so fast, Kreps countered. There was abundant reason to suspect that preferences are not fixed; that such contracts might interfere with their evolution over the course of a marriage. He proceeded to carefully sort through the implications, in the manner he learned as a close reader of Arrow.

Since the World War II, mainstream economics had become “mathematical,” Kreps said. Everyone understood what he meant: formal models had become the standard means of professional discourse. Developments then came in two broad waves. The first wave, between 1945 and 1970, developed choice theory, price theory and general-equilibrium theory, he said.

The second wave, beginning in 1970 and not over yet, consisted of information economics: “getting serious about the formation of beliefs, especially beliefs about the actions of other economic agents (and how they will react to your own actions).”

“It is well past time for the third wave,” he continued, “Getting serious about preference-determination and preference-evolution.” He connected the movement to concerns that Arrow had expressed as long as fifty years ago. He cited a couple of present-day books as serious curtain-raising work – Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being, by George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton; and The Moral Economy: Why Good Incentives Are No Substitute for Good Citizens, by Samuel Bowles. And he elaborated his own views, “as a commentator, not an originator” – of the extensive careful modeling and testing that would be necessary to establish preference formation as a contribution to serious economics.

On “shaky grounds,” Kreps concluded, “I contend that taking more seriously how preferences are affected by context and experience within context, will— on net — be good for our discipline.” Joseph Stiglitz, of Columbia University, contributed a lively discussion.

All the more reason then, to tune in, when you can, to the Distinguished Lecture that Nathan Nunn, of Harvard University, delivered to the AEA meetings on Friday. A recording of “On the Dynamics of Human Behavior: The Past, Present, and Future of Culture, Conflict, and Cooperation” presumably will be available for free viewing on the AEA Web site in a day or two. If you like this sort of thing, it is definitely worth the wait.

. xxx

Barnett is less well-known in the profession than is Kreps, but he is an unusually interesting gadfly, a talented outsider with a knack for connecting with talented insiders over the course of a long career. Trained as a rocket scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he spent most of the 1960s at Rocketdyne in suburban Los Angeles before leaving in 1969 for Carnegie Mellon University, and a PhD in statistics.

After seven years in the Special Studies Section of the Federal Reserve Board, a unit since abolished, Barnett left with the conviction that instead of depending on classical accounting procedures, the central bank should be using modern methods devised in the 1920s by the French economist François Divisia. a founder of the Econometric Society, and not well-understood by Anglophone economists until 1973. Erwin Diewert, of the University of British Columbia, suggested employing a class of index numbers. known as “superlative” indices, as a suitable alternative to the Fed’s accounting aggregates. Barnett continued to advocate an approach known as the Törnqvist-Theil Divisia index. (Elaboration added)

In 2012, MIT Press published Barnett’s Getting It Wrong: How Faulty Monetary Statistics Undermine the Fed, the Financial System, and the Economy. He has been lobbying for the change (the “Barnett Critique”) ever since, first at the University of Texas, then Washington University, and, since 2002, at the University of Kansas. He was a founder of the Center for Financial Stability, a Manhattan-based think tank, and is director of one of its programs, as well.

Last week a paper by Barnett and four others circulated widely on the Internet. “Shilnikov chaos, low interest rates, and New Keynesian macroeconomics,” from the latest Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, was sufficiently interesting that Barnett arranged to have it published open access online. “[I]t might be very important,” he wrote.

I wrote back to say that Shilnikov chaos attractors were well above my paygrade. Barnett replied in plain English:

We have another paper about how to fix the problem. It isn’t difficult to fix. The source of the problem is that attaching a myopic interest rate feedback equation (Taylor rule) to the economy’s dynamics without a long run terminal condition alters the dynamics of the system to produce downward drift in interest rates. Our results produce an amazing match to the 30-year downward drift of interest rates into the current liquidity trap. The solution is for the Fed also to have a second policy instrument to impose a long run anchor (no surprise to the ECB). Since the short run interest rate is useless as a policy instrument at the zero lower bound, central banks are now experimenting with other instruments. It would have been better if they had done that before interest rates had drifted down into the lower bound.

That wasn’t hard to understand at all, at least intuitively. Ever since William Harvey in 1628 demonstrated the heart’s circulation of the blood, economists, from John Law and François Quesnay to the designers of today’s flow of funds accounts, have sought to understand the mysteries of the economy’s circular flow of money, products and services. Though never a boatswain, I have had enough experience anchoring boats in sometimes powerful currents to recognize the virtues of having more than one anchor out, sometimes in a completely different direction.

The last fifty years have been a wild ride for the Fed’s managers of the world’s money. Don’t expect to enter a quiet harbor any time soon.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Nobel economics prize committee needs to look at the lessons of the 2008 crisis

Lehman Brothers headquarters in New York before the firm’s bankruptcy in September 2008 sent the world into the worst financial panic since the Great Depression.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a substantial responsibility the government of Sweden licensed when, in the 1960s, it gave its blessing to the creation of a prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel, to be administered by Nobel Foundation and awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. That bold action wasn’t easy, but it was as easy as it would get.

The Cold War smoldered ominously between two very different systems, “capitalist” and “communist.” In the West, the prestige of the Keynesian revolution was at its height, compared by some historians of science to the Darwinian, Einsteinian, Freudian and quantum revolutions. And the Science Academy possessed seventy-five years of experience as administrators of the physics and chemistry awards that were among the five prizes mandated by Nobel’s handwritten will.

Since 1969, when the first economics prize was awarded, the committee that oversees it has done pretty well, at least in the judgment of those who have followed the program closely. The Nobel system has imposed a narrative order on various developments since the 1940s in an otherwise fractious profession, often by recognizing its close neighbors. Goodness knows where we in the audience would be without it – still reading Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers, perhaps, first published in 1953, as though nothing since had happened.

Now, however, the Nobel Prize in economic sciences is facing a crucial test. The authorities need to give a prize to clarify understanding inside and outside the profession of the events of 2008, when emergency lending and institutional restructuring by the world’s central banks halted a severe financial panic. What might have turned into a second Great Depression was thus averted. Governments’ responsibilities as lenders of last resort were the heart of the issue over which Keynesians and Monetarists jousted for seventy-five years after 1932.

Either the Swedes have something to say about what happened in 2008, not necessarily this year, but soon, or else they don’t. Their discussions are well underway. The credibility of the prize is at stake.

The Nobel committees that administered the prizes in physics and chemistry faced similar problems in their early years. When the first prizes were awarded, in 1901, well-established discoveries dating from the 1890s made the decisions relatively noncontroversial – the discovery of x-rays, radioactivity, the presence of inert gases in the atmosphere, and the electron. Foreign scientists were invited to make nominations; Swedish experts on the small committees, several of them quite cosmopolitan, made the decisions. The members of the much larger academy customarily accepted their recommendations.

But a pair of scientific revolutions, in quantum mechanics and relativity theory, soon generated “problem candidacies” that took several years to resolve. Max Planck, first seriously considered in 1908 for his discovery of energy quanta, was final recognized in 1918. Albert Einstein, first nominated in 1910 for his special relativity theory, was recognized only in 1921, and then for his less important work on the photo-voltaic effect.

It is thanks to Elisabeth Crawford, the Swedish historian of science who first won permission to study the Nobel archive, that we know something about behind-the-scenes campaigns among rival scientists that underlay these decisions. Overlooked altogether may have been the significance of the work of Ludwig Boltzmann, who committed suicide in 1906.

The economics committee has what it needs to make a decision about 2008. The Swedish banking system suffered a similar crisis in the early Nineties and dealt with it in a similar way. Fifteen years later, Swedish economists paid close attention to what was happening in New York and Washington,

In 2017, in cooperation with the Swedish House of Finance, the committee organized a symposium on money and banking, at which the leading interpreters of the 2008 crisis contributed discussions. (You can see here for yourself some of the sessions from that two-and-half day affair, but good luck making sense of the program. That’s what the committee exists to do – after the fact.)

A previous symposium, in 1999, considered economics of transition from planned economies, and wisely steered off. No such inquiry was required to arrive the sequence of prizes that interpreted the disinflation that followed the Volcker stabilization – Robert Lucas (1995), Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott (2004), Thomas Sargent and Christopher Sims (2012) – a process that unfolded more slowly and less certainly than the intervention of 2008.

The money and banking prize should be understood as fundamentally a prize for theory. For all the talk in the last few years about the rise of applied economics, the Nobel narrative, at least as I understand it, has emphasized mainly surprises of various sorts that have emerged from fresh applications of theory, in keeping with Einstein’s dictum that it is the theory that determines what we can observe.

Some of these applications may have reached dead ends, leading to new twists and turns. The advent of cheap, powerful computer and designer software in the Nineties handed economists a power new tool, and two recent prizes have reflected the uses to which the tools have been put – devising randomized controlled tests of economic policies, and drawing conclusion from carefully-studied “natural experiments.” But otherwise “the age of the applied economist” may be mainly a marketing campaign for a generation of young economists eager to advance their careers. It won’t be an age in economic science until the Nobel timeline says it is.

As a journalist, I’ve covered the field for forty years. My impression is that many exciting developments have occurred in that time that have not yet been recognized, some of them quite surprising, many of them reassuring. As the Nobel view of the evolution of the field is revealed in successive Octobers, the effect may be to buttress confidence in the field and diminish skepticism about its roots – or not. As for natural experiments, it is hard to beat the events of 2008. The Swedes have many nominations. What they must do now is decide.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

David Warsh: A smelly red herring in Trump-Russia saga

Herrings "kippered" by smoking, salting and artificially dyeing until made reddish-brown, i.e., a "red herring". Before refrigeration kipper was known for being strongly pungent. In 1807, William Cobbett wrote how he used a kipper to lay a false trail, while training hunting dogs—a story that was probably the origin of the idiom.

Grand Kremlin Palace, in Moscow, commissioned 1838 by Czar Nicholas I, constructed 1839–1849, and today the official residence of the president of Russia

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A red herring, says Wikipedia, is something that misleads or distracts from a relevant and important question. A colorful 19th Century English journalist, William Cobbett, is said to have popularized he term, telling a story of having used strong-smelling smoked fish to divert and distract hounds from chasing a rabbit.

The important questions long have had to do to do with the extent of Trump’s relations with powerful figures in Russian before his election as president; and with whether the FBI did a competent job of investigating those charges.

The herring in this case is the Durham investigation of various forms of 2016 campaign mischief, including (but not limited to) the so-called “Steele Dossier’’. The inquiry into Trump’s Russia connections was furthered (but not started) by persons associated with Hillary Clinton’s campaign. {Editor’s note: The political investigations of Trump’s ties with Russia started with anti-Trump Republicans.}

Trump’s claims that his 2020 defeat were the result of voter fraud have been authoritatively rejected. What, then, of his earlier fabrication? It has to so with the beginnings of his administration, not its end. The proposition that Clinton campaign dirty tricks triggered a tainted FBI investigation and hamstrung what otherwise might have been promising presidential beginning has been promoted for five years by Trump himself. The Mueller Report on Russian interference in the 2016 election was a “hoax,” a “witch-hunt’’ and a “deep-state conspiracy,” he has claimed.

Today, Trump’s charges are being kept on life-support in the mainstream press by a handful of columnists, most of them connected, one way or another, with the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal. Most prominent among them are Holman Jenkins, Kimberly Strassel and Bret Stephens, now writing for The New York Times.

Durham, a career government prosecutor with a strong record as a special investigator of government misconduct (the Whitey Bulger case, post 9/11 CIA torture) was named by Trump to be U.S. attorney for Connecticut in early 2018. A year later, Atty. Gen. William Barr assigned him to investigate the president’s claims that suspicions about his relations with Russia had been inspired by Democratic Party dirty tricks, fanned by left-wing media, and pursued by a complicit FBI. Last autumn, Barr named Durham a special prosecutor, to ensure that his term wouldn’t end with the Biden administration.

There is no argument that Durham has asked some penetrating questions. The “Steele Dossier,” with its unsubstantiated salacious claims, is now shredded, thanks mostly to the slovenly methods of the man who compiled it, former British intelligence agent Christopher Steele. Durham’s quest to discover the sources of information supplied to the FBI is continuing. The latest news of it was supplied last week, as usual, by Devlin Barrett, of The Washington Post. (Warning: it is an intricate matter.)

What Durham has not begun to demonstrate is that, as a duly-elected president, Donald Trump should have been above suspicion as he came into office. There was his long history of real estate and other business dealings with Russians. There was the appointment of lobbyist Paul Manafort as campaign chairman in June 2016; the secret beginning on July 31 of an FBI investigation of links between Russian officials and various Trump associates, dubbed Crossfire Hurricane; Manafort’s forced resignation in August; the appointment of former Defense Intelligence Agency Director Michael Flynn as National Security adviser and his forced resignation after 22 days; Trump’s demand for “loyalty” from FBI Director James Comey at a private dinner a week after his inauguration, and Comey’s abrupt dismissal four months later (which triggered Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel to the Justice Department): none of this has been shown to do Hillary Clinton’s campaign machinations.

The Steele Dossier did indeed embarrass the media to a limited extent – Mother Jones and Buzzfeed in particular – but it was President Trump’s own behavior, not dirty tricks, that disrupted his first months in office. Those columnists who exaggerate the significance of campaign tricks are good journalists. So why keep rattling on?

In the background is the 30-year obsession of the WSJ editorial page with Bill and Hillary Clinton. WSJ ed page coverage of the story of John Durham’s investigation reminds me of Blood and Ruins, The Last Imperial War 1931-1945 (forthcoming next April in the US), in which Oxford historian Richard Overy argues that World War II really began, not in 1939 or 1941, but with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Keep sniffing around if you like, but what you smell is smoked herring.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

© 2021 DAVID WARSH

David Warsh: Perhaps we're in the Third Reconstruction

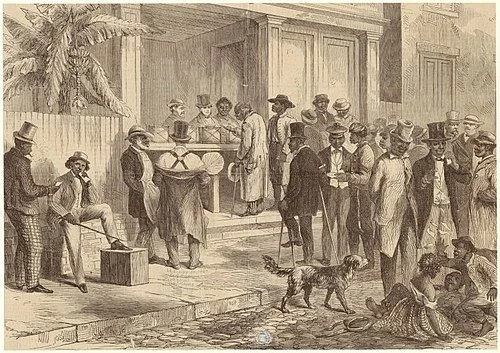

Former slaves voting in New Orleans in 1867. After Reconstruction ended, in 1977, most Black people in much of the South lost the right to vote and didn’t regain it until the 1960s.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“Reconstruction” (1865–1877), as high school students encounter it, is the period of a dozen years following the American Civil War. Emancipation and abolition were carried through; attempts were made to redress the inequities of slavery; and problems were resolved involving the full re-admission to the Union of the 11 states that had seceded.

The latter measures were more successful than the former, but the process had a beginning and an end. After the back-room deals that followed the disputed election of 1876, the political system settled in a new equilibrium.

I’ve become intrigued by the possibility that one reconstruction wasn’t enough. Perhaps the American republic must periodically renegotiate the terms of the agreement that its founders reached in the summer of 1787 – the so-called “miracle in Philadelphia,” in which the Constitution of the United States was agreed upon, with all its striking imperfections.

Is it possible that we are now embroiled in a third such reconstruction?

The drama of Reconstruction is well documented and thoroughly understood. It started with Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, continued with his Second Inaugural address, the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox Courthouse; emerged from the political battles Andrew Johnson’s administration and the two terms of President U.S. Grant; and climaxed with the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution – the “Reconstruction Amendments.” It ended with the disputed election of 1876, when Southern senators supported the election of Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, in exchange for a promise to formally end Reconstruction and Federal occupation he following year.

The shameful truce that followed came to be known as the Jim Crow era. It last 75 years. The subjugation of African-Americans and depredations of the Ku Klux Klan were eclipsed by the maudlin drama of reconciliation among of white veterans – a story brilliantly related in Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, by David Blight, of Yale University. For an up-to-date account, see The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution, by Eric Foner, of Columbia University.

The second reconstruction, if that is what it was, was presaged in 1942 by Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal’s book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy, commissioned by the Carnegie Corporation. The political movement commenced in 1948 with the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces. The civil rights movement lasted from Rosa Parks’s arrest, in 1955, through the March on Washington, in 1963, at which Martin Luther King Jr. made delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, and culminated in the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Repression was far less violent than on the way to the Jim Crow era. There were murders in the civil rights era, but mostly they made newspaper front pages.

And while the second reconstruction entered on race, many other barriers were breached in those rears as well: ethnicity, gender and sexual preference. In Roe v Wade the Supreme Court established a constitutional right to abortion a decade after the invention of the Pill made pregnancy a fundamentally deliberate decision.

How do reconstructions end? In the aftermath of decisive elections, it would seem – in the case of the second reconstruction, with the 1968 election of Richard Nixon, based on a Southern strategy devised originally by Barry Goldwater. Nixon was in many ways the last in a line of liberal presidents who followed Franklin Roosevelt. He had promised to “end the {Vietnam} war” the war and he did. An armistice of sorts – Norman Lear’s All in the Family television sit-com – preceded his Watergate-inspired resignation. Peace lasted until the election of President Barack Obama.

So what can be said about this third reconstruction, if that is what it is? Certainly it is still more diffuse – not just Black Lives Matter, but #MeToo, transgender rights, immigration policy and climate change, all of it aggravated by the election of Donald Trump. This latest reconstruction is often described as a culture war, by those who have never seen an armed conflict. How might this episode end? In the usual way, with a decisive election. Armistice may takes longer to achieve.

For a slightly different view of the history, see Bret Stephens’s Why Wokeness Will Fail. We journalists are free to voice opinions, but we must ultimately leave these questions to political leaders, legal scholars, philosophers, historians and the passage of time. I was heartened, though, at the thought expressed by economic philosopher John Roemer, of Yale University, who knows much more than I do about these matters, when he wrote the other day to say “I think the formulation of the first, second, third…. Reconstructions is incisive. It reminds me of the way we measure the lifetime of a radioactive mineral. We celebrate its half-life, three-quarters life, etc….. but the radioactivity never completely disappears. Racism, like radioactivity, dissipates over time but never vanishes.”

David Warsh is a veteran columnist and an economic historian He’s proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

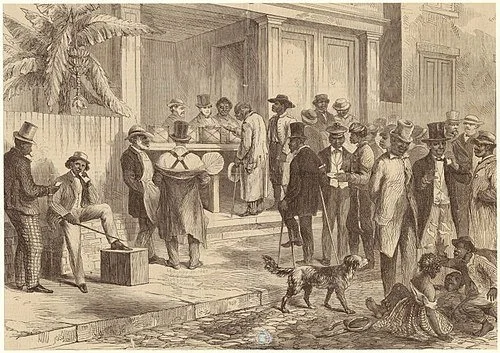

David Warsh: Pinning things down using history

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In Natural Experiments of History, a collection of essays published a decade ago, editors Jared Diamond and James Robinson wrote, “The controlled and replicated laboratory experiment, in which the experimenter directly manipulates variables, is often considered the hallmark of the scientific method” – virtually the only approach employed in physics, chemistry, molecular biology.

Yet in fields considered scientific that are concerned with the past – evolutionary biology, paleontology, historical geology, epidemiology, astrophysics – manipulative experiments are not possible. Other paths to knowledge are therefore required, they explained, methods of “observing, describing, and explaining the real world, and of setting the individual explanations within a larger framework “– of “doing science,” in other words.

Studying “natural experiments” is one useful alternative, they continued – finding systems that are similar in many ways but which differ significantly with respect to factors whose influence can be compared quantitatively, aided by statistical analysis.

Thus this year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences recognizes Joshua Angrist, 61, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; David Card, 64, of the University of California, Berkeley; and Guido Imbens, 58, of Stanford University, “for having shown that natural experiments can answer central questions for society.”

Angrist, burst on the scene in in 1990, when “Lifetime Earnings and the Vietnam Era Draft Lottery: Evidence from Social Security administrative records” appeared in the American Economic Review. The luck of the draw had, for a time, determined who would be drafted during America’s Vietnam War, but in the early 1980s, long after their wartime service was ended, the earnings of white veterans were about 15 percent less than the earnings of comparable nonveterans, Angrist showed.

About the same time, Card had a similar idea, studying the impact on the Miami labor market of the massive Mariel boatlift out of Cuba, but his paper appeared in the less prestigious Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Card then partnered with his colleague, Alan Krueger, to search for more natural experiments in labor markets. Their most important contribution, a careful study of differential responses in nearby eastern Pennsylvania to a minimum-wage increase in New Jersey, appeared as was Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage (Princeton, 1994). Angrist and Imbens, meanwhile, mainly explored methodological questions.

Given the rule that no more than three persons can share a given Nobel prize, and the lesser likelihood that separate prizes might be given in two different years, Krueger’s tragic suicide, in 2019, rendered it possible to cite, in a single award, Card, for empirical work, and Angrist and Imbens, for methodological contributions.

Princeton economist Orley Ashenfelter, who, with his mentor Richard Quandt, also of Princeton, more or less started it all, told National Public Radio’s Planet Money that “It’s a nice thing because the Nobel committee has been fixated on economic theory for so long, and now this is the second prize awarded for how economic analysis is now primarily done. Most economic analysis nowadays is applied and empirical.” [Work on randomized clinical trials was recognized in 2019.]

In 2010 Angrist and Jörn-Staffen Pischke described the movement as “the credibility revolution.” And in the The Age of the Applied Economist: the Transformation of Economics since the 1970s. (Duke, 2017), Matthew Panhans and John Singleton wrote that “[T]he missionary’s Bible today is less Mas-Colell et al and more Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion (Angrist and Pischke, Princeton, 2011)

Maybe so. Still, many of those “larger frameworks” must lie somewhere ahead.

“History,’’ by Frederick Dielman (1896)

That Dale Jorgenson, of Harvard University, would be recognized with a Nobel Prize was an all but foregone conclusion as recently as twenty years ago. Harvard University had hired him away from the University of California at Berkeley in 1969, along Zvi Griliches, from the University of Chicago, and Kenneth Arrow, from Stanford University (the year before). Arrow had received the Clark Medal in 1957, Griliches in 1965; Jorgenson was named in 1971. “[H]e is preeminently a master of the territory between economics and statistics, where both have to be applied in the study of concrete problems.” said the citation. With John Hicks, Arrow received the Nobel Prize the next year.

For the next thirty years, all three men brought imagination to bear on one problem after another. Griliches was named a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association in 1994; he died in 1999. Jorgenson, named a Distinguished Fellow in 2001, began an ambitious new project in 2010 to continuously update measures of output and inputs of capital, labor, energy, materials and services for individual industries. Arrow returned to Stanford in 1979 and died in 2017.

Call Jorgenson’s contributions to growth accounting “normal science” if you like – mopping up, making sure, improving the measures introduced by Simon Kuznets, Ricard Stone, and Angus Deaton. It didn’t seem so at the time. The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on.

xxx

Where are the women in economics, asked Tim Harford, economics columnist of the Financial Times the other day. They are everywhere, still small in numbers, especially at senior level, but their participation is steadily growing. AEA presidents include Alice Rivlin (1986); Anne Krueger (1996); Claudia Goldin (2013); Janet Yellen (2020); Christina Romer (2022), and Susan Athey, president elect (2023). Clark medals have been awarded to Athey (2007), Esther Duflo (2010), Amy Finkelstein (2012), Emi Nakamura (2019), and Melissa Dell (2020).

Not to mention that Yellen, having chaired the Federal Reserve Board for four years, today is secretary of the Treasury; that Fed governor Lael Brainerd is widely considered an eventual chair; that Cecilia Elena Rouse chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers; that Christine Lagarde is president of European Central Bank; and that Kristalina Georgieva is managing director of the International Monetary Fund, for a while longer, at least.

The latest woman to enter these upper ranks is Eva Mörk, a professor of economics at Uppsala University, apparently the first female to join the Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences that recommends the Economics Sciences Prize, the last barrier to fall in an otherwise egalitarian institution. She stepped out from behind the table in Stockholm last week to deliver a strong TED-style talk (at minutes 5:30-18:30 in the recording) about the whys and wherefores of the award, and gave an interesting interview afterwards.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Goldin's marriage manual for the next generation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

For many people, the COVID-19 pandemic has been an eighteen-month interruption. Survive it, and get back to work. For those born after 1979, it may prove to have been a new beginning. Women and men born in the 21st Century may have found themselves beginning their lives together in the midst of yet another historic turning point.

That’s the argument that Claudia Goldin advances in Career and Family: Women’s Century-long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021). As a reader who has been engaged as a practitioner in both career and family for many years, I aver that this is no ordinary book. What does greedy work have to do with it? And why is the work “greedy,” instead of “demanding” or “important?” Good question, but that is getting ahead of the story.

Goldin, a distinguished historian of the role of women in the American economy, begins her account in 1963, when Betty Friedan wrote a book about college-educated women who were frustrated as stay-at-home moms. Their problem, Friedan wrote, “has no name.” The Feminine Mystique caught the beginnings of a second wave of feminism that continues with puissant force today. Meanwhile, Goldin continues, a new “problem with no name” has arisen:

Now, more than ever, couples of all stripes are struggling to balance employment and family, their work lives and home lives. As a nation, we are collectively waking up to the importance of caregiving, to its value, for the present and future generations. We are starting to fully realize its cost in terms of lost income, flattened careers, and trade-offs between couples (heterosexual and same sex), as well as the particularly strenuous demands on single mothers and fathers. These realizations predated the pandemic but have been brought into sharp focus by it.

A University of Chicago-trained economist; the first woman tenured by Harvard’s economics department; author of five important books, including, with her partner, Harvard labor economist Lawrence Katz, The Race between Education and Technology (Harvard Belknap, 2010); recipient of an impressive garland of honors, among them the Nemmers award in economics; a former president of the American Economic Association: Goldin has written a chatty, readable sequel to Friedan, destined itself to become a paperback best-seller – all the more persuasive because it is rooted in the work of hundreds of other labor economists and economic historians over the years. Granted, Goldin is expert in the history of gender only in the United States; other nations will compile stories of their own. .

To begin with, Goldin distinguishes among the experiences of five roughly-defined generations of college-educated American women since the beginning of the twentieth century. Each cohort merits a chapter. The experiences of gay women were especially hard to pin down over the years, given changing norms.

In “Passing the Baton,” Goldin characterizes the first group, women born between 1878-97, as having had to choose between raising families and pursuing careers. Even the briefest biographies of the lives culled from Notable American Women make interesting reading: Jeannette Rankin, Helen Keller, Margaret Sanger, Katharine McCormick, Pearl Buck, Katharine White, Sadie Alexander, Frances Perkins. But most of that first generation of college women never became more prominent than as presidents of the League of Women Voters or the Garden Club. They were mothers and grandmothers the rest of their lives.

In “A Fork in the Road,” her account of the generation born between 1898 and 1923, Goldin dwells on 75-year-old Margaret Reid, whom she frequently passed at the library as a graduate student at Chicago, where Reid had earned a Ph.D. in in economics in 1934. (They never spoke; Goldin, a student of Robert Fogel, was working on slavery then.) Otherwise, this second generation was dominated by a pattern of jobs, then family. The notable of this generation tend to be actresses – Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Rosalind Russell, Barbara Stanwyck – sometimes playing roles modeled on real-world careers, as when Hepburn played a world-roving journalist resembling Dorothy Thompson in Woman of the Year.

In “The Bridge Group,” Goldin discusses the generation born between 1924-1943, who raised families first and then found jobs – or didn’t find jobs. She begins by describing what it was like to read Mary McCarthy’s novel, The Group (in a paper-bag cover), as a 17-year-old commuting from home in East Queens to a summer job in Greenwich Village. It was a glimpse of her parents’ lives – the dark cloud of the Great Depression that hung over w US in the Thirties, the hiring bars and marriage bar that turned college-educated women out of the work-force at the first hint of second income.

“The Crossroads with Betty Friedan” is about the Fifties and the television shows, such as I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, Leave It to Beaver and Father Knows Best that, amid other provocations, led Betty Friedan to famously ask, “Is that all there is?” Between the college graduation class of 1957 and the class of 1961, Goldin finds, in an enormous survey by the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Labor Department, an inflection point. The winds shift, the mood changes. Women in small numbers begin to return to careers after their children are grown: Jeane Kirkpatrick, Erma Bombeck, Phyllis Schafly, Janet Napolitano and Goldin’s own mother, who became a successful elementary school principal. Friedan had been right, looking backwards, Goldin concludes, but wrong about what was about to happen.

In “The Quiet Revolution,” members of the generation born between 1944-1957 set out to pursue careers and then, perhaps, form families. The going is hard but they keep at it. The scene is set with a gag from the Mary Tyler Moore Show in 1972. Mary is leaving her childhood home with her father, on her way to her job as a television news reporter. He mother calls out, “Remember to take your pill, dear.” Father and daughter both reply, “I will.” Father scowls an embarrassed double-take. The show’s theme song concludes, “You’re going to make it after all.” The far-reaching consequences of the advent of dependable birth control for women’s new choices are thoroughly explored. This is, after all, Goldin’s own generation.

“Assisting the Revolution,” about the generation born between1958-78, is introduced by a recitation of the various roles played by Saturday Night Live star Tina Fey – comedian, actor, writer. Group Five had an easier time of it. They were admitted in increasing numbers to professional and graduate schools. They achieved parity with men in colleges and surpassed them in numbers. They threw themselves into careers. “But they had learned from their Group Four older sisters that the path to career must leave room for family, as deferral could lead to no children,” Golden writes. So they married more carefully and earlier, chose softer career paths, or froze their eggs. Life had become more complicated.

In her final chapters – “Mind the Gap,” “The Lawyer and the Pharmacist” and “On Call” – Goldin tackles the knotty problem. The gender earnings gap has persisted over fifty years, despite the enormous changes that have taken place. She explores the many different possible explanations, before concluding that the difference stems from the need in two-career families for flexibility – and the decision, most often by women, to be on-call, ready to leave the office for home. Children get sick, pipes break, school close for vacation, the baby-sitter leaves town.

The good news is that the terms of relationships are negotiable, not between equity-seeking partners, but with their employers as well. The offer of parental leave for fathers is only the most obvious example. Professional firms in many industries are addicted to the charrette – a furious round of last-minute collaborative work or competition to meet a deadline. Such customs can be given a name and reduced. Firms need to make a profit, it is true, but the name of the beast, the eighty-hour week, is “greedy work.”

It is up the members of the sixth group, their spouses and employers, to further work out the terms of this deal. The most intimate discussions in the way ahear will occur within and among families. Then come board rooms, labor negotiations, mass media, social media, and politics. Even in its hardcover edition, Career and Family is a bargain. I am going home to start to assemble another photograph album – grandparents, parents, sibs, girlfriends, wife, children, and grandchildren – this one to be an annotated family album.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

A "Wife Wanted" ad in an 1801 newspaper

"N.B." means "note well".

David Warsh: The exciting lives of former newspapermen

— Photo by Knowtex

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

After the Internet laid waste to old monopolies on printing presses and broadcast towers, new opportunities arose for inhabitants of newsrooms. That much I knew from personal experience. With it in mind, I have been reading Spooked: The Trump Dossier, Black Cube, and the Rise of Private Spies (Harper, 2021), by Barry Meier, a former reporter for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Meier also wrote Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Story of Addiction and Death (Rodale, 2003), the first book to dig in to the story of the Sackler family, before Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty (Doubleday, 2021), by New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe, eclipsed it earlier this year. In other words, Meier knows his way around. So does Lincoln Millstein, proprietor of The Quietside Journal, a hyperlocal Web site covering three small towns on the southwest side of Mt. Desert Island, in Downeast Maine.

Meier’s book is essentially a story about Glenn Simpson, a colorful star investigative reporter for the WSJ who quit in 2009 to establish Fusion GPS, a private investigative firm for hire. It was Fusion GPS that, while working first for Republican candidates in early 2016, then for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, hired former MI6 agent Christopher Steele to investigate Donald Trump’s activities in Russia.

Meier, a careful reporter and vivid writer, doesn’t think much of Simpson, still less of Steele, but I found the book frustrating: there were too many stories about bad behavior in the far-flung private intelligence industry, too loosely stitched together, to make possible a satisfying conclusion about the circumstances in which the Steele dossier surfaced, other than information, proven or not, once assembled and packaged, wants to be free. William Cohan’s NYT review of Spooked was helpful: “[W]e are left, in the end, with a gun that doesn’t really go off.”

Meier did include in his book (and repeat in a NYT op-ed) a telling vignette about Fusion GPS co-founder Peter Fritsch, another former WSJ staffer who in his 15-year career at the paper had served as bureau chief in several cities around the world. At one point, Fritsch phones WSJ reporter John Carreyrou, ostensibly seeking guidance on the reputation of a whistleblower at a medical firm – without revealing that Fusion GPS had begun working for Elizabeth Holmes, of whose blood-testing start-up, Theranos, Carreyrou had begun an investigation.

Fritsch’s further efforts to undermine Carreyrou’s investigation failed. Simpson and Fritch tell their story of the Steele dossier in Crime in Progress (2019, Random House.) I’d like to someday read more personal accounts of their experiences in the private spy trade, I thought, as I put Spooked and Crime in Progress back on the shelf Given the authors’ new occupations, it doesn’t seem likely those accounts will be written.

By then, Meier’s story had got me thinking about Carreyrou himself. His brilliant reporting for the WSJ, and his 2018 best-seller, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (Knopf, 2018, led to Elizabeth Holmes’s trial on criminal charges that began last month in San Jose. Thanks to Twitter, I found, within an hour of its appearance, this interview with Carreyrou, now covering the trial online as an independent journalist.

My head spun at the thought of the leg-push and tradecraft required to practice journalism at these high altitudes. The changes wrought by the advent of the Web and social media have fundamentally expanded the business beyond the days when newspapers and broadcast news were the primary producers of news. In 1972, when I went to work for the WSJ, for example, the entire paper ordinarily contained only four bylines a day.

So I turned with some relief to The Quietside Journal, the Web site where retired Hearst executive Lincoln Millstein covers events in three small towns on Mt. Desert Island, Maine, for some 17,000 weekly readers. In an illuminating story about his enterprise, Millstein told Rick Edmonds, of the Poynter Institute, that he works six days a week, again employing pretty much the same skills he acquired when he covered Middletown, Conn., for The Hartford Courant forty years ago. (Millstein put the Economic Principals column in business in 1984, not long after he arrived as deputy business editor at The Boston Globe).

My case is different. Like many newspaper journalists in the 1980s, I worked four or five days a week at my day job and spent vacations and weekends writing books. I quit the day job in 2002, but kept the column and finished the book. (It was published in 2006 as Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery).

Economic Principals subscribers have kept the office open ever since; I gradually found another book to write; and so it has worked out pretty well. The ratio of time spent is reversed: four days a week for the book, two days for the column, producing, as best I can judge, something worth reading on Sunday morning. Eight paragraphs, sometimes more, occasionally fewer: It’s a living, an opportunity to keep after the story, still, as we used to say, the sport of kings.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Looking at a ‘three-pronged approach’ to global warming

Average surface air temperatures from 2011 to 2020 compared to the 1951-1980 average

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The most memorable theater scene I’ve ever witnessed was performed one summer evening long ago in a courtyard at the University of Chicago. The play was Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, a complicated work from the 1920s about the relationship between authors, the stories they tell, and the audiences they seek.

At one point, a company of actors, having been interrupted in their rehearsal by a family of six seeking a playwright to tell their story, are bickering furiously with their interrupters when, at the opposite end of courtyard, two key members of the family had slipped away, to be suddenly illuminated by a spotlight as they stood beneath a tree to make a telling point: their story was as important as the play – maybe more. The act ended and the lights came up for intermission.

That was the technique known as up-staging with a vengeance, an abrupt diversion of attention from one focal point to another.

I remembered the experience after reading Three Prongs for Prudent Climate Policy, by Joseph Aldy and Richard Zeckhauser, both of the Harvard Kennedy School, a sharply critical appraisal of the prevailing consensus on the prospects for controlling climate change. Delivered originally as Zeckhauser’s keynote address to the Southern Economic Association in 2019, you can read it here for free at Resources for the Future. Its thirty pages are not easy reading, but they are formidably clear-headed, and I doubt that you can find a better roundup of the situation that the leaders are discussing blah-blah-blah next month at the U.N.’s Climate Change Conference in Glasgow.

The possibility of greenhouse warming was broached 125 years ago by the Swedish physical chemist Svante Arrhenius. The specific effect was discovered by Roger Revelle in 1957, and the growing problem brought into sharp focus in the U.S. by climate scientist James Hansen in Senate testimony in 1988. It has taken thirty years to reach a broad global consensus about the first of Aldy and Zeckhauser’s three prongs.

“For three decades, advocates for climate change policy have simultaneously emphasized the urgency of taking ambitious actions to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and provided false reassurances of the feasibility of doing so. The policy prescription has relied almost exclusively on a single approach: reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other GHGs. Since 1990, global CO₂ emissions have increased 60 percent, atmospheric CO₂ concentrations have raced past 400 parts per million, and temperatures increased at an accelerating rate. The one-prong strategy has not worked.’’

A second prong, adaptation, has been added in to most menus in recent years: everything from design changes (moving electric installations to roofs instead of basements) to seawalls, marsh expansions, and resettlement of populations. Adaptations are expensive. A six-mile long sea barrier with storm surge gates might protect New York City from climate change, but would take 25 years to build.

A third prong of climate policy ordinarily receives little attention. This is amelioration, or “the ‘G’-word,” as the chair of British Royal Society report dubbed it in 2009, meaning the broad topic of geo-engineering. For a dozen years, it was thought possible that fertilizing the southern oceans might grow more plankton, absorb more atmospheric carbon, and feed more fish. Experiments were not encouraging. The technique considered most promising today is solar-radiation management, meaning creating atmospheric sun-screens for the planet. The third prong is by far the last expensive of the three. It is also the most alarming.

Ever since “the year without a summer” of 1816, it has been known that volcanic eruptions, spewing sulfur particles into the atmosphere, produce worldwide net cooling effects. Climate scientists now believe that airplanes could achieve the same effect by spraying chemical aerosols at high altitudes into the atmosphere. The trouble is that very little is known with any certainty about the feasibility of such measures, much less their ecological effects on life below.

Many environmentalists fear that the very act of public discussion of solar- radiation management will further bad behavior – create “moral hazard” in the language of economists. Glib talk by enthusiasts of economic growth about cheap and easy redress of climate problems will diminish the imperative to reduce emissions of greenhouse governance, some say. Others think that sulfur in the air above would accelerate acidification in the oceans below. Still others doubt that global governance could be achieved, since such measures would not offset climate change equally in all regions, Rogue nations might undertake projects that they hoped would have purely local effects.

Aldy and Zeckhauser argue that bad behavior may in fact be flowing in the opposite direction. Climate change is an emotional issue; circumspection with respect to solar-radiation management is the usual stance; opposition to research is often fierce. As a result, very little has been performed. One of the first outdoor experiments – a dry run – was shut down earlier this year.

In his 2018 Nobel lecture, William Nordhaus, of Yale University, saw the problem somewhat differently.

“To me, geo-engineering resembles what doctors call ‘salvage therapy’– a potentially dangerous treatment to be used when all else fails. Doctors prescribe salvage therapy for people who are very ill and when less dangerous treatments are not available. No responsible doctor would prescribe salvage therapy for a patient who has just been diagnosed with the early stage of a treatable illness. Similarly, no responsible country should undertake geo-engineering as the first line of defense against global warming.’’

After a while, it seemed to me that the debate over global warming does indeed bear more than a little resemblance to what goes on in Pirandello’s play. Three possible policy avenues exist. The first is talked about constantly: the second enters the conversation more frequently than before. The third is all but excluded from mainstream discussion.

It’s not so much about what stage of a treatable illness you think we’re in. Public opinion around the world will determine that, as time goes by. It’s about whether the question of desperate measures should be systematically explored at all. The three-pronged approach is a policy in search of an author.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

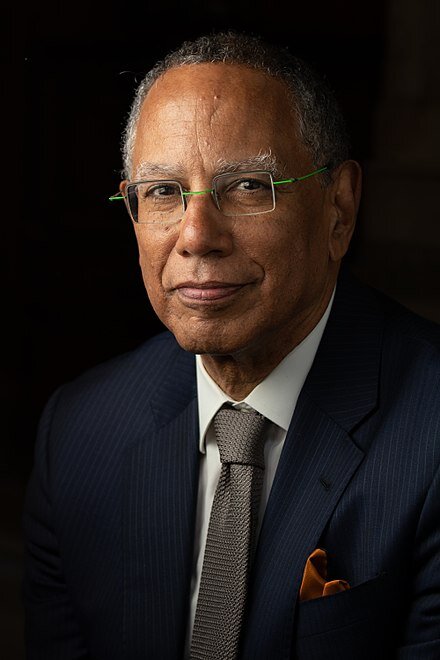

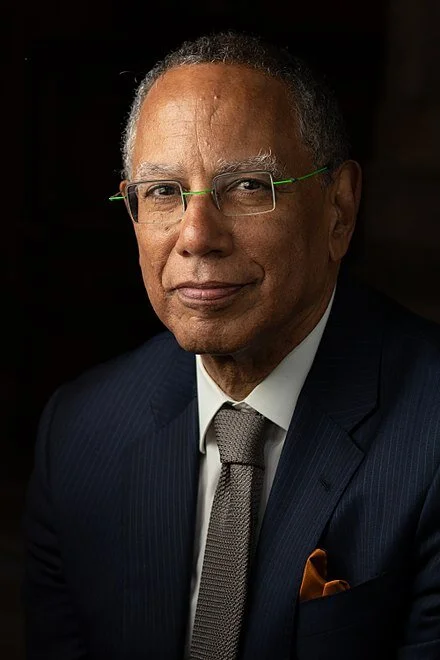

David Warsh: Of sportswriters, race and great news publications

New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Because it was August, I was reading Tall Men, Short Shorts, the 1969 NBA Finals: Wilt. Russ. Lakers. Celts, and a Very Young Sports Reporter (Doubleday, 2021). Leigh Montville was one of the many excellent sports columnists at The Boston Globe in the twenty years that I was there, somebody whom I always read no matter who or what he was writing about. After he was unreasonably refused an exit as columnist from the ghetto of sports, he left the paper for Sports Illustrated, where he wrote extended features and the back-of-the-magazine column for many years. He wrote eight books along the way. Tall Men, Short Pants is his ninth, a summing-up of much he learned about life in a fifty-year career as a journalist.

I’d been alerted to the book by The Globe’s former long-time managing editor, Thomas F. Mulvoy, who wrote about it in the Dorchester Reporter. At one point, Mulvoy says:

In a section that comes off the page with a sharp edge of sadness, Montville redresses himself (for the umpteenth time, his words suggest) for his silence at the press table when the Celtics played the Knicks in New York earlier in the season. A Globe colleague sitting next to him gave vent to his bigotry by loudly and repeatedly using the N-word while talking about the game being played in front of them. [Montville] writes: “I have thought for all these years of the things I should have done. I should have told [him] to shut up. Right away, I should have done that. If he didn’t shut up, I should have grabbed him, done something. … I should have reported all this to someone at the Globe on our return. I should have decided never to talk to him again. I should have done any of this stuff. I did nothing”

The 26-year-old Montville, who is White, served as no more than witness that day – the book reveals how he learned that his Globe colleague was deliberately baiting another Globe sportswriter, a well-known liberal, nearby – only much later affording a glimpse of the fractious mood of the nation in 1969. Montville attended his colleague’s wake thirty years later. Otherwise, he imaginatively covered changing attitudes about race in America, in columns and books, including Manute: The Center of Two Worlds (2011), and Sting like a Bee. Muhammad Ali vs. the United States of America, 1966-1971 (2017). Sports has done more than its share, and better than Hollywood, to illuminate rapidly changing stereotypes of race and class in the last fifty years. Montville was alert to the story every step of the way.

Reading Tall Men, Short Pants brought into focus a project of The New York Times of which I gradually became aware over the last couple of years.

I do not mean the paper’s scrutiny of the killings of Black men and the occasional Black woman by Whites, mostly police officers, before George Floyd was murdered by Officer Derek Chauvin, in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, though even now, thanks to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, it seems important to remember their names.

(Those whose stories made the front pages include Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Fla; Eric Garner, in Staten Island, New York; Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Mo.; Walter Scott, in North Charleston, S.C.; Philando Castile, in St. Paul; Stephen Clark, in Sacramento, and Breonna Taylor, in Louisville.

Nor do I mean the special issue of the magazine called The 1619 Project, the Times’s coverage of the debate over Critical Race Theory, or the series of essays by critic-at-large Wesley Morris that earlier this year was recognized with a Pulitzer Prize. I have in mind something less concrete but ultimately even more eye-opening, at least to me.

I am thinking of a surge of ordinary news stories about contributions to American culture by African-American citizens. These stories appeared in unusual numbers, day after day, over the course of the last eighteen months. In the trade, this kind of display is called ROP, or run of the paper, with stories placed anywhere in the paper at the option of an editor – world, U.S., politics, NY, business, opinion, tech, science, health, sports, arts, books, style, food, travel, real estate, obituaries. The surge was as unmistakable as it is difficult to describe. Instead of data, I have only personal experience of it, to which I aim to testify here, briefly.

I scan the print editions of The Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each morning at home, glance online at Bloomberg and study the story list of The Washington Post when I reach the office. In the evening, I read and clip (or print) whatever is most important to me. The differing trajectories of these five great English-language news organizations in the thirty years since the Internet emerged as a public communications medium has been fascinating, but that is a subject for another day. For now it is enough to say that The Times remains the most ambitious among them, more sparkling than ever in its aspirations.

It was the morning scanning of The Times that first produced the effect. So relentless had its coverage of Blacks newsmakers and their concerns become over the last year that one day it dawned on me what The Times had achieved. Some of the stories made big impressions. Others seemed peripheral, at least to my interests. I discussed the experience with my friend, Vincent McGee, who described it thus: “I first noticed it with obituaries, some current – mainly arts, music and sports – and others ‘catch ups’, often of Black women lost in history.”

By distorting its usual budget of stories – not much, mind you, this was only a surge – the newspaper’s editors had given me, a White reader, the feeling of somehow being unimportant. For some fleeting part of the day, I felt as many Black readers must feel most days, oppressed by the relentless attention The Times paid to the Other. This was showing, not telling, how it felt to be left out. It showed, too, what it meant to be included in. As an exercise in good newspaper editing, I will never forget it.

How had the decision to reorient the coverage been made? Anyone who knows anything about newspapers understands that inspiration comes from the bottom up. Orders are given, of course; stories are assigned, or turned back for more work. There are countless meetings, discussions, bull sessions, retreats. Word gets around. Better to say that a curiosity about race, gender, ethnicity and discrimination had been authorized at The Times as long ago as the Nineties, then encouraged, becoming wide-ranging, before coming to a low boil in 2020.

The Times’s executive editor is Dean Baquet, who was born in 1956. He is a consummate newspaperman, having started working in New Orleans even before graduating from Columbia University, in 1978. He moved from The Times-Picayune, in New Orleans, to the Chicago Tribune in 1984, where he won one Pulitzer Prize, and just missed another, before joining TheTimes, in 1990. Tribune Co. hired him back in 2000 to serve as managing editor of its newly acquired Los Angeles Times; he replaced John Carroll as editor in 2006 but was quickly dismissed after opposing newsroom budget cuts. He returned to The Times later that year as its Washington bureau chief, became its managing editor in 2011, and succeeded Jill Abramson in the top newsroom job in 2014.

Baquet is also a Black man, the fourth of five sons of a successful New Orleans restaurateur. Many years will be required to hash out all that has happened on his watch, some of it under the heading of “woke.” Baquet will write a book. Culture wars will continue. The equitable distribution of attention – of “play” – will become the next editor’s problem. Baquet turns 65 later this month; he will retire next year.

Leigh Montville won the Associated Press Sports Editors Red Smith Award in 2015; he never got out of the sportswriting ghetto, but he nevertheless became one of the finest columnists of his generation, pure and simple. Dean Baquet broke race out of the newspaper ghetto and made it ROP, maintaining news values evolved by the modern profession. He will enter history books as one of The New York Times’s greatest editors. Both men made the most of their opportunities.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

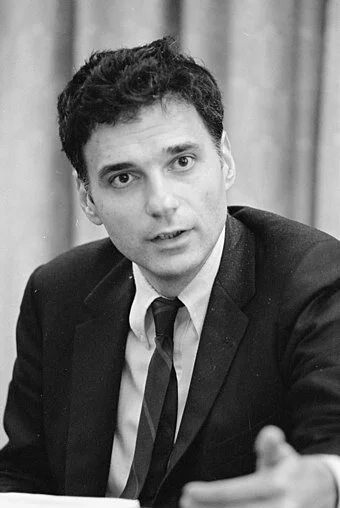

David Warsh: America’s fracturing ‘politics of purity’ since the ‘70s

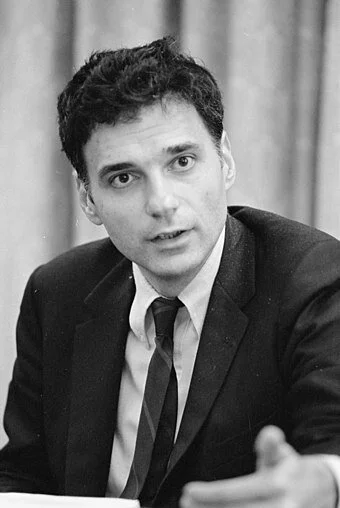

Ralph Nader in 1975, in his heyday

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Like a lot of people, I am interested in what has been happening in the world, the U.S. in particular, since the end of World War II. I am especially intrigued by goings on in university economics, but I take a broad view of the subject. I grew up in the Fifties, and the single most persuasive account I’ve found of the underlying nature of changing times since 1945 has been a series of five books by historian Daniel Rodgers, of Princeton University. In Age of Fracture (Belknap, Harvard, 2011), Rodgers described very well my experience of the increasingly thinner life of things.

Across the multiple fronts of ideational battle, from the speeches of presidents to books of social and cultural theory, conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions, and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones. Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind, the last quarter of the century was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.

But I’m always interested in a new narrative. One such is Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism (Norton, 2021), by historian Paul Sabin, of Yale University. Sabin employs the career of Ralph Nader, the arc of which extends from Harvard Law School and auto-safety crusader in Sixties to his Green Party candidacy in the U.S. presidential election of 2000, as a metaphor for a variety of other liberal activists who mounted assaults of their own on centers of government power in the second half of the 20th Century.

The harmonious post-war partnership of business, labor and government proclaimed in the Fifties by economist John Kenneth Galbraith and New Dealer James Landis, symbolized by the success of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s government-sponsored electrification of the rural South, was not built to last. But how did government go from being the solution to America’s problems to being the cause of them? It was more complicated than Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan, Sabin shows.

Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961), Rachel Carson (Silent Spring, 1962) and Nader (Unsafe at Any Speed. 1965), were exemplars of a new breed of critics of capture industrial manipulation and capture of government function, Sabin writes. Jacobs attacked large-scale city planning and urban renewal. Carson exposed widespread abuses by the commercial pesticide industry. Nader criticized automotive design. These were only the first and most visible cracks in the old alliance of industries, labor unions and federal administrative agencies. Public-interest law firms began springing up, loosely modeled on civil-rights organizations. The National Resources Defense Council; the Conservation Law Foundation; the Center for Law and Social Policy and many other start-ups soon found their way into federal courts. Nader tackled the leadership of the United Mineworkers Union, leading then-UMW President Tony Boyle to order the murder of reform candidate Tony Yablonski, his wife, and daughter, on New Year’s Eve, 1969.

In Age of Fracture, Rodgers wrote that “The first break in the formula that joined freedom and obligation all but inseparably together began with Jimmy Carter.” Carter’s outside-Washington experience as a peanut farmer and Georgia governor, as well as his immersion in low-church Protestant evangelical culture led him to shun presidential authority. “Government cannot solve our problems, it can’t set our goals, it cannot define our vision,” he said in 1978.

Sabin takes a similar view but offers a different reason for the rupture. Caught in between the idealistic aspirations of outside critics inspired by Nader and the practical demands of governing by consensus, Carter struggled to maintain the traditional balance but failed to placate his critics. “Disillusionment came easily and quickly to Ralph Nader,” Sabin writes. “I expect to be consulted, and I was told that I would be,” Nader complained almost immediately. Reform-minded critics attacked Carter from nearly every direction. A fierce primary challenge by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D.-Mass.) failed in 1980. The stage was set for Ronald Reagan.

Sabin recalls the battles of the 1970s with grim determination to show the folly of politics of purity. Nader made his first run for the presidency as leader of the Green Party in 1996, challenging Bill Clinton and Bob Dole. He was in his sixties; his efforts were half-hearted. In his second campaign, in 2000, he campaigned vigorously enough to tip the election to George W. Bush. Even then it wasn’t Nader’s last hurrah. He ran again, in 2004, as candidate of the Reform Party; and a fourth time, as an independent, in 2008. At 87, he is today conspicuously absent from the scene.

The public-interest movement initiated by urbanist Jane Jacobs, scientist Rachel Carson and Ralph Nader was effective in its early stages, Sabin concludes. The nation’s air and water are cleaner; its highways and workplaces safer; its cities more open to possibility. But Sabin is surely right that all too often, go-for-broke activism served mainly to undermine confidence in the efficacy of administrative government action among significant segments to the public.

The critique of federal regulation was clearly not the whole story, any more than was The Great Persuasion, undertaken in 1948 by the Mont Pelerin Society, pitched unsuccessfully in 1964 by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, and translated into slogans in 1980 by Milton and Rose Friedman. Nor is the thoroughly disappointing 20-year aftermath to 9/11, another day when the world seemed to many to “break apart,” as historian Dan Rodgers put it in an epilogue to Age of Fracture.

What might put it back together? Accelerating climate change, perhaps. But that’s another story.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

David Warsh: Time to read ‘Three Days at Camp David’

The main lodge at Camp David

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The heart-wrenching pandemonium in Kabul coincided with the seeming tranquility of the annual central banking symposium at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. For the second year in a row, central bankers stayed home, amid fears of the resurgent coronavirus. Newspapers ran file photos of Fed officials strolling beside Jackson Lake.