So close to us

“Pileated {Woodpecker} Feeding Its Young” (photo), by Linda Cullivan, in the 19-person photography show “Birds,’’ at Cove Street Arts, Portland, Maine, through Feb. 19.

The show quotes the great English naturalist, and TV presenter, Sir David Attenborough:

"Everyone likes birds. What wild creature is more accessible to our eyes and ears, as close to us and everyone in the world, as universal as a bird?"

Ms. Cullivan lives in Scarborough, in southern Maine.

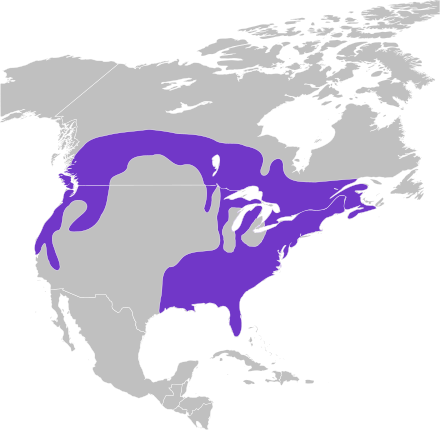

The Pileated Woodpecker’s unusual range

Scarborough from the air, looking to the southeast. Note the Prouts Neck Peninsula (where Winslow Homer did many of his paintings), and the Scarborough River and its tributaries.

Higgins Beach in Scarborough

Llewellyn King: The decline of two reliable Christmas gifts

— Photo by Ana Cotta

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

You may have noticed that gift-gifting was a bit more difficult this holiday season. Those two mighty standbys for the gift-givers, perfume and neckties, have moved from the “always welcome’’ list to the ‘‘What was he or she thinking?’’ list.

Perfume – oh, that never-surprising but always-delighting gift – isn’t the gift it used to be. The problem is scent wearing by women has fallen off, as health concerns about volatiles in the air have grown and casual dressing, especially in the time of pandemic, is de rigueur.

Pity – luxury perfume was the unchallengeable gift. It was giving on the strength of its brand, like Miss Dior or Chanel No. 5. Labels really counted in fragrance giving. You were ill-advised to try anything out of the usual. If you espied something called, say, Rocky Mountain Rose, you were advised to eschew it.

The best and easiest to give was Joy by Jean Patou. The fragrance advertised itself as “the most expensive perfume in the world.” Bingo! You couldn’t go wrong if you had the bucks. I used to give a small bottle of Joy to my office manager every year and was thanked with oohs and aahs, even though she knew what was coming. She explained that a woman’s real use of Joy wasn’t so much in wearing it (and she wore it with pleasure), but in displaying it – showing her friends how much her significant other loved her. I rush to say that wasn’t my role in her life.

Neckties were the perfect gift for the man who might have everything. A man couldn’t have too many, and a new one in the style of the day was genuinely welcomed to the sartorial collection.

The necktie is rapidly going the way of spats, detachable collars, and Homburgs, to oblivion.

So shed a tear for the necktie and its infinite giveability. You could play the brand game, but there was no need for that. An obscure neckwear maker, doing a good job with the silk or wool, would be just as fine an accoutrement, as a luxury name like Givenchy or Ralph Lauren. The outstanding exception to this rule was some fabulous work of art by Liberty of London. That would earn deep approval, a friendship cementer.

As a generalization though, an unknown name in neckwear was just as good as the names of the great designers. To those in the know, the best place to buy ties at a reasonable price is, for reasons unknown, at hotel gift shops. Good ties at great prices.

Ties were in their day so important that good restaurants and clubs had selections of ties to fix up men who came with – Shock! Horror! -- an open-necked shirt. The proprietor of a famous Manhattan restaurant of yore, La Cote Basque, told me he wouldn’t serve a king if he wasn’t wearing a tie. La Cote Basque has long gone and so that poor man was never put to the test of facing down royalty.

I wear a bowtie. I have Tucker Carlson – yes, that Tucker Carlson — to thank for that change in my appearance, that bit of sartorial shtick. When I met Carlson, long before he found, as one writer said of someone else, the cramped space to the right of Rupert Murdoch, he was a funny, likable conservative who had just left a CNN talk show and authored an amusing book about the experience of being TV chatterer.

I had him as a guest on my television program, White House Chronicle, on PBS. He was known as a bowtie-wearer and, as a joke, I donned one. I got so many favorable comments that I’ve taken to wearing them instead of the long, silk emblems of the once well-dressed man.

Shame, I say, on the retreat of perfume and the near extinction of the necktie. Women don’t smell so elegant, and men look unfinished.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Jim Hightower: Fossil-fuel companies rush to create even more plastic pollution

Via OtherWords.org

In a world that’s clogged and choking with a massive overdose of plastic trash, you’ll be heartened to learn that governments and industries are teaming up to respond forcefully to this planetary crisis.

Unfortunately, their response has been to engage in a global race to make more plastic stuff — and to force poor countries to become dumping grounds for plastic garbage.

Leading this Kafkaesque greedfest are such infamous plunderers and polluters as Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Shell and other petrochemical profiteers. With fossilpfuel profits crashing, the giants are rushing to convert more of their over-supply of oil into plastic.

But where to send the monstrous volumes of waste that will result? The industry’s chief lobbyist outfit, the American Chemistry Council, looked around last year and suddenly shouted: “Eureka, there’s Africa!”

In particular, they’re targeting Kenya to become “a plastics hub” for global trade in waste. However, Kenyans have an influential community of environmental activists who’ve enacted some of the world’s toughest bans on plastic pollution.

To bypass this inconvenient local opposition, the dumpers are resorting to an old corporate power play: “free trade.” Their lobbyists are pushing an autocratic trade agreement that would ban Kenyan officials from passing their own laws or rules that interfere with trade in plastic waste.

Trying to hide their ugliness, the plastic profiteers created a PR front group called “Alliance to End Public Waste.” But — hello — it’s not “public” waste. Exxon and other funders of the alliance make, promote, and profit from the mountains of destructive trash they now demand we clean up.

The real problem is not waste, but plastic itself. From production to disposal, it’s destructive to people and the planet. Rather than subsidizing petrochemical behemoths to make more of the stuff, policymakers should seek out and encourage people who are developing real solutions and alternatives

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

‘Now whispered and revealed’

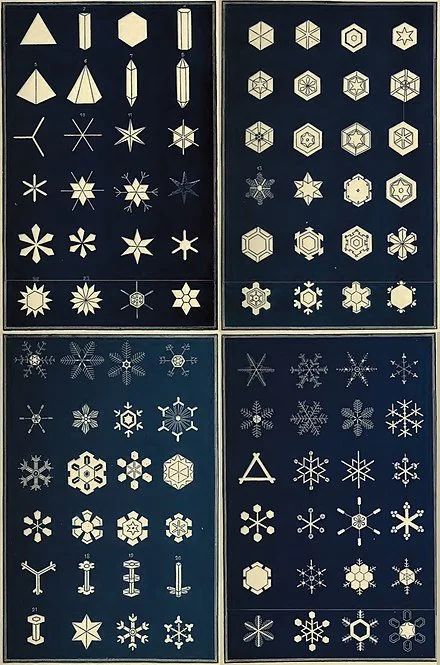

An early classification of snowflakes by Israel Perkins Warren (1814-1892) American Congregational minister, editor and author who lived in Connecticut and Maine.

Out of the bosom of the Air,

Out of the cloud-folds of her garments shaken,

Over the woodlands brown and bare,

Over the harvest-fields forsaken,

Silent, and soft, and slow

Descends the snow.

Even as our cloudy fancies take

Suddenly shape in some divine expression,

Even as the troubled heart doth make

In the white countenance confession,

The troubled sky reveals

The grief it feels.

This is the poem of the air,

Slowly in silent syllables recorded;

This is the secret of despair,

Long in its cloudy bosom hoarded,

Now whispered and revealed

To wood and field.

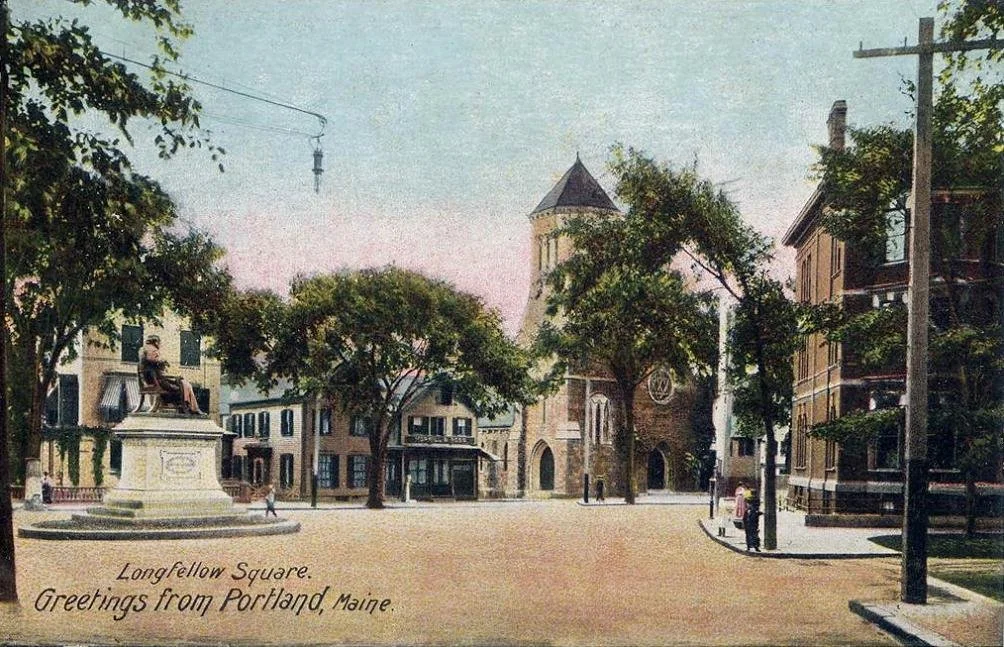

“ Snow-Flakes,’’ by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882). The Portland, Maine, native was the most revered American poet of his time as well as a famed professor and translator (most notably of Dante) at Harvard. His reputation, long in eclipse, has lately been in a revival.

Longfellow Square, with statue of the poet, circa 1906

Going their own ways

In the Litchfield Hills: Bridgewater, Conn. — houses, farms and fields, as seen from Brookfield

— Photo by Liam E

“The Yankee mind was quick and sharp, but mainly it was singularly honest.’’

— Van Wyck Brooks (1886-1963), once-famous historian, biographer and literary critic, in The Flowering of New England

He spent much of his life in Bridgewater, Conn., long a weekend and summer place for affluent New Yorkers

xxx

“Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist.’’

— Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), world-renown essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist and poet. He spent most of his life in what we now call Greater Boston.

Thank God for that little cardinal

“Winter” (oil on canvas), by Daniel Heyman, at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, through Dec. 31

Tools of old-fashioned daily work

“Intimations” (oil on linen) by Middlebury, Vt.-based painter Kate Gridley, at Edgewater Gallery, in Middlebury. Her Web site says:

“Known for her insights into human character, the quality of light in her work, and her painting technique, Kate Gridley maintains a studio in Middlebury, Vermont, where she has lived and painted full time since 1991.’’

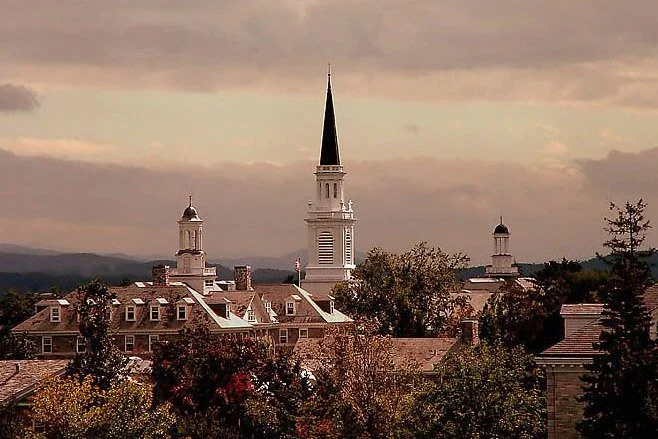

At Middlebury College, with the Green Mountains in the background

Chris Powell: Why it’s so tough to reduce domestic violence in our disintegrating society

Cycle of abuse, power and control issues in domestic-abuse situations

— Graphic by moggs oceanlane

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut, the state's Hearst newspapers found this month in a series of investigative reports, has not made much progress solving its domestic- violence problem. Of course studies of the state's other major problems might reach a similar conclusion, but one has to start somewhere.

Connecticut's main response to domestic violence is the protective order, with which a court warns an allegedly abusive party to stay away from the party who feels abused. The dark joke has been that every woman murdered by her husband or boyfriend dies clutching a protective order. That is, protective orders aren't terribly effective, as the Hearst series showed.

The series found that a protective order had already been issued in a quarter of the 15,500 domestic violence incidents reported to police in Connecticut in 2020. A fifth of domestic violence charges in the state's courts from 2016 to 2020 involved at least one violation of a protective order, and many of those charges were dismissed. Only about 20 percent of the 23,000 protective-order violations charged in those years resulted in convictions.

Most of those charges were resolved by plea bargains or the referral of the accused to a rehabilitation program.

And so about 300 people, mostly women, have been killed by domestic violence in Connecticut in the last 20 years. Many more have been injured.

The data call for more vigorous enforcement. But then so do the data for most crimes in Connecticut. For all criminal justice is a system of discounting charges via plea bargains and probationary programs, because there is far more crime than resources to prosecute them and because Connecticut's criminal-justice system strives most of all to keep perpetrators out of jail.

Other than domestic violence, it is hard to find any serious crime in Connecticut where the defendant doesn't already have a long criminal record but has remained free or suffered only short imprisonment, since the state lacks an incorrigibility law.

The Hearst series reported that domestic violence cases are discounted in court more often than equally serious crimes, but this is misleading, for domestic violence cases can be more difficult to prosecute. More of their evidence is uncorroborated testimony -- "he said, she said" cases -- more of their accusers lose the desire to testify, and fewer of the accused have long records indicating a danger to anyone besides their accusers.

As the stream of domestic violence deaths and injuries suggests, protective orders, rehabilitation programs and social workers are no substitute for speedy trials, convictions, and imprisonments. Meanwhile, there is always infinite demand for government to protect people against all the risks of life.

But government can't protect everyone from everything all the time, and, distracted by the virus epidemic, government now is less able to protect everyone from even ordinary threats. Until Connecticut is ready to prosecute, convict and imprison abusers quickly or to hire round-the-clock bodyguards for everyone threatened by domestic violence, people will have to be ready to protect themselves and take some responsibility for the awful partners they have chosen.

It's an unpleasant thought, but then nothing is gained by ignoring the social disintegration worsening all around, of which domestic violence is only one part.

xxx

Responding to recent commentary in this space, a reader writes that if Bob Stefanowski can get next year's Republican nomination for governor without a primary, he has a chance to beat Gov. Ned Lamont. But if Stefanowski has to run in a primary, "he will have to kiss up to every Trump-supporting, gun-toting, anti-abortion nut in the Republican Party" and then the nomination will be worthless.

Another reader counters: If Governor Lamont wins renomination by the Democrats without a primary, he has a chance to beat Stefanowski. But if Lamont faces a primary, "he will have to kiss up to every AOC-Squad-supporting, illegal-gun-toting, pro-abortion nut in the Democratic Party," and then his nomination will be worthless.

Yes, both parties have extremes that can dominate their primaries, and the governor has done a fairly good job tiptoeing away from his party's crazy left. Can Stefanowski get around his party's crazy right?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

David Warsh: Hillary in ‘24 and a second Yalta agreement?!

— Photo by Niele

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” William Faulkner’s well- remembered adage (from Requiem for a Nun) was underscored last week when John Ellis, a vigorous second-presidential-generation member of the Bush clan, published a special edition of his six-days-a-week newsletter describing an “invisible primary” that has begun unfolding among the Democrats.

Whatever may be in the offing among the Republicans for 2024, Ellis said, Hillary Clinton is preparing a possible run for the Democratic presidential nomination then. Biden will be too old to run again, he averred; the Democrats’ Plan B has become a “jump ball.” Hence the shadow-boxing that Clinton has begun, most recently in the form of a subscription “Masterclass” in which she performed the speech she planned to deliver in 2020 had she won. “She can win the nomination [in 2024],” Ellis wrote. “She might not. But don’t for a minute think she can’t.”

It is against this background that the current Ukraine “crisis” should be understood – those 100,000 Russian troops practicing war games nears the Ukrainian border. In keeping with Putin’s long-standing habit of setting out policies in a series of documents and speeches, Russia last week set forth an elaborate series of proposals for a post-Cold War national-security agreement between Russia, the U.S. and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Putin first called for a “a new Yalta” after annexing Crimea in 2014, The old Yalta Conference (code-named Argonaut!) took place on the Crimean peninsula in the waning days of World War II. It was there that Franklin Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill and their deputies carved Europe into spheres of influence along lines ratified a few months later in Potsdam, Germany.

What to make of all this? When Biden came into office, imagine Putin’s surprise to find Victoria Nuland newly installed as undersecretary of state for political affairs. Nuland, you may remember, is the former Hillary Clinton press secretary who, as assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs in the Obama administration, was taped by Russian security agents instructing the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine to “fuck the E.U.” during Ukraine’s 2014 “Snow Revolution.” Earlier, she and former GOP presidential candidate John McCain had passed out cookies to demonstrators in Kyiv’s Maiden Square. Last week Nuland was threatening to throw Russia out of the international payments system known as SWIFT if its army invaded Ukraine, while Biden weighed proposals to send left-over helicopters intended for Afghanistan to Ukraine.

Why did Biden nominate Nuland? That’s for The Washington Post to find out and explain. But from Putin’s point of view, the American president’s overreach on foreign policy must have seemed as striking as did Biden’s domestic policy plans to congressional Republics and a couple of moderate Democrats in the Senate.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said Friday that Russia was a nation in economic decline. Putin clearly thinks the U.S. itself is declining, lacking cohesion. Presumably, the Russian leader is posturing, waiting for the results of the next U.S. presidential election to emerge. He may want a “new Yalta agreement,” but until a few years ago, a slow-motion, wide-ranging face-saving maneuver seemed more likely on the part of the West with respect to NATO expansion. Something analogous to the little-noticed concessions President Kennedy gave Russia in exchange for its high-profile retreat from the Cuban Missile Crisis might have served. Today it seems likely that Putin may be able to extract more than that with his bullying threats.

It all depends on the next presidential election. A re-run of the 2016 contest would clearly be a disaster. The past may always be with us, but the future is unclear because it hasn’t happened yet.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Of ends and means in building a great museum

The famed courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, built in 1896-1903 in Boston’s Fenway section, financed and directed by Mrs. Gardner (1840-1924), a very rich arts collector and patron originally from New York who married a Boston Brahmin, Jack Gardner. The museum, unfortunately, may be most famous as the site of the world’s greatest art theft, in 1990. They’re still looking for the hundreds of millions of dollars in stolen paintings.

“The imagination of Isabella Stewart Gardner yielded a remarkable achievement in the museum to which she gave her name and treasure. But it is an achievement easily overlooked. Because she was rich and famous, we are too willing to gape at her legacy, with dollar signs in mind. And because she was eccentric, there also is scarcely any story we will not credit, however much it sensationalizes and trivializes her. We seem relentlessly more interested in her means than in her ends. It is a losing battle, perhaps, for a historian to try to set the record straight.”

— Douglass Shand-Tucci (1941-2018), Boston architectural historian and author of a 1997 biography of Mrs. Gardner, The Art of the Scandal, in a 1990 Boston Globe interview.

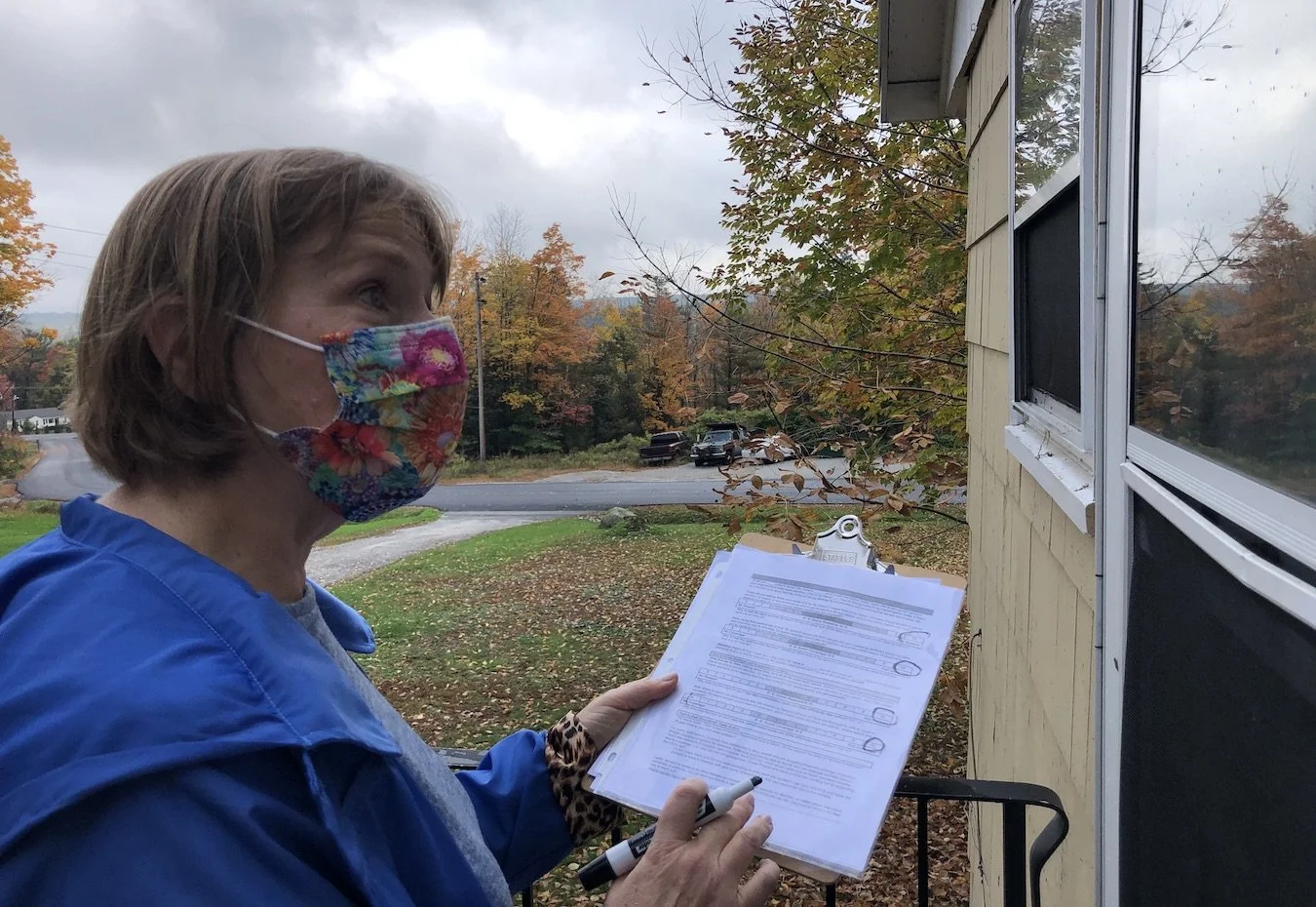

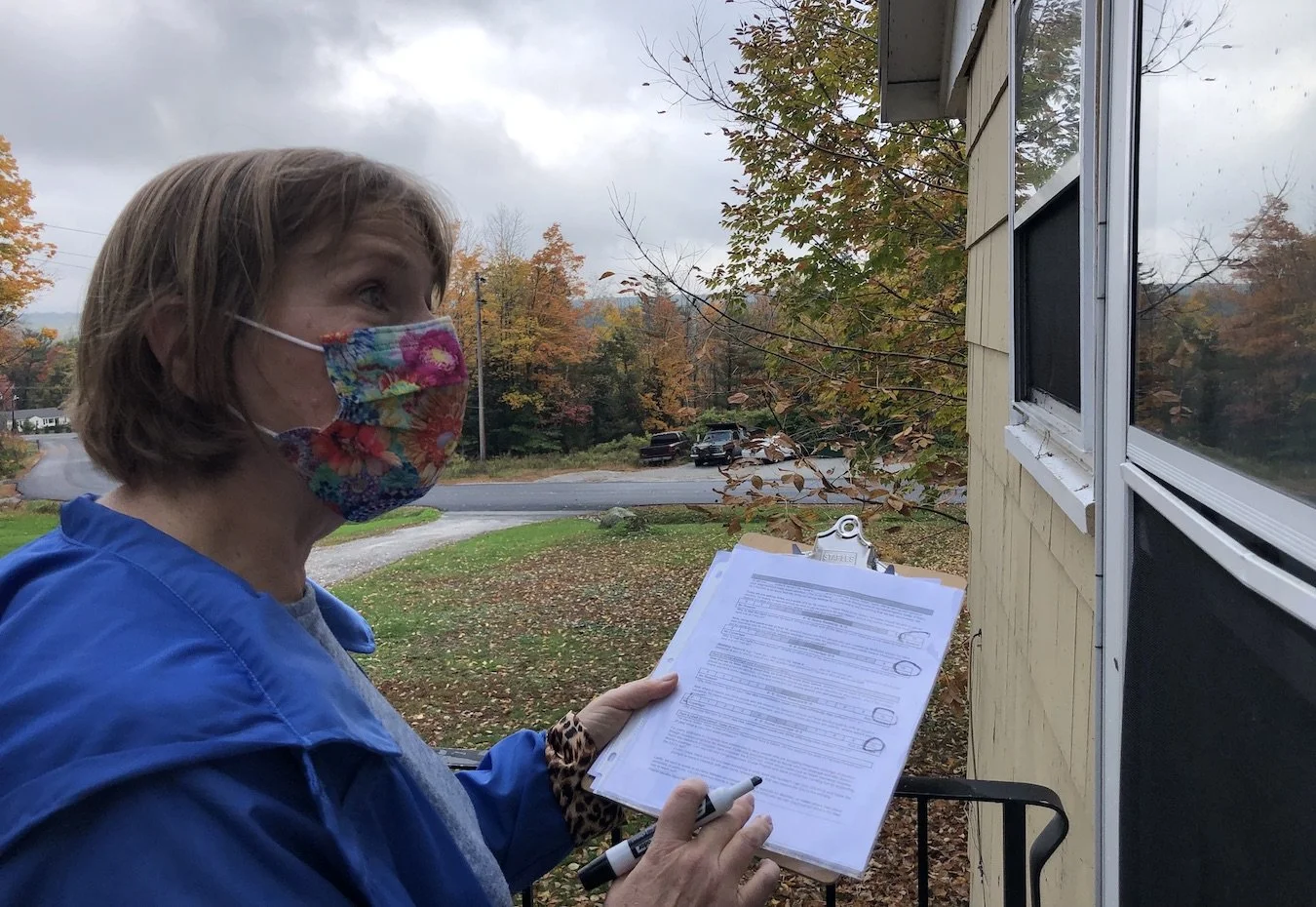

Patty Wight: Maine abortion-rights advocates try to change minds by going door to door

Planned Parenthood volunteer Sarah Mahoney talks to a voter about abortion access outside a home in Windham, Maine.

— Photo by Patty Wight/Maine Public Radio

It’s Saturday, and Sarah Mahoney is one of several Planned Parenthood volunteers knocking on doors in Windham, Maine, a politically moderate town not far from Portland.

No one answers at the first couple of houses. But as Mahoney heads up the street, she sees a woman out for a walk.

“Hey! We’re out canvassing,” she says. “Would you mind having a conversation with us?”

Mahoney wants to talk about abortion — not a typical topic for a conversation, especially with a stranger. But the woman, Kerry Kelchner, agrees to talk. If this were typical door-to-door canvassing, Mahoney might ask Kelchner about a political candidate, remind her to vote and then be on her way. But Mahoney is deep canvassing — a technique that employs longer conversations to move opinions on hot-button issues.

Planned Parenthood in Maine has deployed the strategy for several years amid what it says are increasing threats to reproductive rights. This year alone, states have enacted more than 100 restrictions on abortion, including one in Texas that bans most abortions after six weeks. This month, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in a case about a Mississippi law that could lead to the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 ruling that established a constitutional right to abortion. And though state law in Maine protects abortion rights even if Roe v. Wade is overturned, abortion opponents have gained traction in the state in recent years. So volunteers like Mahoney start conversations. And they can get quite personal.

Mahoney first assesses Kelchner’s baseline attitude on abortion access on a scale of 0 to 10. A 10 means the interviewee believes anyone should be able to get an abortion for any reason.

Kelchner says she’s a 7.

Next, Mahoney asks Kelchner a series of questions to better understand her values.

“Can you tell me a little bit about what shaped your views on abortion?” she asks. “Have you known anybody who’s had an abortion, a friend or a family member?”

“My mother,” says Kelchner. She explains her parents were young when she was born, and they weren’t ready for another baby.

Then Mahoney, who’s 60, shares that she also had an abortion. “I was in my early 20s,” she says. “I was a little conflicted about it, and I wanted to have a family. I knew I wanted to have a family, but I was in no way ready to do that.”

Mahoney points out that she and Kelchner have similar views on what an unplanned pregnancy can mean. Then she asks her opening question again, to see whether Kelchner’s feelings about abortion access have shifted on the 0-to-10 scale.

“Still around 7,” Kelchner says.

Mahoney probes further. “What would be the circumstances where you would say, ‘No — they shouldn’t have the right to have an abortion?’”

Kelchner pauses. “That’s a good question.”

They talk more. Ultimately, Kelchner can’t think of any circumstance in which she believes someone should be denied an abortion.

“There should be no judgment,” she says.

“So that would be a 10?” Mahoney asks.

“Yep,” says Kelchner.

In the five years she’s been deep canvassing for Planned Parenthood, Mahoney said, she hasn’t had a single unpleasant conversation.

“What we’ve found doing this is that it is an effective way to change minds about abortion,” said Amy Cookson, director of external communications for Planned Parenthood of Northern New England.

Cookson said Planned Parenthood started deep canvassing in Maine in 2015, after Paul LePage, an anti-abortion Republican, won a second term as governor. Gay rights advocates in California had used deep canvassing on the same-sex marriage issue, and she wondered: “Can it work around abortion stigma?”

Joshua Kalla, a political scientist at Yale University, has conducted research that found the technique can change people’s deeply held beliefs. The crucial elements are that canvassers listen without judgment and share their own stories.

“So whether the person had an abortion and is talking about their abortion story,” said Kalla, “or whether the person is an ally and is talking about a friend or family member who had an abortion and is sharing that story, the effects seem to be quite similar.”

Kalla has also studied Planned Parenthood’s efforts in Maine and said the group has added something else that’s effective: moral reframing. Canvassers listen for the moral values a voter emphasizes and then incorporate those values into the story they share.

But deep canvassing is not exclusively a progressive tactic, Kalla said. Conservative groups can use it, too, and he thinks that would improve political discourse: “You know, it would be good for American society if the way we had political conversation was more grounded, and listening to the other side, and being nonjudgmental, and being curious.”

Back in Windham, Mahoney continues to walk through the neighborhood. She meets a man outside his apartment building who gives only his first name, Chris. He says he’s a 4 on the abortion access scale. He opposes abortion except in cases of sexual assault. Chris tells Mahoney that he had a daughter when he was 15.

“Do you talk about, I’m curious, birth control and abortion?” Mahoney asks.

“I do with her a lot,” Chris says. She’s a teenager, he says, and he’s not sure what he’d do if she got pregnant accidentally.

“It’s her own life,” he says. “I don’t know if I would even try to change her mind. Because it’s her decision.”

As the conversation goes on, Chris seems as though he supports access to abortion. But at the end, he doesn’t budge on his rating.

Mahoney said that’s OK. Some people won’t change their minds right away.

“The worst way to think about this is that it’s some kind of Jedi mind trick,” she said, “and I’m going to let them talk about themselves and then — pow! — I’m going to change their mind.”

What Mahoney wants most from these conversations is for people to think more deeply about the nuances around abortion and identify common ground: “I just feel like we all need to be taking steps to hear one another and move towards each other, instead of just diving into this divisive, contrary, hostile, red and blue world.”

Because of the success Planned Parenthood in Maine has had with deep canvassing, it has trained volunteers in other states, including Texas and Kansas. Next year, Kansas voters will cast ballots on a referendum question that seeks to revoke abortion access as a fundamental right.

Patty Wight is a journalist with Maine Public Radio.

This story is part of a partnership that includes Maine Public Radio, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Not precisely bustling Main Street in the village of South Windham c. 1910.

Windham’s motto is “Windham Works for Maine’’

And indeed, the town, now mostly a Portland suburb and summer resort area because of its location on large and beautiful Sebago Lake , once was a thriving industrial center.

In 1859, for example, when Windham's population was 2,380, it had eight sawmills, a corn and flour mill, two shingle mills, a fulling mill, two carding mills, a woolen textile factory, a barrel factory, a chair-stuff factory, a famous gunpowder factory and two tanneries.

Oriental Powder Company, Maine’s largest gunpowder factory, remained in operation until 1905 providing rock-blasting powder, gunpowder for the Crimean War, and 25 percent of the the Union gunpowder supply for the Civil War.

A charcoal house, saltpeter refinery, mills and storehouses were separated along a mile of both banks of the Presumpscot River to minimize damage during infrequent explosions.

Beach at Sebago Lake State Park. The lake is lake-rich Maine’s second largest, after Moosehead.

Beautiful day in the branches

This hawk — or is it an owl? — seems well camouflaged on a bright December day on the Brown University campus, in Providence.

— Photo by Lydia Whitcomb

And that was before the private-equity folks

Edgartown Harbor

—Photo by D Ramey Logan

Main Street in Vineyard Haven

“Today the human footprint is all over the place. The old salts and first families are only dimly evident, towns are run by business interests….No one even considers the possibility of keeping the Island as it was. Instead they debate the ideal rate of growth.’’

Anne W. Simon, (1914-1996) in On the Vineyard II (1990). She was a rich American author, writer and environmentalist who summered on Martha’s Vineyard.

Snowstorms: Joy and agony; Jewish Christmas songs

The Dec. 12, 1960 blizzard prepares to slam New England.

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I wrote this on the anniversary of a Dec. 12, 1960 blizzard I remember well partly because I was soon to move to another town, and so I’m thinking about snowstorms as a young person.

When my four siblings and I were kids, we loved the drama of big snows. The stillness before the first flakes, which in memory always seemed to come late at night. Then the muffled sound of the snowplows around dawn, as the northeast wind came up, as it did sometimes ferociously where we lived on a hill along Massachusetts Bay

Then, school having been cancelled (oh happy day!), we went out in our itchy and water-absorbing woolen snow pants, coats, mittens, caps and vulcanized rubber boots, with buckles, into the white and the wind, taking particular pleasure in the drifts, into which we’d try to make snow caves. With all this activity, a pair of gloves would rarely remain together for more than a week or two.

The day after the storm, if we were fortunate enough to again have no school, we’d enjoy what was usually a bright, crisp, crackling-dry and exhilarating day, with sledding and even a little skiing, though the work needed to climb up our little hill soon made that pall. On our way to a higher hill, it was fun to drag a toboggan on roads that the town hadn’t gotten around to plowing yet. The town was ours!

I should have known to feel sorry for my father, who had to do most of the snow-shoveling (until I was about eight and could seriously help) and often found it very difficult to get to his job in downtown Boston during and after blizzards. But as usual, he never complained. Some years in the future we children, like him, also came to see snowstorms, whatever their brief beauty, simply as irritating inconveniences in obligation-heavy workaday lives.

Indeed, as thaws and rain left a glaze of ice on the snow after cold fronts pushed in, and the snowbanks along roads became filthy with sand and dog poop in a town where most of these creatures ran around unleashed, even we as kids lost the joy of what the radio and TV people insisted on relentlessly calling the “white stuff’’.

After a few days, we were happy that a warm, southeast rainstorm would wash away all or most of the snow – until the next nor’easter came up the coast and brought more snow, which we’d enjoy for only a couple of days.

Of course, without weather satellites and the many other high-tech forecasting gizmos we have now, predictions weren’t nearly as accurate back then. Every once in while there would be a surprise snowstorm. I remember one that led Carl DeSuze, a WBZ radio personality, to jovially taunt the station’s chief meteorologist, Don Kent, with:

“Well, Don, I shoveled eight inches of ‘partly cloudy’ off my sidewalk today.’’

Have Yourself a Secular Christmas

Robert May, who was a secular Jew by background, created the Rudolph story, which May’s brother in law Johnny Marks, who also was Jewish, turned into an alarmingly popular song. May converted to Catholicism late in life.

Jews wrote all or part of most of the best known American nonreligious Christmas songs, mostly created in the mid-20th Century. Among them:

“White Christmas”; “Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas” (deliciously maudlin!); “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” (also maudlin); “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town”; (retailers’ favorite?); “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer”; “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year” (revolting song!) and “The Christmas Song’’ (“Chestnuts Roasting Over an Open Fire”). The last could be called cocktail-lounge music, perfect for a wan, cigarette-smoking pianist with a drink by his side.

Why? Well for one thing, Jews found that music was one field (another was the movies) open to them in an era when anti-Semitism was still rife in America. And many Jewish immigrants brought a high appreciation for music with them from Europe. Further, Christmas in the mid-20th Century was becoming more of a secular (and commercialized) celebration and diversion in the darkest days of the year and less a Christian feast day. Note, by the way, that Dec. 25 is the only federal holiday that’s also a religious one.

Anyway, a special thank God for the Jews at Christmas. And remember that Christianity started as a Jewish sect.

Michelle Andrews: In Conn., a 'facility fee' for a televisit to a hospital

The Yale New Haven Hospital campus

When Arielle Harrison’s 9-year-old needed to see a pediatric specialist at Connecticut’s Yale New Haven Health System in June, a telehealth visit seemed like a great option. Since her son wasn’t yet eligible to be vaccinated against COVID-19, they could connect with the doctor via video and avoid venturing into a germy medical facility.

Days before the appointment, she got a notice from the hospital informing her that she would receive two bills for the visit. One would be for the doctor’s services. The second would be for a hospital facility fee, even though she and her son would be at home in Cheshire, Conn., and never set foot in any hospital-affiliated building.

Harrison, 40, who works in nonprofit communications, posted on Twitter about the unwelcome fee, including an image of Marge Simpson of TV’s The Simpsons with a disgusted look on her face, captioned “GROANS.”

She called the billing office the next morning and was told the facility fee is based on where the doctor is located. Since the doctor would be on hospital property, the hospital would charge a facility fee of between $50 and $350, depending on her insurance coverage.

“It’s just one of many examples of how this is a very difficult system to use,” Harrison said, referring to the intricacies of U.S. health care

Hospital facility fees have long come under criticism from patients and consumer advocates. Hospitals say the fees, which can add hundreds of dollars or even more than $1,000 to a patient’s bill, are necessary to cover the high cost of keeping a hospital open and ready to provide care 24/7.

But it’s not only hospital visits that result in facility fees. Over the past several years, hospitals have been on a buying binge, snapping up physician practices that often then begin charging the fees, too. Patients seeing the same doctor for the same care as at earlier visits are now on the hook for the extra fee — because of a change in ownership.

Charging a facility fee for a video visit where the patient logs in from their living room is even more of a head-scratcher.

“The charges seem crazy,” said Ted Doolittle, who heads up Connecticut’s Office of the Healthcare Advocate, which provides help to consumers with health coverage issues. “It rankles, and it should.”

Facility fees for video appointments remain rare, health finance experts say, even as the use of telehealth has soared during the covid pandemic. Medicare has allowed hospitals to assess a small fee for certain beneficiaries who get telehealth care at home during the ongoing national public health emergency, and people in private health plans may also be charged for them.

Harrison, however, was lucky. Doolittle reached out to her after seeing her tweet to offer his office’s assistance. In Connecticut, hospitals are prohibited from charging facility fees for telehealth visits.

Connecticut imposed what may be the only state ban on telehealth facility fees as part of a broader law passed in May that was intended to help residents access telehealth during the pandemic. The prohibition on facility fees sunsets at the end of June 2023.

Pat McCabe, senior vice president of finance at Yale New Haven Health System, said he can’t explain why Harrison received a notice that she’d be charged a facility fee for a telehealth visit. He speculated that her son’s appointment might have been coded incorrectly. Under the new law, he said, the health system hasn’t charged any telehealth patients a facility fee.

But such fees are justified, McCabe said.

“It offsets the cost of the software we use to facilitate the telehealth visits, and we do still have to keep the lights on,” he said, noting that the providers doing telehealth visits are on hospital sites that incur heat and power and maintenance charges.

The American Hospital Association didn’t respond to requests for comment about the rationale for facility fees for telehealth care.

As the pandemic began overwhelming the health system last year, hospitals essentially closed their doors to most non-covid patients.

Telehealth visits, which made up about 1% of medical visits before the pandemic, jumped to roughly 50% at its height last year, said Kyle Zebley, vice president of public policy at the nonprofit American Telemedicine Association, which promotes this type of care. Those appointments have dropped off and now make up roughly 15% of medical visits across all types of coverage.

Before the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services severely limited telehealth coverage for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. But with seniors more vulnerable during the pandemic, the agency loosened telehealth rules temporarily. As long as the public health emergency continues, the agency is allowing Medicare beneficiaries in urban areas to receive such care, which was previously covered only in rural areas. And patients can get telehealth care at home rather than having to go to a medical facility for the video appointment, as was previously required. The agency also beefed up covered telehealth services and expanded the types of providers who are allowed to offer them.

Medicare lets hospital outpatient departments bill about $27 for telehealth visits for certain beneficiaries receiving care at home. Patients are generally responsible for 20% of that amount, or about $5, although providers can waive patient cost sharing for telehealth, said Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the Program on Medicare Policy at KFF.

At the beginning of the pandemic, patients with commercial health plans were often not charged a copay for telehealth visits, said Rick Gundling, a senior vice president at the Healthcare Financial Management Association, a membership group for health care finance professionals. But lately, “those fees have been coming back,” he said.

Facility fees for telehealth visits in commercial plans averaged $55 for the year that ended June 30, before insurance discounts, according to data from Fair Health, a national independent nonprofit that maintains a large database of insurance claims. In 2020, just 1.1% of commercial telehealth claims included a facility fee, according to Fair Health. That’s lower than for 2019, when the figure was 2.5%.

Experts predict telehealth will remain popular, but it’s unclear how those visits and any accompanying facility fees will be handled in the future.

McCabe said he expects the Yale New Haven Health System to reinstitute the facility fees when state law permits it.

“There are real costs in the health system to provide those services,” he said.

Michelle Andrews is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

andrews.khn@gmail.com, @mandrews110

Llewellyn King: Join the moving revolution in cities

Delivery e-bike with license plate in Manhattan.

Pedicab in Manhattan.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have seen the future of urban life and wasn’t quite what I expected. It was whizzing all around me in New York City on a recent visit.

My wife and I were there to do that most Christmassy of things: see Radio City Music Hall’s “Christmas Spectacular’’ starring the Rockettes. It is great and you should see it if you can, but it isn’t what bowled me over.

What bowled me over figuratively and a couple of times almost literally was the new urban mobility.

I saw the future of city transportation, dashing all around me every time I ventured to cross a street. Like cities the world over, New York has installed bicycle lanes, but they have been taken over by what might be described as Space Age people-movers in astounding configurations.

These denizens of the new mobility hurtled by on electric bicycles, electric unicycles, electric skateboards, electric, gyroscopic one-wheeled skateboards and, of course, those ubiquitous electric scooters. I didn’t think it was the end of civilization as I have known it. Instead, I longed to be a good deal younger so I, too, could join the transportation revolution.

You may not like this new order, and almost certainly if you are over 50, you’re not ready for it. However, it is here, it is happening, and it is the first exciting thing in cities, perhaps since traffic lights.

The future of urban transportation isn’t what supporters of public transit, such as myself, have been advocating for decades: more buses and trains.

City visionaries, like Scott Sellars, city manager of Kyle, Texas, a small but rapidly growing city of 60,000 between Austin and San Antonio, are looking beyond what they call “destination public transportation” to new ways of moving people or, more exactly, new ways of letting people move themselves.

Kyle has made the bold decision that the future of city transportation belongs not to buses and trains, but rather to ride-sharing companies. It has contracted for Uber to become the city’s main public transportation mode. Sellars explained the concept on Digital 360, a Texas State University weekly webinar on which I am a regular panelist.

Sellars told me that Kyle has a subsidized contract with Uber to take care of those unable to afford its fares. Residents qualifying for assistance get a voucher and an app on their cell phones and can make any local journey for a standard $3.14. There are even vouchers for the unbanked. But there isn’t a way yet to use the service if you don’t have a cell phone or access to one.

To avoid having to take lanes away from cars, Kyle has been able to build an alternative system called the Vybe, which is 12 feet wide and can accommodate all people-movers, including golf carts, bicycles and all those electric-powered wheels which are now running around New York. There are charging stations for golf carts and other electric transporters on the Vybe. The Vybe runs most places people might want to go and doubles as a right of way for utilities of all kinds.

While many of us have thought that the smart cities were going to be about super-electric connectivity, few of us realized the first tranche of city smartness would come with new forms of transportation, usurping or challenging the car, bus and train.

The transportation revolution isn’t confined to the surface of cities. Elon Musk’s Boring Company continues to plow ahead with fast, subterranean tunnels, now being implemented in Las Vegas and studied in Los Angeles, Miami, and many other cities.

Look up, too. There is a profusion of companies working on drone-like, urban sky taxis which will whip you from your home to an airport or office tower.

Above the ground, on the ground and under the ground, urban mobility is itself on the move. Hold onto your hat.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island

Web site: whchronicle.com

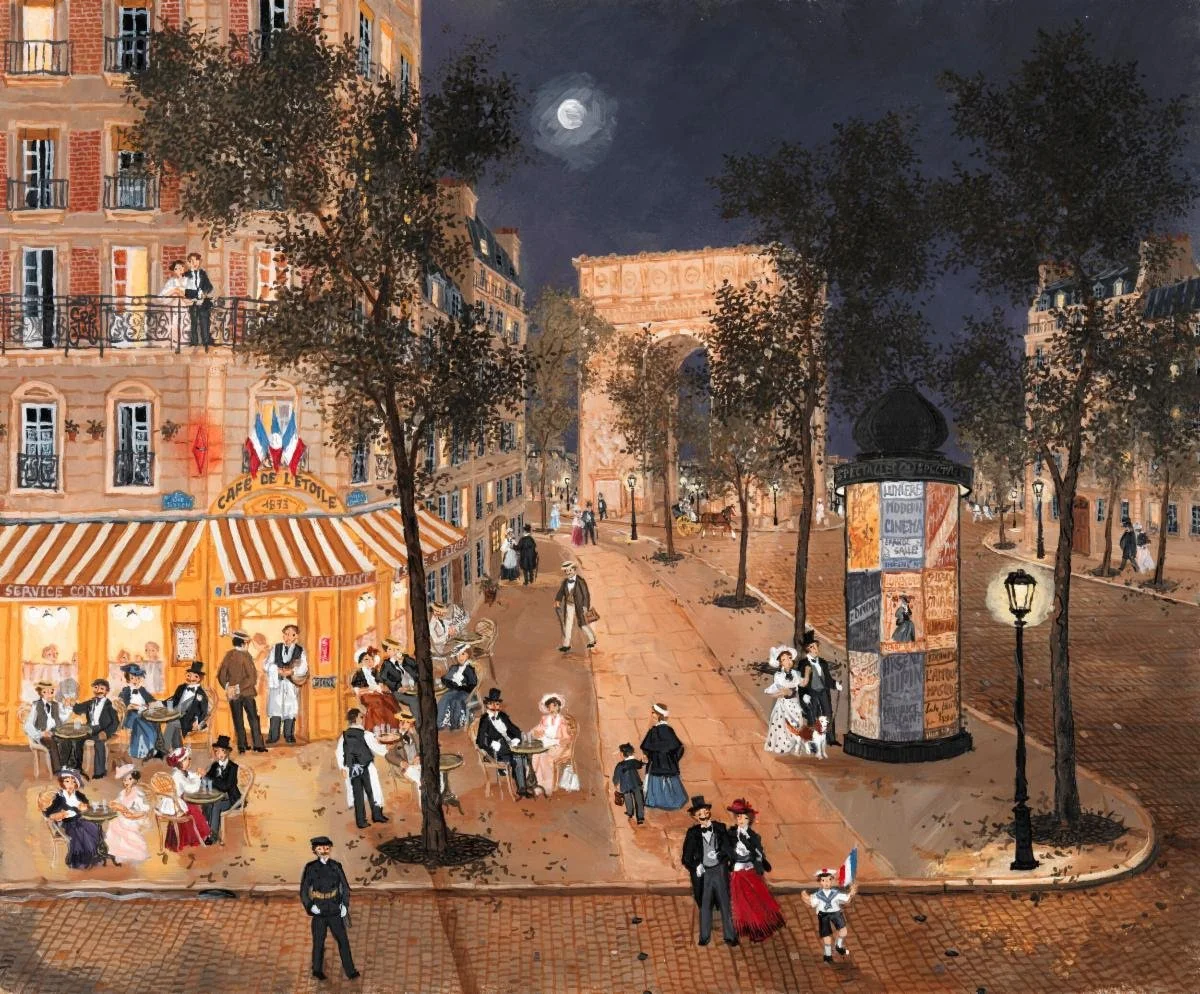

‘An older, simpler’ Paris

“Delacroix Les Biscuits Olibet”, by Fabienne Delacroix, in her show “Fabienne Delacroix: La Belle Epoque, ‘‘ at MFine Arts Gallerie, Boston, through Dec. 30.

Fabienne Delacroix (b. 1972), the youngest child of French painter Michel Delacroix, has been painting since the age of ten.

The gallery says:

"Until recently, Fabienne was known mainly for her seascapes and pastoral landscapes while her father was renowned for his Parisian cityscapes. However, now, Fabienne has expanded her lists of subjects to include the streets of Paris. Like her father’s, Fabienne’s Paris is an older, simpler one with horse-drawn carriages filling the streets."

Don Pesci: JFK Democrats and JFK Republicans fade into history

JFK in 1963

VERNON, Conn.

"Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others"

-- Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898), German chancellor

New England – most conspicuously Connecticut and Massachusetts – has been a school of hard knocks for Republicans who in the past have been liberal on social issues and conservative on fiscal issues. This brand, popular for many years in Connecticut and Massachusetts, has not sold in either state for decades.

The last fiscally conservative, socially liberal congressman in Connecticut was Chris Shays, whose politics was a mirror image of that of Republican Party destructor-elect Lowell Weicker, a maverick U.S. senator for many years whose long run in Congress was cut short by then Connecticut Atty. Gen. Joe Lieberman in the 1988 election.

Wise heads conjectured at the time that Lieberman had bested Weicker because Lieberman was a Democrat who, like Weicker, was socially liberal and fiscally conservative – a Jack Kennedy kind of Democrat. Weicker’s political hero, he often claimed, was New York Sen. Jacob Javits, a Jack Kennedy Republican – certainly not a conservative.

For the past half century, conservatives had been zeroed out in Connecticut, and never mind that William F. Buckley Jr., who had helped reinvigorate conservatism through his magazine, National Review, had been a lifelong resident of Connecticut, a thorn in the side of such as Weicker, a fervent anti-Reaganite. Buckley called Weicker a gasbag. It sometimes seemed that Weicker regarded Ronald Reagan as a far greater threat to the nation than, say, Soviet ally Fidel Castro, the communist maximum leader of Cuba. Reagan referred to Weicker only once in his published diary -- he said Weicker was a “fathead.”

When Weicker lost his Senate seat to Lieberman, few politically awake commentators in Connecticut were surprised. Registered Democrats in the state, then and now, outnumbered Republicans roughly by a two to one margin, a gap that fully explains Weicker’s political overtures to socially liberal Democrats. Weicker’s liberal Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) rating in the Senate during his last years in Congress, was higher than that of liberal Democratic Connecticut Sen. Chris Dodd.

Sensing the whiff of postmodern Democrat progressivism in the wind, a combination of whipped Republicans, fervent Jack Kennedy Democrats, and politically unaffiliated independents, showed Weicker the door and voted for Lieberman.

On the opposite side of the aisle, fiscally conservative, socially liberal Republicans in Connecticut’s congressional delegation, beginning with Nancy Johnson and ending with Shays, were replaced by – how to put this gently? – fiscally progressive, socially progressive Democrats. The political moral of the tawdry tale is -- if you are a Republican pretending to be a Democrat, you will lose to Democrats who have moved sharply to the left.

Jack Kennedy, Bill Buckley, Weicker –and fiscally conservative, socially liberal Republicans -- all have disappeared in puffs of smoke, leaving the political shop in Connecticut to such progressive Democrats as former Gov. Dannel Malloy, state Senate President Martin Looney, and millionaire Gov. Ned Lamont.

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, perhaps the last Jacob Javits Republican in New England {along with Vermont Gov. Phil Scott?} survived for a bit, but now even he has thrown in the towel. Like Vermont, where socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders rules the roost, Massachusetts has gone the way of Connecticut. Republicans, fiscally conservative on economic issues, liberal to moderate on social issues in both states have been vanquished.

The rout in Connecticut, nearly complete, has touched the congressional delegation, all Democrats, the constitutional offices in the state, all Democrats, and the General Assembly, mostly Democrats presided over by postmodern progressives.

The dead branches on New England’s political tree are fiscally conservative, socially moderate Republicans, clipped in the bud for decades by New England academics, hungry postmodern progressives supported by an uncritical media almost wholly in the camp of the victors, and moderate Republicans, a politically unplugged species in Connecticut.

The live branches on the Democrat side of the political barricades just now are postmodern progressives, Gramsci cultists, traditional liberal enemies of the captains of industry, and radical redistributionists flying, knowingly or not, the flag of postmodern Marxism.

These are not Jack Kennedy’s political heirs. The liberalism of Jack Kennedy exists among some forlorn Democrats in the Northeast only as a consummation devoutly to be wished.

On the right in Connecticut, the conservative branch has put forth new buds. Both conservatives and libertarians in Connecticut make no attempts to accommodate their politics to disappearing moderate, fiscally conservative, socially liberal Republican antecedents. That way, they have learned from bitter experience, points to the political grave. These relatively new actors on Connecticut’s political stage are energetic, barely noticed, and tendentiously misunderstood by nostalgic academics and old-time political religionists hoping for a resurrection of a once fructifying liberalism vanquished by postmodern progressivism, which has nothing in common with the liberal prescriptions recommended by Jack Kennedy in an address to The Economic Club of New York a year before he was assassinated.

Just as Weicker may have been the last Jacob Javits Republican in New England, so Jack Kennedy may have been the last classical liberal U.S. president.

You can learn a great deal from history, but you cannot set up house in the past. Those who do so are doomed to irrelevance, because time marches on – usually over the prostrate bodies of those who have, as Otto von Bismarck said, learned from their own mistakes but rendered themselves vulnerable by refusing to learn from the mistakes of others.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Caitlin Faulds: Trying to save a drowning coastal marsh

Wenley Ferguson, of Save the Bay, and many others have spent more than five years trying to save the drowning Sapowet Marsh, in Tiverton. R.I. marsh.

— Photo by Caitlin Faulds/ecoRI News)

Common reed (Phragmites australis) is an invasive species in degraded marshes in the Northeast.

Salt marsh during low tide, mean low tide, high tide and very high tide (spring tide).

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

TIVERTON, R.I.

The grasses are dying. Clusters of broken, denuded stems stand in shallow pools of brackish water, making a patchwork of the low-lying marshlands.

The slow balding is invisible from the blacktop of Seapowet Avenue, hidden behind a thick curtain of phragmites. But standing boot-deep in the peat, surrounded by the sulfuric scent of decomposition, the bare ground is clear evidence of the steady saltwater creep happening in marshes across Rhode Island.

Spartina alterniflora, or smooth cordgrass, is notoriously salt-tolerant and a common feature in saltwater marsh environments.

“They can grow along the edge of the cove and get flooded twice a day, but they can’t grow in standing water,” said Wenley Ferguson, shovel in hand. All around, the sunlight glints off pools of standing water, unable to drain and slowly growing with each high tide.

The average sea level in Rhode Island has increased by about a foot since 1929. Storm surges and king tides have pushed further and further inland. Normally, the marsh would respond to the rising high-water line by matching the migration inland.

But with the sea on one side and a dense web of roads, development, cultivated fields, and invasive species on the other — and accelerated sea-level rise on its way — Sapowet Marsh has nowhere to move.

But Ferguson, the director of habitat restoration at Save The Bay, is working to save the marsh from that saltwater grave.

Ferguson has been working with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) at the Sapowet Marsh Wildlife Management Area, a 260-acre state property, for more than five years now.

The coastal edge of Sapowet has seen more than 90 feet of shoreline erosion in the past 75 years. Under Ferguson’s watch, Sapowet has become home to the largest marsh migration facilitation project in the state — a small counter to the forces at play.

“When I say facilitate marsh migration,” she said, “it’s kind of like prepping the land for the marsh to migrate.”

Back in 2017 and 2018, Save The Bay and DEM, along with the Tiverton Conservation Commission, restored 9 acres of coastal grassland and reestablished beachside dunes on the northern side of the marsh to slow erosion.

Now the work has moved to the west and southeast sides of the marsh — and the strategy has changed to match.

Along the western front

The cordgrass roots are taut, but they cut easy. Just one stomp and the shovel sinks through the muck, water pooling up and over the toes of Ferguson’s black rubber boots.

It was a warm and clear November day — too warm, according to Ferguson. She packed for a cool fall day and wore a blue-flowered fleece, but 60 degrees means she’ll be sweating by midday.

Earlier in the week, Ferguson — along with a handful of DEM employees and volunteers — used shovels and a small excavator to dig a weaving network of runnels through the marsh. These shallow creeks will give the pooling water a route out to Narragansett Bay, allowing the area to slowly drain.

If the root zone of the marsh plants is able to dry even slightly, they will grow “healthy and happy,” Ferguson said. Healthy plants build up a stronger root base, and a stronger root base makes a coastline more resilient to erosion and sea-level rise.

But “we don’t want to drain it too fast,” she said. It has been three days since they dug the first runnels and the water level has dropped only slightly, exposing a few inches of bare mud — exactly as planned.

The standing water is thick with unconsolidated sediments and topped by a bacterial mat. If the water rushes out all at once, this sediment will pour into the bay. It’s better to dig in phases and let it settle out in the marsh, maintaining as much high ground as possible.

They are back on this day to adjust the runnels, excavating the areas where the muck has naturally dammed up. Lucianna Faraone Coccia, a Save The Bay volunteer and an environmental science master’s student at the University of Rhode Island, shovels out a cluster of grass roots.

“If that’s in there, it could plug up this whole runnel,” said Faraone Coccia, glancing down to point out a fiddler crab fumbling its way along the channel with its unbalanced claws.

With each shovel-full, the flow of water grows incrementally stronger and piles of dislodged peat beside the runnels grow larger.

“That’s technically considered fill,” said Ferguson, tossing another glob of peat toward the pile beside her. “We actually leave the peat on the marsh and we create these small little islands.”

These islands are about a chunk of peat thick —some 6-12 inches, not too high, Ferguson said — but that small elevation rise “is like a mountain in a marsh.”

Ferguson fought to keep the peat in the marsh, acquiring additional permits from the Coastal Resources Management Council, DEM’s Office of Water Resources, and the Army Corps of Engineers. This microtopography is essential for a healthy marsh surface, she said.

“These areas will just be a little higher, and they might recolonize,” Ferguson said. “And when I say might — they do recolonize.”

Within one season, the islands will host new sprouts of cordgrass, or they’ll prove high and dry enough to support clusters of high marsh grasses. The clusters of high grass will make ideal nesting habitat for the saltmarsh sparrow.

As healthy salt marsh has waned, so has the population of the saltmarsh sparrow — a bird that makes its nest out of a cup of dense high marsh grasses. The nests are built to withstand the highest moon tides, created with a dome so “the eggs float, but they don’t float out of the nest,” Ferguson said. But the area here is flooding too frequently, contributing to nest failure.

“That’s why these little islands that we’re creating are really valuable habitat,” Ferguson said.

Wenley Ferguson is constantly looking for clues to what shaped the marsh seen today.

Old ways and leftover lines

The state of marshes today are the result of centuries of human development and marshland intervention. According to Ferguson, nearly every marsh in the country holds some sort of historical impact. They are in no way pristine.

“So many of them were manipulated in this area for agricultural activity. And then in more recent years, we put roads along them,” Ferguson said. “We culverted them. We created duck habitat and impounded them. We filled them.”

From the 1700s to the 1900s, about 50 percent of marshes in the region were filled, according to Ferguson. Agricultural embankments have manipulated the marsh surface too, dating back to about the 1600s, when people started haying in these areas.

“The fresher the marsh grasses, the fresher the water table, the greater the value of the hay,” she said.

When she digs these runnels, Ferguson is always scouting for clues to what shaped the marsh seen today. A shovel full of root matter means a stagnant pool was once a field. Water pooling along straight lines could be a sign of an old embankment. Long straight trenches are likely remnants of old mosquito ditches — once made to reduce mosquito breeding grounds but now speeding marshland erosion.

The marsh’s tired past — coupled with its location in an old river valley whose steep sides make marsh migration difficult — spell out a challenging future.

“That’s why what we’re doing today is trying to restore some health of the marsh … under current conditions,” Ferguson said, “but always looking at where the marsh wants to go.”

An excavator heads into a thicket of phragmites growing on the eastern edge of Sapowet Marsh.

The eastern blockade

“Be careful of your eyes walking through this,” said John Veale, habitat biologist with DEM’s Division of Fish and Wildlife, as he pushed away the sharp corners of dozens of broken phragmites. “It can be a little bit dangerous.”

In the past century, invasive phragmites species — few native phragmites remain — have taken advantage of weakened saltwater marsh ecosystems to rampage through North American. The eastern edge of Sapowet Marsh, tucked below Old Main Road and several DEM-owned cornfields, is no different.

In many ways, phragmites are the perfect storm. Their feathery seed heads catch the light beautifully, but they also catch the wind and spread like wildfire. Once the seeds take hold, the reeds grow so densely they all but eliminate animal habitat and outcompete native grasses.

On Sapowet Marsh, it serves as an impenetrable blockade to marsh migration. Only a few grapevines are brave enough to reach their tendrils into the thicket. For the marsh to move away from the encroaching seawater, the phragmites need to loosen their hold. But that’s a notoriously difficult task.

“There’s no way we could do it with a shovel,” Ferguson said. “I mean, it’s just so hard. It’s one thing a little patch of phragmites. It’s another thing when it’s head-high.”

Mowing and burning do little to control phragmites, and pulling them out by the roots quickly proves costly. But like the smooth cordgrass, it is vulnerable to salt water. If Ferguson can drain the pooling fresh water and facilitate tidal flow up into the phragmites, they might dissipate — and the native grasses might have a chance at survival.

“We’re not going to get rid of the phragmites, but we can reduce the height and vigor of the phrag by facilitating that freshwater drainage,” she said.

Ferguson is in the early stages of battle on this front, just figuring out the plan. The phragmites grow 10-12 feet high in places, obscuring the lay of the land.

“There’s enough water,” Ferguson said. “It’s coming from someplace. I just can’t figure out the drainage cause it’s too thick.”

She has called in the help of an excavator. Within a few hours, the machine has established a clearing in the reeds and deepened part of a natural creek. Once some of the standing fresh water drains it will be easier to gauge the direction of the water flow.

Ferguson and her team intend to elongate the creek and the old agricultural ditches — putting past mistakes to better use — but for now the plan is still in development. Better to move slowly than be patching more mistakes up in a hundred years.

“The deterioration along the marsh edge is pretty remarkable, in a terrifying sort of way in my mind,” said Ferguson, pausing to point out a flock of buffleheads skimming into the water. “So that’s why we want to be really cautious on not making new openings for that erosion to expand upon.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.