‘Between energy and calculation’

“ Immanent Arrival’’ (gouache on panel), by Marjorie Kaye, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Jan. 16. She’s a Boston area sculptor and painter.

She says:

”My gouache paintings are built from the observation of complexity and my intention in actualizing sequential order. I need to work as if untying a complicated and seemingly impossible knot. The forms are immediately organic, swirling and undulating from one end of the surface from the other. Once this has been established, I go in honing, working each shape, dissecting it into its unique rhythm. This is the secondary aspect of making each work, and the action that ties the shapes into a whole, one that balances between energy and calculation.’’

‘Great necessities, great virtues’

The Hancock Cemetery, in Quincy, Mass., where President John Adams and his wife, Abigail, and their son President John Quincy Adams and his wife, Louisa, are buried.

“It is not in the still calm of life, or the repose of a pacific station, that great characters are formed. The habits of a vigorous mind are formed in contending with difficulties. Great necessities call out great virtues. When a mind is raised, and animated by scenes that engage the heart, then those qualities which would otherwise lay dormant, wake into life and form the character of the hero and the statesman.”

—From letter of Abigail Adams (1744-1818), wife of Founding Father John Adams (1735-1826), to her son John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), like his father a president.

Phil Galewitz: COVID vaccination rates may be inflated

For nearly a month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s online vaccine tracker has shown that virtually everyone 65 and older in the United States — 99.9% — has received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose.

That would be remarkable — if true.

But health experts and state officials say it’s certainly not. {See comments from experts at Harvard and Yale below.}

They note that the CDC as of Dec. 5 has recorded more seniors at least partly vaccinated — 55.4 million — than there are people in that age group — 54.1 million, according to the latest census data from 2019. The CDC’s vaccination rate for residents 65 and older is also significantly higher than the 89% vaccination rate found in a poll conducted in November by KFF.

Similarly, a YouGov poll, conducted last month for The Economist, found 83% of people 65 and up said they had received at least an initial dose of vaccine.

And the CDC counts 21 states as having almost all their senior residents at least partly vaccinated (99.9%). But several of those states show much lower figures in their vaccine databases, including California, with 86% inoculated, and West Virginia, with nearly 90% as of Dec. 6.

The questionable CDC data on seniors’ vaccination rates illustrates one of the potential problems health experts have flagged about CDC’s covid vaccination data.

Knowing with accuracy what proportion of the population has rolled up sleeves for a covid shot is vital to public health efforts, said Dr. Howard Forman, a professor of public health at the Yale University School of Medicine.

“These numbers matter,” he said, particularly amid efforts to increase the rates of booster doses administered. As of Dec. 5, about 47% of people 65 and older had received a booster shot since the federal government made them available in September.

“I’m not sure how reliable the CDC numbers are,” he said, pointing to the discrepancy between state data and the agency’s 99.9% figure for seniors, which he said can’t be correct.

“You want to know the best data to plan and prepare and know where to put resources in place — particularly in places that are grossly undervaccinated,” Forman said.

Getting an accurate figure on the proportion of residents vaccinated is difficult for several reasons. The CDC and states may be using different population estimates. State data may not account for residents who get vaccinated in a state other than where they live or in clinics located in federal facilities, such as prisons, or those managed by the Veterans Health Administration or Indian Health Service.

CDC officials said the agency may not be able to determine whether a person is receiving a first, second or booster dose if their shots were received in different states or even from providers within the same city or state. This can cause the CDC to overestimate first doses and underestimate booster doses, CDC spokesperson Scott Pauley said.

“There are challenges in linking doses when someone is vaccinated in different jurisdictions or at different providers because of the need to remove personally identifiable information (de-identify) data to protect people’s privacy,” according to a footnote on the CDC’s COVID vaccine data tracker webpage. “This means that, even with the high-quality data CDC receives from jurisdictions and federal entities, there are limits to how CDC can analyze those data.”

On its dashboard, the CDC has capped the percentage of the population that has received vaccine at 99.9%. But Pauley said its figures could be off for multiple reasons, such as the census denominator not including everyone who currently resides in a particular county, like part-time residents, or potential data-reporting errors.

Liz Hamel, vice president and director of public opinion and survey research at KFF, agrees it’s highly unlikely 99.9% of seniors have been vaccinated. She said the differences between CDC vaccination rates and those found in KFF and other polls are significant. “The truth may be somewhere in between,” she said.

Hamel noted the KFF vaccination rates tracked closely with CDC’s figures in the spring and summer but began diverging in fall, just as booster shots became available.

KFF surveys show the percentage of adults at least partly vaccinated changed little from September to November, moving from 72% to 73%. But CDC data shows an increase from 75% in September to 81% in mid-November.

As of Dec. 5, the CDC says, 83.4% of adults were at least partly vaccinated.

William Hanage, an associate professor of epidemiology at Harvard University, said such discrepancies call into question that CDC figure. He said getting an accurate figure on the percentage of seniors vaccinated is important because that age group is most vulnerable to severe consequences of covid, including death.

“It is important to get them right because of the much-talked-about shift from worrying about cases to worrying about severe outcomes like hospitalizations,” Hanage said. “The consequences of cases will increasingly be determined by the proportion of unvaccinated and unboosted, so having a good handle on this is vital for understanding the pandemic.”

For example, CDC data shows New Hampshire leads the country in vaccination rates with about 88% of its total population at least partly vaccinated.

The New Hampshire vaccine dashboard shows 61.1% of residents are at least partly vaccinated, but the state is not counting all people who get their shots in pharmacies due to data collection issues, said Jake Leon, spokesperson for the state Department of Health and Human Services.

In addition, Pennsylvania health officials say they have been working with the CDC to correct vaccination rate figures on the federal Web site. The state is trying to remove duplicate vaccination records to make sure the dose classification is correct — from initial doses through boosters, said Mark O’Neil, spokesperson for the state health department.

As part of the effort, in late November the CDC reduced the percentage of adults in the state who had at least one dose from 98.9% to 94.6%. It also lowered the percentage of seniors who are fully vaccinated from 92.5% to 84%.

However, the CDC has not changed its figure on the proportion of seniors who are partly vaccinated. It remains 99.9%. The CDC dashboard says that 3.1 million seniors in Pennsylvania were at least partly vaccinated as of Dec. 5. The latest census data shows Pennsylvania has 2.4 million people 65 and older.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

Rules of conduct for riding an elevator in a Cambridge, Mass., apartment building.

Throw it all out there

“Hey Mommy!” (watercolor, acrylic, hay, child's toy and staples on Arches paper), by Vermont-based Renee Bouchard, in her show “Allegory of Prudence,’’ at LAArts Gallery, in Lewiston, Maine, through Jan. 14.

The title of the show is a homage to a painting by the great Venetian painter Titian (c 1506-1576) She tells the gallery:

“I am constantly playing with this idea {of high art} by allowing nontraditional materials like natural and human made objects into my paintings. Aiming to transcend the materials, I walk over them to flatten them, staple and glue them on the surface. "

She gives her bio:

“Born in 1976 to French Canadian parents, Bouchard has lived throughout New England for most of her life. She studied at the Cleveland Institute of Art, and graduated from the Maine College of Art in 1999. She received her MFA in visual art from the Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2021, when she was nominated for fellowships from the Dedalus Foundation and the College Art Association. She has received grants, awards, and residencies from institutions including the Maine College of Art, the Vermont Arts Council, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, the Cooper Union, the Kate Millett Art Colony for women, and the Vermont Studio Center.’’

The Kora Temple is an historic Masonic building in Lewiston. It was built in 1908 by the Ancient Arabic Order, Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. “The Shriners’’ are a fraternal organization affiliated with Freemasonry and known for their charitable works, such as the Shriners Hospitals for Children, which provide free medical care to children. The Kora Temple is a ceremonial space and clubhouse for the Shriners. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975 for its distinctive Moorish-inspired architecture.

Lewiston, an old mill town, is best known as home of the prestigious liberal-arts institution Bates College.

James P. Freeman: Will we actually see a predicted generational wealth transfer of $70 trilllion?

"The Young Heir Takes Possession Of The Miser's Effects,’’ from William Hogarth's “A Rake's Progress’’.

One Financial Center and nearby buildings in Boston’s financial district. The city is a national center for investing for retirement.

I was invited recently to an online seminar with this title: “Preparing for the Great Generational Wealth Transfer.”

As a financial professional -- with experience as a private wealth advisor -- I found the subject matter to be particularly intriguing. After all, as a marketer and thought leader today, I look at emerging trends -- behavioral, demographic, and technological, among others -- as a means by which to foster and sustain long-term relationships with clients and prospective clients, alike. All of the looming changes articulated during the webinar (and others I have seen on the horizon) will certainly provide challenges and opportunities in the financial advice business for both the consumer and advisor. But the changes herewith will be seismic.

The webinar presentation was inspired by research conducted by Boston-based Cerulli & Associates, a firm which delivers financial market intelligence to the industry. Cerulli projects that, in the greatest intergenerational reallocation of wealth ever, $70 trillion will be transferred between generations (Silent Gen and Baby Boomers to Gen X and Millennials) by the year 2042. That prediction alone is worthy of our collective attention.

But will that happen? I have my doubts.

Surely, retirement for today’s younger generations will be vastly different from retirement experienced by today’s older generations. But the dollar volume estimated to be passed down seems to me to be fantastically overcooked. Expect the expected. Let me give you my unified field theory.

First, it is important to look at the emerging demographic patterns for a sense of perspective.

Strength in numbers

While the Silent Gen (1928-1945) still plays a role in this “great transfer,” the focus here remains on Baby Boomers. Boomers were born between 1946 and 1964 -- at one point seventy-six million strong. The first Boomer reached the age of 65 -- commonly called “retirement age” -- in early 2011. Today, 10,000 Boomers are turning 65 every single day. Beginning in 2024, however, that figure accelerates to 12,000 per day, in what is being called “Peak 65.” The pace will decline markedly as the last Boomer turns 65 in December 2029. Even more incredibly, sometime during the next decade, one in five Americans will be over the age of 65. That has never happened before.

Gen X members (sometimes referred to as the “MTV Generation”) were born between 1965 and 1980. Today they are between the ages of 41 and 56 and are in the peak earnings years of their careers; the oldest are just starting to contemplate retirement. According to 2019 U.S. census data, they are 65.2 million strong. The oldest Gen Xer has more in common with the youngest Boomer while the youngest Gen Xer has more in common with the oldest Millennial. Arguably, Gen X is a shadow generation given that it is smaller than the Boomer generation preceding it and the Millennial generation following it. And notably, Millennials have eclipsed all other generations for sheer size. So, the attention paid to them is warranted.

Millennials were born between 1981 and 1996. In 2016, Millennials became the largest generation in the U.S. labor force. With 87 million members, Millennials also now represent the largest demographic group in America, surpassing the Boomer generation. In fact, Millennials are the largest adult cohort in the world. Right before their eyes, Boomers are ceasing to be the most influential generation. More than half of Americans are now Millennials or younger, reports brookings.edu

Nonetheless, as the greying of America continues, the median age is now just over 38. Fifty years ago, it was closer to 28 and has been rising ever since.

Adrian Johnstone, president, and co-founder of Practifi, a business management platform for financial advice, was the featured webinar speaker. He delivered examples of the stark contrasts between the generations in how they view the future and view retirement. As you can imagine, there are big cultural differences between these generations. It literally is a generation gap

Understandably, then, Boomers and Millennials have different objectives. At least as understood right now.

Demographics is destiny

Boomers more or less created the financial retirement business. As I like to say it was “of Boomers, by Boomers, and for Boomers.” Not too long ago, a Boomer was likely to measure success in a retirement portfolio by “benchmarking.” For example, this meant comparing the performance of an individual investment portfolio to something like the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, a broad market index that measures performance. It was an accomplishment if you beat a given index in a given year. But defining success has evolved over time.

Smart people began saying this about benchmarking: “So what?”

Retirement planning was more than just investment performance. Industry leaders started looking at planning in a much more holistic way. Soon, business models would build around a “process” to drive success based on “goal setting.” The thinking was that you had a greater probability of achieving your goals if you followed a process. That concept changed the mindset from the short-term to long-term. Indeed, retirement planning was a long-term journey. The rationale was that retirees should consider whether or not they were achieving their goals as the best way to effectively measure progress in retirement. “Goals” was a much broader concept than “benchmarks,” yet it was much more focused, too -- buying a second home, taking annual vacations, investing in long-term care, setting up gifting, losing weight, etc. Markets go up and go down. But if you could achieve your overall goals despite inevitable market turbulence that was the new paradigm for defining success in retirement.

My sense, however, is that this current model is beginning to change as well. While goals will always be part of retirement planning, I question if setting lofty, long-term goals (even if practical) may prove to be elusive for many retirees going forward. My reasoning is straightforward.

The youngest Boomer and oldest Gen X have had to weather three once-in-a-lifetime events that affected retirement planning and saving in just the last twenty years. (Dotcom in 2000, Great Recession in 2009, COVID-19 in 2020). Combine these events with future funding issues for Social Security, Medicare, and Long-Term Care needs, it paints a less certain financial picture. Throw in the fact that this demographic carve-out is more in debt than older retirees and the relative financial future seems even less assured for them. Goals, then, seem illusory.

Given these realities, I believe that financial planning will once again morph into a new realm. Discussions will center more on “lifestyle” (or standard of living) and less on goal setting. Maintaining -- if not improving -- one’s lifestyles is a more focused conversation than goals; it’s much more tangible than goals, too. Telling clients they will not be able to maintain a given lifestyle is much more powerful than telling them they can not reach a goal.

So, in the span of fewer than forty years, you can see the progression of retirement planning models in how performance is often measured. It began with comparing benchmarks to setting goals and will likely shift even more to living desired lifestyles. Enter Millennials…

Now please fasten your seatbelts before departure

The Practifi webinar suggested even more pronounced changes when Millennials begin serious retirement consideration. According to Johnstone, this generation will be mostly concerned about values -- such as social responsibility and the impact of their decisions on the larger society. In other words, for them, retirement planning must center around their values, with everything else, including, presumably, performance, of less or equal import.

That is a radical shift in priorities.

Additionally, financial advisors should anticipate other changes in how future generations approach retirement. They are just as compelling.

The retirement landscape will probably look unrecognizable after the last Boomer retires in 2029, presenting new complexities for all interested parties.

Surely, there will be a transfer of wealth (more about which anon) and advisors will need to be aligned with the interests of the next generation (values more than goals). Likewise, “NextGen” retirees will have crypto currencies and ESG investments (environment, social, and governance) as staples in their portfolios. They will also be more inclined to make micro loans, a newfangled investment alternative. Fee structures will undoubtedly be altered. Marketing will be impacted by implementing AR (augmented reality) into social media and other platforms. The regulatory apparatus will also look hugely different. And AI (artificial intelligence) software tools will complement human advisors. Finally, future retirees will be more financially literate, more skeptical, and more engaged (via technology) about, well, everything.

Advisors in the future doubtless must change from a Boomer-centric retirement model to a Millennial-centric retirement model not only to accommodate the next retirement class but to prepare for the predicted wealth transfer. For Johnstone, he sees a sea-change from the client point of view, too. He believes that Boomers are “delegators” of their retirement (to advisors). Whereas Millennials will be “validators” of their retirement (from advisors).

Show me the money!

Notwithstanding the extraordinary metamorphosis about to play out in a couple of years in terms of demographics and service delivery models, the real question is about assets. This past June, The Wall Street Journal reported that the great transfer has already begun. It cited Federal Reserve data indicating that Americans over the age of 70 had already accumulated “a net worth of nearly $35 trillion.” That amounts to 27 percent of all U.S. wealth, up from 20 percent three decades ago.

Still, I am not entirely convinced that $70 trillion in assets will ultimately be transferred to heirs and charities, as predicted. That stockpile of money seems high. To better understand that dollar amount, it would mean the transference of roughly $3.3 trillion every year for the next twenty years. Put another way, the total would be the combination of President Biden’s $1.9 trillion Build Back Better Act and $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Acts, annually, up to 2042.

Labyrinthine financial trends might well offset the amount substantially.

The real question should be: Will known (and unknown) massive unfunded liabilities eventually absorb much of the $70 trillion because we have simply failed to live within our means today? We have shifted many of today’s financial burdens on younger generations and even generations not yet born. The arithmetic just doesn’t square.

Conceivably, much of these assets would be liquidated -- and hence evaporated -- prior to any transferring or gifting because of future costs. Consider the following four factors: poor savings, rising healthcare costs, Social Security funding concerns, and high personal (not to mention high institutional and governmental) debt loads. It is the liabilities side of the balance sheet that concerns me. Not the assets side.

Something has gotta give

POOR SAVINGS

Despite a staggering amount of cash flooding into the American economy as part of COVID-19 relief (read about the $5.2 trillion in pandemic fiscal stimulus), not to mention an absurdly accommodative monetary policy, America still has a savings problem. (Remember food lines queuing up just a couple of weeks after the first lockdowns in early 2020? We were told people did not have money saved for such “emergencies.”) I don’t subscribe to the idea -- as perpetuated by economists, usually the last group of people “in-the-know” -- that Americans have significantly improved their savings rates. Saving is a behavioral attribute. Have behaviors really changed for the long term? Any built up savings is likely a temporary phenomenon. I write that because much of the chatter we hear from financial commentators centers on all this “pent up demand” stemming from the pandemic. Such demand, we are told, is exacerbating the supply-chain problems. A probable outcome will be all the extra cash will be spent.

Earlier this year the Insured Retirement Institute released the results of a survey conducted on workers between the ages of 40 and 73. Its findings were unsurprising but consistent with many similar studies on worker preparedness for retirement. Two key takeaways were as follows: savings behavior needs to improve, and retirement income expectations are unrealistic. The survey found that 51 percent of respondents had less than $50,000 saved for retirement. Furthermore, the report concluded that “Among savers, savings rates are not nearly high enough for even the youngest respondents to grow their nest eggs to a level sufficient for meeting their income and budget expectations.” The survey was conducted after much of the stimulus was already distributed into personal and small business accounts.

And, perhaps most alarming, the institute wrote that, across several measures of retirement preparedness, “most [respondents] fear they will not have enough income, will not be prepared to transition into retirement, will not have enough money for medical expenses or long-term care should the need arise, and may not be able to live independently for the entirety of their retirement.” A large number of Americans are not putting enough aside to catch up.

Americans’ use of retirement plans has changed dramatically over the last several decades, too. In the past, good-ole-fashion “defined benefit plans” (think pensions) were the norm. They were a stable retirement income source for millions of retirees. But many pension plans -- especially in the public sector -- are grossly underfunded today. The 401(k) was born in 1978 and known as a “defined contribution plan.” Such contribution plans were devised to supplement benefit plans but over time they ended up supplanting those benefit plans. And at their root, 401(k) plans were really DIY plans -- or “do-it-yourself” plans. The result was that the American worker became the principal source of his or her retirement savings, not a corporation or municipality. And the data confirm that Americans are not contributing enough to these plans. Therefore, it is hard to see where additional savings are built into future retirement portfolios -- unless people rely mostly upon enormous equity gains in real estate holdings. Besides, government policy discourages saving (with artificially and historically low interest rates) and encourages speculating (with greater yields in riskier market investments). This is even more outrageous considering higher inflation has returned with gusto.

As 2021 ends, I would imagine that future studies examining the impacts of all this stimulus will confirm that the notion of any substantive increase in savings and savings rates is a grand chimera.

RISING HEALTHCARE COSTS

Nearly ten years ago, in a 2012 speech at the U.S. Naval War College, conservative columnist George Will, then 69, showed those in the audience his Medicare Card. He had also previously shown it to his doctor. To which his doctor said, “That’s wonderful, George, we’ll send your bills to your children.”

Both “Romneycare” (in Massachusetts) and “Obamacare” (at the national level) largely fulfilled their aims of insuring many more of its residents and citizens, respectively, for healthcare. However, neither program did anything to bend the cost curve. In Massachusetts, for instance, healthcare costs now represent 36 percent of total state spending. It was 31.5 percent just three years ago. For fiscal 2008, the figure was approximately 30 percent.

In case you missed it, healthcare costs have been rising and will continue rising, yet few want to pay for spiraling costs. According to healthsystemtracker.org, health spending in America totaled $74.1 billion in 1970. Three decades later, by 2000, health expenditures reached about $1.4 trillion. Put another way, “In 1970, 6.9 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the U.S. was spent toward total health spending (both through public and private funds). By 2019, the amount spent on healthcare has increased to 17.7 percent of the GDP.” It is expected that the number will reach 18 percent soon.

Healthcare costs in this country continue to accelerate because of the intersection of demographics (Boomers retiring in large numbers) and better medicine (diagnostic, therapeutic, pharmacologic). Today, we are consuming $3.8 trillion or $11,582 per person, annually, on healthcare. This is nearly three times what was spent only twenty years ago. And with more Boomers consuming even more healthcare in the future, our healthcare system will strain with greater costs. Spending will sharply hasten.

Data in a 2021 extract provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation reveal that American households paid, on average in 2018, 18.5 percent of their income towards healthcare costs. In addition, “According to Medicare beneficiaries’ data, in 2017, the average total health expenditures in their last year of life was $66,176.”

Medicare currently covers nearly 64 million Americans today. And funding for the program accounted for more than 4 percent of the U.S. GDP in 2020, reports medicareresources.org. Total Medicare spending stood at $917 billion last year, and it is expected to grow to $1.78 trillion in 2031, or two years after the last Boomer retires.

Medicare, established in 1965 as part of The Great Society, has critical funding challenges just like Social Security -- but they are more immediate. It is estimated that the Medicare Trust Fund will be exhausted in 2024 unless Congress acts to implement new reforms. Barring no changes, the Congressional Budget Office projects that following 2024 exhaustion, Medicare will only have sufficient tax receipts to be able to pay 83 cents for every dollar covered. There are three practical solutions to avoid insolvency, concluded forbes.com this past March: “Increase revenues flowing into the trust fund by at least $700 billion to extend solvency to 2036 (experts typically focus on 10-year time horizons); cut spending on Medicare beneficiaries or increase their monthly premiums; or figure out a combination of these two methods.”

All of these challenges were known as far back as twenty years ago. In 2002, Health Services Research issued a study named “The 2030 Problem: Caring for aging Baby Boomers.” Few have paid heed to the warnings that it issued back then. “To meet the long-term care needs of Baby Boomers,” its authors wrote, “social and public policy changes must begin soon.” In 2021, it is obvious that these changes never occurred.\

SOCIAL SECURITY FUNDING

In many respects, healthcare cost concerns are a bigger worry than Social Security because the latter is more manageable and knowable: We have decades of economic data and demographic data to ascertain future costs. We know healthcare costs will rise but it is such a wildcard that it is difficult to enumerate actuarial costs. With Social Security the math is right in front of us, and it is largely predictable. But reforms are needed.

According to the Social Security Administration, the ratio of covered workers to beneficiaries was 159 to 1 in 1940; that figure shrank to 2.8 to 1 in 2013. It is estimated to be 2.7 today. However, when the last Boomers reach age 75, the trustees of the program project that “the ratio will fall to 2.2 to 1 in 2039.”

And unless, in this politically charged environment, changes are made to how Social Security is funded, it will not support paying out 100 percent of benefits beginning in 2034. Barring no change, payroll taxes will only then be able to distribute approximately 75 percent of promised payments. Like Medicare, it would seem that a combination of higher taxes and lower payouts would be the most likely outcome. But that is impossible to predict.

Estimates vary on how much retirees rely entirely on Social Security as a source of income in later years.

The National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS) in January 2020 reported that, “A plurality of older Americans, 40.2 percent, only receive income from Social Security in retirement.” That analysis was called into question by Andrew G. Biggs, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Biggs has written extensively on retirement matters. Using different data points collected by other governmental agencies, he found there is not a consensus on the NIRS thesis. Instead, there is evidence that between 12 percent and 20 percent of older Americans rely solely on Social Security for support. Even if those figures are closer to reality, it is a fact that millions of retirees depend on Social Security as a significant source of income. So, this question remains pertinent: What would a potential 25 percent reduction in Social Security benefits do to seniors?

Arguably, in order to finance the current level of Medicare and Social Security benefits for future retirees (will there ever be higher levels of spend?), higher payroll taxes would seemingly be the quickest fix. And it is not too farfetched to reason that inheritance taxes would also rise to address these systemic problems, too. These measures would certainly eat into the great transfer of $70 trillion.

IN DEBT WE TRUST

My favorite website may be debt.org.

The site is really an advocacy platform that wishes to help people who are in debt, but I find it as a reliable financial resource. Its “Demographics of Debt” page is a helpful amalgam of disparate data points that exposes a crisis like an asteroid approaching earth. Recent updates to the page have included debt tabulations made during the pandemic.

American household debt hit a record $14.6 trillion in the spring of 2021, according to the Federal Reserve. (Housing likely accounts for 71 percent of that total.) Furthermore, last year, rather disturbingly, “The total U.S. consumer debt balance grew $800 billion, according to Experian. That was an increase of 6 percent over 2019, the highest annual growth jump in over a decade.” Borrowers have been the beneficiaries of historically low interest rates for over a decade now. This has, in my opinion, been an inducement to borrow more without consequences. But with higher inflation now center stage for an economy that has experienced benign inflation for decades, it would seem that the Federal Reserve would be poised to raise interest rates sooner than later. Such action would make it more expensive to borrow and would obviously make servicing debt more expensive, especially for adjustable-rate debt instruments. (Interestingly, Adjustable Rate Mortgages make up just 3.4 percent of all mortgage applications today; as of 2020, approximately 44 percent of U.S. consumers have a mortgage; in Massachusetts the average individual mortgage balance is $261,345, as of 2020.)

I am keenly interested in the breakdown of debts among the demographic groups. The anticipated great transfer of wealth would imply that older generations (Silent Gen and Boomers) would be relatively unencumbered by debts to allow them to freely pass along assets to heirs (Gen X and Millennials) and charities. On the contrary, the data suggest that picture less clear.

Of these four demographic groups, the Silent Gen has the lowest amount of average debt per member ($41,281), while Millennials have the third lowest ($87,448). What is somewhat surprising is that Boomers place second, having an average of $97,290 of debt per member. Meanwhile, Gen X can claim the largest debt burdens for this comparison with an average of $140,643 per Xer. Academically, this all makes sense as Gen X is still paying off the bulk of its mortgage obligations and the same may be said for the youngest Boomer as well.

It seems to me, that despite the fact that Boomers are no longer the largest demographic cluster, they will largely determine whether or not the great transfer of assets actually happens.

I do not see how the bulk of $70 trillion ever gets delivered to younger generations. I believe that future costs (for healthcare, Medicare, and Social Security) will emphatically eat up much of those assets. Boomers will inevitably be more “takers” than “makers” of the great transfer. Finally, I believe that servicing existing individual debt loads will be as much of a factor in the future as it is today. We also should be mindful of the exorbitant levels of debt at the government and institutional levels that will also need adequate funding. Time was when we borrowed for the future. We now borrow from the future. There is no escape from The Great Debt.

Years ago, I did a short stint as a substitute teacher. I would argue that the elementary classroom is a more challenging environment than the Wall Street boardroom, and higher learning more perspicacious than higher returns. One fine day I was teaching first graders. There was some free time before dismissal, so I simply asked them to draw anything they wanted -- a token for the ride home after school. It was a fun exercise. As I was circulating around the children, watching future Picassos toil away, I came across a young girl named Sally. I couldn’t quite figure out what she was sketching. So, I asked, “Sally, what is that?” She paused, and with steely determination, she said, “I am drawing a picture of God.” I made the mistake of responding, “Well, Sally that’s quite something because no one knows what God looks like.” To which she retorted, with breezy confidence: “They will in a minute.”

With regard to the great wealth transfer and attendant ramifications, we will see in a New York minute.

James P. Freeman is the director of marketing at Kelly Financial Services, LLC, based in in Greater Boston. For much of his professional career in financial services he was an officer in the bond administration departments of a number of banks and trust companies. This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase any interest in any investment vehicles managed by Kelly Financial Services, LLC, its subsidiaries, and affiliates. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not accept any responsibility or liability arising from the use of this communication. No representation is being made that the information presented is accurate, current, or complete, and such information is at all times subject to change without notice. The opinions expressed in this content and or any attachments are those of the author and not necessarily those of Kelly Financial Services, LLC. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not provide legal, accounting or tax advice and each person should seek independent legal, accounting and tax advice regarding the matters discussed in this article.

Things are scary but calm down

“Coming Undone” (drawing on cradled board, encaustic, pigment stick), by Nancy Spears Whitcomb

Find another place, please

Sunrise in Cape Elizabeth

— Photo by Erin McDaniel (Erinmcd)

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Rhode Island Gov. Dan McKee’s administration has just approved spending nearly $31 million in state funds for 23 affordable-housing projects, for a total of 600 units in 13 cities and towns. Sounds nice, but I wonder how this will play out in certain localities, some of which have many poor people and some with quite a few wealthy ones.

It's often close to impossible to put affordable housing in an affluent town. For example, I just came across a Portland Press Herald story of how foes of a project called Dunham Court, in toney Cape Elizabeth, Maine, have killed the project, which was to include a 46-unit apartment building near Cape Elizabeth’s town hall and within walking distance of a supermarket, pharmacy, public schools, community center, police and fire station and the Thomas Memorial Library. The proximity to these services would have decreased the need for the low-income renters to take on the expense of cars. Oh, well.

Affordable housing is scarce in Greater Portland, as it is in many places. Well-off people don’t want poorer people near them. This is part of the reason for “snob zoning,’’ which includes such things as high minimum acreage requirements. Of course, this limits the construction of new housing, which raises prices and makes housing even less affordable for moderate and low-income people.

To read about the Rhode Island plan, please hit this link.

To read about the Dunham Court collapse, please hit this link.

Don't look over the railings

“Between the Lines” (limited edition photo print on anodized aluminum), by Kathleen McCarthy at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

‘Too immense’

— Photo by Overberg

“The night was too immense for any lantern,

Yet one was coming swinging down the road,

And someone’s frosty breath was hung above it

And looked like dust of stars as someone strode.’

— From “The Cry,’’ by Robert P. Tristram Coffin (1892-1955), a Maine-based, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet (and an historian)

‘Pure, blank sheet’

Administration Building at McLean Hospital

— Photo by John Phelan

“A fresh fall of snow blanketed the asylum grounds — not a Christmas sprinkle, but a man-high January deluge, the sort that snuffs out schools and offices and churches, and leaves, for a day or more, a pure, blank sheet in place of memo pads, date books and calendars.’’

From autobiographical novel The Bell Jar, by Sylvia Plath (1932-1963). She was depressed most of her life and killed herself. The “asylum’’ she refers to is probably McLean Hospital, in Belmont, Mass.

Climb every body

“Enochian Landscape” (oil on canvas), by James Cole, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Jan. 16

Can't hear the forest for the trees?

“Adventures in Echolocations: Somnambulist,’’ by Serena Perrone, at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence.

Buckland State Forest entrance, in Buckland, in western Massachusetts

Caitlin Faulds: Trying to keep climate change from turning more toxic at N.E. waste sites

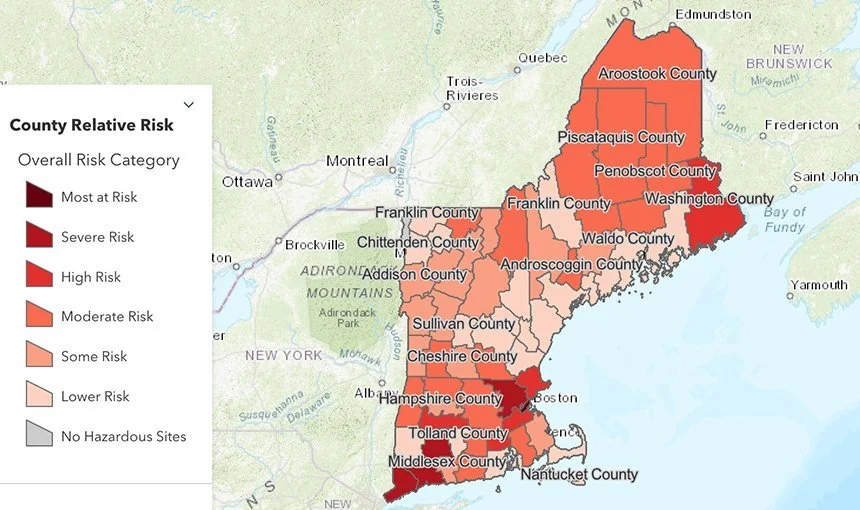

Providence County, in Rhode Island, and Suffolk County, in Massachusetts, are two of the most at-risk counties in New England from pollution buried at toxic sites.

— Conservation Law Foundation map

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Hazardous-waste sites and chemical facilities pockmark New England, leftovers of the region’s industrial past. And little action is being taken to prevent climate change from affecting these sites and cooking up a toxic future, according to analysts at the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF).

A regional report by CLF Massachusetts released this fall combined projections of climate risk with data on social vulnerability and hazardous- waste sites to build a comprehensive map of anticipated toxic-pollution risk from Connecticut to Maine. The results, which show that much of New England could face compounding threats, are startling — even to the mapmakers.

“I bought a house like six months ago … and was actually surprised by the number ... of [Superfund] sites that are in such close proximity to residential neighborhoods,” said Deanna Moran, CLF Massachusetts director of environmental planning. “It’s a little bit scary, but it’s a healthy amount of fear.”

In Rhode Island, Providence County was determined to be the county at highest risk, due to a combination of moderate wildfire risk, severe heat risk, high social vulnerability and 143 hazardous sites. Massachusetts’ s Suffolk County, which includes Boston, was deemed most at-risk in New England.

“A lot of people don’t realize how ubiquitous hazardous sites are, even Superfund sites are, throughout our region,” Moran said. “Even if a site is under remediation or fully remediated, those are the sites that we are still worried about because they were remediated without climate change at the forefront.”

The county-level analysis factors in risk associated with nearly 3,000 hazardous sites. These New England locations include landfills, Superfund sites, brownfields and 1,947 facilities across the region that generate large quantities of hazardous waste or are permitted for the treatment, storage or disposal of toxic chemicals. Many of these hazardous sites are aging, use failing technology, and/or do not have sufficient safeties in place to protect nearby communities in a warmer world, according to the CLF report.

“The techniques that we used to remediate those sites 20 years ago might not anticipate more extreme precipitation or flooding or heat,” Moran said, “and those are the ones that I think are really concerning ’cause they’re really not on the radar.”

Floods could damage infrastructure containing hazardous waste, trigger chemical fires, hinder technology monitoring toxic pollution, and create a toxic stew of floodwater and contaminants, according to the report. Rising temperatures could damage protective caps over contaminated properties and raise the toxicity level of some materials. Wildfires could ravage hazardous-waste sites, damaging protective infrastructure and releasing airborne contaminants.

The lineup of climate risks — which, according to CLF Massachusetts policy analyst Ali Hiple, were “weighted equally” in the report — paints a bleak scene of the region’s future, a future that has been glimpsed in isolated events across the country in recent years.

“Luckily, we have not seen that type of impact in the New England region yet, but we want to make sure that we’re being proactive now and not reactive later,” Moran said.

But despite knowing the dangers that climate poses, federal agencies “are not doing enough to address them, and that puts our communities in danger,” according to the CLF report. In 2019, a U.S. Government Accountability Office report suggested the Environmental Protection Agency should consider climate to ensure long-term Superfund site remediation and protection plans.

“We really just want to see the EPA really leading on this,” said Saranna Soroka, a legal fellow at CLF Massachusetts. “They’ve indicated they know the risk that climate change poses to these sites … but we want to see really consistent, really clear standards applied.”

Soroka noted that the federal agency could analyze climate impact as part of its existing Superfund-site review framework, which mandates site checks every five years. So far, climate analyses have not been incorporated, she said, despite EPA authority to do so.

“I think we’re well beyond the time of thinking through how we should be doing this,” Moran said. “We know the risks are real. In some cases, we’re already seeing them, and the time to be acting on them is now.”

Editor’s note: Here are links to EPA-designated Superfund sites in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Warren Getler: This most uncertain winter

Luce Hall (1884) at the U.S. Naval War College, in Newport, R.I. The institution is a center of the U.S. military’s war-gaming work.

—U.S. Navy photo by Jaima Fogg

Ukrainian troops in the threatened country’s Donbas region. Russia has been massively increasing its troop strength nearby in what some observers fear is a precursor to an all-out invasion.

America faces its most challenging year-end since its formal entry into the Second World War, in December 1941.

While we have been internally grappling with COVID for nearly two years, dark clouds have gathered on the geopolitical map.

Russia is mobilizing some 175,000 troops on its border with Ukraine; China is flying repeated bomber test-runs near Taiwan; Iran is using its proxies to hit its Arab neighbors as well as Israel and U.S. bases in Iraq and Syria with drones and missiles. Russia and China are exhibiting their closest military collaboration – in joint-training exercises and bilateral arms sales – in decades. And both have signed military and economic pacts with Iran in recent years.

Will there be war, indeed, continental war, on several fronts?

The risk may be greater than at any time since World War II.

Authoritarian rulers-for-life in Moscow and in Beijing are testing the waters. Specifically, they are testing the mettle of U.S. President Joe Biden and his first-year administration. They’re gauging a Biden preoccupied with internal debates around vaccination policies, inflation, crime, supply-chain bottlenecks and other largely domestic, massively time-consuming matters.

And they perceive vulnerability in the Oval Office – with Biden, who just turned 79, coming off a grueling multi-year presidential campaign against incumbent Donald Trump and then seeing his approval ratings drop for months. What’s more, they sense a country deeply divided -- an American superpower at growing risk of civil unrest.

Are these Russian and Chinese military maneuvers mere provocations, mere signals of what could happen if the West challenges their geopolitical ambitions?

Or are these up-tempo deployments by Russia’s Putin and China’s Xi meant merely for domestic Russian and Chinese consumption? Possibly not.

This time, the activity around such large-scale mobilizations appears alarmingly furtive, and therefore open to wide interpretation, particularly regarding Moscow’s intentions toward Ukraine. These maneuvers (including rumors of a planned assault on eastern Ukraine in late January or early February) may invite retaliation and potential “miscalculations” by both sides. Putin and Xi may not appreciate the seriousness of possible "kinetic" responses by NATO allies and our friends in Asia. Israel, meanwhile, uncertain of backing from Washington, is leaning toward taking things into its own hands to stop -- with direct military action from the air -- a nuclear-armed Iran from emerging.

America, as the world’s leading democracy, is slow to anger, which is a good thing. Yet we are also at times too slow in confronting harsh realities beyond our borders. As a nation, we must focus on the large-scale threat scenarios developing in Europe, East Asia and the Middle East…with level-headed coolness and a serious, sustained focus.

John F. Kennedy, in his Harvard thesis-turned book, Why England Slept, pointed out the danger of Britain ignoring for too long Nazi Germany’s growing war machine and the bellicosity of its totalitarian dictator, Adolf Hitler.

“We can't escape the fact that democracy in America, like democracy in England, has been asleep at the switch. If we had not been surrounded by oceans three and five thousand miles wide, we ourselves might be caving in at some Munich of the Western World,” writes Kennedy, the then 22-year-old future president of the United States.

“To say that democracy has been awakened by the events of the last few weeks is not enough. Any person will awaken when the house is burning down. What we need is an armed guard that will wake up when the fire first starts, or, better yet, one that will not permit a fire to start at all. We should profit by the lesson of England and make our democracy work. We must make it work right now. Any system of government will work when everything is going well. It's the system that functions in the pinches that survives.”

To prevent tipping into something recalling the 1939-45 cataclysm, we must show resolve – an unquestioned firmness that lets our real and potential adversaries know that we stand united -- at home and with our key allies abroad. Such resolve deters dangerous opportunism among our foes, setting up a bulwark against a lurch into regional war, indeed, into seemingly unthinkable inter-continental war below the nuclear threshold.

We must recognize that both China and Russia have been developing advanced missile systems – notably conventional-use hypersonic weapons – that could put us at risk in the same manner (or more at risk) as the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Back then, at least, we could surge into a mass production of armaments as never-before seen; today, given supply-chain restrictions and other factors, such an achievement would perhaps be less certain after any potentially devastating attack on our military bases, ports and other critical infrastructure.

Lest we forget, while Britain slept in those years before the outbreak of WWII, Germany was able to secretly develop its , first-of-their-kind V-2 rockets that would eventually rain down on London and cause widespread damage and terror. Today, Pentagon chiefs are repeatedly sounding the alarm about the yawning gap in U.S. vs. Chinese/Russian advanced hypersonic-missile capabilities, not to mention recently demonstrated Russian capabilities of destroying satellites in orbit with missiles fired from its territory.

To its credit, the Biden administration is slowly but surely turning its strategic military assessments and its inner-circle Pentagon planning toward our China challenge, thus pivoting away from the “forever wars” of Afghanistan, Iraq and, going further back, Vietnam. And, just last week, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken had this to say about the massive Russian troop buildup, including more than 1,000 tanks, on the border of Ukraine. “We don’t know whether President Putin has made the decision to invade. We do know that he’s putting in place the capacity to do so in short order should he so decide.”

As we approach the 80th anniversary of Pearl Harbor this week -- not to mention the 250th anniversary as a nation in less than five years -- America cannot afford to be ill-prepared for tectonic convulsions on the geopolitical landscape. We can not, as a society, spend too much time navel-gazing or being preoccupied with the likes of the latest crazes on Instagram, Tik-Tok or the Metaverse.

These times demand extraordinary leadership, no matter the internal challenges and pre-occupations of the world’s greatest democracy. As Americans, we will be roundly tested during this most uncertain winter -- and not merely by inflationary pressures or a new surge of the Delta and Omicron COVID-19 variants, which are eroding the fabric of civil society both here and abroad.

Warren Getler, based in Washington, D.C., writes on international affairs. He’s a former journalist with Foreign Affairs Magazine, International Herald Tribune, The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg News. His two sons serve in the U.S. military.

Hands across the sea

Our friend Bill Perna, who grew up in Greenwich, was very surprised to come across this sign while driving into the town of Rose in Italy’s Calabria region.

— Bill Perna

Taiwan scares Beijing

The flag of the Republic of China, Taiwan’s official name.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com.

Good for the Biden administration for inviting Taiwan to the "Summit for Democracy" it has organized for Dec. 9-10, angering, of course, the Chinese dictatorship, which hates having the island democracy as a model that might tempt the dictatorship’s subjects in Mainland China. Bejing claims ownership of Taiwan.

But no, Taiwan has not “always been part of China,’’ contrary to Mainland claims. Hit this link for some history.

The summit is part of Biden’s effort to pull together the world’s democracies and semi-democracies (the latter including the U.S., where democracy is under siege by rising fascism) to push back against increasing aggression by autocracies led by China and Russia after the damage done by dictator-suck-up Donald Trump.

Taiwan, by the way, has many business investments in New England, especially in high technology, and vice versa, as well as many cultural activities. And since 1996, Taipei, the Taiwanese capital, has been a sister city of Boston.

Hit this link for more information.

Only six months to go

Union Square Farmers' Market (watercolor), by Seth Berkowitz, at Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., in the show “Somerville as Muse,” Dec. 9-Jan. 15

Circling makes sense

Rotary sign at a Lowell, Mass., traffic circle. Note the ‘Yield’’ sign.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

like too many other commentators on the $1.1 trillion physical-infrastructure law, have too often failed to note three very important things about, in addition, most famously, to the transportation-related stuff: It would help improve water-supply systems, which are dangerously corroded and outdated in many places and strengthen the electric grid and Internet, including their security, which are all too vulnerable to attacks by the Russians, Chinese, North Koreans and other enemies as well as those extortionists just in it for the money.

We need fewer road intersections with lights and more traffic circles, with landscaping in the middle. The latter have fewer accidents, in part because they slow down drivers where they should be slowed down.\

The Federal Highway Administration reports that traffic circles reduce injury and fatal crashes by 78-82 percent compared to conventional intersections. A typical intersection has 32 conflict points, compared to only 8 at a roundabout.

And, as I discovered last week driving up Route 10 in New Hampshire, they can be quite attractive.

Something for states and localities to consider when it comes to spending federal infrastructure money.

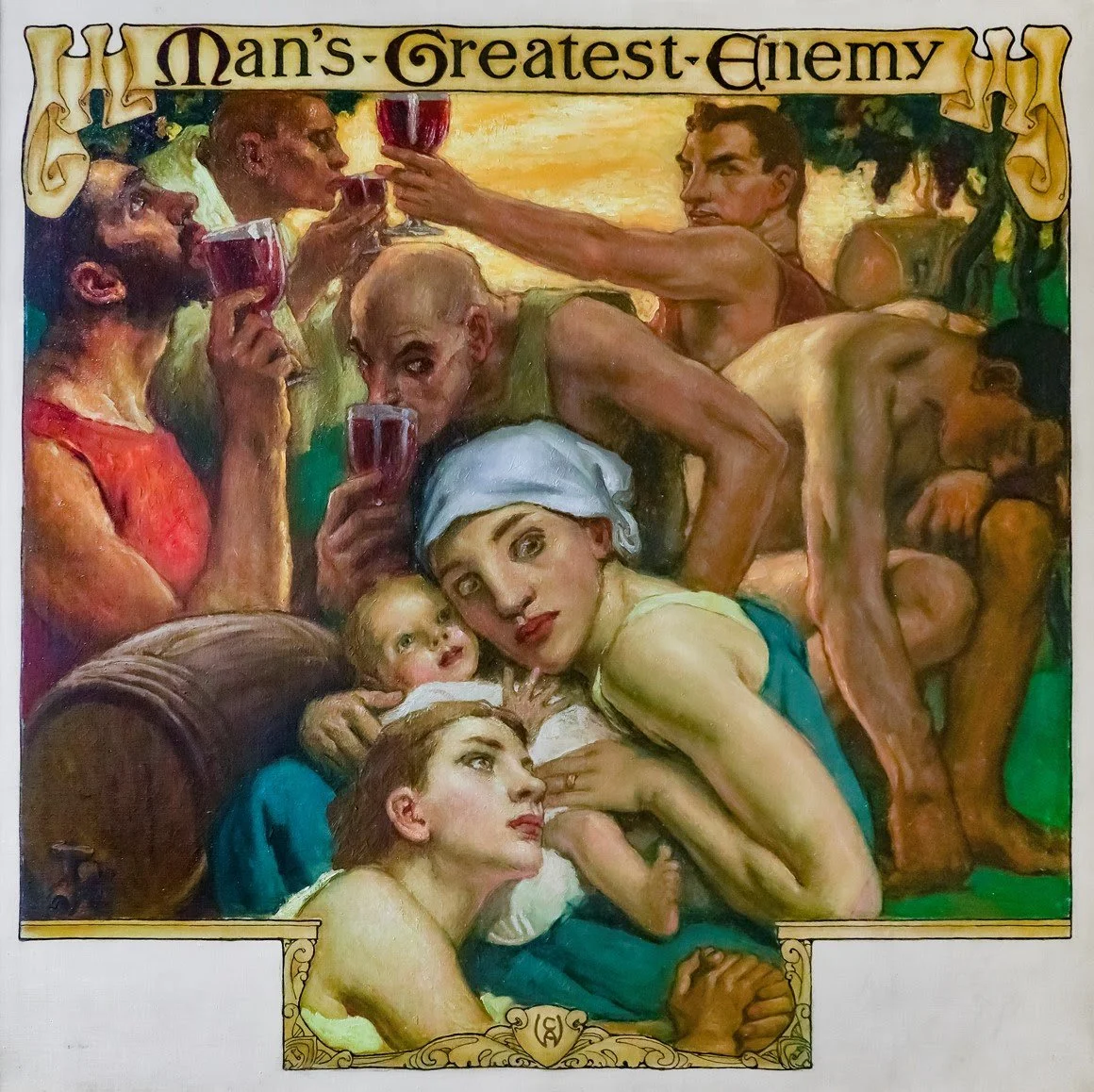

Even in moderation?

“Man’s Greatest Enemy” (c. 1915, oil on canvas), by Charles Allan Winter (1869-1942), at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass.