Llewellyn King: Today’s lessons from the 1970’s energy crises

During the 1973-74 part of the 1970’s oil crisis.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I’ve been here before. I’ve heard this din at another time. I’m writing about the cacophony of opinions about global warming and climate change.

In the winter of 1973, the Arab oil embargo unleashed a global energy crisis. Times were grim. The predictions were grimmer: We’d never again lead the lives we had led -- energy shortage would be the permanent lot of the world.

The Economist said the Saudi Arabian oil minister, Sheik Ahmad Zaki Yamani, was the most important man in the world. It was right: Saudi Arabia sat on the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

Then as now, everyone had an answer. The 1974 World Energy Congress in Detroit, organized by the U.S. Energy Association, and addressed by President Gerald Ford, was the equivalent in its day to COP26, the UN Climate Change Conference which has just concluded in Glasgow, Scotland.

Everyone had an answer, instant expertise flowered. The Aspen Institute, at one of its meetings, held in Maryland instead of Colorado to save energy, contemplated how the United States would survive with a negative growth rate of 23 percent. Civilization, as we had known it, was going to fail. Sound familiar?

The finger-pointing was on an industrial scale: Motor City was to blame and the oil companies were to blame; they had misled us. The government was to blame in every way.

Conspiracy theories abounded. Ralph Nader told me that there was plenty of energy, and the oil companies knew where it was. Many believed that there were phantom tankers offshore, waiting for the price to rise.

Across America, there were lines at gasoline stations. London was on a three-day work week with candles and lanterns in shops.

In February 1973, I had started what became The Energy Daily and was in the thick of it: the madness, the panic -- and the solutions.

What we were faced with back then was what appeared to be a limited resource base that the world was burning up at a frightening rate. Oil would run out and natural gas, we were told, was already a depleted resource. Finished.

The energy crisis was real, but so was the nonsense -- limitless, in fact.

It took two decades, but economic incentive in the form of new oil drilling, especially in the southern hemisphere, good policy, like deregulating natural gas, and technology, much of it coming from the national laboratories, unleashed an era of plenty. The big breakthrough was horizontal drilling which led to fracking and abundance.

I suspect if we can get it right, a similar combination of good economics, sound policy, and technology will deliver us and the world from the impending climate disaster.

The beginning isn’t auspicious, but neither was it back in the energy crisis. The Department of Energy is going through what I think of as scattering fairy dust on every supplicant who says he or she can help. On Nov. 1, DOE issued a press release which pretty well explains fairy dusting: a little money to a lot of entities, from great industrial companies to universities. Never enough money to really do anything, but enough to keep the beavers beavering.

That isn’t the way out.

The way out, based on what we have on the drawing board today, is for the government to get behind a few options. These are storage, which would make wind and solar more useful; capture and storage of carbon released during combustion; and a robust turn to nuclear power.

All this would come together efficiently and quickly with a no-exceptions carbon tax. Republicans will diss this tax, but it is the equitable thing to do.

Nuclear power deserves a caveat. It is unique in its relation to the government, which should acknowledge this and act accordingly.

The government is responsible for nuclear safety, nonproliferation, and waste disposal. It might as well have the vendors build a series of reactors at government sites, sell the power to the electric utilities, and eventually transfer plant ownership to them.

The government has some things that it alone is able to do. Reviving nuclear power is one.

The energy crisis was solved because it had to be solved. The climate- change crisis, too, must be solved.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Using school buses, etc., to store energy in the new electricity revolution

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Carbon-free electricity isn’t a final destination – it is merely a stop along the road to a time when electricity becomes the clean fuel of choice and reduces pollution in buildings, cement and steel production, transportation and other places and industries.

That is the glorious future that Arshad Mansoor, president and CEO of the Electric Power Research Institute, sees. He revealed his vision on White House Chronicle, the weekly news and public-affairs program on PBS, which I host, on his way to the COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland.

Mansoor, who talks about the future with an infectious fervor, was joined on the broadcast by Clinton Vince, chairman of the U.S. Energy Practice at Dentons, the globe-circling law firm, and Robert Schwartz, president of Anterix, a Woodland Park, N.J.-based firm that is helping utilities move into the digital future with private broadband networks.

Mansoor outlined a trajectory in which electric utilities must invest substantially in the near future to deal with severe weather and decarbonization. For example, he said, some power lines must be put underground and many must be tested for much higher wind speeds than were envisaged when they were installed. Some coastal power lines must be raised, he said.

While driving toward a carbon-free future, Mansoor cautioned against utilities going so fast into renewables the nation ignores the ongoing carbon-reduction programs of other industries. Further, if utilities can’t meet the electricity demands of transportation or manufacturing, these industries will turn away from the electric solution.

“Overall, we looked at the numbers and they showed a huge national role in decarbonization for the electric utility industry,” Mansoor said. However, the transition is fraught. It must be managed, sometimes using more gas until the system can be totally weaned from fossil fuels, he said. An orderly transition is vital.

Clinton Vince said the electric utility world has experienced a lot of volatility from severe weather, due to climate change, to the Covid-19 pandemic, and cyber-intrusions. “If I were to boil down to one word what is vital for utilities, it would be ‘resilience.’ ”

Resilience is an ongoing utility goal: It is the ability of a single utility or a group of utilities to bounce back from adversity, often by restoring power quickly. Anterix’s Robert Schwartz said that with his company’s private broadband networks and the deployment of enough sensors, a utility could identify a power line break in 1.4 seconds, before it hits the ground.

One of the most exciting and revolutionary aspects of Mansoor’s thinking is that the consumer will become a partner in the electric utility future. They will join the ecosystem by providing load-management assistance through smart meters, now installed in 60 percent of homes.

Mansoor thinks that the nation’s 480,000 school buses, if electrified, along with private electric vehicles, can be used to store energy. This answers the concern many utility executives have about storage and the concern that a tsunami of electric vehicles will overpower electric supply in the coming decade.

I think the utilities should plan right now for the integration of electric vehicles into their systems. They should offer electric vehicle owners financial incentives for plugging in and sending their stored power to the grid.

Likewise, the utilities should provide rate incentives for off-peak electric vehicle charging. They could do worse than look at the algorithms that have made Uber and Lyft possible, unlocking value in the personal car.

The utilities could devise a flexible system whereby they pay for power when needed and give a price break for charging during off-peak hours, or when there is a surfeit of renewable energy. That is the kind of data flow that will mark the utilities going forward and stimulate demand for private broadband networks.

We, the consumers, will be partners in the electric future, managing our own uses and supporting the grid with our electric cars and trucks. That is Mansoor’s achievable vision.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

White House Chronicle

‘Embracing chaos to make art’

“Chaos Gives Birth To Being’’ (oil on canvas), by Daniel Heyman, in his show “Summons,’’ at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, Oct. 30-Dec. 31.

Kathleen Tolan in the “Summons’’ catalog essay, writes:

“{T}h giant, squatting on bright green rocks in a blue sea, his body covered with babies crawling on him, being born by him. He points up at a bunch of purple grapes. I think of Dionysus, of the playful lover of life, and I think of the necessity of embracing chaos to make art.’’

The gallery says:

“Daniel Heyman is an artist whose work in drawing, printmaking and painting directs the viewer's attention to contemporary social and political issues. Deeply interested in narrative, he uses images to tell stories that combine a love of history and myth in an effort to provoke discussion and empathy. In his recent “Summons’’ series, Heyman emphatically returns to images without words. His previous effort, the monumental woodcut “Janus’’ from 2019-2020, represents time as an endless string of birth, renewal and death for creatures and ideas. Here, even the very human act of making culture is seen as both creative and destructive, signaling the profound influence Japanese art and culture has had on his work.’’

Daniel Heyman lives in Tiverton, R.I., partly a Providence and Fall River suburb and partly an affluent summer place with a beautiful shoreline and some farms, too.

The Union Public Library, part of the Tiverton Four Corners Historic District, has been operating since 1820.

View from Ft. Barton, in Tiverton

More than random

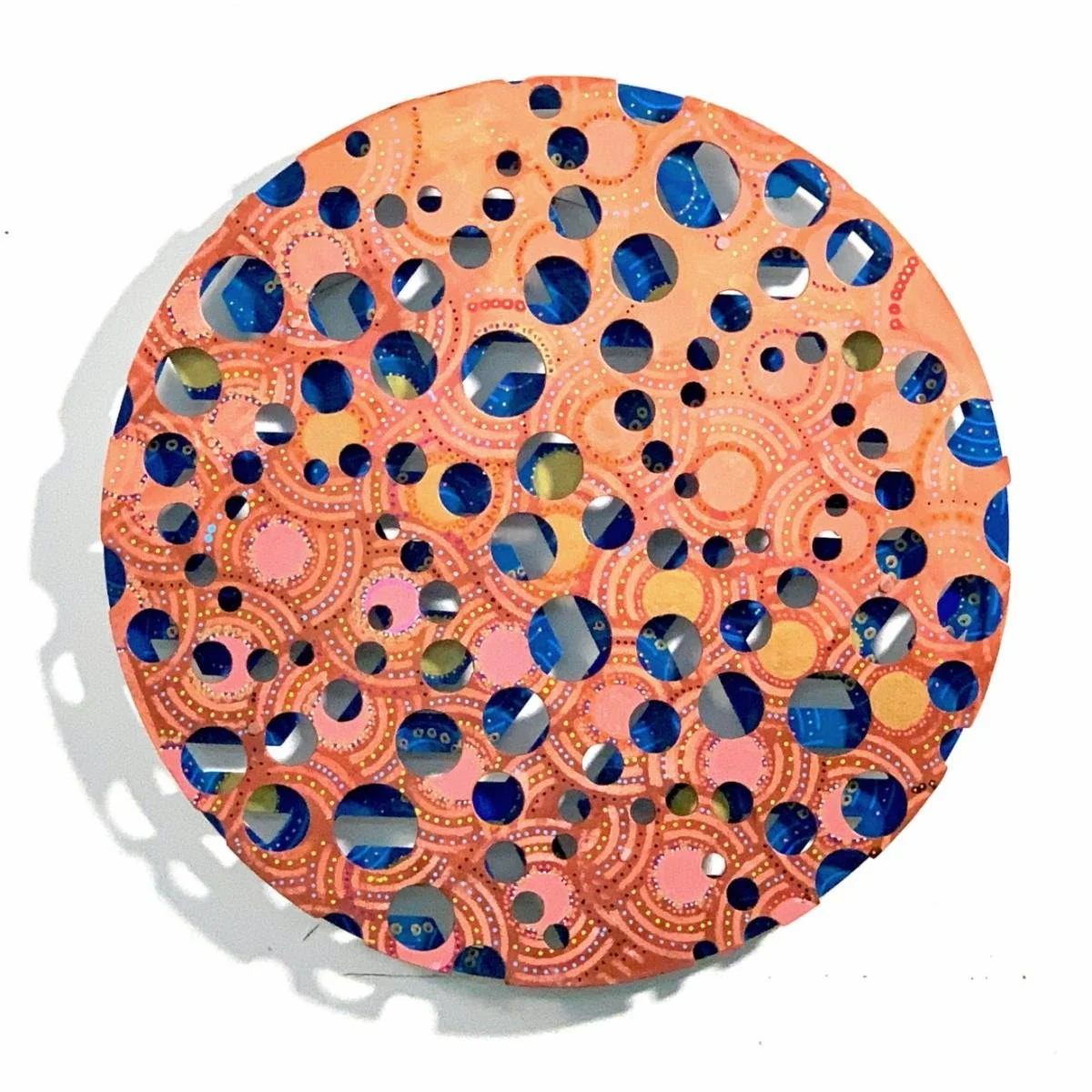

“Random Order” (acrylic paint on aluminum), by Ed Andrews, in his show “Transplant,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, through Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“Andrew's battles with leukemia, with the environment, with movement are defined against a traditional dictionary definition and crafted into sculptures of bronze, aluminum and stainless steel. The process is meticulous and intricate — cutting the metal into shapes, and hand painting and etching the material with acid to create his haunting patterns.’’

Mr. Andrews, a native of the Midwest., now lives in the semi-rural town of Glocester, R.I.

Antique store in the Glocester village of Chepachet, a farming community into the 20th Century

— Photo by Swampyank

Another take on COVID-19

“MACRO vs micro’’, by Teddy Trocki-Ryba, of Jamestown, R.I., in the show of the same name at AS220, Providence, through Oct. 30.

It’s a fresh take on the experience of COVID-19 in public and in private. As explained in Trocki-Ryba's artist statement, "the work displayed … seeks to juxtapose the MACRO experience of community and government with the micro experience of family and individual life" during the pandemic.

Windmill in Jamestown, R.I., the increasingly affluent and still partly semi-rural town/island in Narragansett Bay

A very comfortable faith

The superyacht Azzam, which from 2013 to 2019 was the largest private yacht in the world.

For N.T.

The path to joy is faith in God,

The young man told his friend.

His joy was plain upon his face;

He hoped not to offend.

All night they talked, and on the morn,

When day dawned bright and hot,

He shook her hand and wished her well

And set out on his yacht.

By Felicia Nimue Ackerman, a poet and a Brown University philosophy professor. This poem is slightly revised from one that ran in Free Inquiry.

Harbour Court, the Newport, R.I. headquarters of the hyper-exclusive New York Yacht Club

Llwelleyn King: Good reasons to venerate the gig economy

Professional dog walker

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Napoleon didn’t deride the English as “a nation of shopkeepers,” although that phrase is commonly attributed to him. In fact, it was Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac, a French revolutionary who used it when attacking the achievements of British Prime Minister William Pitt, the Younger.

I think that Napoleon was too smart not to have realized that a nation of shopkeepers is a strong nation, and that if the English of the time were indeed a nation of shopkeepers, they would constitute a more formidable enemy.

A nation of shopkeepers, to my mind, is an ideal: self-motivated people who know the value of work, money and enterprise; and who are almost by definition individualists. So, I regret the constant threats to small business coming from chains, economies of scale, high rents and some social stigma.

But mostly I regret that in our education system, self-employment isn’t celebrated and venerated as being equivalent to work at larger enterprises. We define too many by where they work, not by what they do.

I have always believed that one should aspire to work for oneself, to eschew the temptations of the big, enveloping corporation and to strike out with whatever skills one has to test them in the market and to have the customer, not the boss, tell you what to do.

Our education system produces people tailored to be employed, not self-employed.

But things are changing. The gig economy was well underway before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and now it is roaring. Many employees found that the servitude of conventional employment wasn’t for them.

The gig world differs from the small business world that I have described in that it is small business refined to its absolute core: a one-person business, true self-employment.

There are many advantages in self-employment for society and for the larger business world. Hiring a self-employed contractor is easier for a company, not having to create a staff position and pay all the costs that go with it. Laying off a contractor isn’t as traumatic. The worker is more respected, and is asked to do things not commanded. The system gains efficiency.

But if employers come to see the gig economy as just cheap, dispensable labor, then the gig economy has failed.

The gig worker shouldn’t expect security but should be treated in a business-to-business environment. He or she needs to know how to drive a bargain and to have the moral courage to ask for a contract that is fair and recognizes the value that is intrinsic in the gig relationship.

I am a fan of Lyft and Uber. They offer self-employment to anyone with a driver’s license and a car — and the companies will even get you into a car. But the bargain is one-sided. The driver has the freedom to work what hours he or she chooses but not to negotiate the terms of their engagement. That is decided by a computer in San Francisco.

This gig worker can’t hope to hire other drivers and start a small business: It doesn’t pass the gig contract concept. I have talked to many ride-share drivers. They revel in the freedom but not the income.

Gig workers can be, well, anything from a plumber to a computer programmer, from a dog walker to an actuary.

But for the free new world of gig working to become part of our business fabric, the social structure needs to be adjusted by the government to allow for the gig worker to enroll in Social Security and to charge expenses against taxes as would an incorporated business. Jane Doe, who makes a living designing websites, needs to know that she is a business, not just freelancing between jobs.

A friend who has been self-employed for many years told me recently that he was being considered for a big staff job. I told him to be mindful that he will be trading away some dignity and a lot of freedom. It is hard to get into a harness when you have been running free.

I hope we get many more workers running free. Napoleon would have understood.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., and his email is llewellynking1@gmail.com

White House Chronicle

Leave him up

William Blackstone in glorious stainless steel in Pawtucket, R.I.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The bookish William Blackstone (1595-1675) (also called Blaxton) was an Anglican minister who might have been the first permanent white resident of what is now Rhode Island, moving down from Boston and settling in today’s Lonsdale section of Cumberland in 1635, the year before Roger Williams founded Providence. The Blackstone River and a bunch of other things around here are named for him.

In the future Cumberland, on the east bank of the river that would bear his name, the reclusive and apparently kindly and tolerant intellectual read, wrote, tended cattle, planted gardens, and cultivated an apple orchard; he came up with the first variety of American apples, the Yellow Sweeting. He called his home "Study Hill," and it was said to have the largest library in the English colonies at the time. Sadly, his library and house were burned down in 1675 during King Philip's War, the very bloody and destructive conflict between Native Americans and English colonists that lasted from 1675 to 1678 and changed the course of American history. Blackstone died in 1675, just before the outbreak of the conflict.

Consider that his friends included the Narragansett tribe chiefs Miantonomi and Canonchet and the Wampanoags’ Massasoit and Metacomet. Metacomet is also known as King Philip (to mark the friendly relations his father, Massasoit, had with the English), whose followers were the ones who destroyed Blackstone’s home.

But now some Narragansetts want a new stainless-steel sculpture of Blackstone at the corner of Roosevelt and Exchange streets in Pawtucket taken down. They’re trying to make him into some sort of symbol of the brutal white takeover of their lands and the vast suffering and death of Native Americans that accompanied the English colonialization of what the English named New England. But Blackstone is a pretty inaccurate example of white aggression!

It’s appropriate that his statue remain up, given his importance to the history of the region. It’s not as if this is a statue of the likes of the cruel slaveowner, and traitor, Robert E. Lee. Such works are best kept in museums. (There are no statues of Hitler in outdoor parks in Germany, despite his historical importance.)

And, yes, you could say that George Washington was a traitor to Britain and he owned slaves. But unlike Lee, he didn’t take up arms against “his country” to ally himself with a “country’’ whose central mission in its rebellion against the United States was the preservation and indeed expansion of slavery. And Washington, whose slaves were freed at his death under his will, also was not considered a cruel slaveowner.

Anyway, why not see if a statue of a Native American chief from Blackstone’s time in Rhode Island could be commissioned to be put up near Blackstone’s? It would be culturally healthy if we had a wider range of historical figures represented by our public statues.

Here’s a nice crisp biography from the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame:

http://www.riheritagehalloffame.org/inductees_detail.cfm?iid=45

Llewellyn King: We're living in an earthquake

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have been in only one earthquake. It was in Izmir, Turkey, in 2014. The earth moved, undulating under my feet. Buildings shook and people’s fear could be felt.

Americans have reason to believe they are in a societal earthquake of unknown intensity or long-term consequence. Everywhere the earth we have known and trusted — political, social, economic, technological, and international — seems to be moving. Institutions are shaking, technology is obliterating the familiar; new and disturbing politics is rampant, left and right; and palpable climate change has arrived.

Our foreign skill set has been found wanting. Fear for the future is resident in our consciousness.

Our politics may be the most shaken of our intuitions. What we used to know how to do — like conduct an election — is in question and the fixes, as in conservative-introduced voting bills, threaten what we have held to be secure, those very elections. Electoral results are widely distrusted in a way they never have been previously.

We used to think we knew how to educate children. Now, that is in doubt as political factions fight over the curriculum, to say nothing of masks for children. To quote a vintage ad, “What’s a mother to do?”

The COVID-19 virus continues its ravages, reduced but not vanquished. It has left its mark: It has reshaped work and play to an extent we don’t yet understand. There are jobs, at least 10 million, going begging and workers who don’t want those jobs. They range from demand for drivers and warehouse personnel, reflecting the revolution in shopping, to airport workers, hospital staff, and, of course, restaurants.

Even the aerospace industry is begging. The Northrop Grumman plant in Maryland has a huge banner facing the Amtrak tracks seeking new hires.

It is a great time to change careers, obviously.

We don’t know whether work-at-home regimes will stay or whether the human need to congregate will win out. Do you move far from the office or wait out the phenomenon?

Technology controls our lives, and that isn’t always easy to live with. Try talking to any airline, insurance company, bank, or state agency and you will need a thorough familiarity with computers because the person on the line, or the recording, wants you off the telephone and online. This, even if you called because you were stymied online, to begin with.

If you get to a human, usually in Asia, that soul likely won’t have the advantages which come with having English as a first or second language. Hard-to-reach firms’ biggest asset isn’t, as they used to say, you, the customer. You don’t count to any large organization. Stop complaining and wait for a “customer-care representative,” who will tell you to get lost after you’ve waited for hours. You are now an insignificant part of mega-data, which some in the data business have called the new oil. Some corporate websites don’t publish a phone number. Don’t bother the tranquility of the C-suite.

The poor, who should be the beneficiaries of the new technologies, are victims. Take the unbanked: That large number of people who don’t have credit cards or a bank account. They can’t get rides from Uber or Lyft, and taxis are almost completely absent from city streets.

The unbanked can’t, should they be able to afford it, check into a hotel without plastic, or make a reservation for tickets to travel or go to a concert. They are non-members of society. They are on the wrong side of the digital divide — and that is a bleak place to be. Theirs are the children who got no education during the lockdowns and who will suffer through all their lives as a result. If you miss the techno train, you walk along tracks behind it.

The rise of China has damaged our self-esteem and we fear we are looking into the chasm of cold war or worse. Likewise, the calamitous end of our time in Afghanistan has further weakened our faith in our ability to get it right. (Heck, even “Jeopardy” can’t pick a host.) Our intelligence agencies seem to have totally failed, and our military doesn’t appear to be the winning institution we have been so proud of for so long.

After an earthquake, nations rebuild the structures. We need to start rebuilding with our institutions, and first among those is buttressing the democratic system. An invincible voting rights act would be a good starting place.

Our democracy hasn’t fallen yet, but it is shaking as the ground shifts under it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., and his email is llewellynking1@gmail.com

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King: A life in journalism: fascination and panic

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A young man asked me for advice on a career in journalism. The following is the letter I sent to him.

For advice about a career in journalism, I may not be the person to ask

I dropped out of school at 16 because I wanted to be a journalist. I wanted to know the great figures of my time and to travel the world. Journalism has not let me down.

To me, newspapering is almost a sacred calling. You can air injustice and celebrate genius. It is true, personal freedom: You always, at heart, work for yourself within a framework of your employment. You can talk to anyone in any office in any country and expect to be allowed an audience.

In the end, it is between you and the reader. We need income to practice our trade, but our communic is always between the writer and the reader.

The commodity is news. It is news in the humblest local paper or The Washington Post. Jack Cushman, who worked for me as the editor of Defense Week, and who became a star at The New York Times, told me once, "You used to tell me when I was writing a story, 'Come on, Cushman, you won't write it better in The New York Times.' You know what? I don't."

The message is: Be defined by what you write, not for whom you write it. But, of course, we all want to succeed and the measure of success can be where we work; that, I grant, and I have been a pursuer of good jobs everywhere, having worked for Time and Life as a very young stringer in Africa, the Daily Mirror and the BBC in London, The Herald Tribune in New York, and The Washington Post in Washington.

I am so much a journalistic romantic, I still get a thrill seeing my byline in any paper, big or small.

The work is simpler than people let on. Dan Raviv, then with CBS Radio, defined it for me this way, and I have never heard it said better, "I try to find out what is going on and tell people." Quite so.

I don't draw a line between magazines and newspapers, print and broadcast, or the Internet: The work is the same. The key of C, in which it is all centered, is still the newspaper, but that is changing. The struggle for accuracy, fairness and getting at the news never changes.

My first wife, the brilliant English journalist Doreen King, said that to succeed you need the "inner core of panic." That is fear that you made a mistake in a story: got a number wrong (billions not millions, for example), that you misspelled a name, and that you didn't fully understand what you were told in your reporting. The public doesn't know that we really struggle to get it right, often without the luxury of time -- an unending struggle.

Writing columns is something of an art, and some have it and some don't. A column is a newspaper within a newspaper; your own space to give evidence and share ideas. They are a fantastic form of journalism, but they aren't for everyone. To be a reporter you need news judgment. What is news? It is indefinable but if you don't have it, try something else. A test of news judgment is to watch the Sunday morning talk shows and write a mock story. Then survey what the other outlets have picked on and see if you found the same things newsworthy. You will know soon enough if you have news judgement.

I have been writing columns since the very beginning of my career. A young woman, who worked for me on The Energy Daily, was one of the finest reporters I have ever known. But when she was appointed the editorial page editor of a newspaper, she found it hard. Opinion didn't come easily to her. Facts were her domain. She moved to Europe, where she worked for a business information service and flourished. Her meticulous reporting was what was needed there.

If, like me, you have opinions about everything, then writing columns comes easily and the rest is technique. Read how others handled their material. Not what they opined, but how they managed it.

I don't hold that there is any difference between the needs of newspapers and magazines. I believe that news services or newspapers give you a grounding in the disciplines of writing that are very useful in magazine writing.

Journalism can be a hard life. A lot of journalists have money problems, drink to excess, and are known to have messy private lives. But, by God, we tell the world what is going on, and that is to be part of something huge and fabulous. It is a life of sheer adventure. I am glad of it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Brian P.D. Hannon: Of solar power and lots of tomatoes

Young tomato plants for transplanting in an industrial-sized greenhouse.

- Photo by Goldlocki

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

National Grid has offered incentives to a company proposing to build a massive farm facility in rural Exeter, R.I., in exchange for access to the solar power expected to help grow millions of tomatoes in temperature-controlled greenhouses.

A June 24 letter from National Grid senior counsel Andrew Marcaccio to Luly Massaro, a division clerk for the Rhode Island Division of Public Utilities and Carriers, states National Grid will offer “energy efficiency incentives” to Rhode Island Grows LLC “for the utilization of a combined heat and power project with a net output of one megawatt ... or greater.”

A capacity of 1 megawatt or more is a utility-scale installation for solar power.

National Grid asks the public utilities and carriers division to follow an authorized process for combined heat and power (CHP) projects by reviewing materials submitted with the letter, including a purchase-and-sales agreement from Rhode Island Grows related to the project, an estimated budget, benefit cost analysis and a November 2020 analysis providing “well-supported justification explaining why the economic benefits are reasonably likely to be obtained.”

The letter’s attachments also include a report on the natural-gas requirements and local impact of the operation.

“These documents represent a report including a natural gas capacity analysis that addresses the impact of the CHP Project on gas reliability; the potential cost of any necessary incremental gas capacity and distribution system reinforcements; and the possible acceleration of the date by which new pipeline capacity would be needed for the relevant area,” according to the letter.

National Grid’s letter asked the public utilities and carriers division to review the materials and provide an opinion either supporting or opposing the proposal by Aug. 13.

Gail Mastrati, assistant to the director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), supplied a link tracking the progress of the wetland permit sought by Richard Schartner, owner of the Schartner Farms property where Rhode Island Grows plans to build a 1-million-square-foot closed facility.

Asked if Rhode Island Grows is required to file separate permit applications for a solar array capable of producing more than 1 megawatts of power, Mastrati said the wetland and stormwater permit “is based on the size of the solar arrays, not the power output. If the number of solar panels were to increase, a new or modified permit would be required.”

“DEM does not permit the power output, just the size of the facility as indicated on the site plans,” Mastrati wrote in an email.

Mastrati declined to reveal the name of the company providing solar array services to Rhode Island Grows.

“DEM does not get involved with the choosing of the company to perform the work,” she said. “It is up to the owner to ensure that the contractor completes the work according to the permit.”

Rhode Island Grows chairman Tim Schartner and chief financial officer Frederick Laist did not respond to a request for comment.

The Rhode Island Grows project has drawn the support of Ken Ayars, chief of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Agriculture, as well as criticism from some Exeter residents concerned about the environmental and cultural impact of the massive growing operation that would use high-tech greenhouses to grow millions of tomatoes for distribution in six states throughout the Northeast.

Rhode Island Grows proposes to use a technology called controlled environment agriculture. The automated, hydroponic system can produce food on a large scale and has resulted in extensive agricultural production in the Netherlands, according to a video on the Rhode Island Grows website.

The company projects the operation could yield 650,000 pounds of tomatoes per acre, with an expansion to 350 acres in five years and eventually to 1,000 total acres, with five employees per acre.

The Exeter Town Council voted June 7 to return the Rhode Island Grows proposal for a zoning overlay district to the Planning Board for further consideration. The overlay would allow construction of the industrial-scale operation on the Schartner Farms property off South County Trail, where Rhode Island Grows prematurely broke ground June 1.

The five members of the council did not respond to a request for comment on the National Grid letter.

Brian P.D. Hanlon is an ecoRI News journalist.

Llewellyn King: Don’t kid yourself: Solutions to global warming won't be simple

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The latest report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change gives humanity a simple directive: Get a grip on greenhouse-gas emissions or the dear old planet won’t be the dear old planet we have known and loved down through the millennia.

Sounds simple, huh? Like wearing a face mask or getting a COVID-19 vaccine shot.

That is the trouble. Everyone will have his or her own science and won’t hesitate to inflict it on anyone who disagrees, whether it is verified or not.

Social nagging is about to become a national pastime. I can hear it now: “Why do you drive a gasoline car? You know, your fire pit is a carbon source.” Or “Did you think about the carbon consequences when you booked your vacation in Europe?”

How ghastly the moral superiority of the anti-carbon warriors will be! I can imagine them saying “I can’t imagine why people don’t buy electric cars. We have had one for three years.” Or “Your oil-heated house is a pollution source. We have installed solar rooftop panels. Passive solar houses should be mandated by the government.”

Remember the anti-smoking crusaders? I am afraid that you haven’t seen anything yet. The very real climate threat is going to unleash a whole new tribe of social scolds.

Electric utilities are in the crosshairs and there will be no end to their vilification. Watch out for the environment experts, who once urged the use of coal over nuclear, to take charge of the future with some other counterproductive policy nostrum.

All that said, I believe if we don’t get on top of the greenhouse-gas emissions problem, we soon will be wondering, as Robert Frost wrote, “Some say the world will end in fire,/ Some say in ice.” The way it is going, I say the world will end in devastating floods and heat waves, worsening droughts and accelerating sea-level rise.

The U.N.’s climate change panel has declared a clear and present danger. It is a threat that has been growing and largely laughed off over 50 years. I, for one, first heard of the idea of global warming in 1970, when it seemed very remote and a little crazy. It is neither remote nor crazy now. It is at hand, and it should affect a lot of thinking.

In the near term, common sense would have us ship our natural gas abroad so that China, India and many other countries stop burning coal; not as the anti-carbon warrior would have us close down our production. The best longer-term hope is more science on carbon capture and nuclear power. It is foolish to worry about nuclear waste lasting 10,000 years when, if we keep on the current climate trajectory, life won’t exist in the nearer future on planet Earth.

The fact is that while the science of climate change is well understood, the solutions aren’t. For example, those who would denounce natural gas, which is far less polluting than coal, don’t know the lifecycle costs of the two advocated alternatives, wind and solar.

To build a windmill, you need a large concrete base and a steel tower, both of which are manufactured through carbon-intensive processes. At the end of the life of a turbine, about 25 years, the giant blades, which are mostly made of carbon fiber-reinforced fiberglass, will be disposed of in landfills. The blades can’t be recycled, unlike the steel towers and other components.

Both the manufacture and disposal of solar cells have considerable environmental impact. The impact in making them is known, but the impact of their disposal in landfills isn’t known.

Going forward, the need is to know the science, encourage innovation and not to bow to culture activists who would wish their solutions on the rest of us. When I was a boy, asbestos was the miracle substance, recommended for inclusion in everything because it was fire-resistant. If you didn’t use asbestos, the fire alarmists came down on you. The moral? Beware of simple solutions to complex problems.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Solar panels on a house in a Boston suburb. Massachusetts is very big on green energy, at least rhetorically.

— Photo by Gray Watson

Llewellyn King: Nuclear literacy can save nuclear power

The Millstone Nuclear Power Station, on Long Island Sound in Waterford, Conn.

WEST WARWICK

In its first two decades of service, the Douglas DC-3 -- maybe the most amazing, safe and hardworking aircraft ever built -- was denounced in folk legend as wildly unsafe. It was branded a flying coffin by those who didn’t know the data.

The myth that it wasn’t airworthy matured into an out-and-out lie. In fact, the DC-3 was the workhorse that rapidly accelerated modern passenger aviation.

The DC-3 was saved by growing aviation literacy in the public. Can nuclear literacy save nuclear power, one of the greatest tools in containing global warming? I believe that it can. Literacy trumps myth and superstition.

While nuclear power has comparisons with the venerable DC-3, it is far more important than any single airplane. Those who turn their backs on nuclear power -- so needed as climate change accelerates – are akin to those who without knowledge were turning their backs on passenger aviation in 1935.

Today’s major public argument against nuclear power is that it leaves behind radioactive materials -- lumped together as nuclear waste – which will be radioactive for 10,000 years, about twice recorded human history.

This argument conjures up images of a monster, breaking out of its repository and marching the Earth, laying waste to whatever stands in its way -- a nuclear blob from a science fiction movie.

Truth is, in about 200 years, most high-level nuclear waste will have decayed into something less radioactively aggressive. In the first 30 years, it gets less toxic and more manageable.

As this explanation by William Reville, an eminent emeritus professor of biochemistry at University College Cork, published in the Irish Times, explains succinctly, “ The intense radioactivity reflects the preponderance of short-lived radioisotopes that are disintegrating quickly.

“This high rate of nuclear decay means the level of radioactivity declines quickly – the radioactivity of spent nuclear fuel reduces to 10-20 percent of its initial activity within six months of its removal from the reactor and within a few decades, the radioactivity reduces by a further factor of two. Radioactivity danger is largely gone within 100 years and within a few thousand years, the stored spent fuel is little more radioactive than the uranium ore that first came out of the ground to be fabricated into new fuel rods.”

Despite this science, when I advocate nuclear, which I have done for a long time, people roll their eyes and say, “What about the waste?” The waste does need to be stored safely, but it decays to a safe state quite quickly.

The most agonized-over nuclear material is the transuranic plutonium. Yes, it will last thousands of years, but it is easily shielded because it is an alpha emitter: It can’t penetrate human skin and can be blocked with a piece of notepaper. Natural uranium, found in rocks nearly everywhere, is an emitter, as is thorium, found in conjunction with rare earths. Radiation is everywhere. It isn’t the devil’s incarnation.

Those facing the climate crisis tend to shy away from nuclear and advocate only wind and solar. Little thought is given to the waste that these low-density energy sources are themselves going to produce.

Wind will create a huge volume of physical waste from the disposal of carbon-fiber turbine blades. These don’t recycle, unlike the steel towers on which the turbines rest. Eventually, tens of millions of tons of solar panels will make their way to landfills.

If you want to fret about waste -- and you should -- look to the garbage that is crowding the landfills, especially plastic which doesn’t break down. Look to the billions of tons of junk that is making its way into the oceans, killing marine life, and shudder.

The Earth can take a lot of nuclear waste from power plants, advanced medicine and reactors aboard navy ships and spacecraft. But can it take much more of the alternative?

Aviation literacy saved aviation from myth, even after disasters. Myth is a dangerous force when it is the foundation of policy.

If you want a good, safe myth, go with the tooth fairy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

ReplyReply allForward

Llewellyn King: Has COVID launched a new age for workers?

Most workers would like to slash the time they spend commuting.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Millions of Americans appear to be echoing the words of the Johnny Paycheck song “Take This Job and Shove It.” This is a sentiment that is changing the work scene, the way we work, and the future of work.

The workers of America are shuffling the deck in a way that has never happened before. It is accentuating an acute labor shortage.

I receive lists of job openings every day and the common denominator seems to be that you must show up at a place of business. Among the big and seemingly frantic employers are FedEx, Walmart and Amazon. Warehouse workers and delivery drivers are the most sought-after employees.

To overcome the labor shortage, wages are rising and adding to the rising inflation -- although what part of that rise is labor cost isn’t clear. Other factors are pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, a tightening of food flows from California and other Western states, and the acute housing shortage. The economy is rebalancing; and so are workers, reassessing their lives and making changes.

There has been a severe shortage of skilled workers for a long time. It has been felt almost everywhere from construction to electric line workers. It is just worse now, exacerbated by immigration restrictions and workers who have joined the reshuffle.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, millions of individuals have assessed what they do and, apparently, found it wanting.

America’s workforce isn’t returning to the jobs that they held before the lockdown. Some are trying new things; others are demanding changes in the workplace. There is a demand for more remote working. The rat race is running short of willing rats.

Commuting seems to be the one big no-no. People in the major work hubs such as New York, Washington, Chicago, Boston and San Francisco have sampled the joys and the failings of working from home, and commuting has lost.

I know people who used to spend four or five hours every day getting to work and back home in all these cities. Sitting in a traffic jam is neither creative nor the best use of human life, these people are now saying.

In the movie Network, Peter Finch bellows, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” That is the new sentiment towards rigid travel and rigid work schedules. Working from home has taken people up the hill and shown them the valley, and they have liked the valley.

Other workers, particularly at the lower end of the work scale, have wondered whether they wouldn’t be happier doing something else now that they have had time to ponder. A friend of mine’s daughter who was a professional waiter in Florida now works for a printer. She has found she gets a more dependable income, better hours and that incalculable: a happier work environment.

I love small business, and I believe it to be the essential force for innovation and job creation. But it is also where petty boss-tyrants flourish. Lousy, egomaniacal employers aren't hard to find, especially in the restaurant business.

When I worked as a waiter in New York, between journalism jobs, I knew waiters who dreamed of the great restaurant where the tips are generous and, above all, the “patron is nice.” Unseen, there is a lot of cussing and pressure in any restaurant, and job security is unknown.

Enforced downtime has caused many to wonder whether they are even in the right line of work; whether the money, prestige or social recognition that may have gone with their old job was worth it.

For others, the gig economy has beckoned, where the employer has been cut out. Particularly, this is true of young people in communications and related work. Geeks are a hot item and can contract directly. But others, from landscape gardeners to plumbers, are going gig. The downside is there are no benefits, from Social Security deductions to pensions and health care. Society is lagging in recognizing this new arena of work.

Peculiarly, we aren’t at full employment. Unemployment is hovering around 5.9 percent and has gone up slightly as the summer has progressed. This raises the question of how many of the formerly employed are now in the gig economy, skewing the figures.

We are in what is, in effect, a post-war recovery. Traditionally, that is a time for social readjustment, for old bonds to be loosed, and for new energy to be released. Is it time to sack the boss?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Frank Carini: In two areas on R.I. coast — improvement and new challenges

The Nature Conservancy and its partners installed a living shoreline at Rose Larisa Memorial Park, in East Providence, to help keep coastal erosion at bay.

— Photo by Frank Carini/ecoRI News)

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I.

Growing up in the 1970s and ’80s across the Seekonk and Providence rivers in Rhode Island’s capital, John Torgan spent plenty of time exploring the state’s urban shoreline.

He remembers them as dumps filled with sewage and littered with decaying oil tanks.

“They were horribly polluted,” said Torgan, who still lives in Providence. “No one was fishing or sailing.”

His childhood memories, however, also include the beauty of a peaceful island in the middle of a shallow 4-mile-long salt pond.

The fortunes of these waters and their surroundings have changed since an adolescent Torgan, now 51, was skipping rocks, collecting shells and investigating the coastline for marine life. The Providence and Seekonk rivers are still impaired waters, but, like the chain-link fence topped with barbed wire that once separated much of these waterways from the public, the derelict oil tanks have been removed. The rivers’ health has improved.

The two rivers, both of which share a legacy of industrial contamination and suffer from stormwater-runoff pollution, aren’t recommended for swimming, but life on, under and around them has returned. Menhaden, bluefish, river herring, eels, osprey and cormorants are now routinely spotted. The occasional seal, dolphin, bald eagle and trophy-sized striped bass visit. Kayakers, fishermen, scullers and birdwatchers are easy to find.

Torgan, who spent 18 years as Save The Bay’s baykeeper, called the comeback of upper Narragansett Bay “extraordinary” and “dramatic.” He credited the Narragansett Bay Commission’s ongoing combined sewer overflow project with making the recovery possible.

As for that summer cottage on Great Island in Point Judith Pond, he said “tremendous development” has changed the neighborhood. Bigger houses now surround the Torgan family’s saltbox cottage, adding stress to one of Rhode Island’s largest and most heavily used salt ponds.

There is a diverse mixture of development around the shores of the pond that straddles South Kingstown and Narragansett. In the urban center of Wakefield, at the head of the pond, and at the port of Galilee at its mouth, there is an abundance of commercial development and a corresponding amount of pavement. The impacts are beginning to show.

Early last year the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management decided, based on ongoing water-quality monitoring results, to reclassify two areas of Point Judith Pond from approved to conditionally approved for shellfish harvesting. Water samples collected in the pond after certain rain events showed elevated bacteria levels and resulted in several emergency and precautionary shellfishing closures.

An underappreciated coastline

As an adult, Torgan’s interest in and passion about the marine environment hasn’t waned. The avid boater and angler has spent much of his working life protecting the Ocean State’s namesake, especially the waters not typically associated with its catchy moniker.

“This is the coast,” Torgan said while standing at the water’s edge at Rose Larisa Memorial Park. “The coast of Rhode Island doesn’t start at Rocky Point. It’s not just the beaches of South County.”

But, like most of the state’s coastline, the East Providence shoreline is vulnerable to accelerated erosion driven by the climate crisis and growing development pressures. Like much of the state’s urban shoreline, the health of this stretch of beach is better but hardly pristine. It is littered with chunks of asphalt and broken glass, most of its sharp edges dulled by tumbling in the sea. Swimming isn’t advised.

The climate challenges and improved health are why the organization Torgan currently heads, the Rhode Island chapter of The Nature Conservancy, took an interest in protecting this underappreciated stretch of beach.

More frequent and intense storms, combined with increasing sea-level rise, are eroding beaches and bluffs and damaging the state’s diminishing collection of coastal wetlands. Torgan said dealing with the negative impacts of this reality, plus increased flooding, is a huge challenge for Rhode Island’s 21 coastal communities. He noted adequately supported coastal resiliency projects that use nature are needed to inoculate the state against the changes that are coming.

To that end, The Nature Conservancy partnered with the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) and the City of East Providence last year to test the effectiveness of “living shoreline” erosion controls at the popular Bullocks Point Avenue park.

The park’s steep coastal bluff rises 20-30 feet above a narrow beach. In several areas, however, erosion has crumbled sections of the bluff, exposed root balls and felled trees. Previous efforts to reduce erosion through human-made practices, such as the installation of riprap and seawalls, failed.

As its name suggests, the living shoreline model incorporated more natural infrastructure. Unlike concrete or stone seawalls, living shorelines are designed to prevent erosion while also providing wildlife habitat. Hardened shorelines, compared to living ones, also diminish public access.

The first step in returning nature to a prominent role at this coastal park, at the head of Narragansett Bay’s tidal waters, was removing debris, such as large concrete slabs more than 20 feet long that were sitting at the bottom of the bluff, left behind by those failed human attempts to keep Mother Nature at bay.

Then, at the northern end of the park, the bank was cut away to reduce the slope. Stone was placed at the base of the bluff and logs made of coconut fiber were installed farther up the slope. The bluff was planted with native coastal vegetation. Near the southern boundary, low piles of purposely placed rocks and rows of beachgrass and native plants were added.

In other areas along this stretch of upper Narragansett Bay beach, boulders, cement walls and wooden structures, to varying degrees of success, strain to keep East Providence backyards from eroding and the bay from encroaching.

“As a matter of policy, we need to change our relationship with water where we’re not trying to hold it back and keep it out,” Torgan said. “In a more comprehensive way, think about how can we manage it and create basins where we are welcoming the water. That will help with flooding. It will help with sea-level rise and storm damage. It will improve water quality. The long view is changing the mindset that says we need to wall off the rising water and instead think about natural approaches and strategies that allows us to move with it.”

He noted that while living shoreline techniques have been implemented elsewhere in the United States, few have been permitted, built and evaluated in New England. He said small-scale projects like this one give coastal engineers and coastal permitting agencies a better sense of their cost and effectiveness, most notably in areas that aren’t exposed to open-ocean shoreline, like along much of the South Coast, where these artificial marshes would likely be unable to blunt stronger wave action.

When the 2020 project was announced, CRMC board chair Jennifer Cervenka said, “Much of Rhode Island’s coastline is eroding, and it’s a problem with no easy fix. This nature-based erosion control is one of the first of its kind in Rhode Island, and New England. We can’t stop erosion completely, but living shoreline infrastructure like this might buy our shores some valuable time.”

The project, which cost about $230,000, was funded by a Coastal Resilience Fund grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, The Nature Conservancy, the Newport-based foundation 11th Hour Racing and the Rhode Island Coastal and Estuarine Habitat Restoration Trust Fund.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Llewellyn King: The disappointing Kamala Harris

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Kamala Harris shone in the Senate when she was asking questions in hearings. That is where the idea that she might have presidential possibilities flourished. Democrats, observing her surefootedness, were led to think, “Here is the next Barack Obama.”

But the shine is off Harris and the tarnish is setting in.

When Harris ran for president, the only evidence of that hearing-room confidence was when she attacked front-runner Joe Biden in the Democratic debates. She implied that he was the proprietor of old ideas and hinted that he wasn’t up to date on matters of race.

So, it was extraordinary that Biden chose Harris to be his running mate. There were other strong contenders among those who had sought the Democratic nomination, and many more who hadn’t run for president. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.) should have been chosen: a tough, well-qualified woman of her times.

Biden, in choosing Harris, heard the music of diversity, which has been turned up of late. He felt the need to make history and to show that he was in accord with the values of today.

But he must have had some dealings with Harris when he was vice president; observed her in action in the Senate and heard about the difficulty she had organizing her small Senate staff. He must have done the political equivalent of due diligence. And he must have been cognizant of the damage that Sarah Palin did to John McCain’s candidacy in 2008.

Whereas Obama appeared not to think of himself as being of color, Harris clings to it. Her journey intrigues her; Obama’s didn’t intrigue him. He travelled it with purpose and dignity.

Now it must worry the president to learn, as the rest of us have, that Harris seems to have no ideas. Her public remarks are flip at worst and off-the-shelf liberal at best.

What does she see as the future for America? This isn’t laid out or even discernible. We need to know her vision because she is vice president to an old man – the metaphorical heartbeat away.

Harris and Biden have chosen to believe that solidarity at the top is an important message, hence the frequent references in White House announcements to the “Biden-Harris Administration.” In public, Harris is often at Biden’s side. But she often seems to be standing there as his girl Friday, not as the second-in-command.

In his well-reported piece in The Atlantic, Edward-Isaac Dovere hunted for the real Harris and didn’t appear to find her. He notes that she asks good, hard questions, like a good prosecutor, but as she dodges reporters, they aren’t able to ask good, hard questions of her.

It isn’t a given Democrats will back Harris if Biden turns out to be a one-term president, which given his age, 78, is a reasonable supposition. But ditching her would be hard because it might cost the party its progressive wing and keeping her might cost them as dearly in the center.

Republicans are salivating at the thought of running against Harris. She is the bright sun in their darkening sky.

The immigration assignment seems to have been thrust on Harris. It is unlikely she sought it. She doesn’t appear to have grasped it with relish. Save for brief visits to Guatemala and Mexico, she has done and said little.

Harris is finally looking at the chaos on the border herself. She needs to present a better idea than championing what amounts to nation-building in Central America. That has been tried and tried again and failed.

She isn’t going to solve the pain inherent in the immigration challenge, but it is a wonderful opportunity for her to give us her view of America, and what we might expect from a President Harris. Another assignment that could be thrust upon her.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: A very tricky recovery coming up; beware Western drought effects

Folsom Lake reservoir during the California drought of 2015

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

After the long, dark night of the pandemic, many are predicting a rosy dawn, followed by a bright summer day. The feeling is that we, the people, have borne the battle and can now celebrate the victory.

But recoveries are tricky, and this recovery will be trickier than most because we are coming out of hibernation into a place changed radically from the one where we began our COVID-19-avoidance slumber. We isolated in one world and are reconnecting in another.

Enthusiasm flows from a sense of accumulated demand and already evident brisk economic activity.

There is a labor shortage despite unemployment at 5.8 percent. I have been following job offerings across the country (I review dozens at a time) and this would appear to be a good time to get a new job or change up. Employers are sounding desperate; they are paying more and being accommodating.

Unfortunately, tight labor markets and rising house prices are often a harbinger of inflation.

Yet there are some wondrous possibilities. On the plus side, we are awakening into a new world of technology-driven change.

In transportation, the surge in electric vehicles is here to stay. Ford’s announcement that next year it will offer an all-electric F-150 pickup truck is significant. It breaks down technical barriers and, significantly, it also breaks down social ones.

Working men and farmers who have been dubious about electric vehicles, regarding them as being only for effete liberals, now can embrace the electric vehicle revolution. The electric F-150 will be a milepost in the electrification of transportation and socially changing attitudes.

New materials, such as graphene nanotubes and new ways of production using additive manufacturing, known commonly as 3D printing, will change the factory floor as well as add to the possibility of on-site production and the deployment of new, small factories.

Interconnectivity, sped by 5G, and the massive deployment of sensors will have its impact from the checkout at the grocery store to medical diagnosis, much of it done remotely as part of the swing to telemedicine.

Already, Domino’s Pizza is testing autonomous delivery vehicles in Houston. Like those ubiquitous scooters in cities, this will spread on the ground -- and in the air, as drones get into the game.

COVID-19 has stimulated not just medical research but also a general interest in research which will in turn promote more public funding. The COVID -19 vaccine successes reestablished a certain level of confidence in medical science.

But there are old-economy realities ahead.

Real estate is in boom and bust simultaneously. The future of office towers is uncertain, and the future of big shopping centers is precarious. The possibility of home buyers finding affordable houses is remote. Want to start married life living in a tent pitched in an abandoned department store?

A surge of homelessness is expected to follow the ending of the moratorium on evictions. Tens of thousands may be evicted as they haven’t paid rent for a year and won’t be able to do so. An equal number will be sitting in the dark as utilities finally start disconnecting for unpaid bills. One utility, CPS Energy, in San Antonio, has $105 million in uncollected bills. Multiply that across the country.

The federal government has, as it were, shot its wad, in stimulus and can’t be expected to step in and help renters with their back rent or electricity customers with their accumulated bills.

There is another disrupter on the horizon. It is drought, the worst recorded, which is drying up California and much of the rest of the West.

Expect reduced food production, affecting the whole country with higher prices, a terrible wildfire season, and even a shortage of electricity as dams across the West (including Grand Coulee on the Columbia River and Hoover on the Colorado River) will cut electricity output because of low water.

The mighty Colorado -- the life force for so much in the West, including farming and electricity production -- is running seriously low and will continue to decline as summer progresses. Hardship in the West will be felt in the North, South and East.

A new Dust Bowl? Technology hasn’t yet learned to make rain.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and his email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Robert Whitcomb <rwhitcomb51@gmail.com>

11:49 AM (3 hours ago)

to White, InsideSources, Llewellyn, Michael

Fine column!!

Llewellyn King

11:50 AM (3 hours ago)

to me

Thank you so much, Bob.

--

Executive Producer and Host

"White House Chronicle" on PBS;Columnist, InsideSources Syndicate;Contributor, Forbes; Energy CentralCommentator, SiriusXM Radio

Mobile: (202) 441-2702Website: whchronicle.com

Frank Carini: When you let the sands shift naturally

Dunes on Napatree Point

WESTERLY, R.I.

In late October 2012, about a day after Superstorm Sandy’s initial surge battered much of southern New England’s coast, especially its open-ocean shoreline, Janice Sassi navigated her way through a parking lot here filled with “mountains of mud” to find a “moonscape.”

“The dunes were completely flat,” recalled Sassi, manager of the 86-acre Napatree Point Conservation Area. “I thought it was done. It looked like one big beach.”

Sandy had ripped chunks of beachgrass from sections, and one area was forced back some 30 feet. At that moment and for days after, Sassi was concerned about Napatree Point’s future.

Her friend Peter August, a now-retired University of Rhode Island professor and a Napatree Point science adviser, put her racing mind at ease. The former director of URI’s Coastal Institute told her the resilient peninsula that offers sweeping views of Little Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound, and New York’s Fishers Island would be fine. He reminded her that Napatree Point had previously survived one of the most destructive and powerful hurricanes in recorded history.

The hurricane of 1938, also known as the “Great New England Hurricane,” smashed the peninsula’s 39 2- and 3-story houses that stood just a few feet from the churned-up fury of the Atlantic Ocean. The 3- to 4-foot-high wall in front of those summer homes did nothing to prevent their destruction.

Storm waves broke over roofs and plowed “through the cement seawall as if it were transparent,” R.A. Scotti wrote in her 2003 book, Sudden Sea: The Great Hurricane of 1938.

“If you build on a barrier beach, you are toying with nature,” she wrote.

On the other side of the Napatree Point peninsula, most if not all of the private docks that extended into Little Narragansett Bay were reduced to kindling. Some residents waited out the 100-year storm in the remains of decommissioned Fort Mansfield. Fifteen people died.

The historic ’38 storm, much more so than Superstorm Sandy nine years ago, pummeled the 1.5-mile-long, sand-swept peninsula that curves away from the affluent village of Watch Hill. It severed the connection to Sandy Point, now a mile-long island shared by Rhode Island and Connecticut. In the eight decades since Sandy Point was left afloat, the island has drifted one and a half miles to the north.

More than a century earlier, Napatree Point, which was then densely forested — its name reportedly derives from nap or nape (neck) of trees — was significantly altered by another hurricane. The Great September Gale of 1815 “wiped it clean” and no tree has grown there since, according to Scotti’s book.

Following the hurricane of 1815, Napatree Point was significantly developed, and saw the construction of a boarding house and a hotel. By the end of the century, construction of Fort Mansfield had begun.

Though Sassi, then less than three years into her job after a career in law enforcement, was initially skeptical of August’s reassurances that her beloved Napatree Point would rebound, she’s thankful it did. She said it took about five years for the conservation area to completely repair itself. The beachgrass regrew, and the dunes regained their elevation.

Napatree Point was able to heal itself because humans have given it room to breathe. After the ’38 hurricane, one of the most financially destructive storms on record, developers looking to rebuild the summer cottages and construct other structures were rebuffed.

With no roads, homes, and hardened structures obstructing Mother Nature, Napatree Point has been allowed to change with the times. August noted that the barrier beach has the space to continually wash back over itself.

“It doesn’t erode away. It just moves,” said August, who founded URI’s Environmental Data Center three decades ago. “Napatree Point was 80 acres when the hurricane of ’38 struck; it’s 80 acres now, just in a different place. Napatree Point will always be here. It rolls with the punches. It gets changed but still exists.”

The Hope Valley resident said the geology of Napatree Point is a perfect example of how a barrier dune ecosystem works naturally. He explained that when Napatree Point is hit by big storms, such as the Great New England Hurricane or Superstorm Sandy, and wave action and tidal surge punch through the dunes, it creates wash-over fans on the backside, meaning the position of the peninsula’s dunes change; they aren’t lost.

“They’re rolling over themselves and they can do that because we’re letting the sand go where the sand wants to go,” August said.

Napatree Point is owned, managed and protected by a partnership of different interests: the Watch Hill Fire District, the Watch Hill Conservancy, which employs Sassi, the Town of Westerly, the state, and a few private landowners. Conservation easements protect it from future development.

In the summer, this slender strip of land — the average width is 517 feet — at the mouth of Little Narragansett Bay, where the Pawcatuck River empties into Block Island Sound, is overrun with tourists, boaters, beachgoers, hikers, anglers and nature observers. Finding a scrap of beach can be difficult, and some areas are roped off for important visitors, most notably piping plovers and American oystercatchers, both of which nest in the sand.

Sassi is thrilled that Napatree Point is so popular, but all the human visitors have an accumulating impact on the peninsula’s delicate dune system. The West Warwick, R.I., resident noted that the fact there is no development makes it easier for the small peninsula to defend itself from a changing climate and human intrusion.

The conservation area, however, isn’t immune to sea-level rise and other stressors associated with the climate crisis. About three years ago, Sassi and August began noticing that the entrance to Napatree Point, through a large parking lot off Bay Street that is lined with boutique shops and a mix of culinary options, began to flood during extremely high tides.

It’s now beginning to flood even during normal high tides. As sea levels rise and more frequent flooding occurs, access to the peninsula, at least via land, will become more and more restricted unless something is done. August said plans are underway to elevate the entrance, which laps up against Watch Hill Harbor.

Napatree Point is a barrier beach that has been shaped and reshaped by storms, sometimes profoundly, as was the case 206 years ago, 83 years ago, and nine years ago. The peninsula is composed of more sand than soil and its shoreline is worked upon daily by ocean waves and the tide. Like most barrier beaches, especially those with no human-made structures, Napatree Point is constantly in a state of flux. Since 1939, it has shifted north, toward Little Narragansett Bay, some 200 feet, according to mapping by the Coastal Resources Management Council.

The peninsula, however, is much more than a summer destination and a birdwatcher’s paradise. It’s also a habitat provider and a storm protector.

This fragile yet pliable barrier beach helps protect Westerly’s mainland. And to help protect Napatree Point’s dynamic ecosystem — and, thus, tourist-friendly Watch Hill — from storm surge, coastal erosion, and human visitors, a number of restoration projects have been undertaken.

During the past dozen years, some 4,000 native plants, such as seaside goldenrod, beach plum, swamp milkweed and groundseltree, have been added to help anchor Napatree Point’s shifting sands — their dense root mats keep erosion in check — and to attract pollinators.

Split-rail fences have been erected and signs posted to keep visitors and their wheeled coolers from making their own paths from the peninsula’s protected side to its open-ocean side. At one point several years ago, 50 crossover paths had been plodded through Napatree Point’s dunes and vegetation. Dinghies and Zodiacs land on the Little Narragansett Bay/Watch Hill Harbor side, before their occupants traverse the peninsula to the Atlantic Ocean side, where they lie in the sun, swim, and bodysurf.\

This tireless restoration work piloted by Sassi, August, Hope Leeson, Bryan Oakley and others has made Napatree Point a national model for stewardship, an important distinction since the area caters to an abundance of life, including mussel beds, bats, minks, foxes, deer, monarch butterflies, and a plethora of birds.

Off its coast are some of the biggest and healthiest eelgrass beds in Rhode Island waters. These vital marine ecosystems provide foraging areas and shelter to young fish and invertebrates, spawning surfaces for sea life, and food for migratory waterfowl. Gray and harbor seals hang out on the open-ocean side of the peninsula. In the winter, rafts of sea ducks are a common sight in the waters off the peninsula.

The Audubon Society has recognized Napatree Point as a globally important bird area. Veteran Rhode Island birder Rey Larsen has identified more than 300 different species of birds on the sandy, wind-swept peninsula.

The Napatree Point lagoon, about 3.5 feet deep in the middle, is home to a half-dozen different kinds of fish, including the American eel. It’s also an important horseshoe-crab nursery. The entrance to the 10-acre lagoon, from Little Narragansett Bay, is the peninsula’s most rapidly changing part, according to August. He said the entrance to the lagoon has moved a few times during the past decade alone.

Napatree Point, unlike much of Rhode Island’s built-up coastline, is better positioned to handle the climate crisis because humans are allowing its sands to shift naturally.

“The most important thing we can do is get people excited about Napatree Point so they want to protect it,” Sassi said.

For a wealth of science, stewardship, and monitoring information about the Napatree Point Conservation Area, click here.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Watch Hill and Watch Hill Cove from the eastern end of Napatree Point

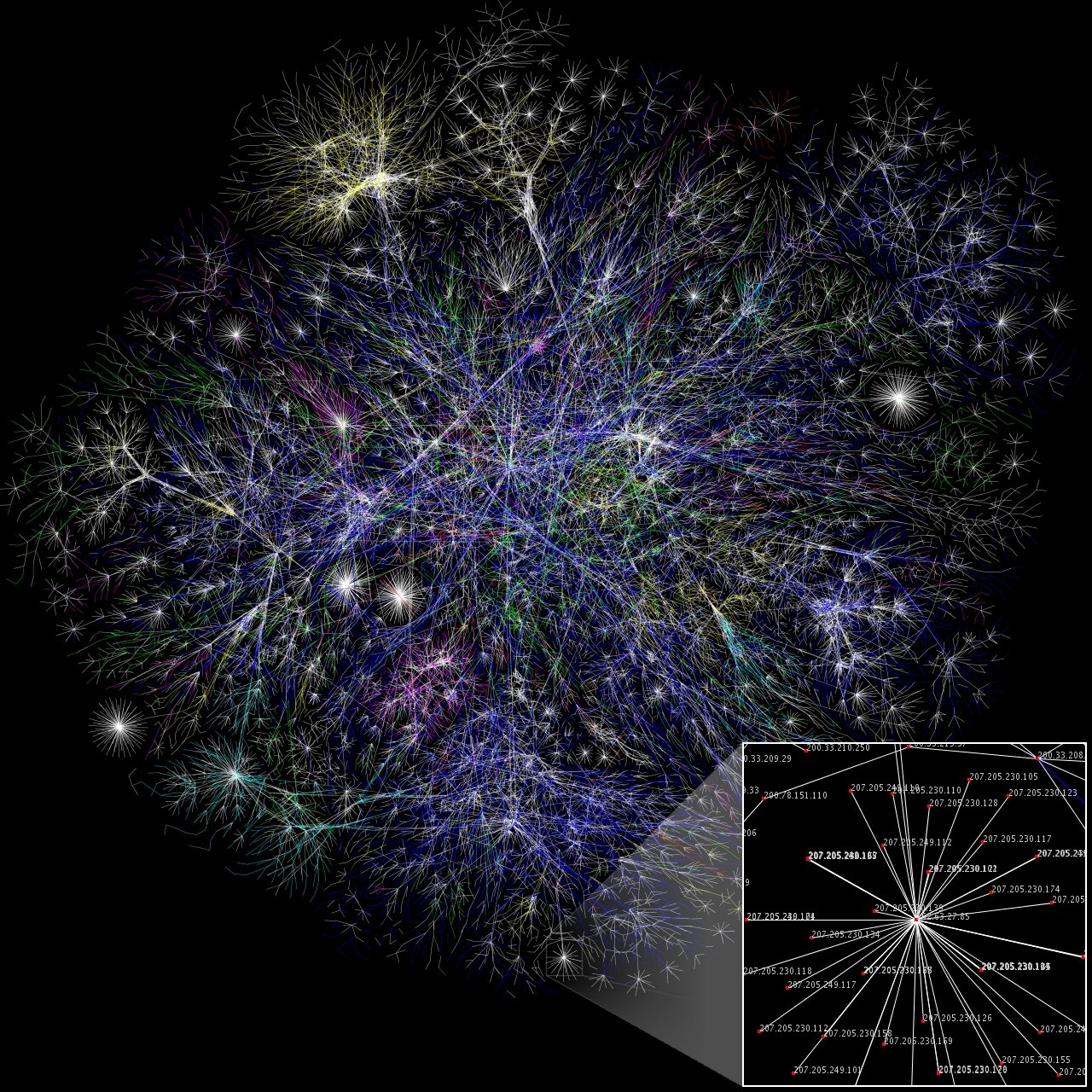

Llewellyn King: Interconnectivity at the heart of the revolution that’s upon us

Visualization from the Opte Project of the various routes through a portion of the Internet

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When we look back on the convulsion that is going to reset America — the great technology-driven revolution that will extend to nearly every corner of American life — it may be named for President Joe Biden, but it won’t be his revolution. It is innovation’s revolution. He will help finance it and smooth it out, but it is already happening and is accelerating.

Biden’s typically soft speech to Congress (no stemwinder he) was a wish list of things dear to him, but also an acknowledgement of what already is in motion.

Technology is rampant and government’s role should be to provide partnership and, above all, standards, according to two savants of the tech world, Jeffrey DeCoux, chairman of the Autonomy Institute, and Morgan O’Brien, a visionary in U.S. wireless telecommunications, now executive chairman of Anterix, a company providing private broadband wireless networks to utilities. Above all, they said in an interview with me for the PBS program White House Chronicle, standards for the new technology are essential.

Partial interconnection with different appliances, from road sweepers to drone delivery vehicles speaking only to identical devices, will be self-defeating. The internet without international standards would have failed.

Biden is set to preside over the greatest industrial leap forward since steam provided shaft horsepower to make factories a reality. If Congress allows, the Biden administration will finance much of the upgrading of the old infrastructure. It also will be called upon to be part of the new infrastructure, the technological one. That will be expensive; both DeCoux and O’Brien warned that it will take huge sums of money to build out complete 5G broadband networks, which will carry the load of interconnectivity.

For the nation to leap forward, these networks need to bring 5G broadband to every corner of it, O’Brien said. It can’t be allowed to serve only those places where population density makes it profitable.

In his speech to Congress, Biden laid out a revolutionary abstract for the future of the nation. The human side of the Biden infrastructure plan -- things like day care, free community college, better health care, prescription drug pricing -- is the true Biden agenda.

The technology revolution is seen by the president not for what it is, a resetting of everything in America, but rather as a way to job creation. It will create jobs, but that isn’t the driving force. The driver is and has been innovation: science helping people. That, in turn, will bring about a surge of productivity and prosperity and with that, new jobs, quality jobs – robots will soon be flipping hamburgers and painting houses.

This other agenda, the one that will make the fundamental difference between the nation of today and the nation of tomorrow, is the technological revolution. The evolutionary forces for this upheaval have been gathering since the microprocessor started things moving in the 1970s.

At the core of the coming changes is interconnectivity. That is what will craft the future. Cars on highways will be connected with each other through thousands of sensors, and these will speed traffic and enhance safety both for those with drivers and new autonomous ones. Likewise, drones will deliver many goods and they will need to be interconnected and have superior flight management. Every aspect of endeavor will be involved, from managing railroads to increasing electricity resilience and the productivity of the electric infrastructure.