David Warsh: A smelly red herring in Trump-Russia saga

Herrings "kippered" by smoking, salting and artificially dyeing until made reddish-brown, i.e., a "red herring". Before refrigeration kipper was known for being strongly pungent. In 1807, William Cobbett wrote how he used a kipper to lay a false trail, while training hunting dogs—a story that was probably the origin of the idiom.

Grand Kremlin Palace, in Moscow, commissioned 1838 by Czar Nicholas I, constructed 1839–1849, and today the official residence of the president of Russia

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A red herring, says Wikipedia, is something that misleads or distracts from a relevant and important question. A colorful 19th Century English journalist, William Cobbett, is said to have popularized he term, telling a story of having used strong-smelling smoked fish to divert and distract hounds from chasing a rabbit.

The important questions long have had to do to do with the extent of Trump’s relations with powerful figures in Russian before his election as president; and with whether the FBI did a competent job of investigating those charges.

The herring in this case is the Durham investigation of various forms of 2016 campaign mischief, including (but not limited to) the so-called “Steele Dossier’’. The inquiry into Trump’s Russia connections was furthered (but not started) by persons associated with Hillary Clinton’s campaign. {Editor’s note: The political investigations of Trump’s ties with Russia started with anti-Trump Republicans.}

Trump’s claims that his 2020 defeat were the result of voter fraud have been authoritatively rejected. What, then, of his earlier fabrication? It has to so with the beginnings of his administration, not its end. The proposition that Clinton campaign dirty tricks triggered a tainted FBI investigation and hamstrung what otherwise might have been promising presidential beginning has been promoted for five years by Trump himself. The Mueller Report on Russian interference in the 2016 election was a “hoax,” a “witch-hunt’’ and a “deep-state conspiracy,” he has claimed.

Today, Trump’s charges are being kept on life-support in the mainstream press by a handful of columnists, most of them connected, one way or another, with the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal. Most prominent among them are Holman Jenkins, Kimberly Strassel and Bret Stephens, now writing for The New York Times.

Durham, a career government prosecutor with a strong record as a special investigator of government misconduct (the Whitey Bulger case, post 9/11 CIA torture) was named by Trump to be U.S. attorney for Connecticut in early 2018. A year later, Atty. Gen. William Barr assigned him to investigate the president’s claims that suspicions about his relations with Russia had been inspired by Democratic Party dirty tricks, fanned by left-wing media, and pursued by a complicit FBI. Last autumn, Barr named Durham a special prosecutor, to ensure that his term wouldn’t end with the Biden administration.

There is no argument that Durham has asked some penetrating questions. The “Steele Dossier,” with its unsubstantiated salacious claims, is now shredded, thanks mostly to the slovenly methods of the man who compiled it, former British intelligence agent Christopher Steele. Durham’s quest to discover the sources of information supplied to the FBI is continuing. The latest news of it was supplied last week, as usual, by Devlin Barrett, of The Washington Post. (Warning: it is an intricate matter.)

What Durham has not begun to demonstrate is that, as a duly-elected president, Donald Trump should have been above suspicion as he came into office. There was his long history of real estate and other business dealings with Russians. There was the appointment of lobbyist Paul Manafort as campaign chairman in June 2016; the secret beginning on July 31 of an FBI investigation of links between Russian officials and various Trump associates, dubbed Crossfire Hurricane; Manafort’s forced resignation in August; the appointment of former Defense Intelligence Agency Director Michael Flynn as National Security adviser and his forced resignation after 22 days; Trump’s demand for “loyalty” from FBI Director James Comey at a private dinner a week after his inauguration, and Comey’s abrupt dismissal four months later (which triggered Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel to the Justice Department): none of this has been shown to do Hillary Clinton’s campaign machinations.

The Steele Dossier did indeed embarrass the media to a limited extent – Mother Jones and Buzzfeed in particular – but it was President Trump’s own behavior, not dirty tricks, that disrupted his first months in office. Those columnists who exaggerate the significance of campaign tricks are good journalists. So why keep rattling on?

In the background is the 30-year obsession of the WSJ editorial page with Bill and Hillary Clinton. WSJ ed page coverage of the story of John Durham’s investigation reminds me of Blood and Ruins, The Last Imperial War 1931-1945 (forthcoming next April in the US), in which Oxford historian Richard Overy argues that World War II really began, not in 1939 or 1941, but with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Keep sniffing around if you like, but what you smell is smoked herring.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

© 2021 DAVID WARSH

David Warsh: Perhaps we're in the Third Reconstruction

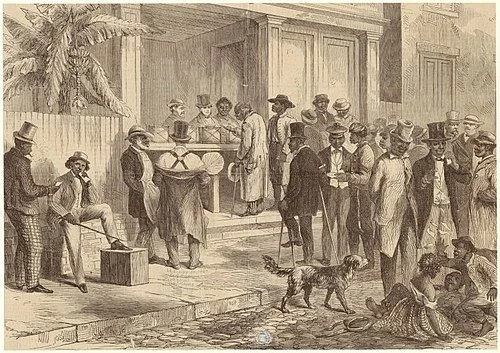

Former slaves voting in New Orleans in 1867. After Reconstruction ended, in 1977, most Black people in much of the South lost the right to vote and didn’t regain it until the 1960s.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“Reconstruction” (1865–1877), as high school students encounter it, is the period of a dozen years following the American Civil War. Emancipation and abolition were carried through; attempts were made to redress the inequities of slavery; and problems were resolved involving the full re-admission to the Union of the 11 states that had seceded.

The latter measures were more successful than the former, but the process had a beginning and an end. After the back-room deals that followed the disputed election of 1876, the political system settled in a new equilibrium.

I’ve become intrigued by the possibility that one reconstruction wasn’t enough. Perhaps the American republic must periodically renegotiate the terms of the agreement that its founders reached in the summer of 1787 – the so-called “miracle in Philadelphia,” in which the Constitution of the United States was agreed upon, with all its striking imperfections.

Is it possible that we are now embroiled in a third such reconstruction?

The drama of Reconstruction is well documented and thoroughly understood. It started with Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, continued with his Second Inaugural address, the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox Courthouse; emerged from the political battles Andrew Johnson’s administration and the two terms of President U.S. Grant; and climaxed with the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution – the “Reconstruction Amendments.” It ended with the disputed election of 1876, when Southern senators supported the election of Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, in exchange for a promise to formally end Reconstruction and Federal occupation he following year.

The shameful truce that followed came to be known as the Jim Crow era. It last 75 years. The subjugation of African-Americans and depredations of the Ku Klux Klan were eclipsed by the maudlin drama of reconciliation among of white veterans – a story brilliantly related in Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, by David Blight, of Yale University. For an up-to-date account, see The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution, by Eric Foner, of Columbia University.

The second reconstruction, if that is what it was, was presaged in 1942 by Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal’s book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy, commissioned by the Carnegie Corporation. The political movement commenced in 1948 with the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces. The civil rights movement lasted from Rosa Parks’s arrest, in 1955, through the March on Washington, in 1963, at which Martin Luther King Jr. made delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, and culminated in the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Repression was far less violent than on the way to the Jim Crow era. There were murders in the civil rights era, but mostly they made newspaper front pages.

And while the second reconstruction entered on race, many other barriers were breached in those rears as well: ethnicity, gender and sexual preference. In Roe v Wade the Supreme Court established a constitutional right to abortion a decade after the invention of the Pill made pregnancy a fundamentally deliberate decision.

How do reconstructions end? In the aftermath of decisive elections, it would seem – in the case of the second reconstruction, with the 1968 election of Richard Nixon, based on a Southern strategy devised originally by Barry Goldwater. Nixon was in many ways the last in a line of liberal presidents who followed Franklin Roosevelt. He had promised to “end the {Vietnam} war” the war and he did. An armistice of sorts – Norman Lear’s All in the Family television sit-com – preceded his Watergate-inspired resignation. Peace lasted until the election of President Barack Obama.

So what can be said about this third reconstruction, if that is what it is? Certainly it is still more diffuse – not just Black Lives Matter, but #MeToo, transgender rights, immigration policy and climate change, all of it aggravated by the election of Donald Trump. This latest reconstruction is often described as a culture war, by those who have never seen an armed conflict. How might this episode end? In the usual way, with a decisive election. Armistice may takes longer to achieve.

For a slightly different view of the history, see Bret Stephens’s Why Wokeness Will Fail. We journalists are free to voice opinions, but we must ultimately leave these questions to political leaders, legal scholars, philosophers, historians and the passage of time. I was heartened, though, at the thought expressed by economic philosopher John Roemer, of Yale University, who knows much more than I do about these matters, when he wrote the other day to say “I think the formulation of the first, second, third…. Reconstructions is incisive. It reminds me of the way we measure the lifetime of a radioactive mineral. We celebrate its half-life, three-quarters life, etc….. but the radioactivity never completely disappears. Racism, like radioactivity, dissipates over time but never vanishes.”

David Warsh is a veteran columnist and an economic historian He’s proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

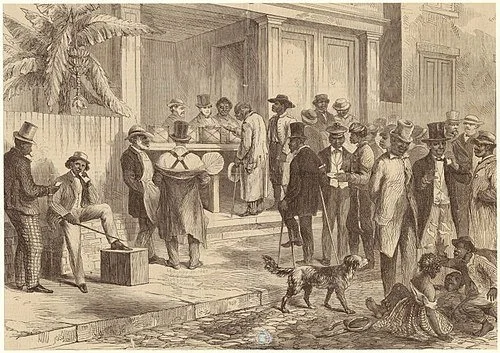

David Warsh: Competing with expansionist China while managing internal threats to our democracy

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I have, at least since 1989, been a believer that competition between the West and China is likely to dominate global history for the foreseeable future. By that I mean at least the next hundred years or so.

I am a reluctant convert to the view that the contest has arrived at a new and more dangerous phase. The increasing belligerence of Chinese foreign policy in the last few years has overcome my doubts.

It was a quarter century ago that I read World Economic Primacy: 1500-1990, by Charles P. Kindleberger. I held no economic historian in higher regard than CPK, but I raised an eyebrow at his penultimate chapter, “Japan in the Queue?” His last chapter, “The National Life Cycle,” made more sense to me, but even then wasn’t convinced that he had got the units of account or the time-scales right.

The Damascene moment in my case came last week after I subscribed to Foreign Affairs, an influential six-times-a-year journal of opinion published by the Council on Foreign Relations. Out of the corner of my eye, I had been following a behind-the-scenes controversy, engendered by an article in the magazine about what successive Republican and Democratic administrations thought they were doing as they engaged with China, starting with the surprise “opening” engineered by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger in 1971. I subscribed to Foreign Affairs to see what I had been missing.

In 2018, in “The China Reckoning,’’ the piece that started the row, foreign- policy specialists Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner had asserted that, for over fifty years, Washington had “put too much faith in its power to shape China’s trajectory.” The stance had been previously identified mainly with then-President Donald Trump. Both Campbell and Ely wound up in senior positions in the Biden administration, at the White House and the Pentagon.

In fact the proximate cause of my subscription was the most recent installment in this fracas. To read “The Inevitable Rivalry,’’ by John Mearsheimer, of the University of Chicago, an article in the November/December issue of the magazine, I had to pay the entry rate. His essay turned out to be a dud.

Had U.S. policymakers during the unipolar moment thought in terms of balance-of-power politics, they would have tried to slow Chinese growth and maximize the power gap between Beijing and Washington. But once China grew wealthy, a U.S.-Chinese cold war was inevitable. Engagement may have been the worst strategic blunder any country has made in recent history: there is no comparable example of a great power actively fostering the rise of a peer competitor. And it is now too late to do much about it.

Mearsheimer’s article completely failed to persuade me. Devotion to the religion he calls “realism” leads him to ignore two hundred years of Chinese history and the great foreign-policy lesson of the 20th Century: the disastrous realism of the 1919 Versailles Treaty that ended World War I and led to World War II, vs. the pragmatism of the Marshall Plan of 1947, which helped prevent World War III. There is no room for moral conduct is his version of realism. It is hardball all the way.

My new subscription led me to the archives, and soon to “Short of War,’’ by Kevin Rudd, which convinced me that China’s designs on Taiwan were likely to escalate, given President Xi Jinping’s intention to remain in power indefinitely. (Term limits were abolished on his behalf in 2018.) By 2035 he will be 82, the age at which Mao Zedong died. Mao had once mused that repossession of the breakaway island nation of Taiwan might take as long as a hundred years.

Beijing now intends to complete its military modernization program by 2027 (seven years ahead of the previous schedule), with the main goal of giving China a decisive edge in all conceivable scenarios for a conflict with the United States over Taiwan. A victory in such a conflict would allow President Xi to carry out a forced reunification with Taiwan before leaving power—an achievement that would put him on the same level within the CCP pantheon as Mao Zedong.

That led me in turn to “The World China Wants,’’ by Rana Mitter, a professor of Chinese politics and history at Oxford University. He notes that, at least since the global financial crisis of 2008, China’s leaders have increasingly presented their authoritarian style of governance as an end in and of itself, not a steppingstone to a liberal democratic system. That could change in time, she says.

To legitimize its approach, China often turns to history, invoking its premodern past, for example, or reinterpreting the events of World War II. China’s increasingly authoritarian direction under Xi offers only one possible future for the country. To understand where China could be headed, observers must pay attention to the major elements of Chinese power and the frameworks through which that power is both expressed and imagined.

The ultimate prize of my Foreign Affairs reading day was “The New Cold War,’’ a long and intricately reasoned article in the latest issue by Hal Brands, of Johns Hopkins University, and John Lewis Gaddis, of Yale University, about the lessons they had drawn from a hundred and fifty years of competition among great powers. I especially agreed with their conclusion:

As [George] Kennan pointed out in the most quoted article ever published in these pages, “Exhibitions of indecision, disunity and internal disintegration within this country” can “have an exhilarating effect” on external enemies. To defend its external interests, then, “the United States need only measure up to its own best traditions and prove itself worthy of preservation as a great nation.”

Easily said, not easily done, and therein lies the ultimate test for the United States in its contest with China: the patient management of internal threats to our democracy, as well as tolerance of the moral and geopolitical contradictions through which global diversity can most feasibly be defended. The study of history is the best compass we have in navigating this future—even if it turns out to be not what we’d expected and not in most respects what we’ve experienced before.

That sounded right to me. Worries exist in a hierarchy: leadership of the Federal Reserve Board; the U.S. presidential election in 2024; the stability of the international monetary system; arms races of various sorts; climate change. Subordinating all these to the China problem will take time.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Trump keeps grifting; what next for Bloomberg?

Bloomberg’s headquarters tower on Lexington Avenue in Midtown Manhattan

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Donald Trump is planning to start a social-media network to compete with Twitter and Facebook, which have kicked him off their platforms. Digital World Acquisition Co. (DWAC), a so-called blank-check company, or SPAC, plans to fund Truth Social, Trump’s venture, with the $290 million that the company has raised from institutional investors, merging itself out of existence in the process. DWAC shares closed Friday at $94, a ten-fold increase over their initial offering price a few days before, having traded as high as $175 during the day. Trump’s alternative to Twitter is scheduled to launch next month.

But Truth Social seems unlikely to succeed.

Whatever the case, investors in what by then will be listed as Trump Media & Technology Group will be able to continue trading with each other, after the DWAC evanesces. The Wall Street Journal on Oct. 23 explained the road ahead. Bloomberg Opinion columnist Matt Levine commented, “If you are in the business of raising money to fund a social media company that you haven’t built yet and perhaps never will, the SPAC format has a real appeal.” In other words, Trump Social is another example of pure Trump fleece.

Meanwhile, there is Bloomberg L.P., almost the polar opposite of what Trump intends.

By now the Bloomberg story is well known, thanks to Eleanor Randolph’s excellent 2019 biography: how the 38-year-old Salomon Brothers partner was first banished to the computer room, then squeezed out of the firm altogether after a merger, only to surface two years later, aided by MerrillLynch (which still owns 12 percent of the company), with a proprietary bond-price data base and a package of related computer analytics, a system he first called Market Master.

Bloomberg terminal-subscription growth (at $24,000 a year apiece!) was so explosive in the ‘80s that, by 1990, Bloomberg was able to start a news service, hiring Matthew Winkler, the WSJ reporter who had covered his rise, as its first editor-in-chief. Bundled with Bloomberg analytics, Bloomberg News grew by leaps and bounds as well, until it rivaled powerhouse Reuters, the world’s oldest and largest news agency. John Micklethwait, editor of The Economist, replaced Winkler and continued to build its staff, hiring newspaper veterans and various media stars, But Bloomberg News’s product remains almost entirely online, which limits its influence in some critical dimensions. I read it there; it is not the same as print.

True, there is Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg bought the time-honored title from McGraw-Hill in 2009, at a fire-sale price, inserted his name, and gave it a complete makeover. The magazine arrives via postal mail, one day or another each week, and often many more days go by before I open its cover. When I do, I am always impressed by its contents, especially the decent, moderate Republican tone of its editorials, in sharp contrast to the over-the-top WSJ editorial page. But there is something about the weekly magazine format that no longer works, at least for those lacking leisure. The Economist fares only a little bit better at my breakfast table.

Bloomberg, 79, was elected three time mayor of New York City. He ran unsuccessfully for president in 2020. It is well-documented that he has long hoped to buy a newspaper – either the WSJ or the NYT. I’d like to know something about Donald Graham’s discussions with Bloomberg before Graham decided to sell The Washington Post to Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos at a bargain price. My hunch is that Bezos’s four children loomed large in his thinking (Graham was a third-generation steward of what after 75 years had become a family paper.)

Today Bloomberg is worth $60 billion. So why doesn’t he start a print newspaper? Name it for something other than himself. Model it, loosely, on the Financial Times. Print it at first in a dozen US cities, where dense home-delivery audiences exist. He is still young enough to enjoy presiding over an influential print paper for a dozen years or more. He already employs most of a first-rate staff. Moreover, he has two daughters, Georgina and Emma, living interesting lives, waiting in the wings.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicsprincipals.com, where this column originated.

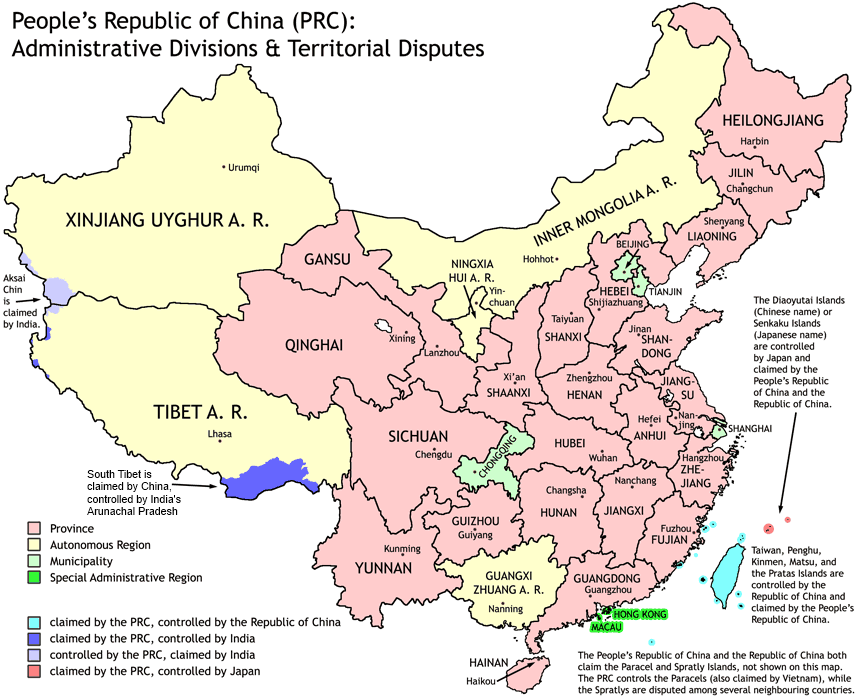

David Warsh: Pinning things down using history

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In Natural Experiments of History, a collection of essays published a decade ago, editors Jared Diamond and James Robinson wrote, “The controlled and replicated laboratory experiment, in which the experimenter directly manipulates variables, is often considered the hallmark of the scientific method” – virtually the only approach employed in physics, chemistry, molecular biology.

Yet in fields considered scientific that are concerned with the past – evolutionary biology, paleontology, historical geology, epidemiology, astrophysics – manipulative experiments are not possible. Other paths to knowledge are therefore required, they explained, methods of “observing, describing, and explaining the real world, and of setting the individual explanations within a larger framework “– of “doing science,” in other words.

Studying “natural experiments” is one useful alternative, they continued – finding systems that are similar in many ways but which differ significantly with respect to factors whose influence can be compared quantitatively, aided by statistical analysis.

Thus this year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences recognizes Joshua Angrist, 61, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; David Card, 64, of the University of California, Berkeley; and Guido Imbens, 58, of Stanford University, “for having shown that natural experiments can answer central questions for society.”

Angrist, burst on the scene in in 1990, when “Lifetime Earnings and the Vietnam Era Draft Lottery: Evidence from Social Security administrative records” appeared in the American Economic Review. The luck of the draw had, for a time, determined who would be drafted during America’s Vietnam War, but in the early 1980s, long after their wartime service was ended, the earnings of white veterans were about 15 percent less than the earnings of comparable nonveterans, Angrist showed.

About the same time, Card had a similar idea, studying the impact on the Miami labor market of the massive Mariel boatlift out of Cuba, but his paper appeared in the less prestigious Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Card then partnered with his colleague, Alan Krueger, to search for more natural experiments in labor markets. Their most important contribution, a careful study of differential responses in nearby eastern Pennsylvania to a minimum-wage increase in New Jersey, appeared as was Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage (Princeton, 1994). Angrist and Imbens, meanwhile, mainly explored methodological questions.

Given the rule that no more than three persons can share a given Nobel prize, and the lesser likelihood that separate prizes might be given in two different years, Krueger’s tragic suicide, in 2019, rendered it possible to cite, in a single award, Card, for empirical work, and Angrist and Imbens, for methodological contributions.

Princeton economist Orley Ashenfelter, who, with his mentor Richard Quandt, also of Princeton, more or less started it all, told National Public Radio’s Planet Money that “It’s a nice thing because the Nobel committee has been fixated on economic theory for so long, and now this is the second prize awarded for how economic analysis is now primarily done. Most economic analysis nowadays is applied and empirical.” [Work on randomized clinical trials was recognized in 2019.]

In 2010 Angrist and Jörn-Staffen Pischke described the movement as “the credibility revolution.” And in the The Age of the Applied Economist: the Transformation of Economics since the 1970s. (Duke, 2017), Matthew Panhans and John Singleton wrote that “[T]he missionary’s Bible today is less Mas-Colell et al and more Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion (Angrist and Pischke, Princeton, 2011)

Maybe so. Still, many of those “larger frameworks” must lie somewhere ahead.

“History,’’ by Frederick Dielman (1896)

That Dale Jorgenson, of Harvard University, would be recognized with a Nobel Prize was an all but foregone conclusion as recently as twenty years ago. Harvard University had hired him away from the University of California at Berkeley in 1969, along Zvi Griliches, from the University of Chicago, and Kenneth Arrow, from Stanford University (the year before). Arrow had received the Clark Medal in 1957, Griliches in 1965; Jorgenson was named in 1971. “[H]e is preeminently a master of the territory between economics and statistics, where both have to be applied in the study of concrete problems.” said the citation. With John Hicks, Arrow received the Nobel Prize the next year.

For the next thirty years, all three men brought imagination to bear on one problem after another. Griliches was named a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association in 1994; he died in 1999. Jorgenson, named a Distinguished Fellow in 2001, began an ambitious new project in 2010 to continuously update measures of output and inputs of capital, labor, energy, materials and services for individual industries. Arrow returned to Stanford in 1979 and died in 2017.

Call Jorgenson’s contributions to growth accounting “normal science” if you like – mopping up, making sure, improving the measures introduced by Simon Kuznets, Ricard Stone, and Angus Deaton. It didn’t seem so at the time. The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on.

xxx

Where are the women in economics, asked Tim Harford, economics columnist of the Financial Times the other day. They are everywhere, still small in numbers, especially at senior level, but their participation is steadily growing. AEA presidents include Alice Rivlin (1986); Anne Krueger (1996); Claudia Goldin (2013); Janet Yellen (2020); Christina Romer (2022), and Susan Athey, president elect (2023). Clark medals have been awarded to Athey (2007), Esther Duflo (2010), Amy Finkelstein (2012), Emi Nakamura (2019), and Melissa Dell (2020).

Not to mention that Yellen, having chaired the Federal Reserve Board for four years, today is secretary of the Treasury; that Fed governor Lael Brainerd is widely considered an eventual chair; that Cecilia Elena Rouse chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers; that Christine Lagarde is president of European Central Bank; and that Kristalina Georgieva is managing director of the International Monetary Fund, for a while longer, at least.

The latest woman to enter these upper ranks is Eva Mörk, a professor of economics at Uppsala University, apparently the first female to join the Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences that recommends the Economics Sciences Prize, the last barrier to fall in an otherwise egalitarian institution. She stepped out from behind the table in Stockholm last week to deliver a strong TED-style talk (at minutes 5:30-18:30 in the recording) about the whys and wherefores of the award, and gave an interesting interview afterwards.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Goldin's marriage manual for the next generation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

For many people, the COVID-19 pandemic has been an eighteen-month interruption. Survive it, and get back to work. For those born after 1979, it may prove to have been a new beginning. Women and men born in the 21st Century may have found themselves beginning their lives together in the midst of yet another historic turning point.

That’s the argument that Claudia Goldin advances in Career and Family: Women’s Century-long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021). As a reader who has been engaged as a practitioner in both career and family for many years, I aver that this is no ordinary book. What does greedy work have to do with it? And why is the work “greedy,” instead of “demanding” or “important?” Good question, but that is getting ahead of the story.

Goldin, a distinguished historian of the role of women in the American economy, begins her account in 1963, when Betty Friedan wrote a book about college-educated women who were frustrated as stay-at-home moms. Their problem, Friedan wrote, “has no name.” The Feminine Mystique caught the beginnings of a second wave of feminism that continues with puissant force today. Meanwhile, Goldin continues, a new “problem with no name” has arisen:

Now, more than ever, couples of all stripes are struggling to balance employment and family, their work lives and home lives. As a nation, we are collectively waking up to the importance of caregiving, to its value, for the present and future generations. We are starting to fully realize its cost in terms of lost income, flattened careers, and trade-offs between couples (heterosexual and same sex), as well as the particularly strenuous demands on single mothers and fathers. These realizations predated the pandemic but have been brought into sharp focus by it.

A University of Chicago-trained economist; the first woman tenured by Harvard’s economics department; author of five important books, including, with her partner, Harvard labor economist Lawrence Katz, The Race between Education and Technology (Harvard Belknap, 2010); recipient of an impressive garland of honors, among them the Nemmers award in economics; a former president of the American Economic Association: Goldin has written a chatty, readable sequel to Friedan, destined itself to become a paperback best-seller – all the more persuasive because it is rooted in the work of hundreds of other labor economists and economic historians over the years. Granted, Goldin is expert in the history of gender only in the United States; other nations will compile stories of their own. .

To begin with, Goldin distinguishes among the experiences of five roughly-defined generations of college-educated American women since the beginning of the twentieth century. Each cohort merits a chapter. The experiences of gay women were especially hard to pin down over the years, given changing norms.

In “Passing the Baton,” Goldin characterizes the first group, women born between 1878-97, as having had to choose between raising families and pursuing careers. Even the briefest biographies of the lives culled from Notable American Women make interesting reading: Jeannette Rankin, Helen Keller, Margaret Sanger, Katharine McCormick, Pearl Buck, Katharine White, Sadie Alexander, Frances Perkins. But most of that first generation of college women never became more prominent than as presidents of the League of Women Voters or the Garden Club. They were mothers and grandmothers the rest of their lives.

In “A Fork in the Road,” her account of the generation born between 1898 and 1923, Goldin dwells on 75-year-old Margaret Reid, whom she frequently passed at the library as a graduate student at Chicago, where Reid had earned a Ph.D. in in economics in 1934. (They never spoke; Goldin, a student of Robert Fogel, was working on slavery then.) Otherwise, this second generation was dominated by a pattern of jobs, then family. The notable of this generation tend to be actresses – Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Rosalind Russell, Barbara Stanwyck – sometimes playing roles modeled on real-world careers, as when Hepburn played a world-roving journalist resembling Dorothy Thompson in Woman of the Year.

In “The Bridge Group,” Goldin discusses the generation born between 1924-1943, who raised families first and then found jobs – or didn’t find jobs. She begins by describing what it was like to read Mary McCarthy’s novel, The Group (in a paper-bag cover), as a 17-year-old commuting from home in East Queens to a summer job in Greenwich Village. It was a glimpse of her parents’ lives – the dark cloud of the Great Depression that hung over w US in the Thirties, the hiring bars and marriage bar that turned college-educated women out of the work-force at the first hint of second income.

“The Crossroads with Betty Friedan” is about the Fifties and the television shows, such as I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, Leave It to Beaver and Father Knows Best that, amid other provocations, led Betty Friedan to famously ask, “Is that all there is?” Between the college graduation class of 1957 and the class of 1961, Goldin finds, in an enormous survey by the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Labor Department, an inflection point. The winds shift, the mood changes. Women in small numbers begin to return to careers after their children are grown: Jeane Kirkpatrick, Erma Bombeck, Phyllis Schafly, Janet Napolitano and Goldin’s own mother, who became a successful elementary school principal. Friedan had been right, looking backwards, Goldin concludes, but wrong about what was about to happen.

In “The Quiet Revolution,” members of the generation born between 1944-1957 set out to pursue careers and then, perhaps, form families. The going is hard but they keep at it. The scene is set with a gag from the Mary Tyler Moore Show in 1972. Mary is leaving her childhood home with her father, on her way to her job as a television news reporter. He mother calls out, “Remember to take your pill, dear.” Father and daughter both reply, “I will.” Father scowls an embarrassed double-take. The show’s theme song concludes, “You’re going to make it after all.” The far-reaching consequences of the advent of dependable birth control for women’s new choices are thoroughly explored. This is, after all, Goldin’s own generation.

“Assisting the Revolution,” about the generation born between1958-78, is introduced by a recitation of the various roles played by Saturday Night Live star Tina Fey – comedian, actor, writer. Group Five had an easier time of it. They were admitted in increasing numbers to professional and graduate schools. They achieved parity with men in colleges and surpassed them in numbers. They threw themselves into careers. “But they had learned from their Group Four older sisters that the path to career must leave room for family, as deferral could lead to no children,” Golden writes. So they married more carefully and earlier, chose softer career paths, or froze their eggs. Life had become more complicated.

In her final chapters – “Mind the Gap,” “The Lawyer and the Pharmacist” and “On Call” – Goldin tackles the knotty problem. The gender earnings gap has persisted over fifty years, despite the enormous changes that have taken place. She explores the many different possible explanations, before concluding that the difference stems from the need in two-career families for flexibility – and the decision, most often by women, to be on-call, ready to leave the office for home. Children get sick, pipes break, school close for vacation, the baby-sitter leaves town.

The good news is that the terms of relationships are negotiable, not between equity-seeking partners, but with their employers as well. The offer of parental leave for fathers is only the most obvious example. Professional firms in many industries are addicted to the charrette – a furious round of last-minute collaborative work or competition to meet a deadline. Such customs can be given a name and reduced. Firms need to make a profit, it is true, but the name of the beast, the eighty-hour week, is “greedy work.”

It is up the members of the sixth group, their spouses and employers, to further work out the terms of this deal. The most intimate discussions in the way ahear will occur within and among families. Then come board rooms, labor negotiations, mass media, social media, and politics. Even in its hardcover edition, Career and Family is a bargain. I am going home to start to assemble another photograph album – grandparents, parents, sibs, girlfriends, wife, children, and grandchildren – this one to be an annotated family album.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

A "Wife Wanted" ad in an 1801 newspaper

"N.B." means "note well".

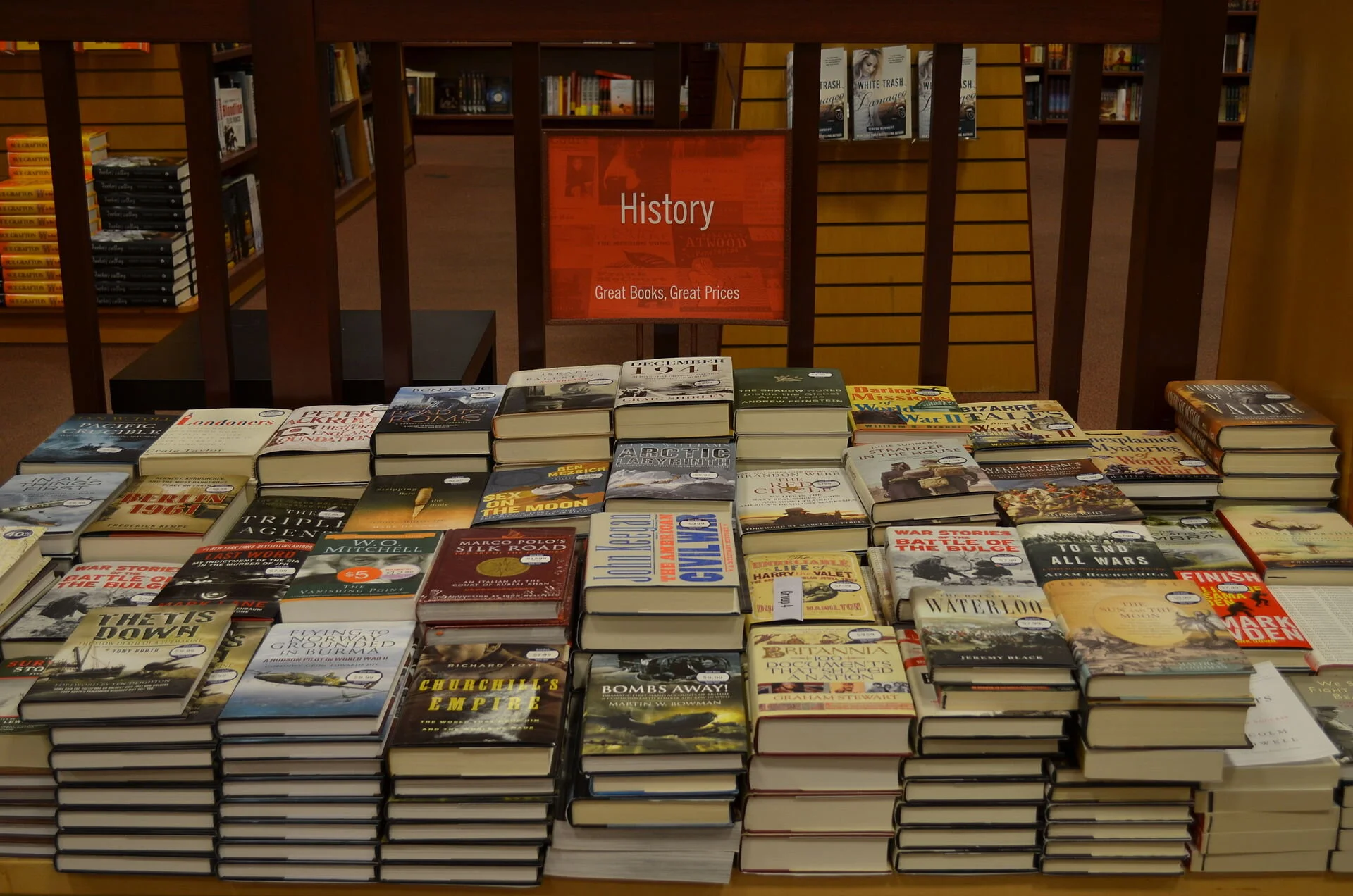

David Warsh: The exciting lives of former newspapermen

— Photo by Knowtex

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

After the Internet laid waste to old monopolies on printing presses and broadcast towers, new opportunities arose for inhabitants of newsrooms. That much I knew from personal experience. With it in mind, I have been reading Spooked: The Trump Dossier, Black Cube, and the Rise of Private Spies (Harper, 2021), by Barry Meier, a former reporter for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Meier also wrote Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Story of Addiction and Death (Rodale, 2003), the first book to dig in to the story of the Sackler family, before Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty (Doubleday, 2021), by New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe, eclipsed it earlier this year. In other words, Meier knows his way around. So does Lincoln Millstein, proprietor of The Quietside Journal, a hyperlocal Web site covering three small towns on the southwest side of Mt. Desert Island, in Downeast Maine.

Meier’s book is essentially a story about Glenn Simpson, a colorful star investigative reporter for the WSJ who quit in 2009 to establish Fusion GPS, a private investigative firm for hire. It was Fusion GPS that, while working first for Republican candidates in early 2016, then for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, hired former MI6 agent Christopher Steele to investigate Donald Trump’s activities in Russia.

Meier, a careful reporter and vivid writer, doesn’t think much of Simpson, still less of Steele, but I found the book frustrating: there were too many stories about bad behavior in the far-flung private intelligence industry, too loosely stitched together, to make possible a satisfying conclusion about the circumstances in which the Steele dossier surfaced, other than information, proven or not, once assembled and packaged, wants to be free. William Cohan’s NYT review of Spooked was helpful: “[W]e are left, in the end, with a gun that doesn’t really go off.”

Meier did include in his book (and repeat in a NYT op-ed) a telling vignette about Fusion GPS co-founder Peter Fritsch, another former WSJ staffer who in his 15-year career at the paper had served as bureau chief in several cities around the world. At one point, Fritsch phones WSJ reporter John Carreyrou, ostensibly seeking guidance on the reputation of a whistleblower at a medical firm – without revealing that Fusion GPS had begun working for Elizabeth Holmes, of whose blood-testing start-up, Theranos, Carreyrou had begun an investigation.

Fritsch’s further efforts to undermine Carreyrou’s investigation failed. Simpson and Fritch tell their story of the Steele dossier in Crime in Progress (2019, Random House.) I’d like to someday read more personal accounts of their experiences in the private spy trade, I thought, as I put Spooked and Crime in Progress back on the shelf Given the authors’ new occupations, it doesn’t seem likely those accounts will be written.

By then, Meier’s story had got me thinking about Carreyrou himself. His brilliant reporting for the WSJ, and his 2018 best-seller, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (Knopf, 2018, led to Elizabeth Holmes’s trial on criminal charges that began last month in San Jose. Thanks to Twitter, I found, within an hour of its appearance, this interview with Carreyrou, now covering the trial online as an independent journalist.

My head spun at the thought of the leg-push and tradecraft required to practice journalism at these high altitudes. The changes wrought by the advent of the Web and social media have fundamentally expanded the business beyond the days when newspapers and broadcast news were the primary producers of news. In 1972, when I went to work for the WSJ, for example, the entire paper ordinarily contained only four bylines a day.

So I turned with some relief to The Quietside Journal, the Web site where retired Hearst executive Lincoln Millstein covers events in three small towns on Mt. Desert Island, Maine, for some 17,000 weekly readers. In an illuminating story about his enterprise, Millstein told Rick Edmonds, of the Poynter Institute, that he works six days a week, again employing pretty much the same skills he acquired when he covered Middletown, Conn., for The Hartford Courant forty years ago. (Millstein put the Economic Principals column in business in 1984, not long after he arrived as deputy business editor at The Boston Globe).

My case is different. Like many newspaper journalists in the 1980s, I worked four or five days a week at my day job and spent vacations and weekends writing books. I quit the day job in 2002, but kept the column and finished the book. (It was published in 2006 as Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery).

Economic Principals subscribers have kept the office open ever since; I gradually found another book to write; and so it has worked out pretty well. The ratio of time spent is reversed: four days a week for the book, two days for the column, producing, as best I can judge, something worth reading on Sunday morning. Eight paragraphs, sometimes more, occasionally fewer: It’s a living, an opportunity to keep after the story, still, as we used to say, the sport of kings.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Looking at a ‘three-pronged approach’ to global warming

Average surface air temperatures from 2011 to 2020 compared to the 1951-1980 average

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The most memorable theater scene I’ve ever witnessed was performed one summer evening long ago in a courtyard at the University of Chicago. The play was Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, a complicated work from the 1920s about the relationship between authors, the stories they tell, and the audiences they seek.

At one point, a company of actors, having been interrupted in their rehearsal by a family of six seeking a playwright to tell their story, are bickering furiously with their interrupters when, at the opposite end of courtyard, two key members of the family had slipped away, to be suddenly illuminated by a spotlight as they stood beneath a tree to make a telling point: their story was as important as the play – maybe more. The act ended and the lights came up for intermission.

That was the technique known as up-staging with a vengeance, an abrupt diversion of attention from one focal point to another.

I remembered the experience after reading Three Prongs for Prudent Climate Policy, by Joseph Aldy and Richard Zeckhauser, both of the Harvard Kennedy School, a sharply critical appraisal of the prevailing consensus on the prospects for controlling climate change. Delivered originally as Zeckhauser’s keynote address to the Southern Economic Association in 2019, you can read it here for free at Resources for the Future. Its thirty pages are not easy reading, but they are formidably clear-headed, and I doubt that you can find a better roundup of the situation that the leaders are discussing blah-blah-blah next month at the U.N.’s Climate Change Conference in Glasgow.

The possibility of greenhouse warming was broached 125 years ago by the Swedish physical chemist Svante Arrhenius. The specific effect was discovered by Roger Revelle in 1957, and the growing problem brought into sharp focus in the U.S. by climate scientist James Hansen in Senate testimony in 1988. It has taken thirty years to reach a broad global consensus about the first of Aldy and Zeckhauser’s three prongs.

“For three decades, advocates for climate change policy have simultaneously emphasized the urgency of taking ambitious actions to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and provided false reassurances of the feasibility of doing so. The policy prescription has relied almost exclusively on a single approach: reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other GHGs. Since 1990, global CO₂ emissions have increased 60 percent, atmospheric CO₂ concentrations have raced past 400 parts per million, and temperatures increased at an accelerating rate. The one-prong strategy has not worked.’’

A second prong, adaptation, has been added in to most menus in recent years: everything from design changes (moving electric installations to roofs instead of basements) to seawalls, marsh expansions, and resettlement of populations. Adaptations are expensive. A six-mile long sea barrier with storm surge gates might protect New York City from climate change, but would take 25 years to build.

A third prong of climate policy ordinarily receives little attention. This is amelioration, or “the ‘G’-word,” as the chair of British Royal Society report dubbed it in 2009, meaning the broad topic of geo-engineering. For a dozen years, it was thought possible that fertilizing the southern oceans might grow more plankton, absorb more atmospheric carbon, and feed more fish. Experiments were not encouraging. The technique considered most promising today is solar-radiation management, meaning creating atmospheric sun-screens for the planet. The third prong is by far the last expensive of the three. It is also the most alarming.

Ever since “the year without a summer” of 1816, it has been known that volcanic eruptions, spewing sulfur particles into the atmosphere, produce worldwide net cooling effects. Climate scientists now believe that airplanes could achieve the same effect by spraying chemical aerosols at high altitudes into the atmosphere. The trouble is that very little is known with any certainty about the feasibility of such measures, much less their ecological effects on life below.

Many environmentalists fear that the very act of public discussion of solar- radiation management will further bad behavior – create “moral hazard” in the language of economists. Glib talk by enthusiasts of economic growth about cheap and easy redress of climate problems will diminish the imperative to reduce emissions of greenhouse governance, some say. Others think that sulfur in the air above would accelerate acidification in the oceans below. Still others doubt that global governance could be achieved, since such measures would not offset climate change equally in all regions, Rogue nations might undertake projects that they hoped would have purely local effects.

Aldy and Zeckhauser argue that bad behavior may in fact be flowing in the opposite direction. Climate change is an emotional issue; circumspection with respect to solar-radiation management is the usual stance; opposition to research is often fierce. As a result, very little has been performed. One of the first outdoor experiments – a dry run – was shut down earlier this year.

In his 2018 Nobel lecture, William Nordhaus, of Yale University, saw the problem somewhat differently.

“To me, geo-engineering resembles what doctors call ‘salvage therapy’– a potentially dangerous treatment to be used when all else fails. Doctors prescribe salvage therapy for people who are very ill and when less dangerous treatments are not available. No responsible doctor would prescribe salvage therapy for a patient who has just been diagnosed with the early stage of a treatable illness. Similarly, no responsible country should undertake geo-engineering as the first line of defense against global warming.’’

After a while, it seemed to me that the debate over global warming does indeed bear more than a little resemblance to what goes on in Pirandello’s play. Three possible policy avenues exist. The first is talked about constantly: the second enters the conversation more frequently than before. The third is all but excluded from mainstream discussion.

It’s not so much about what stage of a treatable illness you think we’re in. Public opinion around the world will determine that, as time goes by. It’s about whether the question of desperate measures should be systematically explored at all. The three-pronged approach is a policy in search of an author.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

David Warsh: Prepare for multigenerational contest between China and the West

China’s national emblem

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

China is building missile silos in the Gobi Desert. The U.S. has agreed to provide nuclear-submarine technology to Australia, enraging the French, who are building a dozen diesel subs that they had expected to sell to the Aussies. Xi Jinping last week rejected Joe Biden’s suggestion that the two arrange a face-to-face meeting to discuss their differences. Clearly, the U.S. “pivot” to the Pacific is well underway. Taiwan is the new hotspot, not to mention the Philippines and Japan.

The competition between China and the West is a contest, not a cold war. Financial Times columnist Philip Stephens was the first in the circle of those whom I read to make this point. “The Soviet Union presented at once a systemic and an existential threat to the West,” he wrote. “China undoubtedly wants to establish itself as the world’s pre-eminent power, but it is not trying to convert democracies to communism….” The U.S. is not trying to “contain” China so much as to constrain its actions. He continued,

Beijing and Moscow want a return to a nineteenth century global order where great powers rule over their own distinct spheres of influence. If the habits and the institutions created since 1945 mean anything, it has been the replacement of that arrangement with the international rule of law.

I’m not quite sure what Stephens means by “the international rule of law.” The constantly changing Western traditions of freedom of action and thought? Is it true, as George Kennan told Congress in 1972, that the Chinese language contains no word for freedom? Is it possible that Chinese painters produced no nudes before the 20th Century?

The co-evolution of cultures between China and the West has been underway for 4,000 years, proceeding at a lethargic pace for most of that time. While the process has recently assumed a breakneck pace, it can be expected to continue for many, many generations before the first hints of consensus develop about a direction of change.

A hundred years? Three hundred? Who knows? Already there is conflict. There may eventually be blood, at least in some corners of the Earth. But the world has changed so much since 1945 that “cold war” is no longer a useful apposition. The existential threat today is climate change.

China’s cultural heritage is not going to fade away, as did Marxist-Leninism. The script of that drama, written in Europe in the 19th Century, has lost much of its punch. Vladimir Putin has embraced the Russian Orthodox Church as a source of moral authority. Xi Jinping has evoked the egalitarian idealism of Mao Zedong in cracking down on China’s high-tech groups and rock stars, and strictly limiting the time its children are allowed to play video games.

But what is the Western tradition of “rule of law” that presumes to become truly international, eventually? Expect an answer some other day. Meanwhile, I’m cooking pancakes for my Somerville grandchildren.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Resurgent feminist art

“People Have Anxiety about Ambiguity” (collage), by Liza Basso, in the group show “Re Sisters: Speaking Up; Speaking Out ,’’ at Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., Sept. 9-Oct 10.

The gallery says:

“The current political climate has put women’s rights and civil rights at risk. This exhibition is meant to bring attention to the recent resurgence in feminist art and its connection to activism and politics, as women face rollbacks in reproductive rights, the disproportionate effects of Covid 19, and a year that saw more women elected to political office than ever before. Through collections that delve into histories that are political, personal, and shared, ReSisters explores the experiences of women in a post-trump era.’’

David Warsh: Time to read ‘Three Days at Camp David’

The main lodge at Camp David

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The heart-wrenching pandemonium in Kabul coincided with the seeming tranquility of the annual central banking symposium at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. For the second year in a row, central bankers stayed home, amid fears of the resurgent coronavirus. Newspapers ran file photos of Fed officials strolling beside Jackson Lake.

Market participants are preoccupied with timing of the taper, the Fed’s plan to reduce its current high level of asset purchases. That is not beside the point, but neither is it the most important decision facing the Biden administration with respect to the conduct of economic policy. Whom to nominate to head the Federal Reserve Board for the next four years? For a glimpse of the background to that question, a good place to start is a paper from a a Bank of England workshop earlier in the summer

Central Bank Digital Currency in Historical Perspective: Another Crossroads in Monetary History, by Michael Bordo, of Rutgers University and the Hoover Institution, brings to mind the timeless advice of Yogi Berra: when you come to a crossroad, take it.

Bordo briefly surveys the history of money and banking. Gold, silver and copper coinage (and paper money in China) can be traced back over two millennia, he notes, but three key transformations can be identified in the five hundred years since Neapolitan banks began experimenting with paper money.

First, fiduciary money took hold in the 18th Century, paper notes issued by banks and ostensibly convertible into precious metal (specie) held in reserve by the banks. Fractional banking emerged, meaning that banks kept only as much specie in the till as they considered necessary to meet the ordinary ebb and flow of demands for redemption, leaving them vulnerable to periodic panics or “runs.” Occasional experiments with fiat money, issued by governments to pay for wars, but irredeemable for specie, generally proved spectacularly unsuccessful, Bordo says (American Continentals, French assignats).

Second, the checkered history of competing banks and their volatile currencies, led, over the course of a century, to bank supervision and monopolies on national currencies, overseen by central banks and national treasuries.

Third, over the course of the 17th to the 20th centuries, central banks evolved to take on additional responsibilities: marketing government debt; establishing payment systems; pursuing financial stability (and serving as lenders of last resort when necessary to halt panics); and maintaining a stable value of money. For a time, the gold standard made this last task relatively simple: to preserve the purchasing power of money, maintain a fixed price of gold. But as gold convertibly became ever-harder to manage, nations retreated from their fiduciary monetary systems in fits and starts. In 1971, they abandoned them altogether in favor of fiat money. It took about 20 years to devise central banking techniques with which to seek maintain stable purchasing power.

As it happens, the decision-making at the last fork in the road of the international currency and monetary system is laid out with great clarity and charm in a new book by Jeffrey Garten, Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy (2021, Harper) Garten spent a decade in government before moving to Wall Street. In 2006 he returned to strategic consulting in Washington, after about 20 years at Yale’s School of Management, ten of them as dean.

The special advantage of his book is how Garten brings to life the six major players at the Camp David meeting, Aug. 13-15, 1971 – Richard Nixon, John Connally, Paul Volcker, Arthur Burns, George Shultz, Peter Peterson and two supporting actors, Paul McCracken an Henry Kissinger – and explores their stated aims and private motives. The decision they took was momentous: to unilaterally quit the Bretton Woods system, to go off the gold standard, once and for all. It was a transition the United States had to make, Garten argues, and in this sense bears a resemblance to Afghanistan and the present day:

A bridge from the first quarter-century following [World War II] –where the focus was on rebuilding national economies that had been destroyed and on re-establishing a functional world economic system – to a new emvironment where power and responsibility among the allies had to be readjusted . with the burden on the United States being more equitably shared and with the need for multilateral cooperation to replace Washington’s unilateral dictates.

What about Nixon’s re-election campaign in 1972? Of course that had something to do with it; politics always has something to do with policy, Garten says. But one way or another, something had to be done to relieve pressure on the dollar. “The gold just wasn’t there” to continue, writes Garten.

The trouble is, as with all history, that was fifty years ago. What’s going on now?

Read, if you dare, the second half of Michael Bordo’s paper, for a concise summary of the money and banking issues we face. Their unfamiliarity is forbidding; their intricacy is great. The advantages of a digital system may be manifest. “Just as the history of multiple competing currencies led to central bank provision of currency,” Bordo writes, “ the present day rise of cryptocurrencies and stable coins suggests the outcome may also be a process of consolidation towards a central bank digital currency.”

But the choices that central bankers and their constituencies must make are thorny. Wholesale or retail? Tokens or distributed ledger accounts? Lodged in central banks or private institutions? Considerable work is underway, Bordo says, at the Bank of England, Sweden’s Riksbank, the Bank of Canada, the Bank for International Settlements, and the International Monetary Fund, but whatever research the Fed has undertaken, “not much of it has seen the light of day.”

Who best to help shepherd this new world into existence? The choice for the U.S. seems to be between reappointing Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, 68, to a second term, beginning in February, or nominating a Fed governor Lael Brainard, 59, to replace him. President Biden is reeling at the moment. I am no expert, but my hunch is that preferring Brainard to Powell is the better option overall, for both practical and political ends. After all, what infrastructure is more fundamental to a nation’s well-being than its place in the global system of money and banking?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

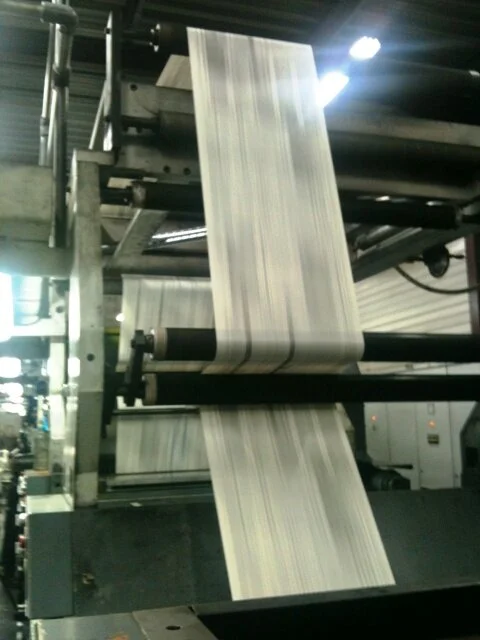

Language structures

“Figures of Speech” ((detail), etching and letterpress), by Somerville, Mass.-based Sarah Hulsey, in her show “Lexical Geometry,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Sept. 29-Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“Sarah Hulsey's work portrays the patterns and structures that comprise our universal instinct for language. In this body of work, she uses schematic forms and letterpress text to explore connections across the lexicon.’’

David Warsh: Of The Globe, John Kerry, Vietnam and my column

An advertisement for The Boston Globe from 1896.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It has taken six months, but with this edition, Economic Principals finally makes good on its previously announced intention to move to Substack publishing. What took so long? I can’t blame the pandemic. Better to say it’s complicated. (Substack is an online platform that provides publishing, payment, analytics and design infrastructure to support subscription newsletters.)

EP originated in 1983 as columns in the business section of The Boston Sunday Globe. It appeared there for 18 years, winning a Loeb award in the process. (I had won another Loeb a few years before, at Forbes.) The logic of EP was simple: It zeroed in on economics because Boston was the world capital of the discipline; it emphasized personalities because otherwise the subject was intrinsically dry (hence the punning name). A Tuesday column was soon added, dwelling more on politics, because economic and politics were essentially inseparable in my view.

The New York Times Co. bought The Globe in 1993, for $1.13 billion, took control of it in 1999 after a standstill agreement expired, and, in July 2001, installed a new editor, Martin Baron. On his second morning on the job, Baron instructed the business editor, Peter Mancusi, that EP was no longer permitted to write about politics. I didn’t understand, but tried to comply. I failed to meet expectations, and in January, Baron killed the column. It was clearly within his rights. Metro columnist Mike Barnicle had been cancelled, publisher Benjamin Taylor had been replaced, and editor Matthew Storin, privately maligned for having knuckled under too often to the Boston archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, retired. I was small potatoes, but there was something about The Globe’s culture that the NYT Co. didn’t like. I quit the paper and six weeks later moved the column online.

After experimenting with various approaches for a couple of years, I settled on a business model that resembled public radio in the United States – a relative handful of civic-minded subscribers supporting a service otherwise available for free to anyone interested. An annual $50 subscription brought an early (bulldog) edition of the weekly via email on Saturday night. Late Sunday afternoon, the column went up on the Web, where it (and its archive) have been ever since, available to all comers for free.

Only slowly did it occur to me that perhaps I had been obtuse about those “no politics” instructions. In October 1996, five years before they were given, I had raised caustic questions about the encounter for which then U.S. Sen. John Kerry (D.-Mass.) had received a Silver Star in Vietnam 25 years before. Kerry was then running for re-election, I began to suspect that history had something to do with Baron ordering me to steer clear of politics in 2001.

• ••

John Kerry had become well known in the early ‘70s as a decorated Navy war hero who had turned against the Vietnam War. I’d covered the war for two years, 1968-70, traveling widely, first as an enlisted correspondent for Pacific Stars and Stripes, then as a Saigon bureau stringer for Newsweek. I was critical of the premises the war was based on, but not as disparaging of its conduct as was Kerry. I first heard him talk in the autumn of 1970, a few months after he had unsuccessfully challenged the anti-war candidate Rev. Robert Drinan, then the dean of Boston College Law School, for the right to run against the hawkish Philip Philbin in the Democratic primary. Drinan won the nomination and the November election. He was re-elected four times.

As a Navy veteran, I was put off by what I took to be the vainglorious aspects of Kerry’s successive public statements and candidacies, especially in the spring of 1971, when in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relation Committee, he repeated accusations he had made on Meet the Press that thousands of atrocities amounting to war crimes had been committed by U.S. forces in Vietnam. The next day he joined other members of the Vietnam Veterans against the War in throwing medals (but not his own) over a fence at the Pentagon.

In 1972, he tested the waters in three different congressional districts in Massachusetts before deciding to run in one, an election that he lost. He later gained electoral successes in the Bay State, winning the lieutenant governorship on the Michael Dukakis ticket in 1982, and a U.S. Senate seat in 1984, succeeding Paul Tsongas, who had resigned for health reasons. Kerry remained in the Senate until 2013, when he resigned to become secretary of state. [Correction added]

Twenty-five years after his Senate testimony, as a columnist I more than once expressed enthusiasm for the possibility that a liberal Republican – venture capitalist Mitt Romney or Gov. Bill Weld – might defeat Kerry in the 1996 Senate election. (Weld had been a college classmate, though I had not known him.) This was hardly disinterested newspapering, but as a columnist, part of my job was to express opinions.

In the autumn of 1996, the recently re-elected Weld had challenged Kerry’s bid for a third term in the Senate, The campaign brought old memories to life. On Sunday Oct. 6, The Globe published long side-by-side profiles of the candidates, extensively reported by Charles Sennott.

The Kerry story began with an elaborate account of his experiences in Vietnam – the candidate’s first attempt. I believe, since 1971 to tell the story of his war. After Kerry boasted of his service during a debate 10 days later, I became curious about the relatively short time he had spent in Vietnam – four months. I began to research a column. Kerry’s campaign staff put me in touch with Tom Belodeau, a bow gunner on the patrol boat that Kerry had beached after a rocket was fired at it to begin the encounter for which he was recognized with a Silver Star.

Our conversation lasted half an hour. At one point, Belodeau confided, “You know, I shot that guy.” That evening I noticed that the bow gunner played no part in Kerry’s account of the encounter in a New Yorker article by James Carroll in October 1996 – an account that seemed to contradict the medal citation itself. That led me to notice the citation’s unusual language: “[A]n enemy soldier sprang from his position not 10 feet [from the boat] and fled. Without hesitation, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Kerry leaped ashore, pursued the man behind a hootch and killed him, capturing a B-40 rocket launcher with a round in the chamber.” There are now multiple accounts of what happened that day. Only one of them, the citation, is official, and even it seems to exist in several versions. What is striking is that with the reference to the hootch, the anonymous author uncharacteristically seems to take pains to imply that nobody saw what happened.

The first column (“The War Hero”) ran Tues., Oct. 24. Around that time, a fellow former Swift Boat commander, Edward (Tedd) Ladd, phoned The Globe’s Sennott to offer further details and was immediately passed on to me. Belodeau, a Massachusetts native who was living in Michigan, wanted to avoid further inquiries, I was told. I asked the campaign for an interview with Kerry. His staff promised one, but day after day, failed to deliver. Friday evening arrived and I was left with the draft of column for Sunday Oct. 27 about the citation’s unusual phrase (“Behind the Hootch”). It included a question that eventually came to be seen among friends as an inside joke aimed at other Vietnam vets (including a dear friend who sat five feet away in the newsroom): Had Kerry himself committed a war crime, at least under the terms of his own sweeping indictments of 1971, by dispatching a wounded man behind a structure where what happened couldn’t be seen?

The joke fell flat. War crime? A bad choice of words! The headline? Even worse. Due to the lack of the campaign’s promised response, the column was woolly and wholly devoid of significant new information. It certainly wasn’t the serious accusation that Kerry indignantly denied. Well before the Sunday paper appeared, Kerry’s staff apparently knew what it would say. They organized a Sunday press conference at the Boston Navy Yard, which was attended by various former crew members and the admiral who had presented his medal. There the candidate vigorously defended his conduct and attacked my coverage, especially the implicit wisecrack the second column contained. I didn’t learn about the rally until late that afternoon, when a Globe reporter called me for comment.

I was widely condemned. Fair enough: this was politics, after all, not beanbag. (Caught in the middle, Globe editor Storin played fair throughout with both the campaign and me). The election, less than three weeks away, had been refocused. Kerry won by a wider margin than he might have otherwise. (Kerry’s own version of the events of that week can be found on pp. 223-225 of his autobiography.)

• ••

Without knowing it, I had become, in effect, a charter member of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. That was the name of a political organization that surfaced in May 2004 to criticize Kerry, in television advertisements, on the Web, and in a book, Unfit for Command. What I had discovered in 1996 was little more than what everyone learned in 2004 – that some of his fellow sailors disliked Kerry intensely. In conversations with many Swift Boat vets over the year or two after the columns, I learned that many bones of contention existed. But the book about the recent history of economics I was finishing and the online edition of EP that kept me in business were far more important. I was no longer a card-carrying member of a major news organization, so after leaving The Globe I gave the slowly developing Swift Boat story a good leaving alone. I spent the first half of 2004 at the American Academy in Berlin.

Whatever his venial sins, Kerry redeemed himself thoroughly, it seems to me, by declining to contest the result of the 2004 election, after the vote went against him by a narrow margin of 118,601 votes in Ohio. He served as secretary of state for four years in the Obama administration and was named special presidential envoy for climate change, a Cabinet-level position, by President Biden,

Baron organized The Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Spotlight coverage of Catholic Church secrecy about sexual abuse by priests, and it turned into a world story and a Hollywood film. In 2013 he became editor of The Washington Post and steered a steady course as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos acquired the paper from the Graham family and Donald Trump won the presidency and then lost it. Baron retired in February. He is writing a book about those years.

But in 2003, John F. Kerry: The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best was published by PublicAffairs Books, a well-respected publishing house whose founder, Peter Osnos, had himself been a Vietnam correspondent for The Washington Post. Baron, The Globe’s editor, wrote in a preface, “We determined… that The Boston Globe should be the point of reference for anyone seeking to know John Kerry. No one should discover material about him that we hadn’t identified and vetted first.”

All three authors – Michael Kranish, Brian Mooney, Nina Easton – were skilled newspaper reporters. Their propensity to careful work appears on (nearly) every page. Mooney and Kranish I considered I knew well. But the latter, who was assigned to cover Kerry’s early years, his upbringing, and his combat in Vietnam, never spoke to me in the course of his reporting. The 1996 campaign episode in which I was involved is described in three paragraphs on page 322. The New Yorker profile by James Carroll that prompted my second column isn’t mentioned anywhere in the book; and where the Silver Star citation is quoted (page 104), the phrase that attracted my attention, “behind the hootch,” is replaced by an ellipsis. (An after-action report containing the phrase is quoted on page 102.)

Nor did Baron and I ever speak of the matter. What might he have known about it? He had been appointed night editor of The Times in 1997, last-minute assessor of news not yet fit to print; I don’t know whether he was already serving in that capacity in October 1996, when my Globe columns became part of the Senate election story. I do know he commissioned the project that became the Globe biography in December, 2001, a few weeks before terminating EP.

Kranish today is a national political investigative reporter for The Washington Post. Should I have asked him about his Globe reporting, which seems to me lacking in context? I think not. (I let him know this piece was coming; I hope that eventually we’ll talk privately someday.) But my subject here is how The Globe’s culture changed after NYT Co. acquired the paper, so I believe his incuriosity and that of his editor are facts that speak for themselves.

Baron’s claims of authority in his preface to The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best strike me as having been deliberately dishonest, a calculated attempt to forestall further scrutiny of Kerry’s time in Vietnam. In this Baron’s book failed. It is a far more careful and even-handed account than Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War (Morrow, 2004), historian Douglas Brinkley’s campaign biography. Mooney’s sections on Kerry’s years in Massachusetts politics are especially good. But as the sudden re-appearance of the Vietnam controversy in 2004 demonstrated, The Globe’s account left much on the table.

• ••

I mention these events now for two reasons. The first is that the Substack publishing platform has created a path that did not exist before to an audience – in this case several audiences – concerned with issues about which I have considerable expertise. The first EP readers were drawn from those who had followed the column in The Globe. Some have fallen away; others have joined. A reliable 300 or so annual Bulldog subscriptions have kept EP afloat.

Today, with a thousand online columns and two books behind me – Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton, 2006) and Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years (CreateSpace, 2018) – and a third book on the way, my reputation as an economic journalist is better-established.

The issues I discuss here today have to do with aspirations to disinterested reporting and open-mindedness in the newspapers I read, and, in some cases, the failure to achieve those lofty goals. I have felt deeply for 25 years about the particular matters described here; I was occasionally tempted to pipe up about them. Until now, the reward of regaining my former life as a newsman by re-entering the discussion never seemed worth the price I expected to pay.

But the success of Substack says to writers like me, “Put up or shut up.” After the challenge it posed dawned in December, I perked up, then hesitated for several months before deciding to leave my comfortable backwater for a lively and growing ecosystem. Newsletter publishing now has certain features in common with the market for national magazines that emerged in the U.S. in the second half of the 19th Century – a mezzanine tier of journalism in which authors compete for readers’ attention. In this case, subscribers participate directly in deciding what will become news.

The other reason has to do with arguments recently spelled out with clarity and subtlety by Jonathan Rauch in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth (Brookings, 2021). Rauch gets the Swift Boat controversy mostly wrong, mixing up his own understanding of it with its interpretation by Donald Trump, but he is absolutely correct about the responsibility of the truth disciplines – science, law, history and journalism – to carefully sort out even the most complicated claims and counter-claims that endlessly strike sparks in the digital media.

Without the places where professionals like experts and editors and peer reviewers organize conversations and compare propositions and assess competence and provide accountability – everywhere from scientific journals to Wikipedia pages – there is no marketplace of ideas; there are only cults warring and splintering and individuals running around making noise.

EP exists mainly to cover economics. This edition has been an uncharacteristically long (re)introduction. My interest in these long-ago matters is strongly felt, but it is a distinctly secondary concern. I expect to return to these topics occasionally, on the order of once a month, until whatever I have left to say has been said: a matter of ten or twelve columns, I imagine, such as I might have written for the Taylor family’s Globe.