David Warsh: Trump keeps grifting; what next for Bloomberg?

Bloomberg’s headquarters tower on Lexington Avenue in Midtown Manhattan

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Donald Trump is planning to start a social-media network to compete with Twitter and Facebook, which have kicked him off their platforms. Digital World Acquisition Co. (DWAC), a so-called blank-check company, or SPAC, plans to fund Truth Social, Trump’s venture, with the $290 million that the company has raised from institutional investors, merging itself out of existence in the process. DWAC shares closed Friday at $94, a ten-fold increase over their initial offering price a few days before, having traded as high as $175 during the day. Trump’s alternative to Twitter is scheduled to launch next month.

But Truth Social seems unlikely to succeed.

Whatever the case, investors in what by then will be listed as Trump Media & Technology Group will be able to continue trading with each other, after the DWAC evanesces. The Wall Street Journal on Oct. 23 explained the road ahead. Bloomberg Opinion columnist Matt Levine commented, “If you are in the business of raising money to fund a social media company that you haven’t built yet and perhaps never will, the SPAC format has a real appeal.” In other words, Trump Social is another example of pure Trump fleece.

Meanwhile, there is Bloomberg L.P., almost the polar opposite of what Trump intends.

By now the Bloomberg story is well known, thanks to Eleanor Randolph’s excellent 2019 biography: how the 38-year-old Salomon Brothers partner was first banished to the computer room, then squeezed out of the firm altogether after a merger, only to surface two years later, aided by MerrillLynch (which still owns 12 percent of the company), with a proprietary bond-price data base and a package of related computer analytics, a system he first called Market Master.

Bloomberg terminal-subscription growth (at $24,000 a year apiece!) was so explosive in the ‘80s that, by 1990, Bloomberg was able to start a news service, hiring Matthew Winkler, the WSJ reporter who had covered his rise, as its first editor-in-chief. Bundled with Bloomberg analytics, Bloomberg News grew by leaps and bounds as well, until it rivaled powerhouse Reuters, the world’s oldest and largest news agency. John Micklethwait, editor of The Economist, replaced Winkler and continued to build its staff, hiring newspaper veterans and various media stars, But Bloomberg News’s product remains almost entirely online, which limits its influence in some critical dimensions. I read it there; it is not the same as print.

True, there is Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg bought the time-honored title from McGraw-Hill in 2009, at a fire-sale price, inserted his name, and gave it a complete makeover. The magazine arrives via postal mail, one day or another each week, and often many more days go by before I open its cover. When I do, I am always impressed by its contents, especially the decent, moderate Republican tone of its editorials, in sharp contrast to the over-the-top WSJ editorial page. But there is something about the weekly magazine format that no longer works, at least for those lacking leisure. The Economist fares only a little bit better at my breakfast table.

Bloomberg, 79, was elected three time mayor of New York City. He ran unsuccessfully for president in 2020. It is well-documented that he has long hoped to buy a newspaper – either the WSJ or the NYT. I’d like to know something about Donald Graham’s discussions with Bloomberg before Graham decided to sell The Washington Post to Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos at a bargain price. My hunch is that Bezos’s four children loomed large in his thinking (Graham was a third-generation steward of what after 75 years had become a family paper.)

Today Bloomberg is worth $60 billion. So why doesn’t he start a print newspaper? Name it for something other than himself. Model it, loosely, on the Financial Times. Print it at first in a dozen US cities, where dense home-delivery audiences exist. He is still young enough to enjoy presiding over an influential print paper for a dozen years or more. He already employs most of a first-rate staff. Moreover, he has two daughters, Georgina and Emma, living interesting lives, waiting in the wings.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicsprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Ripen, then leave

The Big E is New England's collective state fair. On the Avenue of the States, each of the six New England States owns its own plot of land and a replica state house.

— Photo by John Phelan

“Springfield, Massachusetts, is place to be from. Talented people ripen in Springfield, then move away to bigger cities to make their fortune.’’

James C. O’Connell, in Pioneer Valley Reader (1995)

Main Street in Springfield in 1908, when industry and other business there was booming.

Llewellyn King: The masterful Queen Elizabeth II

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Bad news from the Royal Family: Queen Elizabeth II was advised last week by her doctors to rest and to cancel a trip to Northern Ireland and, sadly, to forego her nightly tipple, a martini.

The Queen is 95 and next year is her platinum jubilee – 70 years since she ascended the throne, on Feb. 6, 1952. Hers is an awesomely long rule -- the longest ever for a woman and right behind Louis XIV, whose reign of 72 years and 110 days is the longest in world history.

In Britain and around the world, there is a warmth of feeling and respect for Elizabeth that no other head of state or member of a royal family enjoys or is likely to acquire.

Of course, if you watch PBS, you will believe that every detail of the British Monarchy is of great interest and importance. It isn’t. There is reason to admire and revere the Queen as a great exemplar of an archaic office and as a superb public servant, but do we need to know all 1,000 years that lie behind the monarchy in Britain? They aren’t divine and most of today’s Royal Family, except for that doughty old lady, are dysfunctional.

But the public fascination with that whole tribe here and around the world goes on. Amazingly, there never seems to be any time when there isn’t something about the royals on PBS. Are we Americans all closet monarchists to the core? And British royalists at that.

The popular press tells us all about the transgressions of the younger royals and the BBC, and its fraternal American relation, PBS, tells us everything there is to be told about royal residences, carriages, jewels, historical oddities, clothes, and food. If you want to know about the crown the Queen wore for her coronation on June 2, 1953, I am sure that PBS has bought a program on it.

There are just two things about the Queen that we haven’t been told: How many matching hat and coat outfits does she own and how has she endured for so long the essential banality of royal public life? How many hundreds of thousands of wobbly women has she watched doing deep curtseys; how many heads of state has she chatted to about the weather; how many teachers has she congratulated on the nobility of their calling; how many tribal dancers has she watched and applauded?

That is dedication and she is still at it. Public servants worldwide take note.

The amazing thing is that while the privacy of other royals has been stripped bare – sometimes, as in the case of the late Princess Diana, with their encouragement -- the Queen has pulled off her entire reign by being public and obvious and yet aloof and private.

That is the stuff of royal leadership: Let everyone know you are on the job but remain remote, above and mysterious.

The Queen is masterful in her skill at being seen enough but heard hardly at all. It is a lesson that politicians with their endless appearances on television would be wise to learn: Less is more, except when it comes to the work, then more is more. For Elizabeth, during her extraordinarily long working life, more has always been more.

She is not a great intellectual. She doesn’t seem to have been a wholly successful mother and her private enjoyment, horses, is an elitist pursuit that is neither shared by many of her subjects at home nor her admirers around the world. I have heard her criticized by people close to her for these failings, but never by her globe-circling public.

The Royal Family is the greatest show on earth with all of its pomp, its ceremony and its foibles. But it is an enduring and endearing woman, who has kept the monarchy burnished through the years.

“I have in sincerity pledged myself to your service as so many of you are pledged to mine. Throughout all my life and with all my heart I shall strive to be worthy of your trust.”

That is what she said in a broadcast speech after her coronation at Westminster Abbey in 1953. And she has kept her word to the letter. God save the Queen. Long may she reign.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., among other places.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Clean unto generations

{“Stick the remnant of each bar of soap onto the next bar.} Theoretically, some of the atoms will remain in the bar until my very last shower. When I’m gone, my son can continue to use the bar as I have…and thus shall my zealous frugality be passed down from generation to generation as long as my descendants shall lather up.’’

From The Tightwad Gazette, founded in Leeds, Maine

Monument Hill in Leeds, Maine. There’s a Civil War monument barely visible here, left center.

Accents through time

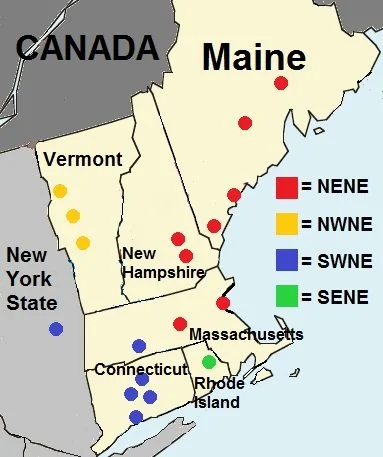

Northeastern (NENE), Northwestern (NWNE), Southwestern (SWNE), and Southeastern (SENE) New England English, as mapped by the Atlas of North American English.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

There’s an amusing semi-controversy in the Boston mayoral race. It’s about City Councilor Annissa Essaibi George allegedly leaning into her Boston accent – or, more specifically, her accent from the Dorchester section of that city. That’s where she grew up, in a section of the city usually associated with Irish-Americans, though she herself is of Polish and Tunisian background. The accent has been described as an attempt to appeal to her predominately white base in her run against City Councilor Michelle Wu, who is originally from the Chicago area and whose base includes many people of color. Meanwhile, Boston’s white base continues to shrink.

So far, anyway, Mrs. George’s Dorchester/South Boston accent, which some find grating and some charming (Saturday Night Live has had fun with it over the years) hasn’t seemed to have helped her much: Ms. Wu remains far ahead in the polls.

But the matter got me thinking about accents. Mass media and demographic mixing have tended to dilute old accents, especially in places like Boston, with so many people having come in from around the world to work and/or attend the region’s multitude of colleges and universities.

In New England, the old accents are weakening. I think of the accents of my late father and his father. My paternal grandfather had a pronounced rural Yankee sound, almost a drawl, that recalled natives of the Maine Coast and even Cape Cod a century or more ago. My father had a milder version of the same thing. His five children retain only traces of it, mingled with my late mother’s Minnesota accent. She also had some (fake?) Southern tones from living in Florida half the year as a girl and then going to high school in Virginia. And my siblings and I have picked up fragments of accents and diction from the places we have lived outside New England.

Of course, even among old Yankee accents, there’s variety in the region. Language experts say much of this can be attributed to where the early colonists came from in England hundreds of years ago – say from the West Country, East Anglia or the Midlands.

Sometimes an accent that some might consider off-putting doesn’t bother others. Consider Franklin Roosevelt’s plummy Hudson River squire voice, which he made no effort to modify for political or other reasons. In part because he could express empathy, confidence and ingenuity to the masses, he became their tribune even as many others from his background were seen as greedy, arrogant and unfeeling about the challenges facing the middle class and the poor in the Great Depression.

But FDR’s accent might be an electoral killer these days.

While historic American accents have long been in decline, the waves of immigrants from non-English-speaking countries over the past few decades have added new and interesting ones to our language stew – and words, too. That English is such an avid absorber of words from other languages means that it has the largest vocabulary of any language – probably its greatest strength and something that’s made it the closest thing to an international language. We’re fortunate to have it as our main tongue.

Frightening farming

“The Giant Ghostly Sheep at Clark’s Farm, October, 12, 1914,’’ photo by Eben Parsons, at the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

LeeAnn Hall: Build back public transit much better

A Green Mountain Transit Authority bus in Montpelier, Vermont’s capital

Via OtherWords.org

If you follow the news about President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda, you might have heard a lot about its 10-year price tag. But you probably haven’t heard much about what it would actually do.

The bill will invest in care for children and seniors, cover more health care under Medicare, make the tax system more fair, and address the climate crisis. Those parts get some coverage, and they’re all worth doing.

But there’s one key thing that’s gotten almost no attention: the bill’s historic investment in public transit. This would have a tremendous positive impact on communities across the country.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has hurt millions of families and their communities in many ways. One essential aspect of community life that faced an existential threat was public transportation. Systems all over the country faced massive revenue shortfalls and budget cuts.

Previous COVID rescue packages helped public transit bypass disaster. But when it comes to transit — the lifeblood of many communities and a key driver of economic growth — just avoiding disaster is not enough.

The pandemic dramatically showed that transit is vital to our communities. Essential workers depend on and operate transit, small businesses depend on transit, and historically marginalized communities depend on transit.

Transit is a key component of a more environmentally sustainable society and the road to equity for disenfranchised communities — in rural, urban, and suburban areas like. In essence, public transit has a huge impact.

Which is why what Democrats in Congress are doing right now is so vital. When you combine the bipartisan infrastructure bill already passed by the U.S. Senate with the Build Back Better plan, it results in the largest ever investment in public transit in the nation’s history.

Investments in public transit create jobs and help connect people to more job opportunities. By one estimate, every $1 billion invested in transit supports and creates more than 50,000 jobs. The larger the investment, the more people benefit.

For years, lawmakers in Washington neglected funding for buses and trains while fueling highways and cars. The result has been a transportation system that is inequitable, unsafe, unhealthy and unsustainable.

It also stunted the economic contributions of too many people, particularly in rural communities and communities of color, at a time when we can’t afford not to give everyone an opportunity to get the jobs they want.

Congress and the Biden administration can reverse this trend.

The Build Back Better plan is so much more than the numbers and political gamesmanship that is covered on TV every night. It’s something that will make people’s lives better — including by rebuilding a transit system that allows more people to move freely within their communities.

Transit is essential. Transit is our future. Congress must pass the Build Back Better plan without delay. Our communities can’t afford to wait any longer.

LeeAnn Hall is the executive director of Alliance for a Just Society and director of the National Campaign for Transit Justice.

We need all the light we can get

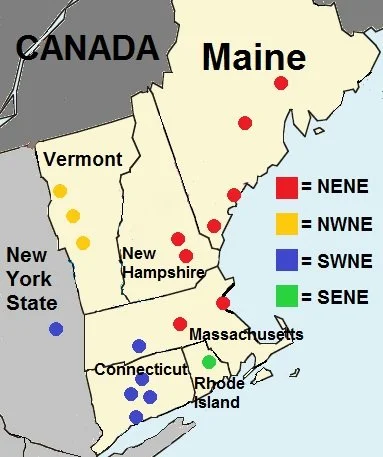

“Untitled Mosaic” (glass, concrete and steel), by Ann Gardner, in her show “Expanding the Perception of Light’’, at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., Nov. 20 through Jan. 8

The gallery says:

“Gardner’s artistic practice stems from a life-long exploration of light, color, pattern, and volume. Using one of the most ancient man-made materials, glass, her sculptures are presented in a range of formats, shapes, and scales. Gardner hand-cuts colored glass into tiny mosaic pieces and reassembles them onto steel armature structures. These come in a variety of forms, such as curved geometric shapes, tubular ovals, waved panels, star bursts or round compositions created in a series. Their volumes protrude into space and recede into themselves, thereby allowing for additional flickering of light, color, and reflection to take place. Some of the sculptures are mounted onto walls while others are free-standing or suspended from the ceiling.’’

One of many significant buildings in New Canaan: This Greek Revival house , built in 1836, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. The house was home to Maxwell E. Perkins (1884-1947), the legendary editor, early promoter and friend of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald Thomas Wolfe and some other famous 20th Century authors.

In 2019 the house was acquired by the New Canaan-based Onera Foundation, with the plan to convert the house into an architectural museum and exhibit space.

Enjoy sonic escapism at nonprofit station on the Cape

WOMR, in Provincetown, Mass., is a unique volunteer-driven and member-supported community radio station that broadcasts a wildly eclectic range of music and talk programming at 92.1 FM, in Provincetown, and also via its sister station, WMFR, at 91.3 FM, in Orleans, and streams live on womr.org. Next spring it will celebrate 40 years of continuous broadcasting, a remarkable achievement for a non-commercial station. The station recently added new programs as the pandemic waned. (Let’s hope the waning continues!)

One show caught our particular attention. It is intriguingly called Chill & Dream. The DJ, who goes by "Braintree Jim," recently told us that the music he plays is a form of sonic escapism and aural nostalgia. "People are searching for a refuge from the storm," he said. His show recalls pop tunes from the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s and mixes those classics with a modern spin, what he calls a fusion of "chill wave" (a nod to so-called yacht rock of the 70s) and "dream pop" (a derivative form of ‘80s pop music). As he says, "it is a safe space from politics, pandemics and put-downs."

His live show on Saturday, Oct. 30, at 9 a.m, will capture that spirit. He plans on something that recalls the ‘70s. "It feels like we are reliving the ‘70s all over again -- talk of stagflation, higher energy costs, comparisons of Afghanistan to Vietnam. What's next? Browns and burnt oranges?" he wonders.

"We got through that period with music so I think recalling the music from 40-50 years ago may help us deal with the present. It will be a fun show, as the ‘70s were a fertile period of creativity. And the music still resonates, which is the main point. Music then had something to say. And it still connects. And we all need an escape. I am not sure I would look good in bell bottoms and platform shoes. But that's OK. We all need to chill and dream."

All shows are streamed live and you can go to womr.org to view the schedule of all the programming.

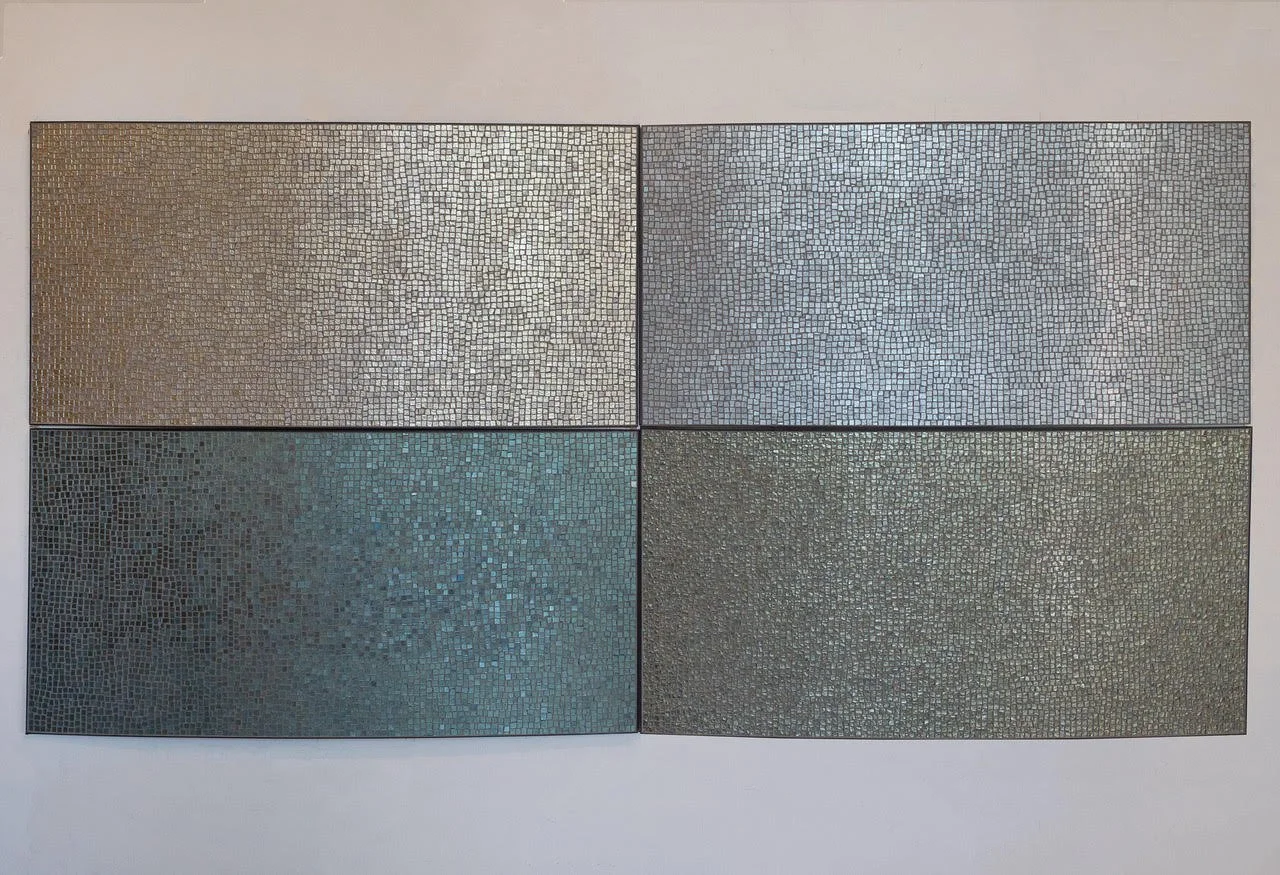

Another take on COVID-19

“MACRO vs micro’’, by Teddy Trocki-Ryba, of Jamestown, R.I., in the show of the same name at AS220, Providence, through Oct. 30.

It’s a fresh take on the experience of COVID-19 in public and in private. As explained in Trocki-Ryba's artist statement, "the work displayed … seeks to juxtapose the MACRO experience of community and government with the micro experience of family and individual life" during the pandemic.

Windmill in Jamestown, R.I., the increasingly affluent and still partly semi-rural town/island in Narragansett Bay

Liz Szabo: Tracking a mysterious COVID-related ailment in children (Copy)

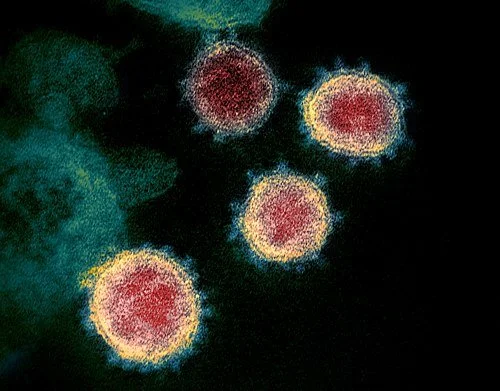

Image of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19:

MIS-C is thought to be caused by an unusual biological response to infection in certain children.

Like most other kids with COVID-19, Dante and Michael DeMaino seemed to have no serious symptoms.

Infected in mid-February, both lost their senses of taste and smell. Dante, 9, had a low-grade fever for a day or so. Michael, 13, had a “tickle in his throat,” said their mother, Michele DeMaino, of Danvers, Mass.

At a follow-up appointment, “the pediatrician checked their hearts, their lungs, and everything sounded perfect,” DeMaino said.

Then, in late March, Dante developed another fever. After examining him, Dante’s doctor said his illness was likely “nothing to worry about” but told DeMaino to take him to the emergency room if his fever climbed above 104.

Two days later, Dante remained feverish, with a headache, and began throwing up. His mother took him to the ER, where his fever spiked to 104.5. In the hospital, Dante’s eyes became puffy, his eyelids turned red, his hands began to swell and a bright red rash spread across his body.

Hospital staffers diagnosed Dante with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, a rare but life-threatening complication of COVID-19 in which a hyperactive immune system attacks a child’s body. Symptoms — fever, stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhea, bloodshot eyes, rash and dizziness — typically appear two to six weeks after what is usually a mild or even asymptomatic infection.

More than 5,200 of the 6.2 million U.S. children diagnosed with COVID have developed MIS-C. About 80% of MIS-C patients are treated in intensive-care units, 20% require mechanical ventilation, and 46 have died.

Throughout the pandemic, MIS-C has followed a predictable pattern, sending waves of children to the hospital about a month after a covid surge. Pediatric intensive care units — which treated thousands of young patients during the late-summer delta surge — are now struggling to save the latest round of extremely sick children.

The South has been hit especially hard. At the Medical University of South Carolina Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital, for example, doctors in September treated 37 children with COVID and nine with MIS-C — the highest monthly totals since the pandemic began.

Doctors have no way to prevent MIS-C, because they still don’t know exactly what causes it, said Dr. Michael Chang, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, in Houston. All doctors can do is urge parents to vaccinate eligible children and surround younger children with vaccinated people.

Given the massive scale of the pandemic, scientists around the world are now searching for answers.

Although most children who develop MIS-C were previously healthy, 80% develop heart complications. Dante’s coronary arteries became dilated, making it harder for his heart to pump blood and deliver nutrients to his organs. If not treated quickly, a child could go into shock. Some patients develop heart rhythm abnormalities or aneurysms, in which artery walls balloon out and threaten to burst.

“It was traumatic,” DeMaino said. “I stayed with him at the hospital the whole time.”

Such stories raise important questions about what causes MIS-C.

“It’s the same virus and the same family, so why does one child get MIS-C and the other doesn’t?” asked Dr. Natasha Halasa of the Vanderbilt Institute for Infection, Immunology and Inflammation.

Doctors have gotten better at diagnosing and treating MIS-C; the mortality rate has fallen from 2.4% to 0.7% since the beginning of the pandemic. Adults also can develop a post-COVID inflammatory syndrome, called MIS-A; it’s even rarer than MIS-C, with a mortality rate seven times as high as that seen in children.

Although MIS-C is new, doctors can treat it with decades-old therapies used for Kawasaki disease, a pediatric syndrome that also causes systemic inflammation. Although scientists have never identified the cause of Kawasaki disease, many suspect it develops after an infection.

Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital and other institutions are looking for clues in children’s genes.

In a July study, the researchers identified rare genetic variants in three of 18 children studied. Significantly, the genes are all involved in “removing the brakes” from the immune system, which could contribute to the hyper-inflammation seen in MIS-C, said Dr. Janet Chou, chief of clinical immunology at Boston Children’s, who led the study.

Chou acknowledges that her study — which found genetic variants in just 17% of patients — doesn’t solve the puzzle. And it raises new questions: If these children are genetically susceptible to immune problems, why didn’t they become seriously ill from earlier childhood infections?

Some researchers say the increased rates of MIS-C among racial and ethnic minorities around the world — in the United States, France and the United Kingdom — must be driven by genetics.

Others note that rates of MIS-C mirror the higher COVID rates in these communities, which have been driven by socio-economic factors such as high-risk working and living conditions.

“I don’t know why some kids get this and some don’t,” said Dr. Dusan Bogunovic, a researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai who has studied antibody responses in MIS-C. “Is it due to genetics or environmental exposure? The truth may lie somewhere in between.”

A Hidden Enemy and a Leaky Gut

Most children with MIS-C test negative for COVID, suggesting that the body has already cleared the novel coronavirus from the nose and upper airways.

That led doctors to assume MIS-C was a “post-infectious” disease, developing after “the virus has completely gone away,” said Dr. Hamid Bassiri, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist and co-director of the immune dysregulation program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Now, however, “there is emerging evidence that perhaps that is not the case,” Bassiri said.

Even if the virus has disappeared from a child’s nose, it could be lurking — and shedding — elsewhere in the body, Chou said. That might explain why symptoms occur so long after a child’s initial infection.

Dr. Lael Yonker noticed that children with MIS-C are far more likely to develop gastrointestinal symptoms — such as stomach pain, diarrhea and vomiting — than the breathing problems often seen in acute covid.

In some children with MIS-C, abdominal pain has been so severe that doctors misdiagnosed them with appendicitis; some actually underwent surgery before their doctors realized the true source of their pain.

Yonker, a pediatric pulmonologist at Boston’s MassGeneral Hospital for Children, recently found evidence that the source of those symptoms could be the coronavirus, which can survive in the gut for weeks after it disappears from the nasal passages, Yonker said.

In a May study in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Yonker and her colleagues showed that more than half of patients with MIS-C had genetic material — called RNA — from the coronavirus in their stool.

The body breaks down viral RNA very quickly, Chou said, so it’s unlikely that genetic material from a covid infection would still be found in a child’s stool one month later. If it is, it’s most likely because the coronavirus has set up shop inside an organ, such as the gut.

While the coronavirus may thrive in our gut, it’s a terrible houseguest.

In some children, the virus irritates the intestinal lining, creating microscopic gaps that allow viral particles to escape into the bloodstream, Yonker said.

Blood tests in children with MIS-C found that they had a high level of the coronavirus spike antigen — an important protein that allows the virus to enter human cells. Scientists have devoted more time to studying the spike antigen than any other part of the virus; it’s the target of covid vaccines, as well as antibodies made naturally during infection.

“We don’t see live virus replicating in the blood,” Yonker said. “But spike proteins are breaking off and leaking into the blood.”

Viral particles in the blood could cause problems far beyond upset stomachs, Yonker said. It’s possible they stimulate the immune system into overdrive.

In her study, Yonker describes treating a critically ill 17-month-old boy who grew sicker despite standard treatments. She received regulatory permission to treat him with an experimental drug, larazotide, designed to heal leaky guts. It worked.

Yonker prescribed larazotide for four other children, including Dante, who also received a drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. He got better.

But most kids with MIS-C get better, even without experimental drugs. Without a comparison group, there’s no way to know if larazotide really works. That’s why Yonker is enrolling 20 children in a small randomized clinical trial of larazotide, which will provide stronger evidence.

A month after Dante DeMaino left the hospital, doctors examined his heart with an echocardiogram to check for lingering heart damage from MIS-C. To his mother’s relief, his heart had returned to normal. Now, more than six months later, Dante is an energetic 10-year-old who has resumed playing hockey and baseball, swimming and rollerblading.

Rogue Soldiers

Dr. Moshe Arditi has also drawn connections between children’s symptoms and what might be causing them.

Although the first doctors to treat MIS-C compared it to Kawasaki disease — which also causes red eyes, rashes and high fevers — Arditi notes that MIS-C more closely resembles toxic shock syndrome, a life-threatening condition caused by particular types of strep or staph bacteria releasing toxins into the blood. Both syndromes cause high fever, gastrointestinal distress, heart muscle dysfunction, plummeting blood pressure and neurological symptoms, such as headache and confusion.

Toxic shock can occur after childbirth or a wound infection, although the best-known cases occurred in the 1970s and ’80s in women who used a type of tampon no longer in use.

Toxins released by these bacteria can trigger a massive overreaction from key immune system fighters called T cells, which coordinate the immune system’s response, said Arditi, director of the pediatric infectious diseases division at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

T cells are tremendously powerful, so the body normally activates them in precise and controlled ways, Bassiri said. One of the most important lessons T cells need to learn is to target specific bad guys and leave civilians alone. In fact, a healthy immune system normally destroys many T cells that can’t distinguish between germs and healthy tissue in order to prevent autoimmune disease.

In a typical response to a foreign substance — known as an antigen — the immune system activates only about 0.01% of all T cells, Arditi said.

Toxins produced by certain viruses and the bacteria that cause toxic shock, however, contain “superantigens,” which bypass the body’s normal safeguards and attach directly to T cells. That allows superantigens to activate 20% to 30% of T cells at once, generating a dangerous swarm of white blood cells and inflammatory proteins called cytokines, Arditi said.

This massive inflammatory response causes damage throughout the body, from the heart to the blood vessels to the kidneys.

Although multiple studies have found that children with MIS-C have fewer total T cells than normal, Arditi’s team has found an explosive increase in a subtype of T cells capable of interacting with a superantigen.

Several independent research groups — including researchers at Yale School of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health and France’s University of Lyon — have confirmed Arditi’s findings, suggesting that something, most likely a superantigen, caused a huge increase in this T cell subtype.

Although Arditi has proposed that parts of the coronavirus spike protein could act like a superantigen, other scientists say the superantigen could come from other microbes, such as bacteria.

“People are now urgently looking for the source of the superantigen,” said Dr. Carrie Lucas, an assistant professor of immunobiology at Yale, whose team has identified changes in immune cells and proteins in the blood of children with MIS-C.

Uncertain Futures

One month after Dante left the hospital, doctors examined his heart with an echocardiogram to see if he had lingering damage.

To his mother’s relief, his heart had returned to normal.

Today, Dante is an energetic 10-year-old who has resumed playing hockey and baseball, swimming and rollerblading.

“He’s back to all these activities,” said DeMaino, noting that Dante’s doctors rechecked his heart six months after his illness and will check again after a year.

Like Dante, most other kids who survive MIS-C appear to recover fully, according to a March study in JAMA.

Such rapid recoveries suggest that MIS-C-related cardiovascular problems result from “severe inflammation and acute stress” rather than underlying heart disease, according to the authors of the study, called Overcoming COVID-19.

Although children who survive Kawasaki disease have a higher risk of long-term heart problems, doctors don’t know how MIS-C survivors will fare.

The NIH and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have launched several long-term trials to study young covid patients and survivors. Researchers will study children’s immune systems to uncover clues to the cause of MIS-C, check their hearts for signs of long-term damage and monitor their health over time.

DeMaino said she remains far more worried about Dante’s health than he is.

“He doesn’t have a care in the world,” she said. “I was worried about the latest cardiology appointment, but he said, ‘Mom, I don’t have any problems breathing. I feel totally fine.’”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

A refugee’s tale from Gambia brutality to Rhode Island

After its pandemic hiatus, The Providence Committee on Foreign Relations is embarking on its exciting dinner speaker series for 2021-2022 at the Hope Club, in Providence.

The first speaker, coming Tuesday, Oct. 26, is Omar Bah, who fled The Gambia after having been declared a wanted man because of articles he wrote criticizing the country’s dictator. Inspired by his experience, Mr. Bah founded the Refugee Dream Center in Providence to offer other refugees in Rhode Island post-resettlement support.

Preview his amazing story in a PBS profile via this link:

https://watch.ripbs.org/video/omar-bah-05lqhe/

The PCFR, chaired by health-care professional and state Representative Barbara Ann Fenton-Fung, says: “We're happy to have Omar join us on Tuesday night at the Hope Club, starting at 6 p.m. Due to COVID-related issues, tickets must be purchased by Sunday night. As a reminder, the PCFR has collectively agreed to require proof of vaccination to attend our events this fall, which will be requested at the door. Thank you for your cooperation in advance.

For tickets, please use this link

Don Pesci: In a place of unchecked, secretive power

Entrance to the MacDougall Walker Correctional Institution, in Suffield, Conn., where Brent McCall spent time.

Sham: Inside the Criminal Correction Racket, by Brent McCall ($12.95). {He was convicted of violent crimes.}

VERNON, Conn.

People who have never been inside a prison – most of us -- think: 1) the purpose of a prison is to provide punishment, not rehabilitation; 2) justice essentially means, “If you did the crime, you do the time; 3) every prisoner has duped himself or herself into thinking he or she is innocent and therefore any punishment, however unjust, is merited; 4) egotism does not stop at prison doors, and the notion that one should take a prisoner’s testimony as gospel truth over that of prison authorities is patently absurd; and 5) books written by prisoners nursing grievances should be taken with two tons of salt.

People convinced that the above propositions are indisputably true will not be persuaded otherwise by Brent McCall’s latest book, Sham, which presents a strong case that the administrative architecture of modern prisons, many of which put themselves forward as rehabilitation centers, have yet to throw off certain medieval characteristics. Sociologists who spend their days probing various administrative organizations – schools, the family, corporations, political parties, etc. -- should turn the pages of Sham with some interest, because prisons are among the first age-old repositories of unchecked, secretive and personalized administrative power.

When the cell door is locked and the key thrown away, also discarded is any critical word from prisoners concerning administrative justice or humane treatment. At its most primitive, punishment without mercy is terror. Central to terror is arbitrary, personalized treatment by an overpowering force. That is the message of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s partly autobiographical novel The Idiot.

Written twenty years after Dostoevsky’s own imprisonment, Prince Myshkin, the protagonist of the novel, tells a story of an execution that intentionally resembles Dostoyevsky’s own mock execution: “...But better if I tell you of another man I met last year...this man was led out along with others on to a scaffold and had his sentence of death by shooting read out to him, for political offenses. About twenty minutes later a reprieve was read out and a milder punishment substituted...he was dying at 27, healthy and strong...he says that nothing was more terrible at that moment than the nagging thought: "What if I didn't have to die!...I would turn every minute into an age, nothing would be wasted, every minute would be accounted for... (Part I, chapter 5).”

In The House of the Dead, Dostoevsky traces the path of a “diseased tyranny,” always related to the unbridled personal power of one man over another: “The human being, the member of society, is drowned forever in the tyrant, and it is practically impossible for him to regain human dignity, repentance, and regeneration...the power given to one man to inflict corporal punishment upon another is a social sore...it will inevitably lead to the disintegration of society.”

The subject of McCall’s Sham is not personal vindication. Sham is a brief against personal tyranny, the tyranny of an administrative organ hidden from public view and, deployed outside of administrative guidelines, inescapable. Sunshine, we are often told, is the best disinfectant. What is brought to light no longer festers in the dark. Prisons are meant to be, by design, dark. And prisoners are meant to be invisible. Any prisoner who flips on the light switch is bound to be greeted with sour disfavor.

Sham is McCall’s second book. I also reviewed his first, Down the Rabbit Hole: How the Culture of Corrections Encourages Crime, co-written with Michael Liebowitz, McCall’s friend and cellmate at (MacDougall-Walker CI in Suffield, Conn.) in February, 2018.

Following the publication of their first co-written book, the two co-authors were separated, McCall being shuttled off to Cheshire Correctional Institution. Both authors had been heard semi-regularly on Todd Feinberg’s radio talk show program at WTIC News/Talk 1080.

At the center of McCall’s disfavor was an embarrassing sham he had uncovered that involved salary padding on the part of prison officials. Both McCall and Liebowitz had agreed that none of their publications should be made available to other prisoners, a stipulation that since has been faithfully adhered to by all parties. The publications were intended to be corrective, not unnecessarily destructive to prison order or discipline. Both authors favor discipline when it is merited, just punishment and administrative order.

Indeed, the chief point of both books is that chaos on occasion replaces both discipline and order in some prisons because in some instances non-professional administrative staff and administrators find chaos, for a number of reasons, to be preferable to order and discipline.

Sham is jam-packed with such incidents. Such “troublesome themes,” McCall writes, play out time and again in many prisons, even when gross “dereliction of duty” presents clear and present dangers to both prisoners and guards.

An episode involving a guard and two quarreling prisoners in which the guard was clearly baiting the prisoners rather than repressing the quarrel, a clear dereliction of duty, induced McCall to write a letter to the Commissioner of prisons. Naturally, as on so many other occasions, McCall was not advised that the guard had been disciplined. Prisoners who had witnessed the quarrel drew the right conclusions from it, namely that order and disciple in the prison was not a high priority for administrators.

McCall writes that the same theme, always destructive of rehabilitation, “took place at MacDougall’s prison industries… First, there was obviously nothing of rehabilitative value in staff colluding with inmates to bilk Connecticut taxpayers out of fraudulent overtime hours (not to mention the various other kinds of thefts going on there).

“Secondly, I went from being ignored to being transferred, with the staff creating the climate that ostensibly made that transfer necessary… Finally, even after all this time, I have no idea whether any of the staff at MacDougall industries were ever held responsible for the crime they had committed or the CDOC [Connecticut Department of Corrections] directives they openly violated.”

True discipline should not be confused with a “foolish consistency,” the “the hobgoblin of little minds,” according to Ralph Waldo Emerson. In prison environments, the two often walk hand in hand.

Chapter 5 of Sham, headed “Correctional Lemmings”, carries a quote from George Orwell: “The heresy of heresies was common sense,” and it describes in meticulous deatail the orderly procession of chow lines at Cheshire CI. “On the whole,” McCall writes, “East Block’s chow procedure is one of the most orderly and well managed things I’ve ever seen the Connecticut Department of Corrections do.”

It is a choreographed dance, flawless in every step.

Then comes chow. The prisoners are seated, and chaos – disruptive conversations that run afoul of CDOC’s Code of Penal Discipline – follow in due course, while unperturbed guards pretend not to notice the disorder.

“Why regulate seemingly innocuous behavior, McCall ruminates, while ignoring misconduct that would likely get one arrested for breach of peace and disorderly conduct at the local Burger King?”

Why must arbitrariness rule like a king in prisons? Is not the arbitrary the enemy of discipline, precisely in the same way a foolish consistency is the enemy of constructive order?

McCall makes the attempt – most often successfully – to answer questions such as these.

Full of footnotes but lacking a proper index for quick reference, Sham is an easy read, because McCall writes well, and his analytic powers are fully mature. The purpose of analytical writing is to dispel the darkness and shed light.

After he had finished reading Witness, Whittaker Chambers’s account of his own rise from demon communism to the light, Andre Malraux told the former soviet operative, “You did not come back from hell with empty hands.”

Sham is brave, clear in its witness, and well worth a read.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Group trip

Flocks of birds assembling before migration southwards (probably Common Starling)

“As if a cast of grain leapt back to the hand,

A landscapeful of small black birds, intent

On the far south, convene at some command….’’

— From “An Event,’’ by Richard Wilbur (1921-2017), New England-based, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet

Tree fundamentals

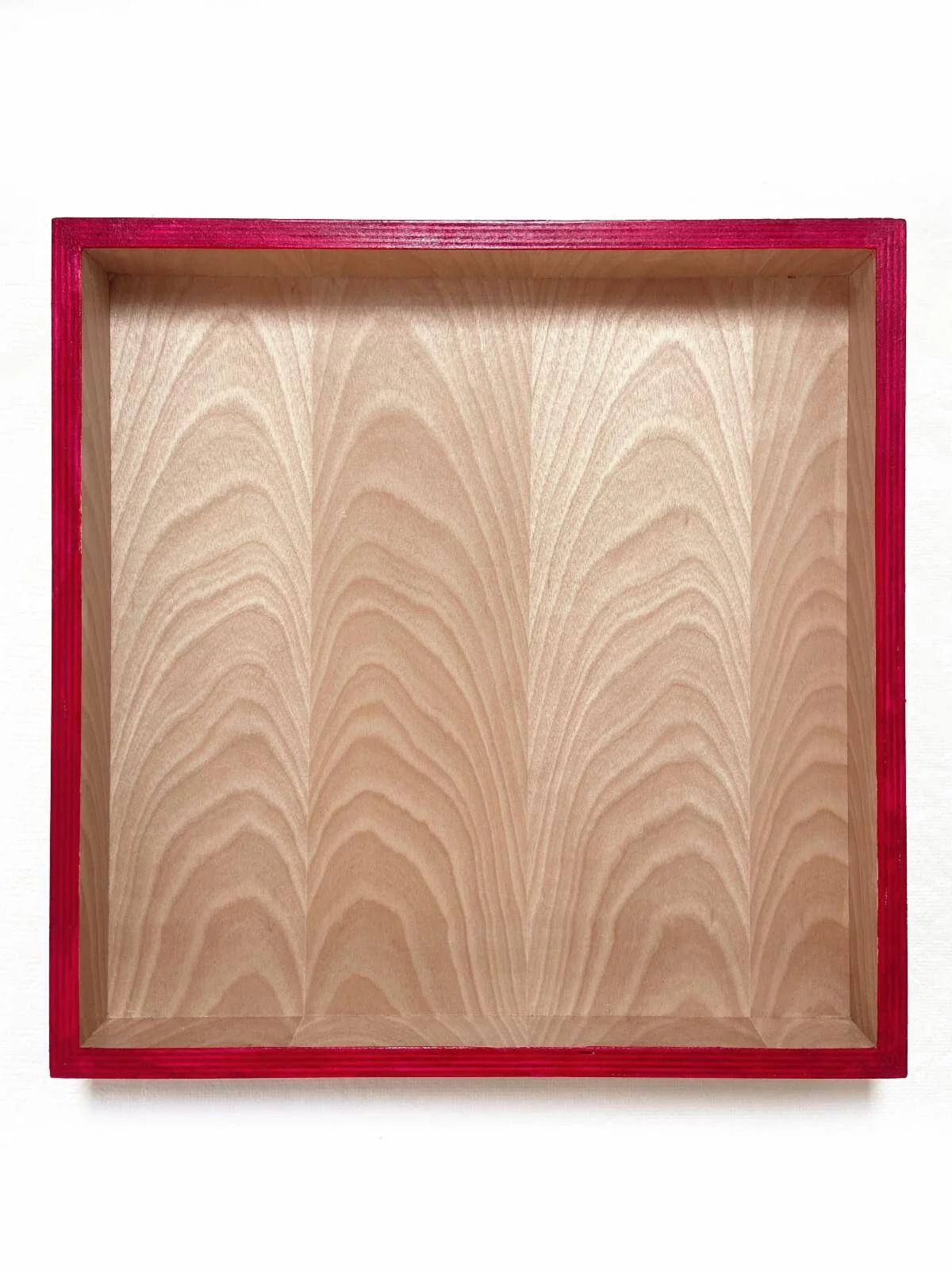

“Cathedral of the Forest (acrylic on wood), by Rose Olson, in her show “Rose Olson: New Works,’’ through Oct. 31 at Kingston Gallery, Boston. She has studios in Boston’s South End and in Beverly, on Massachusetts’s North Shore.

Braddock Park, in the South End

— Photo by Payton Chung

Veterans Memorial Bridge, looking toward Beverly from Salem

David Warsh: Pinning things down using history

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In Natural Experiments of History, a collection of essays published a decade ago, editors Jared Diamond and James Robinson wrote, “The controlled and replicated laboratory experiment, in which the experimenter directly manipulates variables, is often considered the hallmark of the scientific method” – virtually the only approach employed in physics, chemistry, molecular biology.

Yet in fields considered scientific that are concerned with the past – evolutionary biology, paleontology, historical geology, epidemiology, astrophysics – manipulative experiments are not possible. Other paths to knowledge are therefore required, they explained, methods of “observing, describing, and explaining the real world, and of setting the individual explanations within a larger framework “– of “doing science,” in other words.

Studying “natural experiments” is one useful alternative, they continued – finding systems that are similar in many ways but which differ significantly with respect to factors whose influence can be compared quantitatively, aided by statistical analysis.

Thus this year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences recognizes Joshua Angrist, 61, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; David Card, 64, of the University of California, Berkeley; and Guido Imbens, 58, of Stanford University, “for having shown that natural experiments can answer central questions for society.”

Angrist, burst on the scene in in 1990, when “Lifetime Earnings and the Vietnam Era Draft Lottery: Evidence from Social Security administrative records” appeared in the American Economic Review. The luck of the draw had, for a time, determined who would be drafted during America’s Vietnam War, but in the early 1980s, long after their wartime service was ended, the earnings of white veterans were about 15 percent less than the earnings of comparable nonveterans, Angrist showed.

About the same time, Card had a similar idea, studying the impact on the Miami labor market of the massive Mariel boatlift out of Cuba, but his paper appeared in the less prestigious Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Card then partnered with his colleague, Alan Krueger, to search for more natural experiments in labor markets. Their most important contribution, a careful study of differential responses in nearby eastern Pennsylvania to a minimum-wage increase in New Jersey, appeared as was Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage (Princeton, 1994). Angrist and Imbens, meanwhile, mainly explored methodological questions.

Given the rule that no more than three persons can share a given Nobel prize, and the lesser likelihood that separate prizes might be given in two different years, Krueger’s tragic suicide, in 2019, rendered it possible to cite, in a single award, Card, for empirical work, and Angrist and Imbens, for methodological contributions.

Princeton economist Orley Ashenfelter, who, with his mentor Richard Quandt, also of Princeton, more or less started it all, told National Public Radio’s Planet Money that “It’s a nice thing because the Nobel committee has been fixated on economic theory for so long, and now this is the second prize awarded for how economic analysis is now primarily done. Most economic analysis nowadays is applied and empirical.” [Work on randomized clinical trials was recognized in 2019.]

In 2010 Angrist and Jörn-Staffen Pischke described the movement as “the credibility revolution.” And in the The Age of the Applied Economist: the Transformation of Economics since the 1970s. (Duke, 2017), Matthew Panhans and John Singleton wrote that “[T]he missionary’s Bible today is less Mas-Colell et al and more Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion (Angrist and Pischke, Princeton, 2011)

Maybe so. Still, many of those “larger frameworks” must lie somewhere ahead.

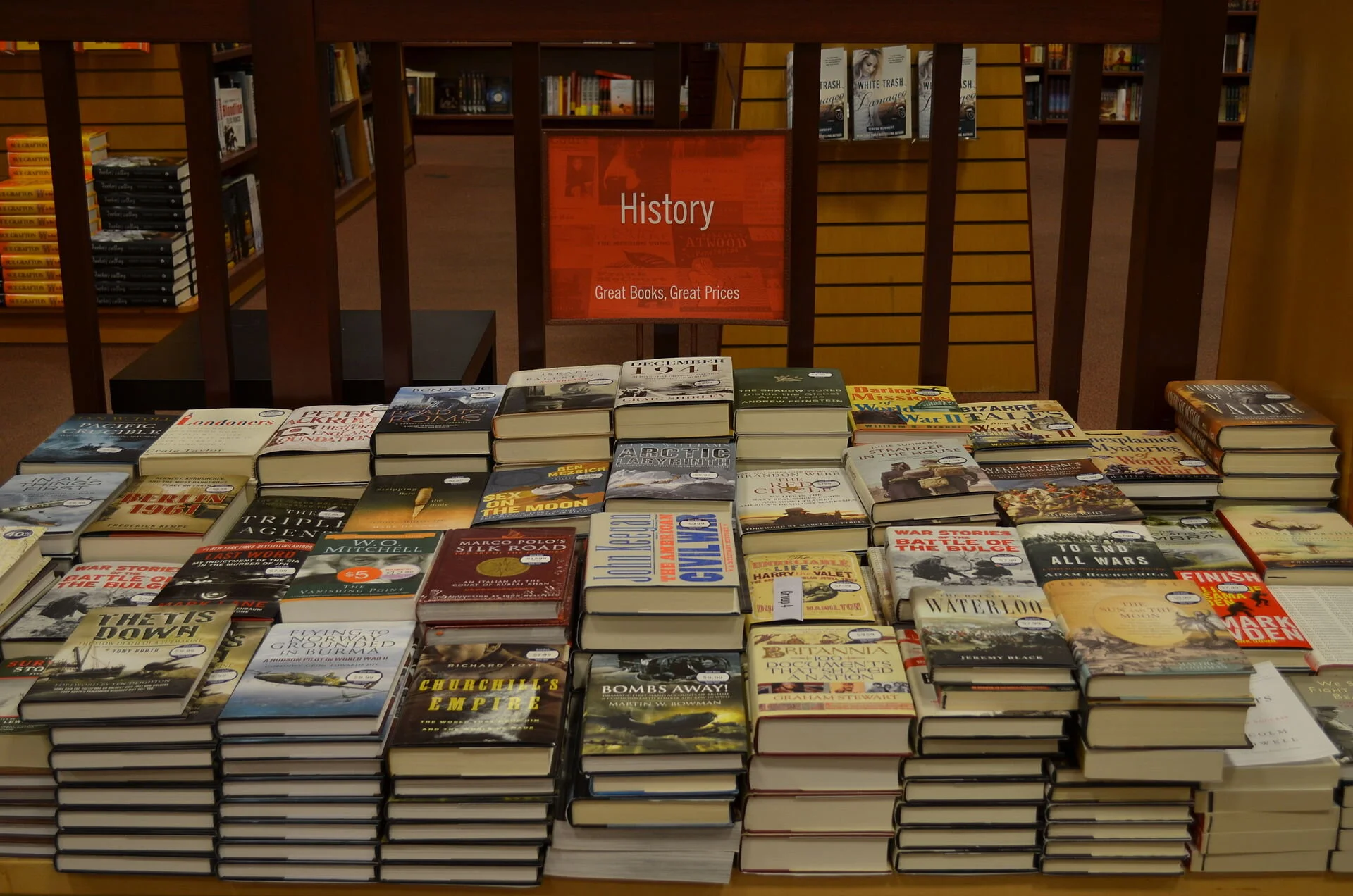

“History,’’ by Frederick Dielman (1896)

That Dale Jorgenson, of Harvard University, would be recognized with a Nobel Prize was an all but foregone conclusion as recently as twenty years ago. Harvard University had hired him away from the University of California at Berkeley in 1969, along Zvi Griliches, from the University of Chicago, and Kenneth Arrow, from Stanford University (the year before). Arrow had received the Clark Medal in 1957, Griliches in 1965; Jorgenson was named in 1971. “[H]e is preeminently a master of the territory between economics and statistics, where both have to be applied in the study of concrete problems.” said the citation. With John Hicks, Arrow received the Nobel Prize the next year.

For the next thirty years, all three men brought imagination to bear on one problem after another. Griliches was named a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association in 1994; he died in 1999. Jorgenson, named a Distinguished Fellow in 2001, began an ambitious new project in 2010 to continuously update measures of output and inputs of capital, labor, energy, materials and services for individual industries. Arrow returned to Stanford in 1979 and died in 2017.

Call Jorgenson’s contributions to growth accounting “normal science” if you like – mopping up, making sure, improving the measures introduced by Simon Kuznets, Ricard Stone, and Angus Deaton. It didn’t seem so at the time. The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on.

xxx

Where are the women in economics, asked Tim Harford, economics columnist of the Financial Times the other day. They are everywhere, still small in numbers, especially at senior level, but their participation is steadily growing. AEA presidents include Alice Rivlin (1986); Anne Krueger (1996); Claudia Goldin (2013); Janet Yellen (2020); Christina Romer (2022), and Susan Athey, president elect (2023). Clark medals have been awarded to Athey (2007), Esther Duflo (2010), Amy Finkelstein (2012), Emi Nakamura (2019), and Melissa Dell (2020).

Not to mention that Yellen, having chaired the Federal Reserve Board for four years, today is secretary of the Treasury; that Fed governor Lael Brainerd is widely considered an eventual chair; that Cecilia Elena Rouse chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers; that Christine Lagarde is president of European Central Bank; and that Kristalina Georgieva is managing director of the International Monetary Fund, for a while longer, at least.

The latest woman to enter these upper ranks is Eva Mörk, a professor of economics at Uppsala University, apparently the first female to join the Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences that recommends the Economics Sciences Prize, the last barrier to fall in an otherwise egalitarian institution. She stepped out from behind the table in Stockholm last week to deliver a strong TED-style talk (at minutes 5:30-18:30 in the recording) about the whys and wherefores of the award, and gave an interesting interview afterwards.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

‘Facing a sheer sky’

“Medusa,’’ by Arnold Böcklin, circa 1878

“I had come to the house, in a cave of trees,

Facing a sheer sky.

Everything moved, — a bell hung ready to strike,

Sun and reflection moved wheeled by.’’

— From “Medusa,’’ by Louise Bogan (1897-1970), a native of Livermore Falls, Maine, who became, in 1945, the first woman U.S. poet laureate. She also wrote fiction and criticism, and was the regular poetry reviewer for The New Yorker.

The Jonathan Fairbanks House, in Dedham, Mass., built circa 1641, is the oldest surviving timber-frame house in North America.

Chris Powell: Stupid Facebook post by GOP legislator distracts from Connecticut’s real problems

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut was pretty normal this week. The cities again were full of shootings and other mayhem. Group home workers went on strike because, while they take care of people who are essentially wards of the state, their own compensation omits medical insurance.

Hundreds of health-care workers were suspended for refusing to get a COVID-19 vaccination. Tens of thousands of children went to school without learning much, since at home they have little in the way of parenting and thus no incentive to learn.

The two longstanding scandals in the state police -- the drunken retirement party at a brewery in Oxford and the fatal shooting of an unarmed and unresisting mentally ill 19-year-old in West Haven -- remained unresolved, the authorities apparently expecting them to be forgotten. They're probably right.

And Gov. Ned Lamont called for sticking with football at the University of Connecticut despite its worsening record and expense.

Nevertheless, the great political controversy of the week was something else -- a Facebook post by state Rep. Anne Dauphinais (R.-Killingly). It likened the governor to Adolf Hitler on account of the emergency powers that Lamont repeatedly has claimed and his party's majorities in the General Assembly have granted him in regard to the virus epidemic even though there no longer is any emergency -- at least none involving the epidemic.

Rather than apologize for her intemperance and hyperbole, Dauphinais "clarified" that she meant to liken the governor to the Hitler of the early years of his rule in Germany, not the Hitler of the era of world war and concentration camps. This wasn't much clarification, since the Nazi regime established concentration camps just weeks after gaining power in 1933 and unleashed wholesale murder on its adversaries just a year later, on June 30, 1934 -- the "Night of the Long Knives" -- more than five years before invading Poland.

But so what if a lowly state legislator from the minority party got hysterical on Facebook?

Her name calling did no actual harm to anyone. The governor's skin is far thicker than that. Indeed, to gain sympathy any politician might welcome becoming the target of such intemperance and thus gaining sympathy.

Besides, Dauphinais's hysteria wouldn't even have been noticed if other politicians didn't make such a show of deploring it over several days. The top two Democratic and top two Republican leaders of the General Assembly went so far as to issue a joint statement condemning the use of political analogies to Nazism. In separate statements they criticized Dauphinais by name.

They all seemed to feel pretty righteous about it.

But meanwhile they had little to say about the state's problems that really matter, problems affecting the state's quality of life, problems on display throughout the week. Maybe they should thank Dauphinais for the distraction she provided them.

xxx

Will his support for University of Connecticut football be Governor Lamont's Afghanistan? Is the state just throwing good money after bad?

Now that Hartford wants to tear up Brainard Airport for commercial development, could Pratt & Whitney Stadium in East Hartford be leveled and Rentschler Field rebuilt as the airport it once was, replacing Brainard?

And will anyone ever take responsibility for anything at UConn?

Probably not. For even if UConn football is a disaster forever, it will cost far less than the disasters of Connecticut's education and welfare policies.

Why get upset at UConn football when the more Connecticut spends in the name of education, the less education is produced and the poorer students do, or when the more that is spent on welfare and social programs, the less people become self-sufficient and the more they become dependent on government?

The problem with UConn football is that results are still the object of the program and the public easily can see them -- the weekly scores during football season and the losing record.

By contrast, the education scores -- the results of standardized tests -- are publicized only occasionally and not on the sports pages, while the results of welfare and social programs are never audited and reported at all. With education and welfare, results are no longer the objective. They have become an end in themselves.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Pratt & Whitney (the aerospace company) Stadium at Rentschler Field, in East Hartford. It is primarily used for football and soccer, and is the home field of the University of Connecticut Huskies.