‘Bring your camera’

Granny Smith apples are unusual in being green when ripe.

— Photo by Assianir

“Cider served in pounded copper mugs.

Covered bridge rides.

Pumpkin pies.

Tourists in Vermont. What do they want?

Where to find Granny Smith?

She waits for you in my tree. Bring your camera, you'll see.’’

—From “Smell the Season Sunshine,’’ by Marikate Kingston, a poet who lives in Westport, Conn.

'Tosses up our losses'

Cape Ann

“It tosses up our losses, the torn seine,

The shattered lobster pot, the broken oar

And the gear of foreign dead men. The sea has many voices.’’

Many gods and many voices.’’

From “The Dry Salvages,’’ by T.S. Eliot (1888-1965), the famed Anglo-American poet from a Boston Brahmin family, who had a summer place on Cape Ann, off which the rocks called “The Dry Salvages’’ menaced boats.

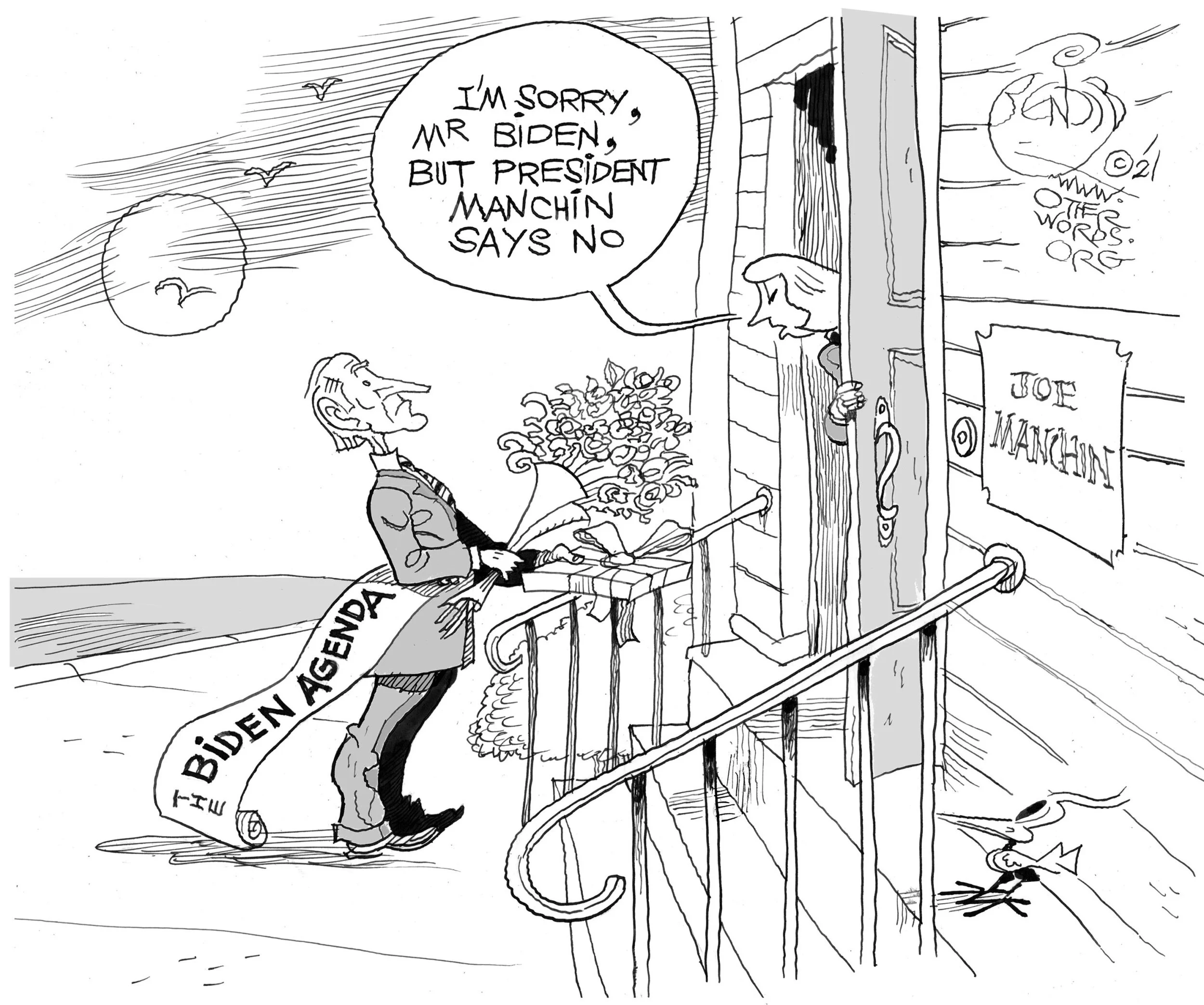

Chris Powell: Fight bulimia with censorship?

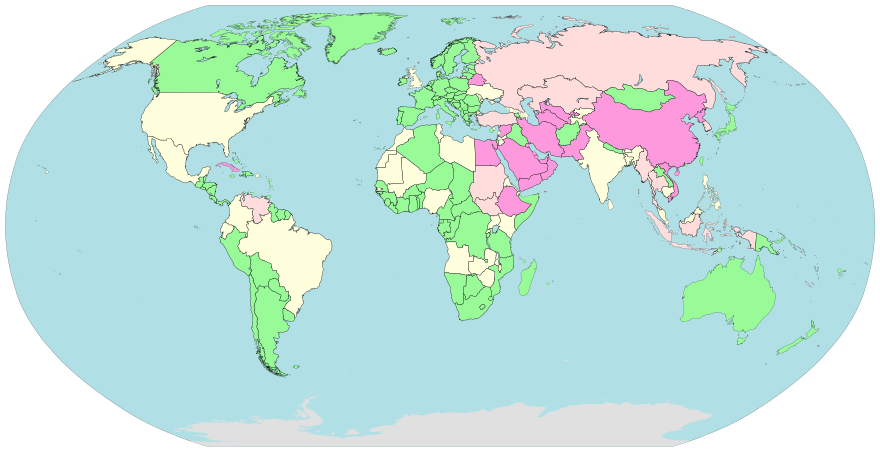

Internet censorship by country: Dark pink has pervasive censorship; light pink substantial; yellow selective, and green little or none.

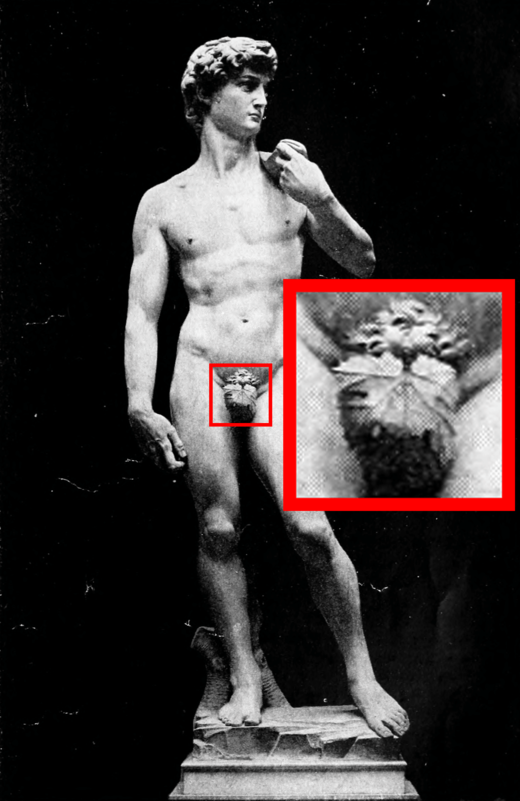

The plaster cast of Michelangelo’s ‘‘David ‘‘ at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London, has a detachable plaster fig leaf displayed nearby. Legend claims that the fig leaf was created in response to Queen Victoria's shock upon first viewing the statue's nudity, and was hung on the figure before royal visits, using two strategically placed hooks.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Nearly everyone on Planet Earth with Internet access seems to use the social-media platform Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram even as last week's U.S. Senate subcommittee hearing over which Connecticut's Richard Blumenthal presided suggested that Facebook is an evil scheme to push young teenage girls into bulimia and other psychological disorders.

Facebook and Instagram certainly have brought out the latent narcissism of hundreds of millions of people, allowing them to spend half their day inflicting on others every trivial detail of their lives. But of course no one is compelled to participate in social media, and young teenage girls can participate only if their parents provide them with cell phones, computers and Internet access and pay little attention to what the kids do with those things.

This seemed lost on last week's hearing, as Senator Blumenthal read aloud a text message he said he had received from an unidentified father:

“My 15-year-old daughter loved her body at 14, was on Instagram constantly and maybe posting too much. Suddenly she started hating her body -- her body dysmorphia, now anorexia -- and was in deep, deep trouble before we found treatment. I fear she will never be the same.”

So who is responsible? The hearing accused Facebook co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

And what is the remedy? The hearing seemed to be demanding censorship by the government.

"Facebook and Big Tech are facing a ‘Big Tobacco' moment," Blumenthal said, referring to the tobacco industry's long struggle against regulation of its product and its concealment of research showing that -- as everyone with half a brain had known for hundreds of years -- using tobacco is unhealthy.

Former Facebook employee Frances Haugen testified that the company knows that teenage girls are especially vulnerable to what may be said about them on social media -- as if anyone needed confidential company documents to confirm the neurotic tendencies of teenage girls.

But Facebook's product and the major product of technology companies is not tobacco. It is speech and self-expression, freedom of which is constitutionally guaranteed even when it is narcissistic, stupid, mistaken and capable of being construed destructively. All other vehicles for conveying expression and information are just as capable of facilitating the harm being attributed to Facebook and Instagram.

Haugen suggested that Congress repeal the law exempting Internet companies from being sued for content posted by their users. That well might be the end of social media, since there is no way to police large volumes of social-media postings except by using computer programs to target keywords, a mechanism that censors the innocent and the guilty alike.

And what about the individual privacy of communicating by Internet? Should the government be empowered to compel Facebook and other social-media companies to become general censors? If government can do that to social-media companies, it can do that to newspapers, magazines, broadcasters, e-mail service providers and even telephone companies.

While the teen years always will be full of psychological stress, most young people in the land of the free have recovered more or less and grown up to be glad of their freedom.

Yet last month the FBI reported a 30 percent annual increase in murders in this country, from which no one will be recovering. The country is coming apart, and it's not because of Facebook and bulimia.

xxx

Farmington's police union president, Sgt. Steve Egan, blames Connecticut's new police accountability law for the severe injury inflicted on Officer James O'Donnell last month when a man driving a stolen car sped off, crushing the officer against his cruiser.

No evidence has been provided for the union president's claim. But a failure of law can be seen here. For the man charged in the incident is reported to have a long criminal record. That is, a state with an incorrigibility law already might have put him away for life, or at least for enough years to eliminate his capacity for crime.

Connecticut is not such a state. Instead of enacting an incorrigibility law the state keeps closing prisons and letting incorrigibles hurt people.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Autumn browning

“Split Second” (oil on gallery-wrap canvas), by Tanya Hayes Lee, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

Beats whale-oil lamps

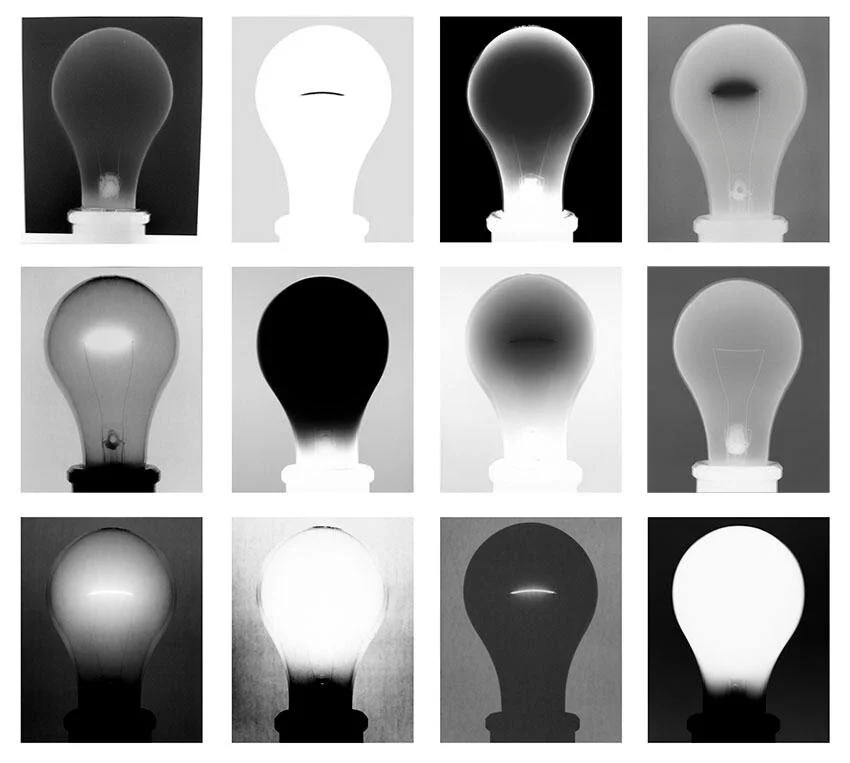

“One Bulb (Version II)” (12 Gelatin Silver Prints on Ilford Matte), by Amanda Means, at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth’s art gallery in New Bedford, Oct., 14-Oct. 23.

New Bedford waterfront in 1867. For part of the 19th Century, New Bedford was the world’s whaling capital.

Todd McLeish: Artificial light threatens animal populations

Light pollution is mostly unpolarized, and its addition to moonlight results in a decreased polarization signal.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Global insect populations have declined by as much as 75 percent during the past 50 years, according to scientists, potentially leading to catastrophic impacts on wildlife, the environment and human health. Most studies point to habitat loss, climate change, industrial farming and pesticide use as the main factors driving the loss of insects, but a new study in the United Kingdom points to another cause: light pollution.

The ever-increasing glow of artificial light from street lights, especially LED lights, was found to have detrimental effects on the behavior of moths, resulting in a reduction in caterpillar numbers by half. And since birds and other wildlife rely on caterpillars as an important food source, the consequences of this decline could be devastating.

According to Douglas Boyes of the British Center for Ecology & Hydrology, street lights cause nocturnal moths to postpone laying their eggs while also making the insects more visible to predators such as bats. In addition, caterpillars that hatch near artificial light exhibit abnormal feeding behavior.

But moths are not the only wildlife affected by artificial light.

Since most songbirds migrate at night, birds that have evolved to use the moon and stars as navigational tools during migration often become disoriented when flying over a landscape illuminated with artificial light.

“City centers that are very bright at night can act as attractants to migrating birds,” said ornithologist Charles Clarkson, director of avian research at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island. “They get pulled toward cities, and when they find themselves amid heavily lit buildings, they become disoriented, leading to a large number of window strikes and increased mortality.”

It is unclear why birds are attracted to lights, but studies have found increasing densities of migrating birds the closer one gets to cities.

“Birds probably see these cities on the horizon from a long distance, and they get pulled toward these locations en masse,” Clarkson said.

Street lights have also been found to be problematic to birds. Birds are active later into the evening when they are exposed to nearby artificial lighting at night, and they often sing later as well.

“Sometimes that might lead to more food availability, since lights attract insects,” Clarkson said. “But it also affects the physiology of the birds when they’re active when they should be sleeping. Some birds that live in heavily lit urban or suburban areas begin nesting earlier, too, up to a month earlier than they typically would. And that leads to a phenological mismatch between when food is traditionally available and when the chicks are hatching and need to be fed.”

Artificial lighting may cause other species to face a similar mismatch. Christopher Thawley, a lecturer and researcher in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Rhode Island, studied lizards in Florida and found not only that the reptiles advanced the onset of breeding when exposed to artificial light, but they also laid more eggs and even grew larger under artificial lighting conditions. Other kinds of wildlife could have comparable results.

“Light at night can sometimes mimic a longer day length, and a lot of animals use length of day as a cue for when to start breeding,” he said. “If they’re exposed to light at night, they think the days are longer so it must be time to breed. Length of daylight is also a good cue for when to migrate or when to start calling, and that could potentially be an issue for some species.”

Thawley said frogs that call at night near artificial light could be more vulnerable to predators.

“When nights are darker, frogs call more, and when the moon is bright they call less,” he said. “It’s more dangerous to call during a full moon because predators could see you. That would be especially true under artificial lighting conditions, too.”

Scientists are still trying to understand the intricacies of how light pollution impacts wildlife, and yet some cities are already taking action to reduce its impact. Dozens of cities around the United States and Canada, including Boston, New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C., have launched “lights out” programs aimed at dimming city lights during the peak of bird migration.

Providence is not among the cities participating in a “lights out” program, but local advocates have discussed how to get it started for several years. They say it would be a positive first step toward reducing the impact of artificial lighting on local and migrating wildlife.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog and frequently writes for ecoRI News.

If you see this above, take cover

“River in the Sky,’’ by Mo Kelman, in the group show “Luminous,” at Dedee Shattuck Gallery, Westport, Mass., Oct. 16-Nov. 14

Fall on the Westport River

Llewellyn King: Shutting off natural gas can dangerously destabilize the electricty grid

Fields Point liquified natural gas facility, in Providence

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It has been an annus horribilis for the nation’s electric utility companies. Deadly storms and wildfires have left hundreds of thousands -- and for short periods millions -- of electricity customers without power, sometimes for days and weeks.

These destructive weather events have come at a time when utilities are being squeezed from all directions: by customer needs, by activists’ demands, by state regulators, and by the zero-carbon urgency of the Biden administration as expressed in its bill, the Build Back Better Act, to upgrade and overhaul the nation’s infrastructure.

The utilities themselves have set ambitious carbon-emission-reduction goals, but in some cases, they still can’t meet the demands of the government. They are caught between the clear need to harden their infrastructure against severe weather and shuttering their reliable but polluting coal plants and mothballing their dependable gas turbines.

This predicament caused Jim Matheson, president of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, which represents hundreds of utilities, mostly small, in rural areas, to ask Congress to make exceptions, or at least to understand that things can’t be changed overnight. In a letter to House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Palone (D.-N.J.) and ranking minority member Cathy McMorris Rogers (Wash.), Matheson said there was concern with the Clean Electricity Performance Program (CEPP) part of the bill.

“The CEPP’s very narrow, 10-year program implementation window is unrealistic. The electric co-ops have existing contractual obligations and resource development plans that extend for several years, if not decades. Many of those plans continued deployment of a diverse set of affordable, clean electricity sources, but not all those plans align with the CEPP. …. The narrow implementation window also limits our ability to take advantage of technologies like energy storage, carbon capture, or advanced nuclear, which are unlikely to be deployable in the near term,” Matheson said.

The predicament of utilities is that there is no reliable storage and that the two principal sources of renewable power, wind and solar, are subject to the vagaries of weather. During Winter Storm Uri, which hit Texas last February, solar, along with all other sources of energy, froze under sheets of snow and ice. The result was disaster and heavy loss of life.

In that instance, gas didn’t save the day: Lines and instruments froze, and what gas was available was sold at astronomical prices.

The lesson was clear: Prepare for the worst. That lesson was repeated in a series of hurricanes, including this year’s devastating Ida, which plunged parts of Louisiana into the dark for more than a week.

If the lesson hasn’t been grasped in the United States, it is being repeated in Europe right now: A unique wind drought that lasted six weeks has left the European grid reeling and has thrown Britain into a full energy crisis.

The issue is not that alternative energy -- wind and solar for now -- isn’t the way to go to reduce the amount of carbon spewing into the atmosphere. Instead, it is not to destabilize what you have by prematurely taking gas offline.

Gas has certain useful qualities not the least of which is that it can be stored. Storage is the bugaboo of alternative energy. Batteries are good for a few hours at best and the other main way of storing energy, pumped storage, requires large expenditures, substantial engineering, and a usable site. It requires the creation of a big water impoundment, which will provide hydro when extra power is needed. It works, it is efficient, and it isn’t something that you build in a jiffy.

I have spent half a century writing about the electricity industry and when it comes to decarbonization, I can say that while many in the industry were doubtful about global warming at one time, the industry now is committed to eliminating carbon emissions by 2050.

The joker is storage or some other way of backing up the alternatives. That may be hydrogen, but a lot of research and engineering must take place before it flows through the pipes which now carry natural gas. Likewise, for small modular reactors.

The Economist, pointing to Europe, says that the Europeans have destabilized their grid by failing to prepare for the transition to alternatives, triggering a global natural gas shortage. Gas should be used sparingly and treasured. The trick is to throw out the bath water and save the baby.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

A very comfortable faith

The superyacht Azzam, which from 2013 to 2019 was the largest private yacht in the world.

For N.T.

The path to joy is faith in God,

The young man told his friend.

His joy was plain upon his face;

He hoped not to offend.

All night they talked, and on the morn,

When day dawned bright and hot,

He shook her hand and wished her well

And set out on his yacht.

By Felicia Nimue Ackerman, a poet and a Brown University philosophy professor. This poem is slightly revised from one that ran in Free Inquiry.

Harbour Court, the Newport, R.I. headquarters of the hyper-exclusive New York Yacht Club

'Neat and tractored'

The Green in Hanover, N.H.

“Although the smell of fresh-cut grass

is the same everywhere to me

it will always be Hanover {N.H.}:

rec soccer, someone’s tamed

plot of land neat and tractored…’’

— From “A Child’s Guide to Grasses,’’ by Jay Deshpande

Cod helped build New England

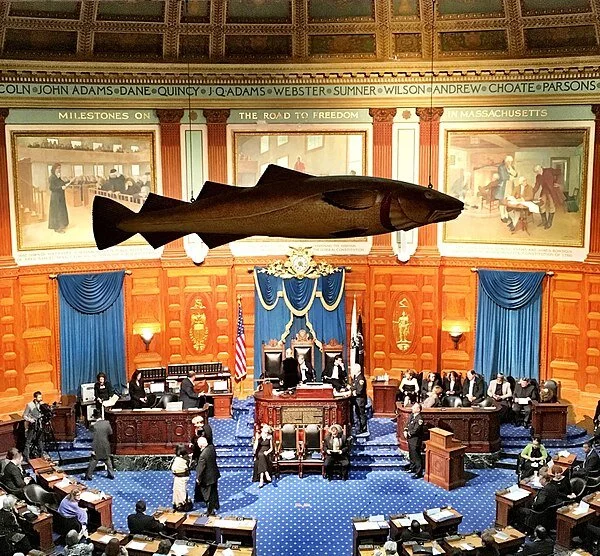

“The Sacred Cod” hangs above the Massachusetts House of Representatives chamber as a symbol of the fish’s historical importance to the prosperity of the state.

“By 1937, every British trawler had a wireless, electricity, and an echometer - the forerunner of sonar. If getting into fishing had required the kind of capital in past centuries that it cost in the twentieth century, cod would never have built a nation of middle-class, self-made entrepreneurs in New England.”

― From Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, by Mark Kurlansky

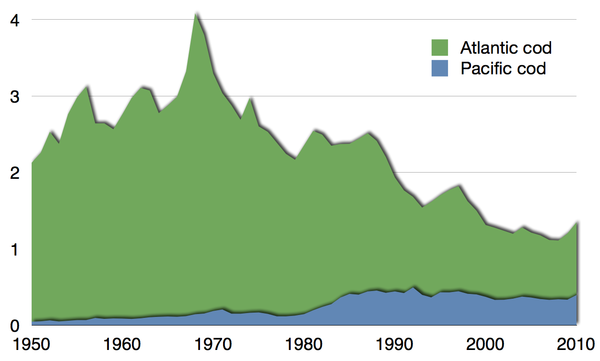

Showing embedded in light green the collapse of the northwest Atlantic cod fishery

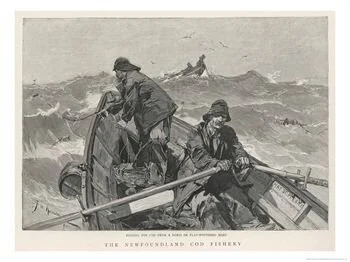

In the 19th Century, banks dories were carried aboard larger fishing schooners, and used for handlining cod on the Grand Banks and Georges Bank.

'The strangeness from my sight'

My long two-pointed ladder's sticking through a tree

Toward heaven still,

And there's a barrel that I didn't fill

Beside it, and there may be two or three

Apples I didn't pick upon some bough.

But I am done with apple-picking now.

Essence of winter sleep is on the night,

The scent of apples: I am drowsing off.

I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight

I got from looking through a pane of glass

I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough

And held against the world of hoary grass.

It melted, and I let it fall and break.

But I was well

Upon my way to sleep before it fell,

And I could tell

What form my dreaming was about to take.

Magnified apples appear and disappear,

Stem end and blossom end,

And every fleck of russet showing clear.

My instep arch not only keeps the ache,

It keeps the pressure of a ladder-round.

I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend.

And I keep hearing from the cellar bin

The rumbling sound

Of load on load of apples coming in.

For I have had too much

Of apple-picking: I am overtired

Of the great harvest I myself desired.

There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch,

Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall.

For all

That struck the earth,

No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble,

Went surely to the cider-apple heap

As of no worth.

One can see what will trouble

This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is.

Were he not gone,

The woodchuck could say whether it's like his

Long sleep, as I describe its coming on,

Or just some human sleep.

— “After Apple Picking,’’ by Robert Frost

No more renewals

Lincoln Theater (upper level) and the Maine Coast Bookshop at 158 Main Street, Damariscotta

“The circulation manager of Down East magazine sent a letter to Abner Mason of Damariscotta, Maine, notifying him that his subscription had expired. The notice came back a few days later with a scrawled message: “So’s Abner.’’

Judson D. Hale Sr., in Inside New England (1982)

Philip K. Howard: A way to make Biden infrastructure program work as hoped

Construction crew laying down asphalt over fiber-optic trench, in New York City

— Photo by Stealth Communications

The Bourne Bridge and the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge at sunset. The Bourne Bridge, at the canal’s western side, and the Sagamore Bridge, to the east, both built in the Thirties, are slated to be replaced.

President Biden’s breathtaking $5 trillion infrastructure agenda — about $50,000 in debt for each American family — is stalling on broad skepticism on both the goals and means of spending that money. There’s bipartisan agreement on at least some of the goals: Spending $1.2 trillion to fix roads, build new transmission lines, expand broadband, and provide clean water could improve American competitiveness as well as its environmental sustainability.

There’s a deal to be made here: Use this moment to overhaul how Washington spends money. Skeptics are correct that, otherwise, most of the money will go up in smoke. What’s needed is a new set of spending principles, based on the principle of commercial reasonableness, enforced by a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board.

The key to governing is implementation. Big talk in press conferences rarely results in success. Nor does throwing money at a problem. The chaos in Afghanistan reveals what happens when top-down dictates are not accompanied by a practical plan for executing the goal. But the Biden administration has no plan on how to implement its infrastructure proposals wisely.

What is certain is that, without reform, most of the infrastructure money will be wasted. Red tape, delays, rigid contracting rules, entitlements and other inefficiencies guarantee that American taxpayers will receive less than 50 cents of infrastructure value for each dollar. That’s optimistic. Comparative studies of infrastructure costs in developed countries show that public transit in the U.S. can be four times as expensive as in, say, Spain or France. A highway viaduct in Seattle cost three times more than a comparable project in France, and seven times more than one in Spain.

What causes the waste? No U.S. official has authority to use commonsense, at any point in the process, to build infrastructure sensibly. Other countries have “state capacity”— a euphemism for public departments where officials are given the authority to make contract and other decisions comparable to their counterparts in the private sector. In America, by contrast, officials’ responsibility is preempted by red tape.

Here are some of the main drivers of waste:

- Permitting can take years because no official has authority to 1) limit environmental reviews to important impacts; 2) resolve disagreements among competing agencies; or 3) expedite resolution of lawsuits. In our study Two Years, Not Ten Years we found that delay alone can more than double the effective cost of projects.

- Rigid procurement protocols strive to detail each nut and bolt in advance, limiting the flexibility needed to confront unanticipated issues inherent in any complex construction project. This leads to massive waste as well as costly change orders.

- Union collective-bargaining entitlements have accumulated over the decades, for example, requiring twice as many workers as needed to operate the tunneling machine for a New York subway. Work rules are designed not for safety or efficiency, but to provide compensation even where there’s no work.

- Legislative mandates further increase the cost of public projects. The “Buy American” laws can increase costs by 25 percent, sometimes more. The Davis-Bacon Act from 1931 increases labor costs by upwards of 20% over market by requiring “prevailing wages”— which is a euphemism for highest wage that can be justified. An army of Washington bureaucrats has the job of dictating wage rates and benefit packages in hundreds of construction job categories in each of 3,000 designated labor markets in the U.S.

- All these legal processes, rigidities and entitlements provide grounds for a lawsuit for any unhappy bidder, contractor, labor union, or environmental group. Lawsuits not only add costs to delay projects, but are commonly used as a weapon to extract payments and concessions that further raise the costs.

Thick rulebooks have supplanted human responsibility. Washington allocates money, with lots of legal strings. It then gives grants to states and localities, many of which are actuarily insolvent – precisely because they cannot manage their public unions and other interest groups. Time passes. Lawyers and consultants produce environmental impact statements. Various groups object and threaten lawsuits. Unions demand ever-greater benefits. Understaffed civil servants try to write procurement guidelines that anticipate every detail and eventuality. The low bidder wins, even if the bidder has a lousy record. Some infrastructure gets built, often badly, and always at a cost that far exceeds what a commercial builder would have paid. The waste here is a scandal — political leaders might as well take taxpayer money and throw it in the fireplace.

How should infrastructure be built? What causes waste in building infrastructure, as NYU’s Alon Levy puts it, is “rigid[ity], where what is needed is flexibility and empowerment” of officials with responsibility. Someone needs to be in charge of each project, and whoever’s in charge needs to have the flexibility to negotiate contracts, adapt to new conditions, and, above all, not to be hamstrung by unrelated requirements.

Building roads, bridges and power lines isn’t rocket science. Other countries and private companies know how to do this. Most public engineers know what performance standards are required. By the simple mechanism of empowering public servants to take responsibility, Levy found, other countries are able to “spend a fraction of what the US does on the same bridge or tunnel.”

Giving officials flexibility to use their judgment, however, requires a mechanism to overcome Americans’ distrust of government. That’s what keeps America’s byzantine bureaucracy in place. Any effort at reform is resisted by groups who argue “What if... an official is on the take?” “What if…the official is Robert Moses, and wants to bulldoze poor communities?”

Opponents to spending reform are mobilizing as I write. The $1.2 trillion Senate bill includes permitting reforms that seek to limit the permitting process to two years. But even this modest reform is under attack by “environmental justice” groups who argue that two years is insufficient to consider those issues. Similarly, a reform to expedite permits for interstate transmission lines is being vigorously opposed by the state energy regulators. They pluck the strings of distrust. But their real objection is that minimizing delay removes the legal veto which they use to extract lucrative benefits for themselves.

What’s needed to overcome distrust is a nonpartisan oversight body that is empowered to avoid waste and corruption. In other developed countries, most citizens accept official authority. But Americans don’t. Creating a trusted oversight institution means it can’t be in the control of either political party. An example are the nonpartisan “base-closing commissions” which decide which defense bases should be shuttered.

I propose a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board, analogous to oversight boards in Australia and other countries. Its responsibilities would be not to build infrastructure but to oversee and report on how infrastructure is built. Funding could still go through states, but only on condition that timelines and contracts meet standards of commercial reasonableness. No more featherbedding. No more payoffs. States would lose funding if they continued current practices.

The power of a trusted oversight body is exponentially greater than its size. The availability of accountability, not micromanagement, is the element that avoids waste while instilling trust and confidence that everyone is doing their part.

America is at an institutional crossroads. Nothing much works as it should because no official, or teacher, or hospital administrator, or manager, is authorized to make sensible choices. Pruning the jungle of red tape never works because the underlying premise is to avoid human judgment on the spot. The only solution is to replace the jungle with a simpler framework activated by human responsibility and accountability. But who will oversee those officials? That’s why a trusted oversight body is essential.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, author and chairman of Common Good, a bipartisan reform coalition. This piece first ran in The Hill.

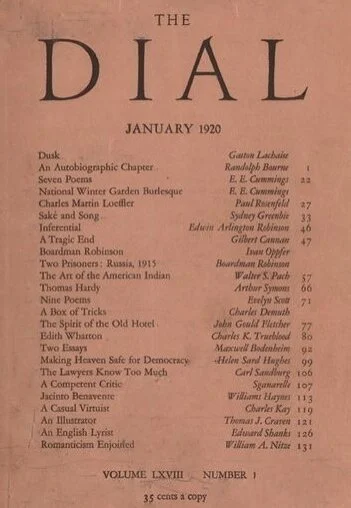

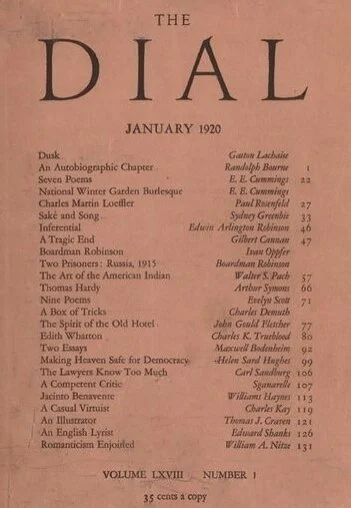

Information on Scofield Thayer?

If anyone has information on Scofield Thayer’s (1889-1982) time at Butler Hospital, in Providence, where he was declared “insane” by Dr. Arthur H. Ruggles, M.D., superintendent of that hospital, and put under the guardianship of a partner at the Providence law firm of Edwards & Angell, please contact Robert Whitcomb at rwhitcomb4@cox.net.

Thayer was a very wealthy American editor, writer and publisher, best known for his art collection, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and as a publisher and editor of the magazine The Dial during the 1920s. He published many emerging American and European writers and visual artists.

The erosion of the college 'bookstore'

The Harvard /MIT Coop's (aka Harvard Cooperative Society) main store on Harvard Square was built in 1924 and designed by Perry, Shaw & Hepburn in the Colonial Revival style.

—Photo by Beyond My Ken

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s sad to see how college bookstores, once major and charming attractions in New England’s many college towns, are being ruined by the chains that have bought them. There are fewer and fewer books as they’re replaced by the likes of logoed sweatshirts, tacky tchotchkes and other junk.

The Brown “Bookstore’’ is particularly depressing. If you want to go to a real bookstore in Providence, I recommend Symposium Books, downtown, or Books on the Square and Paper Nautilus, on Wayland Square.

I guess that the Internet, by taking away the monopoly on textbook sales, helped drive a stake through the old college-bookstore business model. Even the once grand Harvard/MIT Coop bookstore is a skeleton of its former self.

Reading on a screen is not the same as reading on paper, which is easier on the eyes and better supports comprehension and memory of the material. I thought of this the other day in the Route 128 Amtrak/MBTA station, where there’s no longer a newsstand. For that matter, other than one helpful and lonely Amtrak clerk there are no longer any service people to buy tickets or coffee from, or ask a train-schedule question. Heading to the paperless and, for some, serviceless society.

Emerson College occupies this row of buildings across from the corner of Boston Common

— Photo by John Phelan

Even in the pouring rain in downtown Boston last Tuesday, it was fun to see a dozen Emerson College film students shooting scenes on the sidewalk across from the Common. Most appeared to be of East Asian ancestry and half of them had haired dyed green, purple or blue.

Don’t kick it

“Harrow 2” (iron), by Tom Waldron, in “Compelling Structure,’’ a joint show with Patrik Grijalvo, at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., through Nov. 13.

The Waveny estate in New Canaan, now a town park. The park's centerpiece is this “castle," built in 1912 by Lewis Lapham, a founder of the oil company Texaco, as mostly a summer place. It’s surrounded by 300 acres of fields, ponds and trails.

David Warsh: The exciting lives of former newspapermen

— Photo by Knowtex

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

After the Internet laid waste to old monopolies on printing presses and broadcast towers, new opportunities arose for inhabitants of newsrooms. That much I knew from personal experience. With it in mind, I have been reading Spooked: The Trump Dossier, Black Cube, and the Rise of Private Spies (Harper, 2021), by Barry Meier, a former reporter for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Meier also wrote Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Story of Addiction and Death (Rodale, 2003), the first book to dig in to the story of the Sackler family, before Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty (Doubleday, 2021), by New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe, eclipsed it earlier this year. In other words, Meier knows his way around. So does Lincoln Millstein, proprietor of The Quietside Journal, a hyperlocal Web site covering three small towns on the southwest side of Mt. Desert Island, in Downeast Maine.

Meier’s book is essentially a story about Glenn Simpson, a colorful star investigative reporter for the WSJ who quit in 2009 to establish Fusion GPS, a private investigative firm for hire. It was Fusion GPS that, while working first for Republican candidates in early 2016, then for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, hired former MI6 agent Christopher Steele to investigate Donald Trump’s activities in Russia.

Meier, a careful reporter and vivid writer, doesn’t think much of Simpson, still less of Steele, but I found the book frustrating: there were too many stories about bad behavior in the far-flung private intelligence industry, too loosely stitched together, to make possible a satisfying conclusion about the circumstances in which the Steele dossier surfaced, other than information, proven or not, once assembled and packaged, wants to be free. William Cohan’s NYT review of Spooked was helpful: “[W]e are left, in the end, with a gun that doesn’t really go off.”

Meier did include in his book (and repeat in a NYT op-ed) a telling vignette about Fusion GPS co-founder Peter Fritsch, another former WSJ staffer who in his 15-year career at the paper had served as bureau chief in several cities around the world. At one point, Fritsch phones WSJ reporter John Carreyrou, ostensibly seeking guidance on the reputation of a whistleblower at a medical firm – without revealing that Fusion GPS had begun working for Elizabeth Holmes, of whose blood-testing start-up, Theranos, Carreyrou had begun an investigation.

Fritsch’s further efforts to undermine Carreyrou’s investigation failed. Simpson and Fritch tell their story of the Steele dossier in Crime in Progress (2019, Random House.) I’d like to someday read more personal accounts of their experiences in the private spy trade, I thought, as I put Spooked and Crime in Progress back on the shelf Given the authors’ new occupations, it doesn’t seem likely those accounts will be written.

By then, Meier’s story had got me thinking about Carreyrou himself. His brilliant reporting for the WSJ, and his 2018 best-seller, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (Knopf, 2018, led to Elizabeth Holmes’s trial on criminal charges that began last month in San Jose. Thanks to Twitter, I found, within an hour of its appearance, this interview with Carreyrou, now covering the trial online as an independent journalist.

My head spun at the thought of the leg-push and tradecraft required to practice journalism at these high altitudes. The changes wrought by the advent of the Web and social media have fundamentally expanded the business beyond the days when newspapers and broadcast news were the primary producers of news. In 1972, when I went to work for the WSJ, for example, the entire paper ordinarily contained only four bylines a day.

So I turned with some relief to The Quietside Journal, the Web site where retired Hearst executive Lincoln Millstein covers events in three small towns on Mt. Desert Island, Maine, for some 17,000 weekly readers. In an illuminating story about his enterprise, Millstein told Rick Edmonds, of the Poynter Institute, that he works six days a week, again employing pretty much the same skills he acquired when he covered Middletown, Conn., for The Hartford Courant forty years ago. (Millstein put the Economic Principals column in business in 1984, not long after he arrived as deputy business editor at The Boston Globe).

My case is different. Like many newspaper journalists in the 1980s, I worked four or five days a week at my day job and spent vacations and weekends writing books. I quit the day job in 2002, but kept the column and finished the book. (It was published in 2006 as Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery).

Economic Principals subscribers have kept the office open ever since; I gradually found another book to write; and so it has worked out pretty well. The ratio of time spent is reversed: four days a week for the book, two days for the column, producing, as best I can judge, something worth reading on Sunday morning. Eight paragraphs, sometimes more, occasionally fewer: It’s a living, an opportunity to keep after the story, still, as we used to say, the sport of kings.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

‘Ever-evolving aggregate state’

“Shiver Me Timbers,’’ by Michael MacMahon, in his show “Wrack Line,’’ at the Umbrella Arts Center, Concord, Mass., through Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“Wrack lines are linear piles of debris (both natural and manmade) that become situated on the edge of the landscape. The result of their coming in contact with and carried along by the forces of incoming waves and tides.

“The merging of economic need, curiosity, seen and unseen forces have brought peoples from different cultures and communities into contact across great distances. Whether through clashes or cooperative endeavors, these convergences have brought about the adaptation of living within a contemporary culture that is an ever-evolving aggregate state. Ideas of the self/home/the domestic space and the landscape come together in the paintings on view.’’

Debris in a wrack line