A very comfortable faith

The superyacht Azzam, which from 2013 to 2019 was the largest private yacht in the world.

For N.T.

The path to joy is faith in God,

The young man told his friend.

His joy was plain upon his face;

He hoped not to offend.

All night they talked, and on the morn,

When day dawned bright and hot,

He shook her hand and wished her well

And set out on his yacht.

By Felicia Nimue Ackerman, a poet and a Brown University philosophy professor. This poem is slightly revised from one that ran in Free Inquiry.

Harbour Court, the Newport, R.I. headquarters of the hyper-exclusive New York Yacht Club

'Neat and tractored'

The Green in Hanover, N.H.

“Although the smell of fresh-cut grass

is the same everywhere to me

it will always be Hanover {N.H.}:

rec soccer, someone’s tamed

plot of land neat and tractored…’’

— From “A Child’s Guide to Grasses,’’ by Jay Deshpande

Cod helped build New England

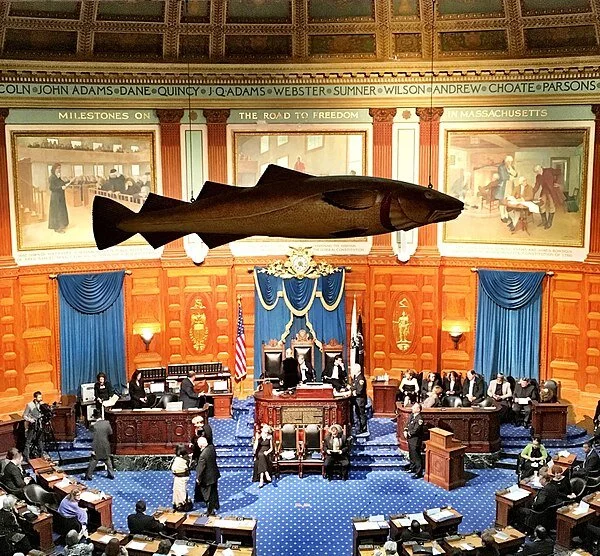

“The Sacred Cod” hangs above the Massachusetts House of Representatives chamber as a symbol of the fish’s historical importance to the prosperity of the state.

“By 1937, every British trawler had a wireless, electricity, and an echometer - the forerunner of sonar. If getting into fishing had required the kind of capital in past centuries that it cost in the twentieth century, cod would never have built a nation of middle-class, self-made entrepreneurs in New England.”

― From Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, by Mark Kurlansky

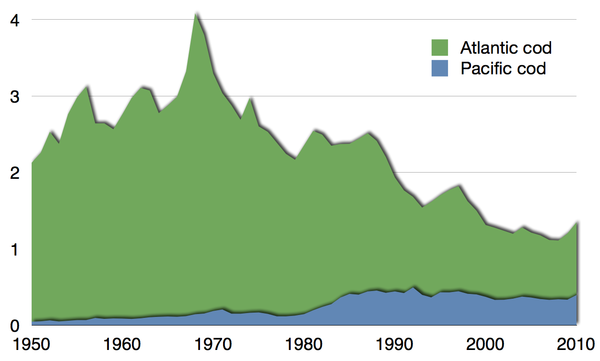

Showing embedded in light green the collapse of the northwest Atlantic cod fishery

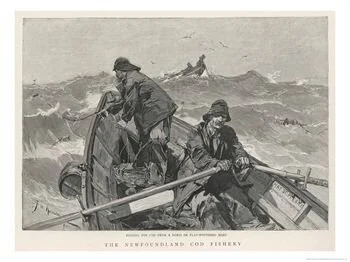

In the 19th Century, banks dories were carried aboard larger fishing schooners, and used for handlining cod on the Grand Banks and Georges Bank.

'The strangeness from my sight'

My long two-pointed ladder's sticking through a tree

Toward heaven still,

And there's a barrel that I didn't fill

Beside it, and there may be two or three

Apples I didn't pick upon some bough.

But I am done with apple-picking now.

Essence of winter sleep is on the night,

The scent of apples: I am drowsing off.

I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight

I got from looking through a pane of glass

I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough

And held against the world of hoary grass.

It melted, and I let it fall and break.

But I was well

Upon my way to sleep before it fell,

And I could tell

What form my dreaming was about to take.

Magnified apples appear and disappear,

Stem end and blossom end,

And every fleck of russet showing clear.

My instep arch not only keeps the ache,

It keeps the pressure of a ladder-round.

I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend.

And I keep hearing from the cellar bin

The rumbling sound

Of load on load of apples coming in.

For I have had too much

Of apple-picking: I am overtired

Of the great harvest I myself desired.

There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch,

Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall.

For all

That struck the earth,

No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble,

Went surely to the cider-apple heap

As of no worth.

One can see what will trouble

This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is.

Were he not gone,

The woodchuck could say whether it's like his

Long sleep, as I describe its coming on,

Or just some human sleep.

— “After Apple Picking,’’ by Robert Frost

No more renewals

Lincoln Theater (upper level) and the Maine Coast Bookshop at 158 Main Street, Damariscotta

“The circulation manager of Down East magazine sent a letter to Abner Mason of Damariscotta, Maine, notifying him that his subscription had expired. The notice came back a few days later with a scrawled message: “So’s Abner.’’

Judson D. Hale Sr., in Inside New England (1982)

Philip K. Howard: A way to make Biden infrastructure program work as hoped

Construction crew laying down asphalt over fiber-optic trench, in New York City

— Photo by Stealth Communications

The Bourne Bridge and the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge at sunset. The Bourne Bridge, at the canal’s western side, and the Sagamore Bridge, to the east, both built in the Thirties, are slated to be replaced.

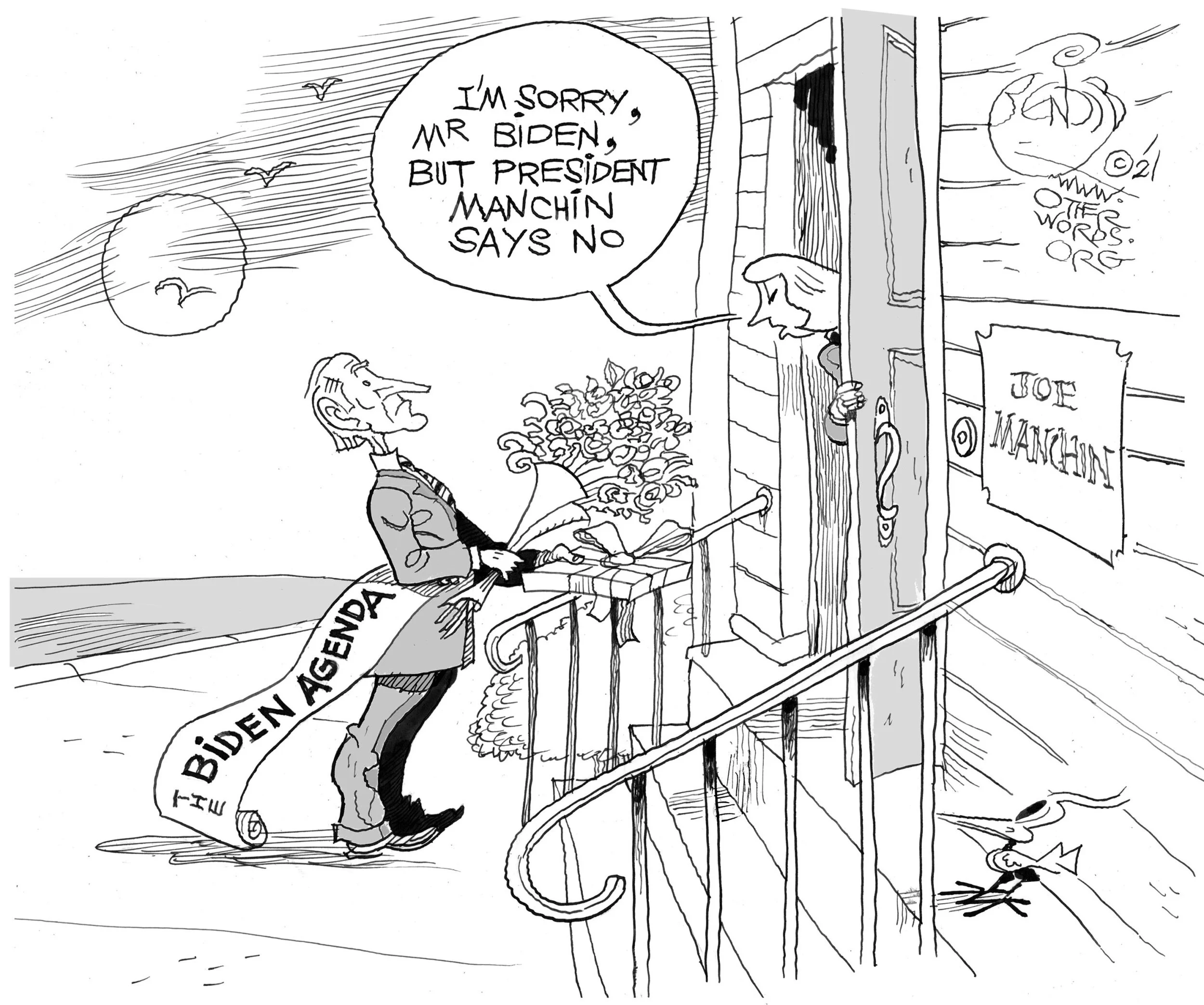

President Biden’s breathtaking $5 trillion infrastructure agenda — about $50,000 in debt for each American family — is stalling on broad skepticism on both the goals and means of spending that money. There’s bipartisan agreement on at least some of the goals: Spending $1.2 trillion to fix roads, build new transmission lines, expand broadband, and provide clean water could improve American competitiveness as well as its environmental sustainability.

There’s a deal to be made here: Use this moment to overhaul how Washington spends money. Skeptics are correct that, otherwise, most of the money will go up in smoke. What’s needed is a new set of spending principles, based on the principle of commercial reasonableness, enforced by a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board.

The key to governing is implementation. Big talk in press conferences rarely results in success. Nor does throwing money at a problem. The chaos in Afghanistan reveals what happens when top-down dictates are not accompanied by a practical plan for executing the goal. But the Biden administration has no plan on how to implement its infrastructure proposals wisely.

What is certain is that, without reform, most of the infrastructure money will be wasted. Red tape, delays, rigid contracting rules, entitlements and other inefficiencies guarantee that American taxpayers will receive less than 50 cents of infrastructure value for each dollar. That’s optimistic. Comparative studies of infrastructure costs in developed countries show that public transit in the U.S. can be four times as expensive as in, say, Spain or France. A highway viaduct in Seattle cost three times more than a comparable project in France, and seven times more than one in Spain.

What causes the waste? No U.S. official has authority to use commonsense, at any point in the process, to build infrastructure sensibly. Other countries have “state capacity”— a euphemism for public departments where officials are given the authority to make contract and other decisions comparable to their counterparts in the private sector. In America, by contrast, officials’ responsibility is preempted by red tape.

Here are some of the main drivers of waste:

- Permitting can take years because no official has authority to 1) limit environmental reviews to important impacts; 2) resolve disagreements among competing agencies; or 3) expedite resolution of lawsuits. In our study Two Years, Not Ten Years we found that delay alone can more than double the effective cost of projects.

- Rigid procurement protocols strive to detail each nut and bolt in advance, limiting the flexibility needed to confront unanticipated issues inherent in any complex construction project. This leads to massive waste as well as costly change orders.

- Union collective-bargaining entitlements have accumulated over the decades, for example, requiring twice as many workers as needed to operate the tunneling machine for a New York subway. Work rules are designed not for safety or efficiency, but to provide compensation even where there’s no work.

- Legislative mandates further increase the cost of public projects. The “Buy American” laws can increase costs by 25 percent, sometimes more. The Davis-Bacon Act from 1931 increases labor costs by upwards of 20% over market by requiring “prevailing wages”— which is a euphemism for highest wage that can be justified. An army of Washington bureaucrats has the job of dictating wage rates and benefit packages in hundreds of construction job categories in each of 3,000 designated labor markets in the U.S.

- All these legal processes, rigidities and entitlements provide grounds for a lawsuit for any unhappy bidder, contractor, labor union, or environmental group. Lawsuits not only add costs to delay projects, but are commonly used as a weapon to extract payments and concessions that further raise the costs.

Thick rulebooks have supplanted human responsibility. Washington allocates money, with lots of legal strings. It then gives grants to states and localities, many of which are actuarily insolvent – precisely because they cannot manage their public unions and other interest groups. Time passes. Lawyers and consultants produce environmental impact statements. Various groups object and threaten lawsuits. Unions demand ever-greater benefits. Understaffed civil servants try to write procurement guidelines that anticipate every detail and eventuality. The low bidder wins, even if the bidder has a lousy record. Some infrastructure gets built, often badly, and always at a cost that far exceeds what a commercial builder would have paid. The waste here is a scandal — political leaders might as well take taxpayer money and throw it in the fireplace.

How should infrastructure be built? What causes waste in building infrastructure, as NYU’s Alon Levy puts it, is “rigid[ity], where what is needed is flexibility and empowerment” of officials with responsibility. Someone needs to be in charge of each project, and whoever’s in charge needs to have the flexibility to negotiate contracts, adapt to new conditions, and, above all, not to be hamstrung by unrelated requirements.

Building roads, bridges and power lines isn’t rocket science. Other countries and private companies know how to do this. Most public engineers know what performance standards are required. By the simple mechanism of empowering public servants to take responsibility, Levy found, other countries are able to “spend a fraction of what the US does on the same bridge or tunnel.”

Giving officials flexibility to use their judgment, however, requires a mechanism to overcome Americans’ distrust of government. That’s what keeps America’s byzantine bureaucracy in place. Any effort at reform is resisted by groups who argue “What if... an official is on the take?” “What if…the official is Robert Moses, and wants to bulldoze poor communities?”

Opponents to spending reform are mobilizing as I write. The $1.2 trillion Senate bill includes permitting reforms that seek to limit the permitting process to two years. But even this modest reform is under attack by “environmental justice” groups who argue that two years is insufficient to consider those issues. Similarly, a reform to expedite permits for interstate transmission lines is being vigorously opposed by the state energy regulators. They pluck the strings of distrust. But their real objection is that minimizing delay removes the legal veto which they use to extract lucrative benefits for themselves.

What’s needed to overcome distrust is a nonpartisan oversight body that is empowered to avoid waste and corruption. In other developed countries, most citizens accept official authority. But Americans don’t. Creating a trusted oversight institution means it can’t be in the control of either political party. An example are the nonpartisan “base-closing commissions” which decide which defense bases should be shuttered.

I propose a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board, analogous to oversight boards in Australia and other countries. Its responsibilities would be not to build infrastructure but to oversee and report on how infrastructure is built. Funding could still go through states, but only on condition that timelines and contracts meet standards of commercial reasonableness. No more featherbedding. No more payoffs. States would lose funding if they continued current practices.

The power of a trusted oversight body is exponentially greater than its size. The availability of accountability, not micromanagement, is the element that avoids waste while instilling trust and confidence that everyone is doing their part.

America is at an institutional crossroads. Nothing much works as it should because no official, or teacher, or hospital administrator, or manager, is authorized to make sensible choices. Pruning the jungle of red tape never works because the underlying premise is to avoid human judgment on the spot. The only solution is to replace the jungle with a simpler framework activated by human responsibility and accountability. But who will oversee those officials? That’s why a trusted oversight body is essential.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, author and chairman of Common Good, a bipartisan reform coalition. This piece first ran in The Hill.

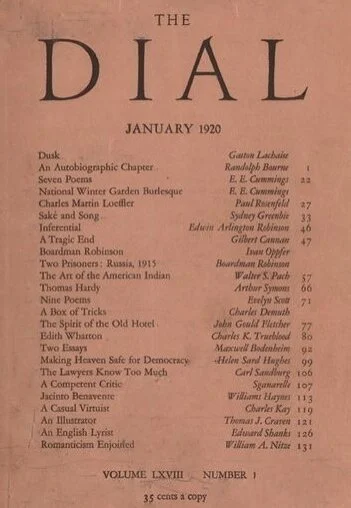

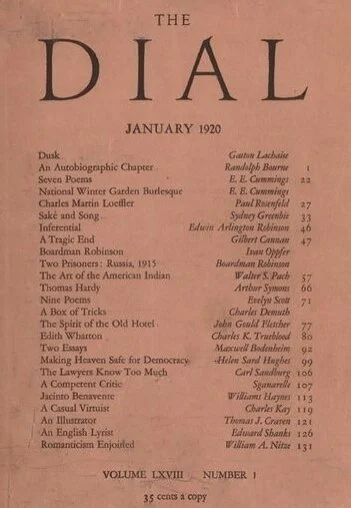

Information on Scofield Thayer?

If anyone has information on Scofield Thayer’s (1889-1982) time at Butler Hospital, in Providence, where he was declared “insane” by Dr. Arthur H. Ruggles, M.D., superintendent of that hospital, and put under the guardianship of a partner at the Providence law firm of Edwards & Angell, please contact Robert Whitcomb at rwhitcomb4@cox.net.

Thayer was a very wealthy American editor, writer and publisher, best known for his art collection, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and as a publisher and editor of the magazine The Dial during the 1920s. He published many emerging American and European writers and visual artists.

The erosion of the college 'bookstore'

The Harvard /MIT Coop's (aka Harvard Cooperative Society) main store on Harvard Square was built in 1924 and designed by Perry, Shaw & Hepburn in the Colonial Revival style.

—Photo by Beyond My Ken

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s sad to see how college bookstores, once major and charming attractions in New England’s many college towns, are being ruined by the chains that have bought them. There are fewer and fewer books as they’re replaced by the likes of logoed sweatshirts, tacky tchotchkes and other junk.

The Brown “Bookstore’’ is particularly depressing. If you want to go to a real bookstore in Providence, I recommend Symposium Books, downtown, or Books on the Square and Paper Nautilus, on Wayland Square.

I guess that the Internet, by taking away the monopoly on textbook sales, helped drive a stake through the old college-bookstore business model. Even the once grand Harvard/MIT Coop bookstore is a skeleton of its former self.

Reading on a screen is not the same as reading on paper, which is easier on the eyes and better supports comprehension and memory of the material. I thought of this the other day in the Route 128 Amtrak/MBTA station, where there’s no longer a newsstand. For that matter, other than one helpful and lonely Amtrak clerk there are no longer any service people to buy tickets or coffee from, or ask a train-schedule question. Heading to the paperless and, for some, serviceless society.

Emerson College occupies this row of buildings across from the corner of Boston Common

— Photo by John Phelan

Even in the pouring rain in downtown Boston last Tuesday, it was fun to see a dozen Emerson College film students shooting scenes on the sidewalk across from the Common. Most appeared to be of East Asian ancestry and half of them had haired dyed green, purple or blue.

Don’t kick it

“Harrow 2” (iron), by Tom Waldron, in “Compelling Structure,’’ a joint show with Patrik Grijalvo, at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., through Nov. 13.

The Waveny estate in New Canaan, now a town park. The park's centerpiece is this “castle," built in 1912 by Lewis Lapham, a founder of the oil company Texaco, as mostly a summer place. It’s surrounded by 300 acres of fields, ponds and trails.

David Warsh: The exciting lives of former newspapermen

— Photo by Knowtex

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

After the Internet laid waste to old monopolies on printing presses and broadcast towers, new opportunities arose for inhabitants of newsrooms. That much I knew from personal experience. With it in mind, I have been reading Spooked: The Trump Dossier, Black Cube, and the Rise of Private Spies (Harper, 2021), by Barry Meier, a former reporter for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Meier also wrote Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Story of Addiction and Death (Rodale, 2003), the first book to dig in to the story of the Sackler family, before Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty (Doubleday, 2021), by New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe, eclipsed it earlier this year. In other words, Meier knows his way around. So does Lincoln Millstein, proprietor of The Quietside Journal, a hyperlocal Web site covering three small towns on the southwest side of Mt. Desert Island, in Downeast Maine.

Meier’s book is essentially a story about Glenn Simpson, a colorful star investigative reporter for the WSJ who quit in 2009 to establish Fusion GPS, a private investigative firm for hire. It was Fusion GPS that, while working first for Republican candidates in early 2016, then for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, hired former MI6 agent Christopher Steele to investigate Donald Trump’s activities in Russia.

Meier, a careful reporter and vivid writer, doesn’t think much of Simpson, still less of Steele, but I found the book frustrating: there were too many stories about bad behavior in the far-flung private intelligence industry, too loosely stitched together, to make possible a satisfying conclusion about the circumstances in which the Steele dossier surfaced, other than information, proven or not, once assembled and packaged, wants to be free. William Cohan’s NYT review of Spooked was helpful: “[W]e are left, in the end, with a gun that doesn’t really go off.”

Meier did include in his book (and repeat in a NYT op-ed) a telling vignette about Fusion GPS co-founder Peter Fritsch, another former WSJ staffer who in his 15-year career at the paper had served as bureau chief in several cities around the world. At one point, Fritsch phones WSJ reporter John Carreyrou, ostensibly seeking guidance on the reputation of a whistleblower at a medical firm – without revealing that Fusion GPS had begun working for Elizabeth Holmes, of whose blood-testing start-up, Theranos, Carreyrou had begun an investigation.

Fritsch’s further efforts to undermine Carreyrou’s investigation failed. Simpson and Fritch tell their story of the Steele dossier in Crime in Progress (2019, Random House.) I’d like to someday read more personal accounts of their experiences in the private spy trade, I thought, as I put Spooked and Crime in Progress back on the shelf Given the authors’ new occupations, it doesn’t seem likely those accounts will be written.

By then, Meier’s story had got me thinking about Carreyrou himself. His brilliant reporting for the WSJ, and his 2018 best-seller, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (Knopf, 2018, led to Elizabeth Holmes’s trial on criminal charges that began last month in San Jose. Thanks to Twitter, I found, within an hour of its appearance, this interview with Carreyrou, now covering the trial online as an independent journalist.

My head spun at the thought of the leg-push and tradecraft required to practice journalism at these high altitudes. The changes wrought by the advent of the Web and social media have fundamentally expanded the business beyond the days when newspapers and broadcast news were the primary producers of news. In 1972, when I went to work for the WSJ, for example, the entire paper ordinarily contained only four bylines a day.

So I turned with some relief to The Quietside Journal, the Web site where retired Hearst executive Lincoln Millstein covers events in three small towns on Mt. Desert Island, Maine, for some 17,000 weekly readers. In an illuminating story about his enterprise, Millstein told Rick Edmonds, of the Poynter Institute, that he works six days a week, again employing pretty much the same skills he acquired when he covered Middletown, Conn., for The Hartford Courant forty years ago. (Millstein put the Economic Principals column in business in 1984, not long after he arrived as deputy business editor at The Boston Globe).

My case is different. Like many newspaper journalists in the 1980s, I worked four or five days a week at my day job and spent vacations and weekends writing books. I quit the day job in 2002, but kept the column and finished the book. (It was published in 2006 as Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery).

Economic Principals subscribers have kept the office open ever since; I gradually found another book to write; and so it has worked out pretty well. The ratio of time spent is reversed: four days a week for the book, two days for the column, producing, as best I can judge, something worth reading on Sunday morning. Eight paragraphs, sometimes more, occasionally fewer: It’s a living, an opportunity to keep after the story, still, as we used to say, the sport of kings.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

‘Ever-evolving aggregate state’

“Shiver Me Timbers,’’ by Michael MacMahon, in his show “Wrack Line,’’ at the Umbrella Arts Center, Concord, Mass., through Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“Wrack lines are linear piles of debris (both natural and manmade) that become situated on the edge of the landscape. The result of their coming in contact with and carried along by the forces of incoming waves and tides.

“The merging of economic need, curiosity, seen and unseen forces have brought peoples from different cultures and communities into contact across great distances. Whether through clashes or cooperative endeavors, these convergences have brought about the adaptation of living within a contemporary culture that is an ever-evolving aggregate state. Ideas of the self/home/the domestic space and the landscape come together in the paintings on view.’’

Debris in a wrack line

Caitlin Faulds: Sacred lotus joins other invasives to threaten waterways

A shroud of invasive sacred lotuses blocks in the edge of Meshanticut Pond, at Meshanticut State Park, in Cranston, R.I. Despite previous attempts to cull their growth, they came back in full force this year.

— Photo by Caitlin Faulds/ecoRI News photos)

Sacred lotus flower

Fr0m ecoRI News (ecori.org)

CRANSTON, R.I.

The pond looks like a painting. A small boat and a family of swans — two juveniles, two adults — marked by gentle wakes on a glassy surface. Early red leaves gracing the tops of periphery trees, late-season lotuses still framing from the edge.

But at Meshanticut Pond, there is a battle brewing on the water between the boat and sacred lotus.

In the past seven years, after a Cranston resident planted it in memory of a relative, the lotus — an invasive species, endemic to Asia and relatively new to Rhode Island waterways — has overtaken the pond. Just a few oversized leaves at first, now hordes of water lilies encroaching on three sides of the shore.

But according to Keith Gazaille, project manager with SOLitude Lake Management — a water-quality and waterbody-restoration company that works throughout the eastern United States — it’s not the only aquatic invasive crowding out native plants in the pond.

Gazaille and aquatic technician Tanner Poole are out on Meshanticut Pond on a stormy Tuesday morning to continue the fight against a trifecta of invasives: variable watermilfoil, fanwort and sacred lotus.

“The lotus and the other invasive plants have the ability to really outcompete a lot of the native plant species,” Gazaille said. “It really reduces the diversity of the habitat.”

It provides some habitat for fish and other aquatic life. But a dense canopy of invasives reduces the variability of the habitat, and it can wreak havoc on the levels of dissolved oxygen below the canopy. As the crowd of plants switches between oxygen production and respiration, large fluctuations in oxygen can be a stressor for aquatic life.

A team was out here last year, Gazaille said, trying to ward off the growth. But the invasives have stuck around, determined.

“The growth has gotten to the point where it has raised the attention of residents and the city,” Gazaille said. “And so, I think there was a request to take some action.”

Today, he and Poole will be boating over half the pond, spraying a contact herbicide below the water to try once again to stop the spreading milfoil and fanwort.

“There’s not a lot of good — given the expanse of the infestation — non-chemical strategies, unfortunately,” he said.

Harvesting and manual removal of both plants can be counterproductive, according to Gazaille. They reproduce by fragmentation, he said, “so as they potentially break during those activities, you could be worsening the situation, and potentially spreading plant fragments downstream.”

The best option, he said, is to spray a contact herbicide on the vegetative portion of the plant. It is best to do this in the early fall, before they enter a natural stage of auto-fragmentation. Eliminating them now reduces the risk of downstream infestation. The treatment will leave the root intact, Gazaille said, but through repetitive treatment there can be a slow reduction in growth density.

“The lotus is another animal altogether,” Gazaille said.

They had hoped to spray its protruding leaves, too, with a systemic herbicide. That would spread through the plant, “kill the rhizome and prevent return of the plants all year,” he said.

But the impending rain would wash the chemicals off too early. They need 3-6 clear hours for it to be effective. They’ll be back in the next few weeks to finish off the other half of the pond and deal with the lotuses.

A late-season crowd of sacred lotuses and clouds of algae overtake swath of Meshanticut Pond.

Compared to some areas of the South, where the growing season is unimpeded by freezing temperatures, Gazaille has seen lotus completely overtake a water system. But for the Northeast, he said that Meshanticut Pond is dealing with a moderate- to high-level infestation.

They are trying to stop it there, but “the sacred lotus has been particularly hard to kill,” according to Christine Dudley, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s deputy chief of freshwater and diadromous fisheries.

And beyond Meshanticut, the battle against invasives is only getting worse.

“All over the world, really, but all over New England ponds are getting more and more infestations of invasives and more and more heavy algae and weed growth,” Dudley said.

There are a lot of different factors to blame. Usage around ponds has changed over the years, many have gotten more and more built up. Rising temperatures, eutrophication, lawn chemical use, released aquarium species, urban growth, and overburdened and leaching cesspools all play a role.

“It’s very difficult to tell someone that they can’t have a nice yard, or have a bigger house or a nicer house on a lake,” Dudley said. “But they really have to look to what’s happened over the years that has changed.”

There is legislation in the works to stop the sale of aquatic invasive species, but the reality on Meshanticut Pond and other Rhode Island waterbodies is invasives have already taken root. And the state can’t treat them all — it’s too expensive.

Cost varies based on the size, the weed type, the chemicals used, and the staff time needed. The 12-acre Meshanticut Pond alone cost $6,685 to treat, Dudley said — a price tag picked up by a federal grant program for habitat restoration.

Each year, DEM makes a list of priority treatment sites — based on which are in the worst shape, which are stocked with fish, and which bring in the most complaints, among other variables. But without behavior change and public attention to the causes, Dudley only sees the problem getting worse and a long road ahead as far as invasive treatments go.

“As far as I can see, it’ll be a continuing thing that we’ll have to fight and battle,” she said. “And … it’s not cheap.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

John O. Harney: Boston Fed chief departs and other regional comings and goings

The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston is the tall building at the left.

From The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Boston Fed President and CEO Eric S. Rosengren, who had long planned to retire in June 2022, left the post Sept. 30 to deal with a worsening kidney condition. Rosengren announced that he has had the condition for many years and qualified for the kidney-transplant list in June 2020.

Rosengren worked 35 years at the Boston Fed and 14 as its president. Among his accomplishments, he championed the bank’s outreach to low- and moderate-income communities, hosted foreclosure-prevention workshops during the Great Recession, created a grant competition to support post-industrial New England communities and helped lead the Federal Reserve’s “Racism and the Economy” forums. Rosengren made the Boston Fed a key collaborator with NEBHE, including giving the keynote address at NEBHE’s major 2011 “New England Works” Summit on Bridging Higher Education and the Workforce. The Boston Fed announced that First Vice President and chief operating officer Kenneth C. Montgomery will serve as interim president and CEO.

The University of Rhode Island appointed Carlos Lopez Estrada, deputy director of administration and senior adviser to Pawtucket Mayor Donald R. Grebien, and Lauren Broccoli Burgess, a registered lobbyist and assistant director of government relations for the American Veterinary Medical Association, as the university’s directors of legislative and government relations. Lopez Estrada will focus on state and regional collaborations and Brocolli Burgess on federal government relations.

Lasell University appointed Lynne Celli as dean of graduate and professional studies. Celli joins Lasell from Endicott College, where she served as executive director of professional education and leadership, dean of graduate professional education, and associate dean for graduate education programs. She is also the former superintendent for Swampscott (Mass.) Public Schools.

Berkshire Community College (BCC) appointed Maureen McLaughlin as director of strategic initiatives. McLaughlin spent more than 20 years in the high-tech industry working on IPOs and acquisitions, as well as 10 years in public elementary schools supporting severe special needs students and students in crisis. BCC announced McLaughlin’s appointment among 10 new staff and faculty members.

Yale New Haven Health (YNHH) CEO Marna Borgstrom announced that she will retire next spring. She will be succeeded as head of the regional hospital system by current YNHH President and former Hospital of Saint Raphael CEO Christopher O’Connor.

— Photo by Beyond My Ken

The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) named Kristy Edmunds as its new director, succeeding founding director Joseph Thompson, who retired in late 2020 after 32 years leading the North Adams. Mass., museum. Edmunds has served as executive and artistic director at UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance since 2011.

John O. Harney is executive editor of NEBHE’s New England Journal of Higher Education.

Before global warming

Plymouth Rock, where the Pilgrims almost certainly did not land first in what became the colony of Plymouth Plantation.

“They fell upon an ungenial climate, where there were nine months of winter and three months of cold weather, and that called out the best energies of the men, and of the women too, to get a mere subsistence out of the soil, with such a climate. In their efforts to do that they cultivated industry and frugality at the same time — which is the real foundation of the greatness of the Pilgrims.’’

— Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), U.S. president and Civil War general, in a speech at the Dec. 22, 1880 New England Society dinner.

Chris Powell: Left-wing Democrats’ ‘open borders’; give up on Haiti, etc.

Haitian coat of arms

MANCHESTER, Conn.

While President Biden, Connectiut Gov. Ned Lamont and their administrations cajole and coerce people to get vaccinated against the virus epidemic despite fears that the vaccines are really still experimental, the president's administration has just admitted to the country about 12,000 Haitians without documentation of vaccination and without virus testing.

{Editor’s note: Some southern New England cities have large numbers of Haitians and Haitian-Americans.}

U.S. citizens are finding that they need "vaccine passports" within their own country, but no such requirement is being made of foreigners crossing the southern border, either illegally or claiming refugee status.

Why has this been happening?

First, of course, it's because the Haitians who flash-mobbed the highway bridge in Del Rio, Texas, and other irregular border crossers have been confident that the Biden administration will not enforce immigration law. They have been proven correct.

Second, it has been happening because the Democratic Party, which now controls the federal government, can't face down its far-left faction, which favors open borders as moral principle, even now that having open borders means disregarding a more recent moral principle of the left -- vaccination coercion. That far-left faction long has ruled the party in Connecticut and so Connecticut has become a "sanctuary state," obstructing enforcement of immigration law and facilitating illegal immigration by awarding driver's licenses, other identification, and some public benefits to lawbreakers.

In politics nationally and in Connecticut, the desire for open borders now trumps public health.

What should be done about the Haitians and Haiti? Any solution starts with recognizing the country's history.

It is widely understood that Haiti long has been a disaster, recently because of earthquakes and hurricanes but, more profoundly, because of centuries -- of political instability and imperialism, first the imperialism of France, then Germany, and then the United States. From 1915 to 1934 the United States occupied and ran Haiti as brutally as any other imperial power might have done. Since the Marines departed, Haiti seldom has been capable of more than military coups, assassinations and dictatorships.

In recent years the placement in Haiti of a United Nations peacekeeping force also has failed to achieve political stability. The country is desperately poor, uneducated, malnourished, denuded, covered in earthquake rubble, gang- and crime-ridden, and, where there is ordinary politics, corrupt.

So it's no wonder that so many Haitians try to get out. But 11 million people remain there. Even sanctuary-crazed New Haven wouldn't welcome them all, and no other country wants to take in many more destitute people.

The most obvious solution might be a comprehensive intervention under the United Nations with a much larger force of soldiers and technicians and a 30-year charter to remake the country from scratch and brook no interference, though local advisory councils might be organized. This might be brutal sometimes but less brutal than the present. With a country as small as Haiti, couldn't a determined effort by the Developed World maintain public safety; build medical, educational, electrical, water, sanitation and judicial systems; facilitate agriculture; prevent starvation, and nurture self-sufficiency?

But since the record of intervention in Haiti is so miserable and the commitment of the Developed World so unreliable, maybe something new should be tried with Haiti -- that is, leaving the country alone with its misery, forcing Haitians to deal with it themselves and with whatever help international aid groups want to provide on the slim chance of making a difference.

While the latter option may sound horrible, the Developed World is tolerating many human disasters as bad as Haiti's or nearly so: China's persecution and genocide of the Uyghur people in the northwest of the country, the Myanmar military junta's persecution and genocide of the Rohingya Muslims and its murderous suppression of advocates of democracy; the civil wars in Yemen and Ethiopia, and, of course, the oppression being imposed on Afghanistan by the new Taliban regime.

The catastrophic and humiliating failure of 20 years of "nation building" by the United States in Afghanistan argues strongly for leaving all these disasters alone, at least until they break the firewalls of national borders.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

'Histories held captive'

“Intersection” (oil on canvas), by Jeff Bye, in his show “Shenandoah,’’ at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt., through Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“In Vermont we have landscape painters who seek to capture and honor the natural beauty of our state. Bye has a similar focus, but his landscapes are the interior landscapes of buildings that once were inhabited and were vital to the towns and communities in which they stood but now are vacant, their histories held captive behind locked doors and boarded windows.’’

Mass. company Sunovion's new Parkinson’s medication

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, based in Marlboro (or Marlborough), Mass., has signed a deal with the Portuguese company Bial, granting it exclusive commercial license rights to Sunovion’s ‘Kynmobi’ Parkinson’s drug. The agreement allows Bial to handle the marketing applications and authorization procedures necessary for distribution and commercialization in Europe.

{Marlboro is a former industrial city that has become a high-tech center.}

“Sunovion will retain exclusive commercial rights to Kynmobi in North America and all other regions of the world excluding the European Union, the European Economic Area, and United Kingdom. An undisclosed amount in payment will be made to Sunovion for its supply of Kynmobi, and Bial hopes to submit a European marketing authorization application by the end of 2021. This deal comes at an important time, as more than 10 million people worldwide are predicted to be living with Parkinson’s disease by 2030.

“According to Sunovion’s press release, “Kynmobi is the first and only sub-lingual (under the tongue) therapy available for the on-demand treatment of [Parkinson’s] episodes in the U.S. and Canada.”

October: 'lavish'? 'scornful'?

The month of carnival of all the year,

When Nature lets the wild earth go its way,

And spend whole seasons on a single day.

The spring-time holds her white and purple dear;

October, lavish, flaunts them far and near;

The summer charily her reds doth lay

Like jewels on her costliest array;

October, scornful, burns them on a bier.

The winter hoards his pearls of frost in sign

Of kingdom: whiter pearls than winter knew,

Oar empress wore, in Egypt's ancient line,

October, feasting 'neath her dome of blue,

Drinks at a single draught, slow filtered through

Sunshiny air, as in a tingling wine!

— “October,’’ by Helen Hunt Jackson (1830-1885), American writer, born in Amherst, Mass., who lived much of her life Out West

Llewellyn King: Wind drought, gas shortages suggest worrisome winter coming for Europe

British wind farm rated capacity by region

(installed 2015 and 2020, projected by 2025)

WEST WARWICK

If you are thinking of going to Europe this winter, you might want to pack your long undies. A sweater or two as well.

Europe is facing its largest energy crisis in decades. Some countries will simply have no gas for heating and electricity production. Others won’t be able to pay for the gas which is available because prices are so high -- five times what they were. Much of this because Russia has severely curtailed the flow of gas into Europe, following on a wind drought.

Things are especially bad in Britain, which has been hit with a trifecta of woes. It started with a huge wind drought in and around the North Sea, normally one of the windiest places on earth. For the best part of six weeks, there simply wasn’t enough wind, and Britain is heavily invested in wind. Also, it has never installed much gas storage, which is one way of hedging against interruption.

Britain took to decarbonization with passion, confident of its great wind resource in the North Sea, where the wind is measured in degrees of gale force by the Met Office. The notoriously rough sea off Scotland hasn’t been getting its usual blow. Most European countries are 10-percent dependent on wind, but Britain relies on it for 20 percent of its power.

One result has been to propel gas prices into the stratosphere; consequently, the price of electricity has soared. Of 70 British electricity retailers, 30 have failed and others are expected to shut up shop as well. These aren’t generators but buyers and sellers of power, under a system which had been encouraged by the government when it broke up the state-owned Central Electricity Board during the Thatcher administration.

Britain, which opened the world’s first nuclear power station at Calder Hall in 1956, has been indecisive about new nuclear plants. Those now under construction are being built by Areva, a French company, which is partnering with the Chinese. This has raised questions about Chinese plans for a larger future role in British nuclear at a time when relations have soured with Beijing over Hong Kong and Chinese criticism of Britain’s right to send warships to the South China Sea, which it did in September.

One way or another, the input of electricity from nuclear in Britain has fallen from 26 percent at its peak to 20 percent today.

The biggest contribution to Britain’s problems, and to those of continental Europe, come from Russia limiting the amount of gas flowing into Europe. The supply is down 30 percent this year, and Russia looks set to starve Europe further if this is a cold winter as forecast.

Russia is in open dispute with Ukraine, which depends on Russia’s giant gas company, Gazprom, to supply gas for the Ukraine distribution system to other parts of Europe. At the heart of the Russian gas squeeze is the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which has been completed but isn’t operating yet. It takes gas directly – 750 miles -- to Germany under the Baltic Sea and parallels an older line. Its effect will be to cripple Ukraine as a distributor.

The United States opposed the pipeline, but President Joe Biden reversed that in May. Ukraine feels betrayed, and much of Europe is uneasy.

Going forward, Europe will be more cautious of Russian supplies and less confident that the wind will always blow. Its Russian gas shortage has put pressure on international liquified natural gas markets, and counties are hurting from China to Brazil.

Britain has a separate crisis when it comes to gasoline, called petrol in the United Kingdom: There is an acute shortage of tanker drivers to get the fuel, which is plentiful, from Britain’s refineries to the pumps. British service stations are out of fuel or facing long lines of unhappy motorists.

This problem goes back to Brexit. Driving tankers is a hard, poorly paid job -- as is much road haulage -- and Britons have stopped doing it. The average age of British drivers is 56 and many are retiring.

The slack was taken up by eastern Europeans when Britain was part of the European Union. But after Brexit, these drivers were sent home as they no longer had the right to work in Britain.

So, the electricity and gas shortages are compounded by a gasoline shortage, which is quite a separate issue but adds to Britain’s woes as a winter of discontent looms.

Llewellyn King, a veteran columnist and international energy expert, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.