‘Every stone is a skull’

Oak Grove Cemetery, Bath, Maine.

— Photo by Seasider53

“Here, in Maine, every stone is a skull and you live close to your own death. Where, you ask yourself, where indeed will I be buried? That is the power of those old villages: to remind you of stasis.’’

— Elizabeth Hardwick (1916-2007) in The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick. She spent much time in Castine, Maine, during summers, especially during her marriage to poet Robert Lowell.

‘Enlarging loneliness’

“Summer’,’ by Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1573

Further in Summer than the Birds

Pathetic from the Grass

A minor Nation celebrates

Its unobtrusive Mass.

No Ordinance be seen

So gradual the Grace

A pensive Custom it becomes

Enlarging Loneliness.

Antiquest felt at Noon

When August burning low

Arise this spectral Canticle

Repose to typify

Remit as yet no Grace

No Furrow on the Glow

Yet a Druidic Difference

Enhances Nature now

— Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), of Amherst, Mass.

‘Even in Massachusetts’

“The Dance Class,’’ by Edgar Degas, 1874

“The average parent may, for example, plant an artist or fertilize a ballet dancer and end up with a certified public accountant. We cannot train children along chicken wire to make them grow in the right direction. Tying them to stakes is frowned up, even in Massachusetts.’’

— Ellen Goodman (born in 1941), Boston Globe columnist.

'Balance in disorder'

“Ever Radiate the Truth Ever” (mixed media), by McKay Otto, in the show “Unconscious Equilibrium,’’ at Atelier Newport (R.I.), Aug. 10-Sept. 12.

The gallery says:

“This featured group of artists finds balance in disorder, influences in opposing forces, harmony in mundane daily tasks, and transcendent practices during chaos. In quiet solitude, these artists gain balance during a time when our world would suggest otherwise.

“Upon further reflection on meditation, and transcendence, the work on view finds a harmony through tessellations, a regular pattern made up of flat shapes repeated and joined together without any gaps or overlaps. These shapes do not all need to be the same, but the pattern should repeat. This work attempts to reflect these rhythmic, natural developing and reoccurring patterns in nature, reflected in tidal and gravitational forces, and how we as humans, react to with these powerful shifts - seasons, moons, tides —and our delicate balance.’’

Chris Powell: Bathos in Bridgeport

“Iranistan,’’ Bridgeport boy and circus impresario P.T. Barnum’s grandiose structure in the city survived only a decade before being destroyed by fire in 1857.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut's top elected officials quickly accommodated themselves to the disgrace of Joe Ganim's return to the mayoralty in Bridgeport in 2015 despite his having served eight years in prison upon conviction in federal court for vast corruption in office.

After all, just a year after Ganim was sent away in 2003, Gov. John G. Rowland resigned and pleaded guilty to federal corruption charges as well. Rowland was a Republican and Ganim a Democrat, so together they more or less normalized and bipartisanized betrayal of public office.

Of course, no one in state government could have refused to deal with Ganim in his return as mayor without also disenfranchising all of Bridgeport, Connecticut's largest and most troubled city. But looking away from corruption and failure in Bridgeport, as state government long has been doing, has become a betrayal in itself.

The city's newspaper, the Connecticut Post, notes that federal prosecutors have charged five Bridgeport officials with corruption in the last 10 months. The city's former police chief, Armando Perez, and personnel director, David Dunn, close associates of Mayor Ganim, pleaded guilty to the rigging of the chief's test for promotion. They are in prison. State Sen. Dennis Bradley and Board of Education member Jessica Martinez are charged with campaign-finance fraud. City Councilors Michael DeFilippo is charged with absentee-ballot fraud and has resigned.

The problem in Bridgeport isn't something in the city's water supply. (More than water, Ganim drank expensive wine extorted from city contractors, among other “gifts.”) More likely the problem arises from a lack of political competition in the overwhelmingly Democratic city, the ease of fooling impoverished and disengaged constituents, the corner-cutting hunger for government employment that grows amid poverty -- and the indifference of the governor, state legislators, prosecutors and civic leaders.

For it is hard to find anyone in authority who has spoken out about corruption and failure in Bridgeport, even as there is speculation that federal prosecutors are pursuing more corruption.

The cheating on the police chief test was done to secure the job for Perez, the mayor's crony, and while it may be hard to prove that Ganim directed or knew of the cheating, it is hard to believe that he had no hint about it.

The election fraud charges pending against the other three Bridgeport officials can't be tied to the mayor, but violating election law has become a tradition in Bridgeport.

The attitude at the state Capitol seems to be to keep throwing money at Bridgeport and Connecticut's other troubled cities without ever auditing them for results. This causes unaccountability and colossal waste. No one in authority seems bothered that fantastic amounts appropriated over many years have yet to diminish poverty and mayhem or improve school performance in Bridgeport and the other cities. Contenting the government class that presides over chronic failure seems to be enough.

Has anyone in authority in state government ever contemplated what Bridgeport's restoration of Ganim said about the city -- its demoralization and desperation?

But now with so many corruption charges being brought in Bridgeport in such a short time, someone in authority in state government should be asking why only federal prosecutors investigate such offenses. Have the state police and state prosecutors been given confidential instructions or advice to avoid looking into corruption in state and municipal government? Or are they just afraid or incompetent?

For its own sake as well as the state's, Bridgeport should be under perpetual investigation by a special team of state auditors. But is such investigation impossible under a Democratic state administration because Bridgeport sends the largest delegation to Democratic state conventions and produces enormous pluralities for the party?

If that's why corruption and failure in Bridgeport draw no concern from state government, Democrats are the party of corruption in Connecticut.

After all, Republicans have no power in the state, and while denouncing Donald Trump makes Democrats feel good about themselves, Trump isn't president anymore and bashing him won't clean up Bridgeport or correct any expensive policy failures.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

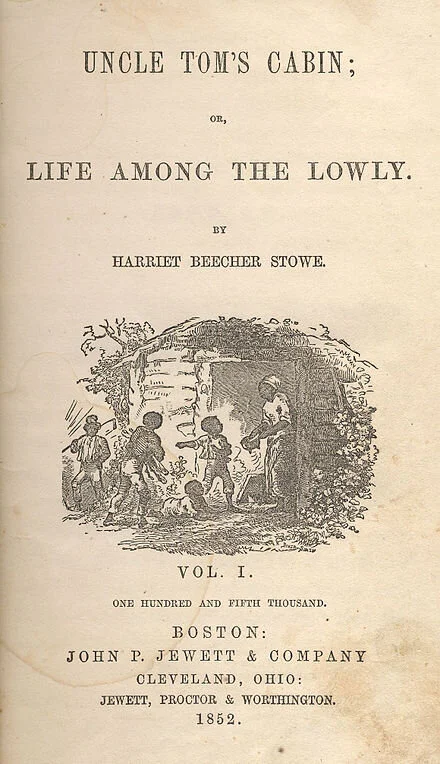

‘Abused by a race of fiends’

“In the end, Harriet Beecher Stowe looked at the phenomenon of slavery through the clean moral categories of the Yankee reformer, and what she saw was a race of children being abused by a race of fiends.’’

— Andrew DelBanco, in Required Reading (1997). Stowe, the writer and abolitionist who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was born in Litchfield, Conn. (now a rich exurb and weekend place of New York City), and died in Hartford, where Mark Twain was a neighbor. He wrote of her in her later years:

“Her mind had decayed, and she was a pathetic figure. She wandered about all the day long in the care of a muscular Irish woman. Among the colonists of our neighborhood the doors always stood open in pleasant weather. Mrs. Stowe entered them at her own free will, and as she was always softly slippered and generally full of animal spirits, she was able to deal in surprises, and she liked to do it. She would slip up behind a person who was deep in dreams and musings and fetch a war whoop that would jump that person out of his clothes. And she had other moods. Sometimes we would hear gentle music in the drawing-room and would find her there at the piano singing ancient and melancholy songs with infinitely touching effect.’’

Commercial blocks on West Street in Litchfield, Conn.

—Photo by Joe Mabel

Hot colors, cold water

“Lake Sky” (oil on canvas), by Kate Graham Heyd, in Galatea Fine Art’s (Boston) August show, “New England Collective XI.’’ She lives in Hopkinton, Mass., which is most famous as the starting point of the Boston Marathon and of the Charles River.

Llewellyn King: Resilience is the key word now as utilities face increasing stresses

Regional transmission organizations in the continental U.S.

— Graphic by BlckAssn

WEST WARWICK

We all know that sinking feeling when the lights flicker and go out. If bad weather has been forecast, the utility has probably sent you advance warning that there could be outages. You should have a flashlight or two handy, fuel the car, charge your cell phone and other electronic devices, take a shower, and fill all the containers you can with water. If it is winter, put extra blankets on beds and pray that the power stays on.

Disaster struck mid-February in Texas. Uri, a freak and deadly winter storm, froze the state’s power grid. It lasted an unusually long time: five terrible days.

There was chaos in Texas, including more than 150 deaths. The suffering was severe. Paula Gold-Williams, president and CEO of San Antonio-based CPS Energy, told a recent United States Energy Association (USEA) press briefing on resilience that the deep freeze was an equal opportunity disabler: Every generating source was affected. “There were no villains,” she said.

Uri wasn’t just a Texas tragedy, but also a sharp warning to the electric utility industry across the country to look to their preparedness, and to take steps to mitigate damage from cyberattacks and aberrant, extreme weather.

This is known as resilience. It is the North Star of gas and electric utility companies. They all have resilience as their goal.

But it is an elusive one, hard to quantify and one that is, by its nature, always a moving target.

This industry-wide struggle to improve resilience comes at a time when three forces are colliding, all of them impacting the electric utilities: more extreme weather; sophisticated, malicious cyberattacks; and new demands for electricity.

On the latter rests the future of smart cities, electrified transportation, autonomous vehicles, delivery drones, and even electric air taxis. The coming automation of everything -- from robotic hospital beds to data mining -- assumes a steady and uninterrupted supply of electricity.

The modern world is electric and modern cataclysm is electric failure.

Richard Mroz, a past president of the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, who had to deal with the havoc of Superstorm Sandy in 2012, said at the USEA press briefing, “All our expectations about our critical infrastructure, particularly our electric grid, have increased over time. We expect much more of it.”

Gold-Williams said extreme cold and extreme heat, as in Texas this year, put special pressures on the system. She said the future is a partnership with customers, and that they must understand that there are costs associated with upgrading the system and improving resilience. Currently, CPS Energy is implementing post-Uri changes, she said.

Joseph Fiksel, professor emeritus of systems engineering at Ohio State University, said at the USEA briefing that the U.S. electric system “performs at an extraordinary level of capacity” compared to other parts of the world. He said utilities must rethink how they design their systems to recognize the huge number of calamities around the world that have affected the industry.

A keen observer of the electric utility world, Morgan O’Brien, executive chairman of Anterix, a company that is helping utilities move to private broadband networks, believes communications are the vital link. He told me, “Resilience for utilities is the time in which and the means by which service is restored after ‘bad things’ happen, be they weather events of malicious meddling. Low-cost and ubiquitous sensors connected by wireless broadband technologies, are the instruments of resiliency for the modern grid. No network is so robust that failure is impossible, but a network enabled by broadband conductivity uses technology to measure the occurrence of damage and to speed the restoration of service.”

Neighborhood microgrids, fast and durable communications, diversity of generation, undergrounding critical lines, storage and cyber alertness are part of the resilience-seeking future.

As more is asked of electricity, resilience becomes a byword for keeping the fabric of the modern world intact. Or at least repairing it fast when it tears.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington,D.C.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Thanks!

Got it.

Done.

ReplyReply allForward

‘What we most fear’

Photo by Ugglewug

“Livid to lurid switched the sky.

From west, from sunset, now the great dome

Arched eastward to lip the horizon edge,

There far, blank, pale….

What most we fear advances on

Tiptoe, breath aromatic. It smiles….’’

— From “Sky,’’ by Robert Penn Warren (1905-1909), American poet, novelist and essayist. A native of Kentucky, he spent much of his adult in Fairfield, Conn., and Stratton, Vt., where he died and is buried.

The Stratton Meetinghouse

Downward slope

Katydid, aka bush cricket

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Even with all the rain we’ve had, a few leaves on the plane trees are browning and falling off, and the weeds and ivy are growing a tad more slowly these days. Seeds are gaining prominence over flowers. And yet the woods and suburban roadsides still resemble very green jungle so thick that it seems hard to believe that autumn freezes will wither it into a dead brown.

In the evening we’re hearing the first choruses of katydids, especially loud at the end of hot days, and there’s the slight dimming of the afternoon light compared to a week or two ago. Soon will come the back-to-school ads. And friends in Vermont have been touting the fall foliage in the Taconic Range.

Children in Chicago surround an ice cream vendor in 1909.

Summer is the time of good goo: Ice-cream cones drip onto your chin; hot-dog mustard turns your face and hands an unsightly yellow; corn-on-the-cob butter slicks up the table; popsicles melt onto your sticky hands as you try to finish them before they turn completely into liquid. And that fading favorite of kids at summer county fairs and amusement parks -- cotton candy, instant diabetes!

Messy but happy experiences.

Frank Carini: Warming waters are changing fish mix

From ecoRI.org

For generations, winter flounder was one of the most important fish in Rhode Island waters. Longtime recreational fisherman Rich Hittinger recalled taking his kids fishing in the 1980s, dropping anchor, letting their lines sink to the bottom, waiting about half an hour and then filling their fishing cooler with the oval-shaped, right-eyed flatfish.

Now, four decades later, once-abundant winter flounder is difficult to find. The harvesting or possession of the fish is prohibited in much of Narragansett Bay and in Point Judith and Potter ponds. Anglers must return the ones they accidentally catch to the sea.

Overfishing is easily blamed, and the industry certainly bears responsibility, as does consumer demand. But winter flounder’s local extinction isn’t simply the result of overfishing. Sure, it played a factor, but the reasons are complicated, from habitat loss, pollution and energy production — i.e., the former Brayton Point Power Station, in Somerset, Mass., pre-cooling towers, when the since-shuttered facility took in about a billion gallons of water daily from Mount Hope Bay and discharged it at more than 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

The climate crisis, however, is likely playing the biggest role, at least at the moment, by shifting currents, creating less oxygenated waters and warming southern New England’s coastal waters. These impacts, which started decades ago, have and are transforming life in the Ocean State’s marine waters. The changes also impact ecosystem functioning and services. There’s no end in sight, as the type of fish and their abundance will continue to turn over as waters warm.

Rhode Island’s warming water temperatures are causing a biomass metamorphosis that is transforming the state’s commercial and recreational fishing industries, for both better and worse. The average water temperature in Narragansett Bay has increased by about 4 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1960s, according to data kept by the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

Locally, iconic species are disappearing (winter flounder, cod and lobsters), southerly species are appearing more frequently (spot and ocean sunfish) and more unwanted guests are arriving (jellyfish that have an appetite for fish larvae and, in the summer, lionfish, a venomous and fast-reproducing fish with a voracious appetite).

Dave Monti, a charter boat captain for the past two decades, has been fishing in Rhode Island and Massachusetts waters for 45 years. He’s seen a lot of change in a fairly limited amount of time.

He said the type of fish in Rhode Island’s marine waters today is much different than a decade ago. He pointed to the impact of a changing climate. Warm-water fish such as black sea bass, summer flounder and scup are here in abundance, according to Monti. These species are now an integral part of his charter business.

“It would have been unheard of 10 years ago to say black sea bass would be so abundant in our waters, and that it would be a big part of my charter business,” Monti said.

This transfer of fish along the Atlantic Coast is having an impact on commercial fisheries, most notably regarding the issue of assigning stock allocations.

For example, Monti noted that summer flounder moving north has created havoc with catch limits. He said Mid-Atlantic vessels, which possess the summer flounder quotas but now have fewer of the fish in their waters, have moved up the East Coast to fish. New England boats now have the fish in their waters but little allocation.

He said that the laws that govern commercial fishing need to keep up with the impacts of the climate crisis. He also noted that as warming waters change the type and abundance of fish in different regions, commercial fishermen have to retool their boats and gear and learn how to catch the species new to their waters.

Hittinger, first vice president of the Rhode Island Saltwater Anglers Association, attributes the species changes he has witnessed in local waters, at least in part, to rising water temperatures.

When the Warwick resident started fishing regularly more than four decades ago, Hittinger said he caught cod and pollack off Block Island and winter flounder in all of the state’s bays. He noted that most of these fish are largely gone, replaced by warm-water species.

Speaking as a recreational angler, Hittinger said the changing of the species found in Rhode Island’s salt waters isn’t necessarily his concern. His concern lies with regulation that is slow to change with the times. He used black sea bass as an example, noting that Rhode Island’s recreational fishing restrictions on the species, implemented by the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, were set 20 years ago. Now, he said, there are a lot more of them.

Black sea bass caught in Rhode Island waters must be at least 15 inches in length and the limit is three or seven per angler per day depending on the season. Hittinger noted that in New Jersey, where the fish is becoming slightly less plentiful, keepers must be at least 12.5-13 inches and the daily allowance is higher.

As the waters off the East Coast continue to warm, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council and the New England Fishery Management Council will likely be hearing similar concerns.

Stephen Hale, a long-time marine ecologist at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Atlantic Coastal Environmental Sciences Division Laboratory in Narragansett, said marine animals are shifting northward along the Atlantic Coast in response to the changing climate. He said the movement of a new species into an area can cause ecosystem disruption and that the depletion of key species from an area can lead to economic and social changes.

Hale noted that if your preferred habitat was warming to a level you found intolerable, you would basically have three choices: adapt (install an air conditioner, for example); move to a cooler locale (say Maine); or stay where you are and suffer the consequences (heat exhaustion, heat stroke, death).

He said many of the planet’s other species can only exercise the second option, while others are stuck with the third.

Along the East Coast numerous marine species, including bottom-dwelling invertebrates such as clams, snails, crustaceans and polychaete worms, have shifted their ranges poleward in response to rising water temperatures caused by the global climate crisis. Cold-water species such as cod, winter flounder and American lobster are moving to cooler locales.

Hale said species are trying to maintain their preferred thermal niche by moving poleward or into deeper water.

The Saunderstown resident, who retired from the EPA in 2018 after 23 years at the Narragansett lab, co-authored a 2017 study that covered two biogeographic provinces along the Atlantic Coast: Virginian, Cape Hatteras, N.C., to Cape Cod; and Carolinian, mid-Florida to Cape Hatteras.

The authors found that bottom water temperature increased 2.9 degrees Fahrenheit from 1990 to 2010. They also noted that the center of distribution of 22 out of 30 species studied shifted north in response to increasing water temperatures. Seven species shifted south, but moved just one-third the distance of the northward-movers.

“Fishermen are adaptive,” said Monti, a strong supporter of renewable energy development to address the climate crisis. “Every day is different with tides, currents, wind and bait. Warming waters and climate change are just additional factors. Regions are losing and gaining fish. It’s not going to end.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI.org.

At least someone loves him

‘Narcissus,’’ by Robert Henry, in his show “Solo Moments,’’ at the Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown, Aug. 21-Sept. 11.

Phyllis Bennis: Triumph and tragedy of the Olympic Refugee Team

The Refugee Team competes under the Olympic Flag.

Via OtherWords.org

The Olympic Refugee Team filing into the stadium during Tokyo’s opening ceremonies provided a powerful, moving sight: almost 30 athletes, carrying the Olympic flag, striding alongside the delegations of almost every country in the world.

Instead of their home countries, these refugees represent the millions around the world who’ve been forcibly displaced from their homes. The team is made up of extraordinary individuals who have overcome huge obstacles just to survive — let alone train as world-class athletes.

They are swimmers, cyclists, judoken, wrestlers, runners, and more — from Iraq and Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon, Sudan and South Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and beyond.

Several were part of the Olympics’ first Refugee Team five years ago, including Yusra Mardini, a Syrian swimmer and refugee from the country’s civil war.

Her incredible story went viral. When their overloaded dinghy broke down in the Aegean Sea, Yusra and her sister jumped overboard and swam for three hours, pushing it to safety. They saved the lives of dozens desperately trying to reach safety in Greece.

Yusra’s was only one of the stories of extraordinary trauma and triumph from Team Refugees. But unfortunately, the population represented by the team just keeps growing.

At the time of the Rio Olympics five years ago, 65 million people were forcibly displaced. This year, that figure has soared to over 82 million. If it were its own country, Refugee Nation would be the 20th most populous country on earth, right between Thailand and Germany.

There are many reasons people are forced to flee their homes — including war and violence, extreme weather and climate change, and economic injustice. The harsh reality is that mass displacement has become normalized, acceptable in today’s world.

Global warming and climate chaos are so severe that climate refugees are emerging everywhere. Wars, including many involving the United States, continue to push millions of people out of their homes. And abject poverty, skyrocketing inequality, and a global pandemic are all forcing more desperately poor people to flee in search of work, food, and safety.

It’s not enough to honor millions of refugees with an Olympic team of their own — they need rights, not medals. As long as millions remain displaced, it remains important to build broad and global movements to defend their rights.

The rights guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights include “freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State,” the right “to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution,” and the right to return to their homes when hostilities are over.

Unfortunately, from the dangerous waters of the Mediterranean to the arid U.S.-Mexico border, those rights are often denied. It’s a grim thing indeed that there are more people displaced now than at any time since World War II — so many that Refugee Nation appears to be a permanent feature of the Olympics.

Still, the courage of these extraordinary young athletes at the Olympics keeps the plight of refugees — and the responsibility of our own governments for their plight — in front of the eyes of the world.

Team Refugees’ entrance to Tokyo’s Olympic stadium provided a moment of hope and a moment of internationalism. It was beautiful.

But how much more beautiful, how much better than medals, if those athletes — and the 82 million displaced people they represent — could go home after the games? To a home for themselves and their families, in their own country or abroad, safe from the wars and disasters and poverty that drove them out in the first place?

Phyllis Bennis directs the New Internationalism Project at the Institute for Policy Studies.

State of mind Out West

“Today” (oil on panel), by Susan Strauss, in her show “Western Painting,’’ at Periphery Space @ Paper Nautilus, Providence.

The gallery says:

“Strauss describes these as pivotal paintings as they were influenced by a change of place but also a state of mind brought about by the crisis of politics and COVID. Strauss traveled to northern Arizona to paint in the winter of 2019-2020 and stayed Out West through most of 2021 so far. Starting with daily painting, direct observation and walks through the landscape, she began working on a series of abstract paintings. Book sized; the small landscapes help you travel to the high desert. The larger works connect the elemental immediacy of the Western landscape and the timelessness of Eastern cosmology represented by the mandala.’’

Strauss has lived and maintained her studio in Westport, MA since 2005 and is part of the South Coast Artists open studio community and the Art Drive. She is a founding member of the Brickbottom Artists Building in Boston and has received grants from Mass Arts Lottery and Public Works RI. Her work has been exhibited in many group and solo shows throughout the New England area including Gallery at 4, Tiverton, RI, Dedee Shattuck Gallery, Westport, MA, Gallery NAGA, Boston, MA, Newport Art Museum, Newport, RI, New Bedford Art Museum, New Bedford, MA, Tufts University, UMass Boston, Boston University, Prince Street Gallery, New York, NY and Atlantic Gallery, New York, NY.

For more information about the show visit http://www.peripheryspace.com

to learn more about artist visit her website and social media

https://www.susanstrausspainting.com

Instagram @susanstrausspainting

‘Irregular pile of architecture’

A view of Fenway Park and the surrounding neighborhood, as seen from the Prudential Tower.

— Photo by Aidan Siegel

The ballpark is the star. In the age of Tris Speaker and Babe Ruth, the era of Jimmie Foxx and Ted Williams, through the empty-seats epoch of Don Buddin and Willie Tasby and unto the decades of Carl Yastrzemski and Jim Rice, the ballpark is the star. A crazy-quilt violation of city planning principles, an irregular pile of architecture, a menace to marketing consultants, Fenway Park works. It works as a symbol of New England's pride, as a repository of evergreen hopes, as a tabernacle of lost innocence. It works as a place to watch baseball”.

Martin F. Nolan, now-retired Boston Globe reporter and editor.

Don Pesci: Connecticut could use some ‘moxie’

VERNON, Conn.

It does not take a majority to prevail... but rather an irate, tireless minority, keen on setting brushfires of freedom in the minds of men

– Sam Adams

Bob Whitcomb used to be the editorial page editor of The Providence Journal at a time when Moxie was plentiful in Connecticut. Sadly, that is no longer the case. Moxie in “The Nutmeg State” has become rarer than modest politicians. Whitcomb was my editor at The Providence Journal back in the day.

And this is one of my pet peeves – that journalism is no longer able to produce editorial-page editors such as Whitcomb, perhaps because journalism lacks “moxie.”

A piece in Whitcomb’s New England Diary tells us that Moxie is “a carbonated beverage brand that was among the first mass-produced soft drinks in the United States. It was created around 1876 by Augustin Thompson (born in Union, Maine) as a patent medicine called ‘Moxie Nerve Food’ and was produced in Lowell, Mass.”

The extravagant claims of patent medicine pushers in the post-Civil War period were, of course, patently absurd. But this was the age of P.T. Barnum and Woodrow Wilson, an early progressive and a racist who had a beef with the U.S. Constitution. The progressive beef, briefly, was that the Constitution served as a breakwater against the overweening ambitions of progressives to make the world anew from the ground up.

Ronald J. Pestritto tells us in his essay“Why the Early Progressives Rejected American Founding Principles’’ that the progressives “had in mind a variety of legislative programs aimed at regulating significant portions of the American economy and society, and at redistributing private property in the name of social justice. The Constitution, if interpreted and applied faithfully, stood in the way of this agenda.”

Progressive patent nonsense has been revived in our own time, but the post-progressive movement – pushed forward by political malcontents such as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D.-N.Y.), Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.), Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) and Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), better known as “the squad” -- lacks the intellectual rigor that Wilson brought to his make-the-world-over project. See William Graham Sumner’s in Connecticut Commentary on “the absurd effort to make the world over.”

The era that gave us Wilson also made Moxie a national beverage, a saving grace for those of us who have acquired the requisite "acquired taste."

Moxie is not a first love. She is the one that you plan to marry after your first two loves have gone their ways without you.

I used to be able to buy Moxie in one of three grocery stores within reasonable driving distance of my house.

No more.

“You used to carry Moxie,” I told the soda manager at one of the stores. “No more?”

He mumbled something.

“I can’t decipher what you’re saying.”

He was double-masked, removed both, and then said, popping every plosive, “Moxie has been bought out by Coke. If you ask me in a few weeks, I’ll see what I can do.”

But Coronavirus swept over us, weeks went by, and Moxie, along with the smiles of middle-class workers, suppressed by masks, disappeared from the shelves of all three stores.

I gave up the struggle, but the irritation chafed. It is small irritants, not large deprivations, that produce revolutions. The French Revolution began as a protest in Paris over the lack of bread. The American Revolution began as a protest over a tax on tea. In both cases, irritant had been piled on irritant until something in the human breast shouted – revolution!

Autocrats in Connecticut had better give some thought to little irritations. Most of us have been free of masks for weeks. Our restaurants have re-opened. Waitresses and waiters, the wait staff much depleted but unmasked, have shown their welcoming faces to repeat customers.

We read those faces, smile back … and now, owing to a strain of Coronavirus more contagious but less disabling among the general population, the national business shutdown-industry has been pondering new impositions: punishments for people who, whatever their reasons, have yet to be vaccinated; possible future business shutdowns; yet more extensions of anti-constitutional gubernatorial executive powers, and “More mask,” the dying last words of Friedrich Nietzsche.

It is a matter of some debate whether revolutionary brushfires lit in the hearts of men, or a lack of moxie, will be the spark that produces a revolutionary restoration of constitutional rights and immunities.

The word “moxie”, the New England Diary tells us means “daring, or determination. It was a favorite word of the ruthless Joseph P. Kennedy, father of the famous political family that included President John F. Kennedy. If he liked someone, he’d say ‘he has moxie!’’ {small “m” in that generic use}.

Or, “Moxie makes you foxy.”

Unfortunately, Connecticut has no moxie and is not foxy.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

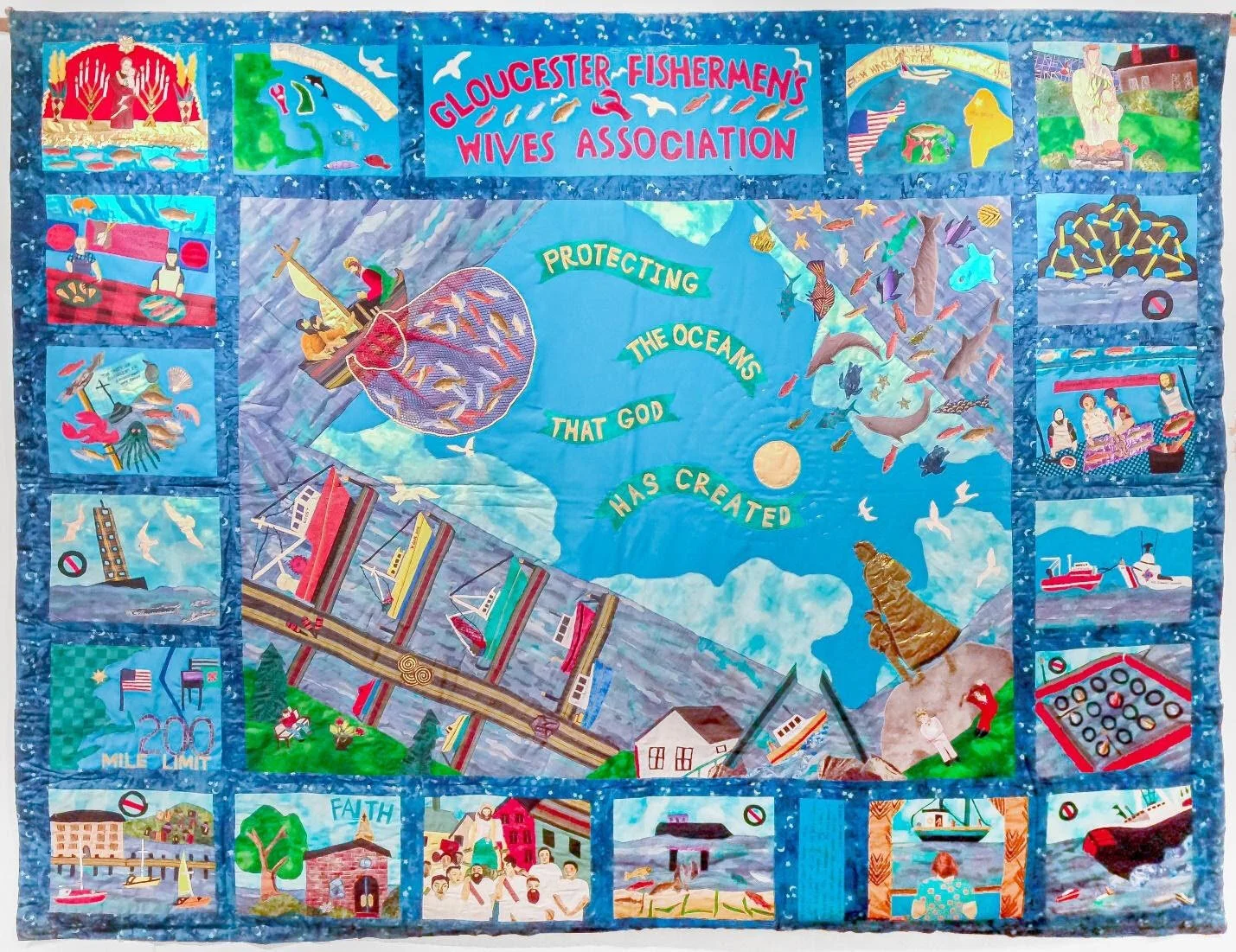

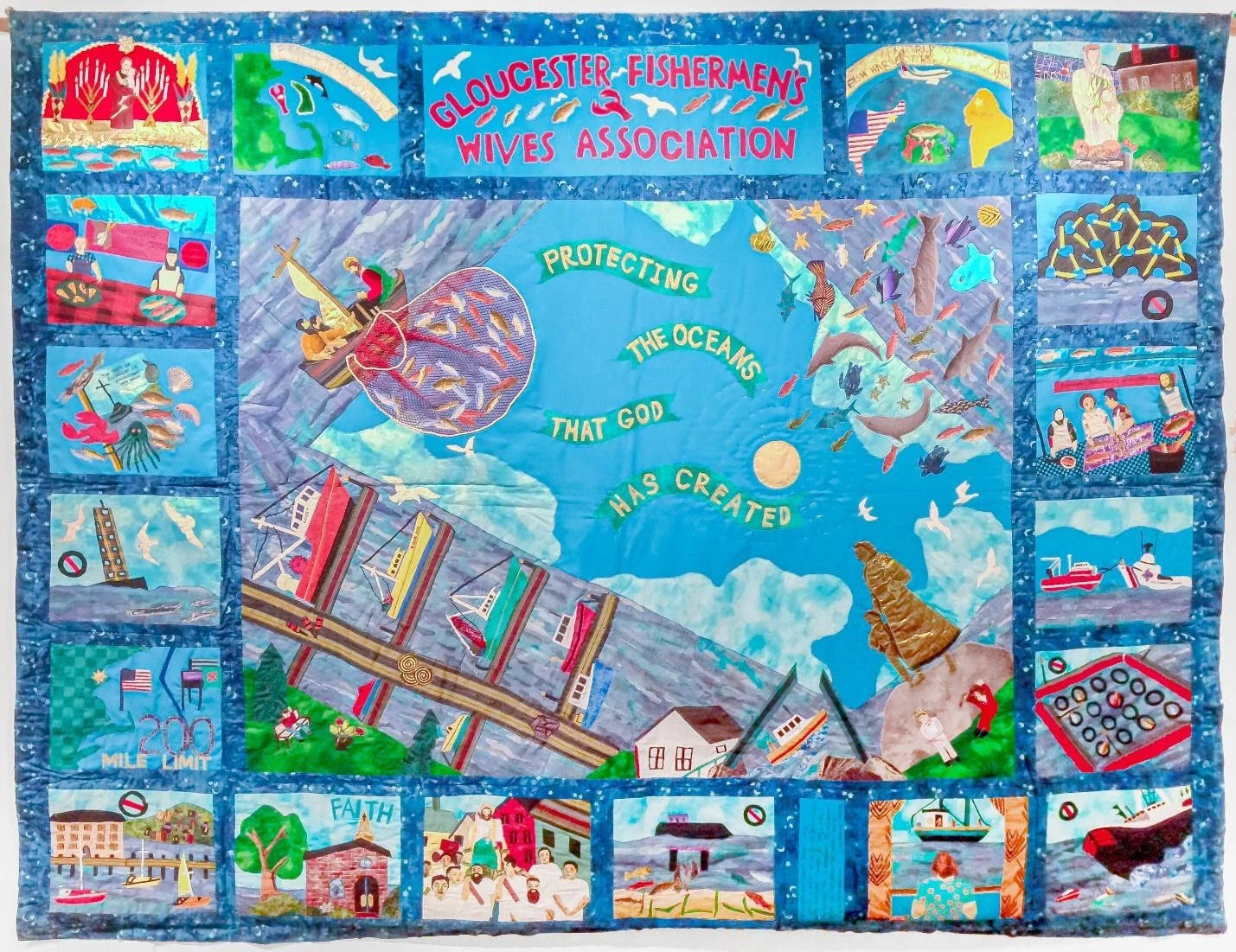

Quilting a message

“Protecting the Oceans that God Has Created’’ is a narrative quilt made by members of the Gloucester Fishermen’s Wives Association in collaboration with Clara Wainwright in 1998. It can be seen at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, through Sept. 26. It’s on loan from the Gloucester Fishermen’s Wives Association.

Wave action at Rough Point

The Rough Point mansion from Newport’s Cliff Walk.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s nice when artists and others use New England’s innumerable beautiful outdoor spaces for exhibitions.

Thus it is with artist Melissa McGill’s coming show “In the Waves’’ at Newport’s Rough Point (which we used to call Rough Trade), the estate of late and deeply eccentric, indeed creepy (but philanthropic!) billionairess Doris Duke.

Ms. McGill has put out a call for young people to participate in the show, set for next month and meant to focus attention on global warming-caused sea-level rise and other man-caused environmental issues. Dodie Kazanjian, the founder of Art & Newport, is the curator of the exhibition.

This spectacle involves Ms. McGill painting waves on fabric made out of recycled plastic pulled from the ocean; plastic pollution has become a huge menace to sea life. The young people participating in the spectacle will use handles at the ends of long fabric strips to create motion to mimic that of waves.=

“I’m painting the waves in a very expressive way, with the different colors that reference the ocean at Rough Point,” Ms. McGill told the Newport Daily News’s Sean Flynn, in a fun article. “I have done studies and research so they really evoke the ocean there.” (Does the ocean at Rough Point really look that much different than the ocean anywhere?)=

For more information, please hit this link.

xxx

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 29, 2012

xxx

As the seas rise, more and more people will have to move back from the shore and abandon their homes on land that’s increasingly vulnerable to flooding. That land will be left as a buffer to mitigate damage from storms. How much of it can be turned into public open space, as parks, bringing something good from the situation?

By the way, although it was published back in 1999, Cornelia Dean’s prescient book Against the Tide: The Battle for America’s Beaches, remains a dramatic, prescriptive (and often alarming) guide to the issues around rising seas and coastal development. Ms. Dean, the former New York Times science editor, continues to study the not-very-slow-motion coastal crisis.

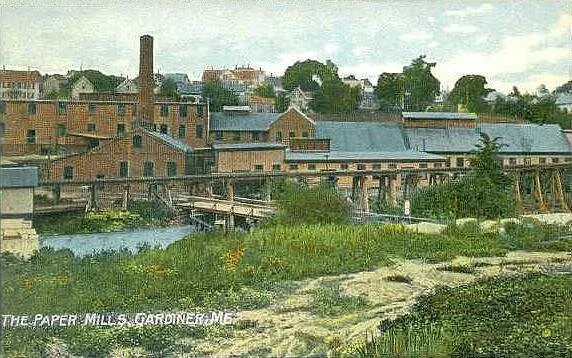

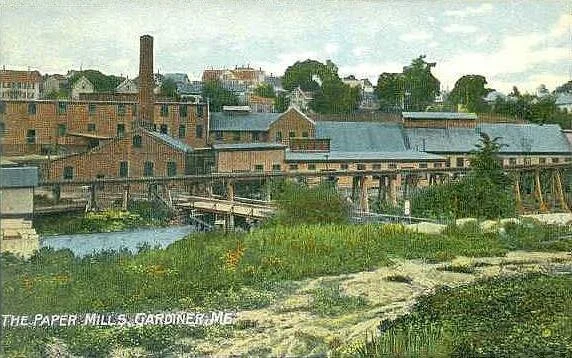

‘Scarred hopes outworn’

1909 postcard

Over the hill between the town below

And the forsaken upland hermitage

That held as much as he should ever know

On earth again of home, paused warily.

The road was his with not a native near;

And Eben, having leisure, said aloud,

For no man else in Tilbury Town to hear:

"Well, Mr. Flood, we have the harvest moon

Again, and we may not have many more;

The bird is on the wing, the poet says,

And you and I have said it here before.

Drink to the bird." He raised up to the light

The jug that he had gone so far to fill,

And answered huskily: "Well, Mr. Flood,

Since you propose it, I believe I will."

Alone, as if enduring to the end

A valiant armor of scarred hopes outworn,

He stood there in the middle of the road

Like Roland's ghost winding a silent horn.

Below him, in the town among the trees,

Where friends of other days had honored him,

A phantom salutation of the dead

Rang thinly till old Eben's eyes were dim.

Then, as a mother lays her sleeping child

Down tenderly, fearing it may awake,

He set the jug down slowly at his feet

With trembling care, knowing that most things break;

And only when assured that on firm earth

It stood, as the uncertain lives of men

Assuredly did not, he paced away,

And with his hand extended paused again:

"Well, Mr. Flood, we have not met like this

In a long time; and many a change has come

To both of us, I fear, since last it was

We had a drop together. Welcome home!"

Convivially returning with himself,

Again he raised the jug up to the light;

And with an acquiescent quaver said:

"Well, Mr. Flood, if you insist, I might.

"Only a very little, Mr. Flood—

For auld lang syne. No more, sir; that will do."

So, for the time, apparently it did,

And Eben evidently thought so too;

For soon amid the silver loneliness

Of night he lifted up his voice and sang,

Secure, with only two moons listening,

Until the whole harmonious landscape rang—

"For auld lang syne." The weary throat gave out,

The last word wavered; and the song being done,

He raised again the jug regretfully

And shook his head, and was again alone.

There was not much that was ahead of him,

And there was nothing in the town below—

Where strangers would have shut the many doors

That many friends had opened long ago.

— “Mr. Flood’s Party,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935). Tilbury Town is based on Robinson’s hometown of Gardiner, Maine.

‘She gives of her strength’

“Hold your hands out over the earth as over a flame. To all who love her, who open to her the doors of their veins, she gives of her strength, sustaining them with her own measureless tremor of dark life.’’

— Henry Beston (1888-1968), American writer and naturalist, in The Outermost House, the classic story of the time he spent living alone in a shack on Cape Cod’s Nauset Beach.