David Warsh: Monopolistic Amazon is headed for breakup

The Amazon Spheres, part of the Amazon headquarters campus in Seattle

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Public sentiment that government should write new rules for the enterprise economy, comparable to the laws of 1892 and 1914, is growing. Firms based on Internet and block chain technologies in the 21st Century are proving comparable to the railroad, electricity and internal-combustion industries that emerged in the 19th (all of them based on the invention of interchangeable parts). Successful entrepreneurs have demonstrated that rules beyond the Sherman and Clayton Acts are required.

Meanwhile, there is Amazon.

One thing we learned from the Microsoft case in 2001 was that potentially successful anti-monopoly actions are possible. What’s required is drop-dead proof that the law has been broken and a remedy easy to understand. US District Court Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson, having ruled for the Justice Department that Microsoft has had deliberately snuffed out Netscape, set out to break Microsoft into two companies, one selling operating systems, the other applications

It didn’t happen; the conservative Washington, D.C., Circuit Court threw out the case on a technicality and politics moved on. But twenty years on, politics are back. It is intuitively obvious that the world would be a better place if the remedy had been effected. The Leviathan would have been forced to compete on two fronts instead of one. .

The Microsoft case is worth remembering when it comes to thinking about what to do about Amazon.

Matt Stoller, an anti-monopoly newsletter writer, thinks that Washington. D.C. Atty. Gen. Karl Racine has identified the smoking gun and filed suit. It’s that “free delivery” promise. It works like this, says Racine: a “most-favored nation” provision written into the Amazon contract requires that vendors not sell their goods for less in other venues, thereby raising aggregate prices to Amazon levels across the board and so harming consumers in the bargain – a violation of the Sherman Act.

For those who don’t want to read the 30-page government complaint (which is itself quite lucid), Stoller describes the argument clearly. It boils down to this: as founder Jeff Bezos himself put it in 2015, “Fulfillment by Amazon is important because it is the glue that inextricably links Marketplace and Prime.” A third of all shoppers abandon their carts when they see shipping charges. Amazon wants customers to think of whatever they have ordered and the promise of free shipping as part of their $119 annual membership fee as a unified “mega-product,” Stoller writes. What Bezos likes to call a “flywheel” exists to make the decision to buy all but inevitable. Indeed, Stoller continues, “Anytime you hear the word ‘flywheel’ relating to Amazon, replace it with ‘monopoly’ and the sentence will make sense.”

It seems clear to me from the government’s complaint that an “everything store” has no business in the delivery business, though it may take a long time to prove it in court. Bezos traveled to the edge of space on July 20, but Amazon is bound for break-up. Running afoul of the Sherman Act is one thing. The problems with Facebook, Google, Apple and Microsoft (and with the banking, pharmaceutical and agricultural industries) are more complicated. They have to do with advertising and big data. These new angles may require new legislation.

With Amazon, the question is what to do next. Nationalize Prime and fold it into the U.S. Postal Service? (Remember, the original charm of the postal system was the fact that purchase of a first-class stamp would insure that the letter would be delivered anywhere in the nation.) Or perhaps force a divestiture and set Prime in competition with United Parcel Service, Federal Express, and DHL? In that case, what to do about the USPS?

For now, it’s a question for the Department of Justice, the National Association of Attorneys General, and the economists they will eventually hire to devise remedies, (It was Rebecca Henderson, of the Harvard Business School; Paul Romer, then of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business; and Carl Shapiro, of the University of California at Berkeley, who proposed the “ops and apps” remedy in the Microsoft case.)

President Biden still hasn’t nominated an assistant attorney general for Antitrust. Plenty of turmoil has been ongoing behind the scenes. For a reliable guide to the differences among the Chicago School, the Modern approach, and the Populists’ view, see “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It,” by Cal-Berkeley’s Shapiro. It seems fair to say that the whole world is watching.

. xxx

Andreu Mas-Colell, 77, is one of the most widely respected economists in the world, possessing rank as a teacher slightly different from that of a Nobel Prize-worthy researcher. He was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, then Harvard University, and his microeconomics textbook is widely used in top graduate programs around the world. President of the Econometric Society in 1993, he left Harvard in 1995 to participate in the founding of the University of Pompeu-Fabra in his native Barcelona.

Named secretary general of the European Research Council, in 2009, he resigned a year later to become cabinet minister for the economy of Catalonia, four prosperous provinces in northeast Spain whose longstanding desire for independence has been an especially divisive issue since the restoration of Spanish democracy, in the 1970s. Mas-Colell resigned his post a year before Catalonia conducted a referendum in 2017 and declared itself autonomous in a manner deemed by the Spanish government to have been illegal.

As part of proceedings against 34 former Catalan officials, Mas-Colell was recently accused of misspending funds in pursuit of Catalonia’s independence. Spain’s Court of Auditors, an administrative body that oversees public accounts, imposed penalties of as much as €2.8 million (about $3.3 million) which the accused would have to pay immediately, before they can appeal them in court. Fellow economists around the world, have rallied to Mas-Colell’s defense, kept abreast of matters by his son, Alexandre. a Princeton University economist.

A friend in Barcelona writes:

The Catalan Government is trying to use (indirectly) public funds to post bail for the defendants; the Spanish government will take a careful look to make sure the arrangement is legally correct. Meanwhile, Mas-Colell has published a well-thought-out article stating that it is improper for an administrative tribunal to employ procedures normally the province of the judiciary. I assume all will end well (not for the reputation of the Court of Auditors) Mas-Colell? All through his life he has been willing to take risks and to make sacrifices for causes he thought were good.

Correspondent Xavier Fontdegloria writes in The Wall Street Journal, “Spain’s Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is trying to defuse the long-running confrontation with Catalan nationalists by pursuing talks aimed at conciliation.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Robert Davey: Film would deconstruct what really happened to TWA Flight 800

Wreckage of TWA 800 being reconstructed at Calverton Executive Airpark, in Riverhead, New York, by the National Transportation Safety Board in May 1997

Flight path of TWA 800. The colored rectangles are areas from which wreckage was recovered.

BRIDGEPORT, Conn.

What would a documentary film about the crash of TWA Flight 800 look like? For more than six years I have been a member of a group of four journalists at a series of meetings (paused by the pandemic) to try to raise something over $1 million to make what we intend will be the definitive account of what really destroyed a 25-year-old Boeing 747-100 and killed its total of 230 passengers and crew, only 12 or so minutes after leaving Kennedy International Airport, in New York City, on an overnight flight to Paris on July 17, 1996. This year marks 25 years since the crash.

Our group is rich in experience. Three are veterans of TV news, while I owe my place on the team to my work reporting on the story for the Village Voice in the late 90s and early aughts. After three years, we were joined by physicist Tom Stalcup, whose own documentary film on the crash, TWA Flight 800, released in 2013, received favorable reviews. That film, directed by former CBS journalist Kristina Borjesson, raised questions about the official conclusion of the National Transportation Safety Board that an electrical fault produced a spark that ignited fuel vapors in the airplane’s almost empty center fuel tank. Tom was keen to join us and help make a second film that would finish the job.

Our film will show that the huge, gentle beast that was that 747, tail number N93119, was perfectly safe, with no hitherto unsuspected ignition sources lurking within its complex systems and miles of wiring.

As part of that effort I am looking forward to being able to demonstrate that the NTSB falsely insinuated that a tiny amount of liquid Jet A kerosene fuel—too little to register on the aircraft’s fuel gauges—could have evaporated inside a vast tank with a capacity of just under 13,000 gallons and then exploded with such force that the 400,000-pound aircraft disintegrated within seconds.

Government research into the flammability of hydrocarbon fuels and gases goes back to work done by the U.S. Bureau of Mines in the 1950s, and continued in the following decades with reports produced by the Navy and Air Force and Federal Aviation Administration. These reports explain that if there is too little fuel vapor per unit volume of air, the mixture will be too lean to burn, and if there is too much, it will be too rich to burn.

In our film it will be satisfying to be able to report that, for example, NTSB investigators were able to ignite a warm mixture of Jet A fuel vapor and air equivalent to what they estimated was contained within TWA 800’s center tank at about 13,700 feet, but only with a spark produced by a current far stronger than any on the 747. Even then, ignition only lasted for a brief moment. A mixture is not technically flammable unless it will burn independently of the ignition source, yet the NTSB’s tests never showed that this was possible with the vapor mixture investigators tested.

For most of its ignition experiments, the NTSB used small laboratory flasks, but the largest-scale and most spectacular of the tests that it showed the public was conducted in what it called a “quarter-scale” tank.

The safety board did not explain for reporters and family members that while its quarter-scale tank had dimensions a quarter of the size of the dimensions of TWA 800’s center fuel tank, its volume was really only one 64th the volume of a full-sized tank, about 200 gallons, although it acknowledged this size difference in a footnote of its report.

Size evidently matters when a mixture of fuel vapor and air is ignited, since some of the military research into fuel flammability established that the larger the container, the smaller the force produced when the military equivalent of Jet A vapor explodes.

The quarter-scale tests were no match for TWA 800’s center tank, which was 64 times larger. But apart from that, the NTSB used in its quarter-scale tests not Jet A vapor, but a mixture of propane and hydrogen and air, and an ignition source much more powerful than any that existed, even as a remote possibility, on any 747.

Yet investigators never demonstrated that the mixture’s explosive characteristics matched those of Jet A, at any altitude. Hydrogen, after all, is highly flammable, and propane is considered so dangerous that supermarkets bar customers from bringing even empty canisters inside the store.

On that question, I’d like to include a comment from a professor at Leeds University, in England, John Griffiths, co-author of Flame and Combustion (Blackie Academic and Professional, Third ed., 1995), who told me, after reviewing a description of the quarter-scale tests, that as the ignited mixture of propane and hydrogen and air encountered structural panels inside the tank, it became “turbulent,” a technical term meaning more rapid and violent. He said he’d be “astonished” if the ignition of a mixture of Jet A vapor and air would have developed in a comparable way.

And I would like our film to make public an incident that occurred in 1995, a little more than a year before its final flight, when N93119 was approaching Rome and was twice struck by lightning. The flight engineer told me the story, and he also showed me a photograph of the airplane after it landed safely at Rome, with its right-wing tip damaged by the lightning strikes. The tail number is clearly visible in the photo. He told me the lightning had charred wiring near the wing fuel tanks on that side. Yet no fire and explosion had happened, and the 747 had landed safely. I looked up the NTSB’s TWA 800 maintenance report, but I could not find any record of the lightning incident and the repairs to the wing, which were visible in a July 29, 1996, Time magazine cover photo of floating debris. Yet a Boeing spokesman told me that the information had been shared with the NTSB.

In a way, the 1995 incident was a bookend to another incident at Rome, in 1964, one that did not end so well, when another TWA Flight 800, a Boeing 707, struck a steamroller on the tarmac as the pilot was attempting to abort his takeoff after an engine failed. A flame traveled down the wing and into the center fuel tank, which exploded into a horrific fire. A total of 51 people were killed and another 23 injured.

The captain of the plane, Vernon William Lowell, wrote a book — Airline Safety Is a Myth — in which he blamed the disaster on the flammable fuel vapor in his almost-empty center tank—a situation uncannily similar to the NTSB’s probable cause for the 1996 TWA 800 explosion, except for the fact that the fuel in his tank was a fuel known as JP-4, a petroleum-derived mixture that was far more volatile than Jet A kerosene. He says that most airlines were already voluntarily switching to Jet A fuel, for safety’s sake, and wonders what was holding the FAA back from banning JP-4, also known as Jet B.

The NTSB, at a session on fuel flammability at its December 1997 TWA Flight 800 hearings, in Baltimore, for some reason never mentioned the earlier TWA 800, but instead focused on the case of PanAm Flight 214, a Boeing 707 that crashed in Elkton, Md., in December 1963 after lightning struck its left wing, a fuel tank containing a mixture of Jet A and Jet B exploded, and the wing fell off.

Lowell, the captain of the 1964 TWA 800, points to partially filled or empty fuel tanks as an unacceptable hazard because the fuel vapor that fills them is flammable. That’s very similar to the NTSB’s message at Baltimore.

Yet, assuming that the safety board was aware of the 1995 lightning incident, someone at Baltimore might have pointed out that N93119, fueled by Jet A kerosene, survived those two mega-voltage jolts with flying colors; but that would not have helped the NTSB’s argument that there had been no improvements in fuel-tank safety since PanAm 214, and that only now, with the TWA 800 crash, were investigators facing up to the dangerously explosive conditions in aircraft fuel tanks that threatened every passenger and crew member.

In an FAA database of fuel-tank explosions, there are none, before TWA Flight 800 (1996), in which a plane crashed because an electric spark produced by the aircraft’s own systems ignited an explosion in a fuel tank containing only Jet A kerosene.

I hope that we meet someone interested in funding our film soon.

Robert Davey is a Bridgeport-based journalist. See: www.robertdavey.com or www.seedyhack. com

His email is rj_davey@me.com

Go back where you came from

Junction signage in Newfields, N.H., as seen in 2005 (left) and 2019. It’s a beautiful small town to find yourself in, even if you’re lost. See below.

"We don't enjoy giving directions in New Hampshire. We tend to think if you don't know where you're going, you don't belong where you are."

— John Irving (born 1942), novelist who was born and raised in Exeter, N.H.

Squamscott Street in Newfields

“Newfields, New Hampshire ‘‘(1917), by Childe Hassam, at the Princeton University Art Museum

Monarch of metroland

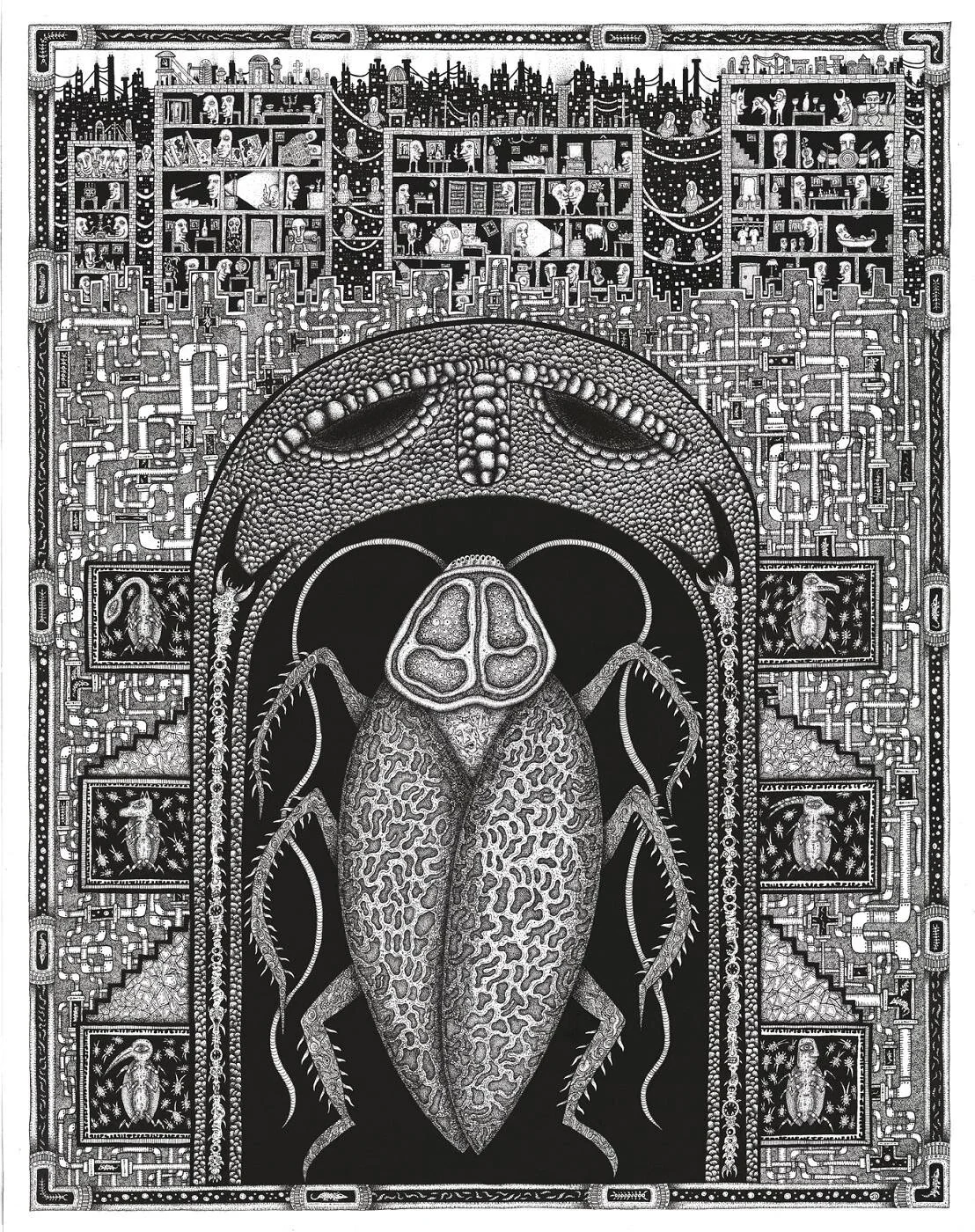

“Citadel of the Roach Queen” (dip pen and India ink), by Worcester-based James Dye, in the New England XI, a regional juried exhibition, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Aug. 6-29. Mr. Dye grew up in Holden, near Worcester.

Holden Center

Clothing, brutality and movies

In “Ruth E. Carter’s Costume Retrospective’’ at the New Bedford Art Museum: Left to Right: '‘Malcolm X costume” from the film Malcolm X (1992); “Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King costumes” from the film Selma (2014); “Mookie costume” from the film Do the Right Thing (1989); “Rudy Ray Moore costume'‘ from the film, Dolemite is My Name” (2019). Photographs by Don Wilkinson.

Don Wilkinson comments:

"From days of slavery and human bondage represented by Roots, throughout the early days of the modern Civil Rights Movement of Malcolm X and Selma and onto the culturally significant Blaxploitation era pegged by Dolemite is My Name, Carter and her crew nail it.

“And what of Do the Right Thing? It’s a 32-year-old movie that is as relevant now as it was when it was released. The critical moment in it is when Radio Raheem is choked to death by a cop’s nightstick despite the cries and pleadings of onlookers. Nightstick or knee...the story is the same.’’

Chris Powell: To end corporate welfare, cut taxes for all business

“The tax collector's office’’ (1640), by Pieter Brueghel the Younger

MANCHESTER, Conn.

At Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont's order, state government is reducing its direct subsidies to businesses coming into the state or expanding here -- cash grants, discounted or forgivable loans and tax credits. These subsidies have reeked of political patronage and corporate welfare, have sometimes cost more than they gained, have incurred financial risk to the government, and have been unfair to businesses already in the state, which get nothing for staying.

The Lamont administration's new idea is to subsidize incoming businesses by rebating to them some of the state income taxes paid by their employees. This would incur little financial risk and expense to the state.

But this system still wouldn't be fair, for unless the line of business of the new company was unique in the state, state government still would be subsidizing the new company against its in-state competitors.

Last week, the Yankee Institute offered a better and perfectly fair idea: Eliminate grants, loans and tax credits to new businesses and simply repeal Connecticut's corporation business tax.

The Yankee Institute suggests that the tax's annual revenue to state government, averaging $834 million per year, isn't so much, only about 5 percent of the state's general-receipts.

This analysis underestimates the problem, since state government never can bring itself to reduce spending at all. But to make Connecticut much more attractive to business, it would not be necessary to repeal the whole corporation business tax. Repealing even half of it would send a remarkable signal around the country.

Of course, state government is always enacting tax cuts for the future and then repealing them when the future arrives. So to be believed, a corporation business tax cut would have to offer a contract to every business in the state and every arriving business guaranteeing that its tax would not be raised for, say, 20 years. But a big differential between Connecticut's business taxes and those of other states really might pay for itself far better than spot subsidies.

xxx

OVERKILL ON YEARBOOK: Pranking high school yearbooks is a tradition almost as old as the yearbooks themselves. What would any high school yearbook be without a defaced photograph or gross caption?

But police in Glastonbury, Conn., are treating the recent yearbook pranking there as a felony, having charged the suspect, an 18-year-old student, with two counts of third-degree computer crime, each count punishable by as much as five years in prison.

That makes the offense sound like terrorism.

Meanwhile, young people with 10 or more arrests, many of them on serious charges like assault, robbery and car theft, are being released by Connecticut's juvenile court system without any punishment at all and now apparently are moving on to kill people, confident that the state lacks the self-respect to punish them for anything.

The irony here probably will turn out to be superficial, for the Glastonbury student almost surely will get similarly lenient treatment from the criminal-justice system, whose dirty little secret is that it seldom seriously punishes anyone for anything short of murder, seldom at all for a first offense.

If the offenses attributed to the student occurred before he turned 18, he may qualify for "youthful offender status," whereby a criminal case is concealed and offenders can be let off, maybe with a little social work, and no public record of their misconduct is maintained.

If the offenses occurred after he turned 18 and he is a first offender, the student can apply to the court for "accelerated rehabilitation," a probation that suspends and eventually cancels prosecution and erases the charges.

So despite his serious charges, the student won't be going to prison. But since the publicity will make the case harder to whitewash, the court might grant the student "accelerated rehabilitation" on condition of a public apology, especially since the yearbook publishing company, with spectacular generosity, has agreed to repair the yearbooks without charge.

Turnabout being fair play, the best justice here might come if the newspapers published and television stations broadcast the student's mug shot with various defacements and a gross caption to see how he likes it.

That might send him well on his way toward a career in computer hacking, politics or journalism.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Corny and then depressing

—Photo by Marek Szczepanek

“Round the point flotillas of swans come trailing

sunlit V’s and W’s, otherworldly,

But a little corny….’’

“Garbo Lobster’s fleet has been sold; Monsanto,

windows broken, whistled an absent air; New

Yorkers long since bought up the nicer houses;

God, it’s depressing….’’

--From “Neoclassical,’’ by Daniel Hall (born 1952), Amherst, Mass.-based poet

Lobstering in Portland, Maine

— Photo by Mrosen99

Llewellyn King: Has COVID launched a new age for workers?

Most workers would like to slash the time they spend commuting.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Millions of Americans appear to be echoing the words of the Johnny Paycheck song “Take This Job and Shove It.” This is a sentiment that is changing the work scene, the way we work, and the future of work.

The workers of America are shuffling the deck in a way that has never happened before. It is accentuating an acute labor shortage.

I receive lists of job openings every day and the common denominator seems to be that you must show up at a place of business. Among the big and seemingly frantic employers are FedEx, Walmart and Amazon. Warehouse workers and delivery drivers are the most sought-after employees.

To overcome the labor shortage, wages are rising and adding to the rising inflation -- although what part of that rise is labor cost isn’t clear. Other factors are pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, a tightening of food flows from California and other Western states, and the acute housing shortage. The economy is rebalancing; and so are workers, reassessing their lives and making changes.

There has been a severe shortage of skilled workers for a long time. It has been felt almost everywhere from construction to electric line workers. It is just worse now, exacerbated by immigration restrictions and workers who have joined the reshuffle.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, millions of individuals have assessed what they do and, apparently, found it wanting.

America’s workforce isn’t returning to the jobs that they held before the lockdown. Some are trying new things; others are demanding changes in the workplace. There is a demand for more remote working. The rat race is running short of willing rats.

Commuting seems to be the one big no-no. People in the major work hubs such as New York, Washington, Chicago, Boston and San Francisco have sampled the joys and the failings of working from home, and commuting has lost.

I know people who used to spend four or five hours every day getting to work and back home in all these cities. Sitting in a traffic jam is neither creative nor the best use of human life, these people are now saying.

In the movie Network, Peter Finch bellows, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” That is the new sentiment towards rigid travel and rigid work schedules. Working from home has taken people up the hill and shown them the valley, and they have liked the valley.

Other workers, particularly at the lower end of the work scale, have wondered whether they wouldn’t be happier doing something else now that they have had time to ponder. A friend of mine’s daughter who was a professional waiter in Florida now works for a printer. She has found she gets a more dependable income, better hours and that incalculable: a happier work environment.

I love small business, and I believe it to be the essential force for innovation and job creation. But it is also where petty boss-tyrants flourish. Lousy, egomaniacal employers aren't hard to find, especially in the restaurant business.

When I worked as a waiter in New York, between journalism jobs, I knew waiters who dreamed of the great restaurant where the tips are generous and, above all, the “patron is nice.” Unseen, there is a lot of cussing and pressure in any restaurant, and job security is unknown.

Enforced downtime has caused many to wonder whether they are even in the right line of work; whether the money, prestige or social recognition that may have gone with their old job was worth it.

For others, the gig economy has beckoned, where the employer has been cut out. Particularly, this is true of young people in communications and related work. Geeks are a hot item and can contract directly. But others, from landscape gardeners to plumbers, are going gig. The downside is there are no benefits, from Social Security deductions to pensions and health care. Society is lagging in recognizing this new arena of work.

Peculiarly, we aren’t at full employment. Unemployment is hovering around 5.9 percent and has gone up slightly as the summer has progressed. This raises the question of how many of the formerly employed are now in the gig economy, skewing the figures.

We are in what is, in effect, a post-war recovery. Traditionally, that is a time for social readjustment, for old bonds to be loosed, and for new energy to be released. Is it time to sack the boss?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

David Warsh: Of The Globe, John Kerry, Vietnam and my column

An advertisement for The Boston Globe from 1896.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It has taken six months, but with this edition, Economic Principals finally makes good on its previously announced intention to move to Substack publishing. What took so long? I can’t blame the pandemic. Better to say it’s complicated. (Substack is an online platform that provides publishing, payment, analytics and design infrastructure to support subscription newsletters.)

EP originated in 1983 as columns in the business section of The Boston Sunday Globe. It appeared there for 18 years, winning a Loeb award in the process. (I had won another Loeb a few years before, at Forbes.) The logic of EP was simple: It zeroed in on economics because Boston was the world capital of the discipline; it emphasized personalities because otherwise the subject was intrinsically dry (hence the punning name). A Tuesday column was soon added, dwelling more on politics, because economic and politics were essentially inseparable in my view.

The New York Times Co. bought The Globe in 1993, for $1.13 billion, took control of it in 1999 after a standstill agreement expired, and, in July 2001, installed a new editor, Martin Baron. On his second morning on the job, Baron instructed the business editor, Peter Mancusi, that EP was no longer permitted to write about politics. I didn’t understand, but tried to comply. I failed to meet expectations, and in January, Baron killed the column. It was clearly within his rights. Metro columnist Mike Barnicle had been cancelled, publisher Benjamin Taylor had been replaced, and editor Matthew Storin, privately maligned for having knuckled under too often to the Boston archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, retired. I was small potatoes, but there was something about The Globe’s culture that the NYT Co. didn’t like. I quit the paper and six weeks later moved the column online.

After experimenting with various approaches for a couple of years, I settled on a business model that resembled public radio in the United States – a relative handful of civic-minded subscribers supporting a service otherwise available for free to anyone interested. An annual $50 subscription brought an early (bulldog) edition of the weekly via email on Saturday night. Late Sunday afternoon, the column went up on the Web, where it (and its archive) have been ever since, available to all comers for free.

Only slowly did it occur to me that perhaps I had been obtuse about those “no politics” instructions. In October 1996, five years before they were given, I had raised caustic questions about the encounter for which then U.S. Sen. John Kerry (D.-Mass.) had received a Silver Star in Vietnam 25 years before. Kerry was then running for re-election, I began to suspect that history had something to do with Baron ordering me to steer clear of politics in 2001.

• ••

John Kerry had become well known in the early ‘70s as a decorated Navy war hero who had turned against the Vietnam War. I’d covered the war for two years, 1968-70, traveling widely, first as an enlisted correspondent for Pacific Stars and Stripes, then as a Saigon bureau stringer for Newsweek. I was critical of the premises the war was based on, but not as disparaging of its conduct as was Kerry. I first heard him talk in the autumn of 1970, a few months after he had unsuccessfully challenged the anti-war candidate Rev. Robert Drinan, then the dean of Boston College Law School, for the right to run against the hawkish Philip Philbin in the Democratic primary. Drinan won the nomination and the November election. He was re-elected four times.

As a Navy veteran, I was put off by what I took to be the vainglorious aspects of Kerry’s successive public statements and candidacies, especially in the spring of 1971, when in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relation Committee, he repeated accusations he had made on Meet the Press that thousands of atrocities amounting to war crimes had been committed by U.S. forces in Vietnam. The next day he joined other members of the Vietnam Veterans against the War in throwing medals (but not his own) over a fence at the Pentagon.

In 1972, he tested the waters in three different congressional districts in Massachusetts before deciding to run in one, an election that he lost. He later gained electoral successes in the Bay State, winning the lieutenant governorship on the Michael Dukakis ticket in 1982, and a U.S. Senate seat in 1984, succeeding Paul Tsongas, who had resigned for health reasons. Kerry remained in the Senate until 2013, when he resigned to become secretary of state. [Correction added]

Twenty-five years after his Senate testimony, as a columnist I more than once expressed enthusiasm for the possibility that a liberal Republican – venture capitalist Mitt Romney or Gov. Bill Weld – might defeat Kerry in the 1996 Senate election. (Weld had been a college classmate, though I had not known him.) This was hardly disinterested newspapering, but as a columnist, part of my job was to express opinions.

In the autumn of 1996, the recently re-elected Weld had challenged Kerry’s bid for a third term in the Senate, The campaign brought old memories to life. On Sunday Oct. 6, The Globe published long side-by-side profiles of the candidates, extensively reported by Charles Sennott.

The Kerry story began with an elaborate account of his experiences in Vietnam – the candidate’s first attempt. I believe, since 1971 to tell the story of his war. After Kerry boasted of his service during a debate 10 days later, I became curious about the relatively short time he had spent in Vietnam – four months. I began to research a column. Kerry’s campaign staff put me in touch with Tom Belodeau, a bow gunner on the patrol boat that Kerry had beached after a rocket was fired at it to begin the encounter for which he was recognized with a Silver Star.

Our conversation lasted half an hour. At one point, Belodeau confided, “You know, I shot that guy.” That evening I noticed that the bow gunner played no part in Kerry’s account of the encounter in a New Yorker article by James Carroll in October 1996 – an account that seemed to contradict the medal citation itself. That led me to notice the citation’s unusual language: “[A]n enemy soldier sprang from his position not 10 feet [from the boat] and fled. Without hesitation, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Kerry leaped ashore, pursued the man behind a hootch and killed him, capturing a B-40 rocket launcher with a round in the chamber.” There are now multiple accounts of what happened that day. Only one of them, the citation, is official, and even it seems to exist in several versions. What is striking is that with the reference to the hootch, the anonymous author uncharacteristically seems to take pains to imply that nobody saw what happened.

The first column (“The War Hero”) ran Tues., Oct. 24. Around that time, a fellow former Swift Boat commander, Edward (Tedd) Ladd, phoned The Globe’s Sennott to offer further details and was immediately passed on to me. Belodeau, a Massachusetts native who was living in Michigan, wanted to avoid further inquiries, I was told. I asked the campaign for an interview with Kerry. His staff promised one, but day after day, failed to deliver. Friday evening arrived and I was left with the draft of column for Sunday Oct. 27 about the citation’s unusual phrase (“Behind the Hootch”). It included a question that eventually came to be seen among friends as an inside joke aimed at other Vietnam vets (including a dear friend who sat five feet away in the newsroom): Had Kerry himself committed a war crime, at least under the terms of his own sweeping indictments of 1971, by dispatching a wounded man behind a structure where what happened couldn’t be seen?

The joke fell flat. War crime? A bad choice of words! The headline? Even worse. Due to the lack of the campaign’s promised response, the column was woolly and wholly devoid of significant new information. It certainly wasn’t the serious accusation that Kerry indignantly denied. Well before the Sunday paper appeared, Kerry’s staff apparently knew what it would say. They organized a Sunday press conference at the Boston Navy Yard, which was attended by various former crew members and the admiral who had presented his medal. There the candidate vigorously defended his conduct and attacked my coverage, especially the implicit wisecrack the second column contained. I didn’t learn about the rally until late that afternoon, when a Globe reporter called me for comment.

I was widely condemned. Fair enough: this was politics, after all, not beanbag. (Caught in the middle, Globe editor Storin played fair throughout with both the campaign and me). The election, less than three weeks away, had been refocused. Kerry won by a wider margin than he might have otherwise. (Kerry’s own version of the events of that week can be found on pp. 223-225 of his autobiography.)

• ••

Without knowing it, I had become, in effect, a charter member of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. That was the name of a political organization that surfaced in May 2004 to criticize Kerry, in television advertisements, on the Web, and in a book, Unfit for Command. What I had discovered in 1996 was little more than what everyone learned in 2004 – that some of his fellow sailors disliked Kerry intensely. In conversations with many Swift Boat vets over the year or two after the columns, I learned that many bones of contention existed. But the book about the recent history of economics I was finishing and the online edition of EP that kept me in business were far more important. I was no longer a card-carrying member of a major news organization, so after leaving The Globe I gave the slowly developing Swift Boat story a good leaving alone. I spent the first half of 2004 at the American Academy in Berlin.

Whatever his venial sins, Kerry redeemed himself thoroughly, it seems to me, by declining to contest the result of the 2004 election, after the vote went against him by a narrow margin of 118,601 votes in Ohio. He served as secretary of state for four years in the Obama administration and was named special presidential envoy for climate change, a Cabinet-level position, by President Biden,

Baron organized The Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Spotlight coverage of Catholic Church secrecy about sexual abuse by priests, and it turned into a world story and a Hollywood film. In 2013 he became editor of The Washington Post and steered a steady course as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos acquired the paper from the Graham family and Donald Trump won the presidency and then lost it. Baron retired in February. He is writing a book about those years.

But in 2003, John F. Kerry: The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best was published by PublicAffairs Books, a well-respected publishing house whose founder, Peter Osnos, had himself been a Vietnam correspondent for The Washington Post. Baron, The Globe’s editor, wrote in a preface, “We determined… that The Boston Globe should be the point of reference for anyone seeking to know John Kerry. No one should discover material about him that we hadn’t identified and vetted first.”

All three authors – Michael Kranish, Brian Mooney, Nina Easton – were skilled newspaper reporters. Their propensity to careful work appears on (nearly) every page. Mooney and Kranish I considered I knew well. But the latter, who was assigned to cover Kerry’s early years, his upbringing, and his combat in Vietnam, never spoke to me in the course of his reporting. The 1996 campaign episode in which I was involved is described in three paragraphs on page 322. The New Yorker profile by James Carroll that prompted my second column isn’t mentioned anywhere in the book; and where the Silver Star citation is quoted (page 104), the phrase that attracted my attention, “behind the hootch,” is replaced by an ellipsis. (An after-action report containing the phrase is quoted on page 102.)

Nor did Baron and I ever speak of the matter. What might he have known about it? He had been appointed night editor of The Times in 1997, last-minute assessor of news not yet fit to print; I don’t know whether he was already serving in that capacity in October 1996, when my Globe columns became part of the Senate election story. I do know he commissioned the project that became the Globe biography in December, 2001, a few weeks before terminating EP.

Kranish today is a national political investigative reporter for The Washington Post. Should I have asked him about his Globe reporting, which seems to me lacking in context? I think not. (I let him know this piece was coming; I hope that eventually we’ll talk privately someday.) But my subject here is how The Globe’s culture changed after NYT Co. acquired the paper, so I believe his incuriosity and that of his editor are facts that speak for themselves.

Baron’s claims of authority in his preface to The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best strike me as having been deliberately dishonest, a calculated attempt to forestall further scrutiny of Kerry’s time in Vietnam. In this Baron’s book failed. It is a far more careful and even-handed account than Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War (Morrow, 2004), historian Douglas Brinkley’s campaign biography. Mooney’s sections on Kerry’s years in Massachusetts politics are especially good. But as the sudden re-appearance of the Vietnam controversy in 2004 demonstrated, The Globe’s account left much on the table.

• ••

I mention these events now for two reasons. The first is that the Substack publishing platform has created a path that did not exist before to an audience – in this case several audiences – concerned with issues about which I have considerable expertise. The first EP readers were drawn from those who had followed the column in The Globe. Some have fallen away; others have joined. A reliable 300 or so annual Bulldog subscriptions have kept EP afloat.

Today, with a thousand online columns and two books behind me – Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton, 2006) and Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years (CreateSpace, 2018) – and a third book on the way, my reputation as an economic journalist is better-established.

The issues I discuss here today have to do with aspirations to disinterested reporting and open-mindedness in the newspapers I read, and, in some cases, the failure to achieve those lofty goals. I have felt deeply for 25 years about the particular matters described here; I was occasionally tempted to pipe up about them. Until now, the reward of regaining my former life as a newsman by re-entering the discussion never seemed worth the price I expected to pay.

But the success of Substack says to writers like me, “Put up or shut up.” After the challenge it posed dawned in December, I perked up, then hesitated for several months before deciding to leave my comfortable backwater for a lively and growing ecosystem. Newsletter publishing now has certain features in common with the market for national magazines that emerged in the U.S. in the second half of the 19th Century – a mezzanine tier of journalism in which authors compete for readers’ attention. In this case, subscribers participate directly in deciding what will become news.

The other reason has to do with arguments recently spelled out with clarity and subtlety by Jonathan Rauch in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth (Brookings, 2021). Rauch gets the Swift Boat controversy mostly wrong, mixing up his own understanding of it with its interpretation by Donald Trump, but he is absolutely correct about the responsibility of the truth disciplines – science, law, history and journalism – to carefully sort out even the most complicated claims and counter-claims that endlessly strike sparks in the digital media.

Without the places where professionals like experts and editors and peer reviewers organize conversations and compare propositions and assess competence and provide accountability – everywhere from scientific journals to Wikipedia pages – there is no marketplace of ideas; there are only cults warring and splintering and individuals running around making noise.

EP exists mainly to cover economics. This edition has been an uncharacteristically long (re)introduction. My interest in these long-ago matters is strongly felt, but it is a distinctly secondary concern. I expect to return to these topics occasionally, on the order of once a month, until whatever I have left to say has been said: a matter of ten or twelve columns, I imagine, such as I might have written for the Taylor family’s Globe.

As a Stripes correspondent, I knew something about the American war in Vietnam in the late Sixties. As an experienced newspaperman who had been sidelined, I was alert to issues that developed as Kerry mounted his presidential campaign. And as an economic journalist, I became interested in policy-making during the first decade of the 21st Century, especially decisions leading up to the global financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath. Comments on the weekly bulldogs are disabled. Threads on the Substack site associated with each new column are for bulldog subscriber only. As best I can tell, that page has not begun working yet. I will pay close attention and play comments there by ear.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

And then go back to bed

“Rise’’ (oil on canvas), by Alexis Serio, at Edgewater Gallery at the Falls, Middlebury, Vt.

The gallery says:

“Serio creates ethereal, abstract landscapes. Through her color choices, and layering of tones and simplified shapes the artist’s compositions become vast and dreamlike. They glow with shifting light and a sense of place. Serio’s work strives to evoke remembrance of something familiar for the viewer. Billowing skies meet rolling planes of landscape in this beautiful new series.’’

Calm down, old boy!

The north-central Pioneer Valley in South Deerfield, Mass.

— Photo by Tom Walsh

“Massachusetts! A word surrounded with an aura of hope! A state with a soul! There is gathered up into her name the brilliant program of a new world.’’

— Wallace Nutting, in Massachusetts Beautiful (1923)

Built in 1681, the Old Ship Church, in Hingham, Mass., is the oldest church in America in continuous ecclesiastical use. Massachusetts has since become one of the most irreligious states in the U.S. It was built by Puritans, then was Congregational and now is Unitarian-Universalist.

Be nice to them

The kitchen at Delmonico's Restaurant, New York City, in 1902. It was probably America’s most famous restaurant at the time.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I walk in Wayland Square, on the East Side of Providence, almost daily. It’s now dominated by a wide variety of restaurants, some of them very good. While such neighborhoods used to have more shops than restaurants, now it’s the other way around, as the Internet and other ambiguous forces take away retail business, especially clothing sales. Consider such big pharmacy chains as CVS, whose Wayland Square store, for example, sells a far wider variety of stuff (including underwear, socks and such fast food as plastic-wrapped sandwiches!) than did most drugstores a half century ago. But bring back the soda fountains!

The exit of some of the charming small shops in places like Wayland Square and Providence’s Harvard Square – Thayer Street –and their replacement by restaurants is sad, even as people are happily eating out more and more in those neighborhoods.

They like to sample food that they feel might be too complicated to prepare at home, they like being served and not having to clean up and they like the psychological ease of meeting people in a place without the complications of being a host or a guest. For one thing, it’s much easier/crisper to end an evening in a restaurant than in someone’s home.

Many people of very modest means spend a fiscally dangerous percentage of their income eating in restaurants. Indeed, it’s so pleasant and easy that many do it several times a week.

But the congenial experience requires what is often exhausting work by restaurant staffs, who must also all too often deal with arrogant, obnoxious people. It’s enlightened self-interest to be nice to restaurant workers. Don’t drive them away even as the tentative retreat of COVID-19 reopens so many understaffed restaurants to indoor service.

One-man sculpture park in Vermont

David Stromeyer and his wife, Sarah, during the installation of “Body Politic,’’ last year. For 50 years the celebrated artist has been installing his monumental steel sculptures on his 45-acre domain in Enosburg, Vt., which he named Cold Hollow Sculpture Park.

Elisabeth Rosenthal: Why we may never know if Biogen’s Alzheimer’s drug works

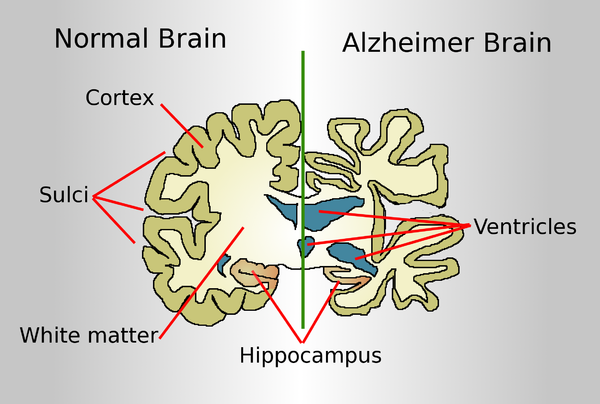

A normal brain on the left and a late-stage Alzheimer's brain on the right.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval in June of a drug purporting to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease was widely celebrated, but it also touched off alarms. There were worries in the scientific community about the drug, developed by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, mixed results in studies — the FDA’s own expert advisory panel was nearly unanimous in opposing its approval. And the annual $56,000 price tag of the infusion drug, Aduhelm, was decried for potentially adding costs in the tens of billions of dollars to Medicare and Medicaid.

But lost in this discussion is the underlying problem with using the FDA’s “accelerated” pathway to approve drugs for conditions such as Alzheimer’s, a slow, degenerative disease. Though patients will start taking it, if the past is any guide, the world may have to wait many years to find out whether Aduhelm is actually effective — and may never know for sure.

The accelerated approval process, begun in 1992, is an outgrowth of the HIV/AIDS crisis. The process was designed to approve for sale — temporarily — drugs that studies had shown might be promising but that had not yet met the agency’s gold standard of “safe and effective,” in situations where the drug offered potential benefit and where there was no other option.

Unfortunately, the process has too often amounted to a commercial end run around the agency.

The FDA explained its controversial decision to greenlight the Biogen pharmaceutical company’s latest product: Families are desperate, and there is no other Alzheimer’s treatment. Also, importantly, when drugs receive this type of fast-track approval, manufacturers are required to do further controlled studies “to verify the drug’s clinical benefit.” If those studies fail “to verify clinical benefit, the FDA may” — may — withdraw them.

But those subsequent studies have often taken years to complete, if they are finished at all. That’s in part because of the FDA’s notoriously lax follow-up and in part because drugmakers tend to drag their feet. When the drug is in use and profits are good, why would a manufacturer want to find out that a lucrative blockbuster is a failure?

Historically, so far, most of the new drugs that have received accelerated approval treat serious malignancies.

And follow-up studies are far easier to complete when the disease is cancer, not a neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s. In cancer, “no benefit” means tumor progression and death. The mental decline of Alzheimer’s often takes years and is much harder to measure. So years, possibly decades, later, Aduhelm studies might not yield a clear answer, even if Biogen manages to enroll a significant number of patients in follow-up trials.

Now that Aduhelm is shipping into the marketplace, enrollment in the required follow-up trials is likely to be difficult, if not impossible. If your loved one has Alzheimer’s, with its relentless diminution of mental function, you would want the drug treatment to start right now. How likely would you be to enroll and risk placement in a placebo group?

The FDA gave Biogen nine years for follow-up studies but acknowledged that the timeline was “conservative.”

Even when the required additional studies are performed, the FDA historically has been slow to respond to disappointing results.

In a 2015 study of 36 cancer drugs approved by the FDA, only five ultimately showed evidence of extending life. But making that determination took more than four years, and over that time the drugs had been sold, at a handsome profit, to treat countless patients. Few drugs are removed.

It took 17 years after initial approval via the accelerated process for Mylotarg, a drug to treat a form of leukemia, to be removed from the market after subsequent trials failed to show clinical benefit and suggested possible harm. (The FDA permitted the drug to be sold at a lower dose, with less toxicity.)

Avastin received fast-track approval as a breast cancer treatment in 2008, but three years later the FDA revoked the approval after studies showed the drug did more harm than good in that use. (It is still approved for other, generally less common cancers.)

In April, the FDA said it would be a better policeman of cancer drugs that had come to markets via accelerated approval. But time — as in delays — means money to drug manufacturers.

A few years ago, when I was writing a book about the business of U.S. medicine, a consultant who had worked with pharmaceutical companies on marketing drug treatments for hemophilia told me the industry referred to that serious bleeding disorder as a “high-value disease state,” since the medicines to treat it can top $1 million a year for a single patient.

Aduhelm, at $56,000 a year, is a relative bargain — but hemophilia is a rare disease, and Alzheimer’s is terrifyingly common. Drugs to combat it will be sold and taken. The crucial studies that will define their true benefit will take many years or may never be successfully completed. And from a business perspective, that doesn’t really matter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, M.D., is editor of Kaiser Health News.

Seeing the show in Boston

Brother Jonathan, in the 19th Century a visual personification of New England

To get betimes in Boston town I rose this morning early,

Here's a good place at the corner, I must stand and see the show.

Clear the way there Jonathan!

Way for the President's marshal--way for the government cannon!

Way for the Federal foot and dragoons, (and the apparitions

copiously tumbling.)

I love to look on the Stars and Stripes, I hope the fifes will play

Yankee Doodle.

How bright shine the cutlasses of the foremost troops!

Every man holds his revolver, marching stiff through Boston town.

A fog follows, antiques of the same come limping,

Some appear wooden-legged, and some appear bandaged and bloodless.

Why this is indeed a show--it has called the dead out of the earth!

The old graveyards of the hills have hurried to see!

Phantoms! phantoms countless by flank and rear!

Cock'd hats of mothy mould--crutches made of mist!

Arms in slings--old men leaning on young men's shoulders.

What troubles you Yankee phantoms? what is all this chattering of

bare gums?

Does the ague convulse your limbs? do you mistake your crutches for

firelocks and level them?

If you blind your eyes with tears you will not see the President's marshal,

If you groan such groans you might balk the government cannon.

For shame old maniacs--bring down those toss'd arms, and let your

white hair be,

Here gape your great grandsons, their wives gaze at them from the windows,

See how well dress'd, see how orderly they conduct themselves.

Worse and worse--can't you stand it? are you retreating?

Is this hour with the living too dead for you

Retreat then--pell-mell!

To your graves--back--back to the hills old limpers!

I do not think you belong here anyhow.

But there is one thing that belongs here--shall I tell you what it

is, gentlemen of Boston?

I will whisper it to the Mayor, he shall send a committee to England,

They shall get a grant from the Parliament, go with a cart to the

royal vault,

Dig out King George's coffin, unwrap him quick from the

graveclothes, box up his bones for a journey,

Find a swift Yankee clipper--here is freight for you, black-bellied clipper,

Up with your anchor--shake out your sails--steer straight toward

Boston bay.

Now call for the President's marshal again, bring out the government cannon,

Fetch home the roarers from Congress, make another procession,

guard it with foot and dragoons.

This centre-piece for them;

Look, all orderly citizens--look from the windows, women!

The committee open the box, set up the regal ribs, glue those that

will not stay,

Clap the skull on top of the ribs, and clap a crown on top of the skull.

You have got your revenge, old buster--the crown is come to its own,

and more than its own.

Stick your hands in your pockets, Jonathan--you are a made man from

this day,

You are mighty cute--and here is one of your bargains.

“A Boston Ballad’’ (1854), by Walt Whitcomb (1819-1892)

An intimate moment

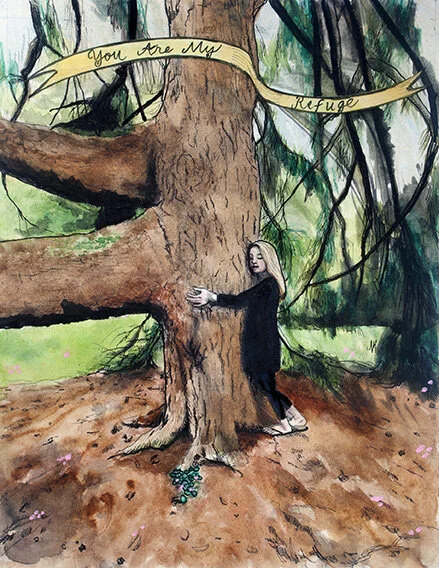

“You Are My Refuge” (watercolor, collage, ink, paper), by Pauline Lim, in the show “The Great Outdoors, ‘‘ at the Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., July 15-Aug. 14.

The gallery says:

“The past year has shown us how great ‘The Great Outdoors’ really is! The visual interest, the psychological and emotional connection, the freedom and also the safety it allowed. In this group exhibition, BAA members examine and interpret the outdoors from every angle: landscapes (natural and built), sea, sky, earth, weather... Perspective is everything; even a window box or a bird feeder are ‘the great outdoors’ to a cat sitting at a closed window.’’

Philip K. Howard: Of obsolete laws and the filibuster

Anything positive that comes out of Congress is big news, as with the recent bipartisan support for a $1 trillion infrastructure package. But that’s only half the job: Congress must also fix the delivery system that delays permitting and guarantees wasteful procurement. For example, building a resilient, interconnected power grid — probably the top environmental priority—is basically impossible in a legal labyrinth that gives any naysayer multiple ways to delay, and then to delay some more.

Congress has responsibility not only for enacting new laws, but for making sure old laws work sensibly. But Congress rarely fixes old laws. Congressional oversight consists of posturing at public hearings, not corrective legislation. Congress has effectively abdicated the oversight job to the executive branch and federal courts, which have inadequate authority to make needed legal repairs. The ship of state, weighed down by a century of statutory barnacles, plows slowly in the same direction year after year.

No statutory program works as it should. Infrastructure permitting can take a decade. Health care is a tangle of red tape, consuming upwards of 30 percent of total cost; that’s $1 million per doctor. In about half the states, teachers are outnumbered by noninstructional personnel, many focused on legal compliance. Accountability of public employees is nonexistent; 99 percent of federal employees receive a “fully successful” rating. Obsolete laws notoriously distort resources; the 1920 Jones Act, for example, makes it more expensive to build offshore wind turbines because of its requirement to use U.S.-built ships.

Washington is overdue for a spring cleaning. Only Congress has the authority to do this. But neither party has a vision about how, or even whether, to fix broken government. Congressional leaders are so dug in arguing about the goals of government that they have no line of sight to how laws actually work.

The partisan myopia is revealed by the current debate over whether to retain the Senate filibuster rule. Making it hard to enact new laws, supporters of a supermajority vote argue, encourages more deliberative new programs. Eliminating the rule, on the other hand, will allow narrow Democratic majorities to enact sweeping new progressive programs. These arguments pro and con presume that lawmaking is an additive process — that Congress’s main responsibility is to enact new programs.

Fixing old programs, however, also requires lawmaking. Should Senate rules discourage repairing existing programs? Conservative scholar F.H. Buckley argues for abolishing the supermajority entirely, even though that would mean more liberal programs in the Biden administration, because making it easier to repeal or fix broken laws would be far more impactful.

Debate over the filibuster provides an opportunity to rethink how Congress does its job. The constitutional separation of powers is designed to make it hard to enact new programs. But the Framers also knew that it was important to purge old laws. James Madison believed that “the infirmities most besetting Popular Governments…are found to be defective laws which do mischief before they can be mended, and laws passed under transient impulses, of which time & reflection call for a change.”

But the Framers did not focus on the fact that, once enacted, a program will be defended by an army of interest groups. That’s why It is more difficult to repeal or amend a law than to enact a new one. The determined defense of an obsolete program by a special interest, as economist Mancur Olson explained, will always trump the general interest of the common good. That’s why farm subsidies continue 80 years after the Great Depression ended.

All laws have unintended consequences. Circumstances change. Priorities need to be reset to meet current challenges. Agencies deviate from their congressional mandate. Clear lines of authority must be clarified to give infrastructure permits on a timely basis.

Congress must come up with a practical way to fix broken and obsolete programs. One procedural change might be for the Senate to eliminate the supermajority vote for amending or repealing laws. But the backlog of broken programs is too piled up to expect much impact from one procedural change. Congress needs to go further. Here are three changes specifically aimed at fixing broken laws:

Create nonpartisan “spring cleaning commissions” to recommend updated frameworks in each area. Then, as with base-closing commissions, the proposals would be submitted for an up-or-down vote by each chamber.

Require a sunset on all laws with budgetary impact. Over the course of a decade, Congress could then methodically update the statute books.

Revive “regular order” in Congress to provide more presumptive authority to congressional committees to fix old laws. Congress could further empower committees by automatically approving amendments that are supported by both the majority and committee ranking members.

The failure of Congress to take responsibility for the actual workings of its laws is beyond serious dispute. By delegating lawmaking to agencies, and abandoning effective oversight, Congress has severed the critical link to democratic accountability. Government keeps going in the same direction, no matter how unresponsive and ineffective. Its inability to adapt to public needs in turn spawns extremist candidates. In order to restore trust in Washington, Congress must change the rules so it can take responsibility for how laws actually work.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, author, New York civic and cultural leader and chairman of Common Good, a legal and regulatory reform organization that emphasizes the importance of taking institutional, political and personal responsibility. His Latest Book is Try Common Sense. This essay first ran in The Hill.

Frank Carini: In two areas on R.I. coast — improvement and new challenges

The Nature Conservancy and its partners installed a living shoreline at Rose Larisa Memorial Park, in East Providence, to help keep coastal erosion at bay.

— Photo by Frank Carini/ecoRI News)

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I.

Growing up in the 1970s and ’80s across the Seekonk and Providence rivers in Rhode Island’s capital, John Torgan spent plenty of time exploring the state’s urban shoreline.

He remembers them as dumps filled with sewage and littered with decaying oil tanks.

“They were horribly polluted,” said Torgan, who still lives in Providence. “No one was fishing or sailing.”

His childhood memories, however, also include the beauty of a peaceful island in the middle of a shallow 4-mile-long salt pond.

The fortunes of these waters and their surroundings have changed since an adolescent Torgan, now 51, was skipping rocks, collecting shells and investigating the coastline for marine life. The Providence and Seekonk rivers are still impaired waters, but, like the chain-link fence topped with barbed wire that once separated much of these waterways from the public, the derelict oil tanks have been removed. The rivers’ health has improved.

The two rivers, both of which share a legacy of industrial contamination and suffer from stormwater-runoff pollution, aren’t recommended for swimming, but life on, under and around them has returned. Menhaden, bluefish, river herring, eels, osprey and cormorants are now routinely spotted. The occasional seal, dolphin, bald eagle and trophy-sized striped bass visit. Kayakers, fishermen, scullers and birdwatchers are easy to find.

Torgan, who spent 18 years as Save The Bay’s baykeeper, called the comeback of upper Narragansett Bay “extraordinary” and “dramatic.” He credited the Narragansett Bay Commission’s ongoing combined sewer overflow project with making the recovery possible.

As for that summer cottage on Great Island in Point Judith Pond, he said “tremendous development” has changed the neighborhood. Bigger houses now surround the Torgan family’s saltbox cottage, adding stress to one of Rhode Island’s largest and most heavily used salt ponds.

There is a diverse mixture of development around the shores of the pond that straddles South Kingstown and Narragansett. In the urban center of Wakefield, at the head of the pond, and at the port of Galilee at its mouth, there is an abundance of commercial development and a corresponding amount of pavement. The impacts are beginning to show.

Early last year the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management decided, based on ongoing water-quality monitoring results, to reclassify two areas of Point Judith Pond from approved to conditionally approved for shellfish harvesting. Water samples collected in the pond after certain rain events showed elevated bacteria levels and resulted in several emergency and precautionary shellfishing closures.

An underappreciated coastline

As an adult, Torgan’s interest in and passion about the marine environment hasn’t waned. The avid boater and angler has spent much of his working life protecting the Ocean State’s namesake, especially the waters not typically associated with its catchy moniker.

“This is the coast,” Torgan said while standing at the water’s edge at Rose Larisa Memorial Park. “The coast of Rhode Island doesn’t start at Rocky Point. It’s not just the beaches of South County.”

But, like most of the state’s coastline, the East Providence shoreline is vulnerable to accelerated erosion driven by the climate crisis and growing development pressures. Like much of the state’s urban shoreline, the health of this stretch of beach is better but hardly pristine. It is littered with chunks of asphalt and broken glass, most of its sharp edges dulled by tumbling in the sea. Swimming isn’t advised.

The climate challenges and improved health are why the organization Torgan currently heads, the Rhode Island chapter of The Nature Conservancy, took an interest in protecting this underappreciated stretch of beach.

More frequent and intense storms, combined with increasing sea-level rise, are eroding beaches and bluffs and damaging the state’s diminishing collection of coastal wetlands. Torgan said dealing with the negative impacts of this reality, plus increased flooding, is a huge challenge for Rhode Island’s 21 coastal communities. He noted adequately supported coastal resiliency projects that use nature are needed to inoculate the state against the changes that are coming.

To that end, The Nature Conservancy partnered with the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) and the City of East Providence last year to test the effectiveness of “living shoreline” erosion controls at the popular Bullocks Point Avenue park.

The park’s steep coastal bluff rises 20-30 feet above a narrow beach. In several areas, however, erosion has crumbled sections of the bluff, exposed root balls and felled trees. Previous efforts to reduce erosion through human-made practices, such as the installation of riprap and seawalls, failed.

As its name suggests, the living shoreline model incorporated more natural infrastructure. Unlike concrete or stone seawalls, living shorelines are designed to prevent erosion while also providing wildlife habitat. Hardened shorelines, compared to living ones, also diminish public access.

The first step in returning nature to a prominent role at this coastal park, at the head of Narragansett Bay’s tidal waters, was removing debris, such as large concrete slabs more than 20 feet long that were sitting at the bottom of the bluff, left behind by those failed human attempts to keep Mother Nature at bay.

Then, at the northern end of the park, the bank was cut away to reduce the slope. Stone was placed at the base of the bluff and logs made of coconut fiber were installed farther up the slope. The bluff was planted with native coastal vegetation. Near the southern boundary, low piles of purposely placed rocks and rows of beachgrass and native plants were added.

In other areas along this stretch of upper Narragansett Bay beach, boulders, cement walls and wooden structures, to varying degrees of success, strain to keep East Providence backyards from eroding and the bay from encroaching.

“As a matter of policy, we need to change our relationship with water where we’re not trying to hold it back and keep it out,” Torgan said. “In a more comprehensive way, think about how can we manage it and create basins where we are welcoming the water. That will help with flooding. It will help with sea-level rise and storm damage. It will improve water quality. The long view is changing the mindset that says we need to wall off the rising water and instead think about natural approaches and strategies that allows us to move with it.”

He noted that while living shoreline techniques have been implemented elsewhere in the United States, few have been permitted, built and evaluated in New England. He said small-scale projects like this one give coastal engineers and coastal permitting agencies a better sense of their cost and effectiveness, most notably in areas that aren’t exposed to open-ocean shoreline, like along much of the South Coast, where these artificial marshes would likely be unable to blunt stronger wave action.

When the 2020 project was announced, CRMC board chair Jennifer Cervenka said, “Much of Rhode Island’s coastline is eroding, and it’s a problem with no easy fix. This nature-based erosion control is one of the first of its kind in Rhode Island, and New England. We can’t stop erosion completely, but living shoreline infrastructure like this might buy our shores some valuable time.”

The project, which cost about $230,000, was funded by a Coastal Resilience Fund grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, The Nature Conservancy, the Newport-based foundation 11th Hour Racing and the Rhode Island Coastal and Estuarine Habitat Restoration Trust Fund.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

But no maps to get there

“Doldrum III” (painted paper, thread and wood nails on wood panel), by Tegan Brozna Roberts, in the group show “Sense of Place’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn. opening Aug. 14.

The gallery says:

“Memory, geography and cultural experiences are underlying themes explored by these women artists. Through an innovative use of paper, maps, threads, collage and video projections, the artists create two and three dimensional objects that express universal notions of belonging and association.’

Llewellyn King: The Internet — where lies tangle with truth

“The Internet Messenger,” by Buky Schwartz, in Holon, Israel

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In this, the Information Age, truth was supposed to be the great product of the times. Spread at the speed of light, and majestically transparent, the world of irrefutable truth was supposed to be available at the click of a key.

The Internet was to be like “Guinness World Records,” conceived by Sir Hugh Beaver, managing director of the Guinness Brewery, when he missed a shot while bird hunting in Ireland in 1951. This resulted in an argument between him and his hosts about the fastest game bird in Europe, the golden plover (which he missed) or the red grouse. The idea for a reference book that would settle that sort of thing was born, which could help promote Guinness and settle barroom disputes.

The first edition was published as “The Guinness Book of Records” in 1955 and was an instant bestseller. You might have thought that there was a thirst for truth as well as beer.

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s (dominated by Republican justices) repeated rejection of any suggestion that the presidential election of 2020 was fraudulent and that it wasn’t won by Joe Biden, the Republican governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, has called a rare special session of the Texas legislature to pass a restrictive voting package that will likely include the power for the legislature to overturn any election result it deems fraudulent.

This is happening across Republican-controlled states. They are ready to fix something big that isn’t broken.

Abbott has called the special session because the Texas legislature -- thanks to the Democrats denying him quorum in a parliamentary procedure -- didn’t get what amounts to a rollback of democracy in the regular session. Second time lucky.

What these Republicans are doing is equivalent to forcing men to wear blinders so they don’t stare at naked women on our streets, even though there are no naked women on our streets. Better be sure.

Behind all this rebuttal of truth is the Big Lie. It is promoted, cherished and burnished by Donald Trump and those who swallowed his brand of fact-free ideology. The Big Lie is with us and will cast its shadow of pernicious doubt over future elections down through time. The loser will cry fraud and state lawmakers will, under the new scheme of things, be entitled to overturn election results, violating the will of the people to serve their own political goals.

Mark Twain wrote a short essay in 1880 entitled “On the Decay of the Art of Lying.” If Twain were alive today, he might be tempted to retitle his work “The Ascent of the Art of Lying.”

The extraordinary thing about the Big Lie is its blatancy; the fact that it has been found untrue by the courts and by every investigation, yet it rolls on like the Mississippi, unyielding to fact, unimpeded by truth.

The Big Lie is an avalanche of political desire over democratic fact. It introduces corrosive doubt where there is no justification. It is a virus in the body politic that may go dormant but won’t be eradicated. The host body, democracy, is weakened and the infection can flare at any time, triggered by political ambition.

Historically, there have been primary sources of information and tertiary sources of doubt or refutation. For example, some believed that the oil companies were sitting on a gasoline substitute that would convert water to fuel. That is a falsehood that has been spread since the internal combustion engine created a need for gasoline. It was believed by a few conspiracy theorists and laughed off by most people.

When the fax machine came into being in the mid-1970s there were those who thought that the Saudi Arabian regime would fall because information about liberal society was getting into the country. Instead, Saudi conservatism hardened and there was no great liberalization. Today Saudis are online and there is no uprising, no government in exile, no large expatriate community seeking change. Truth hasn’t overwhelmed belief.

It is an awful truism that people believe what they want to believe, even if that requires the suppression of logic and the overthrow of fact. Gradually all facts become suspect, and the lie fights hand to hand with the truth.

As newspaper people joke, “Don’t let the facts stand in the way of a good story.” Democracy isn’t a good story; it is the great story of human governance. And it is being subverted by lies.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.