Llewellyn King: The unfair social pressure to get a college degree

Corpus Christi College, part of the University of Cambridge

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In case you don’t know, it is, the White House has announced, Older Americans Month.

They say, in the newspaper game, “Write what you know.” I find I know about being “older.” That sounds just a bit kinder than the bald “old.”

Chalmers M. Roberts wrote a wonderful book called How Did I Get Here So Fast?: Rhetorical Questions and Available Answers from a Long and Happy Life. Quite so.

I was the youngest at everything for a long time. I didn’t go to college, so I got a head start in journalism. Leaving school at 16 wasn’t then considered a life sentence of being second-rate. In those days and that place, Southern Rhodesia (now called Zimbabwe), a college education was a rarity; and people who had one were regarded as wise, even if they were stupid, as they frequently were.

There was a different social dynamic in London, where I launched myself on the legendary Fleet Street four years later. Few had been to college and those who had were regarded in the popular press not with reverence, as they had been in Africa, but with hostility. I was even hired at the BBC.

When a very nice man, Roger Wood, became editor of The Daily Express, there was consternation. He was a university graduate and, to make matters worse, from Oxford. The end of our hallowed way of life (phony expenses claims, heavy drinking and bad food) was at hand. En masse, the denizens of the newspaper world went to the pubs to mutter darkly about the imminent collapse of civilization. Change often is greeted with the sense that civilization is over.

Years later, I told Wood about the near-insurrection his appointment to the popular London newspaper’s editorship had caused. He was surprised. The discontent had never reached the editor's office.

In my next stop, New York, I was told, “No degree, no work.” At least not in television, and not at The New York Times. All three television networks wouldn’t grant me an interview even though I had been a scriptwriter at the BBC.

Perplexingly, The New York Times told me I could be an editor, but I could never hope to write in the newspaper because of my lack of a college degree. Go figure! You can’t write here, but you can fiddle with what others have written.

Despite this gaping hole in my past, I’ve managed and even pocketed an honorary degree along the way. I’ve lectured at a trove of universities, from Harvard and MIT to the University of Southern Mississippi. While, I think, for science there is no substitute for college, for the rest I’m less convinced.

These days, a heavy burden is put on people who don’t get at least two years of a college education, and an even heavier one on those who leave high school. Here, the language is indicative of the social stigma: You don’t “leave high school,” you “drop out.” That implies at a young age, a life going south, headed for repetitive failure.

The social pressure for an orthodox education is immense. The Biden administration, in its endless good intent, may be adding to the pressure on those who, for many reasons, took a different route in their lives. The role of the universities isn’t blameless. They have a predatory streak. They are as money hungry as any corporation, shaking down the alumni and justifying it with a moral superiority.

Treating formal education as the foundation of a social class is pernicious and destructive at all levels.

I used to fly light aircraft with a brilliant pilot -- the best I have ever known. But despite skills and knowledge far above average, he was precluded from getting hired by the airlines: He didn’t finish college, instead he went off to fly airplanes.

A scientist of real ability, a friend of mine, who climbed high in Big Pharma was sidelined not because she was a woman, but because she didn’t have a doctorate, only a masters; so she became an administrator.

Governments are right to emphasize learning. However, they need to demand thoroughness and excellence in the primary and secondary schools. Our public schools are a disgrace and damage children long before they decide whether they want to continue to college.

Now that I am an “older American,” I wouldn’t deprive anyone of a joyful life, as I have had, by limiting their opportunities with rigid orthodoxy about college. The university mission should be learning, not class branding. I was lucky. I dodged the branding industry, known as college.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

River view

A perfect day on Rhode Island’s mighty Seekonk River, at the upper end of Narragansett Bay

— Photo by Lydia Whitcomb

Sam Pizzigati: Biden’s Roosveltian tax-the-rich plan

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

President Joe Biden has made no secret of his admiration for Franklin D. Roosevelt. The president proudly displays a portrait of FDR in the Oval Office.

More significantly, he’s announced the most ambitious plan since FDR’s New Deal for enhancing the well-being of working Americans while trimming the fortunes of America’s super rich. The president has promised to fund his big plans for infrastructure, jobs and education entirely with taxes on the top.

In fact, Biden’s new tax-the-rich plan is a good deal more Rooseveltian than the numbers, at first glance, might suggest.

In 1945, when FDR died in office, the nation’s most affluent faced a 94 percent tax on income over $200,000, a little more than $2.9 million in today’s dollars. The rates Biden has proposed come nowhere near those — they’d top out at just 39.6 percent of ordinary income over $400,000. That’s up only slightly from the current 37 percent.

But the gap between Biden’s plan and FDR shrinks big-time when we toss capital gains — the dollars the rich make buying and selling stocks and bonds, property, and other assets — into the picture.

In 1945, the nation’s deepest pockets paid a 25 percent tax on their capital-gains windfalls. Today’s rate tops off at 20 percent. For households making over $1 million in annual income, the Biden plan would raise the top capital- gains tax rate to 39.6 percent, the same top rate that applies to earnings from employment.

In other words, the Biden tax plan ends the most basic tax break for the ultra rich: the preferential treatment they get on the income from their wheeling and dealing. This would be a big deal. In 2019, 75 percent of the benefits from the capital-gains tax break went to America’s top 1 percent.

Dividends currently get the same preferential treatment. Americans making over $10 million in 2018 took in over half of their total incomes — 54 percent — via capital gains and dividends. If Congress adopts the Biden tax plan, the basic federal tax on that 54 percent would just about double, from 20 to 39.6 percent.

The Biden plan also totally eliminates the federal tax code’s open invitation to dynastic family wealth: the “step up” loophole. Under this notorious giveaway, any fabulously wealthy American sitting on unrealized capital gains can pass those gains onto heirs tax-free. The Biden plan short-circuits the simplest route to dynastic fortune.

Under Biden’s tax plan, new dynastic fortunes would have a much harder time taking root. Already existing dynastic fortunes, on the other hand, would still be with us. Biden — like FDR in his day — has not yet warmed to the idea of a wealth tax.

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren led a recent hearing highlighting the enormous contribution that even a 2 percent annual tax on grand fortunes could make. Among the insightful witnesses at the hearing: the 61-year-old Abigail Disney, the granddaughter of Roy Disney, the co-founder of the Disney empire with his brother Walt.

“I can tell you from personal experience,” Abigail Disney told senators, “that too much money is a morally corrosive thing — it gnaws away at your character… It warps your idea of how much you matter, and rather than make you free, it turns you fearful of losing what you have.”

Franklin Roosevelt understood that debilitating dynamic well enough to propose, in 1942, a 100 percent tax on annual income over what today would be about $400,000. Biden hasn’t ventured anywhere close to that level of daring. But he’s certainly come much further than anyone could reasonably have expected.

Sam Pizzigati is the Boston-based co-editor of Inequality.org and author of The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Frank Carini: When you let the sands shift naturally

Dunes on Napatree Point

WESTERLY, R.I.

In late October 2012, about a day after Superstorm Sandy’s initial surge battered much of southern New England’s coast, especially its open-ocean shoreline, Janice Sassi navigated her way through a parking lot here filled with “mountains of mud” to find a “moonscape.”

“The dunes were completely flat,” recalled Sassi, manager of the 86-acre Napatree Point Conservation Area. “I thought it was done. It looked like one big beach.”

Sandy had ripped chunks of beachgrass from sections, and one area was forced back some 30 feet. At that moment and for days after, Sassi was concerned about Napatree Point’s future.

Her friend Peter August, a now-retired University of Rhode Island professor and a Napatree Point science adviser, put her racing mind at ease. The former director of URI’s Coastal Institute told her the resilient peninsula that offers sweeping views of Little Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound, and New York’s Fishers Island would be fine. He reminded her that Napatree Point had previously survived one of the most destructive and powerful hurricanes in recorded history.

The hurricane of 1938, also known as the “Great New England Hurricane,” smashed the peninsula’s 39 2- and 3-story houses that stood just a few feet from the churned-up fury of the Atlantic Ocean. The 3- to 4-foot-high wall in front of those summer homes did nothing to prevent their destruction.

Storm waves broke over roofs and plowed “through the cement seawall as if it were transparent,” R.A. Scotti wrote in her 2003 book, Sudden Sea: The Great Hurricane of 1938.

“If you build on a barrier beach, you are toying with nature,” she wrote.

On the other side of the Napatree Point peninsula, most if not all of the private docks that extended into Little Narragansett Bay were reduced to kindling. Some residents waited out the 100-year storm in the remains of decommissioned Fort Mansfield. Fifteen people died.

The historic ’38 storm, much more so than Superstorm Sandy nine years ago, pummeled the 1.5-mile-long, sand-swept peninsula that curves away from the affluent village of Watch Hill. It severed the connection to Sandy Point, now a mile-long island shared by Rhode Island and Connecticut. In the eight decades since Sandy Point was left afloat, the island has drifted one and a half miles to the north.

More than a century earlier, Napatree Point, which was then densely forested — its name reportedly derives from nap or nape (neck) of trees — was significantly altered by another hurricane. The Great September Gale of 1815 “wiped it clean” and no tree has grown there since, according to Scotti’s book.

Following the hurricane of 1815, Napatree Point was significantly developed, and saw the construction of a boarding house and a hotel. By the end of the century, construction of Fort Mansfield had begun.

Though Sassi, then less than three years into her job after a career in law enforcement, was initially skeptical of August’s reassurances that her beloved Napatree Point would rebound, she’s thankful it did. She said it took about five years for the conservation area to completely repair itself. The beachgrass regrew, and the dunes regained their elevation.

Napatree Point was able to heal itself because humans have given it room to breathe. After the ’38 hurricane, one of the most financially destructive storms on record, developers looking to rebuild the summer cottages and construct other structures were rebuffed.

With no roads, homes, and hardened structures obstructing Mother Nature, Napatree Point has been allowed to change with the times. August noted that the barrier beach has the space to continually wash back over itself.

“It doesn’t erode away. It just moves,” said August, who founded URI’s Environmental Data Center three decades ago. “Napatree Point was 80 acres when the hurricane of ’38 struck; it’s 80 acres now, just in a different place. Napatree Point will always be here. It rolls with the punches. It gets changed but still exists.”

The Hope Valley resident said the geology of Napatree Point is a perfect example of how a barrier dune ecosystem works naturally. He explained that when Napatree Point is hit by big storms, such as the Great New England Hurricane or Superstorm Sandy, and wave action and tidal surge punch through the dunes, it creates wash-over fans on the backside, meaning the position of the peninsula’s dunes change; they aren’t lost.

“They’re rolling over themselves and they can do that because we’re letting the sand go where the sand wants to go,” August said.

Napatree Point is owned, managed and protected by a partnership of different interests: the Watch Hill Fire District, the Watch Hill Conservancy, which employs Sassi, the Town of Westerly, the state, and a few private landowners. Conservation easements protect it from future development.

In the summer, this slender strip of land — the average width is 517 feet — at the mouth of Little Narragansett Bay, where the Pawcatuck River empties into Block Island Sound, is overrun with tourists, boaters, beachgoers, hikers, anglers and nature observers. Finding a scrap of beach can be difficult, and some areas are roped off for important visitors, most notably piping plovers and American oystercatchers, both of which nest in the sand.

Sassi is thrilled that Napatree Point is so popular, but all the human visitors have an accumulating impact on the peninsula’s delicate dune system. The West Warwick, R.I., resident noted that the fact there is no development makes it easier for the small peninsula to defend itself from a changing climate and human intrusion.

The conservation area, however, isn’t immune to sea-level rise and other stressors associated with the climate crisis. About three years ago, Sassi and August began noticing that the entrance to Napatree Point, through a large parking lot off Bay Street that is lined with boutique shops and a mix of culinary options, began to flood during extremely high tides.

It’s now beginning to flood even during normal high tides. As sea levels rise and more frequent flooding occurs, access to the peninsula, at least via land, will become more and more restricted unless something is done. August said plans are underway to elevate the entrance, which laps up against Watch Hill Harbor.

Napatree Point is a barrier beach that has been shaped and reshaped by storms, sometimes profoundly, as was the case 206 years ago, 83 years ago, and nine years ago. The peninsula is composed of more sand than soil and its shoreline is worked upon daily by ocean waves and the tide. Like most barrier beaches, especially those with no human-made structures, Napatree Point is constantly in a state of flux. Since 1939, it has shifted north, toward Little Narragansett Bay, some 200 feet, according to mapping by the Coastal Resources Management Council.

The peninsula, however, is much more than a summer destination and a birdwatcher’s paradise. It’s also a habitat provider and a storm protector.

This fragile yet pliable barrier beach helps protect Westerly’s mainland. And to help protect Napatree Point’s dynamic ecosystem — and, thus, tourist-friendly Watch Hill — from storm surge, coastal erosion, and human visitors, a number of restoration projects have been undertaken.

During the past dozen years, some 4,000 native plants, such as seaside goldenrod, beach plum, swamp milkweed and groundseltree, have been added to help anchor Napatree Point’s shifting sands — their dense root mats keep erosion in check — and to attract pollinators.

Split-rail fences have been erected and signs posted to keep visitors and their wheeled coolers from making their own paths from the peninsula’s protected side to its open-ocean side. At one point several years ago, 50 crossover paths had been plodded through Napatree Point’s dunes and vegetation. Dinghies and Zodiacs land on the Little Narragansett Bay/Watch Hill Harbor side, before their occupants traverse the peninsula to the Atlantic Ocean side, where they lie in the sun, swim, and bodysurf.\

This tireless restoration work piloted by Sassi, August, Hope Leeson, Bryan Oakley and others has made Napatree Point a national model for stewardship, an important distinction since the area caters to an abundance of life, including mussel beds, bats, minks, foxes, deer, monarch butterflies, and a plethora of birds.

Off its coast are some of the biggest and healthiest eelgrass beds in Rhode Island waters. These vital marine ecosystems provide foraging areas and shelter to young fish and invertebrates, spawning surfaces for sea life, and food for migratory waterfowl. Gray and harbor seals hang out on the open-ocean side of the peninsula. In the winter, rafts of sea ducks are a common sight in the waters off the peninsula.

The Audubon Society has recognized Napatree Point as a globally important bird area. Veteran Rhode Island birder Rey Larsen has identified more than 300 different species of birds on the sandy, wind-swept peninsula.

The Napatree Point lagoon, about 3.5 feet deep in the middle, is home to a half-dozen different kinds of fish, including the American eel. It’s also an important horseshoe-crab nursery. The entrance to the 10-acre lagoon, from Little Narragansett Bay, is the peninsula’s most rapidly changing part, according to August. He said the entrance to the lagoon has moved a few times during the past decade alone.

Napatree Point, unlike much of Rhode Island’s built-up coastline, is better positioned to handle the climate crisis because humans are allowing its sands to shift naturally.

“The most important thing we can do is get people excited about Napatree Point so they want to protect it,” Sassi said.

For a wealth of science, stewardship, and monitoring information about the Napatree Point Conservation Area, click here.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Watch Hill and Watch Hill Cove from the eastern end of Napatree Point

‘A sense of ocean and old trees’

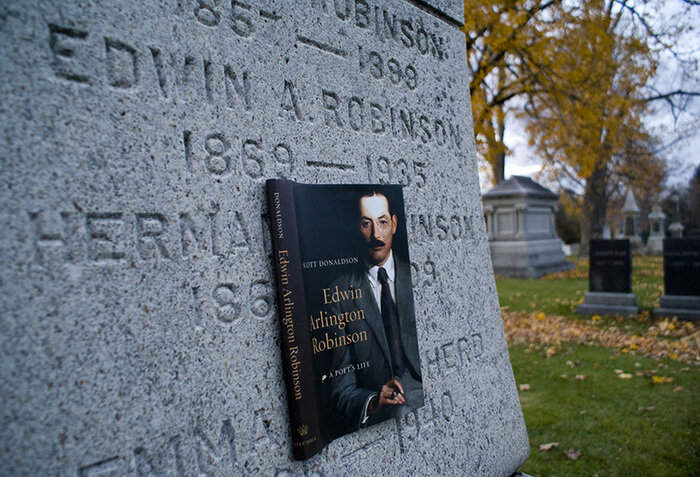

“Edwin Arlington Robinson (1916),’’ by Lilla Cabot Perry, in the Colby College Special Collections, Waterville, Maine

She fears him, and will always ask

What fated her to choose him;

She meets in his engaging mask

All reasons to refuse him;

But what she meets and what she fears

Are less than are the downward years,

Drawn slowly to the foamless weirs

Of age, were she to lose him.

Between a blurred sagacity

That once had power to sound him,

And Love, that will not let him be

The Judas that she found him,

Her pride assuages her almost,

As if it were alone the cost.—

He sees that he will not be lost,

And waits and looks around him.

A sense of ocean and old trees

Envelops and allures him;

Tradition, touching all he sees

Beguiles and reassures him;

And all her doubts of what he says

Are dimmed with what she knows of days—

Till even prejudice delays

And fades, and she secures him.

The falling leaf inaugurates

The reign of her confusion;

The pounding wave reverberates

The dirge of her illusion;

And home, where passion lived and died,

Becomes a place where she can hide,

While all the town and harbor side

Vibrate with her seclusion.

We tell you, tapping on our brows,

The story as it should be,—

As if the story of a house

Were told, or ever could be;

We’ll have no kindly veil between

Her visions and those we have seen,—

As if we guessed what hers have been,

Or what they are or would be.

Meanwhile we do no harm; for they

That with a god have striven,

Not hearing much of what we say,

Take what the god has given;

Though like waves breaking it may be,

Or like a changed familiar tree,

Or like a stairway to the sea

Where down the blind are driven.

“Eros Turannos,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935), who was born in the Alna, Maine, village of Head Tide, but grew up — generally unhappy — in Gardiner, Maine. The three-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry spent much time at the famous McDowell Colony, an artist residency in Peterboro, N.H. He died in New York and is buried in the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery in Gardiner.

Gardiner’s Park and Palmer Fountain in 1909. Melted down for the World War I war effort, the bronze statue was later replaced.

Safely anonymous nudity

'‘Finsta Self’' (oil on paper), by Eben Haines. at the Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine

Don Pesci: The City Mouse fatalistically faces the spreading stupidity pandemic

1912 Drawing derived from the Aesop’s Fables tale “The Town Mouse and The Country Mouse,’’ by Arthur Rackham

VERNON, Conn.

The merry month of May has burst upon Connecticut. The City Mouse went to lunch in Hartford with one of her lady friends – sans mask, while they were eating – and a conversation arose concerning the age-old quarrel between city and country.

The City Mouse is a no-nonsense character, a quality disappearing quickly in our homogenously progressive Connecticut culture -- Connecticulture? -- and differences of opinion clouded the air.

The City Mouse was not surprised that Yale law students had launched a lawsuit against a wealthy suburb because, the students asserted, Woodbridge had, through its zoning regulations, frustrated the construction of low-rent housing in what had been historically a predominantly middle-class municipality. If the suit were to be decided in favor of the Yale students, a certain percentage of low-income housing would be required in all Connecticut municipalities, not solely in Woodbridge.

“Law students will be law students,” the City Mouse said, “but the zoning regulations in Woodbridge are not racist. They regulate lot size, which has attracted middle-class homeowners to Woodbridge. How many Yale students finding employment opportunities in Connecticut’s Gold Coast, or in an increasingly impoverished New York City, have over the past few decades settled in Woodbridge rather than, say New Haven? How many of New York's tax-tortured residents have moved to New Haven rather than Woodbridge or other Connecticut Gold Coast communities? The students’ attack upon zoning regulations in Woodbridge is what it appears to be on its face – an assault upon representative municipal governance first by the courts and, at some point in the near future, by a compliant progressive legislature.”

Their server, Brian, approached to refill their wine glasses. He was a young man – well educated, both could see – who was working his way through college. He had been at a Connecticut university for a couple of years, gliding through on a partial scholarship, and both had talked with him at length before.

“Brian,” Lady Friend said, “your restaurant appears to be reviving now that Coronavirus restrictions have been lifted. Good for you, right?”

“Yes. There’s plenty of work. But a different problem has cropped up.”

“Ah,” Lady Friend asked, “What is it?”

This question caused some unease. Brian, suitably masked, looked cautiously over his shoulder, then ventured in a whisper, “The restaurant is having a problem securing help.”

“From state and federal government, you mean?”

“No, everyone there wants to undo the harm they’ve done through shutdown regulations. Help… you know, servers, dishwashers and the like.”

Looking conspiratorially over her shoulder, The Country Mouse said, “Well, no slur intended on you, Brian, but you don’t need a Harvard education to serve food and wash dishes. And there is a huge untapped, unemployed population in Hartford that has not graduated from Yale or Harvard law schools and may be tapped to work in restaurants -- so, what’s the problem?”

“They have other means.”

“I don’t understand,” said Lady Friend.

And here, the City Mouse broke in. “Brian is suggesting that welfare payments and superior benefits keep the unemployed on the public payroll.”

“Is that it?” Lady friend asked, a note of quiet desperation in her voice.

“That’s it,” Brian said, and sped off to another table.

“I can’t imagine,” the City Mouse said, with a sardonic trill in her voice, “what the solution to that problem might be, apart from bringing restaurants onto the public dole. State support of restaurants could be sold on the supposition that restaurants might be better managed by legislators rather than restaurant owners. But you and I know -- don’t we? -- that it would drive up the cost of everything. Just look at the spikes over the past five decades in welfare costs, state employee salaries and pensions and so called ‘fixed costs,’ which cannot legislatively be unfixed without unseating certain legislators.”

“Imagine that,” said Lady Friend, “you solve one problem, and another knocks you on the head.”

“Like sowing dragon’s teeth,” the City Mouse mused.

The problem has been solved, I reported to The City Mouse. On May 3, the Hartford City Council proposed an equitable solution: “City exploring universal basic income.”

The lede to the story in a Hartford paper ran as follows: “The city of Hartford is considering experimenting with a universal basic income [UBI], starting with designing a pilot program that would give no-strings-attached monthly payments to participating city residents.”

The program would “target single, working parents, with a goal of learning whether extra, guaranteed income improves recipients’ physical and emotional well-being, job prospects and financial security.”

The lessons apparently already have been learned by the City Council.

The story bulges with approving quotes from a University of Connecticut economist, the council president, various council members, all Democrats, and a solitary Working Families Party member. Those outside Connecticut should know that the state’s Working Party lives in the basement of the state’s progressive Democrat Party.

A 2018 study of a similar UBI program in Alaska, the paper reported, found that “it did not increase unemployment as some critics feared and had actually increased part-time work.”

“So, no need to worry anymore,” I teased The City Mouse.

Her response, delivered with a painful sigh: “If only stupidity were as easy to dispose of as Coronavirus.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Summer as verb

View of summer houses in Hampton Bays, on Long Island

— Photo by Masterchief1307

“When I left the State of Maine for college, I met my first really rich friends, and I discovered summer could be a verb.’’

— Alexander Chee (born 1967 in Rhode lsland but spent much of his youth in Maine), novelist, poet and nonfiction writer. He now teaches at Dartmouth College.

They come and they go and they come back

2020 U.S. Census enumerator’s kit

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

The 2020 U.S. Census figures, in general, weren’t surprising. Population growth slowed to 7.4 percent in the stretch since 2010, the lowest since the Great Depression, when the population only rose 7.3 percent. The Sunbelt continued to draw many new residents, though not as fast as most demographers had predicted. So the Sunbelt’s megastates – Texas and Florida – picked up congressional seats – Texas two and Florida one; the economic dynamo North Carolina also got one new seat. (I don’t include California in the Sunbelt. It lost a seat.)

The big news around here (which surprised me) was that Rhode Island held onto enough people to retain its two congressional seats. Massachusetts will keep its nine seats and Connecticut its five. I attribute much of Rhode Island’s minor triumph to the great wealth-and-job-creation machine of Greater Boston, which spills into Rhode Island.

The Census data let New England maintain its 21 seats in the U.S. House, where for the first time in a half-century none of the region’s six states lost a seat!

Indeed, I wouldn’t be surprised if the more attractive and prosperous parts of the North, especially New England, see substantial population increases in the next decade as the Sunbelt problems cited below lead to some reverse migration, spawned by our relatively moderate weather (and lots of freshwater) and our rich technological, health-care and education complexes, beauty, generally low crime rates and sense of community and history. In any event, I doubt that the population of the country as a whole, or the economy, will surge in the Twenties, which unlike the last century’s Twenties, probably won’t be “roaring’’ for long. The demographics, including our low birth rate, don’t suggest a long-term national boom (or crash) is coming.

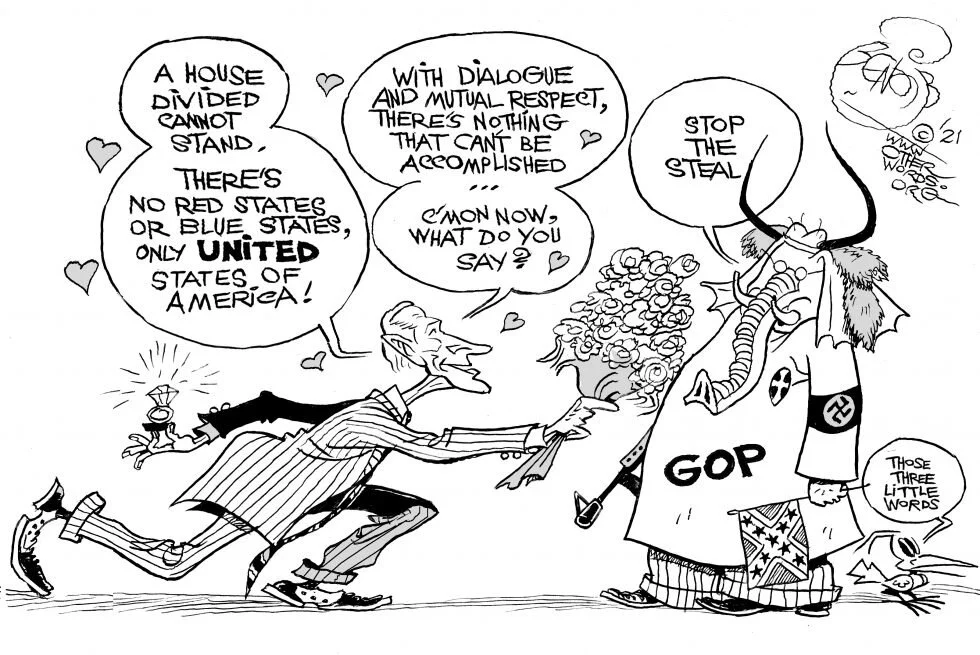

The assumption has been that the Census data will give the increasingly far-right Republican Party yet more clout. Maybe in the short run, but the folks moving into Sunbelt states from the Northeast, Rust Belt and California include many liberals who continue to want the sort of Democratic Party-promoted public services they had back north and in California. Thus, especially in Sunbelt metro areas, Democrats are fairly steadily increasing their share of the electorate. Strange political times! The Democrats have been moving toward European-style social democracy while parts of the GOP embrace neo-fascism.

The migration to the Sunbelt, although it’s slowing, is putting ever-increasing strains on its states’ generally thin social services and inadequate public infrastructure, as witness the Texas power-grid collapse in February.

The Sunbelt increasingly faces the heavy traffic, soaring home prices and other aspects of density that metro areas of the Northeast and California have long had to deal with. Addressing them will require major political and policy changes. The low taxes (except sales taxes), cheap real estate and wide open roads will not continue in large parts of the Sunbelt.

And this comes as the South faces the nation’s worst effects (with the possible exception of California) of global warming – including stronger hurricanes and other storms, more floods, more droughts and longer heat waves. God help Florida and the Gulf Coast as the seas keep rising.

The climate crisis has already turned away some people from the South, even as it requires very expensive infrastructure work to address. That means higher taxes, which the GOP hates more than anything else, especially when they’re imposed on the wealthy. The two most important Republican constituencies are the very rich (many of them via inheritance) and rural and exurban voters.

So I think that the Sunbelt will become increasingly politically competitive. The Census figures strongly suggest that. And New England will do all right, with or without “climate refugees.’’

Going forward, the New England states would do well to cooperate in formulating tax and other policies so as not to cannibalize themselves in marketing the compact region to business and individuals, especially to those in the Sunbelt and the Mountain States, the other high-growth region, that might be having second thoughts about where they’ve moved to in recent years.

The joy of junk mail

“Fish” (detail), by Elif Soyer, in her show “Bycatch,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, May 5-30.

The gallery says:

“The work in ‘Bycatch’ began as Elif Soyer’s ongoing attempt to journal while repurposing mounds of unsolicited junk mail, layering the mundane over the mundane. Soyer says she recognized mid-way through hanging her previous shows, ‘Balance Due’ and ‘Daily,’ that this theme was one that she would keep drawing on while incorporating ‘refuse’ from previous projects. Paper, pencil, acrylic, cloth, string, tempera, pen, watercolor, junk mail, and bills produce textured and subtle imagery suggestive of, variously, lichen, ear canals, viruses, eyeballs, branches, phrases, fish, neurons and plants, familiar motifs from the artist’s canon.

“Says Soyer: ‘The materials, the drawing, writing, and painting are informed by the way I see: space filled with layers and layers, textures, forms and contrast yet always space - the eye takes in so much, the net captures what was not intentionally looked for as well as my original focus. My friends and family say that my untraditional aesthetic must be influenced by my bi-cultural Turkish/American upbringing, surrounded by mosaics, textiles, and tapestries rich in contrast. My bycatch collects clashing materials that co-exist just the same, and eventually manage to coalesce into their own environment.”’

Acting like idiots sells

Johnny Damon at bat for the Red Sox in spring training in 2005

“We’ve got the long hair, we’ve got the cornrows, we’ve got guys acting like idiots. And I think the fans out there like it.’’

— Johnny Damon, former outfielder for the Boston Red Sox, which he played for in 2002-2005

For an NRA meeting

“Still from 'Hand Catching Lead'‘ (two-color lithograph/screenprint), by Richard Serrra, in his show “Richard Serra: Selected Prints,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., starting May 8.

The gallery says:

“In collaboration with master printers Gemini G.E.L., the exhibition will include monochromatic works from different series executed in the last 15 years. Serra’s explorations with printmaking have been an extension of the artist’s practice of working in monumentally-scaled sculpture. Since 1972, he has been working with Gemini to create and invent new techniques in the medium, leading to a varied output of complexly surfaced prints.’’

David Warsh: The Blake Bailey case and the logic of woke

Blake Bailey in 2011

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“Society is a game with rules, people are players in this game, and politics is the arena in which we affirm and change these rules. Unlike the rules in standard game theory, however, social rules are continually contested by players allying to scrap old rules and create new rules to serve their purposes.”

That framing, by Herbert Gintis, in the first paragraph of Individuality and Entanglement (2017), struck me as particularly apt when I read it. It’s been useful to me ever since in understanding matters large and small.

Take the case of Blake Bailey’s biography of the novelist Philip Roth, now withdrawn from print. Its publisher, W.W. Norton, returned the manuscript to the possession of its author, along with that of Bailey’s memoir, The Splendid Things We Planned, which Norton published in 2014.

Ten days ago, The New York Times reported that accusations of sexual assault and other bad behavior by Bailey, 57, had led the publisher to stop shipping and promoting the book, which had just that week reached the Times’s best-seller list.

Two days after that, Terry Pristin, a former reporter for The Times, in a letter published on the paper’s editorial page, wrote, “If Blake Bailey, Philip Roth’s biographer, is credibly accused of rape and attempted rape, let him be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. But why punish the rest of us? Don’t prevent me from reading a biography that no less a writer than Cynthia Ozick has labeled a ‘narrative masterwork.’”

The difference between the front-page treatment the story received initially, and the less prominent play, on page B4 in the business section, of the news that the publisher had taken out of print its editions of both books, reflected contesting opinions about the story’s significance, perhaps even within the newspaper. Then again, the second story, being a follow-up and so subsidiary to the first story, may have reflected nothing more than classic journalistic procedure.

Bailey has adamantly denied the charges.

The most interesting details had to do with the timing of the allegations, their nature, and the manner in which they were communicated to the publisher. Most of these were spelled out with clarity in The Times’s account.

It was apparently in 2018, that a publishing executive, Valentina Rice, using a pseudonymous email account, wrote to Julia A. Reidhead, the president of Norton, accusing Bailey of non-consensual sex three years earlier, when both had been overnight guests at the home of a Times book critic and his wife. She also emailed a Times reporter, who responded, but Ms. Rice decided not to pursue it further and did not reply.

“I have not felt able to report this to the police but feel I have to do something and tell someone in the interests of protecting other women,” she wrote to the publisher, adding: “I understand that you would need to confirm this allegation which I am prepared to do, if you can assure me of my anonymity even if it is likely Mr. Bailey will know exactly who I am.”

The publisher did not respond to her note, Rice told The Times. But a week later Rice received an email from Bailey, who said that Norton had forwarded her complaint.

“I can assure you I have never had non-consensual sex of any kind, with anybody, ever, and if it comes to a point I shall vigorously defend my reputation and livelihood,” he wrote in the email, which Rice shared with The Times, though it is not clear when. “Meanwhile, I appeal to your decency: I have a wife and young daughter who adore and depend on me, and such a rumor, even untrue, would destroy them.”

In other words, Rice wrote Norton just as the Me Too movement gathered steam. It was some months after The Times and The New Yorker had published the stories about powerful Hollywood sexual predators for which they were awarded the 2018 Public Service Pulitzer Prize.

What was the president of Norton thinking? What did Blake Bailey think to himself? What did the publisher and author think might or might not happen when the biography eventually appeared? Litigation and much shoe-leather reporting seem sure to ensue. We can hope that eventually a satisfying reconstruction will appear, along the lines of other careful post-mortems of furiously contested events: Sanford Ungar’s The Papers and the Papers: An Account of the Legal and Political Battle over the Pentagon Papers (1974); Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer (1990), about the strategies of authors dealing with sensational events (in this case, the murder of a Green Beret physician’s daughters and pregnant wife); Devlin Barrett’s October Surprise: How the FBI Tried to Save Itself and Crashed an Election (2020), about FBI decision-making in the last months of the 2016 presidential election. I should mention how proud I am that that Norton published my Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (2006). Like many others, I consider the company to be among the very best in the industry.

In the meantime, the story of the Roth biography is one more illustration of how culture changes and why: social rules are contested by allies who, often successfully, seek to scrap old rules and create new ones to serve their purposes. Call me cynical, but I believe that the relevance of stories about movie mogul Harvey Weinstein’s predatory behavior was driven home by Donald Trump’s election to the presidency, despite plentiful evidence of his sexual misconduct. Heightened attention to racial inequities, exemplified by the Black Lives Matter movement, was stoked even more by the murder of George Floyd.

There are times when the law is not enough.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first appeared.

Editor’s note: Roth lived for many years in Warren, Conn., in a 1790s farmhouse. For a look:

http://www.klemmrealestate.com/properties_details_pk.php?For%20Sale-2255

Bailey’s other books include {John} Cheever: A Life, about that great short-story writer and novelist, who though he lived most of his life in and around New York, never ceased to be a New Englander.

Frank Carini: The vast poisoning that goes with maintaining lawns

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The amount of pollution, from noise to air to water, created to maintain green carpets and immaculate yards is jarring. Lawn mowers, weed whackers, leaf blowers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and fertilizers. Much of this effort is powered by or made from fossil fuels.

Lawn-care equipment is typically powered by two-stroke engines. They are cheap, compact, lightweight, and simple. They are also highly polluting, generating up to 5 percent of the country’s air pollution, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Each weekend for much of the year, according to estimates, some 54 million Americans mow their lawns. All this weekend grass cutting uses some 800 million gallons of gasoline annually. That doesn’t include the gas used to trim around trees and fences and to blow grass clippings around.

Those 800 million gallons also don’t include the gas used for lawns mowed during the week or by landscaping companies. It doesn’t include the oil that is also burned by these cheap engines. It doesn’t include grass cut on golf courses and along median strips and other public spaces covered by green carpets devoid of diversity.

A 2011 study showed that a leaf blower emits nearly 300 times the amount of air pollutants as a pickup. The EPA has estimated that lawn care produces 13 billion pounds of toxic pollutants annually.

This equipment is also noisy. Leaf blowers emit between 80 and 85 decibels, but cheap or mid-range ones can emit up to 112 decibels. Lawn mowers range from 82 to 90 decibels. Weed whackers can emit up 96 decibels of noise.

Electric lawn equipment is gaining in popularity and will slowly lessen the amount of fossil fuels burned to cut millions of acres of grass — a 2005 study found that about 40 million acres in the continental United States has some form of lawn on it. Electric equipment is also quieter than its gas-powered counterparts.

Much of the 90 million pounds or so of fertilizer dumped on lawns annually are fossil-fuel products. Nitrogen fertilizer, for instance, is made primarily from methane.

As stormwater carrying nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizer runs off into streams and rivers and eventually into larger waterbodies such as Narragansett Bay, it impacts ecosystems and fuels algal blooms, some toxic, that suck oxygen from water.

On Rhode Island’s Aquidneck Island, for example, stormwater runoff carrying these nutrients is stressing coastal waters and contaminating the reservoirs that feed the Newport Water System.

The amount of toxic chemicals applied to lawns and public grounds annually to jolt grass to life and kill pests is staggering. This copious amount of poison, about 80 million pounds annually, is marked by white and yellow flags warning us not to let children or pets onto these monolithic spaces whose appearance trumps their health and that of the surrounding environment.

These warning flags are planted because of the 30 commonly used lawn pesticides 17 are probable or possible carcinogens; 11 are linked to birth defects; 19 to reproductive impacts; 24 to liver or kidney damage; 14 possess neurotoxicity; and 18 cause disruption of the endocrine (hormonal) system. Another 16 are toxic to birds; 24 are toxic to aquatic life; and 11 are deadly to bees.

Of course, these poisons don’t just kill or harm their intended targets.

While these chemicals hang around “feeding your lawn” or killing life, they are breaking down and working their way into the environment — until another application is applied, sometimes just a few weeks later, and the cycle repeats.

Poisons from these artificial fertilizers and the various -cides applied to lawns can seep into groundwater — contaminating drinking-water supplies — or turn to dust and ride the wind. They cling to people and pets who walk, run, and lie on treated grass. They get kicked up during youth sporting events.

These chemicals can be inhaled like pollen or fine particulates, causing nausea, coughing, headaches, and shortness of breath. For asthmatic kids, they can trigger coughing fits and asthma attacks.

Two of the most common pesticides, glyphosate used in Roundup and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) in Weed B Gon Max, have been linked to a number of health issues, including developmental disorders and cancer. The latter is a neurotoxicant that contains half the ingredients in Agent Orange, according to Beyond Pesticides, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has called 2,4-D “the most dangerous pesticide you've never heard of.”

Developed by Dow Chemical in the 1940s, the NRDC says this herbicide helped usher in the green, pristine lawns of postwar America, ridding backyards of vilified dandelion and white clover.

Researchers have observed apparent links between exposure to 2,4-D and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and sarcoma, a soft-tissue cancer, according to the NRDC. It notes, however, that both of these cancers can be caused by a number of chemicals, including dioxin, which was frequently mixed into formulations of 2,4-D until the mid-1990s.

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer declared 2,4-D a possible human carcinogen.

Last year Bayer paid nearly $11 billion to settle a lawsuit over subsidiary Monsanto’s weedkiller Roundup, which has faced numerous lawsuits over claims it causes cancer.

Lawns are one of the most grown crops in the United States, but unless you are a goat or a dog with an upset stomach their nutritional value is zero. Yet the collective we continues to spend about $36 billion a year on lawn care.

Instead of putting public health at risk and degrading the environment with a chemically treated lawn, create a yard with a diverse mix of native trees, shrubs, and plants; it is cheaper to maintain, easier to take care of, environmentally beneficial, and more interesting.

Native plants support native wildlife and insects, are accustomed to the weather and soil, and are pest resistant. They support the pollinators of our food crops, clean the air and water, and help regulate the climate. They also make good natural buffers, which capture rainfall and filter stormwater runoff.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

The first gasoline-powered lawn mower, 1902

‘Burning into retinas'

Sugar maple in May

“Who knows

What it is that’s keeping the trees from appearing to us

The way they appear to the lifelong blind stricken

Unexpectedly with sight, blots and flashes of scarifying

green burning into retinas.’’

“Spring Morning,’’ by Tom Sleigh (born 1953), American poet and professor at Dartmouth College and elsewhere

Llewellyn King: Interconnectivity at the heart of the revolution that’s upon us

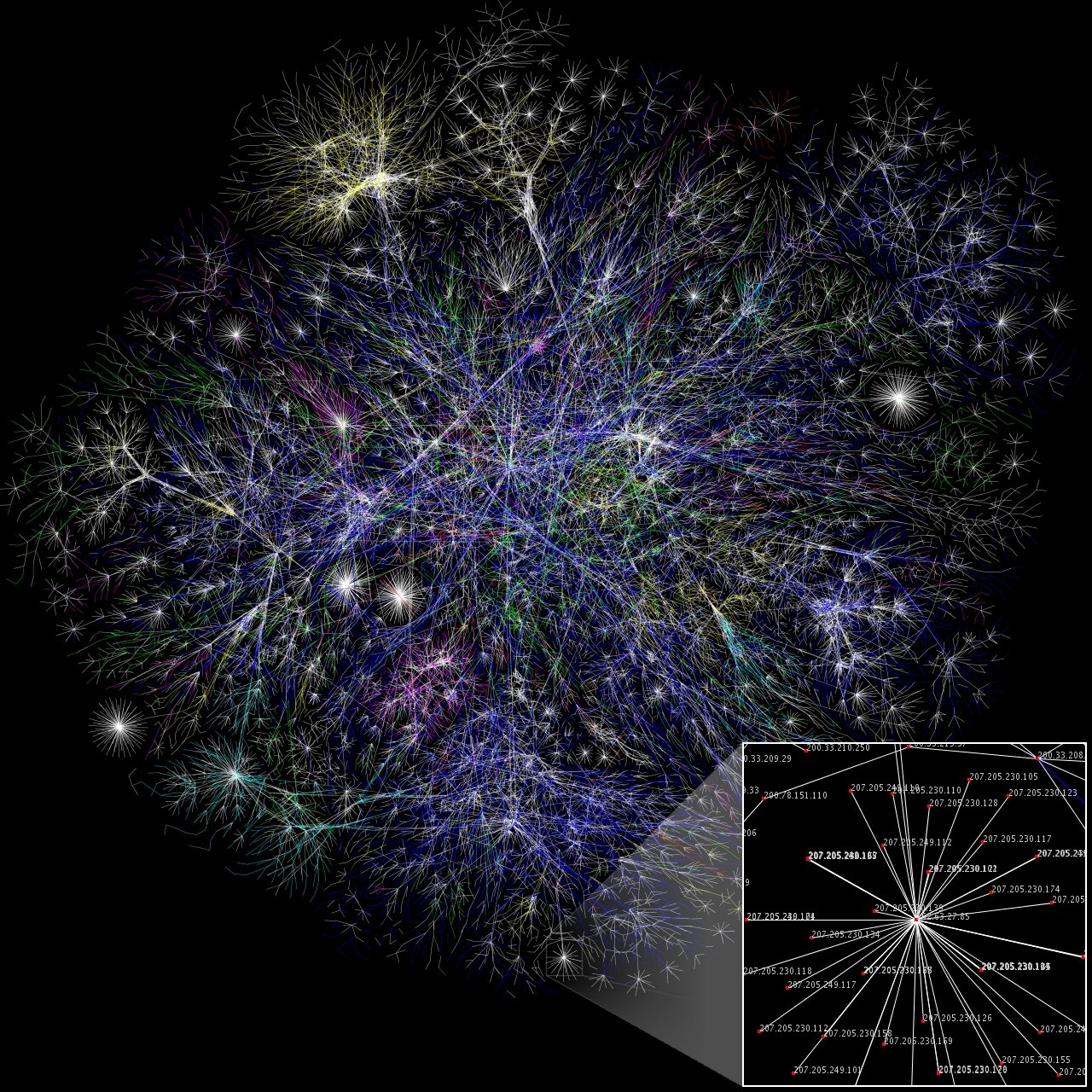

Visualization from the Opte Project of the various routes through a portion of the Internet

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When we look back on the convulsion that is going to reset America — the great technology-driven revolution that will extend to nearly every corner of American life — it may be named for President Joe Biden, but it won’t be his revolution. It is innovation’s revolution. He will help finance it and smooth it out, but it is already happening and is accelerating.

Biden’s typically soft speech to Congress (no stemwinder he) was a wish list of things dear to him, but also an acknowledgement of what already is in motion.

Technology is rampant and government’s role should be to provide partnership and, above all, standards, according to two savants of the tech world, Jeffrey DeCoux, chairman of the Autonomy Institute, and Morgan O’Brien, a visionary in U.S. wireless telecommunications, now executive chairman of Anterix, a company providing private broadband wireless networks to utilities. Above all, they said in an interview with me for the PBS program White House Chronicle, standards for the new technology are essential.

Partial interconnection with different appliances, from road sweepers to drone delivery vehicles speaking only to identical devices, will be self-defeating. The internet without international standards would have failed.

Biden is set to preside over the greatest industrial leap forward since steam provided shaft horsepower to make factories a reality. If Congress allows, the Biden administration will finance much of the upgrading of the old infrastructure. It also will be called upon to be part of the new infrastructure, the technological one. That will be expensive; both DeCoux and O’Brien warned that it will take huge sums of money to build out complete 5G broadband networks, which will carry the load of interconnectivity.

For the nation to leap forward, these networks need to bring 5G broadband to every corner of it, O’Brien said. It can’t be allowed to serve only those places where population density makes it profitable.

In his speech to Congress, Biden laid out a revolutionary abstract for the future of the nation. The human side of the Biden infrastructure plan -- things like day care, free community college, better health care, prescription drug pricing -- is the true Biden agenda.

The technology revolution is seen by the president not for what it is, a resetting of everything in America, but rather as a way to job creation. It will create jobs, but that isn’t the driving force. The driver is and has been innovation: science helping people. That, in turn, will bring about a surge of productivity and prosperity and with that, new jobs, quality jobs – robots will soon be flipping hamburgers and painting houses.

This other agenda, the one that will make the fundamental difference between the nation of today and the nation of tomorrow, is the technological revolution. The evolutionary forces for this upheaval have been gathering since the microprocessor started things moving in the 1970s.

At the core of the coming changes is interconnectivity. That is what will craft the future. Cars on highways will be connected with each other through thousands of sensors, and these will speed traffic and enhance safety both for those with drivers and new autonomous ones. Likewise, drones will deliver many goods and they will need to be interconnected and have superior flight management. Every aspect of endeavor will be involved, from managing railroads to increasing electricity resilience and the productivity of the electric infrastructure.

In an interview on the Digital Roundtable, a webinar from Texas State University, this past week, Arshad Mansoor, president of the Electric Power Research Institute, said improved interconnectivity could increase available electricity from dams and power plants often without new construction. He explained that interconnectivity wouldn’t only be essential to managing diverse generating sources, like wind and solar, but also in wringing more out of the whole system.

Technology has gotten us through the pandemic. Most obviously in the huge speed at which vaccines were developed, but also in our ability to meet virtually and the effectiveness of online ordering and delivery.

By nature, and by record, Biden is a get-along-go-along politician, a zephyr, as we heard in his address to Congress. But history looks as though it will cast him as a transformative president, a notable leader presiding over great winds of change.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Autopilot system in Tesla car

'Its own excuse for being'

Rhodora, a common flowering shrub of the New England

In May, when sea-winds pierced our solitudes,

I found the fresh Rhodora in the woods,

Spreading its leafless blooms in a damp nook,

To please the desert and the sluggish brook.

The purple petals fallen in the pool

Made the black water with their beauty gay;

Here might the red-bird come his plumes to cool,

And court the flower that cheapens his array.

Rhodora! if the sages ask thee why

This charm is wasted on the earth and sky,

Tell them, dear, that, if eyes were made for seeing,

Then beauty is its own excuse for Being;

Why thou wert there, O rival of the rose!

I never thought to ask; I never knew;

But in my simple ignorance suppose

The self-same power that brought me there, brought you.

“The Rhodora: On Being Asked, Whence Is The Flower,’’ by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

Impressionist loyalty

“Spruce in Snow” (circa 1912, oil on canvas), by Alice Ruggles Sohier, in the show (with the work of Frederick A. Bosley) “Twilight of American Impressionism’’ at the Portsmouth (N.H.) Historical Society.

The two were painting at a time when realistic art was falling out of fashion in favor of more abstract art. Regardless, Sohier and Bosley painted impressionist works until their deaths, in the mid-20th Century.

Chris Powell: The best reason to raise taxes on the rich

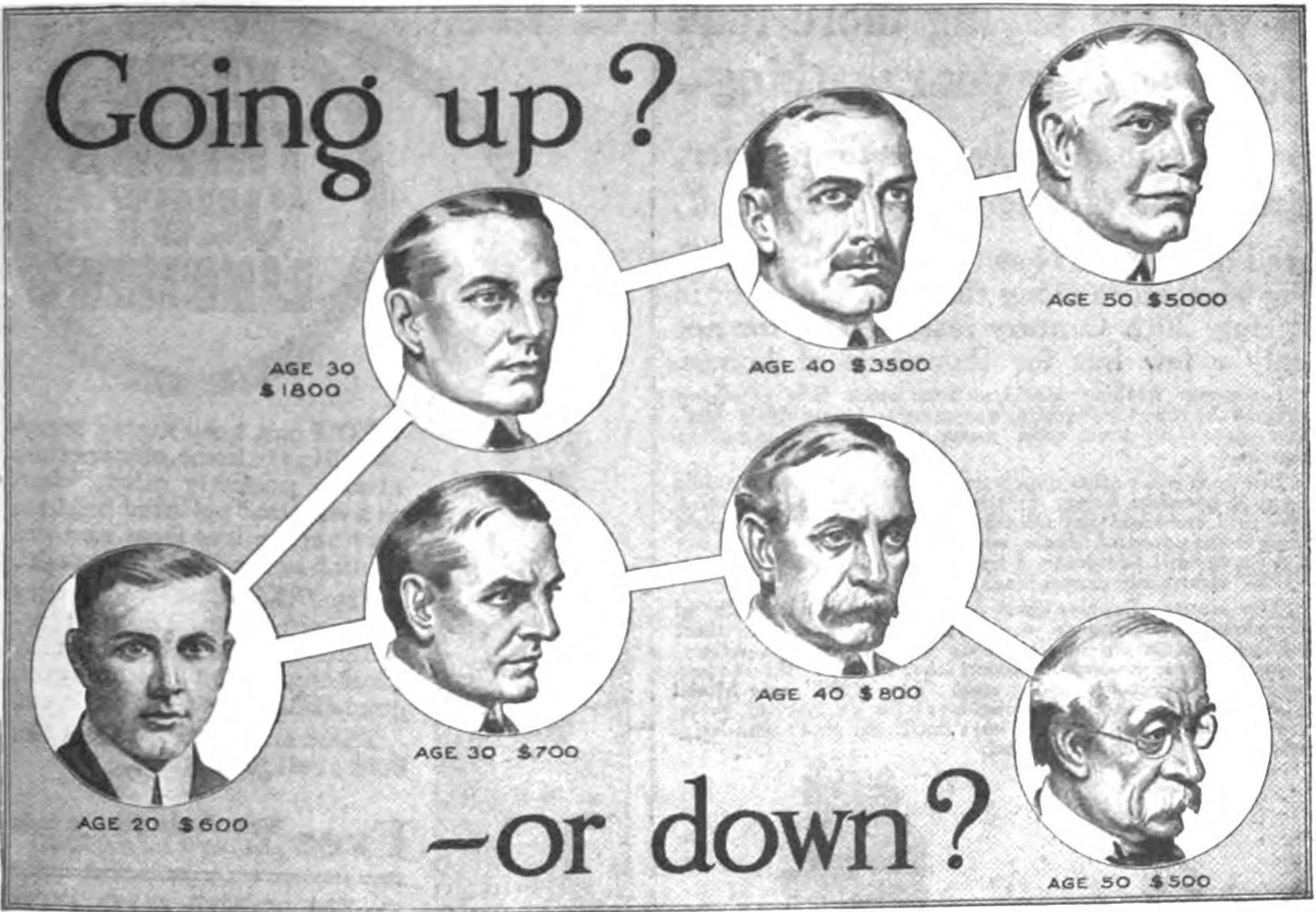

Illustration from a 1916 advertisement for a U.S. vocational school. Education has been seen as a key to higher income, and this advertisement appealed to Americans' belief in the possibility of self-betterment, and addressing the great income inequality existing during the Industrial Revolution.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

While there is a compelling reason to raise taxes on the rich, it's not the reason motivating many Democrats in the Connecticut General Assembly, who would increase both state income and capital-gains taxes on the rich and impose a special state property tax on their expensive homes.

These Democratic legislators want mainly to increase state government's political patronage, the compensation of government employees and the dependence of the poor on government. Connecticut's quality of life seldom improves from their legislation. The state's problems are never alleviated, much less solved, while state government keeps manufacturing poverty.

Besides, state government is already rolling in federal "stimulus" money, with $6 billion of it waiting to be allocated by Gov. Ned Lamont and the legislature. Properly allocated, that largesse should keep state government manufacturing poverty quite without any new taxes for years.

Nor is the reason offered by Democrats in Congress for raising federal taxes on the rich any good -- to increase the government's revenue.

For the virus epidemic already has pushed the federal government into implementing Modern Monetary Theory, which holds that government can create and disburse infinite money without levying taxes, constrained only by depreciation of the currency. The trillions of dollars recently created may go onto the government's books as debt, but that debt will never be repaid and instead will be monetized by the government's purchase of its own bonds. Indeed, as MMT notes, the debt is already treated as money when it is in private hands.

As anyone who goes grocery shopping, puts gasoline in his car and pays electricity, insurance and tax bills knows, inflation is already roaring and making a joke of the official price data.

The single compelling reason to raise taxes on the rich is to diminish income inequality a little after it has been increased so much by the federal government's policy of inflating asset prices during the economic depression caused by the epidemic -- a policy of directing far more money to the financial markets and thus to the ownership class, people who own stocks and bonds, than to the laboring class, tens of millions of whose members lost their jobs because of government policy and crashed into poverty.

But this effort to reduce wealth inequality should be undertaken at the federal level, not by state government in Connecticut -- at least not yet. That's because Connecticut is already a high-tax state whose economy has been weak for many years, and raising state taxes would disadvantage Connecticut even more relative to other states.

Money will go where it is treated best, and until the dislocations of recent months that drove thousands of people out of the New York City area, Connecticut was losing population relative to the rest of the country, losing mainly the prosperous people who pay taxes.

Connecticut's effort to reduce wealth inequality should concentrate on reducing the poverty the state manufactures with its welfare and education policies.

xxx

Many people in Connecticut, including some state legislators, argue that medical care is or should be a human right and that, as a result, state government should extend Medicaid insurance to the tens of thousands of people living in the state illegally. The cost is estimated at nearly $200 million per year.

These people are not entirely without medical care. They can pay for it themselves or present themselves at hospital emergency rooms when they are sick or injured and hospitals must treat them for free if they are indigent.

Of course, such medical care falls far short of comprehensive. But if comprehensive medical care is a human right, is living in Connecticut a human right too? If so, most people in Central America might insist on living in the state. Extending Medicaid to immigration lawbreakers would be a powerful incentive for more lawbreaking, which is already rampant.

So in addressing the Medicaid extension issue, Connecticut can't help addressing the illegal immigration issue as well. Extending Medicaid will be, in effect, more nullification of federal immigration law, just as the state's pending legalization and commercialization of marijuana, sensible as such policies may seem, will be more nullification of federal drug law.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn