Mass. bill would mandate solar panels on new buildings

Installing solar panels on a house

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Massachusetts legislators have filed two bills that would require rooftop solar panels to be installed on new residential and commercial buildings.

The Solar Neighborhoods Act, filed by Rep. Mike Connolly (D.-Cambridge) and Rep. Jack Lewis (D.-Framingham), would require solar panels to be installed on the roofs of newly built homes, apartments, and office buildings. The bill allows for exemptions if a roof is too shaded for solar panels to be effective. A similar bill was filed by Sen. Jamie Eldridge (D.-Acton).

Connolly said the legislation is a necessary step in a transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

“Combating climate change will require robust solutions, and the mobilization of all of our resources, so I’m excited to reintroduce this legislation and continue working with my colleagues and stakeholders in taking this bold step forward,” he said.

A 2018 report from the Environment America Research & Policy Center found that requiring rooftop solar panels on all new homes built in Massachusetts would add more than 2,300 megawatts of solar capacity by 2045, nearly doubling the solar capacity that has been installed in Massachusetts to date.

The amount of installed solar-energy capacity has increased more than 70-fold in Massachusetts during the past decade, according to Environment America. In recent years, the growth of solar has been held back by arbitrary caps on the state’s most important solar energy policy, net metering, as well as uncertainty over solar incentive programs, according to Ben Hellerstein, state director for Environment Massachusetts.

Massachusetts could generate up to 47 percent of its electricity from rooftop solar panels, according to a 2016 study from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

During the last legislative session, the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilties and Energy gave a favorable report to similar legislation, but it didn’t advance to a vote on the floor of either chamber.

“Every day, a clean, renewable, limitless source of energy is shining down on the roofs of our homes and businesses,” Hellerstein said. “With this bill, we can tap into our potential for rooftop solar energy and take a big step toward a healthier, safer future.

'The Old England of New England'

The Wayside, in Concord, Mass., home in turn to the Alcott family, novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne and writer and publisher “Margaret Sidney’’ (a nom de plume )— real name was Harriett Lothrop.

—- Photo by Dadero

“I perceive that I am neither a planter of the backwoods, pioneer, nor settler there, but an inhabitant of the Mind, and given to friendship and ideas. The ancient society, the Old England of New England, Massachusetts for me.”

— Amos Bronson Alcott (1799-1888), an American teacher, writer, philosopher and reformer, father of writer Louisa May Alcott (Little Women, etc.) and member of the famous literary community of Concord, Mass.

Grace Kelly: Book author touts easy, healing walks

Marjorie Hollman Turner

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Thirty years ago Marjorie Turner Hollman found her right side paralyzed after brain surgery. She was unable to drive in the seven years of recovery that followed and turned to writing and taking walks down her dead-end road for solace.

When she met her second husband, an avid outdoorsman, she slowly began to move beyond handicap-accessible walks to what she now calls “easy walks.”

“If I had not found myself on a hospital bed paralyzed after brain surgery, I wouldn’t be doing easy walks,” said Turner Hollman, who lives in Bellingham, Mass., which is just over the Rhode Island border near Cumberland. “I have healed to the extent that I am able to walk with support, meaning hiking poles, and I’m very selective of where I choose to walk. I’m not your Appalachian Mountain Club material.”

Over the years, Turner Hollman sought out more of these easy walks, which she defines as “walks that don’t have too many roots, don’t have too many rocks, are relatively level … with something of interest along the way.”

In essence, walks that children, people with mobility issues, and those new to the outdoors can enjoy. Anyone, really.

And as Turner Hollman started her easy walks, she began to chronicle them — and the natural world around her — first for her local newspaper and later on her blog. Then, the questions came pouring in.

“I started having people find my Web site and they kept asking the question, Where’s Joe’s Rock?’” Turner Hollman said. “Well, it’s in Wrentham [Mass.] on Route 121 right near the Cumberland line, and after about the 500th time somebody came to that article, I said, ‘Well I think there’s a need here.’”

Turner Hollman wrote her first book, Easy Walks in Massachusetts, in 2014 to provide a one-stop-shop resource for anyone else in the state looking for easy walks. But the process was far from easy, since a lot of the walks she enjoyed weren’t in any guidebooks.

“At the time, they didn’t have any guides for outdoor things here. We’re not the Cape, we’re not in the White Mountains, we don’t have that cache,” she said. “Today, a lot of town offices have put up maps of their conservation areas, but when I started writing these in 2013, there were next to none. I visited town halls and said, ‘Help me!’ or called and said, ‘Do you have properties that kind of fit this?’ I did a lot of legwork.”

Since then, she’s written another three “easy walks” books, one of which was done in conjunction with the Ten Mile River Watershed Council, an organization with offices in Rumford, R.I., and Attleboro, Mass. This two-state watershed contains one of her favorite easy walks, Hunts Mills, which has a man-made dam and waterfall and trails that loop through the woods.

“It’s stunning and incredibly accessible,” Turner Hollman said. “You can even just sit in your car and watch the falls … it’s this hidden away little spot. It’s just a gem.”

In her most recent book, Finding Easy Walks Wherever You Are, Turner Hollman takes the principles of seeking out and enjoying easy walks to a broader level, providing tips and perspectives that anyone can use to seek out a special place to walk anywhere.

“There are plenty of places, but people don’t know how to find them because a lot of the time they’re off the beaten track,” she said. “I encourage people to consider places like, for example, your local cemetery to visit respectfully, understanding its first purpose is not a walking place … but they’re wonderful places to walk and often have paved roadways through them.

“So that’s a lot of what I talk about in finding easy walks wherever you are. It’s providing ideas that people maybe don’t think about.”

The book is also a culmination of Turner Hollman’s personal experience and belief that anyone, regardless of ability, can go on a walk.

“What I’ve learned in sharing Easy Walks is that many people can enjoy these outings, regardless of ability,” she wrote in a blog post from 2015. “Rather than my disability creating a barrier, I’ve found that working with, in spite of, and because of my disability has enriched my life, and the lives of many others. … These days I’m even more determined to search out and point others to places they can enjoy together.”

Grace Kelly is a journalist with ecoRI News.

JFK speech on N.E. economic problems in 1954; region’s industries very different now!

At the now long-gone Fore River Shipyard, in Quincy, Mass., about the time of this Kennedy speech

Text of remarks by Sen. John F. Kennedy on “The Economic Problems of New England’’ June 3, 1954, in the U.S. Senate

Mr. President: Since my discussion before the Senate exactly one year ago of the economic problems of New England and their alleviation, considerable progress has been made in meeting those problems, including the organization of the twelve New England Senators in response to the call of the senior Senator from Massachusetts (Mr. Saltonstall) and myself. These 12 Senators, regardless of party, have been working faithfully on behalf of New England's needs.

But more effective action by the Executive Branch is necessary. The disappointing failures to meet many of New England's economic needs, too easily overlooked in our drive for psychological confidence, cannot be justified by recent trends. In these twelve months since my Senate speeches, unemployment in New England – which is above the national average – has increased by more than 125%* until insured unemployment has reached approximately 180,000. Manufacturing** has declined in all six New England states for a total loss of 133,000 jobs, highlighted by the 48,000 job decline in the textile industry which is now approximately 60% of its February 1951 strength. Our leather, shoe, rubber, apparel, and other non-durable goods industries have also declined; as have the more publicized machinery, metal and other durable goods industries. New England's steel fabricating mills operated in the first quarter of 1954 at 62% of capacity, 30% less than a year ago. Reports from The New England Council and the Boston Federal Reserve Bank indicate that declining defense orders will increase the difficulties of New England's electronic, aircraft, shipbuilding, and equipment manufacturers.

The battle against recession is now more nationwide in scope than it was one year ago, and it involves many legislative issues to be discussed subsequently on this floor, including taxation, credit and interest, public works, housing, farm income, and world trade, in addition to the items which I shall mention; but permit me to outline those steps which the administration should take promptly in order to help restore prosperity in New England and other similarly situated areas, and in order to complement the effectiveness of the New England members of Congress.

1. Restore bid-matching to Defense Manpower Policy No. 4, the program for channeling defense contracts to labor surplus areas. This program, both widely hailed and condemned when announced six months ago, has had only a negligible effect because of its elimination of the bid-matching features under which New England labor surplus areas had previously obtained $14 million in defense contracts. During the new policy's first full quarter of operation***, not a single contract went to a New England surplus labor area as a result of this preference, and only two "distressed areas" in the rest of the country received contracts totaling only $163,159. Moreover, only two of New England's labor surplus areas received any defense contracts at all in the first quarter; and New England's share of all defense contracts declined instead of increasing.

2. Expand the application of the administration's new policy of tax amortization certificates of necessity for industries in labor surplus areas. The delay in initiating this policy, the restrictions placed upon it, and the fact that it provided only an extra percentage for that declining number of industries already eligible for emergency amortization, have made this program of little value; and as of April 15, only two certificates under this policy had been awarded to one New England community, covering a capital investment of only $250,843. Only ten such certificates were awarded throughout the entire country. During this same period under the regular tax amortization program, the number and value of certificates of necessity awarded to all firms in all New England states continued to lag behind New England's proportionate share and defense contribution.

3. Revitalize and broaden the authority of the Small Business Administration. The establishment of this agency to strengthen the economy by aiding small business was of particular interest in New England, which has a higher proportion of small business than any other region in the United States, and where the rate of business failures is higher this year than last. But as a result of legislative ceilings and administrative delays, the Small Business Administration as of May 13 had approved in its 7½ months of operation only six loans, for a total of only $204,000 in all six New England states. Indeed, as of April 30, SBA had disbursed less than $1.2 million on thirty-seven loans throughout the nation (as compared with administrative expenses on March 30 totaling nearly $2.4 million).

4. Eliminate discrimination and confusion in New England transportation rates. I have previously pointed out examples of such discrimination and confusion in rail, truck, and ocean shipping rates, and this subject is now under review by the New England Senators Conference. ICC decisions during the past twelve months have intensified this situation. Division 2 of the Commission recently denied to New England, and its railroads and ports, the opportunity to enjoy rates on iron ore shipped by rail to the interior steel-producing areas, comparable to the rates enjoyed by the Ports of Philadelphia and Baltimore. In January, a Commission decision denied adequate service in inter-coastal shipping between the Port of Boston and the West Coast. Other recent ICC decisions affecting shipments of New England goods by truck have continued this discrimination.

5. Plug tax loopholes which contribute to improper industrial migration. The House Ways and Means Committee, in its deliberation on the tax revision bill, originally decided to plug one of the most flagrant of such loopholes by removing the immunity from "industrial development" bonds issued by states and municipalities in order to build tax-free factories as a lure to industry; but, the Committee reversed this decision and instead voted to deny the use of rentals on such factories as business deductions. The Senate Finance Committee has now voted to eliminate even this substitute, which is ineffective whenever such factories are given or cheaply sold to the migrant industry. I am hopeful that the Senate Committee or the Senate, with the administration's backing, will reinstate at least this modified version before the bill is finally passed, and eliminate this unjustifiable abuse of public credit.

6. Request legislative and administrative action to correct substandard wage competition. It is my hope that the President will reexamine his decision not to seek an increase in the minimum wage or to extend its coverage at this time; that his administration will ask Congress to modify or repeal the Fulbright Amendment to the Walsh-Healey Act which has stymied effective application of adequate nationwide minima on defense contracts; and that the Department of Justice will act more vigorously in pending litigation under the Fulbright Amendment which has delayed the adoption of realistic wage standards for the textile industry. I am particularly hopeful that this year's budget for Labor's Wage and Hour Enforcement Division will rectify last year's error, when this budget was cut 27% below the previous appropriation, thus making it possible to inspect only one out of twenty-two establishments covered by the law, requiring the complete elimination of eight southern regional offices, and making possible the review of wages in Puerto Rico only once in every seven years for each industry.

7. Initiate a program to revive the shipbuilding industry. Such a program, much discussed but not as yet forthcoming, is of particular interest in New England and other areas dependent upon this vital industry. An essential part of such a program would be to make more effective those defense manpower policies applicable to the shipbuilding industry, inasmuch as the third Forrestal-type aircraft carrier was awarded to a shipyard with increasing employment and substantial naval projects, instead of the Fore River shipyard at Quincy, Massachusetts, where employment had already dropped by more than 25%, and where seven out of its ten shipbuilding ways will be idle by this fall.

8. Support the Saltonstall-Kennedy Bill to aid research and market development in the fishing industry. The active opposition by the Department of Agriculture with the approval of the Bureau of the Budget to this measure, which seeks only to allocate to our fishing industry its fair share of tariff receipts, has handicapped its passage without restrictive amendments. I am hopeful that the administration will reverse this position, and support this bill which is of great importance to New England's hundred million dollar fishing industry.

9. Seek more effective social insurance against the ills of unemployment and forced retirement. In order to maintain community purchasing power and individual living standards, New England requires improvements in the existing Social Security Program, which improvements are only partly contained in the recommendations of the President, particularly with respect to our disabled citizens. It is especially important to strengthen our unemployment compensation program by extending coverage, providing federal reinsurance for states with low reserves and by establishing through congressional action – not, as the President asked in vain, through individual state action – minimum standards for unemployment insurance benefits and their duration. As a first step, the administration should withdraw its support, even though it is substantially modified, of the House-passed Reed Bill which would undermine the basic strength of our jobless insurance program. The bill introduced today by myself and several other Senators would far more adequately meet the needs of New England and the nation.

10. Accord equal treatment to New England and all other areas in federal programs, including those for resource development. Last year, the original budget request for the New England-New York Inter-Agency Survey of Water Resources was set at $1,200,000 in order that that survey might be completed by the end of fiscal 1954, inasmuch as its original termination was fiscal 1952. The revised budget, however, when finally enacted into law, cut this figure exactly in half, thus delaying completion by at least another year. This stepchild treatment of New England by a Federal Government which has provided direct grants for the establishment of power facilities in other areas already enjoying cheaper power rates, should be reversed by the present administration, for the recommendations of the Budget Bureau and Army Engineers are generally conclusive on such items. New England's share of the Army Civil Functions Appropriation Bill is less than that received by some two dozen individual states, practically all of whom contribute less in tax revenues than Massachusetts alone; and therefore the request for adequate funds with which to survey our potential resource development is not excessive.

It is my hope, Mr. President, that the administration will take prompt action on the 10-point program which I have outlined above, and that we in Congress – with the assistance of the twelve New England Senators who have indicated their active concern for these problems – will be able to follow through on legislation to restore economic strength and expand employment in New England and all other parts of the country.

* As measured by the average weekly insured unemployment under state programs, May 1953-May 1954.

** March 1953 to March 1954, latest available Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys.

*** Defense Department release based upon contracts of $25,000 value or more, $10,000 for Navy.

William Morgan: Cutting-edge artisanship at a family homestead in rural Maine

Hannah and Chris Blackburn outside their cutting-tool-making workshop, in New Gloucester, Maine

— All photos by William Morgan

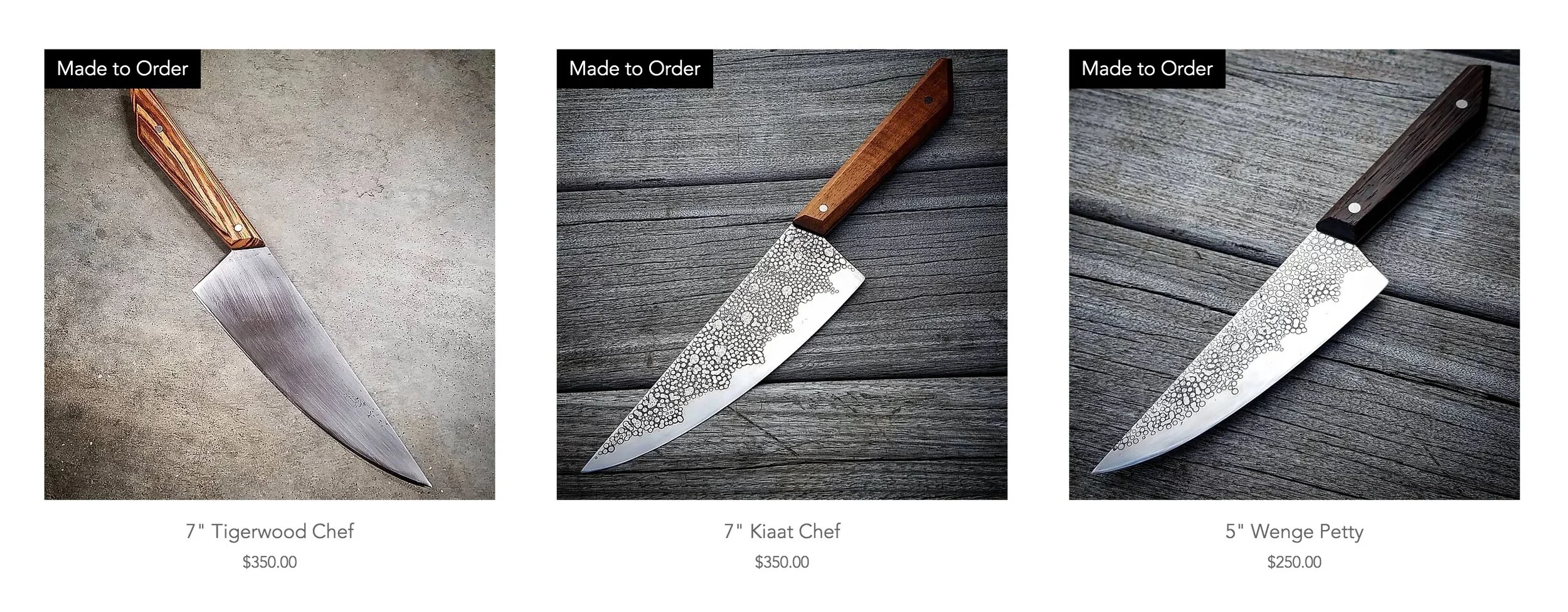

My wife recently bought herself a kitchen knife. Carolyn has dozen of blades suited to all kinds of cooking and pottery, including the stained and pitted Sabatier that she found at a yard sale a quarter century ago. But this piece of cutlery from Maine was different. It cost far more than she could afford, but it was so beautiful, such a work of art, that she could not afford not to buy it.

Really good tools should have stories. Carolyn's new extension of her hand was made of recycled materials: wood from Boston park benches and metal from old saw blades (the recycled 19th Century carbon steel is much stronger than anything available now, and its hard-earned patina is beautiful). That these artisanal tools are sold only at two stores –Strata in Portland and Stock in Providence – reinforces the fact that they’re the products of true craftspeople.

The Blackburns use the steel from old saw blades to make their artisanal knives and other cutting tools.

Full Circle CraftWorks is the commercial face of two art school graduates, trying to build a business while raising a family on a 22-acre homestead in New Gloucester, Maine, a quiet upland town close to, but very different from Freeport, best known for L.L. Bean and other stores, many of them outlets of national chains.

Hannah and Chris Blackburn met as undergraduates at the Rhode Island School of Design, where they were furniture and sculpture majors, respectively. They mastered such skills as welding and sculpting, along with traditional woodworking. Maine native Hannah grew up in nearby Yarmouth, while Chris hails from suburban Washington, D.C. After graduation, the couple remained in the Rhode Island capital.

Providence is a good place for young artists, with lots of colleagues and abundant studio space, but its urban setting was not what the Blackburns wanted for their growing family of two girls and a boy. "The goal was to carve out a simpler life," Chris says, "more directly connected to the environment, the seasons, and all things that sustain our life." One grace note is that the quest for a life based on the land while producing beautiful utilitarian objects is not so different from that espoused by the Shakers, whose last active colony, Sabbathday Lake, is close by in New Gloucester.

Carolyn Morgan and Chris Blackburn in First Circle’s workshop

Their 1985 log cabin on a dirt road came with a two-stall horse barn, which they converted into a workshop, complete with enough of the tools needed to fashion the exotic woods from around the world and the redundant saw blades from barns and country auctions into their handsome tools.

The future success of Full Circle would let these artists live from their sales, but right now their main goal is raising a family on what they hope will become a thoroughly sustainable operation. As a result, much of their life is focused on the rigorous, endless day-to-day and seasonal activities of a working farm.

Just a mention of the Full Circle’s livestock – three goats, seven ducks and a score of chickens, guarded by a dog to guard against coyotes, bears and other predators – ought to be reminder enough that self-sufficient farm life is far from simple or romantic. In the spring, piglets, turkeys and more laying hens augment the permanent stock. Bow hunting deer in the autumn provides much of the family's meat.

There is a small greenhouse, a fruit orchard and gardens for a variety of crops that will grow in Maine. The house and workshop are heated solely with firewood harvested on the property, where sugar maples are tapped to make syrup. Through all the seasons the three young children, aged nine, seven and five, help with chores, from planting and harvesting, to stacking firewood and feeding the animals.

Demanding as farm life is, it does not preclude the family's engagement with the local community. The Backburns host an annual July pig roast that draws scores of friends and neighbors. Their two daughters act in plays put on by the local youth theater, where Chris is a set designer and member of the build crew. The Blackburn children go to a Montessori-type charter school, even as important life lessons come from being part of the agricultural enterprise that helps sustain them.

A hand saw once used in Massachusetts apple orchard or a large circular blade from a Vermont sawmill, along with wood repurposed from repairing their cabin's porch or from an Indonesian rainforest, are transformed into utilitarian but strikingly handsome tools. Whether Hannah and Chris are fashioning a cleaver or a chopping blade, their handmade tools express a worldview that respects the land and the dignity of hard work.

When Chris saw Carolyn's knife again, he said, "It's getting good use; I can tell by the patina. I much prefer that. Some people see them as precious, but tools need to be used."

William Morgan, based in Providence, is an architecture writer, essayist and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, in New Gloucester. It was founded in 1783 by the United Society of True Believers at what was then called Thompson's Pond Plantation. Today, the village is the last of some over two-dozen religious societies, stretching from Maine to Florida, to be operated by the Shakers themselves. It comprises 18 buildings on 1,800 acres.

Tim Faulkner: What next for Transportation Climate Initiative?

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The regional collaboration known as the Transportation & Climate Initiative (TCI) will be operating, at least initially, with a smaller cast than expected.

Governors from Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut, as well the District of Columbia’s mayor, signed an agreement Dec. 21 to launch an effort to address the climate crisis. This cap-and-invest system is designed to reduce climate emissions by raising money from the wholesale distribution of gasoline and diesel fuel and investing the proceeds in electric-vehicle infrastructure and other initiatives that make up the so-called “green transportation economy.”

TCI is composed of 13 East Coast states and the District of Columbia, but only the three states and the nation’s capital signed the recent memorandum of understanding to establish the revenue-generating system. Most other TCI member states had previously signed a separate letter expressing support for the program. Maine and New Hampshire didn’t sign on to that earlier letter. All TCI members can adopt the cap-and-invest program at any time.

During an online press call, no explanation was offered as to why the other states aren’t joining the pact. Representatives from the three states and the District of Columbia instead described how the anticipated reduction in climate emissions, along with the economic growth they expect, will entice states to eventually participate.

“This is a strong group moving forward in a committed way,” said Kathleen Theoharides, secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. “And we believe the future is bright and that if you build it they will come.”

Katie Scharf Dykes, commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection, predicted that TCI will increase state participation, as did another cap-and-invest program that generates revenue from power-plant emissions, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

“I’m confident that we will see more jurisdictions joining us,” Scharf Dykes said.

If local approvals are met, TCI is scheduled to launch in 2022 with a one-year trial reporting period that will track emissions for each state and the District of Columbia. Fossil-fuel distributors won’t have to buy the pollution allowances until 2023, when they are required for exceeding a monthly emission limit, or cap. The limit is reduced each year until 2032, when it will be 30 percent lower than the initial cap.

During the recent press call, representatives from the three states and District of Columbia touted the benefits of investing some $3.2 billion over nine years in electric buses, electric-vehicle charging infrastructure, and new bicycle lanes, walking trails, and sidewalks.

Some $3.2 billion will be invested in low-carbon transit projects in four regions over nine years. (TCI)

“Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and D.C. are committing to bold action to achieve our ambitious emission-reduction targets while positioning the jurisdictions and the region to grow our clean transportation economy,” Theoharides said.

The auction of the allowances is expected to raise about $300 million annually. Rhode Island anticipates receiving about $20 million a year. As part of the program, at least 35 percent of the proceeds must be invested in environmental-justice communities. Spending in these frontline communities is expected to create jobs, reduce air pollution, and improve public health.

If fuel distributors pass the cost on to consumers, the expense is expected to add between 5 and 9 cents to a gallon of fuel.

The program’s requirement for equity investment is intended to address the regressive nature of the higher fuel costs by investing in communities suffering from excessive air pollution. Statewide equity advisory boards comprised mostly of members from these communities will recommend where and how the TCI funding is spent.

“Most importantly, (TCI) will provide much-needed relief for the urban communities who suffer lifelong health problems as a result of dirty air,” Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo wrote in a prepared statement.

The program is expected to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions from the transportation sector by some 26 percent over nine years. Transportation accounts for 42 percent of all emissions among the signors, the largest source of emissions in those areas.

The announcement comes a year after TCI was expected to launch. TCI representatives blamed the delay on the heath crisis and an unfriendly White House administration. Public perception was also a likely cause for delay. Opposition to TCI from conservative news outlets and radio talk-show hosts has persisted.

Rhode Island acknowledged at a meeting in 2019 that TCI will take more than a government directive to succeed.

“If we’re going to win hearts and minds, it’s not just people at the Statehouse,” said Carol Grant, then director of the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources. “We have to kind of win people over generally to the importance of this.”

Back then, environmental groups criticized TCI for not advancing stronger reductions in emissions. Reaction to the recent announcement from the same environmental community has been positive. Support for the TCI program has been expressed by Save The Bay, Acadia Center, and the Northeast Clean Energy Council.

A new president committed to taking on climate change improved the prospects for enacting the TCI program, according to coalition members.

“With a change in administration, policies are going to be a lot more stable,” said Terrence Gray, deputy director for environmental protection at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Janet Coit, DEM’s executive director and the state’s representative during the online announcement, noted that states with Republican and Democratic governors are TCI members.

“After so much divisiveness, it’s really great to see bipartisan regional effort leading on climate change,” Coit said.

The public response to the program will likely determine the willingness of other states to join. A recent poll conducted by Yale University and George Mason University among voters in TCI states and the District of Columbia found that 41 percent said they strongly support participation in the initiative. Another 31 percent said they would somewhat support participation. Rhode Island had the highest support at 61 percent. Maine was the lowest at 56 percent. Politically, 84 percent of Democrats favored joining TCI, while 49 percent of Republican favored joining the initiative.

Public perception starts with messaging. The revenue mechanism is often referred to by opponents as a “gas tax” or fee paid by consumers. But it has several distinctions, according to the renewable-energy advocacy group Acadia Center.

First, some fuel-distribution companies may choose to internalize part or all of the allowance costs to gain a competitive advantage rather than pass it on to gas-station customers. And since TCI is based on the carbon content of a fuel, suppliers will be able to sell fuels with lower carbon contents and pay less in carbon pollution fees, according to Acadia Center.

“This program is about delivering benefits to consumers with a transition in fuels and mobility options over time,” said Hank Webster, staff attorney and Rhode Island director for Acadia Center.

TCI will have a minimal impact, if any, on fuel prices, Webster said, because the program is designed to keep that impact at or below 5 cents if regional fuel suppliers choose to pass the costs on to their customers.

“To put that in context, you can save 5 cents per gallon at some stations by using their frequent customer program, or 10 cents per gallon by setting up a direct debit from your checking account,” he said.

Rhode Island and Connecticut require legislative approval to launch the TCI program. Massachusetts can advance the program through its executive office.

Raimondo is expected to launch the legislative process this spring, with public input beginning in January.

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI News.

— Photo by Felix Kramer

Past time to go big

Block Island Wind Farm

Old Higgins Farm Windmill, in Brewster, Mass., on Cape Cod. It was built in 1795 to grind grain. Many New England towns had windmills.

“By partnering with our neighbor states with which we share tightly connected economies and transportation systems, we can make a more significant impact on climate change while creating jobs and growing the economy as a result.’’

-- Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker

Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island and the District of Columbia have signed a pact to tax the carbon in vehicle fuels sold within their borders and use the revenues from the higher gasoline prices to cut transportation carbon-dioxide emissions 26 percent by 2032. Gasoline taxes would rise perhaps 5 to 9 cents in the first year of the program -- 2022.

Of course, this move, whose most important leader right now is Massachusetts’s estimable Republican governor, Charlie Baker, can only be a start, oasbut as the signs of global warming multiply, other East Coast states are expected to soon join what’s called the Transportation Climate Initiative.

The three states account for 73 percent of total emissions in New England, 76 percent of vehicles, and 70 to 80 percent of the region’s gross domestic product.

The money would go into such things as expanding and otherwise improving mass transit (which especially helps poorer people), increasing the number of charging stations for electric vehicles, consumer rebates for electric and low-emission vehicles and making transportation infrastructure more resilient against the effects of global warming, especially, I suppose, along the sea and rivers, where storms would do the most damage.]

Of course, some people will complain, especially those driving SUVs, but big weather disasters will tend to dilute the complaints over time. Getting off fossil fuels will make New England more prosperous and healthier over the next decade. For that matter, I predict that most U.S. vehicles will be electric by 2030.

Eventually, reactionary politics will have to be overcome and the entire nation adopt something like the Transportation Climate Initiative.

Good news for GE and New England

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Here’s another example of how offshore wind power can be an economic boon for New England:

Vineyard Wind LLC has picked Boston-based General Electric to provide the turbines for its project south of Martha’s Vineyard – in what will be the first large-scale offshore wind farm in the United States. European nations are far ahead of us!

The wind-farm developer, a joint venture owned by Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, had originally planned to put up turbines made by the Danish-Japanese venture MHI Vestas (soon to be entirely Danish).

But permitting delays led Vineyard Wind to change the wind farm’s layout and equipment. So there will be 62 GE turbines instead of the 84 planned with MHI Vestas. But those General Electric turbines are the world’s most powerful. It’s nice to think that a Massachusetts company will provide this gear for this massive New England project.

And the news may suggest a brighter future for GE, which has faced hard times the past few years.

Hint this link for more information.

But they took only cash

The Red Coach Grill was a very popular New England restaurant chain in the ‘60s. Look at the prices!

Charlotte Huff: In COVID crisis, 'unattended moral injury' to health-care workers

St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester

For Christina Nester, the pandemic lull in Massachusetts lasted about three months through summer into early fall. In late June, St. Vincent Hospital had resumed elective surgeries, and the unit the 48-year-old nurse works on switched back from taking care of only COVID-19 patients to its pre-pandemic roster of patients recovering from gallbladder operations, mastectomies and other surgeries.

That is, until October, when patients with coronavirus infections began to reappear on the unit and, with them, the fear of many more to come. “It’s paralyzing, I’m not going to lie,” said Nester, who’s worked at the Worcester hospital for nearly two decades. “My little clan of nurses that I work with, we panicked when it started to uptick here.”

Adding to that stress is that nurses are caught betwixt caring for the bedside needs of their patients and implementing policies set by others, such as physician-ordered treatment plans and strict hospital rules to ward off the coronavirus. The push-pull of those forces, amid a fight against a deadly disease, is straining this vital backbone of health providers nationwide, and that could accumulate to unsustainable levels if the virus’s surge is not contained this winter, advocates and researchers warn.

Nurses spend the most sustained time with a patient of any clinician, and these days patients are often very fearful and isolated, said Cynda Rushton, a registered nurse and bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore.

“They have become, in some ways, a kind of emotional surrogate for family members who can’t be there, to support and advise and offer a human touch,” Rushton said. “They have witnessed incredible amounts of suffering and death. That, I think, also weighs really heavily on nurses.”

A study published this fall in the journal General Hospital Psychiatry found that 64 percent of clinicians working as nurses, nurse practitioners or physician assistants at a New York City hospital screened positively for acute distress, 53 percent for depressive symptoms and 40 percent for anxiety — all higher rates than found among physicians screened.

Researchers are concerned that nurses working in a rapidly changing crisis like the pandemic — with problems ranging from staff shortages that curtail their time with patients to enforcing visitation policies that upset families — can develop a psychological response called “moral injury.” That injury occurs, they say, when nurses feel stymied by their inability to provide the level of care they believe patients require.

Dr. Wendy Dean, co-founder of Moral Injury of Healthcare, a nonprofit organization based in Carlisle, Pa., said, “Probably the biggest driver of burnout is unrecognized unattended moral injury.”

In parts of the country over the summer, nurses got some mental-health respite when cases declined, Dean said.

“Not enough to really process it all,” she said. “I think that’s a process that will take several years. And it’s probably going to be extended because the pandemic itself is extended.”

Before the pandemic hit her Massachusetts hospital “like a forest fire” in March, Nester had rarely seen a patient die, other than someone in the final days of a disease like cancer.

Suddenly she was involved with frequent transfers of patients to the intensive-care unit when they couldn’t breathe. She recounts stories, imprinted on her memory: The woman in her 80s who didn’t even seem ill on the day she was hospitalized, who Nester helped transport to the morgue less than a week later. The husband and wife who were sick in the intensive care unit, while the adult daughter fought the virus on Nester’s unit.

“Then both parents died, and the daughter died,” Nester said. “There’s not really words for it.”

During these gut-wrenching shifts, nurses can sometimes become separated from their emotional support system — one another, said Rushton, who has written a book about preventing moral injury among health- care providers. To better handle the influx, some nurses who typically work in noncritical care areas have been moved to care for seriously ill patients. That forces them to not only adjust to a new type of nursing, but also disrupts an often-well-honed working rhythm and camaraderie with their regular nursing co-workers, she said.

At St. Vincent Hospital, the nurses on Nester’s unit were told one March day that the primarily post-surgical unit was being converted to a COVID unit. Nester tried to squelch fears for her own safety while comforting her COVID-19 patients, who were often elderly, terrified and sometimes hard of hearing, making it difficult to communicate through layers of masks.

“You’re trying to yell through all of these barriers and try to show them with your eyes that you’re here and you’re not going to leave them and will take care of them,” she said. “But yet you’re panicking inside completely that you’re going to get this disease and you’re going to be the one in the bed or a family member that you love, take it home to them.”

When asked if hospital leaders had seen signs of strain among the nursing staff or were concerned about their resilience headed into the winter months, a St. Vincent spokesperson wrote in a brief statement that during the pandemic “we have prioritized the safety and well-being of our staff, and we remain focused on that.”

Nationally, the viral risk to clinicians has been well documented. From March 1 through May 31, 6 percent of adults hospitalized were health-care workers, one-third of them in nursing-related occupations, according to data published last month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As cases mount in the winter months, moral injury researcher Dean said, “nurses are going to do the calculation and say, ‘This risk isn’t worth it.’”

Juliano Innocenti, a traveling nurse working in the San Francisco area, decided to take off for a few months and will focus on wrapping up his nurse practitioner degree instead. Since April, he’s been seeing a therapist “to navigate my powerlessness in all of this.”

Innocenti, 41, has not been on the front lines in a hospital battling COVID-19, but he still feels the stress because he has been treating the public at an outpatient dialysis clinic and a psychiatric hospital and seen administrative problems generated by the crisis. He pointed to issues such as inadequate personal protective equipment.

Innocenti said he was concerned about “the lack of planning and just blatant disregard for the basic safety of patients and staff.” Profit motives too often drive decisions, he suggested. “That’s what I’m taking a break from.”

Building Resiliency

As cases surge again, hospital leaders need to think bigger than employee-assistance programs to backstop their already depleted ranks of nurses, Dean said. Along with plenty of protective equipment, that includes helping them with everything from groceries to transportation, she said. Overstaff a bit, she suggested, so nurses can take a day off when they hit an emotional cliff.

The American Nurses Association, the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) and several other nursing groups have compiled online resources with links to mental health programs as well as tips for getting through each pandemic workday.

Kiersten Henry, an AACN board member and nurse practitioner in the intensive care unit at MedStar Montgomery Medical Center, in Olney, Md., said that the nurses and other clinicians there have started to gather for a quick huddle at the end of difficult shifts. Along with talking about what happened, they share several good things that also occurred that day.

“It doesn’t mean that you’re not taking it home with you,” Henry said, “but you’re actually verbally processing it to your peers.”

When cases reached their highest point of the spring in Massachusetts, Nester said there were some days she didn’t want to return.

“But you know that your friends are there,” she said. “And the only ones that really truly understand what’s going on are your co-workers. How can you leave them?”

Charlotte Huff is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

While there’s still snow

This long poem, by Whittier (1807-1892) a poet based in northeast Massachusetts, a Quaker and an abolitionist, once was required reading for kids.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Providence-based architectural writer and historian William Morgan’s latest – and beautifully illustrated -- book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter (Princeton Architectural Press), looks at 20 houses in various cold parts of the world, including Europe, Asia and North and South America.

A New Hampshire house and a Connecticut house are featured in the book.

As the press release notes:

“From the ski slopes of Utah to the frigid tundra of northwestern Russia, Snowbound celebrates contemporary design in cold climates with a focus on sustainability. Tailor-made for architects, designers, snowbirds, and aspiring second-home owners, this tour of twenty dwellings is equal parts escapist photo essay and practical sourcebook, with immersive photography, architectural plans, and location, climate, and building-systems data.’’

That some of these houses were put up in preposterously harsh and remote places adds to the entertainment.

But global warming rears its head. Mr. Morgan writes:

“Candidates for Snowbound in Canada, Australia, and Vermont had to be eliminated as recent winters came with less-than-usual snowfall. In the middle of the winter in the Southern Hemisphere, there was insufficient snow in the Andes, more than a thousand miles south of Buenos Aires, to photograph a house as it would have looked only less than a decade ago.’’

But what about summers at these buildings?

Eating fall fruit on way home

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When I was a kid and sometimes walked home from school instead of taking the slow bus ride in my small Massachusetts town, I’d often take a short cut through the woods.

At this time of the year most of the leaves had fallen; only the oaks had held onto many of their boringly brown leaves. So there was plenty of light as I walked between the bayberry and other shrubs. Deep in the woods you could find crabapples, smaller than the ones in orchards, which contrary to myth, you could eat. There were also some edible wild grapes left, amidst the enveloping breezy barrenness

A crabapple in the fall

— Photo by Alpsdake

‘The boozing, the anger’

"It’s {the Boston area} just a really interesting place to grow up. The sports teams, the colleges, the racial tension, the state workers, the boozing, the anger. All of that stuff. I don’t think I ever appreciated the amount of maniacs that live in Massachusetts until I left. When I lived here, I took it for granted that everyone was kind of funny and a bit of a character."

— Bill Burr (born 1968 in the Boston suburb of Canton, Mass.), standup comedian and actor

The name "Canton" comes from the erroneous early belief that Canton, China, was on the complete opposite side of the earth (antipodal). New England merchants in the 18th and 19th centuries had many lucrative commercial links with the Chinese port city of Canton (now called Guangzhou). Canton, Mass. was originally part of Stoughton.

Part of Great Blue Hill is in Canton, whose summit, at 635 feet, is the highest point in Greater Boston and Norfolk County and also the highest within 10 miles of the Atlantic coast south of central Maine.

Boston high schools sent lab kits for distance learning

— Photo by Zuzanna K. Filutowska

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“Mass Insight Education and Research has partnered with manufacturer miniPCR bio to deliver 225 individual lab kits to high schools across Boston. The ‘Science from Home: Lab Kits for Distance Learning’ program is being piloted in by Advanced Placement (AP) biology classes in eight Boston high schools this fall.

“The Mass Insight program is partially supported by the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (MLSC) and seeks to support AP biology students with the ability to complete lab assignments from home. The labs are designed to give students a safe, grade-level appropriate lab experience, and will allow students to investigate vital biological processes with minimal equipment.

“Leslie Prudhomme, Mass Insight’s senior content director for AP Sciences and a former AP biology teacher, has spearheaded the effort to get lab kits into students’ hands. ‘The kids are our top priority,’ Ms. Prudhomme said. ‘The question wasn’t are we going to be able to help them get the quality science education they need in the fall semester, it was how are we going to get this done?’’’

Lisa Prevost: European study finds wind turbines don't affect lobster harvest

European lobster

Via Energy News Network ( https://energynews.us/) and ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In New England, offshore wind developers and the fishing industry continue to grapple with questions over potential impacts on the region’s valuable fisheries.

A recent European study not only offers good news on that front, it also provides a template for how the two industries can work together.

Research conducted over a six-year period concluded that the 35 turbines that form the Westermost Rough offshore wind facility, about 5 miles off England’s Holderness coast, have had no discernible impact on the area’s highly productive lobster fishing grounds.

The overall catch rate for fishermen and the economic return from those lobsters remained steady from the study’s start in 2013, before the facility’s construction, to its conclusion last year, according to the lead researcher, Mike Roach, a fishery scientist for the Holderness Fishing Industry Group, which represents commercial fishermen in the port town of Bridlington, England.

“It was quite a boring result,” Roach said. “All my lines are flat.”

Ørsted, the Danish energy giant and developer of the offshore wind facility, contracted with Holderness’s research arm to carry out the study, as the group has its own research vessel. The collaborative approach, Roach said, has made the findings all the more credible to local fishermen, who were initially certain that the energy project would destroy the lobster stocks.

“We did the research the same way a fisherman would fish — the same gear types, same bait, deploying in the same way,” Roach said. “We were basically mirroring the commercial fishing method in the area. And that has allowed the fishermen to relate directly to the fieldwork.”

Hywel Roberts, a senior lead strategic specialist for Ørsted and a liaison with the researchers, called the collaboration “a leap of faith on both sides to join together and agree at the outset to live and die by the results.” He noted that the level of research also went well beyond what was required for government permitting.

Ørsted announced the study’s results last month in a press release, even as Roach is still in the process of getting the research approved for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

It’s no wonder the European-based wind developer was eager to share the news more widely, as the fishing industry has proven to be a powerful force in slowing the progress of offshore wind development off the Northeast coast, such as the Vineyard Wind 1 project.

Last year, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management announced it was pausing the approval process for Vineyard Wind 1, a joint venture between Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Avangrid, to be constructed off Martha’s Vineyard. The agency said it wanted to devote more study to the cumulative environmental effects of the many offshore wind projects lining up for approval.

In June, the agency issued a supplemental environmental impact statement that concluded that the cumulative impacts on fisheries could potentially be “major,” depending on various factors. The federal agency is considering requiring transit lanes between turbines to better accommodate fishing trawlers, a design change Vineyard Wind argues is unnecessary and could threaten the project’s viability.

The developer has proposed separating each turbine by a nautical mile. The transit lanes would require additional spacing.

A final report is expected in December.

The outcome of the Holderness study has “very important” implications for wind projects all over, Roberts said.

“The lobster fishery there is one of the most productive in Europe, and we were tasked with building a wind farm right in the middle of it,” Roberts said. “If it can work in this location, we think it can work in most places around the world.”

Ørsted even brought Roach and one of the Holderness fishermen to Massachusetts last year to spread the word to worried lobstermen about the minimal impact of Westermost Rough.

Roach said he’d like to think his findings “eased some concerns” in New England. However, he said he disagrees with Ørsted that the outcome in the North Sea is applicable to other areas of the world, where habitats and the ecology of the species could be very different.

“There are lessons to be learned and guided by, but I can’t say it’s directly transferable,” he said.

Lisa Prevost is a journalist with Energy News Network, an Institute of Nonprofit News (INN) member that has a content-sharing agreement with ecoRI News.

Janine Weisman: States can grow their economies AND cut emissions

How New England’s six states have done in reducing climate emissions and growing the economy, according to data from a recent World Resources Institute report.

— Janine Weisman/ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

All the New England states have cut their energy-related carbon emissions while growing their economies in the past two decades, according to a new analysis that offers proof that climate action can actually be a good return on investment.

For years, the narrative about low-carbon technologies such as wind and solar power was that their high costs and subsidies couldn’t compete with fossil fuels. But renewable-energy storage technologies have improved and dropped precipitously in price while jobs in this sector have been growing at a faster pace than overall employment. That has made low-carbon technologies competitive with conventional fossil fuels, which are heavily subsidized, and also good for the economy, according to the 66-page white paper released in July by the World Resources Institute (WRI).

“There’s a lot of myths that are out there about climate change and we wanted to debunk some of those myths,” said the paper’s co-author Joel Jaeger, a research associate in WRI’s Climate Program.

The rapid deployment of wind and solar power, a shift from coal to natural gas in the power sector, and progress in vehicle-emissions standards helped drive a 12 percent drop in U.S. carbon emissions from 2005 to 2018, during which the nation’s Gross domestic product (GDP) increased 25 percent, according to the organization’s research.

“This is not just a year here or there — this is sustained transformation of the world’s largest economy,” according to the report.

The Washington, D.C.-based global research nonprofit ranked 41 states and the District of Columbia that have decoupled their emissions from economic growth during the 12 years studied. The list covers states both large and small in all major geographical regions. Nine other states, however, saw their emissions grow over that period of time, though much slower than state GDP in most cases.

Rhode Island cut carbon emissions by 10 percent between 2005 and 2017 at the same time its GDP increased 1 percent, according to the report’s data.

Rhode Island ranked 37th, trailing the other five New England states. New Hampshire, which cut carbon emissions by 37 percent while growing its GDP 15 percent, led the region and ranked second in the nation after Maryland, according to the report.

Massachusetts ranked 12th nationwide with a 25 percent emissions decrease and a 26 percent increase in GDP. Connecticut in 16th place saw a 24 percent emissions decrease and a 0.5 percent increase in GDP.

“Rhode Island is in many ways one of the leaders on climate action, even though it doesn’t appear that way on this decoupling metric,” Jaeger said. He noted that the smallest state has the lowest per capita energy consumption.

“Decoupling is measuring progress,” he said. “Rhode Island, it’s actually harder for it to make progress because it was already on the leading edge of having lower emissions.”

Rhode Island is among the 25 states that joined the U.S. Climate Alliance to uphold the Paris Agreement goals of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 26 percent to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. Participating states have grown their GDP per capita twice as fast and have reduced their emissions per capita faster than the rest of the country, according to the alliance’s 2019 annual report. Every New England state except New Hampshire is an alliance member.

If the WRI analysis had studied the decade from 2004 to 2014, Rhode Island would have been in the top 10, said Kenneth Payne, an energy and regional planning policy expert who served as head of the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources from 2010 to 2011.

In 2004, the General Assembly enacted a Renewable Energy Standard (RES) initially set to achieve 16 percent renewable energy by 2019 and later updated in 2016 with a statewide target of 38.5 percent renewable energy by 2035. Then, in 2014, the Resilient Rhode Island Act set an aspirational goal of reducing the state’s climate emissions by 45 percent by 2035.

But the political mood has changed along with federal support, according to Payne.

“Maybe I would describe it as, ’Well we’ve done enough for now. Let’s see how it works,’” he said. “And that’s putting it generously.”

With its less carbon-intensive service economy and low manufacturing output, Rhode Island already has low emissions per capita, making it challenging to continue achieving significant reductions, according to University of Rhode Island assistant professor in environmental and natural resource economics Simona Trandafir. Other states with energy-intensive heavy industry have higher baseline emissions and significantly more decarbonization opportunities, she noted.

“Those states have begun to take the lowest hanging fruit and they’re making huge emissions reductions because they switched from coal to natural gas, which we’ve been free of coal for several years,” Trandafir said. “For us it’s really hard right now, because we’re already the best.”

There are, however, two significant areas where Rhode Island could improve when it comes to reducing climate emissions. The transportation sector accounts for about 40 percent of the state’s greenhouse-gas emissions. Heating homes and businesses generates about 30 percent of Rhode Island's carbon emissions. Getting individual motorists out of their vehicles by improving public transit and switching from high-polluting oil- and natural gas-fired furnaces and hot-water systems to heat pumps and carbon-neutral replacement fuels would go a long way to further curbing the state’s climate-changing emissions.

WRI cited Rhode Island and Massachusetts along with Illinois and Washington, D.C., for providing incentives for low- and moderate-income households to access community solar programs.

Janine Weisman is an EcoRI News contributor.

Mature Massachusetts

“Truth and Wisdom Assist History in Writing, by Jacob de Wit, 1754

“Massachusetts is the first place in America to reach full adulthood. The of America is still in adolescence.’’

— Uwe Reinhardt (1937-2017), Princeton economics professor and health-reform expert

Martha Bebinger: Mass. COVID-19 contact tracers might offer milk or help with rent

BOSTON

It’s a familiar moment. The kids want their cereal and the coffee’s brewing, but you’re out of milk. No problem, you think — the corner store is just a couple of minutes away. But if you have COVID-19 or have been exposed to the coronavirus, you’re supposed to stay put.

Even that quick errand could make you the reason someone else gets infected. But making the choice to keep others safe can be hard to do without support.

For many — single parents or low-wage workers, for instance — staying in isolation is difficult as they struggle with how to feed the kids or pay the rent. Recognizing this problem, Massachusetts includes a specific role in its COVID-19 contact-tracing program that’s not common everywhere: a care resource coordinator.

Luisa Schaeffer spends her days coordinating resources for a densely packed, largely immigrant community in Brockton, Mass.

On her first call of the day recently, a woman was poised at her apartment door, debating whether to take that quick walk to get groceries. The woman had COVID-19. Schaeffer’s job is to help clients make the best choice for the public — sometimes, the help she offers is as basic, and important, as the delivery of a jug of milk.

“That’s my priority. I have to put milk in her refrigerator immediately,” Schaeffer said.

“Most of the time it’s the simple things, the simple things can spread the virus.”

The woman who needed milk was one of eight cases referred to Schaeffer through the state government’s Community Tracing Collaborative. Contact tracers make daily calls to people in isolation because they’ve tested positive or those in quarantine because they’ve been exposed to the coronavirus and must wait 14 days to see if they develop an infection. The collaborative estimates that between 10% and 15% of cases request assistance. Those requests are referred to Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators.

“So many people are on this razor-thin edge, and it’s often a single diagnosis like COVID that can tip them over,” said John Welch, director of operations and partnerships for Partners in Health’s Massachusetts Coronavirus Response, which manages the state’s contact-tracing program.

He said a role such as resource coordinator becomes essential in getting people back to “a sense of health, a sense of wellness, a sense of security.”

With milk on its way, Schaeffer dialed a woman who needed to find a primary-care doctor, make an appointment and apply for Medicaid. That call was in Spanish.

With her third client, Schaeffer switched to her native language, Cape Verdean Creole. The man on the other end of the line and his mother had both been sick and out of work. He applied for food stamps and was denied. Schaeffer texted the regional head of a state office that manages that program. A few minutes later, the director texted back that he was on the case.

Schaeffer, who has deep roots in the community, is on temporary loan to the state’s contact-tracing collaborative and will later return to her job, helping patients understand and follow their prescribed treatments at the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center.

The collaborative said most client requests are for food, medicine, masks and cleaning supplies. COVID-19 patients who are out of work for weeks or who don’t have salaried jobs may need help applying for unemployment or help with rental assistance — available to qualified Massachusetts residents.

Care-resource coordinators even connect people with legal support when they need it. An older woman employed in the laundry room at a nursing home was told she wouldn’t be paid while out sick. Schaeffer got in touch with the Community Tracing Collaborative’s attorney, who reminded the company that paid sick leave is required of most employers during the pandemic.

“So, now, everything’s in place. She started getting paid,” Schaeffer said.

There are glitches as the care-resource coordinators try to support people isolating at home. Some workers who are undocumented return to work because they fear losing their jobs. When the local food bank runs out, Schaeffer has had to scramble to find a local grocer to help. The free canned goods or vegetables can be like foreign cuisine for Schaeffer’s clients, some of whom are from Cape Verde and Peru. In those cases, she can reach out to a nutritionist and set up a cooking lesson via conference call.

“I love the three-way calls,” she said, beaming.

Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators have responded to more than 10,500 requests for help so far through Massachusetts’s contact-tracing program. Demand is likely greater in cities such as Brockton, with higher infection rates than most of the state and a 28.7 percent lower median household income.

Massachusetts has carved out care-resource coordination as a separate job in this project. But the role is not new. Local health departments routinely include what might be called support or wrap-around services when tracing contacts. With cases of tuberculosis, for example, a public-health worker might make sure patients have a doctor, get to frequent appointments and have their medications.

“You can’t have one without the other,” said Sigalle Reiss, president of the Massachusetts Health Officers Association.

Partners in Health’s Welch, who is advising other states on contact tracing, said the importance of having someone assist with food and rent while residents isolate isn’t getting enough attention.

“I don’t see that as a universal approach with other contact-tracing programs across the U.S.,” he said.

Some contact-tracing programs that schools, employers or states have erected during the pandemic cover only the basics.

“They’re focused on: Get your positive case, find the contacts, read the script, period, the end,” said Adriane Casalotti, chief of government and public affairs at the National Association of City and County Health Officials. “And that’s really not how people’s lives work.”

Casalotti acknowledged that the support role — and services for people isolating or in quarantine — adds to the cost of contact tracing. She urges more federal funding to help with this expense as well as a federal extension of the paid sick time requirement, and more money for food banks so that people exposed to the coronavirus can make sure they don’t give it to anyone else.

“Individuals’ lives can be messy and complicated, so helping them to be able to drop everything and keep us all safe — we can help them through the challenges they might have,” Casalotti said.

This story is part of a partnership that include WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Martha Bebinger, WBUR: marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger

Brockton City Hall, built in 1892, back in the era when the city called itself “The Shoemaking Capital of the World.’’

Disease threatens beech trees

North American beech tree in the fall

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) is asking residents to monitor beech trees for signs of leaf damage from beech leaf disease (BLD). Early symptoms include dark striping on a tree’s leaves parallel to the leaf veins and are best seen by looking upward into a backlit canopy.

The dark striping is caused by thickening of the leaf. Lighter, chlorotic striping may also occur. Both fully mature and young, emerging leaves show symptoms. Eventually, the affected foliage withers, dries, and yellows. Drastic leaf loss occurs for heavily symptomatic leaves during the growing season and may appear as early as June, while asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic leaves show no or minimal leaf loss. Bud and leaf production also are impacted.

BLD was detected in the Ashaway area of Hopkinton and in coastal Massachusetts this year, according to DEM. Before these findings, the disease was only known to be in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut. The disease is caused by a kind of nematode, microscopic worms that are the most numerically abundant animals on the planet.

While there are good species of nematodes, the BLD nematodes cause leaf damage that leads to tree decline and death. At this time, they are known to only affect American, European, and Oriental beech species. Currently, there is no defined treatment, as nematodes are difficult to control in the forest environment. Research is underway to identify possible treatments for landscape trees.

All ages and size of beech are affected, although the rate of decline can vary based on tree size. In larger trees, disease progression is slower, beginning in the lower branches of the tree and moving upward. The disease also appears to spread faster between beech trees that are growing in clone clusters, as it can spread through their connected root systems. Most mortality occurs in saplings within two to five years. Where established, BLD mortality of sapling-sized trees can reach more than 90 percent, according to DEM.

The state agency encourages homeowners and forest landowners to monitor their beech trees and report any suspected cases of BLD to DEM’s Invasive Species Sighting Report.

New Hampshire's lucrative fireworks exports menace neighbors

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As it turns out, many perhaps most, of those fireworks that have ruined life recently for many people in Providence, Boston and other New England cities came from New Hampshire, that old “Live Free or Die” parasite/paradise (where I lived for four years). There, out-of-state noisemakers stock up and take the explosives back to Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut, where they ignite them all over the place, with the worst impact in cities. While the fireworks are illegal in densely populated southern New England, they’re legal in the Granite State.

New Hampshire has long made money off out-of-staters coming to buy cheap (because of the state’s very tax-averse policies) booze and cigarettes. The state also has loose gun laws. Fireworks are in this tradition.

That’s its right. But it could be a tad more humane toward people in adjacent states by making it clear to buyers at New Hampshire fireworks stores that the explosives they’re buying there are illegal in southern New England.

Because of our federal system, states that may want to control the use of dangerous products can be hard-pressed to do so because residents may find it easy to drive to a nearby state and get the stuff. Still, in compact and generally collaborative New England, it would be nice if New Hampshire, much of which is exurban and rural, would consider the challenges of heavily urbanized Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut as they seek to limit the use of fireworks, especially in cities. Granite Staters might remember that much of the state’s affluence stems from its proximity to that great wealth creator Greater Boston and show a little gratitude. (This reminds me of how Red States are heavily subsidized by Blue States, whose taxes fund much of the federal programs in the former.)

Ah, the federal system, one of whose flaws is painfully visible in the COVID-19 pandemic. Look at how the Red States, at the urging of the Oval Office Mobster, too quickly opened up, leading to an explosion of cases, which in turn hurts the states that had been much tougher and more responsible about imposing early controls. But yes, the federal system’s benign side includes that states can experiment with new programs and ways of governance, some of which may become national models, acting as Justice Louis Brandeis called “laboratories of democracy’’.

To read more about New Hampshire’s quirks, please hit this link.