Roger Warburton: An affordable plan to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions

The shore of Easton’s Point, in Newport. The neighborhood is very vulnerable to flooding associated with global warming.

— Photo by Swampyank

From ecoRI. org

NEWPORT, R.I.

It has been known for sometime that a reduction in greenhouse gases would have significant public-health benefits: less pollution means fewer deaths, fewer emergency room visits, and a better quality of life.

It’s also well known that reducing greenhouse gases would decrease the financial damages from hurricanes and storms, from droughts, and from coastal flooding.

The question, until now, has been: How do we pay for the necessary infrastructure changes?

A recent Princeton University study, Net-Zero America, presents a practical and affordable plan for the United States to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050.

Although it’s a massive effort, the plan is affordable because it only demands expenditures comparable to the country’s historical spending on energy.

“We have to immediately shift investments toward new clean infrastructure instead of existing systems,” according to Jesse Jenkins, one of the project’s leaders.

The plan is also practical, because it uses existing technology. No magic tricks are required.

The plan is also remarkably detailed with analyses at the state and, sometimes, at the county level. For example, the report includes an estimate of the increase in jobs in Rhode Island if the plan were to be implemented.

In nearly all states, job losses in the fossil-fuel industry are more than offset by an increase in construction and manufacturing in the renewable-energy sector.

The motivation behind the recent study is clear: Climate change is “the most dangerous of threats” because it “puts at risk practically every aspect of our material well-being — our safety, our security, our health, our food supply, and our economic prosperity (or, for the poor among us, the prospects for becoming prosperous).”

The challenges are not underestimated: the burning coal, oil, and natural gas supply 80 percent of our energy needs and more than 60 percent of our electricity. Their greenhouse-gas emissions can’t be easily reduced or inexpensively captured and sequestered away.

The plan

The Net Zero America study details the actions required to achieve net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050. That goal is essential to avert the costly damages from the climate crisis.

The study highlighted six pillars needed to support the transition to net-zero:

End-use energy efficiency and electrification/consumer energy investment and use behaviors change (300 million personal electric vehicles and 130 million residences with heat pump heating).

Cleaner electricity (wind and solar generation and transmission, nuclear, electric boilers and direct air capture).

Bioenergy and other zero-carbon fuels and feedstocks (hundreds of new conversion facilities and 620 million t/y biomass feedstock).

Carbon dioxide capture, utilization, and storage (geologic storage of 0.9 to 1.7 giga tons CO2 annually and capture at some 1,000 facilities).

Reduced non-CO2 emissions: (methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorocarbons).

Enhanced land sinks (forest management and agricultural practices).

One of the study’s key findings is that in the 2020s all scenarios create about 500,000 to 1 million new energy jobs across the country. There are net job increases in nearly every state.

The pathways

The plan outlines five distinct technological pathways that all achieve the 2050 goal of net-zero emissions.

The authors don’t conclude which of the pathways is “best,” but present multiple, affordable options. All pathways only require investment and spending on energy in line with historical U.S. expenditures; around 4 percent to 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The five pathways are:

High electrification: Aggressively electrifying buildings and transportation, so that 100 percent of cars are electric by 2050.

Less high electrification: This scenario electrifies at a slower rate and uses more liquid and gaseous fuels for longer.

More biomass: This allows much more biomass to be used in the energy system, which would require converting some land currently used for food agriculture to grow energy crops.

All renewables: This is the most technologically restrictive scenario. It assumes no new nuclear plants would be built, disallows below-ground storage of carbon dioxide, and eliminates all fossil-fuel use by 2050. It relies instead on massive and rapid deployment of wind and solar and greater production of hydrogen.

Limited renewables: This constrains the annual construction of wind turbines and solar power plants to be no faster than the fastest rates achieved in the United States in the past but removes other restrictions. This scenario depends more heavily on the expansion of power plants with carbon capture and nuclear power.

In all five scenarios, the researchers found major health and economic benefits. For example, reducing exposure to fine particulate matter avoids 100,000 premature deaths, which is equivalent to nearly $1 trillion in air pollution benefits, by midcentury compared to the “business-as-usual” pathway.

Wind and solar power, along with the electrification of buildings — by adding heat pumps for water and space heating — and cars, must grow rapidly this decade for the nation to be on a net-zero trajectory, according to the study. The 2020s must also be used to continue to develop technologies, such as those that capture carbon at natural-gas or cement plants and those that split water to produce hydrogen.

“The current power grid took 150 years to build. To get to net-zero emissions by 2050, we have to build that amount of transmission again in the next 15 years and then build that much more again in the 15 years after that. It’s a huge change,” according to Jenkins.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Net-Zero American, E. Larson, C. Greig, J. Jenkins, E. Mayfield, A. Pascale, C. Zhang, J. Drossman, R. Williams, S. Pacala, R. Socolow, EJ Baik, R. Birdsey, R. Duke, R. Jones, B. Haley, E. Leslie, K. Paustian, and A. Swan, Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts, interim report, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., Dec. 15, 2020.

Grace Kelly: North Atlantic Rail's vast initiative for our region

The seven-state initiative, with the six New England states and downstate New York, would be built in three phases.

— From North Atlantic Rail

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A group of transit professionals, activists, elected officials and organizations want the North Atlantic region to ride the rails into the future.

The North Atlantic Rail (NAR) initiative proposes connecting small and mid-sized urban centers throughout New England with a high-speed trunk line. It also calls for bolstering and connecting regional rail networks, paving the way for a cleaner, more equitable regional transportation system. The trunk line would operate at 200 mph, and regional and branch lines between 80 and 120.

The NAR initiative also includes building a 16-mile rail tunnel under Long Island Sound, connecting New York City to Boston, with stops in Connecticut and Providence, in a 100-minute ride. In Rhode Island, components include frequent high-speed rails from Kingston, T.F. Green International Airport and Providence to Boston.

The idea for a North Atlantic Rail network was born in 2004 as part of a University of Pennsylvania studio project headed by Robert Yaro, a planner and former president of the New York City-based Regional Plan Association.

“We looked at growth trends in the country and identified the emergence of what we call mega regions,” Yaro said. “And these places are all 300 to 600 miles across, so they’re too big to be easily traversed by automobile and too small to be easily, efficiently traversed by the airplane.”

Six years later, in 2010, another studio project was hosted after Amtrak came out with a proposal for a $50 billion project to reduce travel times between New York and Washington, D.C., by 15 minutes.

“We said, ‘That sounds like a lot of money for not a lot of benefit,’” Yaro recalled. “So we convened another studio … with some very talented professional engineering advisors … and we came up with a high-speed, world-class rail proposal for the Northeast.”

One person who attended the presentation was Joe Biden.

“Ten minutes into the presentation and Biden says ‘Goddamnit, I've been waiting for this for 30 years. Let's do it,’” Yaro said.

And now that Biden is president and pushing a $2 trillion sustainable infrastructure and clean energy plan, NAR is putting the pedal to the metal.

“We see this as a kind of once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get this thing done,” Yaro said. “The key to making ticket prices affordable is to have the federal government cover the capital cost. Until the Georgia Senate races were decided, everybody just kind of rolled their eyes when we said that, but now it's something that’s a very serious likelihood. It’s more than a possibility; it’s gonna happen.”

NAR steering committee members have estimated that the project would cost a total of $105 billion to design and build the top priority projects and trunk line.

The benefits of a high-speed rail go beyond interconnectedness, and NAR proponents believe that it would also stimulate the economy by creating jobs, result in the creation of more affordable housing, and promote environmentally friendlier transportation through electric trains.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), rail travel has a “much lower carbon intensity” compared to other modes of transportation, such as air and car. IEA also notes that if intensive, aggressive rail transportation was implemented globally, carbon dioxide emissions could peak by the late 2030s.

“The next economy that wants to emerge by disrupting the carbon economy is a green economy,” said Christopher “Kip” Bergstrom, a project manager at the Connecticut Office of Policy and Management and member of the NAR steering committee. “Anything that carbonized is just a dead man walking.”

The NAR also promotes the idea that high-speed rail will create a more equitable society by allowing people to easily commute to work and by creating job opportunities and wealth redistribution within urban areas.

“The opportunity to reduce our carbon footprint, while simultaneously reducing income inequality, lies in re-localizing and shortening the chains of supply and distribution; and in building local wealth and redistributing it in a circular rather than extractive business model,” wrote Bergstrom in a white paper titled North Atlantic Rail: Building a Just and Green Economy.

The coronavirus pandemic has underscored a lot of these societal problems, making pushing this effort forward all the more urgent.

“I think it’s important to underscore, why now?” said John Flaherty, deputy director of Grow Smart Rhode Island, one of the NAR’s associated organizations. “This is about much more than improved mobility. It’s about an economic recovery, it’s about climate. In the Northeast 40 percent of the emissions are from the transportation sector … so unless we do something that’s bold and transformational, we’re never going to get our arms around that.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News reporter.

URI student to seek 3 semi-aquatic animal species in Rhode Island

Muskrat

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A University of Rhode Island graduate student will be scouring lakes, ponds and wetlands throughout Rhode Island over the next three years to search for signs of three semi-aquatic mammals.

Traveling via kayak, John Crockett will search for evidence of muskrats, beavers and river otters to document their distribution throughout the state.

“The main goal of the study is to get a good sense of the distribution of each species across the state,” said Crockett, a native of Fort Collins, Colo., who is collaborating on the study with URI assistant professor Brian Gerber. “To do that, we’re conducting an occupancy analysis, which means we’re going out looking for signs of tracks, scat, chewed sticks, lodges, and sightings of the animals.”

All three species have been the target of trappers in Rhode Island for many years — though the General Assembly banned the trapping of river otters in the 1970s — and most of what state wildlife officials know about the animals is derived from trapping data. But since trapping has been decreasing in popularity in recent years, less and less data about the animals are being collected.

Crockett will spend much of the next three years looking for signs of muskrats, beavers, and river otters Rhode Island.

“We want to make sure we have a good assessment of where these mammals are found,” Gerber said. “It’s been 10 or 15 years since anyone has spent much time looking for them, and we want to see if we find any changes in their distribution since those earlier surveys.”

Muskrats are in decline across much of their U.S. range, according to Crockett, and now they are difficult to find. He said the decrease in trapping activity has made it difficult to tell whether the animals are in decline in Rhode Island or if the lack of trapping just makes it appear to be so.

Since river otters haven’t been trapped for about 50 years, little is known about their distribution and population in the state.

River otters

Beavers are believed to have recovered well after being extirpated from the area because of unregulated trapping and forest clearing in the 1800s.

“Now they are creating conflicts with their dams causing flooding in some places,” Gerber said. “We’d like to be able to identify the habitat features where beavers are doing well and those areas where they are likely to cause conflict. To do that, we need distribution data.”

Beaver

Crockett expects to conduct his surveys from December through March for the next three years, as well as periodic summer surveys. He eventually hopes to be able to estimate the probability that any of the three species will be found in a given habitat. He started the project in December 2020.

“Part of what we’re doing is trying to relate their distribution to changes in land use,” he said. “We have pretty good data on how these wetlands have shifted over time, so hopefully we can find some hint of an answer about why these animals’ populations are changing.”

The URI scientists are working closely on the project with wildlife biologists at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management so the data can be used to help prioritize habitat for protection and inform management decisions on trapping limits.

Fisher

This is one of two research projects that Gerber is leading that focus on learning more about Rhode Island’s mid-sized predators (river otters are predators). The other is investigating the distribution and movement patterns of fishers in the state.

More land bordering S.E. Mass. BioReserve to be protected

In the Southeastern Massachusetts BioReserve

By ecoRI News staff

More than 50 acres of woods and wetlands that border the massive Southeastern Massachusetts BioReserve and drain toward the East Branch of the Westport River will be permanently protected from development through a partnership between the City of Fall River and the Buzzards Bay Coalition.

The land, now owned by the city and on which the Buzzards Bay Coalition will hold the conservation restriction, sits in the northwestern edge of the Buzzards Bay’s watershed — the area in which streams and groundwater flow toward the bay — and it feeds Copicut Reservoir and North Watuppa Pond, the source of Fall River’s drinking-water supply.

The woodlands also provide habitat for several threatened species, including the eastern box turtle and the marbled salamander, and offer public access to the extensive trail network that runs throughout the Bioreserve and its associated properties.

“The Bioreserve is one of the largest tracts of contiguous forest in eastern Massachusetts, and much of it drains toward Buzzards Bay and the Westport River,” said Mark Rasmussen, president of the Buzzards Bay Coalition. “Keeping it natural helps to preserve water quality for Fall River’s residents and for the people, plants, and animals who live around the bay.”

The newly protected lands comprise two properties — the 38-acre former Costa-Mello farm off Yellow Hill Road and the 16-acre Desmarais property off Indian Town Road — both of which connect to The Trustees of Reservations’ 516-acre Copicut Woods property and the city of Fall River’s massive Watuppa Reservation, which covers 4,800 acres.

The two properties were originally identified for future preservation during the city of Fall River’s first Open Space and Recreation Plan, which was completed in 1997. More recently, the city used Community Preservation Act money to buy the land, which had been placed on the market for sale and development.

Michael Labossiere, the watershed forester for the city of Fall River, said the extension of the 13,600-acre expanse of the Bioreserve to these new properties is good news for the environment, for wildlife, and for people who live in the region.

“More and more people are beginning to find the Southeastern Massachusetts Bioreserve and visiting to discover it for themselves,” he said. “And their reaction is always the same: ‘it’s beautiful, it’s peaceful, it’s quiet. It’s a place where I can get my exercise; I can bring my family.’ Adding these new properties to the Bioreserve is good for our residents, it’s good for the environment and it protects our water supply.”

Recent improvements to existing paths on the two properties already connect to the trail systems at Watuppa Reservation and at Copicut Woods. Additional improvements, such as the addition of small parking areas, may be made in the future as usage of the area grows.

Grace Kelly: Book author touts easy, healing walks

Marjorie Hollman Turner

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Thirty years ago Marjorie Turner Hollman found her right side paralyzed after brain surgery. She was unable to drive in the seven years of recovery that followed and turned to writing and taking walks down her dead-end road for solace.

When she met her second husband, an avid outdoorsman, she slowly began to move beyond handicap-accessible walks to what she now calls “easy walks.”

“If I had not found myself on a hospital bed paralyzed after brain surgery, I wouldn’t be doing easy walks,” said Turner Hollman, who lives in Bellingham, Mass., which is just over the Rhode Island border near Cumberland. “I have healed to the extent that I am able to walk with support, meaning hiking poles, and I’m very selective of where I choose to walk. I’m not your Appalachian Mountain Club material.”

Over the years, Turner Hollman sought out more of these easy walks, which she defines as “walks that don’t have too many roots, don’t have too many rocks, are relatively level … with something of interest along the way.”

In essence, walks that children, people with mobility issues, and those new to the outdoors can enjoy. Anyone, really.

And as Turner Hollman started her easy walks, she began to chronicle them — and the natural world around her — first for her local newspaper and later on her blog. Then, the questions came pouring in.

“I started having people find my Web site and they kept asking the question, Where’s Joe’s Rock?’” Turner Hollman said. “Well, it’s in Wrentham [Mass.] on Route 121 right near the Cumberland line, and after about the 500th time somebody came to that article, I said, ‘Well I think there’s a need here.’”

Turner Hollman wrote her first book, Easy Walks in Massachusetts, in 2014 to provide a one-stop-shop resource for anyone else in the state looking for easy walks. But the process was far from easy, since a lot of the walks she enjoyed weren’t in any guidebooks.

“At the time, they didn’t have any guides for outdoor things here. We’re not the Cape, we’re not in the White Mountains, we don’t have that cache,” she said. “Today, a lot of town offices have put up maps of their conservation areas, but when I started writing these in 2013, there were next to none. I visited town halls and said, ‘Help me!’ or called and said, ‘Do you have properties that kind of fit this?’ I did a lot of legwork.”

Since then, she’s written another three “easy walks” books, one of which was done in conjunction with the Ten Mile River Watershed Council, an organization with offices in Rumford, R.I., and Attleboro, Mass. This two-state watershed contains one of her favorite easy walks, Hunts Mills, which has a man-made dam and waterfall and trails that loop through the woods.

“It’s stunning and incredibly accessible,” Turner Hollman said. “You can even just sit in your car and watch the falls … it’s this hidden away little spot. It’s just a gem.”

In her most recent book, Finding Easy Walks Wherever You Are, Turner Hollman takes the principles of seeking out and enjoying easy walks to a broader level, providing tips and perspectives that anyone can use to seek out a special place to walk anywhere.

“There are plenty of places, but people don’t know how to find them because a lot of the time they’re off the beaten track,” she said. “I encourage people to consider places like, for example, your local cemetery to visit respectfully, understanding its first purpose is not a walking place … but they’re wonderful places to walk and often have paved roadways through them.

“So that’s a lot of what I talk about in finding easy walks wherever you are. It’s providing ideas that people maybe don’t think about.”

The book is also a culmination of Turner Hollman’s personal experience and belief that anyone, regardless of ability, can go on a walk.

“What I’ve learned in sharing Easy Walks is that many people can enjoy these outings, regardless of ability,” she wrote in a blog post from 2015. “Rather than my disability creating a barrier, I’ve found that working with, in spite of, and because of my disability has enriched my life, and the lives of many others. … These days I’m even more determined to search out and point others to places they can enjoy together.”

Grace Kelly is a journalist with ecoRI News.

New camera might save Right Whales

Right Whale with her calf

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The beginning of the calving season for North Atlantic Right Whales, one of the rarest marine mammals, is looking promising with four newborn calves observed in December. But the outlook for the species, whose global population is estimated at only 360 individuals, remains grim. Between fishing-gear entanglements and collisions with ships, more whales have died in recent years than were born.

A new technology on the horizon may help to reduce one of those threats, however. A smart-camera system invented by a team of scientists and engineers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts is being tested in local waters and could be deployed on vessels traversing the East Coast to reduce the threat of ships striking Right Whales.

“The idea is simple,” said WHOI assistant scientist Daniel Zitterbart, who is leading the project. “We took a commercial thermal imaging camera, highly stabilized for roll and pitch, and a computer algorithm that looks at images and tries to tease out what’s a whale compared to what’s a wave or a bird or whatever.

“The key part is, if you’re in a large vessel and you know there’s a whale 300 yards in front of you, it’s probably too late for you to turn away from it. Our aim is to push the detection range as far as we can, which makes things difficult on a rocking boat. But getting the range we need to make a difference for the animal is the objective.”

A prototype of the smart-camera system was tested last summer on a research vessel in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, in Massachusetts Bay, about midway between Gloucester and Provincetown, where humpback whales congregate to feed each year. A similar land-based installation was also deployed at a busy shipping channel in British Columbia traversed by endangered southern resident Killer Whales. The initial tests were promising.

“If you’re talking about very large vessels like tankers or cargo vessels, they may not be maneuverable enough for the detection ranges we get, but for cruise vessels, ferries, and fishing vessels that are more maneuverable, it definitely can make a difference,” Zitterbart said.

A little larger than a half-gallon milk carton, the camera system must be installed at least 15 feet above the water line to be effective. Within seconds, it can detect the presence of whales a mile or more away and alert the captain in time for the vessel to slow down or change course.

Unlike human observers or spotter planes, which are occasionally used in the United States and Canada to watch for Right Whales and alert nearby ships, the camera system can spot whales in daylight and darkness with little effort.

James Miller, an ocean-engineering professor at the University of Rhode Island, invented a forward-looking sonar device about 20 years ago that could be used to detect whales, reefs, and other obstacles to navigation beneath the water’s surface. He commercialized the product by founding FarSounder Inc., a Warwick,R.I.-based company with clients around the world. The company’s sonar devices can scan up to 1,000 meters in front of a ship moving at speeds of up to 25 knots to detect underwater obstacles.

“Dr. Zitterbart's technology for detecting whales at the sea surface can be an important part of the solution for reducing ship strikes, one of the leading causes of death for large whales,” Miller said.

Zitterbart said sonar is a better detection method for sensing static objects beneath the surface, but he believes his thermal camera system is more effective at detecting moving objects such as whales that may only be noticed for a few seconds. Both technologies can be hampered by challenging environmental conditions.

The recipient of the 2019 Young Investigator Award from the U.S. Office of Naval Research for his work on whale detection, Zitterbart previously developed a thermal imaging system for protecting whales and other marine mammals from underwater noise produced by air guns used in seismic surveys.

Assuming that his tests are successful this year, Zitterbart plans to deploy his camera system on a number of vessels without his development team aboard to ensure that remote troubleshooting can be conducted effectively. Eventually, he hopes to find a company interested in commercializing the technology.

“Thermal imaging systems are a powerful new tool in real-time whale detection,” he told Ocean Insights. “Used alone or in conjunction with acoustic monitoring, this technology could significantly reduce the risk of vessel strikes.”

Todd McLeish is a Rhode Island resident and nature writer .

Roger Warburton: Nov. was the warmest Nov. yet recorded

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Stop me if you’ve heard this story before: Last month was the warmest ever.

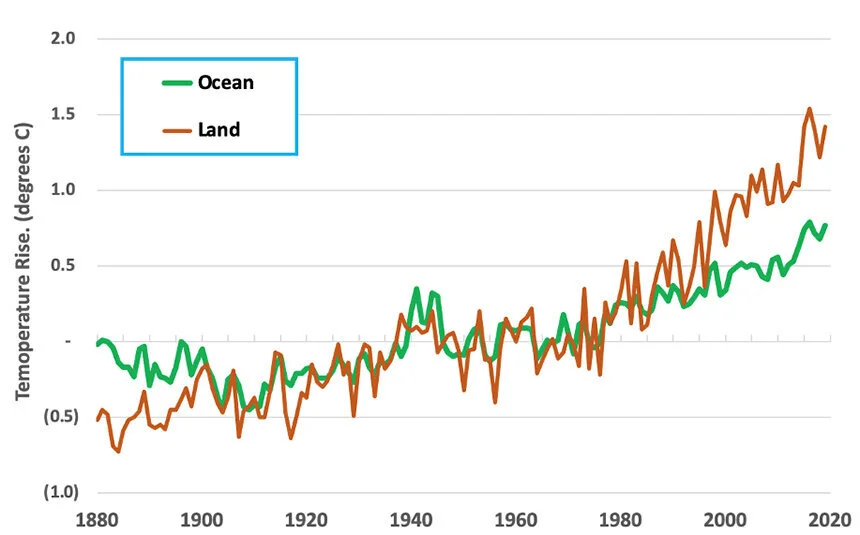

The latest global temperature data show that November 2020 was the warmest November ever recorded. The above figure shows the overall trend in global temperatures since 1880.

The red line for 2020 shows that average temperature for November was significantly above that of previous years. The significant rise in November’s temperature makes it very likely that 2020 will be the warmest year on record.

The figure below shows the average global November temperatures since 1880. The rise in November temperatures is quite substantial. The figure also shows that recent November temperature rises have been even more dramatic.

November mean surface air temperatures over land and ocean every decade since 1880. Data source: NASA GISTEMP. (Roger Warburton/ecoRI News)

In fact, the rise in November temperatures since 2015 is in line with a particularly disturbing trend: The latest data show that, since 2015, the warming trend is accelerating. The figure below shows the seriousness of the problem.

Global air temperatures over land and ocean. The yearly mean, blue, and the 5-year mean, red, have risen significantly above the gray trend line. Data source: NASA GISTEMP. (Roger Warburton/ecoRI News)

The gray line represents the steadily rising global temperature that was reasonably steady between 1970 and 2015. Since then, the temperature rise has accelerated. This is shown in the figure by the blue and red curves rising significantly above the gray trend line.

The gray trend line has often been used to predict long-term impacts of the future temperature rise. If the acceleration continues, many of the current estimates of the impacts of global warming will be seen as severely underestimated.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: GISTEMP Team, 2020: GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), version 4. NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Dataset accessed 20YY-MM-DD at https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/. Lenssen, N., G. Schmidt, J. Hansen, M. Menne, A. Persin, R. Ruedy, and D. Zyss, 2019: Improvements in the GISTEMP uncertainty model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 124, no. 12, 6307-6326, doi:10.1029/2018JD029522.

Grace Kelly: The bumpy road to R.I.’s East Bay Bike Path

Facing south near the East Bay Bike Path's southern terminus, in Bristol

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

“These days it’s hard to find someone who thinks creating the East Bay Bike Path was a foolish idea.” So begins a Providence Journal article written in 1999 by Sam Nitz, which chronicled the bike path’s beginnings and eventual completion.

The same could be said in 2020, a year when a pandemic forced people to get creative with their time. They took to the outdoors when the weather turned warm, with many dragging a set of wheels to a Rhode Island bike path that runs from Providence to Bristol.

I cruised along this path myself, dodging hand-holding couples, bold squirrels, and the occasional toddling roller-skater.

A map of the East Bay Bike Path from a 1984 pamphlet. Construction of the trail took place from 1987-92.

While looking at the path today might give the impression that it was a beloved idea all along, as Nitz noted in his article, “the path’s beginnings in the early 1980s were fraught with controversy and rancorous political debate.”

The 14.5-mile stretch of asphalt was hardly a shoo-in. In fact, it was met with raucous opposition, German shepherds, and even a letter to a high-level staffer of President Reagan begging for federal intervention.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The story of the East Bay Bike Path starts with an old stretch of railroad that connected Providence to Bristol, with stops in Riverside and Warren and a connecting line that went to Fall River, Mass. It was a handsome railway, with postcards and old photos depicting almost modern-looking platforms and stations — one particular image of the rail near the future Squantum Association, a private club in East Providence, could be from the 2000s.

But as automobiles began to capture the American spirit, the railway slowly faded into disuse and the passenger line ended in 1938. In 1976, the State of Rhode Island acquired the right of way for the old Penn Central line, the section that ran from East Providence to Bristol.

It would also be automobiles that would inspire Bristol state Rep. Thomas Byrnes Jr. in the late 1970s, to lead the charge to create a bike path on the old Penn Central line.

“When I started at the State House in ’78, the oil shortage was … tough,” said Byrnes in a 2002 interview with his daughter Judith. “People were driving bombers around and they were having a hard time keeping their cars filled with gas. So, they were talking about looking into alternative means of transportation to cut our use of oil.”

And one idea that came up: bicycles.

In the ’70s, the United States experienced a bicycle boom, with some 64 million Americans using bicycles regularly. A 1971 article in Time magazine noted that America was having “the bicycles biggest wave of popularity in its 154-year history.”

So, at the time when Byrnes started thinking about alternative methods of transportation, bicycles were everywhere, and other states such as Maryland were starting to investigate turning old railways into bike trails.

In March 1980, Byrnes and Matthew Smith, who was the Rhode Island speaker of the House at the time, wrote a joint bill that called for a study of bicycling as an alternative form of transportation and as an energy saver. The idea of the East Bay Bike Path was born.

What happened next was years of pushing through heated resistance.

“There was a lot of opposition, a lot of opposition,” said Robert Weygand, who was the chairman of the East Providence Planning Board in the early ’80s, and who later went on to be a U.S. congressman and Rhode Island lieutenant governor. “In every community there were people that came out opposed to it.”

Weygand became involved in the project through his work on the East Providence Planning Board and later as part of a group called Friends of the Bike Path. He saw its creation as a way to help restore East Providence’s once-rich history of activities and attractions along the water.

“We heard about what Tom [Byrnes] had been proposing for a bicycle trail along the railroad tracks … and we were in East Providence, which had a long history of having amusement parks and various venues along the railroad tracks,” Weygand said. “So we were interested in trying to reinvigorate the idea of having activities along the waterfront, which had been abandoned for a very, very long time.”

The East Bay Bike Path had plenty of fierce opposition, but had the support of the Rhode Island Department of Transportation and its then-director Edward Wood.

The wheels were now set in motion, and in 1982, Gov. J. Joseph Garrahy and the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (DOT), which was then led by Edward Wood, who died this year, threw their support behind the project and hired an engineering firm to research feasibility and design.

“The biggest thing that really helped us along the way was governor Joe Garrahy … he really embraced it,” Weygand said. “And also, there was a fella that was the head of the Department of Transportation, Ed Wood.”

But though Wood and Garrahy supported the project, many in their own circles were firmly against it.

“Even Wood at DOT ran into opposition by his own staff,” Weygand said. “They wanted to preserve the East Bay railroad track system … potentially for freight traffic and rail traffic … so his own staff was fighting him because they thought, if we give up the railroad tracks, we'll never get them back.”

Meanwhile, Byrnes, Weygand, a man named George Redman — you’ll find his name and portrait on the section of the bike path that crosses Interstate 195’s Washington Bridge — and a group of others were busy fighting their own battle on the ground to win the people of the five municipalities over on the idea.

“We constantly met, talked about different opportunities, did public hearings and meetings … and we’d get together periodically to share war stories about what was going on,” said Weygand, with a chuckle. “There was some real opposition. We had a public hearing in 1983 at the Barrington YMCA, and people were yelling and screaming and swearing at us, saying that all the criminals from Providence would use this bike path to come down and steal things from their homes. It was terrible.”

One vivid memory Weygand has of the resistance was when he helped organize a walk of the proposed area to give people a feel for what it could be like.

“One of the things that happened that day that we had this walk was, we had about 50 or so people go along the path … and in notifying all of the abutting owners, one of the owners was Squantum Club,” Weygand recalled. “We had invited them to join us along the way, and when we got to the Squantum Club, the manager was there with German shepherds and cars to prevent us from passing anywhere near their property.”

James W. Nugent, who was a member of the Squantum Association at the time, even went as far as to write a letter to James A. Baker III, a friend of his who was the chief of staff of President Reagan.

“At a time when the nation is looking for ways to cut expenditures and increase income, I thought it appropriate to call to your attention an expenditure that to me, and to many residents of Rhode Island, seems almost frivolous,” Nugent’s letter reads. “When there is publicity about people going hungry and dangerous federal deficits, the logic of expanding over $1 million on a bicycle path escapes me — especially when so many people along the route of the path object strongly to it. They fear increased vandalism and housebreaks from the transient traffic when their properties become more easily accessible.”

Nugent goes on to ask Baker to sway the federal government to withhold funds for the project.

Though opposition was strong, there were supporters who should not be discounted. One of them was Barry Schiller, who was the on the transportation committee of the environmental group Ecology Action.

In a 1984 letter to Wood, Schiller wrote, “This should be an ideal bikeway, scenic, safe and relatively flat that will become the pride of the East Bay.”

Schiller’s words were prophetic in some ways. Instead of being a so-called crime highway, the East Bay Bike Path has become a place where friends and families gather and exercise. Instead of negatively affecting home values, living near the bike path is considered an asset. It’s also inspired other Rhode Island municipalities to build their own bike paths; there are eight today, according to DOT.

In the end, the proponents won out, and on May 22, 1986 ground was broken at Riverside Square, and the East Bay Bike Path became a reality.

“It seems like a long time ago, but it really wasn’t,” Weygand said. “It was absolutely wonderful, breaking ground and seeing it constructed.”

Construction took place from 1987-92, and today when Rhode Islanders cruise by on its blacktop, many are likely unaware of all it took for it to get done. But those who were there, those who helped push it through, they remember.

“Every time I ride the East Bay Bike Path, it gives me the inspiration to keep going, because I knew it took persistence in the face of strong opposition to get it done,” Schiller said. “It’s a lesson for all of us to not give up.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News reporter.

Snowy Owls need a lot of space

A male Snowy Owl

From ecoRI News

A few Snowy Owls are typically spotted in Rhode Island each year, and over the past few weeks a couple of these majestic birds have been sighted, according to the Audubon Society of Rhode Island.

As nature enthusiasts flock to the shore in hopes of glimpsing these birds, Audubon experts worry about the stress these owls are facing, caused by their long journey, shortage of food, and human interference.

Chilly temperatures and fewer food sources mean that winter months can be challenging for all birds. They need to be constantly refueling with high-protein energy sources to maintain their body temperature. Birds also can easily become stressed by people getting too close. Energy used to escape from perceived danger is energy that can’t be used to find food sources and shelter. All birds, including Snowy Owls, can face serious health consequences from nature enthusiasts trying to get too close or take the perfect photograph.

Over the past several months, rare bird species have been sighted in Rhode Island, including a common cuckoo in Johnston. The Audubon Society, while understanding the enthusiasm that these rare sightings bring, noted that trampled habitat and trespassers on private farmland was a result.

Audubon urges all birders and nature enthusiasts to be respectful of private property and the natural habitat that sustains birds and wildlife, including sections of wildlife refuges that may be closed to the public for critical conservation purposes.

Many wonder why Snowy Owls travel south to begin with, and why their numbers are higher in certain years.

“It's all about food,” said Lauren Parmelee, an expert birder and the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s senior director of education. “Snowy Owl numbers are closely connected to the populations of rodents in the Arctic region called lemmings. In years when there are plenty of lemmings, these owls lay more eggs and successfully raise a larger number young to adulthood. But when winter comes to the tundra, competition for food increases dramatically and many of the younger birds disperse beyond the boundaries of their arctic habitat.”

These hungry birds will then travel a great distance looking for food and will appear on the beaches and rocky shorelines in Rhode Island and other coastal states.

Audubon urges visitors to follow these guidelines for viewing Snowy Owls and other birds this winter:

Don’t try to creep close. Be content to view at a distance. Give Snowy Owls a space of 200-300 feet or more. This isn’t a bird you should be sneaking up on with your camera phone. Use binoculars and spotting scopes if you have them.

Try to stay as a group if there is more than one observer. Never encircle birds or owls. All viewers should stay on one side of the bird.

Snowy Owls are powerful hunters and very capable of capturing prey, so please don’t try to feed them.

Don’t observe these owls for an overly long period of time. Your presence causes stress.

Spread the word about respectful birding etiquette and keeping a safe distance. You can help to ensure that local birds survive the winter and that snowy owls have a better chance of making it home to the Arctic in the spring.

Snowy Owls are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

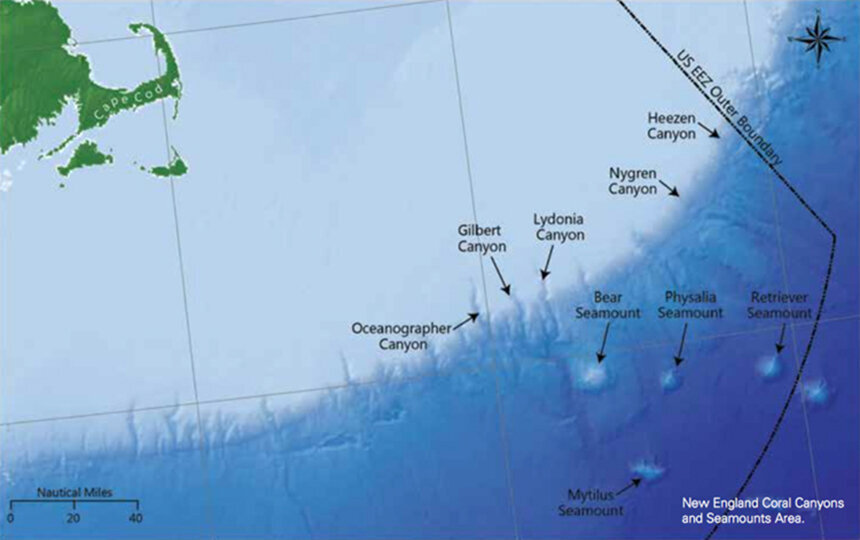

Roger Warburton: Ocean damage increases in CO2 buildup as climate warms

January sea surface temperatures off southern New England have risen significantly since 1980.

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Living in Rhode Island, we are aware how the ocean rules our weather. What is less well known is that climate change is fundamentally altering the waters off our coast.

The image above shows how the January temperature of the ocean off New England has changed since 1980. For example, vast areas of dark blue — representing temperatures around 41-43 degrees Fahrenheit — have shrunk and are now a lighter blue, representing temperatures around 43-45 degrees.

The effects of a temperature rise in the ocean are significantly different from a temperature rise over land. We experience this difference when we walk across a sandy beach on a hot day. Exposed to the same sunlight, the sand burns our feet while the ocean warms gradually to the perfect temperature for a summer swim.

Rhode Island’s climate is moderated because the ocean takes longer than the land to heat up over the summer and longer to cool down during the fall.

The global impact of this effect is shown in the image below, which shows that, over recent decades, the continents have warmed much more rapidly than the oceans. The Earth’s land areas were 1.4 degrees Celsius (2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 20th-Century average, while the oceans were 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer.

Since 1880, the Earth’s land temperature has risen faster than the ocean temperature. “

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

Unfortunately, the ocean’s smaller temperature rise isn’t good news, because the oceans can store more than four times as much heat as the land.

Even though ocean temperatures have risen less than the land’s, it’s becoming clear that the impacts of climate change depend on a complex interaction between dry land and the warming ocean.

Ships and buoys have been recording sea surface temperatures for more than a century. International cooperation and sharing of data between nations has created a global database of sea surface temperatures going back to the middle of the 19th century.

In addition, modern satellites remotely measure many ocean characteristics over the entire extent of the Earth’s oceans. The data are now so accurate that it’s possible to detect the small temperature rise from ships’ propellers as they traverse the oceans.

The warming of both the land and the oceans is caused by rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. When CO2 dissolves in the ocean, it forms carbonic acid, which in turn, breaks into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. Clams, mussels, crabs, corals and other sea life rely on those carbonate ions to grow their shells.

In 2015, Mark Gibson, deputy chief of marine fisheries at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, noted that ocean acidification is a “significant threat” to local fisheries.

In fact, a study published in 2015 found that the Ocean State’s shellfish populations are among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of acidification.

In polar regions such as Alaska, the ocean water is relatively cold and can take up more CO2 than warmer tropical waters. As a result, polar waters are generally acidifying faster than those in other latitudes.

The water in warmer regions can’t hold as much CO2 and are releasing it into the atmosphere. Therefore, the acidification from carbon dioxide is damaging the oceans in both polar and equatorial regions.

Warming oceans are also changing the winds that whip up the ocean, resulting in upwells from deep waters that are nutrient-rich but also more acidic.

Normally, this infusion of nutrient-rich, cool, and acidic waters into the upper layers is beneficial to coastal ecosystems. But in regions with acidifying waters, the infusion of cooler deep waters amplifies the existing acidification.

In the tropics, rising temperatures are slowing down winds and reducing the exchange of carbon between deep waters and surface waters. As a result, tropical waters are becoming increasingly stratified and more saturated with carbon dioxide. Lower layers then have less oxygen, a process known as deoxygenation.

Warming ocean temperatures have also caused a rapid increase of toxic algal blooms. Toxic algae produce domoic acid, a dangerous neurotoxin, that builds up in the bodies of shellfish and poses a risk to human health.

In coastal areas, such as Rhode Island, temperature changes can favor one organism over another, causing populations of one species of bacteria, algae, or fish to thrive and others to decline.

The sum of all these impacts is damaging to the Rhode Island economy. The state’s shellfish populations are already among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of a warmer ocean.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is an ecoRI News contributor and a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Figure 1 was generated using data from the Copernicus Climate Change and Atmosphere Monitoring Services (2020). The ERA5 dataset is produced by the European Space Agency SST Climate Change Initiative based on global daily sea surface temperature data from the Group for High Resolution Sea Surface Temperature and made available by the Copernicus Climate Data Store.

Figure 2 was generated using data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series.

Grace Kelly: Getting more Black and Brown kids out into nature

A meeting in the woods of Exeter, R.I., of students in the Movement Education Outdoors program.

— Photo by Grace Kelly for ecoRI News

EXETER, R.I.

A group of five 10th-graders tromp through a wooded path at the Canonicus Camp & Conference Center on Exeter Road. They talk about school, the platform Doc Martens they would love to have, and how New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is great but also, it’s probably better not to idolize politicians. {Canonicus was a 17th Century Narragansett Indian chief.}

Their guide on this excursion is Joann “Jo” Ayuso, founder of Movement Education Outdoors (MEO), an organization with a mission to provide outdoor experiences for community-based organizations serving Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) youth. She shows them nature.

“The outdoors is sacred, and yes, this land,” she said, and spreads her arms around her, gesturing at the grass and trees, “has a history of colonization, but I want us to feel welcome here. I want to invite you to make your own memories today, to decolonize this space. I introduce you to these spaces so you can own them and feel connected to the land.”

According to the National Health Foundation, while people of color make up nearly 40 percent of the population, 70 percent of the people who visit national forests, parks, and wildlife refuges are White. A mere 7 percent of national park visitors are Black.

There are many factors at play when it comes to communities of color not having the same opportunities to experience the outdoors. Ayuso said:

“I think it’s very important for people to know, that, for example, when your mom is a single parent, working three jobs, doesn’t have a car, how is she going to have time to take her kids hiking? And, unfortunately, bus lines don’t take you to any of the green space Rhode Island has to offer.”

There’s also the fact that outdoor gear is expensive, with basic equipment such as lightweight coats, hiking boots, and backpacks costing a premium.

“Equipment is always a barrier for young, low-income and urban youth,” Ayuso said. “Even having the proper layering for hiking in the fall or winter, that’s expensive.”

By starting MEO in 2018, Ayuso hopes to change this paradigm.

Ayuso’s journey from being born into poverty to being an outdoor educator for BIPOC youth started in the forests of the southern wild.

“One of my very first experiences with the outdoors was in the military,” she said. Ayuso entered the military after graduating from Joseph P. Keefe Technical High School, in Framingham, Mass., prompted in part by her brother who had also joined, and by the desire to work her way up in the world. While military service didn’t prove to be her dream, it was how she discovered her love of nature.

“One of the things I loved about the military was being outdoors, just hiking, having my rucksack on and just hiking for hours,” said Ayuso, who served in the Army in 1989-1996. “To this day, I can still remember smelling the eucalyptus trees in the South, and also smelling the pine trees when we would do our training early in the morning. It was just something that really helped me pass time, and that was one of the most memorable times of me experiencing the outdoors.”

Ayuso would come back to that moment years later, and it would be part of a series of experiences that would inspire her to create an organization to bring Black and Brown youth into nature.

In the years that filled her life between the military and MEO, Ayuso built a personal-training business in Wellesley, Mass., and left it, started a new life in Providence, learned she loved working with young people, began practicing mindfulness, and discovered her ancestral roots in Puerto Rico and West Africa.

But it was when she was hit by a car two years ago outside her Providence home and spent six months healing that she started to unravel what she wanted to do with her life.

“I had six weeks of recovery, and in those six weeks I was like, ‘I’ve gotta do something different,’” said the 48-year-old. “My partner and I just got to talking about what is it that you want to do for the rest of your life? What is it that you think you will enjoy?”

Her partner asked her to reflect on the past 15 years and think about the things she really loved.

“And I thought, ‘Damn, I really loved that time in the military when I was hiking. That was awesome.’ I felt like that was healing, that kept my mind kind of straight,” Ayuso recalled. “So my hiking experience in the military, the mindfulness training that I’ve had in the last 20 years, the Native and Black history I learned for myself, and seeing the environmental justice and climate change on Black and Brown bodies, that became the four pillars of Movement Education Outdoors.”

MEO partners with local schools such as Nowell Leadership Academy, in Providence, and such nonprofits as Riverzedge Arts, in Woonsocket, to bring underserved youth into the outdoors and to help them reflect on who they are and where they come from.

And on this chilly fall day in Exeter, the students are loving it.

As they walk through the forest of pine, oak and maple, they notice the acorns on the ground, the oak apple wasp galls tucked between fallen leaves, and learn about how beavers change the landscape to suit their needs.

They pause for a guided meditation at a bridge overlooking a pond and breathe in the cold air, watching as their breath billows around them when they exhale. They continue through the woods and stop at a rock wall to discuss the farming history of this land.

“So when the glaciers melted, they left lots of rocks here,” said a MEO intern. “And the colonizers used them to make rocks walls.”

Ayuso noted that these rock walls delineated farming property, and that between 1636 and 1750, South County farmers turned from enslaving Indigenous people to enslaving thousands of Blacks from Africa to make their farms into plantations comparable to those in the South.

The group continues onward and upward, heading to a steep incline and making their way to an overlook known as “The Pinnacle.”

The students pause at a large boulder, resting weary Converse-clad feet and shooting the breeze. Ayuso then asks them what made them want to be outside, how they came to be here. One said:

“I was a city person, but when I went on my first camping experience, it opened my eyes. I was so against it at first, but when I go on these trips, I’m so happy.”

Another student reminisced about her first time camping and how waking up outside was so special.

“The last time we went camping, my friend and I woke up at 5 a.m., and waking up to the morning dew, the smell of morning dew … it was so nice,” she said.

“It’s a break from the city, life with social media, everything feeling so controlled … when you’re outdoors, you’re on your own,” another student added.

Ayuso smiled as the group continued their discussion about life, nature, and what the future holds.

“Ya’ll are gonna make me cry,” Ayuso said, laughing. “You’re making me feel all the feels. I’m blessed to be here, to be able to do this.”

Grace Kelly is a journalist for ecoRI News.

Olivia Ouellette: How safely can coyotes co-exist with humans?

A coyote pouncing on prey in the winter

-Photo by Yifei He

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

University of Rhode Island graduate student Kimberly Rivera has been conducting a survey since the beginning of October on the coyote population in Rhode Island.

Rivera, who graduated in 2016 with a bachelor’s degree in environmental science from the University of Delaware, hopes to promote better co-existence between coyotes and Rhode Islanders.

Since the beginning of her work, Rivera has received about 425 completed responses. With a minimum goal of 500 completed surveys, Rivera plans to keep the survey open until at least December.

The survey takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and asks respondents about demographics — age, location, are you a full-time Rhode Island resident — and goes on to ask about any experiences with coyotes.

“Ultimately, what I really want to do is understand how people’s knowledge, belief and feelings tie back to these independent variables that were measured,” Rivera said.

Along with the survey, Rivera is also conducting more hands-on research using camera-trap technology. Initially intended for a bobcat study, these cameras are placed around Rhode Island, and when something walks by, it triggers the motion-sensor camera to take a series of photographs. These cameras then store the photographs, as well as save the date and time, letting Rivera look back and see when and where coyotes are most active.

Through her work, Rivera is trying to promote the acceptance and a better understanding of coyotes.

“I think co-existence is key moving into the future,” she said. “I want people to think about how they co-exist with coyotes and what that means to them.”

Rivera’s original plan was to travel to Madagascar to study seven native carnivore species there and see how the locals interact with those species. She was interested in seeing how people’s attitudes and knowledge about those species affected their interactions with them. The coronavirus pandemic required her to change her research plans.

Although her initial plans fell through, Rivera was still enthusiastic about reconstructing her project into a human-wildlife conflict study on coyotes, similar to what she would have researched in Madagascar.

“I’ve always had an interest in coyotes because on the East Coast they’re one of the only apex predators,” she said.

At the end of the survey there are a series of questions about how negatively people view coyotes in regards to certain issues, such as pets, livestock and property damage.

“I think it really depends on who you ask,” Rivera said. “I think there is potential for coyotes to be dangerous.”

One of the top concerns people have in Rhode Island in connection with coyotes is the safety of their pets.

“If you have small dogs that you are leaving out in the yard without fences or you have outdoor cats that are wandering around, there's always going to be a risk,” Rivera said. “And that could be coyotes or it could be a car hitting them, so it's just one of many risks.”

Olivia Ouellette is a University of Rhode Island journalism student.

Todd McLeish: Looking for a rare salamander

Marbled salamander

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

RICHMOND, R.I.

After dark at a well-hidden vernal pool, Peter Paton shined his flashlight back and forth at the moss-covered ground around the nearly-dry pond basin. He was searching for marbled salamanders, the only autumn-breeding salamander in New England, and one that is seldom seen except on rainy fall evenings. It didn’t take him long to spot one.

“I got one,” he called out. “Over here.”

Marbled salamanders, which grow to about 3.5-4.25 inches, are the second-largest salamander in the region — after only the spotted salamander — and their attractive black-and-white patterning makes them unmistakable. The one Paton found, a male, was on his way out of the pond basin, indicating that the animal had completed his mating duties and was headed to the forest to spend the winter underground.

Female salamanders were likely hidden in the sphagnum moss around the pond, where they remain for a month or more to guard their eggs until rain fills the pond and the eggs are protected from predators and the elements. The eggs hatch within days after being covered in water, and the larvae overwinter in the pond.

Paton, a professor of natural resources science at the University of Rhode Island, was confident of finding marbled salamanders at the Richmond site, since it was a place he studied and monitored in 2000 and 2001, when he and colleagues conducted an amphibian survey of 137 vernal pools around the state. Marbled salamanders were found in just four of the pools, however, making it one of the rarest pond-breeding amphibians in the region.

Previous efforts in the 1980s and ’90s by Chris Raithel, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, documented as many as 50 marbled salamander breeding sites in the state, mostly in Kent and Washington counties. There are no records from Bristol County or from areas adjacent to Narragansett Bay and few from the Blackstone Valley.

“The present localized distribution of marbled salamanders in Rhode Island may be related to habitat fragmentation and patch isolation,” Raithel wrote in his 2019 book Amphibians of Rhode Island. “If this effect is real, the species is secure only in the larger contiguous habitats of southern and western Rhode Island, and additional range retraction should be evident to future generations.”

Marbled salamanders require a very specific habitat for breeding: ponds that are surrounded by sphagnum moss and dry up in the summer, keeping fish and large dragonfly larvae from inhabiting the pond and preying on the salamander larvae.

“They tend to like relatively small ponds, and there aren’t many sites available that fill their habitat requirements,” Paton said.

In addition to habitat fragmentation, road mortality is also a significant concern for the species, because they are often crushed by vehicles as the adults cross roads to reach their breeding ponds or as juveniles disperse to find territories.

On the other hand, Paton said it’s possible that the changing environmental conditions associated with the warming climate may make southern New England more favorable to marbled salamanders in the future. Their current range extends as far south as northern Florida and eastern Texas, and populations in warmer climates tend to be considerably larger than those in Rhode Island.

“They aren’t very tolerant of the cold, so we’re at the northern limits of their range,” Paton said. “The larvae don’t grow much in the winter because it’s too cold, but once wood frogs arrive to breed in early spring, the salamander larvae feed on the frog tadpoles as their main fuel source to undergo metamorphosis.”

After metamorphosis, the salamanders leave their ponds and spend the rest of their lives in the forest, except for brief breeding periods each fall.

Marbled salamanders require a very specific habitat for breeding and they are not very tolerant of the cold.

Despite how few marbled salamander breeding sites were found during the last amphibian survey, a recent graduate student at the University of Massachusetts at Boston thinks a new survey method may detect the salamanders more effectively than traditional sampling methods.

Jack He, who graduated in May, used eDNA — environmental DNA collected from water or soil — to detect the presence of marbled salamanders even when the animals could not be seen.

“Everything sheds DNA in one form or another, like from skin cells or blood, and they release it into the environment,” He said. “Ideally, we can collect water or soil samples containing those cells and extract that DNA and sequence it to determine what species are present.”

He detected marbled salamander DNA in a number of water and soil samples from vernal pools in western Massachusetts. He calls it a less labor-intensive method of determining if the salamanders are present at a site than using dipnets to capture larvae in the spring, which is how Paton conducted his survey.

“I’ve done dipnet studies and compared them to eDNA, and I found that eDNA was a bit more effective,” He said.

Paton, however, isn’t convinced.

“My impression is that larvae are relatively easy to find, but I could be biased,” he said. “Maybe they’re in there and I missed them a lot. But however you do it, I suspect that marbled salamanders are still fairly rare in Rhode Island.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog. He’s a frequent EcoRI News contributor.

Frank Carini: The partial recovery of the Seekonk River

Looking out at the Henderson Bridge over the Seekonk from Providence’s Blackstone Park

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When driveways, highways, rooftops, patios and parking lots cover 10 percent of a watershed’s surface, bad things begin to happen. For one, stormwater-runoff pollution and flooding increase.

When impervious surface coverage surpasses 25 percent, water-quality impacts can be so severe that it may not be possible to restore water quality to preexisting conditions.

This where the Seekonk River’s resurgence runs into a proverbial dam. Impervious-surface coverage in the Seekonk River’s watershed is estimated at 56 percent. It’s tough to come back from that amount of development, but the the urban river is working on it, thanks to the efforts of its many friends.

The Seekonk River, from its natural falls at the Slater Mill Dam on Main Street in Pawtucket, R.I., flows about 5 miles south between the cities of Providence and East Providence before emptying into Providence Harbor at India Point. The river is the most northerly point of Narragansett Bay tidewater. It flows into the Providence River, which flows into Narragansett Bay.

While it continues to be a mainstay on the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s list of impaired waters, the Seekonk River is coming back to life.

“I started rowing at the NBC [Narragansett Boat Club] 10 years ago when I realized that I was on the shores really of a 5-mile-long wonderful playground,” Providence resident Timmons Roberts said. “I just think it’s a magical place, and seeing the river come back to life has meant a lot to me.”

The Narragansett Boat Club, which has been situated along the Seekonk River since 1838, recently held an online public discussion about the river’s recovery.

Jamie Reavis, the organization’s volunteer president, noted the efforts that have been made by the Blackstone Parks Conservancy, Fox Point Neighborhood Association, Friends of India Point Park, Institute at Brown for Environment and Society, Providence Stormwater Innovation Center, Save The Bay, and Seekonk Riverbank Revitalization Alliance, among others, to restore the beleaguered river.

“Having rowed on the river for over 30 years now, I can attest to their efforts,” Reavis said. “It was practically a dead river. It almost glowed in the dark back in the day. It is now teaming with life. Earlier this summer, a bald eagle flew less than 10 feet off the stern of my single with a fish in its talons. Watching it fly across the river and up into the trees is a sight I will not soon forget, nor is it one I could have imagined witnessing 30 years ago.”

Decades of pollution had left the Seekonk River a watery wasteland.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries some of the first textile mills in Rhode Island were built along the Seekonk River. The river, and one of its tributaries, the Blackstone River, powered much of the early Industrial Revolution. Mills that produced jewelry and silverware and processes that included metal smelting and the incineration of effluent and fuel left the Seekonk and Blackstone rivers polluted.

There are no longer heavy metals present in the water column of the Seekonk River, but sediment in the river contains heavy metals, including mercury and lead.

Swimming in the Seekonk River, which doesn’t have any licensed beaches, and eating fish caught in it aren’t recommended because of this toxic legacy and because of the continued, although declining, presence of pathogens, such as fecal coliform and enterococci. The state advises those who recreate on the river to wash after they have been in contact with the water. It also advises people not to ingest the water.

But, as both Roberts and Reavis noted, the Seekonk River is again rich with life and activity. River herring, eels, osprey, cormorants, gulls and the occasional seal and bald eagle can be found in and around the river. The same can be said of kayakers, fishermen, scullers, and birdwatchers.

The river’s ongoing recovery, however, is threatened by rising temperatures, sewage nutrients and runoff from roads, lawns, parking lots, and golf courses in two states that dump gasoline, grease, oil, fertilizer, and pesticides into the long-abused waterway.

The Sept. 30 discussion was led by Sue Kiernan, deputy administrator in the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Office of Water Resources. She has spent nearly four decades, first with Save The Bay and the past 33 years with DEM, working to protect upper Narragansett Bay.

She spoke about how water quality in upper Narragansett Bay, including the Seekonk River, has improved through efforts both large and small, from the Narragansett Bay Commission’s ongoing combined sewer overflow (CSO) abatement project to wastewater treatment plants reducing the amount of contaminants being dumped into the waters of the upper bay to brownfield remediation projects to the many volunteer efforts, such as the installation of rain gardens and the planting of trees, conducted by the organizations that sponsored her presentation.

She noted that nitrogen loads, primarily from fertilizers spread on lawns and golf courses, that are washed into the river when it rains, lead to hypoxia — low-oxygen conditions — and fish kills. Since 2018, six reported fish kills that combined killed thousands of Atlantic menhaden have been documented by DEM’s Division of Marine Fisheries in the Seekonk River.

Kiernan said excessive nutrients, such as nitrogen, stimulate the growth of algae, which starts a chain of events detrimental to a healthy water body. Algae prevent the penetration of sunlight, so seagrasses and animals dependent upon this vegetation leave the area or die. And as algae decay, it robs the water of oxygen, and fish and shellfish die, replaced by species, often invasive, that tolerate pollution.

While these nutrient-charged events remain a problem, she said, the overall habitat of the Seekonk River is improving. Kiernan noted that in recent years some 20 species of fish, including bluefish, black sea bass, striped bass, scup, and tautog, have been documented in the river.

The Seekonk River is still a stressed system, but Kiernan said the river is seeing a positive trend in its recovery.

“We’re not in a position to suggest that its been fully restored, and honestly I don’t think that we’ll be in a position to do that until we get the CSO abatement program further implemented,” she said. “But I think you can take some satisfaction in knowing that there are days where things look OK out there.”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Annie Sherman: Offshore wind turbines can benefit fishing

Wind turbines of Denmark

Since the Block Island Wind Farm, four years ago, pioneered U.S. offshore wind development, the United States has positioned itself to become a world producer of electricity in this renewable-energy sector. Turning the wind’s kinetic energy into electrical power is gaining popularity, so much so that 2,000 offshore wind turbines could be erected off the East Coast in the next 10 years.

But with growth comes questions and resistance, so scientists and environmental advocates across the country and in Rhode Island are seeking opportunities to expand offshore renewable energy while reducing environmental risks.

With world-class fisheries and wildlife in Ocean State waters, the potential for victory seems on par with ruin. So it’s vital to understand how the trifecta interacts symbiotically: offshore wind facilities, current recreational and commercial uses, and the existing ecosystem.

“As we experience this growth, we see that the state and local decision-makers, resource users, and other end users are struggling to keep up with the decisions they’re having to make and also understand the potential impact it may have on existing activities and natural wildlife,” said Jennifer McCann, director of U.S. coastal programs at the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center. “While some places in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Europe have been working in this game for many years, there are others who are just beginning to ask questions and get their bearings on this growth. Given this growth is likely, [we need to] better understand how can we minimize the effects on existing future uses and wildlife.”

The development of offshore renewable energy has already exploded in Europe. WindEurope estimates that it now has offshore wind capacity of 22.1 gigawatts from 5,047 grid-connected offshore wind turbines across 12 countries, with 502 turbines installed last year alone. Scientists and researchers there already are coming to terms with the risk and impacts, both positive and negative, of offshore wind turbines.

Sharing their knowledge about the U.S. market in a June webinar, moderated by McCann, with Rhode Island Sea Grant and URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography, two experts said the impacts on the environment are steep. They advocated for proper management and reduced activity to maintain a healthy marine environment.

Jan Vanaverbeke, a senior scientist at the Royal Belgian Institute for Natural Sciences, and Emma Sheehan, a senior research fellow at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom, presented more than a decade of research from investigating the change in biological diversity and ecological interactions resulting from offshore renewable-energy structures.

Their research began at the smallest scale, with tiny marine animals and microorganisms inhabiting a turbine when it’s first installed, Vanaverbeke said. Huge numbers of this diverse marine life make a home at the base of these 600-foot-high, 200-ton turbines affixed to the seabed. This area also attracts other animals such as fish and crustaceans. They noted how offshore aquaculture and offshore energy infrastructure can support each other and improve the diversity of marine ecosystems.

“Abiotic effects, like currents, vibration, noise, and electromagnetic fields, will have an affect on the biology,” Vanaverbeke said. “In this case, it would deliver food for society, because certain fish species, like cod and pouting, were attracted to turbines. … What we see in the scour protection layer [a layer of material to protect erosion around the turbine] shows increased diversity, giving additional complexity and shelter for species.”

He also saw evidence of this conflicted cause-and-effect relationship when additional marine animals were drawn to the turbines, as they affected sediment and water quality. Taking organic matter and food from the water, they also excrete matter, which sinks to the seabed and negatively alters the sedimentary environment.

“Offshore wind farms actually do change the habitat and the environment,” Vanaverbeke said. “Research will inform you of consequences of those changes, and how to understand what this change will mean for the larger marine ecosystem. We actually want to apply this knowledge for marine spatial planning. We can see where to put the wind farm, where is the best place from an ecosystem perspective. We have to know about carrying capacity for aquaculture activities. We can also use this knowledge for a better wind farm design, in such a way that they would contribute to nature restoration and conservation, or we can play around with the complexity of the scour protection layer and use it as a nature restoration tool.”

Sheehan expanded on their research with her analysis of ecological interactions between offshore installations and the potential benefits of ambitious management. Highlighting Marine Protected Areas (MPA), a fresh or saltwater zone that is restricted to human activity, Sheehan focused on ecosystem-based fisheries management and offshore installations that have the potential to be super MPAs, by excluding destructive fishing practices and adding habitat.

She noted the term “ocean sprawl,” similar to urban sprawl, which is becoming more widely known as pressure increases for offshore energy installations.

Sheehan said it’s important to consider the benthos and their associated fish communities, because they are the foundation for the entire marine ecosystem.

Reducing or eliminating bottom fishing, which she said is destructive of rocky reefs and sediment habitats, is one way to protect these important marine areas. In one MPA she has been studying for 13 years, scallop dredging was prohibited, which ultimately allowed reef-associated species to return.

Since the siting of most offshore wind facilities is on these habitats, Sheehan advocated for installations to be progressively managed like de facto MPAs, to support essential fish habitats and protect the seabed.

“There is lots of potential for environmental benefit of co-locating offshore aquaculture with offshore renewables from an environmental point of view, but also from an economic point of view, because sharing space is going to be the only way we can move forward for this industry,” Sheehan said. “If bottom-towed fishing is excluded from the whole site, offshore developments can have positive effects on the ecosystem, increase ecosystem services, support other fisheries, and help us move toward a carbon-neutral society.”

Annie Sherman is a freelance journalist based in Newport, R.I., covering the environment, food, local business, and travel in the Ocean State and New England. She is the former editor of Newport Life magazine, and author of Legendary Locals of Newport.

Invasive little pet turtles

Red-Eared Sliders

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

They are the most popular pet turtle in the United States and available at pet shops around the world, but because Red-Eared Sliders live for about 30 years, they are often released where they don’t belong after pet owners tire of them. As a result, they are considered one of the world’s 100 most invasive species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Southern New England isn’t immune to the problems they cause.

“I hear the same story again and again,” said herpetologist Scott Buchanan, a wildlife biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. “‘We bought this turtle for a few dollars when Johnny was 8, he had it for 10 years and now he’s going to college, so we put it in a local pond.’ That’s been the story for hundreds and thousands of kids in recent decades.”