Cake makes it a party

Julia Child in her kitchen in 1978

“A party without cake is just a meeting.’’

— Julia Child (1912-2004), the very tall, cheery, warbly and down-to-earth American TV personality, cooking teacher and book author whose show The French Chef (1963-1973), produced by WGBH TV in Boston, near her home in Cambridge, became one of the most popular shows in the history of public TV.

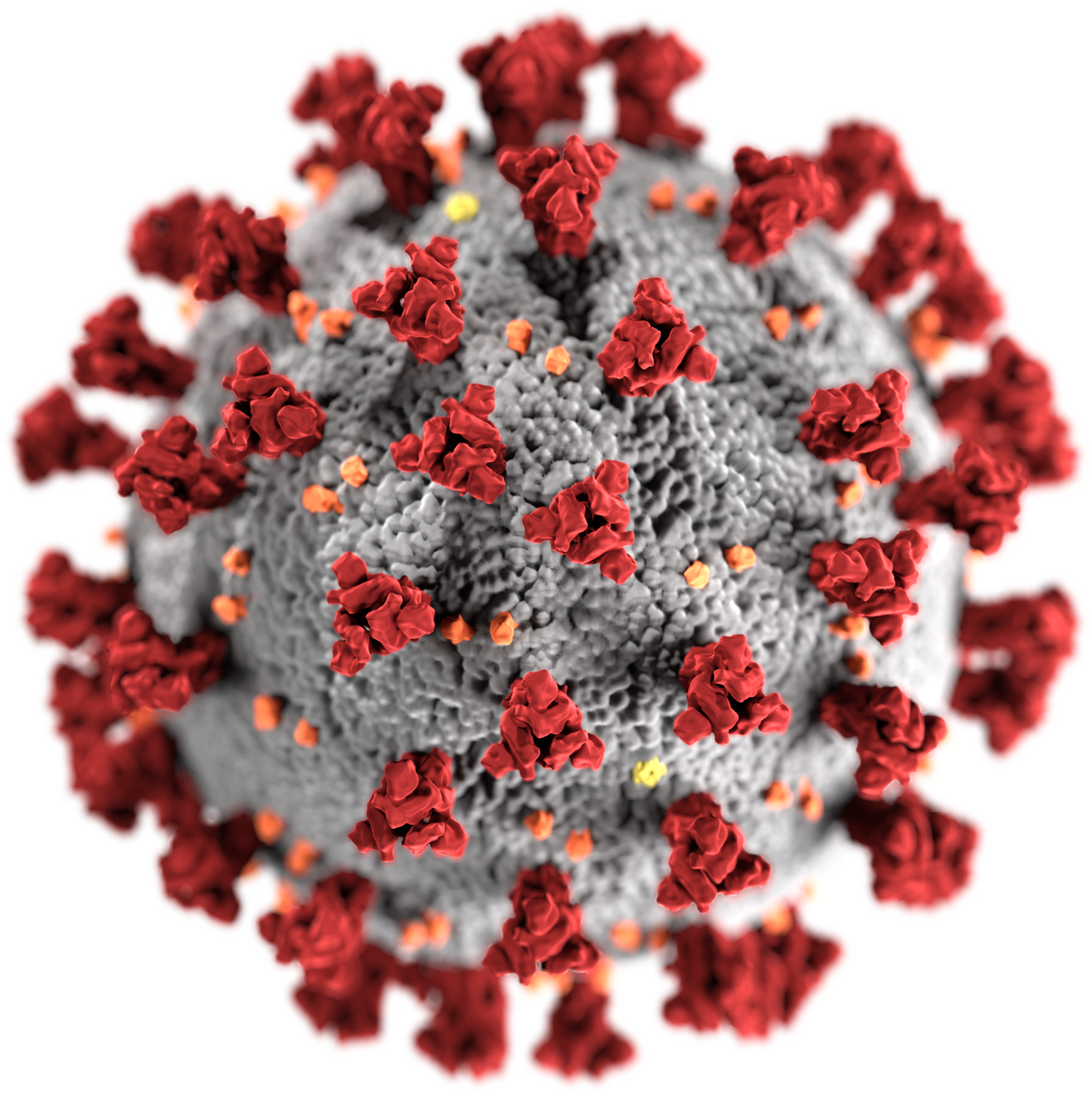

Have one of the COVID-19 variants? They won't tell you

Covid-19 infections from variant strains are quickly spreading across the U.S., but there’s one big problem: Lab officials say that they can’t tell patients or their doctors whether someone has been infected by a variant.

Federal rules around who can be told about the variant cases are so confusing that public health officials may merely know the county where a case has emerged but can’t do the kind of investigation and deliver the notifications needed to slow the spread, according to Janet Hamilton, executive director of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists.

“It could be associated with a person in a high-risk congregate setting or it might not be, but without patient information, we don’t know what we don’t know,” Hamilton said. The group has asked federal officials to waive the rules. “Time is ticking.”

The problem is that the tests in question for detecting variants have not been approved as a diagnostic tool either by the Food and Drug Administration or under federal rules governing university labs ― meaning that the testing being used right now for genomic sequencing is being done as high-level lab research with no communication back to patients and their doctors.

Amid limited testing to identify different strains, more than 1,900 cases of three key variants have been detected in 46 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s worrisome because of early reports that some may spread faster, prove deadlier or potentially thwart existing treatments and vaccines.

Officials representing public health labs and epidemiologists have warned the federal government that limiting information about the variants ― in accordance with arcane regulations governing clinical labs ― could hamper efforts to investigate pressing questions about the variants.

The Association of Public Health Laboratories and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists earlier this month jointly pressed federal officials to “urgently” relax certain rules that apply to clinical labs.

Washington state officials detected the first case of the variant discovered in South Africa this week, but the infected person didn’t provide a good phone number and could not be contacted about the positive result. Even if health officials do track down the patient, “legally we can’t” tell him or her about the variant because the test is not yet federally approved, Teresa McCallion, a spokesperson for the state department of health, said in an email.

“However, we are actively looking into what we can do,” she said.

Lab testing experts describe the situation as a Catch-22: Scientists need enough case data to make sure their genome-sequencing tests, which are used to detect variants, are accurate. But while they wait for results to come in and undergo thorough reviews, variant cases are surging. The lag reminds some of the situation a year ago. Amid regulatory missteps, approval for a covid-19 diagnostic test was delayed while the virus spread undetected.

The limitations also put lab professionals and epidemiologists in a bind as public health officials attempt to trace contacts of those infected with more contagious strains, said Scott Becker, CEO of the Association of Public Health Laboratories. “You want to be able to tell [patients] a variant was detected,” he said.

Complying with the lab rules “is not feasible in the timeline that a rapidly evolving virus and responsive public health system requires,” the organizations wrote.

Hamilton also said telling patients they have a novel strain could be another tool to encourage cooperation ― which is waning ― with efforts to trace and sample their contacts. She said notifications might also further encourage patients to take the advice to remain isolated seriously.

“Can our investigations be better if we can disclose that information to the patient?” she said. “I think the answer is yes.”

Public health experts have predicted that the B117 variant, first found in the United Kingdom, could be the predominant variant strain of the coronavirus in the U.S. by March.

As of Feb. 23, the CDC had identified nearly 1,900 cases of the B117 variant in 45 states; 46 cases of B1351, which was first identified in South Africa, in 14 states; and five cases of the P.1 variant initially detected in Brazil in four states, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the CDC director, told reporters Wednesday.

A Feb. 12 memo from North Carolina public health officials to clinicians stated that because genome sequencing at the CDC is done for surveillance purposes and is not an approved test under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program ― which is overseen by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ― “results from sequencing will not be communicated back to the provider.”

Earlier this week, the topic came up in Illinois as well. Notifying patients that they are positive for a covid variant is “not allowed currently” because the test is not CLIA-approved, said Judy Kauerauf, section chief of the Illinois Department of Public Health communicable disease program, according to a record obtained by the Documenting COVID-19 project of Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation.

The CDC has scaled up its genomic sequencing in recent weeks, with Walensky saying the agency was conducting it on only 400 samples weekly when she began as director compared with more than 9,000 samples the week of Feb. 20.

The Biden administration has committed nearly $200 million to expand the federal government’s genomic sequencing capacity in hopes it will be able to test 25,000 samples per week.

“We’ll identify covid variants sooner and better target our efforts to stop the spread. We’re quickly infusing targeted resources here because the time is critical when it comes to these fast-moving variants,” Carole Johnson, testing coordinator for President Biden’s covid-19 response team, said on a call with reporters this month.

Hospitals get high-level information about whether a sample submitted for sequencing tested positive for a variant, said Dr. Nick Gilpin, director of infection prevention at Beaumont Health, in Michigan, where 210 cases of the B117 variant have been detected. Yet patients and their doctors will remain in the dark about who exactly was infected.

“It’s relevant from a systems-based perspective,” Gilpin said. “If we have a bunch of B117 in my backyard, that’s going to make me think a little differently about how we do business.”

It’s the same in Washington state, McCallion said. Health officials may share general numbers, such as 14 out of 16 outbreak specimens at a facility were identified as B117 ― but not who those 14 patients were.

There are arguments for and against notifying patients. On one hand, being infected with a variant won’t affect patient care, public health officials and clinicians say. And individuals who test positive would still be advised to take the same precautions of isolation, mask-wearing and hand-washing regardless of which strain they carried.

“There wouldn’t be any difference in medical treatment whether they have the variant,” said Mark Pandori, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory. However, he added that “in a public health emergency it’s really important for doctors to know this information.”

Pandori estimated there may be only 10 or 20 labs in the U.S. capable of validating their laboratory-based variant tests. One of them doing so is the lab at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Alex Greninger, assistant director of the clinical virology laboratories there, who co-created one of the first tests to detect SARS-CoV-2, said his lab began work to validate the sequencing tests last fall.

Within the next few weeks, he said, he anticipates having a federally authorized test for whole-genome sequencing of covid. “So all the issues you note on notifying patients and using [the] results will not be a problem,” he said in an email.

Companies including San Diego-based Illumina have approved covid-testing machines that can also detect a variant. However, since the add-on sequencing capability wasn’t specifically approved by the FDA, the results can be shared with public health officials ― but not patients and their doctors, said Dr. Phil Febbo, Illumina’s chief medical officer.

He said they haven’t asked the FDA for further approval but could if variants start to pose greater concern, like escaping vaccine protection.

“I think right now there’s no need for individuals to know their strains,” he said.

Until it isn't

“When Everything is Uncertain, Anything Is Possible” (paper, gesso, watercolor, tape, oil, acrylic, graphite, charcoal, pigment, oil bar on distressed paper, about 13.5 x 7 feet), by Dell Hamilton, at the Brookline (Mass.) Arts Center.

Where politics met commerce

Boston City Hall and Old Suffolk County Courthouse in 1860. It served as City Hall in 1841 to 1865.

Philip K. Howard: Public-employee unions have been a disaster for democracy and the public interest

The NEA is the largest union in the United States.

It’s time to rethink the role of public-employee unions in democratic governance.

Public-union intransigence has contributed to two of the most socially destructive events in the COVID-19 era. Rebuilding the economy after the pandemic ends also will be more difficult if state and local governments have to abide by featherbedding and other artificial union mandates.

Public-employee unions are politically impregnable, but their corrosion of first principles of democratic governance may leave them open to constitutional attack.

The lack of accountability imposed by union contracts has corroded democratic trust. The nearly nine-minute suffocation of George Floyd by Minneapolis policeman Derek Chauvin, every second shown on video, touched off protests around the country and social anger that may impact race relations for years.

But Chauvin should not have been on the job, and he likely would have been terminated or taken off the streets if police supervisors in Minneapolis had had the authority to make judgments about unsuitable officers. Chauvin had 18 complaints filed against him and a reputation for being “tightly wound,” not a good trait for someone carrying a loaded gun.

But police union contracts make it very difficult to terminate officers. Out of 2,600 complaints against police in Minneapolis since 2012, only 12 resulted in any sort of discipline and no officers were terminated. A 2017 report on police abuse nationwide revealed that union contracts make it extremely difficult to remove officers with a repeated history of abuse.

Teachers unions wield similar power. Dismissing a teacher, as one school superintendent told me, is not a process, it’s a career. California ranks near the bottom in school quality but is able to dismiss only two out of 300,000 teachers in a typical year.

Because of COVID-19, teachers unions have adamantly refused to allow teachers to return to work for a year, harming millions of students.

Because many parents can’t work if children are not in school, teachers unions are also impeding our ability to reopen the economy.

Yet most parochial and private schools in the U.S. have reopened, without serious consequences, as have schools in Europe. It is safe to reopen schools, according to the Centers for Disease Control, as long as teachers and students follow certain protocols. Unions now say they’ll put a toe in the water, starting in the spring, when another school year is almost over.

The bottom line is inescapable: Public-employee unions do not serve the public's best interests.

How did public-employee unions turn into public enemies? Until the 1960s, collective bargaining was not lawful in government — it’s hardly in the public interest to give public employees power to negotiate against the public interest.

As President Franklin Roosevelt put it: “The process of collective bargaining… cannot be transplanted into the public service…. To prevent or obstruct the operations of Government …. by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.”

Public-employee union power is largely an accident of history, one of the many unintended effects of the 1960s rights revolution. The first shoe to drop was Executive Order 10988, in which President John F. Kennedy, as payback for political support, permitted collective bargaining for federal employees.

Public unions soon demanded similar rights from states. Without any serious debate, New York in 1967 permitted collective bargaining, followed by California in 1968.

Unions gained strength with every new administration. The rhetoric was virtuous: Who can be against the rights of public employees? But the velvet glove of rights barely disguised the political iron fist.

Public employees represent almost 15 percent of the work force, probably the largest organized voting bloc. For more than 50 years, generations of political leaders have promised whatever it would take to get their support, including shields against accountability and rich pensions and benefits. In Illinois, a state now actuarily insolvent, 20,000 public employees enjoy pensions of more than $100,000 per year.

A political solution is almost impossible. Union contracts have long tails, tying the hands of successive political leaders. Their political power also is different from that held by other interest groups; political leaders are powerless without their cooperation.

As labor leader Victor Gotbaum once put it, “We have the ability, in a sense, to elect our own boss.”

Public unions wield this power not just to get benefits, but to dictate how government works. After 80 meetings trying to cajole teachers back to work, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot concluded that “they’d like to take over not only Chicago Public Schools, but take over running the city government.”

Democracy can’t work if elected officials lack the ability to run government. As James Madison put it, democracy requires an unbroken “chain of dependence… the lowest officers, the middle grade, and the highest, will depend, as they ought, on the President.” By shackling political leaders with thick contracts, and eviscerating accountability for cops and teachers, public unions have removed a keystone of democratic governance.

Public unions are not a problem anticipated by the framers of the Constitution. But Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution provides that “the United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government.” Known as “the Guarantee clause,” the provision has never been asserted in this context.

The history of the clause suggests that, by guaranteeing “a republican form of government,” the framers meant to ensure that government would be accountable to voters and not to a monarch or other unaccountable power.

Public unions have severed a key link between voters and governance. They are immune from accountability, collect tribute in the form of featherbedding work rules and excessive pensions, and control what they do day-to-day instead of what voters need.

It is time for a reckoning. The abuses of rogue police, teachers who won’t teach, and other indefensible public union controls cry out for constitutional redress.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, author, civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder of Campaign for Common Good and chairman of Common Good (commongood.org), a nonprofit legal- and regulatory-reform organization.

His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left.

This column first ran in USA Today.

Full disclosure: The editor of New England Diary, Robert Whitcomb, has collaborated with his friend Mr. Howard in some Common Good projects.

Port Authority Police Benevolent Association, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., a typical small-town police union.

'Far and Near'

Mary Dorsey Brewster (left image) and Warren Jagger (right image) in their joint show , “Far & Near,’’ at the Providence Art Club through March 5.

The future of work and Greater Boston's 'meds and eds'

Downtown Boston: Who will fill those now mostly vacant offices?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Last November, Bill Gates predicted that half of business travel and 30 percent of “days in the office” would disappear forever. Meanwhile, the McKinsey Global Institute says that a mere 20 percent of business travel won’t return and about 20 percent of workers might be working from home indefinitely. Whomever you believe, all this means far fewer jobs at hotels, restaurants and downtown shops, even as the pandemic has speeded the automation of (i.e., killing of) many office jobs (including home office jobs) and more factory jobs.

So what can government do to train people for new, post-pandemic jobs, assuming that there will be many? How can vocational and other schools be brought into this project? The trades – electricians, plumbers, carpenters, roofers, plasterers, etc., will probably have the most secure, and generally well compensated, jobs going forward, along with physicians, dentists and nurses as well as engineers of all sorts and computer-software and other techies.

Another part of the jobs package should be a WPA-style program to rebuild America’s infrastructure, which the drive for lower taxes and higher short-term profits has dangerously eroded. (See Texas again.) This has undermined the nation’s long-term economic health. Such a program could also serve to train many people in new, post-pandemic skills that would be useful even as automation accelerates.

Of course there will always be jobs available for very low-paid personal-help people, such as home health-care workers. Indeed, the aging of the population means that we’ll need a lot more of them

Andrew Yang, an entrepreneur who ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, made addressing the looming threat of automation-caused job losses a key part of his campaign, which he suspended before the pandemic. He has proposed giving Americans a $12,000-a-year “basic income’’ to help get them through the developing employment implosion. It may come to that….

Meanwhile, “meds and eds’’ – Greater Boston’s (of which Rhode Island is on the edge) dense medical, technological and higher-education complexes – will help save it at least from the worst of the long-term economic disruption caused by the pandemic. Much research must be done by teams in labs; technological breakthroughs require a lot of in-person collaboration, and most college students will continue to want and need in-person teaching. Further, Greater Boston is an international venture-capital and company start-up center. These high-risk activities also require a lot of in-person, look-‘em-in-the-eye work.

On the other hand, Boston’s banks and its famed retirement-investment companies, such as Fidelity, will never have as many employees working in its offices as before COVID-19; nor will its innumerable law firms. Many offices in high rises in downtown Boston (and Providence) will remain empty for a long time while architects, engineers and interior designers try to figure o

The very direct Bette Davis

Bette Davis often played unlikable characters, such as Regina Giddens in The Little Foxes (1941).

“When a man gives his opinion, he’s a man. When a woman gives her opinion, she’s a bitch.’’

xxx

“If you’ve never been hated by your child, you’ve never been a parent.’’

Bette Davis (1908-1989), a mega star of “The Golden Age of Hollywood.’’ Born and educated in Massachusetts, she remained very much a New Englander in manner. Her last husband, out of four, was the actor Gary Merrill, with whom she starred in the famous film All About Eve (1950). They were divorced in 1960 after a decade of marriage after having lived together for much of the 1950s in a mansion in Cape Elizabeth, Maine. After the divorce, she left the Pine Tree State but Mr. Merrill mostly remained there and indeed became very active in Maine politics.

Memorable Davis movie lines:

“What a dump!’’ in Beyond the Forest (1949)

”Fasten your seatbelts; it’s going to be a bumpy night’’ — in All About Eve (1950)

Cape Elizabeth Lights, Cape Elizabeth, Maine

— Photo by Stefan Hillebrand

Roger Warburton: An affordable plan to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions

The shore of Easton’s Point, in Newport. The neighborhood is very vulnerable to flooding associated with global warming.

— Photo by Swampyank

From ecoRI. org

NEWPORT, R.I.

It has been known for sometime that a reduction in greenhouse gases would have significant public-health benefits: less pollution means fewer deaths, fewer emergency room visits, and a better quality of life.

It’s also well known that reducing greenhouse gases would decrease the financial damages from hurricanes and storms, from droughts, and from coastal flooding.

The question, until now, has been: How do we pay for the necessary infrastructure changes?

A recent Princeton University study, Net-Zero America, presents a practical and affordable plan for the United States to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050.

Although it’s a massive effort, the plan is affordable because it only demands expenditures comparable to the country’s historical spending on energy.

“We have to immediately shift investments toward new clean infrastructure instead of existing systems,” according to Jesse Jenkins, one of the project’s leaders.

The plan is also practical, because it uses existing technology. No magic tricks are required.

The plan is also remarkably detailed with analyses at the state and, sometimes, at the county level. For example, the report includes an estimate of the increase in jobs in Rhode Island if the plan were to be implemented.

In nearly all states, job losses in the fossil-fuel industry are more than offset by an increase in construction and manufacturing in the renewable-energy sector.

The motivation behind the recent study is clear: Climate change is “the most dangerous of threats” because it “puts at risk practically every aspect of our material well-being — our safety, our security, our health, our food supply, and our economic prosperity (or, for the poor among us, the prospects for becoming prosperous).”

The challenges are not underestimated: the burning coal, oil, and natural gas supply 80 percent of our energy needs and more than 60 percent of our electricity. Their greenhouse-gas emissions can’t be easily reduced or inexpensively captured and sequestered away.

The plan

The Net Zero America study details the actions required to achieve net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050. That goal is essential to avert the costly damages from the climate crisis.

The study highlighted six pillars needed to support the transition to net-zero:

End-use energy efficiency and electrification/consumer energy investment and use behaviors change (300 million personal electric vehicles and 130 million residences with heat pump heating).

Cleaner electricity (wind and solar generation and transmission, nuclear, electric boilers and direct air capture).

Bioenergy and other zero-carbon fuels and feedstocks (hundreds of new conversion facilities and 620 million t/y biomass feedstock).

Carbon dioxide capture, utilization, and storage (geologic storage of 0.9 to 1.7 giga tons CO2 annually and capture at some 1,000 facilities).

Reduced non-CO2 emissions: (methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorocarbons).

Enhanced land sinks (forest management and agricultural practices).

One of the study’s key findings is that in the 2020s all scenarios create about 500,000 to 1 million new energy jobs across the country. There are net job increases in nearly every state.

The pathways

The plan outlines five distinct technological pathways that all achieve the 2050 goal of net-zero emissions.

The authors don’t conclude which of the pathways is “best,” but present multiple, affordable options. All pathways only require investment and spending on energy in line with historical U.S. expenditures; around 4 percent to 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The five pathways are:

High electrification: Aggressively electrifying buildings and transportation, so that 100 percent of cars are electric by 2050.

Less high electrification: This scenario electrifies at a slower rate and uses more liquid and gaseous fuels for longer.

More biomass: This allows much more biomass to be used in the energy system, which would require converting some land currently used for food agriculture to grow energy crops.

All renewables: This is the most technologically restrictive scenario. It assumes no new nuclear plants would be built, disallows below-ground storage of carbon dioxide, and eliminates all fossil-fuel use by 2050. It relies instead on massive and rapid deployment of wind and solar and greater production of hydrogen.

Limited renewables: This constrains the annual construction of wind turbines and solar power plants to be no faster than the fastest rates achieved in the United States in the past but removes other restrictions. This scenario depends more heavily on the expansion of power plants with carbon capture and nuclear power.

In all five scenarios, the researchers found major health and economic benefits. For example, reducing exposure to fine particulate matter avoids 100,000 premature deaths, which is equivalent to nearly $1 trillion in air pollution benefits, by midcentury compared to the “business-as-usual” pathway.

Wind and solar power, along with the electrification of buildings — by adding heat pumps for water and space heating — and cars, must grow rapidly this decade for the nation to be on a net-zero trajectory, according to the study. The 2020s must also be used to continue to develop technologies, such as those that capture carbon at natural-gas or cement plants and those that split water to produce hydrogen.

“The current power grid took 150 years to build. To get to net-zero emissions by 2050, we have to build that amount of transmission again in the next 15 years and then build that much more again in the 15 years after that. It’s a huge change,” according to Jenkins.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Net-Zero American, E. Larson, C. Greig, J. Jenkins, E. Mayfield, A. Pascale, C. Zhang, J. Drossman, R. Williams, S. Pacala, R. Socolow, EJ Baik, R. Birdsey, R. Duke, R. Jones, B. Haley, E. Leslie, K. Paustian, and A. Swan, Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts, interim report, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., Dec. 15, 2020.

David Warsh: An old man against the world; don't eat WSJ baloney on Texas crisis

Rupert Murdoch

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper chose a good week in which to write about a leading skeptic of climate change. “For all the anxiety about fake news on social media,” Kuper wrote last weekend, “disinformation on climate seems to stem disproportionately from one old man using old media.”

He meant Rupert Murdoch, 89, whose company, News Corp., owns The Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, The Times of London, and half the newspaper industry in Australia. Honored with a lifetime achievement award in January by the Australia Day Foundation, a British organization, Murdoch posted a video:

“For those of us in media, there’s a real challenge to confront: a wave of censorship that seeks to silence conversation, to stifle debate, to ultimately stop individuals and societies from realizing their potential. This rigidly enforced conformity, aided and abetted by so-called social media, is a straitjacket on sensibility. Too many people have fought too hard in too many places for freedom of speech to be suppressed by this awful ‘woke’ orthodoxy.”

There is some truth in that, of course – but not enough to justify the misleading baloney on the cause of crisis in Texas which the editorial pages of the WSJ published last week.

Murdoch is a canny newspaperman, and since acquiring The WSJ, in 2007, he has the good sense not to tamper overmuch with its long tradition of sophistication and sobriety in its news pages. He even replaced the man he had put in charge of the paper, Gerard Baker, after staffers complaints that Baker’s thumb was found too frequently on the scale of its coverage of Donald Trump.

Then again, neither has he tinkered with the more controversial traditions of the newspaper’s editorial opinion pages, to which Baker has since been reassigned as a columnist. The story has often been told about how managing editor Barney Kilgore transformed a small-circulation financial newspaper competing mainly with The Journal of Commerce in the years before World War II into a nationwide competitor to The New York Times, and worth $5 billion to Murdoch. A major contributor to it was Vermont Royster, editor of the editorial pages in 1958–71; and an occasional columnist for the paper for another two decades years after that. He was succeeded by Robert Bartley. Royster died in 1996.

In 1982, Royster characterized the beginnings of the change this way: “When I was writing editorials, I was always a little bit conscious of the possibility that I might be wrong. Bartley doesn’t tend to do that so much. He is not conscious of the possibility that he is wrong.”

Royster hadn’t seen anything yet. With every passing year, Bartley became firmer in his opinions. In the 1990s, his editorial pages played a leading role in bringing about the impeachment of President Clinton. Bartley died in 2002, and was succeeded by Paul Gigot, who has presided over a continuation of the tradition of hyper-confidence. The editorial page enthusiastically supported Donald Trump until the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol.

Last week the WSJ published four editorials on the situation in Texas.

Tuesday, A Deep Green Freeze: “[A[n Arctic blast has frozen wind turbines. Herein is the paradox of the left’s climate agenda: the less we use fossil fuels, the more we need them.”

Wednesday, Political Making of a Power Outage: “The Problem is Texas’s overreliance on wind power that has left the grid more vulnerable to bad weather than before.”

Thursday, Texas Spins in the Wind: “While millions of Texans remain without power for the third day, the wind industry and its advocates are spinning a fable that gas, coal, and nuclear plants – not their frozen turbines – are to blame.”

Saturday, Biden Rescues Texas with… Oil: “The Left’s denialism that the failure of wind power played a starring role in Texas catastrophic power outage has been remarkable”

Then on Saturday, the news pages weighed in, flatly contradicting the on-going editorial-page version of events with a thoroughly reported account of its own, The Texas Freeze: Why State’s Power Grid Failed: “The core problem: Power providers can reap rewards by supplying electricity to Texas customers, but they aren’t required to do it and face no penalties for failing to deliver during a lengthy emergency.

“That led to the fiasco that led millions of people in the nation’s second-most populous state without power for days. A severe storm paralyzed almost every energy source, from power plants to wind turbines, because their owners hadn’t made the investments needed to produce electricity in subfreezing temperatures.”

All three major American newspapers are facing major decisions in the coming year: Amazon’s Jeff Bezos must replace retiring executive editor Martin Baron at The Washington Post; New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger presumably will name a successor to executive editor Dean Baquet, who will turn 65 in September (66 is retirement age there); and Murdoch will presumably replace Gigot, who will be 66 in May.

The WSJ editorial page could play an important role in American politics going forward by sobering up. But only if Murdoch – or, more likely, his eldest son, Lachlan, who turns 50 this autumn – selects an editor who writes sensibly, conservatively, about dealing with climate change.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Editor’s note: Both Mr. Warsh and New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, are Wall Street Journal alumni.

Inviting uplands

Looking east toward the Berkshires from the New York line. The Berkshires are called “Hills’’ or “Mountains’’. We favor “Hills’’

— Photo by BenFrantzDale~commonswiki

“The mountains,

while not as Grand as

the Rockies or as

Splendored as the

Sierras, nonetheless,

were inviting.

Friendly, not intimidating.

Old pals, not forbidding

strangers.

They shouted 'Climb Us!’’’

— From “A New England Love,’’ by David Lessard

Chris Powell: Rich should pay more taxes, but to the Feds, not to Conn. and other states

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Having just gotten big raises amid an economic depression with horrible unemployment in Connecticut, the state employee unions have proclaimed that they won't consent to Governor Lamont's budget proposal to freeze state employee salaries for a while. The unions insist that state government should raise taxes on the wealthy so they pay their "fair share."

What is the "fair share" the wealthy should pay? "Fair share" advocates never provide any fixed calculation for it. That's because it is only whatever best facilitates raises for state and municipal government employees. For when raises for government employees are drawn from taxes on people who aren't so wealthy, there is always a political problem, as the non-wealthy seldom find it compelling to pay more to people who are already well paid.

But despite their comic self-interest, the state employee unions have a point about taxing the wealthy. For the emphasis of the federal government's economic policy during the virus epidemic has not been on sustaining the income of people who have lost jobs and business, though of course some federal aid has been sent their way. No, the federal government's emphasis has been on supporting financial-asset prices, as with the purchase of government and corporate debt and by intervening, often surreptitiously, in markets.

Since most financial assets are owned by the affluent and they are the ones with most of the capital gains accrued in the past year, their share of the nation's wealth has exploded while the share owned by ordinary working people has fallen. Federal government policy has been worsening income inequality and increasing the political influence of the wealthy.

It's not that the federal government needs tax revenue. It can create money for itself with abandon. Since they cannot create money, states and municipalities need it. But trillions of federal dollars seem to be on the way to states and municipalities, so their need is not really so great right now -- unless raises for state and municipal government employees are to take priority.

What's urgent is reducing income inequality and equalizing political influence. So since the federal government did the wealthy an expensive and unnecessary favor, there would be justice in raising their capital-gains taxes.

But the federal government is the place to do that, not state government in Connecticut, where taxes are already so high as to have been encouraging prosperous people to leave for many years, with the state steadily losing population relative to the rest of the country. Connecticut needs to be more competitive with taxes and the cost of living. Besides, any tax increase in Connecticut now will only diminish the incentive for Gov. Ned Lamont and the General Assembly to examine the expensive state policies that fail to achieve their nominal objectives.

For example, once again there is much clamor in the legislature to increase state grants to municipal schools. But 40 years of increasing those grants have failed to improve school performance. The grants have resulted only in higher pay for school employees. Legislators never ask what Connecticut gets for spending more in the name of education, presumably because they know that there is no relation between spending and school performance and that the only objective is to please the teacher unions.

Any inquiry into this might be revealing but also most impolitic so it will never happen.

Has raising state employee compensation improved services to the public? Of course nobody pretends that, but no legislators ever ask the question. Omitting state employee raises from his budget proposal, the governor shows he thinks state government can operate acceptably without another round of raises. His position is remarkable for a Democrat, since the state employee unions are his party's army. But then a salary freeze is only his opening position in a negotiation.

Legislators will be part of that negotiation and most legislators are tools of the unions, so odds are that once again state employees will get raises before more money is appropriated for the nonprofit social-service organizations whose employees do government work at half the cost of state employees and are almost dirt-poor.

But that's their own fault. They simply aren't as politically organized as the state employees are.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester.

‘Small-creature’s temperature’

The Old State House, a museum on the Freedom Trail near the site of the Boston Massacre

— Photo by Mobilus In Mobili

"Boston is not a small New York, as they say a child is not a small adult but is, rather, a specially organized small creature with its small-creature's temperature, balance, and distribution of fat. In Boston there is an utter absence of that wild electric beauty of New York, of the marvelous, excited rush of people in taxicabs at twilight, of the great Avenues and Streets, the restaurants, theatres, bars, hotels, delicatessens, shops. In Boston the night comes down with an incredibly heavy, small-town finality. The cows come home; the chickens go to roost; the meadow is dark. Nearly every Bostonian is in his house or in someone else's house, dining at the home board, enjoying domestic and social privacy.''

— Elizabeth Hardwick, in the December 1959 Harper’s Magazine.

Actually, in the two decades before COVID-19 struck, Boston became a lot more like New York. But the pandemic has made it more like Hardwick’s description.

The Old Corner Bookstore building in downtown Boston, built in 1718 as a residence and apothecary shop. It first became a bookstore in 1828.

In Vermont, artists responding to COVID-19

“Journey” (oil), by Irene Cole in the group show “Unmasked: Artful Responses to the Pandemic’,’ at Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester, Vt., through March 28. The show features the work of dozens of artists showing the struggles, breakthroughs and perspectives of the artists throughout the COVID-19 pandemic

“View of Manchester, Vermont,’’ by DeWitt Clinton Boutelle (1870). For many years, Manchester has been an affluent vacation and weekend spot, and with many fancy outlet and other shops.

Sign up now for last weeks of winter light

“Song of Winter Pool’’ (oil on linen) by Rory Jackson in his Edgewater Gallery show “Blanket of Stillness: Winter in the Mad River Gallery’’ at the Pitcher Inn, Warren, Vt., through March 22. Edgewater (based in Middlebury, Vt.) says Mr. Jackson “captures the unique beauty of the low winter light on the open fields, slopes, forests and mountains of (Vermont’s) Mad River Valley.’’

Lincoln Peak, West View (oil on linen)

In 1910

Old kitchen aroma

“The aroma {in the Maine farm kitchen} was a combination of wood smoke and hot iron, lingering cookery, drying mittens and socks, warming boots, barn clothes, wintering geraniums on the window sills, and the relaxed effluence of a lazy beagle roasting under the stove.’’

—John Gould (1908-2003), in Next Time Around: Some Things Pleasantly Remembered (1983), about the author’s life in Maine

Not for liquids

“Containment Vessel,’’ by Stacey Piwinski, in the group show “The Chemistry of FiberLab: An Exploration of Fiber Arts,’’ at the Lexington (Mass.) Arts & Crafts Society, March 14-April 4.

The Buckman Tavern (built in 1709-1710 and now a museum), where Minutemen assembled before the Battles of Lexington and Concord, which took place on April 19, 1775. The battles marked the start of the American Revolutionary War.

The Minuteman statue in Lexington

Bob Lord: The era of trust fund trillionaires approaches as fortunes are shielded from gift and estate taxes

Estate in Los Angeles

From OtherWords.org

History doesn’t repeat itself, but sometimes, as the old Mark Twain line goes, it rhymes.

Take this year’s Forbes 400. If you listen close enough, you can hear echoes of the first Forbes list back in 1982 — you just have to turn it up about 100 notches.

Back in 1982, with Reaganomics in its infancy, the first Forbes list of America’s ultra-wealthy had just 13 billionaires on top. The two richest of these billionaires, Daniel Ludwig and Gordon Getty, held personal fortunes estimated in the $2 billion range. The other 11 billionaires on that first annual Forbes list clustered together at the $1 billion level.

Multiply that 1982 billionaire breakdown by 100 and you’d have something awfully close to the present list.

The nine current wealthiest Americans today — all white men — each hold a net worth above or rapidly approaching the $100 billion mark. Two of these “hectobillionaires,” Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, hold around $200 billion.

To what do we owe this awesome increase in billionaire fortune?

The substantial increase in America’s national wealth since 1982 partially explains it. But our nation’s total combined wealth has only jumped about ten-fold since 1982, from under $10 trillion then to a little over $100 trillion today. That increase pales in comparison to the 100-fold increase in the wealth of those at America’s economic summit.

This giant leap at our economic summit should worry us, especially once we start contemplating how a future verse of the Forbes list might sound.

A generation from now, if current rates of wealth concentration continue, we may have to turn the volume up a thousand times over 1982 levels to hear the Forbes list rhyme. The 1982 $1 billion standard will have become $1 trillion.

That future would rhyme with 1982 on another more insidious level as well. Back in 1982, almost all the grand fortunes on the initial Forbes list came largely as inherited hand-me-downs. Only two billionaires on the 1982 list, Daniel Ludwig and David Packard, could claim anything resembling “self-made” status.

But over recent decades, Republicans have hollowed out our estate- and gift-tax laws. Their legislating has allowed tax-avoidance planners to effortlessly pass billions from one generation to the next — and often to the next generation after that — without incurring tax liabilities.

One former Donald Trump economic adviser, Gary Cohn, infamously noted that “only morons pay estate tax.” We can condemn Cohn’s disparagement of wealthy Americans who choose not to engage in tax avoidance, but we can’t challenge his basic point: In the United States today, the estate tax has become essentially a voluntary levy.

Shady operators like the late Jeffrey Epstein got rich themselves, The New York Times has detailed, by exploiting trusts to shelter billions in their clients’ wealth from estate and gift taxes.

In 2013, the Washington Post reports, the now deceased Sheldon Adelson used similar maneuvers to avoid gift taxes on his transfer of $7.9 billion in trust to his children.

And the Forbes listing of the Mars family’s wealth, the Institute for Policy Studies has noted, indicates that two generations of Mars family grandees have now successfully done an end run around the federal estate tax.

With fortunes well into the billions passing virtually tax-free from one generation to the next, the era of trillionaire trust fund babies is fast approaching. Our leaders could prevent that era. All they need would be the courage to reform our broken estate- and gift-tax system.

Bob Lord is a Phoenix-based tax lawyer and an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Great Salt Pond battle goes on

Block Island, with the Great Salt Pond the body of water with many boats in the top middle.

— Photo by Timothy J. Quill

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

One look at an aerial photo of Block Island’s Champlin’s Marina, on ecologically fragile Great Salt Pond, shows that it’s already too big. And now, through a highly dubious mediated settlement that’s an (illegal?) end run around an earlier denial of the project, the business could build 170 feet further into the pond (which serves as a harbor). Champlin’s campaign to take over more of the Great Salt Pond sometimes seems to have gone on for centuries but it’s only been since 2003!

While affluent folks from the region might love having more places to tie up on the island, adding more boats would inevitably increase pollution in the Great Salt Pond.

Retired Rhode Island Supreme Court Chief Justice FrankWilliams brokered this deal in secret negotiations involving the state Coastal Resources Management Council and Champlin’s. State Atty. Gen. Peter Neronha is rightly looking into this suspicious agreement.