Subsidize your strengths

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

With all the government goodies used to lure big companies, it’s refreshing to see a little state government help for small local companies that have a comparative advantage. That advantage can stem from their location, in Rhode Island’s case being on the ocean.

I write here of two companies.

One is Quonset-based American Mussel Harvesters, an aquaculture company that raises mussels, oysters and clams in the Ocean State. Shellfish aquaculture has been hard hit by the pandemic because the products have been primarily sold to restaurants. But the Rhode Island Commerce Corporation decided on Jan. 29 to give the company a $50,000 grant to help design a new bagging system for two-pound bags to sell to individual customers. Restaurants have generally been buying 10-pound bags. Much of the restaurant sector will come back, albeit in different forms, when COVID fades, but certainly shellfish farmers need to diversify their customer base a lot.

Meanwhile, the Commerce Corporation is making a $49,972 grant also appropriate to the Ocean State: Helping Flux Marine, of East Greenwich, in a project to make electric outboard motors. There’s the green-energy aspect, of course, but there’s also that there wouldn’t be gasoline spills from these outboards.

Beats putting money into the local casino business, including its support system (e.g., IGT, the gambling-tech giant and partners with its pending 20-year, no-bid Rhode Island state contract). Casinos prey on lower-income people and send much of their money out of the region.

Movies pick up on it

“I don’t think violence on film breeds violence in life. Violence in life breeds violence in films.’’

— Robert Burgess Aldrich (1918-1983), scion of a very rich and powerful Rhode Island WASP family, he was a film director, writer and producer.

His movies include

Vera Cruz (1954), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), The Big Knife (1955), Autumn Leaves (1956), Attack (1956), What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), Hush...Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), The Flight of the Phoenix (1965), The Dirty Dozen (1967) and The Longest Yard (1974).

Todd McLeish: A proposal for 'freedom lawns'

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Few people put much thought into the soil beneath their feet, but Loren Byrne does. A professor at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, R.I., Byrne is an expert on urban soil ecology, and he worries that humans are changing the structural integrity of soils in urban environments and limiting the ability of plants and animals to live in and nourish the earth.

“Soil is easily overlooked and taken for granted because it’s everywhere,” he said. “We walk all over it and think of it as dirt that we can manipulate at our will. But the secret of soil is what’s happening with soil organisms and what’s happening with their interactions below ground that help regulate our earth’s ecosystems.”

Byrne contributed a chapter about urban soils to a report, State of Knowledge of Soil Biodiversity, issued last year by the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization. He discussed how the ecology of the soil changes as it is compacted during construction, paved over, chemically treated for lawns, and dug up and carried away.

“The main takeaway is that urbanization can potentially harm biodiversity, but our biggest current threat is ignorance,” he said. “We don’t understand enough about soil biodiversity in urban environments, so we may not be able to manage it in ways to provide the benefits that are possible.”

Soil is the foundation for terrestrial life, according to Byrne. It’s the medium in which plants are grown and it regulates the nitrogen cycle, sequesters carbon, and manages the flow of water. He said soils are fascinating because they contain the full range of life, from single-celled bacteria and fungi to animals of all varieties.

“If you’re patient enough to get down on your hands and knees and pull up some soil, you’ll see mites, springtails, isopods, millipedes, centipedes, spiders, ants, beetles,” Byrne said. “Some of them have negative popular connotations, but ecologically, if we can see them as having value, then that will help us maintain more sustainable landscapes.

“Changing our perspectives of what these organisms are doing in the ecosystem is important. They perform beneficial functions, like decomposition. I tell my students that if it wasn’t for this whole suite of biodiversity in our soils, we’d literally be up to our necks in dead stuff.”

Although it may seem counterintuitive, Byrne said urban soils contain the full range of biodiversity that is found in natural soils, and some research shows that they contain more organisms and a greater diversity than agricultural soils.

“A lot of urban habitat types, like lawns and little forest patches, are perennial, so they don’t face the same level of annual disturbance as agricultural fields,” he said. “And they have more organic matter in them, so that allows the food web to become more complex. Urban soils are home to a lot of organisms.”

He noted, however, that there is also a massive volume of degraded soil in urban areas that is compacted, trampled, over-fertilized, and removed and replaced with lower quality soil.

“It’s a very interesting dichotomy,” Byrne said. “There are some high-quality soils and other locations that have been severely negatively impacted where we would want to somehow improve them.”

How to improve degraded soils is the topic of Byrne’s latest research. Decompacting the soil and remediating pollution are important steps, but the key is the addition of organic matter.

“There’s been a wide diversity of organic matter sources that have been investigated, from basic garden compost to sewage sludge to bio-char, which is a burned organic matter that, when added to soil, provides good surfaces for microbes to live on,” he said. “But you have to be very careful about what you’re using and in what contexts and the source, because not all organic matter is the same.

“A lot of research has shown that adding organic matter will help remediate the soils in various ways. Organic matter holds onto water, so it helps with water issues, for instance. But in locations that are already prone to water-logging, adding organic matter could be a bad thing. So context matters. You need to be familiar with site specific issues to come up with a good management plan.”

Byrne focuses a great deal of his research attention on lawns, which he calls a “human-created ecosystem.” While he noted that a lawn provides a nice place for a picnic and is better than pavement, he said installing a lawn is the least biodiverse way of improving urban landscapes.

“The goal with a lawn is often one grass species that’s bright green and isn’t growing or reproducing, which is the exact opposite of what life wants to do,” he said. “In the grand scheme of all life, a place becomes more diverse over time, it grows and reproduces, and humans are trying to stop all of that in a lawn.

“The problem isn’t so much the lawn itself as the monoculture, pesticide-managed lawn. A lot of what ecologists advocate is a more biodiverse lawn where we let the so-called weeds grow and let the grass grow a little taller. That’s good for the soil ecosystem because a higher variety of plants and no chemical pesticides will allow more soil organisms to thrive.”

To create a more sustainable urban landscape, Byrne advocates for what some have called “freedom lawns” — a mowed lawn that maintains a high diversity of grasses and weeds and good soils.

“If we can convince people that it’s more patriotic to shift to freedom lawns, it will be more sustainable,” he said. “And if we can shrink the area of lawn by creating more biodiverse habitat through shrubs and wildflowers, that’s another step toward sustainability and biodiversity.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Don’t laugh at Rhode Island

Exchange Place, ca. 1890. City Hall at center; to its right is the First Union Station, where Burnside park currently exists. The area is now called Kennedy Plaza.

“I know not whether anyone, even in New York, is so hardy as to laugh at Rhode Island, where the spirit of Roger Williams still abides in the very dogs….The small commonwealth, with its stronger and fuller flow of life, is more native, more typical, and therefore richer in real instructions, than the large state can ever be.’’

—E.A. Freeman, in Some Impressions of the United States (1883)

The blessings of January

The Mt. Hope Bridge, connecting the Rhode Island mainland with Aquidneck Island

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s good that in January in these parts you see the underlying structures of many things, the skeletons of them, so to speak, with the leaves off the deciduous trees and other vegetation reduced, too. More architecture than painting. Another nice thing is that the colors of birds, e.g., cardinals, stand out more vividly against the brown, gray and white of January than they do in greener times.

Marshes in Sandwich, Mass.

— Photo by Andrewrabbott

I love the sere of coastal marshes at this time of year, especially at sunrise and sunset.

Of course, it’s also good to know that winter will end in a few weeks.

January always seemed to me a quiet time in which you can catch your breath, before obligations start piling up again later in the winter – tax returns, etc. It’s a good time to catch up on sleep.

We send out a lot of New Year’s cards well into this month. They arrive more reliably at their destinations than Christmas cards, especially this past holiday season, what with the pandemic and damage to the U.S. Postal Service by the Trump regime under its corrupt postmaster general, Louis DeJoy. (Being corrupt and slavishly, even criminally, loyal have often seemed to be the main requirements for high-level employment in this destructive regime.)

Driving to Newport on a bright winter’s day, with shimmering views from the bridges of the Ocean State’s archipelago, is exhilarating, as is sitting with an old friend at the all-weather patio of a mostly empty restaurant on the Newport waterfront with the light pouring in. But let’s hope that the eatery is crowded come spring.

Tim Faulkner: What next for Transportation Climate Initiative?

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The regional collaboration known as the Transportation & Climate Initiative (TCI) will be operating, at least initially, with a smaller cast than expected.

Governors from Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut, as well the District of Columbia’s mayor, signed an agreement Dec. 21 to launch an effort to address the climate crisis. This cap-and-invest system is designed to reduce climate emissions by raising money from the wholesale distribution of gasoline and diesel fuel and investing the proceeds in electric-vehicle infrastructure and other initiatives that make up the so-called “green transportation economy.”

TCI is composed of 13 East Coast states and the District of Columbia, but only the three states and the nation’s capital signed the recent memorandum of understanding to establish the revenue-generating system. Most other TCI member states had previously signed a separate letter expressing support for the program. Maine and New Hampshire didn’t sign on to that earlier letter. All TCI members can adopt the cap-and-invest program at any time.

During an online press call, no explanation was offered as to why the other states aren’t joining the pact. Representatives from the three states and the District of Columbia instead described how the anticipated reduction in climate emissions, along with the economic growth they expect, will entice states to eventually participate.

“This is a strong group moving forward in a committed way,” said Kathleen Theoharides, secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. “And we believe the future is bright and that if you build it they will come.”

Katie Scharf Dykes, commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection, predicted that TCI will increase state participation, as did another cap-and-invest program that generates revenue from power-plant emissions, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

“I’m confident that we will see more jurisdictions joining us,” Scharf Dykes said.

If local approvals are met, TCI is scheduled to launch in 2022 with a one-year trial reporting period that will track emissions for each state and the District of Columbia. Fossil-fuel distributors won’t have to buy the pollution allowances until 2023, when they are required for exceeding a monthly emission limit, or cap. The limit is reduced each year until 2032, when it will be 30 percent lower than the initial cap.

During the recent press call, representatives from the three states and District of Columbia touted the benefits of investing some $3.2 billion over nine years in electric buses, electric-vehicle charging infrastructure, and new bicycle lanes, walking trails, and sidewalks.

Some $3.2 billion will be invested in low-carbon transit projects in four regions over nine years. (TCI)

“Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and D.C. are committing to bold action to achieve our ambitious emission-reduction targets while positioning the jurisdictions and the region to grow our clean transportation economy,” Theoharides said.

The auction of the allowances is expected to raise about $300 million annually. Rhode Island anticipates receiving about $20 million a year. As part of the program, at least 35 percent of the proceeds must be invested in environmental-justice communities. Spending in these frontline communities is expected to create jobs, reduce air pollution, and improve public health.

If fuel distributors pass the cost on to consumers, the expense is expected to add between 5 and 9 cents to a gallon of fuel.

The program’s requirement for equity investment is intended to address the regressive nature of the higher fuel costs by investing in communities suffering from excessive air pollution. Statewide equity advisory boards comprised mostly of members from these communities will recommend where and how the TCI funding is spent.

“Most importantly, (TCI) will provide much-needed relief for the urban communities who suffer lifelong health problems as a result of dirty air,” Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo wrote in a prepared statement.

The program is expected to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions from the transportation sector by some 26 percent over nine years. Transportation accounts for 42 percent of all emissions among the signors, the largest source of emissions in those areas.

The announcement comes a year after TCI was expected to launch. TCI representatives blamed the delay on the heath crisis and an unfriendly White House administration. Public perception was also a likely cause for delay. Opposition to TCI from conservative news outlets and radio talk-show hosts has persisted.

Rhode Island acknowledged at a meeting in 2019 that TCI will take more than a government directive to succeed.

“If we’re going to win hearts and minds, it’s not just people at the Statehouse,” said Carol Grant, then director of the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources. “We have to kind of win people over generally to the importance of this.”

Back then, environmental groups criticized TCI for not advancing stronger reductions in emissions. Reaction to the recent announcement from the same environmental community has been positive. Support for the TCI program has been expressed by Save The Bay, Acadia Center, and the Northeast Clean Energy Council.

A new president committed to taking on climate change improved the prospects for enacting the TCI program, according to coalition members.

“With a change in administration, policies are going to be a lot more stable,” said Terrence Gray, deputy director for environmental protection at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Janet Coit, DEM’s executive director and the state’s representative during the online announcement, noted that states with Republican and Democratic governors are TCI members.

“After so much divisiveness, it’s really great to see bipartisan regional effort leading on climate change,” Coit said.

The public response to the program will likely determine the willingness of other states to join. A recent poll conducted by Yale University and George Mason University among voters in TCI states and the District of Columbia found that 41 percent said they strongly support participation in the initiative. Another 31 percent said they would somewhat support participation. Rhode Island had the highest support at 61 percent. Maine was the lowest at 56 percent. Politically, 84 percent of Democrats favored joining TCI, while 49 percent of Republican favored joining the initiative.

Public perception starts with messaging. The revenue mechanism is often referred to by opponents as a “gas tax” or fee paid by consumers. But it has several distinctions, according to the renewable-energy advocacy group Acadia Center.

First, some fuel-distribution companies may choose to internalize part or all of the allowance costs to gain a competitive advantage rather than pass it on to gas-station customers. And since TCI is based on the carbon content of a fuel, suppliers will be able to sell fuels with lower carbon contents and pay less in carbon pollution fees, according to Acadia Center.

“This program is about delivering benefits to consumers with a transition in fuels and mobility options over time,” said Hank Webster, staff attorney and Rhode Island director for Acadia Center.

TCI will have a minimal impact, if any, on fuel prices, Webster said, because the program is designed to keep that impact at or below 5 cents if regional fuel suppliers choose to pass the costs on to their customers.

“To put that in context, you can save 5 cents per gallon at some stations by using their frequent customer program, or 10 cents per gallon by setting up a direct debit from your checking account,” he said.

Rhode Island and Connecticut require legislative approval to launch the TCI program. Massachusetts can advance the program through its executive office.

Raimondo is expected to launch the legislative process this spring, with public input beginning in January.

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI News.

— Photo by Felix Kramer

Past time to go big

Block Island Wind Farm

Old Higgins Farm Windmill, in Brewster, Mass., on Cape Cod. It was built in 1795 to grind grain. Many New England towns had windmills.

“By partnering with our neighbor states with which we share tightly connected economies and transportation systems, we can make a more significant impact on climate change while creating jobs and growing the economy as a result.’’

-- Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker

Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island and the District of Columbia have signed a pact to tax the carbon in vehicle fuels sold within their borders and use the revenues from the higher gasoline prices to cut transportation carbon-dioxide emissions 26 percent by 2032. Gasoline taxes would rise perhaps 5 to 9 cents in the first year of the program -- 2022.

Of course, this move, whose most important leader right now is Massachusetts’s estimable Republican governor, Charlie Baker, can only be a start, oasbut as the signs of global warming multiply, other East Coast states are expected to soon join what’s called the Transportation Climate Initiative.

The three states account for 73 percent of total emissions in New England, 76 percent of vehicles, and 70 to 80 percent of the region’s gross domestic product.

The money would go into such things as expanding and otherwise improving mass transit (which especially helps poorer people), increasing the number of charging stations for electric vehicles, consumer rebates for electric and low-emission vehicles and making transportation infrastructure more resilient against the effects of global warming, especially, I suppose, along the sea and rivers, where storms would do the most damage.]

Of course, some people will complain, especially those driving SUVs, but big weather disasters will tend to dilute the complaints over time. Getting off fossil fuels will make New England more prosperous and healthier over the next decade. For that matter, I predict that most U.S. vehicles will be electric by 2030.

Eventually, reactionary politics will have to be overcome and the entire nation adopt something like the Transportation Climate Initiative.

Fishers are expanding into areas thick with humans

Fishers are powerful predators.

A fisher photographed in Topsfield, Mass.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

University of Rhode Island scientists have begun a three-year effort to capture and track fishers throughout western Rhode Island to better understand their population numbers and movement as the animals expand into more developed areas of the state.

Funded by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, the project aims to gather data about the secretive predators, which are members of the weasel family, so that they can be managed more effectively.

“It’s fascinating to me to see how this creature that was once known as a deep dark forest-dwelling animal is now living in people’s backyards and in urban settings,” said Laken Ganoe, a University of Rhode Island doctoral student who is leading the project along with assistant Prof. Brian Gerber. “It’s a unique landscape for us to study a creature that we don’t know much about.”

Fishers are carnivorous mammals found throughout the forests of the northern United States and Canada. Extirpated from Rhode Island when forests were cleared for agriculture in the 1700s and 1800s, they have returned in recent decades and appear to be expanding their range in the region. They feed primarily on small mammals such as chipmunks and squirrels, though in more northerly regions their preferred prey is snowshoe hares.

In Rhode Island, fishers are legally trapped for their fur by licensed trappers during a 25-day trapping season in December.

Ganoe will use trail cameras set up at 200 sites in Providence, Kent and Washington counties to document where the animals are found. She also plans to capture up to 20 fishers in each of the next three years and place tracking collars on them to monitor their movements and activity levels throughout the day.

“We hope to learn how fishers are interacting with their environment in this matrix of urban and forested landscape,” Ganoe said. “Are they spending more time out and about in urban areas at night while being more active at dusk and dawn in forested areas?”

The name fisher may have originated from the French word fitchet, fitche, or fitchew used to describe the European polecat that has similar characteristics to the fisher.

“Tracking individual fishers for the winter will get a really fine scale idea about how they cross roads, what forests they are selecting for, what areas they’re avoiding,” Gerber said. “If we do it right and we’re lucky, we’ll be able to estimate how many fishers there are in certain regions of Rhode Island.”

A native of Clarion, Pa., Ganoe earned a master’s degree at Pennsylvania State University and studied fishers in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California before enrolling at URI. She became interested in the animals as a teenager, when she watched as a fisher caught a chipmunk and ran up the tree from which she was hunting and ate it right beside her.

“There are a lot of misconceptions about fishers; they have a bad reputation,” Ganoe said. “We want to learn more about them so we can educate people about them. And because there is a trapping season for them, we want to inform future management decisions about bag limits and season lengths so we can properly manage the species.”

This is one of two research projects Gerber is leading that focus on learning more about Rhode Island’s mid-sized predators. The other is investigating the distribution of beavers, muskrats, and river otters in the state.

Grace Kelly: The bumpy road to R.I.’s East Bay Bike Path

Facing south near the East Bay Bike Path's southern terminus, in Bristol

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

“These days it’s hard to find someone who thinks creating the East Bay Bike Path was a foolish idea.” So begins a Providence Journal article written in 1999 by Sam Nitz, which chronicled the bike path’s beginnings and eventual completion.

The same could be said in 2020, a year when a pandemic forced people to get creative with their time. They took to the outdoors when the weather turned warm, with many dragging a set of wheels to a Rhode Island bike path that runs from Providence to Bristol.

I cruised along this path myself, dodging hand-holding couples, bold squirrels, and the occasional toddling roller-skater.

A map of the East Bay Bike Path from a 1984 pamphlet. Construction of the trail took place from 1987-92.

While looking at the path today might give the impression that it was a beloved idea all along, as Nitz noted in his article, “the path’s beginnings in the early 1980s were fraught with controversy and rancorous political debate.”

The 14.5-mile stretch of asphalt was hardly a shoo-in. In fact, it was met with raucous opposition, German shepherds, and even a letter to a high-level staffer of President Reagan begging for federal intervention.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The story of the East Bay Bike Path starts with an old stretch of railroad that connected Providence to Bristol, with stops in Riverside and Warren and a connecting line that went to Fall River, Mass. It was a handsome railway, with postcards and old photos depicting almost modern-looking platforms and stations — one particular image of the rail near the future Squantum Association, a private club in East Providence, could be from the 2000s.

But as automobiles began to capture the American spirit, the railway slowly faded into disuse and the passenger line ended in 1938. In 1976, the State of Rhode Island acquired the right of way for the old Penn Central line, the section that ran from East Providence to Bristol.

It would also be automobiles that would inspire Bristol state Rep. Thomas Byrnes Jr. in the late 1970s, to lead the charge to create a bike path on the old Penn Central line.

“When I started at the State House in ’78, the oil shortage was … tough,” said Byrnes in a 2002 interview with his daughter Judith. “People were driving bombers around and they were having a hard time keeping their cars filled with gas. So, they were talking about looking into alternative means of transportation to cut our use of oil.”

And one idea that came up: bicycles.

In the ’70s, the United States experienced a bicycle boom, with some 64 million Americans using bicycles regularly. A 1971 article in Time magazine noted that America was having “the bicycles biggest wave of popularity in its 154-year history.”

So, at the time when Byrnes started thinking about alternative methods of transportation, bicycles were everywhere, and other states such as Maryland were starting to investigate turning old railways into bike trails.

In March 1980, Byrnes and Matthew Smith, who was the Rhode Island speaker of the House at the time, wrote a joint bill that called for a study of bicycling as an alternative form of transportation and as an energy saver. The idea of the East Bay Bike Path was born.

What happened next was years of pushing through heated resistance.

“There was a lot of opposition, a lot of opposition,” said Robert Weygand, who was the chairman of the East Providence Planning Board in the early ’80s, and who later went on to be a U.S. congressman and Rhode Island lieutenant governor. “In every community there were people that came out opposed to it.”

Weygand became involved in the project through his work on the East Providence Planning Board and later as part of a group called Friends of the Bike Path. He saw its creation as a way to help restore East Providence’s once-rich history of activities and attractions along the water.

“We heard about what Tom [Byrnes] had been proposing for a bicycle trail along the railroad tracks … and we were in East Providence, which had a long history of having amusement parks and various venues along the railroad tracks,” Weygand said. “So we were interested in trying to reinvigorate the idea of having activities along the waterfront, which had been abandoned for a very, very long time.”

The East Bay Bike Path had plenty of fierce opposition, but had the support of the Rhode Island Department of Transportation and its then-director Edward Wood.

The wheels were now set in motion, and in 1982, Gov. J. Joseph Garrahy and the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (DOT), which was then led by Edward Wood, who died this year, threw their support behind the project and hired an engineering firm to research feasibility and design.

“The biggest thing that really helped us along the way was governor Joe Garrahy … he really embraced it,” Weygand said. “And also, there was a fella that was the head of the Department of Transportation, Ed Wood.”

But though Wood and Garrahy supported the project, many in their own circles were firmly against it.

“Even Wood at DOT ran into opposition by his own staff,” Weygand said. “They wanted to preserve the East Bay railroad track system … potentially for freight traffic and rail traffic … so his own staff was fighting him because they thought, if we give up the railroad tracks, we'll never get them back.”

Meanwhile, Byrnes, Weygand, a man named George Redman — you’ll find his name and portrait on the section of the bike path that crosses Interstate 195’s Washington Bridge — and a group of others were busy fighting their own battle on the ground to win the people of the five municipalities over on the idea.

“We constantly met, talked about different opportunities, did public hearings and meetings … and we’d get together periodically to share war stories about what was going on,” said Weygand, with a chuckle. “There was some real opposition. We had a public hearing in 1983 at the Barrington YMCA, and people were yelling and screaming and swearing at us, saying that all the criminals from Providence would use this bike path to come down and steal things from their homes. It was terrible.”

One vivid memory Weygand has of the resistance was when he helped organize a walk of the proposed area to give people a feel for what it could be like.

“One of the things that happened that day that we had this walk was, we had about 50 or so people go along the path … and in notifying all of the abutting owners, one of the owners was Squantum Club,” Weygand recalled. “We had invited them to join us along the way, and when we got to the Squantum Club, the manager was there with German shepherds and cars to prevent us from passing anywhere near their property.”

James W. Nugent, who was a member of the Squantum Association at the time, even went as far as to write a letter to James A. Baker III, a friend of his who was the chief of staff of President Reagan.

“At a time when the nation is looking for ways to cut expenditures and increase income, I thought it appropriate to call to your attention an expenditure that to me, and to many residents of Rhode Island, seems almost frivolous,” Nugent’s letter reads. “When there is publicity about people going hungry and dangerous federal deficits, the logic of expanding over $1 million on a bicycle path escapes me — especially when so many people along the route of the path object strongly to it. They fear increased vandalism and housebreaks from the transient traffic when their properties become more easily accessible.”

Nugent goes on to ask Baker to sway the federal government to withhold funds for the project.

Though opposition was strong, there were supporters who should not be discounted. One of them was Barry Schiller, who was the on the transportation committee of the environmental group Ecology Action.

In a 1984 letter to Wood, Schiller wrote, “This should be an ideal bikeway, scenic, safe and relatively flat that will become the pride of the East Bay.”

Schiller’s words were prophetic in some ways. Instead of being a so-called crime highway, the East Bay Bike Path has become a place where friends and families gather and exercise. Instead of negatively affecting home values, living near the bike path is considered an asset. It’s also inspired other Rhode Island municipalities to build their own bike paths; there are eight today, according to DOT.

In the end, the proponents won out, and on May 22, 1986 ground was broken at Riverside Square, and the East Bay Bike Path became a reality.

“It seems like a long time ago, but it really wasn’t,” Weygand said. “It was absolutely wonderful, breaking ground and seeing it constructed.”

Construction took place from 1987-92, and today when Rhode Islanders cruise by on its blacktop, many are likely unaware of all it took for it to get done. But those who were there, those who helped push it through, they remember.

“Every time I ride the East Bay Bike Path, it gives me the inspiration to keep going, because I knew it took persistence in the face of strong opposition to get it done,” Schiller said. “It’s a lesson for all of us to not give up.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News reporter.

Roger Warburton: Ocean damage increases in CO2 buildup as climate warms

January sea surface temperatures off southern New England have risen significantly since 1980.

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Living in Rhode Island, we are aware how the ocean rules our weather. What is less well known is that climate change is fundamentally altering the waters off our coast.

The image above shows how the January temperature of the ocean off New England has changed since 1980. For example, vast areas of dark blue — representing temperatures around 41-43 degrees Fahrenheit — have shrunk and are now a lighter blue, representing temperatures around 43-45 degrees.

The effects of a temperature rise in the ocean are significantly different from a temperature rise over land. We experience this difference when we walk across a sandy beach on a hot day. Exposed to the same sunlight, the sand burns our feet while the ocean warms gradually to the perfect temperature for a summer swim.

Rhode Island’s climate is moderated because the ocean takes longer than the land to heat up over the summer and longer to cool down during the fall.

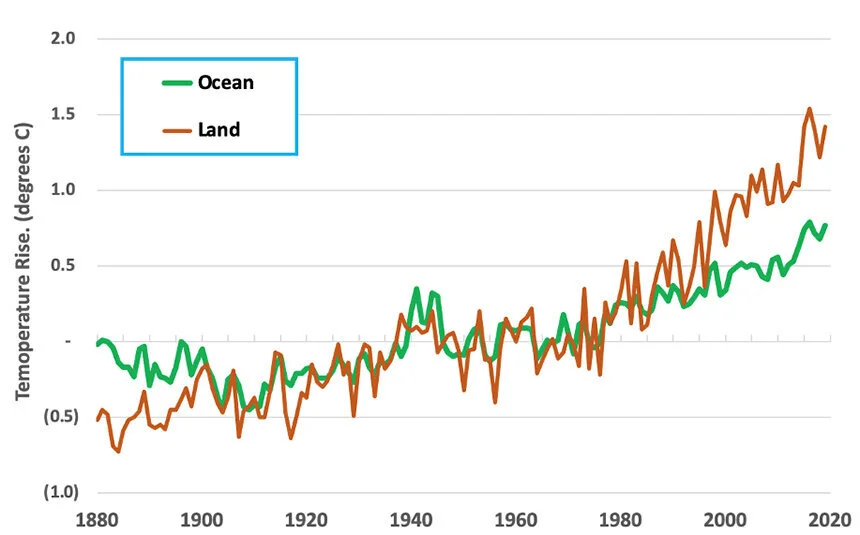

The global impact of this effect is shown in the image below, which shows that, over recent decades, the continents have warmed much more rapidly than the oceans. The Earth’s land areas were 1.4 degrees Celsius (2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 20th-Century average, while the oceans were 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer.

Since 1880, the Earth’s land temperature has risen faster than the ocean temperature. “

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

Unfortunately, the ocean’s smaller temperature rise isn’t good news, because the oceans can store more than four times as much heat as the land.

Even though ocean temperatures have risen less than the land’s, it’s becoming clear that the impacts of climate change depend on a complex interaction between dry land and the warming ocean.

Ships and buoys have been recording sea surface temperatures for more than a century. International cooperation and sharing of data between nations has created a global database of sea surface temperatures going back to the middle of the 19th century.

In addition, modern satellites remotely measure many ocean characteristics over the entire extent of the Earth’s oceans. The data are now so accurate that it’s possible to detect the small temperature rise from ships’ propellers as they traverse the oceans.

The warming of both the land and the oceans is caused by rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. When CO2 dissolves in the ocean, it forms carbonic acid, which in turn, breaks into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. Clams, mussels, crabs, corals and other sea life rely on those carbonate ions to grow their shells.

In 2015, Mark Gibson, deputy chief of marine fisheries at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, noted that ocean acidification is a “significant threat” to local fisheries.

In fact, a study published in 2015 found that the Ocean State’s shellfish populations are among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of acidification.

In polar regions such as Alaska, the ocean water is relatively cold and can take up more CO2 than warmer tropical waters. As a result, polar waters are generally acidifying faster than those in other latitudes.

The water in warmer regions can’t hold as much CO2 and are releasing it into the atmosphere. Therefore, the acidification from carbon dioxide is damaging the oceans in both polar and equatorial regions.

Warming oceans are also changing the winds that whip up the ocean, resulting in upwells from deep waters that are nutrient-rich but also more acidic.

Normally, this infusion of nutrient-rich, cool, and acidic waters into the upper layers is beneficial to coastal ecosystems. But in regions with acidifying waters, the infusion of cooler deep waters amplifies the existing acidification.

In the tropics, rising temperatures are slowing down winds and reducing the exchange of carbon between deep waters and surface waters. As a result, tropical waters are becoming increasingly stratified and more saturated with carbon dioxide. Lower layers then have less oxygen, a process known as deoxygenation.

Warming ocean temperatures have also caused a rapid increase of toxic algal blooms. Toxic algae produce domoic acid, a dangerous neurotoxin, that builds up in the bodies of shellfish and poses a risk to human health.

In coastal areas, such as Rhode Island, temperature changes can favor one organism over another, causing populations of one species of bacteria, algae, or fish to thrive and others to decline.

The sum of all these impacts is damaging to the Rhode Island economy. The state’s shellfish populations are already among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of a warmer ocean.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is an ecoRI News contributor and a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Figure 1 was generated using data from the Copernicus Climate Change and Atmosphere Monitoring Services (2020). The ERA5 dataset is produced by the European Space Agency SST Climate Change Initiative based on global daily sea surface temperature data from the Group for High Resolution Sea Surface Temperature and made available by the Copernicus Climate Data Store.

Figure 2 was generated using data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series.

R.I.'s long and problematic name

Rhode Island founder Roger Williams with members of the Narragansett tribe circa 1636.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I always thought that Rhode Island’s official name was charming – “State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,’’ with “Plantations” simply referring to the colonial settlements on land that the English were enthusiastically stealing from those Native Americans who had survived diseases brought by Europeans to the New England coast starting at least as early as the beginning of the 17th Century.

But these are very sensitive times and “Plantations” is evoked to mean agricultural land (especially for cotton, tobacco and sugar) worked by slaves. Of course we should never forget that much of the American slave trade was run out of Rhode Island.

Okay. The people have spoken. Still, I’ll still miss the old line about “the smallest state and the longest name.’’ And I wonder how much it will cost to change all the state’s stationery, etc.

Salt water is contaminating wells in Rhode Island as sea level rises

From ecoRI News

Drinking water wells at homes along the Rhode Island coastline are being contaminated by an intrusion of salt water, and as sea levels rise and storm surge increases as a result of the changing climate, many more wells are likely to be at risk.

To address this situation, a team of University of Rhode Island researchers is conducting a series of geophysical tests to determine the extent of the problem.

“Salt water cannot be used for crop irrigation, it can’t be consumed by people, so this is a serious problem for people in communities that depend on freshwater groundwater,” said Soni Pradhanang, associate professor in the URI Department of Geosciences and the leader of the project. “We know there are many wells in close proximity to the coast that have saline water, and many others are vulnerable. Our goal is to document how far inland the salt water may travel and how long it stays saline.”

Salt water can find its way into well water in several ways, according to Pradhanang. It can flow into the well from above after running along the surface of the land, for instance, or it could be pushed into the aquifer from below. Sometimes it recedes on its own at the conclusion of a storm, while other times it remains a permanent problem.

Pradhanang and graduate student Jeeban Panthi are focusing their efforts along the edge of the salt ponds in Charlestown and South Kingstown, where the problem appears to be the most severe.

Since salt water is denser than fresh water, it typically settles below. So the scientists are using ground-penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tests — equipment loaned from the U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Department of Agriculture — to map the depth of the saltwater/freshwater interface.

“In coastal areas, there is always salt water beneath the fresh water in the aquifer, but the question is, how deep is the freshwater lens sitting on top of the salt water,” said Panthi, who also collaborates with URI professor Thomas Boving. “We want to know the dynamics of that interface.”

The URI researchers plan to drill two deep wells this month to study the geology of the area and the chemistry of the groundwater to verify the data collected in their geophysical tests.

The first tests were conducted in the summer of 2019, and a second series was completed this fall after being delayed by the pandemic. Final tests will be conducted this spring when groundwater levels should be at their peak.

“The groundwater level was at its lowest point in 10 years this summer because of the drought,” said Panthi, a native of Nepal who studied mountain hydrology before coming to URI. “That will be a good comparison against what we expect will be high levels in April and May.”

Panthi has collected well-water samples from nearly two dozen residences for analysis. One of the contaminated wells is a mile inland from Ninigret Pond, in Charlestown.

Ninigret Pond, in Charlestown, R.I.

“A homeowner had a deep well drilled for a new house and it ended up with extremely saline water,” Pradhanang said. “Deep wells close to the salt ponds or the coast are more likely to have saltwater intrusion than shallow wells, though shallow wells can also have problems if they become inundated with salt water.”

Another URI graduate student, Mamoon Ismail, is developing a model to simulate saltwater intrusion into drinking water wells based on the changing pattern of precipitation and the potential for extreme storms. They hope to be able to predict how far inland salt water will intrude following a Category 1 hurricane compared to a Category 2 storm, for instance.

This research is being funded by the Rhode Island office of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Olivia Ouellette: How safely can coyotes co-exist with humans?

A coyote pouncing on prey in the winter

-Photo by Yifei He

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

University of Rhode Island graduate student Kimberly Rivera has been conducting a survey since the beginning of October on the coyote population in Rhode Island.

Rivera, who graduated in 2016 with a bachelor’s degree in environmental science from the University of Delaware, hopes to promote better co-existence between coyotes and Rhode Islanders.

Since the beginning of her work, Rivera has received about 425 completed responses. With a minimum goal of 500 completed surveys, Rivera plans to keep the survey open until at least December.

The survey takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and asks respondents about demographics — age, location, are you a full-time Rhode Island resident — and goes on to ask about any experiences with coyotes.

“Ultimately, what I really want to do is understand how people’s knowledge, belief and feelings tie back to these independent variables that were measured,” Rivera said.

Along with the survey, Rivera is also conducting more hands-on research using camera-trap technology. Initially intended for a bobcat study, these cameras are placed around Rhode Island, and when something walks by, it triggers the motion-sensor camera to take a series of photographs. These cameras then store the photographs, as well as save the date and time, letting Rivera look back and see when and where coyotes are most active.

Through her work, Rivera is trying to promote the acceptance and a better understanding of coyotes.

“I think co-existence is key moving into the future,” she said. “I want people to think about how they co-exist with coyotes and what that means to them.”

Rivera’s original plan was to travel to Madagascar to study seven native carnivore species there and see how the locals interact with those species. She was interested in seeing how people’s attitudes and knowledge about those species affected their interactions with them. The coronavirus pandemic required her to change her research plans.

Although her initial plans fell through, Rivera was still enthusiastic about reconstructing her project into a human-wildlife conflict study on coyotes, similar to what she would have researched in Madagascar.

“I’ve always had an interest in coyotes because on the East Coast they’re one of the only apex predators,” she said.

At the end of the survey there are a series of questions about how negatively people view coyotes in regards to certain issues, such as pets, livestock and property damage.

“I think it really depends on who you ask,” Rivera said. “I think there is potential for coyotes to be dangerous.”

One of the top concerns people have in Rhode Island in connection with coyotes is the safety of their pets.

“If you have small dogs that you are leaving out in the yard without fences or you have outdoor cats that are wandering around, there's always going to be a risk,” Rivera said. “And that could be coyotes or it could be a car hitting them, so it's just one of many risks.”

Olivia Ouellette is a University of Rhode Island journalism student.

How fares 'Open Education' in Rhode Island?

— Photo by Johannes Jansson

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In the following Q&A, Fellow for Open Education Lindsey Gumb takes the pulse of Open Education in Rhode Island with two key leaders in the field: Dragan Gill, who is a Rhode Island College reference librarian and co-chair of the Rhode Island Open Textbook Initiative, and Daniela Fairchild, who is director of the Rhode Island Office of Innovation.

In September 2016, Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo announced her Open Textbook Initiative, challenging the state’s postsecondary institutions to save Rhode Island students $5 million over five years in textbook costs using “open” textbooks instead of expensive, commercial textbooks. The Rhode Island Office of Innovation (InnovateRI) has helped lead the initiative through its partnership with the Adams Library at Rhode Island College (RIC) and steering committee that includes a librarian from each of the state’s postsecondary institutions. Now a little over four years into the initiative we ask Dragan Gill and Daniela Fairchild to share their thoughts on the status of the challenge, lessons learned and their hopes for the future use of open educational resources (OER) in Rhode Island.

Gumb: Interestingly, Rhode Island’s Open Textbook Initiative isn’t mandated by any specific legislation. In what ways has this made the challenge easier … or more difficult?

Gill: Without legislation, we have been able to develop individualized methods of reaching a shared goal within the scope of the governor’s challenge. Each institution has been able to find a meaningful way to incorporate open textbooks and OER in their curricula, while developing strategies that fit within the scope of the institution’s mission and goals, resources and support they have for this work. On the other hand, having funding tied to well-crafted legislation would better support the staffing, professional development and faculty time needed to further the initiative. Having had time to understand the needs of Rhode Island institutions and to review legislation from other states, I believe we now could work with the governor to draft legislation that supports and guides OER efforts in a pragmatic way for our state.

Fairchild: Legislation can be a blessing and a curse. While it adds gravity and force to an initiative, it also can lead to prescription and a compliance-focus. Sometimes, those doing the work end up spending more time preparing for the next mandated legislative report and less time thinking strategically and creatively about the best way to solve for the need or problem identified through legislation. As one of my policy-wonk colleagues once said, legislation is a sledgehammer. There are times when that is necessary; there are times when one would be better served by a scalpel. For this initiative specifically, not having associated legislation has allowed for campus-specific efforts and has allowed a true fostering of a “coalition of the willing.” It has let us experiment and think creatively for each institution’s context. That said, it has meant that the work has truly stayed a coalition of the willing—those who have understood the need have continued to engage. Those who might need a sledgehammer-like prod have not. To Dragan’s point above, now that we are four years into the work, and have a more intricate understanding of the needed guidance, resources and supports for our collective institutions—as well as a sense of lofty, yet realistic goals—it might be time to revisit the conversation.

Gumb: This challenge tracks student savings data from using open textbooks in place of commercial textbooks, but we know that OER does so much more than save students money. How is the Rhode Island Open Textbook Initiative Steering Committee addressing these other areas like equity and pedagogy?

Gill: Unfortunately, we aren’t doing as much as we’d like. Because the challenge was issued as part of the governor’s broader educational attainment goals, equity has been a key component of outreach, but we haven’t found a way to measure this across the state yet. On my campus, Rhode Island College, I have been working on collecting faculty OER and open textbook adoption data in our student information system for several reasons, including better analyzing the impact OER and open textbooks are having on student retention and completion. We are also currently working on creating a way to collect qualitative data about OER-enabled pedagogy practices across the state. We want this data collection to be both easy for faculty to use, but also provide meaningful information for the steering committee. We also want to showcase it. Lastly, this will provide a more complete picture of faculty engagement with openly licensed materials than our data collection thus far, which, focusing on adoption, hasn’t included more creative work or pedagogical practices.

Fairchild: We’ve seen this manifest in different ways at different institutions. Some of our steering committee members, knowing that textbook cost doesn’t resonate with their faculty as loudly as other rationale for open, have focused their “why” communication around open pedagogy, equity and even academic freedom. And, while Dragan is right that there is more to do on this front—and that data tracking around these pieces becomes a bit trickier—what we have seen is the Open Textbook Initiative serve as a launchpad for steering committee members to have those conversations. “Everyone! Listen up! The state has this challenge to save students money. Now that I have your attention, let me show you all the other reasons why open matters—and all the ways open can complement and support your own academic and pedagogical goals.”

Gumb: What has been the Steering Committee’s biggest challenge to date, and how are you working through it?

Gill: As a committee of librarians, we all have to balance our work on the initiative with the responsibilities we were hired for. To respect that this is different for each library, we have set very few hard deadlines and work with each campus to create their own goals towards supporting Open Education for the semester. But to leverage the strengths of the group, we use retreats to foster collaboration among committee members working on similar tasks or with members who have had successes in a problem area for others. Additionally, we have had some turnover in committee membership, which has brought in fresh ideas, but has made sustaining work and processes harder. In addition to having a call or meeting with each new member, we share outreach and training materials in a collection for all committee members to adapt and use.

Fairchild: I agree with Dragan … the natural cadence of steering committee turnover and the lack of dedicated time to support the work has been challenging, but we’ve been working through these things. And continuing to think through ways we can automate processes so they can endure even through steering-committee-member shifts. Longevity and sustainability are relevant issues too. Across campuses, we have leveraged the challenge to elevate open textbooks, but also open more broadly—and we’ve seen a lot of interest and excitement from faculty who are “early adopters” of open textbooks. As we continue, we will need to start connecting to the “early adopter” and “late adopter” faculty; this will require different communications tactics and different supports. We have begun this strategizing through the twice-annual steering committee retreats. And we plan to use the culmination of our current challenge phase to launch phase 2 and reinvigorate that engagement.

Gumb: Public and private institutions often embrace OER in different ways. How has your Steering Committee, which is composed of both, navigated these differences together?

Gill: By focusing on the value of open education, we are able to build our individual efforts based on a shared core understanding. For some campuses, equity and access are more important; for others, there’s more room to discuss creative pedagogy. But ultimately, all of us are working toward offering the best education to our students and, by working with a range of campus partners, we’re able to address both visions at each institution. One thing I’ve found interesting is how the conversation on each campus shifts. When the challenge began, equity and access resonated on my campus. But in sustaining our work, we’ve added exploring OER-enabled pedagogy. Conversely, I know my colleagues at Roger Williams University began their work heavily focused on faculty creation of OER, but in response to results from a student survey have been including more information about the impact of textbook costs on their students in their outreach efforts.

Unfortunately, there have also been inequities. Rhode Island’s Office of Postsecondary Council has funded the state’s three public institutions’ membership in the Open Education Network (OEN), an active community of higher education leaders who work together to build sustainable open education programs. But as the governing body for the public institutions, it cannot do the same for our private partners. Two private institutions have also advocated for funding and joined the OEN, but if we were to start over, having the funding for each institution to join the OEN or SPARC (the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition) would be high in my priorities.

Gumb: What makes you most proud when you look back on the past four years of this challenge?

Gill: In addition to being on track to meet our goal, I am most proud of our ability to quickly find and work with partners. National organizations like OEN, SPARC and Student PIRGs have all been collaborators since the start, but locally, we have also worked with: the Governor’s Commission on Disabilities for a training session and guidance on accessibility; Providence Public Library’s Tableau User Group, through the Data for Good Initiative, to visualize our data; the Rhode Island Teaching and Learning Consortium (RITL) to share our work and see how they can better help engage faculty; and the Office of Library and Information Services to co-sponsor a two-day “Copyright Bootcamp” for the steering committee and librarians across the state. In return, we provided an overview of OER and Open Access for public libraries through OLIS’s professional development workshop series, provided the first large dataset to the Tableau User Group, opened the Copyright Bootcamp to all librarians in the state, and with the background knowledge to do so, are advocates for more accessible teaching and learning materials on our campuses. This showcases the best of librarianship’s ability to bring experts and networks together to benefit all.

Fairchild: Hear, Hear! Now, my much more bureaucratic answer. I’m proud of co-creating something that has legs. In government (as with all systems and large institutions), change is hard. Status quo processes (whether explicit or not) are difficult to change. Initiatives launched by one administration are rarely kept alive through subsequent administrations—either because they are overtly reversed, or because they just fade after losing their executive branch champion. The Open Textbook Initiative has been messy and imperfect, but it has diffuse champions, including those who officially represent our work through the steering committee most notably, but also the faculty our committee members have worked with and the many partners. I think a lot about how to ensure the “stickiness” of innovation in public systems. And I am proud of how so many partners and people have come together to give this work one of the best shots at organic stickiness that I’ve seen.

Gumb: What’s one piece of advice you’d like to share with legislators in the Northeast who might be considering issuing an open textbook challenge such as Rhode Island’s?

Gill: Plan ahead! Scan each institution for existing campus leaders and develop your steering committee or leadership before you announce the challenge. Define your goals and what measures you’ll use to assess progress before you start, but leave room for new ideas.

Fairchild: Just one? If you will permit me, here are three (they are short!) 1) Allow for creativity: Don’t regulate or regiment Open work so much that it stifles new thinking or doesn’t allow for those who you have tasked with the work to actually do the work—especially as the landscape and knowledge base around this is continuously maturing; 2) Foster collaboration: This shouldn’t just be a public institution thing, or something run through one school (even your flagship!), so be mindful of how you’re writing legislation to allow all institutions to see themselves as productive partners and supporters of your goals; 3) You don’t need money, necessarily (we did this without very much at all), but consider how and when targeted, smart investment can help. Dragan mentioned consortia memberships above: Those carry a small-dollar price tag and go a long way with securing buy-in at the outset (it shows that you are investing in the people who are going to make this happen for you) and that you care about the sustainability of this work. We additionally supported faculty with micro-grants to review and adopt open textbooks—which was important at the outset to show that leadership cared about this, but also is important later in any challenge for incentivizing the early or late adopters.

Todd McLeish: More sites found with threatened turtles

A Diamondback Terrapin

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A pilot project using volunteers to scout for new populations of Rhode Island’s rarest turtle, the Diamondback Terrapin, turned up 15 new sites where the turtles have been confirmed. But despite the new populations, the biologist who led the project said the state’s terrapins are no less threatened than they were before the new populations were discovered.

Diamondback Terrapins are the only turtle in the region that live in salt marshes and brackish waters.

Herpetologist Scott Buchanan, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, said that before 1990, when a population of these turtles was discovered in Barrington, “no one had seen a terrapin in Rhode Island in many years.” Additional populations were discovered elsewhere in the state in the past decade, and when Buchanan was hired in 2018 and began asking around, he heard a number of unconfirmed reports of the turtles being observed elsewhere in Rhode Island.

“That led me to think that they’re probably more widespread in the state than the narrative would lead us to believe,” he said.

So he examined maps to identify “reasonable places” where he could send volunteers on a regular basis to see if they could spot the terrapins.

Four volunteers each visited two to four sites twice a week from late May through mid-July, and an additional volunteer surveyed a dozen sites. During each visit they scanned the water with binoculars for three 5-minute periods and counted any turtle heads they observed.

The discovery of 15 new sites was a revelation to Buchanan.

“What it means is that they are much more widespread than we had thought,” he said. “It’s encouraging from a conservation standpoint, but at many of these sites, we have little or no information about how many turtles may be there, whether they are successfully breeding, or whether they are established populations. We don’t want to be overconfident or get too comfortable with the fact that there are multiple sites containing the species.”

Most of the newly discovered terrapin sites are in coves along mid and upper Narragansett Bay. They’re still mostly absent from the lower bay, according to Buchanan.

“What we’re seeing now is probably a shadow of their former distribution and abundance,” he said. “They’re out there, that’s excellent, but we know there’s lots of places they don’t occur. All the evidence suggests that they’re still absent from many places where they were historically present. And the types of abundances that we’re documenting are probably far less than historic abundances.”

Buchanan speculated that the newly discovered populations in the upper bay may be the result of dispersal from the Barrington population, which has grown to number in the hundreds because of extensive conservation efforts.

Despite the success of the survey project, Buchanan is still concerned for the state’s Diamondback Terrapins. Most terrapin eggs are consumed by what he calls “human-subsidized predators,” including coyotes, raccoons, skunks and dogs. Terrapins are also at risk of being illegally collected for the pet trade, which is why he prefers not to reveal the location of the newly discovered sites. They also face drowning in crab traps, injury from being struck by boats, and automobile strikes as females cross roads on their way to their nesting territories.

“The big threat, though, is sea-level rise and salt marsh decline,” he said. “They’re an obligate salt marsh species; if sea level rises and marshes disappear, they don’t have a chance. That’s something I’m especially worried about over the next 10, 20, 30 years along the Rhode Island coast. Salt marshes are critical as a source of food and a place where they overwinter and take shelter, especially the juveniles and hatchlings.

“This new information we have is very encouraging, but it doesn’t mean we should let our guard down. They’re still a species that warrants conservation, even without sea-level rise. We must remain vigilant.”

Having identified the location of additional terrapin populations, Buchanan hopes to prioritize those sites for future conservation efforts, modeled after the successful nest-protection and monitoring efforts in Barrington.

“Knowing where they are, there are lots of small steps you can do to improve their conservation,” he said. “Things like small-scale habitat management, create barriers to keep them off busy roads, public outreach to ensure boaters use caution, adapt local pot fishery management.”

The success of the pilot project to identify new Diamondback Terrapin populations has inspired Buchanan to double or triple the effort next summer at numerous additional locations. He also hopes to continue the project for many years to eventually be able to identify population trends at each site. He will be seeking additional volunteers this spring to survey coastal sites around the state in June and July. Those interested in volunteering should contact Buchanan at scott.buchanan@dem.ri.gov.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Roger Warburton: What lobsters tell us about climate change

If present trends continue, by the end of the century, the cost of global warming could be as high as $1 billion annually for Providence County, R.I., alone, according to data from a 2017 research paper. That’s about $1,600 per person per year. Every year.

But, before we talk about the future, let’s discuss the economic damage that has already occurred in Rhode Island because of warming temperatures.

Like rich Bostonians, Rhode Island’s lobsters have moved to Maine. In 2018, Maine landed 121 million pounds of lobsters, valued at more than $491 million, and up 11 million pounds from 2017. It wasn’t always so.

Andrew Pershing, an oceanographer with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, has noted that lobsters have migrated north as climate change warms the ocean. In Rhode Island, for instance, days when the water temperature of Narragansett Bay is 80 degrees or higher are becoming more common. From 1960 to 2015, the bay’s mean surface water temperatures rose by about 3 degrees Fahrenheit, according to research data.

A 2018 research paper Pershing co-authored said ocean temperatures have risen to levels that are favorable for lobsters off northern New England and Canada but inhospitable for them in southern New England. The research found that warming waters, ecosystem changes, and differences in conservation efforts led to the simultaneous collapse of the lobster fishery in southern New England and record-breaking landings in the Gulf of Maine.

He told Science News last year that with rocky bottoms, kelp and other things that lobsters love, climate change has turned the Gulf of Maine into a “paradise for lobsters.”

However, in the formerly strong lobster fishing grounds of Rhode Island, the situation is grim. South of Cape Cod, the lobster catch fell from a peak of about 22 million pounds in 1997 to about 3.3 million pounds in 2013, according to the 2018 paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Lobsters provide interesting lessons on the impact of the climate crisis.

A conservation program called V-notching helped protect Maine’s lobster population. “Starting a similar conservation program earlier in southern New England would have helped insulate them from the hot water they’ve experienced over the last couple of decades,” Malin Pinsky, a marine scientist with Rutgers University, told Boston.com two years ago.

Rhode Island’s lack of conservation efforts in the face of the growing climate crisis contributed to the collapse of its lobster fishery. Doing nothing or too little in the face of a changing climate can be economically devastating.

Another existing, and growing, threat to the economic health of Rhode Island comes from Lyme disease, which has increased by more than 300 percent across the Northeast since 2001. A changing climate is a big reason why. There is a growing body of evidence showing that climate change may affect the incidence and prevalence of certain vector-borne diseases such as Lyme disease, malaria, dengue, and West Nile fever, according to a 2018 study.

Chronic Lyme disease is more widespread and more serious than generally realized. There are some 20,000 cases annually in the Northeast and each averages about $4,400 in medical costs. Most Lyme disease patients who are diagnosed and treated early can fully recover. But, an estimated 10 percent to 20 percent suffer from chronically persistent and disabling symptoms. The number of such chronic cases may approach 30,000 to 60,000 annually, according to a 2018 white paper.

As the lobsters and the ticks vividly demonstrate, prevention is cheaper than cure. The longer we wait, the more painful, and expensive, the consequences will be.

The aforementioned 2017 study Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States by world-renown economists and climate scientists projects the impact of climate change for every county in the United States. The results for Rhode Island and its neighbors are summarized in the map to the right, which depicts the estimated economic damage, in millions of dollars annually for each county in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

The data make clear that the economic damage will not be uniformly distributed. Some counties, such as Providence County, will be hit much harder than others. It also may seem that the southern counties will suffer much less. But that isn’t quite true, as graph below shows. The damage per person per year is projected to be substantial.

The total economic damage to Rhode Island, by 2080, could result in a 2 percent decline in gross domestic product (GDP). To put that in context, during the Great Recession of 2008-2010, there was only one year of GDP decline: minus 2.5 percent in 2009. By 2010, GDP had bounced back to positive growth, at 2.6 percent.

Therefore, the impact of a 2 percent hit to Rhode Island’s GDP from the climate crisis could look like the recession of 2009, only becoming permanent, continuing year after year. Also, it won’t all happen in 2080, the damage will continually get worse.

The economic damage is projected to come from more frequent and intense storms; sea-level rise; increased rainfall resulting in more flooding; higher temperatures, especially in the summer; drought that leads to lower crop yields; increased crime.

In addition, essential infrastructure will be impacted, including water supplies and water treatment facilities. Ecosystems, such as forests, rivers, lakes and wetlands, will also suffer, and that will impact human quality of life.

In the coming two weeks, we will describe how each Rhode Island county faces different levels of the above threats. As a result, each county needs to develop appropriate mitigation strategies.

The damages from the climate crisis will place major strains on public-sector budgets. However, much of the economic damage will be felt by individuals and families through poorer health, rising energy costs, increased health-care premiums, and decreased job security.

As always, prevention is cheaper, and more effective, than cure. Inaction on climate change will be the most expensive policy option.

The lobsters should teach us a valuable lesson: conservation measures based on sound scientific and economic principles could have helped mitigate losses caused by the climate crisis.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport ,R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Llewellyn King: 'Job retraining' can be an empty slogan without aptitude

Computer skills training

WEST WARWICK ,R.I.

When a vaccine for COVID-19 is as easily available as a flu shot, and when the public is comfortable getting it, it will be a time of victory -- Victory Virus. And it will be a time to begin building the new America.

Things will have changed. We won’t be going back to the future. Most visible will be the disappearance of a huge number of low-end jobs. No one knows how many but, sadly, we have a good idea where it will hurt most: among semi-skilled and unskilled workers.

They are those who don’t have college degrees and those who wouldn’t have qualified to enter college. Higher education isn’t for everyone, even if money wasn’t an issue. College is for those who can handle it, therefore benefiting.

It isn’t only the virus that is changing the employment picture but also the continuing technology revolution. Data is going to be king, according to Andres Carvallo, founder of CMG, the Austin-based technology consulting company, and a professor at Texas State University. Data, he argues, linked with the spreading fifth-generation telephone networks (5G) will delineate the future. Carvallo has pointed out that data from all sources have value, “even the homeless.”

Carvallo’s colleague on a weekly video broadcast about the digital future, entrepreneur John Butler, a University of Texas at Austin professor, believes that data and 5G will start to affect American business in a big way and new business plans will emerge, taking into account the increasing deployment of sensors and the ability of 5G to move huge quantities of data at the speed of light.

Carvallo explains, “If you’re moving data at the rate of 40 megabytes per second now, with 5G you’ll be able to move it at 1,000 megabytes per second.”

The technology revolution will continue apace, but will there be a place for those who aren’t embraced by it, like those who serve, clean, pack, unpack, and have been doing society’s housekeeping at the minimum wage or just above it?

Evidence is that they are already in sorry shape with a much higher rate of COVID-19 infections than the general population, and even in the best of times they have poorer health — an indictment of our health system.

The future of the neediest workers is imperiled, in the short term, because the jobs they have had and the jobs that have always been there for those on the lower ladders of employment are disappearing. A goodly chunk of these workers will be out of work for a long time.

Retraining is the solution that is advocated by those who aren’t caught in this low-level work vise. Retraining for most people is, to my mind, just a crock. It is a bromide handed down by the middle class to those below; a callow concept that doesn’t fit the bill. It soothes the well-heeled conscience.

First, some people can’t grasp new concepts, particularly as they age. Are you really going to teach a middle-aged, short-order cook to navigate computer repair? That is not only impractical, it is cruel.

A further disadvantage is that the affected workers not only are going to be shut out of their traditional lines of employment, but they also carry an additional burden, another barrier to retraining: They almost exclusively are the products of shoddy public education, so there is very little to build on if you’re going to retrain. If you have marginal English most information technology work is going to be inaccessible; rudimentary math is another stumbling block.

Very smart people are candidates for retraining. The graduate schools see plenty of students who get multiple, disassociated degrees, like lawyers who have nuclear engineering degrees. I know a prominent head of surgery at a Boston hospital who has a degree in chemical engineering.

They are the polymaths, but they aren’t laboring for the minimum wage.

The loss of jobs due to COVID-19 comes at a time when technology, for the first time since the Newcomen engine kickstarted the Industrial Revolution in 1712, might be a job subtractor, not the multiplier it has been down through the ages.

Unemployment insurance is a stopgap but it also obscures the full extent of the skill void, the aptitude hurdle.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Website: whchronicle.com

Lemonade from lemons

— Photo by AleSpa

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

This might be the most significant news around here lately. Cambridge-based Synapse Energy Economics has done a study, commissioned by the State of Rhode Island, that concludes that new solar arrays on already-developed land such as parking lots and brownfields could power many, many Rhode Island homes. With malls and some free-standing big-box stores closing, there will be more and more such available space on abandoned parking lots. And of course there are plenty of flat roofs available. It beats chopping down more trees or building over old farm fields to make space for more rural solar farms.

To see/hear a video on this big business and environmental opportunity, please hit this link.

Grace Kelly: Waste management important in suppressing coyote population

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

On a recent Friday afternoon, online viewers watched as Numi Mitchell, lead scientist for the Narragansett Bay Coyote Study (NBCS), held what looked like a large antenna in one hand and a beeping device in her other. An osprey cries overhead, and if it weren’t for the Providence Police Department’s Clydesdale horses in the paddock, you wouldn’t know that Mitchell was in Roger Williams Park.

“She’s here!” Mitchell said, as a particularly loud beep sounded.