'Purifying fires'

Civil War memorial on the common of Amherst, N.H. The town was named for mass murderer Lord Jeffrey Amherst. (See below.)

“The Republic needed to be passed through chastening, purifying fires of adversity and suffering; so these came and did their work and the verdure of a new national life springs greenly, luxuriantly, from their ashes.’’

— Horace Greeley, New York City editor, publisher and essayist, in Greeley on Lincoln. A native of Amherst, N.H., he was and is widely quoted. He is famously reputed to have said: “Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.’’

Greeley birthplace

Settled about 1733, Amherst was first called "Narragansett Number 3", and then later "Souhegan Number 3". In 1741, settlers formed the Congregational church and hired the first minister. Chartered on Jan. 18 1760, the town was named for General Lord Jeffrey Amherst, who commanded British forces in North America during the French and Indian War. Lord Amherst is also known for promoting the practice of giving smallpox-infected blankets to Native Americans in an effort "to Extirpate this Execrable Race" (as quoted from his letter to Col. Henry Bouquet on July 16, 1763). His actions may have killed at least 100 people.

Roger Warburton: Nov. was the warmest Nov. yet recorded

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Stop me if you’ve heard this story before: Last month was the warmest ever.

The latest global temperature data show that November 2020 was the warmest November ever recorded. The above figure shows the overall trend in global temperatures since 1880.

The red line for 2020 shows that average temperature for November was significantly above that of previous years. The significant rise in November’s temperature makes it very likely that 2020 will be the warmest year on record.

The figure below shows the average global November temperatures since 1880. The rise in November temperatures is quite substantial. The figure also shows that recent November temperature rises have been even more dramatic.

November mean surface air temperatures over land and ocean every decade since 1880. Data source: NASA GISTEMP. (Roger Warburton/ecoRI News)

In fact, the rise in November temperatures since 2015 is in line with a particularly disturbing trend: The latest data show that, since 2015, the warming trend is accelerating. The figure below shows the seriousness of the problem.

Global air temperatures over land and ocean. The yearly mean, blue, and the 5-year mean, red, have risen significantly above the gray trend line. Data source: NASA GISTEMP. (Roger Warburton/ecoRI News)

The gray line represents the steadily rising global temperature that was reasonably steady between 1970 and 2015. Since then, the temperature rise has accelerated. This is shown in the figure by the blue and red curves rising significantly above the gray trend line.

The gray trend line has often been used to predict long-term impacts of the future temperature rise. If the acceleration continues, many of the current estimates of the impacts of global warming will be seen as severely underestimated.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: GISTEMP Team, 2020: GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), version 4. NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Dataset accessed 20YY-MM-DD at https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/. Lenssen, N., G. Schmidt, J. Hansen, M. Menne, A. Persin, R. Ruedy, and D. Zyss, 2019: Improvements in the GISTEMP uncertainty model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 124, no. 12, 6307-6326, doi:10.1029/2018JD029522.

Looking for a bed

“The Midnight Caller 3’’ (cloth and floss), by Cambridge-based Liz Doles, in her show “The Midnight Caller and Other Stories,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Jan. 31. Her pictures incorporate clothing labels, remnants and other scraps.

The real Puritans

Quaker Mary Dyer led to execution on Boston Common, on June 1, 1660, by an unknown 19th Century artist. The Puritans denounced Quakerism from the start.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Sarah Vowell’s chatty (and sometimes a tad vaudevillian and snarky) and well-researched book The Wordy Shipmates is a remarkable combination of drollery and serious, if popular, historical writing. She gets into the heads of the New England Puritans, some of whom were brilliant, such as John Winthrop, Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, and virtually all of whom were literate and wrote a lot, and analyzes how their actions and beliefs help lay the religious, civic and political foundation of what became the United States. Indeed, as the late Anglo-American journalist Alistair Cooke once observed, “New England invented America.’’

She says in the book that “the most important reason I am concentrating on {Massachusetts Bay Colony leader John} Winthrop and his shipmates in the 1630’s is that the country I live in is haunted by the Puritans’ vision of themselves as God’s chosen people, as a beacon of righteousness that all others are to admire.’’

But in Winthrop’s famous and sometimes misquoted and misunderstood line, the colony would be "as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us,’’ he was warning that its members would be judged for how they lived there. And he never called that city “shining.’’

Her book is a very entertaining place to start to learn about the creation of New England and the myths and facts around it. Then you can go and read the much more scholarly work of such academic historians of the region as Harvard’s brilliant Perry Miller (1905-1963).

My father’s ancestors were Massachusetts Bay Puritans, though some fairly early on became Quakers and then were advised to get out of town fast. My only physical things from 17th Century New England and Olde England are some musty religious tracts, which those characters cranked out in large numbers. Worth little but useful reminders of how far away, and near, those people were.

Interior of the Old Ship Church, built in 1681 as a Puritan meetinghouse in Hingham, Mass. Puritans were Calvinists, so their churches were unadorned and plain. It is the oldest building in continuous ecclesiastical use in the United States and today serves a congregation of Unitarian Universalists, whose theology Puritans would have condemned. But Unitarianism evolved from the Puritans via Congregationalism.

Landscapes we screw up

Solastalgia, by Boston-based Rhonda Smith, at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Jan. 20-Feb. 28. She looks at beloved geographies permanently altered by humans. Constructed of clay, papier mache and wire, the work invites the viewer to a more intimate relationship with our shared landscape.

Hit these links:

https://rhondasmithartist.com/home.html

kingstongallery.com

Winter mysteries

“….The exhausting mysteries

of the self grow gray on the far horizon, but

the frosted windows of the schoolhouse gleam.’’

From “Schoolboys with Dog, Winter,’’ by William Matthews (1942-1997), New England-educated poet and essayist.

Mr. Matthews spent a term as poet in residence at The {Robert} Frost Place, in Franconia, N.H.

— Photo by Schnobby

Corrupting power in Mass.

Edward Brooke

“Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely, and I found that out when I was Attorney General in Massachusetts.’’

— Edward Brooke (1919-2015), the Bay State’s attorney general in 1963-67. In 1966 he became the first African-American popularly elected to the U.S. Senate, where he served until 1979.

Wildlife, ecology and the next pandemic

Sign over I-93 in Boston warning of COVID-19 travel restrictions in Massachusetts

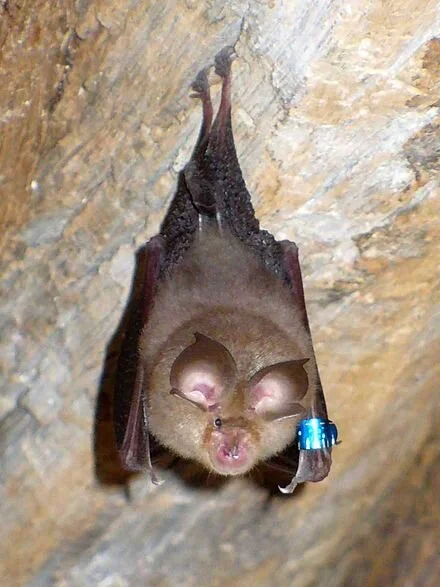

A horseshoe bat, seen as likely source of COVID-19

As the COVID-19 pandemic heads for a showdown with vaccines it’s expected to lose, many experts in the field of emerging infectious diseases are already focused on preventing the next one.

They fear another virus will leap from wildlife into humans, one that is far more lethal but spreads as easily as SARS-CoV-2, the strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19. A virus like that could change the trajectory of life on the planet, experts say.

“What keeps me up at night is that another coronavirus like MERS, which has a much, much higher mortality rate, becomes as transmissible as covid,” said Christian Walzer, executive director of health at the Wildlife Conservation Society. “The logistics and the psychological trauma of that would be unbearable.”

SARS-CoV-2 has an average mortality rate of less than 1%, while the mortality rate for Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS — which spread from camels into humans — is 35%. Other viruses that have leapt the species barrier to humans, such as bat-borne Nipah, have a mortality rate as high as 75%.

“There is a huge diversity of viruses in nature, and there is the possibility that one has the Goldilocks characteristics of pre-symptomatic transmission with a high fatality rate,” said Raina Plowright, a virus researcher at the Bozeman Disease Ecology Lab, in Montana. (COVID-19 is highly transmissible before the onset of symptoms but fortunately is far less lethal than several other known viruses.) “It would change civilization.”

That’s why in November the German Federal Foreign Office and the Wildlife Conservation Society held a virtual conference called One Planet, One Health, One Future, aimed at heading off the next pandemic by helping world leaders understand that killer viruses like SARS-CoV-2 — and many other less deadly pathogens — are unleashed on the world by the destruction of nature.

With the world’s attention gripped by the spread of the coronavirus, infectious disease experts are redoubling their efforts to show the robust connection between the health of nature, wildlife and humans. It is a concept known as One Health.

While the idea is widely accepted by health officials, many governments have not factored it into policies. So the conference was timed to coincide with the meeting of the world’s economic superpowers, the G20, to urge them to recognize the threat that wildlife-borne pandemics pose, not only to people but also to the global economy.

The Wildlife Conservation Society — America’s oldest conservation organization, founded in 1895 — has joined with 20 other leading conservation groups to ask government leaders “to prioritize protection of highly intact forests and other ecosystems, and work in particular to end commercial wildlife trade and markets for human consumption as well as all illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade,” they said in a recent press release.

Experts predict it would cost about $700 billion to institute these and other measures, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society. On the other hand, it’s estimated that covid-19 has cost $26 trillion in economic damage. Moreover, the solution offered by those campaigning for One Health goals would also mitigate the effects of climate change and the loss of biodiversity.

The growing invasion of natural environments as the global population soars makes another deadly pandemic a matter of when, not if, experts say — and it could be far worse than covid. The spillover of animal, or zoonotic, viruses into humans causes some 75% of emerging infectious diseases.

But multitudes of unknown viruses, some possibly highly pathogenic, dwell in wildlife around the world. Infectious disease experts estimate there are 1.67 million viruses in nature; only about 4,000 have been identified.

SARS-CoV-2 likely originated in horseshoe bats in China and then passed to humans, perhaps through an intermediary host, such as the pangolin — a scaly animal that is widely hunted and eaten.

While the source of SARS-CoV-2 is uncertain, the animal-to-human pathway for other viral epidemics, including Ebola, Nipah and MERS, is known. Viruses that have been circulating among and mutating in wildlife, especially bats, which are numerous around the world and highly mobile, jump into humans, where they find a receptive immune system and spark a deadly infectious disease outbreak.

“We’ve penetrated deeper into eco-zones we’ve not occupied before,” said Dennis Carroll, a veteran emerging infectious disease expert with the U.S. Agency for International Development. He is setting up the Global Virome Project to catalog viruses in wildlife in order to predict which ones might ignite the next pandemic. “The poster child for that is the extractive industry — oil and gas and minerals, and the expansion of agriculture, especially cattle. That’s the biggest predictor of where you’ll see spillover.”

When these things happened a century ago, he said, the person who contracted the disease likely died there. “Now an infected person can be on a plane to Paris or New York before they know they have it,” he said.

Meat consumption is also growing, and that has meant either more domestic livestock raised in cleared forest or “bush meat” — wild animals. Both can lead to spillover. The AIDS virus, it’s believed, came from wild chimpanzees in central Africa that were hunted for food.

One case study for how viruses emerge from nature to become an epidemic is the Nipah virus.

Nipah is named after the village in Malaysia where it was first identified in the late 1990s. The symptoms are brain swelling, headaches, a stiff neck, vomiting, dizziness and coma. It is extremely deadly, with as much as a 75% mortality rate in humans, compared with less than 1% for SARS-CoV-2. Because the virus never became highly transmissible among humans, it has killed just 300 people in some 60 outbreaks.

One critical characteristic kept Nipah from becoming widespread. “The viral load of Nipah, the amount of virus someone has in their body, increases over time” and is most infectious at the time of death, said the Bozeman lab’s Plowright, who has studied Nipah and Hendra. (They are not coronaviruses, but henipaviruses.) “With SARS-CoV-2, your viral load peaks before you develop symptoms, so you are going to work and interacting with your family before you know you are sick.”

If an unknown virus as deadly as Nipah but as transmissible as SARS-CoV-2 before an infection was known were to leap from an animal into humans, the results would be devastating.

Plowright has also studied the physiology and immunology of viruses in bats and the causes of spillover. “We see spillover events because of stresses placed on the bats from loss of habitat and climatic change,” she said. “That’s when they get drawn into human areas.” In the case of Nipah, fruit bats drawn to orchards near pig farms passed the virus on to the pigs and then humans.

“It’s associated with a lack of food,” she said. “If bats were feeding in native forests and able to nomadically move across the landscape to source the foods they need, away from humans, we wouldn’t see spillover.”

A growing understanding of ecological changes as the source of many illnesses is behind the campaign to raise awareness of One Health.

One Health policies are expanding in places where there are likely human pathogens in wildlife or domestic animals. Doctors, veterinarians, anthropologists, wildlife biologists and others are being trained and training others to provide sentinel capabilities to recognize these diseases if they emerge.

The scale of preventive efforts is far smaller than the threat posed by these pathogens, though, experts say. They need buy-in from governments to recognize the problem and to factor the cost of possible epidemics or pandemics into development.

“A road will facilitate a transport of goods and people and create economic incentive,” said Walzer, of the Wildlife Conservation Society. “But it will also provide an interface where people interact and there’s a higher chance of spillover. These kinds of costs have never been considered in the past. And that needs to change.”

The One Health approach also advocates for the large-scale protection of nature in areas of high biodiversity where spillover is a risk.

Joshua Rosenthal, an expert in global health with the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health, said that while these ideas are conceptually sound, it is an extremely difficult task. “These things are all managed by different agencies and ministries in different countries with different interests, and getting them on the same page is challenging,” he said.

Researchers say the clock is ticking. “We have high human population densities, high livestock densities, high rates of deforestation — and these things are bringing bats and people into closer contact,” Plowright said. “We are rolling the dice faster and faster and more and more often. It’s really quite simple.”

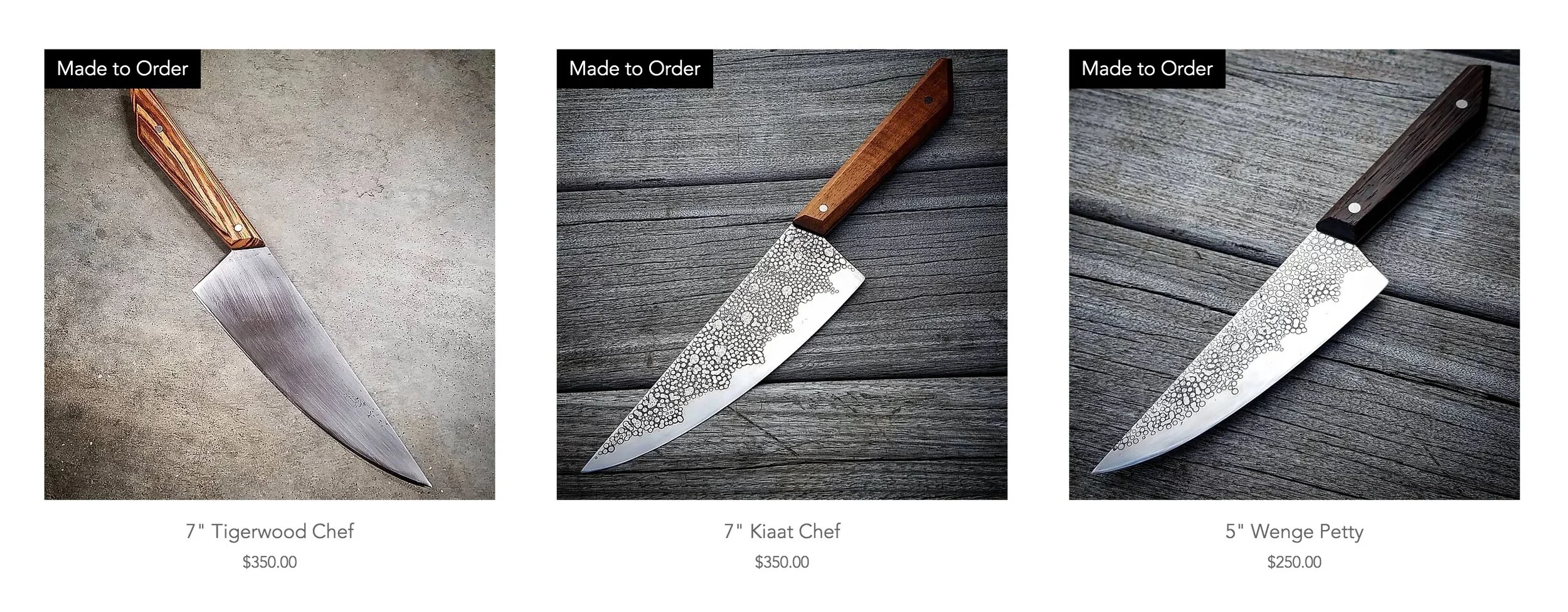

William Morgan: Cutting-edge artisanship at a family homestead in rural Maine

Hannah and Chris Blackburn outside their cutting-tool-making workshop, in New Gloucester, Maine

— All photos by William Morgan

My wife recently bought herself a kitchen knife. Carolyn has dozen of blades suited to all kinds of cooking and pottery, including the stained and pitted Sabatier that she found at a yard sale a quarter century ago. But this piece of cutlery from Maine was different. It cost far more than she could afford, but it was so beautiful, such a work of art, that she could not afford not to buy it.

Really good tools should have stories. Carolyn's new extension of her hand was made of recycled materials: wood from Boston park benches and metal from old saw blades (the recycled 19th Century carbon steel is much stronger than anything available now, and its hard-earned patina is beautiful). That these artisanal tools are sold only at two stores –Strata in Portland and Stock in Providence – reinforces the fact that they’re the products of true craftspeople.

The Blackburns use the steel from old saw blades to make their artisanal knives and other cutting tools.

Full Circle CraftWorks is the commercial face of two art school graduates, trying to build a business while raising a family on a 22-acre homestead in New Gloucester, Maine, a quiet upland town close to, but very different from Freeport, best known for L.L. Bean and other stores, many of them outlets of national chains.

Hannah and Chris Blackburn met as undergraduates at the Rhode Island School of Design, where they were furniture and sculpture majors, respectively. They mastered such skills as welding and sculpting, along with traditional woodworking. Maine native Hannah grew up in nearby Yarmouth, while Chris hails from suburban Washington, D.C. After graduation, the couple remained in the Rhode Island capital.

Providence is a good place for young artists, with lots of colleagues and abundant studio space, but its urban setting was not what the Blackburns wanted for their growing family of two girls and a boy. "The goal was to carve out a simpler life," Chris says, "more directly connected to the environment, the seasons, and all things that sustain our life." One grace note is that the quest for a life based on the land while producing beautiful utilitarian objects is not so different from that espoused by the Shakers, whose last active colony, Sabbathday Lake, is close by in New Gloucester.

Carolyn Morgan and Chris Blackburn in First Circle’s workshop

Their 1985 log cabin on a dirt road came with a two-stall horse barn, which they converted into a workshop, complete with enough of the tools needed to fashion the exotic woods from around the world and the redundant saw blades from barns and country auctions into their handsome tools.

The future success of Full Circle would let these artists live from their sales, but right now their main goal is raising a family on what they hope will become a thoroughly sustainable operation. As a result, much of their life is focused on the rigorous, endless day-to-day and seasonal activities of a working farm.

Just a mention of the Full Circle’s livestock – three goats, seven ducks and a score of chickens, guarded by a dog to guard against coyotes, bears and other predators – ought to be reminder enough that self-sufficient farm life is far from simple or romantic. In the spring, piglets, turkeys and more laying hens augment the permanent stock. Bow hunting deer in the autumn provides much of the family's meat.

There is a small greenhouse, a fruit orchard and gardens for a variety of crops that will grow in Maine. The house and workshop are heated solely with firewood harvested on the property, where sugar maples are tapped to make syrup. Through all the seasons the three young children, aged nine, seven and five, help with chores, from planting and harvesting, to stacking firewood and feeding the animals.

Demanding as farm life is, it does not preclude the family's engagement with the local community. The Backburns host an annual July pig roast that draws scores of friends and neighbors. Their two daughters act in plays put on by the local youth theater, where Chris is a set designer and member of the build crew. The Blackburn children go to a Montessori-type charter school, even as important life lessons come from being part of the agricultural enterprise that helps sustain them.

A hand saw once used in Massachusetts apple orchard or a large circular blade from a Vermont sawmill, along with wood repurposed from repairing their cabin's porch or from an Indonesian rainforest, are transformed into utilitarian but strikingly handsome tools. Whether Hannah and Chris are fashioning a cleaver or a chopping blade, their handmade tools express a worldview that respects the land and the dignity of hard work.

When Chris saw Carolyn's knife again, he said, "It's getting good use; I can tell by the patina. I much prefer that. Some people see them as precious, but tools need to be used."

William Morgan, based in Providence, is an architecture writer, essayist and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, in New Gloucester. It was founded in 1783 by the United Society of True Believers at what was then called Thompson's Pond Plantation. Today, the village is the last of some over two-dozen religious societies, stretching from Maine to Florida, to be operated by the Shakers themselves. It comprises 18 buildings on 1,800 acres.

Making local government work

Boston’s City Hall, opened in 1968 and whose Brutalist architecture remains hated by many.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘’Those cynical about government’s capacity to help people would do well to watch famed documentary-film maker Fred Wiseman’s new movie, City Hall, about municipal government in Boston. That government, now ably led by Mayor Marty Walsh, as it was before him by Tom Menino, has been a fine example of city officials who listen to all parts of the vastly diverse population that it’s charged with serving.

The film, sometimes tedious, sometimes fascinating, shows city employees at all levels doing their often difficult and frustrating jobs with dedication. And the higher-ups don’t sugar-coat the city’s (one of America’s wealthiest) racial, socio-economic and other disparities while providing specific ways to address them.

There’s a moving segment with Mayor Walsh, in front of a veterans group, discussing his past struggles with alcoholism. He’s not particularly articulate but he’s very open.

As for the partisan remarks in the film, Mr. Wiseman says:

"City Hall is an anti-Trump film because the mayor and the people who work for him believe in democratic norms. They represent everything Donald Trump doesn't stand for."

'Can't fill a house'

All out of doors looked darkly in at him

Through the thin frost, almost in separate stars,

That gathers on the pane in empty rooms.

What kept his eyes from giving back the gaze

Was the lamp tilted near them in his hand.

What kept him from remembering what it was

That brought him to that creaking room was age.

He stood with barrels round him—at a loss.

And having scared the cellar under him

In clomping there, he scared it once again

In clomping off —and scared the outer night,

Which has its sounds, familiar, like the roar

Of trees and crack of branches, common things,

But nothing so like beating on a box.

A light he was to no one but himself

Where now he sat, concerned with he knew what,

A quiet light, and then not even that.

He consigned to the moon—such as she was,

So late-arising—to the broken moon

As better than the sun in any case

For such a charge, his snow upon the roof,

His icicles along the wall to keep;

And slept. The log that shifted with a jolt

Once in the stove, disturbed him and he shifted,

And eased his heavy breathing, but still slept.

One aged man—one man—can't fill a house,

A farm, a countryside, or if he can,

It's thus he does it of a winter night.

“An Old Man’s Winter Night,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Tim Faulkner: What next for Transportation Climate Initiative?

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The regional collaboration known as the Transportation & Climate Initiative (TCI) will be operating, at least initially, with a smaller cast than expected.

Governors from Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut, as well the District of Columbia’s mayor, signed an agreement Dec. 21 to launch an effort to address the climate crisis. This cap-and-invest system is designed to reduce climate emissions by raising money from the wholesale distribution of gasoline and diesel fuel and investing the proceeds in electric-vehicle infrastructure and other initiatives that make up the so-called “green transportation economy.”

TCI is composed of 13 East Coast states and the District of Columbia, but only the three states and the nation’s capital signed the recent memorandum of understanding to establish the revenue-generating system. Most other TCI member states had previously signed a separate letter expressing support for the program. Maine and New Hampshire didn’t sign on to that earlier letter. All TCI members can adopt the cap-and-invest program at any time.

During an online press call, no explanation was offered as to why the other states aren’t joining the pact. Representatives from the three states and the District of Columbia instead described how the anticipated reduction in climate emissions, along with the economic growth they expect, will entice states to eventually participate.

“This is a strong group moving forward in a committed way,” said Kathleen Theoharides, secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. “And we believe the future is bright and that if you build it they will come.”

Katie Scharf Dykes, commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection, predicted that TCI will increase state participation, as did another cap-and-invest program that generates revenue from power-plant emissions, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

“I’m confident that we will see more jurisdictions joining us,” Scharf Dykes said.

If local approvals are met, TCI is scheduled to launch in 2022 with a one-year trial reporting period that will track emissions for each state and the District of Columbia. Fossil-fuel distributors won’t have to buy the pollution allowances until 2023, when they are required for exceeding a monthly emission limit, or cap. The limit is reduced each year until 2032, when it will be 30 percent lower than the initial cap.

During the recent press call, representatives from the three states and District of Columbia touted the benefits of investing some $3.2 billion over nine years in electric buses, electric-vehicle charging infrastructure, and new bicycle lanes, walking trails, and sidewalks.

Some $3.2 billion will be invested in low-carbon transit projects in four regions over nine years. (TCI)

“Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and D.C. are committing to bold action to achieve our ambitious emission-reduction targets while positioning the jurisdictions and the region to grow our clean transportation economy,” Theoharides said.

The auction of the allowances is expected to raise about $300 million annually. Rhode Island anticipates receiving about $20 million a year. As part of the program, at least 35 percent of the proceeds must be invested in environmental-justice communities. Spending in these frontline communities is expected to create jobs, reduce air pollution, and improve public health.

If fuel distributors pass the cost on to consumers, the expense is expected to add between 5 and 9 cents to a gallon of fuel.

The program’s requirement for equity investment is intended to address the regressive nature of the higher fuel costs by investing in communities suffering from excessive air pollution. Statewide equity advisory boards comprised mostly of members from these communities will recommend where and how the TCI funding is spent.

“Most importantly, (TCI) will provide much-needed relief for the urban communities who suffer lifelong health problems as a result of dirty air,” Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo wrote in a prepared statement.

The program is expected to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions from the transportation sector by some 26 percent over nine years. Transportation accounts for 42 percent of all emissions among the signors, the largest source of emissions in those areas.

The announcement comes a year after TCI was expected to launch. TCI representatives blamed the delay on the heath crisis and an unfriendly White House administration. Public perception was also a likely cause for delay. Opposition to TCI from conservative news outlets and radio talk-show hosts has persisted.

Rhode Island acknowledged at a meeting in 2019 that TCI will take more than a government directive to succeed.

“If we’re going to win hearts and minds, it’s not just people at the Statehouse,” said Carol Grant, then director of the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources. “We have to kind of win people over generally to the importance of this.”

Back then, environmental groups criticized TCI for not advancing stronger reductions in emissions. Reaction to the recent announcement from the same environmental community has been positive. Support for the TCI program has been expressed by Save The Bay, Acadia Center, and the Northeast Clean Energy Council.

A new president committed to taking on climate change improved the prospects for enacting the TCI program, according to coalition members.

“With a change in administration, policies are going to be a lot more stable,” said Terrence Gray, deputy director for environmental protection at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Janet Coit, DEM’s executive director and the state’s representative during the online announcement, noted that states with Republican and Democratic governors are TCI members.

“After so much divisiveness, it’s really great to see bipartisan regional effort leading on climate change,” Coit said.

The public response to the program will likely determine the willingness of other states to join. A recent poll conducted by Yale University and George Mason University among voters in TCI states and the District of Columbia found that 41 percent said they strongly support participation in the initiative. Another 31 percent said they would somewhat support participation. Rhode Island had the highest support at 61 percent. Maine was the lowest at 56 percent. Politically, 84 percent of Democrats favored joining TCI, while 49 percent of Republican favored joining the initiative.

Public perception starts with messaging. The revenue mechanism is often referred to by opponents as a “gas tax” or fee paid by consumers. But it has several distinctions, according to the renewable-energy advocacy group Acadia Center.

First, some fuel-distribution companies may choose to internalize part or all of the allowance costs to gain a competitive advantage rather than pass it on to gas-station customers. And since TCI is based on the carbon content of a fuel, suppliers will be able to sell fuels with lower carbon contents and pay less in carbon pollution fees, according to Acadia Center.

“This program is about delivering benefits to consumers with a transition in fuels and mobility options over time,” said Hank Webster, staff attorney and Rhode Island director for Acadia Center.

TCI will have a minimal impact, if any, on fuel prices, Webster said, because the program is designed to keep that impact at or below 5 cents if regional fuel suppliers choose to pass the costs on to their customers.

“To put that in context, you can save 5 cents per gallon at some stations by using their frequent customer program, or 10 cents per gallon by setting up a direct debit from your checking account,” he said.

Rhode Island and Connecticut require legislative approval to launch the TCI program. Massachusetts can advance the program through its executive office.

Raimondo is expected to launch the legislative process this spring, with public input beginning in January.

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI News.

— Photo by Felix Kramer

Patricians vs. plebians

The town green in Douglas, Mass. Town greens (or “commons”) are town-owned land in New England.

“There arose … in every New England village community the same strife between old resident and newcomers as that between the patricians and plebians of ancient Rome; the old settlers claimed a monopoly of the public land and the newcomers demanded a share.

— Herbert Baxter Adams (1850-1901), historian and educator, in The Germanic Origins of New England Towns

--

When God made Boston

“City Rain” (encaustic, toner transfer on panel), by Heather Douglas, who lives in Rockland County, N.Y., and Vermont. She says:

“I see my work in part as documentary and in part as experimental. Many of my pieces are distillations from photographs I’ve taken of people on city streets. As times change, people and environments change. I aim to capture that landscape.

“In contrast my abstract pieces have no predetermined outcome but emerge from experimentation, influence from nature, and a place from within.’’

See:

http://www.heatherdouglas.com/index.html

and:

newenglandwax.com

“I guess God made Boston on a wet Sunday.’’

— Raymond Chandler (1888-1959), Anglo-American detective novelist and screenwriter

Hear/read an hour of Trump's brazen, sociopathic corruption

Our desperate caudillo at work: Hit this link.

Jill Richardson: It’s past time to toss Trump’s huge lies about immigrants

Preparing for an immigrant-naturalization ceremony in Salem, Mass.

Via OtherWords.org

As Donald Trump leaves office, it’s worth remembering how he first launched his campaign: by calling immigrants “murderers” and “rapists.”

This was outrageous then. And there’s more evidence now that it was, of course, false.

A new study finds that “undocumented immigrants have considerably lower crime rates than native-born citizens and legal immigrants across a range of criminal offenses, including violent, property, drug, and traffic crimes.”

The study concludes that there’s “no evidence that undocumented criminality has become more prevalent in recent years across any crime category.” Previous studies found no evidence to support Trump’s claim, but now we have better data than ever before.

Put another way, Trump was telling a dangerous lie.

Sociologists Michael Light, Jingying He and Jason Robey used crime and immigration data from Texas from 2012 to 2018 to find that “relative to undocumented immigrants, U.S.-born citizens are over 2 times more likely to be arrested for violent crimes, 2.5 times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, and over 4 times more likely to be arrested for property crimes.”

Unfounded accusations of criminality are a longstanding tool of racism and other forms of bigotry across a range of social categories.

When anti-LGBTQ activist Anita Bryant wanted to discriminate against gays and lesbians in the 1970s, she claimed they molested children. More recently, when transphobic people wanted to ban trans women from women’s bathrooms, they falsely claimed that trans women would rape cisgender women in bathrooms.

Consider how much anti-Black racists justified their actions in the name of “protecting white women” from Black men. In 1955, a white woman, Carolyn Bryant Donham, wrongly claimed that a 14-year-old Black boy, Emmett Till, grabbed her and threatened her. White men lynched Till in retaliation. More than half a century later, Donham revealed that her accusations were false.

In 1989, the Central Park Five — five Black and Latino boys between the ages of 14 and 16 — were wrongly convicted and imprisoned for raping a white woman. They didn’t do it. In 2002, someone else confessed and DNA evidence confirmed it. (Trump, who took out full-page ads calling for their execution then, never apologized.)

Racism and bigotry are about power and status. Yet instead of openly admitting that some groups simply want power over others, most bigots find reasons that sound plausible to the uninformed — even if the reasons are completely untrue. Bigotry is much easier to market if it can masquerade as fighting crime.

It wasn’t just Trump himself. During the Trump administration, officials like the U.S. solicitor general argued before the Supreme Court that undocumented immigrants are disproportionately likely to commit crime. Data: None. Claims: False.

As the late New York U.S. Sen Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously said, “You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts.”

So when you hear a claim that a particular group of marginalized people are criminals, question it. What is the evidence for the claim? What is the evidence against the claim? Why is the person making the claim, and how will they benefit if people believe them?

If someone cites research, who performed the research, and who funded it? Do the funders have a financial stake in the research findings? Was it published in a peer-reviewed journal? Is the data publicly available for others to replicate the findings?

In this case, the research debunking this racist lie was government-funded, peer-reviewed in a major journal, and the data is available to the public.

Hearing that particular group of people poses a threat to your safety can be frightening. But because such claims have been used throughout history to spread bigotry against marginalized groups, they should always be fact-checked.

In this case, the evidence is clear. Trump stoked anti-immigrant sentiment in the name of fighting crime, and his claims were baseless and false. The lie should end with his presidency.

Jill Richardson is a sociologist.

It has worked

“It looks like we will always be together

And every day I realize anew

We never really had a thing in common

Except we were the best that we could do.’’

— From “The Best That We Can Do,’’ by Geoffrey Blanchette, in The Poets of New England

Heroic trees

“Willow Heights Trail #2’’’ (gouache on panel), by Vicki Kocher Paret, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Jan 8-31

The Cambridge-based painter says:

"My hero: nature, trees, pretty much the natural world. It has the power to support and heal the environment, and provide peace and spiritual healing with its endless diversity and beauty. It inspires and I strive to capture these powers in my paintings."

Keeps them humble

Walpole, N.H., Town Hall

“Walpole, New Hampshire, is small enough for us to keep that mom-and-pop feeling. The town reminds us every day of the power of history. And it’s important to stay in a place where whatever notoriety you get, plus fifty cents, will buy you a cup of coffee.

— Ken Burns, history documentary show impresario on PBS, in Yankee magazine July/August 2002 on being based in Walpole.