A 'flat push'

“Outside the snow comes rolling in

from the flats of Quebec. It’s the flat push

on things I fear. The north glass

rattles and bulges….’’

— From “Storm,’’ by John Engels (1931-2007), a Vermont poet. He taught at St. Michael’s College, in Colchester, just north of Burlington.

“Allegory of Winter,’’ by Jerzy Siemiginowski-Eleuter (1683)

St. Michael’s College

The joy and pathos of life

“Garden hose and deck, Ryegate VT, July, 2019” (archival digital print) in Mary Lang’s show “Small Moments of Sad-Joy,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Dec. 8-Jan. 17.

The gallery says:

“Mary Lang reflects on the Japanese phrase ‘Mono no Aware,’ the pathos of things, in her newest collection of photographs. A garden hose draped over a railing, a field of Queen Anne’s lace at dusk, the arc of a sprinkler all speak to the entrenched feeling of wistful sadness. That fundamental reality builds its foundation on uncertainty. These photographs are not from distant or grandiose places but show quiet, fleeting moments in her backyard, around the corner from her house, and at friends’ yards in Upstate New York and Vermont. Lang borrows the term ‘sad-joy’ from Chӧgyam Trungpa, to describe the joy of being alive while still in touch with the suffering and impermanence of the world. In this exhibition, Lang asks the viewer to consider, feel, and marvel at the pathos of things.’’

In Vermont, fighting the virus and killing the game dinner

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

Vermont, under the firm leadership of old-fashioned moderate (and anti-Trump) Republican Gov. Phil Scott, has been a leader in controlling COVID-19 through tight travel/quarantine rules, adherence to face-mask rules and, probably most important, the Green Mountain State’s traditionally strong, unselfish civic sensibility. Now, as the virus explodes around America, it faces new challenges. States can’t post the National Guard at all roads leading into their states to check for possibly infected travelers from high-risk places! But I’m pretty sure that Vermont will face its COVID challenges decisively and effectively.

xxx

Of course, some would say that the fact that Vermont is a largely rural state makes it easier to control the spread of COVID-19. But look at how terrible the rural Red States, such as in the Great Plains, are doing with it! And consider that Vermont is in the Northeast, the nation’s most densely populated region.

A kitchen interior with a maid and a lady preparing game, c. 1600.

\

I try to avoid eating animals, especially my fellow mammals, but I’ll miss (well, in a way) the annual game dinner at the Congregational church in Bradford, Vt., which has been cancelled, perhaps permanently, after 64 years. I had attended, off and on, with a bunch of friends since 1989. I went after friends’ annual relentless urgings that I join them.

The proximate cause of the cancellation, of course, was the pandemic. Couldn’t have all those folks sitting shoulder to shoulder at those long, communal tables. But before COVID, the church had had increasing difficulty in getting people to work at the event, the church’s biggest annual fundraiser.

Another little piece of Americana goes down.

In Bradford, once a thriving small manufacturing town, originally because of water power: Woods Library and Hotel Low, c. 1915 postcard view.

Growing up 'underexposed'

“My parents were both from Vermont, very old-fashioned New England. We heated our house with wood my father chopped. My mom grew all of our food. We were very underexposed to everything.’’

— Geena Davis (born 1956), actress. Though her parents were native Vermonters, Ms. Davis grew up in Wareham, Mass., at the northern end of Buzzards Bay. So she may be exaggerating a tad.

Entering Wareham, Mass., “The Gateway to Cape Cod.’’

Suresh Garimella: UVM's role in helping Vermont recover from COVID crisis

Named for U.S. Sen. Justin Smith Morrill, Morrill Hall at the University of Vermont was built in 1906-07 as the home of the UVM Agriculture Department and Agricultural Experiment Station.

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BURL.INGTON, Vt.

Gracing the back wall of my office at the University of Vermont is an antique wooden desk that’s more than 150 years old. While it’s an undeniably handsome piece of 19th Century craftmanship, it serves much more than a decorative purpose.

As the desk of Vermont Sen. Justin Smith Morrill, the author of the Morrill Act of 1862, which established the country’s first land-grant universities, it is my lodestar, a vivid reminder of UVM’s status as one of the nation’s earliest land grants and of the solemn responsibilities that come with that designation.

Count me as a true believer in the land-grant mission and among its greatest fans. The first land grants, so called because the U.S. government donated federal land to each state to establish a university, were a brand new idea: higher education for everyday people focused on the practical subjects of agriculture and the mechanical arts, whose purpose was to improve the economic and cultural well being of the people in their state.

Why am I so passionate about UVM’s land-grant mission? Because Vermont, as much as any state in the nation, faces a series of daunting challenges—from population decline to stagnant economic growth—that a land-grant university like UVM is powerfully equipped to address.

In the middle of a pandemic that has rendered these challenges even more acute, there is another reason to believe in the land-grant mission. Land grants like UVM have a key role to play in helping their states recover economically from the ravages of COVID-19.

The economic impacts of the pandemic are indeed unprecedented. In the second quarter of 2020, the national economy shrank at an annualized rate of nearly one-third. Millions of jobs were lost in New England. And in Vermont, despite the state’s lowest-in-the-nation infection rate, unemployment in July was 8.3 percent, and the state has the highest budget deficit in its history.

How can land-grant universities help spur economic recovery in their states? In Vermont, we’re looking at bringing the power of the university to bear on these challenges in a number of ways.

We’ll take full advantage of one of UVM’s most important resources: our bright and capable students. In a post-COVID economy, employers—from tech firms to media companies to nonprofits—will be in dire need of eager-to-learn, dependable, qualified employees. To meet this need, we’ll significantly enhance our internship programs, so more students, beginning in their first year, can be exposed to career options in the state by interning with a Vermont employer. Just as important, we plan an active outreach and education campaign to employers, so they know how to connect with and engage our talented students.

We’ll harness the strength of another great university resource: the talents of our faculty, who last year brought over $180 million in research funding to the university. In the coming months, with support from our faculty, we will help businesses around the state apply for federal Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grants, proven ways to help businesses grow.

We plan a concerted and sustained effort to attract our out-of-state alumni, a high percentage of whom are entrepreneurs, back to Vermont, a state they love, providing them with technical assistance so they can relocate their companies, envision new ways of working from home or start new businesses here.

We’ll mobilize the intellectual firepower of our faculty to help policymakers craft local and state programs that address socioeconomic challenges the state is facing, which hold back wellbeing and prosperity. In a survey of food insecurity in the state, for instance, faculty learned that some Vermont residents were stockpiling food and depriving those in need—a problem that informed policy can alleviate.

We’ll deploy the pedagogical and human development expertise of faculty in our College of Education and Social Services to help Vermont’s K-12 teachers better engage primary school students as they emerge from a remote learning environment and better understand how distance learning, enhanced internship and place-based learning opportunities can help keep college-bound high school students on track.

For many of these efforts, we’ll coordinate with UVM Extension. In an expansion of their traditional role, Extension faculty and staff will act as our on-the-ground implementation agents for community economic development.

As important as these programs are in spurring economic recovery, their impact would be muted without another initiative just funded by the state: UVM’s new Office of Engagement.

The office will function as the front door to the university, with staff who field inquiries from businesses and residents across the state, connecting them with appropriate resources and expertise at UVM.

While the university has a critical role to play in Vermont’s post-COVID recovery, its role in promoting the state’s well being stretches far beyond the current crisis.

Boosting the health, quality of life and prosperity of Vermont and Vermonters is one of the three core imperatives in the university’s recently released strategic vision, Amplifying Our Impact.

The strategic vision continues UVM’s long tradition of engagement with the state. During my tenure, we will become even more deeply engaged with issues of concern throughout Vermont.

The historic wooden desk I keep close by will continue to inspire me. With the help of this daily reminder, I will ensure that UVM’s land-grant mission—to help the state confront both our current challenges and those to come, shaping a bright future for all Vermonters—remains a top priority for Vermont’s university.

Suresh Garimella is president of the University of Vermont.

UVM seal

Don't tell me you didn't see the sign!

“I hadn’t been in Vermont very long, but I’d been there long enough to know what any Vermonter worth his salt would think of {being on his property}. Trespassing on someone’s land was tantamount to breaking into his house.’’

— Donna Tartt (born 1963), novelist, in The Secret History (1992). She studied at Bennington College, in southern Vermont.

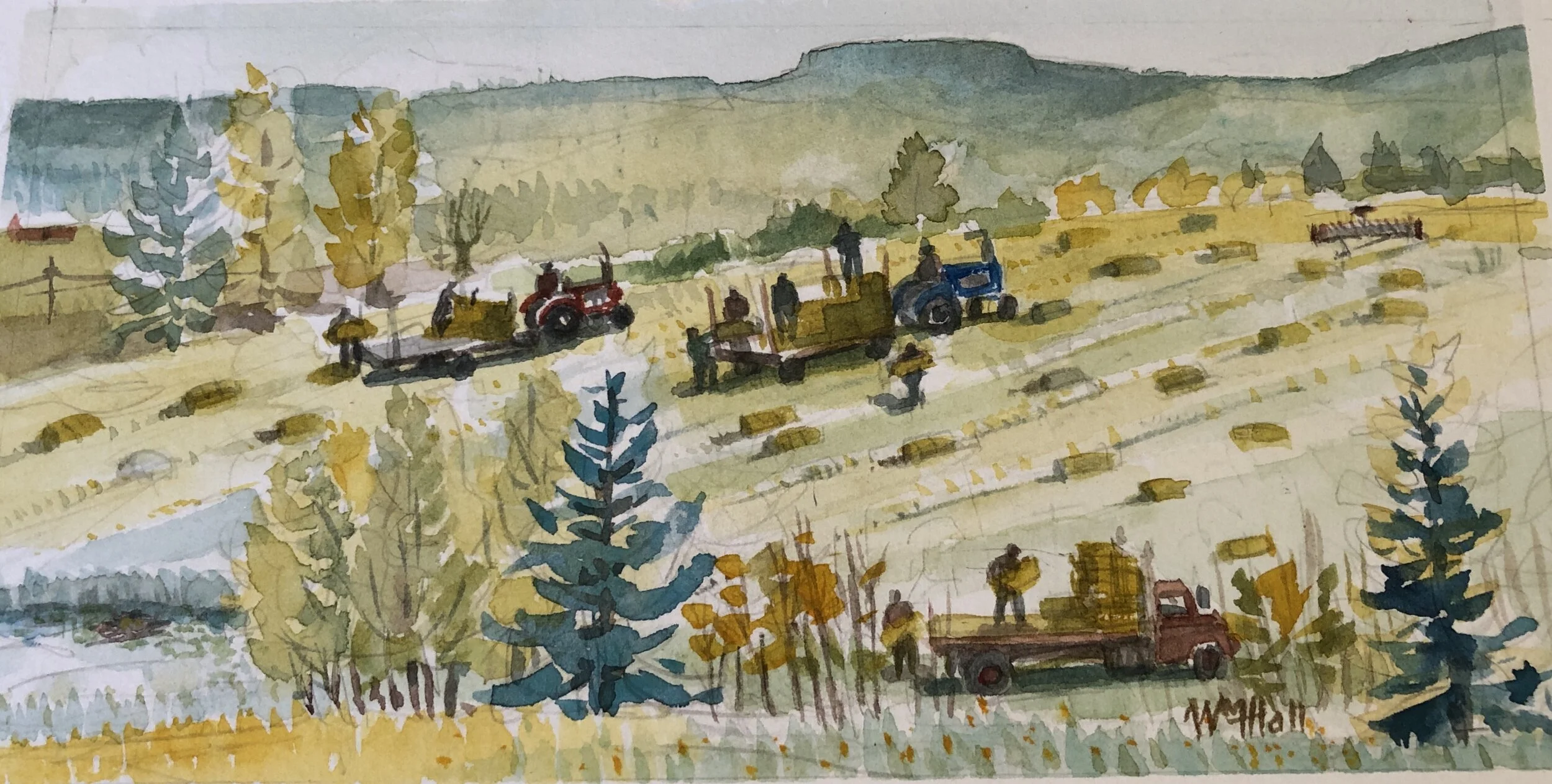

Bill Hall: The big gamble of 'early haying' in Vermont

“Harvesting the Hay Crop on Deadline’’

— Watercolor by Bill Hall

In late May it could get hot in Vermont’s Connecticut River “Upper Valley’’. You shifted slowly from here to there, but you had to move. If you didn’t you’d swear you would suffocate. You weren’t avoiding the oppressive heat as much as you were looking for some air to breath. Shade didn’t help much; it only served to dull the searing brightness. The heat was just there. If you were a farmer you had to get used to it, and get things done anyway. One of those things might have been to get in the early (season’s first) crop of hay: “early hay”.

In that sudden sweltering heat, you had to decide:

“Hay or no hay”?

Once you decided to hay, you had to do it fast. After the brutality of winter and the torrents of “mud season,” after the financial reality of dairy farming sank in once again, you had to get moving. You might put off the question of buying new equipment by fixing the old. Or should you pay down your loan?

Farmers in the Connecticut River Valley had to weigh the costs and rewards of throwing the dice once again. Would they risk an early haying or would they fold and walk away? That was the big gamble.

Early hay or “spring mow” sounds simple enough to a non-farmer. The common question asked, “Is it possible?” The correct answer is, “No, in most cases,” due to weather, which is always uncertain in northern New England. “Then, is it necessary,” you might ask?

In some professions, such as insurance, determining possibilities is a scientific matter, but in farming it’s just called “gambling”. My street-smart father called it “ The Farmers’ Hat-Trick”. He explained it to my brother and me as he shifted three dried butternut half-shells around on the kitchen table in short quick movements, one shell concealing a dried pea seed. You know this game. Which shell hides the pea? This was to demonstrate how, by a game he called “slight-of-hand,” farmers plotted to sneak a full barn of early hay right out from under the nose of a vengeful God.

My brother and I did not realize we were also getting a lesson about my father’s religious beliefs, seasoned by his ironic sense of humor. He was a traveling farm-equipment salesman who served a big territory. He understood farming, but elected to travel in a wider circle of go-getter types. He was also kind and sympathetic. By the end of the lesson he had impressed upon us how daring farmers were for trying to beat the heavy odds against succeeding at a harvest of early hay while it was still mud season. Dad called a career that required dealing with weather “a fool’s guess”. We also learned why we were lucky to be able to watch and understand this unfolding lesson where we could see it, in our own pastures. But we were safe from the financial challenges. My father traded the hay to our neighbors, the Vaughans, just to get our fields hayed, addressing the need to keep out brambles and weeds that cows shouldn’t eat, and to provide us with enough hay for our modest needs, which were for bedding, fodder and scratch hay for my grandfather’s turkeys and chickens (and their eggs)

Quirky local weather is king

Vermont has many microclimates, in part because of its geological history. Small farmers work every inch of that glorious land from the highest pastures of the Green Mountains to the floor of the Connecticut River Valley. Our 50-acre farm lay like a door-mat on the fertile plain of that valley, but the rush to harvest an early hay, or the decision not to attempt it, was happening everywhere in our little state, and all at once.

We would get news from Father’s weekly travels about the haying elsewhere. “They’re still not mowing in the Champlain Valley” maybe he’d report. He had seen bales in a high pasture over in the Vershire Hills, just west of us, but they were covered with snow and so on. Our total focus was on our two flat 25-acre fields, one on each side of our farm house. We knew from the farm kids at school that other farmers were ramping up to mow, rake, flip, dry and bale new hay everywhere around us, as soon as the weather permitted.

My father joked that if God controlled the weather then he was the one who needed to be appeased, fooled, dazzled or distracted. “He can be a practical joker at times,” he said, winking. The question was, if a farmer was going to sneak in such a neat stunt as an early hay harvest shouldn’t the farmer be very careful? If God knew, might he put obstacles in the farmers’ way? As our minister said, “To test him, to test his devotion”? It seemed like there was a, “side bet” between our dad and “Our Father”.

The tension was growing.

It was pre-spring. The days alternated between snow and mud. Most farmers were gun-shy and dazed by the deep dark winter they had just endured. Already skeptical about the benevolence of their God, a farmer could get discouraged from being house-bound and barricaded in their dark barns all winter dealing with rodents, frozen pipes and coughing cows. When the farmers returned to their kitchens, wives were waiting with “payable notices” illustrating the folly of a farming life. They felt vulnerable. The prospect of an early haying seemed further away than ever, but then it did every year.

Mud season was next. It held hands with winter. Those two soulless bullies worked together to test farmers’ resolve. Farmers felt helpless in their grip, and the sun seemed in cahoots with those darker elements of life because it offered only a few short winks in early May. “Was this spring”, they asked? It sleeted in April and froze tight every night for days sometimes, and maybe served up a blizzard for breakfast. Levity and faith were long gone by the time that the spring mud started to shift consistency from stinking brown glue in the barnyard to something more solid. But the fields were still soaking wet.

Wet fields? Were they the death warrant for early hay crops? A wet field normally meant one inaccessible to heavy farm equipment, and therefore useless until dry, but with a little luck and intense sunshine the ground might give rise to the green gold of the grass seeds within. If they could just get enough sunshine those seeds would explode to become a free bonanza of green early hay, but only in a field dry enough to work in. A windfall crop of sweet green hay would feed a farmer’s cows until the second haying season, in July, and would ensure that no hay need be purchased in the upcoming calendar year.

In Vermont the “early hay’’ was originally called “early mow’’. It was not baled. Teams of as few as two and sometimes as many as six work horses or mules hauled a man around who worked with horses, a “teamster,” upon a wood-frame contraption that combined pre- and post-industrial wood and metal embellishments. The wooden frame was as elegant as any stage coach and the iron parts included shiny as well as rusty parts, such as shearing bars, worm gears and iron seats.

The early mowers worked mechanically like a thousand men with sickles to lay the new grass low. Horse-drawn mechanical flippers or men with wooden rakes turned the grass over, on the same day it was mowed. This, done properly, dried out the hay enough to be “put-away”. Horse-drawn wagons were filled to the tops with loosely piled hay, which was lifted up using mechanical pulleys to be placed drooping over drying beams in the tops of barns, where the hay’s sweet perfume cleansed the stale air from the winter just passed. It was said such a barn was made “happy” by new hay. Cows’ eyes bulged upward as they bellowed in the milking level below as if trying to see through the floor above to the new hay they longed for.

This horse-powered equipment provided an advantage in its day. It could be operated in soaked fields before mud season had subsided, allowing access to wet fields without damaging them, as the weight of modern tractors, balers and trucks would have. Waiting for the proper surface conditions in those fields is what made the modern early hay process such a crap shoot .

Hay could be harvested when it was ready without farmers having to wait for equipment and manpower to converge on a field en masse. It could be gradually harvested more times during the season as it grew. The process was more controllable and flexible.

Above all it was a soulful process for both man and beast. There are still a few Vermont farmers who maintain horse and mule teams and the revered equipment that goes with farms with horses. Admiring them are amateur teamsters, purists, history buffs and people who still prefer the music of men’s voices coaxing animals forward to the sound of diesel tractors and metal balers. In some areas, drivers still park their cars along dirt roads in silent observance of this sacred event. But farming with horses has come to be seen as too slow and out of step with the times.

For the modern farmer and his quest for that early hay, he could only hope that his organizational skills and gambling spirit would see him through. These days, there are detailed weather predictions, radar and and satellite maps to show the regional picture, but it’s his personal experience and knowledge of his region that best tell him when to cut his hay. In our case in Thetford everything was temporary and nothing was as it seemed. It’s complicated. It tests your commitment. It leads you on. It dares you.

Is there enough time?

The fog over the valley floor and the heavy moisture it brings almost every day will dissipate by 9 a.m. if the sun is shining. Then will come a breeze. The heat of the sun on the valley floor will cause up-drafts, which will flow west through the hills of Vermont or east toward the hills on the New Hampshire side. In between is some of the most fertile soil in New England. The question is, can you wait for the sun to do its work and can you commit manpower and other resources enough to get the job done in time? If the farmer has his own hay-processing equipment, no matter how advanced, from cutting to storage, he’s in a stronger position; no one can let him down if he does it himself.

When it came to our two fields we aced it, but it was close. When the weather report said “no way” we had it hayed anyway. The Vaughan family, our aforementioned neighbors, made it happen. They arrived en masse when they saw that the rain that had been predicted for that morning did not fall. Sunny skies were forecast. The Vaughans made a commitment to cut both of our fields that day. They’d flip and rake them alternately and move from one field to another with Big-Red, the baler. We could see that there was still standing water near the fire pond (a source of water to put out barn fires) behind the barn. That area would be dry by midsummer and would have to wait.

The intense ‘baling day’

The Vaughans used two cutting tractors to get the hay down fast; both were working simultaneously. The flipper and rake alternated between the two fields.

Then came “baling day”. One year, the sky was overcast and the forecast was for rain by noon. As we had to wait for the morning dew to dry off, we were worried, but committed. The Vaughan family patriarch was unconcerned. Robert Vaughan Sr., who looked like someone in a Vermeer painting, decided that the hay would get baled and then stacked in his big barn by the end of that day, and that was that. Even if some of the last bales got a little wet, “We’re doing it”.

Just in case, he directed a couple of his five sons to go to the Vaughans’ barn and set up drying racks, where they’d be exposed to wind from the two enormous fans they had just installed. These fans were six feet wide and made the ends of the barn resemble an aircraft-test wind tunnel. This flow would ensure that our hay would retain its dryness in case the rain fell on the last day before we got the hay stacked. Mr. Vaughan wanted the new hay treated gingerly because it had a high alfalfa content and a limited tolerance to too much jostling.

Unlike with August haying, the alfalfa would stay in this new hay. When dry that early alfalfa would resemble flaked butterfly wings and if handled roughly would flutter down from the bottoms of the bales. This essence of the “first cut” must be maintained, otherwise why bother? Dryness was dicey for other reasons. The “good moisture” content was tricky to maintain, and “bad or deep moisture” would cause rot that would spread to hay around it.

Every bale in that bountiful harvest was loaded and trucked to the barn. The last three truckloads were stacked with the help of headlights of the other trucks and tractor. If we were lucky, the rain that might have been predicted held off until the last truck was mostly filled. A large tarp was fixed over the top and flapped wildly as we drove to the barn, where it was unloaded in the big alley in the center. Everyone helped and so it took only a few minutes. Then the big fans were turned on for the night. The sound that followed the throwing of the main switch gave the event a science-fiction feel. The fans chilled us as the breeze dried our sweaty, itchy backs. We would all seek relief lying in front of those fans in the sweltering days to come.

My brother and I always remember those times when the early hay was brought in.

Bill Hall is an artist based in Florida and Rhode Island. Hit this link.

Thetford, Vt. in 1912

— Photo by Mike Kirby

'Sanity of stone'

The Barre (Vt.) World War 1 Memorial, "Youth Triumphant", by sculptor C. Paul Jennewein. The Barre area is known for its granite and marble industries.

“There under elms in glacial light

Survival forced me to atone:

The heart exchanged its rich excess

For starker sanity of stone.’’

— From “Sojourn in Vermont,’’ by Israel Smith

The Rock of Ages quarry, in Barre, Vt.

— Photo by Mfwills

Flee to the countryside?

Remnant of an old mill in Clayville, R.I.

Vineyard in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where my maternal grandfather grew up on a farm.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some of the last few days have seemed abnormally cold, and they certainly have been mostly gloomy. But in fact temperatures have generally been at, or even a little above normal, the past few weeks. We’d been spoiled by the extraordinarily warm winter, and thus find the normally hesitant New England spring more depressing than usual. Well, yes, there’s the other thing, too…

The current emergency may be making far more people aware of Nature in the spring because far more are walking around outside to battle claustrophobia and to get exercise, partly because most gyms have been closed. But it’s not a very social experience, as, for example, people tend to keep on the other side of the street from fellow walkers. Still, at least they’re looking at the flowers and trees more than they might have in a “normal spring.’’

I’ve been thinking that this would be a good time to head up to New Hampshire and Vermont, get a room at a Motel 6, if I can find one open, and check out the last of this year’s maple-syrup-making operations for a few days. Yeah, COVID-19 will be circulating up there too but the scenery is therapeutic.

An old friend of ours who lives in Florida part of the year has several dozen acres of field and woods in the Clayville section of Scituate, R.I. She only half-jokingly suggested that she’d move full time back to Clayville and “live off the land,’’ as people there (mostly) did 250 years ago. It wasn’t that long ago, historically speaking, that many of our ancestors lived on farms. My maternal grandfather’s family had a couple of farms in Upstate New York, and even some of my New England ancestors in the great-grandparent generation had working farms in Massachusetts. Those who didn’t might have had at least a couple of cows and some chickens.

'Not to be wrenched into meaning'

View of Camel’s Hump from Vermont's Long Trail

— Broken Images

“My objectives this morning were vague.

As always I'd hike these hills—

a way to keep going

against the odds age deals….

“Whatever this trance,

I treasured it as a wonder

not to be wrenched into meaning,

as in Every second counts,

as in You should count your blessings,

though of those there seems no doubt.’’

— From "Mahayana in Vermont," by Sydney Lea

Stick with stasis

“How many Vermonters does it take to change a lightbulb?

Three. One to change it and two to argue over why the old one was better.’’

—Old Vermont joke

“An old man is sitting on the steps of the general store on a fine spring day. A stranger comes along and tips his hat and comments on the beauty of the day. He pauses, searching for something more to say, and finally he says, “Bet you’ve seen a lot of changes around here.’’ To which the old man replies, ‘Ayup. And I’ve been against every one of them.’’’

— From “Pure Vermont,’’ by Edie Clark, in the October 1996 Yankee Magazine.

Peter Certo: So capitalism naturally goes with democracy? Do some research

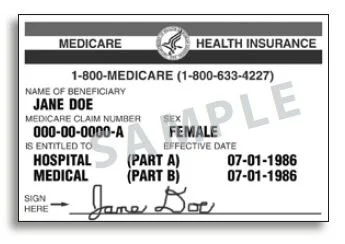

Medicare is a socialistic idea.

From OtherWords.org

For decades, Republicans have painted anyone left of Barry Goldwater as a “socialist.” Why? Because for a generation raised on the Cold War, “socialist” just seemed like a damaging label.

And, probably, it was.

You can tell, because many liberal-leaning figures internalized that fear. When Donald Trump vowed that “America will never be a socialist country,” for instance, no less than Sen. Elizabeth Warren agreed.

But while older Americans retain some antipathy toward the word, folks raised in the age of “late capitalism” don’t. In Gallup polls, more millennial and Gen-Z respondents say they view “socialism” positively with each passing year, while their opinion of “capitalism” tumbles ever downward.

As a result, it’s not all that surprising that self-described democratic socialist Senator Bernie Sanders tops Trump in most head to head polls.

Still, old propaganda dies hard. What else could explain the panicky musings of Chris Matthews, the liberal-ish former MSNBC host, who recently wondered aloud if a Sanders victory would mean “executions in Central Park”?

Nevermind that Sanders is a longtime opponent of all executions, as any news host could surely look up. The real issue is a prejudice, particularly among Americans reared on fears of the Soviet Union and Maoist China, that “socialism” implies dictatorship, while “capitalism” presumes democracy.

Their Cold War education serves them poorly.

Yes, it’s easy to name calamitous dictatorships, living and deceased, that proclaim socialist or communist commitments. But it’s just as easy to point to Europe, where democratic socialist parties and their descendants have been mainstream players in democratic politics for a century or longer.

The health-care, welfare, and tax systems built by those parties have created societies with far greater equality, higher social mobility, and better health outcomes (at lower cost) than we enjoy here. These systems aren’t perfect, but to a significant degree they’re more democratic than our own.

But we don’t have to look abroad (or to Vermont) for a rich social democratic history.

Milwaukee Mayor Daniel Hoan — one of several socialists to govern the city — served for 24 years, and built the country’s first public busing and housing programs. And ruby-red North Dakota is, even now, the only state in the country with a state-owned bank, thanks to a socialist-led government in the early 20th Century. Today, dozens of elected socialists hold office at the state or municipal levels.

While plenty of socialists embraced democracy, plenty of capitalists turned to dictatorship.

In the name of fighting socialism during the Cold War, the U.S. trained and supported members of right-wing death squads in El Salvador, genocidal army units in Guatemala, and a Chilean military regime that disappeared or tortured tens of thousands of people while enacting “pro-market reforms.”

Only last year, the U.S. government was cheering a military coup against an elected socialist government in Bolivia. And in 2018, The Wall Street Journal praised far-right Brazilian leader Jair Bolsonaro, an apologist for the country’s old military regime, for his deregulation of business.

Even here at home, our capitalist “freedoms” have co-existed peacefully with racial apartheid, the world’s largest prison system, and the mass internment of immigrants and their children.

Sanders has been clear his socialist tradition comes from the social democratic systems common in countries like Denmark, with their provisions for universal health care and free college.

Should Matthews next wonder aloud if candidates who oppose Medicare for All or free college also support death squads, genocide, mass incarceration, or internment camps? If that sounds unfair, then so should the lazy fear mongering we get about “socialism.”

The sobering truth is that all political systems are capable of either great violence or social uplift. That’s why we need resilient social movements, whatever system we use — and why we’re poorly served by propaganda from any corner..

Peter Certo is the editorial manager of the Institute for Policy Studies and editor of OtherWords.org.

Green Mountain gorgeous

"Top of the World" (pastel), by Ann Coleman, in the Ann Coleman Gallery, West Dover, Vt., part of Dover, in southern Vermont, and best know for Mount Snow, the big ski area that was among the first to install snow-making equipment and that has always had a large percentage of “snow bunnies,’’ who tend to lounge at the base lodge rather than ski.

An edited version of the Wikipedia entry on Dover:

“West Dover was settled in 1796, when the area was part of Wardsboro, and was incorporated into Dover when that town was chartered, in 1810. The village grew economically in the 19th Century due to the construction of mills along the river. The first mill, a sawmill, was built in 1796, and was expanded to process wool through the first half of the 19th Century. The mill complex was destroyed by fire in 1901, bringing an end to that source of economic activity. Only traces of the mill complex survive today, but the village has a fine assortment of Federal and Greek Revival buildings that give it its character. In the 20th Century the village benefitted from the state's promotion of out-of-staters’ purchase of farms for vacation and weekend homes, and the growth of the nearby ski areas.’’

'At a loss' on a winter's night

— Photo of frost patterns by Schnobby

All out of doors looked darkly in at him

Through the thin frost, almost in separate stars,

That gathers on the pane in empty rooms.

What kept his eyes from giving back the gaze

Was the lamp tilted near them in his hand.

What kept him from remembering what it was

That brought him to that creaking room was age.

He stood with barrels round him—at a loss.

And having scared the cellar under him

In clomping there, he scared it once again

In clomping off;—and scared the outer night,

Which has its sounds, familiar, like the roar

Of trees and crack of branches, common things,

But nothing so like beating on a box.

A light he was to no one but himself

Where now he sat, concerned with he knew what,

A quiet light, and then not even that.

He consigned to the moon, such as she was,

So late-arising, to the broken moon

As better than the sun in any case

For such a charge, his snow upon the roof,

His icicles along the wall to keep;

And slept. The log that shifted with a jolt

Once in the stove, disturbed him and he shifted,

And eased his heavy breathing, but still slept.

One aged man—one man—can’t keep a house,

A farm, a countryside, or if he can,

It’s thus he does it of a winter night.

“An Old Man’s Winter Night,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963), New England’s and probably America’s most famous poet. He lived in rural New Hampshire and Vermont for most of his life.

John O. Harney: Are N.E. colleges ready for the next recession?

Maine Maritime Academy, in Castine, Maine. Its graduates incur high debt levels but have very low default rates.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Times are already complex for higher education. In Massachusetts, 18 higher education institutions (HEIs) have closed or merged in the past five years. In Vermont, College of St. Joseph, Green Mountain College and Southern Vermont College all held their final graduation ceremonies in the spring. What would happen if a recession were to add to this uncertainty?

With that question in mind, NEBHE in mid-October convened a small group* of higher education leaders and economists to talk about “The Future of Higher Education and the Economy: Lessons Learned from the Last Recession.”

To be sure, some of the problems that have forced college closures are national, but New England (along with the rest of the Northeast and the Upper Midwest) faces specific challenges: most importantly, a daunting demography that spells trouble for college enrollments. By 2032, the number of new high school graduates in New England is projected to decline by 22,000 to a total 140,273, according to the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education.

The NEBHE confab aimed to better understand the key challenges and consequences HEIs faced as a result of the so-called “Great Recession” and what can be learned from them. Among guiding questions:

What is the likely course of the economy over the next 18 to 24 months?

How prepared are institutions for the next recession?

What lessons did higher education learn from the Great Recession?

What conversations should HEIs—presidents, senior leaders, board leaders—be having now?

How fragile are higher ed institutions in New England and beyond?

What economic or other indicators should we be watching at this point in the economic cycle?

What’s the impact of reduced or stagnant state and federal government support?

How did the last recession impact families—and what does it mean for their ability to pay ever-increasing tuition and fees?

When another recession hits, are there adequate social safety nets to cushion the blow?

Which responses to changing demographics, customer preferences and new technology could help institutions avert closure … and even thrive?

The current state and future course of the economy

NEBHE President and CEO Michael K. Thomas opened the discussion asking for panelists’ perceptions of the state of the economy.

The U.S. has been enjoying the longest economic expansion in history. But looking worldwide, China’s economy is slowing, global manufacturing is suffering, and trading nations like Germany and Singapore are close to recession.

Nigel Gault, chief economist in the Boston office of EY-Parthenon, noted that the current expansion has been long (more than 10 years) but slow, not reaching 3% GDP growth in any year. Moreover, higher education enrollments have trended down while student loan debt has exploded. Tuition prices keep going up, raising increasing questions about whether the investment in higher education is worth it. And the demography will get even worse after 2025.

In addition, the international enrollment that kept some HEIs above water is under increased pressure. For international students, “it’s a combination of sensing they’re not wanted and facing more hurdles to get the necessary visa to come,” said Gault.

The overall result: fewer traditional-age college applicants.

“Back in the last expansion, enrollment was still growing 1 to 2%, which is not great, but this time, the expansion has been much slower overall, and enrollment growth is only half a percent to 1%,” said Thomas College President Laurie Lachance.

In her previous roles as the Maine state economist and as corporate economist at Central Maine Power Co., Lachance heard from businesses that bad economic policy is better than frequently changing policy. She wondered if the current whiplash of national policies could tip us into recession.

Gault shared the thought: “Bad policy and volatile policy is a toxic combination. Often the best thing for the economy is policy paralysis because people know the rules are going to stay as they are now and they can plan on that basis.”

What kind of recession?

Recessions can result from global market downturns or be sparked by outside geopolitical events such as the Gulf War in the early 1990s or the subprime mortgage crisis that began in 2007 and led to the 2008 Great Recession.

None of the panelists thought a 2008-magnitude recession would come soon. But Gault suggested the No. 1 risk is the intensification of trade wars between the U.S. and China or the U.S. and Europe. Gault added that China can no longer play the role of savior of the global economy as it did after the Great Recession.

Participants agreed that different kinds of HEIs would be hurt differently by different kinds of recessions. Not only would a recession caused by global downturn be very different from one caused by local or even institution-specific financial factors. At the family level, a recession centered around the financial sector would directly hit a different group of New Englanders than one centered on manufacturing recession.

The panelists imagined multiple scenarios. Some elite HEIs with significant endowments will be hurt for a short time with a market downturn, but they’ll be OK. Some state universities will be too big to fail. Some independent HEI leaders wonder if state governments will consider consolidating low-performing public campuses? If some public HEIs adopt free tuition models, their programs will be hard to resist for students whose parents lose their jobs in a recession. But a downturn would slow public investment in such programs.

If the past is a guide, any recession will bring some enrollment spurt, especially among older students because job options will be less plentiful, Gault observed. But unlike the tailwind during the Great Recession, the demographic headwind this time around, will probably result in a smaller enrollment spike. A modest recession that takes unemployment up to 6% could bring a less than 3% increase in annual enrollment, Gault said.

Even the recovery from the Great Recession varied by HEI based on the regions from which they drew students and whether their students were in programs that are cyclical or counter-cyclical, said University of Saint Joseph President Rhona Free. USJ’s latest focus has been nursing, teaching and social work, which were not especially hurt in 2008. The experience may have been different at liberal arts institutions that primarily offer disciplines, which in careerist times and places get reactions ranging from disparagement for having weak immediate career prospects to praise for being the key to critical thinking, noted Free, who was provost at Eastern Connecticut State University before joining USJ.

Endowment pressures

On average, 12% of operating budgets at HEIs are covered by endowments, though the figure at some wealthy institutions exceeds 50%, according to Timothy T. Yates, Jr., president and CEO of Commonfund Asset Management Company. He pointed out that most investment committees think of endowments by size, but the more important metric is how dependent institutions’ operating budgets are on endowment returns. He told of a private HEI where the share of operating budget covered by endowment went from 18% in 2008 to 15% in 2009. “That’s a huge hole in their operating budget and it took six years to recover.”

Moreover, most investment committees have not been happy with their recent return rates, Yates said. He explained that a market downturn on an endowment causes a drop in funding. HEIs generally draw about 5% from their endowments to support themselves. Yates said about 32% of HEIs have taken special-purpose appropriations from their endowments this year, up from 26% in 2017 and 18% in 2009. Some of these special appropriations have gone to marketing campaigns to drive enrollment; others have been aimed at addressing a deficit, Yates said.

“If people are drawing from their endowments with a one-time, one-year promise-we-won’t-do-it-again appropriation, I’m not sure that’s the way we should be operating. It’s potentially a Hail Mary activity.” said Susan Whealler Johnston, president and CEO of the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO).

Lachance saw all the high-finance handwringing as “first-world” problems. Her Thomas College, with just 800 undergraduates and a $13 million endowment, was on the brink of bankruptcy three decades ago. Now, the college, in the same Maine town, Waterville, as the richer Colby College (which has 2,000 undergraduates and an endowment of more than $800 million), makes tough business decisions to invest in only things that could lead to higher enrollment. Thomas draws just a few percentage points of its endowment annually for its operating budget.

Among new business models, Thomas College has added three-year degrees for high-performing high school students, and key employability programs such as a “golf guarantee” to make sure students, many the first in their families to attend college, graduate networking-ready and more familiar with practical realities of business leadership.

The demographic factor

In the 1970s and early ‘80s, when endowment values dropped sharply, high inflation exacerbated the problem, Yates said. But what higher ed had at that time was a big demographic tailwind with baby boomers starting to come into colleges. Baby boomers now represent about 25% of the population but nearly half of charitable giving.

Also in the ‘70s, higher ed saw the front end of more structured fundraising and the consolidation benefits of single-sex institutions merging. Plus, since there hadn’t yet been large tuition increases, there was room to fill classes with students who were willing to pay more. “In higher education, history has been kind to the continuation of bad business practices, for example, thinking you could just go on and on raising tuition,” Lachance said. But our expert panelists agreed that such slack was no longer in the system.

All in all, a lot of New England higher education’s fortunes can be tied to an aging population. Too few babies are being born to sustain our overbuilt higher education infrastructure. Adults, though underserved, are seen as possible saviors. Professors are aging too, and the older ones are less likely to buy into cost-saving technology and open-education resources that some HEIs such as Thomas College consider a key to success. College presidents, whose average tenure is less than seven years, and chief business officers are also heading toward a retirement cliff.

Johnston reflected on the challenges of HEI governance and added that a lot of board members are in their seventies and will be retiring soon. “Are they the big givers that institutions want to hold onto, or do we need new bring in younger, different thinkers?” Or is the best approach to encourage both, since senior trustees can help newer board members with the institutional context for board decision-making?

Young blood with a new perspective may also bring more honesty to boards. Roger Goodman of the Yuba Group and previously Moody’s (where he wrote for (NEJHE during the last recession) was surprised when a poll at a recent conference for higher education trustees showed nearly 65% believed their HEIs were on a solid financial footing. Such findings suggest a certain level of naivete or denial about the realities facing HEIs.

Then, there are questions about the whole higher education governance model. Board members’ connections to the world outside higher ed surely bring value. But does someone who’s made millions in private equity know the complexities of dealing with a shared governance model and the challenges of higher ed finances? And what about those trustees of public HEIs, some named to boards partly based on connections to governors and other appointing authorities?

Student loans and defaults

One of higher education’s biggest challenges is captured by a staggering number: $1.6 trillion. That’s the current total amount of student loan debt. And unlike other forms of consumer credit, student loan debt is only rising.

Phil Oliff noted that a fifth of federal loan borrowers are in default. There has been much discussion about how student loan debt itself may delay markers of adulthood such as buying a car or home, starting a family or starting a business. Default is an even bigger deal. Wages can be garnished. In some places, professional certifications can be stripped. And credit scores can be hit.

Notably and counterintuitively, the higher defaults are among students with low balances, often because they left college without completing a degree that would provide the earnings to repay their loans.

In Maine, not just community colleges but also lower-tiered university campuses, have higher default rates. Higher default rates seem to be more highly correlated with low graduation rates than they are with larger loan balances. For example, Maine Maritime graduates incur high debt levels but very low default rates, said Lachance.

Much was made of defaults among students at for-profit colleges. But enrollment at for-profits has plummeted since spiking around the time of the last recession.

Public investment in higher education

State funding of higher education has come back somewhat and state fiscal reserves have been built up since the Great Recession, said Oliff. But public higher ed gets disproportionately hit in recessions—as it is seen as a “balance wheel” for legislators struggling to write budgets during downturns.

In the last recession, Oliff added, the federal government created a specific pot of money for states to prop up budgets, plus policy decisions to increase the maximum Pell Grant award, veterans benefits and tax expenditures, such as credits for tuition and college savings incentives. The impact of the last recession, albeit significant, was softened by federal policy interventions. But there’s no guarantee that D.C. will act in the same way in the next recession.

The student debt issue also feeds into and grows out of the changing perceptions of the value of higher education. Increasing critiques of higher ed could affect the cyclical dynamic that has sent more students back to college during recessions. When a recession occurs, will some people question if investing in some or more higher education is a good strategy? Further, shorter-term credentials, rather than degrees, may be key in a changing economy, Gault said. Indeed, NEBHE and others increasingly focus on how “high-value” credentials can more efficiently prepare students for in-demand jobs than can full degree programs.

As an immigrant, USJ’s Rhona Free said she always saw “part of the American Dream is that your 18-year-old goes off to live on a campus and grows in many ways for four years, but the reality is that is largely a middle-class, upper-income, white American Dream. We have to innovate in getting all families to believe that this is achievable for their children and there’s a good return on investment. It will be less debt than if they bought a new car.”

Mergers and alliances

Johnston warned that presidents and boards should be talking about what alliances and mergers might mean to their institutions. But many do not want to talk about it, until they’re hard-pressed. Some of that is reflected in the sentiment noted by Goodman in which two-thirds of board members saw their HEIs as being on solid ground.

In addition, the process of mergers can put a lot of pressure on surviving HEIs. An institution facing the threat of closure might decide to get by for another year with an unsustainable discount, say 75%, to get the incremental student it wants. That can put a lot of pressure on other HEIs that are competing in the market. Johnston pointed out that one HEI in Virginia, determined to grow its enrollment, decided to go deeper into its waiting lists, which affected enrollments at competitors across the state, many of whom did not meet their revenue goals as a result.

“The business model isn’t working for us, and that requires innovation,” said Johnston. And it is explained poorly to the public and students with confounding concepts such as “tuition discounts” and “net prices vs. sticker prices.”

Students and families

When the discussion turned to the condition of social safety nets, Lachance lamented: “The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer. When I was growing up, there were so many mills around us where a high school grad could do just fine. They’d get on a union wage scale and they had a great standard of living to send their own kids to college. Now it seems like the difference is based on your educational attainment. And if you don’t attend college and you don’t persist and graduate, you’ll never earn the return on that investment and you’ll be in debt.”

A recession will surely exacerbate the difference between those who have and those who have not, concluded Johnston. The question is not just which institutions will be most affected, but which students, for example, those with food insecurity. As President Free noted, HEIs’ food pantries and in-demand mental health services are now key social safety nets upon which many students already depend.

Moreover, “Kids who were watching their families go through the last recession may bring a separate set of anxieties with them if there’s another recession,” said Johnston. “They may dial back what they think they can do even if the circumstances don’t require it.”

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

* The panelists …

Rhona C. Free became the ninth president of the West Hartford, Conn.-based University of Saint Joseph in July 2015. During her time at USJ, she has championed the creation of the Women’s Leadership Center and guided the deliberations that led to the university’s decision to become fully coeducational in fall 2018. She joined USJ from Eastern Connecticut State University, where she served as vice president for academic affairs from 2007 to 2013 and provost from 2013 to 2015. She taught Economics at Eastern for 25 years before becoming an administrator.

Roger Goodman is a partner in the Boston office of The Yuba Group LLC, which provides independent financial advice and consulting to higher education institutions on debt and credit-related matters. Prior to joining the Yuba Group, he served as the team leader for the Higher Education and Not-for-Profit Team at Moody’s Investors Service, leading a team of 11 analysts responsible for credit analysis and credit ratings.

Nigel Gault is EY-Parthenon’s chief economist based in the Boston office. He was with Parthenon for a year before its combination with EY in August 2014. He advises clients on issues relating to their strategies, market growth and pricing. Gault was most recently chief U.S. economist at IHS Global Insight, where he was a seven-time winner of the Marketwatch Forecaster of the Month accolade for key economic indicators. He has also served as chief European economist in London for Standard & Poor’s/Data Resources and for Decision Economics.

Susan Whealler Johnston is president and CEO of the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), a position she has held since Aug. 1, 2018. Prior to joining NACUBO, she was at the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges (AGB), where she served as executive vice president and chief operating officer, responsible for the day-to-day operations of the organization as well as strategic planning. Prior to joining AGB, she was professor of English and dean of academic development at Rockford University.

Laurie Lachance is Thomas College’s fifth president and the first female and alumna to lead the college in its 125-year history. From 2004 to 2012, she served as president and CEO of the Maine Development Foundation. Prior to MDF, she served three governors as the Maine state economist. Before joining state government, she served as the corporate economist at Central Maine Power Company.

Phillip Oliff is senior manager at The Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington, D.C., where he leads Pew’s work exploring the fiscal and policy relationships between the federal and state governments on a variety of topics, including how federal budget and tax changes could affect states, the role that federal and state finances play in higher education and surface transportation. He previously was a policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, where he wrote reports on topics including education finance, state tax policy, states’ post-recession fiscal conditions and the impact of emergency federal aid on state budgets.

Timothy T. Yates, Jr. is president and CEO of Commonfund Asset Management and responsible for managing all aspects of Commonfund’s Outsourced Chief Investment Office (OCIO) business, which focuses exclusively on nonprofit institutions. Before joining Commonfund, he was an instructor of Spanish and Italian at Fordham Preparatory School in the Bronx, N.Y.

Gray, or colorless?

“Thanksgiving,’’ by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe

If months were marked by colors, November in New England would be colored gray.

— Madeleine M. Kunin, diplomat, author and politician. She was the 77th governor of Vermont, from 1985 until 1991.

Vermont finding it tough to meet green goals

Here, in Vernon, on the Connecticut River, is the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant, which was shut down in 2014. Vermont had for many years the highest rate of nuclear-generated electric power in America — at almost 75 percent. Vermont is one of only two states with no coal-fired power plants.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “DIgital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A Jan. 28 story in The Boston Globe, “In Vermont, a progressive haven, emissions spike forces officials to consider drastic action,’’ contained some irony: The Green Mountain State, long associated with environmentalism and progressive politics in general, has failed by a long shot to meet its stated aims of slashing carbon emissions. Indeed, these emissions have risen 16 percent from 1990!

Part of the challenge is the high percentage of ownership of aging, energy-inefficient pickup trucks, which, as in many mostly rural states, are sort of the official state vehicle. Further, cheap gasoline during the past few years has encouraged even more driving in a state whose residents are accustomed to traveling long distances every day.

Another problem in the heavily forested state is the heavy use of wood as fuel for heating. You can see smog in some river valleys from the many wood stores and furnaces. (I remember back when I lived in the Upper Connecticut Valley in the late ‘60s that wood (a carbon-based fuel!) was promoted as the wonderfully natural way to help wean ourselves off that nasty Arab oil.)

And while transportation is the largest single source of emissions – 43 percent – the closing of Vermont’s only nuclear-power, in 2014, made the state more dependent on fossil-fuel power plants. Global warming may make promoting nuclear power easier.

The administration of Gov. Phil Scott, a moderate Republican whom I’ve met and like, has come up with a detailed program to cut admissions, which includes, The Globe reports:

“{P}rograms to help improve energy efficiency in homes, financial incentives for electric vehicles, and protections for the state’s forests, which are in decline for the first time in a century.’’

In any event, it will take a long time for The Green Mountain State to get as

“green’’ as the rest of the country might think it is.

To read The Globe’s story, please hit this link.

'Mysterious core of life'

Town meeting in Huntington, Vt.

“Vermont tradition is based on the idea that group life should leave each person as free as possible to arrange his own life. This freedom is the only climate in which (we feel) a human being may create his own happiness. ... Character itself lies deep and secret below the surface, unknown and unknowable by others. It is the mysterious core of life, which every man or woman has to cope with alone, to live with, to conquer and put in order, or to be defeated by.’’

— Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1879-1958), American writer and education reformer

'That's what we do' in Vermont

“For much of America, the all-American values depicted in Norman Rockwell's classic illustrations are idealistic. For those of us from Vermont, they're realistic. That's what we do’’

— U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)

In Newfane, Vt.

Feds say no to Mass. attempts to negotiate for cheaper drugs

The Massachusetts State House, with its famous gold dome.

By MARTHA BEBINGER

States serve as “laboratories of democracy,” as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously said. And states are also labs for health policy, launching all kinds of experiments lately to temper spending on pharmaceuticals.

No wonder. Drugs are among the fastest-rising health-care costs for many consumers and are a key reason that health-care spending dominates many state budgets — crowding out roads, schools and other priorities.

Consider Vermont, California and Oregon, states that are beginning to implement drug-price transparency laws. In Nevada, the push for transparency includes the markup charged by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). In May, Louisiana joined a growing list of states banning “gag rules” that prevent pharmacists from discussing drug prices with patients.

State-based experiments may carry even greater weight for Medicaid, the federal-state partnership that covers roughly 75 million low-income or disabled Americans.

Ohio is targeting the fees charged to its Medicaid program by PBMs. New York has established a Medicaid spending drug cap. In late June, Oklahoma’s Medicaid program was approved by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to begin “value-based purchasing” for some newer, more expensive drugs: When drugs don’t work, the state would pay less for them.

But around the same time, CMS denied a proposal from Massachusetts that was seen as the boldest attempt yet to control Medicaid drug spending.

Massachusetts planned to exclude expensive drugs that weren’t proven to work better than existing alternatives. The state said Medicaid drug spending had doubled in five years. Massachusetts wanted to negotiate prices for about 1 percent of the highest-priced drugs and stop covering some of them. CMS rejected the proposal without much explanation, beyond saying Massachusetts couldn’t do what it wanted and continue to receive the deep discounts drugmakers are required by law to give state Medicaid programs.

The Medicaid discounts were established in 1990 law based on a grand bargain that drugmakers say guaranteed coverage of all medicines approved by the Food and Drug Administration in exchange for favorable prices.

The New England Journal of Medicine dives into the CMS decision regarding Massachusetts and its implications for other state Medicaid programs in a commentary by Rachel Sachs, an associate professor of law at Washington University, in St. Louis, and co-author Nicholas Bagley. They dispute the Trump administration’s claim that Massachusetts’ plan would violate the grand bargain.

We talked with Sachs about Massachusetts’s proposal and the implications for the rest of the country. Her answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Why do you think states, such as Massachusetts, should be allowed to exclude some drugs, a move the pharmaceutical industry has said would break the deal reached back in 1990?

In our view, there’s a way to frame it where the bargain has been broken and Massachusetts is simply trying to restore the balance. The problem is that the meaning of FDA approval has changed significantly over the last almost 30 years. Now we have a lot more drugs that are being approved more quickly, on the basis of less evidence — smaller trials, using surrogate endpoints — where the state has real questions about whether these drugs work at all, not only whether they are good value for the money.

Q: You suggest that Massachusetts could make a reasonable case if it chose to challenge the CMS denial. How?

CMS did not explain why it didn’t grant Massachusetts’ waiver. It needs to give reasons for denying something that Massachusetts, in our view, has the legal ability to do. CMS’ failure to give reasons in this case resembles their failure to give reasons in a number of other cases that have recently led courts to strike down actions by the Trump administration for failure to explain the actions that they were taking.

(Note: A spokeswoman for Health and Human Services in Massachusetts says the state is not going to challenge the CMS decision.)

Q: While CMS blocked the Massachusetts experiment, it has approved the value-based purchasing plan in Oklahoma, and New York has capped its Medicaid drug spending. Aren’t those signs of flexibility for states?

In some ways, yes, and in other ways, no. New York passed a cap on state Medicaid pharmaceutical spending. But once the state hits that cap, it doesn’t mean the state will stop paying for prescription drugs. It just means the state is empowered to negotiate with some of these companies and seek additional discounts. They didn’t need CMS approval for this. New York doesn’t have the ability to say “If you don’t take this deal, we’re not going to cover this product.”

Oklahoma is pursuing outcomes-based pricing, which is of interest. It’s the first state to express interest in doing so. However, there are a lot of observers who are skeptical that outcomes agreements of this kind will materially lower prices or if they just provide companies cover to charge higher prices in the first instance.

Q: So what options do you see ahead for states given what happened in Massachusetts with the Medicaid waiver?

Unfortunately, states are quite limited in what they’re able to do on their own, in terms of controlling prescription drug costs — both costs that are borne by the state in its capacity as a public employer and its capacity as an insurer for the Medicaid population. and then more generally for the many citizens who are on private insurance plans throughout the state.

This is a real problem, this concern of federal pre-emption where states’ ability to go beyond federal law is often limited. So what we’re seeing now is more states like Massachusetts and Vermont taking action that forces the federal government to do something or say something. States are increasingly putting pressure on the federal government because they know that their ability to act on this problem of drug pricing is limited.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.