Gilda A. Barabino: Higher education must do more 'to bend the arc' by increasing diversity

A view of Olin College of Engineering, in Needham, Mass. The dormitories are to the right; “The Oval ‘‘is straight ahead. Olin, whose president is the author of the essay below, is a very unusual undergraduate-only engineering school. Though it’s new — it was founded in 1997 — it’s already prestigious and has developed partnerships with such noted nearby institutions as Babson College, Wellesley College and Brandeis University.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

America is undergoing a reckoning as the suffering and setbacks caused by years of systemic racism is coming into full view. This heightened awareness around racism, sparked by death and injustice, must result in the development of real pathways to eliminate systemic racism, or it will be a lost opportunity for our generation to do our part in—to paraphrase Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—bending the long “arc of the moral universe’’ toward justice. Higher education, like all other institutions in our society, must do its share of bending the arc.

My academic path, and that of other Black people and people of color, is riddled with instances of both egregious and subtle forms of racism. When this happens to Black people in our academies, it threatens the well being of all of us by limiting access to the creation of knowledge and innovation that flourishes when a diversity of minds is present. Drawing from my own experience as a scientist, professor and administrator, I believe there are a number of ways in which colleges and universities can advance and improve the lives of all our students—and especially students of color.

First, we must do more to increase diversity in our student body. This not only creates more opportunity for our students from underrepresented communities, but also increases the variation of perspective and lived experience that we know produces a richer learning and social experience for all students. We can achieve this by stepping up our recruiting efforts that target high schools serving Black, Latinx and Native American populations. To further support building diversity, we can look at new approaches to sustaining our financial aid practices in light of the economic pressures of the pandemic, restructuring current programs to yield more aid and pushing our alumni and corporate partners to increase scholarship and grant opportunities. Supporting organizations like the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering, for example, broadens opportunities.

Creative and strategic team-building is another way to ensure success and positive experiences among our diverse students. At Olin College of Engineering, where I am president, part of how we transformed engineering instruction was by developing student-centered programs that rely on teams working on projects. While these teams are created to be self-sufficient in sharing and experiencing learning, our instructors intervene to ensure that inherent biases do not unknowingly arise in things like the assigning of tasks or how information is shared with professors.

As we work on the diversity in our student population, it is equally important that we make every effort to increase diversity in our faculty and staff as well. Black faculty account for a mere 6 percent of all full-time faculty in the academy. I know from personal experience that no matter how excellent a department’s faculty and support staff may be, it is hard for students of color to imagine a future in which they can succeed without the distinct modeling and mentorship made possible from professors and counselors who look like them and who have had many of the same life experiences. (As a new faculty member at Northeastern University in 1989, lacking mentors and role models of my own, but recognizing their importance, I served as a role model and mentor in the NEBHE Role Model Network for Underrepresented Students and as a consultant to NEBHE’s equity and diversity programs.)

One of our most important roles in the education and lives of our students is preparing them for, and connecting them to, the world at large and their path to success. Very often, students of color do not have the connections that lead to opportunities like internships and summer jobs in their field of interest. We can build bridges to successful careers by ensuring that our career centers are operating at the highest level possible and are able to establish connections with companies that are eager to help diverse students.

This process can be helped by making every effort to connect diverse students with the career center and promoting its value to them. As colleges and universities operating in New England, we are fortunate to be in a vibrant regional economy made up of established companies, innovative startups and leading health-care and research institutions. By developing stronger partnerships between our schools, regional businesses (many of which provide internships and other work opportunities) and the business community leadership, we can leverage these connections into career-focused opportunities on behalf of all of our students, which would be especially helpful in creating life-changing opportunities for our diverse students.

Even though higher-education institutions are facing significant operational and financial challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic, we nonetheless must take action today to ensure that we are moving beyond words and demonstrations and taking real action to ensure that equity, diversity and opportunity exists and benefits young people of color—not only within our quads, residence halls and classrooms—but in the larger world as well.

Gilda A. Barabino is president of Olin College of Engineering and professor of biomedical and chemical engineering there.

Liz Szabo: Some COVID-19 patients hit by friendly fire

The Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University, in Providence’s old “Jewelry District.’’ Most people still just call it the Brown Medical School.

Dr. Megan Ranney, of Brown University, has learned a lot about COVID-19 since she began treating patients with the disease in the emergency department in February.

But there’s one question that she still can’t answer: What makes some patients so much sicker than others?

Advancing age and underlying medical problems explain only part of the phenomenon, said Ranney, who has seen patients of similar age, background and health status follow wildly different trajectories.

“Why does one 40-year-old get really sick and another one not even need to be admitted?” asked Ranney, an associate professor of emergency medicine at Brown.

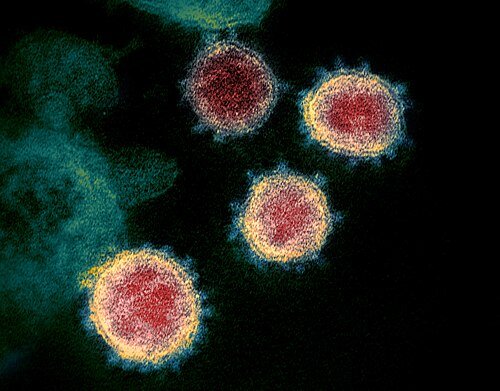

In some cases, provocative new research shows, some people — men in particular — succumb because their immune systems are hit by friendly fire. Researchers hope the finding will help them develop targeted therapies for these patients.

In an international study in Science, 10 percent of nearly 1,000 COVID patients who developed life-threatening pneumonia had antibodies that disable key immune system proteins called interferons. These antibodies — known as autoantibodies because they attack the body itself — were not found at all in 663 people with mild or asymptomatic COVID infections. Only four of 1,227 healthy individuals had the autoantibodies. The study, published on Oct. 23, was led by the COVID Human Genetic Effort, which includes 200 research centers in 40 countries.

“This is one of the most important things we’ve learned about the immune system since the start of the pandemic,” said Dr. Eric Topol, executive vice president for research at Scripps Research, in San Diego, who was not involved in the new study. “This is a breakthrough finding.”

In a second Science study by the same team, authors found that an additional 3.5 percent of critically ill patients had mutations in genes that control the interferons involved in fighting viruses. Given that the body has 500 to 600 of these genes, it’s possible researchers will find more mutations, said Qian Zhang, lead author of the second study.

Interferons serve as the body’s first line of defense against infection, sounding the alarm and activating an army of virus-fighting genes, said virologist Angela Rasmussen, an associate research scientist at the Center of Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

“Interferons are like a fire alarm and a sprinkler system all in one,” said Rasmussen, who wasn’t involved in the new studies.

Lab studies show interferons are suppressed in some people with COVID-19, perhaps by the virus itself.

Interferons are particularly important for protecting the body against new viruses, such as the coronavirus, which the body has never encountered, said Zhang, a researcher at Rockefeller University’s St. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases.

When infected with the novel coronavirus, “your body should have alarms ringing everywhere,” said Zhang. “If you don’t get the alarm out, you could have viruses everywhere in large numbers.”

Significantly, patients didn’t make autoantibodies in response to the virus. Instead, they appeared to have had them before the pandemic even began, said Paul Bastard, the antibody study’s lead author, also a researcher at Rockefeller University.

For reasons that researchers don’t understand, the autoantibodies never caused a problem until patients were infected with COVID-19, Bastard said. Somehow, the novel coronavirus, or the immune response it triggered, appears to have set them in motion.

“Before COVID, their condition was silent,” Bastard said. “Most of them hadn’t gotten sick before.”

Bastard said he now wonders whether autoantibodies against interferon also increase the risk from other viruses, such as influenza. Among patients in his study, “some of them had gotten flu in the past, and we’re looking to see if the autoantibodies could have had an effect on flu.”

Scientists have long known that viruses and the immune system compete in a sort of arms race, with viruses evolving ways to evade the immune system and even suppress its response, said Sabra Klein, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Antibodies are usually the heroes of the immune system, defending the body against viruses and other threats. But sometimes, in a phenomenon known as autoimmune disease, the immune system appears confused and creates autoantibodies. This occurs in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, when antibodies attack the joints, and Type 1 diabetes, in which the immune system attacks insulin-producing cells in the pancreas.

Although doctors don’t know the exact causes of autoimmune disease, they’ve observed that the conditions often occur after a viral infection. Autoimmune diseases are more common as people age.

In yet another unexpected finding, 94 percent of patients in the study with these autoantibodies were men. About 12.5 percent of men with life-threatening COVID pneumonia had autoantibodies against interferon, compared with 2.6 percent of women.

That was unexpected, given that autoimmune disease is far more common in women, Klein said.

“I’ve been studying sex differences in viral infections for 22 years, and I don’t think anybody who studies autoantibodies thought this would be a risk factor for COVID-19,” Klein said.

The study might help explain why men are more likely than women to become critically ill with COVID-19 and die, Klein said.

“You see significantly more men dying in their 30s, not just in their 80s,” she said.

Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology at the Yale School of Medicine, noted that several genes involved in the immune system’s response to viruses are on the X chromosome.

Women have two copies of this chromosome — along with two copies of each gene. That gives women a backup in case one copy of a gene becomes defective, Iwasaki said.

Men, however, have only one copy of the X chromosome. So if there is a defect or harmful gene on the X chromosome, they have no other copy of that gene to correct the problem, Iwasaki said.

Bastard noted that one woman in the study who developed autoantibodies has a rare genetic condition in which she has only one X chromosome.

Scientists have struggled to explain why men have a higher risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19. When the disease first appeared in China, experts speculated that men suffered more from the virus because they are much more likely to smoke than Chinese women.

Researchers quickly noticed that men in Spain were also more likely to die of COVID-19, however, even though men and women there smoke at about the same rate, Klein said.

Experts have hypothesized that men might be put at higher risk by being less likely to wear masks in public than women and more likely to delay seeking medical care, Klein said.

But behavioral differences between men and women provide only part of the answer. Scientists say it’s possible that the hormone estrogen may somehow protect women, while testosterone may put men at greater risk. Interestingly, recent studies have found that obesity poses a much greater risk to men with COVID-19 than to women, Klein said.

Yet women have their own form of suffering from COVID-19.

Studies show women are four times more likely to experience long-term COVID symptoms, lasting weeks or months, including fatigue, weakness and a kind of mental confusion known as “brain fog,” Klein noted.

As women, “maybe we survive it and are less likely to die, but then we have all these long-term complications,” she said.

After reading the studies, Klein said, she would like to learn whether patients who become severely ill from other viruses, such as influenza, also harbor genes or antibodies that disable interferon.

“There’s no evidence for this in flu,” Klein said. “But we haven’t looked. Through COVID-19, we may have uncovered a very novel mechanism of disease, which we could find is present in a number of diseases.”

To be sure, scientists say that the new study solves only part of the mystery of why patient outcomes can vary so greatly.

Researchers say it’s possible that some patients are protected by past exposure to other coronaviruses. Patients who get very sick also may have inhaled higher doses of the virus, such as from repeated exposure to infected co-workers.

Although doctors have looked for links between disease outcomes and blood type, studies have produced conflicting results.

Screening patients for autoantibodies against interferons could help predict which patients are more likely to become very sick, said Bastard, who is also affiliated with the Necker Hospital for Sick Children, in Paris. Testing takes about two days. Hospitals in Paris can now screen patients on request from a doctor, he said.

Although only 10 percent of patients with life-threatening COVID-19 have autoantibodies, “I think we should give the test to everyone who is admitted,” Bastard said. Otherwise, “we wouldn’t know who is at risk for a severe form of the disease.”

Bastard said he hopes his findings will lead to new therapies that save lives. He notes that the body manufactures many types of interferons. Giving these patients a different type of interferon — one not disabled by their genes or autoantibodies — might help them fight off the virus.

In fact, a pilot study of 98 patients published Thursday in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine journal found benefits from an inhaled form of interferon. In the industry-funded British study, hospitalized COVID patients randomly assigned to receive interferon beta-1a were more than twice as likely as others to recover enough to resume their regular activities.

Researchers need to confirm these findings in a much larger study, said Dr. Nathan Peiffer-Smadja, a researcher at Imperial College London who was not involved in the study but wrote an accompanying editorial. Future studies should test patients’ blood for genetic mutations and autoantibodies against interferon, to see if they respond differently than others.

Peiffer-Smadja notes that inhaled interferon may work better than an injected form of the drug because it’s delivered directly to the lungs. While injected versions of interferon have been used for years to treat other diseases, the inhaled version is still experimental and not commercially available.

And doctors should be cautious about interferon for now, because a study led by the World Health Organization found no benefit to an injected form of the drug in COVID patients, Peiffer-Smadja said. In fact, there was a trend toward higher mortality rates in patients given interferon, although this finding could have been due to chance. Giving interferon later in the course of disease could encourage a destructive immune overreaction called a cytokine storm, in which the immune system does more damage than the virus.

Around the world, scientists have launched more than 100 clinical trials of interferons, according to clinicaltrials.gov, a database of research studies from the National Institutes of Health.

Until larger studies are completed, doctors say, Bastard’s findings are unlikely to change how they treat COVID-19.

Dr. Lewis Kaplan, president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, said he treats patients according to their symptoms, not their risk factors.

“If you are a little sick, you get treated with a little bit of care,” Kaplan said. “You are really sick, you get a lot of care. But if a COVID patient comes in with hypertension, diabetes and obesity, we don’t say, ‘They have risk factors. Let’s put them in the ICU.’’

Liz Szabo is a reporter for Kaiser Health News

Liz Szabo: lszabo@kff.org, @LizSzabo

Mark Kreidler: How Harvard and Stanford B-schools have battled COVID-19

Harvard Business School is to the left, on the south side of the Charles River. Across the river, in Cambridge, is the university’s main campus.

At the Stanford University Graduate School of Business, near San Francisco, the stories got weird almost immediately upon students’ return for the fall semester. Some said they were being followed around campus by people wearing green vests telling them where they could and could not be, go, stop, chat or conduct even a socially distanced gathering. Others said they were threatened with the loss of their campus housing if they didn’t follow the rules.

“They were breaking up picnics. They were breaking up yoga groups,” said one graduate student, who asked not to be identified so as to avoid social media blowback. “Sometimes they’d ask you whether you actually lived in the dorm you were about to go into.”

Across the country, in Boston, students at the Harvard Business School gathered for the new semester after being gently advised by the school’s top administrators, via email, that they were part of “a delicate experiment.” The students were given the ground rules for the term, then received updates every few days about how things were going. And that, basically, was that.

In the time of COVID-19, it’s fair to say that no two institutions have come to quite the same conclusions about how to proceed safely. But as Harvard’s and Stanford’s elite MBA-granting programs have proved, those paths can diverge radically, even as they may eventually lead toward the same place.

For months, college and university administrators nationwide have huddled with their own medical experts and with local and county health authorities, trying to determine how best to operate in the midst of the novel coronavirus. Could classes be offered in person? Would students be allowed to live on campus — and, if so, how many? Could they hang out together?

“The complexity of the task and the enormity of the task really can’t be overstated,” said Dr. Sarah Van Orman, head of student health services at the University of Southern California and a past president of the American College Health Association. “Our first concern is making sure our campuses are safe and that we can maintain the health of our students, and each institution goes through that analysis to determine what it can deliver.”

With a campus spread over more than 8,000 acres on the San Francisco Peninsula, Stanford might have seemed like a great candidate to host large numbers of students in the fall. But after sounding hopeful tones earlier in the summer, university officials reversed course as the pandemic worsened, discussing several possibilities before finally deciding to limit on-campus residential status to graduate students and certain undergrads with special circumstances.

The Graduate School of Business sits in the middle of that vast and now mostly deserted campus, so the thought was that Stanford’s MBA hopefuls would have all the physical distance they needed to stay safe. Almost from the students’ arrival in late August, though, Stanford’s approach was wracked by missteps, policy reversals and general confusion over what the COVID rules were and how they were to be applied.

Stanford’s business grad students were asked to sign a campus compact that specified strict safety measures for residents. Students at Harvard Business School signed a similar agreement. In both cases, state and local regulations weighed heavily, especially in limiting the size of gatherings. But Harvard’s compact emerged fully formed and relied largely on the trustworthiness of its students. The process at Stanford was unexpectedly torturous, with serial adjustments and enforcers who sometimes went above and beyond the stated restrictions.

Graduate students there, mobilized by their frustration over not being consulted when the policy was conceived, urged colleagues not to sign the compact even though they wouldn’t be allowed to enroll in classes, receive pay for teaching or live in campus housing until they did. Among their objections: Stanford’s original policy had no clear appeals process, and it did not guarantee amnesty from COVID violation punishments to those who reported a sexual assault “at a party/gathering of multiple individuals” if the gathering broke COVID protocols.

Under heavy pressure, university administrators ultimately altered course, solicited input from the grad student population and produced a revised compact addressing the students’ concerns in early September, including the amnesty they sought for reporting sexual assault. But the Stanford business students were already unsettled by the manners of enforcement, including the specter of vest-wearing staffers roaming campus.

According to the Stanford Daily, nine graduate students were approached in late August by armed campus police officers who said they’d received a call about the group’s outdoor picnic and who — according to the students — threatened eviction from campus housing as an ultimate penalty for flouting safety rules. “For international students, [losing] housing is really threatening,” one of the students told the newspaper.

The people in the vests were Event Services staff working as “Safety Ambassadors,” Stanford spokesperson E.J. Miranda wrote in an email. The staffers were not on campus to enforce the compact, but rather were “emphasizing educational and restorative interventions,” he said. Still, when the university announced the division of its campus into five zones in September, it told students in a health alert email that the program “will be enforced by civilian Stanford representatives” — the safety ambassadors.

The Harvard Business School’s approach was certainly different in style. In July, an email from top administrators reaffirmed the school’s commitment to students living on campus and taking business classes in person in a hybrid learning model. As for COVID protocols, the officials adopted “a parental tone,” as the graduate business education site Poets & Quants put it. “All eyes are on us,” the administrators wrote in an August email.

But the guts of the school’s instructions were similar to those at Stanford. Both Harvard and Stanford severely restricted who could be on campus at any given time, limiting access to students, staff members and preapproved visitors. Both required that anyone living on campus report their health daily through an online portal, checking for any symptoms that could be caused by COVID-19. Both required face coverings when outside on campus — even, a Harvard missive said, in situations “when physical distancing from others can be maintained.”

So far, both Harvard and Stanford have posted low positive test rates overall, and the business schools are part of those reporting totals, with no significant outbreaks reported. Despite their distinct delivery methods, the schools ultimately relied on science to guide their COVID-related decisions.

“I feel like we’ve been treated as adults who know how to stay safe,” said a Harvard second-year MBA candidate who requested anonymity. “It’s worked — at least here.”

But as the experiences at the two campuses show, policies are being written and enforced on the fly, in the midst of a pandemic that has brought challenge after challenge. While the gentler approach at Harvard Business School largely worked, it did so within a larger framework of the health regulations put forth by local and county officials. As skyrocketing COVID-19 rates across the nation suggest, merely writing recommendations does little to slow the spread of disease.

Universities have struggled to strike a balance between the desire to deliver a meaningful college experience and the discipline needed to keep the campus caseload low in hopes of further reopening in 2021. In Stanford’s case, that struggle led to overreach and grad-student blowback that Harvard was able to avoid.

The fall term has seen colleges across the country cycling through a series of fits and stops. Some schools welcomed students for in-person classes but quickly reverted to distance learning only. And large campuses, with little ability to maintain the kind of control of a grad school, have been hit tremendously hard. Major outbreaks have been recorded at Clemson, Arizona State, Wisconsin, Penn State, Texas Tech — locations all over the map that opened their doors with more students and less stringent guidelines.

In May, as campuses mostly shut down to consider their future plans, USC’s Van Orman expressed hope that universities’ past experiences with international students and global outbreaks, such as SARS, would put them in a position to better plan for COVID-19. “In many ways, we’re one of the best-prepared sectors for this test,” she said.

Six months later, colleges are still being tested.

Mark Kreidler is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Llewellyn King: Horrific holiday season; Pfizer vaccine developed in Germany, not U.S.

Nurse dealing with COVID-19 patient.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It is coming to us as a diabolical enemy: malign, merciless and murderous.

The second wave of COVID-19 will be killing us today, tomorrow, and on and on until a vaccine is administered not just to the willing recipients, but to the whole population. That could take years.

We haven’t been through anything like this since the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. Not only is COVID-19 set to kill many more of us than it already has, but it also is likely to have huge collateral damage.

Think restaurants: 60 percent of the individually owned ones are set to fail. Think real estate: The damage is so far too great and expanding too fast to calculate -- all those office buildings sitting empty, all those shopping centers being vacated. The real estate crisis is beginning, just beginning, to be felt by the banks. Think education: A year has been lost in education.

Our cultural institutions, from small sports teams to all the performing arts, are on death watch. How long can you hold a theater production company together? How do you save those very fragile temples of high culture, including ballet, opera and symphony music? What of the buildings that house them?

Now looming are the malevolent threats to Thanksgiving and Christmas. These festivals, so cherished, so looked forward to, such milestones of every year and our lives, are set to kill many of us, gathered in love and joy.

Families will assemble in happiness, but that diabolical guest COVID-19 will be taking its monstrous, lethal place at our tables -- at the very events that in normal times bind us together. Death will share our feasts.

These are words of alarm, and they are meant to be.

Nearly a quarter of a million of us have died, choked to death by the virus. Projected deaths are 110,000 more by New Year. Yet our leaders have spurned the modest defenses available to us: face masks and isolation. There is little usefulness in assigning blame, but there is blame, and it points upward.

But there is localized blame, too. Blame for what I see on the streets, where young people stroll without protecting themselves and others from the deadly virus. Blame for what I see at the shops, where customers gain entry without the modest consideration of wearing a face mask for a few minutes.

There is blame for pastors who have insisted on holding services that have spread COVID-19 to their parishioners. And there is blame for those who have rallied or taken to street demonstrations. The virus has no political affiliation, but politics has befriended it in awful ways.

The mother lode of blame must be put upon that increasingly bizarre figure Donald J. Trump, president of the United States, elected to lead and defend us.

Trump couldn’t have vanquished the pandemic, but he could have limited its spread. He could have guided the people, set an example, told the truth, unleashed consideration not invective.

He could have done his job.

When we needed information, we got lies; when we needed guidance, we were encouraged to take risks by myth and bad example. A high number of his own staff has been felled.

On Jan. 20, 2021, President-elect Joe Biden will step into this gigantic crisis. Even if the first doses of a vaccine are being administered, the crisis will still be in full flame, taking lives, destroying businesses, subtracting jobs, and changing the trajectory of the future.

There will be good, but it will take time to arrive. It will be in innovation in everything, from more medical research to start-ups and lessons learned about survival in crisis.

It will impact immigration. Only the willfully unobservant won’t note that a preponderance of the health authorities featured nightly on television weren’t born here, and their talent is a bonus for the country.

It should be noted that Pfizer’s landmark COVID-19 vaccine wasn’t developed in that U.S. pharmaceutical behemoth, but by a husband-and-wife team in a small company in Germany. Both are children of Turkish immigrants to that country.

In all countries, immigrants have had the adventurous spirit that is the soul of creativity. Let them in.

The "Wee Annie" statue, in Gourock, Scotland, has a face mask during the pandemic.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Chris Powell: Serious cases, not tests, should measure pandemic

— Photo by Raimond Spekking

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Everybody is tired of the COVID-19 epidemic, and no one is more entitled to be tired of it than Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont. It has devastated the finances of state government, commandeered its management, crippled education at all levels, and worsened many social problems.

While people admire the governor's calm and conscientious manner, they may lose patience as his plan for returning Connecticut to normal starts reversing. Of course the epidemic is not the governor's fault and he deserves sympathy, but his reversal amid fears that the epidemic is surging again should prompt reconsideration of the measures being used to set policy.

Are the governor's premises correct?

The primary measure of the epidemic, in Connecticut and other states, is the "positivity rate," the percentage of daily virus tests reported as positive. One day about week ago the rate exceeded 6 percent, setting off hysteria among news organizations, before falling the next day to a more typical 3 percent. But these figures don't mean that 6 or 3 percent of the state's population is infected. These figures mean only that infection has reached those levels among people who chose to be tested in the previous several days.

Infection levels among the entire population of the state may be lower or higher than the daily "positivity rate." Paradoxically, a higher rate might be much better. That's because most people who contract the virus suffer no symptoms or only mild symptoms and do not require special treatment even as they gain antibodies conferring some immunity. Indeed, if the governor's data is analyzed in another way, so as to calculate what might be called the serious case rate, the positivity rate loses relevance, the virus looks less dangerous, and the epidemic looks less serious.

For the eight days from Oct. 26 through Nov. 2, the governor reported 7,806 new virus cases, 50 new "virus-associated" deaths, and 107 new hospitalizations. If deaths and new hospitalizations are totaled and categorized as serious cases, the serious case rate for those eight days was only 2 percent of all new cases, substantially below the positivity rate for those days -- 3.4 percent -- and way below the one-day positivity rate that caused alarm.

The mortality rate for the week was only six-tenths of 1 percent of all new cases -- and that is measured only against known new cases. If the mortality rate could be calculated from all new cases, including the week's unreported cases -- asymptomatic people -- it likely would be much smaller.

After all, it seems that 7,649 of the 7,806 people who figured in the virus reports for those eight days -- 98 percent of them -- were simply sent home to recover, perhaps with some over-the-counter or prescription medicine.

At the governor's Oct. 26 briefing Dr. John Murphy, chief executive of the Nuvance Health hospital network, tamped down the fright. Murphy noted that treatments for the virus have gotten much more effective since the epidemic began in March -- that while there is as yet no cure, there are medicines that slow the virus and aid recovery, and that as younger people with fewer underlying health problems have become infected, the virus fatality rate and the average length of hospitalization have fallen by half.

The great concern at the start of the epidemic -- hospital capacity -- remains valid, but it deserves reconsideration too. Back then the Connecticut National Guard set up field hospitals with nearly 1,700 beds, including more than 600 at the Connecticut Convention Center in Hartford. They weren't used before they were taken down, and with fewer than 400 virus patients hospitalized in the state last week, presumably the state, if pressed, could handle at least a quadrupling of patients.

None of this argues for carelessness, like that of college students partying in close quarters without masks, nor for reopening bars, where the virus may spread most easily. But it does argue for continuing the gradual reopening that was underway before a bad positivity rate scared everybody.

Of course, news organizations delight in scaring people with the positivity rate, but they are enabled in this by the governor's stressing it instead of the serious case rate.

If the infirm elderly and the chronically ill are better protected, fear may subside and relatively normal life may be possible again.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Ross E. O'Hara: Online-learning advice for college students

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The majority of college students were largely disappointed by remote learning this past spring, with many reporting a strong preference for in-person instruction. Bearing in mind the low expectations that many students carried into online courses this fall, what advice can we give to help them succeed in this final month? As colleges across New England and the country continue to announce spring plans that include online courses, what can we share to prepare students for success in 2021?

While the internet is saturated with “hacks” for online learning, I want to connect you with the best experts I know: Students.

Since March, the Persistence Plus mobile nudging support platform has asked more than 25,000 students from both two- and four-year institutions about their experiences with remote learning. Specifically, we gathered their advice about how to excel in this format, and I saw four key themes emerge. I have also paired their insights with science-based exercises that can be shared with students to bolster their motivation and improve their performance in online courses.

1. Set a schedule. The most frequently offered advice was the need to set a regular schedule—especially in asynchronous courses—and stick to it. Several students mentioned examining the syllabus for major assignments and noting due dates in advance, working ahead on those assignments to the extent possible and regularly checking email and the course website. Here’s some of what they said:

“Make a schedule for classes, study time, completion of assignments, breaks, etc., and build enough discipline to stick to the schedule.”

“Make a schedule for time to study. Prioritize due dates on assignments and exams. It is not as difficult as you may think. Discipline and focus is key.”

“Work as far ahead as possible, get assignments done as soon as you get them so you don’t have to worry about it, and set a scheduled time each day to work on school.”

“Write everything down and log into your classes and email to check for new reminders and announcements every day.”

One way that students can go beyond just setting a schedule is with “if-then” plans. We all naturally underestimate how long it takes to complete projects (known as the planning fallacy). To counteract this optimism, students can make very specific plans for when and where they will work on assignments (for example, “I will read Chapter 1 at the dining room table after my daughter goes to sleep on Wednesday night.”) The more specific they are, the more likely they are to follow through.

Yet the best-laid schemes of mice and men oft go awry. Students should also develop contingency plans for common obstacles (such as “If my daughter doesn’t fall asleep by 9 p.m., then I will read Chapter 1 before she wakes up the next morning.”) No one can foresee the future, but anticipating the most likely problems and pre-designing solutions will help students stay on track. You can facilitate students’ if-then plans by prompting them to complete the exercise via an email, a poll within your institution’s learning management system, or even providing space in the syllabus to craft if-then plans for each big assignment.

2. Create a study space. Students noted how important it is to have a quiet, peaceful (but not too relaxing!) area for schoolwork. The goal of such a space is to create focus without inducing grogginess. They suggested:

“Find a place where you can be composed and stay focused with your priorities.”

“If you can, set aside someplace that is specially for school work so that you can focus when doing work and then relax when you go to bed (if you only have space in your bedroom then just make sure not to do work on your bed, work only on your desk).”

“Find a place in your home to go that is designated to your studies.”

“Don’t attend virtual classes in bed! Try working at a table or desk for effective productivity. Working in your bed allows you to be too comfortable and can cause you to fall asleep or lose focus.”

Given the COVID-19 pandemic, this area is most likely within students’ homes. But as we all know, our homes are often crowded with partners, children, parents and roommates. One advantage of a dedicated space is that it sends a signal that this person is studying and shouldn’t be interrupted. Moreover, a regular study space takes advantage of state-dependent memory. When you learn something, cues from the environment become associated with it: the feel of your chair, the smell of the room, the taste of your coffee, even your mood at that moment. If students put themselves into those same circumstances when they need to recall that information (i.e. for the exam), they’ll be more likely to remember.

3. Ask for help. We heard over and over that students must reach out for help, especially from their professors, if they get stuck. If you’re a professor but you might be difficult to reach (you’re dealing with plenty of crises too!) build a system that makes it easy for students to connect with other faculty, former students, campus tutors, tech support and each other. Students advised:

“Don’t be afraid to email professors and/or classmates/peers for understanding of the coursework and/or additional assistance.”

“Professors make it very easy, they work with you and they provide all the resources you need to be successful. Don’t forget to ask questions.”

“Make group messages with your peers so you can keep each other on track, and ask each other questions.”

“Don’t be afraid to reach out to classmates and ask for help. Everyone is going through it together and supporting each other through it is what makes it work.”

Asking for help makes some students feel nervous or embarrassed. One way to circumvent those feelings is to use simple role reversal. Instead of asking someone else for advice, students can imagine that one of their classmates came to them with the same issue. Students can then consider what they would advise their peer to do, or whom they would point them to for help. This role-playing can make students less anxious by approaching their own problem from a neutral perspective, make them feel more empowered, and help them generate potential solutions that they may not otherwise see.

4. Be accountable. Finally, students noted that success in online courses requires a lot of self-discipline and accountability. The physical and emotional distance between students and their professors can make it all the easier to skip assignments or not participate in class. They noted:

“It’s all about being on top of your work and holding yourself accountable. If you can handle online college classes, you can handle college.”

“Don’t put off projects and homework just because the deadline isn’t for a little while, you will forget and have to rush to finish it so just do it or start it (and do a good amount of the work) as soon as it is assigned.”

“Study just like you would if you were taking the class in a classroom. No matter where you are learning from, the same level of effort and focus is expected.”

It is challenging to maintain focus on learning online, while also working (or looking for work), raising children and dealing with life’s other responsibilities. One practice that may help students concentrate is to engage in 5-10 minutes of expressive writing before working on school. Ask students to privately jot down everything in their life that is worrying or stressing them out, and write specifically about how each one makes them feel. Rather than suppressing or ignoring their emotions, releasing them on paper lessens their impact and will allow students to better focus on learning or performing. They can even crumple up that piece of paper and toss it in a recycling bin, symbolically discarding those intrusive thoughts so they can get down to business.

Despite our general comfort level with technology, most of us are still unacquainted with experiencing most of our lives online, and things won’t be that much better as we continue remote learning into 2021. While students study algebra, or 20th Century European history or computer coding, remember that they’re still adapting to a whole new way of learning, and that’s not easy. So please pass along advice from our college experts to your students and their instructors so they may be better prepared for any eventual roadblock.

Ross E. O’Hara is director of behavioral science and education at Persistence Plus LLC, which is based in Boston.

Share This Page

Share this...

Filed under College Readiness, Commentary, Demography, Economy, Financing, Journal Type, Schools, Students, Technology, The Journal, Topic, Trends.

Latest wrap-up of region's COVID-19 response

The front entrance of MGH, in Boston

Here is the most recent wrap-up the region’s COVID-19 developments from The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

“Harvard Medical School Researchers Publish COVID-19 Rehabilitation Study – Researchers at Harvard Medical School have published a study detailing rehabilitation plans crafted for patients in Boston and New York-based hospitals. The team has treated over 100 patients and points to continued studies to address persistent COVID-19 symptoms. Read more here.

“Mass General Releases Guidance on Weaning Patients Off Ventilators – Clinicians at Massachusetts General Hospital have released an article with an accompanying video to demonstrate effective ways to wean patients with serious COVID-19 infections off of ventilators. The materials offer step-by-step instructions and were published in The New England Journal of Medicine. Read more here.

“Health Leads Releases Joint Statement on Ensuring Racial Equity in the Creation and Distribution of a COVID-19 Vaccine – Health Leads has released a statement, in conjunction with a number of other organizations and individuals, emphasizing the importance of supporting underserved communities in recovering from COVID-19. The statement includes strategies for ensuring equity in vaccine distribution. Read more here.’’

Julie Appleby/Victoria Knight: COVID death counts spawn conspiracy theories

In the waning days of the campaign, PresidentTrump complained repeatedly about how the United States tracks the number of people who have died from COVID-19, claiming, “This country and its reporting systems are just not doing it right.”

He went on to blame those reporting systems for inflating the number of deaths, pointing a finger at medical professionals, who he said benefit financially.

All that feeds into the swirling political doubts that surround the pandemic, and raises questions about how deaths are reported and tallied.

We asked experts to explain how it’s done and to discuss whether the current figure — an estimated 231,000 deaths since the pandemic began — is in the ballpark.

Dismissing Conspiracy Theories, Profit Motives

Trump’s recent assertions have fueled conspiracy theories on Facebook and elsewhere that doctors and hospitals are fudging numbers to get paid more. They’ve also triggered anger from the medical community.

“The suggestion that doctors — in the midst of a public health crisis — are overcounting COVID-19 patients or lying to line their pockets is a malicious, outrageous, and completely misguided charge,” Dr. Susan R. Bailey, American Medical Association president, said in a press release.

Hospitals are paid for COVID treatment the same as for any other care, though generally, the more serious the problem, the more hospitals are paid. So, treating a ventilator patient — with COVID-19 or any other illness — would mean higher payment to a hospital than treating one who didn’t require a ventilator, reflecting the extra cost.

There is one financial difference. Medicare, the government health program for the elderly and disabled, pays 20% on top of its ordinary reimbursement for COVID patients — a result of the CARES Act, the federal stimulus bill that passed in the spring.

That additional payment applies only to Medicare patients.

Experts say there is simply no evidence that physicians or hospitals are labeling patients as having COVID-19 simply to collect that additional payment. Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association, wrote an opinion piece in September addressing what he called the “myths” surrounding the add-on payments. While many hospitals are struggling financially, he wrote, they are not inflating the number of cases — and there are serious disincentives to do so.

“The COVID-19 code for Medicare claims is reserved for confirmed cases,” he wrote, and using it inappropriately can result in criminal penalties or a hospital being kicked out of the Medicare program.

Public health officials and others also pushed back.

Said Jeff Engel, senior adviser for COVID-19 at the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists: “Public health is charged with the duty to collect accurate, timely and complete data. We’re not incentivized to overcount or undercount for any political or funding reason.”

And what about medical examiners? Are they part of a concerted effort to overcount deaths to reap financial rewards?

“Medical examiners and coroners in the U.S. are not organized enough to have a conspiracy. There are 2,300 jurisdictions,” said Dr. Sally Aiken, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners. “That’s not happening.”

Still, there’s an ongoing debate about which mortalities should be considered COVID deaths.

Behind the Numbers

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as nongovernmental organizations like the COVID Tracking Project and Johns Hopkins University, compile daily data on COVID deaths. Their statistics rely on state-generated data, which begins at the local level.

States have leeway to decide how to gather and report data. Many rely on death certificates, which list the cause of death, along with contributing factors. They are considered very accurate but can take one to two weeks to be finalized because of the processes involved in filling them out, reviewing and filing them. These reports generally lag behind testing and hospitalization data.

The other way deaths get reported is through what’s known as the case classification method, which reports deaths of people with previously identified cases of COVID, whether listed as confirmed or probable. Confirmed COVID deaths are affirmed by a positive test result. Probable COVID deaths are classified by using medical record evidence, suspected exposure or serology tests for COVID antibodies. The case classification method is faster than using death certificates and makes the data available in a more real-time fashion. Epidemiologists say this information can be helpful in gaining an understanding in the midst of an outbreak of how many people are dying and where.

Some experts point out that, while both methods have their virtues, each shows a different mortality count at a different time, so the best practice is to gather both sets of information.

The federal government, though, has offered conflicting guidance. The National Center for Health Statistics, an arm of the CDC, recommends primarily using death certificate data to count COVID deaths. But in April, the CDC asked jurisdictions to start tracking mortality based on probable and confirmed case classifications. Most states now gather data only one of the two ways, though a couple use both.

This patchwork approach does lead to conflicting data on total deaths.

Why Is the Count So Hard?

For the most part, public health researchers and medical examiners agree that COVID deaths are likely being undercounted.

“It’s very hard in a situation moving as rapidly as this one, and at such a large scale, to be able to count accurately,” said Sabrina McCormick, an associate professor in environmental and occupational health at George Washington University.

For one thing, the processes for certifying deaths vary widely, as does who fills out the death certificates. While physicians certify most death certificates, coroners, medical examiners and other local law enforcement officials can also do so.

Aiken, the medical examiner of Spokane County, Washington, said any time someone in her area dies at home and may have had COVID symptoms, the deceased person will automatically be tested for the disease.

But that doesn’t happen everywhere, she added, which means some who die at home could be omitted from the count.

It’s also unknown how accurate post-mortem COVID testing is, because there haven’t yet been any research studies on the practice — which could lead to missed cases.

Another wrinkle: Doctors in hospitals might not always be trained in the best practices for filling out death certificates, Aiken said.

“These folks are dealing with ERs and ICUs that are crowded. Death certificates are not their priority,” she said.

Emergency room doctors acknowledged the challenges, noting they don’t always have the resources that coroners and medical examiners do to perform autopsies.

“Much of the time, we don’t have an answer as to the final reason that a person died, so we are often stuck with the old cardiopulmonary arrest, which coroners and certifiers hate,” said Dr. Ryan Stanton, a Lexington, Kentucky, ER doctor and board member of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

That gets to how complex it is to determine what, exactly, caused a death — and what some say is a confusion between who died “with” COVID-19 (but may have had other underlying conditions that caused their death) and who died directly “of” COVID-19.

John Fudenberg, the former coroner for Clark County, Nevada, which surrounds Las Vegas, said including some of those who died with COVID-19 could result in an overcount.

“As a general rule, if someone dies with COVID, it’s going to be on the death certificate, but it doesn’t mean they died from COVID,” said Fudenberg, now executive director of the International Association of Coroners and Medical Examiners. For example, “if somebody has end-stage pancreatic cancer and COVID, did they die with COVID or from COVID?”

That question has proven controversial, and Trump has claimed that counting those who died “with COVID” has led to an inflation of the numbers. But most public health experts agree that if COVID-19 caused someone to die earlier than they normally would have, then it certainly contributed to their death. Additionally, those who certify death certificates say they list only contributing factors that are certain.

“Doctors don’t put things on death certificates that have nothing to do with the death,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

COVID-19 can directly lead to death in someone with cancer or heart problems, even if those conditions were also serious or even expected to be fatal, he said.

And the claim that some states are counting people who die in car accidents, but also test positive for COVID-19, as COVID deaths is just plain unfounded, experts said.

“I can’t imagine a scenario where a medical examiner would test someone for COVID who died in a motor vehicle accident or a homicide,” said Engel, at the epidemiologists council. “I think that’s been greatly exaggerated on the internet.”

Excess Deaths

An additional approach to determining the pandemic’s scope has emerged, and many experts increasingly point to this measure as a useful indicator.

It relies on a concept known as “excess deaths,” which involves comparing the total number of deaths from all causes in a given period with the same period in previous years.

A CDC study estimated that almost 300,000 more people died in the U.S. this year from late January through Oct. 3 than in previous years. Some of those excess deaths were no doubt COVID cases, while others may have been people who avoided medical care because of the pandemic and then died from another cause.

These excess deaths are “the best evidence” that undercounting is ongoing, said Dr. Jeremy Faust, an ER doctor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “The timing of the excess deaths exactly parallels the COVID deaths, so when COVID deaths spike, all causes of deaths spike. They are hugging each other like parallel train tracks on a graph.”

Faust believes the majority of the excess deaths should be attributed in some way to COVID-19.

Even so, it’s unclear if we’ll ever get an accurate count.

Aiken said it is possible but could take years. “I think eventually, when this is said and done, we’ll have a pretty good count,” she said.

McCormick, of George Washington University, isn’t as sure, mostly because the number has become a flashpoint.

“It will always be a controversy, especially because it’s going to be so politically charged,” she said. “I don’t think we’ll come to a final number.”

Victoria Knight and Julie Appleby are Kaiser Health News reporters.

Victoria Knight: vknight@kff.org, @victoriaregisk

Julie Appleby: jappleby@kff.org, @Julie_Appleby

COVID-19 wrapup

From The New England Council’s (newenglandcouncil.com) latest wrap up of COVID-19 news:

“Eli Lilly Find Drug to Improve Clinical Outcomes – Eli Lilly and Company has found that baricitinib, used alongside remdesivir, reduces recovery time and improves clinical outcomes for patients infected with COVID-19 more so than patients treated only with remdesivir. Eli Lilly originally developed baricitinib – marketed at Olumiant – as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, but has been studying the drug as a COVID-19 treatment as part of a trial sponsored by the National Institute of Allery and Infectious Diseaseas (NIAID). The most signifiant impact was observed in patients placed on supplemental oxygen. Read more here.

“Harvard Street Neighborhood Health Center Utilizes Mobile COVID-19 Testing Unit – Early in the pandemic, Harvard Street Neighborhood Health Center launched a mobile COVID-19 testing unit, which has since tested thousands of patients at Dudley Square, Prince Grand Hall Lodge, Children’s Services of Roxbury and other locations. Read more here.

“Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Grants Additional $400,00 to COVID-19 Fund – Blue Cross Blue Shield has donated $400,000 to go towards supporting communities of color most affected by the pandemic, as well as Massachusetts regional funds community health centers, nonprofits, and teacher organizations. Read more here.’’

Largest self-reported ancestry groups in New England. Americans of Irish descent form a plurality in most of Massachusetts, while Americans of English descent form a plurality in much of central Vermont and New Hampshire as well as nearly all of Maine.

Not wearing masks, not crowds, is the big peril

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Studies of some transit systems suggest that they’re not dangerous unless people don’t wear masks against COVID-19. Very crowded subway systems in Asia and Europe, where people are bumping up against each other, have not seeded pandemic outbreaks, because unlike in crazy Trumpian America, just about everyone wears a mask. Social distancing per se is overrated, as is that theatrical spraying with disinfectant.

Unfortunately, there’s no nationwide mask mandate for U.S. public transit, unlike in many other countries. It’s been politicized here, mostly because Trump supporters state their affiliation by refusing to wear masks, thus jeopardizing everyone else’s health.

Meanwhile, some states may have to declare harsh new lockdowns because of COVID seeding going on in bars, restaurants, colleges and public events.

The MBTA, by the way, is quite safe. Yes, I’ve used it recently to do business in Boston. It’s safer than driving into that city! But given how few people are using it, and the fact that conductors now sometimes don’t collect fares, the agency’s finances are in dire straits.

Llewellyn King: Can NYC recover its swagger after COVID-19?

In the energy of midtown Manhattan

NEW YORK

Alistair Cooke, the great British journalist who wrote his weekly “Letter from America” – a paean to the United States -- for 58 years, reserved some of his most lavish praise for Manhattan. When Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader, visited America and wanted to see Disney World, Cooke told him he’d never see anything as extraordinary as the Manhattan skyline.

I was reminded of this long-ago admonishment recently, when I had the opportunity to see Manhattan from the water, cruising around the island on a friend’s yacht, looking at that skyline, those fingers of buildings, thrusting toward heaven in a forest of architectural and engineering creativity that has no equal on earth. Dubai may aspire but it doesn’t compete.

Manhattan is awe on steroids.

I’ve savored and, at times, detested it for decades. I suffered its awfulness at the bottom when many newspapers closed and I, an immigrant with no resources, found work as a busboy at the Horn & Hardart on 42nd Street – one of the food-service automats which were once a feature of New York City. They were where the hapless could sit unbothered for long hours without buying anything beyond coffee; where they could stay warm and sheltered in the winter.

I’ve also savored Manhattan in good times, staying at the Carlyle Hotel, one of the best hotels in the world, up there with the Ritz in Paris and Brown’s in London.

It was said when I lived there in the 1960s, that New York was a city for the extraordinarily rich and the extremely poor. I found work in Washington and stayed south; New York became a place to visit.

If it was a hard place to be poor in 1965, the extremes of poverty and wealth only increased with time.

More great buildings, enabled by engineering that allowed them to be planted in smaller plots of land, sprouted in Manhattan. Spindle apartment buildings and sprawling waterfront office developments were built with money that flowed in from hedge funds, tech companies, Russian oligarchs, Chinese billionaires, and Middle Eastern oil-garchs.

On Sept. 11, 2001, the Big Apple felt its vulnerability to a hostile, premeditated attack. Now it is facing its greatest crisis, one that will wound it mortally if not fatally: COVID-19.

New York City has an uncertain future. People are moving out, selling their expensive co-ops at a loss, and buying in less-crowded places on Long Island, in the Hudson Valley, Connecticut, and even farther afield.

As I looked in wonder at the city of striving people, epitomized by its buildings that themselves seem to strive to go ever higher, I wondered whether New York is over, destined to a slow death; its apartments in the clouds likely to be abandoned, and its trove of office space to sit empty as a new generation grows into the idea that working from home — home far away — is the norm, the new way to think about work.

The New York Times has looked at the problem and its writers can’t, it seems, bring themselves to answer the question: Is it over?

The city’s impending tragedy will be played out in other cities, but it is in New York that it will be most visible, most painful; the dream most shattered.

Sure, you might say, it was built on greed and now it must pay the price. But it was also built on much else: immigration, diversity, financial acumen, theater, fine art, sweat and toil -- and that most human of emotions: aspiration.

I hope that the new normal will allow cities to recover and New York to swagger forward as it has in the past: difficult to live in and difficult to live without. It’s a miracle of a city, a big shiny apple.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Website: whchronicle.com

In Korea Town, one of New York’s many ethnic neighborhoods

Chen Shih-chung: COVID-19 shows importance of Taiwan being admitted to WHO

WHO emblem

Our friends in the Taiwan representative office in Boston forwarded this to us.

— Robert Whitcomb

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, there have more than 40 million cases and more than one million deaths around the world. The virus has had an enormous impact on global politics, employment, economics, trade and financial systems, and significantly impacted the global efforts to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs).

Thanks to the united efforts of its entire people, Taiwan has responded to the threats posed by this pandemic through four principles: prudent action, rapid response, advance deployment and openness and transparency. Adopting such strategies as the operation of specialized command systems, the implementation of meticulous border-control measures, the production and distribution of adequate supplies of medical resources, the employment of home quarantine and isolation measures and related care services, the application of IT systems, the publishing of transparent and open information, and the execution of precise screening and testing, we have been fortunate enough to contain the virus. As of Oct. 7, Taiwan had had just 523 confirmed cases and seven deaths; meanwhile, life and work have continued much as normal for the majority of its people.

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has reminded the world that infectious diseases know no borders and do not discriminate along political, ethnic, religious or cultural lines. Nations should work together to address the threat of emerging diseases. For this reason, once Taiwan had stabilized its containment of the virus and ensured that people had sufficient access to medical resources, we began to share our experience and exchange information on containing COVID-19 with global public-health professionals and scholars through COVID-19-related forums, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation group’s (APEC) High-Level Meeting on Health and the Economy, the Global Cooperation Training Framework, and other virtual bilateral meetings. As of June 2020, Taiwan had held nearly 80 online conferences, sharing the Taiwan Model with experts from governments, hospitals, universities and think tanks in 32 countries.

Taiwan’s donations of medical equipment and anti-pandemic supplies to countries in need also continue. By June, we had donated 51 million surgical masks, 1.16 million N95 masks, 600,000 isolation gowns, and 35,000 forehead thermometers to more than 80 countries.

To ensure access to vaccines, Taiwan has joined the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility (COVAX) co-led by GAVI — the Vaccine Alliance — and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. And our government is actively assisting domestic manufacturers in hopes of accelerating the development and production of successful vaccines, bringing them to market as quickly as possible and putting an end to this pandemic.

To prepare for a possible next wave of the pandemic as well as the approaching flu season, Taiwan is maintaining its strategies of encouraging citizens to wear face masks and maintain social distancing, and strengthening border quarantine measures, community-based prevention and medical preparedness. Furthermore, we are actively collaborating with domestic and international partners to obtain vaccines and develop optimal treatments and accurate diagnostic tools, jointly safeguarding global public-health security.

The COVID-19 pandemic has proven that Taiwan is an integral part of the global public-health network and that Taiwan Model can help other countries combat the pandemic. To recover better, WHO needs Taiwan. We urge WHO and related parties to acknowledge Taiwan’s longstanding contributions to global public health, disease prevention, and the human right to health, and to firmly support Taiwan’s inclusion in WHO. Taiwan’s comprehensive participation in WHO meetings, mechanisms and activities would allow us to work with the rest of the world in realizing the fundamental human right to health as stipulated in the WHO Constitution and the vision of leaving no one behind enshrined in the UN SDGs.

Chen Shih-chung is minister for health and welfare for Taiwan (Republic of China)

John O. Harney: Pressing on through the pandemic

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

A little of what we’ve been following …

Counting heads. New enrollment figures show higher education reeling under the weight of COVID-19 and a faltering economy on top of pre-existing challenges such as worries that college may not be worth the price. A month into the fall 2020 semester, undergraduate enrollment nationally was down 4 percent from last year, thanks in large part to a 16 percent drop in first-year students attending college this pandemic fall, according to “First Look” data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. In New England, the early data suggest New Hampshire and Vermont were among the handful of U.S. states enrolling more undergraduates than last fall, while Rhode Island reported a nearly 16 percent drop.

At community colleges, freshman enrollment sunk by nearly 23 percent nationally, the clearinghouse reports.

Interestingly, before COVID hit and when so-called “Promise” programs were in full stride, 33 public community college Promise programs across the U.S. showed big enrollment success with their free-college models, according to a study released recently in the Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association. Such programs were “associated with large enrollment increases of first-time, full-time students—with the biggest boost in enrollment among Black, Hispanic and female students,” the study found, adding, “The results come as the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is leading states to tighten higher education budgets, as low-income students are forgoing their postsecondary plans at higher rates this fall than their wealthier peers, and as community colleges are experiencing larger enrollment declines than four-year universities.”

On the other hand, a report from our friends at the Hildreth Institute examines 22 statewide, free-tuition programs established in the past decade, and finds that most do not address the real barriers that prevent many students from getting a higher education credential. The report notes that tuition and fees represent just 24 percent of the cost of attending a community college and 40 percent of the cost of attending a public four-year university. Beyond tuition, students struggle with necessities like textbooks, computers, software, internet access, housing, food and transportation. Moreover, “the lower the income of a student, the less likely they are to benefit from existing tuition-free programs, known as ‘last-dollar’ scholarships, which cover only the portion of tuition and fees that are not covered by existing financial aid,” the Hildreth report notes.

Digital futures. The ECMC Foundation awarded the Business-Higher Education Forum (BHEF) $341,000 to fund the Connecticut Digital Credential Ecosystem Initiative, in partnership with NEBHE. A network of companies, community colleges, government agencies and other stakeholders, led by BHEF, will develop new pathways to digital careers, particularly for individuals unemployed due to COVID-19. BHEF will help community colleges issue industry-validated credentials to support transparent career pathways across Connecticut and the surrounding region. Participating employers will approve the knowledge, skills and abilities for these credentials, thus building recruitment and hiring links for students who complete the credential. The idea owes much to the work and recommendations of NEBHE’s Commission on Higher Education & Employability.

Organizing. I was happy to attend the virtual annual conference of the Hunter College National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions, its 47th annual conference, this time held virtually due to COVID. The topic was “Inequality, Collective Bargaining and Higher Education.” It was a goldmine of perspectives on equity, antiracism and labor rights.

Among bright spots, talk of a possible student loan debt jubilee and increasing moves by campus CEOs to resist pay raises. Bill Fletcher, former president of the advocacy group TransAfrica and senior scholar with the Institute for Policy Studies, recounted the formation of labor organizing in the U.S. from America’s original sins of annihilating Native Americans and enslaving Africans through the birth of trade unionism and social justice efforts like Occupy and the National Education Association’s Red for Ed. We don’t need white allies, he added, but rather white comrades like John Brown on the frontlines.

Touting Joe Biden’s higher-education platform, Tom Harnish, vice president for government relations at the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association and a faculty member at George Washington University, offered basic advice: If you want better higher-education policy, get out and vote and put better people in office.

In a session on the evolution of labor studies, speakers noted that many labor-education programs have been folded into management schools or sometimes taught under the guise of the history of capitalism so as to attract students. We have to warn students that this is not the place if you’re aspiring to an HR position, one said.

Purdue dropping program in Lewiston, Maine. No higher-education models seem immune to COVID-19. Recently, Purdue University Global announced it is dropping its physical presence in Lewiston, Maine, when its lease expires in March. In spring 2017, Purdue University acquired most of the credential-granting side of the then-for-profit Kaplan University, as part of the Indiana-based public research university’s effort to engage the fast-growing adult student market. Kaplan had about 32,000 students taking courses online or at one of more than a dozen physical campus locations, including Lewiston and Augusta, Maine. The Lewiston building had been empty due to COVID. The Augusta building reportedly will continue to house the nursing program. Kaplan University, by the way, converted to nonprofit status as part of the deal.

See you in better times …

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

JoNel Aleccia: Should you try Trump-touted drugs?

“You shouldn’t expect that what you’ve heard about on the news is the right treatment for you.”

— Benjamin Rome, M.D., Harvard Medical School

When Terry Mutter woke up with a headache and sore muscles on a recent Wednesday, the competitive weightlifter chalked it up to a hard workout.

By that evening, though, he had a fever of 101 degrees and was clearly ill. “I felt like I had been hit by a truck,” recalled Mutter, who lives near Seattle.

The next day he was diagnosed with COVID-19. By Saturday, the 58-year-old was enrolled in a clinical trial for the same antibody cocktail that President Trump claimed was responsible for his coronavirus “cure.”

“I had heard a little bit about it because of the news,” said Mutter, who joined the study by drugmaker Regeneron to test whether its combination of two man-made antibodies can neutralize the deadly virus. “I think they probably treated him with everything they had.”

Mutter learned about the study from his sister-in-law, who works at Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, one of dozens of trial sites nationwide. He is among hundreds of thousands of Americans — including the president — who’ve taken a chance on experimental therapies to treat or prevent COVID-19.

But with nearly 8 million people in the U.S. infected with the coronavirus and more than 217,000 deaths attributed to COVID, many patients are unaware of such options or unable to access them. Others remain wary of unproven treatments that can range from drugs to vaccines.

“Honestly, I don’t know whether I would have gotten a call if I hadn’t known somebody who said, ‘Hey, here’s this study,’” said Mutter, a retired executive with Boeing Co.

The Web vsite clinicaltrials.gov, which tracks such research, reports more than 3,600 studies involving COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease. More than 430,000 people have volunteered for such studies through the COVID-19 Prevention Network. Thousands of others have received therapies, like the antiviral drug remdesivir, under federal emergency authorizations.

Faced with a dire COVID diagnosis, how do patients or their families know whether they can — or should — aggressively seek out such treatments? Conversely, how can they decide whether to refuse them if they’re offered?

Such medical decisions are never easy — and they’re even harder during a pandemic, said Annette Totten, an associate professor of medical informatics and clinical epidemiology at Oregon Health & Science University.

“The challenge is the evidence is not good because everything with COVID is new,” said Totten, who specializes in medical decision-making. “I think it’s hard to cut through all the noise.”

Consumers have been understandably whipsawed by conflicting information about potential COVID treatments from political leaders, including Trump, and the scientific community. The antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, touted by the president, received emergency authorization from the federal Food and Drug Administration, only to have the decision revoked several weeks later out of concern it could cause harm.

Convalescent plasma, which uses blood products from people recovered from COVID-19 to treat those who are still ill, was given to more than 100,000 patients in an expanded-access program and made widely available through another emergency authorization — even though scientists remain uncertain of its benefits.