Noises in a summer night

“What rattles in the dark? The blinds at Brewster?

I am a boy then, sleeping by the sea,

Unless that clank and chittering proceed

From a bent fan-blade somewhere in the room….’’

— From “In Limbo,’’ by Richard Wilbur (1921-2017), New England-based poet, literary translator and teacher. He served as U.S. poet laureate. The “Brewster’’ here is the town on the Cape Cod Bay side of the peninsula. It’s best known now as a summer-home center.

Linnell Landing Beach, in Brewster.

Brewster was named for Elder William Brewster, the first religious leader of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Colony. The town grew around Stony Brook, where the first water-powered grist and woolen mill in the country was founded in the late 17th Century — an early sign of New Englanders’ world-famous inventiveness. Rich sea captains built many of the town’s stately homes, some of which are now inns and bed-and-breakfasts. The most notable of these are the Brewster Historical Society’s Captain Elijah Cobb House, on Lower Road, the Crosby Mansion, on Crosby Lane by Crosby Beach, and the Captain Freeman Inn on Breakwater Road.

Stony Brook mill.

‘Muscles must be used’

Helen Keller (left) in 1899 with companion and teacher Anne Sullivan. Photo taken by telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell at his School of Vocal Physiology and Mechanics of Speech, in Boston.

“All the wondrous physical, intellectual and moral endowments, with which man is blessed, will, by inevitable law, become useless, unless he uses and improves them. The muscles must be used, or they become unserviceable. The memory, understanding and judgment must be used, or they become feeble and inactive. If a love for truth and beauty and goodness is not cultivated, the mind loses the strength which comes from truth, the refinement which comes from beauty, and the happiness which comes from goodness.’’

— Anne Sullivan (1866-1936), teacher and lecturer, in her 1886 commencement address at the Perkins School for the Blind. Founded in 1829 and now in Watertown, Mass., it’s the oldest school of its kind in the United States. Ms. Sullivan, who was mostly blind, is most famous as the teacher of Helen Keller (1880-1968), the blind and deaf author, lecturer and political activist who was a household name in America for much of her adult life. The relationship between the two women was memorialized in the play and movie The Miracle Worker.

Too bad that the students can’t see it: The Howe Building Tower at the Perkins School for the Blind's campus, in Watertown, Mass.

Mark Kreidler: How Harvard and Stanford B-schools have battled COVID-19

Harvard Business School is to the left, on the south side of the Charles River. Across the river, in Cambridge, is the university’s main campus.

At the Stanford University Graduate School of Business, near San Francisco, the stories got weird almost immediately upon students’ return for the fall semester. Some said they were being followed around campus by people wearing green vests telling them where they could and could not be, go, stop, chat or conduct even a socially distanced gathering. Others said they were threatened with the loss of their campus housing if they didn’t follow the rules.

“They were breaking up picnics. They were breaking up yoga groups,” said one graduate student, who asked not to be identified so as to avoid social media blowback. “Sometimes they’d ask you whether you actually lived in the dorm you were about to go into.”

Across the country, in Boston, students at the Harvard Business School gathered for the new semester after being gently advised by the school’s top administrators, via email, that they were part of “a delicate experiment.” The students were given the ground rules for the term, then received updates every few days about how things were going. And that, basically, was that.

In the time of COVID-19, it’s fair to say that no two institutions have come to quite the same conclusions about how to proceed safely. But as Harvard’s and Stanford’s elite MBA-granting programs have proved, those paths can diverge radically, even as they may eventually lead toward the same place.

For months, college and university administrators nationwide have huddled with their own medical experts and with local and county health authorities, trying to determine how best to operate in the midst of the novel coronavirus. Could classes be offered in person? Would students be allowed to live on campus — and, if so, how many? Could they hang out together?

“The complexity of the task and the enormity of the task really can’t be overstated,” said Dr. Sarah Van Orman, head of student health services at the University of Southern California and a past president of the American College Health Association. “Our first concern is making sure our campuses are safe and that we can maintain the health of our students, and each institution goes through that analysis to determine what it can deliver.”

With a campus spread over more than 8,000 acres on the San Francisco Peninsula, Stanford might have seemed like a great candidate to host large numbers of students in the fall. But after sounding hopeful tones earlier in the summer, university officials reversed course as the pandemic worsened, discussing several possibilities before finally deciding to limit on-campus residential status to graduate students and certain undergrads with special circumstances.

The Graduate School of Business sits in the middle of that vast and now mostly deserted campus, so the thought was that Stanford’s MBA hopefuls would have all the physical distance they needed to stay safe. Almost from the students’ arrival in late August, though, Stanford’s approach was wracked by missteps, policy reversals and general confusion over what the COVID rules were and how they were to be applied.

Stanford’s business grad students were asked to sign a campus compact that specified strict safety measures for residents. Students at Harvard Business School signed a similar agreement. In both cases, state and local regulations weighed heavily, especially in limiting the size of gatherings. But Harvard’s compact emerged fully formed and relied largely on the trustworthiness of its students. The process at Stanford was unexpectedly torturous, with serial adjustments and enforcers who sometimes went above and beyond the stated restrictions.

Graduate students there, mobilized by their frustration over not being consulted when the policy was conceived, urged colleagues not to sign the compact even though they wouldn’t be allowed to enroll in classes, receive pay for teaching or live in campus housing until they did. Among their objections: Stanford’s original policy had no clear appeals process, and it did not guarantee amnesty from COVID violation punishments to those who reported a sexual assault “at a party/gathering of multiple individuals” if the gathering broke COVID protocols.

Under heavy pressure, university administrators ultimately altered course, solicited input from the grad student population and produced a revised compact addressing the students’ concerns in early September, including the amnesty they sought for reporting sexual assault. But the Stanford business students were already unsettled by the manners of enforcement, including the specter of vest-wearing staffers roaming campus.

According to the Stanford Daily, nine graduate students were approached in late August by armed campus police officers who said they’d received a call about the group’s outdoor picnic and who — according to the students — threatened eviction from campus housing as an ultimate penalty for flouting safety rules. “For international students, [losing] housing is really threatening,” one of the students told the newspaper.

The people in the vests were Event Services staff working as “Safety Ambassadors,” Stanford spokesperson E.J. Miranda wrote in an email. The staffers were not on campus to enforce the compact, but rather were “emphasizing educational and restorative interventions,” he said. Still, when the university announced the division of its campus into five zones in September, it told students in a health alert email that the program “will be enforced by civilian Stanford representatives” — the safety ambassadors.

The Harvard Business School’s approach was certainly different in style. In July, an email from top administrators reaffirmed the school’s commitment to students living on campus and taking business classes in person in a hybrid learning model. As for COVID protocols, the officials adopted “a parental tone,” as the graduate business education site Poets & Quants put it. “All eyes are on us,” the administrators wrote in an August email.

But the guts of the school’s instructions were similar to those at Stanford. Both Harvard and Stanford severely restricted who could be on campus at any given time, limiting access to students, staff members and preapproved visitors. Both required that anyone living on campus report their health daily through an online portal, checking for any symptoms that could be caused by COVID-19. Both required face coverings when outside on campus — even, a Harvard missive said, in situations “when physical distancing from others can be maintained.”

So far, both Harvard and Stanford have posted low positive test rates overall, and the business schools are part of those reporting totals, with no significant outbreaks reported. Despite their distinct delivery methods, the schools ultimately relied on science to guide their COVID-related decisions.

“I feel like we’ve been treated as adults who know how to stay safe,” said a Harvard second-year MBA candidate who requested anonymity. “It’s worked — at least here.”

But as the experiences at the two campuses show, policies are being written and enforced on the fly, in the midst of a pandemic that has brought challenge after challenge. While the gentler approach at Harvard Business School largely worked, it did so within a larger framework of the health regulations put forth by local and county officials. As skyrocketing COVID-19 rates across the nation suggest, merely writing recommendations does little to slow the spread of disease.

Universities have struggled to strike a balance between the desire to deliver a meaningful college experience and the discipline needed to keep the campus caseload low in hopes of further reopening in 2021. In Stanford’s case, that struggle led to overreach and grad-student blowback that Harvard was able to avoid.

The fall term has seen colleges across the country cycling through a series of fits and stops. Some schools welcomed students for in-person classes but quickly reverted to distance learning only. And large campuses, with little ability to maintain the kind of control of a grad school, have been hit tremendously hard. Major outbreaks have been recorded at Clemson, Arizona State, Wisconsin, Penn State, Texas Tech — locations all over the map that opened their doors with more students and less stringent guidelines.

In May, as campuses mostly shut down to consider their future plans, USC’s Van Orman expressed hope that universities’ past experiences with international students and global outbreaks, such as SARS, would put them in a position to better plan for COVID-19. “In many ways, we’re one of the best-prepared sectors for this test,” she said.

Six months later, colleges are still being tested.

Mark Kreidler is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Fatal sip

Have some rum grog. Very fitting for the holidays.

Had I not tasted rum

I'd be content with juice,

But alcohol has newly made

My former tastes vamoose.

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman

This poem first appeared in The Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin and is reprinted with permission.

xxx

New England became British Colonial America’s distilling center for rum. The liquor is made from molasses, mostly from Caribbean slave-worked sugar plantations. New England’s rum leadership in the 17th and 18th centuries was due to its metalworking and cooperage skills and abundant lumber and its ports and other maritime shipping strengths.

Most New England rum was was lighter than others and more like whiskey. Much of the rum was exported, though New Englanders bought and drank a lot of it themselves. (They also drank a lot of ale and beer; drinking water could be dangerous.) But distillers in Newport also made an extra strong rum specifically to be used as slave-trade currency, and rum was even an accepted currency in Europe for a time.

New England’s role in the rum business was one reason that southern New England merchants got heavily into the slave trade. Africans, of course, were kidnapped and taken by the millions to the Western Hemisphere, mostly to work on the plantations.

The infamous “Triangular Trade.’’ “Sugar’’ means molasses.

British Royal Women’s Naval Service (“Wrens”) members serving rum to a sailor from a tub inscribed "The King God Bless Him" during World War II.

R.I.'s long and problematic name

Rhode Island founder Roger Williams with members of the Narragansett tribe circa 1636.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I always thought that Rhode Island’s official name was charming – “State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,’’ with “Plantations” simply referring to the colonial settlements on land that the English were enthusiastically stealing from those Native Americans who had survived diseases brought by Europeans to the New England coast starting at least as early as the beginning of the 17th Century.

But these are very sensitive times and “Plantations” is evoked to mean agricultural land (especially for cotton, tobacco and sugar) worked by slaves. Of course we should never forget that much of the American slave trade was run out of Rhode Island.

Okay. The people have spoken. Still, I’ll still miss the old line about “the smallest state and the longest name.’’ And I wonder how much it will cost to change all the state’s stationery, etc.

Gray flowers for a gray time

“Every Flower Touched” (handmade charcoal, commercial charcoal and wood ash on Fabriano), by Beatrice Modisett, at Montserrat College of Art, Beverly, Mass.

Montserrat says she uses “physical processes like working with charcoal to explore geology and erosion, along with the systems that humans create to navigate, control and contain the landscape around them.’’

Beverly, on the North Shore, is an unusual mix of Boston suburb, some of it rich and some of it middle class, summer resort and former major manufacturing center.

“View of the Beach at Beverly, Massachusetts, 1860,’’ John Frederick Kensett

1879 map of the sites of Beverly.

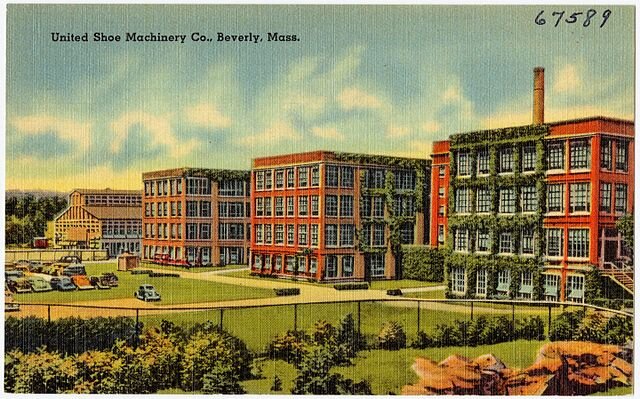

Vintage postcard of the long-gone United Shoe Machinery Corp’s flagship factory in Beverly, since repurposed.

Llewellyn King: Horrific holiday season; Pfizer vaccine developed in Germany, not U.S.

Nurse dealing with COVID-19 patient.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It is coming to us as a diabolical enemy: malign, merciless and murderous.

The second wave of COVID-19 will be killing us today, tomorrow, and on and on until a vaccine is administered not just to the willing recipients, but to the whole population. That could take years.

We haven’t been through anything like this since the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. Not only is COVID-19 set to kill many more of us than it already has, but it also is likely to have huge collateral damage.

Think restaurants: 60 percent of the individually owned ones are set to fail. Think real estate: The damage is so far too great and expanding too fast to calculate -- all those office buildings sitting empty, all those shopping centers being vacated. The real estate crisis is beginning, just beginning, to be felt by the banks. Think education: A year has been lost in education.

Our cultural institutions, from small sports teams to all the performing arts, are on death watch. How long can you hold a theater production company together? How do you save those very fragile temples of high culture, including ballet, opera and symphony music? What of the buildings that house them?

Now looming are the malevolent threats to Thanksgiving and Christmas. These festivals, so cherished, so looked forward to, such milestones of every year and our lives, are set to kill many of us, gathered in love and joy.

Families will assemble in happiness, but that diabolical guest COVID-19 will be taking its monstrous, lethal place at our tables -- at the very events that in normal times bind us together. Death will share our feasts.

These are words of alarm, and they are meant to be.

Nearly a quarter of a million of us have died, choked to death by the virus. Projected deaths are 110,000 more by New Year. Yet our leaders have spurned the modest defenses available to us: face masks and isolation. There is little usefulness in assigning blame, but there is blame, and it points upward.

But there is localized blame, too. Blame for what I see on the streets, where young people stroll without protecting themselves and others from the deadly virus. Blame for what I see at the shops, where customers gain entry without the modest consideration of wearing a face mask for a few minutes.

There is blame for pastors who have insisted on holding services that have spread COVID-19 to their parishioners. And there is blame for those who have rallied or taken to street demonstrations. The virus has no political affiliation, but politics has befriended it in awful ways.

The mother lode of blame must be put upon that increasingly bizarre figure Donald J. Trump, president of the United States, elected to lead and defend us.

Trump couldn’t have vanquished the pandemic, but he could have limited its spread. He could have guided the people, set an example, told the truth, unleashed consideration not invective.

He could have done his job.

When we needed information, we got lies; when we needed guidance, we were encouraged to take risks by myth and bad example. A high number of his own staff has been felled.

On Jan. 20, 2021, President-elect Joe Biden will step into this gigantic crisis. Even if the first doses of a vaccine are being administered, the crisis will still be in full flame, taking lives, destroying businesses, subtracting jobs, and changing the trajectory of the future.

There will be good, but it will take time to arrive. It will be in innovation in everything, from more medical research to start-ups and lessons learned about survival in crisis.

It will impact immigration. Only the willfully unobservant won’t note that a preponderance of the health authorities featured nightly on television weren’t born here, and their talent is a bonus for the country.

It should be noted that Pfizer’s landmark COVID-19 vaccine wasn’t developed in that U.S. pharmaceutical behemoth, but by a husband-and-wife team in a small company in Germany. Both are children of Turkish immigrants to that country.

In all countries, immigrants have had the adventurous spirit that is the soul of creativity. Let them in.

The "Wee Annie" statue, in Gourock, Scotland, has a face mask during the pandemic.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Pre-turbine wind power

“Brig ‘Cadet’ in Gloucester Harbor,’’ late 1840s (oil on canvas), by Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester. (Gift of Isabel Babson Lane).

Why Maine’s politically amoral Sen. Collins won

Seal of Sen. Susan Collins’s Trumpian heartland, Aroostook County, land of potatoes and moose.

Children gathering potatoes on a large farm in Aroostook County, 1940. Schools did not open until the potatoes were harvested.

— Photo by Jack Delano.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Perhaps the most-watched political event in New England in this political cycle was Maine Republican Sen. Susan Collins’s re-election victory over Maine House Speaker Sarah Gideon, a Democrat, which didn’t surprise me. Senator Collins, a cynic with very plastic principles, or perhaps none at all (recalling her deeply immoral Senate leader, Mitch McConnell, for whom money and power are all), won because she has provided very good constituent services and had deep support in the Trumpian northern part of the state, especially Aroostook County, where she’s from.

Her victory will help ensure that a President Biden will have a tough time getting his judicial and other nominees confirmed and make it more difficult for New England, as a region, if not Maine, to get its fair share of federal programs.

In a broken world

“Fusion of Work and Dream No. 1’’ (mixed media) by Barb Cone, in her show “The Fusion of Work and Dream (construction of broken things),’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Nov. 1.

Chris Powell: Serious cases, not tests, should measure pandemic

— Photo by Raimond Spekking

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Everybody is tired of the COVID-19 epidemic, and no one is more entitled to be tired of it than Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont. It has devastated the finances of state government, commandeered its management, crippled education at all levels, and worsened many social problems.

While people admire the governor's calm and conscientious manner, they may lose patience as his plan for returning Connecticut to normal starts reversing. Of course the epidemic is not the governor's fault and he deserves sympathy, but his reversal amid fears that the epidemic is surging again should prompt reconsideration of the measures being used to set policy.

Are the governor's premises correct?

The primary measure of the epidemic, in Connecticut and other states, is the "positivity rate," the percentage of daily virus tests reported as positive. One day about week ago the rate exceeded 6 percent, setting off hysteria among news organizations, before falling the next day to a more typical 3 percent. But these figures don't mean that 6 or 3 percent of the state's population is infected. These figures mean only that infection has reached those levels among people who chose to be tested in the previous several days.

Infection levels among the entire population of the state may be lower or higher than the daily "positivity rate." Paradoxically, a higher rate might be much better. That's because most people who contract the virus suffer no symptoms or only mild symptoms and do not require special treatment even as they gain antibodies conferring some immunity. Indeed, if the governor's data is analyzed in another way, so as to calculate what might be called the serious case rate, the positivity rate loses relevance, the virus looks less dangerous, and the epidemic looks less serious.

For the eight days from Oct. 26 through Nov. 2, the governor reported 7,806 new virus cases, 50 new "virus-associated" deaths, and 107 new hospitalizations. If deaths and new hospitalizations are totaled and categorized as serious cases, the serious case rate for those eight days was only 2 percent of all new cases, substantially below the positivity rate for those days -- 3.4 percent -- and way below the one-day positivity rate that caused alarm.

The mortality rate for the week was only six-tenths of 1 percent of all new cases -- and that is measured only against known new cases. If the mortality rate could be calculated from all new cases, including the week's unreported cases -- asymptomatic people -- it likely would be much smaller.

After all, it seems that 7,649 of the 7,806 people who figured in the virus reports for those eight days -- 98 percent of them -- were simply sent home to recover, perhaps with some over-the-counter or prescription medicine.

At the governor's Oct. 26 briefing Dr. John Murphy, chief executive of the Nuvance Health hospital network, tamped down the fright. Murphy noted that treatments for the virus have gotten much more effective since the epidemic began in March -- that while there is as yet no cure, there are medicines that slow the virus and aid recovery, and that as younger people with fewer underlying health problems have become infected, the virus fatality rate and the average length of hospitalization have fallen by half.

The great concern at the start of the epidemic -- hospital capacity -- remains valid, but it deserves reconsideration too. Back then the Connecticut National Guard set up field hospitals with nearly 1,700 beds, including more than 600 at the Connecticut Convention Center in Hartford. They weren't used before they were taken down, and with fewer than 400 virus patients hospitalized in the state last week, presumably the state, if pressed, could handle at least a quadrupling of patients.

None of this argues for carelessness, like that of college students partying in close quarters without masks, nor for reopening bars, where the virus may spread most easily. But it does argue for continuing the gradual reopening that was underway before a bad positivity rate scared everybody.

Of course, news organizations delight in scaring people with the positivity rate, but they are enabled in this by the governor's stressing it instead of the serious case rate.

If the infirm elderly and the chronically ill are better protected, fear may subside and relatively normal life may be possible again.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Brigham sets hospital fundraising record for Boston of $1.75 billion

Outside the Brigham

BOSTON

“Brigham and Women’s Hospital has completed its “Life. Giving. Breakthroughs” campaign, receiving over 200,000 donations from 80 countries. The donations totaled $1.75 billion, setting a new record for hospital fundraising in Boston.

The hospital’s campaign began in 2013 and includes a $50 million donation from Karen and Robert Hale for the new Hale Building for Transformative Medicine. Robert Hale is the co-owner of the Boston Celtics. The building, finished in 2016, is the first to have a 7-tesla MRI machine in North America. The funds also helped in building the Thea and James Stoneman Centennial Park, as well as doubling the size of the newborn intensive-care unit and the creation of a new Center for Child Development.

“These advancements underscore the power of philanthropy and the impact a grateful community can make when they give back to help others,” said Susan Rapple, senior vice president and chief development officer at the Brigham.

The New England Council congratulates Brigham and Women’s Hospital for this historic fundraising campaign. Read more here.”

Wouldn't want to waste her?

“After the cancer got down in his bones, old Bill

didn’t want much to kill — not even on the wing.

Still, he did have that crack young bitch Pointer Belle,

just now getting round to her best, her prime-years savvy,

Would she be the wrong damned creature ever to waste?’’

— From “Well, Everything,’’ by Sydney Lea, a former poet laureate of Vermont. He lives in Newbury, Vt.

A ruffled grouse, one of the most popular victims of New England hunters in the fall. The poem talks about grouse hunting.

The Connecticut River from Newbury, Vt,

Marker of former bridge in Newbury.

Murmur of a memory

“In places faded. Tonight a ghost, a murmur of a love epistle’’ (acrylic and mixed media on canvas), by Melissa Herrington, in her show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through Nov. 30’.

Masochistic meal preparation

Coot

“Everybody remembers the recipe for cooking a coot: put an ax in the pan with the coot, and when you can stick a fork in the ax the coot is done.’’

— John Gould, in “They Come High,’’ in New England: The Four Seasons (1980)

Coot hunting used to be a favorite coastal New England sport in November. My father was one of the enthusiasts for a few years, operating out of a duck blind on the shore of Massachusetts Bay. The culinary charms of these stringy, oily birds elude me.

— Robert Whitcomb

From Feathered Game of the Northeast (1907)

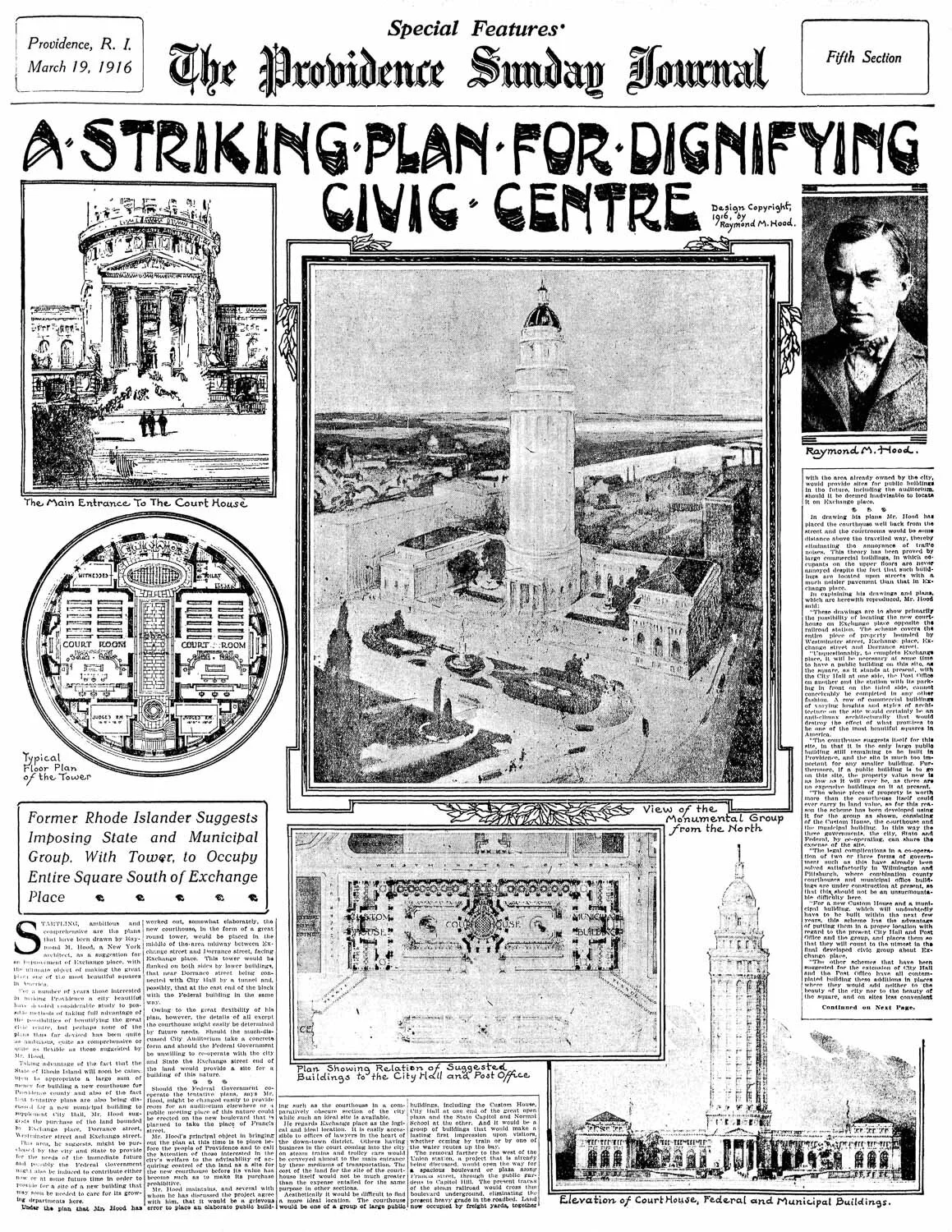

William Morgan: Raymond Hood and the drama of the American skyscraper

In 1916, a little known, 35-year-old architect and Rhode Island native proposed a monumental civic structure for downtown Providence. Raymond Hood's Civic Centre would have been sited where the Industrial Trust Building was later built; it was to be 600 feet tall and would serve as courthouse, library and prison. Its tower would symbolize progress and prosperity at the head of Narragansett Bay.

A few years earlier, Hood had done his thesis at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts, in Paris, on a design for a city hall for his hometown of Pawtucket. While neither of these fanciful schemes was built, they demonstrate the early vision of a man destined to become of one of the 20th Century's most significant skyscraper architects.

Raymond Hood, Proposed City Hall for Pawtucket. Year-Book of the Rhode Island Chapter, American Institute of American Institute of Architects, 1911

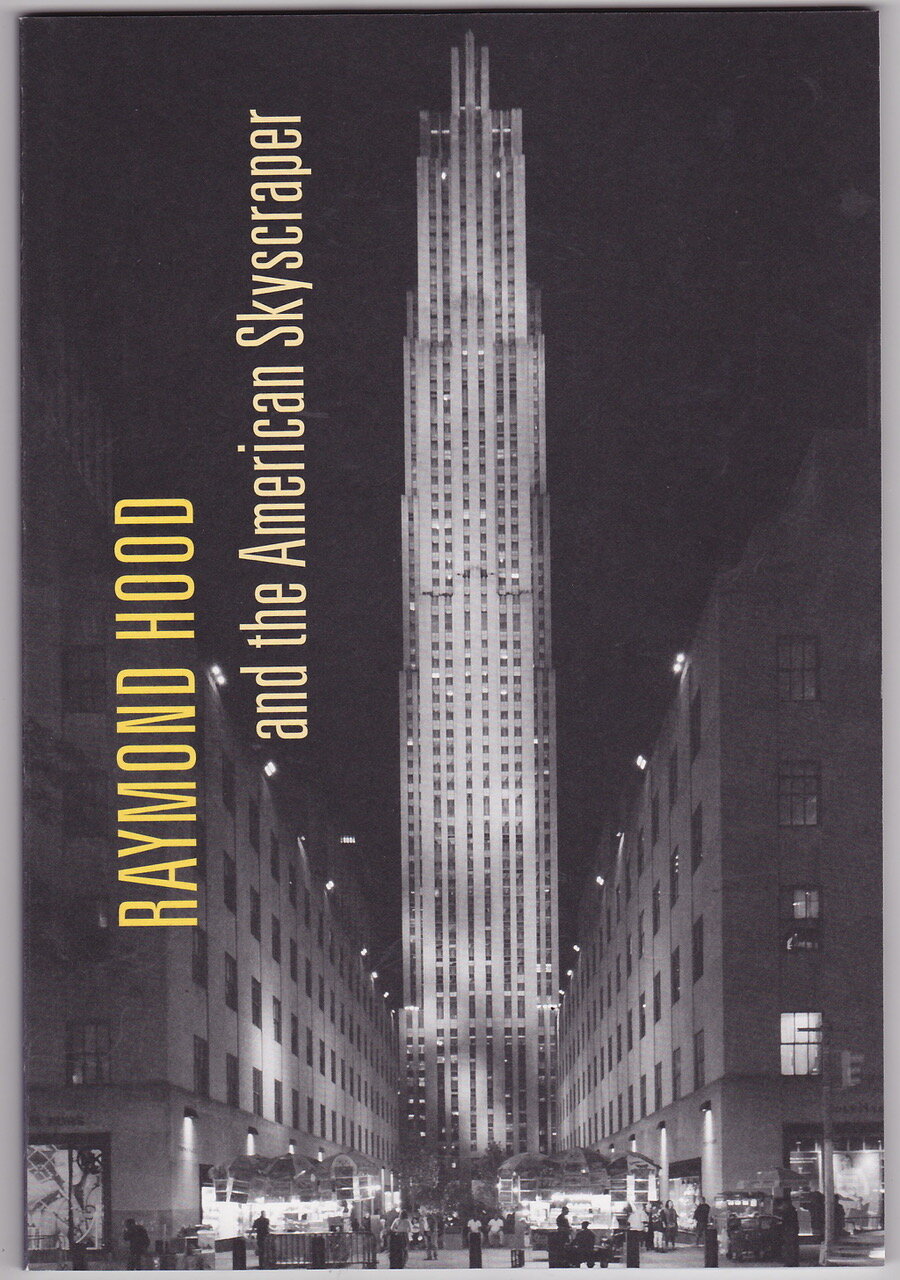

“Raymond Hood and the American Skyscraper,’’ an exhibition initially organized for showing to the public at the David Winton Bell Gallery, at Brown University, opened online only on Sept. 11. The show, underwritten by the Brown Arts Initiative and Shawmut Design & Construction, features loans of drawings and photographs from RISD, MIT, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania and the Smithsonian Institution. Hit this link to see the show.

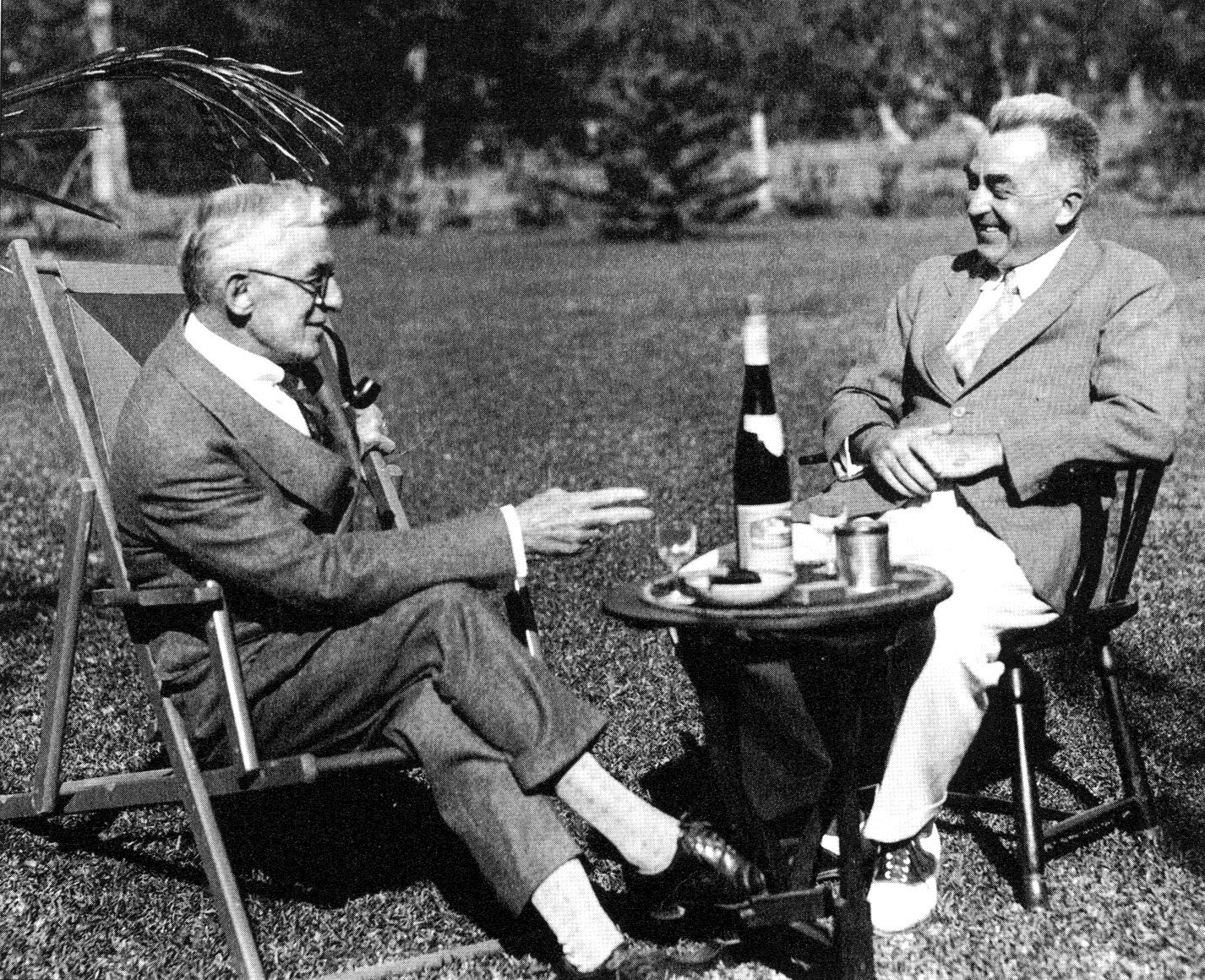

Ralph Adams Cram (left) and Raymond Hood in Bermuda, c.1930. Hood worked for Cram as a young architect; Cram designed the Pawtucket Public Library. Courtesy, Cram & Ferguson Architects

Beyond the lectures and other materials associated with the show, one can access information on Hood through the handsome 48-page catalog written by two of the show's co-curators, Prof. Dietrich Neumann and Brown doctoral student Jonathan Duval (the other curator is Jo-Ann Conklin, director of the Bell).

Catalog cover with Rockefeller Center, with the soaring RCA Building.

Hood would go on to design several iconic skyscrapers of the 1930s, serve as the head designer of Rockefeller Center, and would be, in Neumann's words "the most powerful architect in New York City." Significant exhibitions like this one reacquaint us with sometimes forgotten figures and force new assessments of their contributions to our cultural landscape.

RCA building at Rockefeller Center, photographed in 1933. Library of Congress.

Hood died far too young at 53. And in one of those ironies of architectural history, Modernists denigrated as too conservative the skyscraper that secured Hood's career and transformed him from dreamer to real player.

Howells & Hood, Chicago Tower. PHOTO ©Hassan Bagheri

As Neumann and Duval remind us, Hood was a struggling draftsman when he teamed up with the fashionable New York architect John Mead Howells (designer of Providence’s Turks Head Building) to enter the major international competition to build the Chicago Tribune's headquarters building in 1922. Howells and Hood beat out 262 other entrants from 23 countries with their skyscraper scheme.

I remember professors in college and graduate school ranting about the shortcomings of the Tribune Tower, labeling it "dishonest" for hiding its modern steel frame underneath a cloak of eclectic, historicist detail. It is time to acknowledge that Hood's design was the one that deserved to win, and to accept that the verticality of Gothic was wholly appropriate for such a soaring form.

Almost 100 years after that famous controversial contest, the Tribune Tower remains an absolute triumph, proudly standing in the skyscraper capital. Hood's more streamlined skyscrapers in New York – the RCA building, the Daily News Building and the McGraw-Hill Building – still inspire us, and they are especially instructive when placed against formless pieces of real estate such as Providence's proposed Fane Tower.

McGraw-Hill Building, New York, PHOTO © Hassan Bagheri

The effort that Brown has applied to the work of Raymond Hood is the sort of public service that universities offer the commonweal. Such scholarship is especially welcome now, as study of great architecture and urbanism is crucial to rebuilding after a time of pandemic.

Providence-based architecture critic and historian William Morgan has taught the history of architecture at Princeton University, The University of Louisville and Roger Williams University.

His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

Ross E. O'Hara: Online-learning advice for college students

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The majority of college students were largely disappointed by remote learning this past spring, with many reporting a strong preference for in-person instruction. Bearing in mind the low expectations that many students carried into online courses this fall, what advice can we give to help them succeed in this final month? As colleges across New England and the country continue to announce spring plans that include online courses, what can we share to prepare students for success in 2021?

While the internet is saturated with “hacks” for online learning, I want to connect you with the best experts I know: Students.

Since March, the Persistence Plus mobile nudging support platform has asked more than 25,000 students from both two- and four-year institutions about their experiences with remote learning. Specifically, we gathered their advice about how to excel in this format, and I saw four key themes emerge. I have also paired their insights with science-based exercises that can be shared with students to bolster their motivation and improve their performance in online courses.

1. Set a schedule. The most frequently offered advice was the need to set a regular schedule—especially in asynchronous courses—and stick to it. Several students mentioned examining the syllabus for major assignments and noting due dates in advance, working ahead on those assignments to the extent possible and regularly checking email and the course website. Here’s some of what they said:

“Make a schedule for classes, study time, completion of assignments, breaks, etc., and build enough discipline to stick to the schedule.”

“Make a schedule for time to study. Prioritize due dates on assignments and exams. It is not as difficult as you may think. Discipline and focus is key.”

“Work as far ahead as possible, get assignments done as soon as you get them so you don’t have to worry about it, and set a scheduled time each day to work on school.”

“Write everything down and log into your classes and email to check for new reminders and announcements every day.”

One way that students can go beyond just setting a schedule is with “if-then” plans. We all naturally underestimate how long it takes to complete projects (known as the planning fallacy). To counteract this optimism, students can make very specific plans for when and where they will work on assignments (for example, “I will read Chapter 1 at the dining room table after my daughter goes to sleep on Wednesday night.”) The more specific they are, the more likely they are to follow through.

Yet the best-laid schemes of mice and men oft go awry. Students should also develop contingency plans for common obstacles (such as “If my daughter doesn’t fall asleep by 9 p.m., then I will read Chapter 1 before she wakes up the next morning.”) No one can foresee the future, but anticipating the most likely problems and pre-designing solutions will help students stay on track. You can facilitate students’ if-then plans by prompting them to complete the exercise via an email, a poll within your institution’s learning management system, or even providing space in the syllabus to craft if-then plans for each big assignment.

2. Create a study space. Students noted how important it is to have a quiet, peaceful (but not too relaxing!) area for schoolwork. The goal of such a space is to create focus without inducing grogginess. They suggested:

“Find a place where you can be composed and stay focused with your priorities.”

“If you can, set aside someplace that is specially for school work so that you can focus when doing work and then relax when you go to bed (if you only have space in your bedroom then just make sure not to do work on your bed, work only on your desk).”

“Find a place in your home to go that is designated to your studies.”

“Don’t attend virtual classes in bed! Try working at a table or desk for effective productivity. Working in your bed allows you to be too comfortable and can cause you to fall asleep or lose focus.”

Given the COVID-19 pandemic, this area is most likely within students’ homes. But as we all know, our homes are often crowded with partners, children, parents and roommates. One advantage of a dedicated space is that it sends a signal that this person is studying and shouldn’t be interrupted. Moreover, a regular study space takes advantage of state-dependent memory. When you learn something, cues from the environment become associated with it: the feel of your chair, the smell of the room, the taste of your coffee, even your mood at that moment. If students put themselves into those same circumstances when they need to recall that information (i.e. for the exam), they’ll be more likely to remember.

3. Ask for help. We heard over and over that students must reach out for help, especially from their professors, if they get stuck. If you’re a professor but you might be difficult to reach (you’re dealing with plenty of crises too!) build a system that makes it easy for students to connect with other faculty, former students, campus tutors, tech support and each other. Students advised:

“Don’t be afraid to email professors and/or classmates/peers for understanding of the coursework and/or additional assistance.”

“Professors make it very easy, they work with you and they provide all the resources you need to be successful. Don’t forget to ask questions.”

“Make group messages with your peers so you can keep each other on track, and ask each other questions.”

“Don’t be afraid to reach out to classmates and ask for help. Everyone is going through it together and supporting each other through it is what makes it work.”

Asking for help makes some students feel nervous or embarrassed. One way to circumvent those feelings is to use simple role reversal. Instead of asking someone else for advice, students can imagine that one of their classmates came to them with the same issue. Students can then consider what they would advise their peer to do, or whom they would point them to for help. This role-playing can make students less anxious by approaching their own problem from a neutral perspective, make them feel more empowered, and help them generate potential solutions that they may not otherwise see.

4. Be accountable. Finally, students noted that success in online courses requires a lot of self-discipline and accountability. The physical and emotional distance between students and their professors can make it all the easier to skip assignments or not participate in class. They noted:

“It’s all about being on top of your work and holding yourself accountable. If you can handle online college classes, you can handle college.”

“Don’t put off projects and homework just because the deadline isn’t for a little while, you will forget and have to rush to finish it so just do it or start it (and do a good amount of the work) as soon as it is assigned.”

“Study just like you would if you were taking the class in a classroom. No matter where you are learning from, the same level of effort and focus is expected.”

It is challenging to maintain focus on learning online, while also working (or looking for work), raising children and dealing with life’s other responsibilities. One practice that may help students concentrate is to engage in 5-10 minutes of expressive writing before working on school. Ask students to privately jot down everything in their life that is worrying or stressing them out, and write specifically about how each one makes them feel. Rather than suppressing or ignoring their emotions, releasing them on paper lessens their impact and will allow students to better focus on learning or performing. They can even crumple up that piece of paper and toss it in a recycling bin, symbolically discarding those intrusive thoughts so they can get down to business.

Despite our general comfort level with technology, most of us are still unacquainted with experiencing most of our lives online, and things won’t be that much better as we continue remote learning into 2021. While students study algebra, or 20th Century European history or computer coding, remember that they’re still adapting to a whole new way of learning, and that’s not easy. So please pass along advice from our college experts to your students and their instructors so they may be better prepared for any eventual roadblock.

Ross E. O’Hara is director of behavioral science and education at Persistence Plus LLC, which is based in Boston.

Share This Page

Share this...

Filed under College Readiness, Commentary, Demography, Economy, Financing, Journal Type, Schools, Students, Technology, The Journal, Topic, Trends.

Salt water is contaminating wells in Rhode Island as sea level rises

From ecoRI News

Drinking water wells at homes along the Rhode Island coastline are being contaminated by an intrusion of salt water, and as sea levels rise and storm surge increases as a result of the changing climate, many more wells are likely to be at risk.

To address this situation, a team of University of Rhode Island researchers is conducting a series of geophysical tests to determine the extent of the problem.

“Salt water cannot be used for crop irrigation, it can’t be consumed by people, so this is a serious problem for people in communities that depend on freshwater groundwater,” said Soni Pradhanang, associate professor in the URI Department of Geosciences and the leader of the project. “We know there are many wells in close proximity to the coast that have saline water, and many others are vulnerable. Our goal is to document how far inland the salt water may travel and how long it stays saline.”

Salt water can find its way into well water in several ways, according to Pradhanang. It can flow into the well from above after running along the surface of the land, for instance, or it could be pushed into the aquifer from below. Sometimes it recedes on its own at the conclusion of a storm, while other times it remains a permanent problem.

Pradhanang and graduate student Jeeban Panthi are focusing their efforts along the edge of the salt ponds in Charlestown and South Kingstown, where the problem appears to be the most severe.

Since salt water is denser than fresh water, it typically settles below. So the scientists are using ground-penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tests — equipment loaned from the U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Department of Agriculture — to map the depth of the saltwater/freshwater interface.

“In coastal areas, there is always salt water beneath the fresh water in the aquifer, but the question is, how deep is the freshwater lens sitting on top of the salt water,” said Panthi, who also collaborates with URI professor Thomas Boving. “We want to know the dynamics of that interface.”

The URI researchers plan to drill two deep wells this month to study the geology of the area and the chemistry of the groundwater to verify the data collected in their geophysical tests.

The first tests were conducted in the summer of 2019, and a second series was completed this fall after being delayed by the pandemic. Final tests will be conducted this spring when groundwater levels should be at their peak.

“The groundwater level was at its lowest point in 10 years this summer because of the drought,” said Panthi, a native of Nepal who studied mountain hydrology before coming to URI. “That will be a good comparison against what we expect will be high levels in April and May.”

Panthi has collected well-water samples from nearly two dozen residences for analysis. One of the contaminated wells is a mile inland from Ninigret Pond, in Charlestown.

Ninigret Pond, in Charlestown, R.I.

“A homeowner had a deep well drilled for a new house and it ended up with extremely saline water,” Pradhanang said. “Deep wells close to the salt ponds or the coast are more likely to have saltwater intrusion than shallow wells, though shallow wells can also have problems if they become inundated with salt water.”

Another URI graduate student, Mamoon Ismail, is developing a model to simulate saltwater intrusion into drinking water wells based on the changing pattern of precipitation and the potential for extreme storms. They hope to be able to predict how far inland salt water will intrude following a Category 1 hurricane compared to a Category 2 storm, for instance.

This research is being funded by the Rhode Island office of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.