Thick nature and history in tiny 'Scratch Flat'

“The place is infused with time; everywhere you look, east or west, north or south, there is history; there are stories, and ghosts, and bear spirits.’’

— From Ceremonial Time, Fifteen Thousand Years on One Square Mile, by John Hanson Mitchell.

In it, he explores a single square mile in a section of Littleton, Mass., nicknamed “Scratch Flat’’ in the 19th Century, looking at history from the last Ice Age and the years of human settlement since then, including Native Americans and their bear shamans, early and later white colonists, witches, farmers (it’s a famous apple country) and later industrial “parks’’ The idea is to perceive past, present and future simultaneously.

Brian Wakamo: Sports walkouts: Imagine what an Amazon strike could do

Via OtherWords.org

First, the Milwaukee Bucks refused to take the court in their playoff game against the Orlando Magic. Then other teams followed suit, leading to a three-day wildcat strike in the National Basketball Association.

The Bucks were protesting the police shooting of Jacob Blake in nearby Kenosha, Wis., but they helped ignite a wave of athletic activism for racial justice. Other leagues followed suit.

Players in the women’s NBA, who often lead athlete protests, joined the strike. Some Major League Baseball teams — including the Milwaukee Brewers — refused to play multiple games as well. So did Major League Soccer players.

And Naomi Osaka, two-time tennis Grand Slam winner, announced she would not play her semi-final match as a protest. She next appeared wearing a face mask with Breonna Taylor’s name on it.

It was a seismic moment in the history of sports.

We’ve seen players use their platform to advocate for social justice, going all the way back to Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali and Billie Jean King. And we’ve seen players strike for better collective bargaining agreements.

What’s new are these labor actions for social justice — especially across multiple sports and leagues. It’s unprecedented.

These shows of strength and solidarity had immediate consequences, including at the NBA offices, where around 100 employees struck in solidarity. Within a few days, NBA owners and players announced a raft of initiatives to improve voter access in NBA arenas and to invest in a joint social justice coalition among coaches, players, and owners.

As these athletes have shown, striking does not need to be reserved exclusively for higher wages or a better contract. NBA players have a strong players union and an incredibly well negotiated collective bargaining agreement, but they knew they had the power to amplify a national conversation about police violence. It’s inspiring that they chose to use it.

It’s also an inspiring story about the power of all workers.

Few workers are as well paid as professional athletes, and most have more to lose from running afoul of their employers. But there’s a lesson here for them, too: Workers make the company run, not the CEOs and owners. Withholding that work can force immense changes.

After all, if a handful of athletes refusing to play can yield such immediate results, imagine what would happen if long-suffering, underpaid Amazon or Wal-Mart workers — or both — pulled off a national strike. They could virtually shut down the economy and win the fair treatment they’ve been demanding for years.

That’s what postal workers did in a 1970 postal strike, which completely halted all mail deliveries, even as President Nixon attempted to use the National Guard to deliver the mail. Nixon failed miserably, and postal workers won collective-bargaining rights, higher wages and the four postal unions we have today.

As for those well-paid athletes? I hope they’ll force their employers to take tangible steps in other fights — like for racial justice, a fairer immigration system, and action on climate change.

These athletes just showed us all a path forward. I hope more workers are inspired by their example.

Brian Wakamo is an inequality researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies.

The wet look

Watercolor by Megan Hinton in the program "Plein Air: Watercolor Revisited," at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum Sept. 10-Oct. 1. This is an in-person workshop to be held once a week from Sept. 10–Oct. 1 by Megan Hinton, an artist, art writer, educator and lecturer. The association says that "Plein Air aims to demystify watercolor, a medium often characterized as ‘unforgiving’ and requiring extreme precision to get right.

See:

To the rhythm of the crops

Children gathering potatoes on a large farm in Aroostook County in 1940. Back then, schools in what Mainers simply call “The County’’ did not open until the potatoes were harvested.

— Photo by Jack Delano

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Back when many Americans worked on farms (my maternal grandfather grew up on one) school calendars were adjusted to agricultural needs, especially to harvests. Thus in many school districts, young people didn’t go back to school until weeks later than they do now.

In a few places where agriculture is still paramount, special adjustments are still made. Consider Aroostook County, in northern Maine Trump Country, where (in-person!) schools open early to accommodate a break coming in late September so that the kids and teachers can help bring in the potato harvest.

I think that in general kids are now forced back to school too early, in the best part of summer – late August and early September.

Boston and the rest

Boston from the west

— Photo by Rebecca Kennison

“Reduced to simplest terms, New England consists of two regions: Boston and not Boston.

— Travel writer Wayne Curtis in Frommer’s 2001 New England

“{In} New York, the women walk as though in the rain; in Boston, many women stroll.’’

— Andre Dubus (1936-99), in Broken Vessels: Essays. The Louisiana-born writer ended up living in Haverhill, Mass., where he taught at Bradford College, a small private institution that closed in 2000, after a 197-year run, mostly as a women’s school. It’s now now the site of Northpoint Bible College.

Ignoring Vermont

“Vermont was like a wooer

whose attraction

you shut out, preoccupied

with a lifelong crush….’’

— From “Vermont Aisling,’’ by Greg Delanty, an Irish-American poet who teaches at St. Michael’s College, in Colchester, Vt.

A proposed community arts center for Worcester

The Worcester Art Museum from the Salisbury Street side. The distinguished museum has 38,000 art objects. It was built in 1898, in the heyday of Worcester’s industrial prosperity, which created some big fortunes and art patrons.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

The University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Center recently announced a $500,000 contribution to Creative Hub Worcester, a proposed community arts center. UMass Memorial stated that the investment in the project is to help improve the mental and emotional health of the Worcester community through creative expression.

The Creative Hub was founded by artists Stacy Lord and Lauren Marotta, who were $850,000 short of their fundraising goal, but have now been able to begin construction thanks to a flurry of recent contributions to the project. The Worcester Creative Hub will transform a former Boys and Girls Club into an event center, art studios, and child-care spaces. The goal of the center is to create a space for artistic expression and community well being.

“This project, this is health to me,” UMass Memorial Health Care President and CEO Dr. Eric Dickson said. “When I see the beautiful place that people are going to be able to come to, the events that will be occurring here in a part of the city that really needs some help, this is what we are committed to doing in addition to providing the great care to the patients we serve.”

The New England Council applauds UMass Memorial Health Center for this investment into the social, emotional and creative wellbeing of the Worcester community. Read more from MassLive and the Worcester Business Journal.

Out from our caves

“Contagion” (mixed media and collage), by Carolyn Newberger, in the group show “Light From Above: Emerging Out of Isolation,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Oct. 31.

See:

galateafineart.com

Llewellyn King: Trying to sanitize history is vandalism

"The Rhodes Colossus" – cartoon by Edward Linley Sambourne, published in Punch after Cecil John Rhodes announced plans for a telegraph line from Cape Town to Cairo in 1892.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

History is fragile. It needs to be handled with care. The trouble is that it is inevitably viewed through the prism of today, which can cast the good as bad and the bad as good.

That is why those who would edit it, sanitize it, or obscure it are, for the most part, vandals. It is in constant danger of being rewritten to accommodate current perceptions.

How has this worked? When Oscar Wilde was arrested on April 6, 1895 at the Cadogan Hotel, London, for “gross indecency” (homosexuality), he was widely denounced as a threat to everything of value and a danger to our morals. In New York, where several of his plays were packing in audiences, Wilde’s name was removed from the playbills, while the plays continued to run.

Today, those who would have him arrested would be arrested for hate speech. The prism has changed.

America’s great journalist H.L. Mencken has fallen into some disfavor because of notes in his private diaries which have been construed to be anti-Semitic and racist. But his genius is unassailable. If you doubt this, just read his work. Yet the National Press Club in Washington changed the name of its library to that of a minor benefactor because the great man in private diaries had entries which were construed to be anti-Semitic. You can find the offending sentences on the web and make your own decision about what he said to his diary in 1943.

A committee of the Council of the District of Columbia advanced a list of historical figures’ connections to slavery and oppression and recommended renaming dozens of public schools, parks and government buildings in the nation’s capital — including those named for George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and five other U.S. presidents. No one, it would seem, who drew breath at the time of the founding of the republic is safe from retrospective judgement and condemnation. Not even Benjamin Franklin, who told a Philadelphia matron that the Constitutional Convention had “given you a republic, if you can keep it.”

No historical figures, it would also seem, are safe from indictments leveled against them. Julius Caesar was a Roman imperialist. The French and the British should hate him. Should we therefore destroy statues of Caesar? Then we wouldn’t even know what he looked like.

English military and political leader Oliver Cromwell served as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland during the 1600s. But his actions in Ireland and Scotland were genocidal. He said of the luckless Irish at the Battle of Drogheda, “God made them as stubble to our swords.” Should his name and likeness be expunged from our public records? The Cromwell Road, one of the great thoroughfares of London would have to go. One shudders to think about the awfulness of Queen Victoria in this context.

History is dominated by great figures and they are a mixed lot. The new politically correct assessment of history extends into appending judgement of sex lives. Watch out John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. and even Catherine the Great.

Sixty years ago, those who could’ve been censored and removed from public life would’ve included gays down through the centuries, from Alexander the Great to former Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, who is also Muslim.

There is a lot of heavy lifting to be done if you’re going to measure the past against the values of the present.

This brings me to the difficult and contentious issue of the Confederacy and all those statues. Here, there is reason to respect the sensibilities of the African American community and at least remove statues to museums. The Confederate flag has become an in-your-face statement of white racism and shouldn’t be part of the celebration of Southern culture. These symbols aren’t yet confined to history’s grave but are part of a struggle that isn’t settled.

Oxford University has decided to remove a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, and there is a move to change the name of Rhodes Scholarships to something else. Mind you, not to give up the money that he gave for the scholarship, together with huge gifts to the university.

Rhodes was an imperialist. He wanted Britain to rule from Cape Town to Cairo, but he wasn't a monster. Ruthless in business, he introduced the first genuine open franchise to vote in Cape Colony when he was prime minister. His sending of a column of police – they weren’t soldiers – into Zimbabwe ended the genocidal war between the Matabele and the Shona. But a white colony run by whites for whites resulted.

For me, names and statues record history. They aren’t celebrations of wrongdoing. I would’ve liked to have seen a statue of Stalin, among the greatest monsters of the 20th Century, as he appeared to the Russian people. I think it is good when a small child asks in front of a statue, “Mom, who is that?”

History isn’t to be rewritten, but to be learned, otherwise we won’t know how we got here and what to avoid, as George Santayana pointed out.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Website: whchronicle.com

Tracey L. Rogers: Being Black is very bad for your health in America

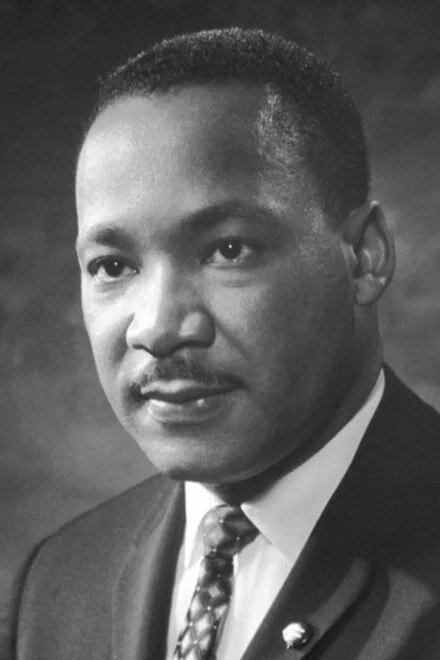

Martin Luther King Jr., ravaged by white racism

Via OtherWords.org

After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, on April 4, 1968, his autopsy report revealed that at the young age of 39, he had “the heart of a 60-year-old.”

Doctors concluded that King’s heart had aged due to the stress and pressure endured throughout his 13-year civil-rights career.

A 13-year tribulation sounds more fitting. Along with the victories he won through his long career preaching while organizing marches, boycotts and sit-ins, King also suffered from severe bouts of depression, received multiple threats on his life and the safety of his family, and was repeatedly arrested.

In fact, near the end of his life, as reported in Time magazine, Dr. King “confronted the uncertainty of his moral vision. He had underestimated how deeply the belief that white people matter more than others was ingrained in the habits of American life.”

There’s a reason why novelist and activist James Baldwin said in 1961, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all of the time,” a rage that weathers our bodies and psyches.

“It isn’t only what’s happening to you,” Baldwin explained. “It’s what’s happening all around you and all of the time in the face of the most extraordinary and criminal indifference, indifference of most white people in this country and their ignorance.”

As a Black woman and activist, I can say that my rage weathers me, too.

It can feel as subtle as the frustration I feel after receiving an e-mail from a white man accusing me of being a Marxist simply because I supported the Black Lives Matter movement (true story).

Or it can be as anguishing as the pain I feel simply thinking about Jacob Blake being shot in the back seven times at point-blank range by police in Kenosha, Wis.. Or the anger I feel about the president of the United States openly fomenting violence in the shooting’s aftermath, praising the 17-year-old white militia member who killed two protesters.

If Dr. King had the heart of a 60-year-old when he died, it’s easy to see how his fight for racial justice might have weathered him. But one might argue that its weathering began the moment he was born in the era of Jim Crow, just 64-years after the formal emancipation of enslaved people.

The all-around weathering of Black America is as big a part of our legacy as slavery, voting rights, and our commitment to freedom. It’s a weathering we experience every day, agitated by what’s been diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) passed on from generation to generation.

A few years ago, an article published in Teen Vogue explained how it was possible for Black people to inherit PTSD from our ancestors. It highlighted the “extensive research into epigenetics and the intergenerational transmission of trauma” by Dr. Rachel Yehuda, who found that “when people experience trauma, it changes their genes in a very specific and noticeable way.”

Sociologist Dr. Joy DeGruy coined the phrase “post-traumatic slave disorder” to describe the specific stress suffered by Black descendants of enslaved people, identifying the ways in which racialized trauma has had an emotional, physical, and psychological impact.

More recently, the Huffington Post reported that racial trauma increases the stress hormone cortisol in Black Americans, causing fatigue, depression and anxiety. Cities throughout the country have even issued declarations that racism is a public-health issue.

They’re right.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, many chronic illnesses are far more prevalent within the Black community. And there’s a growing consensus that these illnesses are a byproduct of everyday racism. “For Black people in particular,” said psychologist Dr. Lilian Comas-Diaz, “racial stress is something that happens throughout their life course.”

Whether it’s death by “weathering,” COVID-19, or inhumane policing, evidence shows that Black lives still don’t matter. And that’s why so many of us have taken to the streets — our hearts can’t take it anymore.

Tracey L. Rogers is an entrepreneur and activist in Philadelphia.

Dramatic dining in Newport

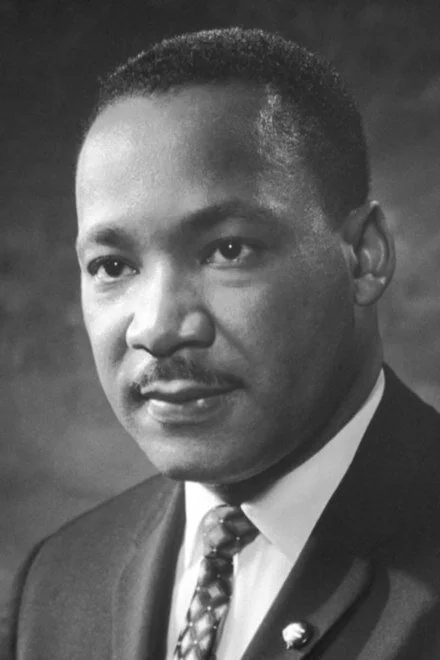

In a microburst, air moves in a downward motion until it hits ground level and then spreads outward in all directions. The wind regime in a microburst is opposite to that of a tornado.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

We witnessed a theatrical display of professionalism last Tuesday evening at the Reef Restaurant, on Newport Harbor, when out of not-very dark skies came a very brief but very violent storm of torrential rain and what seemed to be near-hurricane-force winds.

Most of the diners/drinkers, including us, were eating and drinking at the restaurant’s outside tables, with views of Newport Harbor and of giant yachts that evoked hedge funders and private-equity moguls, when the tempest hit. The four people in our party managed to get inside the restaurant ahead of most of the other guests; we were driven more by fear of being fried by lightning than getting wet. A few minutes before, our tall young waiter had promised that the storm, which we could see moving in from the west, wouldn’t bother us. One of our little group, a pilot, later explained that it was a microburst.

It was quite a scene as umbrellas, deck chairs, tables and potted palms went over.

What was most impressive, besides the drama of the storm itself, was how the waiters so calmly managed to get people quickly set up at tables inside, though they hadn’t time to rescue the food on the tables outside. Of course, social distancing was, er, incomplete in the brief chaos, and many who had fled inside had left their masks in the rain, some of which blew away and all of which were soaked.

Still, most of the guests seemed to enjoy the mayhem. I wonder how many got replacement meals and drinks.

xxx

The National Hurricane Center knows how to force fear. In alerting people in the northwest Gulf Coast to the menace of Hurricane Laura, it spoke of an “unsurvivable storm surge.’’

Winter looks better now

“Winter Sunrise Over Summer Street” (Boston) (oil on wood panel), by Chris Plunkett, in the group show “2020: Sharp Focus,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art through Sept. 27.

See:

https://www.fsfaboston.com/

and

https://www.chrisplunkettstudios.com/carousel.php?galleryID=208528

Open summer, squeezed summer

— Photo by Dietmar Rabich

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

We seem to remember the arc of summers much more than those of winters. I remember many individual summers with vividness; they were all so different. But I recall the summer of 1970 with particular sharpness. I had just graduated from college and, trying to decide whether I really wanted to go to graduate school, decided to take the summer off, helped by a few bucks I had saved up. I had had summer jobs since I was 14.

It was still in many ways the phenomenon called “The Sixties,’’ with sex, drugs and rock and roll, etc. Wide open. While I was mostly living in Greater Boston that summer, I spent a lot of time driving around the Northeast alone or with my girlfriend of the time seeing friends, hiking, fishing, going to parties, etc. It was my last extended stretch of free time up until, well, now. I had a VW Bug and felt pretty close to fancy free, jumping into the car at a moment’s notice for a road trip to the mountains, the Maine Coast or New York City, often driving off in the middle of the night.

I would have felt more guilty about “wasting time” like this except for some advice my father gave me around that time, which was to take some time off before truly adult duties came rushing it. He had done the same thing in the summer of 1939, right after his college graduation and after having had all-day summer jobs since his early teens; in having these jobs, he was lucky – it was, after, the Great Depression. That fall he went off to work for an industrial company, then came “The War’’ (as we always called it), marriage and five kids. He had few breaks until he died of a heart attack, in 1975.

In any event, I decided not to go to grad school that fall and instead went to work, in a business – a Boston newspaper -- with long and unpredictable hours. Grab the free time if you can.

A cool day in late August, breaking a heat wave, is enough to get you thinking of the brevity of summer and indeed of life.

A Squeezed Summer

Mobility is often associated with America, whether in pursuit of money or pleasure. So perhaps what many of us will most remember from this summer is its COVID-caused lack, what with states imposing draconian quarantine rules, transportation service cutbacks, and many places you’d otherwise visit closed for the duration, or forever. It’s been a tough summer to gain that brief sense of release that summer vacations well away from home bring. Lucky people at least have leafy neighborhoods to stroll in, preferably with water to look at

If a vaccine really does come along, the anti-vaxxers don’t ruin everything and the economy improves, will there be a surge of travel next year, or will a newly aroused fear of disease scare people away from travel, especially long-distance, for years, however strong their urge to get away?

Michael Tyre: Colleges must make physical campuses foster students' affinity

On the campus of Wellesley College, in Wellesley, Mass. It’s considered one of the loveliest campuses in America, which may help explain the high rate of alumnae donations to the women’s college.

Quinnipiac University’s Lender School of Business, with dome, with Sleeping Giant in background, in Hamden, Conn.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The brand of a college or university is more than its logo or tagline. It’s an accumulation of experiences for students, staff, faculty, alumni and community members. Marketing is part of it, but every time someone sets foot on your campus, they are walking into your brand.

This fall, fewer students will be on campuses and they may be there with less frequency. COVID-19 won’t last forever, but in a way, this year is a glimpse into the online learning future that was coming with or without a pandemic. It’s more important than ever that the physical campus foster in students a strong affinity for the school to keep enrollment, retention and alumni engagement numbers high. Without a deep connection to the physical place, students may fall into a commoditized mentality, enrolling in online courses where the prices are lowest and not thinking of themselves as an Owl, Bobcat or Camel.

There are four areas on a campus that can be designed or used in expressing the institution’s brand: interior spaces, buildings, outdoor spaces and the environment surrounding the campus. Below are one or more well-executed examples from each category, one of which I was involved in directly.

Walking inside your values

One way to more affordably and quickly align the brand of a particular college or program with its physical space is to work within the walls you already have. My team at Amenta Emma Architects and I recently redesigned the interior of the Lender School of Business at Quinnipiac University, in Hamden,Conn., to bring it in line with the school’s refocused identity.

With a glass dome against the backdrop of Sleeping Giant State Park, the exterior is an iconic part of the university’s brand. However, the interior, with muted colors and dim lighting, hailed from a Wall Street era of student aspirations and university curriculum. As with many business schools, there has been a shift in emphasis toward innovation and entrepreneurship, and the interior of the Lender School of Business had yet to catch up. The goal of our update was not just to reset the tone to reflect the work being done there currently, but also to change student expectations about the qualities they will be developing in themselves in this space.

The transformation used exposed ceilings, light colors and transparent materials to energize the programming. Colors and furniture play a central role in creating an impression that is contemporary in the App Development Center. The Financial Trading Center was given a refresh by way of accent colors and lighter colors on the ceiling to create a brighter space. To accommodate a change in pedagogy toward active learning, three small, traditional classrooms were converted to two collaborative classrooms with technology integrated into custom furniture and reconfigurable writing surfaces. The school’s history meets its future in wood wall panels with a cutout pattern that creates a “digital” impression that’s at once warm and forward-looking.

Start with words, then build from there

In our redesign of the interior of the Lender School of Business, words like “innovation,” “entrepreneurship” and “collaboration” fueled the process. When colleges and universities begin thinking about adding or replacing buildings on campus, I recommend that they start with words.

While it’s tempting to begin picturing the actual building (“It should be three stories and we want lots of glass,” or something similar) start by asking how the building relates to your institutional values and mission. What does it need to say or express about the university or a particular college? How should the space feel? When students approach the building and enter it, what words should describe their first impression? What will students feel empowered to do in this space?

When I think of a university using a campus building to differentiate itself, I go all the way back to 1826. That’s the year the University of Virginia (UVA) completed construction of the Rotunda at the head of its lawn. It’s a beautiful building, but what makes it unique isn’t so much its appearance, but the simple fact that it houses a library as the focal point of the quad, where other campuses may position a student center or church. UVA describes the Rotunda as the “architectural and academic heart of the university’s community of scholars,” and from day one, that’s the word it has embodied: scholarship.

For a more recent example, look to the University Center at the New School, in New York City. Transparent, crystalline stairwells are exposed to the Manhattan streets and a sign set against a red background inside the building and visible through windows seems to suggest, “Things are different and exciting here.” This overtly contemporary building reflects the school’s dedication to academic freedom and intellectual inquiry and telegraphs that this is a home for progressive thinkers.

Living out your campus identity

The Low Steps and Plaza at Columbia University are remarkable for the variety of activities that take place there. This plaza hosts open markets, concerts and the occasional demonstration. Located in the center of campus, it is a natural gathering place for students, faculty, staff and alumni and is infused with history and campus culture.

Not every campus has a Low Plaza or Harvard Yard, but most have an outdoor space which can be leveraged to promote community and a shared sense of identity. Central outdoor spaces often focus on a particular element—such as a bridge, clock or statue. It can even be a big rock if that says something about who you are. Embellishments such as paving, planting, furniture, lighting and graphics can create central spaces on campus in areas that may be lacking or underused. Repeating these elements on multiple campuses can unify the brand message within an institution that spans many locations within a city or even around the world.

These spaces come to life when students feel empowered to make them their own through scheduled events as well as impromptu activities. You don’t always need a big plaza-type formal space; something as simple as a porch with moveable chairs can be a welcome contrast to all of the restrictions students have to contend with right now due to COVID-19. With the design of the Middlesex Community College Dining Pavilion in Middletown, Conn., Amenta Emma aimed to create a campus living room. Adirondack chairs and picnic tables line a protected porch overlooking a large lawn banked by forest. The space reflects the open character of the college with community members, students, faculty and staff using it for events, meetings or individual study.

Inviting environs

The brand experience of a campus doesn’t begin and end with the property line. Views and surroundings shape the brand as well. Savvy institutions lean on their environs as a differentiator.

The homepage of the Web site for College of the Atlantic, in Bar Harbor, Maine, doesn’t show the campus. Online visitors are greeted with images of the countryside and the water. The campus has some iconic and historic architecture, but the institution recognizes that its identity and brand are explicitly tied to the location. The college focuses on the relationship between humans and the environment. By underscoring that nature is part of its campus, College of the Atlantic aims to attract students who are a good fit for its programs.

In stark contrast to College of the Atlantic is New York University (NYU), a campus whose buildings are woven into the fabric of the city. It makes a statement about its brand and the type of student experience it offers simply with its location. For colleges and universities without an obvious natural or urban asset in their surroundings, simply being aware of lines of sight and making sure air conditioners don’t obscure a pleasant view, for instance, can enhance the experience of being on campus.

Unmasking your culture

This year, as administrators look for creative ways to foster a sense of community that may be eroded in the wake of the pandemic and associated social distancing, it may seem like the campus you have is the campus you have. That’s not necessarily the case. Here are a few short-term ideas on how New England colleges and universities can leverage their brands this fall to make sure the campus still feels like home for students.

Our research has shown that students like to see their own faces and those of their peers in imagery associated with their college. Since your students’ faces likely will be obscured by masks while on campus this year, why not make use of otherwise blank spaces in hallways or building exteriors to hang large wall graphics or banners showing the student experience and featuring real, current students?

The pandemic, and its focus on avoiding crowded, indoor spaces, provides something of a license to make unusual use of outdoor spaces. Can aspects of student life or academics move outside? Are there spaces where additional seating can be added to encourage outdoor studying or eating? Could something dramatic with landscaping be done this year that is new, facilitates additional outdoor activities, and celebrates the school culture? Can you add more outdoor programming in the winter months with heaters, bonfires or events that make use of snow?

While use of school colors and logos on campus can be effective in moderation, difficult times like these call for a greater show of unity, which can be temporary. Boldly repainting interior and exterior spaces in school colors can always be undone if it seems over-the-top when the masks come off.

Trying as this academic year is going to be, there’s no better time to sharpen your institution’s brand and explore how it can be expressed on your campus in the long and short term. This year has truly tested what it means to be a student and an institution of higher education. The fact that colleges and universities need a strong value proposition to retain students on the physical campus has never been clearer.

Michael Tyre is a principal at Amenta Emma Architects, with offices in Hartford, Boston and New York City.

'Heal better than men'

Photo by Tero Laakso

“Above the town

lie its mountains —

ravaged by over-

cutting:

dark growth,

and hard wood,

But the mountains are open

in their sleep and

aloofness.

They heal better

than men.’’

— From “The Town That Ends the Road,’’ by Theodore Enslin (1925-2011), a long-time resident of Milbridge, Maine

View of Maine’s Frenchman’s Bay and Bar Harbor from Cadillac Mountain

But watch for nails

“Pickup Sticks” (Pocasset, on Cape Cod) (archival print), by Bobby Baker. Copyright Bobby Baker Fine Art.

Jill Richardson: KKK's old rhetoric sounds like Trump's

From OtherWords.org

Rory McVeigh wrote The Rise of the Ku Klux Klan, a study of the KKK in the 1920s, in 2009 — long before Donald Trump became president. But it could almost be about Trump today.

In the 1920s, white, male, U.S.-born Protestants worried they were losing status, economic clout, and political power.

Catholic and Jewish immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe were settling in large numbers in industrial cities, where they took unskilled, low-paid manufacturing jobs in large plants. Simultaneously, many African-Americans were moving north for industrial jobs. More women were working, too.

Many of the anxious white Protestants were skilled laborers or small business owners. Large companies, chain stores, and the Sears catalog were out-competing them throughout the country.

Feeling squeezed out by the changing economy, the KKK framed American jobs as the rightful property of what they called “100 percent Americans.” They wrapped themselves in the flag, claimed immigrants were stealing jobs, and attempted to deny African Americans any further mobility.

You’ve heard that “stealing our jobs” line before.

It was true that the structural changes from industrialization hurt many small businesses and skilled laborers in the 1920s, just as neoliberal globalization hurt many workers and their communities more recently.

Yet instead of confronting this economic system, hardline nativists then and now sought to preserve the livelihoods of white people by depriving everyone else — playing on the fears of white Americans to gain their support.

Here’s a sample comparison of 1920s KKK and Donald Trump quotes.

KKK: “Klansmen believe that the time is at least near when American citizenship must be protected by restricting franchise to men and women who are able through birth and education to understand Americanism.”

Donald Trump: “We’re looking at that very seriously, birthright citizenship, where you have a baby on our land, you walk over the border, have a baby — congratulations, the baby is now a U.S. citizen. … It’s frankly ridiculous.”

KKK: “Fifty thousand Mexicans have sneaked into the United States during the past few months and taken the jobs of Americans… All of the Mexicans are low type peons.”

Donald Trump: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

KKK: “The negro was brought to America. He came as a slave. We are in honor and duty bound to promote his health and happiness. But he cannot be assimilated… Rushing into cities, he is retrograding rather than advancing.”

Donald Trump: “Nobody has done more for black people than I have.” But also: “The Suburban Housewives of America” should “no longer be bothered or financially hurt by having low income housing built in your neighborhood.”

McVeigh wrote, “Black men who dared to associate with white women, or who dared to challenge racial inequality in any of its dimensions, were immune from the Klan’s paternalistic protection.”

Donald Trump wrote, “Bring back the death penalty” for the Central Park 5, a group of five Black men falsely accused and imprisoned for assaulting a white jogger.

And, of course, when Black people protested police brutality, Trump threatened them with “vicious dogs” and tweeted: “LAW & ORDER!”

One hundred years apart, they are saying the same things. When I quizzed a friend on who said what, she said she could only tell them apart because the Klan’s grammar was better than Trump’s.

Job losses and other economic pains must be addressed, but we can fix these problems in a way that’s inclusive, not violent and divisive. Instead, white nationalists from the Klan to Trump glorify a past in which white men had more power than everyone else, casting themselves as protectors of white America against inferior “others.”

Jill Richardson is a sociologist.

Put on your reopening list

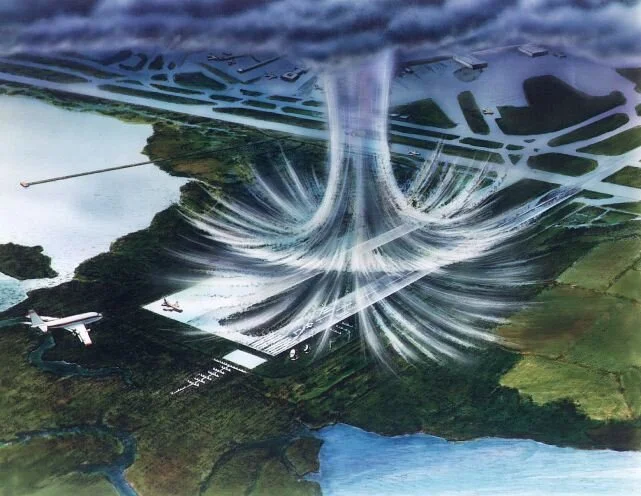

William (“Willit’’ ) Mason, M.D., has written has a delightful – and very handy -- book rich with photos and colorful anecdotes, called Guidebook to Historic Houses and Gardens in New England: 71 Sites from the Hudson Valley East (iUniverse, 240 pages. Paperback. $22.95). Oddly, given the cultural and historical richness of New England and the Hudson Valley, no one else has done a book quite like this before.

The blurb on the back of the book neatly summarizes his story.

“When Willit Mason retired in the summer of 2015, he and his wife decided to celebrate with a grand tour of the Berkshires and the Hudson Valley of New York.

While they intended to enjoy the area’s natural beauty, they also wanted to visit the numerous historic estates and gardens that lie along the Hudson River and the hills of the Berkshires.

But Mason could not find a guidebook highlighting the region’s houses and gardens, including their geographic context, strengths, and weaknesses. He had no way of knowing if one location offered a terrific horticultural experience with less historical value or vice versa.

Mason wrote this comprehensive guide of 71 historic New England houses and gardens to provide an overview of each site. Organized by region, it makes it easy to see as many historic houses and gardens in a limited time.

Filled with family histories, information on the architectural development of properties and overviews of gardens and their surroundings, this is a must-have guide for any New England traveler.’’

Dr. Mason noted of his tours: “Each visit has captured me in different ways, whether it be the scenic views, architecture of the houses, gardens and landscape architecture or collections of art. As we have learned from Downton Abbey, every house has its own personal story. And most of the original owners of the houses I visited in preparing the book have made significant contributions to American history.’’

To order a book, please go to www.willitmason.com

Resilient nature

From Linda Klein’s show “Nature Defiant,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Sept. 4-27. She explains:

“The content of this exhibit continues the direction I began in my 2004 exhibit, ‘Excess,’ about which I wrote, ‘My paintings and drawings came out of a conscious awareness of my anxiety about where we are going in our world.’

“Unlike the anxiety that I expressed in that exhibit, this work is devoted to celebrating the resilience of nature and enacting nature’s desire to assert itself through forms that derive from nature itself and flourish in the human imagination as it creates the forms of things unknown. When I began this process, many months ago, no one could have predicted the pandemic that has caused us all to pause. I too sometimes forget that we share this world with many life forms, unseen or ignored, until they assert themselves and demand my attention.’’

See:

https://www.lindakleinart.com/

and:

bromfieldgallery.com

'Ungainly mounds'

“In September and October one never walks or drives through this Connecticut Valley without smiling at these ungainly mounds of squashes and pumpkins heaped in uneven, bulging pyramids on green grass, or against barnyard fences, or under bright trees, or before the doors of farmhouses.’’

— Mary Ellen Chase (1887-1973), in A Journey to Boston (novel, 1965). She was a prolific novelist and essayist who taught for many years at Smith College, in Northampton, Mass., in the Connecticut River Valley.