They stay anyway

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Many are saying that remote working is making people reprioritize where they choose to live and work. It’s too early to say if we’re seeing a trend of people flocking to Rhode Island because it’s less expensive, more rural, has great amenities or a combination of all three, but it’s definitely something we’re studying. Rhode Island has always been a well-kept secret in terms of value, now perhaps, it’s not as much of a secret anymore.’’

-- Shannon Buss, president of the Rhode Island Association of Realtors, in GoLocalProv.com on people moving to Rhode Island since the pandemic began.

Hit this link:

I have always thought that the assertions that Rhode Island state and local government retirees flee in large numbers to lower-tax states were grossly exaggerated. People decide to move to, or stay in, places for many reasons, such as job options and weather, but most importantly because of their family and friends connections, and those are tight in the old and compact Ocean State. Now, The Boston Globe reports, Watchdog RI, a nonprofit founded by former Moderate and Republican Party candidate gubernatorial candidate Ken Block, who has often complained about public pensions and other things about this liberal state, has found that of 31,762 retired state and municipal retirees studied by the group, 80.3 percent retired in Rhode Island.

Mr. Block, a wizard at numbers, told the paper that he had expected twice as many of these public-sector retirees to be living out of state. “Certainly, the myth is that a lot of government employees retire and get out of Dodge,” he said. “That is clearly not the case.”

Even so, he told The Globe, $222 million in pension payments is being shipped out of state to these retirees each year, and he said, “That’s money that would be really nice to keep in state, if we could.” (It would be useful to get the numbers on what percentage of public-sector retirees leave other New England states.)

The list of the states where the largest numbers of the aforementioned Rhode Island retirees move to, as reported by Watchdog RI, are:

· Florida: 3,017

· Massachusetts: 1,195

· Connecticut: 237

· New Hampshire: 226

· South Carolina: 198

· North Carolina: 167

· Maine: 136

· Arizona: 118

· Texas: 88

· Georgia, Virginia (tied): 84

Interestingly, two of those states are, by national standards, high-tax when you combine state and local taxes – Connecticut and Maine; Massachusetts is in the middle, with New Hampshire a tad under the median. Generally, higher state and local taxes mean more, if not always better, public services, especially for that high-voting cohort called old people. State-by-state tax-burden comparisons are difficult because state and local tax systems vary widely, especially when you consider business taxes and what sort of purchases are covered by sales taxes.

You’d expect Florida, with its warm winter weather and generally low taxes, to lead in grabbing emigres from other states. (I wonder if that will continue after the COVID crisis there.)

Hit this link to read The Globe story:

Hit this link for some national tax comparisons:

https://wallethub.com/edu/best-worst-states-to-be-a-taxpayer/2416/

Hit this link for the Watchdog RI site:

Besides their human connections, many retirees stay in Rhode Island because much of it is beautiful and there are lots of services within short distances. Not much driving required.

Llewellyn King: COVID-19 has jump-started a revolution in how and where we live, work, shop

Many malls will empty out.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Dimly through the fog of the future some structures are emerging.

Some of the purely physical are becoming discernible. The changes in work, collective consciousness and play are harder to bring into focus.

We -- call us a ravaged generation -- will face a future, the future indicative, radically different from that past which we have known.

The obvious is that work is changed, rearranged and at times lost. A lot of real estate will be begging for a mission or will have to face the wrecker’s ball. Shopping centers will see huge change, maybe devastation.

Those big-box stores that anchored shopping centers will be fewer. Some might be converted to gyms or old-fashioned markets with dozens of small stalls. But these uses are limited, and those cinder-block behemoths are many.

Some have suggested that big-box stores can be converted to affordable housing. But architects say it is easier to knock them down and build new homes on their sites. Like the bomb craters that dotted London after World War II, these will be a kind of ruin for some time, a reminder as to how life was.

After the shopping centers, come the office buildings -- the very symbol of a modern city, from the grand Empire State Building, in New York, to the flashy, mostly glass Shard skyscraper, in London, to the wildly imaginative buildings that were built as symbols around the world as much as needed work space. Now they’ll be sentinels of the city of the past.

The short story is that fewer people will be going back to work in offices. Telecommuting has rapidly come of age; it is acceptable and even desirable. Many, like myself, won’t like it.

Human contact has been part of work since urbanization began. Indications are that we’re going to be less urbanized, more suburbanized and ruralized.

People who have commuted vast distances into cities -- like those who left home at 4 a.m. in Connecticut to be at their desks in Manhattan at 8 a.m. -- will sleep in without guilt.

It isn’t just that COVID-19 has forced us to work differently, at home and separated, it’s that digitization has matured enough to make it possible, almost in confluence with the demands of life under the virus. Magically, Zoom has changed just about everything. It’s been not only a liberating force, but also a force for change.

But huge change and the innovation that will accompany it will have a price.

One survey found that 53 percent of the nation’s restaurants will never reopen, and a lot of wonderful people will be out of work -- for a long time. Restaurateurs are the most entrepreneurial of people, and many will open new venues. But that takes time and capital.

This loss of traditional work, which applies across the hospitality industry, will have deleterious impacts elsewhere. For example, the fishing industry can’t sell all its catch. It has always heavily depended on restaurants.

COVID-19 isn’t alone in reshaping the future. For years digitization and artificial intelligence, which have made telecommuting possible, have been subtracting jobs.

Farming, for example, is undergoing relentless change. Today’s farmer is more a systems manager than the renaissance figure of the past who could help a cow give birth, repair a tractor, taste soil to determine its pH, and handle the harvest with migrant help. Now tractors and farm equipment are fully digitized and can operate from a laptop on a kitchen table, and the harvest is increasingly automated by sensitive robots with multiple sensors guiding kind claws.

It's a new world and we need to be brave and imaginative to master it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

See:

whchronicle.com

Beach bathos; save our shellfishermen

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo has rightfully cut back parking at Scarborough and Misquamicut state beaches because of overcrowding, especially by young adults (many from out of state) who ignore social-distancing and face-mask directives. But anyway, I have always been surprised by the number of people who want to crowd together on a hot humid day on a beach, pandemic or not. A nice seat in an air-conditioned room or a walk in the mountains seems more inviting in mid-summer.

Meanwhile, it’s depressing to see the number of jerks who give retail people, such as at ice-cream stores, a hard time when the latter try to enforce pandemic guidelines. There are enough such people to have led a few store owners to decide to close for the duration. Selfish people making a tough period worse!

Of course mask-wearing is capitulation to the “liberal elite”!

New Shell Games

The shellfish industry – both wild-caught and aquaculture-grown -- is over-dependent on the restaurant industry and thus has been slammed during the pandemic. Many restaurants are reopening, but only at 50 percent or less capacity, and some have closed permanently.

So the oyster, quahog, soft-shell clam and mussel collectors are working hard to develop direct relations with consumers, with the latter going directly to oyster and other cooperatives to buy the stuff, to farmers markets and supermarkets or even have them delivered to homes and places of business. It reminds me of the fish man who would peddle his stuff, right off the boat and put on ice and covered with canvas, at the back of his truck, around our coastal town when I was a kid. (Was that illegal?)

Shellfishermen are just so New England. Let’s support them.

Disease threatens beech trees

North American beech tree in the fall

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) is asking residents to monitor beech trees for signs of leaf damage from beech leaf disease (BLD). Early symptoms include dark striping on a tree’s leaves parallel to the leaf veins and are best seen by looking upward into a backlit canopy.

The dark striping is caused by thickening of the leaf. Lighter, chlorotic striping may also occur. Both fully mature and young, emerging leaves show symptoms. Eventually, the affected foliage withers, dries, and yellows. Drastic leaf loss occurs for heavily symptomatic leaves during the growing season and may appear as early as June, while asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic leaves show no or minimal leaf loss. Bud and leaf production also are impacted.

BLD was detected in the Ashaway area of Hopkinton and in coastal Massachusetts this year, according to DEM. Before these findings, the disease was only known to be in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut. The disease is caused by a kind of nematode, microscopic worms that are the most numerically abundant animals on the planet.

While there are good species of nematodes, the BLD nematodes cause leaf damage that leads to tree decline and death. At this time, they are known to only affect American, European, and Oriental beech species. Currently, there is no defined treatment, as nematodes are difficult to control in the forest environment. Research is underway to identify possible treatments for landscape trees.

All ages and size of beech are affected, although the rate of decline can vary based on tree size. In larger trees, disease progression is slower, beginning in the lower branches of the tree and moving upward. The disease also appears to spread faster between beech trees that are growing in clone clusters, as it can spread through their connected root systems. Most mortality occurs in saplings within two to five years. Where established, BLD mortality of sapling-sized trees can reach more than 90 percent, according to DEM.

The state agency encourages homeowners and forest landowners to monitor their beech trees and report any suspected cases of BLD to DEM’s Invasive Species Sighting Report.

Bill Hall: The big gamble of 'early haying' in Vermont

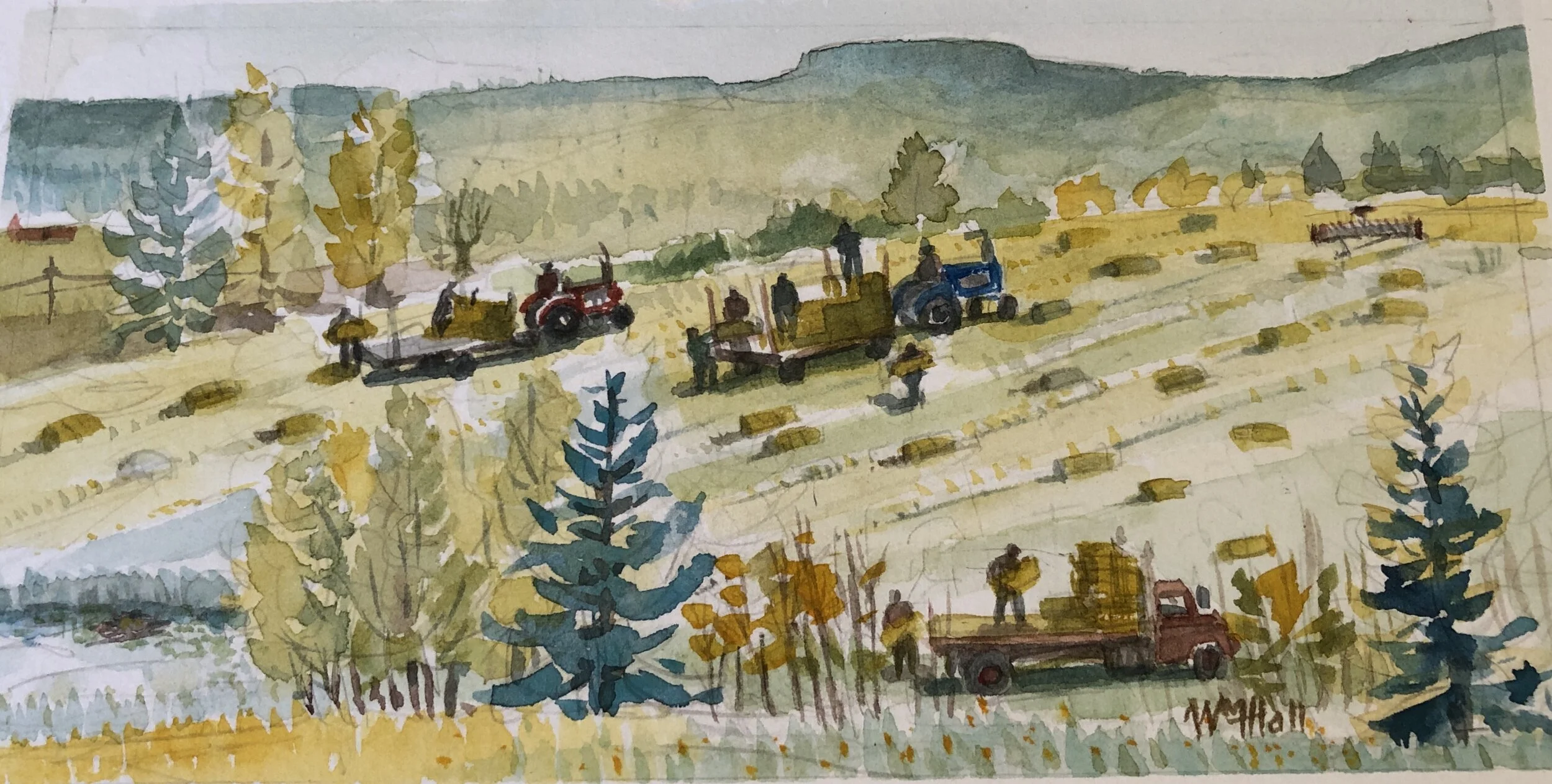

“Harvesting the Hay Crop on Deadline’’

— Watercolor by Bill Hall

In late May it could get hot in Vermont’s Connecticut River “Upper Valley’’. You shifted slowly from here to there, but you had to move. If you didn’t you’d swear you would suffocate. You weren’t avoiding the oppressive heat as much as you were looking for some air to breath. Shade didn’t help much; it only served to dull the searing brightness. The heat was just there. If you were a farmer you had to get used to it, and get things done anyway. One of those things might have been to get in the early (season’s first) crop of hay: “early hay”.

In that sudden sweltering heat, you had to decide:

“Hay or no hay”?

Once you decided to hay, you had to do it fast. After the brutality of winter and the torrents of “mud season,” after the financial reality of dairy farming sank in once again, you had to get moving. You might put off the question of buying new equipment by fixing the old. Or should you pay down your loan?

Farmers in the Connecticut River Valley had to weigh the costs and rewards of throwing the dice once again. Would they risk an early haying or would they fold and walk away? That was the big gamble.

Early hay or “spring mow” sounds simple enough to a non-farmer. The common question asked, “Is it possible?” The correct answer is, “No, in most cases,” due to weather, which is always uncertain in northern New England. “Then, is it necessary,” you might ask?

In some professions, such as insurance, determining possibilities is a scientific matter, but in farming it’s just called “gambling”. My street-smart father called it “ The Farmers’ Hat-Trick”. He explained it to my brother and me as he shifted three dried butternut half-shells around on the kitchen table in short quick movements, one shell concealing a dried pea seed. You know this game. Which shell hides the pea? This was to demonstrate how, by a game he called “slight-of-hand,” farmers plotted to sneak a full barn of early hay right out from under the nose of a vengeful God.

My brother and I did not realize we were also getting a lesson about my father’s religious beliefs, seasoned by his ironic sense of humor. He was a traveling farm-equipment salesman who served a big territory. He understood farming, but elected to travel in a wider circle of go-getter types. He was also kind and sympathetic. By the end of the lesson he had impressed upon us how daring farmers were for trying to beat the heavy odds against succeeding at a harvest of early hay while it was still mud season. Dad called a career that required dealing with weather “a fool’s guess”. We also learned why we were lucky to be able to watch and understand this unfolding lesson where we could see it, in our own pastures. But we were safe from the financial challenges. My father traded the hay to our neighbors, the Vaughans, just to get our fields hayed, addressing the need to keep out brambles and weeds that cows shouldn’t eat, and to provide us with enough hay for our modest needs, which were for bedding, fodder and scratch hay for my grandfather’s turkeys and chickens (and their eggs)

Quirky local weather is king

Vermont has many microclimates, in part because of its geological history. Small farmers work every inch of that glorious land from the highest pastures of the Green Mountains to the floor of the Connecticut River Valley. Our 50-acre farm lay like a door-mat on the fertile plain of that valley, but the rush to harvest an early hay, or the decision not to attempt it, was happening everywhere in our little state, and all at once.

We would get news from Father’s weekly travels about the haying elsewhere. “They’re still not mowing in the Champlain Valley” maybe he’d report. He had seen bales in a high pasture over in the Vershire Hills, just west of us, but they were covered with snow and so on. Our total focus was on our two flat 25-acre fields, one on each side of our farm house. We knew from the farm kids at school that other farmers were ramping up to mow, rake, flip, dry and bale new hay everywhere around us, as soon as the weather permitted.

My father joked that if God controlled the weather then he was the one who needed to be appeased, fooled, dazzled or distracted. “He can be a practical joker at times,” he said, winking. The question was, if a farmer was going to sneak in such a neat stunt as an early hay harvest shouldn’t the farmer be very careful? If God knew, might he put obstacles in the farmers’ way? As our minister said, “To test him, to test his devotion”? It seemed like there was a, “side bet” between our dad and “Our Father”.

The tension was growing.

It was pre-spring. The days alternated between snow and mud. Most farmers were gun-shy and dazed by the deep dark winter they had just endured. Already skeptical about the benevolence of their God, a farmer could get discouraged from being house-bound and barricaded in their dark barns all winter dealing with rodents, frozen pipes and coughing cows. When the farmers returned to their kitchens, wives were waiting with “payable notices” illustrating the folly of a farming life. They felt vulnerable. The prospect of an early haying seemed further away than ever, but then it did every year.

Mud season was next. It held hands with winter. Those two soulless bullies worked together to test farmers’ resolve. Farmers felt helpless in their grip, and the sun seemed in cahoots with those darker elements of life because it offered only a few short winks in early May. “Was this spring”, they asked? It sleeted in April and froze tight every night for days sometimes, and maybe served up a blizzard for breakfast. Levity and faith were long gone by the time that the spring mud started to shift consistency from stinking brown glue in the barnyard to something more solid. But the fields were still soaking wet.

Wet fields? Were they the death warrant for early hay crops? A wet field normally meant one inaccessible to heavy farm equipment, and therefore useless until dry, but with a little luck and intense sunshine the ground might give rise to the green gold of the grass seeds within. If they could just get enough sunshine those seeds would explode to become a free bonanza of green early hay, but only in a field dry enough to work in. A windfall crop of sweet green hay would feed a farmer’s cows until the second haying season, in July, and would ensure that no hay need be purchased in the upcoming calendar year.

In Vermont the “early hay’’ was originally called “early mow’’. It was not baled. Teams of as few as two and sometimes as many as six work horses or mules hauled a man around who worked with horses, a “teamster,” upon a wood-frame contraption that combined pre- and post-industrial wood and metal embellishments. The wooden frame was as elegant as any stage coach and the iron parts included shiny as well as rusty parts, such as shearing bars, worm gears and iron seats.

The early mowers worked mechanically like a thousand men with sickles to lay the new grass low. Horse-drawn mechanical flippers or men with wooden rakes turned the grass over, on the same day it was mowed. This, done properly, dried out the hay enough to be “put-away”. Horse-drawn wagons were filled to the tops with loosely piled hay, which was lifted up using mechanical pulleys to be placed drooping over drying beams in the tops of barns, where the hay’s sweet perfume cleansed the stale air from the winter just passed. It was said such a barn was made “happy” by new hay. Cows’ eyes bulged upward as they bellowed in the milking level below as if trying to see through the floor above to the new hay they longed for.

This horse-powered equipment provided an advantage in its day. It could be operated in soaked fields before mud season had subsided, allowing access to wet fields without damaging them, as the weight of modern tractors, balers and trucks would have. Waiting for the proper surface conditions in those fields is what made the modern early hay process such a crap shoot .

Hay could be harvested when it was ready without farmers having to wait for equipment and manpower to converge on a field en masse. It could be gradually harvested more times during the season as it grew. The process was more controllable and flexible.

Above all it was a soulful process for both man and beast. There are still a few Vermont farmers who maintain horse and mule teams and the revered equipment that goes with farms with horses. Admiring them are amateur teamsters, purists, history buffs and people who still prefer the music of men’s voices coaxing animals forward to the sound of diesel tractors and metal balers. In some areas, drivers still park their cars along dirt roads in silent observance of this sacred event. But farming with horses has come to be seen as too slow and out of step with the times.

For the modern farmer and his quest for that early hay, he could only hope that his organizational skills and gambling spirit would see him through. These days, there are detailed weather predictions, radar and and satellite maps to show the regional picture, but it’s his personal experience and knowledge of his region that best tell him when to cut his hay. In our case in Thetford everything was temporary and nothing was as it seemed. It’s complicated. It tests your commitment. It leads you on. It dares you.

Is there enough time?

The fog over the valley floor and the heavy moisture it brings almost every day will dissipate by 9 a.m. if the sun is shining. Then will come a breeze. The heat of the sun on the valley floor will cause up-drafts, which will flow west through the hills of Vermont or east toward the hills on the New Hampshire side. In between is some of the most fertile soil in New England. The question is, can you wait for the sun to do its work and can you commit manpower and other resources enough to get the job done in time? If the farmer has his own hay-processing equipment, no matter how advanced, from cutting to storage, he’s in a stronger position; no one can let him down if he does it himself.

When it came to our two fields we aced it, but it was close. When the weather report said “no way” we had it hayed anyway. The Vaughan family, our aforementioned neighbors, made it happen. They arrived en masse when they saw that the rain that had been predicted for that morning did not fall. Sunny skies were forecast. The Vaughans made a commitment to cut both of our fields that day. They’d flip and rake them alternately and move from one field to another with Big-Red, the baler. We could see that there was still standing water near the fire pond (a source of water to put out barn fires) behind the barn. That area would be dry by midsummer and would have to wait.

The intense ‘baling day’

The Vaughans used two cutting tractors to get the hay down fast; both were working simultaneously. The flipper and rake alternated between the two fields.

Then came “baling day”. One year, the sky was overcast and the forecast was for rain by noon. As we had to wait for the morning dew to dry off, we were worried, but committed. The Vaughan family patriarch was unconcerned. Robert Vaughan Sr., who looked like someone in a Vermeer painting, decided that the hay would get baled and then stacked in his big barn by the end of that day, and that was that. Even if some of the last bales got a little wet, “We’re doing it”.

Just in case, he directed a couple of his five sons to go to the Vaughans’ barn and set up drying racks, where they’d be exposed to wind from the two enormous fans they had just installed. These fans were six feet wide and made the ends of the barn resemble an aircraft-test wind tunnel. This flow would ensure that our hay would retain its dryness in case the rain fell on the last day before we got the hay stacked. Mr. Vaughan wanted the new hay treated gingerly because it had a high alfalfa content and a limited tolerance to too much jostling.

Unlike with August haying, the alfalfa would stay in this new hay. When dry that early alfalfa would resemble flaked butterfly wings and if handled roughly would flutter down from the bottoms of the bales. This essence of the “first cut” must be maintained, otherwise why bother? Dryness was dicey for other reasons. The “good moisture” content was tricky to maintain, and “bad or deep moisture” would cause rot that would spread to hay around it.

Every bale in that bountiful harvest was loaded and trucked to the barn. The last three truckloads were stacked with the help of headlights of the other trucks and tractor. If we were lucky, the rain that might have been predicted held off until the last truck was mostly filled. A large tarp was fixed over the top and flapped wildly as we drove to the barn, where it was unloaded in the big alley in the center. Everyone helped and so it took only a few minutes. Then the big fans were turned on for the night. The sound that followed the throwing of the main switch gave the event a science-fiction feel. The fans chilled us as the breeze dried our sweaty, itchy backs. We would all seek relief lying in front of those fans in the sweltering days to come.

My brother and I always remember those times when the early hay was brought in.

Bill Hall is an artist based in Florida and Rhode Island. Hit this link.

Thetford, Vt. in 1912

— Photo by Mike Kirby

Invasive little pet turtles

Red-Eared Sliders

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

They are the most popular pet turtle in the United States and available at pet shops around the world, but because Red-Eared Sliders live for about 30 years, they are often released where they don’t belong after pet owners tire of them. As a result, they are considered one of the world’s 100 most invasive species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Southern New England isn’t immune to the problems they cause.

“I hear the same story again and again,” said herpetologist Scott Buchanan, a wildlife biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. “‘We bought this turtle for a few dollars when Johnny was 8, he had it for 10 years and now he’s going to college, so we put it in a local pond.’ That’s been the story for hundreds and thousands of kids in recent decades.”

Red-Eared Sliders are native to the Southeast and south-central United States and northern Mexico, where they are commonly found in a variety of ponds and wetlands. Buchanan said they are tolerant of human disturbance and tolerant of pollution, and they are dietary generalists, so they can live almost anywhere. And they do. They breed throughout much of Australia as a result of pets being released, and in Southeast Asia they are raised as an agricultural crop and have displaced numerous native species. In the Northeast, they live in the same habitat as Eastern Painted Turtles, one of the area’s most common species, but they grow about 50 percent larger. Numerous studies suggest that sliders outcompete native turtles for food, nesting, and basking sites.

Despite concerns about their impact on native turtle populations, red-eared sliders are still legal to buy in Rhode Island and most of the United States, though Buchanan said that in the Ocean State they may only be sold by a licensed pet dealer and can’t be transported across state lines. Those who buy a slider must keep it indoors and must never release it into the wild, including into a private pond.

“But people often aren’t aware of the regulations, or they don’t bother to look at them, or they just don’t follow them,” Buchanan said. “We see lots of evidence of sliders, especially in parts of the state where there are lots of people. The abundance of Red-Eared Sliders in Rhode Island is tied to human population density, which means mostly Providence and the surrounding communities. But I’ve also found them in Newport and Narragansett and elsewhere.”

Sliders are especially common in the ponds at Roger Williams Park, in Providence, and in the Blackstone River.

While conducting research for his doctorate at the University of Rhode Island from 2013 to 2016, Buchanan surveyed ponds throughout the state looking for spotted turtles, a species of conservation concern in the region. During his research, he also documented other turtle species, including many red-eared sliders.

“The good news was that while spotted turtles can occupy the same habitat as red-eared sliders, I found a greater probability of occupancy by spotted turtles at the opposite end of the human density spectrum as I found sliders,” he said. “Spotted turtles tend to occur where human population density is low, so at least at this moment in time, we would not expect red-eared sliders to be directly competing with populations of spotted turtles.”

Nonetheless, Buchanan advocates what he calls a “containment policy” to keep the sliders from expanding their range in the state.

“It’s mostly about public education,” he said. “We want to make sure people know not to release them in their local wetlands. If we found sliders in an important conservation area — Arcadia, for example — we might consider removing them, though we’re not doing that now.

“They’re well-established in Rhode Island now, so the thought of eradicating them does not seem like a feasible management solution. We just have to live with them, but we also have to try to minimize their spread and colonization of new wetlands.”

No other non-native turtle from the pet trade besides the Red-Eared Slider has been found to be a common sight in the wild in Rhode Island, though Buchanan said he recently had a report of a Russian tortoise — another popular pet — that was discovered wandering around Coventry.

For those who want to get rid of a pet Red-Eared Slider, Buchanan doesn’t offer any easy alternatives.

“You’ve got to be committed to housing that turtle for 30 or 40 years until it dies,” he said. “That’s why this is such a problematic issue. It’s easy to buy a teeny turtle for ten bucks and think it’s no big deal, but that animal is going to live for a long time. When you purchase it, you have to be responsible for it for the rest of the turtle’s life.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Grace Kelly: Light pollution hurts a wide range of animals, including humans

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

You might not think much about the light on your porch, or the cute lanterns that line the pathway up to your door. But shining a little illumination on the situation of light pollution reveals that it can have a bigger impact than you might think.

“The spread of electric lighting in particular has provided a major perturbation to natural light regimes, and in consequence arguably a rather novel environmental pressure, disrupting natural cycles of light and darkness,” according to a 2013 report.

Bright city lights distract and disorient migratory birds, often causing them to collide with tall buildings. It’s estimated that about 985 million birds are killed this way annually in the United States alone.

Beyond birds, light pollution is also affecting insects, according to a recent study titled Light pollution is a driver of insect declines.

“We strongly believe artificial light at night — in combination with habitat loss, chemical pollution, invasive species, and climate change — is driving insect declines,” the scientist authors concluded after assessing more than 150 studies. “We posit here that artificial light at night is another important — but often overlooked — bringer of the insect apocalypse.”

Artificial light can hinder insect courtship and mating, and car lights lead to hundreds of billions of insect deaths each year in Germany alone.

In Rhode Island and much of the rest of New Eng the story is no different.

“Pretty much all of the Northeast is super light-saturated and has huge amounts of light pollution,” said Kim Calcagno, Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s manager of the Powder Mill Ledges Wildlife Refuge, in Smithfield, R.I., and the Florence Sutherland Fort & Richard Knight Fort Nature Refuge in North Smithfield, R.I.. “And with the main refuge that I manage at our headquarters in Smithfield, I can’t even do most night hikes anymore because there’s so much light pollution, and if affects the wildlife so much that it’s just not worth it, because we don’t hear or see anything a lot of the time.”

Beyond disorienting birds or indirectly causing their death, light pollution can also impact Rhode Island’s migratory bird flyways.

In a 2017 ecoRI News article, ornithologist Charles Clarkson, who worked with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management to collect local bird-migration data, said, “We’ve confirmed what we’ve always suspected: Rhode Island is a very important stopover site for migrants.”

Birds migrating north along the Atlantic Flyway travel west of Rhode Island, while those that travel south in the fall cross through the state. Light pollution can disrupt these paths, confusing birds and causing them to miss vital stops along their migration.

“Birds that migrate, songbirds especially, usually migrate at night,” Calcagno said. “So light pollution can disorient them, can cause them to hit buildings, and it can cause them to be attracted to certain lighting. We have resorts and hotels and all these things along the coast which can affect them. It can cause a lot of birds to not go the way they’re supposed to go; or it can increase mortality from strikes; or they may even fly too far over the ocean to get away from the light, get exhausted and fall out of the sky and not survive.”

One essential stop on many a migratory bird’s journey is the Ninigret Pond and Conservation Areas in Charlestown, R.I., a town that prides itself on land preservation, lack of development, and its lighting ordinance.

“Charlestown has a lot of open space — about 46 percent of the town is preserved in some form or another,” said Ruth Platner, a longtime member of the Charlestown Planning Commission. “Ninigret wildlife refuge is really important for bird migrations because it’s one of the first places that has food and provides rest. The refuge itself is dark, but then the areas around it, we'd like them to stay dark, too.”

Enacted in 2012, the town’s Dark Sky Lighting ordinance provides rules for light use and installation, ranging from rules relegating lights in outdoor activity areas to sign illumination.

“It’s only for commercial use. We wanted to do it for everything, but at the time, the council approved it for commercial,” Platner said. “So, for new constructions and adding new fixtures, they have to be full cutoff fixtures, which means the light is fully within the figure. All the light should be going down and not out, and definitely not up.”

Southern New England isn’t all that dark at night. (NASA)

Human health impacts

Light pollution can also disturb the very people illuminating the world at night.

Nighttime lighting “is associated with reduced sleep times, dissatisfaction with sleep quality, excessive sleepiness, impaired daytime functioning, and obesity,” according to the American Medical Association.

“My friend who is astronomer had a neighbor who had a super-bright spotlight, and the spotlight was shining into her house, like so much so that his light was invading her interior space even after she bought blackout curtains,” said Kimberly Arcand, a science communicator and the visualization and emerging technology lead for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. “It can affect your mental health if you've got a bright spotlight shining into your living room every night.”

Her friend, Tracy Prell, an executive board member of Skyscrapers Inc., the Amateur Astronomical Society of Rhode Island, has been battling the light pollution around her East Providence townhouse for years.

“When I first moved here, I didn’t think anything of it, but then I was outside and my neighbors turned on their floodlights,” she said. “A couple times one had left them on overnight. She turns the outside light on because she has to let her dog out, and I’m thinking, do animals really need that much light to see? Two hundred watts? Her light illuminates my living room.”

Prell has asked for her neighbors to point the lights downward or to get a shield, but it has been hard to convince them to reduce their light pollution — unless saving money is mentioned. While she has found resistance, she hopes that through education, people will be inspired to make a change.

Arcand, who is also a Rhode Island resident, feels similarly, and has long been passionate about light pollution, primarily because it’s a problem that anyone can take action to reduce.

“I think one of the reasons I like light pollution so much as a topic is because as an individual … there are accessible, actionable things that you can do to reduce light pollution in your home,” she said.

Such actions include installing motion-sensor lights in your yard, angling outdoor lights in a certain way to reduce glare, using warm color LEDs, or simply turning off your lights when you’re not using them. You can even go beyond your personal impact and take action to reduce light pollution in your community.

“If you're at all interested in going beyond personal responsibilities, there are a number of committees created or in existence to work on changing the lighting in a given town,” Arcand said. “Guiding town decisions in a way that reduces light pollution while also reducing energy use and still keeping things safely lit, it’s just a win-win.”

Grace Kelly is a reporter with ecoRI News.

Health-care behemoth coming for a tiny state?

Behemoth as depicted in the Dictionnaire Infernal

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Good out of bad? Lifespan and Care New England, Rhode Island’s two big “nonprofit’’ hospital systems, have had to tightly coordinate their responses to the COVID-19 crisis – an experience that has led them to revive merger or at least “collaboration’’ plans. A merger might save on administrative and other costs borne by the public and enable the state to have a system big and strong enough to compete with the Boston health-care behemoth by maintaining a full-range of medical services and research in the Ocean State and by strengthening its only schools of medicine and public health, at Brown University. A merger might preserve a lot of jobs in Rhode Island. But at the same time, many jobs would presumably be lost as the merged company eliminated redundancies.

Of course, such a large and powerful merged entity would have to be carefully regulated. As Michael Fine, M.D., warned last week in GoLocal, such mergers have tended to raise health-care consumers’ costs because of the monopoly pricing-power created. And I wonder what gigantic golden parachutes, paid for indirectly by the public, would go to Lifespan and Care New England senior executives in a merger.

To read Dr. Fine’s comments, please hit this link.

Todd McLeish: Threats to Rhode Island's rare plants

Salt-marsh pink

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Only two populations of salt-marsh pink are left in Rhode Island, and they are at risk from sea-level rise.

David Gregg worries that not enough is being done to protect Rhode Island’s rare plants.

“There are a lot of plant species that we’re monitoring out of existence,” said Gregg, the executive director of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. “We check them every year, and there are often fewer of them each year. The best-case scenario is that they stay the same, but many populations are getting smaller and smaller.”

He believes that conservationists must be bolder during the climate crisis if native wild plants are going to survive in the coming decades. Rather than simply monitoring the status of rare plants in Rhode Island, he is advocating for the use of more active strategies to boost plant populations.

“There’s been a big debate among biologists about how active we should be in trying to save rare species,” Gregg said. “Are we going to end up gardening nature? Aren’t we bound to make faulty decisions? If we get involved in active management of rare species, aren’t we doomed to screw it up?”

With little left to lose in some cases, the Natural History Survey has chosen to partner with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and the Native Plant Trust — formerly the New England Wild Flower Society — on an effort to propagate select species of rare plants and transplant them into the wild to augment existing wild populations and establish new populations.

The “Rhode Island At-risk Plant Propagation Project” is an outgrowth of the Rhody Native program, which was established a decade ago to help commercial plant growers propagate native plants for retail sale. At its peak, the program was growing 50 different species, but eventually just one species became dominant, a salt marsh grass used in restoration projects.

“Rhody Native became a commodity growing project, and that’s not our business,” Gregg said. “Our strength is in rare species — learning to propagate them and experimenting with them.”

The Natural History Survey’s “Propagation Project” began last year with the selection of four plants to propagate to test the concept: salt-marsh pink; wild indigo; wild lupine; and several varieties of native milkweed. The lupine and indigo were selected in part because they are the food plant for a rare butterfly, the frosted elfin. Just two populations of salt-marsh pink are left in Rhode Island, and they are at risk from sea-level rise.

“Our populations of marsh pink have very few plants, and we’re worried about inbreeding,” Gregg said. “The idea is to take plants from a Connecticut restoration site, cross pollinate them with plants from Rhode Island to reduce inbreeding, and then return some to Connecticut and use the others to reinforce the Rhode Island populations.”

The big challenge with this kind of project is learning how to propagate the plants in a greenhouse setting.

“These aren’t domesticated plants we’re working with,” said Hope Leeson, a botanist for the Natural History Survey who led the Rhody Native program. “We have to imitate the environmental conditions the plants are adapted to — the temperature, humidity, soil, water, and other factors.”

Salt-marsh pink is a particularly challenging example. It’s an annual species that produces a large quantity of seeds in a good year, but the seeds are extremely small — Leeson described them as “dust-like” — and they don’t tolerate drying, so they can’t be stored over the winter.

“We collected seeds in October and had to sow them immediately,” she said. “In the wild, they grow in a band of vegetation along the top of a salt marsh, where it’s a moist sandy soil mixed with peat. Periodically it floods as the tide comes in and then drains. I’ve got to come up with a soil mixture that’s like the natural conditions to make the plant happy.”

Wild indigo, on the other hand, is very drought tolerant and doesn’t grow well in moist or humid conditions. Its seeds, like those of wild lupine, must be scarified before they will germinate.

“A lot of species in the pea family have a hard seed coat that keeps them from taking in water until conditions are right for germinating,” Leeson said. “In the wild, lupine grows in sandy, gravely soil, so the seeds are likely to get abraded by the sand over the winter, allowing it to take in water to trigger the process of coming out of dormancy.”

To get lupine and indigo seeds to germinate, Leeson must first scratch them with sandpaper to simulate the natural scarification process.

Leeson and volunteers from the Rhode Island Wild Plant Society are raising many of the target plants in greenhouses at the University of Rhode Island’s East Farm and at a private site in Portsmouth.

Gregg said the project is being undertaken on a shoestring budget to demonstrate it’s potential.

“We hope someone will realize that we have this unique capacity to do research propagation of rare plants, and maybe that will help us find some funders to support the project,” he said.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Annie Sherman: Expect warmer and wetter

From ecoRi News (ecori.org)

Did you notice that it snowed so little last winter that you barely shoveled, plus it never turned brutally cold? Or that the daffodils bloomed a few weeks earlier this spring? And that there were scores of jellyfish in April, while we typically don’t have to avoid them until summer?

While you might have relished the lack of shoveling and the premature blooms, these regional weather events weren’t random occurrences. They are ongoing evidence. Weather experts across the globe have been citing warmer weather and its consequences for decades, so the four straight warmer-than-normal months — December through March — in the Northeast shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Since 1998, the country has experienced the 10 warmest years on record, and seasonal snowfall from Washington, D.C., to Boston is 1-2 feet below average, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

This year claimed the second-warmest January-February on record, marking the end of the second-warmest winter on record, trailing the 2016 high by only half a degree, according to NOAA. The average global land and ocean surface temperature for January-February was 2.09 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the 20th-century average of 53.8 degrees.

These numbers indicate a New England winter that was particularly warm for myriad reasons. While global warming tops the list of culprits, we also can blame an erratic jet stream that trapped cold air in the polar region, creating the frequent phenomenon called Arctic oscillation.

“When we have mild winter conditions, it’s driven by a positive phase due to the jet stream position — narrow, fast-moving air currents at 30,000 feet. Currents flow west to east circling the planet, so this winter the jet stream shifted north, trapping cold air in the high latitudes,” said Isaac Ginis, an oceanographer, hurricane expert and professor at the University of Rhode Island. “It was a warm winter everywhere. They brought in fake snow for Moscow’s new year celebrations. Ski resorts were closed in Asia. It was a very odd winter, but we have seen it before.”

A similar phenomenon causes many of our weather events, including cold, rainy springs and blistering-hot summers. Last summer, the jet stream wobbled again, trapping warm air here that led to an extended heat wave; while earlier this month, the jet stream pushed down a lobe of cold air, causing unusually brisk May nights.

This fluky weather, which is common to New England, can be influenced by global warming, Ginis said. Since the jet stream is maintained by temperature differences between the cooler polar vortex in the Arctic and warmer air masses to the south, the jet stream is stronger when this temperature difference is large, and it’s weaker when the variance is slight. Some studies suggest that the jet stream will become wavier, and we’ll have more frequent instances of colder winters and hotter summers. Though Ginis said the jet stream meanders all the time, it’s unusual for it to stay in the same place for months, as we saw this winter, and it’s doing so more frequently, which points to a greater climate shift.

“Although we still don’t fully understand the increased waviness of the jet stream that causes severe weather, it is likely to be associated with global warming,” Ginis said. “But this is the area of active research; computer models are still not very good at predicting longer-term changes in weather.”

Storm clouds on horizon

While NOAA reported that the Northeast was 3.8-4.1 degrees above normal this winter, it also reported one of the wettest winters, with 0.92 inches above average rain accumulation. April continued the wet trend, according to the Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell University. The National Weather Service has predicted above-normal precipitation and temperatures for April through June. So, while most of us in Rhode Island anticipate a chilly, damp spring, we hope for more than 12 days a month of clear skies.

“I didn’t think this spring would be this cold. And we were in a pattern that every two or three days we got rain. It’s good because it’s kept the reservoirs up, but Scituate Reservoir is full,” said Lenny Giuliano, state meteorologist and atmospheric scientist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. “My concern is when we get a three-inch-plus rain event. The Scituate Reservoir can handle an inch every three days, but if we get a whopper, it puts more water in the reservoir and they have to let more water out, which floods the Pawtuxet River. It’s not a very deep river, so it could flood low-lying neighborhoods.”

Giuliano has recorded the state’s weather impacts for 27 years, and advises Gov. Gina Raimondo for best practices during snow storms and hurricanes. He confirmed the NOAA reports that each decade since 1930, average temperatures have risen 0.3 degrees and precipitation has increased at a rate of nearly 1 inch. He warned that these small increments of warmer temperatures and additional precipitation might not be much if they occur just once, but they add up to shocking environmental shifts year over year.

“Temperatures are warming, and warm air can hold more moisture than cold air, so that means a warmer world is a wetter world,” Giuliano wrote in his annual climate report. “Rhode Island has already experienced increased rainfall and more frequent heavy precipitation events, with corresponding increases in river and stream flooding. Ocean water temperatures are warming, which can result in storms being stronger and more intense than they otherwise would be. Plus, sea level is rising, which means coastal flooding will occur more frequently and likely will be worse than otherwise would be the case for a given severity of storm. The combination of sea level rise and beach erosion dramatically increases the vulnerability along the coast, which translates into the potential for more damaging storm surge-driven coastal flooding; and development along the coastline places more property and people at risk.”

Janet Freedman is concerned also. As a coastal geologist for the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council, she has evaluated coastal resiliency and flood mitigation, policy, and practice for more than two decades. While she isn’t an expert on jellyfish or Arctic oscillation, she understands quite well what can happen when we repeatedly get more weird weather than our coastal state can handle.

Though Rhode Island hasn’t experienced a really big storm yet this year, she said we are seeing more nuisance flooding, also called high-tide flooding, which happens when we get the type and frequency of precipitation that April brought — it rained every few days, accumulating to nearly 6 inches, which raised the Ocean State’s water table. And when we get a hurricane, she said, the rising sea will make the flood threat dire.

“We are seeing more and more frequent extreme high-tide events,” Freedman said. “We often have a predicted high tide, around a full or new moon, but it’ll actually be a foot or two higher, so low areas like Oakland Beach in Warwick or Market Street in Warren flood.”

Flooding through stormwater infrastructure is another issue, Freedman said. When the sea level is already high, it moves backwards through stormwater systems, so incoming rain has nowhere to go and backs up onto city streets.

“Right now, we’re seeing it several times a year, and we expect to see more,” she said.

The domino effect doesn’t stop there. The state is doing more testing to show how local marine species and waters are impacted by more frequent rainfall. Since so much of Rhode Island’s land is paved or covered by other impervious surfaces, all that water drains directly into Narragansett Bay, dumping contaminants such as fertilizers, petrochemicals, and pet waste into the state’s most important economic resource.

“When I was a kid, we had sprinkles. Now we get torrential downpours that cause flooding on local streets. That has a big impact on water quality,” said Dave Prescott, Save The Bay’s South County coastkeeper. “Bigger precipitation events wash more pollutants into the bay and salt ponds, which compromises the health of marine animals like oysters and flounder, but also our own health, because we swim and kayak all over the place.”

Sign of the times

During his daily rounds of the local watersheds in April, Prescott noticed blue crabs common in the Chesapeake Bay and scup from as far as South Carolina that have been invading local waters for years, while more tropical fish such as bigeyes, striped burrfish and filefish are more recent southern refugees.

Meanwhile, the bounteous lobsters that Prescott was accustomed to seeing in our usually cold waters are no longer in such plentiful supply. Seeing these species fluctuate is an alarming notion for Prescott, and if we continue with this warming trend, he said, we’ll see big swings of southern species making a permanent home here.

“All taken separately, it’s not much. But these small changes are connected. And that’s the piece that is a little troublesome,” he said. “Some of these storms hitting the Gulf of Mexico are so intense because the water is so warm. And then we have winters that are next to nothing, which leads to ticks and mosquitoes. To suppress the tick population, we need a cold winter with a heavy frost. In addition, they are already spraying Chapman Pond in Westerly for mosquitoes, and last year they sprayed everywhere for mosquitoes. It’s already an issue, and as it warms up, this will get worse.”

You might be wondering what flooding and ticks have to do with a warm winter and early daffodil blooms?

These experts say these issues are dependent on one another. Freedman said a rainy April and sea-level rise are connected. Giuliano said the rise in pesky insects are directly attributed to a warmer winter. Ginis said these changes can be due to a warming of the earth’s atmosphere.

So as global land and ocean surface temperatures continue to rise, the effects are more widespread than we might initially realize — from certain fish arriving earlier in the season to global warming-stimulated jet streams bringing warmer winters and more frequent and extreme rain storms that cause local flooding and erosion to skyrocketing tick and mosquito populations.

“Be aware of your surroundings, be aware that things are changing,” Prescott said. “The sun is coming out now but over the past two days we had 1.5 inches of rain. More rainfall means more runoff, means more potentially polluted water. Understand that our climate is changing, and there may be some positives, but there will be some negatives that can impact our lives.”

Annie Sherman is an eco RI News contributor.

Don't worry yet about 'murder hornets' in N.E., at least not yet

Asian giant hornet

— Photo from Washington State Department of Agriculture

From ecoRi News (ecori.org)

News of the arrival in North America of a non-native insect with the terrifying colloquial name of “murder hornet” has alarmed residents nationwide. But a University of Rhode Island entomologist said there is little reason for Rhode Islanders {and thus by implication New Englanders in general} to worry about them.

Two murder hornets, which are more appropriately called Asian giant hornets, were discovered in Washington State in December shortly after a nest was discovered in nearby British Columbia. Native to Japan, where they are responsible for about 50 human deaths annually, the 2-inch-long insects with orange heads and black eyes are best known for their foraging behavior of ripping the heads off honeybees and feeding the rest of the bees’ bodies to their young.

“Their reputation as murder hornets comes from the fact that they can kill a lot of honeybees in a very short period of time,” URI entomologist Lisa Tewksbury said. “The major concern about their arrival in North America is for the damage they could cause to commercial honeybees used for pollinating agricultural fields. They are capable of quickly destroying beehives.”

Tewksbury said the hornet’s sting isn’t any more toxic than that of the bees and hornets commonly found in New England, but because of their large size, Asian giant hornets can deliver a larger dose of toxin with each sting. They are a danger to humans only when stung multiple times, according to Tewksbury.

“But they’re not known to aggressively attack humans,” she said. “It only happens occasionally and randomly.”

Rhode Island is home to two hornets similar in size to the Asian giant hornet: the cicada killer wasps, which dig their nests in sandy or light soil in areas such as athletic fields and playgrounds, and the European hornet, a non-native species that has become naturalized in New England after its arrival here in the 1800s. Like the Asian giant hornet, they are among the largest wasp-like insects in the world.

Tewksbury said that it’s extremely unlikely that the Asian giant hornets in the Pacific Northwest are in Rhode Island or likely will be soon. The concern is that no one knows how the hornets made it to Washington.

“We don’t know the pathway it took to get to Washington, and since we don’t know, it’s difficult to know how to prevent further introductions into North America,” she said.

Although she noted that Rhode Islanders need not be concerned about murder hornets, she advises residents to keep their eyes out for any unusual insect they’ve never seen before, since non-native insects do occasionally arrive in the region.

If you spot an unusual insect, Tewksbury said, take a picture of it and report it to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s invasive species sighting form.

Keep 'em out of the woods, if possible; spend local; heroic New England Council

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It was good to hear that Rhode Island’s state Renewable Energy Fund has announced that solar-energy companies can apply for part of $1 million set aside to encourage the firms to install their projects on contaminated former industrial space instead of in forests (we need those trees to help fight global warming) and other undeveloped space. It’s a small but commendable start.

As I’ve often written, as much as is economically practical, solar companies ought to put their panels at such places as parking lots, rooftops, landfills, sand-and-gravel pits, etc. God knows that as COVID-19 accelerates the destruction of big box retailers and shopping malls surrounded by windswept parking lots there will be more and more space available for solar-energy farms! And the more of them, the less we must depend on fossil fuel from outside New England.

New England Council’s Fine Work

For near-daily updates on New England’s response to the pandemic look at the New England Council’s Web site – newenglandcouncil.com. It’s superb.

Keep Local Stores in Business

I drove by the Walmart in Providence last Tuesday afternoon. It looked as if you’d need at least 40 minutes waiting in line to get into that depressing establishment. I wish that more people would try to keep their money in our area by patronizing locally owned stores instead of the Arkansas-based behemoth, some of whose stores, by the way, have been COVID-19 hotspots, such as one in Worcester.

I suspect that pandemic-caused unemployment is freeing up time for many more people to shop during what had been their workdays at places like Walmart that offer cheap goods. (I’m an Ocean State Job Lot fan myself. Much friendlier and calmer than Walmart, though, of course less stuff.)

Todd McLeish: First wild lizard found in Rhode Island!

Five-lined skink

— Photo by Kris Kelley

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Rhode Island’s herpetological community is bursting with excitement at the discovery of the first confirmed lizard sighting in the state. A five-lined skink (Plestiodon fasciatus) of uncertain origin was found in South County on April 22.

Emilie Holland, an environmental scientist with the Federal Highway Administration and president of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, made the discovery and immediately contacted other National History Survey board members with expertise in identifying lizards.

“I was just poking around when I saw the little guy,” she said. “I thought it was a salamander at first, and I grabbed it really fast. When I opened my hand, I thought it was going to be a mole salamander, but it didn’t move as fast as a mole salamander normally would.”

When University of Rhode Island herpetologist Nancy Karraker received a text and photo of the lizard from Holland, she was in the middle of a virtual meeting.

“My initial reaction was, how quickly can I get out of this meeting and go find Emily to see it,” Karraker said.

The five-lined skink is typically found throughout the Southeast and Midwest, where it’s quite common. Small numbers are also found in the Hudson Valley of New York and into western Connecticut and western Massachusetts. But with the exception of a few unconfirmed observations, they have never been recorded in Rhode Island.

Growing about 6 inches long with distinct brown and cream-colored stripes, the skinks have blue tails as juveniles, and adult males have a reddish throat. The one Holland found was a juvenile.

“The blue tail is a defense mechanism,” said herpetologist Lou Perrotti, director of conservation at Roger Williams Park Zoo. “A predator is going to attack the brightest piece of the animal, and the lizard can drop its tail to get away. It gives them a protection advantage.”

The big question is how it arrived in Rhode Island: Did it arrive naturally on its own, or was it brought to the area by humans, either intentionally or unintentionally? Since it was found near railroad tracks and a lumberyard, many possibilities are being considered.

“Skinks love rocky woodlands where there’s lots of fallen timber,” Perrotti said. “And they love railroad corridors because they’re typically lined with rocks that are great for thermoregulation. Lizards love to climb out on the rocks.

“Was it a stowaway on a train? Was it transported up here in lumber or mulch? We don’t know. We need to find more specimens. Is it possible there’s a population here? Absolutely. But unless you really look for them, they’re really hard to find.”

Scott Buchanan, a herpetologist with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, has contacted a colleague who studies Italian wall lizards that have dispersed up the Northeast rail corridor, but no skinks are known to have been found along the tracks.

Holland hopes it arrived in Rhode Island on its own.

“The child side of my brain says, ‘How cool would that be,’” she said. “But when I stop to think about it, the likelihood is that it somehow got imported here.”

Karraker agreed.

“It’s not a range extension in the sense that it marched its way east to Rhode Island,” she said. “My immediate thought is that it came in somebody’s mulch — or some eggs did — or in a load of wood. There are enough people like me and Lou and Scott and all my students who are constantly running around Rhode Island looking for stuff, rolling over logs. If they were broadly distributed in Rhode Island, we’d know about it.”

Another possibility is that the skink was released by someone who kept it as a pet.

“Pretty much every animal is in the pet trade, but I’ve spent time perusing Craig’s List and I had my students investigating pet shops this semester, and I don’t think this species turned up in anyone’s records,” Karraker said. “They’re not something that tames easily, they’re very sensitive to people being around, and they hide, so they don’t make a good pet.”

Because the skink probably survived here in the winter, it raises additional speculation. David Gregg, executive director of the Natural History Survey, wonders whether the changing climate may have played a role in its survival in the state.

“If further research shows this is a breeding population and not just a lone escapee, then however this particular population of skinks got to Rhode Island, they never could have survived here before but now they can,” he said.

But Karraker noted that some native populations of the skink in New York are nearly as far north as the Adirondack Mountains, where it’s often colder than Rhode Island, so she isn’t convinced climate change has played a role.

“I don’t think it has anything to do with climate,” she said. “Something got moved and the skink was in it, and Rhode Island isn’t a bad place to be. The skink detected that there weren’t any other lizards here to compete with, and it survived.”

The next step for the group of herpetologists is to search the area for additional specimens to determine how large the local population may be. Buchanan will be screening the first specimen for diseases and conducting a genetic analysis to determine from where it originated.

But for now, the skink lives in an aquarium at Karraker’s house, where she is feeding it termites.

“I didn’t want to release it,” she said. “That’s a decision for DEM to make, not me. So I’m just waiting to make the handoff to DEM to take charge and figure out what to do with it.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog

Bad Lyme disease season on its way

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Physical distancing because of COVID-19 has caused cabin fever to reach an all-time high, and people are seeking solace in the great outdoors. And while physical distancing rules still apply outside, the Rhode Island departments of environmental management and health are hoping that people will add another practice to their outdoor excursions: keeping an eye out for ticks.

With a mild winter in which many more ticks than usual likely survived and with more people expected to be outside this year because of the pandemic, 2020 is shaping up to be a bad year for tick bites and the transmission of Lyme and other diseases, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Rhode Island already has the fifth-highest rate of Lyme disease in the country, with 1,111 people diagnosed in 2018.

To help mitigate this problem, DEM and the Department of Health are again promoting the state’s Tick Free Rhode Island campaign.

“At a time when the COVID-19 crisis has forced us into closing state parks and campgrounds, it might seem incongruous to sound the alarm about Lyme disease,” DEM Director Janet Coit said. “Yet, Lyme is a very dangerous disease. So, all of us, whether we’re taking a walk around the block, spending time in our backyards, or going fishing, should do our best to prevent tick bites along with respecting social distancing norms.”

Here are the agencies’ three keys to tick safety:

Repel. Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaves. If you are going to be in a wooded area, walk in the center of the trail to avoid contact with overgrown grass, brush, and leaves at the edges. Wear long pants and long sleeves. Tuck your pants into your socks. Wear light-colored clothes so you can see ticks more easily.

Check. Take a shower after you come back inside from a wooded area. Do a full-body tick check in the mirror; parents should check their kids for ticks and pay special attention to the area in and around the ears, in the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and in their hair. Keep an eye on you pets as well, as they can bring ticks into the house.

Remove. If possible, use tweezers to remove a tick; grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible and pull straight up. If you don’t have tweezers, use a tissue or gloves. Keep an eye on the tick bite spot for signs of rash, or symptoms such as fever and headache.

Most people who get Lyme disease get a rash anywhere on their body, though it may not appear until long after the tick bite. At first, the rash looks like a red circle, but as the circle gets bigger, the middle changes color and seems to clear, so the rash looks like a target bull’s-eye.

Some people don’t get a rash, but feel sick, with headaches, fever, body aches, and fatigue. Over time, they could have swelling and pain in their joints and a stiff, sore neck; or they could become forgetful or have trouble paying attention.

Deer ticks in their developmental progression

Variations on weather themes

Ninigret Pond National Wildlife Refuge, in southern Rhode Island

— Photo by Juliancolton

“Without going against Nature and absolutely defying the seasons, Rhode Island climate has as many variations as the solar system will permit.’’

— From WPA Guide to Rhode Island (1937)

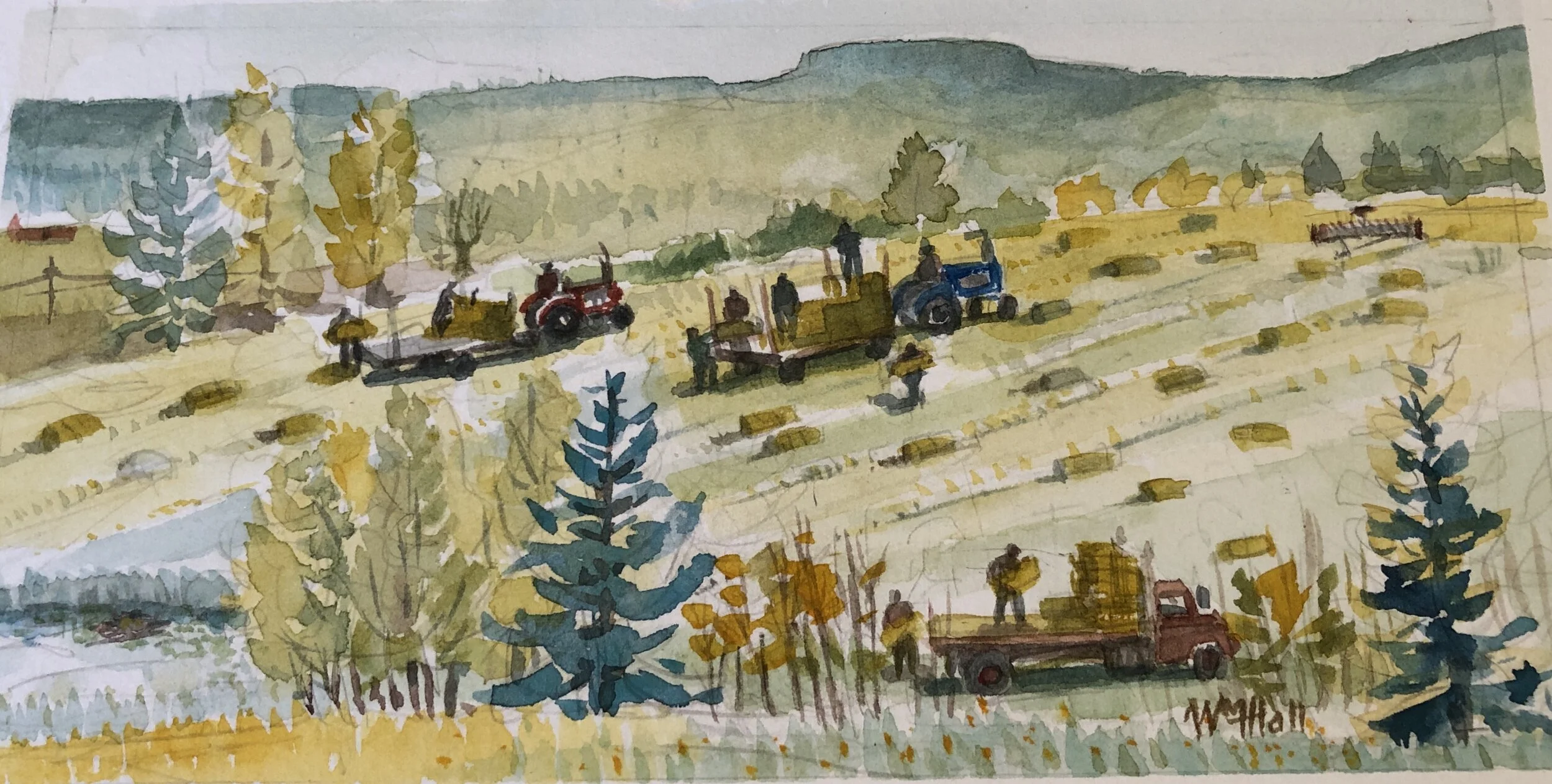

Llewellyn King: To revive America, fix the gig economy and bring back the WPA

McCoy Stadium, in Pawtucket, R.I., was a WPA project….

…and so was this field House and pump station in Scituate, Mass.

The assumption is that we’ll return to work when COVID-19 is contained, or we have adequate vaccines to deal with it.

That assumption is wrong. For many millions, maybe tens of millions, there will be no work to return to.

At root is a belief that the United States -- and much of the world -- will spring back as it did after the 2008 recession: battered but intact.

Fact is, we won’t. Many of today’s jobs won’t exist anymore. Many small businesses will simply, as the old phrase says, go to the wall. And large ones will be forced to downsize, abandoning marginal endeavors.

When we think of small businesses, we think of franchised shops or restaurants and manufacturers that sell through giants like Amazon and Walmart. But the shrinkage certainly goes further and deeper.

Retailing across the board is in trouble, from the big-box chains to the mom-and-pop clothing stores. The big retailers were reeling well before the coronavirus crisis. Neiman Marcus, an iconic luxury retailer, has filed for bankruptcy. All are hurt, some so much so – especially malls -- that they may be looking to a bleak future.

The supply chain will drive some companies out of business. Small manufacturers may find that their raw material suppliers are no longer there or that the supply chain has collapsed – for example, the clothing manufacturer who can’t get cloth from Italy, dye from Japan or fastenings from China. Over the years, supply chains have become notoriously tight as efficiency has become a business byword.

Some will adapt, some won’t be able to do so. A record 26.5 million Americans have sought unemployment benefits over the past five weeks. Official unemployment numbers have always been on the low side as there’s no way of counting those who’ve given up, those who work in the gray economy, and those who for other reasons, like fear of officialdom or lack of computer skills, haven’t applied for unemployment benefits.

To deal with this situation the government will have to be nimble and imaginative. The idea that the economy will bounce back in a classic V-shape is likely to prove illusory.

The natural response will be for more government handouts. But that won’t solve the systemic problem and will introduce a problem of its own: The dole will build up dependence.

I see two solutions, both of which will require political imagination and fortitude. First, boost the gig economy (contract and casual work) and provide gig workers with the basic structure that formal workers enjoy: Social Security, collective health insurance, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation. The gig worker, whether cutting lawns, creating Web sites, or driving for a ride-sharing company, should be brought into the established employment fold; they’re employed but differently.

Second, a new Works Progress Administration (WPA) should be created using government and private funding and concentrating on the infrastructure. The WPA, created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, ended up employing 8.5 million Americans, out of a total population of 127.3 million, in projects ranging from mural painting to bridge building. Its impact for good was enormous. It fed the hungry with dignity, not the soup kitchen and bread line, and gave America a gift that has kept on giving to this day.

Jarrod Hazelton, a Rhode Island-based economist who’s researched the WPA, says the agency gave us 280,000 miles of repaired roads, almost 30,000 new and repaired bridges, 600 new airports, thousands of new schools, innumerable arts programs, and 24 million planted trees. It also enabled workers to acquire skills and escape the dead-end jobs they’d lost. It was one of the most successful public-private programs in all of history.

As the sea levels rise and the climate deteriorates, we’ll need a WPA, tied in with the Army Corps of Engineers, to help the nation flourish in the decades of challenge ahead. The original was created by FDR with a simple executive order.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: On the 50th Earth Day, grounds for hope amidst the mess

President Nixon and his wife, Patricia, plant a tree on the White House grounds to mark the first Earth Day, in 1970. The Republican Party had many environmentalists back then. In the same year, Nixon signed into law the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

On the face of it, there isn’t much to celebrate on April 22, the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. The oceans are choked with invisible carbon and plastic which is very visible when it washes up on beaches and fatal when ingested by animals, from whales to seagulls.

On land, as a run-up to Earth Day, Mississippi recorded its widest tornado – two miles across -- since measurements were first taken, and the European Copernicus Institute said an enormous hole in the ozone over the Arctic has opened after a decade of stability.

But perversely, there’s some exceptionally good news. Because of the cessation of so much activity, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the air has cleared dramatically; cities around the world, including Mumbai and Los Angeles, are smog-free. Also, the murk in the waters of Venice’s canals and the waves from motorboats are gone, revealing fish and plants in the clear Adriatic water.

Jan Vrins, global energy leader at Guidehouse, the world-circling consultancy, was so excited by the clearing that he posted and tweeted a picture taken from a town in the Punjab where Himalayan peaks are visible for the first time in 30 years.

The message here is very hopeful: With some moderation in human activity, we can save the environment and ourselves.

The sense of gloom and hopelessness that has attended a litany of environmental woes needn’t be inevitable. Mitigating conduct in industry and, particularly in the energy sector, can have a huge impact quickly; transportation will take longer. Vrins says the electric utility industry -- a source of so much carbon -- is now almost entirely engaged in the fight against global warming. Just five years ago, he says, they weren’t all fully committed to it.

Another Guidehouse consultant, Matthew Banks, is working with large industrial and consumer companies on reducing the impact of packaging as well as the energy content of consumer goods. Among his clients are Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Johnson & Johnson. The latter, he says, has been working to reduce product footprint since 1995.

“This is an important moment in time,” Banks says. “Folks have talked about this as being The Great Pause and I think on this Earth Day, we need to think about how that bounce back or rebound from the Great Pause can be done in a way that responds to the climate crisis.”

I was on hand covering the first Earth Day, created by Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson, a Democrat, and its national organizer, Denis Hayes. It came as a follow-on to the environmental conscientiousness which arose from the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring, in 1962. That dealt with the devastating impact of the insecticide DDT.

Richard Nixon gave the environmental movement the hugely important National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. With that legislation, and the support of people like Nelson, the environmental movement was off and running – and sadly, sometimes running off the rails.

One of the environmentalists’ targets was nuclear power. If nuclear was bad, then something else had to be good. At that time, wind turbines -- like those we see everywhere nowadays -- hadn’t been perfected. Early solar power was to be produced with mirrors concentrating sunlight on towers. That concept has had to be largely abandoned as solar-electric cells have improved and the cost has skidded down.

But in the 1970s, there was reliable coal, lots of it. As the founder and editor in chief of The Energy Daily, I sat through many a meeting where environmentalists proposed that coal burned in fluidized-bed boilers should provide future electricity. Natural gas and oil were regarded as, according to the inchoate Department of Energy, depleted resources. Coal was the future, especially after the energy crisis broke with the Arab oil embargo in the fall of 1973.

Now there is a new sophistication. It was growing before the coronavirus pandemic laid the world low, but it has gained in strength. As Guidehouse’s Vrins says, “We still have climate change as a ‘gray rhino’, a big threat to our society and the world at large. I hope that utilities and all their stakeholders will increase their urgency of addressing that big threat which is still ahead of us.”

Happy birthday Earth Day — and many more to come.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

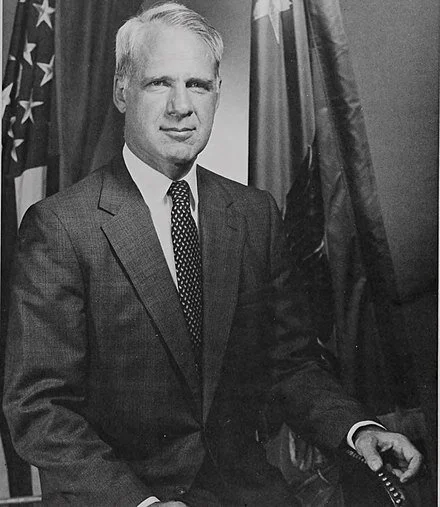

Llewellyn King: Lessons from the Energy Crisis to address the COVID-19 challenge

James Schlesinger (1929-2014), the first U.S. energy secretary and a leader in confronting the Energy Crisis of the 1970s.