Better than Nature

“They have been with us a long time.

They will outlast the elms…

The Nature of our construction is in every way

A better fit than the Nature it displaces.’’

— From “Telephone Poles,’’ by John Updike (1932-2009), for decades America’s leading man of letters. He spent most of his adult life on Massachusetts’s North Shore.

h

Waiting for the ‘salt wash’

Bass Harbor (Maine) Lighthouse

— Photo by Chandra Hari

“Where shell and weed

Wait upon the salt wash of the sea,

And the clear nights of stars

Swing their lights westward

To set behind the land…’’

From “Night,’’ by Louise Bogan (1897-1970), a native of Livermore Falls, Maine.

Downtown Livermore Falls, Maine, in 1909.

An edited version of a paragraph from Wikipedia:

“In the early 19th Century, the town’s region was predominantly farmland, with apple orchards and dairies supplying markets at Boston and Portland, and it was noted for fine cattle. As the century progressed, gristmills, sawmills, logging and lumber became important industries, operated by water power from falls that drop 14 feet. With the arrival of the Androscoggin Railroad, in 1852, Livermore Falls developed as a small mill town. Shoe factories and paper mills were established. . In 1897, the Third Bridge was built across the Androscoggin River. It measured 800 feet in length, at that time the longest single-span bridge in New England.’’

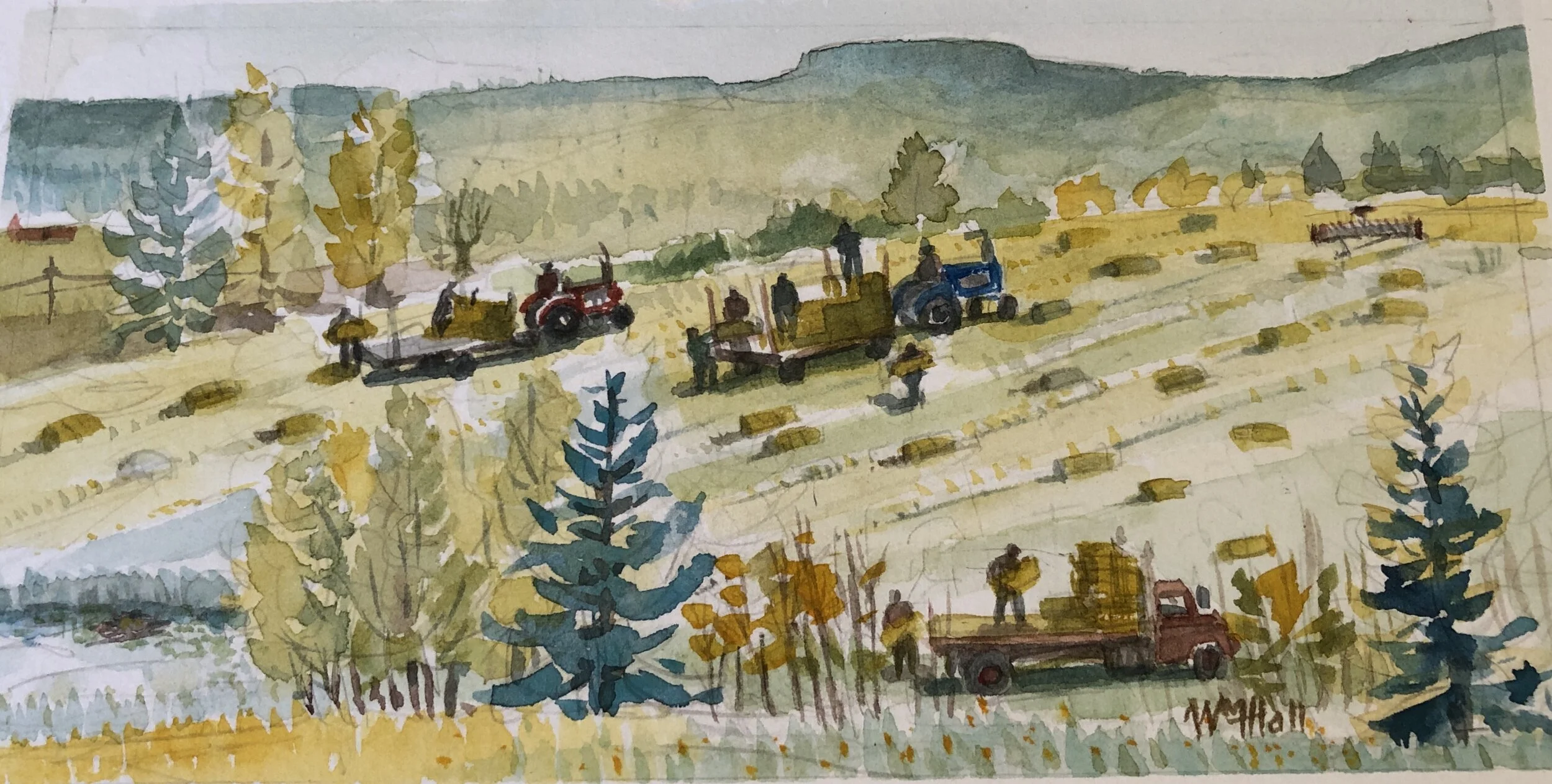

Bill Hall: The big gamble of 'early haying' in Vermont

“Harvesting the Hay Crop on Deadline’’

— Watercolor by Bill Hall

In late May it could get hot in Vermont’s Connecticut River “Upper Valley’’. You shifted slowly from here to there, but you had to move. If you didn’t you’d swear you would suffocate. You weren’t avoiding the oppressive heat as much as you were looking for some air to breath. Shade didn’t help much; it only served to dull the searing brightness. The heat was just there. If you were a farmer you had to get used to it, and get things done anyway. One of those things might have been to get in the early (season’s first) crop of hay: “early hay”.

In that sudden sweltering heat, you had to decide:

“Hay or no hay”?

Once you decided to hay, you had to do it fast. After the brutality of winter and the torrents of “mud season,” after the financial reality of dairy farming sank in once again, you had to get moving. You might put off the question of buying new equipment by fixing the old. Or should you pay down your loan?

Farmers in the Connecticut River Valley had to weigh the costs and rewards of throwing the dice once again. Would they risk an early haying or would they fold and walk away? That was the big gamble.

Early hay or “spring mow” sounds simple enough to a non-farmer. The common question asked, “Is it possible?” The correct answer is, “No, in most cases,” due to weather, which is always uncertain in northern New England. “Then, is it necessary,” you might ask?

In some professions, such as insurance, determining possibilities is a scientific matter, but in farming it’s just called “gambling”. My street-smart father called it “ The Farmers’ Hat-Trick”. He explained it to my brother and me as he shifted three dried butternut half-shells around on the kitchen table in short quick movements, one shell concealing a dried pea seed. You know this game. Which shell hides the pea? This was to demonstrate how, by a game he called “slight-of-hand,” farmers plotted to sneak a full barn of early hay right out from under the nose of a vengeful God.

My brother and I did not realize we were also getting a lesson about my father’s religious beliefs, seasoned by his ironic sense of humor. He was a traveling farm-equipment salesman who served a big territory. He understood farming, but elected to travel in a wider circle of go-getter types. He was also kind and sympathetic. By the end of the lesson he had impressed upon us how daring farmers were for trying to beat the heavy odds against succeeding at a harvest of early hay while it was still mud season. Dad called a career that required dealing with weather “a fool’s guess”. We also learned why we were lucky to be able to watch and understand this unfolding lesson where we could see it, in our own pastures. But we were safe from the financial challenges. My father traded the hay to our neighbors, the Vaughans, just to get our fields hayed, addressing the need to keep out brambles and weeds that cows shouldn’t eat, and to provide us with enough hay for our modest needs, which were for bedding, fodder and scratch hay for my grandfather’s turkeys and chickens (and their eggs)

Quirky local weather is king

Vermont has many microclimates, in part because of its geological history. Small farmers work every inch of that glorious land from the highest pastures of the Green Mountains to the floor of the Connecticut River Valley. Our 50-acre farm lay like a door-mat on the fertile plain of that valley, but the rush to harvest an early hay, or the decision not to attempt it, was happening everywhere in our little state, and all at once.

We would get news from Father’s weekly travels about the haying elsewhere. “They’re still not mowing in the Champlain Valley” maybe he’d report. He had seen bales in a high pasture over in the Vershire Hills, just west of us, but they were covered with snow and so on. Our total focus was on our two flat 25-acre fields, one on each side of our farm house. We knew from the farm kids at school that other farmers were ramping up to mow, rake, flip, dry and bale new hay everywhere around us, as soon as the weather permitted.

My father joked that if God controlled the weather then he was the one who needed to be appeased, fooled, dazzled or distracted. “He can be a practical joker at times,” he said, winking. The question was, if a farmer was going to sneak in such a neat stunt as an early hay harvest shouldn’t the farmer be very careful? If God knew, might he put obstacles in the farmers’ way? As our minister said, “To test him, to test his devotion”? It seemed like there was a, “side bet” between our dad and “Our Father”.

The tension was growing.

It was pre-spring. The days alternated between snow and mud. Most farmers were gun-shy and dazed by the deep dark winter they had just endured. Already skeptical about the benevolence of their God, a farmer could get discouraged from being house-bound and barricaded in their dark barns all winter dealing with rodents, frozen pipes and coughing cows. When the farmers returned to their kitchens, wives were waiting with “payable notices” illustrating the folly of a farming life. They felt vulnerable. The prospect of an early haying seemed further away than ever, but then it did every year.

Mud season was next. It held hands with winter. Those two soulless bullies worked together to test farmers’ resolve. Farmers felt helpless in their grip, and the sun seemed in cahoots with those darker elements of life because it offered only a few short winks in early May. “Was this spring”, they asked? It sleeted in April and froze tight every night for days sometimes, and maybe served up a blizzard for breakfast. Levity and faith were long gone by the time that the spring mud started to shift consistency from stinking brown glue in the barnyard to something more solid. But the fields were still soaking wet.

Wet fields? Were they the death warrant for early hay crops? A wet field normally meant one inaccessible to heavy farm equipment, and therefore useless until dry, but with a little luck and intense sunshine the ground might give rise to the green gold of the grass seeds within. If they could just get enough sunshine those seeds would explode to become a free bonanza of green early hay, but only in a field dry enough to work in. A windfall crop of sweet green hay would feed a farmer’s cows until the second haying season, in July, and would ensure that no hay need be purchased in the upcoming calendar year.

In Vermont the “early hay’’ was originally called “early mow’’. It was not baled. Teams of as few as two and sometimes as many as six work horses or mules hauled a man around who worked with horses, a “teamster,” upon a wood-frame contraption that combined pre- and post-industrial wood and metal embellishments. The wooden frame was as elegant as any stage coach and the iron parts included shiny as well as rusty parts, such as shearing bars, worm gears and iron seats.

The early mowers worked mechanically like a thousand men with sickles to lay the new grass low. Horse-drawn mechanical flippers or men with wooden rakes turned the grass over, on the same day it was mowed. This, done properly, dried out the hay enough to be “put-away”. Horse-drawn wagons were filled to the tops with loosely piled hay, which was lifted up using mechanical pulleys to be placed drooping over drying beams in the tops of barns, where the hay’s sweet perfume cleansed the stale air from the winter just passed. It was said such a barn was made “happy” by new hay. Cows’ eyes bulged upward as they bellowed in the milking level below as if trying to see through the floor above to the new hay they longed for.

This horse-powered equipment provided an advantage in its day. It could be operated in soaked fields before mud season had subsided, allowing access to wet fields without damaging them, as the weight of modern tractors, balers and trucks would have. Waiting for the proper surface conditions in those fields is what made the modern early hay process such a crap shoot .

Hay could be harvested when it was ready without farmers having to wait for equipment and manpower to converge on a field en masse. It could be gradually harvested more times during the season as it grew. The process was more controllable and flexible.

Above all it was a soulful process for both man and beast. There are still a few Vermont farmers who maintain horse and mule teams and the revered equipment that goes with farms with horses. Admiring them are amateur teamsters, purists, history buffs and people who still prefer the music of men’s voices coaxing animals forward to the sound of diesel tractors and metal balers. In some areas, drivers still park their cars along dirt roads in silent observance of this sacred event. But farming with horses has come to be seen as too slow and out of step with the times.

For the modern farmer and his quest for that early hay, he could only hope that his organizational skills and gambling spirit would see him through. These days, there are detailed weather predictions, radar and and satellite maps to show the regional picture, but it’s his personal experience and knowledge of his region that best tell him when to cut his hay. In our case in Thetford everything was temporary and nothing was as it seemed. It’s complicated. It tests your commitment. It leads you on. It dares you.

Is there enough time?

The fog over the valley floor and the heavy moisture it brings almost every day will dissipate by 9 a.m. if the sun is shining. Then will come a breeze. The heat of the sun on the valley floor will cause up-drafts, which will flow west through the hills of Vermont or east toward the hills on the New Hampshire side. In between is some of the most fertile soil in New England. The question is, can you wait for the sun to do its work and can you commit manpower and other resources enough to get the job done in time? If the farmer has his own hay-processing equipment, no matter how advanced, from cutting to storage, he’s in a stronger position; no one can let him down if he does it himself.

When it came to our two fields we aced it, but it was close. When the weather report said “no way” we had it hayed anyway. The Vaughan family, our aforementioned neighbors, made it happen. They arrived en masse when they saw that the rain that had been predicted for that morning did not fall. Sunny skies were forecast. The Vaughans made a commitment to cut both of our fields that day. They’d flip and rake them alternately and move from one field to another with Big-Red, the baler. We could see that there was still standing water near the fire pond (a source of water to put out barn fires) behind the barn. That area would be dry by midsummer and would have to wait.

The intense ‘baling day’

The Vaughans used two cutting tractors to get the hay down fast; both were working simultaneously. The flipper and rake alternated between the two fields.

Then came “baling day”. One year, the sky was overcast and the forecast was for rain by noon. As we had to wait for the morning dew to dry off, we were worried, but committed. The Vaughan family patriarch was unconcerned. Robert Vaughan Sr., who looked like someone in a Vermeer painting, decided that the hay would get baled and then stacked in his big barn by the end of that day, and that was that. Even if some of the last bales got a little wet, “We’re doing it”.

Just in case, he directed a couple of his five sons to go to the Vaughans’ barn and set up drying racks, where they’d be exposed to wind from the two enormous fans they had just installed. These fans were six feet wide and made the ends of the barn resemble an aircraft-test wind tunnel. This flow would ensure that our hay would retain its dryness in case the rain fell on the last day before we got the hay stacked. Mr. Vaughan wanted the new hay treated gingerly because it had a high alfalfa content and a limited tolerance to too much jostling.

Unlike with August haying, the alfalfa would stay in this new hay. When dry that early alfalfa would resemble flaked butterfly wings and if handled roughly would flutter down from the bottoms of the bales. This essence of the “first cut” must be maintained, otherwise why bother? Dryness was dicey for other reasons. The “good moisture” content was tricky to maintain, and “bad or deep moisture” would cause rot that would spread to hay around it.

Every bale in that bountiful harvest was loaded and trucked to the barn. The last three truckloads were stacked with the help of headlights of the other trucks and tractor. If we were lucky, the rain that might have been predicted held off until the last truck was mostly filled. A large tarp was fixed over the top and flapped wildly as we drove to the barn, where it was unloaded in the big alley in the center. Everyone helped and so it took only a few minutes. Then the big fans were turned on for the night. The sound that followed the throwing of the main switch gave the event a science-fiction feel. The fans chilled us as the breeze dried our sweaty, itchy backs. We would all seek relief lying in front of those fans in the sweltering days to come.

My brother and I always remember those times when the early hay was brought in.

Bill Hall is an artist based in Florida and Rhode Island. Hit this link.

Thetford, Vt. in 1912

— Photo by Mike Kirby

Linda Gasparello: Ice cream anti-socials in America's angry COVID-19 summer

— Photo by Xnatedawgx

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

You’ve heard of an ice cream social — an event in a home or elsewhere, using ice cream as its central theme, dating back to the 18th Century in America.

Thomas Jefferson became the first president to serve ice cream at the White House, in 1802. An epicure, Jefferson had his own personal recipe for vanilla ice cream.

Now, in the time of COVID-19 and President Trump, there are ice cream anti-socials.

These events feature meltdowns by customers in ice cream shops over having to wear face masks, having to stand six feet apart waiting in line — or even having fewer flavor choices on the menu. No Peanut Butter Caramel Cookie Dough? What’s America coming to? As Trump might tweet, “So terrible!”

The latest reported ice cream anti-socials in New England happened at Brickley’s, an ice cream shop with locations in Narragansett and Wakefield, R.I. In early May, one at Polar Cave Ice Cream Parlour in Mashpee, Mass., described by its owner as “insane,” made national news.

The Brickley’s events mirrored the one in Cape Cod in the rude, crude and socially unacceptable behavior of some customers.

Steve Brophy, who owns and operates Brickley’s with his wife, said in a June 22 Facebook post, “Over the last two weeks at both our locations, we have experienced on multiple occasions customers who will not wear their mask (asking us to show them the law) or are angry they can’t get exactly what they want due to the reduced menu. I, personally, had one man yell at me, ‘What’s your f—ing problem?’ because I had told him he needed to move his car which was blocking traffic. A few more expletives hurled toward me and I (for the first time in 26 years) told him to take his business elsewhere.

“Some of these customers are being verbally abusive to our young staff. That is unacceptable and will not be tolerated. I cannot ask our high school and college (age) staff to police the behavior of some who choose to ignore our rules.”

As if what these boors said wasn’t enough, Brophy also said in the post: “Another customer, who could not get exactly what he wanted, told our staff member, ‘You are babies. Are you going to let Gina hold your hand all summer?’ and ‘I hope you go out of f—ing business.’ ”

By “Gina,” the customer was referring to Gina Raimondo, Rhode Island’s Democratic governor, who issued an order on May 8 requiring all residents over the age of two to wear face coverings or masks while in public settings, whether indoors or outdoors. It’s the law.

The simple pleasure of going out for an ice cream, an all-American summer activity, is being taken away from adults and children, who’ve been holed up during the pandemic, by foul-mouthed people, partisan or not.

If they want to signal their vileness, maybe an enterprising one of their lot should open an ice cream shop: no masks, flavors like COVID-19 Cookies and Cream, and all abuse-spewing patrons welcome.

These ice cream anti-social events are likely to happen all over the country, especially as the summer and the 2020 presidential campaigns heat up.

July is National Ice Cream Month. I propose, a chilling out, a time for Americans to reflect on the nice tradition of ice cream socials and going out for an ice cream.

Don’t be a jerk. Stop hurling expletives and politics at shop owners and staff, the latter who include high school and college students who are trying to make a buck by scooping your ice cream, making your life a little sweeter.

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Her e-mail is lgasparello@kingpublishing.com.

Copyright © 2020 White House Chronicle, All rights reserved.

Keep updated on the White House Chronicle's latest hot-button issues at whchronicle.com

Better class of people

“I am obliged to confess I should sooner live in a society governed by the first 2,000 names in the Boston telephone directory than in a society governed by the 2,000 faculty members of Harvard University.

— William F. Buckley Jr. (1925-2008), writer, TV personality and conservative public intellectual.

The first telephone directory, printed in New Haven in November 1878

'I can't go on:' I'll go on'

“Beckett's Maze,’’ by Robin Crocker, at the Jamestown (R.I.) Arts Center. This is an in-progress photo.

The center’s parking lot is the site of this installation by Rhode Island-based artist Crocker, who has modeled the maze after the ancient labyrinth found in Chartres Cathedral, circa 1200 CE. She says she was influenced by Samuel Beckett's novel The Unnameable, quoted throughout the installation. Viewers will find Beckett’s words "You must go on" at the entrance of the maze, and his "I can't go on" and "I'll go on" stenciled on gold medallions alternating every six feet (social distancing!).

"In the midst of this global pandemic, faced with deeply rooted social injustice and political divide, now is a crucial time to contemplate our role, our impact, as part of this whole," she said. "A journey through Beckett's Maze offers an opportunity for this much needed introspection."

The arts center says she “drew on musings on consciousness to create an experience that mimics the journey through life, marked in equal parts by suffering (‘I can't go on’) and joy (‘I'll go on’).’’ The installation will end once the paint fades; it won't be repainted.

Secret anguish

Gardiner, Maine’s long-gone R. P. Hazzard Co. shoe factory in 1915

Whenever Richard Cory went down town,

We people on the pavement looked at him:

He was a gentleman from sole to crown,

Clean favored, and imperially slim.

And he was always quietly arrayed,

And he was always human when he talked;

But still he fluttered pulses when he said,

"Good-morning," and he glittered when he walked.

And he was rich—yes, richer than a king—

And admirably schooled in every grace:

In fine, we thought that he was everything

To make us wish that we were in his place.

So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat, and cursed the bread;

And Richard Cory, one calm summer night,

Went home and put a bullet through his head.

— “Richard Cory,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935), who set many of his poems in the fictional community of Tilbury Town, modeled after Gardiner, Maine, where Robinson grew up.

In sleepy downtown Gardiner now

What July is

“July is hot afternoons and sultry nights and mornings when it’s joy just to be alive. July is a picnic and a red canoe and a sunburned neck and a softball game and ice tinkling in a tall glass. July is a blind date with summer. ‘‘

— Hal Borland (1900-77), American writer and naturalist and long-time resident of Salisbury, Conn., in the foothills of the Berkshires, which he often wrote about.

— Photo by Mary Kane

Llewellyn King: The virus and the debt bomb

We are in the shadow of an economic collapse of 1930s proportions. That is the awful reality of the current and relentless surge in COVID-19 infections. What looked bad a few weeks ago now looks worse.

The first horror is the coronavirus itself. The second is the devastated economic and social order it will leave behind: a landscape where the structures of society are leveled and will have to be replaced not by the old, broken structures but by new ones.

The economy won’t come roaring back in a classic V, as so many hope and even believe.

Parts of the economy are undergoing massive leveling of near-biblical proportions. Tens of millions of us are raring to get back to work, to resume where we left off. But for many, there will be nowhere to return to: They will be economic refugees, contemplating a swath of destruction where their jobs used to be. They’ll find there is no there there.

Jobs in retailing, restaurants, bars, hotels, cinemas, sports facilities, and travel have already vaporized. Behind those subtractions from the economy are their supply chains. Visible jobs lost are just the beginning. When economic collapse begins, it spreads as devastatingly as COVID-19 in a crowded barroom.

There is brutal irony when, after the virus, the second subject on the national agenda is the plight of minorities. Sadly, they are overrepresented among the workers at the low end of the economic food chain. It is those who make the minimum wage or just above, those who live off tips, day work, commissions, pick up assignments -- the whole shaky lattice that makes up the employment pyramid -- who are set to be hurting badly when unemployment runs out.

Every damaged industry, like retail, has its collateral damage. Close a mall and the hurt spreads after the clerks and warehouse workers are gone, from cleaners to building maintenance workers, to supply chain workers, to advertising professionals and the newspapers where those ads might have appeared. Like the coronavirus itself, economic contagion spreads wide and fast.

Politicians and social engineers keep trying to promote the working class to the middle class, but they remain at the bottom -- those who feel every bump in the economic road.

Across the nation, a debt bomb is about to explode with huge consequences for those who are now or about to be jobless -- and by extension the whole economy. Delayed rents are going to come due with a concurrent wave of evictions affecting millions. Credit cards -- the modern slavery for those with little money -- must be paid, except they won’t. At almost 30 percent interest, which is what many are paying, the debt will overwhelm the users. In time, as accounts fall into arrears and payments cease, it will begin to drag down the issuers.

An incendiary component of the debt bomb is health care. People rushed to hospitals are going to have medical bills in the tens of thousands of dollars. They won’t be able to pay. No money, no pay, no choice. If the pandemic goes on long enough, the insurers, for those who are insured, will begin to hurt.

But mostly, it will be the hospitals that will go after the patients for payment because they’ll have no choice. Real inability to pay is the fuse that will light the debt bomb. Multiply this by those who need other health care and are not insured.

Most thinking in the political class has revolved around an expectation that come the fall, there will be a vaccine that will be available and affordable by all and it will turn night into day, ending the horror. That isn’t assured. Already, to be sure, we are finding therapies for use in infected patients, the steroid Dexamethasone, for example, and other off-label uses of existing drugs. But that doesn’t immunize the population, and whether immunization is possible and how fast it will come isn’t known.

What is known is the unfolding economic catastrophe for tens of millions of Americans and their possibly permanent loss of jobs.

When Europe lay in ruins after World War II, the United States stepped in with the Marshall Plan and wrought an economic resurrection. A Marshall Plan for America? I think so. The need will be very great.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Washington, D.C., and Rhode Island.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

New England's only NASCAR site to reopen

At the New Hampshire Motor Speedway

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“With most major sports leagues having had their seasons curtailed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the NASCAR circuit will be returning to New Hampshire Motor Speedway in Loudon, N.H., {in Lakes Region} this summer. Governor Chris Sununu recently gave the “green light” to allow race fans at New England’s only NASCAR site with proper precautions to ensure fans maintain social distancing requirements among other health considerations. The racing world’s attention will turn to New Hampshire for the race on Aug. 2. Read more at the New Hampshire Motor Speedway.’’

Chris Powell: Hartford mayor confronts the mob while legislators pander

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Maybe black lives matter a little more now, but mainly, it seems, when they are taken by white cops. When they are taken by anyone else, that seems to be nobody's business.

For where are the protests of the murder of New Haven high school basketball star Kiana Brown, 19, shot to death a week ago as she slept at her home, apparently killed by a stray bullet fired from outside? And who is protesting the fatal shooting of Luis Nelson Perez, 27, on a New Haven street a few days later?

New Haven may be the most indignant city in the world but it gives its own social disintegration a pass. Indeed, the social disintegration underlying most wrongful deaths in Connecticut gets a pass not only in New Haven but throughout the state amid the clamor to end racism and defund the police.

At least Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin last weekend became the first elected official in Connecticut to talk back to the mob. Hundreds of protesters descended on his home, demanding that he take their wrath out on the city's cops. The mayor tried to explain why law enforcement should not be abolished but he was interrupted, jeered, and largely drowned out. The protesters wanted only to intimidate.

But Bronin's plan to create a civilian agency to respond to seemingly noncriminal incidents such as mental breakdowns and drug overdoses, eliminating police response, won't appease the mob and is not realistic anyway. For the mentally ill and the druggies are not always harmless. They quickly can become violent.

Does the mayor not remember the nearly fatal stabbing of a Hartford police officer two years ago as she responded to a commotion caused by a mentally ill woman resisting eviction from her apartment? Any social worker or therapist responding to the incident would have faced the same threat. Police already try to reduce tensions at incident scenes. Their authority to use force is more a help than a handicap. Social workers and therapists get less respect.

While Bronin got the mob treatment, Connecticut's state legislators are being let off too easily -- and not just by the protesters to whom they have been pandering. Nobody is asking legislators who was in charge while Connecticut's police became so unaccountable and social disintegration worsened, especially in the cities.

Last week state Senate President Pro Tem Martin M. Looney, D-New Haven, at least was asked if legislators would do anything about the provision in the state police union contract that allows concealment of brutality complaints. Looney replied that the current contract can't be revised but the law might be changed someday to forbid similar provisions in future contracts.

This was a dishonest dodge. For the General Assembly and Governor Lamont could nullify the secrecy provision by repealing the law authorizing state employee union contracts to supersede the open-government law, as the state police contract does. Then the contract wouldn't have to be changed. The legislature and governor also could repeal collective bargaining for the state police. Such a threat might induce the union to concede the secrecy provision immediately.

No one asked Looney how the state police contract provision came about and how it so easily got past the governor and those legislators who now are insisting that black lives matter. Just whom were the governor and legislators serving when they agreed to conceal complaints of police brutality? Not the public.

Feigning impotence, Looney and his colleagues still think that the contentment of government employees matters more than black lives.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Mayor Luke Bronin

Explosive evenings

M-80

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Residents of Providence are being increasingly disturbed by fireworks and firecrackers being set off for hours every night, especially in poorer neighborhoods. Lots of these are being illegally used, since in Rhode Island only ground fireworks and sparklers can be legally ignited – in other words, quiet displays -- with firecrackers, rockets and mortars or other devices that launch projectiles banned, except, I assume, for professionally run public fireworks displays that we used to enjoy on special occasions, especially The Fourth and New Year’s Eve.

The racket, injuries and fire threat from illegally used fireworks is one of those quality-of-life issues, like graffiti, that can drive people away from a city. The police must crack down hard. And the explosives are hurting the sleep we need, especially in these tenser-than-usual times. If some folks see the fireworks as an expression of personal or political liberation many more see them as reminders of entrapment in an urban dystopia.

Knock it off.

Ah, if only people were as interested in reading the Declaration of Independence as in making a lot of noise.

The fireworks frenzy is happening in other cities, too. Please hit this link.

The year-round fireworks dilutes the excitement that we used to feel as we approached the public celebrations of the Glorious Fourth of July, which I suppose won’t happen this year in most places. When I was a kid we lived on the coast and so most of the fireworks spectacles we enjoyed were on beaches. But we also, probably illegally, had our private shows, mostly involving devices such as M-80s, cherry bombs and Roman candles, in backyards – with the nearby thick woods muffling the noise a bit. But that was only on the Fourth, when the local cops, who seemed to know everyone in town, would look the other way.

My father would stock up several years worth of fireworks in Southern states, where laws were lax. (Now the laws are very lax in New Hampshire — Live Free and Blow Off Your Hand.

Then there was the little cannon he set off every year on the Fourth. We had a loud old time for several hours.

A few boys would light and throw M-80s and cherry bombs at each other (but only on The Fourth!), displaying the same sort of idiocy as in the BB-gun wars they had through the year, in which it was possible to lose an eye or two. Cheap thrills indeed!

Early morning gull

See www.nivaartwork.com and galateafineartcom

“Lobster Co-Op in Stonington {Maine} ‘‘ (oil) , by Niva Shrestha in Galatea Fine Art’s online gallery. This text ran with it:

“The first sound one hears is the gull calling the morning. It has been a long work day, and it seemingly was never over. The dawn calls to duty, to awaken todoing-ness, sleep and rest a dim memory. But the day is a blessing, a legacy to generations past and future.’’

Rocket science

“Freedom is a rocket,

isn’t it, bursting

orgasmically over

parkloads of hot

dog devouring

human beings….’’

— From “Fourth of July,’’ by John Brehm

From away

“I find it funny how people from Boston and New York hate each other because of pro teams. But, like, everyone on the Red Sox is a random millionaire athlete from somewhere else.’’

— Julian Casablancas, musician

Invasive little pet turtles

Red-Eared Sliders

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

They are the most popular pet turtle in the United States and available at pet shops around the world, but because Red-Eared Sliders live for about 30 years, they are often released where they don’t belong after pet owners tire of them. As a result, they are considered one of the world’s 100 most invasive species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Southern New England isn’t immune to the problems they cause.

“I hear the same story again and again,” said herpetologist Scott Buchanan, a wildlife biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. “‘We bought this turtle for a few dollars when Johnny was 8, he had it for 10 years and now he’s going to college, so we put it in a local pond.’ That’s been the story for hundreds and thousands of kids in recent decades.”

Red-Eared Sliders are native to the Southeast and south-central United States and northern Mexico, where they are commonly found in a variety of ponds and wetlands. Buchanan said they are tolerant of human disturbance and tolerant of pollution, and they are dietary generalists, so they can live almost anywhere. And they do. They breed throughout much of Australia as a result of pets being released, and in Southeast Asia they are raised as an agricultural crop and have displaced numerous native species. In the Northeast, they live in the same habitat as Eastern Painted Turtles, one of the area’s most common species, but they grow about 50 percent larger. Numerous studies suggest that sliders outcompete native turtles for food, nesting, and basking sites.

Despite concerns about their impact on native turtle populations, red-eared sliders are still legal to buy in Rhode Island and most of the United States, though Buchanan said that in the Ocean State they may only be sold by a licensed pet dealer and can’t be transported across state lines. Those who buy a slider must keep it indoors and must never release it into the wild, including into a private pond.

“But people often aren’t aware of the regulations, or they don’t bother to look at them, or they just don’t follow them,” Buchanan said. “We see lots of evidence of sliders, especially in parts of the state where there are lots of people. The abundance of Red-Eared Sliders in Rhode Island is tied to human population density, which means mostly Providence and the surrounding communities. But I’ve also found them in Newport and Narragansett and elsewhere.”

Sliders are especially common in the ponds at Roger Williams Park, in Providence, and in the Blackstone River.

While conducting research for his doctorate at the University of Rhode Island from 2013 to 2016, Buchanan surveyed ponds throughout the state looking for spotted turtles, a species of conservation concern in the region. During his research, he also documented other turtle species, including many red-eared sliders.

“The good news was that while spotted turtles can occupy the same habitat as red-eared sliders, I found a greater probability of occupancy by spotted turtles at the opposite end of the human density spectrum as I found sliders,” he said. “Spotted turtles tend to occur where human population density is low, so at least at this moment in time, we would not expect red-eared sliders to be directly competing with populations of spotted turtles.”

Nonetheless, Buchanan advocates what he calls a “containment policy” to keep the sliders from expanding their range in the state.

“It’s mostly about public education,” he said. “We want to make sure people know not to release them in their local wetlands. If we found sliders in an important conservation area — Arcadia, for example — we might consider removing them, though we’re not doing that now.

“They’re well-established in Rhode Island now, so the thought of eradicating them does not seem like a feasible management solution. We just have to live with them, but we also have to try to minimize their spread and colonization of new wetlands.”

No other non-native turtle from the pet trade besides the Red-Eared Slider has been found to be a common sight in the wild in Rhode Island, though Buchanan said he recently had a report of a Russian tortoise — another popular pet — that was discovered wandering around Coventry.

For those who want to get rid of a pet Red-Eared Slider, Buchanan doesn’t offer any easy alternatives.

“You’ve got to be committed to housing that turtle for 30 or 40 years until it dies,” he said. “That’s why this is such a problematic issue. It’s easy to buy a teeny turtle for ten bucks and think it’s no big deal, but that animal is going to live for a long time. When you purchase it, you have to be responsible for it for the rest of the turtle’s life.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Little towns that made things

In Haverhill. The town has become an arts center in recent years.

— Photo by Magicpiano

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

While driving up and down the Upper Connecticut River Valley the other week I came through several towns – Orford and Haverhill, N.H., stand out the most – with grand houses, beautiful churches and lovely commons. And they were all developed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries very soon after people arrived to take land long used by Native Americans! How did they afford it?

Well, because these very entrepreneurial and energetic Yankees used the region’s natural resources to maximum benefit – its good grass for sheep raising for the burgeoning wool trade, the wood from its forests (especially white pine to make buildings), its very arable land along the river and its water power --- to very early on create thriving businesses. Consider that by 1859, when Haverhill had 2,405 inhabitants, it had 3 gristmills, 12 sawmills, a paper mill, a large tannery, a carriage manufacturer, an iron foundry, 7 shoe factories, a printing office, and several mechanic shops! Those industries helped finance well run local schools and cultural institutions.

The lesson is that it’s good to have nearby enterprises that make things.

“The Mall,’’ in Orford, in 1907

New Bedford ‘Kinetic Grid’

“Kinetic Grid Over New Bedford,’’ by Bobby Baker. Copyright Bobby Baker Fine Art.

Artist note: “What may appear to be a double-exposure image is really just the artist seizing the opportunity to create a piece featuring both the unique art exhibit, ‘Kinetic Grid,’ and New Bedford architecture all in one space. This piece was created using late-day light and what would normally be considered bothersome reflections in the glass store front surrounding the exquisite work of artist of Soo Sunny Park. The distinct reflections are that of the building across Union Street, on the corner of Purchase Street.’’