The mobster vs. the monopolist

Mural "Purchase of Land and Modern Tilling of the Soil" (1938), by William C. Palmer, in the lobby of the Arlington, Mass., Post Office, a Colonial Revival building (see exterior below) that was opened in 1936. Many post offices erected or renovated during the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration had art work such as this mural, in part to help keep artists employed during the Great Depression.

From Robert Whitcomb’s Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com:

Maximum Leader Trump hates the U.S. Postal Service, which he alleges undercharges Amazon, run by Jeff Bezos, whom Trump envies and so detests And Mr. Bezos owns The Washington Post, which tries to vigorously report on the Trump mob. So the mobster-in-chief rejects a bailout of the Postal Service, which is far more essential to America than many of the institutions being bailed out. And he would love to hamstring efforts to encourage voting by mail this pandemic year in lieu of the usual crowds at polling places, because he thinks, correctly, that those votes will tend to be against him.

Oh yes. Trump votes by mail himself. I myself think that voting in person is better – except in a pandemic. That’s not only because it might be less vulnerable to fraud but also because showing up to vote at a polling place is a celebration of democracy.

In any event, the Postal Service, whatever its flaws, is an important part of America’s connective tissue, especially for the underprivileged, and needs to be protected.

By the way, none of this is to say that Amazon, like Google, Facebook and some other tech-based companies that have become so huge in the past two decades, aren’t too powerful and shouldn’t be broken up, as the now hollow Antitrust Division of the U.S. Justice Department would have done a half century ago.

Robert P. Alvarez: Don't let pandemic ravage the November election, too

The Balsams, a fancy resort hotel in Dixville Notch, N.H., in the White Mountains, and the site of the "midnight vote" that makes it the first place to vote in U.S. primary and general elections in every election year.

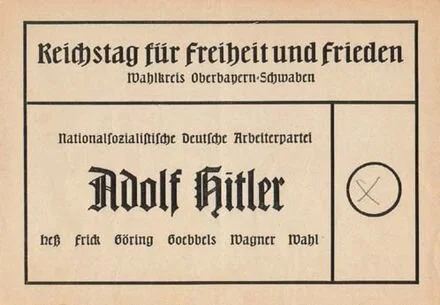

A ballot from the 1936 elections in Nazi Germany — nice and simple!

Via OtherWords.org

First, it was a public-health crisis. Now, it’s ravaging the economy. And for it’s next trick, the coronavirus is threatening to undermine the 2020 election.

Unless, that is, Congress steps in to ensure we can vote by mail.

If you’re curious what the worst case scenario is, look no further than Wisconsin, where a gerrymandered GOP legislature forced voters to the polls over the orders of the Democratic governor — and against the advice of public-health officials.

Wisconsin Republicans not only declined to send every voter an absentee ballot. They also appealed — successfully — to the conservative-majority U.S. Supreme Court to prevent voters who received their ballot late (through no fault of their own) from having their votes counted.

It was a transparent ploy by Wisconsin Republicans to support a conservative incumbent on the state Supreme Court by suppressing the vote. It failed — his liberal-leaning challenger won — but they struck a huge blow to voting rights in the process.

Fallout from the coronavirus exposed structural weaknesses in everything from our health care and education systems to market supply chains and labor rights. It also made painfully obvious the fragility of our electoral process.

Unfortunately, states have received little help from Congress in shoring up their elections. Just $400 million of the $2.2 trillion stimulus bill was earmarked for helping states cover new elections-related expenses stemming from the pandemic.

When it comes to providing the financial support necessary to ensure our elections are safe, accessible, fair, and secure, the last coronavirus response bill was a dereliction of duty.

Will it be safe to gather in large numbers by November? And even if it is, will voters feel comfortable standing in line, for up to six hours in some cases (thanks to GOP poll closures, but that’s another story), next to strangers?

If not, it’s fair to assume some voters will elect not to vote due to safety concerns. And that should undermine public confidence in the outcome.

The obvious solution is expanding voting by mail.

Unfortunately, Donald Trump is fiercely opposed to this. “They had things, levels of voting, that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again,” he said.

Let that sink in. The president — who himself voted by mail — openly views the right to vote as a threat to his presidency and party.

Americans shouldn’t have to choose between their health and their right to vote. In the midst of this pandemic, states with overly cumbersome processes for absentee voting are complicit in voter suppression. Period.

To fix this, we need to ensure no-excuse absentee voting in the next coronavirus bill — and that’s the bare minimum. Beyond that, we also need pre-paid postage for mail-in ballots and an extended early in-person voting period.

We need accessible, in-person polling places with public safety standards that are up to snuff. That means election workers must know they’re safe, and must have access to personal protective equipment.

We also need to develop and bolster online voter registration systems, and run public information campaigns giving voters localized, up-to-date voting guidelines.

To complete this nationwide, we’re looking at a $2 billion price tag. That’s just 0.1 percent of the $2 trillion package Congress already passed — and if it ensures our democracy doesn’t die in this pandemic, it’s worth every penny.

Robert P. Alvarez is a media relations associate at the Institute for Policy Studies. He writes about criminal justice reform and voting rights.

Chris Powell: In the COVID-19 crisis, both sides threaten liberty; block those raises!

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Fortunately it was just another brief bout of MAGA-lomania the other day when President Trump declared that he would decide when states lift the health and safety restrictions they have imposed because of the virus epidemic. Several governors, including Connecticut's Ned Lamont, quickly protested that the Constitution reserves such power to the states. New York's Andrew Cuomo protested most colorfully, noting that the president is not a king.

But amid the epidemic constitutional rights are under assault by many elected officials throughout the country, Democratic as well as Republican. Several states are imposing or threatening to impose penalties on religious services that exceed recommended attendance levels, in spite of the First Amendment's guarantees of freedom of religion and assembly.

Connecticut isn't immune to such assaults. Lamont skirted the Second Amendment's guarantee of the right to bear arms by telling gun shops they could remain open only by appointment. State Attorney General William Tong has joined other state attorneys general in a lawsuit to suppress publication of plans for guns that can be made by 3D printers, and this week Tong urged the federal government to criminalize such publication -- that is, to criminalize mere information, as if the First Amendment doesn't also guarantee speech and press rights.

The objection to making guns with 3D printers is that they can be manufactured without legally required serial numbers. But any gun can be, and the designs for many weapons have been published. If mere information can be criminalized in regard to gun designs, it can be criminalized for whatever government doesn't want people to know. Of course there would be no end to that.

Trump can't tell states when to lift their health and safety restrictions. But neither can Tong tell people what they can publish and read, no matter how politically incorrect it may be.

xxx

Yankee Institute investigative journalist Marc Fitch this week reminded Connecticut that as of July 1 state government employees are due to start receiving raises costing at least $353 million a year. Fitch noted that Democratic governors in New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia are suspending state employee raises until the immense financial cost of the epidemic can be calculated.

So the Yankee Institute urged Governor Lamont to suspend the raises as well, but it's not clear that he can. For the raises are part of state government's current contract with the state employee union coalition, one of the many lamentable legacies of Connecticut's previous administration, and the federal Constitution forbids states from making any law impairing the obligation of contracts.

It's bad enough that the wages and benefits of state and municipal government employees have been completely protected even as the governor's own orders have thrown tens of thousands of people out of work in the private sector. For state government to pay raises while unemployment explodes in the private sector and state tax collections collapse would be crazy, more proof that nothing matters more to state government than the contentment of its own employees, whose unions long have controlled the majority political party.

But the governor is not helpless here. Using his emergency powers he could suspend collective bargaining for state employees and binding arbitration of their contracts for six months at a time or "modify" those laws to strengthen public administration during the emergency. He should do so, for as the treacle on television says, we're all supposed to be in this together.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Philip K. Howard: Fighting a pandemic in red-tape nation

— Photo buy Jarek Tuszyński

America’s current crisis reveals the paralytic nature of its regulatory order.

America failed to contain COVID-19 because, in part, public-health officials in Seattle were forced to wait for weeks for bureaucratic approvals intended—ironically—to avoid mistakes. Now that the virus is everywhere, governors and President Trump have tossed rulebooks to the winds. It would otherwise be illegal to do much of what we’re doing—setting up temporary hospitals, organizing mass testing, buying products and services from noncertified providers, practicing telemedicine, using whatever disinfectant is handy . . . without documenting and getting preapprovals for each step.

America will get past this health crisis, thanks to the heroic, unimpeded dedication of health-care professionals. But what will save America from a prolonged recession? Many shops and restaurants will be out of business. Dormant factories and service organizations will need inspections before reopening. Schools and other social services will have to restart, with personnel changes and new needs that cannot be anticipated. Government agencies will be overwhelmed by requests for permits. Lawyers will present corporate clients with exhausting legal checklists. Lawsuits will be everywhere. Months, perhaps years, will pass as America tries to restart its economic engine while bogged down in bureaucratic and legal quicksand.

We need an immediate intervention to break America free from its bureaucratic addiction. It must be done if the nation is to come back whole in any reasonable time frame. The first step is for Congress to authorize a temporary Recovery Authority with the mandate to expedite private and public initiatives, including the waiver of rules and procedures that impede public goals. States, too, should set up recovery authorities to expedite permitting and waive costly reporting requirements.

Aside from broad goals, most regulatory codes don’t reflect a coherent governing vision. All these regulations just grew, one on top of the other, as successive generations of regulators thought of ways to tell people how to do things. Getting America up and running requires the ability to cut through all this red tape quickly. A Recovery Authority could expedite productive activity in many areas.

The U.S. ranks 55th in World Bank rankings for “ease of starting a business”—behind Albania and just ahead of Niger. The main hurdles are regulatory micromanagement and balkanization. You don’t get a permit from the “government” but from many different agencies, sometimes with contradictory requirements. Mayor Michael Bloomberg discovered that starting a restaurant in New York City required approvals from up to 11 agencies.

State recovery authorities could expedite permitting by creating “one-stop shops” such as those that operate in other countries. The lead agency would be given authority to waive rules and procedures not necessary to safeguard the broad public interest. Instead of waiting months, or longer, until inspectors can make site visits to verify compliance, the lead agency would have authority to grant permits, subject to later inspection.

To stimulate the economy, President Trump has floated the idea of a $2 trillion infrastructure plan. A big infrastructure buildout was promised as part of the 2009 stimulus as well—five years later, a grand total of 3.6 percent of the stimulus had been spent on transportation infrastructure. That’s because, as then-President Obama put it, “there’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”

Bureaucratic delay is ruinously expensive. In a 2015 report, “Two Years Not Ten Years,” I found that a six-year delay in infrastructure permitting, compared with the timeline in other countries, more than doubles the effective cost of infrastructure projects. I also found that lengthy environmental review is usually harmful to the environment, by prolonging polluting bottlenecks. Work rules and other bureaucratic constraints precluding efficient management multiply the waste of public funds. The Second Avenue subway, in New York City, cost $2.5 billion per mile; a similar tunnel in Paris, using similar machinery, cost about one-fifth as much.

The Recovery Authority could get people working immediately, and double our bang for the buck, by giving one federal agency authority (in most cases, the Council on Environmental Quality) the presumptive power to determine the scope of environmental review, focusing on material impacts; granting the Office of Management and Budget presumptive authority to resolve disagreements among agencies; and requiring that New York State and other recipients of federal funding waive work rules not consistent with accepted commercial practices.

Schools have become hornets’ nests of red tape and legal disputes. Reporting requirements weigh down administrators and teachers with paperwork. More than 20 states now have more noninstructional personnel than teachers—mainly to manage compliance and paperwork. Rigid teaching protocols and metrics cause teachers to burn out and quit. Almost any disagreement—with a parent over discipline, with a teacher or custodian over performance—can result in a legal proceeding, further diverting educators from doing their jobs. Federal mandates skew education budgets without balancing the needs of all the students. Special-education mandates now consume a third or more of some school budgets—much of it through obsessive bureaucratic documentation.

Getting schools restarted could easily get bogged down in bureaucratic requirements and defensive legal contortions. The Recovery Authority could replace reporting requirements with evaluations of actual performance. It could also replace entitlements with principles that allow balancing the interests of all students, and formal dispute mechanisms with informal, site-based review by parent-teacher committees.

The Recovery Authority should look at health-care innovations and waivers that have worked throughout the coronavirus crisis—such as telemedicine—and continue these practices, beyond the recovery period.

The federal Recovery Authority should aim to liberate initiative at all levels of society while honoring the goals of regulatory oversight. It should not be part of the executive branch, but rather, established along the same lines as independent base-closing commissions. For waivers of regulations and all other actions consistent with underlying statutes, the executive branch would be authorized to act on recommendations within the scope of the Recovery Authority’s mandate. For statutory mandates, Congress should explicitly provide temporary waiver authorization to permit balancing and accommodations.

Every president since Jimmy Carter has campaigned on a promise to rein in red tape. Instead, it’s gotten worse because no one has thought to question the underlying premise of thousand-page rulebooks dictating precisely how to achieve public goals. The mandarins in Washington see law not as a framework that enhances free choice but as an instruction manual that replaces free choice. The simplest decisions—maintaining order in the classroom, getting a permit for a useful project, contracting with a government—require elaborate processes that could take months or years. Essential social interactions—a doctor talking with the family about a sick parent, a supervisor evaluating an employee, a parent allowing children to play alone—are fraught with legal peril. Slowly, inexorably, a heavy legal shroud has settled onto the open field of freedom. America’s can-do culture has been supplanted by one of defensiveness.

COVID-19 is the canary in the bureaucratic mine. The toxic atmosphere that silenced common sense here emanates constantly from a governing structure that is designed to preempt human judgment. The theory was to avoid human error. But the effect is to institutionalize failure by barring human responsibility at the point of implementation. It’s as if we cut off everyone’s hands.

Coming out of this crisis, America needs a Recovery Authority to unleash potential across all sectors. Perhaps now is also the moment when Americans pull the scales from their eyes and see our bureaucratic system for what it is—one governed by a philosophy that fails because it doesn’t let people roll up their sleeves and get things done.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, writer, New York civic leader, photographer and founder and chairman of Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left.

David Warsh: With economic depression coming on, 'I believe in news'

Police attack demonstrating unemployed workers in Tompkins Park, in New York, in 1874, during the deep depression then.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The European and North American economies are entering a period of depression that already resembles the Great Depression more than any other experience in living memory.

This depression won’t last a decade; perhaps it will last no more than six or nine months. It will not end in a global war, though it certainly has exacerbated international relations. But lock-down policies to cope with the coronavirus pandemic already in place probably insure a couple of quarters that will set records for unemployment, bankruptcies and many more painful deprivations.

Now these policies are about to become the center of a political argument, the most consequential of the Trump presidency — 21st Century equivalent of the Battle of Gettysburg. That’s a strong analogy, I know. But compared to the earlier clashes of the Trump presidency – the Russia investigation, the impeachment trial – the continuing engagement over his handling of the pandemic will eventually deliver a climax worthy of the comparison. It will be radical opportunism vs. the pursuit of knowledge: Between now and Nov. 3, Trump will try to permanently divide the nation. It is not clear which side will win.

First things first. What happened in money markets over the course of the last few days bore little resemblance to the desperate events of September 2008. The coronavirus crisis hasn’t produced a systemic banking panic like the worldwide financial meltdown that threatened then. This time the Federal Reserve System has addressed only a series of alarms in various debt markets in which the underlying concern was about impending business losses. Former Federal Reserve Chairs Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke described the Fed’s actions and their limits in a bracing article March 19 in the Financial Times.

However, the Fed and other policymakers face an even bigger challenge. They must ensure that the economic damage from the pandemic is not long-lasting. Ideally, when the effects of the virus pass, people will go back to work, to school, to the shops, and the economy will return to normal. In that scenario, the recession may be deep, but at least it will have been short.

But that isn’t the only possible scenario: if critical economic relationships are disrupted by months of low activity, the economy may take a very long time to recover. Otherwise healthy businesses might have to shut down due to several months of low revenues. Once they have declared bankruptcy, re-establishing credit and returning to normal operations may not be easy. If a financially strapped firm lays off — or declines to hire — workers, it will lose the experienced employees needed to resume normal business. Or a family temporarily without income might default on its mortgage, losing its home.

On March 16, former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh (no relation of mine) criticized the “2008-style barrages” of Fed measures the day before, including cutting its short-term policy interest rate to near zero. He called for the creation of a Government Backed Credit Facility (GBCF), a huge loan facility, to be administered by 12 regional Federal Reserve banks, backstopped by the Treasury, to lend to companies in danger of going broke who are willing to pledge assets in return for the money.

Meanwhile, Congress publicly debated Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Treasury Secretary Steven Munchin’s plan to write checks to help individuals get through their hard times. Behind the scenes, the rest of Munchin’s plan: $50 billion for the airlines, $150 billion more for other troubled businesses, and $300 billion for small- business loans.

That was before governors began shutting down their states’ economies with orders of various degrees of severity – Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Texas, California, Illinois and New York.

The backlash began on March 17, when Stat, a widely respected, Boston-based online news organization, published “A Fiasco in the Making?’’, by John P.A. Ioannides, a professor of statistics and epidemiology at Stanford University. As a top expert on statistical sampling, Ioannides complained of the dearth of broad samples of the rate of infection and death. But based on the limited evidence from the one thoroughly studied sample – the 700 passengers of the Diamond Princess cruise ship, of whom seven persons have died – the “kill rate” of Covid-19 might be somewhere between 0.05 percent and 1 percent of those infected, or about the same as regular flu.

If that were determined by better sampling to be the case generally, Ioannides argued, then extreme measures taken could have perverse effects. Or as my friend Lou Fedorkow put it in calling the article to my attention, the United States, having reacted to the 9/11 attacks by going to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, today may be responding to the COVID-19 virus pandemic by going to war with itself.

Also on March 17, the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal, confusing financial-market distress with panic about the economy itself, began a series of editorials, which, in the course of the week, worked their way through to the conviction that the lock-downs were disastrous and needed to be undone. In “Financing an Economic Shutdown, ‘‘ they complained that “Some state and federal leaders [were] shutting down the economy without a plan to finance it while everyone stays home.” They lauded former Governor Warsh’s plan.

The next day, “The Fiscal Stimulus Panic’’ advocated Food Stamps and expanded jobless insurance instead of those checks, which were said to be motivated by a “Keynesian illusion.” On March 19 came “Economic Rout Accelerates’’:

You don’t calm a panic by floating ill-considered trial balloons or chanting “go big” as an illusion of proper and thoughtful action. Markets are panicked in part because they sense that our political leaders are more panicked than the public is.

You calm a panic first by looking like you know what you’re doing. You explain that this is a liquidity problem caused by an extraordinary precaution against a virus that is closing down businesses. The government needs to act to prevent the liquidity panic from becoming a solvency rout that becomes a banking crisis. And it needs to act fast.

By March 20, the editorialists had recognized the likelihood of depression and were “Rethinking the Coronavirus Shutdown’’.

If this government-ordered shutdown continues for much more than another week or two, the human cost of job losses and bankruptcies will exceed what most Americans imagine. This won’t be popular to read in some quarters, but federal and state officials need to start adjusting their anti-virus strategy now to avoid an economic recession that will dwarf the harm from 2008-2009.

And on March 21, in “Leaderless on the Economy,’’ repeating its mantra, “Government needs to address the liquidity crisis it has created for private business, or this will soon become a solvency panic as companies default on debt and fail, which will turn into a banking crisis.” Criticizing “The Extreme State Lockdowns’’ in New York and California as “unsustainable,” they concluded,

Americans may simply decide to ignore the orders after a time. Absent a more thorough explanation of costs and benefits, we doubt these extreme measures will be sustainable for long as the public begins to chafe at the limits and sees the economic consequences.

As usual, it was left to WSJ columnist Holman Jenkins Jr., the sharpest member of the Editorial Board, to draw out the implications. On March 21, in “What Victory Looks Like in the Coronavirus War,’’ he argued for taking what had been the British approach: isolate those who test positive for the disease and encourage everybody else to take care with their sneezes, hand-washing, etc. He continued,

Inconveniently for my argument, the U.K., a pioneer of such thinking, is now shifting to an accept-a-depression-and-wait-for-a-vaccine approach. The medical experts and their priorities are hard to resist. Resisting their wisdom doesn’t come naturally in such a situation.

Happily, I have confidence in the American people to let their leaders know when the mandatory shutdowns no longer are doing it for them. Strange to say, I have confidence in our political class to sense where the social fulcrum lies. A reader emails that Donald Trump could declare victory at the end of 15 days, claim the blow on the health-care system has been cushioned, and urge Americans, super-cautiously, to resume normal life. This idea sounds better than waiting for spontaneous mass defections from the ambitions of the epidemiologists to undermine the authority of the government.

Meanwhile, Bret Stephens, who left the WSJ Editorial Board in 2017 for a column in The New York Times because he so objected to the former’s embrace of Trump, made a similar point March 22 in “It’s Dangerous to be Ruled by Fear’’:

Sooner or later, people will figure out that it is not sustainable to keep tens of millions of people in lockdown; or use population-wide edicts rather than measures designed to protect the most vulnerable; or expect the federal government to keep a $21 trillion economy afloat; or throw millions of people out of work and ask them to subsist on a $1,200 check.

And as if to put a human face on the opposition to current policy, the news pages of the WSJ, a preserve of traditional news values, discovered and described entrepreneur Elon Musk’s holdout for days against suspending car production in his Fremont, Calif., “The coronavirus panic is dumb,” Musk argues.

How do these policy decisions get made? I don’t know a better answer – a glimpse of an answer – than “The Humanitarian Revolution” chapter in Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Viking Penguin, 2012). The origins of today’s policy of lockdown is more a question of culture evolving than the existence of an epidemiological “deep state.” Obviously the costs and benefits of various approaches to managing the epidemic should be regularly examined, Bayesian-fashion – without ridicule. As for the covid-19 pandemic, I come down on the side of the Rev. Thomas Bayes (1701-1761), who argued more than 250 years ago that, statistically, we learn from experience; specifically, that by updating our initial beliefs with carefully obtained new information, we improve our beliefs about the prospects of whatever we undertake to know. In other words, I believe in news.

So get ready for a ferocious debate about the measures adopted. It seems certain to grow in bitterness and carry on down to Election Day. The situation is encapsulated in this 40-second viral clip from a presidential news conference. Watch it twice, the first time for epidemiologist Anthony Fauci’s reaction to what the president is saying, the second time to see the look Fauci eventually receives from Trump. That was the moment in which the climactic battle of Trump’s presidency began.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

James P. Freeman: Negative interest rates? Be careful what you wish for

“You OK?” -- Clay Easton, from the film Less Than Zero (1987)

BRAINTREE, Mass.

Last fall, as markets were reaching Everest heights, President Trump began calling for below-zero interest rates in the United States, a phenomenon that has beset many European countries and Japan, to little positive effect. While appealing on the surface, supporters of such an interest-rate environment should temper their enthusiasm and take caution: Be careful what you ask for.

On Sept. 11, 2019, President Trump tweeted, “The Federal Reserve should get our interest rates down to ZERO, or less, and we should then start to refinance our debt.” The president renewed such calls last November, during a speech at the Economic Club of New York. He claimed that comparatively higher interest rates in the United States “puts us at a competitive disadvantage to other countries.” And, more recently, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January, he echoed similar sentiments. Other nations, Trump said, “get paid to borrow money, something I could get used to very quickly. Love that.”

Negative interest rates are not normal, and they have never occurred in America.

So, what exactly is going on here?

Typically, in any given lending arrangement, the borrower pays back principal and compensates the lender with interest for use of the money. A loan with a longer duration usually fetches higher rates; a loan with a shorter duration usually fetches lower ones.

But in some sectors of the global credit markets something strange has happened -- the underlying mechanics of that understandable and long-held lending model have changed. It is the borrower who is compensated, not the lender. In other words, a lender who lent $100 with a 3 percent interest rate received a $103 return. Now, that same lender may be receiving -- theoretically, in a market with negative rates -- only $97, not $103.

For nearly 40 years interest rates in the United States and around the world have dropped dramatically (in 1980 the U.S. Prime Rate peaked at 21.50 percent; today it stands at 4.25 percent, according to “FRED,” the economic research arm of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis). Both consumers and corporations have been the beneficiaries of the low cost of borrowing money. It fueled what some see as the greatest period of prosperity in America history. Causally and conversely, however, it acted as the catalyst for massive levels of borrowing, as the government for decades has spent more than it received. In addition, government -- at all public-sector levels, federal, state and local -- likewise has been a beneficiary, financing massive levels of debt at low cost. But the federal government is different.

The federal government is granted the authority to control both monetary policy (interest rates and money supply) as well as fiscal policy (taxes and spending). Created in 1913, the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) is the country’s quasi-independent central bank, and responsible for supervising the nation’s banks, overseeing the stability of the financial system, conducting monetary policy and, perhaps most importantly, maintaining the dollar as a store of value. On the other hand, fiscal policy is determined mostly by Congress with input from the president. For decades, both the legislative and executive branches have agreed to increase the size and scope of government without paying for it (deficits and debts). And tax rates have trended downwards for decades too (most recently with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017).

Ostensibly economic tools, fiscal and monetary policies are nevertheless dictated by political actors, and prone to political motivations. Nevertheless, such polices, when effected sensibly and even harmoniously, can promote economic growth and stability. Of course, global disruptions and market imbalances coupled with bad decisions have, at times, wrought havoc. Such events are mostly garden-variety downturns while others are more severe, like The Great Depression, which started in 1929, and The Great Recession of 2008-2009.

Policymakers took extraordinary measures in 2008-2009 to stave off a total collapse of the financial system and a real depression. Of particular import was unprecedented monetary policy. The Fed brought short-term rates close to zero and greatly expanded the money supply by injecting trillions of dollars into the financial system. As a result, markets recovered, and the U.S. economy went on to the greatest bull run in history. Notably, though, the Fed largely kept these extraordinary polices intact, even as the stock market rose to record highs and unemployment fell to near-record lows.

Therein lie the problems.

Some market observers have opined that the market rally in 2019 and early 2020 was a perversion precisely because of constant Fed intervention. They argue that this was a Fed-induced asset bubble. These same observers cite the central bank’s maintenance of artificially low interest rates (three reductions in the Federal Funds Rate in 2019), flooding the market with trillions of dollars in cash or liquidity (by buying U.S. Treasury securities, known as Quantitative Easing, “QE”), and what is called “Repo” (supporting overnight lending among big banks, a form of money flow or plumbing for Wall Street) -- all during a roaring market and booming economy. It was reasonable to ask, observers wondered, why the Fed was doing all this during good times. Such actions were historically reserved only for extreme market disruptions that threatened the American economy.

The Fed was not alone in its actions.

Most European countries did not see economic expansion of the size of the American one in the 2010s. Their recovery was much more muted. As a result, in order to spur economic activity, European interest rates were set even below American rates. In June of 2014, a stunning event occurred. The European Central Bank (ECB) introduced negative rates by lowering its deposit rate to minus 0.1 percent to stimulate the economy. It proved to be overall futile. Eurozone countries (and Japan) never fully recovered and economic growth remained anemic at best.

By 2019, 14 countries had sovereign debt with negative yield as markets and governments drove down rates. Today, the global pool of such securities is about $12 trillion, and includes some corporate debt. Last September, the ECB cut its already negative deposit rate to minus 0.5 percent. In fact, 56 central banks cut rates 129 times last year, according to data from CBRates, a central bank tracking service. Some market participants have questioned the efficacy of such monetary policy, given little to no economic growth as a result. And policy makers are perhaps finally realizing that monetary policy alone has its limits.

There’s a growing negative perception of negative rates reflecting the negative impact.

Still, there are other reasons why yields have plunged. Think of the basic supply-demand equation. While governments have been issuing an enormous supply of low-yielding debt there has also been an enormous demand for government securities. Most government bonds are known to be a safe harbor for investors in times of turbulence, as they can be used to hedge against all sorts of risk (market, political, etc.). Of course, the safest of safe harbors has been and continues to be the United States.

In times of crisis, global investors have always sought protection by buying U.S. Treasury securities, as these securities offered a reasonable rate of return and penultimate safety. But even in times of relative tranquillity these securities have been attractive for domestic investors, particularly pension plans, senior citizens, and financial institutions. Over time and into early 2020, a convergence of market dynamics -- heavy demand, along with heavy Fed buying and issuing of large quantities of Treasuries (supply) -- have brought yields down substantially and have made government securities very expensive. Even before the novel Coronavirus called COVID-19.

The long-term average yield of the U.S. 10-Year Treasury Note, the American bellwether security, is 4.49 percent. A year ago, the 10-Year yielded 2.64 percent. It has fallen steadily since (ycharts.com and FRED). Now, with the global pandemic, the yield recently hit an intra-day record low of 0.31 percent.

The Coronavirus has, if anything, exposed the fragility of current markets. In classic crisis mode, investors have been fleeing global stock markets and stampeding the U.S. government bond market. Yields across the spectrum of treasury maturities (3-month to 30-year) have set record lows, driven by record demand and Fed intervention with barrels of liquidity.

Just over a week into a global stock sell off, on March 3, the Fed cut the Federal Funds Rate by half a percentage point (for a targeted range of 1.0 percent to 1.25 percent) in response to the threat posed to the economy by the Coronavirus. This emergency action was the first time that the Fed cut rates for a public-health challenge, not a financial one.

And in another emergency move on Sunday, March 15, following two weeks of market carnage, the central bank set this rate to effectively zero as markets continue to roil -- matching similar action taken during the financial crisis in 2009, along with more massive QE. It is now entirely possible that the Fed Funds Rate may be set in a negative range and U.S. Treasury yields could turn negative for the first time as well. Even despite the slow lurch to negative yield, on a conference call on the same day of the latest action, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell dismissed the likelihood of using such a tool.

“We do not see negative policy rates as likely to be an appropriate policy response here in the United States,” Powell told reporters.=

Well.

As the robot in Lost in Space warned: “Danger Will Robinson! Danger!”=

No one in America quite knows how to navigate the unchartered frontier of negative yields. There is no play book or history book. Or Book of Revelation.

Some of the consequences of rates marching to zero are already apparent. One is that the government via the Fed (monetary policy) has incentivized undue risk-taking. Lower government bond yields have forced otherwise conservative investors to chase higher returns in stocks and corporate bonds, creating unmanageable asset bubbles. (Will Treasuries in 2020 become the tulips of 1637?)

Congress and the president (fiscal policy) have been incentivized to borrow even more money (under the absurd assertion that the country can “grow” its way out of debt; during the bull run debt grew significantly). Remember, candidate Trump in 2016 promised to not only reduce the national debt, but actually eliminate it. At over $23 trillion today (CNBC reported last February), the debt has grown by $2 trillion under President Trump.

Arguably, disastrous monetary policy has financed even more dreadful fiscal policy.

America used to borrow for the future. We now borrow from the future. Record low yields have fueled record amounts of debt. One unintended consequence of this predicament is that it unwittingly gives legitimacy to the absolutely ludicrous idea of “Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT). Properly understood, the theory allows that government can and should print as much money as it needs to spend because it can not become insolvent, unless there is a political reason to do so. MMT treats debt simply as money that the government has placed into the economy and did not tax back. Furthermore, and rather dangerously, MMT advocates believe that there are no consequences to staggering levels of debt. They simply ignore abundant evidence to the contrary (history is littered with examples of sovereign default).

There are more tangible and immediate consequences to consider as well. In a simpler time, the bond market was known as the “fixed-income” market. For a good reason. Most bonds paid a fixed amount of interest, usually every six months. A steady stream of interest provided investors with income. Negative yield penalizes savers who have relied upon Treasury securities for safety and some rate of return. Why would seniors want to pay borrowers for the use of their money?

Negative yield also affects banks and other financial institutions, such as insurance companies. These entities rely upon yield to fund operations. Annuities, for instance, are financial contracts whose rates of return depend on market instruments, such as fixed-income securities. And pension plans assume a certain future return for actuarial purposes.

JPMorganChase Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon has expressed concern. At the same Davos event that the president spoke at in January, the head of America’s biggest bank expressed “trepidation” about “negative interest rates.” He added that, “It’s kind of one of the great experiments of all time, and we still don’t know what the ultimate outcome is.” Last October he told a group attending the Institute of International Finance he would “not buy debt at below zero.” And with a sense of gravitas, Dimon concluded, “There is something irrational about it.”

If the government started issuing negative-yielding debt, banks would need “to find other ways to replace the income they need to generate from their deposits at the Fed,” believes Michael Hennessy, chief executive of Harbor Crest Wealth Advisors. One way to do that would be to raise fees on consumers. Another option -- a nuclear option? -- would be for banks to offer negative deposit rates to the average saver and consumer. That outcome is nearly unimaginable.

Then there is the tax code. Writing for The Wall Street Journal last November, Paul H. Kupiec said he believed that the tax code can’t handle negative rates. “Should negative interest rates one day become reality,” he writes, “the tax code will need to be amended.” Kupiec also says that negative rates would effectively be a “new federal tax levied by the Fed on banks.” Negative interest rates are treated as a consumer expense, and right now current law doesn’t allow such an expense to be deducted when calculating taxable income.

Finally, there is the general perception that negative yield carries: People feel poorer. They would be drained of income. They would not be paid for the use of their money. On the contrary, they may be paying people for the use of their money. Marked deflation is just as bad as marked inflation. Besides, such a precipitous drop in Treasury yields and the corresponding inversion of the yield curve (when yields in longer maturities are lower than yields in shorter maturities) portend recession. Recessions are normal and natural. Yet, with twisted irony, the federal government -- with all its extravagant intervention -- has exacerbated not only the likelihood of a recession but perhaps its severity, too.

Joseph Brusuelas, RSM chief economist and a member of The Wall Street Journal’s forecasting panel, strikes a cautionary tone. He reasons: “Because the U.S. economy is so highly ‘financialized’ [meaning it is reliant on big banks to provide liquidity], negative rates wouldn’t yield a good outcome in the long-term.”

James P. Freeman is the director of client relations at Kelly Financial Services LLC, based in Greater Boston. This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase any interest in any investment vehicles managed by Kelly Financial Services, LLC, its subsidiaries and affiliates. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not accept any responsibility or liability arising from the use of this communication. No representation is being made that the information presented is accurate, current or complete, and such information is at all times subject to change without notice. The opinions expressed in this content and or any attachments are those of the author and not necessarily those of Kelly Financial Services, LLC. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not provide legal, accounting or tax advice and each person should seek independent legal, accounting and tax advice regarding the matters discussed in this article.

Llewellyn King: Now that the pandemic has shut us in what will we do with our time?

Centreville Mill, on the Pawtuxet River, in West Warwick, R.I. Llewellyn King lives in a converted mill on the same river in West Warwick.

For more than a decade, I’ve been writing about the isolated, the lonely, the abandoned: Those who feel that the world has no place for them. Now all of us will know something of their isolation and, in the case of people who live on their own, loneliness.

Those I’ve been writing about are the luckless hundreds of thousands in the United States – millions around world -- who suffer from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, now known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME). They are sentenced to live separately by their illness and its debilitating fatigue. They are a kind of living dead. Now I have a glimmer, no more to be sure, of how it must be every day for these sufferers

What will it be like for the rest of us in two weeks when we’ve exhausted the pleasures of home life and yearn to see our friends, go to a restaurant, a play or a concert? Just to live normally?

I’ve always tried to console myself with what I call “adventure therapy.” Like most pop psychology it isn’t very profound, but it does help. Will it help now? I have no idea.

Anyway, the therapy is that you try to find the adventure in any situation you’re in, which can include some hairy ones, like facing surgery. (Who will you meet? What’s all the equipment? How will they perform the surgery? Do the doctors like doctoring? What kind of life do the nurses live?)

In my own home -- mercifully which I share with my ever-cheerful wife -- I wonder where the adventure lies in this crisis.

First, I know I won’t write the Great American Novel or any work of fiction. I won’t write my life story, as I’m constantly advised to do. My ego is robust, but I’m not sure it’s robust enough for that.

Oscar Wilde worried about “third-rate litterateurs” picking over the lives of dead writers. Of course, it seems to me some lives are lived with an eye to posterity.

I’m always amazed at people who in the middle of great trauma or great events have time to sit down and write what they think and feel. I’m glad they do, but I don’t think we’re entitled. The world loves Shakespeare’s works and knows little about him.

We know too much about people of minor achievement whom we call celebrities. We watch them and their petty lives with the attention of a fakir watching his snake. Yeah, I’m no better. I want to know what’s to become of Meghan and Harry, where will Lindsay Lohan settle and, only somewhat less trivially, what are the late-night comedians doing with their spare time now that we learn that they need huge staffs to be funny?

I do think that we need a record of our times, often informed by memoirs. Unfortunately, and inexcusably, when the Trump era is behind us, we’ll know too little about what went on in the inner councils of the White House. President Trump has shown near contempt for the Presidential Records Act, inspired by the fall of President Richard Nixon. Trump writes little and destroys much that it written, we’re told.

One has always dreamed of a time when there was enough leisure to read, maybe plow through Tolstoy, give Proust another go, or try to understand Chinese literature. But I think that won’t happen. I’ll read the same kind of books I always read: biographies and crime stories. Most likely I’ll read a bit more, curse television a bit more, and squander my time watching and reading the news about COVID-19.

As I struggle to avoid the temptations of the refrigerator and that reproving word processor (It whispers, “Write a book.”), I’ll wonder about those who existed before this pandemic in a long, dark tunnel of isolation without hope of light at the end: Those who can hardly hope to break out one day into what Winston Churchill called the “sunlit uplands.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: A prize is needed for ideas on dealing with nuclear waste

Places in Continental United States where nuclear waste is stored

A “scram” is the emergency shutdown of a nuclear power plant. Control rods, usually boron, are dropped into the reactor and these absorb the neutron flux and shut it down.

President Trump, a supporter of nuclear power, has in a few words scrammed the whole nuclear industry, or at least dealt its orderly operation a severe blow.

Scientists see nuclear waste as a de minimus problem. Nuclear-power opponents — who really can’t be called environmentalists anymore — see it as a club with which to beat nuclear and stop its development

The feeling that nuclear waste is an insoluble problem has seeped into the public consciousness. People, who otherwise would be nuclear supporters, ask, “Ah, but what about the waste?”

For its part, the nuclear industry has looked to the government to honor its promise to take care of the waste, which it made at the beginning of the nuclear age.

In the early days of civilian nuclear power — with the startup of the Shippingport Atomic Power Station, in Pennsylvania, in 1957 — the presiding theory was that waste wasn’t a problem: It would be put somewhere safe, and that would be that.

Civilian waste would be reprocessed, recovering useful material like uranium and isolating waste products, which would need special storage. The most worrisome nuclear byproducts are gamma, beta and X-ray emitters, which decay in about 300 years.

The long-lived alpha emitters, principally plutonium, must be put somewhere safe for all time. Plutonium has a half-life of 240,000 years. It’s pretty benign except that it’s an important component of nuclear weapons.

If you get it in your lungs, you’ll almost certainly get lung cancer. Otherwise, people have swallowed it and injected it without harm. It can be shielded with a piece of paper. I have handled it in a glovebox with gloves that weren’t so different from household rubber ones.

But it’s plutonium that gives the “eternal” label to nuclear waste.

Enter President Jimmy Carter in 1977. He believed that reprocessing nuclear waste — as they do in France, Russia, Japan and other countries — would lead to nuclear proliferation. Just months in office, Carter banned reprocessing: the logical step to separating the cream from the milk in nuclear waste handling.

Since then, it’s been the policy of succeeding administrations that the whole, massive nuclear core should be buried. The chosen site for that burial was Yucca Mountain, in Nevada. Some $15 billion to $18 billion has been spent readying the site with its tunnels, rail lines, monitors and passive ventilation.

In 2010 Sen. Harry Reid (D-Nev.) — then the majority leader in the Senate — said no to Yucca Mountain. It’s generally believed that Reid was bowing to casino interests in Las Vegas, which thought this was the wrong kind of gamble.

The industry had pinned all its hopes on Yucca Mountain being revived under Trump: He had promised it would be. Then on Feb. 6, and with an eye to the election (he failed to carry Nevada in 2016), Trump tweeted, “Nevada, I hear you and my administration will RESPECT you!

In the Department of Energy, which was promoting Yucca Mountain, gears are crashing, rationales are being torn up and new ones thought up, even as the nuclear waste continues to pile up at operating reactors. No one has any idea what comes next.

Time, I think — after watching nuclear-waste shenanigans since 1969 — to take a very fresh look at nuclear- waste disposal. Most likely, a first step would be to restart reprocessing to reduce the volume.

I’ve been advocating that to leave the past behind, a prize, like the XPRIZE — maybe one awarded by the XPRIZE Foundation — should be established for new ideas on managing nuclear waste. The prize must be substantial: not less than $20 million. It could be financed by companies like Google or Microsoft, which have lots of money, and a declared interest in clean air and decarbonization.

The old concepts have been so tinkered with and politicized that nuclear waste is now a political horror story. Make what you will of Trump being on the same side of nuclear-waste management as presidents Carter and Barack Obama.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Containers or low-level nuclear waste

Llewellyn King: Ditch your optimism: U.S. democracy is imperiled

We are an optimistic people. And in today's world, there's the rub.

By nature, we are sure that the extremes of any given time will be corrected as the political climate changes and elections bring in new players. The great ship of state will always get back on an even keel and the excesses, or omissions, of one administration will be corrected in the next.

Maybe not this time.

The norms uprooted by President Trump are possibly too many not to have left lasting damage to this Republic.

Consider just some of his transgressions:

· We have abandoned our place as the beacon of decency and the values enshrined in that.

· America's good name has gone up in smoke, as with the Paris climate agreement and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear forces (INF) treaty.

· The president has meddled in our judicial system by intimidating prosecutors and seeking to influence judges.

· The president has blown on the coals of prejudice and sanctioned racial antagonism.

But above all, Trump has tested the constitutional limits of presidential power and found that it can be expanded exponentially. He has expanded executive privilege to absolute power.

Trump has done this with the help of the pusillanimous members of the Senate and the oh-so-malleable Atty. Gen. William Barr – his new Roy Cohn.

The most pernicious of Trump’s enablers, the eminence grise behind the curtain, gets little attention. He is Rupert Murdoch, a man who has done a lot of good and incalculable harm.

The liberal media rails -- indeed enjoys -- railing against Fox News but has little to say about the 88-year-old proprietor who, with a single stroke, could silence Sean Hannity and tame Tucker Carlson (whom I know and like).

But Murdoch remains aloof and silent. The power of Fox is not its editorial slant but that it forms a malignant circle of harm. It is Trump’s daily source of news, endorsement, prejudice, and even names for revenge.

There are two other conservative networks, OAN and Newsmax. But neither has the flare that Fox has as a broadcast outlet, nor acts as the eyes and ears and adviser to the president.

I am an admirer of Murdoch in many ways. But like a president, maybe he should get a lot of scrutiny.

Murdoch’s newspapers in Australia, where they dominate, have rejected climate change, and possibly played a role in the country not being prepared for the terrible wildfires.

In Britain, he has stirred feeling against the European Union for decades. His Sun, the largest circulation paper, is Fox News in print and was probably the template for Fox having campaigned ceaselessly and vulgarly against Europe.

After long years of watching Murdoch in Britain and here, I know the damage he can do and why he should be named. I must say, though, that Murdoch's Wall Street Journal is a fine newspaper, better than before he bought it.

The Democrats, to my mind, present a sorry resistance. None of their presidential candidates has delivered a speech of vision, capturing the popular imagination.

Democrats search the news for the latest Trumpian transgressions and get a kind of comfort by seeing, by their lights, how terrible he is. But there is none of the old confidence that the president will be trounced in the next election and the ship of state will right itself because it always does.=

Maybe it will list more.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: If only Trump had a dog

Collage from Wikipedia

How different President Trump’s State of the Union speech would’ve been had he included something like this: “At the White House, we are overjoyed at the arrival of a new friend and counselor, Lancelot, a stray from a Washington animal shelter.”

He could, of course, have gone on about what a joy the dog would be to his 13-year-old son Barron; how the boy could learn about perfect love, forgiving adoration, uncritical companionship and eternal job approval -- things otherwise missing from the political upbringing and life in Washington.

But Trump didn’t. He didn’t care about all the wonders that enter a human life when four feet come through the door, intent on forever residence.

Barron won’t know those wonders. And the president won’t get the one-issue dog voters.

Trump has said that he’s too busy to have a dog. Well, having watched presidential dogs from Richard Nixon’s King Timahoe, an Irish Setter, to the hypoallergenic Portuguese Water Dogs favored by the Obamas, I can attest there’s help aplenty at the White House for a dog. They needn’t inhibit an arduous golf schedule. They’re always the darlings of the media, the Secret Service and pro-pet cabinet members and dignitaries. Queen Elizabeth used to get though meetings with people she had nothing in common with otherwise with a few words about her Welsh Corgis.

Trump’s doglessness is, in my view, a cold heart problem. How he could’ve warmed his self-aggrandizing State of the Union speech with a line or two about a dog. Dogs are so humbling: It’s hard to be pompous when cleaning up after a puppy accident.

Clearly Trump’s love of Trump is so compleat there’s no room for a bundle of furry joy in his heart, filled as it is with self-regard.

In our house, Valentine’s Day is Dog Day. My wife Linda Gasparello says Feb. 14 is the birthday of all dogs with no known day of birth. Love, you see.

It all began because one Valentine’s Day, I gave her a shelter dog of uncertain age and parentage. She had some German Shepherd in her, definitely some Airedale terrier, and a pinch of this and dash of that.

What she had was a deep commitment to taking over running the house and stable -- and disciplining our Siberian Husky. Her love and loyalty were total: Even when she was old and arthritis had slowed her, as it does so many dogs, she would drag herself up the staircase to sleep in our bedroom.

We named her Valentine, although the shelter workers in Leesburg, Va., told me the family who turned her in named her Gal. She was no gal. She was a dame, made to preside.

Of the many dogs we’ve had, I believe Valentine was the cleverest. She thought and she worried. The cure for her anxieties was routine and order; things in their places and activities at given times, like going on a hack or hosting a dinner party. Whenever she would hear Linda speaking on our PBS program “White House Chronicle,” turned on in the living room, and speaking at the same time in the kitchen, she was distraught: This couldn’t be. She ran to Linda in the kitchen to be assured and back into the living room to be unassured, and back again into the kitchen, deeply upset that someone could be in two places at the same time.

To go through life without a dog, a Valentine of your own, is to miss one of the great dimensions of love: that between dog and owner, although it’s debatable who owns whom. Valentine owned us.

So, The Donald has no dog and the White House is, in that sense, incompletely furnished. No great bounding down the driveway to meet visitors coming through the Northwest Gate (where reporters enter too), no conversation starter with heads of state, and no care for the Dogs Come First voters.

Of course, there are those, like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who hope that come November, Trump will need a dog: a comfort dog.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Always pick the richest parents you can find

Too small for the Sussexes? The great hall in The Breakers, the old Vanderbilt mansion in Newport

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Of course, things are always rigged for the rich and well-connected –why complain that rocks are hard! -- but since the Second Gilded Age started back in the ‘80s we set new levels of goodies for the privileged. Consider Hunter Biden’s stretch of getting paid $50,000 a month for sitting on the board of a Ukrainian gas company although he knew little about that industry. Then we have Chelsea Clinton, the only child of Bill and Hillary, pulling in $9 million in salary and stock since 2011 for sitting on the board of the Internet investment company IAC/InterActive Corp., which happens to be controlled by mogul Barry Diller, a pal of the Clintons.

Still, that’s bush league compared to the Trump Family’s profiteering off Daddy’s occupation of the Oval Office and steering vast sums of foreign and U.S. government money to Trump resorts and hotels. The Constitution’s Emoluments Clause? What’s that?!

And now the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have decided they want to make a killing, er be “financially independent,’’ and withdraw from many of their tedious public duties as Royals. Are Sussex sweatshirts coming up? Too tacky! Think luggage. There’s a push on to get them to move to Rhode Island. Maybe a shingle-style mansion near Taylor Swift’s pile on Watch Hill?

Llewellyn King: U.S. takes shenanigans from Zambia lying down

Victoria Falls, Zambia’s most famous site

What does it matter if a U.S. ambassador runs afoul of the administration in a piddling African country where the inhabitants suffer chronic poverty and bad government?

It so happens it matters a lot.

Here is the story: One of our most experienced ambassadors, Daniel Lewis Foote, with a distinguished diplomatic career, often in hot spots like Afghanistan, Iraq and Haiti, criticized the administration and the justice system of Zambia, a landlocked country in Southern Africa, for sentencing a gay couple to prison for 15 years for having sex. Zambians, who are committed Christians with a fundamentalist slant, were approving. Foote said he was horrified.

The president of Zambia, Edgar Lungu, joined the fray. Homosexuality he told a British interviewer, was unbiblical and unchristian. Foote, who felt that he had been badly treated as a diplomat since his arrival in 2017, was having difficulty in meeting with Lungu despite the $500 million a year that the United States gives Zambia in debt-free assistance.

Then Foote, who also had been seething, apparently, over blatant corruption by Lungu and his family, published on the Internet a strong indictment of the Lungu administration.

That was too much for the Zambian government.

The government made the dispute with the United States public and stirred up the people. Lungu said Foote had to go and, amazingly, the State Department agreed without struggle and Foote was ordered back to Washington.

In his statement, Foote had laid out the situation clearly, “My job as U.S. ambassador is to promote the interests, values and ideals of the United States. Zambia is one of the largest per capita recipients of assistance in the world, at $500 million each year. In these countries where we contribute resources, this includes partnering in areas of mutual interest and holding the recipient government accountable for its responsibilities under this partnership.”

Lungu’s response to Foote’s statement was clear, too, “We do not want him here.”

And the State Department conveniently obliged, even while regretting that the government in Lusaka, Zambia’s capital, had effectively declared Foote “persona non grata.”

The effect across Africa and in other small nations may be to embolden them to silence ambassadors. Lungu has kicked sand in the eyes of the mighty United States and we have run. American values will not be on the table.

Tibor Nagy, the assistant secretary of state for Africa, tweeted lamely, “Dismayed by the Zambian government’s decision requiring our Ambassador Daniel Foote’s departure from the country.”

Yes, there is room for dismay; and it is dismay with the way this issue has been handled in Washington. A stellar career ambassador appointed by President Trump has been pushed out of his post by a government that has been dependent on foreign aid both in cash and advice. Foote also pointed out in his statement that the “American people have provided more than $4 billion in HIV/AIDS support in the last 15 years. Working closely with the Ministry of Health, we currently have well over 1 million Zambians on life-changing antiretroviral medicine, touching close to half of the families in the country.”

If things had gotten too sticky for Foote to continue in Lusaka, he could have been reassigned and a new ambassador appointed. One way or another, he should not have been put in the position of leaving at the behest of Lungu, who is trying to drive Zambia back toward the kind of authoritarian government that has bedeviled it since independence from Britain in 1964.

During the height of the Cold War, Zambia had some strategic importance to the United States as a major producer of copper. Since then the economic fortunes of Zambia have risen and fallen with the copper price and attempts to diversify the economy have faltered. Tourism, dependent largely on the Victoria Falls and recreation on the world’s largest water impoundment, the Kariba Dam, called Lake Kariba, is faltering because of persistent drought leading to historical low flows in the Zambezi River.

Over the years Zambia has done better than, say, neighbor Zimbabwe, where bad government has destroyed the once-prosperous country and reduced it to a kind of subsistence existence without so much as a national currency. Zambia has never been as rich as Zimbabwe was at its independence in 1980, but it has managed somehow to survive.

In his statement, Foote saluted the warmth and friendliness of the Zambian people. In my experience, he is right. I lived in Zambia for a while many years ago and the people were tops. As a very young journalist, I interviewed Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda, when he was a young independence leader. He is now 95.

Kaunda, too, was to have his problems with diplomats. He curbed the press, but he loved press conferences and he ordered the diplomatic corps to show up and ask friendly questions. That did not go too well either.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C. He grew up in what was then called Southern Rhodesia, a British colony, but is now called Zimbabwe.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Llewellyn King: Perhaps the queen likes Trump

LONDON

I have a secret. I can’t verify it, but I can share it. It’s this: I think that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II likes President Trump.

Honestly, I’ve been studying video of them together and despite what the press here thinks, I believe she likes him. She’s amused by him. Poor woman, she deserves some amusement; she deserves some international figure who isn’t fazed by the honor of meeting the world’s most important monarch.

Consider what a relief it must be for the queen to see someone as unlearned in matters of protocol as Trump. Legions of heads of state and heads of government have leaned low over her hand while their wives have curtsied, often clumsily despite hours of practice. What a trial all this must be to a woman of 93, who has been subject to this since her ascent as queen, in 1952.

Elizabeth must be the hardest-working woman on earth. She's met thousands of stiff, boring men, day after day. She's been sung to by countless legions of well-scrubbed schoolchildren and has endured thousands of hours of native dancing, from the Maoris of New Zealand to the Ndebele of Zimbabwe.

The mere knowledge that you're to go to Buckingham Palace produces a kind of paralysis in most. The honor of the thing with the ghastly small talk that they feel they must be ready to speak can only make for a tedium that defies imagination. From great generals like America’s Dwight Eisenhower to such mass murderers as Romania’s Nicolae Ceausescu, each has taken the royal paw and whispered idiocies about the weather in London that day.

No one -- except possibly Trump -- meets the queen without hours of preparation. How to shake hands, how to check that the great moment hasn’t caused you to break out in an embarrassing sweat. Those clothes! Is it to be rented morning wear (Who owns that?) or something less formal. Has your wife ordered correctly? Nothing off-the-peg or too high-fashion -- except for Melania who, on this trip, appeared to be working as an haute couture model.

There’s evidence that the queen, after a long life of boredom, finds some relief in two American exceptions: Meghan Markle, the wife of her grandson, Prince Harry, and Trump.

Would the queen, one wonders, have opened Buckingham Palace to NATO for a reception if she hadn’t liked Trump who, for good or otherwise, was the man of the hour: the mad cousin, if you will, expected to metaphorically blow on his soup and say awful things, but still the most important member of the family.

I think that the gauche American president was a little reward for the hard-working Windsor (the family name, in case you’ve forgotten) who was dealing with yet another family crisis: An American woman has accused the queen’s son, Prince Andrew, of having sex with her when she was just 17 years old.

The rest of the NATO summit was all downhill. Trump left early when the media published and broadcast pictures of others at the summit chortling about him, including his host, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, the queen’s daughter Princess Anne and – oh, the villainy! -- Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who regaled a small group with gestures, showing how Trump’s aides were open-mouthed at what their boss had said at his press conference.

Anne was already in bad favor with her mother for not joining the receiving line at the palace along with the her more dutiful brother, Prince Charles, and his wife, Camilla.

Those who made merry of Trump’s antics might beware. He’s a counterpuncher (which means vindictive) and someone already critical of NATO. A chortle at Buckingham Palace might irreparably harm the defense alliance.

Maybe the queen will have reason to regret her hospitality and warmth toward the boredom-breaking American president. Her majesty won’t then be amused any longer.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Read this column on:

InsideSources

White House Chronicle

David Warsh: Take Trump's attempted extortion to the electorate

Pennsylvania Station in the 1910s. It was torn down in 1963.

There was a time when New York City had the gateway it deserved.

Demolished more than half a century ago, the former Pennsylvania Station by McKim, Mead & White was hardly the first great building in town to face the wrecking ball. The Lenox Library by Richard Morris Hunt and the old Waldorf-Astoria by Henry Hardenbergh on Fifth Avenue also came down. For generations, New Yorkers embraced the mantra of change, assuming that what replaced a beloved building would probably be as good or better.

The Frick mansion, by Carrère and Hastings, replaced the Lenox Library. The Empire State Building replaced the old Waldorf.

Then, a lot of bad Modern architecture, amid other signs of postwar decline, flipped the optimistic narrative.

From “Penn Station Was an Exhalted Gateway. Here’s How It Became a Reviled Rat’s Maze,’’ by Michael Kimmelman, The New York Times. April 29, 2019

You hear a lot these days about narrative. I don’t know anyone better on the topic, at least in the world of economics that I follow, than Mary Morgan, of the Department of Economic History at the London School of Economics.

Morgan is an expert because she is an accomplished practitioner. The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think (Cambridge, 2012), is based on eight scrupulous case studies of how mathematical models gradually supplanted words in workaday technical economics. The philosophical examination established Morgan among the world’s leading historians of economic thought.

A related group research project on the nature of evidence produced an edited volume of essays, How Well Do Facts Travel? The Dissemination of Reliable Knowledge (Cambridge, 2011). Since 2016, she has led a scholarly European Commission research project on “Narrative in Science.” Elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 2012, she served four years as its vice president for publications.

From Morgan’s introduction to a special issue of Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, “Narrative knowing is most immediately relevant when the scientific phenomena involve complexity, variety, and contingency….”

From her essay in the same issue, “What narratives do above all else is create a productive order amongst materials with the purpose to answer why and how questions.” Their power is illustrated in novels, she writes; their question-answering and problem-solving capabilities are most evident in detective stories.

I’ve been reading Morgan in connection with an economics story. But I thought of her in connection with events these last two weeks in Washington, D.C.

I had no time to listen to the impeachment hearings last week. I gathered from the news reports I read that the testimony was damning.

Republicans seem to believe that the attempted extortion of the government of Ukraine was, as Wall Street Journal editorial columnist Daniel Henninger put it, nothing more than Donald Trump’s “umpteenth ‘norms’ violation.” The Ukraine caper wasn’t a constitutional crisis. But is clearly was a crime. The fake Ukraine election-interference story was even more shocking.

Therefore it seems right to bring the case. Still, it doesn’t seem sufficient reason to remove the president from office at a time when an election is at hand, especially since a significant minority of voters seem not to think the president did anything out of the ordinary. Impeachment forces Republicans candidates to clarify their views – and to go on clarifying them for years to come.

The thing to do is to take it to the electorate. The attempted extortion was an anecdote – a short, grimly entertaining account of something that Trump did, an illustration of a good tradition torn down. But it is only one anecdote of many.

Next year’s election is the key event. The order of American presidents is among the most fundamental narratives of the history of the United States. Let the House leaders draft the impeachment articles, the membership pass quickly them, and the Senate debate. Move on to the Democratic Party primaries.

The Moynihan-conceived plan to convert the Farley Postal Building across the street across the street from Penn Station (also designed by McKim, Mead & White, into a new train hall is going forward. But only Donald Trump’s defeat next year can begin to flip the pessimistic narrative of the nation.od

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somervillle, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Llewellyn King: Will Democrats break their Christmas present?

Historical sea level reconstruction and projections up to 2100 published in January 2017 by the U.S. Global Change Research Program for the Fourth National Climate Assessment.

The Democrats have no need to fret about what they’ll get for Christmas this year. Their worry shouldn’t be the gift, but rather how they choose to open it.

The gift is global warming.

Don’t call it climate change; that fuzzies the issue. Call it for what it is: global warming. It is heat that is melting the polar ice cap, stripping Greenland of its ice sheet, opening Arctic shipping lanes and sinking Venice, one of the jewels of civilization.

Global warming isn’t an existential threat but a real problem that is here, real and now. It is happening today, this hour, this minute, this second.

President Trump has taken his stand. He said of the rising seas and wild weather, which are science-supported evidence of global warming, “I don’t believe it.”