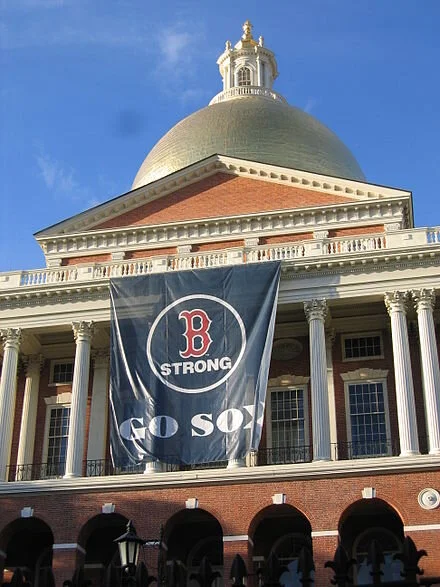

A Hub of fanaticism

The Massachusetts State House displaying a banner in honor of the Red Sox's 2013 World Series appearance

“Boston is so laced with jerseys that you can be dressed head to toe in team apparel and no one will look twice. ‘‘

— David Walton, an actor and Boston native

Read more: https://www.wiseoldsayings.com/boston-quotes/#ixzz6KAmmfWZK

'At the feet of my hatred'

Marina in Stamford, Conn.

Buds on an oak tree. The species is one of the most common in southern New England

“Connecticut lays itself at the feet of my hatred.

The accent the Ischians use when not among themselves

does not point to but is Connecticut.

Red by oak. Blue by May.

White by sailcloth

jacketed on the booms in the marinas.

— From “One Connecticut,’’ by D.H. Tracy

Chris Powell: In the COVID-19 crisis, both sides threaten liberty; block those raises!

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Fortunately it was just another brief bout of MAGA-lomania the other day when President Trump declared that he would decide when states lift the health and safety restrictions they have imposed because of the virus epidemic. Several governors, including Connecticut's Ned Lamont, quickly protested that the Constitution reserves such power to the states. New York's Andrew Cuomo protested most colorfully, noting that the president is not a king.

But amid the epidemic constitutional rights are under assault by many elected officials throughout the country, Democratic as well as Republican. Several states are imposing or threatening to impose penalties on religious services that exceed recommended attendance levels, in spite of the First Amendment's guarantees of freedom of religion and assembly.

Connecticut isn't immune to such assaults. Lamont skirted the Second Amendment's guarantee of the right to bear arms by telling gun shops they could remain open only by appointment. State Attorney General William Tong has joined other state attorneys general in a lawsuit to suppress publication of plans for guns that can be made by 3D printers, and this week Tong urged the federal government to criminalize such publication -- that is, to criminalize mere information, as if the First Amendment doesn't also guarantee speech and press rights.

The objection to making guns with 3D printers is that they can be manufactured without legally required serial numbers. But any gun can be, and the designs for many weapons have been published. If mere information can be criminalized in regard to gun designs, it can be criminalized for whatever government doesn't want people to know. Of course there would be no end to that.

Trump can't tell states when to lift their health and safety restrictions. But neither can Tong tell people what they can publish and read, no matter how politically incorrect it may be.

xxx

Yankee Institute investigative journalist Marc Fitch this week reminded Connecticut that as of July 1 state government employees are due to start receiving raises costing at least $353 million a year. Fitch noted that Democratic governors in New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia are suspending state employee raises until the immense financial cost of the epidemic can be calculated.

So the Yankee Institute urged Governor Lamont to suspend the raises as well, but it's not clear that he can. For the raises are part of state government's current contract with the state employee union coalition, one of the many lamentable legacies of Connecticut's previous administration, and the federal Constitution forbids states from making any law impairing the obligation of contracts.

It's bad enough that the wages and benefits of state and municipal government employees have been completely protected even as the governor's own orders have thrown tens of thousands of people out of work in the private sector. For state government to pay raises while unemployment explodes in the private sector and state tax collections collapse would be crazy, more proof that nothing matters more to state government than the contentment of its own employees, whose unions long have controlled the majority political party.

But the governor is not helpless here. Using his emergency powers he could suspend collective bargaining for state employees and binding arbitration of their contracts for six months at a time or "modify" those laws to strengthen public administration during the emergency. He should do so, for as the treacle on television says, we're all supposed to be in this together.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

David Warsh: Getting beyond despair: Three prongs to address climate change

— By Adam Peterson

Flooding caused by Super Storm Sandy in Marblehead, Mass., on Oct. 29, 2012

From economicprincipals.com

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weighed down by not knowing what to expect of the coronavirus timetable, I spent a day last week reading about climate change. Specifically, I read Three Prongs for Prudent Climate Policy, by Joseph Aldy and Richard Zeckhauser, both of Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

Paradoxically I came away feeling better. Grim though the situation they describe is, theirs is anything but a counsel of despair.

For three decades, advocates for climate change policy have simultaneously emphasized the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and provided unrealistic reassurances of the feasibility of doing so. It hasn’t worked out, say Alby and Zeckhauser.

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 imposed binding commitments on industrial nations to reduce emissions below 1990 levels in a decade. They exceeded them. Even so, global carbon dioxide emission grew 57 percent over the same ten years, because developing nations hadn’t joined the accord.

So the Paris Agreement of 2015 established “pledge and review” commitments by from virtually every nation in the world, designed to prevent warming of more than 2 degrees centigrade by 2030. But even if every country honors its pledge, the policy is unlikely to succeed in meeting the target, say Aldy and Zeckhauser,

That’s because what’s already in the atmosphere is a stock, not a flow. From the pre-industrial period to 1990, carbon dioxide concentration increased by about 75 parts per million. Since 1990, CO2 has increased by another 55 parts per million, and despite the agreements, the rate of increase is apparently accelerating.

Meanwhile, global temperature have increased around half a degree centigrade in the last 30 years. They are likely to rise faster in the years ahead. Storms, droughts, floods, fires, melting will increase. Mass migrations in response to these weather events have barely begun.

So, the authors say, after 30 years of single-minded stress on emission reductions in climate change discourse, two other policy prongs are urgently needed.

One of these headings, adaptation, is well-known and uncontroversial, except that it costs a lot in more complicate applications than in simple adjustments. Moving heating plants from basements to upper stories so that equipment is not damaged by flooding is simple and relatively cheap. Sea barriers and storm gates to protect coastal cities are another. The sea wall to protect the Venice lagoon is almost finished, but the Army Corps of Engineers plan to protect New York City would take 25 years to construct.

The other strut, amelioration, is considerably less discussed, mainly for fear of the ease with which the remedy may be embraced, once the cost differences are better understood. “Solar radiation management” means putting a sunscreen into the sky – most likely sulfur particles injected into the upper atmosphere by specially built airplanes. Major volcanic eruptions over the centuries have proven that the principle will work, though myriad details of its practical application are hazy. What’s clear is that so-called “geo-engineering” would cost considerably less than emissions reduction or adaptation, especially if time were of the essence.

The only place I see radiation management brought up regularly in the things I read is in Holman Jenkins’s twice-a-week column in the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal. The other day Jenkins noted Amazon’s Jeff Bezos’s intention to spend $10 billion to fight climate change. Don’t spend it touting nuclear power, Jenkins advised; Bill Gates is already working on that. And never mind carbon taxation; that must come, if it comes, from the Left. Instead, why not atmospheric aerosol research?

Right though Jenkins may be about the possibilities of solar-radiation mitigation, he is preaching to those ready to be converted. That’s why I was interested in the Aldy-Zeckhauser paper: they are several steps closer to the mainstream. Aldy served as the Special Assistant to the President for Energy and Environment in 2009-2010. Zeckhauser works in in the tradition of tough-minded cooperation pioneered by his mentor, the policy intellectual (and Nobel laureate) Thomas Schelling.

But if we can’t handle a virus, what hope is there of devising effective policies against climate change? That’s just the point: we can handle a virus. It just takes a year, or, probably, two. The problem of arresting global warming is much more difficult, but if you believe the science, there can be no doubt that disastrous events will sooner or later cause public opinion around the world to come around

Wisdom begins with the recognition that there are three policy prongs with which to address the problem of greenhouse gases, not just one. Slowing the effects of carbon dioxide emissions – while continuing to slow emissions themselves – turns on the next election, and the two or three elections after that.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

web design by PISH P

Monumental way to start and end a train trip

Back when the public wanted grandeur in its infrastructure, Boston’s North Station in 1910. The building was opened in 1893 and was torn down in 1928.

The 'irresistibly touching' Concord River

The iteration of the Old North Bridge over the Concord River in 1900, a bit before Henry James’s visit. The original bridge (see picture below) was the site of the Battle of Concord, on April 19, 1775, at the opening of the American Revolution. The bridge was frequently replaced in Colonial times because of flooding.

“I hung over Concord River then as long as I could, and recalled how Thoreau, Hawthome, Emerson himself, have expressed with due sympathy the sense of this full, slow, sleepy, meadowy flood, which sets its pace and takes its twists like some large obese benevolent person, scarce so frankly unsociable as to pass you at all. It had watched the Fight, it even now confesses, without a quickening of its current, and it draws along the woods and the orchards and the fields with the purr of a mild domesticated cat who rubs against the family and the furniture. Not to be recorded, at best, however, I think, never to emerge from the state of the inexpressible, in respect to the spot, by the bridge, where one most lingers, is the sharpest suggestion of the whole scene—the power diffused in it which makes it, after all these years, or perhaps indeed by reason of their number, so irresistibly touching.’’

— Henry James, in The American Scene (1907)

A 1775 drawing by Amos Doolittle of the engagement at the North Bridge based on witness accounts his own inspection of the bridge

The present bridge, built in 1956, is an approximate replica of the bridge, built in 1760, that stood in the battle.

Stretches of the Concord River are gorgeous.

Drawn to power

“Power: Chatham on Cape Cod” (archival pigment print), by Bobby Baker. Copyright Bobby Baker Fine Art Photography

Lindsey Gumb: Pandemic means now is the time to widen access to learning materials

Open Access logo, originally designed by Public Library of Science

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BRISTOL, R.I.

Residential college and university campuses across New England abruptly closed their doors last month during the COVID-19 outbreak, and while some schools were in session and students were asked to vacate, many others were on spring break and students were asked not to return. In both situations, students found themselves at home or in new environments where they waited to see how their education would progress online and remotely.

Among many variables associated with the chaos and stress of the pandemic, a lack of direct access to learning materials like textbooks has arisen as one of the major roadblocks to student learning in the era of COVID-19.

As a nation, we have continued to observe a sharp rise in textbook prices since 1977, which leaves many students enrolled at postsecondary institutions, public or independent, unable to afford the required learning materials for their courses. As a Band-Aid solution, students often rely on borrowing a copy of the book or material from a classmate or the campus library—options that became obsolete overnight when campuses closed and we entered this new world of social distancing and online learning and course delivery. When access barriers to learning materials like textbooks exist, either financial or circumstantial (as in the case of COVID-19), we know that students’ grades and academic trajectory suffer, and ultimately institutional retention can take a hit. Having been laid off from part-time jobs, denied unemployment and mostly left out of the COVID-19 stimulus package, college students have enough stress and anxiety right now—the last thing they should be worrying about is not having access to their textbooks. Enter OER (Open Educational Resources).

Are those “solutions” really OER?

Textbook prices are only part of the access barrier issue. As teaching and learning shifts fully online during the COVID-19 pandemic, educators have been forced to more closely consider and analyze how copyright restrictions set by publishers may limit their students’ access to these essential learning materials. The last few weeks have shown more than ever why true OER have significant value in ensuring students have access to their learning materials, because they are free and have licenses that allow for reuse and retention without limitation. This is not the case with publisher content like textbooks or the many online learning “solutions” they offer in which access is only semester-long, not in perpetuity like OER. These materials, even if offered free of charge by the publisher right now during the pandemic, will inevitably shuffle back behind a paywall at the end of the semester, disproportionately harming students affected by conditions out of their control brought on by COVID-19 (displacement, illness, caretaking responsibilities, etc.) and who may need to retake courses and need access to the materials again.

OER providers such as Lumen Learning, Saylor Academy and the Open Course Library have full online courses ready to be adopted and easily integrated into learning management systems with very little effort needed by faculty members. The content is customizable. Students have immediate, free access, and unlike publisher content, access to the content won’t be lost when the semester ends.

OER, however, is not and cannot be the blanket solution for ensuring students have access to their learning materials during a time like this. In fact, we’ve heard stories from across the region of institutions handing out technology and hotspots to help address the digital inequities that exist for so many students. The Community College of Rhode Island awarded nearly 700 students grants to acquire computers or gain internet access with an additional 61 iPads distributed to students who requested them. OER are primarily digital resources, and students need an Internet connection to at least initially download the resource onto a device. While they are free, OER will still require other institutional support systems to make sure our students have everything they need to equitably participate in their remote learning.

Freeing information

This isn’t just about students’ access to textbooks. Also at issue is the current publishing industry’s suppression of access to information. SPARC (the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Research Coalition) defines Open Access (OA) as the “free, immediate, online availability of research articles coupled with the rights to use these articles fully in the digital environment. OA ensures that anyone can access and use these results—to turn ideas into industries and breakthroughs into better lives.” The American Library Association and academic librarians have long been advocating for OA policies that remove barriers to scholarly, peer-reviewed research that are typically only accessible to those who have an active academic affiliation such as faculty, students, staff at colleges and universities. Institutions pay outrageous annual subscription fees on behalf of their community members to access this content, and those who have no affiliation pay a fee to access each article.

We’ve seen recently that many news organizations, such as The New York Times, Bloomberg News and The Atlantic, have removed the paywall on articles pertaining to COVID-19 so that the public has access to pertinent information that could potentially be lifesaving. OA fosters the same spirit except, instead of news, the information is peer-reviewed research, often generated by researchers through federal grant funding, aka “your tax dollars.” New research, particularly in the medical field, can have an immediate impact on public health. If that information is behind a paywall, only the privileged will have access to that potentially life-saving research. In January, a Washington Post article, Scientists are unraveling the Chinese coronavirus with unprecedented speed and openness, strongly illustrated this point. The genome sequence of the coronavirus was posted in an open access repository for genetic information and literally overnight, Andrew Mesecar, a professor of cancer structural biology at Purdue University, got a hold of it and started analyzing the DNA sequence. The immediate domino effect of having this information freely available has led to an international collaboration of scientists working together to aid in this public health crisis. Victoria Heath and Brigitte Vézina’s recent blog post for Creative Commons, Now is the time for Open Access Policies—here’s why, reminds us that “we must cooperate effectively to respond to an unprecedented global health emergency. The mantra “when we share, everyone wins” applies now more than ever.”

Robin DeRosa, director of the Open Learning & Teaching Collaborative at Plymouth (N.H.) State University, notes “there is a link between public health and Open. The open sharing of research and data can help us quickly collaborate to find medical solutions. Open pedagogy can help us involve our students in our fields’ responses to the pandemic and remind us that the digital divide can complicate remote learning. And OER can remove barriers for students and faculty who need to shift to more ubiquitously available resources. Open is about public infrastructure more than it is a set of free textbooks.”

For more on the basics and supporting research of OER, check out Open Matters: A Brief Intro and see additional resources at the Open Education and Open Educational Resources page on NEBHE’s website.

Lindsey Gumb is an assistant professor and the scholarly communications librarian at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, where she has been leading OER adoption, revision and creation since 2016, focusing heavily on OER-enabled pedagogy collaborations with faculty. She co-chairs the Rhode Island Open Textbook Initiative Steering Committee and the is Fellow for Open Education at the New England Board of Higher Education. She was awarded a 2019-20 OER Research Fellowship to conduct research on undergraduate student awareness of copyright and fair use and open licensing as it pertains to their participation in OER-enabled pedagogy projects.

(Editor’s note: New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is a former member of The New England Board of Higher Education’s Editorial Advisory Board.)

Clock tower at Roger Williams University, in Mount Hope Bay

— Phtoto by Notyourbroom

'Sanity of stone'

The Barre (Vt.) World War 1 Memorial, "Youth Triumphant", by sculptor C. Paul Jennewein. The Barre area is known for its granite and marble industries.

“There under elms in glacial light

Survival forced me to atone:

The heart exchanged its rich excess

For starker sanity of stone.’’

— From “Sojourn in Vermont,’’ by Israel Smith

The Rock of Ages quarry, in Barre, Vt.

— Photo by Mfwills

Hope and doubt on the beach

On Westhampton Beach, on Long Island

— Photos by Jacob Aaron Schiffman

Phil Galewitz: Harvard study sees social distancing maybe extending into 2022

Contemporary engraving of Marseille during the Great Plague of Marseilles in 1720–1721

As New York, California and other states begin to see their numbers of new COVID-19 cases level off or even slip, it might appear as if we’re nearing the end of the pandemic.

President Donald Trump and some governors have pointed to the slowdown as an indication that the day has come for reopening the country. “Our experts say the curve has flattened and the peak in new cases is behind us,” Trump said Thursday in announcing the administration’s guidance to states about how to begin easing social distancing measures and stay-at home orders.

But with the national toll of coronavirus deaths climbing each day and an ongoing scarcity of testing, health experts warn that the country is nowhere near “that day.” Indeed, a study released this week by Harvard scientists suggests that without an effective treatment or vaccine, social distancing measures may have to stay in place into 2022.

Kaiser Health News spoke to several disease detectives about what reaching the peak level of cases means and under what conditions people can go back to work and school without fear of getting infected. Here’s what they said.

It’s Hard To See The Peak

Health experts say not to expect a single peak day — when new cases reach their highest level — to determine when the tide has turned. As with any disease, the numbers need to decline for at least a week to discern any real trend. Some health experts say two weeks because that would give a better view of how widely the disease is still spreading. It typically takes people that long to show signs of infection after being exposed to the virus.

But getting a true reading of the number of cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, is tricky because of the lack of testing in many places, particularly among people under age 65 and those without symptoms.

Another factor is that states and counties will hit peaks at different times based on how quickly they instituted stay-at-home orders or other social distancing rules.

“We are a story of multiple epidemics, and the experience in the Northeast is quite different than on the West Coast,” said Esther Chernak, director of the Center for Public Health Readiness and Communication at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Also making it hard to determine the peak is the success in some areas of “flattening the curve” of new cases. The widespread efforts at social distancing were designed to help avoid a dramatic spike in the number of people contracting the virus. But that can result instead in a flat rate that may remain high for weeks.

“The flatter the curve, the harder to identify the peak,” said William Miller, a professor of epidemiology at Ohio State University.

The Peak Does Not Mean The Pandemic Is Nearly Over

Lowering the number of new cases is important, but it doesn’t mean the virus is disappearing. It suggests instead that social distancing has slowed the spread of the disease and elongated the course of the pandemic, said Pia MacDonald, an infectious disease expert at RTI International, a nonprofit research institute in North Carolina. The “flatten the curve” strategy was designed to help lessen the surge of patients so the health care system would have more time to build capacity, discover better treatments and eventually come up with a vaccine.

Getting past peak is important, Chernak said, but only if it leads to a relatively low number of new cases.

“This absolutely does not mean the pandemic is nearing an end,” MacDonald said. “Once you get past the peak, it’s not over until it’s over. It’s just the starting time for the rest of the response.”

What Comes Next Depends On Readiness

Although Trump said the nation has passed the peak of new cases, health experts cautioned that from a scientific perspective that won’t be clear until until there is a consistent decline in the number of new cases — which is not true now nationally or in many large states.

“We are at the plateau of the curve in many states,” said Dr. Ricardo Izurieta, an infectious disease specialist at the University of South Florida. “We have to make sure we see a decline in cases before we can see a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Even after the peak, many people are susceptible.

“The only way to stop the spread of the disease is to reduce human contact,” Chernak said. “The good news is having people stay home is working, but it’s been brutal on people and on society and on the economy.”

Before allowing people to gather in groups, more testing needs to be done, people who are infected need to be quarantined, and their contacts must be tracked down and isolated for two weeks, she said, but added: “We don’t seem to have a national strategy to achieve this.”

“Before any public health interventions are relaxed, we better be ready to test every single person for COVID,” MacDonald said.

In addition, she said, city and county health departments lack staffing to contact people who have been near those who are infected to get them to isolate. The tools “needed to lift up the social distancing we do not have ready to go,” MacDonald said.

You’re Going To Need Masks A Long Time

Whether people can go back out to resume daily activities will depend on their individual risk of infection.

While some states say they will work together to determine how and when to ease social distancing standards to restart the economy, Chernak said a more national plan will be needed, especially given Americans’ desire to travel within the country.

“Without aggressive testing and contact tracing, people will still be at risk when going out,” she said. Social gatherings will be limited to a few people, and wearing masks in public will likely remain necessary.

She said major changes will be necessary in nursing home operations to reduce the spread of disease because the elderly are at the highest risk of complications from COVID-19.

Miller said it’s likely another surge of COVID-19 cases could occur after social distancing measures are loosened.

“How big that will be depends on how long you wait from a public health perspective [to relax preventative measures]. The longer you wait is better, but the economy is worse off.”

The experts pointed to the 1918 pandemic of flu, which infected a quarter of the world’s population and killed 50 million people. Months after the first surge, there were several spikes in cases, with the second surge being the deadliest.

“If we pull off the public health measures too early, the virus is still circulating and can infect more people,” said Dr. Howard Markel, professor of the history of medicine at the University of Michigan. “We want that circulation to be among as few people as possible. So when new cases do erupt, the public health departments can test and isolate people.”

The Harvard researchers, in their article this week in the journal Science, said their model suggested that a resurgence of the virus “could occur as late as 2025 even after a prolonged period of apparent elimination.”

Will School Bells Ring In The Fall?

Experts say there is no one-size-fits-all approach to when office buildings can reopen, schools can restart and large public gatherings can resume.

The decision on whether to send youngsters back to school is key. While children have been hospitalized or killed by the virus much less frequently than adults, they are not immune. They may be carriers who can infect their parents. There are also questions of whether older teachers will be at increased risk being around dozens of students each day, MacDonald said.

Another factor: The virus is likely to re-erupt next winter, similar to what happens with the flu, said Jerne Shapiro, a lecturer in the University of Florida Department of Epidemiology.

Without a vaccine, people’s risk doesn’t change, she said.

“Someone who is susceptible now is susceptible in the future,” Shapiro said.

Experts doubt large festivals, concerts and baseball games will happen in the months ahead. California Gov. Gavin Newsom endorsed that view Tuesday, telling reporters that large-scale events are “not in the cards.”

“It’s safe to say it will be a long time until we see mass gatherings,” MacDonald said.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News journalist (pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz)

Cape's mild countenance

Dunes on Sandy Neck on Cape Cod.

“Although it can be violent and fierce in a gale, or inscrutable and even threatening when shrouded in fog, the familiar countenance of Cape Cod is general and moderate, even touchingly vulnerable, like a set of cherished features deteriorating in the rain of time.’’

-- Robert Finch, in The Cape Itself (1991)

Cranberry picking on Cape Cod in 1906

Marsh in Chatham

When it was much worse

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com:

It sometimes verges on soap opera but the drama World on Fire, the new British TV series about World War II now being broadcast on PBS, is often very effective at getting across what it might have been like for participants and onlookers in the 1939-45 conflict, which killed perhaps 60 million people. And it reminds viewers that what people in my parents’ and generation called “The War’’ was much worse than COVID-19. As teaching and knowledge of history continue to dangerously fade in America, we tend to present current or very recent events as far more momentous than much more important ones in the past. You can see this in how many people rank recent U.S. presidents as “greater’’ than obviously more important ones deeper in the past. Call it recency bias.

Whatever. The 1970s British documentary series The World at War remains, in my view, the best and most moving series on that horrific conflict. (The war created many of us – e.g., my parents met in a naval officers club in New York in 1943. They married late that year, and a few weeks later my father was on destroyer used to support the American landings at Anzio, Italy, where a long and epic battle took place.)

U.S. infantry landing at Anzio

N.E. responds: B.U. starts experimental COVID-19 treatment; companies give more relief money

The stunning Dana Hall-Integrated Science, Engineering, and Technology Complex at the University of Hartford. The university is offering free housing to first responders.

From our friends at The New England Council: (newenglandcouncil.com):

As our region and our nation continue to grapple with the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, The New England Council is using our blog as a platform to highlight some of the incredible work our members have undertaken to respond to the outbreak. Each day, we’ll post a round-up of updates on some of the initiatives underway among Council members throughout the region. We are also sharing these updates via our social media, and encourage our members to share with us any information on their efforts so that we can be sure to include them in these daily round-ups.

You can find all the Council’s information and resources related to the crisis in the special COVID-19 section of our website. This includes our COVID-19 Virtual Events Calendar, which provides information on upcoming COVID-19 Congressional town halls and webinars presented by NEC members, as well as our newly-released Federal Agency COVID-19 Guidance for Businesses page.

Here is the Friday, April 17, roundup:

Medical Response

Boston Hospitals Begin Using Experimental Treatment on COVID-19 Patients – Doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center have begun using hydroxychloroquine, the now-famous anti-malarial drug, as a potential treatment on COVID-19 patients. Mass General is sponsoring a controlled study with the drug that plans to test patients around the country in order to assess its effectiveness beyond initial, anecdotal reports of success. The Boston Globe has more.

Brandeis University, Boston University Collaborate on Coronavirus Research – Researchers at Brandeis University and Boston University are working together to study how the coronavirus penetrates cells and causes infection. Labs at the two universities are working to visualize how COVID-19 affects humans at a cellular level to better understand how it operates and to measure the effectiveness of varying antibodies in combating the virus. Read more.

MilliporeSigma Prepares for Large-Scale Production of Potential Vaccine – MilliporeSigma, in partnership with The Jenner Institute, has announced the foundation for large-scale production of a vaccine candidate. With the potential treatment in clinical trials, the partnership will ensure that the manufacturing and distribution processes—which would normally take up to a year—can be ramped up should the vaccine prove effective. Read the press release here.

Economic/Business Continuity Response

University of Hartford Providing Free Housing to First Responders – In an effort to support those working on the front lines of the pandemic, the University of Hartford has announced free temporary housing for 200 first responders. The school’s residence halls will be used to house the essential workers who are self-isolating while they work to combat the virus. WTNH has more.

Tufts Health Plan Offers Healthcare Service Information Hub – To provide its members with information on available resources during the pandemic, Tufts Health Plan has created a resource page outlining what services are available to them from the insurance provider. The page addresses a variety of concerns and questions, such as the cost of testing and treatment, availability of telehealth services, and increased access to prescriptions.

Community Response

Stanley Black & Decker Launches $10 Million Relief Program – Manufacturer Stanley Black & Decker has launched a charitable outreach program, providing over $10 million to support populations most heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The program will support emergency relief funds for employees and families impacted by the crisis, as well as nonprofit organizations around the world. The company also plans to purchase 3 million face masks and additional protective equipment for essential workers in locations where it operates. The Hartford Business Journal has more.

Eversource Donates $1.2 Million to United Ways Agencies in New England – Eversource is hastening its annual donation of $1.2 million in New England to s in the region. The energy company will also donate funds to Connecticut’s statewide relief fund. Read more in The Hartford Business Journal.

UMass Medical School Produces Hand Sanitizer for Local Hospitals – At the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Medical School, students in the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences have begun producing hand sanitizer for hospitals in the area. The students have already produced almost 130 gallons in three days, and plan to make another 100 along with distributing their procedure to expedite production. Read more.

Stay tuned for more updates each day, and follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates on how Council members are contributing to the response to this global health crisis.

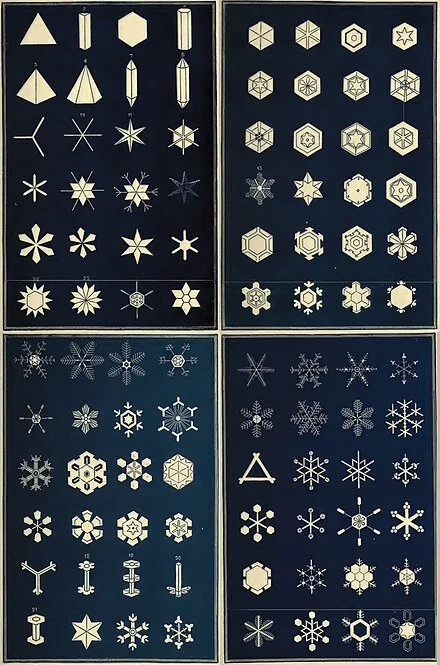

'Diversionary' weather

An early classification of snowflakes by Israel Perkins Warren (1814-92), an American Congregational minister as well as an editor and author. He lived in Connecticut and then Maine.

“A kind of counter-

blossoming, diversionary,

doomed, and like

the needle with its drop

of blood a little

too transparently in

love with doom, takes

issue with the season….’’

— From “Spring Snow,’’ by Linda Gregerson

The way we walk now

Oil and acrylic painting by student Amelia Katzen with Zhanna Cantor at New Art Center, Newton, Mass.

James Dempsey: With N.E. roots, The Dial became a Modernist monument

The first edition of the Modernist version of The Dial

SEE VIDEO AT BOTTOM

WORCESTER

When Scofield Thayer (picture at bottom) and James Sibley Watson put out their first issue of a radically restructured Dial magazine, at the beginning of 1920, the literati were unimpressed and indeed acidly disdainful. Ezra Pound called it “one of those mortuaries for the entombment of dead fecal mentality.” “It is very dull,” said T.S. Eliot, “just an imitation of The Atlantic Monthly with a few atrocious drawings reproduced.”

Those drawings were by poet and painter E.E. Cummings, who came in for more than his fair share of bashing. Robert Hillyer mocked his sketches of “trollops with their limbs spread wide apart” as well as the seven “awful” Cummings poems in the same issue, which included the now much-anthologized “Buffalo Bill’’.

“A pink thread of juvenility runs through it,” sniffed poet Conrad Aiken.

Be that as it may, writers were soon falling over each other in an undignified rush to get their work into the pages of this little magazine. All the above-mentioned critics appeared in The Dial in its first year and frequently thereafter, and the magazine went on to become arguably the most important of the magazines to promote and discuss those creative works that would come to be referred to, for better or worse, as “Modernist.”

The Dial published the works of writers and visual artists from 33 countries, many for the first time. Its scoops included T.S. Eliot's “The Waste Land’’ and "The Hollow Men"; E.E. Cummings's "in Just-"; W.B. Yeats's "The Second Coming"; Marianne Moore's "An Octopus"; Ezra Pound's “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley”; William Carlos Williams's "Paterson"; the first English translation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice; Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street,” and many others. The magazine also showcased such visual artists as Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Gustav Klimt, Georgia O'Keeffe, Gaston Lachaise and Egon Schiele, often bringing their work before a wide public for the first time. Its regular correspondents included such luminaries of the period as Eliot, Pound, Thomas Mann and Maxim Gorki. Criticism was provided by Edmund Wilson, Van Wyck Brooks and Gilbert Seldes. Philosophers Bertrand Russell and George Santayana were frequent contributors.

Scofield Thayer

Those who appeared on the contents page — always listed on the cover -- included 11 Nobel and 24 Pulitzer prize-winners, as well as five U.S. Poet Laureates. And the journal’s particular emphasis on modern visual art was important in creating New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Thayer, Watson and their editors, including Gilbert Seldes, Alyse Gregory and Marianne Moore, were undoubtedly judicious and far-sighted in their tastes. From this age of great magazines, Malcolm Cowley singled out The Dial under Thayer as “the best magazine of the arts that we have had in this country.”

Thayer and Watson knew exactly what kind of magazine they wanted. They kept the book-review section from the old Dial, but they dumped the politics and added art, fiction, essays and much more poetry. The goals were lofty: Thayer wanted to print what he felt was ahead of, and even outside of, its time, material that “would otherwise have to wait years for publication,” as well as work struggling to find an audience and that “would not be acceptable elsewhere.” But he was also astute enough to realize that the audience for such, though enthusiastic, was small. Further, he saw no reason to exclude from the magazine established authors who were still producing important work. W.B. Yeats and Joseph Conrad were not yet “wholly dead,” he drolly pointed out.

Throughout its almost 10 years of existence, the avant-garde persistently criticized the magazine for being too staid, and old-school aesthetes denounced it for being too modern. This careful balancing of material, though, was in fact one of the aims of The Dial -- to promote and validate the work of younger writers and artists by their proximity to those who had more secure reputations. This leveling carried over into the fees paid by the magazine: Rates for all contributors, famous or not, were the same.

By its editors cannily blending the avant-garde with excellent but more established forms of visual art and literature, The Dial was transformed from a ploddingly progressive publication into a must-read for writers and artists of all stripes.

Thayer and Watson’s Dial was based in New York, but its New England pedigree was thorough. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Concord essayist, philosopher and poet, launched the journal in 1840 as an outlet for Transcendentalist writing. Emerson, of Concord, Mass., hired the brilliant Margaret Fuller of Cambridge to help edit the magazine at $200 a year, a salary she never received. Amos Bronson Alcott called it “a free journal for the soul.’’

By the time that Emerson ended the magazine, in 1844, it had published Emerson, Fuller, John Sullivan Dwight, George Ripley, Samuel Gray Ward, William Ellery Channing, Frederic Henry Hedge, James Russell Lowell and Henry David Thoreau. In 1860, minister, abolitionist and Harvard graduate Moncure Daniel Conway launched a new version in Cincinnati. Conway managed to win Emerson’s blessing for the enterprise but was never able to persuade him to write for the magazine. It ceased publication after a year. Francis Fisher Browne, who was born in South Halifax, Vt., had more success with his Chicago Dial, which he started in 1880. It was slowly transformed from a somewhat conservative and apolitical journal into a Midwestern redoubt of culture and progressive politics. Browne had no college education. After high school, in 1862 he enlisted in the Forty-sixth Massachusetts Volunteers, which fought at the battles of Kinston, Whitehall and Goldsboro.

Apart from Watson, who was from Rochester, N.Y., all the above-named principals of the magazine, from Emerson on, were born in New England. (Thayer was a native of Worcester.) Most, including Watson, attended Harvard. Fuller, who in her time was considered the best-read person in New England, was the first woman allowed to use the library at Harvard College.

Little magazines have usually faced many threats to their existence, one of the main ones being lack of capital. For The Dial, this was never a problem. Thayer and Watson didn’t expect to make a profit or even to break even, and they constantly raided their personal fortunes to shovel money into the enterprise. Some years it cost them as much as $100,000, a not-so-small sum at the time. (By contrast, the first issue of William Carlos Williams’s Contact was run off on a donated mimeograph machine.) The principals of The Dial were by no means profligate with money—Thayer was notorious for quibbling about bills with tradesmen and others—but they both saw the journal as essentially coming under an umbrella of patronage. He bought the works of young artists, sent money to penurious writers -- James Joyce received $700 -- and established the annual Dial Award, a $2,000 gift for “service to letters”. And on some matters, expenses were never spared. When W.B. Yeats asked if he might change a line in “Leda and the Swan” after the issue had been sent to the printer’s, Thayer ordered the magazine containing the poem to be pulped and reprinted.

Nor did Thayer’s largesse stop there. E. E. Cummings was an ongoing charitable project, receiving $1,000 from Thayer to write a single poem, in addition to being paid for frequent contributions to the magazine, and even being given money to squire Thayer’s wife, Elaine, around New York City. (Soon after his marriage, Thayer became an acolyte of the Free Love movement and happily shared his wife, who had a child by Cummings, but that’s story for another time.)

Censorship was another threat. During the politically fraught times during and after The Great War and the Russian Revolution, the owners, editors, staff writers and contributors at little magazines, which tended to be politically and artistically radical, constantly ran the risk of being charged with everything from sedition to obscenity. In 1917, for example, staff members of The Masses were charged with violating the Espionage Act. They were eventually acquitted after two trials, but the magazine ceased publication. The editors of The Little Review famously were taken to court in 1922 and found guilty for publishing the allegedly obscene “Nausicaa” chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses, a decision that essentially banned the book in the United States.

The Dial navigated these tricky shoals of censorship by knowing just how far the envelope could be pushed without putting the magazine’s future at risk. The nervous business manager, Lincoln MacVeagh, constantly begged Thayer not to publish risqué art, which weakened sales on newsstands. When book publisher Henry Holt saw in The Dial a photograph of Gleb Derujinsky’s sculpture of Leda being ravished by a cygnified Zeus, he gasped “Why, it’s coitus” and promptly canceled his advertising in The Dial. And when John R. Sumner, head of The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, took umbrage at an article in the magazine attacking censorship, he was invited to submit a rebuttal. This he did in July 1921, and his piece made a very poor case, attacking “people in this country who like to bring forward something ‘foreign’ and hold it forth as an example of the way things should be done over here.’” The editors of that issue also made their own arch point by bookending Sumner’s piece with a George Moore sonnet in French and a Gaston Lachaise drawing of a naked and very buxom woman. At times, though, Thayer chose discretion over bravery; he vetoed reproduction of a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe as “commercially suicidal.” In some editorial decisions there was a cocking of the snoot at the authorities and in others the desire to ensure the future of the magazine. Thayer walked the line perfectly.

Thayer and Watson, both “Harvard men” from wealthy families, often clashed in their tastes. Thayer grew to abhor the productions of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, while Watson was a great champion of both. Thayer was strongly inclined toward the visual art and literature of Germany and Austria, while Watson was a thoroughgoing Francophile. Thayer’s dislike of his former friend T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” almost cost The Dial the first American publication of what would become the poem of the century, and it took all the diplomacy of Watson and the promise of the $2,000 Dial Award and other considerations to entice Eliot back on board. Other disagreements were often settled by veto, each man being allowed a single unchallenged rejection per issue. On a couple of occasions, Thayer threatened to step down from the magazine, but the two hung in together for six years before the 1926 mental breakdown that caused Thayer to leave the magazine and withdraw from public life. The Dial continued to publish until 1929, thus roughly bookending that miraculous decade of Modernism.

Thayer retired from the magazine and largely from public life in 1926. He had always been eccentric and suspicious of the people around him, but his mental condition deteriorated sharply in the mid-1920s, filling him with paranoia and a dread of being alone. He was eventually institutionalized and declared “an insane person”. For the rest of his long life (he died in 1982 at 92) he traveled among his homes with a nurse and servants.

Thayer had aspirations to be a poet, and constantly grumbled that his work on The Dial was preventing him from writing. But a century after he and Watson entered publishing, it is the magazine for which he is, and will always be, remembered.

James Dempsey, the author of The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer, is an essayist, novelist and a writing teacher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Take two and call me in the morning

“The Spheres,’’ by Kathleen Kucka, in her show “Slow Burn,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., through April 25 but not open to the general public. New Canaan is in affluent Fairfield Country, which has had a high incidence of COVID-19, a bit of it attributed to a big party in Westport, which turned out to be a big spreader.

But not exactly a pleasure dome

The Connecticut Capitol

“The gold dome of Hartford gone

At sunset starts the thought of one who did

Of the mind a gold dome make

Accessible to strangers. Kubla Khan….’’

— From “Passing East of Hartford,’’ by Ernest Kroll (1914-1994

xxx

Kubla Khan

Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment.

By Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round;

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Xanadu (here called Ciandu, as Marco Polo called it) on a French map of Asia made by Sanson d'Abbeville, geographer of King Louis XIV, dated 1650. It was northeast of Cambalu, or modern-day Beijing.