'Diversionary' weather

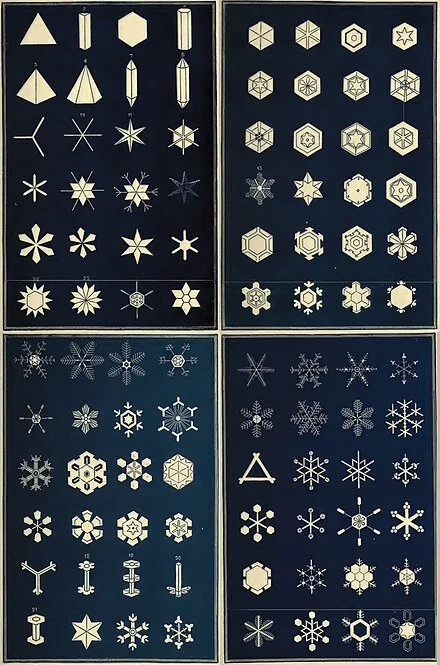

An early classification of snowflakes by Israel Perkins Warren (1814-92), an American Congregational minister as well as an editor and author. He lived in Connecticut and then Maine.

“A kind of counter-

blossoming, diversionary,

doomed, and like

the needle with its drop

of blood a little

too transparently in

love with doom, takes

issue with the season….’’

— From “Spring Snow,’’ by Linda Gregerson

The way we walk now

Oil and acrylic painting by student Amelia Katzen with Zhanna Cantor at New Art Center, Newton, Mass.

James Dempsey: With N.E. roots, The Dial became a Modernist monument

The first edition of the Modernist version of The Dial

SEE VIDEO AT BOTTOM

WORCESTER

When Scofield Thayer (picture at bottom) and James Sibley Watson put out their first issue of a radically restructured Dial magazine, at the beginning of 1920, the literati were unimpressed and indeed acidly disdainful. Ezra Pound called it “one of those mortuaries for the entombment of dead fecal mentality.” “It is very dull,” said T.S. Eliot, “just an imitation of The Atlantic Monthly with a few atrocious drawings reproduced.”

Those drawings were by poet and painter E.E. Cummings, who came in for more than his fair share of bashing. Robert Hillyer mocked his sketches of “trollops with their limbs spread wide apart” as well as the seven “awful” Cummings poems in the same issue, which included the now much-anthologized “Buffalo Bill’’.

“A pink thread of juvenility runs through it,” sniffed poet Conrad Aiken.

Be that as it may, writers were soon falling over each other in an undignified rush to get their work into the pages of this little magazine. All the above-mentioned critics appeared in The Dial in its first year and frequently thereafter, and the magazine went on to become arguably the most important of the magazines to promote and discuss those creative works that would come to be referred to, for better or worse, as “Modernist.”

The Dial published the works of writers and visual artists from 33 countries, many for the first time. Its scoops included T.S. Eliot's “The Waste Land’’ and "The Hollow Men"; E.E. Cummings's "in Just-"; W.B. Yeats's "The Second Coming"; Marianne Moore's "An Octopus"; Ezra Pound's “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley”; William Carlos Williams's "Paterson"; the first English translation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice; Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street,” and many others. The magazine also showcased such visual artists as Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Gustav Klimt, Georgia O'Keeffe, Gaston Lachaise and Egon Schiele, often bringing their work before a wide public for the first time. Its regular correspondents included such luminaries of the period as Eliot, Pound, Thomas Mann and Maxim Gorki. Criticism was provided by Edmund Wilson, Van Wyck Brooks and Gilbert Seldes. Philosophers Bertrand Russell and George Santayana were frequent contributors.

Scofield Thayer

Those who appeared on the contents page — always listed on the cover -- included 11 Nobel and 24 Pulitzer prize-winners, as well as five U.S. Poet Laureates. And the journal’s particular emphasis on modern visual art was important in creating New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Thayer, Watson and their editors, including Gilbert Seldes, Alyse Gregory and Marianne Moore, were undoubtedly judicious and far-sighted in their tastes. From this age of great magazines, Malcolm Cowley singled out The Dial under Thayer as “the best magazine of the arts that we have had in this country.”

Thayer and Watson knew exactly what kind of magazine they wanted. They kept the book-review section from the old Dial, but they dumped the politics and added art, fiction, essays and much more poetry. The goals were lofty: Thayer wanted to print what he felt was ahead of, and even outside of, its time, material that “would otherwise have to wait years for publication,” as well as work struggling to find an audience and that “would not be acceptable elsewhere.” But he was also astute enough to realize that the audience for such, though enthusiastic, was small. Further, he saw no reason to exclude from the magazine established authors who were still producing important work. W.B. Yeats and Joseph Conrad were not yet “wholly dead,” he drolly pointed out.

Throughout its almost 10 years of existence, the avant-garde persistently criticized the magazine for being too staid, and old-school aesthetes denounced it for being too modern. This careful balancing of material, though, was in fact one of the aims of The Dial -- to promote and validate the work of younger writers and artists by their proximity to those who had more secure reputations. This leveling carried over into the fees paid by the magazine: Rates for all contributors, famous or not, were the same.

By its editors cannily blending the avant-garde with excellent but more established forms of visual art and literature, The Dial was transformed from a ploddingly progressive publication into a must-read for writers and artists of all stripes.

Thayer and Watson’s Dial was based in New York, but its New England pedigree was thorough. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Concord essayist, philosopher and poet, launched the journal in 1840 as an outlet for Transcendentalist writing. Emerson, of Concord, Mass., hired the brilliant Margaret Fuller of Cambridge to help edit the magazine at $200 a year, a salary she never received. Amos Bronson Alcott called it “a free journal for the soul.’’

By the time that Emerson ended the magazine, in 1844, it had published Emerson, Fuller, John Sullivan Dwight, George Ripley, Samuel Gray Ward, William Ellery Channing, Frederic Henry Hedge, James Russell Lowell and Henry David Thoreau. In 1860, minister, abolitionist and Harvard graduate Moncure Daniel Conway launched a new version in Cincinnati. Conway managed to win Emerson’s blessing for the enterprise but was never able to persuade him to write for the magazine. It ceased publication after a year. Francis Fisher Browne, who was born in South Halifax, Vt., had more success with his Chicago Dial, which he started in 1880. It was slowly transformed from a somewhat conservative and apolitical journal into a Midwestern redoubt of culture and progressive politics. Browne had no college education. After high school, in 1862 he enlisted in the Forty-sixth Massachusetts Volunteers, which fought at the battles of Kinston, Whitehall and Goldsboro.

Apart from Watson, who was from Rochester, N.Y., all the above-named principals of the magazine, from Emerson on, were born in New England. (Thayer was a native of Worcester.) Most, including Watson, attended Harvard. Fuller, who in her time was considered the best-read person in New England, was the first woman allowed to use the library at Harvard College.

Little magazines have usually faced many threats to their existence, one of the main ones being lack of capital. For The Dial, this was never a problem. Thayer and Watson didn’t expect to make a profit or even to break even, and they constantly raided their personal fortunes to shovel money into the enterprise. Some years it cost them as much as $100,000, a not-so-small sum at the time. (By contrast, the first issue of William Carlos Williams’s Contact was run off on a donated mimeograph machine.) The principals of The Dial were by no means profligate with money—Thayer was notorious for quibbling about bills with tradesmen and others—but they both saw the journal as essentially coming under an umbrella of patronage. He bought the works of young artists, sent money to penurious writers -- James Joyce received $700 -- and established the annual Dial Award, a $2,000 gift for “service to letters”. And on some matters, expenses were never spared. When W.B. Yeats asked if he might change a line in “Leda and the Swan” after the issue had been sent to the printer’s, Thayer ordered the magazine containing the poem to be pulped and reprinted.

Nor did Thayer’s largesse stop there. E. E. Cummings was an ongoing charitable project, receiving $1,000 from Thayer to write a single poem, in addition to being paid for frequent contributions to the magazine, and even being given money to squire Thayer’s wife, Elaine, around New York City. (Soon after his marriage, Thayer became an acolyte of the Free Love movement and happily shared his wife, who had a child by Cummings, but that’s story for another time.)

Censorship was another threat. During the politically fraught times during and after The Great War and the Russian Revolution, the owners, editors, staff writers and contributors at little magazines, which tended to be politically and artistically radical, constantly ran the risk of being charged with everything from sedition to obscenity. In 1917, for example, staff members of The Masses were charged with violating the Espionage Act. They were eventually acquitted after two trials, but the magazine ceased publication. The editors of The Little Review famously were taken to court in 1922 and found guilty for publishing the allegedly obscene “Nausicaa” chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses, a decision that essentially banned the book in the United States.

The Dial navigated these tricky shoals of censorship by knowing just how far the envelope could be pushed without putting the magazine’s future at risk. The nervous business manager, Lincoln MacVeagh, constantly begged Thayer not to publish risqué art, which weakened sales on newsstands. When book publisher Henry Holt saw in The Dial a photograph of Gleb Derujinsky’s sculpture of Leda being ravished by a cygnified Zeus, he gasped “Why, it’s coitus” and promptly canceled his advertising in The Dial. And when John R. Sumner, head of The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, took umbrage at an article in the magazine attacking censorship, he was invited to submit a rebuttal. This he did in July 1921, and his piece made a very poor case, attacking “people in this country who like to bring forward something ‘foreign’ and hold it forth as an example of the way things should be done over here.’” The editors of that issue also made their own arch point by bookending Sumner’s piece with a George Moore sonnet in French and a Gaston Lachaise drawing of a naked and very buxom woman. At times, though, Thayer chose discretion over bravery; he vetoed reproduction of a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe as “commercially suicidal.” In some editorial decisions there was a cocking of the snoot at the authorities and in others the desire to ensure the future of the magazine. Thayer walked the line perfectly.

Thayer and Watson, both “Harvard men” from wealthy families, often clashed in their tastes. Thayer grew to abhor the productions of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, while Watson was a great champion of both. Thayer was strongly inclined toward the visual art and literature of Germany and Austria, while Watson was a thoroughgoing Francophile. Thayer’s dislike of his former friend T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” almost cost The Dial the first American publication of what would become the poem of the century, and it took all the diplomacy of Watson and the promise of the $2,000 Dial Award and other considerations to entice Eliot back on board. Other disagreements were often settled by veto, each man being allowed a single unchallenged rejection per issue. On a couple of occasions, Thayer threatened to step down from the magazine, but the two hung in together for six years before the 1926 mental breakdown that caused Thayer to leave the magazine and withdraw from public life. The Dial continued to publish until 1929, thus roughly bookending that miraculous decade of Modernism.

Thayer retired from the magazine and largely from public life in 1926. He had always been eccentric and suspicious of the people around him, but his mental condition deteriorated sharply in the mid-1920s, filling him with paranoia and a dread of being alone. He was eventually institutionalized and declared “an insane person”. For the rest of his long life (he died in 1982 at 92) he traveled among his homes with a nurse and servants.

Thayer had aspirations to be a poet, and constantly grumbled that his work on The Dial was preventing him from writing. But a century after he and Watson entered publishing, it is the magazine for which he is, and will always be, remembered.

James Dempsey, the author of The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer, is an essayist, novelist and a writing teacher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Take two and call me in the morning

“The Spheres,’’ by Kathleen Kucka, in her show “Slow Burn,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., through April 25 but not open to the general public. New Canaan is in affluent Fairfield Country, which has had a high incidence of COVID-19, a bit of it attributed to a big party in Westport, which turned out to be a big spreader.

But not exactly a pleasure dome

The Connecticut Capitol

“The gold dome of Hartford gone

At sunset starts the thought of one who did

Of the mind a gold dome make

Accessible to strangers. Kubla Khan….’’

— From “Passing East of Hartford,’’ by Ernest Kroll (1914-1994

xxx

Kubla Khan

Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment.

By Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round;

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Xanadu (here called Ciandu, as Marco Polo called it) on a French map of Asia made by Sanson d'Abbeville, geographer of King Louis XIV, dated 1650. It was northeast of Cambalu, or modern-day Beijing.

A Nutting case

New Hampshire’s Presidential Range

On the short New Hampshire coast at North Hampton

“From sea beach to mountain top all beautiful! Who does not know her fame for wealth, rest and joy! Her head is in the snows and her feet on the ocean marge. She reaches her hands to the weary children of men. With her is the delight that does not stale.’’

Wallace Nutting, in New Hampshire Beautiful (1923)

Playing on at Tanglewood?

“Yo-Yo Ma, Emmanual Ax, Leonidas Kavakas at Tanglewood” (ink and pastel on toned paper), by Carolyn Newberger, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, visible to the general public only on the Internet.

At this writing, the 2020 season at the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s famed summer home, in Lenox, Mass., in the Berkshires, was still on.

Seiji Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood

Llewellyn King: On the 50th Earth Day, grounds for hope amidst the mess

President Nixon and his wife, Patricia, plant a tree on the White House grounds to mark the first Earth Day, in 1970. The Republican Party had many environmentalists back then. In the same year, Nixon signed into law the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

On the face of it, there isn’t much to celebrate on April 22, the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. The oceans are choked with invisible carbon and plastic which is very visible when it washes up on beaches and fatal when ingested by animals, from whales to seagulls.

On land, as a run-up to Earth Day, Mississippi recorded its widest tornado – two miles across -- since measurements were first taken, and the European Copernicus Institute said an enormous hole in the ozone over the Arctic has opened after a decade of stability.

But perversely, there’s some exceptionally good news. Because of the cessation of so much activity, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the air has cleared dramatically; cities around the world, including Mumbai and Los Angeles, are smog-free. Also, the murk in the waters of Venice’s canals and the waves from motorboats are gone, revealing fish and plants in the clear Adriatic water.

Jan Vrins, global energy leader at Guidehouse, the world-circling consultancy, was so excited by the clearing that he posted and tweeted a picture taken from a town in the Punjab where Himalayan peaks are visible for the first time in 30 years.

The message here is very hopeful: With some moderation in human activity, we can save the environment and ourselves.

The sense of gloom and hopelessness that has attended a litany of environmental woes needn’t be inevitable. Mitigating conduct in industry and, particularly in the energy sector, can have a huge impact quickly; transportation will take longer. Vrins says the electric utility industry -- a source of so much carbon -- is now almost entirely engaged in the fight against global warming. Just five years ago, he says, they weren’t all fully committed to it.

Another Guidehouse consultant, Matthew Banks, is working with large industrial and consumer companies on reducing the impact of packaging as well as the energy content of consumer goods. Among his clients are Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Johnson & Johnson. The latter, he says, has been working to reduce product footprint since 1995.

“This is an important moment in time,” Banks says. “Folks have talked about this as being The Great Pause and I think on this Earth Day, we need to think about how that bounce back or rebound from the Great Pause can be done in a way that responds to the climate crisis.”

I was on hand covering the first Earth Day, created by Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson, a Democrat, and its national organizer, Denis Hayes. It came as a follow-on to the environmental conscientiousness which arose from the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring, in 1962. That dealt with the devastating impact of the insecticide DDT.

Richard Nixon gave the environmental movement the hugely important National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. With that legislation, and the support of people like Nelson, the environmental movement was off and running – and sadly, sometimes running off the rails.

One of the environmentalists’ targets was nuclear power. If nuclear was bad, then something else had to be good. At that time, wind turbines -- like those we see everywhere nowadays -- hadn’t been perfected. Early solar power was to be produced with mirrors concentrating sunlight on towers. That concept has had to be largely abandoned as solar-electric cells have improved and the cost has skidded down.

But in the 1970s, there was reliable coal, lots of it. As the founder and editor in chief of The Energy Daily, I sat through many a meeting where environmentalists proposed that coal burned in fluidized-bed boilers should provide future electricity. Natural gas and oil were regarded as, according to the inchoate Department of Energy, depleted resources. Coal was the future, especially after the energy crisis broke with the Arab oil embargo in the fall of 1973.

Now there is a new sophistication. It was growing before the coronavirus pandemic laid the world low, but it has gained in strength. As Guidehouse’s Vrins says, “We still have climate change as a ‘gray rhino’, a big threat to our society and the world at large. I hope that utilities and all their stakeholders will increase their urgency of addressing that big threat which is still ahead of us.”

Happy birthday Earth Day — and many more to come.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

N.E. Council update: New intubation device; new mobile health program, and more

The seat of local government in Hanover, Mass., where an innovative mobile health program is underway

—Photo by ToddC4176

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

As our region and our nation continue to grapple with the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, The New England Council is using our blog as a platform to highlight some of the incredible work our members have undertaken to respond to the outbreak. Each day, we’ll post a round-up of updates on some of the initiatives underway among Council members throughout the region. We are also sharing these updates via our social media, and encourage our members to share with us any information on their efforts so that we can be sure to include them in these daily round-ups.

You can find all the Council’s information and resources related to the crisis in the special COVID-19 section of our website. This includes our COVID-19 Virtual Events Calendar, which provides information on upcoming COVID-19 Congressional town halls and webinars presented by NEC members, as well as our newly-released Federal Agency COVID-19 Guidance for Businesses page.

Here is the April 15 roundup:

Medical Response

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Researchers Construct New Intubation Device – Healthcare professionals at Brigham and Women’s Hospital have built a new intubation device that limits potential exposure when treating COVID-19 patients. The design was created to be reusable and to protect workers from even microscopic exposure to the virus transmitted through the air by covering a patient’s nose and mouth. WHDH has more.

South Shore Health Launches First Mobile Health Program in Massachusetts – South Shore Health has partnered with the town of Hanover to provide local residents with an innovative mobile health program that offers both testing and health services. Healthcare providers and emergency workers in Hanover will provide at-home testing for those who meet certain criteria or are in vulnerable populations, as well as daily follow-up calls from a volunteer nurse phone bank until infected patients recover. Read more from Boston 25 News.

Economic/Business Continuity Response

IBM Offering Free Computer Systems Training – IBM is offering a free training course on how to code in Common Business Oriented Language (COBOL). States from Kansas to Connecticut still use COBOL in their statewide unemployment systems—now facing increased demand—along with several federal agencies and almost half of United States banking systems. The course is free online and includes a forum where learners can get real-time help from those proficient in COBOL. TechSpot has more.

Boeing Producing Reusable Face Shields in Factories Boeing manufacturing sites across the country are being repurposed to produce reusable face shields to meet the growing demand for protective equipment. Masks will be 3-D printed and distributed to healthcare workers directly exposed to the virus. The aerospace manufacturer has already delivered 2,300 shields and plans to increase output weekly to alleviate strain on existing equipment supplies. Read more from KIRO 7 Seattle

UMass Medical Students Receive New Pandemic Training – As students at the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Medical School are continuing their education remotely because of the pandemic, the Worcester school is now offering a special two-week coronavirus pandemic course. The new class replaces typical hands-on experience with simulations for scenarios that have become common in medical students’ future workplaces, such as navigating telehealth or managing an emergency room with only medical students. Read more in The Worcester Telegram.

Citizens Bank Establishes Small Business Grant Fund – Citizens Bank, in partnership with the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), is awarding $400,000 in grants to small businesses in Massachusetts. Grant awards are meant to prevent layoffs, avoid insurance gaps, and promote stability in the wake of economic uncertainty. Priority will be given to minority- and women-owned businesses. Read more in MassLive.

Community Response

John Hancock Providing Free Meals to Boston Hospital Staff – To provide assistance to essential healthcare workers exposed to the novel coronavirus, John Hancock is partnering with nonprofit Off Their Plate to donate 8,500 meals to workers in Boston hospitals. The meals will be prepared by a variety of restaurants in the city to support restaurants and their staff as they face their own revenue losses. Read more from PR Newswire

...to the future?

“Door,” by Jamie Cascio, at Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass. Exhibitions not open to the general public now, for the usual reason.

Sarah Anderson: The Postal Service is essential and needs help in the pandemic

Via OtherWords.org

The U.S. Postal Service plays a vital role in our nation’s health and stability at this time of crisis. Unfortunately, it’s financially strapped — and got just crumbs in the $2.2 trillion stimulus package recently passed by Congress.

President Trump’s response? A stream of false accusations.

“They lose money every time they deliver a package for Amazon or these other internet companies,” Trump said. “If they’d raise the prices by, actually a lot, then you’d find out that the post office could make money or break even. But they don’t do that.”

For years now, Trump has repeated the lie that USPS loses money on these deliveries, even though a task force Trump himself commissioned in 2018 contradicted it. In its most recent quarterly statement, USPS reported a 2.3 percent increase in revenue from parcel delivery and increased revenue per package.

The real cause of the Postal Service’s immediate financial crisis is the coronavirus pandemic. Mail volumes have plummeted under the economic shutdown, and package delivery profits cannot make up for the loss. USPS management has warned that mail volume and revenue could drop by 50 percent or more this year.

Support for the Postal Service crosses partisan lines. You’d think a bit more compassion might be in order at a time when postal workers are on the frontlines, straining to meet the skyrocketing need for home deliveries of essential goods.

But playing hardball on crisis aid gives Trump and his administration the leverage they’ve been seeking for years to gut the public Postal Service.

The crumbs in the stimulus law amount to $10 billion in additional debt, subject to conditions imposed by Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. By contrast, House Democrats had proposed a $25 billion cash infusion to prevent the Postal Service from possible collapse.

In the final law, USPS competitors Fedex and UPS got a much better deal than the Postal Service. Under the airline bailout, both of these companies are eligible for a portion of the $4 billion in cash assistance for payroll support and another $4 billion in loans and loan guarantees for air cargo carriers.

While Mnuchin’s loan conditions are not public, they likely echo recommendations from the 2018 task force he chaired, which included partial privatization, draconian cuts to wages and services, and elimination of employee collective bargaining rights.

Unlike many other industries, the Postal Service cannot furlough workers and still achieve its essential mission. Like health care professionals and emergency responders, postal workers are essential to our public health because their deliveries make it possible for people to stay at home and not spread the virus.

Millions of people are relying on them to deliver medications and other essential goods, as well as the stimulus checks they’re waiting for to help cover their bills. Come November, postal workers will also be needed to protect the integrity of our election system by facilitating vote by mail.

Without the Postal Service’s network of 157 million daily delivery points and 35,000 post offices, there would be no way to carry out these essential activities. Jacking up package delivery rates now, as Trump is demanding, would harm postal customers, particularly in rural areas — just when they need these services most.

Postal workers are rising to the challenge of a crisis unlike any we’ve ever experienced. The last thing they need is for the president to dismiss the gravity of the Postal Service’s financial situation.

The American Postal Workers Union has organized a petition demanding urgent financial support for USPS. Trump and Congress must heed their call and save our public Postal Service — and the many businesses and families that depend on it.

Sarah Anderson directs the Global Economy Project at the Institute for Policy Studies. This op-ed was adapted from Inequality.org and distributed by OtherWords.org.

When Edna passes by

Track of Hurricane Edna, in September 1954

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

Americans are famously impatient – not good in something open-ended like a pandemic that might be with us for at least for a year or two, probably in waves, before a vaccine hits the market. And we’ll tend to see the whole crisis as having ended when it passes by our locale for a while. It reminds me of a 1954 essay by E.B. White called “In the Eye of Edna,” in which he noted that once a hurricane of that name went by Boston, the big news media lost interest in it even as it was slamming the Maine Coast. We’re already seeing this in the stock market on some days in which there’s news that reported COVID-19 cases might be leveling off. Sorry, we don’t know how this thing will unfold. It’s very early and information is very incomplete.

On opening up the economy, I’m a little Trumpian. The closures now in effect could soon do more direct health damage, as well as economic damage, than the disease. We need to start opening up business in early May, while being prepared for perhaps several years of cycles of lifting social controls and then reimposing them in hot spots as the pandemic recurs, hopefully with less severity than this first round because of widening herd immunity. It’s obvious now that at least for the next few years, most of us will be living differently than we had before the virus. Until memories fade?

God help many small businesses and social organizations. Some people may permanently avoid them for fear that customers and members might be a source of disease.

Many people will permanently lose their jobs because of the closures. Some companies are already finding that they don’t need as many people as they thought. All the more reason to institute Medicare for all who want it, to offset the loss of employer-provided private health insurance, and start a national infrastructure-repair-and rebuilding program to employ millions of people and make the country more competitive. America may need civil engineers more than it needs software engineers. .

'Along the strand'

Popham Beach State Park, in Maine

“It’d been a long winter, rags of snow hanging on; then, at the end

of April, an icy nor’easter, powerful as a hurricane. But now

I’ve landed on the coast of Maine, visiting a friend who lives

two blocks from the ocean, and I can’t believe my luck,

out this mild morning, race-walking along the strand.’’

— From “Strewn,’’ by Barbara Crooker

Flee to the countryside?

Remnant of an old mill in Clayville, R.I.

Vineyard in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where my maternal grandfather grew up on a farm.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some of the last few days have seemed abnormally cold, and they certainly have been mostly gloomy. But in fact temperatures have generally been at, or even a little above normal, the past few weeks. We’d been spoiled by the extraordinarily warm winter, and thus find the normally hesitant New England spring more depressing than usual. Well, yes, there’s the other thing, too…

The current emergency may be making far more people aware of Nature in the spring because far more are walking around outside to battle claustrophobia and to get exercise, partly because most gyms have been closed. But it’s not a very social experience, as, for example, people tend to keep on the other side of the street from fellow walkers. Still, at least they’re looking at the flowers and trees more than they might have in a “normal spring.’’

I’ve been thinking that this would be a good time to head up to New Hampshire and Vermont, get a room at a Motel 6, if I can find one open, and check out the last of this year’s maple-syrup-making operations for a few days. Yeah, COVID-19 will be circulating up there too but the scenery is therapeutic.

An old friend of ours who lives in Florida part of the year has several dozen acres of field and woods in the Clayville section of Scituate, R.I. She only half-jokingly suggested that she’d move full time back to Clayville and “live off the land,’’ as people there (mostly) did 250 years ago. It wasn’t that long ago, historically speaking, that many of our ancestors lived on farms. My maternal grandfather’s family had a couple of farms in Upstate New York, and even some of my New England ancestors in the great-grandparent generation had working farms in Massachusetts. Those who didn’t might have had at least a couple of cows and some chickens.

A tad premature?

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which used to be called “The Athens of America.’’

-- Bernard DeVoto (1897-1955), American essayist, critic and historian

....that our meetings are cancelled

“The Announcement ‘‘ (oil on canvas), by Iwalani Kaluhiokalani, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, available to see only online now

Elizabeth Prince: Response to COVID-19 helps unveil the extent of air pollution

From eco RI News (ecori.org)

NEWPORT, R.I.

While millions have been horribly affected by COVID-19, there is a silver lining to this pandemic. With the resulting global shutdown, the environment’s health is actually improving, and with that comes undeniable proof that humans are largely to blame for longstanding environmental degradation.

In India's Punjab region, the Himalayan Mountains can be seen with the naked eye for the first time in 30 years. For now, Los Angeles is free of its perpetual smog blanket, and the Northeast Corridor’s air is also clearer and cleaner.

It’s estimated that 8.8 million people die prematurely every year globally because of air pollution. That happens mainly in areas near major highways and/or coal-burning facilities. Researchers are studying the probability that the higher number of COVID-19 deaths reported in industrial northern Italy stem from the added hazards of air pollution in that region. This is compared to fewer virus-attributed deaths thanks to the less-polluted skies in Italy’s more agricultural southern regions.

Humans aren’t alone in their suffering. All of nature’s creatures are plagued by the ecological devastation caused by complicit governments, together with corporate entities' greedy desire to maximize profits at an ecosystem’s expense.

We must encourage and actively support the critical work of environmental and educational organizations with increasing pace. Individuals and governments must realize our newly emerging cleaner environment is a direct product of mankind’s forced curtailment of polluting activities, due to COVID-19's heavy restrictions on transportation and industry. Proof that human behavior is guilty of degrading the world’s air, water, and soil is visible and undeniable now more than ever. That it took a pandemic to begin lifting the veil from skeptics’ eyes is discouraging and saddening, but truth is often more visible during real, unexpected challenge.

Elizabeth “Lisette” Prince is a Newport, R.I., resident

Comment0 Likes Share

'Yearning for a new location'

Along Plymouth’s shoreline

“The night mist leaves us yearning for a new location

to things impossibly stationary,

the way they’d once float houses

made from dismantled ships, brass and timber,

from Plymouth, Massachusetts, across the sound

to White Horse Beach. You were only a boy.’’

— From “Floating Houses,’’ by David Wojahn

Charles F. Desmond: COVID-19 crisis displays 'The Amazing Generation'

— Photo by Artur Bergman

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

As a nation, we are taught to understand that it is sometimes necessary to send soldiers into harm’s way to fight for values and principles that we believe are worth sacrificing for. Today, and throughout our history as a nation, young men and women have been called upon to fight in foreign lands for the advancement of democracy and to secure and preserve the religious rights and political freedoms of marginalized groups and disenfranchised individuals.

I am a decorated veteran of the unpopular war in Vietnam. I went to war believing in the aforementioned values and principles. Over the many years that have passed since then, I have on occasion questioned whether my military service mattered, whether the suffering, destruction and loss I saw on the battlefield served a larger purpose, or whether anything of value in America was derived from the loss of treasure and human sacrifices made in that war’s name.

Over the past month, I have watched the deadly march of the COVID-19 virus from across the world and onto our nation’s shores. The human toll wrought by the virus has now exceeded 22,000 in the U.S. Coupled with this dreadful loss of human life, the economic and social upheaval the virus has rendered is beyond anything we have witnessed in recent history.

In the face of this human suffering and social upheaval, we are witnessing across the country, I have been heartened and inspired by the selfless and heroic actions of our younger generation of Americans. Any doubts I had about what American stands for or how we as a nation care for and support each other have been answered. One need only read the daily newspaper or turn to any television station and you will see thousands of young Americans who have put themselves into harm’s way in their battle to do whatever is necessary to defeat this virus.

I see a generation who were not drafted and who did not enlist to serve in this war but who have stepped forward in cities and towns, hospitals and schools and everywhere else where they are needed in the national campaign to eradicate this virus from our country. I have watched in wonder and pride as doctors, nurses, researchers, emergency medical personnel, police, fire and military service members, truck drivers and grocery store cashiers who all have put their personal and family safety aside and, under unimaginable conditions, fearlessly faced this horrific disease in an effort to serve, support and save their fellow Americans who, without them, would surely fall victim to a virus that does not discriminate by race, color, age or economic status.

The generation that fought in World War II much later came to be called The Greatest Generation. Some scholars and pundits have written that that generation may have been America’s greatest. I do not agree. I believe we are now witnessing the emergence of a new generation of Americans that cannot be called anything other than “The Amazing Generation. ” If their actions and behaviors now are any indicator, America is now and will continue to be in good hands.

Charles F. Desmond is CEO of Inversant, the largest parent-centered children’s saving account initiative in the Massachusetts. He is past chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) and since 2011, has served as a NEBHE senior fellow.