Gridlocked in the Depression

Downtown Boston in 1932, in the Great Depression. You might not guess unemployment was over 20 percent! But then, Will Rogers said at the the time:

“We are the first nation in the history of the world to go to the poor house in an automobile. ‘‘

2d Amendment art

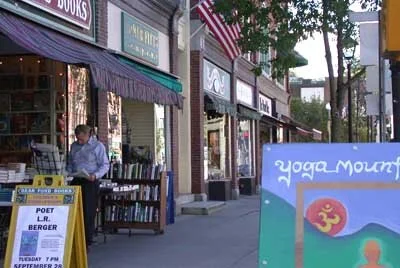

“Revolver 14’’, by Corey Pickett, in the group show “Either I Woke Up, or Come Back to This Earth,’’ at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier.

The gallery says: “These artists use playfulness and humor to challenge histories of political violence and the anesthetic of nostalgia.’’

The Vermont State House, in Montpelier, the smallest state capital, which has only about 8,000 residents. It’s surprisingly arty and has a strong culinary scene, too. It hosts the New England Culinary Institute, which runs some local restaurants.

In downtown Montpelier

Montpelier in 1884

Russ Olwell: Early college programs are way for New England colleges to avoid demographic disaster in years ahead

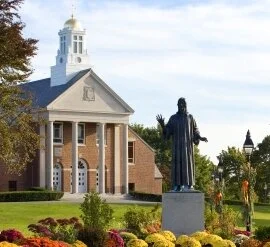

At Merrimack College, a private Augustinian college in North Andover, Mass. It was founded in 1947 by the Order of St. Augustine with an initial goal to educate World War II veterans. The college has grown to encompass a 220-acre campus and almost 40 buildings. North Andover is both a Boston suburb, high end in some places, and also a former mill town. It also hosts the Brooks School, a fancy boarding school.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

This photograph on top from Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s State of the Commonwealth address last month shows more than just happy college students in their sweatshirts. These students, from Northern Essex Community College and Merrimack College, are part of cohorts of students who have graduated from “early college” programs (with up to a year’s college credit) and successfully matriculated into a two- or four-year college. Recipients of the Lawrence Promise Scholarship at the Haverhill-based (but multi-site) Northern Essex Community College and the Pioneer Scholarship at Merrimack College, these students are on track to graduate on time, and can serve as mentors and role models to young people in their families and in their neighborhoods—proof that college is a real possibility.

Why are these students so important?

The students in the picture, and graduates of similar programs, offer a chance to avoid a demographic crash that faces higher education nationwide (but hits hardest in New England). This is most strikingly laid out in Nathan Grawe’s book Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education, which uses survey data and mathematical modeling to predict the future of higher education. For two-year institutions, regional four-year institutions and all but the top 50 colleges nationwide, the news in Grawe’s book is grim: The decline in childbirths in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008-9 will reverberate into the 2020s and 2030s. This will lead to fewer high school graduates, and fewer students with the family background and finances to propel them into traditional college enrollment.

Grawe considers a full range of possibilities to counteract this curve, such as changes in state higher- education policy, that could increase the proportion of students who might attend colleges, and reduce the racial gaps in groups attending college. In Grawe’s analysis, however, none of these policy tools will close the gap enough to save many higher-education institutions from closing, or from a stark decline in students and revenue.

What can change the curve?

The Commonwealth can try to bend this curve by increasing the number of students who aspire to go to college, and who have the skills to enroll and graduate. One such intervention, which has the potential to scale to the state level, is early college programming, in which high school students are able to take college coursework during the K-12 experience, in order to learn to successfully navigate the college world. Through success in college classes, these students stop thinking of college as a possibility, and instead as something they know they can do.

Early college programs have been a success story in American education, raising enrollments and enhancing student outcomes. Early college programs can help low-income and underrepresented students gain access to higher education and be more successful students once they arrive to college full time, according to research by David R. Troutman, Aimee Hendrix-Soto, Marlena Creusere and Elizabeth Mayer in the University of Texas System.

Early college programs (high school students attending college courses on campus) have shown great impact on academic achievement of students, net return on investment, and graduation rates of participating students.

In successful programs and statewide efforts, students thrive in these programs, are more likely to attend college and are remarkably more successful once they get to campus full time. They are more likely to graduate on time than their peers who attend traditional high schools, and earn a higher GPA.

Recent studies released by American Institutes of Research found the economic return of investment on early college programs to be $15 in benefit for every $1 investment; the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse recently certified the results of a random-assignment early college study that showed a positive impact in such key metrics as school attendance, number of school suspensions, high school graduation, college enrollment and earning a college credential.

New England has been a growing force in the early college field. Massachusetts now is home to at least 30 designated early college partnerships; Maine has created early college programs for its state four-year colleges, community college and maritime academy; and New Hampshire has launched a STEM-focused early college effort centered on career-technical education and the community college system. While these are far smaller than the efforts in Texas and North Carolina, they are making a positive impact and appealing to a broad range of families.

Scaling and expanding access

Early college programs have not been easy to expand or spread. First, like most successful policy interventions, they are hard to scale without losing the power of the model. The best early college programs are often about 400 students in size, run by dedicated instructors and leadership. Maintaining a size where each student can connect with at least one adult in the building is one of the keys to this work.

This model is hard to scale statewide, which is what would need to happen to have any meaningful impact on the downward curve of college applicants. Early college programs can also suffer from elitism. They can attract smart, ambitious, well-off students and families, leaving behind the populations that can be helped the most by the model. As college costs drive more behavior across the economic spectrum, middle-class and upper middle-class parents will see early college programs as a lifeline, and could seek out opportunities that had previously been designed for lower-income families. In my earlier work in Michigan, I saw programs start to fill up with the children of professors at the college housing the early college, as it was seen to be such a bargain.

However, as early college is embraced by new states and regions, policymakers are paying more attention to making sure that programs can grow, and can retain the characteristics that make the model so effective. As new programs are developed in Massachusetts, there is renewed emphasis on reaching the at-risk students who could be most helped by this intervention. With a push to help all students in a high school leave with some college credit, the impact of early college programs on student enrollment could counteract economic and social barriers to enrollment, moving whole cohorts of students into higher education.

In order for any of the above to have an impact on college enrollment a decade from now, state policy and spending will need to shift, investing in areas such as early college that can help students be successful in college from day one. Most importantly, early college programs and their impact would need broader recognition and support, and would need to be embraced by a wider range of K-12 and higher education leaders than have supported it to date. It might take today’s downward facing enrollment curve to get the attention of policymakers, who up until now have regarded early college with a mix of curiosity and suspicion. To save higher education in Massachusetts, we need more students up in the balcony, graduating from high school with college credit, ready to help their younger peers make the same good decisions.

Russ Olwell is a professor and associate dean in the School of Education and Social Policy at Merrimack College.

— Photo by NAThroughTheLens

An aerial view of the North Andover Old Center showing the North Parish of North Andover Unitarian Universalist Church.

Our coyote co-existence

Coyote calling for company

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘In its Feb. 14 article, “Valentine’s Day Is Also for Coyotes,’’ The Boston Guardian warn us that February marks the start of coyote mating season. Yes, there are plenty of opportunistic coyotes in Boston, including downtown, and in Providence and Worcester. The beasts become more skittish and territorial in mating time, and more likely to attack other animals, including people, at this time of the year. As mankind takes over more and more of the world, many creatures will have to learn -- like, for example, coyotes and raccoons – how to live close to humans, or go extinct.

They’ve got us under their skin

“Roosterfish” (cleared and stained specimen), in the show “Under the Skin,’’ at the Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Conn., through July 19

— image courtesy of Dr. Matthew Girard.

The museum (in one of America’s richest towns) explains that “Under the Skin’’ features technological innovation and the beauty of nature. It includes real biological specimens as well as imagery created by technology, including CT scanning, infrared cameras, scanning electron microscopes and other devices undreamt of a decade ago. In ‘‘Under the Skin,’’ a roosterfish skeleton or the inner ear of a frog becomes a work of art. “Both in science and art can one find new discoveries by peering beyond the surface and searching for something deeper.’’

The Round Hill Congregational Church in Greenwich, part of the Round Hill Historic District, one of the richest parts of a very rich town.

— Photo by Magicpiano

Llewellyn King: Sanders's economic fantasyland

From The Violet Fairy Book (1906)

It’s hard for me to believe that Donald Trump is president. Really hard. Equally hard for me to believe that Bernie Sanders is the Democratic front-runner, especially after the Las Vegas debate.

I can take Sanders’s passion, although it’s so consuming it gets to be frightening. I can take his calling himself a democratic socialist, although I don’t know to what extent his form of socialism pits him against capitalism. Enough, I fear.

Some of what Sanders had to say in Las Vegas was downright risible, or has been tried and failed, or, worse, would set in place a series of negative dynamics, damaging the country in many ways without bringing about any of the gains he wishes to achieve. Listening to him, I think, “This donkey wants his feedbag.”

In his way, Sanders is as committed to conspiracy theories as is Trump. Sanders sees vast, secretive forces in fossil-fuel companies, lobbyists, bankers and billionaires as being united in a scheme to keep the rest of us poor and ill-served by government.

Here are three of his big fallacies:

1. Companies would be better if they were partly owned by the workers. This is real socialism and it hasn’t worked when it’s been tried.

Sanders would be well-advised to read up on the history of the cooperative movement in Britain. The very first casualty would be innovation because worker governance isn’t risk-taking.

I say this having been very familiar with the British coop movement and having headed a trade union local, the Newspaper Guild, in Washington. Collective decision making is not creative, risk-taking or forward-looking.

2. The technology of fracking to extract oil and natural gas from tight rock formations should be stopped in order to combat global warming. That would deal the economy a body blow while doing nothing for global warming.

Carbon emissions from fossil fuels are coming down, and on the horizon is the technology of carbon capture, utilization and storage and other technological fixes for carbon emissions.

Technology has enabled fracking and technology, not cessation, will clean up emissions.

3. The current health-care mess should be replaced root-and-branch by a national health system. That we need a stabilizing public option in health care is more apparent daily. But health reform needs to be introduced like good medicine, prudently with the dosage corrected in relation to the progress of the patient.

Sanders’s approach to most issues can be summed up by what author H.G. Wells, a socialist, said of playwright G.B. Shaw’s ideas. He said the trouble with Shaw, also a socialist, was that Shaw wanted to cut down the trees to erect metal sunshades. Quite so.

In Las Vegas, Sanders was out to cut down every tree he could see. These included what is part of the American Dream: Anyone with pluck and hard work can improve their situation, and maybe grow rich.

Sanders’s assault on Mike Bloomberg was that Bloomberg didn’t accept some mythical belief that money is inherently bad and that those who’ve made a lot of it are evil and constantly conspiring to keep the rest of us in penury — at least those who earn up to the Senate salary of $174,000 a year.

The long-term evil of money isn’t in the generation that makes it, but in the families that will inherit it down through the generations, creating an oligarchy the likes of which we haven’t seen since the fall of the serf-exploiting Russian nobility.

Someone should take Sanders on one side and tell him about failed experiments in worker ownership, the value of evolution over revolution, and that every American would like to be rich.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

When Gov. Sargent said no to more ‘expressways’

Southwest Corridor Park in Boston as seen looking south from Ruggles Street. This is along the route of the cancelled Southwest Expressway.

— Photo by Grk1011

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A lot of people owe thanks to the late Massachusetts Gov. Frank Sargent, who on Feb. 11, 1970 declared a halt to the seemingly endless and destructive highway construction that was tearing up neighborhoods and making traffic worse (by drawing in more cars) in Boston. The same thing was happening in many other cities.

On that date, he was one of the first major political leaders in the country to call for a thorough reappraisal of our addiction to car culture as he cancelled the Southwest Expressway and Inner Belt highways. His action became a model for the country. Someone called him “anti-highway’’ but maybe a more accurate term would be “pro-city.’’

As he said at the time:

“Four years ago, I was the commissioner of the Department of Public Works – our road building agency. Then, nearly everyone was sure highways were the only answer to transportation problems for years to come. We were wrong. . . . Are we really meeting our transportation needs by spending most of our money building roads? The answer is no.”

Thus began attempts to rebalance transportation priorities, particularly by allocating a higher percentage of taxpayer funds to mass transit. As awful as is traffic in Greater Boston now (partly a product of its great prosperity for much of the past quarter century), think of how much worse it would be without the changes set in motion by Frank Sargent, an MIT-trained engineer. By stopping the destructive projects above and turning more attention to public transit, he helped protect and then raise the city’s quality of life as expressed in its vibrant neighborhoods and lovely parks and by eventually making it easier for many more people to move through Boston’s dense urban core, with its famously narrow, curving streets, without a car. This has been a boon for individuals and businesses.

This in turn helped make “The Hub” the prosperous world city it is today. Frank Sargent understood that the urgent need was to move more people, not more cars, and that only a much improved public transit system could do that. He also knew that relentlessly paving over green space for roads and parking lots was, to put it mildly, bad for the environment, as was the intensifying air pollution from vehicular traffic at the time.

Still, as former Massachusetts Transportation Secretary James Aloisi recently told Commonwealth Magazine: “We remain adrift on a sea of ideological resistance to raising the revenue we need to do the job, still fully in the grip of a stubborn auto-centric mentality that would prefer to see us all stuck in the worst traffic congestion in the nation rather than invest in a modern electrified regional rail system… that would entice many commuters to take commuter rail,’’ including from Providence, of course.

I covered Governor Sargent back then as a reporter for the Boston Herald Traveler, and fondly remember his high intelligence, his directness and his political courage, along with his humor, charm and ability to swear like a stevedore.

To read Mr. Aloisi’s piece, please hit this link.

xxx

Trump wants to slash funding for Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor service, on which traffic has been booming, to $325 million from $700 million. (To stick it to Blue States?) He’d also cut funding for the quasi-public railroad’s long-distance routes to $611 million from $1.3 billion. Those long-distance trains tend to be underpatronized. So he may have a point there. But it’s unlikely that these cuts will take place: To address crippling car congestion, an expansion, not a contraction, of Northeast Corridor train service, is needed. And reminder: Northeast Corridor trains are very heavily used for business travel. As for those long-distance trains: They serve many Red State communities whence cometh some powerful members of Congress….

And a bit higher each year

“Modern Tide” (acrylic & Japanese paper on canvas), by Laura Fayer, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through March 15.

Pond skating

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I’m not crazy about winter these days. For one thing, as you grow older your skin gets thinner and so you feel the cold more, and the spectacle of a snowstorm, however lovely to look at, quickly morphs into a depressing chore. But I have fond memories of skating on a little pond next to a marsh near our house, on Massachusetts Bay. Winters were more reliably cold then, and the pond became the neighborhood’s social center, for free-form skating and pick-up hockey, for several weeks in mid-winter. That’s even though some salt water moved into it in Nor’easters.

Fairly often someone would light a fire on the shore, encouraging people to hang around longer than they normally would. Good for roasting marshmallows. One very cold day I fell on the ice – I can’t remember if I was playing pick-up hockey or just loose skating – smashing my right elbow. This necessitated a rather long hospital stay for an operation, which introduced me to the charms and uncharms of the American health-care system. I had to wear a cast for several months. I very rarely skated after that. But I still vividly remember the wind in my face as I breezed around the pond, with nary a thought of the joys of spring.

You don’t see much pond skating anymore even in a long cold spell, which is sad. I think that a lot of parents seek out indoor rinks for their kids instead.

xxx

As weather conditions become more iffy for skiing, turn your eyes to East Rutherford, N.J., and its huge American Dream mall. There, in its 16-story-high building, is Big Snow American Dream – a well-refrigerated (28 degrees), four-acre ski area with man-made snow and a chair lift. It’s the same idea as the famous big indoor ski area in Dubai, where outdoor temperatures can hit 120 degrees.

I can well imagine how much fossil fuel must be burnt to keep Big Snow cold. In any case, the owners are doing their small part to increase the global warming that is gradually eroding the ski business in the nearby Poconos.

To read more, please hit this link:

Demigods

'Belong to themselves'

The Coolidge Homestead in Plymouth Notch, Vt., where the future Massachusetts governor and U.S. vice president and president was born in 1872

“Vermont is my birthright. People there are happy and content. They belong to themselves, live within their income, and fear no man.’’

— Calvin Coolidge, 1920

Work interval

“Between Tides” (oil on canvas), by David Witbeck, winner of the Maxwell Mays Prize in this year’s Winter Members’ Exhibition at the Providence Art Club through March 6.

Tim Faulkner: Is fossil-fuel-loving Trump regime trying to sabotage offshore wind?

Vineyard Wind is coming to terms with the fact that its wind project is behind schedule, as accusations of political meddling escalate.

On Feb. 7, the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) released an updated permitting guideline that moved the facility’s likely completion date beyond Jan. 15, 2022 — the day the $2.8 billion project is under contract to begin delivering 400 megawatts of electricity capacity to Massachusetts.

Vineyard Wind is now renegotiating its power-purchase agreement with the three utilities that are buying the electricity. The company is also in discussions with the Treasury Department about preserving an expiring tax credit.

The delay is being caused by a holdup with BOEM’s environmental impact statement (EIS). A draft of the report was initially expected last year, but after the National Marine Fisheries Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declined to endorse the report, it was pushed off until late 2019 or early 2020. Back then several members of Congress from Massachusetts claimed the delay was politically motivated.

BOEM now is predicting that the draft EIS won’t be ready until June 12, with a final decision by Dec. 18. The setback is significant because the draft EIS is being counted on to shape the mapping of other offshore wind facilities slated for the seven federal wind-energy lease areas off the coasts of Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

The Coast Guard recently released its Massachusetts and Rhode Island Port Access Route Study (MARIPARS). The report favors the grid design proposed by wind developers and discounted concerns about radar interference.

This navigational safety report also recommends that if the turbine layout in the entire Massachusetts and Rhode Island wind area is developed using “a standard and uniform grid pattern” then special vessel routing lanes wouldn’t be required.

The Coast Guard’s findings improve the prospect for development of all seven wind-energy lease areas. But the MARIPARS report and the draft EIS both require public comment periods and hearings.

Lars Pedersen, CEO of Vineyard Wind, said of the setback, “We look forward to the clarity that will come with a final EIS so that Vineyard Wind can deliver this project to Massachusetts and kick off the new U.S. offshore energy industry.”

This latest delay has again been criticized by members of the Massachusetts congressional delegation as a ploy by President Trump to demonstrate his aversion to wind energy and his favoritism for fossil-fuel companies.

On Feb. 5, two days before BOEM released the new timeline, Massachusetts’ two U.S. senators and seven members of Congress sent a letter to the U.S. Government Accountability Office expressing their outrage over Trump’s hypocrisy.

“Despite seeking expedited environmental reviews for numerous fossil fuel infrastructure projects, Trump administration officials in the Department of the Interior have ordered a sweeping environmental review of the burgeoning offshore wind industry, a move that threatens to stall or even derail this growing industry, and raises a host of questions for future developments,” according to the letter.

In a recent interview with the Vineyard Gazette, Rep. Bill Keating, D-Mass., whose district includes Martha’s Vineyard, said he believes BOEM planned to release the draft EIS much sooner, but stalled the report after political pressure from superiors in the Department of Interior or the Trump administration until after the presidential election in November.

“It’s clear to me that these are political decisions and not guided by wanting to mitigate environmental impacts,” Keating said.

When asked about the political interference, BOEM replied that the delays are caused by public comments that call for a more thorough review of a large and disruptive change to nearshore waters. Those comments cited the upsurge in new wind projects, an increase in the size of wind turbines used by Vineyard Wind, and potential conflicts with commercial fishing and navigation.

Meanwhile, investments in wind project port facilities continue along southern New England. Gov. Gina Raimondo has earmarked $20 million in her proposed budget for improvements to the Port of Davisville at the Quonset Business Park in North Kingstown, R.I. The work includes dredging, repair of an existing pier, and construction of a new pier.

Mayflower Wind, the next project after Vineyard Wind to win an energy contract from Massachusetts, recently announced its intention to make the New Bedford Marine Terminal its primary construction hub for its 804-megawatt project.

Tim Faulkner is an ecoRI News journalist.

'Physical truth into ephemera'

“Long Distance” (oil on canvas), by Iwalani Kaluiokalani, in her show “Magic,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, March 4-29.

The gallery says:

“Through movement and interaction, something beyond emerges in these paintings. Whether we call this connection, integration, or even divinity, we discover which both moves within and the boundaries of our perception. In these paintings, the artist has uncovered an embodied state of impossibility we could call magic. Magic is, in a deep sense the union of the impossible with actually seeing something that cannot be, yet is. These kaleidoscopic, repeated, rhythmic images exemplify the translation of physical truth into ephemera. The junction of what is and is not, through body and image, calls forth M A G I C.’’

David Warsh: Blame political choices, not economists, for today's mess

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A couple of recent books by well-regarded journalists – Binyamin Appelbaum and Nicholas Lemann, have blamed economists for the current state of the world. Reviewing these in Foreign Affairs last week, the peripatetic New York University economist Paul Romer embraced the authors’ judgments and added his own.

Having lost track of the distinction between positive and normative economics (is vs. ought), the profession has come to think of itself and be thought of by others as a tribe of philosopher-kings, Romer wrote. Citing the OxyContin epidemic and the 2008 financial crisis, he summed up in “The Dismal Kingdom”

Simply put, a system that delegates to economists the responsibility for answering normative questions may yield many reasonable decisions when the stakes are low, but it will fail and cause enormous damage when powerful industries are brought into the mix. And it takes only a few huge failures to offset whatever positive difference smaller, successful interventions have made.

A third book, Where Economics Went Wrong: Chicago’s Abandonment of Classical Liberalism, by economists David Colander and Craig Freedman (Princeton, 2019), mentioned by Romer, hasn’t received as much attention. It sets out the case in detail, with clarity and in depth. A fourth book, In Search of the Two-Handed Economist: Ideology, Methodology and Marketing in Economics, by Freedman (Palgrave 2016), offers the deepest dive of all, but hardly ever comes up outside of professional circles (where it is often discussed with hand-rubbing, lip-smacking enthusiasm, thanks to the extensive interviews it contains).

Accoding to Colander and Freedman, economics began to go off-course in the 1930s, when it embraced an ambitious new program that came to be known as “welfare economics,” replacing the “classical liberalism” of John Stuart Mill. The new framework developed slowly, led by John Hicks and Abba Lerner at the London School of Economics, Arthur Pigou at Cambridge University, and Paul Samuelson at Harvard University and The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but in the 1950s, seemed to virtually take over the profession, coming to be associated simply with the macroeconomics of John Maynard Keynes.

The new framework was conducted with mathematical and statistical models instead of arguments about moral philosophy and curiosity about, even respect for, existing institutions. Believing itself to be an understanding superior to what had gone before, This new approach – now simply “the new economics,” abandoned the traditional firewall between science and policy.

Irked and, for a time, flummoxed by welfare economics’ assertiveness, especially in its Keynesian form, young economists from all over congregated at the University of Chicago, starting in 1943. Led by Milton Friedman, George Stigler and Aaron Director, they began to look for flaws in Keynesian doctrines, which they viewed as “a Trojan horse being used to advance statist ideology and collectivist ideals,” Colander and Freeland say.

Secure in their belief that markets could, to a considerable extent, take care of themselves, thanks to the powerful solvent of competition, the Chicagoans responded to normative science with more stringent normative science. They devised an alternative “scientific” pathway that would lead to their intuited laissez-faire vision.

“Because of their impressive rhetorical and intuitive marketing skills, the Chicago economists eventually managed to engineer a successful partial counterrevolution against [the] general equilibrium welfare economic framework,” write Colander and Freedman. But embracing cost-benefit analysis required abandoning the tenets of debate focused on judgements and sensibilities – “argumentation for the sake of heaven,” as the authors prefer to put it

So what does a present-day hero of classical liberalism look like? Colander and Freedman cite six well-known exemplars: Edward Leamer, who wrote a classic 1983 critique of scientific pretension, “Taking the Con Out of Econometrics”; Ariel Rubinstein, a distinguished game theorist who describes models as no more compelling than economic fables; Dani Rodrik, a rigorous trade theorist who asked as long ago as 1997, Has Globalization Gone Too Far?; Nobel laureate Alvin Roth, who likens the role of many economist to that of an engineer; Amartya Sen, another laureate, recognized for his “scientific” work on collective decision-making but honored for his policy work on the development of capabilities; and Romer, another laureate perhaps better known for his biting criticism of “mathiness,” akin to “truthiness,” among leaders of the profession.

All are excellent economists. But almost certainly it was not the economics profession that led the world down a garden path to its present state of discombobulation. In his Foreign Affairs review, Romer asserts,

For the past 60 years, the United States has run what amounts to a natural experiment designed to answer a simple question: What happens when a government starts conducting its business in the foreign language of economists? After 1960, anyone who wanted to discuss almost any aspect of US public policy – from how to make cars safer to whether to abolish the draft, from how to support the housing market to whether to regulate the financial sector – had to speak economics. Economists bring scientific precision and rigor to government interventions, the thinking went, promised expertise and fact-based analysis.

Far more persuasive were the natural experiments conducted in the language of the Cold War. They include the rise of Japan in the global economy; the decision of China’s leaders to follow its neighbors’ example and join the global market system; the slow decline and rapid final collapse of the Soviet empire; the financial-asset boom that followed Western central bankers’ success in quelling inflation; the globalization that accompanied a burst of “deregulation”; the integration that accompanied the invention of computers, satellites, and the Internet; and the escape from extreme poverty of 1.1 billion people, a seventh of the world’s population.

Rivalries among nations were far more influential in precipitating these changes than were contests among Keynesians and Monetarists, even their magazines and television debates. Political choices produced the present world – grass roots, top-down, and everywhere in between. Economists scrambled to keep up.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

The same old, cold day

“The waiting room was bright

and too hot. It was sliding

beneath a big black wave,

another, and another.

“Then I was back in it.

The War was on. Outside,

in Worcester, Massachusetts,

were night and slush and cold

and it was still the fifth

of February, 1918.’’

— From “In the Waiting Room,’’ by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-79)

Three deckers on Houghton Street, Worcester.

American Steel & Wire Company, c. 1905, employer of about 5,000 during Worcester’s industrial heyday.

We all swim in politics

Rhode Island Convention Center

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

With possible scandals swirling in and around the Rhode Island Convention Center – and such problems seem to eventually arise in every such facility -- we shouldn’t forget that having this attractive complex has been important in the revival of downtown Providence since the capacious facility was opened in 1993 during the visionary administration of the late Gov. Bruce Sundlun. For one thing, the building of the Convention Center led to a big increase in downtown hotel rooms, with all sorts of economic spinoffs, such as new restaurants. The only major drawback to its construction was that city’s main commercial inter-city bus terminal was moved from the Convention Center site to a depressing, wind-swept site on the edge of Providence, outside of walking distance for most people.

And yes, politics always enters into the running of facilities like the Convention Center. For that matter, politics (including nepotism) enters into the operations of pretty much all large organizations, in the public and private sectors. Much, maybe most, of human life is “politics’’.

'Inconsistencies of memory'

Work by Allison Bianco, in her show “Forget About It,’’ at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, May 9-July 31. The gallery says: “Allison Bianco is a printmaker who uses a combination of intaglio and screen print to depict landscapes diminished by massive oceans and infinite skies. Her vibrant prints explore nostalgia and inconsistencies of memory. ‘‘

'Joy shivers in the corner'

Here where the wind is always north-north-east

And children learn to walk on frozen toes,

Wonder begets an envy of all those

Who boil elsewhere with such a lyric yeast

Of love that you will hear them at a feast

Where demons would appeal for some repose,

Still clamoring where the chalice overflows

And crying wildest who have drunk the least.

Passion is here a soilure of the wits,

We're told, and Love a cross for them to bear;

Joy shivers in the corner where she knits

And Conscience always has the rocking-chair,

Cheerful as when she tortured into fits

The first cat that was ever killed by Care.

“New England,’’ by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935), a Maine native and winner of three Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry.