At least at first

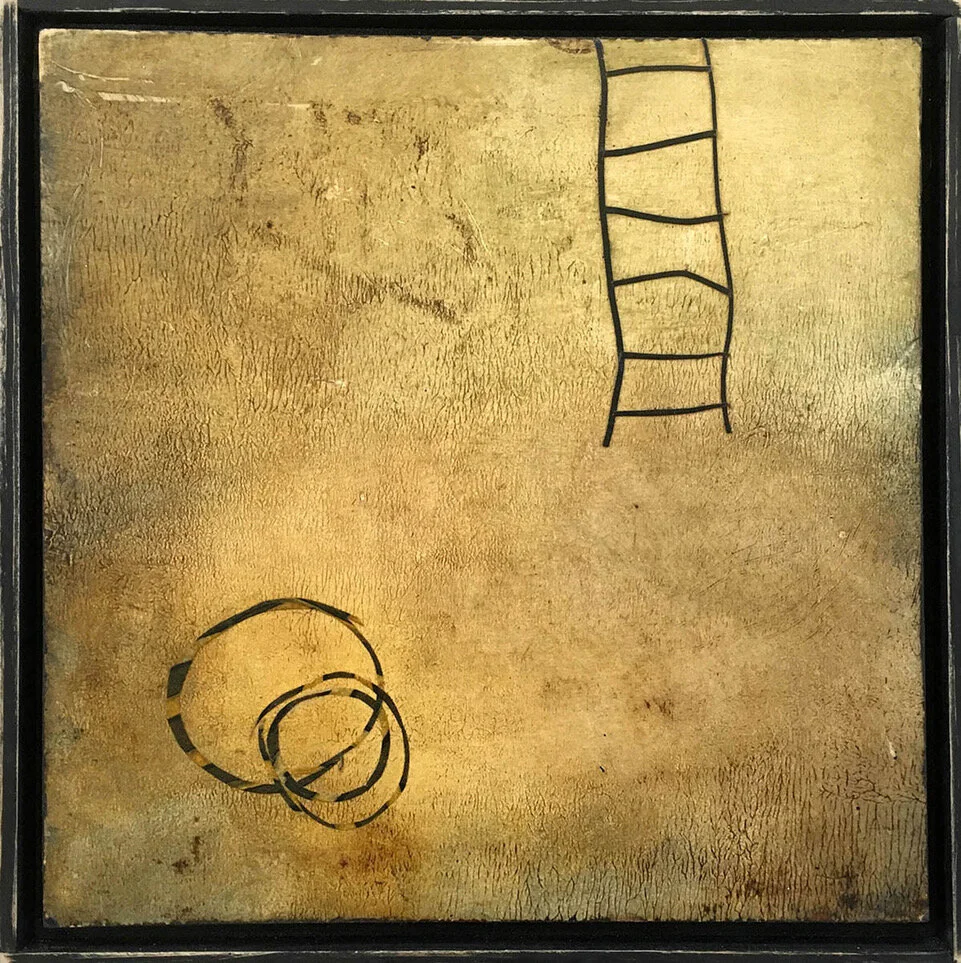

“Discreet” ( acrylic and mixed media on canvas), by Ellen Rolli, at Edgewater Gallery, Boston

David Warsh: In which the whys didn't matter

Jim Simons speaking at the Differential Geometry, Mathematical Physics, Mathematics and Society conference in 2007 in Bures-sur-Yvette, France. He’s a giant of the quants revolution.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The latest book from Gregory Zuckerman is an ideal companion on the reading table next to whatever it is you haven’t read by Michael Lewis, the author who has replaced Tom Wolfe – The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), “The Me Decade and the Third Great Awakening” (1976), Bonfire of the Vanities (1987), A Man in Full (1998) – as the premier storyteller of his age.

Lewis, from Liar’s Poker: Rising through the Wreckage on Wall Street (1989 about Salomon Brothers’ John Gutfreund and financial deregulation) and The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story (1999, about software entrepreneur Jim Clark and the browser wars that followed the invention of the World Wide Web); to Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game (2003, about new-fangled baseball analytics and Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Bean) to The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game (2006, about new-fangled football analytics and left tackle Michael Oher), has illuminated major changes in familiar institutions, in always entertaining but sometimes misleading ways.

After the 2007-08 financial crisis, Lewis published The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine (2010, about the use of credit default swaps to bet against the subprime mortgage market), followed by Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt (2014, about high-frequency trading).

Zuckerman, who has the advantage of being a special writer for The Wall Street Journal, is the journalist who gets those changes more nearly right, on the stories on which he and Lewis compete.

The Big Short is about Michael Burry, the physician-turned-hedge-fund-operator who recognized the possibilities inherent in the subprime bubble but who failed to get the timing right. Zuckerman’s The Greatest Trade Ever: The Behind-the-Scenes Story of How John Paulson Defied Wall Street and Made Financial History (2009) tells the story of the money manager who made $15 billion for his investors – and $4 billion for himself – by getting the bet down right.

Zuckerman’s new book is The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution (2019). In between he wrote The Frackers: The Outrageous Inside Story of the New Billionaire Wildcatters (2013). When Simons stepped down as head of Renaissance Technologies Corp., in 2009, he was worth more than $11 billion, accumulated in the course of nearly constant trading – a more daunting task, perhaps, than scoring a single brilliant success, as Paulson’s post-2008 experience suggests.

The new book’s title is not quite right. There were plenty of quants before Simons quit the math department at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, many of them making good money. (See The Quants: How a New Breed of Math Whizzes Conquered Wall Street and Nearly Destroyed It (2010), by Scott Patterson, More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite (2011) by Sebastian Mallaby). What set Simons apart was his drive to make the most money from his considerable skills as a professor of mathematics, in collaboration with others possessing an academic degree or skill at the same level.

Nor is the account quite as inside as Zuckerman’s other books. Simons declined to talk to him until fairly late in the game, and then only about certain topics, not including his still-secret recipes. Zuckerman had to work harder for this yarn than he did for the Paulson story, which featured a full-page portrait of its subject opposite the title page.

Simons, a well-adjusted prodigy, grew up in Newton, Mass., and attended Brookline’s Lawrence School. He discovered as an undergraduate at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology that he wasn’t quite at the top level of contemporaries in math, including fellow student Barry Mazur. He was, however, close enough to sail through his math PhD at the University of California at Berkeley in three years, before returning, in 1962, to Cambridge to teach.

Bored, Simons quit after a year to become a code-breaker at the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA), a Pentagon contractor in Princeton, N.J. In 1968, in collaboration with a Princeton University professor, he published a path-breaking paper in differential geometry that assured his reputation. But Simons had acquired a taste in California for commodity trading, and in his spare-time as a code breaker he and three colleagues published a stock-trading scheme. Zuckerman writes,

Here’s what was really unique. The paper didn’t try to identify or predict [various market] states using economic theory or other conventional methods, nor did the researchers seek to address why the market entered certain states. Simons and his colleagues used mathematics to determine the set of states best fitting the observed pricing data; their model then made its bet accordingly. The whys didn’t matter, Simons and his colleagues seem to suggest, just the strategies to take advantage of the inferred states.

One thing led to another. In 1968, at the age of 30, Simons left IDA for Stony Brook, on the north shore of Long Island, where the university administration had set out to establish a mathematics department strong enough to complement its world-class biology department. In 1976 he was recognized with the Oswald Veblen Prize, the profession’s highest honor in geometry. Two years after that, he quit the university and rented a storefront office in a strip mall across from the Stony Brook railroad station as proprietor of Monemetrics, a currency-trading firm, and Limroy, a tiny hedge-fund. A year later, two other distinguished mathematicians signed on as his partners.

It wasn’t a smooth beginning. Partners came and went. Mergers and acquisitions flourished, and with them the return to inside information – the opposite of the advantage Simons sought. But computer power doubled every two years, according to Moore’s Law, while prices fell by half. Simons changed his firm’s name to Renaissance Technologies.

By 1991 the talk of Wall Street was a former Columbia University computer science professor named David Shaw. He had learned the techniques of statistical arbitrage at Morgan Stanley before the old-line investment bank slashed the funding of one of its most profitable units after it had a bad year. Now, backed by veteran bond trader Donald Sussman, Shaw’s startup was the cutting edge of computer-based trading strategies.

Simons understood that, in order to compete with Shaw, he would need to develop new methods. Financial backers whom he sought, including legendary Commodities Corp., turned him down Among those he hired was mathematician Henry Laufer, a former Stony Brook colleague with a knack for programming. And among those Laufer hired was a British code-breaker named Greg Patterson now working at the IDA.

Patterson possessed a special advantage. As a Brit, trained in the out-of-style methods that enabled British cryptographers to decipher the Germans’ wartime Enigma code, he was aware of new computer-based applications of Bayesian statistics. These were techniques based on the fundamental insight of Rev. Thomas Bayes, an eighteenth-century amateur mathematician that, by periodically updating one’s initial presuppositions with newly arrived objective information, one could continually improve one’s understanding of many matters. For an especially clear account of the history of Bayes’ Theorem, see The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes’ Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant from Two Centuries of Controversy (2011), by veteran science writer Sharon Bertsch McGrayne

In 1992, the cynosure of the Bayesian community was the little group of computational linguists at IBM Corp. that had run rings around a competing team of linguistics theorists working on machine translation – by the simple expedient of feeding into its powerful computers decades of French-English translations of Canadian parliamentary debates. The computers were armed with machine-learning algorithms that had been instructed to search for patterns. Ever-more dependable translation patterns emerged.

When Patterson learned that IBM was reluctant to permit its team leaders to commercialize their discoveries, he hired Robert Mercer and Peter Brown who had been leaders of the team. Laufer had built a platform that permitted trading across asset classes. It turned out that the methods Mercer and Brown brought with them had wide applicability to the enormous streams of financial data that was becoming ever more plentiful. It was at that point that Renaissance Technologies began to overtake its competitors.

Medallion, the firm’s main fund, earned 71 percent on its capital in 1994, 38 percent in 1995, 31 percent in 1996, and a paltry 21 percent in 1997, a bad year. In 1998, though, D.E. Shaw suffered stinging losses, and Long Term Capital management, Simons’ other main competitor, went bust, after Russia defaulted on its government bonds. By 2000, Medallion returned 99 percent on the $4 billion invested with it, even after Simons collected 20 percent of the gains and five percent of the total invested.

Simons and his colleagues had indeed “solved the market,” at least until their competitors got wise to their methods, but the tumult didn’t go away. Mercer and Brown gradually took over day-to-day management of the firm. A couple of disagreeable Ukrainians traders signed on. The Bayesian Patterson departed for the Broad Institute, in Cambridge, Mass., to work on genomic problems. And in 2016, the libertarian Mercer, by now a billionaire himself, turned out to be, with his daughter Rebekah, a major strategist and funder of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Simons forced his resignation from the firm. It all makes for fascinating reading.

At one point, Zuckerman jokes that his next book will be about fortunes made in “the golden age of porn.” He is kidding, and a good thing too. The still-bigger fortune out there is BlackRock, the $7 trillion asset-management firm founded by Larry Fink and partners in 1987, the year of a great “market break,” after which a great deal of modern financial technology took hold. With such a book, covering the rise of private equity firms as well, a basic map of the major features of twenty-first century finance would be complete.

David Warsh, an economic historian veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

Chris Powell: Yale isn't why New Haven is poor

Yale’s OId Campus at dusk

Listening to some of the speakers at the Martin Luther King Day memorial service in New Haven last week, anyone might have thought that Yale University is why the city has so many poor people. Connecticut State Treasurer Shawn T. Wooden was especially overwrought. According to the New Haven Independent, Wooden asked: "Is it fair for a city as poor as New Haven to give a $146 million tax break to institutions as wealthy as Yale University and Yale New Haven Hospital?"

But New Haven doesn't provide that tax break. It's state law that exempts charitable, religious and nonprofit educational institutions such as Yale and its hospital from municipal property taxes. If Wooden, a Democrat, ever dares do more than preach to the choir, he could raise this issue with the governor, also a Democrat, and the General Assembly, which has a comfortable Democratic majority. Yale may be the biggest nonprofit in Connecticut but it's not the only one, and they all enjoy the exemption.

Yes, with an endowment of $30 billion, Yale is a filthy rich nonprofit. The joke is that Yale is a hedge fund masquerading as a university. But Yale is not why New Haven has so many poor people. The university and its hospital provide most of the better-paying private-sector jobs in the city and most of its commerce, cultural life, and appeal to the rest of the world. Without the university New Haven might blow away or be indistinguishable from Bridgeport, which might kill for a "problem" like Yale.

No, New Haven has so many poor people for the same reasons Connecticut's other cities do. The cities have much cheap housing, state welfare policy produces generational dependence instead of self-sufficiency, and state education policy fails to educate the unmotivated, instead keeping them unmotivated with social promotion.

But Yale does pose a special problem for New Haven, just as being the seat of state government poses a special problem for Hartford. Along with ordinary tax-exempt property like churches, university property in New Haven and state government property in Hartford are so extensive as to remove from the tax rolls half the land area of the cities.

While both cities are heavily subsidized by state government, Hartford gets far more. It gets not only the many state government jobs located there but also state payments in lieu of taxes as well as the benefit of state government's outrageous recent assumption of $500 million of the city's bonded debt, whereby state government essentially reimbursed the city for the $80 million baseball stadium it couldn't afford but built anyway as it neared bankruptcy.

By comparison Yale's annual $12 million voluntary payment to New Haven in lieu of taxes is pitifully small.

Speaking in New Haven last week, Treasurer Wooden, the former leader of Hartford's City Council, a stadium advocate, and a perpetrator of the city's insolvency, failed to acknowledge this unfairness.

With $30 billion in its accounts, Yale could afford to make a much larger annual payment to New Haven, which was a pillar of the platform of the city's new mayor, Justin Elicker, in his campaign last year. Indeed, the General Assembly should consider reducing the property tax exemption of any institution that controls such a disproportionate amount of a municipality's land area.

Not that this would improve New Haven much. For unless Elicker can change things, most of the extra money would be used only to increase compensation for employees of the city's incompetent and sometimes corrupt government

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

-END-

'Rest your old bones'

“Maybe tomorrow it’ll warm up a bit eh, old dog friend of mine? Lay down Country Boy and rest your old bones. We’ll go fetch us some work in town tomorrow if the truck starts. Atta boy … lay down there and we’ll day dream a while about going down to Florida to live next winter. Meanwhile, well meanwhile. ..you know … we’ll just … listen to the fire… And … be warm….”

— “From Vermont Country Winter Memories,’’ by Robert A. Dufresne

.

Llewellyn King: Hydrogen is back as the clean fuel of the future

Hydrogen as a clean fuel is back with a new mission and better ways of producing it.

Jan Vrins, a partner in Guidehouse (formerly Navigant), a leading consulting firm, says hydrogen is a critical component in the carbon-free future of electricity. He told a press event at the National Press Club in Washington that the role of hydrogen as a storage medium as well as a clean fuel will be vital going forward.

Vrins, who heads a team of 800 consultants and researchers at Guidehouse, told reporters that Europe is ahead of the United States in the new uses of hydrogen and in offshore wind development as a hydrogen source. The two are linked, he said, and hydrogen will grow in importance in the United States.

In the bleak days of energy shortage in the 1970s and 1980s, hydrogen was hailed as a magical transportation fuel. Cars would zip around with nary a polluting vapor, except for a drip of water from the tailpipe.

But this white knight never quite got into the saddle. Hydrogen wasn’t easily handled, wasn’t easily produced and wasn’t economically competitive.

Now hydrogen is back as a carbon-free fuel — a means of sopping up excess generation from wind and solar, when production from those exceeds needs, and as an alternative source of energy storage besides batteries.

In theory, hydrogen may yet make it in transportation via fuel cells. But that puts it in competition with electric vehicles for new infrastructure.

Unlike the 197os and 198os, today there is natural gas aplenty for producing hydrogen. Vrins calls this a “bridge” until hydrogen from water takes over.

Hydrogen doesn’t have the same properties as natural gas, and these must be accounted for in designing its use. It has greater volume than an equivalent amount of natural gas and it’s very volatile. But it can make electricity through fuel cells or burning.

Hydrogen isn’t found free in nature, although it’s the world’s most plentiful element — water is made of hydrogen and oxygen. To get hydrogen, coal or natural gas must be steam-reformed, or it can be extracted from water with electrolysis — a development that isn’t missed on companies like Siemens which makes electrolyzer units. Siemens is a leader in a field that is fast attracting engineering companies.

Hydrogen needs special handling and must be engineered into a system. It can’t be treated as being a one-for-one exchange with natural gas at the turbine intake. It has a lower energy density which means it must be stored under pressure in most instances.

Adam Forni, a hydrogen researcher at Guidehouse with an extensive background in natural gas and hydrogen, told me the emphasis today is on reforming natural gas and desulfurizing it in the process with carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) technology. This gas is known as “blue hydrogen,” as opposed to gas from electrolysis which is known as “green hydrogen.”

Green hydrogen is the long-term goal of Guidehouse’s Vrins and his team. It makes alternative energy more efficient.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power has announced it will convert an 1,800-megawatt coal-fired power plant located in Utah to 800 megawatts of all hydrogen. Initially, the plant will burn 70 percent blue hydrogen and will convert to 100 percent green hydrogen by 2045.

But even blue hydrogen with CCUS is a clean fuel, emitting no carbon. Natural gas when burned emits about half the carbon of coal; blue and green hydrogen, zero.

At the Washington press event, Vrins said hydrogen will help in the creation of microgrids which are the coming thing as utilities reorganize themselves. He said natural gas could be piped to the site and then reformed into hydrogen or, better yet, green hydrogen could be made on-site with the surplus electricity from windmills and solar installations.

Vrins sees a future when the grid or microgrid doesn’t need all the power being produced it can be diverted to electrolyzing water and making hydrogen, thus acting as an energy storage medium with greater versatility than batteries. Batteries draw down quickly, whereas hydrogen can be stored in quantity and used over time, as natural gas is today.

Hydrogen is one of the tools as utilities go green. It’s back all right.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

This email was sent to rwhitcomb51@gmail.com

why did I get this? unsubscribe from this list update subscription preferences

White House Chronicle · 125 Providence Street, Suite S302 · West Warwick, RI 02893 · USA

ReplyForward

The foundational Mass. fish story

The Sacred Cod is a four-foot eleven-inch carved-wood effigy of an Atlantic codfish, "painted to the life", hanging in the Massachusetts House of Representatives chamber of Boston's Massachusetts State House— "a memorial of the importance of the Cod-Fishery to the welfare of this Commonwealth" — in its first 200 years.

“As for what you're calling hard luck - well, we made New England out of it. That and codfish.’’

— Stephen Vincent Benet (1898-1943), poet, short story writer and novelist. He is best known for his book-length narrative poem of the American Civil War John Brown's Body (1928), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, and for the short stories "The Devil and Daniel Webster" (1936) and "By the Waters of Babylon" (1937). He’s buried in Stonington, Conn., where he owned an historic house.

Providence's 'Great Streets' initiative

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

PROVIDENCE — Following a year of community engagement, the city’s “Great Streets’’ initiative has established a framework for public-space improvements to ensure that every street is safe.

City officials said the plan’s creation was informed by insights generated “from thorough analysis of crash data, traffic calming requests, and housing and transportation figures.” According to the city, the 94-page plan outlines “a bold vision for the future of Providence’s largest public asset, its streets.”

“Great Streets rebalances the public space of our streets to meet the needs of all residents,” said Bonnie Nickerson, the city’s director of planning and development. “It’s a new approach to how we invest in Providence that will have a long-term impact on safety, equity and resilience.”

Covering about 13 percent of Providence’s total land area — some 1,500 acres — streets play a central part in the city’s neighborhoods. A key strategy outlined in the plan is reducing household transportation costs by making it more convenient for people to use and access affordable transportation options such as walking, riding bicycles, and public transit.

Other goals include improving traffic safety and personal safety within the public realm for people of all ages, abilities, and economic statuses, lowering greenhouse-gas emissions, and improving public health. According to the World Health Organization’s 2018 Global Status on Road Safety report, traffic-related crashes are the No. 1 cause of death in children and young adults aged 5-29.

The plan complements the work of ongoing infrastructure projects outlined in the city’s FY2020-FY2024 Capital Improvement Plan (CIP), signed by Mayor Jorge Elorza in early January. Over the next five years, the CIP identifies nearly a $20 million investment in Great Street initiatives. These improvements include: streetscape and placemaking projects; safety improvements to make streets and intersections safer for people walking and riding bicycles; traffic calming to reduce speeding and cut-through traffic; and the creation of a “spine” network of urban trails that connect every Providence neighborhood.

These improvements will bring 93 percent of residents and 95 percent of jobs within easy walking distance of the Urban Trail Network, according to city officials. This is a significant increase compared to the 21 percent of residents and 37 percent of jobs within easy walking distance of the existing network.

According to the city, urban trails are on or off-street paths that are “safe, comfortable, and easily accessible for people of all ages and abilities.” On busy streets, urban trails are fully separated from vehicle traffic. In other instances, off-road trails and paths such as the Blackstone Bike Path and the Woonasquatucket River Greenway serve as part of the Urban Trail Network.

Always pick the richest parents you can find

Too small for the Sussexes? The great hall in The Breakers, the old Vanderbilt mansion in Newport

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Of course, things are always rigged for the rich and well-connected –why complain that rocks are hard! -- but since the Second Gilded Age started back in the ‘80s we set new levels of goodies for the privileged. Consider Hunter Biden’s stretch of getting paid $50,000 a month for sitting on the board of a Ukrainian gas company although he knew little about that industry. Then we have Chelsea Clinton, the only child of Bill and Hillary, pulling in $9 million in salary and stock since 2011 for sitting on the board of the Internet investment company IAC/InterActive Corp., which happens to be controlled by mogul Barry Diller, a pal of the Clintons.

Still, that’s bush league compared to the Trump Family’s profiteering off Daddy’s occupation of the Oval Office and steering vast sums of foreign and U.S. government money to Trump resorts and hotels. The Constitution’s Emoluments Clause? What’s that?!

And now the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have decided they want to make a killing, er be “financially independent,’’ and withdraw from many of their tedious public duties as Royals. Are Sussex sweatshirts coming up? Too tacky! Think luggage. There’s a push on to get them to move to Rhode Island. Maybe a shingle-style mansion near Taylor Swift’s pile on Watch Hill?

Art and civics in Peterboro

“Hidden Myth” (collagraph, wax, tape), by Soosen Dunholter, a Peterboro, N.H.-based painter.

Peterboro, in New Hampshire’s (Mount) Monadnock Region (named for the mountain that has long been reputed to be the second-most climbed in the world, after Mt. Fuji), is famous for the many writers and other artists who have lived and/or worked there. That’s party because of the MacDowell Colony, which has been a cozy and supportive place for writers, composers and visual artists to work since its founding, in 1907. One of its writers was Thornton Wilder, who is said to have based the community, Grover’s Corners, in his famous play Our Town on Peterboro. Peterboro is still more rural than not, but Boston’s exurban sprawl is pushing toward the town, which remains a weekend and vacation home for quite a few affluent people.

Peterboro is well known for its engaged and well-informed citizenry.

Next door is beautiful Dublin, the highest town in New England and the site of the headquarters of Yankee Inc., which publishes the eponymous magazine and the Old Farmer’s Almanack and has a couple of glorious lakes. For many years Dublin hosted Beech Hill Farm, a substance-abuse (mostly of alcohol) facility in an old mansion on top of Beech Hill that drew a fair share of celebrities who needed to dry out. The property is no longer used for that.

Children’s arts parade in Peterboro.

Bond House at the MacDowell Colony

The top of Mount Monadnock on a typically crowded day in warm weather.

Trying to get at time in Rockland

“Continuum (Magenta)’’ (oil on linen — detail), by Grace DeGennaro, at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland, through Feb. 23.

The gallery says:

”This exhibit is the second in an ongoing series at CMCA that addresses common themes in contemporary art. The biennial series began in 2017 with ‘Materiality | The Matter of Matter’ and continues to ‘Temporality’ with the work of 14 contemporary artists. ‘Temporality’ explores our deepest questions about the concept of time: What is time, how do we measure it, how can we ascribe value to it? The featured artworks offer their own answers to these questions using painting, photography, sculpture, installation, video and other media. However, one can say that time itself is also a medium in these pieces, as the exhibit webpage points out: The only sure things about time are that "artists need time to make their work and viewers need time to look. ‘Temporality,’ therefore, asks the viewer to slow down and take the time to consider the questions it asks about time and perhaps find the answers.’’

xxx

Rockland, on Penobscot Bay, is a fascinating place — a celebrated arts center, a fishing port and a major recreational-sailing center. Besides the CMCA (designed by the internationally known architect Toshiko Mori), the town is also home to the Farnsworth Museum of Art, which has paintings by Andrew Wyeth and other well-known New England artists. It hosts the Maine Lobster Festival, held annually in honor of the town's primary export: lobster. Rockland's downtown has many small shops, some very charming, including coffee shops, book stores, art supply stores, restaurants, organic markets, computer repair and toy stores. The city's dramatic breakwater, built in the 19th Century, draws tourists.

Downtown Rockland

Some of Rockland’s waterfront

— Photo by Jeff G.

'A classical tone'

"There is about Boston a certain reminiscent and classical tone, suggesting an authenticity and piety which few other American cities possess."

— E.B. White (1899-1985), the famous essayist and children’s book author. He’d often go through Boston to take the old Boston & Maine Railroad to approach his place on the Maine Coast.

Chris Powell: Past time to reject the transgendering racket

A man who decided he wanted to be a woman

Few people care if men want to dress up as women or women as men. For most such people it's not a lark but a deep psychological issue likely to cause them some trouble throughout their lives. They are entitled to be comfortable in their own skin.

But everybody else is entitled to care when this imposture infringes on gender privacy in bathrooms and competition in sports, areas where individual lives inevitably affect other lives.

If the imposture of transgendering is skilled enough, it won't be noticed in a bathroom. But it can't help be noticed in sports, for physical gender is simply biology and men tend to be larger and stronger than women. Calling a man a woman doesn't make him one physically. Gender division in sports was instituted because biology cannot be denied, even though politically correct pretense lately has been trying to deny it in Connecticut and throughout the country and to intimidate doubters out of asserting the obvious.

But here and there some people are not being intimidated. A few state legislators around the country have even introduced bills to reject the transgendering racket and keep boys and girls in their proper divisions in public school sports.

At a hearing on such legislation in New Hampshire's House of Representatives this month, a girls cross-country and track and field coach from West Hartford, Meredith Gordon Remigino, bravely decried the unfairness increasingly inflicted on young female athletes by the transgendering racket. Remigino noted that some males who are only ordinary athletes in male events now impersonate females and vanquish all competition there. Indeed, for several years now this has been happening in Connecticut foot races.

"We know firsthand that fairness and equality require sports to be categorized and differentiated based on sex, not based on gender identity," Remigino told the hearing.

Three Connecticut young women athletes have complained to the U.S. Education Department's Office of Civil Rights about the state policy that is letting transgender boys dominate girls track and field events in the state. Maybe federal action will induce the state to drop its political correctness, face reality, and change the policy, if only until political correctness returns to federal administration.

But most people in Connecticut probably will remain too intimidated to complain about this unfairness until some young man who can't quite make it on the University of Connecticut men's basketball team decides that he's really a woman and joins the women's team, or until the women's basketball teams at Notre Dame, Tennessee, or Baylor come to UConn fielding players with male chromosomes.

That might be Connecticut's long-overdue moment from "The Emperor's New Clothes."

After all, if even in athletics gender is merely a state of mind, not biology, what about age too?

Surely there are some old men who were never more than mediocre athletes but who feel young at heart and would love to play Little League baseball again against 12-year-olds and swing for the shorter fences. These old men would be no more out of place than the biological males who are expropriating female prizes.

The author of 1984, George Orwell, saw such nonsense coming 80 years ago. He wrote: "We have now sunk to a depth at which restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men." As Coach Remigino showed, women too.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

The tamed with the untamed

Photo by Vaughn Sills in her Feb. 5-March 1 show “Inside Outside’,’ at Kingston Galley, Boston. It’s a group of photographs that blend still life and landscape, such as bouquets with landscapes that Sills creates of Prince Edward Island, her mother’s home, in a juxtaposition of highly cultivated nature versus the untamed natural world. The gallery says: “Domestic life is represented by garden-grown flowers in vases, alluding to the traditional notion of women’s work in gardens and in the home; while the outside world is seen in the images of sea and land. Mortality and beauty are explored in a secondary layer of this body of work. The Prince Edward Island landscapes and seascapes are part of a series about grieving for Sills’s mother, a woman noted for her remarkable beauty. They represent expressions of sadness, love, memory and connection. Flowers, with their ephemeral beauty, are reminders of death and contrast with the feeling of infinitude implied by the sea and rolling hills. A third layer speaks to the artist’s concern for the planet. She is attuned to the climate crisis implied in these photographs. Local streams and ponds are polluted by the farmer’s field featured in her work, and the flowers purchased for the photographs are transported via trucks that contribute to carbon emissions, a factor in the rise of sea levels.’’

Campaign for Common Sense

Watch for action by the new national reform project called Campaign for Common Sense, started by the legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good. The project’s Web site will be up soon. One of the organization’s key goals is to start rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure by cutting red tape.

WHOI vehicle uses robotic arm to take sample on seabottom

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) used a recently developed hybrid vehicle to take the first sample from the sea bottom by a robotic arm.

The vehicle, Nereid Under Ice (NUI), was operated remotely by scientists off the coast of Greece to explore an active submarine volcano, as part of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Planetary Science and Technology from Analog Research (PSTAR) interdisciplinary research program. Only slightly smaller than a Smart Car, NUI used artificial intelligence to determine which sites to visit and when to take samples autonomously. NUI is one of the first results of a larger push for automation technology, with further developments promising results in not only independent ocean research, but for NASA’s work in exploring other planets.

“For a vehicle to take a sample without a pilot driving it was a huge step forward,” says Rich Camilli, an associate scientist at WHOI leading the development of automation technology. “One of our goals was to toss out the joystick, and we were able to do just that.”

Jungle in the Bronx

“New York Botanical Garden (in the Bronx)’ ‘ (gelatin silver print), by Peter Moriarty, in his show “Peter Moriarty: Warm Room,’’ at the Iris & B. Cantor Art Gallery, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, through Feb. 29.

The gallery says:

”With his portfolio of gelatin silver prints, Peter Moriarty explores the architecture and collections of a series of historic European and American greenhouses. Taken over the course of more than 20 years, Moriarty's evocative works explore the interactions of familiar architectural forms with the lush, exotic, organic, and often disorienting collections housed within.’’

The gallery says:

”With his portfolio of gelatin silver prints, Peter Moriarty explores the architecture and collections of a series of historic European and American greenhouses. Taken over the course of more than 20 years, Moriarty's evocative works explore the interactions of familiar architectural forms with the lush, exotic, organic, and often disorienting collections housed within.’’

Will these sculptures preside over the (Conn.) Thames?

New London from Fort Trumbull

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I love this sort of project!

Killingworth, Conn., sculptor Renee Rhodes wants to create two 30-foot-tall bronze statues of female figures, one on the Groton side and the other on the New London side of the Thames River. Some readers may have seen her very popular life-size bronze sculpture of Athena in downtown New London.

I hope that her Thames project happens. Such creations tend to cheer the traveling public and arouse local pride

Pass through after plowing and primary

An apple orchard in Hollis, N.H.

"You don't want someone to think you're from New Hampshire, because who cares about New Hampshire? You're basically just a pass-through.''

-- Timothy Simons, actor and comedian. He’s from Maine.

Historical marker in Concord

'Between pole and tropic'

“Midwinter spring is its own season

Sempiternal though sodden towards sundown,

Suspended in time, between pole and tropic.’’

— From “Little Gidding,’’ by T.S. Eliot