Industry and high culture in Worcester

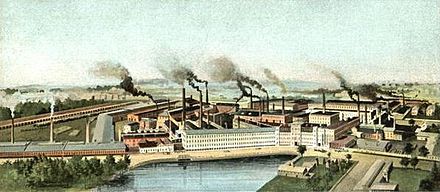

American Steel & Wire Company, circa 1905, in Worcester. At its height, the company employed thousands.

To many, Worcester may be best known as an old industrial city, with a particular focus on things made out of metal. Indeed, some people used to call it "The Pittsburgh of New England.''

Bu it also has such aesthetic and educational delights as many fine examples of Victorian-era mill architecture and Victorian mansions as well as such treasures as the American Antiquarian Society, the Worcester Art Museum, the Higgins Armory Museum, the Mechanics Hall concert venue, the EcoTarium and Clark University, where Freud gave his only lecture in America and from which came Robert Goddard, the pioneer of rocket technology. Then there's a leading Catholic institution, the College of the Holy Cross, up on a windy hill.

Many of the rich local industrialists were avid patrons of the arts and education even as some of them were happy to employ children in their factories.

And there's the Worcester Music Festival, allegedly the oldest music festival in the U.S., the Canal Festival (there are canals in Worcester dating back to Industrial Revolution days) and Rock and Shock

Beautful Mechanics Hall, in downtown Worcester.

In city redevelopment, go organic

American Steel & Wire Co., Worcester, about 1905. Worcester used to be nicknamed "The Pittsburgh of New England''.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

The Worcester Telegram ran a boosterish editorial on Oct. 22 about its downtown renaissance.

Among its points, which folks in other old New England cities should remember:

“{E}xisting buildings are also being transformed. As opposed to large, government-driven urban renewal projects that once cut off entire neighborhoods and laid waste to broad swaths of midcentury Worcester, what we’re seeing now is different. It’s different in the number of independent private developers, all seeing opportunity here and now, who in their own ways are driving a renewal of the city.’’

“This isn’t some giant urban renewal project. It’s an organic renewal.

“Organic in that so many developers have discovered opportunity here. But a renewal that is far from accidental. It’s not happening on its own. It’s a product of what came before, and of city leadership in both the public and private sectors.

“The fact that all this development is not reliant on a single, large developer or a giant government project, as has happened before and elsewhere, may be its greatest strength. That so many individual developers, all with a vision and a belief in the city’s future prospects, and with the resources and willingness to put those resources at risk, is the sort of development that drove the emergence of Worcester into an industrial giant. Failure by any single developer doesn’t doom the entire enterprise. ‘’

In other words, don’t depend on a few big developers, or one big company moving in (e.g., Amazon), to turn your city around. Diversify your economy, fix the city’s physical infrastructure and improve the schools. Companies come and go, with a moment’s notice.

Maybe city managers can govern better than mayors

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

Worcester’s bonds are rated Aa3 while Providence’s are a much lower Baa1. Worcester is in most ways a considerably less important city than Providence, and with a smaller economic and institutional base.

So what explains the rating difference? I’d guess Providence’s continuing failure to get its pension and other employee costs under control is the biggest factor. That’s at least in part because Worcester has a city manager system, which encourages professional (“technocratic’’) administration with far more insulation from political and special-interest pressures (e.g., municipal unions) than you get in a traditional mayoral system like Providence’s. The lower the bond rating, the higher the interest rate that a city must pay and the higher the taxes to pay the bond interest.

Desperately chasing business

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

Worcester is putting in its own bid to get Amazon’s “second headquarters’’ in addition to being part of the Massachusetts application to the Seattle-based monster. Not a bad idea – two lottery tickets instead of just one. But it is hard to see Worcester having the infrastructure, techno personnel and tax-break resources to lure Amazon and what the company asserts will be 50,000 new employees. Maybe, like Providence, they could get a couple of small slices of the pie if Amazon picks Boston. (I still bet on Austin.)

xxx

I ask again: Why does Massachusetts, a rich state, refuse to help pay to build sports stadiums for private companies while much poorer Rhode Island is looking to cough up such money for the Pawtucket Red Sox?

Worcester pitches to PawSox

Downtown Worcester.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

Worcester officials are quietly reaching out to Pawtucket Red Sox owners about moving the franchise there, perhaps at the vacant Wyman-Gordon Co. property downtown. Presumably they’d pitch the old industrial city’s location well within the Boston Red Sox orbit, its slowly reviving downtown and its commuter rail service to and from Greater Boston.

But the Worcester metro area is not on the Main Street of the East Coast, Route 95, as is Pawtucket, and, at 924,000 doesn’t have the population size of the Providence metro area, 1.6 million. And many simply find the Providence area more interesting, or at least more complicated.

Further, however, much as Worcester officials and downtown business leaders might like to get the PawSox franchise and a stadium to go with it, public support would probably fade if and when the PawSox made their formal proposals for aid from the state and the city, especially if state and local tax revenues fall over the next few months. And foes would cite as warning the infamous cost overruns and other hassles in the construction of Dunkin’ Donuts Park in fiscally sick Hartford, the home of the hideously named Hartford Yard Goats, a Colorado Rockies farm team. Building baseball stadiums is not for the faint of heart!

Anyway, the PawSox owners clearly want to stay in Pawtucket.

Look for a better owner of Worcester's Union Station

Worcester’s glorious Union Station should become increasingly important as more and more people seek to use mass transit. But it might be much better run if owned either by a private entity or by some new public-private entity, such as Amtrak, and not by its current owner, the Worcester Redevelopment Authority. At least the grossly underfunded Amtrak, which has never been more patronized than now, knows the transportation business. And the Northeast Corridor is Amtrak's big money maker.

Certainly the size and location of Worcester and the station’s size and beauty could make it into the nexus of interior southern New England. Consider such splendid company-owned venues for the public as Madison Square Garden.

In some ways Worcester is wonderful

Inside the Worcester Art Museum, the second-largest art museum in New England. It was founded in 1898, in Worcester's industrial heyday.

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s Dec. 15 “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com.

Worcester, which I have always seen as “New England’s Pittsburgh’’ because of its metal-related companies, is enjoying a revival, including in manufacturing, which first made it rich. Indeed, in a recent three-year period, the Worcester area’s manufacturing sector grew 15 percent as measured by revenue.

The city also has numerous higher-education institutions that are contributing to its renaissance, but probably the University of Massachusetts Medical Center has been the most important, helping to turn the city into a major biomedical center. Further, there are big redevelopment projects underway downtown. Some of the revival is simply the westward expansion of the booming Greater Boston economy but some of it is due to healthy homegrown boosterism.

And there are such distinguished cultural centers as the Worcester Art Museum and some gorgeous suburbs, such as Princeton and Harvard, Mass.

Worcester has plenty of problems, of course, but its recent success is edifying for other mid-size cities, in New England and beyond. If only its winters were tad milder. Some of the city is around 1,000 feet above sea level, which makes for considerably more snow and ice than in, say, Boston, Hartford and Providence.

By the way, Worcester is somewhat misleadingly called “the second-biggest city in New England,’’ with a population of about 181,000, compared to Providence’s about 180,000, but the latter’s metro area has many more people than Worcester’s – about 1.3 million compared to Worcester’s about 800,000. Worcester proper has far more square miles, at 38.6, than Providence’s 20.6.

Like Boston and some other Colonial-era towns, Providence’s area is small because other towns in its area were quickly incorporated well before Providence could absorb their acreage as its population and economy boomed in the 19th Century. Consider that while the population of Boston itself is about 667,000, its metro area has about 4.7 million people (or "souls,'' as people used to say).

Out west, on the other hand, cities, such as Phoenix, could easily gobble up vast stretches of unincorporated and under-populated land – much of it effectively wasteland.

Robert Whitcomb: Private-sector passenger rail?

Since the disappearance of private-sector passenger rail service decades ago, intrepid entrepreneurs have tried to bring it back. None have succeeded.

However, in some densely populated places, passenger rail has even thrived in the public sector, at least as measured by passenger volume. This mostly means Amtrak in the Northeast Corridor and several major cities’ long-established commuter-rail networks. But new commuter rail is also catching on in some unlikely places, including such Sunbelt cities as Dallas and Phoenix, which now have popular light-rail systems.

Now, with an aging population, the proliferation of digital devices that many people would prefer to stare at rather than at the road and the increasing unpleasantness of traveling on America’s decaying highway infrastructure amidst texting and angry drivers, private passenger rail looks more capitalistically attractive.

Consider All Aboard Florida, a company that plans to offer extensive rail service starting in 2017. It will connect Miami and Orlando in just under three hours, with stops in Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach.

Its advertising copy eloquently describes commuter rail’s allure in populous areas: “{Y}ou can turn your stressful daily {car} commute into a productive or peaceful time by choosing to take the train instead of driving your car. By becoming a train commuter, you’ll also help the economy and environment while you’re at it.’’

Southern New England, like much of Florida, is densely populated, with some unused or underused rail rights of way. So our entrepreneurs occasionally propose private passenger rail for routes not served by Amtrak or such regional mass-transit organizations as Metro North and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

Consider the Worcester-Providence route, on which a new company called the Boston Surface Railroad Co. wants to start operating commuter rail service in 2017 on the (now freight-only) Providence and Worcester Railroad’s tracks. Most of the commuters going to work would be traveling from the Worcester area, via Woonsocket, where there would be a stop, to Greater Providence. While Providence itself has fewer people -- about 178,000 -- than Worcester (about 183,000), the two-state Providence metro area -- about 1.6 million -- is much bigger than the latter’s metro area’s about 813,000.

The density is there for rail service. That the region has an older population than the national average and frequent bad winter weather also give the idea a lift.

But the old rail line needs to be upgraded if the trips are to be made fast enough to lure many travelers. The company hopes to offer a one-way time of about 70 minutes on a route that you can drive in about 45 minutes in moderate traffic and clement weather. That could be a killer.

What this project and similar ones need is new welded track, rebuilt rail beds (with help of public money?) and some entirely new routes to make service competitive with car-driving times. We need more passenger and duel-purpose passenger-freight rail lines, not more highways. But getting them will be tough in a country that so blithely tolerates crumbling transportation infrastructure and has a deeply entrenched libertarian commuting habit of a single person driving long distances to work. Unless gasoline tops $5 a gallon and stays there for at least a year, it’s hard to see millions of Americans deciding that they’ll quit their cars to take the train.

Still, I applaud the project’s CEO, Vincent Bono, and hope that thousands of commuters will give his railroad a try. While the trip would be long, think of how much uninterrupted Web surfing (free Wi-Fi!), reading and snoozing you could get on these trains, with their reclining seats.

xxx

An Aug. 10 USA Today story was headlined “Smaller cities emerge among top picks for biz meetings.’’ Depressingly, Providence was not on the list of the top 50 places for “meetings and events’’ in 2015, say evaluations by Cvent. But many far less interesting and attractive places were.

The reasons probably include Rhode Island’s under-funded and balkanized self-promotion and the long delay (now finally being addressed) in building a longer runway at T.F. Green Airport.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), a Providence-based editor, writer and consultant, oversees newenglanddiary.com and is a partner in Cambridge Management Group, (cmg625.com), a healthcare consultancy, and a fellow at the Pell Center. He used to be the editorial-page editor of The Providence Journal and the finance editor of the International Herald Tribune, among other jobs.

Cleaning up the Blackstone River naturally

Living Systems Laboratory built in 2013 for progress and profits cleans 10,000 gallons of river water daily.

BY CATHERINE SENGEL, for ecoRI News

SOUTH GRAFTON, Mass.

The heads of a few dozen turtles bob up from the waters surrounding a floating island along a verdant stretch of the Blackstone River. Five years ago, this expanse beside the Blackstone Canal and below the Fisherville Pond Dam was a dead zone, devoid of aquatic life.

But thanks to an experimental Living Systems Laboratory built in 2013 on the former site of the historic Fisherville Mill, 10,000 gallons of water are cleaned daily of the contaminants that once choked all living matter. By reintroducing the biological diversity once part of the ecosystem, the operation is restoring vitality to the river at a pace a thousand times faster than nature.

In addition, owner and developer Gene Bernat hopes it will offer an unparalleled education on our relationship with our environment.

“All of the different biological kingdoms that we employ here provide natural solutions to more than 200 years of incremental problems,” Bernat said during a recent tour of this lab. “It’s a visual roadmap of how we get from an extractive economy to a sustainable economy, and the premier experience in ecological literacy that you can find in the Northeast.”

Part of a string of mill villages in the valleys below the river’s headwaters in Worcester, Fisherville was home to one of the largest mills on the Blackstone River, supplying wool to the world from the early 1700s. In the mid-19th Century, a network of 48 granite locks and steps channeled flow along the Blackstone Canal, allowing the visionaries of America’s Industrial Revolution to power their mills and move goods in and out between Worcester and Providence.

Over the centuries, the river went from supplying food and canoe transport between communities for Native Americans and early settlers to providing energy for manufacturing and finally a convenient disposal place for waste.

In 1999, the 300,000-square-foot Fisherville Mill burned, sending deposits of asbestos to coat yards as far away as Hopedale and adding to an already toxic legacy. When talk turned to cleaning up the remaining pile of mill rubble after eight years, Bernat’s Fisherville Redevelopment Co. teamed with the town of Grafton to apply lessons learned elsewhere about resource restoration combined with an economic incentive.

The land would be cleared for Mill Villages Park, a development of 240 residential units with 60,000 square feet of commercial space. Site remediation was just finishing when the market collapse put a halt to building, but work on the Living Systems Laboratory moved forward.

Bernat, from three generations of textile makers, grew up dividing his summers between work in the Bernat yarn mill in Uxbridge and the woods of the family farm in Grafton. His time in forestry had sparked an interest in natural systems and resource management. To his reasoning, there was no question that the property would be a long-term durable asset for the Blackstone Valley and the community, with or without housing and shops.

Situated within the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor, the Fisherville Mill site is on one of largest existing water areas on the Blackstone Canal, with remnants of historic locks, a 200-foot-wide step dam and a continuous perennial waterfall from days of industrial development. Fisherville Pond is one of the last mill ponds on the river, and a premier migratory waterfowl nesting site.

In addition to large expanses of mostly untouched floodplain, the surrounding area includes still-intact mill villages, including mill housing. Two other yarn mills within a quarter mile, in Saundersville and Farnumsville, put Mill Villages Park and Pavilion at their center.

Rather than dwell on impediments to park progress, Bernat began to consider the entire area as a living, teaching landscape.

A consortium of area universities, including Brown, Clark, Tufts and Worcester Polytechnical Institute, along with the Blackstone Headwaters Coalition, Blackstone Heritage Corridor Coalition and Mass Audubon, joined Bernat to launch the Living Systems Laboratory. John Todd Ecological Design (JTED), a global pioneer in the use of natural systems to remove contaminants from water, was enlisted to help customize operations to the challenge at hand.

On the premise that one organism’s waste is another organism’s food source, JTED used a combination of tanks and aquatic cells in its bioremediation to mimic natural processes.

Bins of wood pellets and water support the growth of fungi that consume petroleum hydrocarbons.

In a temporary, riverside greenhouse, water from the Blackstone is pumped through a series of bins. Filled with wood pellets and water, they support growth of a variety of fungi that consume oil residues.

From there, the water moves through a progression of six tanks, or “aquatic cells,” where native plants, shrubs and trees hang on fiberglass racks, roots reaching down to support worlds of algae, zooplankton and other microorganism which in turn nourish snails, clams and fish.

“By introducing the contaminants, we’re telling nature to try and use them,” Bernat said.

The older the system, the more mature and diverse the biology, the better it is at treating waste products, according to Bernat. Species purposely excluded in construction of the ecological incubator introduced themselves into bins and tanks, he noted, proving that every species has a purpose in nature.

The concept is new and radical and has enormous potential. The first year of operation saw a more than 95 percent drop in petroleum hydrocarbons in water samples from input to outflow back into the river. Water clean enough to drink is now packed with beneficial organisms and life forms that digest oils, dyes and contaminants, and returned to the Blackstone River.

Canal restorers made of bamboo and local vegetation float on the Blackstone, supporting ecosystems once abundant in the river.

Taken together, bins and tanks create a circulating loop — a stream within the stream in which water is purified at a rate of 10,000 gallons a day and the canal is re-seeded with healthy ecology. In the river, constructed bamboo “canal restorers” — some surrounded by oil booms to collect slick — float upstream of an old granite bridge collecting and consuming additional pollutants.

“Everything that occurs in here in this greenhouse is happening in the natural world around us without our intervention,” Bernat said. “But with our intervention, we make it over a thousand times as effective in cleaning up contaminants as the natural world does itself.”

The site has already received both local and international attention for its community-designed Mill Villages Park and the chemical-free remediation. Beyond the value of an ecological wastewater treatment system, Bernat champions the educational potential of the operation.

From the obvious to the microscopic, there are centuries of historical, cultural and biological lessons on the past, present and future for levels from preschool to Ph.D.

Students from Worcester Tech are duplicating the process in a greenhouse they built at their high school to study bioremediation. Senior fellows, researchers and policymakers from the University of Rhode Island Coastal Institute visited to learn about the system’s EcoMachine™ design.

In December 2014, the town was awarded a $10,000 grant by the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor for the Fisherville Mill Redevelopment site. The money will be used to create a teaching landscape, build a more permanent greenhouse, and develop educational materials and programs focused on the ecology and industrial history of the Blackstone River Valley.

Students from the Conway School of Landscape Design created a vision plan for the site that will, in time, include nature paths, a boat launch, an amphitheater, exhibit space and a model of cross-discipline education. Plants are being introduced into aquatic labs in the hope that flowers can be grown and sold commercially as an added economic component.

“What we learn here and teach here is applicable to the environment no matter where,” Bernat said. “Rather than a scholastic understanding of how things work, you should be able to walk through the site and really begin to grasp the miracles of nature and how we help that process or how we’ve damaged that process through our past activities.

“If you look at rivers almost without exception in the industrialized world, they really are the sewer system of our society.”

One of the many lessons the river offers is that there is no such thing as “away” when it comes to waste. Whether buried in a landfill or dumped in a river to be carried out to Narragansett Bay and beyond, that garbage still exists along with its long-term consequences.

“There’s an intimate dynamic between humanity and our environment ... we are all canaries in a coal mine,” Bernat said. “We see animals dying and habitat being destroyed and we just think it’s the price of progress.”

The Living Systems Laboratory is a vision for progress and profits without environmental cost, according to Bernat. He’s excited to announce that frogs finally returned to the river this year.

“If we’re going to survive, we have to start looking at water in a completely different way,” he said. “The park vastly improved South Grafton, and now we have the potential to do so much more.”