James P. Freeman: Questions for two GOP candidates eager to take on Senator Warren

It’s been said that you can’t split dead wood.

Surprisingly, the Massachusetts Republican Party, usually barren tundra when competing in statewide races, is fielding a forest of formidable candidates to challenge Democrat incumbent U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren in 2018. Two of them — Beth Lindstrom and John Kingston — are twin oaks of establishment politics and just recently announced their candidacies. They are worthy contenders, nevertheless, and deserve recognition.

Lindstrom is a Groton resident. She was executive director of the Massachusetts Lottery in the 1990s and, later, worked as director of the Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation while Mitt Romney was governor. She also managed Scott Brown’s successful U.S. Senate campaign during the 2010 special election and is the first female executive director of the state Republican Party. Lindstrom appeared, notably, on television ads in 2014 for a super PAC backing Republican Charlie Baker. She announced her candidacy on Twitter on Aug. 21, with a formal announcement on Oct. 14.

John Kingston is a Winchester resident. He is a rich businessman and philanthropist. He was a lawyer at Ropes & Gray and went on to hold leadership positions at Affiliated Managers Group, the global asset-management company. He serves on the board of the Pioneer Institute, the public-policy organization, and is a member of the American Enterprise Institute, the Washington D.C., think tank. He is also involved with several charitable endeavors. Active in state and national Republican Party affairs, Kingston was part of Mitt Romney’s 2008 presidential campaign and was an executive producer for the 2014 documentary film Mitt. He formally announced his candidacy on Oct. 25.

So, before debate moderators and deceitful mainstream media can ask them their favorite color or when they last wept, they should be asked serious questions. Herewith are some to ponder:

1. Your mentor, Mitt Romney, was mocked during the 2012 presidential campaign for suggesting that Russia was the biggest geopolitical threat to the United States. Considering the allegations that Russia meddled in the 2016 election, is Russia today still the biggest threat to American security? Why or why not?

2. What should be done to mitigate North Korean provocations? Can America live with a nuclear-armed North Korea?

3. In May, with over $70 billion in outstanding debt, Puerto Rico filed for bankruptcy (believed to be the largest ever U.S. local government bankruptcy) under Title III of a U.S. Congressional rescue law known as PROMESA. Puerto Rico’s poor fiscal condition, highlighted again after Hurricane Maria, mirrors many mainland municipalities. What should this debt restructuring look like? Do municipal bankruptcy laws need modification given the sheer number of over-incumbered, bankruptcy-prone municipalities?

4. Some would argue that the likes of Google, Facebook, and Twitter are effectively operating as monopolies, and that their size and influence far exceed those of Standard Oil, and AT&T, for instance, which were ultimately broken up. Do the current examples raise anti-trust concerns? Does the Justice Department need to rethink its anti-trust policies?

5. For better or worse, President Trump is the leader of the Republican Party, your party. In what regard is the president doing well? In what regard can the president improve?

6. In Massachusetts, you will not win election without winning over some Democrats. How do you garner their vote? What do you say to Senator Warren’s core constituency, progressive populists, to gain their vote?

7. The commonwealth has one of the highest rates of opioid overdose deaths in the country. This year police in several Massachusetts cities and towns are seeing massive increases, not decreases, in non-fatal overdoses. The rightly called opioid epidemic has been trending for over a decade in the wrong direction. What are your proposals for action? How should state and federal governments better address this matter?

8. The Wall Street Journal reported that Amazon lured 238 bids from cities and regions for its second corporate headquarters. With no public vetting or commenting process, a total of 26 Massachusetts sites are competing for Amazon’s business, which, according to estimates, will bring tens of thousands of jobs to the winner. Is public policy perverted when one of the world’s richest companies is seeking — and will be granted — generous subsidies and tax benefits from these places where there is already high indebtedness, massive unfunded pension liabilities, and where there is need for drastic infrastructure improvements? What are your thoughts on these arrangements?

9. Does Obamacare need to be repealed and replaced? If yes, what are your proposals? If no, what improvements need to be made to make it a sustainable health care system? And looking at health care locally, Romneycare is now eating up close to 45 percent of the Massachusetts budget, prompting state Rep. Jim Lyons to call the budget “an insurance company.” How do you bend the cost curve? Is the expansion of Medicaid slowly bankrupting Massachusetts? How do you finance it on the federal level?

10. Former Sen. Scott Brown said during the 2012 senatorial campaign that he was a “Scott Brown Republican.” He lost by a wide margin. Likewise, both of you have described yourselves as abstractions. (Lindstrom: “a common-sense Republican.” Kingston: “an independent thinker.”) What do you mean by these Twitter-inspired thought bubbles? Do you have better descriptions?

11. Speaking of 2012, Brown and Romney could not decide if they were moderates or conservatives or something else. Lacking such identity probably hurt them. Warren is proudly progressive. What are you? And does it make political and electoral sense to fight a progressive with a conservative?

12. What are your reactions to the Massachusetts Republican Party settling charges for $240,000 in 2015 with Tea Party member Mark Fisher? (He claimed that the party stymied his efforts at getting on the Republican gubernatorial primary ballot in 2014, which raised larger issuers of attempting to purge the party of conservatives.)

13. On March 10, The Boston Globe’s Frank Phillips wrote: “A major concern for the governor’s political team is that the party’s U.S. Senate candidate in 2018 be compatible with Governor Charlie Baker and his political positions.” You both speak of not being beholden to President Trump but you’re both considered insiders in the state Republican Party. How do you refute Phillip’s premise that you are not beholden to Baker? Do you think his team favored the party’s proposal of doubling the number of super-delegates at next year’s nominating convention?

14. Who are your political role models? Why?

15. Has the national legislative branch abdicated its constitutionally prescribed powers to the executive branch? If yes, how do you bring the balance back?

16. Candidate Lindstrom: In the announcement video for your candidacy, you say you are “not a professional politician.” (Technically Olympic athletes aren’t professional athletes either.) Granted, you were never elected to public office, yet a substantial portion of your career has been involved in government. Do you think that the average voter would believe your statement?

17. Candidate Lindstrom: In 2008, Former Republican Lit. Gov. Kerry Healy would have been the first woman elected Massachusetts governor. You would be the first Republican woman elected Massachusetts senator. What advice has she given you?

18. Candidate Kingston: It was reported that you switched party registration last year from Republican to unenrolled and led an effort to create a movement to field an independent candidate in the presidential election. You have lent your own campaign approximately $3 million. You are a harsh critic of President Trump. Candidate Trump also had a history of switching party affiliations and lending his campaign personal funds. Philosophically and operationally, aren’t you behaving like Trump? Why are you running as a Republican and not as an Independent?

19. Candidate Kingston: You made a fortune in the asset-management business and spent a significant amount of your career in financial services. Did Wall Street learn any lessons in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008-2009? What were they? Are Americans more protected from Wall Street shenanigans today than last decade? Should hedge funds, which play increasingly powerful roles in trading and asset accumulation, be taxed and regulated more?

20. Candidate Kingston: In your formal announcement video, you say you are a “different kind of leader.” How so? In a separate statement you also said, “We cannot risk that chance [defeating Warren] on candidates who cannot deploy the resources necessary to win, or on candidates who are unelectable or uninspiring.” Is that an elitist sentiment, and don’t ideas matter too? Are you suggesting that your primary opponents’ lack of comparable wealth is a disqualifier? How are you inspiring?

Lindstrom and Kingston aren’t the only GOP candidates. State Rep. Geoff Diehl, businessman Shiva Ayyadurai, and Allen Waters of Mashpee are also running. But these questions are for the two candidates formally jumping in this month.

It’s too early to tell if Lindstrom and Kingston will split the vote or split their differences with Massachusetts Republicans. Each will need 15 percent of the vote at next April’s state party convention to secure their respective names on the primary ballot. But already there is controversy and trouble among them. Kingston, it was reported by the Globe, has bizarrely urged Lindstrom to drop out of the race. Surely a brush fire Baker wants extinguished immediately.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer, former columnist with The Cape Cod Times and former banker. This column first appeared in New Boston Post. His work has also appeared in The Providence Journal as well as here, newenglanddiary.com.

James P. Freeman:Tuesdays are big opioid-overdose days on the Cape

The news this past Aug. 22, a Tuesday, seemed promising. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health released its quarterly report showing a 5 percent decline in opioid-related deaths in the first half of 2017 compared with the like period last year (978 deaths, as opposed to 1,031 deaths; January to June). The statistics led The Boston Globe to conclude this was “the strongest indication to date that the state’s overdose crisis might have started to abate.”

But the news was a tantalizing chimera. The Barnstable police already knew. August was cruel.

With overwhelming preponderance and without overlooking prejudice, the opioid crisis still rages unabated in Massachusetts. Especially on Cape Cod.

Figures provided by the Barnstable Police Department, the largest police force on the Cape, reveal a massive spike in opioid overdoses this past August compared with August 2016 (41 overdoses this year as opposed to 8 overdoses last year). Through the end of September, opioid-related overdoses in Barnstable, which at about 45,000 people is the largest town on the Cape, stood at 148. During the like period last year that number was 82.

Overdoses for the combined two months of August and September (61) were the highest for back-to-back months since January and February 2015 (51), when the Barnstable police first began keeping opioid-specific records. That’s when things seemed really bad. In many ways, now they’re worse.

Except for May, every month this year in Barnstable has seen an increase in overdoses compared to corresponding months in 2016. Already, there have been more overdoses in just nine months of 2017 than during all of 2016. And if current trends continue — nothing suggests that they won’t — this year will see more overdoses than in 2015, the year many thought was the high-water mark.

The death rate on the Cape isn’t encouraging, either. It is rising, not declining. Barnstable police report that 19 people have died due to overdoses through Oct. 10 of this year. In the like period, just nine people died through the end of October 2016. It is nearly certain that, beginning with respective Januarys, more lives will be lost by the end of October 2017 than were lost by October 2015 and October 2016, combined. This is progress in reverse.

Officer Eric W. Drifmeyer oversees the Research and Analysis Unit of the Barnstable Police Department. He is a busy man. Before 2015, the department, like many Massachusetts law-enforcement agencies, did not have adequate reporting mechanisms to track and maintain useful information relating to opioid-specific activity. In the past, Drifmeyer says, any data collected were categorized as generic “medical events.” But as the opioid crisis escalated — it is estimated that 85 percent of crimes on Cape Cod are opiate-related — the need for more accurate crime data increased, too.

So Drifmeyer and his colleagues built their own database.

Data-driven information provides police with intelligence. With superior intelligence trends become apparent — such as populations at risk in an opioid crisis. Here, that means young adults who are prone to abusing opioids. In Barnstable — an area of 76 square miles comprising seven villages of affluence and affliction — overdoses in 2017 disproportionately affect white males ages 20-29 and 30-39, far more than any other demographic group. Barnstable police statistics show that men are overdosing at nearly twice the rate of women. And for females, white women ages 20-29 and 30-39 show the highest levels of overdose in 2017. These have been trend lines for years.

A superior database of historical information doesn’t just reveal trends. Consistent trends become accurate predictors of criminal activity. Drifmeyer notes that a spike in overdoses correlates directly with an immediate surge in crimes, such as shoplifting and car and house break-ins. Accordingly, proceeds from illicit sales of ill-gotten goods finance the next purchase of heroin and other opioids on the street. And the cycle repeats itself. From this learning curve emerges better policing — devising effective strategies, dispatching efficacious resources, and thwarting criminal behavior.

Every day on Cape Cod, in a sad ritual, somewhere, someone is rolling up a sleeve, readying an arm for a taut elastic rubber tourniquet, anticipating the needle chill about to puncture a warm vein for perhaps the last sensationally euphoric high.

Tap. Tap. Tap …

Naloxone, the powerful opioid antidote, popularly known as Narcan, reverses the effects of overdose. Its widespread and immediate administration by first responders on those suspected of overdosing is probably the reason that the death rate has declined slightly this year in Massachusetts. Police in Barnstable have revived many people. Of the 148 officially designated overdoses this year, police have administered Narcan 46 times individually and another 25 times with assistance from a third party, such as a firefighter-emergency medical technician. In the short term Narcan saves lives. But Narcan solves nothing.

Stunningly, many addicts today have Narcan present while they are using, says Drifmeyer. Employing what one detective said was a “buddy system,” Narcan is administered by the corresponding partner in the event of overdose by the user. It is a bizarre insurance policy against a bad batch of drugs in this high-stakes risk/reward game; much heroin is now laced with the powerful additive fentanyl (itself a synthetic opiate), 50-100 times more powerful than morphine and 30-50 times more powerful than heroin itself.

Today, Barnstable police cruisers are stocked with two 4-milligram doses of Narcan. Not long ago it was 2-milligram doses. Those lower doses were not effective at neutralizing higher concentrations of fentanyl increasingly found in heroin.

First responders are also at risk from exposure to just small quantities of fentanyl. It is so dangerous, in fact, that police and paramedics can effectively “accidently overdose” if they come into contact with only a bit of the drug. Today, Barnstable police dog units now carry Narcan because service dogs sometimes accidentally overdose, too, by inhaling fentanyl into their nasal passages or absorbing in into their paws while working a case. This unimaginable collateral damage is the newest alarming phenomenon in what PresidentTrump in August rightly called a “national emergency.”

Last decade, the most covered story in The Cape Cod Times, the largest paper on the Cape, was the controversial off-shore wind farm proposed for Nantucket Sound known as “Cape Wind.” By the end of this decade, depressingly, the opioid matter will likely be the top story. Since 2000, nearly 400 people have died on the Cape and Islands due to some form of opioid overdose. With crashing regularity, stories appear on a near-daily basis, one falling into the other, like cascading dominoes.

Click. Click. Click …

In the last month, these stories received front-page treatment: Oct. 7, “Construction Workers Hard Hit by Opioid Addiction”; Oct. 4, “Study at McLean Hospital Reveals Marijuana’s Benefits in Lowering Opioid Usage”; Sept. 22, “Judge: Drug Dealing Merits Homicide-Level Bail”; Sept. 17, “Addiction Experts Warn of Detox Dangers”; and Sept. 12, “Drop-In Night New Option for Drug Users.”

Obituaries in the paper are sad narratives of dying youth. They are all too frequent. Last year, 82 people on the Cape and Islands died because of opioid overdose. (Barnstable County ranked third statewide for fatal overdose rates in 2015 and 2016.) And all too often these announcements contain no cause of death, wrongly stating the deceased died “peacefully” or “quietly.” One was named Arianna Sheedy. She was 23 and a mother of two when she fatally overdosed on Feb. 16, 2015, one of seven who died of similar causes on Cape Cod that month.

Sheedy was featured in the 2015 HBO film Heroin: Cape Cod, USA. The documentary portrays the day-to-day lives of eight young addicts. It is equally haunting and horrifying and must-viewing for anyone — everyone! — intent on understanding the mindset of people completely consumed emotionally, psychologically, and physically by this kind of addiction. (The film will be rebroadcast on HBO2 on Wednesday, Oct. 18.)

There are many memorable vignettes but one stands out. Opioid nirvana, one participant said, “felt like Christmas morning every time I shot up. Who wants to give that up?” Sheedy and another addict, Marissa, died before filming was finished. The film is dedicated to their memory.

Among the intriguing statistics in the Barnstable police database are 2017 overdoses by day-of-the-week. Surprisingly, Tuesdays rank second-highest, only slightly below Fridays. As Drifmeyer dryly concedes, heroin “is not a recreational drug,” so weekdays are just as active as weekends. (Heroin is a retail business; perhaps even big deliveries slow on Sundays.) Still, why Tuesdays figure so prominently is puzzling to police. But as time and statistics accumulate, it is likely that mystery will be solved by their unsung and noble work.

Most of the heroin on Cape Cod arrives from Fall River and New Bedford, transported along the I-195 corridor, what is considered a local Heroin Highway. Every day, anonymous lives, hopes and dreams travel that lonesome road. Until something desperately changes, they are slowly passing …

Gone. Gone. Gone.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer and former columnist with The Cape Cod Times. This piece first ran in the New Boston Post. Besides that outlet and newenglanddiary.com, his work has also appeared in The Providence Journal and nationalreview.com.

James P. Freeman: MTV pulls its young viewers into progressivism and degeneracy

In the 2011 book, I Want My MTV, John Taylor, bass player for Duran Duran, commenting on early video content said, “All this stuff like Culture Club was the result of an underground, progressive, liberal, London art school sensibility.”

By 1992, however, an unscripted soap opera (The Real World) and a character named Bill Clinton became programming staples, nodding to its future direction. Gifts to cultural regression later included Beavis and Butt-Head, Jackass and The Jersey Shore. About the last, Snooki impressed producers in 2008 by her candid -- celebrated? -- talk about sex and alcohol for a show about “Guidos and Guidettes." Her years of embarrassingly bad behavior (2009-2012) were rewarded by, among other things, a paid appearance ($32,000) to speak to students at Rutgers University in 2011, (where she advised students to study hard but party harder) and as a participant on Dancing With the Stars (which was announced on the selectively prim and proper Good Morning America) in 2013.

Rob Tannebaum, author of I Want My MTV, told National Public Radio’s, All Things Considered, on a whimsical trip about the golden years of the cable station, “MTV quickly realized and learned that narrative television, even reality TV, rated better than music videos."

For years its reality programming has glorified and valued moral relativism (watch the appallingly dreadful Teen Mom and Undressed). But now the company believes that it is a moral arbiter to correct all that ails our culturally sensitive society. A culture that has been largely led by progressives for over a half a century and of which MTV has been a big promoter for the last 36 years.

Conservatives constantly complain about universities being incubators of progressive preening and pedagogy (where “white shaming” is the newest rage). But it starts well before the first delicate snowflake lands on a college campus. It starts with MTV and it is time that conservatives start paying attention.

MTV is the greatest cultural influencer of young people today.

According to marketing blogger Brandon Gaille, MTV reaches 387 million people worldwide and is considered the no. 1 media brand globally. In 2015, he wrote that, “It is the one channel where people in the 12-34 age bracket continually tune in to catch up with what is coming next in pop culture, music, and fashion.” Furthermore, he added, the network “provides a variety of programming, ranging from politics to reality TV, and it is all targeted to the young adult demographic.”

Its reach of young people is staggering. Over 47 million people follow MTV on Facebook, three times as many as those who follow Fox News. One in three U.S. citizens falls into the 12-34 age demographic, accounting for over 90 million people.

MTV’s sway may be wider than currently understood too. Notwithstanding a steady decline in overall television ratings -- VMAs showed an 18 percent drop in viewership from 2013 to 2014; Adweek reported last year that the network lost half its 18-49 audience from 2011 to 2016 -- it makes a greater impact on ubiquitous social media. Which is difficult to measure.

For the average MTV viewer, Gaille observes, the largest annual expenditure, unsurprisingly, is on personal computers, tablets and smartphones. As of Gaille’s 2015 writing, ratings for computers and mobile devices were not reflected in Nielsen ratings, “which is where many of the 12-34 key demographic consume media content.” (Nielsen in 2017 received accreditation for such digital measurements.)

MTV’s president, Chris McCarthy, 42, is progressivism’s newest cultural and political warrior. He is also proof that the personal values of powerful cultural decision makers can be newsworthy and wildly, unduly influential. Last month he told The New York Times that the station is “about amplifying young people’s voices,” adding, “we shouldn’t be telling people how to feel.” But telling people how to feel and what to do, like the federal government, is exactly what MTV is doing. Subtly and not so subtly.

There is no pretense to objectivity with MTV News. Thirty years ago, when it first aired, it reported on the comings and goings of music stars; now it has descended into the progressive abyss. Its “Politics” section makes The New York Times’s op-ed pages look moderate. A gem from this past January asked, “Why Do American Conservatives Look So Different From the Rest of the World?” And a recent post from the “Movies” section contained this headline: “Matt Damon Explains How Suburbicon Shows the ‘Definition of White Privilege’ at Work.”

Ever since the first VMAs debuted in September of 1984, award winners received a trophy called a Moonman. No More. In politically correct 2017, McCarthy asks The Times, “Why should it be a man?” As only a progressive can describe a miniature silver statue, “It could be a man, it could be a woman, it could be transgender, it could be nonconformist.” It could be a conservative in disguise…

At this year’s VMAs, , no one, apparently, got McCarthy’s feelings and doings message.

Sadly, it is now taken for granted that elite entertainers use award ceremonies, however briefly, as a vehicle to express opinions and level grievances. No longer content to simply be recognized for questionable talent, today’s award winners (and special guests) are now social commentators and news broadcasters for young people. This year’s VMAs unrepentantly dissolved into a progressive political platform.

Pink told the story of her six-year-old daughter feeling unattractive because she believed she looked like a boy. As CNN reported, “The singer said she used it as a teachable moment to discuss androgynous artists who have found success, including herself.” The program also showcased the Rev. Robert Wright Lee IV, a descendent of Civil War Gen. Robert E. Lee. Nervously, he lamented, “We have made my ancestor an idol of white supremacy, racism and hate.” Citing a “moral duty” to speak out against “America’s original sin,” Lee called on “all of us with privilege and power to answer God’s call to confront racism and white supremacy head-on.” That statement implies there is a powerful sense of white privilege and channels white shaming.

Not to be out done by our ever-inclusive, multi-diverse cultural correctness, MTV, following grade-school catechism, chose to honor all six videos nominated in its -- seriously! -- “Best Fight Against the System” category. All artists received little Moon Persons for their so-called “groundbreaking” efforts.

The Technicolor irony is that MTV is the system.

The ratings results for this year’s VMAs are a compelling, if not revealing, story. Only 6.5 million brave souls watched the show -- linear viewing -- across 11 Viacom networks on traditional television (down from 10.3 million viewers in 2016). But as deadline.com reported, (“MTV Focuses on Social Successes”) the 2017 VMAs clocked 62.8 million video streams on Facebook. The 2015 show drew only 4.4 million streams.

Conservatives are largely to blame for allowing these cultural excesses to flourish and become mainstream, and for allowing them to go unanswered. Especially guilty are those running for political office under the pretentious slogan “fiscal conservative and social moderate.” On fiscal matters, they have not corrected any of the $20 trillion in national debt. And on social, hence, cultural matters, they have retreated and surrendered any sense of resistance.

Twenty-five years after Pat Buchanan’s much criticized speech, the moral and cultural cesspool has clearly been realized. MTV has eclipsed higher education as a new, larger, and more troubling progressive front in the ongoing culture war.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer and a former columnist with The Cape Cod Times. His work has also appeared in The Providence Journal, newenglanddiary.com and nationalreview.com. He formerly worked in the financial-services industry. This piece first appeared in the New Boston Post.

James P. Freeman: Department stores in fast descent as Amazon takes their business and destroys jobs

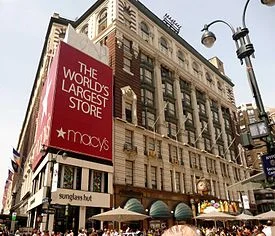

Macy's flagship store in Manhattan.

“Macy’s of today is like in soul and spirit to

Macy’s of yesterday; Macy’s of tomorrow…”

— Edward Hungerford, The Romance of a Great Store (1922)

If today is yesterday’s tomorrow, the Macy’s of 2017 would be unrecognizable to its founder, Rowland Hussey Macy. Except, perhaps, for the ubiquitous red star, the company’s logo, which was inked onto his forearm as a young sailor, while working on the whaling ship Emily Morgan, based out of New Bedford, Mass.. The star was inspired by the North Star, which, according to legend, guided him to port and an optimistic future. Today, the company — and, by extension, the traditional retailing industry — rocked by an exceptional gale, looks to the heavens for safe harbor and secure future. The turbulence, however, is a healthy sign of the creative destruction of capitalism. Accordingly, let traditional retail perish.

Last April, a New York Times expose, “Is American Retail at a Historic Tipping Point?,” revealed that 89,000 Americans have been laid off in general-merchandise stores since October 2016. “That is more than all of the people employed in the United States coal industry, which President Trump championed during the campaign as a prime example of the workers who have been left behind in the economic recovery.”

About one out of every 10 Americans works in retail. That’s nearly 16 million people (both online and in stores), confirms the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unsurprisingly, only 5 percent are represented by unions.

More than 300 retailers have filed for bankruptcy just in 2017. Among them: Gymboree (operating 1,300 stores), rue21 (1,200 stores), Payless ShoeSource (4,400 stores), The Limited (250 stores), and a century-old regional department store company, Gordmans Stores (106 stores, in 22 states). In the past year, Macy’s has announced it would close 100 stores (identifying 68 locations, eliminating 10,000 jobs). J.C. Penney will close 138 stores. Sears (which also owns Kmart) is shuttering 150 stores and said last March that the company has “substantial doubt” about its survival after 13 decades in business. Since 2010, Sears has lost $10.4 billion and has closed several hundred stores.

A report released this spring by Credit Suisse, the financial-services firm, estimates that 8,640 retail stores will close by year’s end and, more staggering, approximately one quarter of the nation’s 1,100 malls will close in the next five years.

“Modern-day retail is becoming unrecognizable from the glory era of the department store in the years after World War II,” notes the Times. “In that period, newly built highways shuttling people to and from the suburbs eventually gave rise to shopping malls — big, convenient, climate-controlled monuments to consumerism with lots of parking.” The glitz and glamour of shopping reminiscent of the Mad Men period is over. Instead, a wrenching, permanent restructuring is likely under way. As it should be.

What happened?

Shifting consumer shopping habits driven by, and probably, a result of, e-commerce. Stated simply: “market forces.” A concept understood by ordinary people. Alarmingly, though, highly compensated retail executives were slow in identifying these new dynamics. For which many big retailers are now desperately, but not adequately, adapting to these changes. They are failing.

Devoid of any romance, today’s retail is a hard scrabble of Sisyphean drudgery. Product comes in. Product goes out. Product comes back in … Repeat. Generic and dingy department stores are full of tired-looking mannequins and haggard-looking, underpaid sales associates pushing promotions and credit cards. But many stores are empty of customers.

America is called “overstored” — having too much retail space, which now totals about 7.3 square feet per capita. On a comparative basis, that is well above the 1.7 square feet per-capita in Japan and France, and the 1.3 square feet in the United Kingdom. Jonathan Berr of Moneywatch says: “Overstoring can be traced back to the 1990s when the likes of Walmart, Kohls, Gap, and Target were expanding rapidly and opening new divisions.” And then the Internet happened.

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw the evolution of a new business model. Those who embraced a so-called “brick and click” model (combining brick-and-mortar operations with online presence) were certain to survive, and those who executed it well would likely thrive for the foreseeable future. Many retailers were late to the party. When they did arrive, they never harmonized their physical space and cyberspace. Consequently, traditional retailers never kept pace with the value created by the likes of Amazon. The new disruptors perfected the model and, more importantly, created a better customer experience.

Between 2010 and 2014, e-commerce grew by an average of $30 billion annually. Now, e-commerce represents 8.5 percent of all retail sales, (trending straight upward since 2000) disproportionately affecting the big-box retailers that are anchor tenants in malls that, in turn, draw foot traffic from which other mall retailers ultimately benefit. ShopperTrak estimates that retail store foot traffic has plunged 57 percent between 2010 and 2015. And more stunning, Amazon is expected to surpass Macy’s this year to become the biggest apparel seller in the United States.

Macy’s, self-described as “America’s Department Store” — a brand celebrating ubiquity over uniqueness — is symbolic and symptomatic of retail’s quandary.

With its corporate sibling, Bloomingdale’s, the company is a constellation of complexities. Far from its meager beginnings as a single dry goods store in Haverhill, Mass. when it opened in 1851, it is now a cobbled-together conglomerate operating 700 stores in 45 states, employing 140,000 (of which 10 percent are unionized). Because of so many mergers and acquisitions, there is no unifying culture. It has 50 million proprietary charge accounts on record (nearly one in six Americans).

Macy's flagship store in Herald Square in Manhattan attracts 23 million visitors annually. Known as an “omnichannel retailer” (myriad ways of consumer engagement; i.e., store, Internet, mobile device), with sales over $25.7 billion, Macy’s is still profitable (earning $619 million last year). But it is in trouble.

In July 2015, Macy’s market capitalization (total value of its publicly traded shares) was more than $22 billion. It has plummeted to about $7 billion today. Constantly tweaking marketing and merchandising, the company nevertheless reported that net sales declined for the ninth straight quarter, in May. Saddled with $6.725 billion in debt and with fewer customers, over half its earnings are derived from its credit-card business. (Just three years ago, credit cards accounted for a quarter of its earnings.) Lead times for its lifeblood, the supply chain, are long and slow. Real estate holdings (estimated to be worth between $15 billion and $20 billion) are substantially more valuable than its business operations. Double-digit growth in online business is cannibalizing negative growth in store business.

Macy’s is ever-reliant upon the next generation of shoppers, but Millennials may not be that reliable; they defy consumption patterns that previous generations followed for years (less materialistic and more loyal to experiences than to physical brands). And Amazon’s new Prime Wardrobe might prove to be a death star, obliterating many red ones. Gloomy and overwhelmed, Macy’s reflects the industry at large.

This past January, Amazon announced it would create 100,000 jobs over the course of 18 months. Yet it is foolish to think that Amazon — which is much more efficient than traditional retailers — will absorb all the displaced workers.

As Rex Nutting, writing for MarketWatch, warns, what Amazon “won’t tell us is that every job created at Amazon destroys one or two or three others.” And what Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos “doesn’t want you to know is that Amazon is going to destroy more American jobs than China ever did.”

Even if the American consumer is the beneficiary of these disruptive but necessary market forces, sooner or later this economic issue will become a political issue.

Conservative commentator George Will raises a good question: “Why should manufacturing jobs lost to foreign competition be privileged by protectionist policies in ways that jobs lost to domestic competition are not?”

President Trump should, but probably won’t, answer a question that would help clarify the puzzling public policy he is now crafting (see his “major border tax” proposals). As the president will surely learn, economics — like health care — is complicated fare. And like most things involving Trump, it is personal.

During last year’s presidential campaign, Trump said Amazon has “a huge antitrust problem.” (An analysis found that 43 percent of all online retail sales in the United States went through Amazon in 2016.) Notably, Bezos owns The Washington Post, largely critical of the president. In late 2015, Trump called for a boycott of Macy’s after the company stopped selling Trump merchandise and severed ties with the presidential candidate because of comments he made about Mexicans earlier that year.

Then there is his daughter, Ivanka Trump. Despite her father’s call last January that “We will follow two simple rules — buy American and hire American,” she still owns an apparel company with much of its product line foreign-made. And with gilded irony, some is still sold at Macy’s.

With or without first family entanglements, markets will dictate those retailers it deems omnipresent and obsolescent.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer and former columnist with The Cape Cod Times. He formerly worked in financial services.

James P. Freeman: Past time to break up America's mega-banks before they cause another crash

JPMorgan Chase & Co. headquarters, in Manhattan.

As Americans were lounging comfortably over the 4th of July holiday, some were surely feeling a sense of new-found serenity. Not because they were full of burgers, barkers and beer. On the contrary, they were digesting the news that 34 of the nation’s largest banks, for the first time since the financial crisis began a decade ago, all passed the Federal Reserve’s annual “stress tests,” which, according to The Wall Street Journal, “could bolster the industry’s case for cutting back regulation.” But hold the match before lighting leftover fireworks in celebration. Break up the banks first.

Remarkably, the five largest banks today — JPMorgan Chase & Co. Bank of America, Citibank, Wells Fargo Bank, US Bank — now control about 45 percent of the financial industry’s total assets or roughly $7.3 trillion in assets. To put that number in perspective, the size of the U.S. economy is roughly $18 billion.

Twenty-five years ago, the five largest banks owned just 10 percent of all financial assets. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s statistics reveal that in 1992 there were 11,463 commercial banks and 2,390 savings and loans. By March of 2017, that number had dwindled to 5,060 commercial banks and just 796 savings institutions. The assets held by the five largest banks in 2007 – $4.6 trillion – increased by more than 150 percent over the past decade, when they held 35 percent of industry assets.

The sharp rise in the concentration of these assets (a measure of size and wealth) has real economic, political and social ramifications. As oxfamamerica.org fears, “These massive banks use their wealth to wield significant political and economic power in the U.S., in the countries where they operate, and in the international arena.” Finance today, author Rana Foroohar reasons in Makers and Takers, “holds a disproportionate amount of power in sheer economic terms.” (It takes about 25 percent of all corporate profits while creating only 4 percent of all jobs.)

Moreover, writing five years ago in The Washington Post, just as the banking system was being recalibrated and reregulated, U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee, recognized then (and still true today) what the federal government should recognize now: “Even at the best-managed firms, there are dangerous consequences of large, complex institutions undertaking large, complex activities. These companies are simply too big to manage, and they’re still too big to fail.” While Brown is correct in citing “Too Big To Fail” (a warped public policy), he is right to emphasize (as many more public officials should) that these firms are simply too big to manage and maintain.

JPMorgan Chase is a financial colossus. In January 2017, it reported assets of $2.5 trillion that generated $99 billion in revenue and earned $24.7 billion in profit. It is the largest U.S.-domiciled bank and the sixth largest bank in the world. Today, it alone holds over 12 percent of the industry’s total assets, a greater share than the five biggest banks put together in 1992. Its global workforce of 240,000 operates in 60 countries. From 2009 to 2015, the bank paid $38 billion in fines and settlements (involving among them the Bernie Madoff and London Whale scandals), mere rounding errors in its ethics and financials.

Jamie Dimon is the company's chairman and chief executive officer, perhaps the second most difficult job in the country, only after the presidency of the United States. To say that he “manages” the firm would be an overstatement. More accurately, he “presides.” Dimon was named CEO in 2005 (when assets were only $1.2 trillion) and is widely given credit for adroitly navigating the financial turmoil of 2008-2009. In 2015, he made $27 million and said that banks were “under assault” by regulators. He keeps two lists in his breast pocket: what he owes people; what people owe him.

Now 61, he is the subject of much discussion centering on speculation about who his successor will be. In an interview for Bloomberg Television last September, Dimon said he would leave “when the right person is ready.” But who is ever “ready” and able to run a $2.5 trillion company? No one competently.

Wells Fargo ($2 trillion in assets with 8,500 locations) was thought to be among the best managed banks before, during, and after the crisis until it was revealed last year that it had fired 5,300 employees and clawed back $180 million in compensation, due to the unauthorized opening of 2 million customer accounts. A flawed “decentralized structure” and perverse sales culture were to blame for illicit activities that occurred over a decade.

Fortune Magazine in March 2007, with sterling irony, named Lehman Brothers (No. 1) and Bear Stearns (No. 2), respectively, as the most admired companies in the securities industry. By the end of 2008 Lehman Brothers had filed for bankruptcy (the largest in U.S. history, $692 billion) and Bear Stearns had been sold in a fire sale by fiat to JPMorgan Chase.

Big banks are driven by avarice and algorithms (complicated code-directing computers to effect financial transactions by the millisecond), not altruism. Lending is secondary to speculating. Complexity has replaced familiarity. Vaults hold more data than gold. And traders can destroy banks faster than boards of directors. On any given business day, no executive or regulator can be certain of the health of these institutions.

This is the new Wall Street alchemy.

The first public signs of distress in the financial system before the Crash of 2008 appeared 10 years ago, when a July 2007 letter to the firm’s investors disclosed that two obscure hedge funds managed by Bear Stearns had collapsed. The long fuse had been lit. The Great Recession was triggered. And the torch paper was provided in the form of legislation.

The Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 (known as Gramm-Leach-Bliley) neutered the Banking Act of 1933 (known as Glass-Steagall), which separated the riskier elements of investment banking from the more conservative aspects of commercial banking. The 1999 law spurred a new model of financial supermarkets (banking, investments and insurance under one company). It also unwittingly fostered a new risk-taking model: Losses could be socialized (depositors, shareholders, taxpayers) while profits could be privatized (executive compensation). Exotic financial instruments and ineffective regulatory oversight fueled the meltdown.

Today’s big banks largely resemble Zuzu’s petals in the film It’s a Wonderful Life, seemingly mended but not made better. During the Crash/Panic of 2008, the federal government engineered the financial equivalent of pasting damaged rose petals in a desperate attempt to prevent the total collapse of the banking sector. It effectively merged the unwieldy likes of Merrill Lynch with Bank of America, Bear Stearns with JP Morgan and Wachovia with Wells Fargo.

In the wake of the crisis (which ultimately required $1.59 trillion in government bailouts and another $12 trillion in guarantees and loans), The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 became law. It sought to make the financial system safer and fairer than it had been, to reduce the risk of financial crises, to protect the economy from this kind of devastating costs of risky behavior, and to provide a process for the orderly disposition of failing firms. But after a staggering 848 pages and 8,843 new rules and regulations, Dodd-Frank does nothing to reduce the size of, and hence the systemic risk posed by, the biggest banks.

“We may have gotten past the crisis of 2008,” Foroohar concludes in her book, but, disturbingly, “we have not fixed our financial system.” Bankers still “exert immense soft power” via the revolving door between Washington and Wall Street. And today’s top government regulators are littered with former banking executives, who are “disinclined to police the industry.”

The idea of overhauling big banks, however, is attracting some surprising converts.

In May, President Trump acknowledged that he was “looking at” breaking up the big banks. And the principal architects and former co-heads of the first financial supermarket — Citigroup — have had an epiphany of sorts. In 2015, ex-Citicorp CEO John Reed wrote in the Financial Times that “the universal banking model is inherently unstable and unworkable. No amount of restructuring, management change or regulation is ever likely to change that.” And in 2012, Sandy Weill, another former Citicorp CEO, called for a return to Glass-Steagall.

Dodd-Frank mandates that the Federal Reserve conduct annual stress tests on financial institutions with assets over $50 billion. This year’s test on 34 banks relied upon enhanced computer modeling to assess how those banks would perform under “adverse and severely adverse” economic conditions. But such modeling is an unreliable predictor of reality. As JPMorgan Chase knows well.

In May 2012, The New York Times provided insights into massive trading losses at JP Morgan Chase. The bank had little idea that the losses were brewing. It entrusted computer modeling pioneered by its bankers in the 1990s to identify and measure potential losses. But the bank tripped up its measurements. It deployed a new model that underestimated losses; when it redeployed the old model, it nearly doubled the losses. As The Times chillingly remembers, such computer programs “proved useless during the financial crisis.”

James P. Freeman, a former banker, is a New England-based writer, former columnist with The Cape Cod Times and frequent contributor to New England Diary. This piece first ran in The New Boston Post.

James P. Freeman: RINO Baker drifts left along with the anti-Trump Bay State

For many Massachusetts Republicans, Gov. Charlie Baker’s administration is the advancement of a dishonest marketing campaign: Baker and Switch. (Run as a Republican, cozy up to Democrats, disown the Republican Party.) Rejected Republicans, perhaps feeling duped from day one, should take note. Baker’s dispiriting drift to the left may just prove to be a stroke of genius for re-election in 2018. It’s a plan without Republicans — the abandoned, fatherless children of Massachusetts politics.

The plan was actually hatched well before President Trump skunked The Party of Ronald Reagan. As a Baker senior adviser, Tim Buckley, told The Atlantic, the governor’s campaign in 2014 focused from the beginning on “showing he could say ‘screw you’ to the Republican Party.” Those words have proven to be prophetic and strategic.

The cold calculus of political reality, as Baker’s team knows, does not favor any Republican in the Commonwealth, let alone an incumbent Republican governor. As of February 2017, there were 4,486,849 registered voters in Massachusetts, with just 479,237 registered Republicans (11 percent of the total). Unenrolled voters numbered 2,424,979 (54 percent) while registered Democrats numbered 1,526,870 (34 percent).

Since the 2014 election, unenrolled voters have increased by 133,824, while Republican voters have increased by only 9,973. Increased unenrolled voter registration is trending upwards, and may accelerate, as Trumpism (a governing style resembling the Coney Island Cyclone) roars through the land.

Even though Baker beat Martha Coakley by just 40,165 votes in 2014, the election was a blue lagoon of civility.

Next year’s election, by comparison, will be a dark pool of uncertainty but will certainly feature a rabid anti-Trump sentiment and, by extension and association, Republican defensive posturing. And in the Commonwealth — what fun! — the proselytizing progressive Sen. Elizabeth Warren will also be on the ballot. Republicans will be the expendables. Something the governor, understandably, wishes to defy for himself.

Baker is an elusive electoral enigma.

He is a social liberal and a fiscal conservative who has melted the cryogenically frozen corpse of {Nelson} Rockefeller Republicanism into new life. He enjoys a 75 percent approval rating in a state where Democrats control 79 percent of the House and 83 percent of the Senate, and Hillary Clinton overwhelmingly won last November (61 percent to Trump’s 33 percent). He maintains a working relationship with House Speaker Robert DeLeo (where massive power resides), whose understated temperament is like his own. And, he operates without a political base, given the minuscule minority status of his party.

Seemingly harboring zero national ambitions, Baker would be the first Republican Massachusetts governor to be re-elected since William Weld, in 1994 (who resigned in 1997 after being nominated as U.S. ambassador to Mexico – a nomination killed by right-wing North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms).

Baker’s survival instincts are validated by this paradoxical fact: Even as prospective Democratic gubernatorial candidates (Setti Warren, Jay Gonzalez and Bob Massie) rightly cite his lack of grand vision for Massachusetts, many Democrats on Beacon Hill quietly concede that state government is functioning better under the bipartisan executive leadership of Baker than it did under his predecessor, Democrat Deval Patrick (who, with contempt for hands-on management, always spoke with a grand vision).

As The Boston Globe noted the other week, “State Democrats turn attention to Trump, not Baker, at convention.”

Still, for conservatives (a fringe of the fringe in the Commonwealth) hoping there might be some application of conservative ideas in this playground of progressivism, there is deep dissatisfaction with the governor. His risky political plan (popularity is perishable; a large unenrolled bloc can shift allegiance quickly) is, some believe, at the expense of foundational principles.

Howie Carr recently wrote in the Boston Herald: “As his first term in the Corner Office {of the State House} continues, it seems that the Republican-in-Name-Only (RINO) governor finds himself more and more ‘disappointed,’ not just with his party affiliation, but also with the drift of public affairs in general.”

That might explain Baker’s puzzling appointment last week of Rosalin Acosta, a Lowell bank executive, as his labor secretary. Acosta (a progressive activist and anti-Trump enthusiast) and her husband this year founded Indivisible Northern Essex, a liberal advocacy group that began supporting progressive candidates around the country. Should a progressive run against Baker, whom would Acosta vote for?

James P. Freeman, an occasional contributor to New England Diary, is a New England-based essayist, former Cape Cod Times columnist and former financial-services executive. This piece first ran in The New Boston Post.

James P. Freeman: Boston shows that Charlie Baker was right about charter schools

Plaque on School Street in Boston marking the first site of the Boston Latin School, founded in 1635 as the first public school in what would become the United States.

Boston's charter schools have received a record number of applications. This welcome development should prompt Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, who rightly and robustly supports charter schools, to renew efforts to reconsider expansion of these schools.

As reported in The Boston Globe, 16 charter schools in Boston “collectively received 35,000 applications for about 2,100 available seats,” according to the Massachusetts Charter Public School Association. Those same schools received 13,000 applications in the previous period. It is believed that a new online application system contributed to this year’s spike, making it easier for applicants to apply to multiple schools.

It is yet unclear if the number of applicants increased. Unquestionably, though, demand far outweighs supply; the odds of getting into one of these schools this fall have risen to 16 to one. Previously, there were three or four applicants per seat, The Globe notes, citing a Massachusetts Institute of Technology study.

Such a surge in applications may be surprising since a ballot measure in Massachusetts last fall seeking to expand the number of charter schools failed overwhelmingly, by a margin of 38 percent to 62 percent. Baker supported the measure.

“Opponents,” wrote wbur.com last November, “apparently swayed voters with their arguments that charter schools do not serve the neediest students, drain money from district schools, and could have proved ‘apocalyptic’ for city budgets and led to less state oversight of how charters are run.” (Under a reimbursement formula, the state pays school districts 100 percent of per pupil revenue lost to charters in the first year and 25 percent for the next five years.

In the same article, WBUR quoted Boston City Councilor Tito Jackson (now a mayoral candidate) as saying: “We need to have a communal mentality -- one where we elevate all of our young people.” And Jackson was “calling on state lawmakers to fully fund education -- and focus on building up schools in areas like Boston.”

Describing himself as a “longtime supporter” of Boston’s charter schools, in an opinion piece that appeared in The Globe before the ballot measure vote, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh (now running as an incumbent for mayor) nevertheless also opposed the ballot question. The “reckless growth” of more charter schools, he feared, “would change our charter culture and greatly increase the likelihood of school failures that hurt kids and discredit the reform movement.” And he added, bizarrely, that charter expansion would have been “fundamentally hostile to the progress of school improvement, the financial health of municipalities, and the principle of local control.”

Last January, in another editorial for The Globe, Walsh called for a 10-year, $1 billion investment plan to build “beautiful, innovative new buildings,” and to presumably renovate Boston’s existing 127 schools. The initiative, part of BuildBPS, is “an incredible opportunity,” he said. He ruefully asserts that “generations of struggle for equity in urban schools have left trust gaps.”

Both Jackson’s and Walsh’s statements -- along with those who oppose increasing the number of charter schools -- reflect today’s progressive orthodoxy and expose the weakness of today’s progressive impulses. For progressivism demands greater access to everything -- healthcare, contraception, happiness -- but not greater access to better education, which charter schools provide. And the progressive state -- harking back to the days of classic liberalism -- believes that an endless stream of monetary inputs (“equity”) results in higher cognitive outputs for public school students, who are threatened by additional charter schools.

What do progressives tell those students whose names this week were not be selected in the lottery that determines enrollment? That Boston Public Schools are a better alternative to charter schools?

Charter Schools, independent public schools that operate under five-year charters granted by Massachusetts’s Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, were first authorized by the Education Reform Act of 1993. The first 15 schools opened during the 1995-1996 school year, serving 2,500 students. In 2000 and 2010, legislation was passed to add more schools, to satisfy demand. Today, 78 charter schools educate over 42,000 students annually (representing 4.2 percent of all PK-12 public school population), with nearly 30,000 on waiting lists; Boston is home to 22 charter schools while another 38 are in spread among urban areas outside of Boston.

According to statistics released by the Massachusetts Department of Education, they are remarkably diverse. For the 2016-2017 period, students deemed economically disadvantaged constitute 35.5 percent of charter school population (compared with 27.4 percent for the overall state school population). African-Americans comprise 29.9 percent of charter school population (8.9 percent for the state), while Hispanics are 31.7 percent of charter population (19.4 percent for the state).

And charter schools are remarkably effective. “Charter School Performance in Massachusetts,” a comprehensive study at Stanford University, concluded in 2013 that, “Compared to the educational gains that charter students would have had in TPS [traditional public schools], the analysis shows on average that students in Boston charter schools have significantly larger gains in both reading and mathematics.”

The Baker administration refutes charges that charter schools siphon funds from public schools, to their detriment. In an email communication, Brendon Moss, Baker’s deputy communications director, said that the administration “will continue to make investments in our public schools at historic levels.” Indeed, Moss wrote, funding local schools under the current administration is at an all-time high, now $4.68 billion. The proposed fiscal 2018 budget includes increasing support by more than $90 million, twice the amount required under state law.

Baker understands fully the benefits provided by charter schools and he was right to support their expansion last year. Armed with a record number of applications this year, he should now demand that the legislature correct the mistake clearly made by misguided voters by approving charter school expansion – action that conservatives should robustly support, too.

James P. Freeman, an occasional contributor to New England Diary, is a New England-based writer and former columnist with The Cape Cod Times.

James P. Freeman: With the Trump vaudeville show, it's back to 'Laugh-In'

John Wayne and Tiny Tim helped Laugh-In celebrate its 100th episode in 1971. Co-host Dan Rowan yucks it up in his tuxedo.

“… let’s go to the party!”

— Dan Rowan

Without a trace of transgression, Time recently described Donald Trump and his nascent administration as “a vaudeville presidency.” The other week, with absurd appearances by several of the president’s principal architects, the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) unwittingly staged this politically charged vaudeville act, replete with comedy, contortion, and commotion that, at times, resembled the television program Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In that ran in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

“Groovy!”

Hosted by comedians Dan Rowan and Dick Martin, the unique variety show was, says tv.com, “a fast-moving barrage of jokes, one-liners, running skits, musical numbers as well as making fun of social and political issues” of the period. And so was, CPAC 2017.

Writing for The New York Times Magazine in 1968, Joan Barthel observed that “whatever else it is — and at one time or another Laugh-In is hilarious, brash, flat, peppery, irreverent, satirical, repetitious, risqué, topical and in borderline taste — it is primarily and always fast, fast, fast! And in this it is contemporary. It’s attuned to the times. It’s hectic, electric …”

And so is the Trump administration, which, in its first month has proven to be a series of recurring, improvisational sketches, careening with disorder. Hence, the surreal Laugh-In connection.

“You bet your sweet bippy!”

In the television program, “guests” at the “Cocktail Party” would mill around with drinks in hand or dance to music that would suddenly halt when a party-goer would face the camera to deliver a one-liner or a quick joke. (Today’s party stops and starts again after President Trump transmits on Twitter his version of one-liners. (Remember the infamous tweet about the “so-called judge”?)

CPAC was, without a hint of hysteria, hijacked by a few of its guests vicariously reprising several popular segments of Laugh-In: “Mod, Mod World,” (Russian sabotage?); “Laugh-in Looks at the News” (fake news?); and the “Joke Wall” (the great Wall of Mexico?). With life imitating art, these cameo appearances made this year’s CPAC disturbingly memorable. And laughable.

Kellyanne Conway, counselor to the president, a few weeks ago on Meet the Press said that the White House press secretary used “alternative facts.” (Of which Rolling Stone rightly said, “the Trump presidency had its first laugh line.”) Telling attendees on Feb.23 in anticipation of Trump’s appearance the next day of the conference — stop the music! — “Well, I think by tomorrow this will be TPAC.”

But what was lost among the intermittent laughter was this stunning punchline: “Every great movement,” Conway said, “ends up being a little bit sclerotic and dusty after a time.” That line was directed at Reagan conservatives. Just as Laugh-In had obliterated conventional variety show boundaries, Trump World is eschewing traditional conservatism, simultaneously ransacking it and redefining it. Even as Conway formally announces the end of the Reagan Revolution, President Trump cleverly says his victory was a “win for conservative values.”

“Verrrry interesting!”

Apparently, Vice President Mike Pence was never let in on the punchline. After finishing his introductory remarks to CPAC with the jab, “all kidding aside,” Pence delivered this bizarre, if not ridiculous comparison: “From the outset, our president [Trump] reminded me of somebody else. A man who inspired me to actually join the cause of conservatism nearly 40 years ago. President Ronald Reagan.” Later, Pence quoted Scripture. Stop the music, again!

And then there was the question-and-answer session with the dynamic duo, Steve Bannon, White House chief strategist, and Reince Priebus, White House chief of staff. Trying to convey a patina of unity and order to this “fine-tuned machine,” Priebus said, “the truth of the matter is … President Trump brought together the party and the conservative movement.” And Priebus also compared Trump to Reagan saying the former also sought “peace through strength.”

Gannon (who led the crusading “alt-right movement” while at Breitbart, used to host his own counterprogramming conference to CPAC, called the “Uninvited”), straight faced, said, “The reason why Reince and I are good partners is that we can disagree.” Hilarious.

Laugh-In fashioned its aesthetic from the counterculture of the 1960s (“sit-ins,” “love-ins,” and “teach-ins”), reasons britannica.com. The show “tapped into the zeitgeist in a way no other show had, appealing to both flower children and middle-class Americans.” And Bannon, a counterculture conservative, likewise believes that “the power of this movement” will appeal to a broad spectrum of people too. Or will it?

One board member of the American Conservative Union (CPAC’s host) told The Daily Beast that, “‘The craziest elements of the [party] have managed to get every single thing they wanted over the past year … This is the shape our movement is in today.’”

“And that’s the truth!”

But first, a few words from our president, who openly mocked CPAC in his monologue-cum-speech Feb. 24 by declaring, “You finally have a president.” (Read President Reagan’s elegant 1981 CPAC speech, and his 1987 CPAC speech in which he imagined the future of conservative values; “a vision that works.”) Trump in his stand-up said, “We’re going to put the regulation industry out of work and out of business. And, by the way, I want regulation.” On his Cabinet: “I assume we’re setting records for that. That’s the only thing good about it, is we’re setting records. I love setting records.”

Recalling his first CPAC speech years before, with “very little notes, and even less preparation,” Trump quipped, “So, when you have practically no notes and no preparation, and you leave and everybody was thrilled, I said, ‘I think I like this business’.”

During the 1968 presidential campaign, candidate Richard Nixon taped a six second clip for “Laugh-In,” reprising one of its signature gag lines. Nixon won the election and Dick Martin jokingly confessed, “A lot of people have accused us.” After CPAC 2017, Reagan conservatives are the butt of the joke and target of that gag line:

“Sock it to me!”

James P. Freeman, an occasional contributor to New England Diary, is a writer and financial-services professional. He’s a former columnist for The Cape Cod Times. This piece first ran in the New Boston Post.

James P. Freeman: Now it's U2 vs. the Trump regime

Suit and tie comes up to me

His face red

Like a rose on a thorn bush

Like all the colours of a royal flush

And he’s peeling off those dollar bills

— “Bullet the Blue Sky,” 1987

U2’s angry, angst-driven anthem was meant to be a stinging political commentary on President Ronald Reagan’s ‘80s foreign policy, and the band’s seminal work, The Joshua Tree, was, by extension, an explorative essay about Americana, with Nevada’s desert plain serving as its cinematic lyrical leitmotif.

But today, still infatuated with America as an idea, U2 has substituted Donald Trump for Ronald Reagan, and the inspiration for the band’s newly announced tour, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the album, is really an elaborate ruse of anti-Trumpism, not a trip through the wires of celebratory nostalgia.

Fans should be prepared.

The Joshua Tree Tour 2017 (stopping in Greater Boston at Gillette Stadium on June 25) seems steeped in sentimentalism — with the band even having re-created a photo based upon the iconic album cover — given the original recording’s massive popularity and youthful idealism. But guitarist The Edge, in a recent Rolling Stone interview, provides fair warning and the reasoning behind this surprise tour: “The election [happened] and suddenly the world changed … The Trump election. It’s like a pendulum has suddenly just taken a huge swing in the other direction.”

Meaning, evidently, the wrong direction.

He further explained that “things have kind of come full circle, if you want. That record was written in the mid-‘80s, during the Reagan-Thatcher era of British and U.S. politics. It was a period when there was a lot of unrest. Thatcher was in the throes of trying to put down the miners’ strike; there was all kinds of shenanigans going on in Central America. It feels like we’re right back there in a way.”

And The Edge added that while this tour is “not really about nostalgia,” the songs “have a new meaning and a new resonance today that they didn’t have three years ago, four years ago.” That was under President Obama’s America of “safe-spaces” and universal health care. (The band played at a pre-inaugural concert in Washington, D.C., eight years ago, heralding his election.) Trump’s America, by contrast, is now a dangerous netherworld, as U2 sees it.

Two U2 shows in 2016 offer a kinetic prelude to shows coming this spring.

Last fall, before the election, performances at the iHeartRadio Music Festival and Dreamforce, in Las Vegas and San Francisco, respectively, were infused with vitriolic rants about Trump and the kind of degenerated America one should expect under his leadership.

During the song “Desire” at the iHeart show, with a video backdrop of Trump speaking, Bono asks those in attendance, “Are you ready to gamble the American Dream?” And if they were to vote for Trump they would, he admonished, lose “everything.”

James P. Freeman, an occasional contributor, is a writer and in financial services. This piece first ran in The New Boston Post.

James P. Freeman: Friedman's partly conservative look at adapting to accelerating change

Gentle reader, if the feverish pace of change in technology, globalization and climate change both fascinates and frightens you, read Thomas Friedman’s new book, Thank You for Being Late. His forensic examination and farsighted explanation of the acceleration of everything is an exercise in expeditionary learning and his prescription for adapting to this new world disorder should also appeal to conservatives.

Friedman, a New York Times columnist, is perceived to be as progressive as the paper he writes for. But that assessment doesn’t apply here. As he described it last year, he belongs to the party of “nonpartisan extremism” and his political alignment is “to the far left and the far right at the same time.”

Thank You for Being Late (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), currently ranks number 10 on the New York Times Combined Print and E-Book Nonfiction List and, published last fall, essentially is an epilogue to Alvin Toffler’s 1970 best-seller sensation, Future Shock (a book about feeling overwhelmed by change). Toffler’s assessment 47 years ago, was, basically, he wrote, “first approximations of the new realities.” So is Friedman’s for a world dominated by cyberspace.

The central argument of Friedman’s book is that technology (due to “Moore’s Law” — whereby computing power has been doubling every two years for the last 50 years), globalization (the “Market”) and climate change (“Mother Nature”) have all collided and now constitute the “age of acceleration.” These three accelerations “are impacting one another” and, at the same time, are “transforming almost every aspect of modern life.”

Friedman believes that the collision occurred roughly 20 years ago, 2007, with technological advancements in computing power (processing chips, software, storage chips, networking, and sensors) that formed a new platform. This platform “suffused a new set of capabilities to connect, collaborate and create throughout every aspect of life, commerce, and government.” These capabilities are smarter, faster, smaller, cheaper and more efficient. It is not coincidental, therefore, that that year saw the advent of the first iPhone, symbolic of this massive transformation.

The challenge posed by these exponential rates of change is our ability to absorb and adapt to them. “Many of us,” Friedman writes, “cannot keep pace anymore.” Eric Teller, head of Google’s X research and development lab, said, “[T]hat is causing us cultural angst.” And Teller warns that “our societal structures are failing to keep pace with the rate of change.”

Our fragile customs, traditions and mores are certainly being pressured in this all-digital, frenetic — if not homogenized — globalized environment. But Friedman is concerned that government itself has not kept up. The process of government — its lawmaking and structural components — should live in parallel with, and not be an impediment to, this age of accelerating change, he advises.

Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, a sort of conservative futurist, nearly a decade ago understood that government is not forward-thinking. In his book Winning the Future, he observed that “We live in a world defined by the speed, convenience, and efficiency of the 21st century, but with a government bureaucracy invented in the 19th century.”

This may partially explain the phenomenon of the presidency of Donald Trump and many Americans’ presumed desire to radically reform government. Trump may have tapped into the belief that today’s government is not only not operationally progressive but too philosophically progressive — that it is out of sync both with technological advances and with the will of the people.

But what will attract cautious conservatives who wish to retain American ideals within a constitutional republic in an era of trans-global bits and bytes that have no allegiance to American values? They face this while addressing this troubling fact, in Friedman’s words : “That we are creating vast new ungoverned spaces — free from rules, laws, and the FBI, let alone God — is indisputable’’.

Amidst the columnist’s 461 pages of analytics and anecdotes he understands that “geo-politics has to be reimagined in the age of accelerations, just like everything else.” He also realizes that we must “reimagine our domestic politics too.” Much of his list of 18 ideas should appeal to conservatives (which includes support for free-trade agreements, tightening border security, reforming bankruptcy laws and review of the Dodd-Frank financial regulations), despite his constant clamoring for immediate action on climate disruption. (In the 1970s, some in the news media warned of a coming ice age.)

Conservatives should also be elated with this novel nugget: “Today we need to reverse the centralization of power that we’ve seen over the past century in favor of decentralization. The national government has grown so big bureaucratically that it is way too slow to keep up with change in the pace of change.” Today, a centralized government is inefficient and out of step with the maddening drive towards efficiency and push for better performance.

Still, Friedman is bullish on the future. He is indeed optimistic that a better world will be made by, and we can adapt to, these accelerations. He sees local government starting to embrace these concepts.

Thank You for Being Late does not delve into the psychological ramifications about the effects of such rapid change on individuals and societies that Future Shock does; nor does it capture the sense of dislocation being experienced today. But it is just as compelling.

And there is exquisite irony in the timing of this new effort. Toffler died last year just months prior to the publication of Friedman’s captivating book. He nonetheless would have agreed with Friedman’s conclusion about these new realities. “I hope that it is clear by now that every day going forward we’re going to be asked to dance in a hurricane.”

James P. Freeman, an occasional contributor, is a writer who also works in financial services. This piece first ran in The New Boston Post.

James P. Freeman: Schilling could destroy the Mass. GOP

Tracing the “psychologies” and “pathologies” of this season’s presidential election in her new book, The Year of Voting Dangerously, New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd writes that the “fury” of the 2016 electorate is spawning a number of “wildly improbable candidates [for down ballot races] in both parties.” Here in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, one such improbable candidate just announced his intention to seek public office.

Curt Schilling, the former Red Sox pitcher and an avid Trump supporter, has announced he plans to challenge U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren in 2018.

What has Schilling been up to lately? Since his Red Sox days, Schilling has become – wait for it — an entrepreneur and entertainer. His disastrous foray into business, the doomed 38 Studios, is but one piece of fodder for Warren to feast upon. Purportedly a limited government and small business conservative, Schilling was lured to Rhode Island by a $75 million taxpayer-backed loan guarantee to launch a video-game company. It went bankrupt in 2012 and four years later is still scandal plagued. His insincere and insipid explanation of the matter in The Providence Journal last week is reminiscent of Trump’s explanations of his sexual shenanigans: Deny it and blame another party.

Like the Republican presidential nominee, Schilling has taken to Facebook and Twitter and blogging as a means of distributing his often rambling and incoherent thoughts. But this gem from an April 19 posting can be taken earnestly: “I’m loud, I talk too much, I think I know more than I do, those and a billion other issues I know I have.”

This past April, Schilling was fired from ESPN as a baseball analyst for a meme he posted on Facebook “that appeared to mock transgender people,” noted The Atlantic. Before this incident, in August of 2015 he was suspended by ESPN for posting an anti-Muslim meme.

Last month Schilling debuted a new radio program. Describing him as an “outspoken conservative,” The Boston Globe underscored that he “solidified the show’s right-leaning reputation” when he interviewed commentator Ann Coulter. And the hits keep on coming… It has been announced that Schilling is joining Breitbart with an online radio show, giving him national exposure. As nymag.com posted: “‘He got kicked off ESPN for his conservative views. He’s a really talented broadcaster,’ Breitbart editor in chief Alex Marlow said.”

But Mass. Republicans beware. What Trump has done to national politics — reducing the once respectable national Republican Party to rubble — his Massachusetts Mini-Me just may do to the state GOP.

Just as the state party has regained its respectability with the 2014 election of Gov. Charlie Baker, a Schilling candidacy would mark its sure death-knell in 2018. State Republican leaders should be mindful that Schilling would appear on the same 2018 ballot as Baker, should the governor run for reelection.