David Warsh: Understanding Russia's fascination with Vladimir Putin

The friendly -- or cold?-- face of the Russian president.

Chicago Tribune editor Jack Fuller used to speak of the mainstream news business as being among the “truth disciplines,” its aim being “at most a provisional kind of truth, the best that can be said quickly.” Science was older, slower, more firmly grounded. There were many related fields. As a newsman himself, Fuller didn’t spend over much time on the nature of truth, but most people know what he meant.

He was concerned with matters on which all those who took pains to inform themselves could agree. These were names, addresses, ages, places, details, to start; then assertions of all sorts, carefully attributed, not piled on willy-nilly but carefully connected in logical chains, accumulating in hopes of producing the goal, impossible in all but the simplest matters (was he alive or dead?), of consensus.

An interesting example of just how unsatisfying routine news can be could be heard last week in an imaginative and ambitious venture undertaken by National Public Radio, a member-supported media network enabled by the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. NPR’s’s Morning Edition host David Greene traveled to Moscow to report live on Friday, June 9, and, as scheduled, Monday, June 12 – at the very moment that testimony of former FBI Director James Comey was dominating the news in Washington and New York. His dispatches were supplemented by reports from NPR national security correspondent Mary Louise Kelly and Moscow correspondent Lucian Kim.

In one segment, Greene interviewed Russia Today editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan. Government-funded RT insists that it is a global news network much like the BBC or France 24 or Al Jazeera, offering news and opinion from a distinctive Russian point of view in both Russian and English. Many Western governments (and news organizations) regard RT as “the slickly produced heart of a broad, often covert disinformation campaign designed to sow doubt about democratic institutions and destabilize the West,” as Steven Erlanger recently put it in The New York Times.

Simonyan, 37, is well suited to her task. She spent a year in high school in Bristol, N.H., in 1996, and traveled widely afterwards as a Russian journalist. Greene asked about the telephone on which she is said to take orders from the Kremlin. “Yeah, it’s right here,” she said, laughing. “I use it whenever I have to discuss something [for which I need] a secure line…. Just today I talked to the Russian central bank, discussing some issues of RT finances that probably shouldn’t be discussed on an open line.”

Greene asked if she had an opinion about Putin and his policies.

“I have tons of opinions….To understand Russia’s fascination about Putin – and I think this is something that is completely not being understood in the West and in the mainstream media. And the reason why it’s not being understood is because people didn’t live here through the ’90s.

“In a town like mine, I probably, at that time, wouldn’t name a single person whom I personally knew who wanted to stay in Russia. Can you imagine that? All of the people I knew wanted to leave because we saw our country as something horrible, falling apart, that will only continue to fall apart. There were numerous wars going on. And then came Putin, and he stops all that. And we saw it in our lives. People around started – first of all, they stopped being hungry. Then they stopped having one pair of shoes for both my sister and me, you know, and wearing them in a row – and my mom. So for three of us [laughter], one pair of normal shoes – that all stopped. It all seemed magic….

“Not just mine – it’s everybody I know. And when I’m saying – I want to underline this. It would be an extremely difficult task to find a single person who lived worse before Putin than now, very difficult.’’

Careening along to stay within the bounds of his allotted time, Greene asked the next question: “If investigations revealed things about Vladimir Putin that could ultimately lead to him leaving office, would you be ready to carry out an investigation like that to its fullest here?”

SIMONYAN: “If I really sincerely thought that what Putin is doing is harmful for my country and for my people and it needs to be stopped, I wouldn’t hesitate to do that.’’

GREENE: “This – that’s not – I think you recognize this. That’s not your image or RT’s image on the outside.’’

SIMONYAN: “I understand that. I understand that. What are you going to do, you know, when the mainstream media, again and again and again, publish stories about us that are completely false? You know, that’s the image [they have of us]. Why do they do that? You tell me. I don’t know.’’

I don’t spend much time with RT itself. I scan the email version of the compendium of English-language news about Russia published nearly every day as Johnson’s Russia List, by independent journalist David Johnson. I skim most of what U.S. and British newspapers are saying, and a fair amount of RT content as well.

I am occasionally startled by what the Russian network is reporting that the Western papers are not, as was the case last week, when RT published Putin’s remarks at a session of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. Megyn Kelly, of NBC, was serving as his interlocutor, to good effect. It was at a sidebar news conference that Putin suggested that “patriotically minded” Russian hackers might have meddled in U.S. politics. JRL, I find, is a far better guide to developments in Russia than the coverage of any single newspaper.

As for the point that Simoyan sought to make on NPR about Putin’s popularity in Russian public opinion polls, it was made at much greater length and depth, in Second Hand Time: The Last of the Soviets (2013), by Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich. The author’s earlier works include Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster (1997); Zinky’s Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War (1992); The Last Witnesses (1985), recollections ofRussians who were children during World War II, and War’s Unwomanly Face (1982), about the experiences afterward of Russian women who fought in World War II.

Alexievich, 69, was recognized in 2015 with the Nobel Prize for Literature – an award that, like many other distinguished prizes, is among the truth disciplines that Fuller had in mind. Seeking to explain Putin’s popularity, Alexievich last year told Rachel Donadio, of The New York Times, “In the West, people demonize Putin. They do not understand that there is a collective Putin, consisting of some millions of people who do not want to be humiliated by the West. There is a little piece of Putin in everyone.”

What, then, about Putin’s repeated denials that his government backed various attempts to interfere with U.S. elections in 2016? In Washington last week, that still seemed a question worth asking. Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) asked former FBI director Comey, “Was the Russian activity in the 2016 election a one-off proposition, or is this part of a long-term strategy? Will they be back?”

“Oh, it’s a long-term practice of theirs,” Comey responded. “It stepped up a notch in a significant way in ’16. They’ll be back. There should be no fuzz on this whatsoever,” Comey said. “The Russians interfered in our election during the 2016 cycle. They did it with purpose. They did it with sophistication. They did it with overwhelming technical efforts.” Later, he returned to the topic:

“The reason this is such a big deal. We have this big messy wonderful country where we fight with each other all the time. But nobody tells us what to think, what to fight about, what to vote for except other Americans. And that’s wonderful and often painful. But we’re talking about a foreign government that, using technical intrusion, lots of other methods tried to shape the way we think, we vote, we act. That is a big deal. And people need to recognize it. It’s not about Republicans or Democrats. They’re coming after America, which I hope we all love equally. They want to undermine our credibility in the face of the world. They think that this great experiment of ours is a threat to them. So they’re going to try to run it down and dirty it up as much as possible. That’s what this is about and they will be back. Because we remain — as difficult as we can be with each other, we remain that shining city on the hill. And they don’t like it.’’

Special prosecutor Robert Mueller’s report on all aspects of Russian interference in the U.S. elections will go about as far as can be hoped in resolving doubts on this particular issue – diminishing the “fuzz” and confusion surrounding it. Clarity with respect to Russian hacking is one thing. Determining its effect on the 2016 election will be difficult, probably impossible, to resolve.

As for that cherished image of a shining city on a hill? As my friend Richard Pitkin says, there is a little city-on-a-hill in all Americans. It is a complicated sort of truth about which even Russian journalists and scholars may have a say.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran journalist reporting and commenting on economic, political and media matters, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

David Warsh: The wellsprings of Russian hacking

This passage leapt out at me last week as I read Everyone Loses: The Ukraine Crisis and the Ruinous Contest for Post-Soviet Eurasia (Routledge, 2017), by Samuel Charnap and Timothy Colton, a slim and well-balanced recounting of events at the center of the present low state of U.S.-Russia relations.

“Unless Putin changes course, at some point in the not-too-distant future, the current nationalistic fever will break in Russia. When it does, it will give way to a sweaty and harsh realization of the economic costs. Then… Russia’s citizens will ask: What have we really achieved? Instead of funding schools, hospitals, science and prosperity at home in Russia, we have squandered our national wealth on adventurism, interventionism and the ambitions of a leader who cares more about empire than his own citizens.’’

The speaker is Victoria Nuland, assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs in the Obama administration. She was testifying before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in May 2014, not long after Russia annexed the Crimea.

Many in the Russian elite took Nuland’s remark as “a de facto declaration of political war,” according to Sergei Karaganov, an adviser to Russian President Vladimir Putin, in a letter to the authors. A sanctions slugfest followed the Crimean takeover, intensifying after pro-Russian rebel or Russian forces in eastern Ukraine brought down a Malaysia Airlines passenger jet on July 17, 2014. “Regime change,” an objective of U.S. foreign policy in Iraq, Libya and Syria, the Russians concluded, apparently extended to their country as well.

The Ukraine affair and its consequences seem worth remembering after a week when Putin, speaking to reporters at a meeting in St. Petersburg, conceded that private Russian hackers may well have been involved in probing U.S. polling machinery and leaking emails during our elections last year. So might others around the world have been involved.

“Hackers are free-spirited people, like artists,” said Putin. “If artists wake up in the morning in a good mood, they paint all day. Hackers are the same. If they wake up, read about something going on in relations between nations, and have patriotic leanings, they may try to add their contribution to the fight against those who speak badly about Russia.” His government hadn’t been doing the work, Putin asserted. He doubted that any amount of hacking could much influence the electoral outcome in another country.

Andrew Higgins, of The New York Times, wrote from Moscow,

“The evolution of Russia’s position on possible meddling in the American election is similar to the way Mr. Putin repeatedly shifted his account of Russia’s role in the 2014 annexation of Crimea and in armed rebellions in eastern Ukraine. He began by denying that Russian troops had taken part before acknowledging, months later, that the Russian military was ‘of course’ involved.’’

Thus did the attribution problem finally turn into a question of military and industrial organization in Russia’s rapidly growing computer establishment, broadly defined. It seems a safe bet that many, perhaps most, of the hacks detected by U.S. intelligence services during 2016 were of Russian origin, though that doesn’t mean that Putin directed them or even authorized them with any precision. Clearly the level of Russian antipathy towards Clinton was high.

Already in her first presidential campaign, in 2008, Clinton had scorned Putin. George W. Bush might have claimed he had looked into Putin’s eyes and gotten “a sense of his soul,” but she knew better. “He was a KGB agent – he doesn’t have a soul,” she told a fund-raising crowd. As secretary of state, she harshly reproached Russia for fraud and intimidation after the parliamentary elections of 2012 – on the eve of Putin’s campaign for a third presidential term.

“Putin was livid,” wrote reporter Mark Lander, White House correspondent for The New York Times, in Alter Egos: Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and the Twilight Struggle over American Power. (Random House, 2016). Clinton had sent “a signal” to “some actors in our country,” Putin claimed. Protesters took to the streets in Russia’s first major demonstrations since the 1990s. U.S. cheerleaders hopefully dubbed it “the Snow Revolution.”

As it happened, Clinton’s spokesperson in those days was Nuland. Born in 1961, a 1983 graduate of Brown University, is daughter of surgeon-author Sherwin Nuland, wife of neoconservative commentator Robert Kagan. She entered government service as chief of staff to Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott during the Clinton administration. She became Vice President Dick Cheney’s national-security adviser on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, and afterwards served four years as ambassador to NATO. Nuland faced sharp questions about her role as Clinton’s press aide in the wake of the Benghazi attack, but was confirmed as an assistant secretary of state in September 2013 – just in time for the Ukrainian crisis.

After she turned up passing out cookies to Ukrainian demonstrators in Kiev, Nuland was the victim of the very first notable Russia hack, recorded and posted on YouTube, discussing with U.S. Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt who should serve in the Ukrainian leadership following the flight of president Viktor Yanukovych to Moscow. “Fuck the E.U.,” she famously said, referring to the suggestion that the European Union, rather than the United Nations, should serve as a mediator in Ukraine.

Nuland, and her former mentor Talbott, were high up in the plans for a Clinton administration in 2016. Last week Albright Stonebridge Group, a strategy and commercial diplomacy firm, announced she would become a senior counselor. The Russians, like nearly everyone else, had been preparing for President Clinton. Instead they got President Trump.

Everyone Loses is an excellent summary of the mess that ensued after massive street protests drove a pro-Russian democratically elected president from office in February 2014. Charap, a senior fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, and Colton, professor of government at Harvard and author of Yeltsin: A Life (Basic, 2008), are eager to propose a set of precondition-free talks.

“The West needs to cease holding out for Russia to surrender and accept its terms. Russia must stop pining for the good old days of great-power politics, be it the Big Three of 1945 {the U.S., Soviet Union and Britain} or the Concert of Europe 1815-1914, and accept that its neighbors will have a say in any agreement that affects them. The neighbors should stop seeking national salvation from without, and recognize that it will be up to them, first and foremost, to bring about their countries’ security and well-being.’’

But then Everyone Loses was written before the U.S. election. In order to focus narrowly on the fate of the so-called In-Betweens (Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) and the Central Asian nations along the Russian periphery (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan), the authors left everything out of their book that didn’t “bear directly” on the lose-lose situation that grew out of the crisis in Ukraine. That includes NATO expansion, divergences over Russia’s wars in Chechnya, matters of ballistic-missile defense, the U.S. occupation of Iraq, the civil war in Syria and U.S. intervention in Libya.

That is, of course, no way to understand the larger situation. The Russians are no angels. But it is the U.S. that has been on a bender since 1989. A complicated rethinking of U.S.foreign policy is in store. The largely accidental election of Donald Trump has confused the issue. But that leaves plenty of time for the retracing of steps before the next election.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist on economic, political and media matters, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this first ran.

David Warsh: A 'Red Diaper Baby's' clear-eyed reportage of Russia

Fred Weir, of The Christian Science Monitor, has long seemed to me the most dependable and best-informed North American correspondent in Moscow. His reporting stood out on the agglomeration site Johnson’s Russia List, even before David Johnson offered a collection of 50 of Weir’s dispatches, 1999-2016, as a subscription premium.

Last week provided a striking example. The occasion was a Vladimir Putin press conference in Sochi, where the Italian prime minister was visiting.

The New York Times headlined:

“Putin Butts In To Claim There Were No Secrets And Says He’ll Prove it’’

“By Andrew Higgins

“MOSCOW – Asserting himself abroad with his customary disruptive panache, President Vladimir V. Putin on Wednesday jumped into the furor over President Trump’s disclosure of classified information to Russian diplomats, declaring that nothing secret had been revealed and that he could prove it.

“Mr. Putin, who has a long record of seizing on foreign crises to make Russia’s voice heard, announced during a news conference in Sochi, Russia, the Black Sea resort that has become his equivalent of Mr. Trump’s Mar-a-Lago, that he has a “record” of the American president’s meeting at the White House with two senior Russian officials and was ready to give it to Congress — so long as Mr. Trump does not object.’’

In contrast, the Monitor’s account tells a substantially different story:

“As controversy swirls around Trump, Russia watches helplessly’’

“Many in Russia had hoped that the new president could help smooth relations between Moscow and Washington. But as Russia-tied scandals paralyze Trump’s administration, now the Kremlin just want US-Russia diplomacy not to get worse’’

“By Fred Weir

“MOSCOW —When Russian President Vladimir Putin offered on Wednesday to provide Congress with a transcript of his foreign minister’s controversial meeting last week with President Trump in the Oval Office, it was not warmly received by US politicians.

“But debating the legitimacy of the offer – nominally to prove that no classified information changed hands – may be missing the point, Russian foreign-policy experts say.

“Rather, its greater significance may be as a sign of just how alarmed Mr. Putin and the Kremlin are becoming about what’s happening in Washington.

“Kremlin watchers say they feel like helpless observers amid the firestorm of the Russia-related scandals engulfing the Trump administration. While the Kremlin tries to advance what Russian observers say are sincere efforts to establish normal dialogue with a new US president, it is taken in Washington to be further evidence of political collusion between Mr. Trump and Russia.’’

There was no snappy language in Weir’s story, no sly equation of Sochi with Mar-a-Lago, no dwelling on Putin’s insulting diagnosis of the Washington outcry (“Either they don’t understand the damage they’re doing to their own country, in which case they are simply stupid, or they understand everything, in which case they are dangerous and corrupt”).

Instead, Weir reminded readers of the context of the discussion – a Russian airliner lost to an ISIS bomb over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula in November 2015. He quoted at length several Russian sources on their general perplexity at American developments, including Fyodor Lukyanov, a senior Russian foreign-policy analyst:

“We are very confused and even a bit terrified by what we see unfolding in Washington. The name of Russia keeps coming up, but we don’t feel like we have anything to do with this. This level of paranoia is beyond rational, and the only way we can make sense of it is that there is an attempt by political forces to play the Russia card as a weapon to destroy Trump. It’s not that we especially want to save Trump, but the growing fear is that any chance of improved US-Russia relations will be vaporized in this war against him.’’

A Canadian citizen, Weir moved to Moscow in 1986 as a correspondent for the Canadian Tribune, a now-defunct weekly newspaper published by Canada’s Communist Party. He was a third-generation “red diaper baby,” nephew of an influential Comintern agent, a member of the party himself. He had studied Russia as a graduate student but had not contemplated living in the Soviet Union. Now Gorbachev had come to power, the first general secretary born after the 1917 revolution. Weir wanted to see the situation close up.

He traveled widely in the late Eighties for the Tribune, as the Soviet empire began to come apart. He wrote a book on Gorbachev’s reforms, conducted two cross- country tours of Canada as well, promoting his work and sampling opinion He witnessed the optimism of perestroika, the enthusiasm for open elections, the surfacing of ancient ethnic hatreds, as the Soviet regime loosened its grip.

By the Nineties, the economy was falling apart, all but the “cooperatives,” the private firms Gorbachev had permitted to be formed. Weir’s friends, members of the educated elite, had begun complaining of “the theater of democracy.”

In an autobiographical account that he wrote in 2009 (“A Red Diaper baby in Russia witnesses the Rise of Vladimir Putin,” unfortunately no longer online), Weir wrote,

“Sometime in the spring of 1991, I realized how far they had taken this. I was invited to a garden party at the country home, of Andrei Brezhnev, nephew of former Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, in Zhukovna, an elite dacha settlement outside of Moscow. One of the guests, whom I had known for years as a functionary of the Komsomol (the Young Communist League) rolled up in a shiny white Volvo and told me he was now president of an export-import firm. Another, whom I’d often dealt with as an official of the Tribune’s fraternal newspaper, the Soviet Communist Party organ Pravda, boasted that he’d just been hired at a private bank. A third, even more surprising because he was the son of renowned Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov, leaned over the table and handed me a card that announced him as an “international business consultant.”

Over the next few years after that gathering], Weir worked on a book with David Kotz, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Revolution from Above: The Demise of the Soviet System and the New Russia (Routledge 1997), was revised and reissued in 2007 as Russia’s Path from Gorbachev to Putin. The authors’ thesis – that the Soviet system had been overthrown by its own ruling elite – was novel and controversial when first proposed, but has come to be more widely accepted for having been borne out by events. Kotz’s own book about the United States, The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism (Harvard, 2015) has fared less well, though perhaps it is too soon to tell. (“The analysis offered in this book suggests that capitalism is not only in a period of structural crisis at this time but in a structural crisis that has no easy path to desirable resolution. This historical turning point may indeed be a turning point for humanity.”)

Instead of morphing into a businessman like his friends, Weir became a mainstream journalist. He pieced together a living writing for the Hindustan Times; The Independent, of London; South China Morning Post; and, since 1998, as the Monitor’s correspondent. (The venerable Boston-based daily discontinued its print editions in 2008, but maintains a string of excellent correspondents around the world for its digital operations; its Moscow correspondents over the years — Edmund Stevens, Charlotte Saikowski, Ned Temko, and Paul Quinn-Judge — have been especially admired.)

Married, with two children, Weir lives in a small village near Moscow. He is a latter-day John Reed who has lived to tell the story. To read through his Monitor clips over the years is to glimpse the present day in the making.

It seems clear, not just from Weir’s reporting, that the Russian president doesn’t understand the situation that has developed in the United States. Nor have Putin and his counselors taken public account of their own part in making matters worse, by encouraging hacking of e-mail and servers during the campaign.

It’s true that Democrats are using Trump’s longstanding and extensive conflicts of interest in Russia to attack the American president. Yet there were legitimate questions about various relationships during the campaign that led to the appointment last week of former FBI Director Robert Mueller to oversee the Department of Justice investigation.

The fracas has to do mainly with Trump’s unsuitability to the job he sought and won – the dog who chased and caught the car. As Slate’s Jacob Weisberg wrote yesterday, in the Financial Times, “The US president violates democratic norms and expectations around presidential conduct. And with each fresh outrage, the American system’s ultimate political sanction [impeachment] becomes more thinkable.” Trump has no powerful friends in Washington – only allies whose loyalty is tested with each new gaffe. It will take time, but, as of this week, a Pence administration seems almost inevitable.

David Warsh is a veteran business, media and political columnist, economic historian and proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this first ran.

Don Pesci: What about the Clinton-Putin connection?

"The Stolen Kiss,'' by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1786).

VERNON, Conn.

The last few weeks of 24-7 news has been dripping with unintended irony.

Just as the Democratic Party was setting up to attribute former Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s loss to political stumble-bum Donald Trump as a result of Russian President Vladimir Putin's interference in her campaign, President Trump bombed an air base of Syrian dictator Bashir Assad, Mr. Putin’s Kewpie Doll. The bombing served to mute some of the more outrageous claims. Everyone but Connecticut Sen. Dick Blumenthal has been investigating the Trump-Putin connection.

Along with a chorus of other Democrats, Mr. Blumenthal lately has been calling for a special prosecutor to investigate the Trump-Putin connection but, oddly, not the Clinton-Putin connection. While Mrs. Clinton was secretary of state, tons of high grade uranium moved under her winking eye from the United States to Russia.

Warming to Putin, Mrs. Clinton presented Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov with a defective “reset button.”

CNN noted at the time:

“When it comes to Russia, the Obama administration has been talking about ‘pressing the reset button.’ It’s meant to symbolize a possible new start in U.S./Russian relations, which ‘crashed’ after Russia invaded Georgia last August [2009].

“‘I would like to present you with a little gift that represents what President Obama and Vice President Biden and I have been saying and that is: 'We want to reset our relationship, and so we will do it together....'

“‘We worked hard to get the right Russian word. Do you think we got it?’ she asked Lavrov, laughing.

“‘You got it wrong,’ said Lavrov, as both diplomats laughed.

“‘It should be 'perezagruzka' [the Russian word for reset],’ said Lavrov. ‘This says 'peregruzka,' which means ‘overcharged.’”

The overcharged Putin was understanding. Sending a message of his own, Putin invaded and annexed Crimea, a part of Ukraine. Mrs. Clinton winked. Her eyes were fixed on the prize; the term-limited president later would endorse Mrs. Clinton's bid to continue his legacy. How could she lose to a New York real estate developer whom even Bill Buckley tagged “a vulgarian?”

She did lose. Democrats theorized that she lost owing to the gross interference in her campaign of Putin and FBI Director James Comey, now fired by Trump. Concerning Mrs. Clinton’s loss to the vulgarian, Republicans and Democrats have agreed to disagree. Republicans think that Mr. Putin, advised that Mrs. Clinton would win the election, intervened to weaken her inevitable presidency.

They argue further that Mrs. Clinton lost because her own campaign was defective. Further, the damaging e-mails circulating during her campaign were not forged by Putin’s intelligence operatives; they were written by Mrs. Clinton's operatives and circulated through her private unsecured server which, Mr. Blumenthal may wish to note, is a violation of law.

Democrats now argue that Mrs. Clinton might have prevailed in the general election were not Mr. Comey such a duffer. Mr. Trump has now fired Mr. Comey because, according to his dismissal letter to Mr. Comey, he is “not able to effectively lead the Bureau.”

In Mr. Blumenthal’s mind – and in the Democratic Party campaign cheat-sheets – all this is wondrously connected: The firing of Comey and Mr. Trump’s cozy posture with Mrs. Clinton’s past reset-chum necessitate the need to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate the Gordian knot of suppositions put together by Democrats to rescue our democracy from a fascist president.

Here is Bill Curry, former comptroller of Connecticut and two-time Democrat gubernatorial contender, on the fascist:

“Trump isn't just Putin's pal. He's Putin. His firing of Comey is an all-out attack on the rule of law. We have only one branch of government left in anything close to working order and he seeks to destroy it. This is now clear: Anyone still opposed to appointing a special prosecutor is a traitor to our Constitution. It is time to call Trump what he is-- a flat out fascist-- and to call his ceaseless assaults on the first amendment and his political opponents what they are: a fascist power grab. To be silent now is to betray our democracy in the hour of its great peril. In the next few days we'll learn who the real patriots in this country are. I only pray we have enough of them.”

Patriot Blumenthal has not yet called for a special prosecutor to investigate the tortured logic evident in Mr. Curry’s intemperate outburst. That would be a misuse of a special prosecutor. Blumenthal has not yet been asked whether he intends to be present during the U.S. Coast Guard Academy’s upcoming graduation on May 17. The keynote speaker for the event will be our "fascist" president.

Don Pesci (donpesci@att.net) is a political and cultural writer who lives in Vernon, Conn.

David Warsh: Standoff with Russian more perilous than you think

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Hanging over Donald Trump’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping last week was the warning of Graham Allison’s book Destined for War, Can America and China Avoid The Thucydides’ Trap? (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017). The book won’t be in stores for another month, but as long ago as 2013 Xi was talking about the metaphor, well before an early version of the Harvard government professor’s argument appeared in The Atlantic.

What has happened historically when a rising power threatens a ruling one? “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable,” Thucydides wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War. In the 2,400 years since, Allison has found, 12 of 16 such cases have ended in war.

After boasting to the Financial Times, “If China is not going to solve North Korea, we will,” Trump reinforced the message by striking a Syrian airfield while Xi visited him in Florida. Do you wonder why Bashar Assad chose last week to attack a rebellious village with nerve gas? A senior White House official told The Wall Street Journal that the gesture was “bigger than Syria” – representative of how the American president wants to be seen by other leaders. “It is important that people understand this is a different administration [from that of Barack Obama].”

(Different in more ways than one, the spokesman might have added. Trump sought last week to reduce quarrelling among his most senior advisers. How must the president’s record-low favorability rankings in opinion polls complicate the way he is seen by other leaders?)

The defect in The Thucydides Trap is the faulty map it generates. The U.S. is facing not just a single rising power on the world stage, but a diminished and angry giant as well in the form of still-powerful Russia. It has become the habit of much of the U.S. media to tune out Russian President Vladimir Putin on grounds that he does not play by American rules. He murders journalists and opponents, it is said, conducts wars against his neighbors, controls the media, games elections, and has become “President for Life.” Just last week, a Russian court banned as “extremist” an image of the Russian president wearing lipstick, eye-shadow, and false eyelashes, The New York Times reported.

Why not also view Putin as a serious political leader with serious issues governing a nation seeking a new role in the world? One set of these has to do with shaping norms and rules of post-communist civil society. Another set concerns the nation’s economic prospects. Perhaps the most serious of all has to do with the maintenance of Russian’s defense policy – its nuclear deterrent force, in particular. In this respect, The Thucydides Trap misses the point pretty badly.

It’s been 30 years since I consulted an issue of Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The magazine was familiar reading in my youth, when the minute hand on its iconic doomsday clock was set a few minutes before midnight – two, or three, or seven, depending on the circumstances.

For a few years after 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved into 15 independent states, the clock showed a comforting 17 minutes before the hour. The peril has been growing ever since. Earlier this year the editors moved the interval to two-and-a-half minutes – the most alarming warning since the high-peril year of 1984.

Last month, BAS authors Hans Kristensen, Matthew McKinzie, and Theodore Postol explained, The U.S. nuclear forces modernization program underway for 20 years has routinely been explained to the public as a means to preserve the safety and reliability of missile warheads. In fact, the program has included an adjustment that makes each refurbished warhead much more likely to destroy its target.

A new device, a “super-fuze,” has been quietly incorporated since 2009 into the Navy’s submarine–based missile warheads as part of a “life-extension” program. These “burst-height compensating” detonators make it up to three times more likely that its blast will destroy its target than their old “fixed–height” triggers.

Because the innovations in the super-fuze appear, to the non-technical eye, to be minor, policymakers outside of the U.S. government (and probably inside the government as well) have completely missed its revolutionary impact on military capabilities and its important implications for global security.

The result, the BAS authors estimated, is that the US today possesses something close to a first-strike capability. Already US nuclear submarines probably patrol with three times the number of enhanced warheads that would be required to destroy the entire fleet of Russian land-based missiles before they could be launched. Yes, the Russians have submarine-based missiles, too. And they are understood to be developing ultra-high-speed underwater missiles that could destroy American harbors.

But the very existence of the possibility of a pre-emptive strike will surely make Russian strategists jumpy, the BAS authors say. And since Russian commanders lack the same system of space-based infrared early-warning satellites as the U.S., they could expect only half as much time as the Americans have in which to decide whether or not they are facing a false alarm – fifteen minutes as opposed to half an hour. A slim margin for error in judgement has become much thinner.

When Science magazine polled experts about the BAS story, two of the most prominent judged the report to be “solid” or “true.” Thomas Karako, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, was unpersuaded. He derided the “breathless exposé language” and dismissed the authors’ concerns about Russia’s discomfiture. You can make an early acquaintance with the March 1 BAS story here, if you like. A wider, fuller examination of the latest chapter in the story of the doomsday clock has only just begun.

David Warsh, a veteran journalist focusing on economic and political matters and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

David Warsh: Journalism, Russia's 'hybrid war' and the U.S. elections

St. Basil's Cathedral, on Red Square, in Moscow.

The other week, in which Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions’s visit with the Russian ambassador dominated the news, the most interesting thing I read was a 13,000-word article in The New Yorker. It exemplified all the preconceptions typical of what I have come to think of as reporters of the Generation of ’91.

David Remnick, b. 1958, was Moscow bureau chief in 1988-1992 for The Washington Post, before he moved to become The New Yorker’s editor, a job he got in 1998. He wrote Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire, for which he won a Pulitzer Prize, in 1993. Evan Osnos, b. 1976, joined the magazine from The Chicago Tribune in 2008 and covered China for five years. Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China appeared in 2014 and was a Pulitzer finalist. Joshua Yaffa is a journalist based in Moscow. He has written for The Economist and The New York Times Magazine.

Nothing in The New Yorker’s article – “Active Measures: What lay behind Russia’s interference in the 2016 election – and what lies ahead?’’ – was quite as punchy as the art that accompanied it. The magazine’s traditional anniversary cover featured Vladimir Putin, as a dandy peering through a monocle at a raging butterfly Trump, instead of the customary rendering of Eustace Tilley. That was non-committal enough, though it reminded me of the magazine’s 2014 Sochi Olympics cover, a figure-skating Vladimir Putin leaps while five little Putin lookalikes feign lack of interest from the judges’ stand.

More alarming was the art opposite the opening page, Saint Basil’s Cathedral, in Moscow, administering a jolt of light (a digital illumination ray?) to the White House from the skies above. The caption states, “Democratic National Committee hacks, many analysts believe, were just a skirmish in a larger war against Western institutions and alliances.”

The article was organized in five little chapters.

In “Soft Targets,” Putin orders an unprecedented effort to interfere in the U.S. presidential election. It is a gesture of disrespect, ordered out of pique and resentment of perceived U.S. finagling in the 2012 Soviet election, intended to be highly public.

In “Cold War 2.0,” the Obama administration is caught flat-footed by the campaign and fails to respond effectively. The Russians have adopted a new and deeply troubling offensive posture “that threatens the very international order,” a former Obama official states.

In “Putin’s World,” a capsule history of the decline of Russian pride during the 1990s is presented alongside an argument for the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Putin’s mistrust of democracy at home is described, as well as his recoiling from the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Differences between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama after the annexation of Crimea are recounted: She sometimes favors the use of military force whereas he does not.

In “Hybrid War,” Russia becomes technically adroit at cyberwarfare and experiments with a digital blitz on Estonian communications after a statue of a Soviet soldier is removed; meanwhile, the U.S. unleashes its Stuxnet computer virus on Iran’s uranium-refinery operations. The Russian Army chief of staff, Valery Gerasimov, is introduced, along with his 2013 article, “The Value of the Science Is in the Foresight’’ urging “the adoption of a Western strategy,” combining military, technological, media, political and intelligence tactics to destabilize a foe, the article having “achieved the status of legend” as theGerasimov doctrine, following the invasion of Ukraine.

An estimated thousand code warriors are said to be working for the Russian government on everything from tapping former Undersecretary of State Victoria Nuland’s cell phone in Kiev (“a new low in Russian tradecraft”) to the forthcoming French and German elections. Finally, the hacking campaign against the Democratic Party is rehashed, and Clinton campaign manager John Podesta says the interaction between Russian intervention and the FBI “created a vortex that produced the result” – a lost election.

In “Turbulence Theory,” Trump is said to be a phenomenon of America’s own making, like the nationalist politicians of Europe, both the consequence of globalization and deindustrialization, but Russia likes the policies that are the result: Leave Russia alone and don’t talk about civil rights. Meanwhile, the hacking campaign may have backfired, and Trump may no longer have the freedom to accommodate Russian ambitions as might have been wished, but at least Russia has come up with a way to make up for its economic and geopolitical weakness, namely inflict turbulence on the rest of the world.

Three things about this assessment stand out.

Putin’s views of U.S. foreign policy are not integral to the account: They are presented in two widely separate sections, one on the history of U.S. “active measures,” the other on changes in his opinion wrought by the war in Iraq.

Putin is quick to accuse the West of hypocrisy, the authors write, but his opinions, and those of others, especially who compare the invasions of Crimea and Iraq (where the U.S. immediately set out to build an embassy for 15,000 workers) are dismissed as “whataboutism,” exercises in false moral equivalence. NATO expansion is more or less taken for granted. The military alliance’s extension to the borders of Russia forms no part of the narrative.

Second, no attention is paid to Putin’s problems, aside from a nod to his suppression of oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the rock group Pussy Riot. His plans for a Eurasian Union, which were at the heart of the Ukraine crisis, go unmentioned. There’s nothing about the centuries-old struggle between Westernizers and Slavophiles who oppose policies that would tie Russia more closely to the West.

Third, the history of the Cold War itself gets short shrift. The genesis of the doctrine of “hybrid war,” ascribed to General Gerasimov, is described at length in The Last Warrior: Andrew Marshall and the Shaping of Modern American Defense Strategy, by Andrew F. Krepinevich and, Barry D. Watts (Basic Books, 2015). Marshall founded the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment. In 1973 he described what would become a dramatic strategic shift:

“In general we need to look for opportunities as well as problems; search for areas of comparative advantage and try to move the competition into these areas; [and] look for ways to complicate the Soviets’ problems.’’

Many factors led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. “Active measures,” of the sort propounded by Marshall, were prominent among them. You can hardly be surprised that the Russians have sought to master new techniques. The underlying proposition of The New Yorker’s article is that the world is, or at least it should be, unipolar, with the U.S. in charge of its democratic values. After all these years, the Russians still don’t agree.

David Warsh, a veteran financial and political columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

David Warsh; Trump is no Putin

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

One thing you should know about Vladimir Putin: He gives a good speech. Probably you don’t know that he does. Here are three brief excerpts, from occasions that presumably most Russians remembers, more vividly than snippets in translation can convey.

In September 2004, after the Beslan massacre, in which 334 hostages were killed by Chechen terrorists, 186 of them children:

“Today we are living in conditions formed after the disintegration of a huge great country, the country which unfortunately turned out to be nonviable in the conditions of a rapidly changing world…. [D]espite all the difficulties, we managed to preserve the nucleus of that giant, the Soviet Union. We called the new country the Russian Federation. We all expected changes, changes for the better, but found ourselves absolutely unprepared for much that changed in our lives.… We live in conditions of aggravated internal conflicts and ethnic conflicts that before were harshly suppressed by the governing ideology. We stopped paying attention to issues of defense and security…. [O]ur country which once had one of the mightiest systems of protecting its borders, suddenly found itself unprotected from either West or East.’’

In February 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, after the American invasion of Iraq (which he, the Germans, and French had opposed) erupted in sectarian violence, sending an estimated 2 million Iraqis out of the country:

“The unipolar world that had been proposed after the Cold War did not take place…However one might embellish this term, at the end of the day it refers to one type of situation, namely one center of authority, one center of force, one center of decision-making. It is a world in which there is one master, one sovereign. And at the end of the day this is pernicious not only for all those within this system, but also for the sovereign itself because it destroys itself from within….’’

‘’Today we are witnessing an almost uncontained hyper use of force – military force – in international relations, force that is plunging the world into an abyss of permanent conflicts. … [I]ndependent legal norms are, as a matter of fact, coming increasingly close to one state’s legal system….First and foremost, the United State has overstepped its national borders in every way. This is visible in the economic, political, cultural, and educational policies it imposes on other nations. Well, who likes that?’’

In 2008, Russia briefly went to war with Georgia, in order to discourage Georgian ambitions to join the NATO alliance. In 2011, NATO launched airstrikes in Libya to prevent Muammar Qaddafi from attacking insurgents in eastern Libya, greatly irritating the Russian government. In 2013, the U.S. nearly went to war with Syria, before Putin persuaded Bashar al-Assad to surrender some ofSyria’s stocks of chemical weapons.

And in March 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea, not long after the flight to Moscow of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, following three months of demonstrations joined by, among others, U.S.S Assistant Secretary of State for Eurasian Affairs Victoria Nuland and Sen. John McCain:

“They are constantly trying to sweep us into a corner because we have an independent position, because we maintain it and because we call things like they are and do not engage in hypocrisy. But there is a limit to everything. And with Ukraine, our western partners have crossed the line, playing the bear and acting irresponsibly and unprofessionally.

“After all, they were fully aware that there are millions of Russians living in Ukraine and in Crimea. They must have really lacked political instinct and common sense not to foresee all the consequences of their actions. Russia found itself in a position it could not retreat from. If you compress the spring all the way to its limit, it will snap back hard.’’

I spent

week re-reading The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin (Knopf, 2015), by Steven Lee Myers, New York Times correspondent in Moscow for seven years during the period that the Russian president consolidated his power. It is a superb book, knowledgeable, thorough, candid, readable, and well-organized. It provides an incisive account of Putin’s youth in Leningrad; his years as a young officer in the KGB, the Soviet security service; his riseto power as a junior member of reform clique that Boris Yeltsin recruited from the re-christened St. Petersburg.

It treats all the familiar domestic stories of the Putin years: his fierce conduct of the second Chechen War; his surprising elevation by Yeltsin; his gradual suppression of private media; the loss of the nuclear submarine Kursk; the Khodorkovsky trials; the Orange and Rose Revolutions in Ukraine and Georgia; the Alexandr Litvinenko, Anna Politkovskaya, and Boris Nemtsov murders; the Sochi Olympics and the trial of the Pussy Riot punk rock band. It gives a brief but even-handed account of Putin’s successful economic reforms. Like all good books, it has a narrative structure and a point of view, and that view is conveyed by the cover photograph, Putin looking haughty, powerful and sinister.

As Putin prepares to run for afourth term next year, Myers concludes:

“After returning to power in 2012 with no clear purpose other than the exercise of power for its own sake, Putin now found the unifying factor for a large, diverse nation still in search of one. He found a millenarian purpose for the power that he held one that shaped his country greater than any other leader had thus far in the twenty-first century. He had restored neither the Soviet Union nor the tsarist empire, but a new Russia with the characteristics and instincts of both, with himself as secretary general and sovereign, as indispensable as the country was exceptional. … He had unified the country behind the only leader anyone could now imagine because he was, as in 2008 and 2012, unwilling to allow any alternative to emerge. ‘’

There is only a fleeting examination of the fundamental issue that has shaped Putin’s view of the U.S. over the past twenty-five years – not American interventions abroad, not its arms placements, not even its enthusiasm for regime change in Russia, but rather the enlargement of NATO over increasingly strong Russian objections, undertaken by the Clinton administration in 1993, and pursued under presidents George W. Bush and Obama. Myers writes, axiomatically, “Most American and European officials accepted as an article of faith that NATO’s expansion would strengthen the security of the continent by forging a defensive collective of democracies, just as the European Union had buried many of the nationalistic urges that had caused so much conflict in previous centuries.”

Why is this The New Tsar’s default view? The Times has habitually viewed itself as an extension of the U.S. State Department in matters large and small, and in this case, the logic of NATO enlargement has been asserted by three presidents whose service has spanned 24 years. Of course, U.S. foreign policy hasn’t always worked out well. TheTimes editorial page supported U.S. intervention in South Vietnam in the early 1960s, and, with aggressive reporting, the invasion of Iraq in 2003. In each case, subsequent events provoked editors to undertake an extensive retracing of their steps. No such soul-searching has yet begun in the matter of NATO enlargement.

Which brings us to the current situation. The Trump-Putin equivalence that is currently all the rage –it was the cover story in The Economist earlier this month – is profoundly misleading. Putin, with consistently high approval ratings, is headed for a fourth term as president. Despite having overplayed his hand in the hacking business, he has a case to make: the US has treated Russia much too casually in the years since the Soviet empire collapsed. Like it or not, we live in a multi-polar world.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump is back on the campaign trail, hoping to salvage his first term. He has a case for better relations to make, too, but, for reasons of temperament, intellect, and his business interests, he is profoundly unsuited to make it. The U.S. debate about U.S.-Russian relations should go forward without equating the leaders of the two countries.

David Warsh is a veteran business and political columnist and economic historian. He is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this first ran.

David Warsh: Trying to make sense of Trump's frenzy of actions

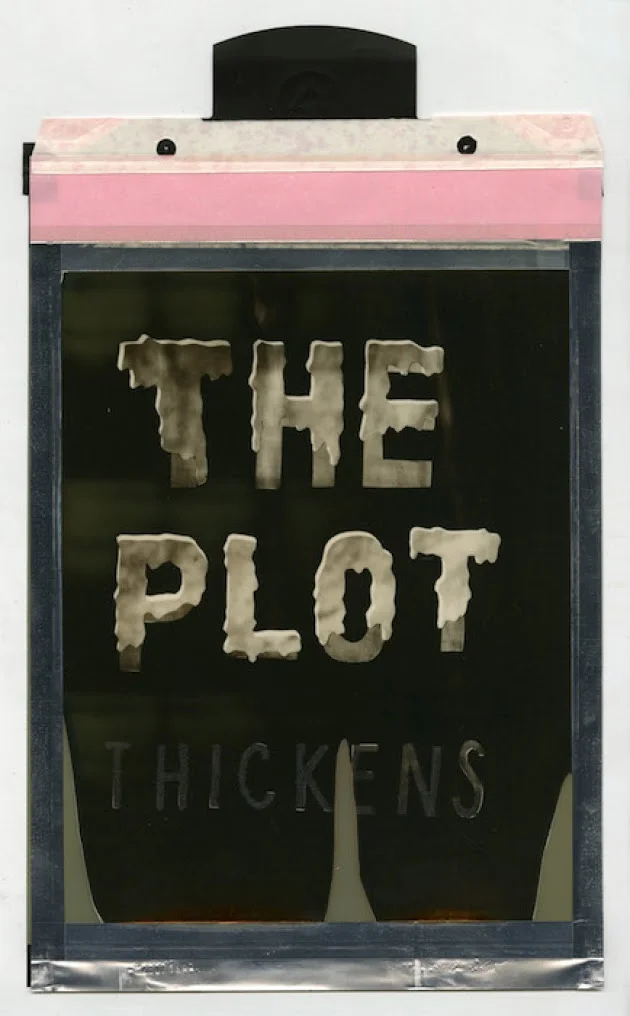

"The Plot Thickens (silver shade instant film), by Corey Escoto, in his show "A Routine Pattern of Troubllng Behavior,'' at Samson Gallery, Boston, through April 1.

The Carnegie Museum of Art observed: 'The two- and three-dimensional works of Corey Escoto meditate on the production and consumption of illusion, both in terms of what we accept as photographic truth and, more broadly, how we distinguish fact from fiction in an ever more manipulated, media-saturated world.''

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The new president has been throwing up all kinds of ideas, orders and initiatives, presumably in hopes that some will find favor with Congress. How to understand what he’s doing? I read some careful newspaper stories, each very good, all slightly different. (WSJ: “Trump’s Week One Off Script”. WP: “Reality Check: Many of Trump’s early vows will probably never happen”. NYT: “Misfires, Crossed Wires, and a Satisfied Smile in the Oval Office”. FT: “A Whirlwind Week in the White House”.) The single most useful insight I came across was that of Politico’s Eliana Johnson, speaking on National Public Radio’s On Point:

“The way to think about this government is sort of like a coalition government, where you’ve got the populist nationalist president in the White House [who’s] going to agree with the Republican majority in Congress on some things, [as] he’s going to agree with Democrats in Congress on other things, but there isn’t a party in Congress that he aligns or sees eye-to-eye with on everything, that’s going to be able to ram through legislation. Same with his cabinet secretaries – they disagree with him on many, many things. I don’t think he nominated secretaries who are pushovers.’’

Of the bewildering array of first steps Trump proposed, none was more interesting to me than a foreign policy initiative when he was expected to call Vladimir Putin, Angela Merkel and Francois Hollande. What might he have said? For many years I’ve thought that Jack Matlock, the career Foreign Service officer who was George H.W. Bush man in Moscow, has understood the situation particularly well. He is the author of Autopsy on an Empire: The American Ambassador’s Account of the Collapse of the Soviet Union (Random House,1995) and Superpower Illusions: How Myths and False Ideologies Led America Astray – and How to Return to Reality (Yale, 2010). Matlock took to his blog to propose a four-paragraph communique for afterwards:

“The presidents agreed that there is no good reason to consider their countries enemies and there are compelling reasons for the United States and Russia to cooperate in solving common problems.

“The presidents recognize that a nuclear war would be catastrophic for humanity, must never be fought, and that their countries bear a special responsibility to cooperate to reduce the nuclear danger and prevent further proliferation.

“Regarding specific issues, they agree to begin, on an urgent basis, consultations with each other and with allies and neighbors regarding ways in which current confrontations could be replaced by cooperation.

“One question that will inevitably arise regards the continuation of U.S. sanctions on Russia. In [Matlock’s] view, these sanctions are now doing more harm than good, but [he] would hope that decisions regarding them would be made in concert with U.S. allies, who have been pressed by the United States to adopt them. Perhaps President Trump could state that he agrees that sanctions are incompatible with the sort of relationship he seeks with Russia, and he intends to explore ways to create conditions that make them unnecessary.’’

It is anybody’s guess which of those among of the frenzy of proposals emanating from the White House might eventually become the basis for blueprints for action. I can’t fault the method the president chose. Throwing much against the wall in hopes that something will stick is an approach to dire circumstances previously associated mainly with Franklin Delano Roosevelt. (Of course, then it was the nation’s circumstances, not the president’s, that were dire.) WSJ columnist Peggy Noonan and Joshua Green, writing in Bloomberg Businessweek, think that Trump is seeking to create a “workers’ party,” composed of “those who haven’t had a real wage increase in the last eighteen years.” I don’t think the populist nationalist in the White House is going to get very far with that.

David Warsh, a longtime financial journalist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this first appeared.

David Warsh: Of Russian hacking and 'minimal democracy'

CHICAGO

I pored over the program of the Allied Social Science Associations, looking for a panel devoted to Russia, the topic uppermost on my mind. (I’m interested in the thinking behind the Russian intervention in the U.S. election.)

The closest I came was a session on the persistent effects of culture and institutions. It had been organized by James Robinson, director of the Pearson Institute for the Study and Resolution of Global Conflicts at the Harris School of Public Policy of the University of Chicago (not dean of the school, as asserted earlier) and author, with Daron Acemoglu, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, of Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (Crown, 2012).

That produced an especially interesting paper, A Theory of Minimal Democracy, by Francesco Trebbi, of the University of British Columbia, Chris Bidner, of Simon Fraser University, and Patrick Francois, also of UBC. Trebbi distinguished between relatively robust democracies, extending all or most of the familiar complement of rights to non-elites — to vote; to form and join associations; to be protected by the rule of law, and by a free press — and those states long known as minimalist democracies These hold regular elections, which may be hotly contested, but otherwise offer ordinary citizens relatively little else. They are widely distributed around the world but little understood: competitive autocracies, non-redistributive democractizations, captives of the resource curse.

Clearly Russia is one. The Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Indonesia, Nepal, Moldova, and Mongolia are others.

A major question is how they change. Does deep culture dominate? Or might institutions — elections, for example — become self-enforcing? Questions like this one are at the heart of the contretemps with Russia: Vladimir Putin apparently believes that Hillary Clinton, as Secretary of State, sought to foment dissent in Russia in 2011, when he ran for a third term as president. Maybe she did.

A new sub-discipline of political economy, revivified by Acemoglu and Robinson, Torsten Persson and Guido Tabellini, and many others, has much to say about the issue, but has only just begun to train a new generation of area experts.

The territory of economics has exploded in the last 55 years, the American Economic Review, which once decorously appeared but five times a year, now arrives with a pound or two of new material every month. The Journal of Economic Literature, established to keep non-specialists abreast of the steadily broadening stream of publications, is approaching fifty; the Journal of Economic Perspectives, designed to communicate developments to an interested lay audience, is celebrating thirty years; four new field journals publish new work in microeconomics, macroeconomics, applied economics, and economic policy. And those are just the organs of the American Economic Association. Universities publish distinguished journals, too, as do other associations, societies, and commercial publishers.

A new entrant, The Annual Review of Economics, has begun to impinge on this established universe slightly since it first appeared, eight years ago. The first Annual Review — of Biochemistry — appeared in 1932. The enterprise proved so successful that the independent publishers who started it prepare today 41 collections of critical surveys of tightly focussed disciplines — including the Annual Review of Financial Economics and the Annual Review of Resource Economics. Established by Kenneth Arrow and Timothy Bresnahan, both of Stanford University, editing of ARE this year passed to Philippe Aghion, of the College de France, and Helene Rey, of London Business School..

By providing more and somewhat higher-level surveys of new important findings and new tools, the ARE has forced, or freed, JEL editor Steven Durlauf, of the University of Wisconsin, to cast his net more widely. The JPE, where Enrico Moretti, of the University of California at Berkeley, has replaced David Autor, of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, now seems more newsy than ever. As for the AER, I zero-in to see what’s new when the mammoth Papers and Proceedings record of the annual meeting arrives in May. Because it offers rapid publication of lightly-vetted articles deemed important, it regularly contains the first reports of inquiries that lead in due course to fault lines and fractures in received wisdom — hence to further spreading of the disciplinary tent.

The meetings themselves still fufill the basic functions. The incoming president and his program committee organize the sessions that are to be published in the Proceedings; he or she invites the Ely lecturer, too. President this year was Nobel laureate Alvin Roth, of Stanford University, an exponent of market design; he chose Esther Duflo, of MIT, who spoke about “The Economist as Plumber: Large-Scale Experiment to Inform the Details of Policy-Making.” Next year Olivier Blanchard will preside, having stepped down from eight years as chief economist of the International Monetary Fund.

A luncheon honored Nobel laureate Angus Deaton, of Princeton University. The John Bates Clark Medal was presented, to Yuliy Sannikov, of Stanford University. Four Distinguished Fellows of the Association were recognized: Richard Freeman, of Harvard University; Glenn Loury, of Brown University; Julio Rotemberg, of Harvard Business School; and Isabel Sawtell, of the Brookings Institution. The exhibit hall bustled a little less than usual, perhaps at the news that Peter Dougherty, a famous economics editor, would soon retire as director of the Princeton University Press.

Robert Shiller, of Yale University, gave the presidential lecture, “Narrative Economics.” He told the audience, “Narratives matter for human thinking, and they ought to matter for economics.” I think so too. There are too few of them. But there’s no time for narrative at the ASSA.

David Warsh, a longtime financial journalist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

Why Trump sucks up to Putin?

Donald Trump, unlike other presidents is the past 40 years, refuses to release his tax returns or other data related to his conflicts of interest, The information below suggests some reasons why:

Why did Putin order hacking to help Trump get elected? Stacey W. Porter posted to Facebook as follows:

1) Trump owes Blackstone/ Bayrock group $560 million (one of his largest debtors and the primary reason he won't reveal his tax returns)

2) Blackstone is owned wholly by Russian billionaires, who owe their position to Putin and have made billions from their work with the Russian government.

3) Other companies that have borrowed from Blackstone have claimed that owing money to them is like owing to the Russian mob and while you owe them, they own you for many favors.

4) The Russian economy is badly faltering under the weight of its over-dependence on raw materials which as you know have plummeted in the last 2 years leaving the Russian economy scrambling to pay its debts.

5) Russia has an impetus to influence our election to ensure the per barrel oil prices are above $65 ( they are currently hovering around $50)

6) Russia can't affordably get at 80% of its oil reserves and reduce its per barrel cost to compete with America at $45 or Saudi Arabia at $39. With Iranian sanctions being lifted Russia will find another inexpensive competitor increasing production and pushing Russia further down the list of suppliers.

As for Iranian sanctions, the 6 countries lifting them allowing Iran to collect on the billions it is owed for pumping oil but not being paid for it. These billions Iran can only get if the Iranian nuclear deal is signed. Trump spoke of ending the deals which would cause oil sales sanctions to be reimposed, which would make Russian oil more competitive.

7) Rex Tillerson (Trump's pick for Secretary of State) is the head of ExxonMobil, which is in possession of patented technology that could help Putin extract 45% more oil at a significant cost savings to Russia, helping Putin put money in the Russian coffers to help reconstitute its military and finally afford to mass produce the new and improved systems that it had invented before the Russian economy had slowed so much.

8) Putin cannot get access to these new cost saving technologies OR outside oil field development money, due to US sanctions on Russia, because of its involvement in Ukrainian civil war.

9) Look for Trump to end sanctions on Russia and to back out of the Iranian nuclear deal, to help Russia rebuild its economy, strengthen Putin and make Tillerson and Trump even richer, thus allowing Trump to satisfy his creditors at Blackstone.

10) With Trump's fabricated hatred of NATO and the U.N., the Russian military reconstituted, the threat to the Baltic states is real. Russia retaking their access to the Baltic Sea from Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and threatening the shipping of millions of cubic feet of natural gas to lower Europe from Scandinavia, would allow Russia to make a good case for its oil and gas being piped into eastern Europe.

Sources: Time Magazine, NY Times, The Atlantic, The Guardian UK.

Sent from my iPhone

David Warsh: The gapping Clinton-Obama differences on policy toward an aggressive Russia

Blue nations are in NATO.

Given the high degree of partisan divide following the U.S. election, a discomfiting fact is that Donald Trump is likely to espouse many responsible positions in his role as president, even if he can’t make the case for them himself. This confusing state of affairs has not become obvious yet. But it is inevitable, and we will get used to it. A case in point is the current confusion about Russia.

Trump campaigned throughout the last year and a half on a promise to roll back the Viktor Yanukovych’s pro-Putin government in Ukraine in 2014. He never mentioned the much larger issue that lies behind it, the enlargement of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to Russia’s southern borders, but that is likely what he meant.

In contrast, Hillary Rodham Clinton was equally clear throughout that she intended to increase the pressure on the Russian Federation. She now blames Putin (and FBI Director James Comey) for her loss.

As it happens, Mark Landler, White House correspondent of The New York Times, earlier this year gave us a very good account of her foreign policy views. Alter Egos: Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and the Twilight Struggle over American Power (Random House 2016) was written when Clinton was concerned to burnish her credentials as a hawk in anticipation of the general election.

The climax of the book is worth quoting at length. It comes in September 2014, when Obama invites a dozen foreign-policy experts to a dinner at the White House that has been “planned down to the minute”: an hour of discussion on the Islamic State; another on Russia, and, in particular, the proposal to supply Javelin antitank missiles to Ukrainian troops then fighting the Russian army. Mr. Landler writes:

“As the second hour began, Obama threw down a startling gauntlet.

“’Will somebody tell me, What’s the American stake in Ukraine?’ he asked his guests.

“Strobe Talbott [Deputy Secretary of State for seven years under President Clinton], who spent much of his professional life studying the Soviet threat during the Cold War, was slack-jawed. Preserving the territorial integrity of states liberated from the Soviet Union was an article in faith in Washington, at least for those of Clinton’s generation, who had watched the Soviets invade Hungary in 1956. Talbott argued that the West couldn’t simply stand by while Russia had its way with one of its neighbors. Stephen Hadley, who had been George W. Bush’s national adviser, echoed him. ‘Well, I see it somewhat differently than you do,’ Obama replied. ‘My concern is it will be a provocation and it’ll trigger a Russian escalation that we’re not prepared to match.’ That was a legitimate concern, Talbott granted, but not a reason to give Russia a free pass. ‘Having known Hillary for a long time,’ he told me [Landler wrote],’ I’m pretty sure she would have seen the invasion of Ukraine in a different way, mainly as a threat to the peace of Europe.”’

‘’A year and a day after that dinner, Talbott’s assumption was borne out. Standing on a stage of the Brookings Institution, of which he is president, Talbott introduced Clinton for the first major foreign policy speech of her 2016 presidential campaign. During a question-and-answer period afterward, she was asked how the West could put more pressure on Vladimir Putin. The United States, Clinton said, needed to dial up the sanctions and bring other pressure to bear. Though she didn’t specify it that day, her aides said that would include providing defensive weapons to the Ukrainians…

‘’Clinton wasn’t just talking about guns and butter. Washington, she said, urgently needed a new mindset to deal with an adversary that was going to plague the United States for years to come. It wasn’t so much new as back to the future: The White House would have to recruit old Soviet specialists –‘and I’m looking right at you, Strobe Talbott,’ she said – to dust off their playbooks and devise new policies for fighting Russian aggression. Like the Soviets, the Russians planned ‘to stymie and confront and to undermine American power whenever and wherever they can.”’

On this and many other issues, Landler writes, Obama and Clinton were the product of the experiences of their very different childhoods. She grew up in a middle-class suburb of Chicago, the daughter of a conservative Methodist businessman. Obama grew up in Hawaii, the son of a single mother who moved with him to Indonesia in fourth grade. That, and his “Kenyan roots,” created “a carapace of suspicion,” Landler writes. “Clinton viewed her country from the inside out; Obama from the outside in.” Maybe so, but Trump, who is mentioned twice, fleetingly, in the book, is president-elect.

Obama’s own instincts have served him well enough in foreign policy – in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. But the two secretaries of state he appointed, both of them frustrated presidential candidates, have gone on pursuing the agenda of an enlarged NATO military alliance as devised by Bill Clinton, which they inherited intact from George W. Bush. This is, of course, the deepest source of Russia’s grievance at the United States –Russian leaders thought they had received assurances from James Baker, secretary of state to George H. W. Bush, that there would be no expansion east if Germany was permitted to re-unite under the NATO banner. But the enlargement of the alliance that began in 1997 with Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic admitted to membership, that precipitated a short war in Georgia in 2008, and another in Ukraine in 2014, is still going forward, zombie-like, in the present day.

NATO enlargement never became an issue in the presidential campaign. In a 10-part “Blueprint for Donald Trump to Fix Relations with Russia,” national security expert Graham Allison, former dean of Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, goes as far as he dares. “NATO is the greatest alliance in history and played an essential role in America’s Cold War victory. But today it stands in need of substantial reform.” Its expansion is not mentioned.

Leaders of the United States are henceforth going to have to become accustomed once again to living in a multi-polar world. That won’t be easy to explain, but Trump is going to have to try. Here is Graham Allison again, this time on the likelihood of war with China, from his article last year in The Atlantic, “The Thucydides Trap” (soon to be a book). He is reflecting on the vision of China’s role in the world that President Xi Jinping presented to a meeting of its political and military leadership in 2014:

“The display of self-confidence bordered on hubris. Xi began by offering an essentially Hegelian conception of the major historical trends toward multi-polarity (i.e. not U.S. unipolarity) and the transformation of the international system (i.e., not the current U.S.-led system). In his words, a rejuvenated Chinese nation will build a ‘new type of international relations through a ‘protracted’ struggle over the nature of the international order. In the end, he assured his audience that ‘the growing trend toward a multipolar world will not change.’’’

The nerve of those guys!

Obama is preparing to give a farewell address in Chicago on Jan. 10. Here’s hoping the explainer-in-chief leads with foreign affairs. As good an overall job as he has done in the the past eight years, he still has a lot of explaining to do.

David Warsh, a longtime economic historian and business journalist, in proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this first ran.

Peter Certo: CIA is well practiced in subverting elections

Via OtherWords.org

Even in an election year as shot through with conspiracy theories as this one, it would have been hard to imagine a bigger bombshell than Russia intervening to help Donald Trump. But that’s exactly what the CIA believes happened, or so unnamed “officials brief on the matter” told The Washington Post.

While Russia had long been blamed for hacking e-mail accounts linked to the Clinton campaign, its motives had been shrouded in mystery. According to The Post, though, CIA officials recently presented Congress with a “a growing body of intelligence from multiple sources” that “electing Trump was Russia’s goal.”

Now, the CIA hasn’t made any of its evidence public, and the CIA and FBI are reportedly divided on the subject. Though it’s too soon to draw conclusions, the charges warrant a serious public investigation.

Even some Republicans who backed Trump seem to agree. “The Russians are not our friends,” said Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, announcing his support for a congressional probe. It’s “warfare,” added Sen. John McCain.

There’s a grim irony to this. The CIA is accusing Russia of interfering in our free and fair elections to install a right-wing candidate it deemed more favorable to its interests. Yet during the Cold War, that’s exactly what the CIA did to the rest of the world.

Most Americans probably don’t know that history. But in much of the world it’s a crucial part of how Washington is viewed even today.

In the post-World War II years, as Moscow and Washington jockeyed for global influence, the two capitals tried to game every foreign election they could get their hands on.

From Europe to Vietnam and Chile to the Philippines, American agents delivered briefcases of cash to hand-picked politicians, launched smear campaigns against their left-leaning rivals, and spread hysterical “fake news” stories like the ones some now accuse Russia of spreading here.

Together, political scientist Dov Levin estimates, Russia and the U.S. interfered in 117 elections this way in the second half the 20th Century. Even worse is what happened when the CIA’s chosen candidates lost.

In Iran, when elected leader Mohammad Mossadegh tried to nationalize the country’s BP-held oil reserves, CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt led an operation to oust Mossadegh in favor of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The shah’s secret police tortured dissidents by the thousands, leading directly to the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

In Guatemala, when the democratically elected Jacobo Arbez tried to loosen the U.S.-based United Fruit Co.’s grip on Guatemalan land, the CIA backed a coup against him. In the decades of civil war that followed, U.S.-backed security forces were accused of carrying out a genocide against indigenous Guatemalans.

In Chile, after voters elected the socialist Salvador Allende, the CIA spearheaded a bloody coup to install the right-wing dictator Augusto Pinochet, who went on to torture and kill thousands of Chileans.

“I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people,” U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger purportedly said about the coup he helped orchestrate there.

And those are only the most well-known examples.

I don’t raise any of this history to excuse Russia’s alleged meddling in our election — which, if true, is outrageous. Only to suggest that now, maybe, we know how it feels. We should remember that feeling as Trump, who’s spoken fondly of authoritarian rulers from Russia to Egypt to the Philippines and beyond, comes into office.

Meanwhile, much of the world must be relieved to see the CIA take a break from subverting democracy abroad to protect it at home.

Peter Certo is the editorial manager of the Institute for Policy Studies and the editor of OtherWords.org.

CIA: Putin successfully intervened in the U.S. election to elect Trump