The GOP eyes gutting Social Security

Adapted From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' in GoLocal24.com:

There's a move underway by some Trump advisers and Republican lobbyists to eliminate payroll taxes used to fund Social Security and Medicare Part A. (Medicaid is financed from general budget funds), with the ultimate aim of throwing more people on the tender mercies of Wall Street to finance their retirements.

Associated Press writers Josh Boak and Stephen Ohlemacher reported: “This approach would give a worker earning $60,000 a year an additional $3,720 in take-home pay, a possible win that lawmakers could highlight back in their districts even though it would involve changing the funding mechanism for Social Security, according to a lobbyist, who asked for anonymity to discuss the proposal without disrupting early negotiations.’’

Well, yes, that might be an initially popular way to destroy Social Security. The George W. Bush administration tried to give Wall Street lots of Social Security cash. But the public, understandably doubtful that people in the financial-services industry would put customers’ interests first, pushed back. Then came the Great Crash of 2008….

Philip K. Howard: Congress needs to clean out the stables of long-outdated laws

Government is broken. So what do we do about it? Angry voters are placing their hopes in outsider presidential candidates who promise to “make America great again” or lead a “political revolution.”

But new blood in the White House, by itself, is unlikely to fix things. Every president since Jimmy Carter has promised to rein in bureaucratic excess and bring government under control, to no effect: The federal government just steamed ahead. Red tape got thicker, the special-interest spigot stayed open, and new laws got piled onto old ones.

What’s broken is American law—a man-made mountain of outdated statutes and regulations. Bad laws trap daily decisions in legal concrete and are largely responsible for the U.S. government’s clunky ineptitude.

The villain here is Congress—a lazy institution that postures instead of performing its constitutional job to make sure that our laws actually work. All laws have unintended negative consequences, but Congress accepts old programs as if they were immortal. The buildup of federal law since World War II has been massive—about 15-fold. The failure of Congress to adapt old laws to new realities predictably causes public programs to fail in significant ways.

The excessive cost of American healthcare, for example, is baked into legal mandates that encourage unnecessary care and divert 30 percent of a healthcare dollar to administration. The 1965 law creating Medicare and Medicaid, which mandates fee-for-service reimbursement, has 140,000 reimbursement categories today and requires massive staffing to manage payment for each medical intervention, including giving an aspirin.

In education, compliance requirements keep piling up, diverting school resources to filling out forms and away from teaching students. Almost half the states now have more administrators and support personnel than teachers. One congressional mandate from 1975, to provide special-education services, has mutated into a bureaucratic monster that sops up more than 25 percent of the total K-12 budget, with little left over for early education or gifted programs.

Why is it so difficult for the U.S. to rebuild its decrepit infrastructure? Because getting permits for a project of any size requires hacking through a jungle of a dozen or more agencies with conflicting legal requirements. Environmental review should take a year, not a decade.

Most laws with budgetary impact eventually become obsolete, but Congress hardly ever reconsiders them. New Deal Farm subsidies had outlived their usefulness by 1940 but are still in place, costing taxpayers about $15 billion a year. For any construction project with federal funding, the 1931 Davis-Bacon law sets wages, as matter of law, for every category of worker.

Bringing U.S. law up-to-date would transform our society. Shedding unnecessary subsidies and ineffective regulations would enhance America’s competitiveness. Eliminating unnecessary paperwork and compliance activity would unleash individual initiative for making our schools, hospitals and businesses work better. Getting infrastructure projects going would add more than a million new jobs.

But Congress accepts these old laws as a state of nature. Once Democrats pass a new social program, they take offense at any suggestion to look back, conflating its virtuous purpose with the way it actually works. Republicans don’t talk much about fixing old laws either, except for symbolic votes to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Mainly they just try to block new laws and regulations. Statutory overhauls occur so rarely as to be front-page news.

No one alive is making critical choices about managing the public sector. American democracy is largely directed by dead people—past members of Congress and former regulators who wrote all the laws and rules that dictate choices today, whether or not they still make sense.

Why is Congress so incapable of fixing old laws? Blame the Founding Fathers. To deter legislative overreach, the Constitution makes it hard to enact new laws, but it doesn’t provide a convenient way to fix existing ones. The same onerous process for passing a new law is required to amend or repeal old laws, with one additional hurdle: Existing programs are defended by armies of special interests.

Today it is too much of a political struggle, with too little likelihood of success, for members of Congress to revisit any major policy choice of the past. That’s why Congress can’t get rid of New Deal agricultural subsidies, 75 years after the crisis ended.

This isn’t the first time in history that law has gotten out of hand. Legal complexity tends to breed greater complexity, with paralytic effects. That is what happened with ancient Roman law, with European civil codes of the 18th Century, with inconsistent contract laws in American states in the first half of the 20th Century, and now with U.S. regulatory law.

The problem has always been solved, even in ancient times, by appointing a small group to propose simplified codes. Especially with our dysfunctional Congress, special commissions have the enormous political advantage of proposing complete new codes—with shared pain and common benefits—while providing legislators the plausible deniability of not themselves getting rid of some special-interest freebie.

History shows that these recodifications can have a transformative effect on society. That is what happened under the simplifying reforms of the Justinian code in Byzantium and the Napoleonic code after the French Revolution. In the U.S., the establishment of the Uniform Commercial Code in the 1950s was an important pillar of the postwar economic boom.

But Congress also needs new structures and new incentives to fix old law.

The best prod would be an amendment to the Constitution imposing a sunset—say, every 10 to 15 years—on all laws and regulations that have a budgetary impact. To prevent Congress from simply extending the law by blanket reauthorization, the amendment should also prohibit reauthorization until there has been a public review and recommendation by an independent commission of citizens.

Programs that are widely considered politically untouchable, such as Medicare and Social Security, are often the ones most in need of modernization—to adjust the age of eligibility for Social Security to account for longer life expectancy, for example, or to migrate public healthcare away from inefficient fee-for service reimbursement. The political sensitivity of these programs is why a mandatory sunset is essential; it would prevent Congress from continuing to kick the can down the road.

The internal rules of Congress must also be overhauled. Streamlined deliberation should be encouraged by making committee structures more coherent, and rules should be changed to let committees become mini-legislatures, with fewer procedural roadblocks, so that legislators can focus on keeping existing programs up-to-date.

Fixing broken government is already a central theme of this presidential campaign. It is what voters want and what our nation needs. A president who ran on a platform of clearing out obsolete law would have a mandate hard for Congress to ignore.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, civic leader and writer, is the founder of the advocacy group Common Good and the author, most recently, of The Rule of Nobody.

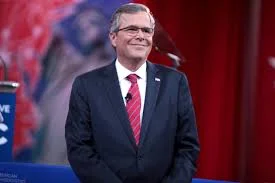

Paul A. Reyes: Jeb Bush has had freebies his whole life

The Republican Party has struggled for years to attract more voters of color. In a recent campaign appearance, candidate Jeb Bush offered yet another useful case study of how not to do it. At a campaign stop in South Carolina, the former Florida governor was asked how he’d win over African-American voters. “Our message is one of hope and aspiration,” he answered. So far, so good, right?

“It isn’t one of division and get in line and we’ll take care of you with free stuff. Our message is one that is uplifting — that says you can achieve earned success.”

Whoops.

With just two words — “free stuff” — Bush managed to insult millions of black Americans, completely misread what motivates black people to vote, and falsely imply that African Americans are the predominant consumers of vital social services.

First, the facts.

Bush’s suggestion that African-Americans vote for Democrats because of handouts is flat-out wrong. Data from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies shows that black voters increasingly preferred the Democratic Party over the course of the 20th Century as it stepped up its support for civil rights.

These days, more than 90 percent of African Americans vote for the Democratic Party’s presidential candidates because they believe Democrats pay more attention to their concerns. Consider that in the two GOP debates, there was only one question about the “Black Lives Matter” movement. When they do comment on it, Republican politicians feel much more at home criticizing that movement against police brutality than supporting it.

Bush is also incorrect to suggest that African-Americans want “free stuff” more than other Americans. A plurality of people on food stamps, for example, are white.

Moreover, government assistance programs exist because we’ve decided, as a country, to help our neediest fellow citizens. What Bush derides as “free stuff” — say, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and school lunch subsidies — are a vital safety net for millions of the elderly, the poor, and children, regardless of race or ethnicity.

How sad that Bush, himself a Catholic, made his comments during the same week that Pope Francis was encouraging Americans to live up to their ideals and help the less fortunate.

Finally, Bush’s crass comment is especially ironic coming from a third-generation oligarch whose life has been defined by privilege.

Bush himself is a big fan of freebies. The New York Times has reported that, during his father’s 12 years in elected national office, Bush frequently sought (and obtained) favors for himself, his friends, and his business associates. Even now, about half of the money for Bush’s presidential campaign is coming from the Bush family donor network.

And what about those corporate tax breaks, oil subsidies and payouts to big agricultural companies Bush himself supports? Don’t those things count as “free stuff” for some of the richest people in our country?

It’s also the height of arrogance for Bush to imply that African Americans are strangers to “earned success.” African-Americans have been earning success for generations, despite the efforts of politicians like Bush — who purged Florida’s rolls of minority voters and abolished affirmative action at state universities.

If nothing else, this controversy shows why his candidacy has yet to take off as expected. His campaign gaffes have served up endless fodder for reporters, pundits, and comics alike.

Sound familiar?

As you may recall, Mitt Romney helped doom his own presidential aspirations by writing off the “47 percent” of the American people he said would never vote Republican because they were “dependent upon government.”

In Romney’s view, they’re people “who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it.”

Sorry, Jeb. The last thing that this country needs is another man of inherited wealth and power lecturing the rest of us about mooching.

Robert Whitcomb: Oregon points to better Medicaid

Unsurprisingly, Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo is getting pushback from interest groups against her goal of “reinventing Medicaid’’ – the federal-state program for the poor. The Ocean State’s Medicaid costs are America’s second-highest per enrollee (Alaska is first) and 60 percent higher than the national average.

Many in the nursing-home and hospital industries will fight the governor’s effort to cut costs even if it can be shown that her plan can simultaneously improve care. After all, the current version of Medicaid has been very lucrative for many in those businesses. The Affordable Care Act has brought them even more money.

As we watch her plan unfold, let’s be very skeptical when we hear lobbyists for the healthcare industry and unions asserting that reform would hurt patients. Lobbyists are adept at getting the public to conflate the economic welfare of a sector’s executives, other employees and owners with its customers’. Ambrose Bierce called politics “a strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles.’’ Often true!

So “nonprofit’’ Lifespan, the state’s largest hospital system, has just hired eight lobbyists to work the General Assembly to defend its interests. (And beware healthcare executives’ citing their businesses’ “nonprofit’’ status. Many of these enterprises take their profit in huge executive compensation.) Some unions are also on the warpath. They worry that reform to reduce the overcharging, waste and duplication pervasive in U.S. health care might reduce the number of jobs.

But economic and demographic reality (including an aging population, widening income inequality and employers’ eliminating their workers’ group insurance) make Medicaid “reinvention’’ mandatory as more patients flood in.

Oregon provides a model of how to do it.

There, in an initiative led by former Gov. John Kitzhaber, M.D., an emergency-room physician, the state has both improved care and controlled costs. It did so by creating 16 regional coordinated-care organizations (CCO’s). The state doesn’t pay for each service performed but gives each CCO a “global budget’’ of Medicaid funds to spend. The emphasis is on having a range of providers work with each other to create holistic treatment plans for patients that include the social determinants of health (such as access to transportation and housing quality) as well as patients’ presenting symptoms.

Oregon’s “fee for value’’ approach rewards providers for meeting performance metrics for quality and efficiency and punishes them for poor outcomes and increased costs.

Oregon CCO’s have great flexibility in spending Medicaid money. For example, they could use it to buy patients air conditioners, which may make it less likely that they’ll show up in the E.R. And Oregon CCO’s pay much attention to how behavioral and mental problems can lead to the more obviously physical manifestations of illness. After all, many in our health-care “system’’ “self-medicate’’ through smoking, drinking, drugs, eating unhealthy food and lack of exercise. You see many of these people again and again in the E.R. –wheezing from smoking and obese.

In Rhode Island, 7 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries account for two-thirds of the spending; many of these “frequent fliers’’ have mental and behavioral health problems best addressed through Oregon-style coordinated care.

Unlike the Oregon approach, the “fee for service’’ system that’s still dominant in U.S. health care encourages hospitals and clinicians to order as many expensive procedures as possible, prescribe the most expensive pills and do other things to maximize profit – and send the bills to the taxpayers, the private insurers and the patients.

But “evidence-based medicine’’ -- as opposed to “reputation-based medicine’’’ -- has helped to show that doing more procedures does not necessarily translate into better outcomes; indeed overtreatment can be lethal. I recommend Dr. H. Gilbert Welch’s book “Less Medicine/More Health’’.

Meanwhile, Oregon points the way:

Among the Oregon Medicaid reform’s achievements: a 5.7 percent drop in inpatient costs; a 21 percent drop in E.R. use (which is always very expensive), and an 11.1 percent drop in maternity costs, largely because of hospitals not performing elective early deliveries before 39 weeks of pregnancy. Thus Oregon officials assert that the state can reach its goal of saving $11 billion in Medicaid costs over 10 years.

Rhode Island can achieve similar successes.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), overseer of New England Diary, is a Providence-based editor and writer and a partner in Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com), a national healthcare-sector consultancy. He's also a Fellow of the Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy.

Hospitals must help create new community networks

Health-system markets are being pushed toward a volume vs. value-payment tipping point. This is driven by the confluence of states’ moving Medicaid and state-employee health benefits to value-based (risk) contracts, corporations’ securing national contracts for high-cost care episodes and commercial payers’ creating tiered health insurance. Successful population-health (value-payment) programs, whether fixed-price bundled services for individual patients or comprehensive services for a specific population, as with ACO’s, require action based on these insights:

- Outcomes depend on patients’ behaviors over their lifetimes. Thus, patient and family participation must be increased. Success depends on getting “upstream” of medical-care needs.

- Broad local and regional communities, not individual institutions, can best allocate resources to improve the social determinants of health.

Indeed, improving community health depends more on the interactions among the parts than on individually optimizing the parts themselves. Hospitals and health systems have a time-limited opportunity to help develop community-health networks, the backbone organizations for improving population health.

To get started, leaders of hospitals, public- and private-sector social-service organizations, payers and representatives of the broader community must first frame the discussion from a policy perspective and then map linkages across the community.

Our experience with community health networks underscores the importance of social determinants of health, teamwork within/across collaborating organizations and accepting risk within global budgets. Sustained system thinking across the community’s health assets, shared insights, and much generosity and patience from every sector are critical factors for success and flow from visionary hospital leadership and community/political leaders. Case studies from Oregon and Connecticut, among others, show what can be done.

To get started, leaders would do well to convene a perspective-and-policy-setting discussion to frame context and mutual dependencies. Complex, foundational change is emotionally and organizationally disruptive. Thus establishing a fact-driven and respectful dialogue is an essential first step. We recommend that community leaders, especially hospital leaders, convene a community conversation and use linkage mapping as way to structure the conversation for progress. Based on readiness, one or more work streams would be selected to explore and improve the interactions between the parts.

This is a summary of an Oct. 13 presentation developed by a Cambridge Management Group team led by Marc Pierson, M.D., Annie Merkle and Bob Harrington for the Society for Healthcare Strategy & Market Development's Connections conference. Oregon State Sen. Alan Bates, D.O., provided invaluable information and insights from his work as both a primary-care physician and community/political leader enlisting colleagues in all sectors.