Llewellyn Smith: Hedrick Smith a torchbearer for beaten-down middle class

The middle class has been taking a shellacking for years. It began in the 1970s, when the business and political elites separated from the people and it has been accelerating ever since, according to Hedrick Smith, a former Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter and editor, an Emmy award-winning PBS producer and correspondent, and a bestselling author. In short, an establishment figure.

Add to Smith’s establishment credentials schooling at Choate, the private boarding school, a stint at Oxford, and you have the picture of someone with the credentials to join the elite of his choosing. Instead Smith is a one-man think tank, a persuasive voice against the manipulation of the public institutions, such as Congress, for money and power.

But Smith is not a polemicist. He uses the reporter's tools, honed over decades in Moscow and Washington and on big stories, such as the civil-rights movement and the fall of the Soviet Union, to make his points against the assault on the middle class.

It all began with Smith's looking into what was happening to American manufacturing, which led to his explosive 2012 book, Who Stole the American Dream? Encouraged by the book's success, he created a Web site,reclaimtheamericandream.org, which now has a substantial following. In the past three years, he has lectured at over 50 universities and other platforms on his big issue: the abandonment of the middle class by corporate America and its corrupted political allies.

Smith documents the end of the implicit contract with workers, where they shared in corporate growth and stability. He outlines how money has vanquished the political voice of the middle class.

Instead, according to Smith, corporations have knelt before the false god of “shareholder value.” This has resulted in the flight of corporate headquarters to tax-friendlier climes, jobs to cheap labor, and a managerial elite indifferent to those who built the companies they manage.

In Smith’s well-researched world it is not only the corporations that have abandoned the workers, but the political establishment is also guilty, bowing to lobbyists and fixing elections through redistricting. Two big villains here: money in politics and gerrymandering electoral districts.

The result is a democracy in name only that serves the powerful and perpetuates the power of those who have stolen the system from the voters.

Smith cites the dismal situation in North Carolina, where districts have been drawn ostensibly to ensure black representation in Congress, but also to ensure Republican domination of all the surrounding districts. The two districts that illustrate the mischief are called “the Octopus” and “the Serpent” because of the way they are drawn to identify the voter preference of the inhabitants.

The rise of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump are testament to the broken system, says Smith. They are symbolic of the rising up of the middle class against the predations of the elites.

But Smith is hopeful because, he says, the states have taken up arms against the Washington and Wall Street elites. People should “look at the maps,” he says, “They will be surprised to find out that 25 states are engaged in a battle against partisan gerrymandering, or that 700 cities and communities plus 16 states are on record in favor of rolling back ‘Citizens United’ and restoring the power of Congress to regulate campaign funding.”

Smith sees the middle class reclaiming America: a great social revolution that again unites the government with governed, the creators of wealth with the managers of the wealth. Smith is no Man of La Mancha, tilting at windmills, but a torchbearer for a revolution that is underway and overdue.

“My thought is that more people would be emboldened to engage in grassroots civic action if they could just see what other people have already achieved,” he told me.

Smith’s Web site has drawn 82,000 visitors in the past year, and Facebook posts have reached 2.45 million, he says.

Smith cautioned me to write about the Web site and cause and not the man. But the man is unavoidable, and unique. He has as much energy as he had when I first met him in passing in a corridor at the National Press Club in Washington decades ago. At 82, Smith still plays tennis, skis, hikes, swims and dances with his wife, Susan, whom he describes as a “gorgeous dancer.”

At 6 feet 2 1/2 inches, Smith is an imposing figure at the lectern, but his delivery is gentle and collegiate: a reporter astounded and pleased with what he has found in the course of his investigation of the American body politic.

Llewellyn King is host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He is a long-time publisher, columnist and internationalist business consultant. This piece first ran on Inside Sources.

Llewellyn King: Invasive, relentless coverage has driven good people from politics

Being in public life is now like being on trial day in and day out without knowing what evidence the prosecution has or when it will bring it forward. In fact, being in public life has become God awful and no talented person ought to want to do it.

There is a line of reasoning in political circles which says that Barack Obama created the phenomenon of Donald Trump.

I aver that Donald Trump is a creation of the post-Watergate media. Collectively we have made running for office so absolutely awful, so fraught for families and careers that only two types of office seekers have the fortitude for public life: the grotesques, who are outside of the norms of the political culture, and the shopworn.

Both are on display as we trudge toward November wondering how in a country of so much talent so little of it has been on the ballot in this primary season.

The rot, I submit, began with Watergate when publishers and editors came to believe that the mission of the media was not only to scrutinize the policy views of elected officials but also to rip down the bedroom door, peer into the piggy bank and examine every word in print or on tape that a candidate has uttered since high school, whether in jest or earnest.

We confused personal rectitude -- or rectitude according to the norms of public morality of the day -- with sagacity, statesmanship and talent to lead. In the days before Watergate, Jack Kennedy could do with impunity what got Bill Clinton impeached.

Now that Watergate is 44 years behind us, its legacies are many, but two stand out. The first is that journalists in large numbers were suddenly attracted to covering politics in a way that fewer had been previously. The late Arnaud de Borchgrave, who covered 18 wars, noted disapprovingly that young journalists nowadays aspire to cover politics when they used to aspire to be foreign correspondents.

Even in these days of restrained budgets, Capitol Hill, and to a lesser extent the White House, is flooded with journalists, from the national media to the smallest newsletter. Politics is big news and that is good for business. As the incredibly successful Politico editors like to say, “flood the zone.”

But Congress is a deliberative body and moves slowly, so the news maw is fed with gossip. When the secrets of the budget are not clear or hard to get at, there is always the personal conduct of those working on the budget. If a member of Congress goes out to lunch with someone, anyone, a family member, it will be reported somewhere.

Being in public life is now like being on trial day in and day out without knowing what evidence the prosecution has or when it will bring it forward. In fact, being in public life has become God awful and no talented person ought to want to do it.

No wonder no one holding public office wants to stray from the talking points. A few stray words can bring you down, unless you are so outlandish that you have nothing say but stray words in lieu of coherent ones, like Donald Trump.

Watergate washed away unwritten rules under which what political figures did after hours was not fair game. I once saved a Cabinet member from a situation with two “ladies” who did not have his best interests at stake. Everyone knew why a certain congressman liked to travel to Mexico -- and it was not for tacos. Publicly, it was debated whether the statesman Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan drank too much and no less a person than that public scold, George Will, defended the New York senator by concluding that the great man drank just enough.

Olin “Tiger” Teague, a revered chairman of the House Science Committee, served drinks to his guests at 11 a.m. --and if you wanted an audience, you enjoyed a glass of bourbon with the Texas congressman. Today, you are lucky to get a plastic bottle of water during a Capitol Hill visit.

A Capitol Hill secretary of my acquaintance was proud of the number of congressmen she had bedded, including some in the leadership.

The post-Watergate, unwritten rules of scrutiny, which imply that in private conduct there are clues to public greatness, rather than bringing a new morality to politics, only frightened off the talented, the effective and the patriotic and created a space for the outrageous and the shopworn. Look to Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton and wonder no longer how we got that unappetizing choice to lead the nation.Ll

Llewellyn King (llewellynking2@gmail.com), executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, is also a longtime publisher, editor, columnist and international business consultant. This first ran in InsideSources.

Robert Whitcomb: Mr. Brooks finally discovers that the natives are restless

In an April 29 column by The New York Times’s David Brooks headlined “If Not Trump, What?’’ he writes that to understand Donald Trump’s GOP popularity (and by implication Bernie Sanders’s among Millennials):

“{I]t’s necessary to go out into the pain. I was surprised by Trump’s success because I’ve slipped into a bad pattern, spending large chunks of my life in the bourgeois strata — in professional circles with people with similar status and demographics to my own. It takes an act of will to rip yourself out of that and go where you feel least comfortable….’’

“….Up until now, America’s story has been some version of the rags-to-riches story, the lone individual who rises from the bottom through pluck and work. But that story isn’t working for people anymore, especially for people who think the system is rigged.’’

How little effort much of the elite have made to know the plus-90 percent of the nation who aren’t. You’d think that big-time journalists would try to talk more to “everyday Americans,’ at least for show. But media celebs such as Mr. Brooks are addicted to the money, privilege and ego-gratification that go with spending most of their time with the rich and/or powerful. Meanwhile, many business/economics journalists have been fired to help maintain media outlets’ profit margins. So rigorous, data-driven coverage of socio-economic changes has declined in the media that American most look at in favor of, well, nonstop coverage of Mr. Trump’s latest insults. (I’m a former business editor.)

Mr. Brooks, et al., now seem to fear that massive social unrest is coming unless members ofthe “middle class’’ think that they will get a better deal. (Of course, many low- and middle-income people could help their situations by, for example, avoiding having kids out of wedlock and other disorderly behavior linked to poverty. They could also vote.)

The nub of the problem:

Government data show that American economic productivity in 1945 -1973 rose 96 percent and inflation-adjusted pay 94 percent; in 1973-2014 productivity grew 72.2 percent and inflation-adjusted pay 9.2 percent, with almost all of the growth in 1995-2002.

This suggests that the folks owning and/or running companies have become much less willing to share. At the same time, tax laws remain very skewed in favor of investment income over earned income. This keeps reinforcing a plutocracy based on inherited capital and privilege. The Sunday New York Times weddings section displays this crowd in all its glory.

Meanwhile, the elite’s disinclination to share has slowed economic growth by constraining most Americans’ purchasing power.

The very rich have increasingly sequestered themselves from the poor and the middle class through, among other things, jet travel, globalization, the Internet and gated communities. Thus they’re less likely to see and be embarrassed by extreme divergences of wealth. Ever more large local enterprises are owned by far-away companies and/or individuals rather than by people in the communities where the companies operate. The local employees are mere numbers on a screen rather than people whom senior executives and major shareholders might awkwardly encounter on the street.

In some of the burgs where my family have lived over the past century, such as Brockton, Mass., when it was a shoe-making capital, and Duluth, Minn., an iron-ore and grain shipping port, my relatives who were executives, factory managers and the like would encounter a wide range of the population daily, from rich to poor. Now, the descendants of these folks who have not yet drunk away the old money made in these places tend to spend six months and a day enjoying tax avoidance in Florida , and those who own and/or run largeenterprises with operations in places like Duluth and Brockton may never visit them at all.

Out of sight, out of mind.

But now there’s the glint of pitchforks in the sun. It’s too bad that the leading spokesmen for the new “populism’’ are con man Donald Trump (see: www.trumpthemovie.com) and a naïf like Bernie Sanders, who doesn’t understand the need to always encourage entrepreneurialism to raise living standards. As for the Clintons, all too often they act like establishment grifters.

Anyway, we need capitalism, but adjustments are long overdue.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), a former Providence Journal editorial page editor, a former International Herald Tribune finance editor and a former Wall Street Journal editor, oversees New England Diary and is a partner at Cambridge Management Group and president of Guard Dog Media, based in Boston.

Chris Powell: A desperate America needs you to sign a petition for a big new political party.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

How has this happened? How have the two major political parties contrived to give their presidential nominations to candidates who, according to opinion polls, are both heartily disapproved by a majority of voters generally even as they command majority support in their own parties?

Must the next president be a megalomaniac and serially bankrupt buffoon leading a pack of hateful brownshirts, or a clumsily pandering, posturing grifter leading a pack of parasites?

No presidential election in modern times has offered as much opportunity for a third-party challenge. John Anderson took almost 7 percent of the vote in 1980 and Ross Perot almost 20 percent of the vote in 1992 against candidates whom the public did not find half as repulsive as Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

Is there no one in public life in this country whose approval rating exceeds his or her disapproval rating — no one who, while perhaps little known at the moment, might earn the country’s respect rather than its contempt in a few months?

Of course since elections are usually exercises in building consensus, campaigns can be a slog toward mediocrity. Disappointed with the result of the 1924 presidential election, the social critic H.L. Mencken renounced democracy itself.

“Democracy,” Mencken wrote, “is that system of government under which the people, having 35,717,342 native-born adult white men to choose from, including many who are handsome and thousands who are wise, pick out a Coolidge to be head of the state. It is as if a hungry man, set before a banquet prepared by master cooks and covering a table an acre in area, should turn his back upon the feast and stay his stomach by catching and eating flies.”

And Coolidge didn’t turn out so badly, as Mencken had to admit when he wrote the former president’s obituary in 1933: “He had no ideas and he was not a nuisance.”

But Donald Trump in charge of the nuclear arsenal? Hillary Clinton —futures trader extraordinaire, tool of Goldman Sachs, destroyer of universal medical insurance, dissembler of Benghazi, compromiser of classified documents — in charge of anything?

Now will someone please start circulating the petitions?

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Chris Powell: Don't blame the NRA or Yale

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut saw four of the five remaining presidential candidates on the eve of its primary election.

On the Republican side, Donald Trump, having admitted that he doesn’t want to seem "presidential," went to Bridgeport and Waterbury to revel in the buffoonery, mockery and contempt that have made him so appealing to so many. In Glastonbury, Ohio Gov. John Kasich easily contrasted himself as thoughtful and respectful.

On the Democratic side, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders complained to a rally in New Haven that 36 percent of that city's children are not just living in poverty but doing so within sight of Yale University's $26 billion endowment, as if there was some connection.

Hillary Clinton visited Hartford, emphasized the problem of gun violence, and pledged to confront the National Rifle Association and strive to "change the gun culture."

But repugnant as the NRA may be, it has little to do with gun violence, and the"gun culture" Clinton deplored -- presumably the NRA’s 5 million purported members -- is not the culture doing the most damage with guns.

Rather, the "gun culture" that does the most damage is the culture of poverty, unconditional welfare, drug dealing and drug prohibition. Most shootings -- from Hartford to Chicago to Los Angeles -- are not committed by NRA members but by fatherless and uneducated young men, products of the family-destroying welfare system who see drug dealing and crime as their best career options. Sanders’s silly linking of child poverty in New Haven with Yale’s endowment only emphasizes the difficulty of pushing the political left out of its ideological dead end.

Since Yale is such an awful influence, the expropriation of its endowment and the resulting smashing of its political influence under the assault of Sanders’s socialism would be positive. But all Yale’s money could be spent in the name of alleviating poverty and, if it was spent as the hundreds of billions of dollars before it have been spent, there would be only more poverty and dependence afterward.

Amid this half century of policy failure it is hard not to suspect that poverty and dependence are actually the objectives of the political left generally and the Democratic Party particularly. For poverty and dependence fuel the need for government patronage and become not afflictions to be eliminated but profitable businesses and ends in themselves.

A few decades ago it was possible for a few on the left and a few Democrats to acknowledge this failure of policy, as the sociologist Daniel Patrick Moynihan did before becoming one of Clinton’s predecessors as a Democratic senator from New York.

Moynihan wrote in 1965: "From the wild Irish slums of the 19th-century Eastern seaboard to the riot-torn suburbs of Los Angeles, there is one unmistakable lesson in American history: A community that allows a large number of men to grow up in broken families, dominated by women, never acquiring any stable relationship to male authority, never acquiring any set of rational expectations about the future -- that community asks for and gets chaos. Crime, violence, unrest, disorder -- particularly the furious, unrestrained lashing out at the whole social structure -- that is not only to be expected; it is very near to inevitable. And it is richly deserved."

In the Senate 20 years later, Moynihan elaborated: "The institution of the family is decisive in determining not only if a person has the capacity to love another individual but in the larger social sense whether he is capable of loving his fellow men collectively. The whole of society rests on this foundation for stability, understanding, and social peace."

To end poverty and gun violence, government needs first of all to stop manufacturing them.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

David Warsh: Hillary Clinton the Hawk

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

Victory in the New York State primary seems to have all but clinched the Democratic nomination for Hillary Clinton. I won’t be surprised if this week’s quintet of Northeast primaries puts Donald Trump so close to the top as to diminish the suspense surrounding the Republican convention.

So it is an auspicious time for Alter Egos: Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and the Twilight Struggle over American Power (Random House, 2016), by Mark Landler, to appear. The magazine of The New York Times published a scoop on April 24, under the headline, “How Hillary became a hawk.” The story says:

"Throughout her career she has displayed instincts on foreign policy that are more aggressive than those of President Obama — and most Democrats.''

The article, at least, reads like a campaign document, consisting mainly of vignettes that have been fed to the journalist: Clinton pivoting towards the center in preparation for the general election. “We’ve got to run it up the gut,” she exclaims to her aides after China warns against sending an aircraft carrier into the Yellow Sea to protest North Korean actions.

When visiting Fort Drum, in upstate New York, for the first time as a newly elected senator, she sits down, takes off her shoes, puts her feet on the coffee table, and asks, “General, do you know where a gal can get a cold beer around here?”

She reads “cover to cover” the counterinsurgency field manual General David Petraeus has given her

She befriends and receives the (qualified) endorsement of retired four-star Gen. John M. “Jack” Keane, Fox news military analyst and promoter of the Iraq “surge.”

And when reporter Landler surfaces a striking disagreement with former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Karl Eikenberry (and for two years previously U.S. commander there), a Clinton aide volunteers, “She likes the nail-eaters, [Stanley] McChrystal, Petraeus, Keane – real military guys, not these retired three-stars who go into civilian jobs.”

Landler writes:

"As Hillary Clinton makes another run for president, it can be tempting to view her hard-edged rhetoric about the world less as deeply felt core principle than as calculated political maneuver. But Clinton’s foreign-policy instincts are bred in the bone — grounded in cold realism about human nature and what one aide calls “a textbook view of American exceptionalism.” It set her apart from her rival-turned-boss, Barack Obama, who avoided military entanglements and tried to reconcile Americans to a world in which the United States was no longer the undisputed hegemon. And it will likely set her apart from the Republican candidate she meets in the general election. For all their bluster about bombing the Islamic State into oblivion, neither Donald J. Trump nor Senator Ted Cruz of Texas have demonstrated anywhere near the appetite for military engagement abroad that Clinton has.''

The book itself will be useful in the event Clinton becomes president, as seems increasingly likely. Whether she is a neo-con or liberal hawk or a conservative internationalist is an open question. In the interval, however, better to read America’s War for the Greater Middle East: a Military History (Random House, 2016), by Andrew Bacevich, a scathing assessment of US military policy since 1980.

David Warsh is a long-time financial journalist and economic historian. He the proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this piece originated.

Robert Whitcomb: The gig economy

I’m old and lucky enough that most of my working life took place when large U.S. enterprises usually made long-term commitments, albeit often rather vague, to their competent workers. If a recession hit, senior executives would grit their teeth and try to hang on to their employees. Back when I was a business editor at The Wall Street Journal, the International Herald Tribune and elsewhere, Fortune 500 senior executives’ commitment to their fellow employees often impressed me. Not much anymore!

There was something like two-way loyalty, and the top people often showed a certain sensitivity about public perceptions of their compensation.

Now the idea is to maximize short-term profit and stock price and thus senior execs’ and board members’ compensation above all else. I have seen that in some sectors where managements that used to be satisfied with 15 percent profit margins raised them to over 30 percent. And CEOs now make on average over 300 times the average pay of their employees, compared to 20 times in 1965!

Thus many companies refuse to spend money on long-term investments, such as employee training: While such outlays strengthen companies in the long haul, they cut into short-term net income. So train yourself – you may well be laid off next month anyway.

Then there’s the rise of the “gig economy,’’ in which “on-call’’ workers, “permatemp workers,’’ “independent contractors’’ and people employed by such contract firms as Manpower comprise an ever larger share of the workforce.

The Wall Street Journal reports that these days 17 percent of women and 15 percent of men have such “alternative employment.’’ Such jobs are up by more than half from 2005. (See ‘’’Gig’ Economy Spreads Broadly,’’ WSJ March 26-27).

These positions, with their very unpredictable hours, pay lower wages than regular jobs and offer few if any fringe benefits. They are spreading rapidly across more sectors, such as law and healthcare, pulled by computerization and globalization. They have long been particularly common in higher education, which depends on low-paid adjunct teachers to offset the cost of almost-impossible-to-fire tenured professors, with their high salaries and big benefits.

Employers obviously need flexibility to adjust their staffing levels. But when they reduce the ranks of their full-time employees beyond a certain point to keep short-term profit margins and senior executive pay sky high, they risk undermining the viability of their enterprises by destroying the institutional memory and employee morale and loyalty needed formost enterprises’ long-term success.

Short-termism usually triumphs. CEOs don’t expect to have their jobs very long; thus they want to accelerate their compensation.

Meanwhile, the economy as a whole tends to stay in a low-growth pattern as the purchasing power of most people shrinks and national wealth is increasingly concentrated in a tiny group whose members can perpetuate their (and their children’s) power with the aid of cash (and later, lobbying and other jobs) for politicians in return for favorable policies.

We’ll see a revival of private-sector unionization as more workers see that as the only way to obtain a modicum of economic security. We’ll also see an increasing number of economically insecure Americans following the siren song of such con men as Donald Trump and such presumably sincere but wrong-headed reformers as Bernie Sanders who don’t understand the need to encourage the “animal spirits’’ of entrepreneurism; Mr. Sanders has never had a job in business. There are reasonably centrist policies that can make things better, such as adjustments in the tax code and labor regulations.

None of this is to say that “contingent’’ and/or freelance employment can’t work well for some people. I myself have enjoyed some of its flexibility as a partner in a couple of small businesses. But you can’t build a strong economy on it.

xxx

Post-Brussels, President Obama and some other sensitive souls continue to avoid saying “Islamic’’ before “terrorism’’. They’re being intellectually dishonest. Islam (mostly its Sunni side) has big problems, the worst being that too many of its emotionally needyfollowers adhere to the 7th Century barbarism and supremacism in some of its scripture. Islam needs a reformation.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is a Providence-based editor and writer and overseer of this site.

David Warsh: Of Ross Perot, Donald Trump and 'the China shock'

Donald Trump’s hostile takeover of the Republican Party is nearly complete. I was as slow as the next guy to see in coming. But now that the fox is almost in charge of the chicken coop. I have some ideas about why it happened, and why just now.

Let’s go back to the last time a billionaire decided to run for president. That was 1992, when software entrepreneur H. Ross Perot ran as an independent candidate. I was able to refresh my memory thanks mainly to a useful conference volume, Ross for Boss: The Perot Phenomenon and Beyond (SUNY Press, 2001), edited by Ted G. Jelen, of the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. This comparison last September by John Dickerson of Slate was prescient.

Perot was born in Texarkana, Texas, in 1930, the son of a cotton broker. An Eagle Scout, an Annapolis graduate, a star salesman for five years for IBM Corp., he quit in 1962 to found a software firm, Electronic Data Systems. In 1984 he sold the company to General Motors Corp., its principal client, for $2.4 billion. Four years later he and his son started a second firm, Perot Systems Corp. They sold it to Dell Inc., in 2009, for $3.9 billion

During the 1980s Perot became absorbed in POW/MIA issues in Vietnam. By the early ’90s, he had become involved in many of the larger controversies of the day. During 1991, he appeared regularly on popular television talk shows, criticizing presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush for having failed to balance the federal budget. He portrayed Washington as being in the grip of lobbyists, many of them working for foreign interests. He criticized trade agreements. He denied having presidential ambitions.

In February 1992, Perot appeared on Larry King Live to encourage citizens to nominate him by petition in 50 states as presidential candidate of the Reform Party. He proclaimed his lack of political experience as an asset. He promised to spend as much as $100 million of his own money – more than either party could expect to raise in those days well before the Supreme Court struck down spending limitations – and argued that meant he couldn’t be bought. By June, he was running even with Bush and Bill Clinton in most polls.

That same month he got in an argument with two high-profile political consultants who urged him to immediately launch an expensive advertising campaign, and, when one of them resigned, Perot asserted that he, too, would withdraw, explaining that he felt that he had revitalized the Democratic Party by threatening to enter the contest. A barrage of negative publicity followed. Perot was ridiculed as eccentric and judged to be a quitter.

In late September Perot returned to the race, “for the good of the country,” in time for three televised debates among the candidates in October. This time he emphasized opposition to the pending North American Free Trade Agreement, and warned of the “giant sucking sound” accompanying jobs lost overseas. He spent nearly $50 million in a month on “infomercial” advertising, much of it in states that he had no hope winning.

Perot received 19 percent of the popular vote in the November election, but failed to win a single state and received not a single vote in the Electoral College. Clinton slipped past Bush with 43 percent of the popular vote. Martin Nolan, chief political correspondent for The Boston Globe for 30 years, remembers, “Perot did not defeat GHWB electorally, but more by draining attention. He made the incumbent president a ‘low-energy’ candidate.”

Four years later Perot was back, this time as the official nominee of his Reform Party. This time he polled fewer than half as many votes. He left politics and returned to the relative obscurity of the business world.

Perot’s role in galvanizing support for budget-balancing measures is still hotly debated. The Clinton administration, the Federal Reserve, Congress and the Federal Communications Commission all played a part (the FCC by facilitating the rapid build-out of communications technology and the Internet).

In any case, by the end of the ’90s, the federal budget was balanced. Perot’s criticism of trade-liberalization measures found little traction, though. The North American Free Trade Agreement became law in 1994, and the following year the World Trade Organization replaced the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Perot’s greatest influence was probably that described by his running-mate in 1992, Adm. James Stockdale: “Ross showed you don’t have to talk to [ABC’s] Sam Donaldson to get on television…. American candidates can now bypass the filters and go directly to the American, people.” Subsequent independent presidential candidates have included Pat Buchanan and Ralph Nader.

Fast forward to 2016 and Donald Trump. Much has changed since 1992.

Exhibit A is an important new essay by a trio of labor economists, arguing that trade theorists didn’t well understand what was happening in the world these last 35 years – particularly the last 10. Read “The China Shock,’’ by David Autor (of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), David Dorn (of the University of Zurich), and Gordon Hanson (of the University of California at San Diego) is headed for the authoritative Annual Review of Economics. They argue that theorists failed to anticipate how extensive dislocations would be, especially in the U.S.:

“Just as the economics profession was reaching consensus on the consequences of trade for wages and employment [that they would be modest], an epochal shift in patterns of world trade was gaining momentum. China, for centuries an economic laggard, was finally reemerging as a great power, and toppling established patterns of trade accordingly. The advance of China…has also toppled much of the received empirical wisdom about the impact of trade on labor markets. The consensus that trade could be strongly redistributive in theory but was relatively benign in practice has not stood up well to these new developments.’’

Talk about an inconvenient truth! Is Donald Trump right? Were we fools to liberalize so quickly? I don’t think so. The short-term and medium-run costs are clearly greater than had been expected: Poorer cities are remarkably slow to adjust, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed, and unemployment rates high, for a decade and more.

But is the world a better, safer place than when it was divided into market economies, communist nations, and Third World growing ever-so-slowly, if at all? Steven Radelet, of Georgetown University, makes the case in The Great Surge, the Ascent of the Developing World (Simon and Schuster, 2015). In Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (Harvard/Belknap Press, 2016), Branko Milanovic, for many years lead economist at the World Bank, describes the stresses.

In any event, it appears that most of the hectic global transition is over. Today it is China that is contemplating layoffs. The greatest gains from trade almost certainly lie ahead – but for whom?

Meanwhile, Peggy Noonan, the former Reagan/George H.W. Bush speechwriter who for many years has been an influential columnist for The Wall Street Journal, describes the new contest as between the “protected” and the “unprotected.” She recently told Karen Tumulty, of The Washington Post, “We are witnessing history. Something important is ending.”

What has already ended, I think, were the 50 wonderful years after 1945 in which the United States, having emerged less scathed from World War II, was more or less unchallenged as the world’s only economic superpower – a long splendid day in which the eight years of the Reagan administration constituted the late afternoon.

How might Trump do with issues like these in the general election? Again, Marty Nolan: “In ’92, Perot prospered in cold, remote country: Maine, Minnesota, Alaska. He was zip in the late Confederacy.” If you look at the maps of exposure to industrial competition in “The China Shock,’’ it’s the Midwest and the Southeast where the trade shocks have hit hardest. Slim chance that Trump would, like Perot, go away with a goose-egg, if he is the nominee.

That said, I fully expect Hillary Clinton to win in November. She has the right language to succeed: The task now is to fill in what has been hollowed out. If Trump is its candidate, the trick for the GOP to learn as much as possible from this election to shed the heavy burden of ideology that Trump has lampooned, to abandon the absolutism of recent years in favor of practical compromise – either that or fade into history.

So it seems possible, even likely, that Trump’s campaign will prove helpful to straightening things out between the parties. I think Paul Krugman got it exactly right when he wrote the other day: “We should actually welcome Trump’s ascent. Yes, he’s a con-man, but he’s also effectively acting as a whistle-blower on other people’s cons. That is, believe it or not, a step forward in these weird, troubled times.”

To which I can only add, yes, that’s so, as long as Trump is defeated soundly enough to discourage a third such billionaire in the future, one who might be smarter than the first two.

David Warsh, a longtime financial journalist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

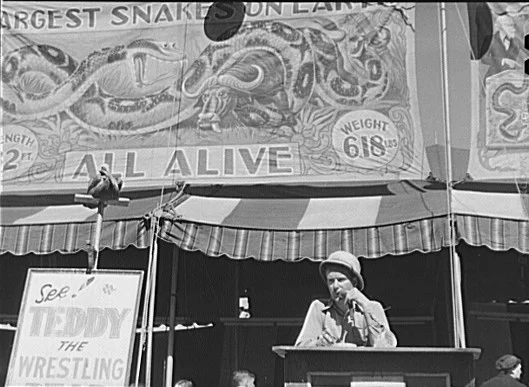

Will they still love him anyway?

Barker at the 1941 Vermont State Fair.

--- Photo by Jack Delano

Fox News, the broadcast wing of the Republican Party, last night applied its fact-checking skills to Donald Trump’s often absurd, contradictory, chaotic and fact-free “policy’’ prescriptions, while mostly giving Ted Cruz and the man whom Mr. Trump calls “Little Marco’’ Rubio a pass. The GOP establishment is terrified that the real estate developer/operator and “reality TV’’ star will win the nomination and drag the party into an historic defeat in the fall. Yes, he would.

Of course, Messrs. Cruz and Rubio’s allegiance to the truth has also sometimes been erratic, and they too are not averse to demagoguery, but Donald Trump is in another league. His career has been one con after another.

See: www.trumpthemovie.com

A question is whether Mr. Trump’s followers and potential followers see the way the debate was run -- to bring him down -- as unfair pilling on, leading Trumpists to double-down on their support of the carnival barker.

Unfortunately for their credibility, and even morality, all three non-Trump candidates on the stage said that they'd support the New Yorker if he wins the nomination. How could they in good conscience endorse someone Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio (John Kasich was milder) called dangerous, corrupt and otherwise immoral? They have been gentler even to Hillary Clinton.

Meanwhile, the amiable John Kasich took credit last night, as do other national politicians active in the ‘90s, for the prosperity and federal budget surpluses of the late ‘90s.

In fact, those happy things resulted from the money freed up by “peace dividend’’ from the end of the Cold War, an income-tax increase accepted bravely by President George H.W. Bush and the explosion in computer/Internet business, especially after Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, in 1989. The last brought in tons of tax revenue and gave new high-paying jobs to many people, albeit mostly the well-educated.

Mr. Kasich had nothing to do with any of that. But he seems to be a nice man and a competent governor of Ohio, though I would have preferred to see the brilliant and innovative former governor of Indiana, and now president of Purdue University, Mitch Daniels on the stage instead.

-- Robert Whitcomb

Llewellyn King: America's great gale of 2016

If you accept that seminal means an event or moment after which things will never be the same again, then we are living through a seminal year.

In matters big and small, change is in the wind.

This wind has been blowing through presidential primary and caucus states and is defining the 2016 presidential election. Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are not so much the leaders of this time of change, but rather the products.

The product is something hard to pin down, but it is there nonetheless — a sense that it is time to turn the page, to read the next chapter; a yearning for something fresh.

The Millennials, hunched over their cell phones, are looking for the future in their small screens. The rest of us are looking for it in new leaders, new lifestyles; and new thinking, sometimes about old ideas.

Societies go through periods when they feel the need to change up things. But they want a sped-up evolution rather than a full-fledged revolution. This is such a time.

Change is everywhere from the bold, new things television is doing — frontal nudity, gay coupling and interracial love — to the kind of car we favor.

While we grapple with change and yearn for the new, we are surprisingly open-minded. American values appear to be undergoing a recalibration: We are getting more socially tolerant. Social conservatives are a diminished force.

Young people do not have the same commitment that their parents had to conventional employment, to be defined by where they work. This leads to a world where people are less concerned with appearances, and all that goes with appearances. The business suit and its essential accoutrement, the necktie, are on the way out – and in much of the country, they are now curiously out of date. Apartments are being favored over houses because of new social values.

My generation experienced the hopeful 1940s (just the tail end), the smug 1950s, the turbulent 1960s, the oil-shocked 1970s, and the computer-excited 1980s, which continued unabated until the dot-com bubble burst at the turn of the century – but re-inflated with new developments in Internet products like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

In recent times, the only new American billionaire outside of the Internet was Hamdi Ulukaya, who popularized Greek yogurt in country hungry for yogurt choices. That is a dumbfounding fact. It means that it will be harder to get investment in old-line businesses and start-ups. The smart money has become myopically obsessed with the cyberworld.

If you were to go to Wall Street today to raise money for a new nuclear reactor that put all doubts of the past to rest and offered income for 100 years — there are such machines on the drawing board – you would find it hard to raise money; easier for a new Internet messaging system. This when there is no shortage of Internet messages (too many, I cry each morning). We are leery of the hard and enamored of the soft.

We sense that the education system is not doing its job; that it is broken and needs fixing. But how, we are not sure. We are sure, though, that we are going to change it.

We sense that we had the dynamic wrong in foreign affairs; that change at home, like toppling a generation of political leadership, is desirable, while toppling leaders abroad is a fraught undertaking, as with Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi and Bashar al-Assad.

We feel less good about the wealthy, and we are less sure that there are secure places for us in the future. We watch cooking shows and order in pizza. We gave up smoking and started jogging. But we are, so to speak, deaf to the damage we are doing to our ears with incessant music piped to them by earbuds.

We are more nationalistic and less confident at the same time. We treasure our values more, and wonder about their long-term durability.

The largest contradiction that can easily be inspected is in the themes of Trump and Sanders: Trump has rehabilitated a kind of racism aimed at immigrants, while Sanders has made the taboo word “socialism” acceptable in political dialogue.

The desire for change has moved from a slight wish to a hard desire for a new alignment. It is everywhere, from what we eat to how we feel about the climate. But we do not agree on this new alignment, hence the huge gulf between Sanders followers and Trump adherents.

Llewellyn King is a long-time publisher, international business consultant and columnist (and friend of the overseer of New England Diary). This piece first ran inInsideSources.

David Warsh: Trying to make sense of America's age of disaggregation

"I am as eager as the next guy to make sense of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, but I do not expect to work my way through to useful opinions by following the primary and caucus returns."

Seeking distance from the dispiriting political news, I spent the best hours of last week reading various chapters of four books by Princeton historian Daniel T. Rodgers. I am as eager as the next guy to make sense of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, but I do not expect to work my way through to useful opinions by following the primary and caucus returns. So I turned to the work of a scholar who has spent his career writing about the evolution of the political culture of modern capitalism in the U.S. over the last 150 years.

I first read Rodgers a few years ago after an old friend recommended Age of Fracture, which had won a Bancroft Prize in 2012. I was struck by how attentive the historian had been to various developments in economics in the 1960s and ’70s I knew something about: the influence of deregulators such as Ronald Coase and Alfred Kahn, macroeconomists Milton Friedman and Robert Lucas, lowbrow supply-siders, highbrow game theorists, legal educator Henry Manne.

I know much less about the other realms Rodgers reconnoitered in the book in order to elaborate his central metaphor – international relations, class, race, gender, community, narrative. But I know that his fundamental diagnosis rings true. Life today is more specialized, more highly differentiated, and, yes, somehow thinner than in the past.

"Conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones… Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind the last quarter of the century, was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.''

Over the next year I skimmed Rodgers’s three previous books. They turned out to offer a fairly seamless narrative of, not so much economic history, but arguments about economic history, over the course of a century and half. Rodgers was born in 1942, graduated from Brown University in 1965 and got his Ph.D. from Yale in 1973, taught at the University of Wisconsin until 1980, when he moved to Princeton University, where today he is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History, emeritus

That first book, The Work Ethic in Industrial America: 1850-1920, traced American attitudes towards work, leisure and success, from relatively small-scale workshops before the Civil War to highly mechanized factories at the beginning of the industrial age. The second, Contested Truths: Keywords in American Politics since Independence, identified a handful of ostensibly technical terms – “utility,” “natural rights,” “the people,” “government,” “the state,” and “interests” – and examined their use in arguments, especially as the confident tradition he describes as “liberal” gave way to a rediscovery, both academic and popular, of “republicanism” in the Reagan years.

The third work, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age, is a highly original reconstruction of various ways “progressivism” was understood in the first half of the twentieth century, in Europe and the United States: corporate rationalization, city planning, public housing, worker safety, social insurance, municipal utilities, cooperative farming, wartime solidarity, and emergency improvisation in the Great Depression. (A research assistant was Joshua Micah Marshall, who went on to found the influential online news site Talking Points Memo.)

Age of Fracture is the fourth.

It’s a rich vein. I plan to mine all four over the next few months, making a Sunday item, when and if I can. One needs something to discipline mood swings during the rest of the campaign, and I’ve decided that, for me, this is it.

Today I’ll offer a small but concrete example of what Rodgers calls “ideas in motion across an age,” or, in this case, many ages. American exceptionalism is a persistent theme with him: the free-floating idea that, as “the first new nation” and “the last best hope of democracy,” the United States has a mission to transform the world and little to learn from the rest of it. Is that the note that Trump so single-mindedly and simple-mindedly strikes when he promises to “make American great again”? It helps me to think so.

As for Rodgers, he is spending the year in California, writing a fifth book, a “biography” of a 1630 text that would come in time to be seen as central to the nation’s self-conception — the John Winthrop sermon that contains the famous phrase, “[W]e shall be as a city on a hill.”

David Warsh, a veteran economic historian and financial journalist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this originated.

Voters hiding from the world

The insularity of that minority (i.e., “the base’’) of the electorate that tends to dominate presidential campaigns’ first innings explains much of the current nasty race, especially on the Republican side.

These people seek to protect themselves from the anxiety of hearing a viewpoint they might not like by holing up in echo chambers in which the same fact-thin opinions are repeatedly shouted day after day. The epicenter is the oratorical masturbation known as political talk radio.

You’d think that listeners would get bored and occasionally want to hear something different, but that would make them uncomfortable. Talk radio does not encourage curiosity or research. The point is to soothe listeners by reinforcing their well-entrenched prejudices and satisfy their desirefor simple solutions to their problems – and clear villains.

The majority of talk-radio fans are middle- and lower-middle class white people aggrieved by their downward socio-economic mobility and upset about changing social mores as seen, for example, in gay marriage, and the changing ethnic and religious mix of America. That’s understandable.

But their refusal to listen to all sides in order to become better informed citizens also suggests a disinclination to make the changes, be it training for new work skills or bringing disorderly personal lives under control, necessary to address these tougher times for many Americans. Too many of them are both angry and passive.

That makes them prey to such demagogues as Donald Trump and Ted Cruz. Mr. Trump may be an especially fitting candidate for our times: People who avoid reading and obtain most of their “news’’ from TV and talk radio like him the most.

No wonder (relatively) scandal-free people of great executive and policymaking accomplishment who would have been very plausible presidential candidates in the past – say former New York Republican Gov. George Pataki and former Democratic Sen. Jim Webb -- don’t have a prayer. And such competent chief executives as Ohio Gov. John Kasich, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley haven’t gotten much traction either.

And it’s hard to see Hillary Clinton, despite her long CV, intelligence, ambition and persistence, as a person of great executive and policymaking success. Bernie Sanders, for his part, is an eccentric fringe high-tax candidate in a nation whose citizens hate taxes. His only executive experience has been as mayor of Burlington, Vt.: pop: 42,000.

(A possible spanner in the works of a Hillary Clinton marchto theDemocratic nomination: indictment stemming from her “top-secret’’ home-server e-mails.)

You’d think that voters would want the nation’s chief executive to be or have been a successful elected executive of a government body. And no, running a business is not the same as running a government body.

Globalization and technology, both of which will continue to eat away at the American middle class, require a panorama of responses, including reducing our plutocracy’s ever-increasing power, more job training and rebuilding the nation’s decayed physical infrastructure to create jobs and make the nation more internationally competitive.

Cheapening labor and technology-based automation, which so far have mostly destroyed the jobs of blue-color workers, are now eating away even at what had been well-paying upper-middle-class jobs. Andsenior business execs show little desire to share more of their gargantuan compensation with underlings.

The candidates generally avoid presenting and emphasizing programmatic details because details don’t do well on TV and talk radio. And so many journalists have been laid off that the surviving ones almost entirely focus on the easiest and more marketable stuff in the campaigns - - the daily insults, faux pas and hour-by-hour opinion polls -– the horse race.

Apparently that’s fine with the people who hide in the silos of talk radio.

Once the candidates of the two major parties are chosen, perhaps more substance will appear as the candidates reach for support from moderate and independent voters. We can hope they’ll then explain with considerabledetail and precision what they’d do and, as important, how they’d do it.

Meanwhile, most of the electorate, the large majority of whom only bother to vote in November, can look into the mirror to see who is most to blame for our predicament.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail) oversees newenglanddiary.com, is a partner at Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com), a former Providence Journal editorial-page editor and a former International Herald Tribune finance editor,

David Warsh: Kasich's time may have come

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Readers have wondered when I might back off the hunch I voiced a year ago, and reiterated as recently as December, that Jeb Bush still could eventually win the presidency. Here goes:

Bush clearly no longer has a chance of winning the nomination. It is Ohio Gov. John Kasich who appears ready to seize the role of a plausible competitor to the eventual Democratic nominee. There appears to be almost no political difference between the two men, except the heavy baggage connected with the former’s name. Kasich is running second to Donald Trump in New Hampshire in the polls.

Nobody said it would be easy, but the logic of Kasich’s candidacy is simple: If he polls strongly on Feb. 9 in New Hampshire; if he gains enough traction in February to score some successes in the Super Tuesday primaries on March 1; if he wins Ohio’s winner-take-all primary on March 15; if he gains the nomination of the Republican Party at its convention in Cleveland in July – then he stands a good chance of being elected president in November.

Why? Because he is good at appealing to voters who consider themselves independent of either party’s establishment. And it takes 270 votes in the Electoral College to win the presidency. And it’s a stubborn fact of present-day U.S. politics that most states are virtually certain to wind up in one column or another.

Kasich would seem to be competitive with the Democratic nominee, whether it is Hillary Clinton or someone else, in all 10 states that seem likely to be up for grabs in the fall – Nevada, Colorado, Iowa, Wisconsin, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, Florida and New Hampshire.

I have been as surprised as everybody else by events of the last year. Let’s review:

It was barely a year ago that Mitt Romney announced that he was mulling a third presidential bid. The establishment wing of the Republican Party swiftly overruled him, indicating a preference for Jeb Bush, who in December 2014 had mentioned on his Facebook page that he was considering a run. Supposedly preemptive sums of money flowed to Bush’ s Super PAC, Right to Rise, run by political consultant Mike Murphy. Romney quickly steered off.

What happened next was that, unfazed, 15 other persons declared their candidacy for the Republican nomination, one after another, along with Bush: Ted Cruz (March 23), Rand Paul (April 7), Marco Rubio (April 13), Ben Carson (May 4), Carly Fiorina (May 4), Mike Huckabee (May 5), Rick Santorum (May 27), George Pataki (May 28), Lindsey Graham (June 1), Rick Perry (June 4), Bush (June 15), Donald Trump (June 16), Bobbie Jindal (June 24), Chris Christie (June 30), Kasich (July 21), and Jim Gilmore (July 30).

Among the Democrats, Hillary Clinton declared her candidacy on April 13, Bernie Sanders on April 20, former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley on May 29, and former Rhode Island Gov. Lincoln Chafee on June 3. Sanders has recently swept ahead of Clinton in polls in both Iowa and New Hampshire.

Why such pandemonium? The over-arching explanation seems to be Bush-Clinton fatigue after so many years of their presence in presidential politics.

Without a single vote being cast, real-estate baron and reality-television star Trump vaulted to front-runner status in most polls of Republican voters. It’s getting a little late to explain U.S. outcomes in terms of the aftermath of the 2007-09 financial crisis; Europe is another matter: most likely the Trump phenomenon is an expression of ephemeral contempt for dynastic politics.

Trump is not the first self-financed celebrity candidate to seek the presidency. He’s just the one with the fewest principles. Software entrepreneur H. Ross Perot ran as an independent candidate in 1992, upstaging incumbent George H. W. Bush and enabling Bill Clinton to win the presidency with just 43 percent of the vote (Perot received 19 percent and Bush 37 percent, but electoral vote totals were 370, 168, and 0.)

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg is threatening to enter the race as an independent if Sanders gets the better of Hillary. An interesting questions have to do with Trump’s options once his star begins to fade. Eventually he presumably will become a commentator. Better for everyone if it were sooner rather than later.

Bush could do everyone a favor by quickly stepping out of the campaign if his New Hampshire totals are disappointing and urging his massive organization to support Kasich. As far as I can tell, his politics are little different from those of the Ohio governor, except on foreign policy. Still, Bush would make a very good secretary of state in a Kasich administration. The silly negative ads with which the two campaigns are attacking one another in the final days of New Hampshire should stop.

I have no idea how likely any of this might be. I do know an incredibly interesting political season looms. There is a real possibility that the election of a moderate Republican would be good for the country, mainly for the obvious reason: Kasich’s success would dampen the amplitude of extreme opinion on the right.

You might wonder, whence stems my license to pronounce on these matters? I have, after all, never covered a campaign. All I can say is that these arguments are deeply grounded in concern for economic affairs over the long run, and you will never hear them from my old friend and fellow economics columnist, Paul Krugman, of The New York Times. He thinks that there are no moderates in the Republican Party primaries, and that even if there were, they wouldn’t stand a chance.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a long-time financial journalist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

Trump does some truth-telling

I must admit that sometimes the great huckster Donald Trump can do some healthy truth-telling. That's a major reason why he seems to be hanging on to such strong support. For instance, he has been the only GOP presidential candidate to note that all the presidential candidates are whores to various degrees to economic interest groups -- that the current system is utterly corrupt. The Koch Brothers summon the GOP candidates and give them marching orders. Hillary Clinton answers to Wall Street.

Yessir, Boss!

He also noted accurately that Canada's popular single-payer health-insurance system (which even the current conservative regime up there does not try to dislodge) works very well -- much, much better than the U.S. joke of a mercenary and chaotic healthcare "system.''

He also reminds people that illegal aliens are, indeed, here illegally, eschewing such ridiculous euphemisms as "undocumented residents.''

-- Robert Whitcomb

Don Pesci: Understanding Trumpism

Trump movie: A fun slide down America's decline

We got so much reaction to the press release sent us by the producer of Trump: What's the Deal? that we're republishing it here. Links to the trailer and the movie are below. You can see the whole movie for free. The trailer is very funny-- and of course fast-paced. Listening to the utterly unique voice of Peter Foges, the narrator, is quite an experience.

The movie is an often hilarious and often enraging look at crony capitalism, runaway narcissism and materialism, much of it within a time capsule of '80s kitsch.

American civic life has been heading ever deeper into the sewer, but it's sometimes a fun ride.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

For inquiries, please use:

press@trumpthemovie.com

DOCUMENTARY TRUMP SUPPRESSED TO BE RELEASED AFTER 25 YEARS

Trump: What’s the Deal? is an investigative documentary that was completed in 1991 --- but has never been seen by the national audience it was made for. Trump took great pains to suppress the film, threatening networks, distributors, and the filmmakers.

Producer Libby Handros says: “Now that Trump is running for president, it’s time for the American people to meet the real Donald and learn how he does business. The old Trump and the new Trump? They're the same Trump.”

“While much has been written on Donald, few know how he built his business,” she explains. “This documentary, which we made at great personal cost over three years, is filled with vivid and dramatic commentary by Trump insiders and prominent outside observers, who expose how he operated as he rose to national prominence.”

NOT “SELF-MADE”

Trump has claimed to be a self-made billionaire. That’s the first myth this documentary punctures. Trump used his father's money and government connections in addition to taxpayer largesse to begin his empire.

“Donald is neither self-made nor anything like a true small-government conservative,” Handros says. “His father made huge profits off Federal Housing Authority loans, and with the help of his father’s friends in government, Donald used the same techniques to build what fortune he actually has.”

TRUMP’S “WEALTH.”

“We also launched one of the first investigations into Trump’s finances to reveal that he did not have nearly as much money as he says he did—a pattern of deception and aggrandizement that continues to this day,” Handros says. “Of all the damaging things we uncovered about Trump, that’s definitely the one that upsets him the most and led to him going after our film so hard.”

A HOST OF REVELATIONS

- Trump’s mob-connected contractor used illegal immigrant labor, provided with no safety equipment, to demolish the building that stood in the way of Trump’s first signature building: Trump Tower.

- Trump hired a company that specialized in psychological attacks and blackmail to move tenants out of a building he wanted demolished.

- Trump was a major factor in the implosion of the United States Football League, and made a failed bid to “buy” Mike Tyson.

- Trump was in bed with the Mafia to buy the land for his first casino, Trump Plaza; he had ongoing associations with known mob figures and drug dealers in Atlantic City.

- Trump’s compulsion, then and now, to verbally abuse his wife and other family members as well as his colleagues and employees.

- Trump bad-mouthed three top executives of his Atlantic City casinos after their death in a company helicopter crash, blaming them for the near collapse of his empire.

- Trump’s manipulation and lying to the press… and their complicity in making him the force he is today.

- Trump’s long battle to move the airport farther away from his mansion in Palm Beach.

And much, much more…

The film was a production of The Deadline Company and produced by Al Levin, an award-winning documentary film producer, (now deceased) and Libby Handros. When the film’s executive producer Ned Schnurman passed away, Handros inherited the piece.

Trump: What’s the Deal? was recently called “an unforgettable investigation into the mating of commerce, corruption and celebrity in America's latest Gilded Age. It explodes the Trump mythology and his presidential campaign with it.’’

To watch the trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Qy75pRQKMU

To watch the film: www.trumpthemovie.com

Long-suppressed film about Trump is now released

This press release, and links, are from my friend Libby Handros, regarding the long-suppressed documentary about the rise of Donald Trump that's now being released. You'll laugh and cry and get mad.

-- Robert Whitcomb

To watch the trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Qy75pRQKMU

To watch the film: www.trumpthemovie.com

DOCUMENTARY TRUMP SUPPRESSED TO BE RELEASED AFTER 25 YEARS

Trump: What’s the Deal? is an investigative documentary that was completed in 1991 --- but has never been seen by the national audience it was made for. Trump took great pains to suppress the film, threatening networks, distributors, and the filmmakers.

Producer Libby Handros says: “Now that Trump is running for president, it’s time for the American people to meet the real Donald and learn how he does business. The old Trump and the new Trump? They're the same Trump.”

“While much has been written on Donald, few know how he built his business,” she explains. “This documentary, which we made at great personal cost over three years, is filled with vivid and dramatic commentary by Trump insiders and prominent outside observers, who expose how he operated as he rose to national prominence.”

NOT “SELF-MADE”

Trump has claimed to be a self-made billionaire. That’s the first myth this documentary punctures. Trump used his father's money and government connections in addition to taxpayer largesse to begin his empire.

“Donald is neither self-made nor anything like a true small-government conservative,” Handros says. “His father made huge profits off Federal Housing Authority loans, and with the help of his father’s friends in government, Donald used the same techniques to build what fortune he actually has.”

TRUMP’S “WEALTH”

“We also launched one of the first investigations into Trump’s finances to reveal that he did not have nearly as much money as he says he did—a pattern of deception and aggrandizement that continues to this day,” Handros says. “Of all the damaging things we uncovered about Trump, that’s definitely the one that upsets him the most and led to him going after our film so hard.”

A HOST OF REVELATIONS

- Trump’s mob-connected contractor used illegal immigrant labor, provided with no safety equipment, to demolish the building that stood in the way of Trump’s first signature building: Trump Tower

- Trump hired a company that specialized in psychological attacks and blackmail to move tenants out of a building he wanted demolished.

- Trump was a major factor in the implosion of the United States Football League, and made a failed bid to “buy” Mike Tyson.

- Trump was in bed with the Mafia to buy the land for his first casino, Trump Plaza; he had ongoing associations with known mob figures and drug dealers in Atlantic City.

- Trump’s compulsion, then and now, to verbally abuse his wife and other family members as well as his colleagues and employees.

- Trump bad-mouthed three top executives of his Atlantic City casinos after their death in a company helicopter crash, blaming them for the near collapse of his empire.

- Trump’s manipulation and lying to the press… and their complicity in making him the force he is today.

- Trump’s long battle to move the airport farther away from his mansion in Palm Beach.

And much, much more…

The film was a production of The Deadline Company and produced by Al Levin, an award-winning documentary film producer, (now deceased) and Libby Handros. When the film’s executive producer Ned Schnurman passed away, Handros inherited the piece.

Trump: What’s the Deal? was recently called “an unforgettable investigation into the mating of commerce, corruption and celebrity in America's latest Gilded Age. It explodes the Trump mythology and his presidential campaign with it.’’